The Inner Language of Wolfwalkers - a guest post by Micah Rickard

Today at Looking Closer, I welcome a new guest reviewer, Micah Rickard.

I met Micah at a very special occasion a few years back — the awarding of the Denise Levertov Award by Image journal to the poet Marilyn Nelson. Talking about art, faith, and criticism during the reception there, we knew right away that we were kindred spirits. Then, he joined my Glen Workshop film seminar this summer and contributed to our conversations about a wide variety of films with expertise and wisdom. When he showed me a sample of his writing about film, I was eager to introduce him to you.

Robyn Goodfellowe is feisty, but her courage will take a hard hit when she runs into dangerous wolves and Mebh, a girl who runs with them. [Image from GKids trailer.]

Since I haven't published a formal review of Wolfwalkers in writing here — I've published two special podcast episodes instead, including a conversation with Tomm Moore, who co-directed the film with Ross Stewart — I'm glad to share some of Rickard's reflections on the film here.

So, without further ado, here is Micah Rickard:

Internal change is one of the trickiest things to express in movies.

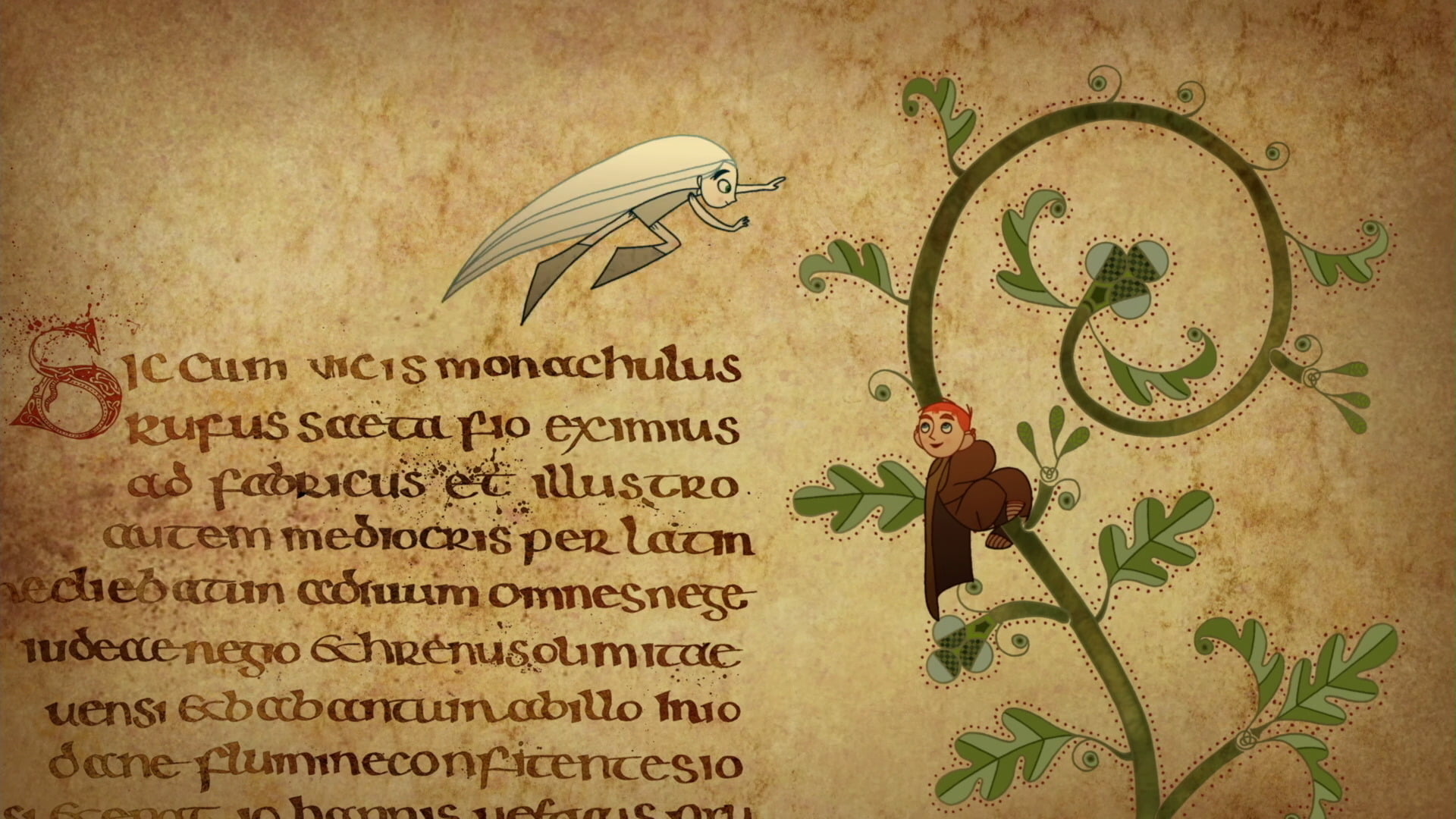

When movies do try to convey nebulous concepts like inner transformation, they often turn to plot-based mechanics — a recent adept example being Inside Out’s use of emotions as characters to express the inner life of a young girl. Wolfwalkers, the new animated film from Ireland’s Cartoon Saloon (The Secret of Kells, Song of the Sea), carves a markedly different path, eliding exposition and crafting a unique visual language to express its emotional and spiritual depths.

Wolfwalkers follows Robyn Goodfellowe, who has recently moved to Kilkenny with her father, Bill. Bill’s help has been enlisted by the Lord Protector, the English-appointed ruler of the town, whose aim is to tame the surrounding forest and, likewise, the Irish people. The Lord Protector’s rule — and religion — is law and order; anything wild is anathema and accursed. Bill is commanded to eradicate the wolves in the forest, and Robyn, eager to hunt, delves into the forest against her father’s wishes. There she encounters Mebh, a Wolfwalker: a human who can communicate with the wolves and who takes the form of a wolf when asleep.

To fully communicate these aspects, directors Tomm Moore and Ross Stewart and animators make use of shifting visual styles, finding a new, wordless language of expression. It is a language of both revelation and invitation, bringing unstated, inner truths out through artistry and inviting the audience inward to share these moments with Robyn and Mebh.

This style distinguishes the forest as a liminal space: a space where the tangible and ambiguous merge, where the spiritual collides with the physical world. It is mystical, beautiful, and dangerous all at once, a wild place where one may find deep magic but may lose themselves in the process. These spaces can also be seen as echoes of encounters found in the Bible — from Mount Horeb to the Holy of Holies — places where God dwelt among his people in specific and mysterious ways. Through the contrasting style, Wolfwalkers creates a visual language of wonder, readying the audience for encounter — an encounter that brings its own sense of transformation.

After being bitten by Mebh, Robyn discovers that she herself has become a Wolfwalker. This new way of being comes with freeing abilities and unexpected dangers, as the townspeople — and even her father — try to kill this perceived threat.

Again, the movie not only reveals that something is different about Robyn, but also brings us into feeling her transformation. We see with her new sight, we feel the foreign, free sense of movement she now has. We, along with her, experience the world around us differently. And here, too, we find spiritual echoes, even if distant. For we ourselves know what it is to be transformed by an encounter with a mysterious Other, to find that we are suddenly something new, no longer our old selves. And, like Robyn, we are called to learn how to put on the new self, to live in this transformed state.

One of the most interesting choices in the movie is to leave penciled arcs on many of the character drawings. The circles, remnants of early sketches, give a sense that these characters are not yet finished. It provides a visual cue to the journey of transformation that these characters are on. They are not so roughly sketched as to be vague — we still recognize and know them — but we feel that there’s still growth remaining for them.

Robyn’s story is not an explicitly Christian journey, but it is an expressly spiritual one. If we are attuned to its language, we can find much that is edifying within. While the Lord Protector is the most direct representative of religion, he clearly wields his Christianity for the aim of dominance and earthly power — a corrupted belief. In contrast, Wolfwalkers creates a unique, visual language to express Robyn’s spiritual arc from encounter to transformation, onward to growth.

Cowboys (2021)

You know the old saying about where a road "paved with good intentions" can lead.

And it's true. I've watched passionate, purposeful, principled artists pour their lives and life savings into projects that, while meaningful for the artists, amounted to unwatchable results.

But it's not a binary proposition, of course: Good intentions can lead to the achievements of masterworks, too — and everything in between, including destinations like 'Mediocrity' and 'Fairly Decent.'

Director Anna Kerrigan's inspiring generosity of spirit is evident throughout her second feature film: Cowboys. And — good news for moviegoers — the result is a large-hearted movie, admirable for its ambitions and its embrace of its environmental contexts as more than just backdrops.

This is the first film I've seen about a trans child, one named Joe (Sasha Knight) whose mother Sally (Jillian Bell) strives with increasing desperation to force her child into the cultural norms for girls when it is very clear that there's something going on here more complicated than childish stubbornness or delusion. Joe isn't interested in Barbie dolls or jewelry or anything else that typical girls are interested in. Fair enough — a lot of girls aren't. But the fact is that Joe's objections go far beyond strong feelings about toys and accessories. Evident body parts are, according to Joe's fierce convictions, not nearly enough to resolve questions about gender identity. This whole "girl" thing is a mix-up. And her father, Troy (Steve Zahn) is willing to listen, to pay attention, and to believe.

But here's the problem: The only one willing to show Joe love rather than trying to muscle a child into a simplistic mold — an act that all too often pushes a child down a path toward suicide — is an ex-con, one who is trying to stay on his carefully calibrated medication menu, trying to win back the woman he loves, and trying to do what is best for his child. That proves to be a lot to juggle. And once Troy impulsively takes Joe away from his mother and heads off on horseback into the Montana wilderness, with police and a determined police detective (Anne Dowd) on their trail, we know that things are going to get a whole lot worse before they get better... if they get better at all.

There's a strong concept here. By drawing a child who identifies as a boy out into the familiar genre trappings of misjudged outlaws on the run from police, Kerrigan gets to play with a variety of tropes. She provokes us with vivid reminders that guns, so typically appealing to boys, can be a dangerous obsession no matter who gets excited about them. She intrigues us by finding the right landscape for evoking a history of pioneers, cowboys, and crooks on the run while also openly challenging those cliches.

As Troy, Zahn finds some quieter, softer tones to play than we're accustomed to seeing from him — even though the movie seems to think we frequently need to see him do that high-anxiety meltdown thing he does do well and so often.

I appreciate that Kerrigan prioritizes casting a trans child actor to play a non-binary child character, and Sasha Knight is persuasive in conveying Joe's sense of alienation and their strong affection for their father Troy. But I wonder if making that a priority made it difficult to find a young actor with a real gift for portraying complexity. Knight's Joe is basically a small gallery of wounded expressions, which means that most of the character's idiosyncrasy and personality comes from costumes instead of behavior.

Jillian Bell manages to invest the character of Joe's mother Sally with some affecting distress when her child does not fit neatly into the gender roles that Sally's culture recognizes. And Ann Dowd does what she can with the unremarkable character of a beleaguered police detective. But the movie can't find much to do with either character. Sally's big scenes come in the context of shopping where she gets anxious about toys that Joe doesn't want and refuses to purchase those that Joe does.

Ultimately, Sally ends up being the one character bearing the full burden of representation for those who struggle to understand such complex aspects of human sexuality. And, yes, there are plenty of people in the world like Sally who refuse to accept anything but binary definitions when it comes to gender. I was brought up in Christian communities that argued that very thing. I eventually began to wrestle with the attitudes I was seeing and the opinions I was being conditioned to hold fast. Some thoughtful believers raised questions about Christ's example of favoring a spirit of Grace over the letter of the Law. Others dared to question whether the ruinous effects of Evil in the world might also extend to causing disharmony in an individual's physical, psychological, and spiritual chemistry, resulting in external details that contradicted the rest of a person's makeup. Don't the Scriptures remind us that human beings tend to "look at the outward appearance, but God looks at the heart"?

In the myriad ways that human beings are born into trouble, Joe's conundrum is a problem that calls for the kind of listening, empathy, compassionate counsel, and faithfulness that Christ models in the presence of outcasts and "exceptions" who have been harshly judged by the pious and the unimaginative. I believe that we are all born into bodies, hearts, and minds that are at war with each other — and this Joe's experience, as portrayed in Cowboys, is representative of one of the most difficult conflicts a human being can suffer because it finds them struggling not only to find peace with themselves but also peace with a hostile and condemning society that hates difference and complexity.

But, just as the complicated experiences of non-binary individuals require patient attention and understanding, so do those who judge them. We see Sally and only Sally causing trouble for everybody by insisting on narrow ideals, so it becomes too easy to judge her as merely obstinate and awful, someone who really needs to just "catch up with the enlightened." I appreciate that Kerrigan's script makes a few moves to suggest that there might be hope for Sally's growth and education, but I'm still uncomfortable with how the film suggests that such prejudices are just something that people need to get over. It rarely ever goes that way.

When right and wrong are sketched so starkly as they are here, a movie can't arrive at much in the way of insight. Thus, in order to engage us, Kerrigan has to cultivate suspense by steering her fugitives into conventionally episodic adventures about avoiding capture rather than taking on the harder job of a nuanced, detailed investigation of gender issues.

And the final scene strikes me as a bit of wishful thinking, a contrivance meant to make us feel hopeful... but it just rings false.

Still, I'm glad Cowboys exists. We need more movies like this and Barry Jenkins's Moonlight — films that are willing to take on complicated and discomforting questions about sexuality, that explore the struggles of young people who don't conform to the strict, binary definitions forced upon them. (I'd go so far as to say that, while Moonlight is the stronger film in many ways, Cowboy's Joe is better defined as a character here than Chiron is in Jenkins's film.)

And I'm pleased that Anna Kerrigan unfolds this story at a contemplative pace, with a strong appreciation of quiet, and with a meaningful appreciation of its Montana context.

Hopefully, we'll see stronger films soon that explore this territory, films that avoid easy scapegoats and villains, and that help us reach more meaningful conclusions than "Why are some people so narrow-minded and cruel?! Why can't we all just love everybody?!" We need to get into more productive explorations of causes, consequences, and possible, productive paths forward. Otherwise, it's just another Us-Versus-Them dynamic that makes the "enlightened" feel righteous without kindling questions in anyone who might be open to exploring them.

Here is the trailer, although I would caution you: This is one of those trailers that gives away important moments from the full span of the motion picture, so it should come with major spoiler warnings.

https://youtu.be/jKSxBCatIKA

Paterson (2021)

During last week's online edition of The 2021 Glen Workshop, hosted by the literary arts journal Image, a group of seven thoughtful explorers joined me to study work by more than a dozen extraordinary filmmakers. It was a multi-genre adventure: Our tour included stops at Days of Heaven, The Secret of Kells, 35 Shots of Rum, Boys N the Hood, and Moonlight, to name only a few. Our goal? To discover how the places, the contexts, the environments of these films become a form of poetry — suggesting themes, influencing characters, creating vocabularies that we could read and learn from.

On Monday, we watched the first two films by Terrence Malick and saw how the natural world revealed the world as it is, a paradise lost, while also whispering rumors of glory.

On Tuesday, we focused on films about cities: Dziga Vertov's Man With a Movie Camera, Jacques Tati's Playtime, Wim Wenders' Wings of Desire, and Jim Jarmusch's Paterson.

Much to my surprise, several of my fellow adventurers hadn't seen Paterson yet.

I couldn't help but feel as if I had failed in some sacred trust. Paterson is five years old now, and I've been talking about it non-stop! Have I not done enough to spread the word about this movie that I love so much? I hurried to find a link to my written reflections on the film and discovered, to my dismay, that I haven't posted them here. Sure, I published some first impressions here at Looking Closer, but the more substantial piece I wrote for Christianity Today has sunk beneath the paywall there.

So I'm re-publishing it here now. I hope that it might be helpful as I seek to persuade my friends and readers to discover this richly rewarding film, in which I hear echoes of so many great films: Wings of Desire, Taxi Driver, and more. On the massive map of cinema, Paterson has become, for me, one of the most meaningful characters ... and one of the most meaningful places.

[The following article was originally published at Christianity Today on January 30, 2017.]

To tell you about this movie, I need to tell you about my wife.

Sometimes, lying awake at night, side by side, Anne and I listen to our neighborhood. Traffic becomes the ocean, waves breaking on a beach. Wind in the evergreens is the roar of a crowd. Fire trucks: trumpeting elephants that charge from the circus tent of the fire station next door. Anne’s favorite is the rush of the midnight street sweeper. She has written poems about the driver’s rumbling reverie, out there “tracing the bones of the city.”

Anne’s attentiveness to poetry is what drew us together in the first place. I strive to learn from her compulsion. Like the angels in Wim Wenders’ film Wings of Desire, she carries empty journals with her into her days and fills them with glimpses of the extraordinary in the ordinary. Her patient watchfulness quiets my fears and helps me hear the still, small voice of the Spirit.

That’s why Paterson, Jim Jarmusch’s meditative new comedy, feels so necessary, essential — even medicinal for me.

Movies about poets are a hard sell. Perhaps I can get moviegoers’ attention by telling them that the movie’s lanky leading man, Adam Driver, is the same guy who threw spectacular tantrums as Kylo Ren in Star Wars: The Force Awakens. (He’s also onscreen this month as a brave and emaciated missionary in Martin Scorsese’s masterful Silence.) But here, Driver’s a driver, steering a bus around Paterson, New Jersey, the town that shares his name and wins his heart. His bus in non-articulated, but he’s as articulate as they come.

The movie’s heartbeat is our driver’s creative process — his line-by-line composition as he makes his introspective way about town. And if we surrender to the film’s meditative pace, we may find ourselves discovering suggestive implications in common sights along the route: a road sign that says “Prospect Street,” a building’s bold letters that say “Department of Recreation.” As in the poems of Paterson’s favorite poet, local legend William Carlos Williams, “so much depends upon” details that seem commonplace.

I’m not the first to notice this film’s formal resemblance to Groundhog Day (Variety’s Justin Chang got there first). But although every well-structured day looks alike—he begins each one with an alarm check, then puts on the same old uniform—he’s vigilant for variations on the form. Paterson proposes, “Hey, what if you woke up each morning and discovered, to your delight and astonishment, that it’s another day?!”

Jarmusch seems to take an almost perverse delight in teasing us with familiar plot possibilities, and then bypassing predictable turns. He’s too in love with his characters to reduce them to “delivery devices” for meaning. That’s been the strength of his films from the beginning. Down By Law, Broken Flowers, Coffee and Cigarettes, Only Lovers Left Alive — in these films, the people, in their exquisite idiosyncrasy, are the purpose.

He never knows what to expect when he comes home to his impulsive, dream-driven wife Laura (Golshifteh Farahani). One moment she’s an aspiring country singer, the next a painter, the next the Cupcake Queen of Paterson. But there’s no crisis brewing. He just loves her. And so do we.

Then there are his mass-transit passengers, the familiar faces at his daily Happy Hour hangout, and unlikely pedestrian encounters — a high school girl waiting for a ride, a subwoofing carload of vaguely threatening punks, a dejected actor recently heartbroken. None of them exist to advance the plot; their value is in the moment to which Paterson closely attends.

Even the crowdpleasingly adorable bulldog, Marvin, who scowls jealously at Paterson as a rival for Laura’s attention, refuses to be leashed to any movie-dog conventions.

But not even the dog can steal the show from Driver, who makes Paterson one of the most interesting men I’ve encountered at the movies. His younger self, in uniform as a Marine, stares dutifully from a picture frame at home, assuring us that he’s ready for action. But what kind of action? As Steven Greydanus notes in his review at The National Catholic Register, Paterson’s “an unconventional if appealing icon of masculine virtue: the farthest thing from a Hollywood action hero — humble, quiet, poetic, committed, yet capable of heroism if necessary.” Think Taxi Driver reimagined by Fred Rogers.

That’s why Paterson is so refreshing. Our hero’s not watching for a way to save the day. He’s watchful because he’s interested. And his watchfulness makes him capable of action when it’s necessary. But even though his story is, in fact, headed to a moment of heroic decision, it arrives without fanfare, in a quiet exchange, a serendipitous gift for both the character and the audience. Call it an “a-ha!” moment. And it comes as a reward for Paterson’s willingness to be open, to listen, even at a most inconvenient time.

That humble watchfulness, more than any Braveheart bravado, shows me the kind of man I want to be. These small but carefully calibrated expressions that he scribbles in his notebook make me want to love my world the way that he loves his. Paterson’s story isn’t about something he does for the world. It’s about the way that he is: an open satellite dish catching glory, his humble posture enabling him — and by virtue of our proximity, us — to receive such rich rewards as love, friendship, and the contentment of belonging.

In his meekness, he inherits the earth. Or at least the part that bears his name.

[I recommend Paterson to viewers 17 and up.]

Questions for Discussion

- Paterson is divided into chapters that begin each time he wakes up. How does this structure accentuate the film’s focus on poetry?

- Describe Paterson’s relationship with Laura. Are they a good match? How or why? What words would you use to describe the nature of their love for one another?

- How are Paterson and Laura different from other movie couples?

- How do people treat Paterson, and why do you think that is?

- How would you describe Paterson’s poetry? What does it reveal about him and the things that are important to him? How does the discipline of poetry influence his life and demeanor?

- When the crisis comes for Paterson, what challenge does it present for him? What might he learn from the experience?

- Is there anyone who resembles Paterson in your life — who seems unburdened by angst, contented with their work, and consistent in their demeanor? Are they appreciated for their work and reliability?

- Who are the most joyful characters in the film? What makes that joy possible for them?

- Look up a few of William Carlos Williams’s most beloved poems and read them aloud with each other. Discuss what you think they might be about, what their details suggest to you about the world.

- Have you ever kept a daily journal, either for poems or other creative expressions? How might that discipline change your own day-to-day routines?

Animator and author Ken Priebe talks about his three fantastic children's books in the latest Looking Closer podcast episode

In the latest episode of the podcast Looking Closer with Jeffrey Overstreet, Vancouver B.C. author, illustrator, animator, and educator Ken Priebe talks about his three outstanding children's books: Gnomes of the Cheese Forest, Let There Be Owls Everywhere, and The Ice Cream Truck at Midnight, all of which you can enjoy by ordering through the website of your favorite independent bookstore... or through the corporate giants, if you need to.

Listen to our hour-long conversation here!

Priebe has been a friend and kindred spirit for many years, enthusing with me over the Muppets, favorite animated films, beloved children's books, and more. It's extremely rare that I meet anyone whose lifelong passions overlap so much with mine.

He's also a generous artist. He's surprised me with illustrations from time to time, like this one of one of a viscorclaw, one of the creepy wooden monsters from my own fantasy series The Auralia Thread:

Here are a couple of portraits he has done for my endeavors at Looking Closer:

It's been a goal of mine for many years to feature Ken Priebe at Looking Closer in a way that will inspire readers to discover his imagination for themselves. So listen in to this wide-ranging conversation about monsters, mayhem, and the life-saving power of play.

Pig (2021)

Watch for the moment in Michael Sarnoski's film Pig when Robin — a formidable, Jesus-bearded truffle hunter living as a recluse in the woods outside of Portland, Oregon — walks through a fancy downtown restaurant like Obi-Wan Kenobi making his way to the heart of the Death Star, reluctantly leading his anxious young driver Amir to the threshold of a secret underworld. As they descend into a forgotten world of old Portland history, Amir's panic increases; he doesn't know where they're going or why. When he flicks on his iPhone flashlight to light their way, Robin, brusque as always, snaps at him: "Turn it off. Your eyes will adjust."

Those are fleeting comments, as incidental as anything this wounded old man says along the journey. But those words, in retrospect, sound like a larger lesson — a summation of everything Robin means to teach this young, materialistic, and ambitious entrepreneur.

The trailer for Pig led me (and probably everyone who saw it) to anticipate a John Wick-style revenge thriller. It captured our attention and inspired our skepticism with glimpses of a bloodied and furious Nicolas Cage emerging from the woods on a seemingly violent campaign to regain something precious that had been taken from him. "I want my pig back," he snarled, and that's all we had to go on. I braced myself for a video-game sequence of scenes in which a wrathful hero slashes and bashes his way toward a showdown with a Final Boss of some kind, leaving broken bodies in his wake.

But the surprise awaiting viewers is that Pig is something altogether different.

And what it is is best categorized in a genre that's much less popular but much more rewarding: Let's call it "Mentor and Student" or "Master and Apprentice."

Watching it, I found myself trying to remember a dynamic that might serve as a good comparison — perhaps Sean slowly saving Will from his paralyzing insecurity and trauma in Good Will Hunting, or — better — Olivier disciplining himself into the role of surrogate father for a troubled juvenile delinquent in Le Fils (The Son), because that film is more focused on the teacher than the student.

But what's even more interesting about the central relationship in Pig is that young Amir (played by Alex Wolff as an arrogant poser slowly coming apart like Tom Cruise in Rain Man) thinks he's the guide, at first, lecturing Robin as he brings him out of the woods and into the "jungle" of the contemporary Portland restaurant scene. But Amir will quickly learn that the world he thinks he knows is built on lies, and it's actually Robin who knows how the world really works.

Fair warning: The movie does take violent turns. In a surreal, David Lynchian sequence early in the film, Robin gets beaten to a pulp, and he hauls his bloodied carcass around after that like a testimony of abuse and losses, the camera often revering him as if he were Jesus Himself. (I'm not the only reviewer reminded of The Passion of Joan of Arc.)

But don't let that give you the wrong impression. Pig is, above all, a meditative film that prioritizes its short but weighty conversations between a begrudging guru and an obstinate idiot. Robin is a sort of sensei or Jedi Master from an ancient world when Portland chefs were like samurai or Jedi with a code of honor and excellence. Amir is like a begrudging Padawan learner who begins as a salesman for pretentious artifice and scams, one who ends up humbled by his first encounters with profound artistry. (I can hear Kenobi's voice haunting the film: "You've taken your first step into a larger world.")

I'm seeing the title now as carrying a double meaning: It can be read literally, as a reference the titular MacGuffin, or it can be read as a world-weary condemnation of the villain — the kind of person who, corrupted by a lust for power, abandons conscience and conviction. The movie is, ultimately, about the value of Authenticity, and how the costly path we must navigate to attain it is a lonely road that leads us out of the mainstream, with its money and glamour and power games, and into the wilderness where the remaining goodness of the world might still be glimpsed and savored in quiet, fleeting moments.

The less you know about the plot going in, the better. If you can stop here and go see it on my whole-hearted recommendation... do so! Having said that, I will minimize spoilers in what I say going forward.

Let frame the story with more clarity:

The film opens with a short series of moments in which we observe Robin's routine of truffle hunting with his charming, fuzzy pig. As I've just seen the documentary The Truffle Hunters, I was intrigued to see the film propose that this strange harvesting technique is the same just outside of my hometown of Portland, Oregon as it is in the forests of Northern Italy.

Amir, the son of a "king" of the Portland gourmet dining scene, wants to make his own way and prove to his power-drunk, egomaniacal father (Adam Arkin in a chilling turn) that he's worthy of respect and love. He pep-talks himself in the mirror: "I'm the king of the jungle. I'm the king of the jungle!"

But Robin's going to help Amir's eyes "adjust" to just how dark this world really is, how deep the delusion of hipsterism really goes, and how painful it can be to carry the knowledge of what is possible, what is beautiful, what is true. He will lead Amir on a tour of his own neighborhood and show him how to really know the nature of the place for the first time.

As the voice of Wisdom — and, thus, the bearer of unfathomable grief — Nicolas Cage delivers the most nuanced and soulful performance we've seen from him in more than a decade. Cage, whose performances in the '80s earned him lasting respect, has since then seemed inclined to take any role within reach, even as he has seemed less and less interested in doing anything interesting with those roles. Occasionally, something will bring out the memorably manic edge (Bad Lieutenant: Port of Call New Orleans, Mandy) that characterized his 1987 breakout roles: Ronny in Moonstruck, H.I. in Raising Arizona. But I haven't seen him invest in a distinctive character with meaningful and memorable results since the 2002–2003 sequence of Matchstick Men and Adaptation. In Pig, he gives Robin a gravity, a physicality, and a measured way of speaking that conveys discernment born of suffering and experience. In that sense, this is like David Thewlis's titanic performance in Mike Leigh's Naked if that main character had been well-intentioned instead of nihilistic and self-destructive. I hope Pig represents a turning point in his career, the beginning of a new era of textured, nuanced, subtle performances that I believe he is fully capable of contributing.

Much of the film's sadness comes from moments when Robin asks for something in civilization that the locals know nothing about — for example, there's a particularly poignant moment when he visits a property he once knew and asks a child about a particular persimmon tree he remembers and cherishes. The child blinks and asks, in complete innocence, "What's a persimmon?" A word has been lost, and, along with it, a city's access to a specific wonder, a particular treasure.

That is one of the things we might say that Pig is "about": When we cease to care about the world we're living in and care only about imposing our ideals upon it, thinking we know what is best, and desiring only our own benefit, we destroy what is already there — a wonderland that might have humbled, enchanted, and blessed us.

So, no — Pig doesn't leave me with that sense of exhaustion I feel after hyper-violent movies. Nor does it give my spirit that bitter aftertaste so typical of revenge epics.

Instead, I find myself thinking of Babette's Feast, in which a worldly general, his soul hollowed out by vanity and violence, suddenly recalls a memorable meal served by a world class artist. I think of that unforgettable moment at the climax of Pixar's Ratatouille, when a single forkful of food becomes the key that unlocks the secrets to redemption. I think of The Son, in which a broken man takes up a burdensome cross, determining to teach a young man whom he has every reason to despise.

Still, I can't quite put into words why I find this wild — and, yes, in some ways absurd — motion picture so moving. I found myself, quite unexpectedly, grieving near the conclusion. It's as if Robin has given me a character through which I can acknowledge deeply personal losses, sufferings I find hard to describe. With each passing year, I see it becoming harder and harder for those who seek beauty and truth in the world to find it. The demons of commerce and consumerism make it particularly difficult for artists to do good work, and even harder for audiences to find it. At the movies, it seems that the cliche, the derivative, the counterfeit, and the corrupt continue to trump occasions of poetry. This film is, I am grateful to discover, about that very thing. And at the same time, it gives me hope, because it is an exception to that trend: It's a film of startling imagination, honesty, and grace... one that has reached the big screen in a time when such occasions are rare.

I'm reminded of the moment when Samwise, in the film version of The Two Towers, reminds his despairing friend, "There is some good in this world ... and it's worth fighting for." And yet here, even more meaningfully, the enemy of all that is good is fought not with swords and violence, but with generosity, beauty, and grace.

Sunday Song: Sault return with "Nine" songs of lament, luxuriant pop, and hope

They've done it again.

That mysterious collaboration of London artists called Sault, who released a one-two punch of albums in 2020 that became my favorite records of the year — Untitled (Black Is) and Untitled (Rise) — have surprised us with another album in 2021.

Nine is shorter, but it's every bit as affecting, challenging, and irresistible, with producer Inflo cultivating a consistently surprising weave of sounds from different genres, eras, and places. (I'm learning that this Inflo is very good at this: he did the same for Michael Kiwanuka's self-titled 2019 album, which was such a joy, and which won the Mercury Prize.)

Recurring Sault vocalists Cleo Sol and Little Simz shine in a variety of spotlights and styles here, constantly changing up the sound in ways that highlight hardship and grief without ever losing sight of hope, humor, and, somehow... joy.

On Sault's Instagram account, they introduced Nine and its contextual focus with straightforward specificity:

Some of us are from the heart of London’s council estates where proud parents sought safer environments to raise their families. Community is the only real genuine support & the majority of us get trapped in a systemic loop where a lot of resources & options are limited.

Adults who fail to heal from childhood traumas turn to alcohol & drugs as medicine.

Young girls & boys looking for leadership can get caught up in gang life.

It’s very easy to judge.

What would you do if this were you?

(Thanks to Ryan Leas at Stereogum for catching this post. I follow Sault, but I clearly needed to catch up.)

That note serves as a clear, concise outline for the album.

As there are ten tracks, I wasn't sure what the title was referencing. They have previous releases called 5 and 7. It could just be that Track 9 is titled "9," or it could be that Sault have indicated that the album is only going to be streaming for 99 days. I'm grateful for Kitty Empire's review at The Guardian, where she points to other possibilities: "Another 'nine' occurs ... on 'Trap Life': 'Don’t reach for that nine, nine, nine,' Sol begs, referring to a firearm; the repetition also suggests dialling 999."

On a propulsive beat — one that Empire "sounds like the Chemical Brothers’ 'Block Rockin’ Beats,'" "London Gangs" focuses on London's deep-rooted culture of gang violence, but it does so without glorifying violence or turning it into melodrama. Rather, the lyrics are location-specific enough to suggest that they are meant primarily for those who live there, those who will recognize keywords. Until I looked it up, I didn't know that wagwon is a Jamaican expression, a conjunction of "what's going on" —· and it's used here probably to reflect a common greeting between London locals. But I suspect it's also a nod to Marvin Gaye's famous melodic lament "What's Going On," the spirit of which is threaded throughout this record.

https://youtu.be/X80VdV-ruy0

After rumbling through lines that bear witness to gang life's eye-for-an-eye ethic — "Revenge is all you know / They did your big bro" — Sault shifts into a softer, gentler mode, a still small voice of counsel and care:

I know what you try, but it's a fight uphill

It's not a secret you're lost

But I believe it's just centred on war

The salt will heal the wounds...

That play on words in the last line is the clearest mission statement I've yet heard for this band. So far, their m.o. seems to be a refusal to participate in the attention-seeking, ego-serving tactics of most commercial music, and a prioritization of testimony, lament, and healing. I can't speak as one among their target audience, but insofar as these songs are awakening me further to a world of hurt among neighbors I've never known, they educate and inspire me to know more, to amplify their cries and their glory, and to look for occasions to raise them up.

By the end of the album, the full Nine experience feels like another step in the birth of a new genre, a fusion of styles that open up location-specific testimonies and weave them into sounds from around the world, emphasizing common ground without sacrificing respectful specificity. Can albums be artful documentaries? Sault seems to think so.

Describing this particularity in a focus on the album's final track, "Light's In Your Hands," Pitchfork's Tarisai Ngangura gets it just right: "The song’s specifics are hyper-local, but zoom out of London, and these narrators and their lives weave themselves into the fabrics of Black stories across the globe."

That closing track offers up the last of several documentary-style testimonies from particular storytellers, authentic voices reminiscing about what it's been like to grow up in their neighborhoods, what it's been like to live their unique experiences of hardship and hope. "When you think about it, I never really had a childhood,” a man says. "I was constantly on edge. Throughout my whole childhood. But, we just, we drew accustomed to it, to the point now we're adults and we got thick skin. You shouldn't have to have skin as thick as ours, like... you shouldn't."

His story is framed with one of the most soothing and consoling choruses we're likely to hear all year:

Without love, it's hard for you to give it a try

So many promises that turn into lies

Don't wanna start again and give someone a chance

Can't you see the light's in your hands?

https://youtu.be/4d5xFv3Xvek

The secrets of Cartoon Saloon's success: a talk with Tomm Moore and Nora Twomey

In the latest episode of Looking Closer with Jeffrey Overstreet: The Podcast, Dr. Lindsay Marshall and I talk with the world-class animators and storytellers Tomm Moore and Nora Twomey, makers of The Secret of Kells, Song of the Sea, The Breadwinner, and Wolfwalkers.

You can listen to it here:

This episode became possible when Cartoon Saloon reached out to me as a response to last year's podcast episode in which Dr. Marshall and I celebrated the arrival of Wolfwalkers and declared our love for Cartoon Saloon's body of work.

You can listen to that early episode here.

Would you like to meet Tomm Moore? He will be a special guest later this month during my film seminar at the Glen Workshop. If you're joining me for those daily conversations during the last week of July, you'll get your chance to meet him and ask him some questions yourself. Details here: Workshops and Seminars 2021 - Image Journal

Whale Writer: Peter Wayne Moe on his passion for whales, writing, and teaching

If you are on the hunt for great books about writing, great books about teaching, great books about faith, or great books about whales — yes, whales — have I got a recommendation for you!

Here is the full Facebook Live conversation I had with Peter Wayne Moe on June 17 about his book, which invites us into meditations on =whale-chasing, writing, and faith: Touching This Leviathan.

Melissa Bear and David Brewster of The Edmonds Bookshop hosted this event, captured it, and delivered this recording so that we could share it with a larger audience. (The original live event ran into technical difficulties, and the first 20 minutes of the event did not stream. Fortunately, thanks to Brewster's efforts, we can now share the whole thing.)

If you have any trouble playing the video below, follow this link to the original Facebook post.

Anne and I have been buying up copies of this book, too — we're that enthusiastic about it. It's great when you find that your friend's new book is legitimately the best thing you've read all year.

Learn more about Dr. Moe and his extraordinary book at peterwaynemoe.com.

So Much Love: a conversation with Lowland Hum about their reinvention of a Peter Gabriel album

How rare is it that you fall in love with a musical discovery and it's the beginning of a beautiful friendship — not just with the music, but with the musicians?

In April of 2018, during an annual meeting of the Chrysostom Society at Laity Lodge (a retreat center at the edge of the Frio River near Kerville in Texas), I had yet another amazing musical encounter thanks to some brilliant networking by my friend Steven Purcell, the Lodge's events director.

Lowland Hum — the married singer/songwriter duo of Daniel and Lauren Goans — performed a set of stunning poetry, profundity, and humor. They played songs from across their first several albums, told stories about how they met and began making music together, and won a new community of fans and friends.

I remember quickly bonding with them over favorite albums — including the delightful discovery that we all prefer Paul Simon's The Rhythm of the Saints to his far more popular Graceland.

And then, a year later, they released what I'd argue is their strongest album yet: Glyphonic. I included it on my list of favorite records of 2019. (Here's my favorite track from that record: "Slow.")

https://youtu.be/1D0XjroEpOM

During the pandemic lockdown of 2020–21, Lauren and Daniel stayed very busy "delivering" two new releases: their first child, and a record that already means a lot to me.

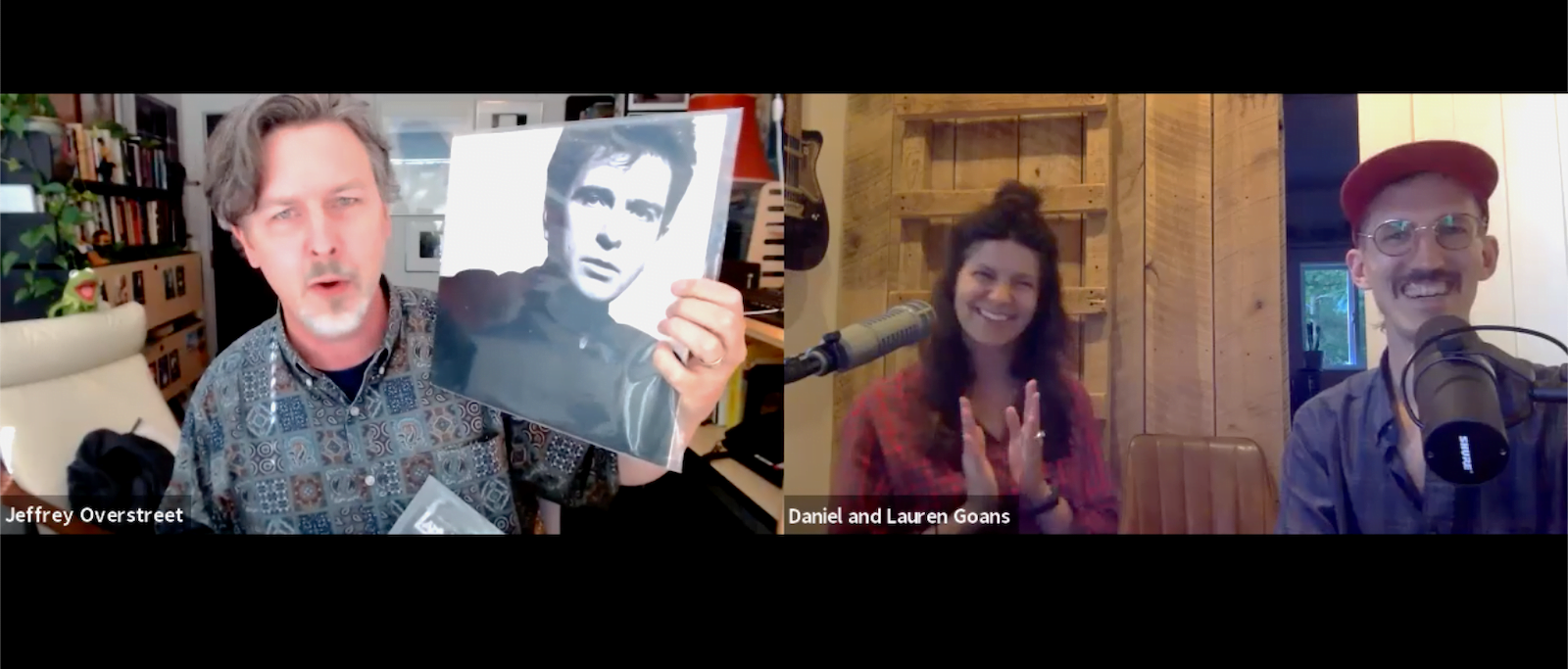

My very first CD, way back in 1986, was Peter Gabriel's classic art-pop masterpiece So, and this year marks its 35th anniversary. So — of course — I was overjoyed when Lauren and Daniel sent me a little secret: They were reimagining that entire album, track by track, to celebrate that landmark.

They call their hushed, haunting recreation So Low. And I love it.

I love it so much, in fact, that I sent four or five videos via text in which I tried to express some of the ways in which the album was amazing and blessing me and Anne. That led to a conversation over Zoom where we talked about the project for almost two hours.

You can listen to most of that conversation in this 82-minute "Master Shot" episode, my first Looking Closer podcast episode in several months.

Here, we talk about Lauren and Daniel met and how the band came to be. And then we take a deep dive into appreciating the marvels of that astonishing, mysterious Peter Gabriel classic... examining it track by track.

There's even a moment that in the conversation where I surprise them by holding up the very first CD I played on my very first CD player — and on the podcast, well, you don't get to see what I'm sharing with them:

I hope you enjoy our conversation. More than that, I hope you enjoy Lowland Hum's amazing catalog of music, particularly this remarkable release.

Sunday Song: Listening Closer to Rhiannon Giddens and Nick Cave

In her long season of pandemic lockdown, Rhiannon Giddens worked with her partner in love and life, Francesco Tussiri, on a surprising new album of spirituals. 2021 has been a year in which almost everyone has lost a loved one, or knows someone who has lost a loved one, to COVID-19, and so the reality of our fragile existence has been on our minds more than usual. Contemplating the nearness of death through the lens of the Gospel, Giddens grieves, she memorializes, and she hopes. "Avalon" is just one of many stunning tracks on the album They're Caling Me Home.

Speaking with Bob Boilen on NPR's All Songs Considered, Giddens says the song is "a cross-section of the two main themes ... of the record: It's about home — missing home, what is home — and then it's also death."

She goes on:

I find this always happens like I write something. [I] make it, and then think about all the things that it means afterwards. So like, for me, "Avalon" is kind of operating on two different levels: the words, which are sad because it's talking about a mother or a father who have passed on to the other side. And you're kind of contemplating, 'OK, hopefully they're waiting for me where I'm I'm going to go one day,' right?

But then there's this kind of undercurrent of joy that kind of came out in the way that it was written, in the way that we performed it, which I think is the other side of the coin that we don't always get to. The one constant that we all have is that we will die ... and there's actually a comfort in that. That is something that is not a question.

As her last album — there is no Other — was my favorite of 2019, I suspect that They're Calling Me Home will end up in my top 10 of 2021 as well

https://youtu.be/esILLxHM92M

As I discussed in my podcast episode on Flannery O'Connor, and as I discussed with my Literature and Faith class at Seattle Pacific University, there are few fiction writers who have ever shown a greater dedication to the fearsome truth of the Gospel, how it exposes the ugliness in all of us, and how it exposes even more so the immeasurable grace of God. (Disclaimer: Yes, while she was powerfully progressive in her thinking and writing on the subject of race, it is undeniable that the times and the culture in which she grew up tainted her, just as it tainted any other white American in the South, no matter how conscientious they were.)

O'Connor's writing has clearly influenced the great Nick Cave, and his own storytelling and song lyrics have often been described as O'Connor-esque in the ferocity of their Christian vision. He is an uncompromising writer, and in recent years, in his dedication to truth-telling and honesty, he has taken listeners with him on a tour of grief — grief brought on by the death of his son in a fall. This is the third album in which that subject has been focal. But where The Skeleton Tree and Ghosteen were sonic experiments, Carnage returns Cage to some of the sounds of his earlier work, reconciling a wide range of styles into something whole, coherent, and grand.

This title song is rich with mysterious imagery both harrowing and hopeful.

In a review of the album at Rolling Stone, Kory Grow observes,

Since at least the second Bad Seeds record, 1985’s The Firstborn Is Dead, Cave has been alluding to kings and kingdoms. Then, the kingdom was Tupelo, Mississippi, birthplace of the inspiration for Cave’s trademark coiffure (and the King of Rock & Roll), Elvis Presley. By the Nineties, on The Boatman’s Call — the record, where Cave finally left guile behind in his search of true love and devotion — the kingdom is finally biblical, a place he hopes to dwell one day with his lover. It’s about as gothic as Christian rock gets. That kingdom is the same as the one on Carnage, though it feels more distant here.

https://youtu.be/3eXtxv1nhwI