All-Stars: Steven D. Greydanus and 20+ years of extraordinary writing on film

Who are the Looking Closer All-Stars?

Okay - I admit that it's a goofy title. But after reading an essay by Sarah Welch-Larson the other day, I felt suddenly compelled to start celebrating some of my favorite writers. Writers who help me discover and appreciate great art. Writers who are "carrying the fire" (to borrow a phrase from Cormac McCarthy's feel-good family-time storybook The Road) — that is to say, they lead us to meaningful blazes in a world dark and cold. And they do so generously, without the distraction of ego, and with the benefits of wisdom and wit.

I began this series with praise for Sarah Welch-Larson's writing. I've been reading her for several years now. But today's All-Star, well... we go way, way back.

I've been learning from Steven D. Greydanus's film criticism for more than two decades now, since the earliest days of Looking Closer and his own website, Decent Films, which launched in 2000. (Scrolling back through my history here at Looking Closer, I find mentions of Steven's views in more than 200 posts!) His work at Decent Films, The National Catholic Register, Crux, Catholic World Report, Christianity Today, and (most recently) at Bright Wall Dark Room has been consistently enlightening and beautifully written. He brings such a personal passion to his work, drawing from his expertise in cinema but also in literature, in drawing, and in raising a family. When he's writing about literary adaptations, he's especially good. And parents may be the readers who have the most to gain from his work, as his care for the family experience of movies comes from his own experience with his wife Suzanne and their children. (I've noted his review of Coraline as a good example in the past.)

His passion for excellence in cinema is deeply rooted in his love for the Gospel: thus, he celebrates beauty, imagination, and truth. It's a joy to share his reviews and essays as examples of excellence in my classes on academic writing and the arts.

Steven has corresponded with me about film through all of those years in a variety of ways: He's texted me right after a screening to enthuse about something that impressed him. He participated in the long-running ArtsandFaith.com community that Image used to host, which captured the decades-long history of a growing community. And he's played a leadership role in weeks-long threads of conversation online with other colleagues so that we can all find our way toward greater understanding of complicated films we've just seen.

In 2019, I had a fantastic time comparing lists with him — lists of our favorite literary adaptations to film — on a podcast formerly called Libromania (but apparently now called Bibliography?) You can listen to that here:

Some of my best memories of Steven come from times we've shared at press screenings. I have particularly vivid memories of our attendance at special events for Constantine and The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King, after which we interviewed the casts and filmmakers of those movies. I treasure my recordings of those conversations, and his questions often provoked memorable responses and conversations. And then we would talk movies for hours over meals in the hotel bar. I miss those days — it was always an honor to work beside him. And I've had the privilege of being welcomed with such warm hospitality into his family's home.

But most of all I am thankful for his leadership as an exemplar of faith in public. How many film critics with membership in the New York Film Critics Circle are also deacons in the Roman Catholic Church (in this case, the Archdiocese of Newark)? His social media accounts are full of scriptures, prayers, and he never fails to challenge distortions of the Gospel where he finds them — especially if those harms are committed by those who profess Jesus' name (as they so often are). But I never find him self-righteous or arrogant. He doesn't just talk about Jesus; he reminds me of Jesus.

And he carves out some impressive Jesus sand sculptures, too!

Okay — let's get back to the particular work that makes me include him in this list: He's just posted two new pieces at Decent Films that are well worth your attention.

First, there's "The Gospel According to the McDonaghs." He's taken a deep dive into the films of Martin or John Michael McDonagh, who gave us In Bruges, Calvary, and the new movie The Banshees of Inisherin. And he comes back with treasure. He writes:

Beyond Catholic cultural elements and religious and moral themes, these three films share a number of hallmarks common to the brothers’ work: absurdism and humor; gruesome violence and grotesque elements; questions of guilt, punishment, and redemption; and a dark cynicism at least approaching misanthropy or nihilism, though not entirely despairing of hope. Going further, each of the three films is set in a picturesque, ostensibly idyllic location that for its characters becomes a kind of ambiguous limbo, if not a manifestation of hell. The central conflict in each case turns on a deadly grievance among male characters, with Gleeson playing one of the principals as a man with a capacity for violence who, in a pivotal third-act moment, meets a potentially deadly threat with Christlike nonresistance. A female character in at least two films represents some sort of grace, while children and animals embody innocence, and killing a child or a beloved pet, even accidentally, may be regarded as an unthinkable crime, beyond all hope of forgiveness or atonement. Scenes set in confessionals figure in all three films, but they’re settings more of conflict than of reconciliation.

...

There’s more bad news than good news in the McDonaghs’ work, but there is no good news without the bad. One way and another, there are signposts here pointing out the most excellent way, for those with eyes to see.

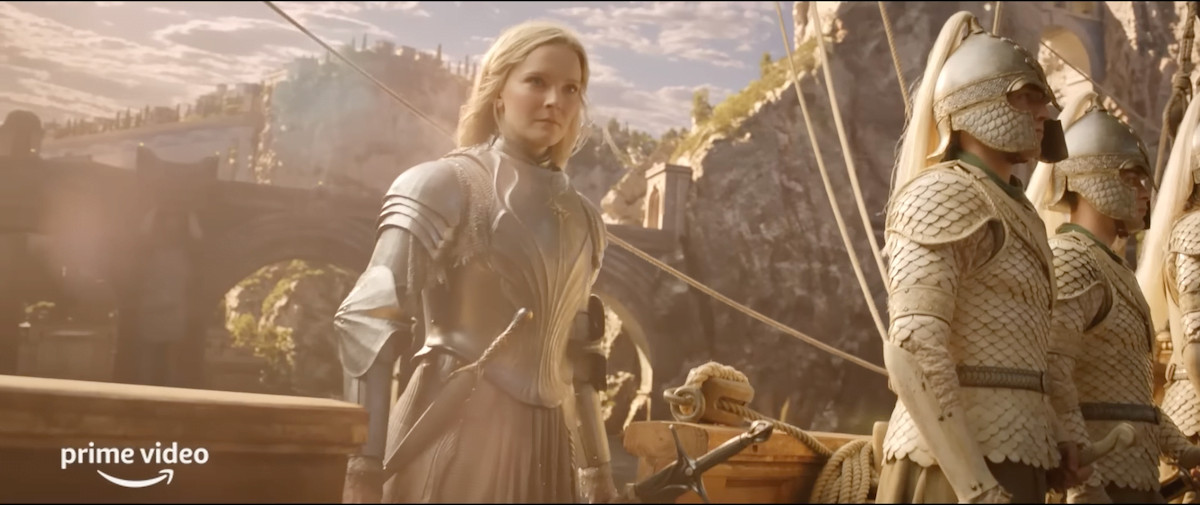

He's also written several pieces about the new Amazon series The Rings of Power. Here's his wrap-up of Season One, where he writes,

A fictional world, for Tolkien, is a “sub-creation,” and the creativity of the human author is in some way a reflection of, and participation in, the creative activity of God. In the case of a derivative work like The Rings of Power—or even a relatively direct adaptation like Peter Jackson’s Lord of the Rings films—we might say that, if Tolkien is the “sub-creator” of Middle-earth, perhaps storytellers adapting and expanding on his work, or artists visualizing it, are “sub-sub-creators.” Only what Tolkien wrote or drew himself is actually his own sub-creation; anyone else’s efforts (even artwork approved by Tolkien, such as some of Pauline Baynes’ illustrations for The Adventures of Tom Bombadil) are at best a reflection of Tolkien’s creative work.

And that is merely a prelude to his review.

If you want some of the most consistently rewarding work on the arts enhanced by deep Christian conviction, you can't do much better than to follow Steven Greydanus week by week as his career of extraordinary eloquence and insight continues.

My Father's Dragon (2022)

When I was a kid, Disney was the center of the animation world — the most reliable source of wonder and imagination. Later, that center shifted, as Pixar's storytelling set new standards and their animators revealed that so much more was possible. But then, the subtleties and spiritual resonance of Studio Ghibli won my heart and changed my priorities.

And now? Could moviegoers be so lucky as to watch another studio become the epicenter of animation inspiration?

Animators, animation enthusiasts, and cinephiles around the world know that Cartoon Saloon's animated features to date — The Secret of Kells, Song of the Sea, The Breadwinner, and Wolfwalkers — have distinguished them as being one of the world's greatest animation studios, perhaps even making them as important and as influential as Pixar or Studio Ghibli were a decade ago. For me, they've become the new mountaintop. Why? Cartoon Saloon films favor substance over style, and yet their style is so extraordinary that it is, in fact, a kind of substance. In other words, their animation is glorious because it is meaningful; the "look" of their films is always worthy of our close attention, because the design reinforces and expands on the films' themes in imaginative ways.

Nevertheless, I have been bracing for disappointment for the first time — and for good reason.

I flinched when I heard that it would debut on Netflix instead of in theaters. Every Cartoon Saloon feature so far has needed a big screen in order to show off its breathtaking visual complexity, and it was tragic to see their most visually ambitious film of all — 2021's Wolfwalkers — debut on AppleTV+ instead of in cineplexes around the world. (When I finally saw Wolfwalkers in a one-screening-only theatrical exhibition just a couple of months ago, I had my theory confirmed: The big screen show was a revelation compared to my television screen at home.)

Sadly, it looks like this might become the norm.

Another concern? The source material, a 1948 children's book by Ruth Stiles Gannett, is whimsical and funny, and has clearly influenced storytellers for generations, but it's a meandering and episodic tale that lacks a certain gravity. Could Cartoon Saloon storytellers revise it into something resonant? Perhaps. But here they've given the adaptation work to Meg LeFauve, whose most significant credit so far is the screenplay for Pixar's Inside Out (based on a story by Pete Docter and Ronnie Del Carmen). Don't get me wrong — I love Inside Out. But Pixar storytelling has a very different quality than Cartoon Saloon's stuff so far, one focused much more on relentless action and adventure, much less on beauty and mystery.

And while I'd still love to see My Father's Dragon on the big screen, I'm sorry to report that my worries have been well-founded. This is the first film from the Irish animation studio that I wouldn't rush out to see a second time on any kind of screen. It's enjoyable, and I wouldn't hesitate to recommend it to parents looking for new entertainment for their children. But the substance I spoke of earlier — that layered, nuanced narrative complexity that has drawn me back again and again to The Secret of Kells, Song of the Sea, The Breadwinner, and Wolfwalkers, and inspired me to prioritize them as important texts in my classes on art and faith — is lacking here. My Father's Dragon is a whimsical adventure that will have you fondly remembering Where The Wild Things Are and The Neverending Story. But in its improvisational whimsy, it leans too far and too often into mere silliness for the story to resonate with power, and while a lot happens, I can't say it coheres into the sort of poetic storytelling that has been the highlight of those four previous films.

The story begins focused on a boy with a single mother. Shopkeeper Dela Elevator (Paterson's Golshifteh Farahani) struggles to keep her shop afloat just as she struggles to keep her son Elmer Elevator (Room's Jacob Tremblay) ignorant of just how close they are to financial ruin. (We don't know what happened to Elmer's father — or why he had the last name Elevator! Those burning questions go unanswered, even though they seem hugely important.) Their friendly small-town community seems kindly enough, but we don't realize how special it is until things change. Something about the suddenness and severity of Dela's misfortune might suggest to future viewers that this was "pandemic-era" filmmaking and the storytellers were thinking about relevant hardships. Business dries up fast. They struggle to keep the shop afloat, and Elmer proves resourceful, finding things that can be sold to keep their hopes alive. But it's not enough.

We know how this works: In stories like this, home-world details are important in preparing us for the specifics of the fantasy world. We need to understand young Elmer's trials if we are to make sense of anything that happens to him in Wonderland. The size of the previous paragraph should suggest to you that the film invests a lot of time and attention in establishing Elmer's home world. In fact, the context and character development in Elmer's home-world are so beautifully illustrated and efficiently constructed that I found myself reluctant to launch into some kind of Wonderland. Labyrinth makes Sarah's predicament baby-sitting a child she resents suitably miserable so we're excited to leave that nursery. But in the busy-ness of Nevergreen, I found enough intrigue that I would have been happy to stay and watch this kid work things out there on his own. I'm confident that he could have.

Instead, Elmer Elevator ends up whisked away against his will — first under the influence of the (talking!) cat (voiced by Whoopi Goldberg), and second on the back of an overly chatty, high-strung whale named Soda, who looks about as mammalian as a dime-store bath toy. Voiced by Judy Greer (whose involvement in anything is often reason enough to buy a ticket), Soda is aptly named; she's as manic as Pixar's Dory and much more abrasively cheerful. Fortunately, her role is fleeting, as she zigs to an island full of tangerines (which we can tell will be important) and then zags to Wild Island, where it's clear the Main Events are about to unfold.

Elmer, quickly convinced that he needs to bring Boris back home to the Mainland in order to score fame and shop-saving fortune, determines to save the poor creature from captivity. But in doing so, is he dooming everyone on Wild Island to drowning? And what's he to do when his dreams of a magnificent dragon shatter, and he finds himself on the run with a dopey roly-poly whose shape suggests a dog's squeaky toy and whose stripes look like a toddler's pajamas?

The ensuing adventures are never less than entertaining, but they're rarely more than that. Despite Pixar-like histrionics that are merciless in their attempts to make us cry, the movie ends up feeling more like a expensive 90 minutes of baby-sitting for the kids than a meaningful exploration worth revisiting.

Another disappointment: The casting of Matarazzo as the voice of Boris feels like a major miscalculation. The voice doesn't fit the character design. And as it exaggerates the distinctive quirks of Matarazzo's familiar Stranger Things voice, it jars me out of any suspension of disbelief every time he speaks. It's one thing to surprise us with the idea that young dragons are as insecure and as rambunctious as young boys. It's another thing entirely to make a dragon annoying.

The biggest letdown of all comes at the conclusion, when we finally get back to "the real world" of Elmer's home. The abruptness with which matters are resolved suggests that somebody was worried audiences didn't really care about Elmer's mother, the future of their shop, or their relationship with the difficult landlady. It's like they assumed that we would be so enthralled with Wild Island that we'd switch off as soon as Elmer heads home. And that's just not the case.

As I find myself wondering what Elmer has really learned from all of this — something, I suspect, about trusting others to know and take care of their own business. I want to see his adventures translate into meaningful change back on the home turf of Nevergreen. I want to see Elmer Elevator... elevated.

Having said all of this, I reserve the right to change my mind. These are first impressions. So maybe I'm missing something. If so, children, children-at-heart, and parents... let me know what you're discovering in this narrative as your kids watch it again, and probably again, and probably several times more. Are your kids begging for a stuffed Boris or a plastic Soda toy for their bath time?

All Quiet on the Western Front (2022)

Imagine, if you can, politicians who promote nationalism in order to dupe and exploit their citizens. Imagine gullible young men drinking the kool-aid, demonizing their neighbors, and signing up to fight under the influence of hero fantasies.

I could be talking about Russians believing their could easily conquer Ukraine, only to discover that they're governed by egomaniacal fools, and that they are, in fact, outmatched. I could be talking about American soldiers believing they're moving into Iraq to save the world from weapons of mass destruction, only to realize that they are advancing the interests of capitalism on foreign oil fields.

In this case, I'm talking about German filmmaker Edward Berger's book-to-screen adaptation of Erich Maria Remarque's 1928 German-language novel All Quiet on the Western Front.

I've never read that novel, nor have I seen the famous American film adaptation that was released two years later — a milestone in feature filmmaking directed, appropriately, by Lewis Milestone. But I know both by their reputations for running counter to the cliches of most war movies. And, as I've developed quite an allergy to the way the genre often feeds destructive fantasies and glorifies violence, I've been curious. It turns out my suspicion that this one would be different was well-founded. This adaptation — the first German-made adaptation for the screen — is now streaming on Netflix, and it's an outstanding achievement of war-is-hell testimony.

Berger, collaborating with screenwriters Lesley Paterson and Ian Stokell, avoids the most egregious errors of most filmmakers audacious enough to take on such a challenge. The 2022 All Quiet is uncompromising in its depiction of wartime folly: We watcbh young men inspired by nationalist propaganda, recruited into military service with promises of glory, and then dumped directly into chaotic bloodbaths in which millions of them make meaningless sacrifices, their bodies disappearing forever into bogs of mud and carnage, their promise wasted by the whims of clowns and fools. Berger never gives us the luxury of a hero fantasy, a quest formula, or a sentimental turn. Every time we think we might find our way to some note of relief or inspiration, we are denied that comfort. This is not a film that lets us get away with any easy rationalizations. We won't come away thinking about any one character's virtue, or favoring one nation's vision over another. We will come away understanding that the cost to the minds, hearts, and bodies on any side of a war is unconscionable.

When people talk about the original 1930 film, they tend to talk about its battle scenes of unprecedented scale, involving a cast of thousands. It is, in a sense, the ur-text of war movies. Thanks to All Quiet 1930, we've become accustomed to such vast spectacles; they're commonplace in even the most disposable superhero movies now. And though the combat here is dramatized with predictably harrowing realism, I'm impressed by the fact that Berger seems uninterested in any "wow" factor. He's not Christopher "Dunkirk" Nolan or Sam "1917" Mendes or even Steven "Saving Private Ryan" Spielberg, striving to strike us slack-jawed with the shock-and-awe ferocity of front-line fighting. Berger's more interested in keeping us close to a small band of brothers, tuning our attention to their relationships as they slowly awaken to how fully they've been duped into destruction and self-destruction.

Our central character — let's not pretend he's a hero — is Paul Bäumer (Felix Kammerer), a young man whose pack of friends is easily persuaded to put their lives on the line for ideals they believe in, and so he pretends to be old enough enlist. It's almost funny how quickly their enthusiasm melts in the heat of combat as soon as they get out of their transport. Almost. Little do they know that they are pawns now in a game played by leaders with very poor judgment. And no matter how many nightmares Paul survives, no matter how lucky he might be to make it to the finish line alive, he's still under the direction of madmen who may not be willing to follow their own chain of command. General (Devid Striesow), the closest thing to a cartoon in a film that otherwise avoids caricature, would rather spend more lives out of spite, at hardly any risk to himself, than follow instructions to surrender.

Paul's friends are Kropp (Aaron Hilmer), Müller (Moritz Klaus), and Tjaden (Edin Hasanović), and while these are not occasions that help us get to know their histories or personalities very well, these actors all make strong enough impressions that we care about the youthful ignorance of their characters. Eventually they're advised by "Kat" Katczinsky, a charismatic and experienced soldier, played with charisma by Albrecht Schuch. Almost all of the film's best scenes involve Schuch. He's the brothers' anchor, their role model, and the one soldier mysterious enough to inspire their curiosity.

The only face familiar to me in this production is Daniel Brühl's. He plays Magnus Erzberger, the young and squirmy politician leading the German delegation appealing for an end to the slaughter. Thibault de Montalembert makes an impression as French Marshal Ferdinand Foch, who refuses to make it easy for Erzberger.

All Quiet was famously praised in 1929 as the kind of story that just might help save the world from such madness in the future. So it wasn't easy to watch it unfold on the screen while news headlines echoed with the blasts of Putin's 2022 folly in Ukraine, which has similarly deceived and destroyed so many young Russians, to say nothing of the Ukrainians fighting and dying to save their people from cruelty. And it's hard to forget how my own fellow Americans supported sending so many of our own promising young people into Iraq on false pretenses, not so long ago, paying the price of their lives for the sake of oil fields. Alas, art has not saved the world from wars waged by arrogant madmen. Not yet.

That's not for lack of artists trying. I still believe that "the play's the thing" to awaken the conscience of a nation. I think the problem lies with a disinterested audience, one that wants entertainment instead of challenge, one that wants to become intoxicated with visions of power instead of humbled by the truth. Audiences prefer hero stories. Audiences prefer the appealing fantasy that we can change the world with coercive violence if we have "God on our side." Audiences get stirred up by the figure of William "Braveheart" Wallace leading a rebellion against an evil empire in the name of "freedom."

But we need to witness and bear witness to the damage that such seductive storytelling has done... and is doing. We need to see how easily nations can be duped by charismatic schemers and power-mad manipulators. We need to see how fresh-faced young people can be stirred up into a frenzy, eager to go out and fight for glory under the intoxicating influence of national pride. We need to see how generations can be persuaded to ignore evidence and embrace lies solely so they can make their enemies suffer. We need to see how the con men who lead such destructive campaigns could not care less if their lies lead their followers into suffering or death. We need to see such leaders being smug, arrogant, spoiled, stubbornly committed to diseased ideals. We need to attend to these truthful testimonies in art, and we need to talk about how they apply to this present darkness in the world.

And here's another chance to witness and then to bear that witness.

What a relief it was to watch an epic war film that does not serve up some egotistical director's "vision" that is ultimately about proving something or one-upping somebody else. I should never watch a war movie and find myself impressed by the person choreographing the simulated carnage. I should never come away talking about the director or his place in the pantheon of war-movie filmmakers. Instead, I should have my disbelief suspended, my imagination challenged, my heart opened to the possibility of empathy, understanding, and grief. As the great Glenn Kenny writes at RogerEbert.com, "The in-the-trenches tracking shots that Stanley Kubrick crafted for Paths of Glory ... are now steady hand-held digital panoramas of exposed viscera and agonized writhing. Filmmakers have arguably lost the plot, turning 'War is hell' into a 'Can you top this?' competition."

Strangely, Kenny writes this as he finds Berger guilty of just that kind of showmanship. On this rare occasion, I disagree with him. I can't think of a single sequence in All Quiet that jarred me loose from believing what I was seeing, or that made me think about the logistics of the filmmaking. The only other film I found myself thinking about was the Kafka-esque claustrophobia of Son of Saul, a film about a human trapped like a rat in the maze of collective madness. And as I found that film one-of-a-kind in its hellscape storytelling, I mean that as a compliment.

Okay, I take that back. There were a few moments of distraction. The movie's sinister three-pulse motif by composer Volker Bertelmann reminded me of John William's famous Jaws theme, foreboding that everything is about to go wrong. And I frequently found myself thinking "This reminds me of a moment from [Insert Other War Film Title Here]." But then I'd catch myself and realize that those films probably took a lot of ideas from the original All Quiet on the Western Front film — or novel. And that includes the AT-AT attack on Hoth in The Empire Strikes Back! So it's not All Quiet's fault. In fact, this is all to the original's credit.

There was one other moment that jarred me out of my enthrallment. That "Leonardo Dicaprio Points at the Television" meme (you know the one — it's a shot from Quentin Tarantino's Once Upon a Time... in Hollywood) has killed so many moments in so many movies for me. Count this among the casualties, as there's a moment when one worried soldier, looking out at a brief pause in the punishment, says, "It's so... quiet."

Nevertheless, I'm inclined to think this is the first war movie I've whole-heartedly recommended since Terrence Malick's The Thin Red Line (which this movie loudly respects with an early salute to Malick's signature treetop-inclined camera). Peter Jackson's 2018 documentary They Shall Not Grow Old may be the most essential World War One movie ever made. But when it comes to storytelling, this is my favorite war film of the 21st century.

Tár (2022)

I would never say that Todd Field's movies remind me of Terrence Malick's. I don't see a resemblance at all. But I'm inclined to notice this commonality: Just as Malick's first two feature films — Badlands and Days of Heaven — catapulted him into the conversation about the greatest living American filmmakers in the 1970s, so Todd Field's first two — In the Bedroom (2001) and Little Children (2006) — spotlighted him as a force to be reckoned with, an auteur of substantial gifts and unlimited potential. And then, like Malick, he vanished from the scene. Oh, his name kept popping up in exciting rumors — most noticeably in talk about a possible adaptation of Cormac McCarthy's notoriously difficult novel Blood Meridian. But nothing materialized. I've been hoping for his return. And, because of Malick, I've been optimistic. After all, Malick stayed gone for two decades before he returned with the awe-inspiring, all-star epic The Thin Red Line, a film so much greater in scope and complexity that it inspired volumes of critical perspectives and debate. And here, 16 years since Little Children stunned and troubled audiences, Field returns with a movie that represents a leap similar to Malick's in ambition, scale, and stylistic audacity.

Tár certainly looks like a movie that might have taken 16 years to make. It's the sort of event that some cinephiles have been starving for — a film that inspires an animated, wide-ranging discussion regarding all aspects of cinematic artistry, and it will probably keep critics busy ordering second and third rounds of drinks as they argue about its long takes, trouble its tangled web of characters and relationships, tease out its weighty themes, and then shout about whether or not they are frustrated or satisfied by its jarring climax and its lengthy epilogue.

In the cineplex men's room after the screening, I heard two men rush predictably to Oscar predictions. One voice said, "Wow — that was one heavy movie, right?" The other said, "Almost Best-Picture stuff! But there's no way it can win. It's too complicated. Too challenging for audiences. There will be walkouts." "But Cate Blanchett — surely she'll walk away with Best Actress!" "I don't know. Her character is so... so difficult. Even for Academy voters."

Whatever. Awards-talk is pretty much meaningless to me. What I want to know is this: Is the movie absorbing? Beautifully made? Meaningful? (In the Bedroom and Little Children certainly were.) Does it disrupt my suspension of disbelief? Or does it feel more like an ambitious director's appeal to be revered among greats like Paul Thomas Anderson and Stanley Kubrick (for whom Field acted in Eyes Wide Shut) — both of whom I thought about frequently while watching this movie?

And it's too early for me to offer my assessment of the film with any confidence. I can, however, recommend it without any reservations. It's a feast, and a memorable one. It's a feast I'll come back to savor again. But I'll come back because I'm uncertain, because I have questions, because I'm not sure everything here works for me.

Tár is ... a lot. As it follows the career of a rising star in the world of symphony conductors, it traces myriad narrative threads. We learn a lot about Lydia Tar's philosophy of art from an onstage interview with The New Yorker's Adam Gopnick (as himself), who celebrates her landmark achievement in becoming the first woman director of the Berlin Philharmonic. We learn of Lydia's adoration for the composer Gustav Mahler and the maestro Leonard Bernstein, whose flaws she acknowledges but whose achievements she covets. We watch how she approaches teaching Julliard students, an audacious and discomforting spectacle in which she earns wide-eyed fans and vengeful enemies. We piece together her history with her partner and concertmaster Sharon (the extraordinary Nina Hoss, whose supporting performance may be my favorite of 2022). We observe her unorthodox methods of parenting Sharon's adopted daughter Petra (Mila Bogojevic). We cringe as she exploits and abuses her assistant Francesca (Portrait of a Lady on Fire's Noémie Merlant). We watch her struggle with a fierce and sudden infatuation with young cellist Olga (Sophie Kauer). We watch her navigate and manipulate a variety of male colleagues, including an adoring colleague (Marc Strong, even stronger than usual), her predecessor (the inimitable Julian Glover, most famous for facing down Indiana Jones in a quest for the Holy Grail), and her assistant conductor (Alan Corduner). Then there's her insecurity as a composer, her dismissiveness about accusations against her, her obliviousness about the vulnerability of her position and reputation in the face of "cancel culture" attacks, and her fragile mental health. She has vivid nightmares and worse — at time she seems to be tormented by... what, evil spirits?

It's common for an Oscar-season film to run for two-and-a-half hours. It's uncommon for those films to demand such fierce attention from their audiences, to break so many prestige-piece conventions, to weave so many mysterious strands into such a complicated tapestry. Some arthouse films demand a second viewing before a viewer can speak with confidence about their experience. I suspect that we won't arrive at anything like a "critical consensus" on Tár for years. It's going to take two or three viewings before I feel confident writing about what I think of it. But do I love it enough to keep going back?The moviegoing experience that Tár most reminds me of is one of several Paul Thomas Anderson movies that I thought about while watching it. On Letterboxd, I joked that "I didn't know The Master was the beginning of a franchise." This films asks as much of Blanchett as that film asked of either Philip Seymour Hoffman or Joaquin Phoenix, and it tracks a similarly strange and complicated figure — a philosopher, a manipulator, an egomaniac obsessed with legacy — on a rise and a fall. And, like that film, it asks so much of its audience when it comes to making connections and filling in blanks that I suspect it will frustrate as many as it inspires.

But it also reminds me of Anderson's There Will Be Blood, as this performance will probably always be popularly remembered as the defining performance of the lead actor's already prestigious career. Blanchett has been inarguably great since she dominated the screen in Elizabeth (and probably since earlier than that). But the ferocity of her silences, her dominant confidence, and that indefinable characteristic that makes her always seem two or three steps ahead of everybody else on the screen — this has made it difficult for her to "blend in" to movies with casts that are anything less than outstanding. (She was perfect as Galadriel, but Galadriel is supposed to be a dominant and awe-inspiring character.) This role is custom-made for her. The only other actresses I can imagine in the role are Juliet Binoche or Tilda Swinton — no one else commands attention like they do.

And when the film nears its climax, I cannot compare it to anything except There Will Be Blood, as both the narrative and the performance become unhinged in ways that will divide audiences. I'm sorry to say that my suspension of disbelief is badly shaken, perhaps broken altogether, and the moment of peak energy. I can't say more without spoilers, but I'm eager to see it again if only to discover whether another journey with this character makes that dramatic turn more or less convincing. In the case of Anderson's film, I've come to love the conclusion and wouldn't have it any other way. I'm not confident that will be the case with this film.

But I also thought a lot about Anderson's Phantom Thread, as this is a movie about an artist who is uncompromising when it comes to their art but who makes all kinds of ethical compromises when it comes to relationships. But it's also a movie in which prominent mentions of the name "Alma" either directly or quietly make us think of other "difficult" artists who were supported by women named Alma — namely, Alfred Hitchcock and Gustav Mahler.

What other great films did I think about? I mentioned Binoche earlier, and there are several moments in which I think of Three Colors: Blue, which was also about a haunted composer of sorts who has to decide whether or not to make herself vulnerable. Certain moments throughout the film made me wonder if they were direct references or mere coincidences. For example, both films feature a moment in which a woman is drawn out of the safety of her apartment to contend with troubles happening in the apartment building late at night, and the door almost closes — or does close — behind her. I also thought about The Shining, but we'll see if you sense those resonances or not.

I haven't even begun to explore the provocative questions that the film poses — questions about the cost of greatness; the corrosive effect of ambition on relationships; the unnerving frequency with which sublime artistic vision seems inseparable from human cruelty; the naïveté, hypocrisy, and grossly judgmental spirit at the heart of "cancel culture"; and the insensitivity and hard-heartedness that often causes egomaniacs to dismiss their accusers rather than engaging in any self-examination, confession, or reconciliation. No movie I've seen yet in 2022 wrestles with so many of questions currently blazing in the zeitgeist. I will have to postpone my examination of the story's ideas about these questions for another time.

For now, I'll suffice it to say that I've come away from my first encounter with this film more impressed than frustrated. No, it doesn't all work for me — not this time, anyway. When the movie's pent up energy erupts, it loses me. It feels like a miscalculation. And from that point on I'm studying the film; I'm no longer absorbed in it.

I find Blanchett compelling. I find Field's directorial strategies exciting and sometimes virtuosic. What I enjoy most, though, is Nina Hoss's heartfelt performance as Sharon — a woman who, though she is content to let her loved one take the wheel, becomes increasingly troubled by Lydia's driving, and is forced to make difficult decisions regarding when to listen, when to be patient, when to offer quiet counsel, and when to put her foot down and demand to be let out of the car.

I came for the Blanchett greatness. I will come back for Hoss's subtle strengths.

And I'm eager to know what you think of it. You should see it, after all. Because audiences are going to talk. They're going to be argue.

There may not be many Friday-night, popcorn-munching fans. But believe me — there will be essays.

Looking Closer All-Stars: Sarah Welch-Larson on The Rings of Power

I'm aiming to increase my attention here to writers who are "carrying the fire" (to borrow a phrase from Cormac McCarthy's feel-good family-time storybook The Road), writers who are drawing our attention to meaningful blazes in a dark world, and who are doing so with wisdom and wit.

And I'm going to begin with Sarah Welch-Larson. If I see her name on an article, I drop everything to read it. She is influencing my own journey through the wilderness of the arts in meaningful ways.

Welch-Larson, author of Becoming Alien: The Beginning and End of Evil in Science Fiction's Most Idiosyncratic Film Franchise, is writing this week with insight and eloquence (as usual) at her Substack — The Dodgy Boffin — about the new Tolkien fan-fiction series The Rings of Power:

I wish I could quit The Rings of Power. I can’t quit The Rings of Power. The show infuriates me, and I can’t stop thinking about it.

...

I’m not going to get into the side-by-side comparisons between Tolkien’s lore and the show’s versions of events ... but I do think it’s worth getting into adaptations, and how they work, and why this show fails at the task it’s set out to do.

...

It’s possible to tell a complex story with an ensemble cast and multiple story lines woven into one, but The Rings of Power doesn’t do it. There are half a dozen threads in this season, and each one of them gets dropped by the wayside for multiple episodes for no good reason other than time. When those threads are dropped, I never felt the tug toward those characters. There’s no sense of tension about what’s happening off-stage and out of sight; it’s as though the dropped story lines have been left inert because the storytellers got bored with them.

Nothing Compares (2022)

"Do not quench the Spirit.

Do not despise prophecies,

but test everything;

hold fast what is good."

— 1 Thessalonians 5: 19–21

I've been waiting thirty years for this movie.

I've been waiting for an event in art and culture that would bring this inimitable Irish performer back into the spotlight so that the world would have to reckon with what we did to her: how we exalted her voice and image; how we welcomed her onto our stages and screens to thrill us; how we sought to exploit her for our own comfort and self-congratulation; how we rejected her truth when she spoke it; how we turned from her when her prophetic words made us uncomfortable; how we abused and condemned her and dragged her to the pop-culture equivalent of a crucifixion. I've been waiting for the movie that would preach the Gospel of Sinead O'Connor that so many of us have believed since we witnessed her rise (by pop-culture standards) and fall (by pop-culture standards) in the late '80s and early '90s.

I've been waiting for Kathryn Ferguson's Nothing Compares since October of 1992.

And lest that sound blasphemous, let me clarify: When I say "the Gospel of Sinead O'Connor," I mean the Gospel that she preached, the Gospel that she sang, the Gospel that she did her best to manifest. Yes, it's that Gospel — the liberating one at the center of which Jesus Christ shines. It should come as no surprise that O'Connor herself tells us that the record that seized and shook her, that compelled her to recognize her calling, was Bob Dylan's Slow Train Coming, which marks his formal baptism as a prophet in the line of David the Psalmist. O'Connor's Gospel is the Gospel of uncompromising love that speaks truth to power no matter the cost.

I am not here to make an idol of her, to praise her as an ideal; any such praise of any artist would do them an injustice and separate them from our human sphere. But I am saying that we should be grateful for, and reverent towards, how she has been faithful to her calling. For it is in the the mess of her mistakes that we can recognize her authenticity. She is a broken human being who never claimed to be anything different. And if we listen, if we look, we will learn the source of that voice that shakes us, that courage that helps her stand in a spotlight even when an entire arena is thunderous with mockery and hatred. We will learn of her childhood afflictions — the horrific psychological abuse she suffered. We will come to understand the unbridled outrage that offended so many of us, and see that it comes to us as evidence of our own sins. O'Connor has always been distinctive in her honesty. Shocking in her fearlessness. Ruthless in her dedication to making art for the sake of the poor, the neglected, the abused, and the forgotten.

And when, on a Saturday night in October 1992, while my friends and I watched in rapt attention in a Seattle Pacific University dormitory, Sinead O'Connor took that stage, trembling with righteous anger, and leaned into a live-television camera, then tore up a picture of Pope John Paul II, she was not expressing some petty grudge against Christianity. She was calling out the church for its hypocrisy — precisely because of her love for the church and its Gospel. She was shouting to a Christendom that had covered its ears. She was confronting our complacency, our ignorance, our irresponsibility. Most specifically, she was calling out the Catholic church's cover-up of sexual abuse, a truth that in recent years has become undeniable, wreaking havoc on the church's witness around the world in ways we will never be able to measure. I saw, reflected in how she laid down her career and even risked her life, Jesus calling out the "white-washed tombs" of the Pharisees' hearts, knowing where that would lead him.

It scared me. Gospel will do that, when it's done right.

I am so grateful for this film. It "kicks the darkness" until it "bleeds daylight," to borrow lyrics from another Holy Spirit-inspired prophet. What it captures in its net of images and interviews is both tragic and beautiful.

But that won't prevent me from acknowledging that the net itself — the work of filmmaking — is, as movies about artists go, fairly conventional in its craftsmanship. Nothing Compares is not a reinvention of the rock-star documentary. If anything, it's the most conventional release in what has become The Year of the Rock Star on the Big Screen. (See Baz Luhrmann's exhilarating Elvis, Andrew Dominick's daring and intimate Nick Cave doc This Much I Know to Be True, and Brett Morgen's transcendent IMAX Bowie celebration Moonage Daydream.) That is to say, like the party that director Edgar Wright threw in The Sparks Brothers last year, it's made of archival concert footage, intimate interviews, and excerpts from talk-show interviews, much of which will be familiar to O'Connor's fans. And, to fill in storytelling gaps, there are some unremarkable "re-enactments" — fleeting glimpses of models posing as Sinead in various stages of struggle and melancholy, from early childhood to crumpled figures wreathed in cigarette smoke.

Fortunately, the live performances that illustrate her "rise" and alleged "fall" are riveting. The live-TV interview excerpts, featuring the most idiotic of talk show hosts, are as cringe-inducing as any we've seen Bob Dylan suffer. And the overlay of various interviews with O'Connor and her close family, friends, and colleagues are all meaningful. One of the film's most startling aspects is the way in which O'Connor's voice, once such a clarion call, deepens and roughens, a document of the toll the times have taken — or, better, humankind has taken — on her.

But never mind the familiar filmmaking techniques: this form suits its purpose. This is not a fever dream like Moonage Daydream or a specific showcase of songs like This Much I Know to Be True. This film is an argument: a case for the defense. And the argument is a good one. It has taken a long, long time. But Sinead has come through a decades-long shit-show of religious trauma, music industry idiocy, pop culture abuse, and worse... and she’s shining like gold. Love wins — and love is, to all appearances, all that has ever been on her mind and heart.

This is fiercely meaningful stuff, right here, right now — and to me quite personally. I feel like this film is unlocking in me things I need to understand about myself: my own wounds, my own anger, my own grief. Songs I’ve always loved in a deeply personal way ("Troy," in particular) that have nevertheless seemed mysterious… I now understand them as if they’ve been translated into my language the first time. By God's grace, I've never suffered anything like the abuse O'Connor has suffered. But I have become increasingly aware of, and horrified by, the hypocrisy of the evangelical Christian communities in which I was raised. Look at the compromises they justify now. Look at the liars and misogynists and hatred they excuse now in order to make the world in their own image and call it "Christian." So, yes, I recognize something of the trauma, the grief, and the rage that is at the root of Sinead O'Connor's voice. No wonder I've always felt that her music felt more like prayer than rock-and-roll, even before I was awake enough to understand why. And when I did finally see her live in 1997 on the Seattle waterfront, and heard her sing "Fire on Babylon," I knew what it was like to stand in the presence of a prophet as the Holy Spirit does Her mighty work.

If you were between the ages of 16–22 when O’Connor was on magazine covers in the late '80s and early '90s, you should see this movie all the way through to understand yourself, your world, and O’Connor better.

If you’re that age now — I would be so pleased if you would watch this all the way through, to understand yourself, your world, and, perhaps, Billie Eilish better.

This is, in a way, Sinead O’Connor’s late, great triumph. Time reveals the truth slowly. And all those who hastily cursed and mocked her are hereby exposed for their hard-heartedness, their deafness, and their cowardice.

I believe in Sinead O’Connor. I think Jesus does too.

Two new essays in one week: The Enlightened Replicant and the Liberated Marionette

Wow — it's feeling like "the good old days" here at Looking Closer.

I've just had two new essays published in the span of one week, and I'm delighted that they are out in the world ready and waiting for readers.

One is an essay I've been working on for almost two years: "I've Seen Things You Wouldn't Believe: Death-Sentence Testimonies in Blade Runner, Wings of Desire, and Nomadland.

This essay begins as a meditation on aging and learning to accept one's mortality. But it very quickly becomes something else: a deep dive into three very different films that share, I've been delighted to discover, a strange commonality. They all feature scenes in which someone is dying, and that character chooses to spend their final moments reflecting on transcendent moments of vision, moments when they saw something unforgettable.

The second is a reflection on my history with what is often celebrated as Disney's greatest masterpiece: their 1940 animated feature Pinocchio — not to be confused with that awful new "live-action" version from Robert Zemeckis. In this film, too, I find profound meditations on what freedom really means.

I hope you enjoy these pieces. They represent a lot of work during a season of overwhelming responsibilities. I'm so glad I managed to finish them and hit "SEND."

Where Did My Community Go? Marcel the Shell Offers Insight at The Rabbit Room

As you may have noticed, I shared my first impressions of A24's beautiful new film Marcel the Shell With Shoes On a couple of weeks ago.

Then I heard from my friend Matt Conner at The Rabbit Room, the thriving arts-and-faith community that has grown up around the work of brothers Andrew and A.S. "Pete" Peterson. He wondered if I might write about the film for them too. I was thrilled, because my initial post had only scratched the surface of my questions and ideas about the film. And what's more—I miss my friends in the Rabbit Room community! Every time I've participated in their annual Hutchmoot arts festival, I've had a memorably joyous experience.

In fact, thinking about how much I miss that community ended up being the perfect focus for this article about Marcel the Shell.

The piece I composed for them is now front and center at The Rabbit Room. Here's the link. I hope you enjoy it.

The Duke (2022)

Art-theft movies are a popular genre unto themselves. But every movie about someone stealing a priceless work of art from a high-security art gallery must, of course, be measured against what is inarguably the genre's gold standard: No, not The Thomas Crown Affair — I'm talking about The Great Muppet Caper. How does The Duke, the final film from the director of Notting Hill, compare? Let's consider.

This time around, the stolen art is not really the "hook" that will draw audiences in. Who robbed London's National Gallery? Who stole Goya's portrait of the Duke of Wellington? Who cares? No... the hook is this: It's a true story. In 1961, Newcastle taxi driver Kempton Bunton decided to make a big noise about the indignity of being a London pensioner — particularly the fact that the elderly had to pay for access to television. How did he do it? The story is a little more complicated than you might suspect, but not much.

If you're like me, you'll find that there's a better hook than the "Based on a True Story" banner: You'll see this because it stars two of England's finest: the great Jim Broadbent as the irrepressible troublemaker, and Helen Mirren as his long-suffering wife Dorothy.

And even so, you may not be entirely satisfied.

Has any actor been more reliable and stable than Broadbent over the last 30 years? I'd be hard-pressed to think of even a few worth comparing to his consistent record. But Broadbent is in a familiar mode here: lovable, good-hearted, a little dopey, talking to almost everyone like a doting grandfather talks to his small grandchildren. I can't imagine he need to prep at all for this role. Kempton Bunton is a far simpler character, requiring a far simpler performance, than what we've seen Broadbent give as a large-hearted neighbor in Mike Leigh's Another Year, as the master of ceremonies in Moulin Rouge!, or as the resilient John Bayley in Richard Eyre's Iris (which won the actor an Oscar). I always enjoy watching him, but this material is too slight to be remembered as one of his best roles.

All I've said about Broadbent is even more true for Mirren. She's playing a far simpler version of the burdened housekeeper she played in Gosford Park, and while she does a lot with an almost thankless role, it's still not enough to be worth mentioning in a retrospective of her impressive career. I feel a bit sorry for her here. She should be investing in far stronger stuff than this.

And beyond that, well... other than Matthew Goode's reliable sincerity, there's no one here making enough of an impression to give us quotable moments or scenes we'll want to revisit.

It just doesn't feel like anybody is on their A-game here. Even for Michell, a pro at making witty, respectable entertainment, this feels a little too easygoing. It's not a grand finale to his career; it's like an encore where he plays an endearing crowdpleaser with a simple chorus about making the world a better place, one we can sing along to.

The screenplay by Richard Bean and Clive Coleman is amusing enough that this might make for a fine rainy-day Sunday afternoon streaming option for the Masterpiece Theatre crowd. I have no argument with Bunton's quixotic idealism, which leads him to seize his courtroom appearances as opportunities to campaign for a kinder, more generous London. As The Telegraph's Robbie Collin, addressing his fellow Brits, writes, "Although the England it depicts disappeared half a century ago, it speaks mindfully and movingly to our own divided times — asking how institutions should best serve the public that funds them, and speaking up for those who find themselves excluded by class, geography or birth." And I'm all but helpless when Michell ambushes us with the most shameless use of the hymn "Jerusalem" since Chariots of Fire.

"You could dine on nothing but lard for twenty years and still not develop the hardness of heart necessary to avoid being won over by [this film]," claims Jessica Kiang at The Playlist. Well, I don't want to give anyone the impression that I have a heart of stone. But I'm not thrilled I drove for 40 minutes through a torrential downpour on a Sunday afternoon to see this in a theater. If art-gallery shenanigans were what I wanted, I might've been wiser to stay home and watch Nicky Holiday (Charles Grodin) plot to steal the extravagant "Baseball Diamond" from his sister Lady Holiday (Diana Rigg) only to find his plans complicated by Kermit the Frog, Fozzie Bear, and a particularly agitated Miss Piggy. Now that's entertainment!

*Note: The title of my post might be misleading: Michell made a documentary about Queen Elizabeth II that has not yet been released. So, if you're counting non-fiction films, he still has one on the way!

Mrs. Harris Goes to Paris (2022)

Stories of holy fools are tricky to tell.

Take Forrest Gump, for example. He waltzes through his broken world spouting platitudes, proposing that complex conundrums can be resolved with catchy quips and simplistic sincerity, and we are meant to conclude that he was some kind of genius who saw the Truth better than anyone else. Why can't we all be more like Forrest? As a result, the film seems too sentimental, made of too much wishful thinking.

By contrast, Parry of Terry Gilliam's The Fisher King and Johannes of Carl Dreyer's Ordet are clearly suffering from mental illness brought on by trauma. They are not well. And yet, in their not-wellness, they see some things more clearly than others, and we can find a silver lining in their troubled state: In their blindness to some things, they have become sharper in others. These films feel more truthful. They don't insult us by insisting that complicated things are really quite simple.

Anthony Fabian's new film Mrs. Harris Goes to Paris is about a simple woman who brings her smiling simplicity, her basic human decency, and her un-cynical perspectives from the dusty wardrobes of London apartments to the high-fashion world of Paris. And everywhere she goes, she comforts the afflicted and she afflicts the comfortable (or, at least, the seemingly comfortable). Like magic, the world begins correcting itself all around her.

This story, based on a novel called Mrs. 'arris Goes to Paris, has been filmed before, including a TV movie that starred Angela Lansbury, Diana Rigg, and Omar Sharif! I don't have any experience with the book or the earlier adaptations, and this film isn't inspiring me to invest my time in them — so I'll leave it to other writers to consider how this compares to previous manifestations.

The story told here follows Mrs. Harris (Leslie Manville), a war widow who works as a cleaning woman in 1950s London. The excellence in her work makes her seem irreplaceable to her clients, which include the dignified Giles (Christian McKay) and the haughty Lady Dant (Anna Chancellor). Nevertheless, she is not entirely satisfied with her life. When she discovers an extravagant dress with a Christian Dior label, its beauty takes up residence in her imagination so powerfully that when she stumbles into some good fortune she determines to make her way to Paris to buy one of those fancy dresses for herself.

The plan strikes her friends, including the loyal Vi (Ellen Thomas in the clearest example of tokenism I've seen in a movie in a while) and the charming Archie (Jason Isaacs), as audacious. But Mrs. Harris is done with living cautiously. She can't see any reason why she cannot waltz into Paris and claim such a classy commodity for herself. What she cannot imagine is that she will soon make as powerful an impression on the workers at Christian Dior as their artistry has made upon her. And, like the famous Mr. Smith who goes to Washington and comforts the afflicted while afflicting the comfortable, her moral character will spark a revolution.

Mrs. Harris Goes to Paris is somehow scoring 95% "fresh" with critics on Rotten Tomatoes even though Fabian's last film earned only 13% — and yet, reviews are using a lot of the same words to describe both films: "Hallmarky" and "saccharine," for example. I'm a bit baffled by the positive response. It's such broad-stroke entertainment, so eager to please, so well-meaning, that Paddington Bear could have a supporting role and audiences might not even blink.

But Paddington is meant for children. I don't mean that as a criticism — the film adaptations (expansions, really) of the classic children's stories have set such stunningly high standards in writing, acting, and all aspects of design that they're delighting children and adults alike and bringing all of them back for multiple viewings. They're excellent films that fulfill the highest potential of their genre.

This? I'm not sure who the intended audience for this is. It's as much of a well-meaning fantasy as Paddington, but it's rarely more than mildly amusing, and it's clearly not crafted for kids. If this had been released on Mother's Day, it would have been the perfect confection for adults to take their mother to... if their mother's taste in entertainment was such that an episode of PBS's Poirot would be too "grim and gritty" for her.

I went to see this because I love Leslie Manville. Her turns in Paul Thomas Anderson's Phantom Thread and Mike Leigh's Another Year are pure gold. She's great. She could replace Nicole Kidman in the AMC Theaters promo, read that same script, and convince me that she means it.

What's more – I love a good movie about an innocent character with good intentions... so long as the movie doesn't glorify ignorance and lie about the complexity of the world's problems. Mrs. Harris Goes to Paris has plenty of heart, but lacks the courage of its convictions. It doesn't have the guts to honestly represent any kind of problem, or to develop human characters with foibles that are any more than mildly and momentarily aggravating. It’s like Mike Leigh’s Happy-Go-Lucky if it had been directed by Ron Howard at his sappiest. By comparison, Spielberg’s lovely The BFG — another film that dares to be childlike with adults in mind — seems dark, dangerous, and downright subversive. This movie practically dares you to scoff at it; it feels like a judge is watching you watch the movie, poised to find you guilty of cynicism if you flinch.

And just as Mrs. Harris, making notes about her savings, writes in huge letters and underlines them, so every moment in this movie is played like a major chord, and loudly, as if the filmmakers are straining to set some kind of Olympic record for sincerity. Minor chords register only as mild, fleeting variations in the tone — brief misunderstandings, the slightest bit of complication, the merest obstacle for Mrs. Harris to overcome — so that we can have a sense that a narrative is, in fact, progressing.

Another challenge to the viewer is the version of Paris on display here. If you saw Edgar Wright's Last Night in Soho, you saw a young woman suckered into a nostalgic vision of Paris, and then she paid the price by discovering that if you scratched those fantasies you'd expose horrific corruption festering under the skin. This movie insists on the idealistic fantasy, acknowledging real problems only as troubles that can be overcome as easily a puffing seeds off a dandelion. There’s not a spot in this film's Paris that hasn’t been polished to avoid offense. Come to think of it, it's like a Paris version of that pop-up book of London that figures largely in Paddington 2. This tourist's fantasy of the city so resolutely ignores — denies — any significant flaws, injustices, or dark sides that you’ll wait for Mrs. Harris to wake up and learn it’s all been a dream.

So — and brace yourself for a surprise twist here — it says something about how disappointing, lurid, corrosively violent, and cynical the world has become that the whole audience (including me!) enjoyed this film. At least, that's what it felt like in the theater. With the exception of one young man on a date who, sitting in front of me, recoiled from the screen as if suffering a severe allergy, the audience seemed under a spell. There were gasps of delirium at the revelations of the Christian Dior dresses. There were tears whenever Mrs. Harris was the slightest bit inconvenienced. There were cheers when the inevitable fairy-tale dreams came true.

This movie's like a very expensive wedding cake in which all of the money and effort has gone into the extravagant frosting, but when you cut into it, you find that it's just a few stacked cupcakes with little substance to speak of. And yet, somehow, it all manages to hold its shape without collapsing under the weight of the decoration. And you end up admiring it for what it is: an impressive artifice.

Who can begrudge audiences a plate of hyper-colored meringues after two excessively fatty, unbearably greasy Marvel movies this summer?

And, if you think about it, there’s no less wishful thinking and fantasizing and denial in Top Gun: Maverick than there is here. Different versions of the same thing: escapism that appeals to the most audacious dreamers among us, and that works overtime to keep us from asking any questions that might spoil the illusion.

Mrs. Harris is not my idea of a holy fool we can learn from and admire. She assures us that a very broken world can be repaired with just some common sense and kindness, and that's hard for me to stomach right now as I watch generations of blood-sweat-and-tears goodness erased by ignorance and cruelty.

But I'll bet Paddington Bear would love this film. He'd probably quietly admit, in his most Whishaw-ish half-whisper, that has now has a crush on Leslie Manville. He'd lean out his window at night and make a wish, and the BFG would show up and carry him off to Paris to see a Christian Dior runway show.

Did I mention that, adding to the "How does this movie exist?" mystery of it all, this thing includes fully committed performances from the great Isabelle Huppert and distinguished Lambert Wilson?!

- - -

Note: I wrote these impressions down in the theater as the credits rolled. Then I came home and, out of curiosity, looked up the New York Times review, only to be startled to see Paddington mentioned in their review's subheading! And here I thought I might have made an inspired comparison. (Sigh.) Oh well.