Overstreet's Favorite Films of 2022 — Part One: Honorable Mentions

The Super Bowl is over.

Valentine's Day has passed.

The Oscars are coming!

And I've already seen some of 2023's new releases.

I guess it's time for me to make up my mind and share my list of favorite films from 2022.

This post was previously published at Give Me Some Light.

Subscribe for free today!

Sign up for a paid subscription at you'll have access to even more!

As my longtime readers know, I don't like to rush things. I'm unwilling to join the circus of film reviewers who rush to post their favorites list in November, when there are still several weeks of movies that haven't yet been revealed. And even if I could see them all by November, I wouldn't have the time necessary for reflection, for reading others' perspectives, for (in some cases) second viewings. I like to give art time. Because there's so much going on in a good movie that isn't immediately evident. Thoughtful interpretations and assessments take a while to compose.

So, even though my opinions will continue to evolve, I'm ready to share the first of three posts highlighting the films released in 2022 that I found to be worth seeing and recommending.

2022 was full of unexpected highlights, many singular and strange. But where last year I couldn't decide between my three favorites, this year I have a clear #1 pick, great confidence about my Top Five, and after that it starts to get blurry.

Part One of this series — the "Honorable Mentions" — will be listed alphabetically instead of ranked. It's a long list of films I recommend highly, even if I didn't admire them enough to rank them at the very top. If you follow the links for each, you'll my first impressions, interpretations, and reflections in more detail.

And hey — why not post some information about your own favorites of 2022 in the Comments? What am I leaving out? What have I missed that I need to see?

A Hero

https://youtu.be/zAJ6_lmr_HQ

- Director and writer: Asghar Farhadi

Farhadi's cinema is a moral X-ray machine so fine-tuned that his narratives leave me at a loss for words unless those words come from the Scriptures. And this film — is it worth saying :one of his finest" when so many are so great? — is no exception. It shows us the folly in exalting anyone's righteousness. When we make a hero of human beings, they will likely then suffer the kind of scrutiny that will expose their humbling faults — and that, in this world of reactionaries and bullies, might end up doing them more harm than good. Worse, the simplest act of goodness can be so easily exploited by others.

Love your neighbor quietly. And pray your love doesn't attract attention. It's blood in the water for the devil’s sharks, including those within within your own heart.

Saleh Karimaei, the boy who plays Siavash, would have made Abbas Kiarostami weep. Farhadi knows the best way to break our hearts over the failures of adults is to place a child among them and let him watch, with dawning horror, how corrupt his elders really are.

Belle

https://youtu.be/izIycj3j4Ow

- Writer and director: Mamoru Hosoda

With animation so dazzling that it's easy to suffer through the movie's patience-testing duration, Belle gives us a clever re-contextualization of Disney's Beauty and the Beast. In fact, the homage is so blatant — especially in the design of the Beast's castle and the choreography of his turning-point encounters with Belle — that I'm surprised I haven't read about any tension between Disney and Studio Chizu. There is so much, light, color, and extravagance, I was often awestruck. And I recommend you see it on the biggest, brightest screen you can. But, as with so much anime, everything is so big, so overblown, so obvious, it's hard not to come away feeling that stronger writers could have made this a masterpiece.

The Black Phone

https://youtu.be/3eGP6im8AZA

- Director: Scott Derrickson

- Writers: Scott Derrickson and C. Robert Cargill

It's so much more engaging, and it's about so much more, than most movies about serial killers, I was pleasantly surprised. … Contrary to what I might have expected from reading the early reviews, I like the young actors and how their performances gave this a surprisingly comic undertone throughout. Contrary to the approach of so many horror films, including Derrickson's own Sinister, the enemy is not made to seem invincible or awe-inspiring, but is actually something of a buffoon; The Grabber reminds me more of the Coen Brothers' approach to killers than other Blumhouse icons, and that's a good thing.

James Ransone FTW.

As a "period piece," this looks and feels just right.

Both Sides of the Blade

https://youtu.be/OBTJTtOiuzg

- Director: Claire Denis

- Writers: Christine Angot and Claire Denis, based on Agnot’s novel Un tournant de la vie

We want freedom from control, but we can’t stand the idea of losing our influence over others. Is the ache of heartbreak from the loss of the Other, or from the loss of the desire the Other has for us? This isn’t a movie about love, really. It’s a movie about phones and credit cards, and the charade of virtue we put on to seem noble until somebody takes our power away. We don’t want to be told we can’t. That’s the hurt that shows us who we really are: utterly dependent. And, if we’re not careful, spoiled rotten.

[For more substantial reflections: Darren Hughes' notes from Berlinale.]

Bullet Train

https://youtu.be/0IOsk2Vlc4o

- Director: David Leitch

- Writer: Zak Olkewicz

I've been missing well-made action comedies. Since Edgar Wright moved on from the Cornetto trilogy, I've been wondering who would step up and seize the opportunity. Bullet Train isn't as strong as any of those three films. Wright's films earn 'A' grades on every count, while Leitch's film here is 'B'-grade on most counts. Wright knows how to sustain a very tricky balance: He can weave meaningful character development and thoughtful thematic exploration into his action, while also celebrating and innovating on genre cliches, and somehow avoiding irresponsibly gratuitous violence. Leitch isn't nearly as ambitious and doesn't seem to be as gifted — Bullet Train has some playful comments about luck and fate along the way, but there's not much to discuss afterward. What it does have is a feast of dazzling, tongue-in-cheek action sequences, and some very clever braiding of plots and subplots. As an exhibition of slick craftsmanship, it's consistently impressive and engaging.

Corsage

https://youtu.be/P7LpMtLRe2E

- Writer and director: Marie Kreutzer

There are fleeting images of bodies of water here that I will remember more than anything in The Way of Water. And there is a quiet image of the Empress alone at a table holding a teacup that I find more striking than any image in the box office top 10 this year. And forget the dance in Wednesday — give us the closing-credits Krieps.

Cyrano

https://youtu.be/5e8apSFDXsQ

- Director: Joe Wright

- Writer: Erica Schmidt; based on her 2018 stage musical of the same name, which is based on Edmond Rostand’s 1897 play Cyrano de Bergerac

- Music: Aaron and Bryce Dessner

Notes:

I’m always impressed by Peter Dinklage. I’m always moved by this story. And the decision to switch Cyrano’s affliction from a prominent nose to achondroplastic dwarfism works better than I might have guessed. But overall, the most interesting aspects of this were the Dessners’ forays into making a familiar story into a big-screen musical surprising enough to move us all over again.

Here’s Steven Greydanus’s detailed review, which is so good it makes me want to see it again, even as it makes me content to recommend it rather than attempt anything so substantial myself.

Elvis

https://youtu.be/Gp2BNHwbwvI

- Director: Baz Luhrmann

- Writers: Baz Luhrmann, Sam Bromell, Craig Pearce, Jeremy Doner

If you don't like Baz Luhrmann films, this won't change that. If you like The Great Gatsby and loved Moulin Rouge! as I do, you'll have a good time with this. . . . This is the story of two men: one, addicted to gambling; another, addicted to attention. It’s a tragedy for both, given the gifts evident in both of them. And, as dealmaking and showmanship are two of America’s most notorious strengths, this shows you where it’s all headed. . . . How long until Butler plays John Travolta in a biopic that gives a lot of attention to Saturday Night Fever?

Emergency

https://youtu.be/FVi9hlvQOrg

- Director: Carey Williams

- Writer: KD Dávila

Here’s my full review at Looking Closer.

Emily the Criminal

https://youtu.be/Xzf1YCEkLDI

- Writer and director: John Patton Ford

Tense and efficient and surprisingly uncomplicated, Emily the Criminal makes for a suspenseful 90 minutes that feel more like 60 or 70. Shot with a lot of effective, tight, handheld close-ups, it feels immediate and convincing.

…

Aubrey Plaza and Theo Rossi are both very good here, and perhaps the best compliment I can give them is that they develop some impressive, engaging chemistry in very little time. I've been a big fan of Plaza since Parks & Rec, but I've been disappointed in the variety of movies she's been in so far. This feels like a giant step in the right direction.

The Eternal Daughter

https://youtu.be/5hJR8hEsLZU

- Writer and director: Joanna Hogg

Some surprisingly Lynch-ian vibes here in what often feels like a low-key take on The Shining. A haunting whisper of a film, as ethereal as a wisp of fog blurring the moon. As one compelled — uselessly, really — with an insatiable desire to impart happiness to my parents, and often feeling that my efforts have backfired, I really feel this movie.Tilda Swinton: 2022 MVP. This is my second-favorite Swinton-Lost-in-a-Soundscape film of the year. Can this surprisingly enchanting new genre become a biannual event?

Glass Onion: A Knives Out Mystery

https://youtu.be/-xR_lBtEvSc

- Writer and director: Rian Johnson

That's entertainment. And it's also therapy for those exasperated Americans who, over the last several years of insurrection, authoritarian narcissists, and billionaires-gone-bananas, have felt like they've been taking crazy pills.

I need to put my past misgivings about The Bloom Brothers and Looper away and admit that, at this point in his career, Rian Johnson is an undeniable force for good in the world.

And not just because he's given Kate Hudson her best role in 22 years. Not just because Edward Norton is fun again. Not just because we can put Antebellum behind us and be excited about the camera's love affair with Janelle Monáe again. Not just because this has several of the cleverest surprise cameos any director has ever pulled off (I mean, the flex this guy is showing off right now).

But because, as much of a three-ring circus of hijinks and fun as this is, it serves up so many meaningfully cathartic laughs about things that deserve to be laughed at. Others have already marveled at the seeming prescience of this film's script given what we're seeing in the headlines this week. But just... wow. I needed this movie so much.

God’s Creatures

https://youtu.be/fyOk1QVDlsI

- Director: Saela Davis and Anna Rose Holmer

- Writer: Shane Crowley

Holmer and Davis … elevate this material, drawing out yet another extraordinary performance from the great Emily Watson (who doesn't get nearly enough leading-role work these days), and finding in Paul Mescal's performance some of the same chemistry of boyish charm and deep shame that makes him so magnetic in Aftersun.

…

[A]s an intense immersion in a persuasively constructed Irish coastal community, and as one of this year's several brilliant portraits of "women talking" (or, in this case, not talking) about men's violence, this is a film that will stick with me. And I'm delighted to find that these filmmakers eschew the prevalent cynicism about the role of faith in a community, showing it to have a powerful influence on those who refuse to cast their conscience aside for the sake of self-preservation.

Hit the Road

https://youtu.be/6PTz6Dzsv6A

- Writer and director: Panah Panahi

Here’s my review at Looking Closer.

The House

https://youtu.be/wqbZlAEUb5w

- Directors: Emma de Swaef, Marc James Roels, Niki Lindroth von Bahr, Paloma Baeza

- Writer: Enda Walsh

For a movie about the soul-threatening perils of investing your love in a temporal thing, this film is a testimony to the near-miracles that become possible when we invest our love in temporal things. What awe-inspiring animation this is!

And yet, it's a film that most will find difficult to love, as we try to make sense of why the cast of characters are first manifested as human, then as rats (and other vermin), and then as cats. The deliberate unpleasantness of the tone is as abrasive as some of its characters' fabric.But I'm not one to write off a movie for making me uncomfortable. The unease of great horror is deliberately and purposefully cultivated, and can be a path to wisdom. I'm convinced that the storytellers are doing meaningful work here, but this is a tough trilogy to interpret with confidence.

Kimi

https://youtu.be/_Gr2zXuEBL0

- Director: Steven Soderbergh

- Writer: David Koepp

Notes:

A high-energy COVID-19-lockdown take on Rear Window with a strong lead performance by Zoe Kravitz and a surprisingly non-cynical take on in-home technology and artificial intelligence. And I had a lot of fun seeing my city look so sleek and shiny as our hero dashes through it and dodges her sinister stalkers.

Murina

https://youtu.be/fC2sUO6xhOA

- Writer and director: Antoneta Alamat Kusijanović

I've finally found a movie adaptation of The Little Mermaid that I love.

Nothing Compares

https://youtu.be/-VLy1A4En4U

- Director: Kathryn Ferguson

- Writers: Eleanor Emptage, Kathryn Ferguson, Michael Mallie

Here’s my full review at Looking Closer.

The Northman

https://youtu.be/oMSdFM12hOw

- Director: Robert Eggers

- Writer: Sjón and Robert Eggers

Here’s my review at Looking Closer.

Official Competition

https://youtu.be/3b0ZYBmST-U

-

- Directors: Mariano Cohn, Gastón Duprat

- Writers: Mariano Cohn, Andrés Duprat, Gastón Duprat

Imagine a more sophisticated version of Dirty Rotten Scoundrels, set this time in the world of arthouse filmmaking, with the two competitive rival Scoundrels being egomaniacal leading men with very different methods of acting. But this time, the woman they're both drawn to is in charge from the get-go — she's the director who wants them to act opposite one another as feuding brothers in a major motion picture, and she proves to be just as aggressively contentious as the two of them.

...

I miss comedies that remember to use the whole screen. I miss comedies that expect their audiences to be intelligent. I miss comedies that use silences and body language cleverly, instead of just delivering written jokes. I miss comedies in which jokes have two, three, even four stages of detonation.And I miss sophisticated comedy performances like these. All three leads are fantastic, and José Luis Gómez is particularly funny in a dry, subtle supporting role as Humberto Suárez, a multi-millionaire monster who, knowing he's hated for being heartless, wants to reinvent himself as a gift to humanity by producing a meaningful film based on a Nobel-prize-winning novel.But this is Penélope Cruz's show, above all, and she is sensational. I want to see her doing more of these ambitious comedies. Few actresses would be able to give a complicated performance in a wig as spectacular as this one, but she is glorious.

Prey

https://youtu.be/wZ7LytagKlc

- Director: Dan Trachtenberg

- Writer: Patrick Aison

In this Predator prequel, which might as well be called Episode One: The Phantom Menace, the New Mexican Aubrey Plaza — Fort Peck Sioux tribe member Amber Midthunder — catapults to the front lines of action stars with a supremely confident and engaging performance and achieves what might be the most difficult thing to do in a Predator movie: She steals the movie from the alien and makes me want to see more movies about Naru instead of any soulless, roaring, extra-terrestrial bigfoot.

I approve. Since franchise installments apparently must be made endlessly as long as there is money to be made from the fans who are addicted to the familiar, why not spice them up with something thought-provoking? Why not ambush audiences with some aesthetic beauty and some provocative undermining of genre tropes? Why not do what you can to wake a few viewers up to how much better movies can be, and make a few a little more willing to loosen their ignorant assumptions about gender? Why not try new things?

P.S.

I mean, I knew Malick's The New World would be influential. I never dreamed it would inspire this.

She Said

https://youtu.be/i5pxUQecM3Y

- Director: Maria Schrader

- Writer: Rebecca Lenkiewicz

This is a much stronger film than the trailer or the early buzz led me to believe. Sure, it's somewhat formulaic. And yes, it's hard to make a film about journalists working hard to reveal the truth without having them say obvious things about truth-telling. We've seen so many of them. Spotlight may deserve to be celebrated for greater artistry (as does Dark Water), but I think it won its Oscars in part because of good timing and a long highlight reel full of flashy Oscar Moments (particularly one featuring Mark Ruffalo that had me cringing in the theater). She Said impresses me just as much, if not more — it's just as urgent and relevant, just as suspenseful (even if you know the story), and it never feels like it's straining to win awards. And while it's about one man who is now in prison, it's also about many, many other men who aren't — not yet, anyway. I wish I could convince everyone I know to see it and share it.

. . .

Now, I admit that I may not be the most objective critic on this film.I know quite a few women who are journalists. And I was caught up in a recent drama in which a powerful man pulled all the strings he could to silence many "she saids" that represented women who were very close to me, women I count as trusted friends and model of integrity. How could I watch this and not be aggravated, upset, inspired, and (if you will) evangelical about it when it's over? I'm thinking about how this film might (if anybody sees it) inspire others to fight for similar surges of truth-telling to overthrow other abusers in power.

. . .

What's best — She Said isn't a courtroom drama. It doesn't revel in the truth-tellers' victories. It's a journalism drama — a movie about work. It may not represent what life is really like at The New York Times... I don't know. But it doesn't romanticize what journalists do. While it abbreviates a great deal to fit the story into a two hour span (I'm sure this is a case of "The book is so much better," because of course it is), it represents the long hours, the hard work, and the cost to every aspect of journalists' lives. And, specifically, the sacrifices that many women in journalism make remain front and center.

Stars at Noon

https://youtu.be/Yg3EQ1_zRow

- Director: Claire Denis

- Writers: Claire Denis, Léa Mysius, Andrew Litvack; based on the novel The Stars at Noon by Denis Johnson

As unconvincing as the political drama and intrigue of mid-'80s Nicaragua might be here, the film's focal characters touch something true: It’s remarkable how much we will rationalize in our desire to be known, to be needed, to feel purposeful. When the world rejects what we have to offer, we might be surprised how many compromises we can live with if it means we get a taste of being loved… and of loving. Or of something close to that.

. . .

Denis is so patient, so focused on craft, so uninterested in anything conventionally "entertaining," so preoccupied with quiet rhythms, so attentive to capture moments of persuasive human expression. She knows what so many great filmmakers know: that there is no subject more enthralling than the face of a human being deep in thought. She has been prolific in recent years: High Life, Let the Sunshine In, Both Sides of the Blade. All of those films are compelling explorations and playful variations in her style and themes. I admire them. But this... this feels like a return to her strengths. It took me mere moments to relax into that rare feeling of being on an adventure with a master director, one driven by questions and intent on discovery.

The Territory

https://youtu.be/wL9wvdbk7A4

- Director: Alex Pritz

Trigger warning for survivors of religious trauma: You will watch as men pray in the name of Jesus for blessings upon their work, and then they will turn and chainsaw their way into what's left of the heart of the world; they will unleash hell on a vulnerable community; they will (allegedly) commit murder; they will render "law and order" meaningless so the natives have no one to call for help; and they will speak without any shame at all about God has given this land to them.To watch these cruel and compassionless capitalists slash and burn their way through so much Amazon rainforest beauty is harrowing to behold. (And it's made all the more sickening in that I'm watching my own country on the brink of surrendering control to the same kind of merciless, arrogant fools.)

This Much I Know to Be True

https://youtu.be/o-f8HDIs6uM

- Director: Andrew Dominik

A perfect match of filmmaker and musicians.I saw Cave and Ellis live at the Paramount in Seattle a couple of months ago — a dream come true — and I'm still shook.

But where that was a rare case of a thunderous, rigorous, riveting communion between artists and audience — an experience that felt like a monsoon — this is an intimate journey into an private arena where artists are confronting cosmic questions, grieving unfathomable losses, and wrestling angels at risk of their souls. It's like watching spiritual warfare manifested as mixed martial arts matches.

In one sense, the film is about a unique and fruitful collaboration between two singular talents, but in another sense it's almost like Ellis is providing Cave with exactly the right sphere in which he can sculpt his anguish and his faith, giving shape to his unspeakable wounds and offering companionship and consolation to the lonely and desperate souls who write to him asking for guidance.

Three Minutes: A Lengthening

https://youtu.be/I8RprTU0hXY

- Director: Bianca Stigter

- Based on Three Minutes in Poland: Discovering a Lost World in a 1938 Family Film, by Glenn Kurtz

I love Bonham-Carter, but her presence here was, for me, an odd distraction in an otherwise profound exhibit of curiosity, detective work, academic inquiry, visual experimentation, and moral vision. Short enough to show during a typical class period, it will become a favorite for professors and teachers intent on making sure new generations of students know that the Holocaust was real and that bearing witness matters. It’s also an impressive display of finding a whole world in a grain of sand — or, in this case, three minutes of grainy footage.

Three Thousand Years of Longing

https://youtu.be/TWGvntl9itE

- Director: George Miller

- Writer: George Miller, Augusta Gore

George Miller's The BFG (for adults) with heavy doses of Terry Gilliam's The Adventures of Baron Munchausen and Tarsem's The Fall, and a tone that reminds me of Jean-Pierre Jeunet.I've now seen two new films in 2022 in which Tilda Swinton plays an eccentric who bonds with a strange man and, through an intimate touch, shares with him communal perception of other dimensions.

...

There's so much to enjoy all the way through. Swinton is Swinton-ing all over the place. ... Elba, by contrast, is surprisingly otherworldly and yet affectingly human at the same time — an unlikely but inspiring choice for this character. The fantastical stuff gives us some glorious images I'm so glad I saw on a big screen, but the scenes that are just about Swinton and Elba in white terry-cloth bathrobes sharing stories in a hotel room are every bit as savory and delightful. I could have listened to them talk all night.

Turning Red

https://youtu.be/XdKzUbAiswE

- Director: Domee Shi

- Writers: Julia Cho and Domee Shi

I appreciate how this one shows Pixar embracing animation less as an opportunity to dazzle us with how "lifelike" anything is and more as an opportunity to play. It's not as brave among Pixar movies as The Emperor's New Groove was among Disney animation features, but it has something of that film's recklessness. It also bears (AUGH!) witness to the influence of both Miyazaki and Aardman on the creatives — which is a good thing. And — perhaps best of all — it knows when to quit (something I unfortunately can't say about The Mitchells vs. the Machines, even though that's an unpopular opinion). It felt shorter than its hour-and-40-minute running time.This is a promising move in a new direction for a studio that has, for me, lost something of its magic over the last three features.

We’re All Going to the World’s Fair

https://youtu.be/d4s7v7djmBM

- Writer and director: Jane Schoenbrun

A re-imagining of one of horror's most fundamental texts — the confrontation between Clarice and the behind-bars Hannibal Lecter. But in this case, "Casey" – the film's Clarice – is trying to find the clues she needs in order to track herself down, in order to find out who she really is and how to cope in a world that has forced her into isolation. And "JLB," who we're conditioned to assume is a Hannibal Lecter just waiting to feast, is actually just a lonely guy — one whose strategies are dangerous and, for some, ultimately destructive.

But as "Casey" comes to JLB needing guidance and attention and affirmation, the other recognizes something in her, and the intimacy that forms between them transcends the templates of horror and becomes a rare and inspiring example of how Love Your Neighbor breaks down binaries. The game can go wrong depending on how it is used, but it can also become a language through which we cultivate real and redemptive relationship. And the game master is not a monster after all. I can feel the good in him.

Here's to a "horror" film that isn't about perpetuating horror by endorsing coercive violence against an Other, but rather seems to have a genuine interest in the cure for all horrors.

White Noise

https://youtu.be/SgwKZAMx_gM

- Writer and director: Noah Baumbach

- Based on the novel by Don DeLillo

Is White Noise Noah Baumbach's most hopeful film?

I'm not sure. But it's certainly his most imaginative and ambitious. He's pushing himself beyond his comfort zone into a very discomforting world of clashing modes and tones: chaotic Altman-esque family activity; Coen-Brothers-esque quirky supporting characters (the doctor, the mad TV-wielding prophet); Coen-Brothers-esque dark prophecies (a la A Serious Man); truly bonkers higher-education satire (Were college professors really this insufferably theatrical in the early '80s?); prophetic grim comedy (the traffic crashes and Millers-vs.-the-Machines family-car-in-slo-mo-flight); Marriage Story drama; and... sudden bursts of song and dance?!

The Woman King

https://youtu.be/3RDaPV_rJ1Y

- Director: Gina Prince-Bythewood

- Writer: Dana Stevens

Very surprising.

The lead performances are stronger than I anticipated: Davis as the general Nanisca, the strong hand of King of John Boyega's King Ghezo, is a more inspiring leader than Viggo Mortensen's Aragorn, Chris Evans's Captain America, or Mel Gibson's William Wallace. But I'm stunned to find myself wondering if her performance is the strongest one here: Both Thuso Mbedu (as the young trainee who is arguably the lead) and Lashana Lynch as Nanisca's fearsome and charismatic "power forward" Izogie are compelling whenever they're onscreen.

The violence is more visceral and chaotic than I anticipated, riveting in its energy and in the ways that dance in incorporated without disrupting the style/substance balance of the battle scenes.

And the weave of character arcs is more complex and affecting than the trailers hinted at.

The Wonder

https://youtu.be/htybz7XscIY

- Director: Sebastián Lelio

- Writer: Emma Donoghue, Sebastián Lelio, Alice Birch; based on the novel by Emma Donoghue

Here’s my full review at Looking Closer.

To be continued!

Check back for the "Runners-Up" post and the Top Ten over the next few days.

Or, subscribe to Give Me Some Light and access those posts right now!

Is this the "best first film" for very young children?

In the very first moment that the Horse appeared in the snowy woods, Anne pointed at the screen as if momentarily possessed by the spirit of Leonardo DiCaprio and shouted: "There it is, Disney! Finally! That is how you animate a horse! How hard can it be?"

You can watch it too if you have access to Apple TV+.

Based on the lavishly illustrated children’s book by Charles Mackesy, this Oscar-nominated animated short comes to us from co-directors Peter Baynton and the author Mackesy himself. And I'm not sure, but I'm inclined to say this is a strong candidate for Best First Film For Parents to Watch With Their Toddlers.

The characters are sparingly drawn, but endearing in ways that will probably remind everyone of Christopher Robin, Pooh, Piglet, and Eeyore. They’re even slighter than that, really — so simple that they’re in danger of dissolving into something like a mood or a sigh or a gust of wind. Think of The Little Prince or The Giving Tree, and you’re in the neighborhood. The thing that may spoil it right away for some viewers is that each character seems to come equipped with a kit full of platitudes that they cannot wait to offer. I’m not proud of it, but I cringed at more than a couple of lines as the Mole (voiced by Tom Hollander), the Fox (Idris Elba), and the Horse (Gabriel Byrne) kept on delivering tidy bits of wisdom at the slightest provocation, their distinctiveness seeming to blur into a common Voice of Counsel.

And as the world seems increasingly cruel every day, the grace of this movie’s pace and style, and lessons half-whispered all along the way might be the kinds of things that sink into a small child’s psyche and give them an appreciation for a more meditative kind of art. They might even serve, as they did for me and for Anne last night, as a sort of Sabbath devotional, reminding our weary adult minds and hearts of things we would tell small children if we found them as troubled as we are.

Living (2023)

All hail the great Bill Nighy, who has been nominated for Best Actor in the 2023 Academy Awards for his performance in Living.

And rightly so! Living is a lovely showcase for Nighy's singular screen presence. It's also a reverent — too reverent, actually — homage to Ikiru that, running almost 40 minutes shorter than Akira Kurosawa's 1956 masterpiece, moves through the phases of its protagonist’s epiphanic redemption too quickly. It's almost as if a British film professor, underestimating his young film students, decided to produce an abbreviated remake of his favorite classic of post-war Japanese cinema and convert it to his students’ own language (to spare them the subtitles), cut its duration by a third (to avoid testing their patience), and make the point of each episode extra-clear (so they could easily explain what it means in their essays).

As a result, the characters here all seem one-note, the sort of cartoonish British stereotypes we encounter in a lot of BBC dramas that seem custom-made to reinforce American assumptions, in spite of the fact that they seem to be living in a particularly beautiful period recreation of post-war England.

If you know Ikiru, you don’t need a synopsis: It’s the same story — just strangely simplified. Basically, Mr. Williams (Nighy) is our stand-in for Mr. Watanabe in Kurosawa’s story — a tight-lipped, cadaverous bureaucrat overseeing an office of younger men cut from the same dull and dusty cloth. As the film opens, we’re prepared by the grim-faced staff of the Office of Public Works to meet their apparently intimidating and difficult boss. Williams makes a grand entrance, sure enough, but then right away any sense of his severity seems to dissolve. He’s diagnosed with a terminal illness and, in no time at all, throws himself (as much as a slow, soft-spoken, elderly gentleman like himself can) into a series of awkward lunges toward enjoying his last days, almost as if he heard David Bowie’s “Cygnet Committee” and was invigorated by the song’s climactic refrain of “I want to live! I want to live!”

Before long, as always tends to happen in movies like this (including Groundhog Day, for example), Mr. Williams will realize that indulgence has its pleasures, but human kindness is the true path to joy. And all the while, the Public Works gang — stuffier than the circle of spies called The Circus in Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy, and all of them obvious variations on the Williams template — get lots of opportunities to take their turn at blinking in bewilderment as their famously morose superior officer starts acting up.

I mean… who could be offended by such a redemption arc? It’s a formula that will always work on at least some people in the audience. And I don't mean to say I didn't enjoy it — I did. Very much. Cast Bill Nighy as the lead in just about anything, and Anne and I will both be there for it. He’s one of our favorites. We savored our rare date night at the movies and we talked all the way home about the composition of our favorite shots in cinematographer Jamie D. Ramsay’s marvelous work. (There's one close-up of Nighy under an umbrella where he turns suddenly, and the suddenly flourish of light and shadow made me audibly gasp.) The screenplay — adapted by the great novelist Kazuo Ishiguro! — is full of warm, poignant human moments. The classical score, predominantly piano, sounds great in a theater, reminding me of how I swooned for Jonny Greenwood's score for Phantom Thread sitting in the same theater a few years ago. (But did they really need to reach for the familiar and reliably dramatic strains of "Variations on a Theme by Thomas Tallis," played in its entirety for the finale?! I mean, that's almost like cueing up Pachelbel's Canon. It seems... lazy.)

My apologies to director Oliver Hermanus, who obviously crafted this out of deep love for what many think to be Kurosawa’s crowning achievement. But I just did not feel particularly invested in Mr. Williams’ attempts to break out of his zombie-state the way I always feel invested in Mr. Watanabe's last days. Williams' transformation seems so abrupt here: One moment he's sitting sullenly in a dark room (as only Nighy can), as if posing for a variety of moody profile shots, and blinking in bewilderment (Nighy has always been very, very good at blinking); the next he's partying with the worldly Sutherland (Tom Burke being very Tom Burke and then disappearing too quickly); the next he's basking in the generous attention of a young woman (a softly glowing Aimee Lou Wood); and then he's suddenly waxing eloquently about his mistakes, and charging into this narrative's famous crescendo of human kindness. I sat there thinking, “I'm going to get back to the car before my two-hour parking limit is up after all!”

I feel like a horrible person suggesting that Living is anything less than a minor miracle. But the trailer made me excited to see an inventive variation on one of my favorite films, and hopeful that I would see Bill Nighy in his defining performance, one that might even win him an Oscar, which would seem right and good at this stage of his career.

Instead, the movie just felt like a longer version of the trailer, making no surprising deviations from its source material. And I found myself wanting to revisit Ikiru as soon as possible to get a better sense of why Kurosawa’s film is so much more profoundly satisfying, and why this one feels so slight.

Leveling up! Subscribe for free to Overstreet's new online journal.

So, you may have noticed that Looking Closer has been suffering some technical difficulties. (See details below.)

As others who know more about Wordpress than I do are striving to repair this site, I am spending my time constructively: Leveling up!

The ship of LookingCloser.org has become a little unwieldy over the years and thus vulnerable to attacks. It's time for me to launch some adjoining endeavors that will help carry my work forward on rough seas.

Step #1: I've launched a new Substack, where I can write more frequently and more spontaneously!

You can subscribe for free and get most of the goodness that I plan to post there for the foreseeable future.

You can also opt for a paid subscription where you will get even more of that goodness.

I've already posted an introduction, a bunch of songs from new 2023 albums I'm excited about, and a post about the Academy Awards. What's more, I'm posting my Favorite Recordings of 2022 and my Favorite Films of 2022 lists there before I post them here! What's more: I will make an announcement there soon that I'm pretty excited about.

So, subscribe for free to get my writing delivered to your email, or just follow the site regularly!

I'm eager for feedback: questions, comments, recommendations — and even constructive criticism from mature, respectful grown-ups!

Regarding the technical difficulties at Looking Closer: These disruptions have begun — coincidentally, I'm sure! — after threats from some highly insecure bros who took offense when I raised some questions about Top Gun: Maverick. Apparently, somebody launched an attack on this site — ill-advisedly, as the attack has done far more damage to my host server than to me.

And here's the irony: In doing this, they've only strengthened my case that any ideal of masculinity that glorifies lawbreaking recklessness and obnoxious arrogance leads men into behaving like dangerous juvenile delinquents. "How dare you raise a critical question about Maverick? How dare you suggest that Top Gun glorifies immaturity and violence? In response, we're going to behave immaturely, and with violence!"

(Sigh.) Boys, boys, boys.... Such behavior by bullies bothered me when I was in second grade, and now it just makes me shake my head and feel sorry for them.

But hey — their vandalism has inspired some new creativity in me, and I'm delighted that Give Me Some Light already has so many subscribers! I call this a "win."

Favorite Recordings of 2022: #36 – #21

Why 36?

Because I had worked hard on preparing a list of 30 for you to explore — and then, after the clock on 2022 ticked down to zero, I finally caught up with a few more records that I'd overlooked, and now I can't wait to share them with you.

Despite all of the claims from critics across music journalism about the "best" music of 2022, the fact remains that our experiences with music are highly influenced by the contexts in which we attend to it, by our individual histories, by our relationships and communities, by our susceptibility to marketing and fleeting trends, and by our curiosities and questions and concerns. So you won't find me joining the clamor of those presuming they know what is "best." This is just a personal expression of admiration and gratitude for those favorites that moved, impressed, and inspired me, the music that made me feel grateful to be alive.

For me, 2022 was a year of challenges and growth. I received extraordinary affirmations for my teaching from colleagues and students, and I am deeply grateful to the committee who reviewed my record of teaching over the last few years and gave me an encouraging report. I traveled and spoke at other schools about faith and art, and I met new friends and colleagues there. While I struggled to find the time and resources to write new fiction, I wrote a lot of essays on cinema and music, and my work was published for the first time at my favorite film-criticism website: Bright Wall Dark Room. Then, 2022 wrapped up with a huge surprise: a promising opportunity for my writing that I did not anticipate. (I'll share details about that soon!)

But 2022 was also a year of grieving. I am grieving the ongoing betrayal of my country by compulsive liars, fear-mongers, and manipulative anti-Christs. I am grieving with those who have suffered lasting damage from COVID (and lasting damage from the COVID-deniers, anti-vaxxers, and anti-maskers who accelerate the ongoing pandemic). I am grieving with those harmed by wolves in disguise among communities of faith. Most of all, I am grieving the way my own academic community of faith has been repeatedly betrayed, undermined, and harmed by the fear and prejudice of the anti-intellectuals at the controls of the school. While I have never felt more purposeful in my teaching and my writing, I also feel as if I'm doing so on a ship sabotaged by its own captains... and sinking. I am watching a vision that has inspired me for more than 30 years dismantled by the very people who have the power to help it flourish.

Music is one of the languages of God that sustains me. I am so grateful for the rivers of song that continue to flow into my heart, strengthening me to endure another season. Music brings me the beauty, the poetry, the wisdom I need to remember the Grand Scheme, in which God's kingdom of Unconditional Love and Embrace overcomes all prejudice, all fear, all corruption. My dreams will be realized. Grace will overcome legalism. Courage will overcome fear. The hateful and the fearful will make a small noise for a while, but their empty victories will be overwhelmed by the Big Music of love.

Music gives me the melody and the vocabulary for rejoicing in that hope.

And I found that in these records. I enjoyed more than a hundred albums this year and these are the ones I am going back to again and again.

36–35

Sault — Air

Sault — Aiir

Sault released six albums and an EP this year. How can that be legal?

Even more impressive, every release from this mysterious British collective — we know Inflo and Little Simz are heavily involved, and we know several more names as well, but there's a lot that's still secretive about them — was worth listening to repeatedly. And each record was distinct in style and substance.

These two were epic works of symphonic orchestral music with powerful choral performances, and even so they were strikingly different from one another:

Air is epic in scope and overwhelming in its intensity. Coming on like a hurricane, it resonates with conviction and purpose, weaving a rich and classical tapestry of voices and instrumentation celebrating Blackness against forces of cultural and historical erasure.

For some perspective from an admiring critic who knows what they're talking about, check Shy Thompson atPitchfork.Thompson writes,

... [A]s the group makes a sharp pivot to lush contemporary classical, they take the opportunity to remind us that even a style of music seen as traditionally European has been deeply influenced by Black innovators. “Luos Higher” makes plucked stringed instruments and chants its centerpiece, drawing influence from the music of the Luo people of Kenya for whom the track is named. The delicate string work of “Heart” conjures the specter of an Alice Coltrane spiritual journey, while the nearly 13-minute symphonic suite “Solar” calls back to the exuberance of Julius Eastman’s kinetic masterpiece Femenine with its twinkling pitched percussion. Every piece on AIR wears its heart on its sleeve, conveying an emotional urgency that makes the album feel like SAULT’s most personal body of work, despite being mostly wordless.

Me, I find Air too much to absorb in its entirety, but I come back again and again to bask its glory the way I might cautiously inch my way out onto a promontory over the Grand Canyon.

The follow-up, Aiir, is half as long and easier to absorb and enjoy in one sitting, playing rather like a score for a silent film or a program of compositions celebrating natural wonders. With the track titles "4am," "Hiding Moon," "Still Waters," "Gods Will," and "5am," they suggest that this might be a meditation on what it takes to hold on through the longest, darkest part of the night until the first touch of dawn kindles a fulfillment of hope.

With either of these achievements, I feel like the 7-year-old I once was, choosing a mystery record from my grandfather's collection of classical LPs, putting on my grandfather's headphones that were too large for me, and losing myself in a very, very Big Music that both intimidates and enchants me.

https://youtu.be/-5OzNTZystM

https://youtu.be/iV92fPoUFig

https://youtu.be/0ENYJyLrdBQ

https://youtu.be/T1lkBZ8_Q7w

34

Sault — 11

Sault — 11

The latest in Sault's albums with numerical titles is another eclectic playlist of neo-soul spirituals, pop, and hip-hop running on minimal bass beats and low-key grooves. It's like a multi-genre worship service driven by calls to "fear no one." As various authoritative sources of music criticism have been debating which record of the surprise five-album Sault surprise release is the best, Uncut is one of the publications that favors 11 as the finest:

12 is, marginally, the pick of the bunch, a mix of 11 pop miniatures, including the psychedelic A fro-pop of “Together”, the Brit-soul of “Higher”, the dreamy, quiet-storm R&B of “Fight For Love”, the slow-burning funk of “In The Air” and the funk-meets-ragga of “Glory”. Every track is a banger.

I may not agree that it's "the pick of the bunch" — you'll see which ones I prefer much nearer the top of this list — but I love it anyway. Here are the three tracks from 11 that are currently my favorites:

https://youtu.be/UNrlZiXjVGc

https://youtu.be/6ZQcvm50azM

https://youtu.be/65UT-rYhv6U

33 – 32

Maggie Rogers — Surrender

Madison Cunningham — Revealer

Here are two young women at the peak of their powers — or maybe that's not fair. Who know where they'll go from here? Whatever the case, both Madison Cunningham and Maggie Rogers got heavy rotation in my headphones this year, and I'll be tracking what they do closely from here on.

Rogers must be the biggest rock star to ever have earned a Master of Religion and Public Life degree from Harvard Divinity School. Is that evident in her hook heavy, arena-pop sound or lyrics? No. A review by at Yahoo describes the songs as “stories of anger and peace and self-salvation,” in which the singer finds “transcendence through sex" and "freedom through letting go.” But when Rogers' put her own words (for Apple Music) to the album's driving idea, it sounds like the heart of the Idles album Joy As an Act of Resistance that topped my list a couple of years ago: "... joy as a form of rebellion, as something that can be radical and contagious and connective and angry.It has the intimacy of an album recorded in her family's New York City garage (which it was) and also at Peter Gabriel's Real World Studios in England. I think that will make sense when you hear it.

It's Cunningham's album where I can hear the struggle of faith. And that's what faith is, right? A struggle? If it isn't, it isn't faith. Faith is a risk. It's the assurance of things hoped for, the conviction of things not seen. And I hear that in the opening track, as the singer speaks to an unnamed other who has been "all I've ever known," but whom she's not sure exists:

Will you take me as I am?

In perfect obedience to all these demands

I'm a child to the wonder but a victim of the change

When I see you again, will I know what to say?

I hear nothing, no rescue coming

Just church bells drawing out the dogs

I'm afraid that you were made by invention and odds are

I may never know

I can't help but wonder if Cunningham might not have been inspired by Sam Phillips, the once-Christian-music-pop-star turned poet of doubt and longing. After all, she's dancing in a blurred spin on the cover, just as Phillips did in her pivotal album The Turning.

In "Who Are You Now," she sings lyrics that match my own exasperation when I think of the double-speak of the evangelical culture in which I grew up:

Who are you now?

Who are you this time?

...

Whеn did war become sensiblе and love unfair?

But if I'm being honest, I play Revealer first and foremost for the inventive interplay of fuzzy guitars, complicated rhythms, and acoustic experimentation that keeps it feeling fresh, particularly in "Collider Particles."

https://youtu.be/iZjR6V6Adrk

https://youtu.be/dJqEOkmkeuM

https://youtu.be/0Da6AvsegGs

https://youtu.be/2BZ70WMjCMQ

31

Jack White — Entering Heaven Alive

Jack White — Entering Heaven Alive

If I'm honest about why I still listen to Jack White, I'll give the same answer I've always given: hooks and riffs. The guy just seems as divinely inspired as anyone in modern rock when it comes to cooking up a searing guitar line that you'll never get tired of hearing. His lyrics rarely intrigue me, and even more rarely move me, and his vocals have a certain Robert Plant-ish edge to them. But if it weren't for the guitars, I wouldn't show up. So I'm surprised that this release, arriving just a few months after the stranger and more experimental Fear of the Dawn, made a stronger impression on me than any previous Jack White work. I think it's the strong bones of the songwriting, the constantly surprising and richly layered sonic effects that set off fireworks within those songs, and the cinematic qualities of the storytelling (and which are explored in ambitious videos like the one attached here).

https://youtu.be/Jv6Fc04ragc

https://youtu.be/JF30GpW__vo

30

Metric — Formentera

Metric — Formentera

Metric was, for me, one of 2022's biggest and most exciting rock discoveries. As I listened to Formentera, I realized how much I've been missing those '90s-era huge rock sounds driven by gutsy, expressive female vocalists — like Belly's Tanya Donnelly or PJ Harvey. In 2021, Wolf Alice grabbed my attention and never let go, and their live show was exhilarating. This year, Just Mustard is on the scene and kicking me in the face. But now I've discovered that I don't need to look for brand new talents; maybe I just need to look for those I've been missing. Apparently, Metric's been pumping out bold rock albums since... 1998?! How have I missed them? Critics seem to agree that Formentera is bigger, bolder, more ambitious than anything they've ever done, but I'm loving it so much I'm compelled to work backward to find out what I've been missing. Here are three tracks worth sampling: I love the epic lament for our self-inflicted downward spirals of online despair called "Doomscroller"; I love the relentless momentum of "What Feels Like Eternity"; I love the hushed anticipation of "All Comes Crashing" that delivers payoff after payoff when those heavy Cure-like drums kick in for the chorus. Metric has a new fan, and I'd really love to see them live.

https://youtu.be/YjNytMN4QL0

https://youtu.be/_GesZGGvlNc

https://youtu.be/F0RQVKTZQpI

29

Patti Griffin — Tape: Home Recordings and Rarities

The deterioration of Patti Griffin's voice after her recent cancer treatments has been a tragic loss to American music. I saw her give an heroic performance at the Nowhere Else festival in October of 2021, boldly delivering a whole show of great songs, riding on the support of her enthusiastic and faithful fans. But it's hard to accept that the voice we loved so much for so long isn't coming back.

Thus, when I discovered this release at the very end of the year, it felt like a Christmas miracle: a modest collection of archival recordings that hold together remarkably well as an album. "Don't Mind" is another playful, high-energy highlight of her dynamic-duo collaborations with Robert Plant. "Sundown"

But my favorite track is "Night," which speaks of a deep intimacy with depression — or, worse, despair — in some astonishing lyrics:

Night, you come and sing the songs

Of birds that have no eyes

Of birds that never fly

Of birds that tell me lies

...

Night is watching from the tower

Turns on the electric fence

The night can make you disappear

Without a trace of evidence

Night is like judgement

Where nobody speaks on your behalf

You hear yourself calling out loud

And you hear the night laughing back...

https://youtu.be/Q-79s2WP_WA

https://youtu.be/aYQ0dBvs1Cs

28–27–26

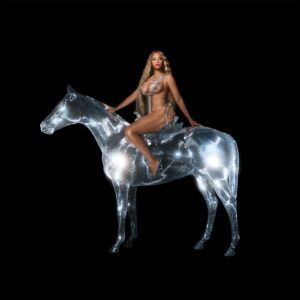

Beyoncé — Renaissance

Rosalía — Motomami

M.I.A. — Mata

I rarely feel so ill-equipped to write about music than when I write about artists like these — hyper-confident, hyper-talented divas of the dance floor, rising from experiences, cultures, and traditions quite foreign to me, and leading a vast host of devoted and adoring young female fans. And sometimes I'm tempted to keep my enthusiasm to myself for fear I'm trying to look like someone much younger than myself. But I genuinely enjoyed all three of these records repeatedly this year, not only because they challenge me to really listen and expand my horizons, but because their energy and creativity give me hope.

And if you have to go to work day after day in a "Christian nation" where misogynists, racists, and anti-christs still have fierce grip on the controls, I recommend driving in a car that pulses with the extravagant beats of these three records, from these three divas, who suffer the effects of cultural oppression far more directly than I ever do, and who invest their work with inspiration for those they hope will rise up and change the world. Their motivational zeal, audacious imaginations, hyper-colored sounds, and irrepressible joy are proof enough that God is alive and well within them. And their music was a life-giving adrenaline shot morning after morning for this 52-year-old white guy's weary heart.

https://youtu.be/jSAHnBS1SHA

https://youtu.be/5LugDbaqk8o

https://youtu.be/rzk20hkG6P8

https://youtu.be/yjki-9Pthh0

https://youtu.be/81j9gt1rXuk

https://youtu.be/aG5C32aATKc

https://youtu.be/WH95KAWS2-o

25

Kae Tempest — The Line Is a Curve

Kae Tempest — The Line Is a Curve

Mercury Prize-nominated Kae Tempest has become a regular on my annual lists, and much of that has to do with their impressively literary work — not just in rap, but in the poetry, the plays, and the novels they've written. So much hip-hop focuses on the performer's ego and sense of being disrespected, but Tempest's focus is on the work in a way that earns respect without being preoccupied with it. If you've been following their journey, you've noticed the name change, noticed the transition, and tracked the trouble through song after song about the quest for authenticity and wholeness. With blunt-force honesty in one hand and the power of love in the other, she's poised to knock the literal hell out of us. I'm reminded, as she performs, of the power of Jericho Brown's poetry recitations. And there's a moment in "Grace" at the end of this record that feels like an epiphany, a breaking out of the storm into open, blue skies.

For a full review by critics who know the genre better, read Emma Madden at Pitchfork or Timothy Monger at AllMusic.

https://youtu.be/S8gymPzmtZs

https://youtu.be/Tvz_fxrNZ9o

https://youtu.be/ay3R8dNmLZc

24

Kendrick Lamar — Mr. Morale and the Big Steppers

Kendrick Lamar — Mr. Morale and the Big Steppers

Kendrick Lamar is the most interesting rapper recording today, in my opinion — not only for his wisdom, his writing, and his vigorous engagement with questions of faith (which are inseparable from questions about social justice), but also for his sonic adventurousness. Both To Pimp a Butterfly and DAMN. have been records that challenged me, frustrated me, inspired me, and ultimately expanded my understanding of and love for my neighbors and my world. So I've been eagerly anticipating this one.

And, to Lamar's credit, it is not what I might have hoped for. I mean, I wouldn't know what to hope for from him, but I probably would not have jumped to vote for an album of such abrasive and discomforting material. That is, ironically, why I have to put it on this list: When you listen, you'll know that this is the album Lamar needed to make: He had to release the storms roiling in his head and heart, and they are messy storms, full of struggle, shame, insecurity, and vision. It's going to be an album I listen to rarely, but when I do it is going to demand my close attention, my patience, and a willingness to step outside of my comfort zone to ponder complicated personal matters: confusion, confessions, rants, rage.

Mr. Morale and the Big Steppers lacks the kind of highlight tracks I would usually share with others in hopes of inspiring their curiosity. "Crown" is currently my favorite because I do connect to that one, as someone who tends to sabotage his own peace of my mind by overcommitting to too many parties, expecting too much of myself in pleasing everyone. The mantra/chorus "I can't please everybody" is one I've been singing a lot lately.

I'll post a few tracks here that I have found most rewarding in the few times I have struggled through. Am I including this album because I feel that a more sophisticated critic would? No. I'm including it because I grow when I am challenged, and this is a strong challenge. I may not much enjoy it much, but I admire it, and I am learning from it. For that, I am grateful.

Here are some words from critics better equipped to write about the reigning king of hip-hop:

Jon Caramanica in The New York Times :

"Lamar, 34, is an astonishing technician, a keen observer of Black life, a proletarian superhero, an artist who reckons with moral weight in his work. But judging by “Mr. Morale,” which was released on Friday, he is also anguished, ravaged by his past and grappling with how to make tomorrow better, besieged by a collision of self-doubt and obstinacy. And fallible, too. ... The Lamar of Mr. Morale sounds lonely and tense, increasingly aware of the burdens placed upon him by his upbringing and potentially unsure about his capacities for overcoming them.

...

If To Pimp a Butterfly from 2015 was Lamar’s social polemical peak, and DAMN. from 2017 was his anxiety album — the product of realizing how his very private thoughts were becoming very public and scrutinized — then “Mr. Morale” is about retreating within and pondering your accountability to the person in the mirror, and to the handful of people you keep closest.

Stephen Kearse at Pitchfork:

Despite all its aggrieved poses and statements, the often astonishing rapping, the fastidious attention to detail, and its theme of self-affirmation, Mr. Morale & The Big Steppers ironically never settles on a portrait of Kendrick. Perhaps that slipperiness is the thrust of the album, which might be read as his answer to a question he asked a decade ago, before he was anointed as hip-hop’s conscience: “If I mentioned all my skeletons, would you jump in the seat?” That fear of being defined by trauma and shame resonates throughout, but Kendrick and his blemishes are so defined by negation—of white gazes, of Black Twitter, of weighty listener expectations—that by the time the record ends, Kendrick’s “me” is just as nebulous as the effigy he’s spent the album burning.

Tom Breihan at Stereogum:

On opening track “United In Grief,” Kendrick says he went and got himself a therapist, and it’s like: Yeah, no shit, buddy. If it’s anything, Mr. Morale & The Big Steppers is a therapy album. Kendrick spends the bulk of the record interrogating his own perceived failures. He talks about his “lust addiction,” about his “daddy issues,” about dealing with “writer’s block for two years.” Eckhart Tolle, a German spiritual-leader type who I’d never heard of before this morning, pops up multiple times. On “Savior,” Kendrick directly addresses the idea of his own importance, and he repeats over and over that he can’t be the leader that some people want him to be. He’s not even sure that he can be the man the he wants himself to be. It’s a necessary corrective.

...

Kendrick Lamar already won. He’s almost universally acknowledged as an all-time great rapper, an artist of the highest order. Mr. Morale & The Big Steppers is a fascinating, engrossing answer to the question of what a Kendrick Lamar album might be in 2022. It’s not even just one album; it’s two, even if I don’t totally understand how the two halves of the album are supposed to be different from one another. With this album, Kendrick makes it clear that he can’t and won’t be all things to all people. He’s not the voice of a generation. He doesn’t even have his own shit figured out, and he’s worried that he’s doing more harm than good in the world. He’s definitely not down to be a corporate avatar for social progress and racial reconciliation: “Capitalists posing as compassionates be offending me/ Yeah, suck my dick with authenticity.” An album like this could’ve been a long-delayed victory lap. Instead, it’s self-consciously knotty and clumsy and sometimes ugly. I don’t agree with all the ideas that the album presents, but I love how wild and ungainly it’s willing to be.

https://youtu.be/eL1L287YbkQ

https://youtu.be/Vo89NfFYKKI

https://youtu.be/0kS-MtxPr9I

23–22

Chagall Guevara — Halcyon Days

Midnight Oil — Resist

Dear Chagall Guevara, thank you. Thank you for making it happen. Steve Taylor had a tremendous formative influence on my understanding of faith and art in the late '80s, so when you jumped the barbed wire of the Christian music industry and released your first full album to those thrilling rave reviews, it was exhilarating. As one of your first fans in 1990, I bought the Pump Up the Volume soundtrack as soon as it was available just to have your song "Tale of the Twister." Your full album remains my favorite hard rock record of the '90s, and that explains why the band's breakup in '93 was so disappointing. No rock band I know have ever had lyrics quite like yours — fierce, literary, searing, funny. I hoped for your reunion until such a possibility seemed too far out of reach. So this return thirty years later made me more than a little nervous. Could you recover the energy? The voice? The vision? The answer, much to my relief, is yes. You sound like you're picking up right where you left off, and your wisdom about the troubles of 2022 shows that your vision is more necessary than ever. Thank you.

Dear Midnight Oil, please help me to tap into whatever serves as your power source. You have maintained a sense of focus, of energy, of excellence across four decades. And you are still raging with righteous rock-and-roll anger without allowing it to corrode your spirits. Thank you for all you have given us. I wish U2 was still capable of cooking up a song like "Nobody's Child" and then delivering it with the furious abandon of 18-year-olds.

https://youtu.be/-A8nyGFCty0

https://youtu.be/NNt9MuB6xRs

https://youtu.be/IGEKtaJiKjQ

https://youtu.be/lHg_iSv4lpg

21.

Florist — Florist

Florist — Florist

Reminding me of how Luluc's Passerby stole my heart a few year's back, Florist's quiet, complex, deliriously poetic reflection on birth, childhood, family, love, sex, loss, and death is truly epic. I love the lyrics, the exquisitely layered dreamscapes of sound, and the experimental instrumental interludes that give us time to meditate on what's just been sung. I wish more bands would give themselves the freedom to explore instrumental music. Not everything has to be a radio-ready hit. The reason I find Radiohead so much more interesting than U2 over the last 20 years has been Radiohead's consistent interest in music over pop formulas. I could listen to them play ten minute versions of any of their songs just to enjoy their experimentation and exploration. Florist has that curiosity, that patience, that interest in color and texture; the music is the thing — it isn't just there as a setting for the words.

The song "Red Bird Pt. 2 (Morning)" has made me toy with the idea of making a playlist full of songs that are built from the template of Leonard Cohen's "Suzanne." R.E.M.'s "Hope" would be there, and quite a few others as well.

https://youtu.be/pnzrmr5Y1a8

https://youtu.be/gRcnxdO9IC4

Favorite Recordings of 2022: Part One — Honorable Mentions

On December 24, as our home was aglow with Christmas music — Over the Rhine, Bruce Cockburn, Don Peris, Loreena McKennit, Louis Armstrong, Vince Guaraldi — and we only had one week left until 2023 began, I began writing my year-end posts.

Eleven days later, I'm still amending them, as I am still exploring and discovering 2022's wide, wild world of imagination — new releases for sound and for screen that impress and inspire me. And over the next few weeks, just as I have done for decades, I'll post my annual list of my top 30 (or so) favorite recordings of the year and my top 30 (or so) films of the year.

This is one way I celebrate and express my gratitude, even if I doubt that many of the artists will ever see what I write. This is also my favorite way of offering recommendations for others to discover treasure they might have missed. Your feedback is welcome. I wouldn't be publishing this if I wasn't persuaded to continue by the meaningful responses I receive from readers who value the discoveries they make here.

And, as usual, I'm having a terrible time narrowing down the list. There's just too much good music in so many genres. If an album captures my attention, if it makes me want to read all about the artist and the recording, if it makes me want to spend time with and interpret the lyrics, if it makes me want to play the album over and over again to be enchanted or challenged by the sound, well... it's going to be on these lists.

Since I'm still organizing my list of the top 30 favorites, I'll begin by publishing a list of albums that I want to include on that list — records I've enjoyed over and over again. Ask me tomorrow, or ask me in six months, and maybe I'll have changed my mind and found a place for them in my Top 30.

I listened to each of these "honorable mentions" several times this year — usually in the car on my commute, or on a road trip, or while I was grading papers or cleaning the kitchen. Some of them got me dancing while I organized my office. Some of them imparted wisdom, vision, and hope. Some of them gave me ways to name things I had not found words to describe. Again — I am grateful. If an artist or an album show up here, it's because I'm saying "Thank you."

"Bonus Materials" — Unexpected Archival Recordings from Rock Legends

David Bowie — Toy

This posthumously released "lost album" doesn't do much for me in its final form. But the two discs of alternate versions are jam-packed with surprises and treasures, like this gorgeous mix of my favorite song from the project: "Conversation Piece." Check out thorough and thoughtful reviews at The Guardian and ArtFuse.

https://youtu.be/kQfaGvObGM8

Bruce Cockburn — Rarities

A lively zigzag through rough takes touching on so many of Cockburn's modes and styles, featuring some early versions of songs that evolved considerably before they appeared in their final album versions. Here's some perspective at Blues Rock Review.

https://youtu.be/uBCTzRmykG4

Timeless Live Shows

Prince and the Revolution — Live

It's been a long time coming, but this ultimate concert from Prince and the Revolution finally got a proper audio release this year.

https://youtu.be/eNyMQZamzKE

Levon Helm / Mavis Staples — Carry Me Home

This may be my favorite Mavis Staples album, and the fact that these are all live takes in collaboration with the legendary Levon Helm... that makes this record so much richer and more rewarding.

https://youtu.be/7hvPwNo0R88

Summer of Soul (...Or, When the Revolution Could Not Be Televised): Original Motion Picture Soundtrack [Live]

The film came out in 2021, but the soundtrack album came out this year, and it stands alone as an essential double-live album.

https://youtu.be/HhMSZKIpWMk

The Rolling Stones — Live at the El Mocambo 1977

Peak performance double-live album from the Stones may be my favorite single package of their greatest hits. It's performed with such wild abandon.

https://youtu.be/bwHdC_tfVgY

Loreena McKennitt — Under A Winter's Moon (Live At Knox Church, Stratford, Ontario 2021)

Such great storytelling — by such great storytelling voices! — stitches McKennitt's performances together. I put it on as background music at Overstreet Headquarters as we were preparing for Christmas, and it very quickly became a Major Event for all of us. Yes, even our new fuzzy family member Special Agent Alonzo Mosely came close to the stereo, curled up in a ball, flipped over on his back, and fell into happy dreams. Great Christmas albums are always events worth celebrating because we know they'll become part of the fabric of our Christmases for years to come.

https://youtu.be/5kPkhbmRqSQ

Promising New Band

Just Mustard — Heart Under

If I had a "Most Promising New Band" award, I might give it to Just Mustard. There's a real Twin Peaks darkness to their sound, and some of the Wolf Alice energy that I'm a sucker for.

https://youtu.be/NAe0XFNJl9k

Exceptional Collections of Covers

Bruce Springsteen — Only the Strong Survive

First on my list of impressive collections of covers this year is Springsteen's soulful and surprising program of favorites. "Night Shift" is one of those songs I grew up with that I always enjoyed and didn't realize how deeply it was sinking into my DNA until it figured prominently in Claire Denis' masterpiece 35 Shots of Rum. The Boss sings it well. Sweet sounds coming down, indeed!

https://youtu.be/jEGdc9Rvr5M

Valerie June — Under Cover

My favorite covers record has the best title for a covers album. How has it never been claimed before? I've admired Valerie June for years, but this record got a *lot* of play on my car stereo this year. Every track is a brilliant choice, and every performance is surprising. Here's my personal favorite — although I really like her covers of John Lennon's "Imagine," Nick Cave's "Into My Arms," and Mazzy Star's "Fade Into You" as well.

https://youtu.be/YraJJiboEHs

Lucinda Williams — Funny How Time Slips Away: A Night of 60's Country Classics

Even though I don't like the placement of the apostrophe here, I'm so glad this album didn't slip past me. (It almost did.) I love this project, and I gotta say that almost all of these songs are new to me. Nothing like the blessing of the master to bring them to my attention.

https://youtu.be/vl8KL0tKLB4

Living Legends Doing What They Do Best

Brian Blade / Christian McBride / Brad Mehldau / Joshua Redman — LongGone

They're back, they're live, and they sound like they're having the time of their lives. The best kind of victory lap for a band is the kind that suggests they're joyfully invigorated by the knowledge that they still have unfulfilled potential. Blade, McBride, Mehldau, and Redman still have chemistry as great as any other four-man band going. When people say "I love jazz," they can mean all kinds of things. When I say "I love jazz," this is what I mean: the thrill of inspired improvisation within community, where it sounds like it might fly to pieces at any moment and then something happens that tells you they're so in tune with one another that they can make a beautiful hairpin turn.

https://youtu.be/YcHVXyjaBGY

Elvis Costello & the Impostors — The Boy Named If

With strong echoes of his Spike era, lyrics as literary and ambitious as any he's written (and sometimes a bit too cryptic because of that), Costello sounds as motivated as ever, singing with gusto that few his age could muster at a microphone.

https://youtu.be/KZU9b4NOQBQ

Bill Frisell — Four

And here's another quartet of combustible imagination: Bill Frisell with Greg Tardy, Gerald Clayton, and Jonathan Blake. Melodic, playful, and harmonic in a way that makes it difficult to understand if one of them is taking the lead or if each one of them is acting as the front man. A joyful ride in which you feel every player serving the music instead of stepping into a spotlight.

https://youtu.be/uV9mZh5RwiI

Pixies — Doggerel

https://youtu.be/10H7YGssFD4

Tears for Fears — The Tipping Point

I did not have Tears for Fears delivering an album to rival their best work on my 2022 Bingo card, but this one is so much better than just a visit from old friends. It feels like the kind of comeback album I wish Peter Gabriel would make — sincere, heartfelt grief and longing and hope, drawn from lived experience but applicable to the whole world.

https://youtu.be/Oc7whFL5UEk

Familiar Names, Unexpected Off-Road Adventures

The Mountain Goats — Bleed Out

Is this the first time they've shown up on one of my year-end lists? Perhaps. I'm warming to them, but very slowly — I started listening more than a decade ago. But the good humor of this record, the audacious concept (an album of songs built on action movie cliches and tropes), the playful lyrics, and the pedal-to-the-metal guitar rock of this one have won me over.

https://youtu.be/FesuReuhye0

Shearwater — The Great Awakening

They could have followed up Jet Plane and Oxbow, their greatest achievement yet, with another big '80s-flavored, U2-esque rock adventure. Instead, they chose to move inward to stranger, more haunting places. I haven't yet connected with this album in the same kind of personal way, and there are few moments I find as exhilarating as the sense of inspiration pulsing through the previous effort. But this is still an outstanding, enthralling record with so much on its mind and its heart.

https://youtu.be/jpKBcimnhFM

Professionals Maintaining High Standards

Pedro the Lion — Havasu

At Pitchfork, Ian Cohen calls it "the most minimal and insular Pedro the Lion album yet," and I agree with that. This isn't the album I'll recommend if I'm hoping to make somebody a fan of Bazan — it's so introspective and focused on its storytelling integrity that it is (rightly) less interested in rocking out, catchy choruses, or exhibitions of the band's particular chemistry and strengths. But Bazan and company achieve what they set out to do: they deliver another complex chapter in Bazan's serialized memoir of the cities in which he lived and how his experiences there shaped him. Cohen writes, "Whereas their 1998 debut It's Hard to Find a Friend took an accusatory tone towards those who would sacrifice their principles for social acceptance, on Phoenix highlight 'Quietest Friend' and the new album’s 'Own Valentine,' Bazan empathizes with his younger self as someone who used manipulation to fill a void of self-esteem."

https://youtu.be/ap7jsXS36OQ

Calexico — El Mirador

Differently than Pedro the Lion's album, El Mirador might be a perfect album for introducing others to Calexico, a band that fuses "the dusty sounds of the American Southwest with spaghetti western soundtracks, cool jazz, and a broad spectrum of Latin influences" (Mark Deming, AllMusic). As Heather Phares at AllMusic writes, El Mirador blazes with "praise for the people as well as the place that made them who they are, and they express that gratitude in songs ranging from the communal vocals of 'Liberada' to 'Constellation,' which traces the connections between people over winding guitars and flares of brass. The pandemic moved Calexico to celebrate all the good things in life, and this celebration includes the Latin influences on their music." When things were grey in Seattle this year, I found myself longing to drive open roads in the Southwest, and if I put on El Mirador I felt like I was halfway there.

https://youtu.be/EMeinq7I__w

Death Cab for Cutie — Asphalt Meadows

I didn't expect Death Cab had another substantial album in them at this point, and I really didn't expect it would be my favorite thing they've done since Transatlanticism. Just listen to the spiritual longing at the heart of this track:

https://youtu.be/yo3eHwbDwDs

Jack White — Fear of the Dawn

Jack White released two substantial albums this year. This one hits several memorable high points, particularly the opening track (linked). The other one will show up on my top 30 list, so watch for that soon.

https://youtu.be/q8IbI626k8Y

Arcade Fire — WE

I had very mixed feelings about this album from the day it arrived — glad to see them scaling back from bloated double-albums, still wishing the air of self-importance would burn away, glad to hear them recapturing some of the near-chaos that made them a singular act both on record and on stage, still wishing that they'd pull back from a sermonizing "We Are the Prophets of Our Age" presumption. But then came the scandal — the exposure of yet another white male of extravagant privilege as a sexual opportunist, and the disclaimers and excuses that then diminished what had been for many a sort of ideal marriage-in-the-rock-spotlight. But I can't let behind-the-scenes shenanigans interfere with my assessment of the art itself. And, as far as that goes, here's a record that delivers solid examples of what has made Arcade Fire distinctive and meaningful, even if it doesn't reveal any notable innovations. And they get extra credit for bringing the voice of Peter Gabriel back to my headphones.

https://youtu.be/dXGUMVoOPlk

The New Royalty

Florence + the Machine — Dance Fever

I've admired this band for a while, but I can't say I've played any of their albums repeatedly over the course of a year with confidence that I will continue to revisit them. This one feels like it has lasting power, and there's a joy in it that I haven't associated with the band before.

https://youtu.be/nUUhHTx1KYY