The Balcony Movie (2022)

[This review was originally published at Give Me Some Light on April 15, 2023.]

What a joy I’ve just discovered. And you can too.

At first, I thought that Pawel Łoziński’s new documentary The Balcony Movie was a pandemic project. And the farther I got into the film the more I wished I could turn back the clock and be more creative with those first two years of COVID isolation. Why not just set up a camera and a microphone somewhere and make something of what happens right in front of you?

All this Polish documentarian did, after all, was set up a camera and a microphone on the balcony of his second-story apartment and interrupt passersby with questions about their circumstances, their dreams, their fears, and their takes on the meaning of life. And what he captured may seem haphazard at first, but it grows into a sort of improvisational poetry as various pedestrians respond to his casual questioning by ignoring him, taking offense, begrudgingly agreeing to play along, giving him more than he probably wanted, immediately exposing their hearts’ open wounds, or challenging him with counter-questions.

Increasingly curious, I started reading and learned right away that this project began in 2018 before the tsunami of COVID required lockdowns around the world. I’m not familiar with Łoziński’s earlier work, nor have I seen anything but his apparently acclaimed filmmaking father Marcel Łoziński, but somehow this fact makes me doubly curious about these filmmakers. If they have these creative instincts without having to resort to them out of necessity, what other kinds of provocative pictures might they have made?

It seems like such an ordinary stoop on which a filmmaker might set up shop, but what transpires is remarkable. I kept thinking about Wim Wenders’s watchful angels over Berlin in Wings of Desire. (I know, I know — I say that a lot.) But think about it: Here, we can hover over unsuspecting Warsaw citizens and, if we’re lucky, catch them in candid confessions or unguarded flashes of temper or humor. We see representatives of every living generation; men and women in love; women grieving lost husbands or raging about their affairs; men struggling with being thrown out of their own marriages, and one grieving the loss of a male partner that he’d had to pretend was his brother; alcoholics grieving their addiction; ex-cons grieving their mistakes; dog walkers; and members of Łoziński’s own family.

At Filmmaker, Łoziński says,

I was always interested in what the passersby under my balcony have in their heads and hearts. Sometimes I sat there, privately without a camera, and overheard what they were talking about. The film came from simple curiosity: Who are they? Where they are going and what is the meaning of their lives? It was an experiment for me and for them. I asked myself, Is there a chance to meet an entire cross-section of people by putting the camera in a fixed place? I was trying to change the rules of the normal documentary game – this time it’s not me following the people with my camera around the world, but me waiting for them until they enter my frame.

The authenticity, the inimitable qualities of these particular human beings — the fact that they are so compelling, and that the film becomes so absorbing, is something of a lesson: We could be out there, on our own porches, in our own coffee shops, walking our own sidewalks, and, if we learn to look through lenses of possibility and generosity, we might find friends in neighbors from here and faraway. Just yesterday, working on another writing project, I was trying to remember the actual, literal neighbors that I had when I was a child. I found them all so mysterious, and imagined so many stories. This made me wish I’d been braver in meeting them. I should pay attention to that. I have actual, literal neighbors now with whom I’ve never even made eye contact.

Is The Balcony movie great cinema? That’s a more complicated question. Łoziński isn’t just some guy with a camera. He worked as an assistant for my favorite director of all time: Krzysztof Kieslowski. He knows things. And he does some remarkable things here in editing, in balancing this film between seasons, in selecting from his most rewarding interactions so that there are some threads that weave these seemingly arbitrary moments into a meaningful tapestry. I doubt that The Balcony Movie will ever become a staple of film-studies syllabuses, but it belongs in any expansive survey of documentaries as an example of what can be possible when a filmmaker is open to playfulness and improvisation. We end up with a document of a time and a place that nobody else could reproduce if they tried. The people of 2018–19 Warsaw, Poland are a whole lot more real to me now, here, in Shoreline, Washington 2023, than they might have been otherwise.

And I should make a record here of something significant: I don’t think I can recall a moment in all of my moviegoing history in which I was moved to tears faster by a character or a documentary subject than I was by one of Łoziński’s unexpected visitors. I won’t say the person’s name — I want you to discover her for yourself. But our host is good-humoredly looking for “a hero” for his film. And, against heavy odds, he finds one I will never forget.

My thanks to Ken Priebe for persisting in recommending that I seize the opportunity to watch this on MUBI — a streaming service so extravagant with essential viewing these days that I just can’t keep up. Subscribe, even if only for a month, so you can see this and several other recent wonders, like What Do We See When We Look at the Sky?, my #3 favorite film of 2022.

How to Blow Up a Pipeline (2023)

[This review was originally published at Give Me Some Light on April 10, 2023, while this film was still in theaters.]

I recently showed a class full of undergraduates the Coen Brothers’ 1988 comedy Raising Arizona. You probably know the film, and perhaps you remember this moment:

Furniture salesman Nathan Arizona (Trey Wilson) has offered a cash reward for the rescue of his kidnapped infant son Nathan Junior, and an opportunistic bounty hunter has blown like a tumbleweed into his office. This massive, muscle-bound, tattooed motorcyclist is Leonard Smalls — a.k.a. “The Lone Biker of the Apocalypse.” And Smalls isn't here to take the offer: He’s here to bargain.

Irked, Arizona replies that Smalls should take his deal or get out. But Smalls isn’t finished. He says he’s only asking for a “fair price” — one that “the market will bear.” He reveals that he is, himself, a survivor of a black market for babies, and then adds, “There are people — and, mind you, I know ’em — that’ll pay a lot more than $25,000 for a healthy baby. … I’ll get the boy regardless. And if you don’t pay, the market will.”

Smalls has come right out and said what so many other businesses conceal behind deceptive rhetoric: He would find a stolen baby and, instead of returning him to his grieving parents, he would sell the baby on the black market himself. And make a fortune. And why not, in a country that justifies so much harmful activity in the name of “the pursuit of [personal] happiness”?

Students, to their credit, were repulsed by this heartless, dollar-driven monster. Surely we can all agree that this is, as Nathan Arizona himself puts it, “an evil man.” He is showing us the dark side of capitalism, the consequences that can come from prioritizing profit above all else. “It’s just business,” some might say. But at what cost?

So here’s a question:

If you think conscience demands that we stop human traffickers, how far are you willing to go to stop them? If weapons prove necessary for intervention and the rescue of vulnerable innocents from fortune-hungry opportunists, will you support that violence as justified?

Now, put yourself in the shoes of the young idealists who join forces in the film How to Blow Up a Pipeline.

The film, directed by Daniel Goldhaber, is based on a non-fiction book of the same title by climate change activist Andreas Malm. The book is a manifesto, really, praised by The Los Angeles Review of Books as “[o]ne of the most important things written about the climate crisis” and a “profoundly necessary book.” The film takes Malm’s propositions and imagines a narrative about what a real-world rebellion against heartless capitalism might look like.

The team of would-be Avengers who plot a rebellion in How to Blow Up a Pipeline don’t inspire much confidence. Young Xochi (Ariela Barer) might come closest to qualifying as the Brains of this outfit. She’s already posting mission statements on the windows of luxury cars and slashing their tires. She’s angry. When she buried her mother, who died in a heat wave, Xochi could look back over her shoulder and see evidence of the cause: plumes of smoke rising from a factory. But the Brawn is certainly Dwayne (Jake Weary), who is losing all patience with oil companies as they force their way onto his family property to chart the course of a pipeline.

But a plan like this has a lot of moving pieces, and so they need a lot of help. Xochi brings her college friends Shawn (Marcus Scriber) and Theo (Sasha Lane) on board. (If you'd told me that this takes place in the AHCU — the American Honey Cinematic Universe — and Sasha Lane is still playing the same character from that Andrea Arnold film, I might have believed you.) Shawn shares Xochi’s strong convictions, but for Theo it’s even more personal: she’s angry about the chemical causes of the cancer that is killing her. (In a world designed to favor big business over human decency, how’s a young woman like Theo to afford healthcare?) And then there’s Alisha (Jayme Lawson), who signs on reluctantly for Theo’s sake, mostly out of loving loyalty for her dying girlfriend.

Then there are Logan (Lukas Gage) and Rowan (Kristine Froseth) — lovers who look likely to miss their cues in carrying out the plan, probably because they’re too horny or too stoned. If you’re placing bets early on what’s likely to go wrong, you’ll probably pick on them.

But who can blame this anxious crew for doing their best to make a difference while the rest of the world amuses itself to death? They want a future — a future for themselves and for all who come after them. They believe that the future of Planet Earth has been taken hostage, that it’s being sold to the highest bidder. They see oil companies accelerating even though the oil business is destroying the planet’s climate and propelling Planet Earth headlong into a crisis that humankind cannot survive.

Just as you and I might decide that force is necessary to rescue stolen babies from armed human traffickers, so they have decided that it’s time to blow stuff up to try and save the planet those babies depend on.

They see clearly that it would be mad to do nothing. And, as my students saw it in Leonard Smalls, they see not merely ignorance at work but a sort of demonic villainy. Isn’t violence against a mad murderer an act of self defense? Isn’t their desire to strike at these companies, to hit them where it hurts, reasonable?

If no amount of negotiation is making any difference, and if the oil companies have strapped a ticking time bomb to the planet, what harm is there is strapping a ticking time bomb to their oil pipelines? Why not try to blow up their unethical operations before they blow up an inhabitable earth?

Ah, but this band of heroes are acting in violation of laws — laws set up to protect businesses and business owners at the expense of, well, everyone else. Thus, as they conspire to try to save humankind, they are sure to be branded “terrorists.”

“If the American empire is calling us terrorists,” says Michael, “then we're doing something right.”

Michael, perhaps the most essential member of the team, is a young Native American who feels the weight of the injustices suffered by his people. He’s been investing his rage in desperate, devil-may-care activism: He studies and makes videos about the art of low-budget bomb-making. And if that isn’t enough to get his name on FBI watch lists, he also posts videos of his own violent confrontations with workers on North Dakota oil rigs. Played with simmering fury by Forrest Goodluck, Michael is the character who occasionally makes me feel that I’m watching a documentary instead of a thriller, even though his fierce eyes and his storm-tossed hair make him look like a mythic hero. He hurtles forward headlong, impatient, so that we believe he will try to pull off this mission all by himself if he doubts, even for a moment, the dedication of his co-conspirators. (Matt Zoller Seitz at RogerEbert.com aptly compares Goodluck’s screen presence to that of Michael Shannon, “an actor who can communicate that a character's mind is racing in a dozen directions even when he's handling whatever's right in front of him.”)

These characters, their plight, and their plan are all more than enough to make How to Blow Up a Pipeline an exciting ordeal of white-knuckle suspense and intellectual challenges. We’re invested. We want to see them succeed in shaking up the systems that have set humanity on a trajectory toward self-inflicted extinction. But do we want them to do so with violence, and with violence that is likely to get one or more of them killed? I rarely feel as conflicted watching heroes fight injustice as I feel watching this rebellion against the empire. But that’s because most movies make rebellions look too easy, too simplistic, too clean. The Good Guys of Star Wars who won my admiration in childhood now seem dangerously and deceptively simplistic, and so my generation’s storytellers, expanding on the Star Wars legacy, feel compelled to address more complicated ethical questions in necessarily messier sequels like Rogue One and The Last Jedi and in tangential series like Andor.

Unfortunately, How to Blow Up a Pipeline ends up feeling like it might not be grownup enough for its subject matter. I’m not talking about how it engages us with difficult questions; I’m talking about the artistry of its storytelling. It’s so difficult to pull off a movie like this without succumbing to the temptation to preach. The screenwriters — director Jordan Sjol and actress Ariela Barer — invest so much inspiration and energy into revealing the characters’ backstories and their suspenseful collaboration in setting up the explosives that the lack of forethought about what comes next becomes, in the final moments, painfully evident. What runs brilliantly for 90 minutes as an effective and thought-provoking adrenaline rush (as well as an X-ray and diagnosis of the rising anxiety prevalent in almost all of those 20-something and younger) stumbles at the finish line.

I find a similar sentiment in the Letterboxd post from Josh Larsen of Filmspotting: “How to Blow Up a Pipeline eventually sets aside the ethical debates its characters occasionally gesture toward to become its own political act, which feels somewhat at odds with the suspense trappings.”

Similarly, Michael Asmus at Letterboxd writes that

[A] call to arms feels lacking without an adjoined call to hope. Instead of letting the events play out and leave us to walk away weighing the costs, it confirms it's actions as good, and wants us to agree. There's some consequence, but no imagination for what's next. I hesitate to call it propaganda by any stretch, as there's artful moments which are surprising and affecting. But instead I left a bit let down….

Letterboxd’s own Mitchell Beaupre also acknowledges the film’s last-minute stumble: “There’s something anticlimactic about how the film concludes. Not that I’d want anything different to happen necessarily, but maybe certain reveals and tying up of all the threads was a little too abrupt and/or a little too clean.”

Indeed. After an hour and 40 minutes of excitement, it’s unfortunate that the film runs two misguided minutes further.

But I agree with all that Beaupre admires about it, including its spiritual connection to another recent film about this present darkness:

Not sure I’ve seen a film dig so effectively into the question of what we can do to try and make some kind of difference when at this point all hope seems so truly lost. First Reformed is the only one that really comes to mind and they’d pair well in that way, but while Schrader’s film takes the existential approach, How to Blow Up a Pipeline is dirty, on the ground, focusing on people who are really trying to do something, anything with what little time we have left to actualize change.

So, while I highly recommend this film as one of 2023’s most impressive, I also think it’s imperative that we follow it with rigorous conversations, exercising conviction and conscience. Is a violent rebellion against a wicked empire the only way forward? Is a refusal to blow up pipelines a sign that we have given up, and that we’re willing to enable the enemy?

I turn to J.R.R. Tolkien, who survived what was arguably World War One’s most horrific battle. He believed in the sovereignty of God as I do. And in The Lord of the Rings he does not condemn armies that march out in force against a world-destroying warlord. Indeed — he makes the focus of the mission an act of violence against the enemy’s most destructive tool: He has heroes risk their lives to destroy the Ring of Power. But Tolkien also acknowledges that no one really wins at war. His narrative is about how his most innocent and virtuous hero is corrupted by evil on the very path to blow it all up. This is why the saga seems haunted, burdened, fashioned as much to be a lament over the terrible choices available to us in resisting the Enemy. He wrote in a letter in 1956: “… [O]ne must face the fact: the power of Evil in the world is not finally resistible by incarnate creatures, however 'good' ….”

But then he added another clause — one in which abides all of his hopes for salvation: “… and the Writer of the Story is not one of us.”

Indeed, I must find my ultimate hope and comfort in the grand design of grace. We may destroy the world God gave us. And we may do more harm than good in striving to rid the world of its cancers and trying to strengthen the things that remain. But even if Planet Earth becomes uninhabitable, there is a more expansive story — one in which even death is defeated. We may have to turn to fantasy stories and fairy tales to get a taste of it, since we cannot realize it here and now. But there are reasons such stories carry the ring of truth. As evil empires devour themselves in their madness, there is an as-yet-to-be-revealed resurrection on the way, one we cannot yet imagine because its only precedent is what we’re celebrating here, today, as I write this on an Easter Sunday.

So, while I stop short of a whole-hearted, clear-conscience endorsement of this movie’s conspiracy itself, I cannot condemn the rebellion — or these beautiful rebels. The destruction they unleash is respectful of human life, not murderous. Their cause is just, their arguments compelling, their methods meaningful. In their heartbreak and desperation, I hear the poetry of David Bowie:

And these children that you spit on

As they try to change their worlds

Are immune to your consultations

They're quite aware of what they're going through...

Return to Seoul (2023)

[An earlier draft of this post was published at Give Me Some Light on March 29, 2023.]

I hate it when this happens.

The circumstances of my first viewing of Return to Seoul remind me of the situation in 2022 when I finally saw Joachim Trier’s The Worst Person in the World.

The Worst Person in the World was one of those movies that ended up on many critics’ top ten lists for the year 2021, but it didn’t get a wide release in the United States until the following calendar year. So, if you lived in New York or L.A., or you had the resources and the luxury to attend film festivals in exotic locations, you got to see it and celebrate it early. But if you’re like me — just an ordinary person living in small-town mainstream America like, oh, Seattle — then you didn’t get to see The Worst Person until 2022 after the privileged had already moved on from the party.

Maybe, in my snarling, I’m sounding like “the worst film critic in the world” right now. But, in the opinion of this movie-loving curmudgeon, a movie belongs to the year in which we, “the general public,” can share the experience. And there’s no risk that the filmmaker is still making changes. (Film festival releases are sometimes revised by filmmakers after the first reviews are published and before a wide release.) It’s the version that most cinephiles around the world will see, will talk about, will buy copies of.

Thus, The Worst Person ended up on my Favorite Films of 2022 list, inspiring several cinephiles to lecture me on the dates of its first screening. Yes. Thank you. I know. But I didn’t have any possibility of seeing it until February, so I'll categorize it in the year that the world could enjoy it instead of in a way that prioritizes competition and privileged access.

I’ve gone on that tangent just to say this:

I’m experiencing something like déjà vu with director Davy Chou’s Return to Seoul.

This one ended up on the 2022 top ten lists of those lucky enough to chase it down before its commercial wide release. To them, it’s a thing of the past while it’s only now opening for us commoners in late February and early March. And you can bet you'll see it on my list of 2023 favorites as 2024 begins.

Good news: You can rent it right now for less than the price of a theater ticket, and watch it in the comfort of your own home on a variety of streaming platforms.

Return to Seoul has a thrilling opening act…

…which is one of many aspects of the film that I refuse to spoil for you. (Proceed with caution if you read about it elsewhere: I’ve seen many film critics detailing many — sometimes most — of the film’s biggest surprises. I went in knowing almost nothing about it, and my ignorance made possible my bliss: I was consistently surprised in ways both delightful and dismaying.

The first act introduces us to Frédérique (Park Ji-min), a French tourist in South Korea who introduces herself as “Freddie.” She seems agitated, and we quickly learn that this is because her French upbringing as an adoptee has made her both curious about, and wary of, details about her Seoul-based family of origin. A fish finding herself out of water — or at least in a foreign fishbowl — Freddie makes quite a splash. If she were a character in Rian Johnson’s Glass Onion, she would be part of the gang of “Disruptors.” Like Renate Reinsve’s Julie in The Worst Person in the World, Freddie’s prone to making impulsive and risky choices. The spotlighted party girls in both films all but dare us to follow them on their zigzagging paths, living in denial of certain responsibilities until their needs for some kind of meaningful commitment overcome their reckless energy and draw them into relationships that they will begrudgingly accept… to a point. (And, it’s worth noting, both of these charismatic antiheroes have to navigate complicated emotional predicaments that occur while they’re pants-down and urinating in an unfamiliar bathroom.)

In the opening act of Return to Seoul, this mischievous traveler goes to dinner with new friends and, seemingly bored by their oh-so-Korean politeness and formality, and amused by their confusion over her very un-Korean demeanor, she decides to shake things up. What happens next is bound to make viewers uncomfortable in the best way. I was reminded of an obscure and distinctive movie — Werckmeister Harmonies — in which a wanderer transforms a bar into a human representation of solar system, with sullen drunkards drawn to their feet into a kind of dizzying dance. That’s a flashback I would never have anticipated!

From that point on, I was ready for anything — and that’s good, because the movie kept challenging me with unexpected developments. Just when you think you know what “kind of movie” this is, it morphs into something new.

If there’s anything predictable about the narrative arc, it’s that the gravitational pull of Freddie’s mysterious origins will prove difficult to resist. Soon she’s investigating questions about where she came from, and to whom she was actually born. I’ll leave it at that. Suffice it to say that there will be drama, there will be tears, there will be hard drinking and drugs, and there will even be tense exchanges with weapons dealers. (Yeah, buckle up.)

And yes, Park Ji-min is as good as you've heard.

It’s hard to believe that this is her first movie role; she commands our attention with an energy that reminds me not only of The Worst Person’s Reinsve but also of a young Juliette Binoche (think The Lovers on the Bridge).

But I’ll go see it again for more than Park Ji-Min. The rich and erotic colors (which made me wonder when we’ll see something new from Wong Kar-Wai), the thrillingly inventive composition, and the bold and sometimes disorienting editing are also enthralling, bumping the name Davy Chou up my list of directors whose next film can't come soon enough for me (and whose previous features I now need to track down). I don't think narrative leaps have jarred me as severely as this since the Dardenne brothers gobsmacked audiences with a sudden catapult forward in time late in their thriller Lorna's Silence. If you step out of the theater at the wrong moment, you might come back and find yourself wondering if you’ve stepped into a different movie with the same lead actress playing an altogether different character. Typically, an audacious move like this puts me off — I have to have a strong sense that such antics are purposeful. Here, there’s method in Chou’s madness: These jumps force us to reckon with Freddie’s rapidly shape-shifting self, provoking Vox critic Alissa Wilkinson to write about how this film might inspire “memories of the selves we used to be and the ones we might yet become.”

My favorite films are those in which I can sense the filmmakers’ excitement at the possibilities that they are discovering.

That’s true here — it’s as if the storytellers are inspired by the gambles their own protagonist is taking. Like Freddie, they seem to be “sight reading” their way forward. Sight reading is the term that Freddie gives to her way of life — an improvisational style that can stir up spectacular scenarios, but can also send her down paths that harm her and cost her. We may not think it wise, this way of throwing oneself into performing a piece of music when you don’t know where it will lead you or if you have the skills or the soul to see it through. But the way Frédérique sight-reads makes her a compelling agent of chaos who leads us to reflect on the tension between two kinds of freedom: the freedom we need to exercise in order to discover our true selves, and the freedom we may need to surrender in order to know the richer and more resilient rewards of love.

Now that I have seen the film, I find myself wanting to read a lot about it — particularly because I suspect that there is a lot of political commentary going on in the arc of "Frédérique's Adventures in South Korea." But I'm also interested to see if anyone is writing about how many scenes focus on Freddie relying on a translator, and how often that translator is making rather alarming choices in what they choose to translate and what they choose to ignore. (I haven't seen a film play with that tension so much since Sissako's Timbuktu.)

Having said all of that, while other critics are making much of a prominent dance scene, I found myself thinking that this might be one arthouse film too many that features troubled protagonists throwing themselves into frenetic exhibitionism on the dance floor. Freddie's scene is great (and quite a contrast to Jong-seo Jun's dance in Lee Chang-dong's South Korean psychodrama Burning), but the trend began and peaked with Claire Denis' Beau Travail, and I’ll be surprised if anyone can find a meaningful way to top that.

[Return to Seoul is currently playing in various arthouse theaters around the country. I expect we’ll find it streaming somewhere soon.]

All the Beauty and the Bloodshed (2023)

[This review was published on March 22, 2023, at Give Me Some Light.]

As I drive into Seattle sunshine on my way to work, I am listening to prayers sung with passion and longing, and I am haunted by the darkness I explored last night watching Laura Poitras's documentary All the Beauty and the Bloodshed.

...

As the photographer, activist, and opioid crisis survivor Nan Goldin guides me, like Virgil guiding Dante, through this labyrinth of souls suffering and dying in the trouble and torments of the ‘70s and ‘80s — the opioid crisis, AIDS, the wealth-hoarding of billionaires, the abandonment of the poor — it is a little like descending into L'Inferno.

But there’s one fundamental difference: Goldin’s slideshows that spotlight neighborhoods of artists, addicts, and sex workers are not a voyeuristic horror show of souls suffering the judgment of God. These are the faces and voices of the abandoned children of God: populations suffering the judgment of "a Christian nation" that fears and hates them and is doing all it can to punish them here and now for being different, for being imaginative, for being uncategorized. And many are children who were resented, judged, and abandoned by irresponsible parents. And thus, they’ve been denied the simplest shows of decency — like health care.

This is a tour of decades I lived through as a child, but one that reveals the people that I was carefully and methodically prevented from seeing, asking questions about, or knowing as my neighbors.

When I was growing up in the '70s and '80s, my church community taught me to "have nothing to do with the unfruitful deeds of darkness." And then they explained that "the unfruitful deeds of darkness" were pretty much anything related to sexuality (outside of heterosexual marriage), smoking, alcohol, other drugs, rock and roll (and, by association, blackness), and anything that suggested a blurring of their starkly defined "standards" of masculinity, femininity, marriage, a Divinely Mandated Patriarchy. Anywhere I might glimpse a strip club, or broken beer bottles, or a junkie in an alley, or a man wearing a dress, or a woman wearing a man’s suit — this, my church culture taught me, was where the devil lived, where "the lost" ended up. My community joined the conservative program to legislate, legislate, legislate until anyone who made them uncomfortable or strayed from their strict codes of behavior were erased from our cultural context; exiled into hunger, disease, addiction, and — yes — slaughter. The consequences we inflicted upon them were understood as God's judgment. "God’s wrath," they said, quoting Ephesians 5, "comes on those who are disobedient." And they pointed to AIDS as the proof.

But the very Jesus we preached, and whose name we lifted up in such searing diatribes, teaches and acts in quite the opposite way. He teaches love, embrace, inclusion, and even recognizing that God is busily at work in such communities. When Jesus' followers ask him about sickness as a judgment for sin, Jesus brushes that idea off. No, sickness is not a sign of divine punishment on an individual's behavior. In fact, sickness is a call for us to love mercy and be ready to discover what God is ready to do in an occasion of sickness. Where is God nowhere to be found? According to Jesus, God is nowhere to be found in the moralistic condemnations dealt out by the self-righteous religious elite.

I eventually learned that there was more to that scripture: "Have nothing to do with the unfruitful deeds of darkness — but instead, even expose them.." This was not a call to erase, ignore, and deny the things that made us uncomfortable. This was a call to bring everything into the light and observe it with the eyes of love, an act that would redeem and transform.

And what are the unfruitful deeds of darkness?

Well, we know what they are not: “The fruit of the Spirit is love, joy, peace, patience, kindness, generosity, faithfulness, gentleness, and self-control. There is no law against such things.”

When I look at the people in Nan Goldin’s photographs, I see many of the behaviors that the Scriptures highlight as evidence of sin: drunkenness, sexual recklessness, and more. But I see those things as the extremes to which these people go in despair for having been denied the love they need. Oh, you’ll find plenty of the same drunkenness, sexual recklessness, and drugs behind the closed doors of the very people who vote for policies that punish the poor. And you’ll also find the resources and power to change things there, the good things that they deny to their neighbors in need.

Greed. Condemnation. Arrogance. Lies. All of the strategies and motivations being used to push all of these imaginative orphans, all of these abandoned children of God, all of these "Others," into misery and torment. These are the things that Nan Goldin is trying to bring into the light so that we have no choice but to witness — and bear witness to — the Truth.

"Exposing" evil is a messy business. But it is a calling upon artists and followers of Jesus. And Goldin is an exemplar of such work.

Have nothing to do with selfishness and arrogance. Instead, expose it. Bring it into the light so we can see it. For in such exposure, any conscience that has any life left in it will be provoked, kindled, and awakened for the purpose of action.

Hatred is a cancer. And cancer is not to be ignored or denied. It is to be studied and brought into the light — lovingly, the way surgeons do as they strive to save their patients. Nan Goldin is an artist. She is a surgeon who has experience with various cancers, including the cancer of the opioid crisis that was cultivated within communities of poverty by the self-righteous rich and the arrogant religious elite. Her photography and her protests are her art. This is her act of bringing everything into the light. This is her Book of Lamentations.

As I drive south on Highway 99 this morning, the sex workers lined up on the sidewalks on both sides of this central Seattle corridor, I know that this is exactly where I would find Jesus — not busily judging and preaching piously at the population, but enjoying their company, embracing them, assuring them that they are worthy of love. I am on my way to work, at an institution of "Christian education." This institution recently published a new list of priorities for its leadership, and on that list the exclusion of all queer children of God from teaching there was ranked as a higher priority than prayer.

I invest my time and energy there in acts of resistance, determined to give the diverse population of students a different representation of the Gospel: a sign of welcome and embrace and affirmation, and a curiosity about what God is doing and can do among them, rather than a posture of finger-pointing damnation and arms-folded rejection. It wasn’t that long ago that I was still brainwashed by the Culture of Condemnation, and I am trying, in my embarrassment and shame and repentance of that life, to make some small difference.

I am thinking of Nan Goldin, taking inspiration from her, and hoping that I will be found, in the eyes of God, to have a heart more like hers than like those that legislate hatred, fear, and rejection.

On my car stereo, Bono is singing Psalm 40 — giving voice to persecuted, the downcast, reminding us of that boy of many colors who was thrown by his brothers into the pit:

I waited patiently for the Lord

He inclined and heard my cry

He lifted me out of the pit, out of the miry clay

And I will sing, sing a new song....

And then the chorus: "How long... to sing this song?"

How long must we sing Nan Goldin’s lament, indeed?

Overstreet Archives: Jonah: A VeggieTales Movie (2002)

In my course on page-to-screen adaptations, a student has proposed a paper on the adaptation of the Biblical account of Jonah and Big Idea's Jonah: A VeggieTales Movie.

Upon reading the proposal, I thought, "Wow... I remember writing about that more than 20 years ago. What did I say about it?" I checked Christianity Today and found only a few comments I made in an installment of my long-running Film Forum columns. Then I checked here at Looking Closer and... nope. Couldn't find a trace of it! And yet, Rotten Tomatoes actually has a record of a review, and says it's published at Looking Closer.

Hmmmm.

Turns out that the review page was a casualty of the migration of the Looking Closer from one network to another many years ago. So, for the sake of the record, I'm restoring those original comments on the film here. I wouldn't count this as one of my finer pieces of writing, but then the movie didn't inspire me to invest much time or effort in reviewing it. But as there is a generation of VeggieTales fans, and as I am a huge fan of VeggieTales creator Phil Vischer, as one of the original writers of Bob and Larry dialogue is a close friend of mine... I figure I should restore my coverage of this curious moment when Bob and Larry made it to the big screen.

So, for whatever it's worth... here it is.

The “big idea” of Veggie Tales' is to loosely retell Bible stories with a cast of garden-variety characters. It's not a far cry from the way The Muppets used to re-enact famous movie scenes or fairy tales. (The Muppets' The Frog Prince, A Muppet Christmas Carol, and Muppet Treasure Island are wonderful examples.)

It’s an idea that has sold a zillion videotapes and made Bob the Tomato and Larry the Cucumber household names. Kids are being introduced to Bible stories in a way far more memorable and entertaining than the flannel-graph my Sunday School teachers used to use.

The VeggieTales' new movie — straightforwardly titled Jonah: A VeggieTales Movie — is a great example of how hard it is to effectively adapt such a story for children. It represents an ambitious step forward for the company. But unfortunately, as much as I was looking forward to the laughs and the cleverness of a feature-length episode, the movie only provoked a couple of chuckles and more than a few winces. For those who aren't familiar with the series and its charms, I think this film will be a poor introduction that won't offer compelling reasons to visit the series.

You know how it goes: Jonah the Prophet doesn’t want to obey God's order — to go to Nineveh and tell the wicked Ninevites to repent of evil ways. So he runs, gets thrown out of a ship, swallowed by a whale, and then tossed up onto the shore. Humbled, he goes to Nineveh after all and delivers the message.

Once the Jonah story began, I was ready for the fun to really begin. But alas, this is where the air started leaking from the balloon.

Jonah himself is the biggest problem with Jonah. Most kids, and most adults as well, won't find him compelling, interesting, or funny. He's a stuffy asparagus with a monocle and a snooty way of talking that just put me off from the get-go. He's not someone we can relate to. Then he picks up a rather annoying sidekick, Khalil, who seems out-of-place if only because he's not a vegetable—he's a caterpillar. You can tell the animators love him and think he's a million laughs, but he's not. He's not an abomination like Jar Jar Binks, but he's certainly not funny enough to steal the show. Nevertheless, he dominates the rest of the film, wearing out his redundant punchline fairly quickly.

The other strength of the video shows are the "silly songs." Here, there are a handful, yes, but they're not terribly silly or clever. They're spirited and fun, but not nearly as memorable as those I have sung alongside my enthusiastic nephews and nieces while watching the show.

I'll explain. I got a chuckle out of these revisionist Veggie-Tales Ninevites. They're not wicked in any truly troubling ways, but instead have the absurdly rude habit of slapping people with fish. It's this kind of Python-esque lunacy that makes VeggieTales better than flannel-graph. But when we realize that God is threatening to destroy the city with a blast of fire from the sky, it seems rather harsh punishment in view of the scaled-back sins of this adaptation. Couldn't they have come up with a softer punishment to fit the softer crime? As in Scripture, Jonah looks forward to the destruction, but here his apocalyptic imaginings are played for laughs. On Ninevite who escapes is shown being "zapped" by God, finishing the job. That's as morbid as VeggieTales' humor has ever been, and I found a little too irreverent.

Side Note:

I always thought "fire and brimstone from heaven" was a terrifying prospect even when the peoples in Scripture were engaged in the basest forms of sin. Modern times have made me wonder if the supernatural judgment of God in the Old Testament wasn't their naive perception of the curses mankind brings upon itself, the logical "wages of sin." After all, we have seen in recent years how humanity manages to make fire rain down from the heavens and plagues up from the rivers. But that's mere speculation.

There's more. When Jonah is running from God by sailing the high seas, he and his fellow sailors interpret the the oncoming storm as a punishing act of God. That strikes me as a strange lesson for kids: Storms and hardship should be interpreted as God’s disapproval with you or your house. Sure, it's there in Scripture, but there it's a superstition of the sailors that happened to prove true this once. I don't think it is presented in that story as a wise way of interpreting circumstances.

The story wraps up abruptly, with a whimper instead of a bang. The conversion of the Ninevites happens so abruptly, there is no sense of excitement or awe. It just seems awfully contrived.

The fact that the filmmakers try to show off their digital prowess is also distracting. The "camera" keeps pulling back, the way Disney movies do when they want to show off their new animation techniques. Sure, Big Idea has done some decent digital work here, about on par with last year's "Jimmy Neutron"—impressive considering Big Idea is a smaller operation than Pixar. But they won't earn many gasps for their visuals yet.

We know the story of Jonah. We know the story ends while Jonah still "has issues." This makes the story of Jonah very difficult to package in the formula of satisfactory children's entertainment. The storytellers make an admirable attempt, by having the Jonah story told to a group of characters who have a story of their own, so the epiphany occurs outside of the Jonah story. But they fumble that too, ending the story on a strangely false note that again confirms the animators are very excited about their new, non-vegetable member of the cast.

I commend the storytellers for focusing on God being the Lord of Second Chances. Our society is too often lectured by televangelists that the main reason they should turn to Christ is because God will condemn them to the everlasting broiler if they don't. That's not the gospel as Jesus presented it. It's a good thing to remind audiences that God is a God of grace. I am not denying that misery awaits those who deny God... misery of their own devising, their own choosing, misery they're probably already getting acquainted with. But scare tactics are not an admirable way to try and change lives. The results are usually as temporary as the influence of a horror film. Devotion to God comes from encountering His love and His grace and the freedoms open to us when we follow his commandments. These guys have that part down. That's a relief.

I trust there are better things ahead for Big Idea. God is, after all, the God of "second chances."

ANOTHER SIDE NOTE:

Hmm, something just struck me.

Could it be that the "fish-worship" and the "fish-slapping" are a subtle reference to the "fish symbol" embraced so widely by evangelical Christians who then use their "salvation" to slap other people around, brandishing Christian faith as a tool for judgment and legalism?

Could it be a subtle suggestion that contemporary Christians might "wise up" and treat each other and unbelievers with respect and compassion and kindness?

Nahhhhhhhh.....

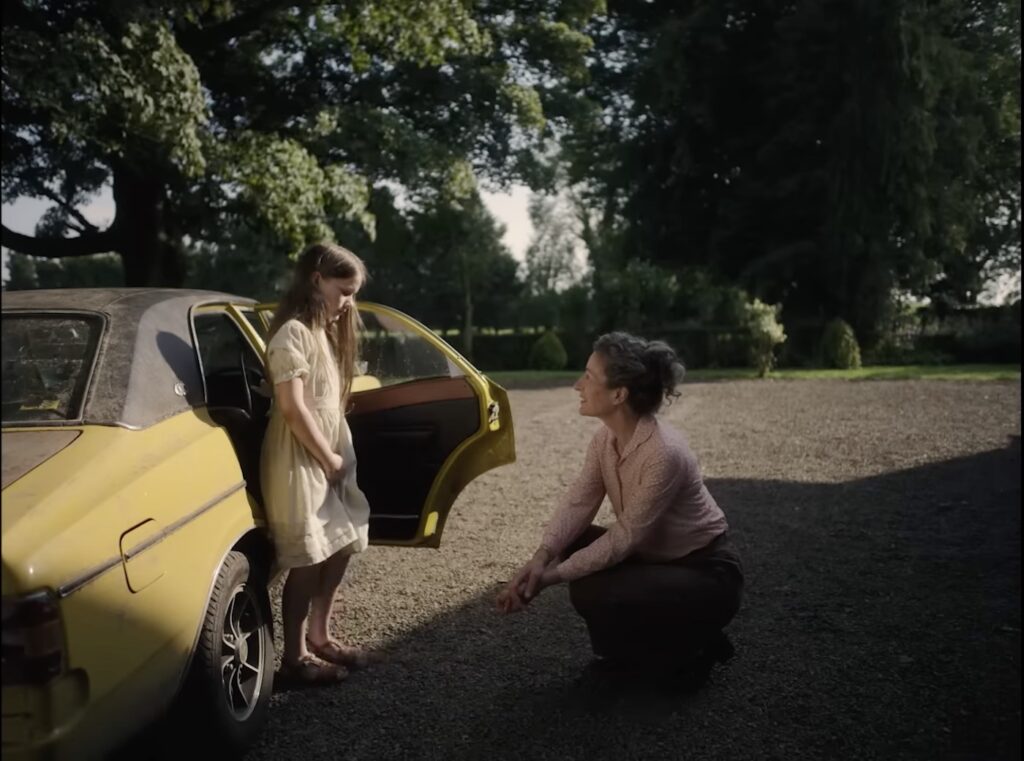

The Quiet Girl (2023)

[This first edition of this review was originally published at Give Me Some Light. To be among the first to read Overstreet's reviews, become a subscriber!]

One cinephile at Letterboxd calls The Quiet Girl “a much darker, slower, and, well, QUIETER version of Anne of Green Gables.”

I wouldn’t have thought of that, but I like it. Just as L. M. Montgomery’s novel follows an orphan girl’s coming of age, The Quiet Girl is about a young girl who begins — or, rather, begins again — to figure out how the world works, and what her part in it might be, in the context of a volunteer family.

And yes, it is darker.

This Anne — her name is Cáit, and she’s played with an angelic luminosity by newcomer Catherine Clinch — isn’t so much an orphan as a victim of abuse, abuse that culminates when she is sent away to live with relatives. We don’t see Cáit beaten or molested, although her wounded silences could suggest that either might have occurred behind closed doors. We see that both parents misunderstand her withdrawn and almost-wordless state. We see that her father (Michael Patric) is a compulsive gambler, an irascible drunk, an adulterer, and a terrible farmer who is destroying the family with his darkness and lies. We see that her mother (Kate Nic Chonaonaigh) is exhausted, traumatized, and pregnant with yet another child that the family cannot support.

Whatever the nature of Cáit’s sufferings, she is the one that the family chooses to cast off first in their accelerating downward spiral. She lands with the Cinnsealachs (pronounced “Kinsellas”) — her mother’s first cousin Eibhlín (Claire Crowley) and her silent-type husband Seán (Andrew Bennett) — who are well-off by comparison, and who live together in an attractive but strangely haunted house. And by “haunted,” I don’t mean what you might think. This house may have a mysterious stillness at its heart, but isn’t haunted like those manors of gothic horror that so often become the furnaces in which the young children of our imaginations burn. This one is Edenic, infused with light and enchantment such that we might wonder if the Cinnsealachs’ generosity and grace have brought the property itself alive with gratitude. And Cáit responds as if she is a rare and exotic flower that has been shriveling up in a dark basement and is suddenly transported to her ideal place in the garden — her roots drink up the grace with a desperate thirst, and then her eyes open wide, her downcast countenance lifting and turning toward light as if toward some Higher Power. As she is loved, and as she begins to discover a larger world of possibility, she begins to find her voice.

I admit that I had assumed this was a story about a girl who doesn’t speak, one who would probably find her voice at the movie’s emotional climax. That isn’t, thank goodness, the case! Cáit has plenty to say throughout. This is, instead, a movie about the extraordinary power of people who have the patience and generosity to listen to the soft-spoken, the uncertain, and the insecure. And in that, it offers us one of the rarest cinematic wonders: a celebration of how children can flourish in an ideal environment, rather than yet another portrayal of how they suffer in nightmarish conditions. How many movies have been made in what feels like a lament over terrible childhoods? Those are necessary and powerful testimonies. But portrayals of any plausible possibility of goodness are so rare in art that we need to seize, lift up, and celebrate them when we find them.

Another way in which this story differs from that beloved Montgomery classic — unlike Anne of Green Gables, The Quiet Girl might work well as a stage play with a cast of only a few actors. Cáit isn’t destined to become a plucky and influential player in a community of recurring and engaging characters. Oh, the Cinnsealachs have visitors on occasion — Seán has his drinking buddies who stop by for a round of cards, and Eibhlín shines with the benevolence of a guardian angel in her community of older women. But we glimpse only a few other children in the area, and they seem like undisciplined beasts by comparison. For the most part, Cáit is on her own, a studious observer whether indoors or outdoors. Her conflict is mostly interior: She’s torn between two worlds. Should she go back to the hell where her siblings remain? Or remain in this heaven-on-earth tended by this aging and childless couple (one of whom is even “quieter” than she is)?

But then again, could it work onstage at all? The strengths of director Colm Bairéad’s film are largely cinematic. It would have to develop under the direction of a particularly talented theater director who could convey to a theater audience what this film gives us through up-close observation, through eloquent silences, and through its characters’ subtle shifts in body language and expression. Cinematographer Kate McCullough does some glorious work here.

Change any of this film's precariously balanced performances even a little and the whole thing falls apart. The needle quivers between the extremes of Too Much and Too Little, Too Melodramatic and Too Restrained, Too Sentimental and Too Harsh. That is to say, it feels — for the most part — real.

To say much more would be to disrupt your experience of the film. Suffice it to say that Bairéad choreographs some breathtakingly truthful moments, but he contrives others that feel a little too calculated. I just wish the last shot of the movie was subtler and more surprising, and that it didn't feel so inevitable. (I'm reminded of the last shot of Close earlier this year, during which I could almost feel the filmmakers congratulating each other for achieving a solid gut-punch that would have audiences reaching for their tissues as the credits rolled.)

Still, I suspect my love for this film is more likely to increase than diminish with subsequent viewings — largely due to the cast. Claire Crowley makes Eibhlín an incandescent force of benevolence. And, as Cáit, Catherine Clinch is unnervingly convincing (if occasionally a little too angelic).

But Andrew Bennett is, for me, The Quiet Girl’s MVP. As the humble, grieving, and hard-working Farmer Seán Cinnsealach, he's exquisitely complicated and surprising. I keep wondering how seriously I’m supposed to take the title’s inescapable similarity to another famous film about Ireland — John Ford’s The Quiet Man. Whatever the case, Seán’s character seems a different species altogether from the brawny and conventional masculinity of John Wayne. And that’s a good thing. It's his performance that I'm eager to spend more time with. That’s the treasure among treasures in this film that I’m most eager for you to discover.

And don’t just take my word for it. It’s not often you come across high praise of this nature:

“… like a slow, gentle walk through a garden where beauty unfolds, surrounds, and ultimately overwhelms. It is good to grasp onto love, in giving and receiving—we must hold tight to it when find it, no matter how brief it may last.” — at Letterboxd, Michael Asmus

“Simple human kindness. There seems to be so little of it in the real world sometimes that when you find so much of it in a humble movie like this one, it feels like you’ve struck oil.” — at Letterboxd, Matt Singer of Screen Crush

“Roger Ebert liked to say that it was never the sad moments in movies that moved him the most, but rather when characters showed each other unexpected kindnesses. I’m wired much the same way. … It's a delicate film of small gestures and the slow building of trust.” — at WBUR, Sean Burns

“This movie shows that anyone can thrive as long as they are shown care and attention and are considered valuable for who they are by those raising them and that chosen families can be vastly superior to biological families. … So much healing could take place in our world if all/most children were actually shown genuine, consistent love while growing up.” — at Letterboxd, Adam Graff

“… a pleasant respite from the chaos of modern society. When people long for simpler times, Colm Bairéad’s film might be what they think of. Not that the movie is free of drama, but how director Bairéad and cinematographer Kate McCullough capture these tender moments makes even instances of anguish seem comforting.” — at Boulder Weekly, Michael J. Casey

Overstreet's Favorite Films of 2022 — Part Three: The Top Ten

This weekend, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences will pretend to know what the "best" movies of 2022 are. (They'll probably give the Big Award to Everything Everywhere All at Once... or, maybe The Fabelmans.)

And I will suffer through it as usual — the flaunting of wealth, the idolatry, the absurd popularity contest — just to savor those few moments when we see real human beings expressing their gratitude to other human beings for their support and inspiration.

"Best." Okay. Come on. No human beings have seen all of the feature films of 2022. Very few have seen several 2022 releases more than once., Far fewer would be able to demonstrate that they are moviegoers with enough education, experience, and insight to engage in substantial critical conversation. And far fewer have engaged in ongoing and substantial conversations about many of those films. So... no. It's my opinion that nobody anywhere is qualified to declare the "Best Films" of 2022. And those that do should admit that this is all a dubious and speculative endeavor.

Switch the word Best for Favorite ... and we have a whole new conversation.

What are your favorite films of the year? And why? If you tell me that, you're probably telling me as much about yourself as you are about the films. And that's a good thing! I want to get to know you. If I tell you about my favorites, you'll learn a lot about me: my history, my beliefs, my loves, my fears, my questions, my idiosyncrasies.

What if the Academy switched the word "Best" with "Favorite" for each award? That would be more honest. The awards would much more clearly represent which films they want to honor at this moment, given the limitations of their own viewing and understanding?

But I've ranted about these things before. Let's change the subject...

Paid subscribers to my journal Give Me Some Light got to read this list

more than two weeks ago, and they also get to see exclusive video reviews

of each film in my top ten. Subscriptions to exclusive posts are only

five bucks a month.

2022 was the year we found out if the big-screen experience was a thing of the past or not. And the answer was (much to our relief) "No!"

Not yet, anyway.

Crowds packed the house for Top Gun: Maverick and Avatar: The Way of Water and Everything Everywhere All at Once. And I got the cinemas to see movies the way they were meant to be seen many, many times this year. Big blockbusters, arthouse films from overseas, obscure documentaries — all projected onto a big screen in front of a community. I went with groups of friends; I took Anne out on movie dates; and I saw quite a few "alone" but in the company of my neighbors. And I had the joy of seeing my favorite film of the year at the Seattle International Film Festival's Uptown alongside some of my students in the midst of a huge and celebratory audience that laughed and cried together. 2022 was one of the richest moviegoing years of my life, and it seems like new waves of creativity are transforming cinema, with the most imaginative and wildly unconventional Oscar Best Picture nominee of all time looking likely to win the award. That's so encouraging.

I've invested more time and energy in reading about, discussing, and writing about the movies of 2022 than I ever have for a film year before. You can track my writing, my conversations, my second-thoughts, and more in a variety of places: here at Looking Closer, on Letterboxd, on my new Substack journal Give Me Some Light, on the movie-year-in-review episodes of Veterans of Culture Wars (Part One and Part Two), and beyond.

10

- Writers and directors: “Daniels” (Daniel Kwan and Daniel Scheinert)

- Synopsis via Letterboxd: “An aging Chinese immigrant is swept up in an insane adventure, where she alone can save what’s important to her by connecting with the lives she could have led in other universes.”

- My synopsis (from Looking Closer): “Evelyn (played by the great Michelle Yeoh) lives an exasperating life of multi-tasking as a wife trying to save her marriage to Waymond (Ke Huy Quan); a mother trying to save her relationship with her despairing daughter Joy (Stephanie Hsu); a laundromat manager trying to save the family business from an aggressive auditor (Jamie Lee Curtis); a daughter trying to take care of her declining father Gong Gong (James Hong); and a dreamer (a novelist, a singer, and more) trying to sustain her romantic hopes — but when she discovers that she is just one of countless Evelyns living different lives across an incomprehensibly complicated ‘multi-verse,’ she must learn to advance her multi-tasking skills exponentially in order to fight a demonic power called Jobu Tupaki, a black hole that threatens to suck all meaning from the universe, and that is rapidly corrupting her daughter.”

Here at Looking Closer, you can read my mulitiple conversations about multiple viewings of this multi-verse movie.

Listen to me rave about this film in Part One of the Veterans of Culture Wars annual special on "The Best Movies of 2022."

Paid subscribers to Give Me Some Light have access to my video review of this film.

9

- Director: Maria Speth

- Synopsis via Letterboxd: “Mr. Bachmann And His Class explores the close bond between an elementary school teacher and his students. His unconventional methods clash with the complex social and cultural realities of the provincial German industrial town they live in.”

Here are my Letterboxd notes.

Listen to me rave about this film in Part Two of the Veterans of Culture Wars annual special on "The Best Movies of 2022."

Paid subscribers to Give Me Some Light have access to my video review of this film.

8

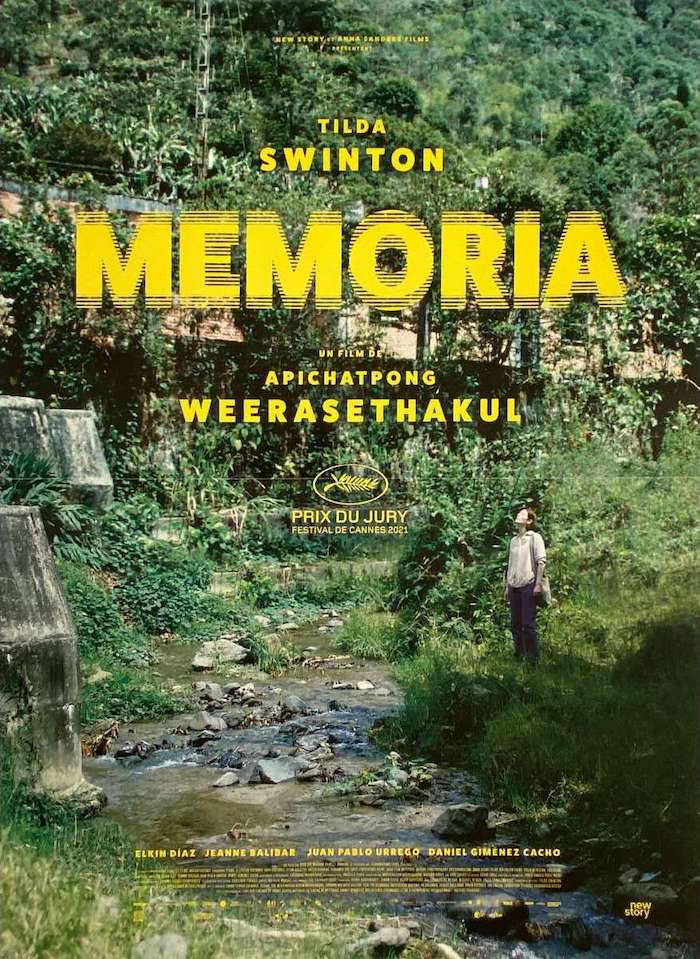

- Writer and director: Apichatpong Weerasethakul

- Synopsis via Letterboxd: “A Scottish orchid farmer visiting her ill sister in Bogotá, Colombia, befriends a young musician and a French archaeologist in charge of monitoring a century-long construction project to tunnel through the Andes mountain range. Each night, she is bothered by increasingly loud bangs which prevent her from getting any sleep.”

Here’s my review.

Listen to me rave about this film in Part Two of the Veterans of Culture Wars annual special on "The Best Movies of 2022."

Paid subscribers to Give Me Some Light have access to my video review of this film.

7

- Writer and director: Martin McDonagh

- Synopsis via Letterboxd: “Two lifelong friends find themselves at an impasse when one abruptly ends their relationship, with alarming consequences for both of them.”

Here are my Letterboxd notes for the first viewing and the second viewing.

Paid subscribers to Give Me Some Light have access to my video review of this film.

6

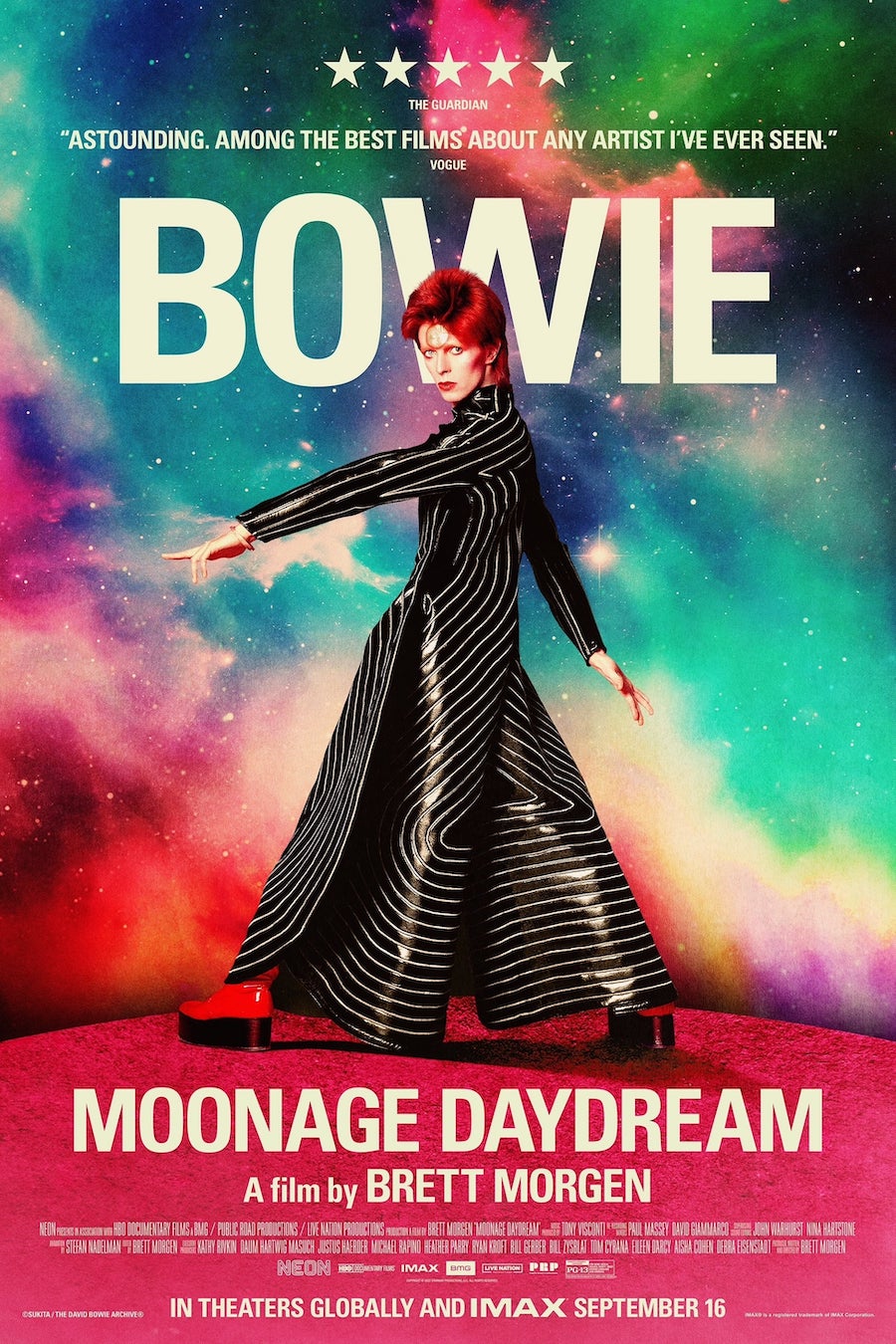

- Director: Brett Morgen

- Synopsis via Letterboxd: “A cinematic odyssey featuring never-before-seen footage exploring David Bowie’s creative and musical journey.”

Here are my Letterboxd notes.

Listen to me rave about this film in Part Two of the Veterans of Culture Wars annual special on "The Best Movies of 2022."

Paid subscribers to Give Me Some Light have access to my video review of this film.

5

- Director: Steven Spielberg

- Writers: Steven Spielberg and Tony Kushner

- Synopsis via Letterboxd: “A coming-of-age story about a young man’s discovery of a shattering family secret and an exploration of the power of movies to help us see the truth about each other and ourselves.”

Here are my Letterboxd notes.

Listen to me rave about this film in Part Two of the Veterans of Culture Wars annual special on "The Best Movies of 2022."

Paid subscribers to Give Me Some Light have access to my video review of this film.

4

- Writer and director: Sarah Polley

- Based on the novel Women Talking by Miriam Toews.

- Synopsis via Letterboxd: “A group of women in an isolated religious colony struggle to reconcile their faith with a string of sexual assaults committed by the colony’s men.”

Here are my Letterboxd notes.

Listen to me rave about this film in Part Two of the Veterans of Culture Wars annual special on "The Best Movies of 2022."

Paid subscribers to Give Me Some Light have access to my video review of this film.

3

- Writer and director: Alexandre Koberidze

- Synopsis via Letterboxd: “In the Georgian riverside town of Kutaisi, summertime romance and World Cup fever are in the air. After a pair of chance encounters, pharmacist Lisa and soccer player Giorgi find their plans for a date undone when they both awaken magically transformed with no way to recognize each other.”

Here are my Letterboxd notes.

Listen to me rave about this film in Part Two of the Veterans of Culture Wars annual special on "The Best Movies of 2022."

Paid subscribers to Give Me Some Light have access to my video review of this film.

2

- Writer and director: Kogonada

- Synopsis via Letterboxd: “When his young daughter’s beloved companion, an android named Yang[,] malfunctions, Jake searches for a way to repair him. In the process, Jake discovers the life that has been passing in front of him, reconnecting with his wife and daughter across a distance he didn’t know was there.”

Here are my Letterboxd notes.

Listen to me rave about this film in Part Two of the Veterans of Culture Wars annual special on "The Best Movies of 2022."

Paid subscribers to Give Me Some Light have access to my video review of this film.

1

- Director: Dean Fleischer Camp

- Writers: Dean Fleischer Camp, Jenny Slate, Nick Paley

Synopsis via Letterboxd: “Marcel is an adorable one-inch-tall shell who ekes out a colorful existence with his grandmother Connie and their pet lint, Alan. Once part of a sprawling community of shells, they now live alone as the sole survivors of a mysterious tragedy. But when a documentary filmmaker discovers them amongst the clutter of his Airbnb, the short film he posts online brings Marcel millions of passionate fans, as well as unprecedented dangers and a new hope at finding his long-lost family.”

Listen to me rave about this film in Part Two of the Veterans of Culture Wars annual special on "The Best Movies of 2022."

Paid subscribers to Give Me Some Light have access to my video review of this film.

Overstreet’s Favorite Films of 2022 — Part Two: Top-Ten-Worthy Runners-Up

If you read through Part One, which was a list of epic proportions, you already have a long list of 2022 feature films I'd recommend — for the challenges, for the surprises, for the imagination, for the wisdom.

But wait — there’s more!

Those were the “Honorable Mentions.” These?

The fifteen films on this — the "Top-Ten-Worthy Runners-Up List" — all belong in my Top Ten List for the year,

and I cannot believe I'm not including them on that list.

If I’m being honest, I’ll admit that any one of these might suddenly be bumped up into the Top Ten next time I see it, because all of these gave me so much to discover, enjoy, and ponder — and a sense that there’s so much more to discover, enjoy, and ponder next time that I never realized the first time. And yes, I will be watching all of these again.

If you have thoughts about any of them, or if you want to link to your own reviews, post them in the Comments! I want to learn more. I want to be persuaded.

As I wrote this post, I was ranking them in order of how eager I am to see them again. But eventually I gave up. If my Top Ten had never been released, I’d have looked at these and said “What an extraordinary year!” anyway.

For what it's worth: Subscribers to my new online Substack newsletter Give Me Some Light received this list in its entirety a few weeks ago. If you want to get posts like this one early, subscribe!

Note:

Some of these films (The Worst Person in the World and Petit Maman, for example) played in festivals and in NY/LA awards-qualifying runs in 2021. But I’m counting them as 2022 releases because that’s when they came off of the festival circuit and gained a wide release — either in theaters or streaming — so that I, in the cinema-savvy city of Seattle, could access them without getting them on a plane. I think it’s safe to say that the vast majority of American moviegoers couldn’t have seen them before 2022, and thus they became a part of the common cinephile conversation in 2022. There. That’s how I rationalize my standards on a subject that is always maddeningly subjective.

https://youtu.be/vm3B-fDc9Xw

Writer and director: Hirokazu Kore-eda

Synopsis via Letterboxd: “Sang-hyeon is the owner of a launderette and a volunteer at the nearby church, where his friend Dong-soo works. The two run an illegal business together: Sang-hyeon occasionally steals babies from the church’s baby box with the help of Dong-soo, who deletes the church’s CCTV footage that shows a baby was left there, and they sell them on the adoption black market. But when a young mother, So-young, comes back after having abandoned her baby, she discovers them and decides to go with them on a road-trip to interview the baby’s potential infertile parents. Meanwhile, two detectives, Soo-jin and Detective Lee, are on their trail.”

From my Letterboxd notes:

I went to see Broker reluctantly tonight.

I was feeling beaten down by hardships, and betrayed by those who speak of grace and love when they're at a microphone but then, behind closed doors, contrive to deny such things to those who need them.

And so, the prospect of dedicating an evening to a movie that puts words like "COMPASSION" and "TENDER" in the trailer in all caps... well, it felt like it might just add insult to injury. Fantasies with happy endings can really sour my spirit if the world is making such things seem impossible.

Shouldn't I know better by now? Hirozaku Kore-eda's Shoplifters showed up at the very end of 2018, and I approached that one warily as well. It overcame my cynicism and delighted and moved me so much it catapulted into my top 10 for that year. But no, I still haven't learned my lesson. I'm still braced to suffer a movie that feels manipulative or superficial in its comforts. I'm not in the mood for art that contrives hopefulness out of wishful thinking.

But in Broker, as in Shoplifters, the world is the problem — not Kore-eda's hopefulness. I think his strength comes from the fact that he knows that the world is in dire straits, and he portrays that with honesty born of experience. (This is the guy who made the harrowing Nobody Knows, after all.) But in his recent storytelling, he's begun to remind me a little of Miyazaki: Where others tend to invest their talents in spectacular visions of trouble and violence, he gives his all to discover poignantly human moments of goodness, gentleness, generosity, insight, and decency. And his gift is that he not only finds them, but he draws performances from actors that make those moments ring true.

And, as a result, Broker, like Shoplifters, is good medicine for weary hearts, and, yes, one of my favorite films of 2022, which has been an outstanding year in cinema.- - -Song Kang Ho is quickly becoming one of my favorite actors. He's pure joy here. And IU (Lee Ji-eun) is positively radiant.

https://youtu.be/In8fuzj3gck

Writer and director: Jordan Peele

Universal Pictures Synopsis (via IMDB): “After random objects falling from the sky result in the death of their father, ranch-owning siblings OJ and Emerald Haywood attempt to capture video evidence of an unidentified flying object with the help of tech salesman Angel Torres and documentarian Antlers Holst.”

From my Letterboxd notes:

I loved the big-screen spectacle of this. And, as with his first two films, Peele is wryly commenting on (and, at times lamenting) cultural sins that have gone unacknowledged and unresolved.

…

It's hard to cook up, at this point, a fresh take on UFOs for a summer blockbuster, and I applaud Peele for serving something clever and surprising. I also applaud his cast: As the central horse trainer whose ranch is terrorized by a mystery, Daniel Kaluuya dials everything down where most actors would have cranked things up. He's so, so good at this. Keke Palmer is funny, spirited, and frantic as his sister. Steven Yeun is strange as a trauma survivor and showman in an adjacent storyline (which provides the true horror of the film) that helps us interpret what's going on in the main narrative. And, well, what a joy to see Michael Wincott in a significant big screen role again as something other than a sneering villain!

But if I were at the writing table, I'd have recommended they leave the title... in the title. It's spoken several times in the film with diminishing comic returns.

https://youtu.be/ZKLu3t-G9Do

Writer and director: James Gray

Synopsis by Letterboxd: “A deeply personal coming-of-age story about the strength of family and the generational pursuit of the American Dream.”

From my Letterboxd notes:

Jeremy Strong in the last act of Armageddon Time looks and moves so much like my father that I may never recover. Same jacket, cap, glasses, hair, expressions. Uncanny. If his voice had been anywhere close to my dad’s, I’d have had to leave.

My father never beat me. Never discouraged my desire to make art. Never told me to get a real job. Never shouted at me. Gave everything so I could go to a good school and practice creativity. I am so grateful.

But then my family and community rejoiced when Reagan won. “A good Christian man” who would do something about crime and drugs. The best thing about the rich getting richer was that the success would trickle down to the poor! Well… we know how that turned out. (I wouldn’t wake up to the ugly truth about those old reliable GOP bullshit tactics about wealth, whiteness, “law and order,” and posturing as “pro-life” for many years.) So… we had our problems. What’s more — I never had more than one black classmate at my evangelical Christian private school, and remained ignorant of and uncomfortably disinterested in all questions about race—or poverty, for that matter—until college.

So, this film—although it feels frustratingly guarded and muted, like every aspect from the camera to the performances are being held back, and although its white-guilt penance is heavy-handed—is nevertheless going to stick with me as a film in which I saw a life very like my own, meaningfully similar, meaningfully different. I see so many ways in which my community’s privilege and fear kept me sheltered from necessary truths of the world, so many ways in which I was spared hardship and blessed with priceless gifts.

https://youtu.be/Od2NW1sfRdA

Directors: Guillermo Del Toro and Mark Gustafson

Writers: Guillermo Del Toro and Patrick McHale

Synopsis via Letterboxd: “During the rise of fascism in Mussolini’s Italy, a wooden boy brought magically to life struggles to live up to his father’s expectations.”

From my Letterboxd notes:

Well... it's truth in advertising:

Gorgeous puppetry and extravagant sets.

Darker, stranger, and braver storytelling than Disney animation has ever dared (and thus truer in spirit to "the old tales" like Collodi's 1883 original).

And, above all, it's Guillermo Del Toro's Pinocchio — a re-imagining of Collodi's strange story in a way that allows the enfant terrible of big-screen fantasy to preach another conflicted and ultimately confusing Del Toro Gospel — Christianity-reviling and yet Christ-haunted at the same time — even as he indulges increasingly familiar and derivative-of-themselves Del Toro fantasies.

…

For me, the most interesting thing about Del Toro's films is that, despite their childish attachment to moments of cathartic violence against villains, and their increasingly predictable attacks on Christianity as merely a system for exploiting people's hopes and keeping them in line... the philosophy these films illustrate feels at war with itself, incongruous with the "deeper magic" of mythology to suggest something timeless and eternal.

There is a lot of energy expended here on emphasizing the connection between the church and fascism. What complicates that in a fascinating way is how the figure of Jesus — so surprisingly prominent here — manifests as a "puppet," a character carved from wood, fitted together with puppetry joints, and lifted up for people to marvel at in ways that allow evil men to exploit the enchanted. In a way, Jesus himself escapes the complaint. The real enemies here are manipulative and abusive institutions, not the Gospel itself. The accusations are fashioned to criticize a corrupt religious establishment rather than the Loving and Living Word of God.

But Del Toro never seems to figure out how to reconcile this. He throws the Baby Jesus out with the dirty bathwater he's been immersed in. He has to dismiss the possibility of "eternal life" and a Loving God, reducing everything to the popular and practical gospel of just "being good" — one that doesn't seem to work out too well in the real world.

- - -

Fortunately for audiences, there are other forces at work in Del Toro's storytelling than his reductive philosophies. Maybe that's why he keeps telling stories. Maybe they aren't finished with him yet.

I can't help but notice that Geppetto still sleeps under a sign of the cross, and it's still there at the end of the film, like something Del Toro can't bring himself to give up.

https://youtu.be/d9BR3Z_-Hh8

Director: Park Chan-wook

Writers: Jeong Seo-kyeong and Park Chan-wook

Synopsis via Letterboxd: “Hae-Joon, a seasoned detective, investigates the suspicious death of a man on a mountaintop. Soon, he begins to suspect Seo-rae, the deceased’s wife, while being unsettled by his attraction to her.”

From my Letterboxd notes:

On how much Hitch could Park Chan-Wook riff

if Park Chan-Wook could riff on Hitch?

Park Chan-Wook would riff on all the Hitch he could

if Park Chan-Wook could riff on Hitch!

And, in fact, he has! Decision to Leave finds Park Chan-Wook riffing on so much Hitchcock that it seems like the old master deserves to have his name in the credits!

I mean... my head was spinning so violently with how many reversals of the famous Stewart/Novak dynamics Park wove into this long (over-long?), complicated (over-complicated?) tapestry that I got dizzier than Jimmy Stewart standing on a stepladder.

-

- Cops and detectives chasing crooks across rooftops.

- A rocky precipice above violent, smashing waves.

- The shots of Detective Hae-jun driving slowly behind his suspect and even commenting on how he enjoys trailing a mark.

- A vivid bouquet.

- A shot with the tormented cop/femme fatale against a mirror image emphasizing the ways in which they are "doubled."

- The "vertigo" shot (the dolly zoom).

- The low-angle shots of Park Hae-il as the discombobulated detective, often looking down from high places.

- And even a literal whirlpool that would've made Hitchcock wish he'd thought of that as another variation of the spirals that are the engines of Vertigo.

I'm both delighted by the giddy extravagance of these relentless callbacks/tributes/spoofs of Vertigo and frustrated with how they constantly disrupt my suspension of disbelief. I've never really been on Park Chan-Wook's wavelength — I'm sure it's not him, it's me — and until now Stoker was the only film of his I've really enjoyed (I have some admiration for aspects of Thirst, but I've always disliked Oldboy). But I enjoyed this as much as Bong's Parasite, and I'm glad it's in the running for the Oscars' International Feature award. I just can't tell how much of my enjoyment is about my love for Vertigo and how much I care about this film apart from that clever re-imagining.

https://youtu.be/55M5ZgAqbWo

Director: Joachim Trier

Writers: Joachim Trier and Eskil Vogt

Synopsis via Letterboxd: “Chronicles four years in the life of Julie, a young woman who navigates the troubled waters of her love life and struggles to find her career path, leading her to take a realistic look at who she really is.”

From my Letterboxd notes:

More than any other movie I can think of right off the top of my head, this is a movie that will quickly divide audiences into moviegoers who judge a complicated character and moviegoers who are curious about and capable of empathizing with a complicated character.

Julie is a character whose decisions hurt people all around her, behavior I was taught to condemn. But Trier's film draws us into such intimacy with Julie that eventually it becomes possible to see just how much the world she's in has been harming her, starving her, depriving her of being seen and known (especially by herself). The fact that she ends up harming most another complicated, imperfect human — who, I believe, loves her and knows her better than most — is a shame. But people who are neglected and disrespected and made to feel unvalued from childhood run on deeply fractured software, and loving them as they find their way through the wreckage of their hearts and minds is costly. I've seen it happen in so many relationships. I've been in those relationships. I've been impatient with and dismissive of people like Julie. And, frankly, I know that anyone who dares to love me is in for some rather disappointing revelations — so there are moments when I recognize my own most-alarming behaviors in Julie.