Ten years ago this month...

An anniversary slipped past me on October 5.

Ten years ago this month, I signed the contract for my first two novels. I remember that I could hardly believe it.

I'm grateful that I was provided all that I needed to rise to the occasion. I'm grateful for all that Anne and others did to make it possible for me to immerse myself in another world and write down what I found there.

I'm grateful for my agents: the inspiring Don Pape, and the resourceful Lee Hough (may he rest in peace). I am grateful for my insightful editors: Shannon Marchese and Steve Parolini. They all cared not just about the contracts, but about my head and my heart and my marriage.

I'm grateful for the support that I had at the office. I'm grateful that I had the chance to apply the skills that I had focused on sharpening in my years as a student at Seattle Pacific.

Since I was six years old, I have felt closest to God, and most like myself, in the process of discovering and shaping a new story.

Things beyond my control have changed my world considerably; I've had resources taken from me that enabled me to do that work over a period of six years. I don't feel like myself in these days of perpetual fragmentation and interruption, where hours of solitude are few and far between. But I know that that short season of my life was a gift, one that I had not expected; there was no promise that life would allow me to go on writing novels.

And I haven't given up hoping that the burdens and stresses of my current circumstances will someday diminish, and that I'll find enough peace and space to immerse myself once again in imagination. I think I've grown as a writer, and learned through those experiences. There are so many stories I would love to put down on paper, so many more visions I'd love to share.

Maybe next year, if God is willing.

If you feel moved to say a prayer toward that end, I would be grateful.

In the meantime, I am blessed whenever I get a note from a reader who reminds me that my characters are alive and out there in the world living lives of their own, thanks to the goodness of my friends and family, and by the grace of God.

I am still mystified by how it all came about. And grateful beyond my capacity to express to have had those opportunities.

Certified Copy (2010)

It's October 2015, and I haven't seen a film yet this decade that I love more than the one that I saw for the first time five years ago this month: Certified Copy, by Abbas Kiarostami.

Here are the first impressions that I wrote at the time for Good Letters, the Image blog.

•

This is about a new film called Certified Copy. But it’s not a movie review.

It could be. I could describe the story. I could tell you about its awards and honors. I could assess the actors’ performances (Juliette Binoche is better than ever, and William Shimell, an opera singer, is arresting in his first film role).

But no, I can’t treat Certified Copy with a movie critic’s typical detachment. I’m in love with it, you see. I’ll have seen it six or seven times by the end of the year. And I’m grateful for all that the filmmaker — Abbas Kiarostami — is revealing to me through this film.

Let me describe one of the early scenes:

A well-dressed Englishman (Shimell) has descended a stairway into a small art gallery in Southern Tuscany. The art dealer, an attractive but anxious French woman (Binoche), watches as her customer examines original works and replicas.

Why is she nervous? Is it because her customer is an accomplished art critic? Is she a fan? Does she have a crush on him?

“We certainly have a shared interest here,” he muses, studying the art.

She disagrees. “I just ended up here by accident. I’m in the middle of all of these things, but I don’t really care about them.”

Approvingly, he says, “You should keep your distance. They’re attractive enough, but they can be bad for you.”

“Are you serious?” she laughs.

He is. He says that works of art can be dangerous. “I study them. I admire them. I write books about them. But I keep my distance too.”

He then confesses that he doesn’t keep works of art in his house. He prefers practical, useful things. If something isn’t useful to him “I just throw it out,” he says.

He then confesses that he doesn’t keep works of art in his house. He prefers practical, useful things. If something isn’t useful to him “I just throw it out,” he says.

Just a casual chat in an art shop, right?

Not at all.

A few minutes later, she is taking this man on a drive through town. He just wants to observe, to meander, to travel with no destination. But she wants to take him somewhere — to a place of great importance to her.

The differences between these two strong personalities are obvious. Nevertheless, like a schoolgirl with a crush, she exclaims, “I cannot believe you are sitting in my car!”

Are they strangers? Old friends? Former lovers? Is this a seduction? The film is full of clues and suggestions.

For example, in the opening scene, the gallery owner shows up to hear the art critic read from his book. He argues that “originals” are no more valuable than “copies,” and that value is in the eye of the beholder.

And after he makes this speech, the movie teases us with all kinds of “originals” and copies.” Parents and children. Views and reflections. Paintings and copies.

Certified Copy is, in one sense, a two-hour mind game. The two lead characters carry on a film-length conversation that may remind you of Richard Linklater’s talk-heavy romances (Before Sunrise and Before Sunset). But the nature of their relationship is mysterious. The closer you look, the more mysterious it becomes.

In a pivotal scene, the man leaves the woman inside a café so that he can answer a call on his cell phone. The waitress strikes up a conversation with the woman, and it is clear that she thinks these two are married.

But wait — the gallery owner does not deny it. She speaks as if this man is her husband.

Perhaps she’s lying, just to avoid embarrassing the waitress for her mistake. Or, perhaps she’s fantasizing that this man is her husband because she likes him.

Watch closely. In the rest of the film, the two speak as if they are married, and as if that marriage is disintegrating. She wants it to work out. He wants to remain detached.

Are they each other’s “original” spouses? Or are they just stand-ins for two other people, role-playing in order to work through their own problems?

Watch the movie closely. Talk about these questions. Then watch it again.

Me? I don’t believe Kiarostami gives us a clear answer. I think there’s more evidence for one possibility than another, but I also know plenty of moviegoers who disagree with me.

But ultimately, I don’t need to answer the question. This movie isn’t really about “Are they or aren’t they married?” It’s about which reality we would prefer, and why. The movie puts us through vigorous intellectual exercises in order to expose our own priorities, personalities, and perspectives.

Are you more like the man, who likes to keep art — and women — at a distance, so he can “appreciate” them at no cost to himself? Or are you more like the woman, willing to get involved and pay the price of intimacy?

And this isn’t just about marriage.

The farther that this man and woman travel together, the more agitated — even despondent — he becomes. Weddings and churches make him anxious. We see him pause on the threshold of a bedroom in a hotel, as if he is terrified of intimacy with the woman who is now partially undressed. We also see him pause on the threshold of a church, a piece of bread in his hand, as if he is frightened of communion.

Should he put aside his pride, go inside, and become a part of something greater than himself? Or are these social conventions and religious rituals just the fading echoes of old-fashioned institutions? Do we romanticize marriage and faith out of sentimentality? Or are they relevant to us?

Faith. Art. Love. It’s all part of the same mysterious invitation. That invitation requires us to surrender control, make ourselves vulnerable, and pay a heavy price. But it also promises blessings that cannot come any other way.

I know which character has my sympathies.

Last week, Anne and I celebrated our fifteenth wedding anniversary. And we observed that marriage has been one of the costliest decisions of our lives. We also agreed that it has been one of the most rewarding decisions of our lives. Only faith has demanded more of us, and offered greater blessings.

The art critic is right: Beauty can be dangerous. You can keep your distance. Or you can look closer, and let it have its way with you.

No, this is not a movie review. It’s a love story. This is your invitation. I recommend you surrender.

Want to be the best? Want to be famous?

When my friend Mark was recounting his recent vacation in New Orleans, he talked about how it didn't take long for his wife — who has an incredibly powerful singing voice — to start thinking about moving there. No surprise there: New Orleans is one of those places that attracts great musicians.

But what he said next got lodged in my head and stayed there. Mark said, "It's not that she wants to be famous. It's that the music community in Seattle is so... insular. And she just wants to be recognized for who she is, to be with people who get it."

Wow. Who doesn't want that?

I just spent a weekend in Nashville with writers and readers, with people who will voluntarily sit still and appreciate a poetry reading, with people who find value in the work I do as a writer and teacher and critic. It felt so good, I didn't want to go to bed at night. I wanted to stay up and soak up that rare and wonderful sense of being seen for who I am and what I love.

But should that be enough? Shouldn't I want more? Shouldn't I want to become one of the best writers? Shouldn't I strive to win the biggest audience possible for my work?

Is that self-centered?

I sometimes feel guilty for the amount of self-promotion that I do in order to get my work in front of audiences. It makes me feel egocentric, arrogant, and false. Worse, I don't like the anxiety that comes with it, the way it inclines me to compare myself to others.

Given the chance, I'd like to ask my favorite writers how they manage their ambitions. I'd like to learn from them a healthy perspective on desire, ego, and self-promotion.

Here's the good news: The Chrysostom Society, a writers group I've been reading since I was in high school, has just just published a new volume full of insightful reflections and counsel for finding an admirable and meaningful balance "between hubris and self-abnegation."

Contributors include my fellow Seattle Pacific Universitiy alumnus Eugene Peterson; my current Seattle Pacific MFA in creative writing mentors Jeanne Murray Walker, Gina Ochsner, and Scott Cairns; and several more writers I dearly love: Erin McGraw, Luci Shaw, Emilie Griffin, Dain Trafton, Diane Glancy, and Bret Lott.

From the press release:

Nine members of The Chrysostom Society asked themselves what role ambition has played in their lives. The volume, Ambition, is the result: a collection of essays in which, with striking honesty, they muse on their own motivations and experiences of ambition. The book contains a fascinating spectrum of responses and cautions, ranging from Diane Glancy’s praise of ambition as a gift, to Eugene Peterson’s narrative about how busyness can become spiritually crippling. Along the way Dain Trafton ponders his family’s respect for ambition, on the one hand, and on the other, biblical condemnations of overweening pride. Erin McGraw argues that the extent to which ambition is good or bad depends upon the goal — the what for which one is ambitious. Jeanne Murray Walker wrestles with the ambivalences that accompany the gender-specific challenges of a woman with ambitions, while Gina Ochsner offers an entertaining appraisal of ambition’s insatiability. Luci Shaw recounts her ambivalence regarding her literary acknowledgment. And Emilie Griffin reflects on her own wrestling with the lure of “fame.” Finally, Bret Lott urges that wherever we are — having achieved our ambitions or still struggling for them, they should take a back seat to gratitude.

I've already been blessed by what I've read, and I'm going to spend a lot more time with this book in the coming years. I also plan to give copies for Christmas gifts. (Which, by the way... is coming.)

Copies of Ambition are available now through Image at http://imagejournal.org/

Load up on copies now, and your purchase will go to supporting The Chrysostom Society's efforts, so that they can go on writing work like this as they have for several decades.

Music for launch time

It's been a good week for a new blog launch.

The days are turning grey and rainy here in Seattle. This is the natural habitat of grunge, where long seasons of gloom can slowly wear us down into despondency. I find myself reaching for more propulsive music when I start the car in the morning, something that will burn like the sun through the fog and remind me to get up and go, to strive, to pursue dreams.

I want to hold on to the creative motivation that I felt among my fellow artists and dreamers at the Hutchmoot conference in Nashville last weekend. I want to build a rocket, aim high, and launch.

So I've been singing loudly in the car. And launching this new blog has put me in the mood to start building new worlds and writing new stories.

Help me out: What song does that for you?

What song — or music — stirs up a surge of ambition in you to write that novel, paint that picture, chase that new job, run that marathon?

What song — or music — stirs up a surge of ambition in you to write that novel, paint that picture, chase that new job, run that marathon?

Post your battery-charging theme song in the comments, and I'll collect the answers for an upcoming post.

Here are three to get the ball rolling.

The first is the song that traditionally closes the dance party at the end of The Glen Workshop, sending us all out into a new year of daring to be creative and make stuff.

Cheesy? You betcha. Motivating? Oh, yeah.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1k8craCGpgs

The second is... well... it speaks for itself. When I listen to it, I'm nine years old again, stirring up a storm of crayons and typewriter ribbons and scissors and glue and construction paper. I want to make stuff when I hear this song.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9g1YamC49Ik

And the third has a sting in its tail, if you're listening closely.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=C1huGMglPas

#AllTheFeels: A conversation with Inside Out imaginations

Joy. Fear. Anger. Sadness. Disgust.

#AllTheFeels shone onscreen at the June 4 sneak preview of Inside Out in downtown Seattle. And as the credits rolled — as the audience sleeve-swiped tears of joy and laughter and sadness — director Pete Docter and producer Jonas Rivera proceeded down the aisle like royalty, making their way to the front for a rock-star reception.

Generous with their time, Docter and Rivera turned their movie inside out, regaling us with surprising behind-the-scenes anecdotes about how the movie developed over five years, how it was written and rewritten, how they decided on their cast members, and how the cast responded to invitations to play particularly emotional characters.

Generous with their time, Docter and Rivera turned their movie inside out, regaling us with surprising behind-the-scenes anecdotes about how the movie developed over five years, how it was written and rewritten, how they decided on their cast members, and how the cast responded to invitations to play particularly emotional characters.

Mindy Kaling, for example — who agreed to play the scowling green nay-sayer called Disgust — shed tears when she read the plot description. "The fact that you guys are trying to make a movie that tells little girls that it’s hard to grow up and it’s okay to be sad about it," she said, "is really profound.”

"I told Pete, 'Write that down. That’s really good,'" said Rivera. And that, he said, is when he realized how meaningful this could be to daughters.

Docter confirmed something I'd suspected as I watched the film: that the color of Joy's hair was, for the animators, a meaningful, deliberate choice. Originally, he said, Joy had orange hair, not blue. “But something about her being the main character, and where we take her — we go all the way to Sadness, and then Joy cries — felt pretty profound to us. We wanted to visually explore that, so that she has the most dynamic range color-wise. We like that she has a little bit of sadness in her already. It seems like a nice symbolic link.”

Some characters' colors seemed like obvious choices: Sadness (blue), Disgust (green), Joy (sunshine yellow). One wasn't so easy. "We hope," Rivera said, "that forevermore purple is the color of fear.”

But the most shocking and memorable revelation for me — not just as a fan but as a writer — was that Docter started rewriting the story from scratch late in the process. Docter says:

The initial pairing with Joy was Fear. That was chosen because — I don’t know about you guys, but fear was an essential part of my junior high experience. It drove a lot of my decisions. We thought ‘There’s good entertainment there.’

It was about three years in. Imagine this! We’ve done all this research, with three years of work, and I’m sitting in Editorial going, 'This movie doesn’t work. I don’t know what this movie is supposed to add up to. Joy is supposed to pull herself together, go back to Headquarters, and do… what? I don’t know.'

So I’m walking around that weekend — it was Father’s Day — and I’m thinking 'I should just quit. I’m a failure. The other two movies are a fluke. What would I miss? I’d miss my house. I’d miss the studio. The thing I’d miss the most would be my friends. And then it sorta hit me… the people I feel the closest to are not only the people I’ve had good times with, but people I’ve been pissed off at and sad with. We’ve suffered the loss of close friends. I’ve been scared for them.' And I realized, ‘That’s the subject matter I’m dealing with here. Emotions are the keys to the most important things in our lives.’

And I rush back, I’m all sweaty, I call Jonas on the phone, and Ronny Del Carmen who’s a co-director, and we meet for drinks that evening. And I pitch this half-fevered idea of re-doing the whole story without Fear, and instead pairing Joy with Sadness. And I’m kind of expecting Jonas as producer to go 'Uhhhh...." But instead he lights up and everybody walks out of there on fire, ready to go. And when we pitched it to John [Lasseter] —which was a little scary because he’s expecting a screening and instead he’s got me waving my arms saying ‘It’s going to be great!’ — even in that situation, John and Edward were very supportive and realized that this was going to be a better film.

So we quickly retooled and redid the entire film. And that’s not the only time we did that. We made the film seven or eight times.

The audience might have stayed all night if their special guests had kept talking.

I know I would have. And so I leapt at the opportunity to meet with Docter and Rivera the next morning at a roundtable interview with two other film bloggers: Jeff Totey of Beliefnet and Tracy of Skewed'n'Reviewed. Here are some highlights of that conversation:

I know I would have. And so I leapt at the opportunity to meet with Docter and Rivera the next morning at a roundtable interview with two other film bloggers: Jeff Totey of Beliefnet and Tracy of Skewed'n'Reviewed. Here are some highlights of that conversation:

O: I was up all night thinking about it.

Docter: So were we. For five years.

Rivera: You get so close to it that you don't even know how to judge it. Three or four years in you're like... 'What are we doing?' Does this make any sense? Then you start seeing it come together, and it starts to feel right, and you come out into the world and put it on the road and people respond... it's just really rewarding.

Tracy: How was the concept of the film born?

Docter: It was born with the thought of emotions as characters. I knew that there had been movies that take place inside the human body. I was just doing a mind exercise: What would be fun to play with? And emotions seemed like right what animation does best: strong, opinionated, caricatured personalities. About that time my daughter was 11, and she was going through a big kind of change, as kids do from playing underground with dolls to being a little more quiet. and that change made me wonder what was going on inside her head. Maybe we could explore that a little bit.

Rivera: It was an easy thing for me to hook into as a parent. When he pitched it to me I thought this is a great opportunity for a movie: It's familiar but foreign at the same time. No one's seen these things, but have probably thought about anger and having dreams. It felt like a great opportunity visually and narratively.

O: I just watched Song of the Sea. I was thinking that this happens once in a while for entertainment. In Song of the Sea, we had emotions trapped in jars, and it was about releasing them. Is there something in the air right now? Why right now would it be a good time to talk with kids and parents about emotions? Is there something driving the subject right now that makes it especially urgent for you?

Rivera: It's an interesting question. Pete has talked about the point of origin, watching his 11-year-old grow up and change. My kids are younger. Just this morning my wife calls because she's on the road and she can't find the phone because our 9-year-old had it and lost it. Is there something in these kids being born into the iPhone generation, and it's all about connectivity, through some backfire it's almost seems [we're] more distant. I notice a craving, because of all that, more connection to our kids. It's a concern I have, that maybe we're overcompensating in some way to try to reconnect.

Rivera: It's an interesting question. Pete has talked about the point of origin, watching his 11-year-old grow up and change. My kids are younger. Just this morning my wife calls because she's on the road and she can't find the phone because our 9-year-old had it and lost it. Is there something in these kids being born into the iPhone generation, and it's all about connectivity, through some backfire it's almost seems [we're] more distant. I notice a craving, because of all that, more connection to our kids. It's a concern I have, that maybe we're overcompensating in some way to try to reconnect.

O: It's like the devices keep us from being in touch with ourselves.

Docter: Which is weird, because the iPhones are all about connectivity! People are obsessed with it. Even Mindy Kaling was saying that she can't imagine going somewhere alone because she wouldn't feel like it had really happened unless she was able to share it with people. And yet there's this weird distance that happens when I'm looking at this [He holds up his phone.] and now I'm disconnected from you guys.

Totey: [To Docter.] I understand that you're a Christian. [To Rivera.] I don't know what your faith background is.

Rivera: [amused] I'm a fairweather Catholic at best.

Totey: I'm curious. Does that have any conflict at all with what you do? I have no problem with any stuff at Pixar, but...

Docter: I always feel that the most effective stuff is when it's not too preachy. A lot of Christian folks have asked 'When are you going to make a real Christian film?' And I feel like... that's not really the way to go about it. I feel like... who I am comes out in the work. And what you believe comes out in your actions.

Totey: I appreciate what you're saying. I was just wondering if you've ever come up against the studio or somebody who wanted to go one way and you thought, 'I don't feel good about that.'

Docter: There are a lot of belief systems at work. But I feel like 'The Gospel of Pixar' is really about community. And all of the films are about someone who feels outside in some way and reconnecting with a group, and re-finding their family. And in a way, that's our story. I was a nerd. I didn't fit in with anybody in high school. I went for a long time without close friends. But then you get to a place called Pixar and everybody else can quote Chuck Jones cartoons and knows Peanuts comic strips. So the films reflect our own craving for closeness and community. So there's never been any problems with what you're talking about.

O: I've noticed some parallels in recent years with the way U2 gets treated in the press and the way Pixar gets treated. It's almost like you've become so successful that people are rooting for you to fail. They want to see legends go down. Have you felt pressure on the storytelling team, as there's more attention and higher expectations of your team? And at the same time, considering the change in chemistry there — with Brad Bird going off and doing his own thing, and Andrew Stanton going off and doing his own thing — I wonder how that's changing the process. Have you changed anything in your procedures? Have you learned lessons that has changed your approach to storytelling?

Docter: That's... a deep well.

Rivera: We have noticed.... This isn't to be defensive at all, but it has felt like some of the reviewers, for instance on Brave, will compare our films to our other films. They'll say, 'It's really great. But it's not as great as their others.' And I think, 'That's funny. I never see that in a Warner Brothers review.' 'That's a great Warner Brothers movie... not the best Warner Brothers movie.' We look at that and think, 'Well, that's a good thing. We have a brand, and there's an expectation. We'll take that.'

Rivera: We have noticed.... This isn't to be defensive at all, but it has felt like some of the reviewers, for instance on Brave, will compare our films to our other films. They'll say, 'It's really great. But it's not as great as their others.' And I think, 'That's funny. I never see that in a Warner Brothers review.' 'That's a great Warner Brothers movie... not the best Warner Brothers movie.' We look at that and think, 'Well, that's a good thing. We have a brand, and there's an expectation. We'll take that.'

We don't expect that everybody's going to like them all the same. But we don't put one out and say, 'Boy, I hope it's better than Up.' We don't even think 'Boy, I hope it makes more money.' We hope it makes enough money that they'll let us make another one. That's our real metric. I think it comes with the territory.

I'm guessing the boys in U2 would probably say something similar.

Other than stop... we can't do anything else other than keep making stuff.

Docter: We had such an unbelievable run from Toy Story through ... wherever you want to draw the line... of critical, audience, and monetary success. We just had, kind of, everything. And it wasn't easy. It makes you appreciate how special and unique that time is when it does work.

Rivera: And as far as it changing, it's always been changing. Bird...

Docter: Brad came in and that changed a lot of stuff... when he came in for The Incredibles.

Rivera: It was a nice shot in the arm. It felt like it was a different cadence. We still talk to those guys all the time. Brad came in and was important in the early days of this movie.

Docter: If you were going to write a book about it, I think there's probably three or so phases of featured film from the feeling of the early days from Toy Story and A Bug's Life, when it felt like it just people in a garage doing it for fun, and then it fell into more of a rhythm, and then things have gotten bigger. My point with all that is that it's changed several times over the course of the 25 years things have been going on.

Rivera: It hasn't changed in terms of how we develop things. There's still a great volley. We start off with the nugget of an idea. When we brought in Lasseter on this, it was just a very small idea — it was a big idea, but it wasn't developed more than a page. And he sat forward, like what we'd hope the audience would do — and that was enough for us to keep going. We'd put up rough reels and get Bird's and Andrew's notes. And that's how it was on A Bug's Life. Although this company has scaled up and it's enormous now — there's 1,200 people and there was 110 on Toy Story — I'm really proud of the fact (I think this comes from Ed Catmull and John and all of us that have grown up there) that it's retained that DNA of 'This is a director-driven studio.' We know more about the world, but we're just going to focus on what we do and do our best to keep going.

Listening Closer to Andrew Peterson

On Saturday, October 9, singer/songwriter Andrew Peterson celebrated the release of his new album The Burning Edge of Dawn with a joyous live show at Nashville’s Grace Community Church that featured a crowded stage of special guests. This was my first experience of a live Peterson hubbub, and judging from the high spirits in the audience and the exuberance of the man in the spotlight, it may have been one of the high points of his performance history.

So head over to Christ and Pop Culture, put on your headphones, and listen in on the conversation I had with Peterson the next day at at Nashville’s Church of the Redeemer, where the Hutchmoot arts conference attendees were still buzzing about the show from the night before.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dglY1cvFWUc

Looking Elsewhere: October 11, 2015

The Twitter highlight of the day began with film critic and author Alissa Wilkinson and ended with musician Johnny Simmons: October 11, 2015.

And speaking of Alissa Wilkinson, she's been collaborating with her accomplished colleagues Robert Joustra and Andy Crouch on a book I can't wait to open.

•

Steven Greydanus at Decent Films speculates that Avatar: The Last Airbender may be for his children what Star Wars has been for him: "a new and enthralling mythology about a young hero with a mysterious power slowly learning to channel that power to fight against a tyrannical empire."

•

Another Twitter highlight: Film producer Keith Calder started tossing out advice for filmmakers, and it was excellent.

•

Peter Chattaway at Filmchat gives us some more details about the Coen Brothers' new film Hail, Caesar!

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kMqeoW3XRa0

The Walk (2015): A Looking Closer Film Forum

Should I do it? Should I walk out onto the Robert Zemeckis tightrope between contemplative art and sensationalistic entertainment once again? Most of the time, I go tumbling into a void of clumsy storytelling, shallow philosophizing, and sentimentality. But once in a while, Zemeckis can deliver a charge of ambitious imagination. Let's see what my go-to critics are saying about The Walk.

Alissa Wilkinson at Christianity Today says:

The way this final act is shot is so viscerally thrilling (my heart was in my throat, even though I knew the story, and it took me a half hour to feel calm after it was over) that it’s worth excusing the film’s deficiencies. But it has them. To wit: it’s narrated by Petit, perched in the Statue of Liberty’s torch, and it’s a little hard to take Gordon-Levitt seriously with his French accent (though it’s not a bad one). Similarly, characters give a few too many Important Speeches About How Important This Dream Is, but it’s all in the rather maudlin vein of “follow your heart” and “follow your dream” and “do this beautiful thing” that could be transplanted into basically any movie.

...

The film seems more than a little insecure, unwilling to let you feel its awesomeness—it shouldn’t have been—and resorting to telling you, over and over, that this is a very inspirational story and you should be inspired by it and by beauty and dreams and the sky and did we mention beauty?

Ken Morefield at 1 More Film Blog:

The execution of the stunt makes for a fitting climax, but the film doesn’t appear to know what to make of the stunt–an introductory speech by Petit claims that he cannot explain why he did it, only show us how–so the film that precedes that climax too often feels like filler. Occasionally the story brushes up against an interesting detail, but whenever I wanted to learn or hear more, it rushed past potential human drama in order to get to…tepid movie cliches.

Matt Zoller Seitz at RogerEbert.com writes:

If only Zemeckis had faith in his filmmaking power! What "The Walk" is missing, unfortunately, is an ability to recognize when poetry and mystery are enough and should be left alone to breathe. Here is a movie about a man whose life was defined by a daring, unprecedented and now un-repeatable artistic feat ... and who achieved that feat by trusting in his training and bravery and will. But the script, credited to Zemeckis and Christopher Browne, begins diminishing his achievement immediately with tedious chatter, and can't stop doing it.

Ann Hornaday at The Washington Post says:

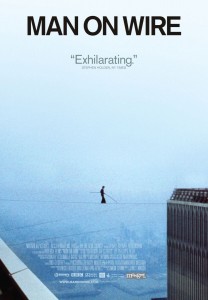

Filmgoers lucky enough to have seen James Marsh’s deeply moving 2008 documentary “Man On Wire” may see “The Walk” as that film’s shallower, less elegiac cousin.... Zemeckis has never favored subtlety, and he’s too prone to stridency and obviousness....

But A.O. Scott defends it in The New York Times:

There is always something new under the sun. To stop believing that — to mean it when we say we’ve seen everything — would be to give up on art and surrender to cynicism. “The Walk,” Robert Zemeckis’s painstaking and dazzling cinematic re-creation of Mr. Petit’s feat, stands in passionate opposition to that kind of thinking.

And Jaime Christley at Slant seems favorably inclined toward the film, even though she says that Zemeckis's

Spielbergian razzamatazz ... may test one's patience with its relentless pop and good cheer. But when the very first shot of the movie is a 3D extreme close-up of Joseph Gordon-Levitt shouting enthusiastically into the camera, you can't say Zemeckis doesn't put his cards on the table right from the start.

Since I have very little moviegoing time available right now, I'm knocking this down to a "Maybe" on my priority list. Man on Wire is one of my favorite documentaries, and I'm not sure I want to dilute my experience of that with the apparent mediocrity of this interpretation of the story. But I'll keep an open mind as more reviews and responses come in.

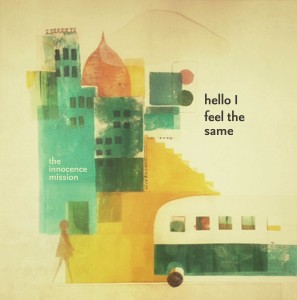

The Innocence Mission Returns

The Innocence Mission have a new record coming out this week: Hello I Feel the Same, from Korda Records.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=A9o_QuTNszY

To mark the occasion, I've rediscovered a conversation that I enjoyed with them way back in 2002, and that got lost as this blog moved from place to place. Maybe I'll set up a follow-up conversation soon.

Whatever the case, here are some of the things they shared with me more than a decade ago, as I was excited about their latest releases: Christ is My Hope and Small Planes.

Whatever the case, here are some of the things they shared with me more than a decade ago, as I was excited about their latest releases: Christ is My Hope and Small Planes.

•

Tolkien once said that the goal of fantasy should be "escape" first and foremost, and then "consolation" for the return to daily life. This is also an accurate description of what the Perises' music accomplishes.

I have long been a fan of the Innocence Mission. I find that when I listen to them I return as though having visited a sacred and liberating world, and my burdens have become lighter.

Since 1989's debut (which was simply titled The Innocence Mission), Don and Karen Peris and their band have offered a variety of pop unmatched by anyone in the crowded scene of contemporary music. Where ego is usually flaunted and celebrated, the Perises perform with hushed humility and grace. Where most artists bludgeon audiences with noise and sloganeering, the Innocence Mission offer a reverent, hushed collection of poetry. Don favors guitar work that glistens and glows over the searing, self-important roar. And Karen convinces you that every line of the lyrics comes from deep inside her, a confession, a question, or a story not to be taken lightly.

Their latest works, a collection of sacred music offered as a charity fund-raiser called Christ is my Hope, and a mainstream collection of previously-unreleased tracks and b-sides called Small Planes, are still available, either in stores or at their website: www.theinnocencemission.com

Their latest works, a collection of sacred music offered as a charity fund-raiser called Christ is my Hope, and a mainstream collection of previously-unreleased tracks and b-sides called Small Planes, are still available, either in stores or at their website: www.theinnocencemission.com

I had the privilege recently, as summer turned to autumn, of chatting with Don and Karen about the methods and the motives that set their work apart.

•

On Writing and the Creative Process

Overstreet: You've been putting out albums for more than a decade. Are you surprised to find yourself working on a new album in 2001?

Karen: I think that we would always write and record because we love making music, but we are surprised to still have an outlet and an audience for what we do.

Overstreet: What is the biggest challenge for you in the process of making an album. Lyrics? Music? Recording?

Karen: Lyrics are always the biggest challenge for me, to find words that will define the feeling given by the music, and that will feel right with the music.

Overstreet: Your lyrics seem to stand alone as excellent poetry. Do you read a lot of poetry?

Karen: I do love reading poetry. Gerard Manley Hopkins, Anna Ahkmatova, and Elizabeth Bishop are a few favorites. And reading through big poetry anthologies is wonderful, like glimpsing, or being carried into, so many small worlds.

Overstreet: What are you reading these days?

Overstreet: What are you reading these days?

Karen: I’ve just finished reading a book of letters between one of my favorite writers, William Maxwell, and his friend Sylvia Townsend Warner. It was really good to read something new of William Maxwell’s. He had passed away this last year. There were some beautiful, long, descriptive letters of his in the book, more like short stories.

Overstreet: There is a reverence and a quiet to your music that I have never encountered in any other band. Over the Rhine occasionally explores this territory, and artists like Cowboy Junkies, Sam Phillips, Neil Young, and Bob Dylan have done strong work in more subdued colors. But you seem most at home in songs that seem written for a chapel or a garden than for a rock arena. What draws you to this softer palette?

Don: Both of us like so many kinds of music. It may surprise you to know that in my car cd player right now are Larry Norman, Nick Drake, Led Zeppelin, David Gray, and Marvin Gaye. When it comes down to recording, though, arrangements need to suit the tone of the melody and lyrics.

Overstreet: Your style seemed to change dramatically after that first release on A&M release in 1989. Does the change in your sound reflect things you've learned along the way?

Don: I think that each cd is a reflection of where we are at that moment, and that includes a reaction, good or bad, to the previous cd. So, I feel we are always learning what to do, and what not to do. We have worked with some very good and interesting people along the way and have learned a great deal from them.

Overstreet: It seemed that, with Umbrella in 1991 you zeroed in on a signature sound, something you’ve polished and refined since then. You don’t seem prone to the sort of drastic reinventions that so many bands attempt with each recurring album. In fact, you seem almost to be retreating, drawing the listener to lean farther forward to hear subtleties and almost whispered confessions and reflections. Is this a conscious progression inward towards more contemplative work?

Overstreet: It seemed that, with Umbrella in 1991 you zeroed in on a signature sound, something you’ve polished and refined since then. You don’t seem prone to the sort of drastic reinventions that so many bands attempt with each recurring album. In fact, you seem almost to be retreating, drawing the listener to lean farther forward to hear subtleties and almost whispered confessions and reflections. Is this a conscious progression inward towards more contemplative work?

Karen: You know I often wish that I could be Brian Wilson or Phil Spector but so far that hasn’t happened. Some day if we could I’d like to make a really joyful album with a big sound. But we are also drawn to records that have a lot of space around the voice and the other instruments. And spare arrangements often seem to suit my voice and the song best.

On Marriage, Life, and Work

Overstreet: Marriages in which both partners are creative are often fraught with special difficulties-egos clash, visions differ. Yet the two of you seem to work together effortlessly, as natural as breathing. It is very hard to tell which song was Don’s, which was Karen’s. Is it more difficult than it looks? Are there certain disciplines or habits or things you’ve learned along the way that make working together as artists and as spouses easier and more fruitful?

Don: A genuine love for the result of the collaboration is important. Knowing that working together produces something finer, and more meaningful than working apart. Plus, being in love with the person you are creating with keeps things running smoothly and respectfully, keeps us behaving.

Karen: We disagree about whether or not to get a dishwasher, but rarely about music. We usually feel the same way about a song, though we each will be affected by it and add to it in our own ways. It is always so important to me that Don is affected by a song of mine. I always play it for him first. If he isn’t touched by it than I’m not as interested in going ahead with it.

Don: I would just like to clarify that I am for the dishwasher.

Overstreet: Don, what led to your solo project Ten Silver Slide Trombones? Were these songs somehow not right for the band, or perhaps more personal to you? Might we ever hear a Karen solo album?

Don: I had been writing and recording my own songs for years, mostly to play for Karen and a few friends. Their encouragement, especially Karen and our friend Denison Witmer, led me to think that I should pull them together into a cd.

Overstreet: How has parenthood affected the two of you creatively?

Don: We work at night mostly, after the children are asleep, so we spend a lot of time nodding off in the middle of takes, sentences. Parenthood has maybe made me more aware of the important need of getting things down right and accurately. Of writing about or playing only things that are moving in some way…

Overstreet: Do you find it challenging to balance the demands of daily life with the discipline of music?

Don: At times, sure, but I don’t think it any more difficult then balancing daily life with any other career or vocation.

Overstreet: Can you tell me about a time or a specific event in which you had a profound conviction that this was all worth doing? Maybe a moment when God gave you a glimpse of just how he can use your work in the world?

Karen: I can’t think of one single event. We get beautiful letters asking us to go on recording, and we are amazed by that. That these kind strangers are finding meaning in the songs or feeling connected with them, that is a real happiness for us.

Overstreet: Why do you suppose you became songwriters? Did your families encourage you to be musicians? Or was it an intuitive sort of call?

Karen: My brother Ric had a guitar and sang and he let me bang on it and make up little songs. My parents bought me my own guitar when I was ten. It has always been natural to sing melodies over chord changes, always a release and a happiness. With lyrics…I often feel tongue-tied in conversation, I listen much more than I talk and it often seems to me that I have a lot of trouble expressing my thoughts. So writing, though it can be a labor, is really satisfying, is a happiness.

Overstreet: What do you find is the best kind of support and encouragement you receive from your friends and your fellow songwriters?

Don: As Karen has said, the support from e-mails and letters are a great encouragement. I think that when people tell you that what you are doing has touched them, or that they appreciate it in some way really is a great kindness. Fortunately, we have some wonderful friends who do that and I hope that we in turn encourage them in what they do.

Overstreet: How does a typical song come together? Do you reach a moment when you know a song is finished? How do you measure when it is complete?

Karen: I’m not sure how to answer that except to say that a song just feels finished. If we are still moved in some way by a song by the time it is finished than we’ll put it on a record. A lot of times songs never make it to the recording stage. Usually when a song is brand new it will feel like the best thing I’ve been able to write and usually I will realize that I was very wrong about that and put the song away.

On Faith and Musicianship

Overstreet: I imagine that you have had an easier time with your music in relation to the church than many contemporary musicians because there is a lot of similarity in tone between your writing and a long tradition of sacred music. And your love of sacred music was clearly celebrated in Christ is my Hope. Have your experiences as artists within the church been positive? Do you find yourselves understood and welcomed there?

Don: Both of us grew up having the joy and privilege of being able to participate musically in liturgies, of seeing a worth placed on what we have to offer, of knowing that there can be a place for music in the reverence of worship. Both of us have had the pleasure of knowing good Sisters, nuns who encouraged in us a love of music, by their example of being musicians themselves, and of creating opportunities for us and others to be involved. There is an older man (88 years old) at our church here in Lancaster, who was the music director for many years, who has given so much to our parish and who deepened our love of traditional hymns. We dedicated the Christ Is My Hope cd to him. So, yes, our experiences have been positive.

Overstreet: Turning to your tours and experiences outside of a community of faith… how have mainstream audiences responded to your focus on such blatantly spiritual subjects and sentiments?

Don: You know… people that we have met everywhere along the way have almost always amazed us with their kindness, and goodness. We have always known audiences that are loving, welcoming, supporting, and responsive. It makes me miss touring. To see people, who are strangers, and to feel that instead they are friends.

Karen: Yeah, that is the amazing thing about touring. The feeling of community that happens with each audience.

Five More Questions

Overstreet: Tell us about someone who greatly encouraged or helped you in your artistic journey, and how they did it.

Karen: The two producers we worked with on our first three records, Larry Klein and Dennis Herring, took such care with each song and the way it was communicated. They inspired such excitement in all of us about the recording process.

Overstreet: Along the same lines, tell us about something that someone did that was a hindrance or a blow to your progress.

Don: Well, sure, all of us are faced with obstacles to progress at times. Where people have been the obstacle, I think these are best kept private.

Overstreet: What artist has affected you the most profoundly in your lifetime?

Don: Okay, this will prove to be really very sappy. For me, it has always been my wife, Karen. She writes and sings and creates in a way that makes me feel alive, that has always given me hope, that has given me glimpses of sadness and joy, and that always reminds me of the beauty and longing of life.

Overstreet: To the artist who is blocked, stuck, or struggling, what would you suggest for rejuvenating or renewing the creative impulse.

Karen: Listening to great music or reading great writing always makes me want to sing and play, to write something.

Overstreet: If you could go back and talk to yourself in the days just prior to your decision to pursue your craft seriously, what would you say to yourself? What advice, encouragement, information, or warnings would you offer?

Karen: I often wish we would have waited five more years or so before trying to get a record deal. I think that I, at least, was too young in some ways, my singing was too imitative, for one thing, when we made the first record. But it is easy to not be in a hurry in hindsight.

Man on Wire (2008) - a reflection

[This reflection on Man on Wire was originally published at Good Letters, the daily blog for Image, on October 21, 2008. I'm republishing it today to acknowledge the release of Robert Zemeckis's The Walk, and to encourage people not to let that film distract you from this excellent documentary. I might also add that it's my personal favorite of all of the reviews I've written, and since today's my birthday, I feel like sharing it again.]

•

In a photograph from her recent wedding, my friend Tara stands on one side of the empty dance floor. On the other, Bryan, her groom, leans forward in his chair. Tara is about to reach out her hand in a gesture of invitation. No doubt about it—he’s ready to respond. Their gazes are locked in a fierce line. The tension in that open space is palpable.

Complicated histories, differing citizenship, taxing responsibilities—these two have taken their chances, venturing out together in such a dangerous endeavor. And while their marriage is a joyous occasion, it was a challenge to reach that point. Fourteen years after a disastrous fall from my own first marital endeavor, I know the risks involved. So many things can disrupt our balance. Fear. Overconfidence. Carelessness.

Tara and Bryan are out on the wire. I’m thrilled and scared all at once, praying that the weather stays calm and that they step carefully.

I’m reminded of the 200 feet of cable across which Philippe Petit walked on August 7, 1974—a line strung between the Twin Towers of the World Trade Center. His was a dream just as ambitious, a dance just as dangerous.

•

We watch it play out in James Marsh’s documentary, Man on Wire. Historic photographs, home movie documentation, enthusiastic interview testimony, and arresting re-enactments draw us into Petit’s conspiracy. It was improbable, not to mention illegal. But as I doubted my eyes, I listened to Petit and his conspirators describe how they had achieved it.

The dream began before the towers were built, when Petit tore some Trade Center concept drawings out of a magazine. Later, his girlfriend Annie explained: “He couldn’t go on living if he didn’t try to conquer those towers...it was as if they had been built specifically for him.”

“Writing every book,” says Annie Dillard in The Writing Life, “the writer must solve two problems: Can it be done? and, Can I do it?” The same holds true for any worthwhile endeavor in artmaking. Re-enacting his early enthusiasm for that high-wire act, Petit says, “It’s impossible, that’s sure. So let’s start working.”

Petit and his conspirators proceeded with a strange and mysterious faith in each other, and in Petit’s abilities, believing they were called to something beautiful. We watch their home videos of hard work in a grassy field, pulling the wire taut so Petit can develop unfaltering concentration and balance. One of them later confesses that he persevered to the project’s fulfillment just because he wanted Petit to get through it alive.

How Petit’s crew went from practice to the actual performance—slipping through JFK airport with luggage full of shackles, ropes, knives, and even a bow and arrow—is difficult to imagine. The conspirators split into two teams, ascended the towers with cameras and forged ID cards, and escaped the security guards’ attention. So many things could have gone wrong—should have gone wrong. Their accounts of stringing the line defy comprehension.

And yet, for an hour that seemed endless, Petit danced on that strand, 110 stories above the street.

•

In her essay “The Stunt Pilot,” Annie Dillard describes the unexpected exhilaration she felt watching biplane pilot Dave Rahm defy gravity. She watched him “carve the air in forms that built wildly and musically on each other and never ended.... Rahm drew high above the world an inexhaustibly glorious line; it piled over our heads in loops and arabesques.”

In her essay “The Stunt Pilot,” Annie Dillard describes the unexpected exhilaration she felt watching biplane pilot Dave Rahm defy gravity. She watched him “carve the air in forms that built wildly and musically on each other and never ended.... Rahm drew high above the world an inexhaustibly glorious line; it piled over our heads in loops and arabesques.”

And then: “Like any fine artist, he controlled the tension of the audience’s longing.”

Recounting his experience more than thirty years after Petit's stunt, the acrobat's partner-in-crime, Jean Francois, thinks back to the moment when Petit put that second foot on the wire. His expression wracked with fears revived, Francois describes how the agony of the acrobat's ferocious concentration dissolved and, in the middle of the span, he relaxed and began to dance.

As one who fell, I’m moved by such daring and agility. The one who held my hand lost all of her faith in the grace that held us up. She jumped. We both fell. I might never have gathered the courage to try to climb the tower and try again without the examples of others who danced on so gracefully, and a new partner who sees what is possible, and why.

Two weeks ago, Anne and I celebrated our twelfth anniversary, and I find myself incapable of describing the measures of grace that have held us together suspended. But it’s still a frightening endeavor. There are certain wounds that time doesn’t heal, and they remind me of what’s at stake.

Recalling the indelible moments of Petit’s first walk across the void, Francois’ line of comprehension snaps in mid-sentence. Perhaps he suddenly glimpses the magnitude of the risks they took, or finally comprehends the wonder of their success. Perhaps Petit's magnificent dance seems even more transcendent now, as we have also seen how hateful concentration can bring down the very framework that made such acrobatics possible. I don’t know. I doubt that Francois does either. He runs out of words, out of wits, and covers his face with his trembling hands.

Maybe it has something to do with the longing we feel when we see something impossibly beautiful—a triumph over death.

•

I stare at that photograph from Tara’s wedding, the moment before the dance. I feel like Jean Francois, transfixed atop a tower, watching Petit in the hour of testing. I share my friends’ hopes for what might be possible, as they walk a line that’s anchored by faith and trust. I hold my breath, praying that they’ll concentrate, that they’ll be given the grace to dance with beauty.

Shouldn’t this be illegal, that these newlyweds risk so much, so far above a crowd of open-mouthed onlookers? Petit was arrested and subjected to a psychological evaluation. Me, I’m still shaking from the fall.

But even policemen gasped in joyous awe when they beheld the acrobat in the clouds. They watched him lie down in the sky, the crossbeam laid across his chest. He looked for all the world like a flourish of musical notation on a line, a grace note. With unquestioning faith in the fastness of his stage, he was free to reach out into open space, a casual gesture, almost lazy, his hand open to the sky like a question. Or an invitation.