One wild ride

So, I'm having one of those rare moments: I've discovered a movie that I have very strong feelings about. I can't wait to write about it. As the film progressed, my hopes soared — but so did my anxiety. It was either going to go very right, or very wrong.

I got so fired up as I was watching it, I started live-posting my comments, epiphanies, hopes, and worries. But that was for the Looking Closer Specialists, a closed Facebook group of this blog's biggest fans. I'm grateful for the Specialists — for their enthusiasm, friendship, and shows of support.

Eventually — probably before the end of the year — I'll post a review of what I watched tonight. But if you want to get on on the early conversations, think about signing on as a Specialist. Details here.

The Marty Party: Scorsese and Me

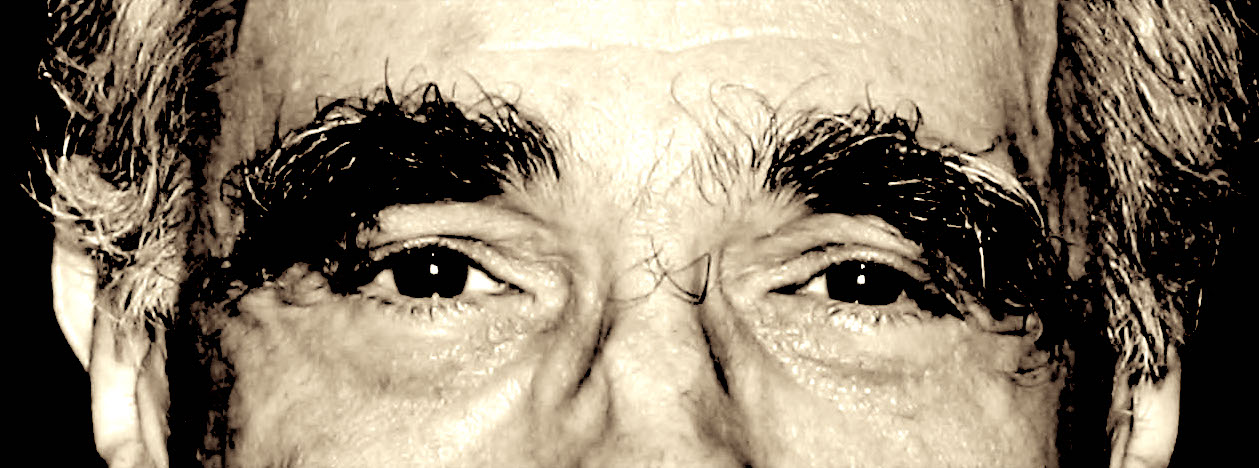

Today is the birthday of one of my favorite directors. I've seen almost all of his films — a long list — and I am tied up in knots with apprehension and anticipation about his upcoming adaptation of one of my favorite novels: Silence, by Shûsaku Endô.

So, as a nod of appreciation to the man who gave the world Taxi Driver, Raging Bull, After Hours, The Last Temptation of Christ, The Departed, The Wolf of Wall Street, and so many more, I'm linking to a few posts from the archives, and restoring a couple of reviews to the site that have long been buried.

I wrote my commentary on The Wolf of Wall Street in response to a blast of protests from Christian media voices about the film's explicit nature.

How is it that I never reviewed Hugo? Someday, I may have to rectify that.

I included Shutter Island in my round-up of comments about my favorite films of 2010 at Good Letters, the Image blog .

My review of The Departed was published here at the blog, but I also covered the response to the film from other Christian media voices in Christianity Today's Film Forum column.

My review of The Aviator was published here at the blog, and I turned in Film Forum coverage to Christianity Today.

When Gangs of New York opened, I covered it for Christianity Today in my Film Forum column. That is no longer available in their online archives, but I've restored it here.

Early in my film-reviewing, I posted a few words about The Age of Innocence. I just rediscovered those words in an ancient file, so I'm restoring them as well — here — although I feel some chagrin. Reading my early reviews is like revisiting papers I wrote in high school — I just shake my head and say "I'm glad I've learned a few things about writing since then."

I have never written a proper review of any Scorsese film that arrived earlier than The Age of Innocence. And I'm bothered by that because Casino (which I like better than GoodFellas — yes, I just said that), After Hours, and especially Taxi Driver are all near the top of my Scorsese list. (You'll find notes on Taxi Driver in my book Through a Screen Darkly.)

But there is no Scorsese film I have discussed with people more than The Last Temptation of Christ.

•

Oh, The Last Temptation of Christ. What a monster of a movie. For a Christian to admit any admiration of the film at all, I learned, was to invite condemnation from Christians who deemed it to be the work of the devil.

I have always meant to sit down and review this film properly. I should do that one of these days. The prospect is intimidating, but it's an important film in my own personal history of moviegoing, so I hope I will eventually give it the attention it deserves. For those who are curious, I'll say this...

I think the movie is a mess. Most of my complaints, though, are about technical aspects of the film, not its treatment of the Gospel. Scorsese's leniency on issues like New York accents here, for example, is bizarre and distracting. Some of the casting distracts me as well — I love Harvey Keitel, but I just can't take his Judas seriously, nor, for that matter, Harry Dean Stanton as Paul.

But what about all of those thorny theological issues with the film's portrayal of an insecure and doubtful Messiah?

Well, it's important to remember that Last Temptation is based on a novel. I grant the novelist Nikos Kazantzakis a lot of room to maneuver here because he declares, from the beginning, that this is not an attempt to represent the Jesus of history, but rather it is an experiment: a fictional investigation of questions that troubled him about the nature of humanity and divinity. Scorsese — admirably — includes the same disclaimer at the beginning of this film. So I look at Last Temptation as especially speculative and purposefully provocative in a way that I can respect.

Plus... Last Temptation was, for me, powerfully moving and meaningful when it arrived. It made me more capable of re-imagining Christ as a more human entity that I had imagined before. It made him seem more real to me. And I am very grateful for that. What's more — it was a provocation to a lot of fruitful discussion and debate among friends.

And then there's the added blessing of the music by Peter Gabriel, which, re-shaped into a complete and separate work called Passion, is the single most important album to me in my music collection.

I remember well the controversy at the time of its release. Somewhere in my files I still have a thick packet of pages published by Focus on the Family that described all of the evils they believed that Scorsese had committed with the film. (Many of them, I found upon watching the film, were false accusations.) And much of the controversy stemmed from a big misunderstanding: Many of the scenes that depict Jesus engaged in behaviors contrary to what the Bible describes are, in fact, scenes included in the part of the film that represents Jesus's last temptation! That is to say, they are part of a vision that the devil is placing in Jesus's mind, a life that he can choose as an alternative to dying on the cross. But Jesus rejects that life (spoiler!), and the film is true to the Biblical narrative in this respect: Jesus chooses suffering and death for the sake of sinners, rather than choosing to free himself for an easier path.

I would never hold Last Temptation up as a great portrait of Jesus. Rather, I would hold it up as a fascinating example of artists wrestling with theological questions by venturing uncertainly into imaginary scenarios. I think it's a rewarding experiment in exploring a mystery through make-believe.

I've learned to expect, even in Scorsese's least successful efforts, that I'm going to see something bold, unsettling, thought-provoking, and unforgettable. Whatever he does is filled with personal passion. And that keeps me coming back to watch his work again and again.

Gregory Wolfe Book Winners

Thanks to all who contributed their notes of appreciation for author and Image founder Gregory Wolfe.

Three contributors were selected as the winners of Wolfe's new book The Operation of Grace. I'll be contacting them personally to make sure that their prizes are mailed promptly.

Here are their testimonies about what Wolfe's work and writing has meant to them.

1.

Donald Powell:

The work of Gregory Wolfe has been a pearl of great price to me. At a spiritually fallow time in my life I discovered Image Journal and it was a lifeline of intelligent engagement with the culture, while never giving in to the spirit of the age. I had grown up as an evangelical Christian and one of the things that drove me from the fold (along with my own fierce appetites) was the rampant anti-intellectualism. When I returned to the practice of a faith, one of the main doorways that beckoned me inward was primarily aesthetic. The poets (Scott Cairns and Paul Mariani to name two) and artists I found in Image and Mr. Wolfe's own cogently argued and gracefully written essays were a special place of connection for me, a reminder that I did not walk alone, that I had fellow pilgrims on this improbable path and the best faith walks always combine heart and head, intellect and intuition.

2.

Andi Cumbo-Floyd:

I first came to know Greg Wolfe when I was fresh out of college in Pennsylvania and he advertised for an assistant editor at the new magazine Image. I applied and was granted an interview, but at the time, I wasn't ready for such important work — at least I realize that now. Still, I have followed Image from that day on, marveling at its ability to appreciate the depth, complexity, and darkness of art without compromising a commitment to profound faith. I don't see that richness of grace and glory often in the Christian world, and it's even rarer when it comes to art. So while I did not work for Image, it has been a constant companion in the past 20 years, and I credit the extraordinary compassion, vision, and passion of Greg Wolfe for that gift. Thank you, Mr. Wolfe. Thank you.

3.

Terry Glaspey, author of 75 Masterpieces Every Christian Should Know:

I have spent a number of years thinking and writing about the intersection of art and faith. Unfortunately, many of the books in this genre from a Christian perspective reflect an implied apology for creative work, especially if that creative work takes a modern approach, and not one based upon the strictest sort of realism. Although writers like Schaeffer and Rookmaaker were helpful in getting me to the table, I have found their worldview-based perspectives of art to be generally too narrow and polemic. What Greg’s books have done for me is help me think about art in a way that is more purely celebratory, more engaged with human experience, and more accepting of all life’s ambiguities and mysteries. His thinking has been so helpful in enriching and guiding my own. Along the way it has not just impacted my thinking, but has fed my soul with a rich dose of Christian humanism. For that I am so grateful.

HONORABLE MENTION

I should call out a runner-up entry from Martin Stillion, who writes:

It was close, but Greg Wolfe kicked my butt again in fantasy baseball. Next year, man, next year.

For that insight on the endeavors of Mr. Wolfe, Martin will receive a free "Beauty will save the world" sticker.

The Passion of Joan of Arc (1928): a Filmwell dialogue

[This dialogue was originally published in December 2012 at Filmwell by myself and the site's co-founder Michael Leary. We were working our way through conversations about the Top Ten films from a recent Sight & Sound Greatest Films poll.]

•

Leary: I have watched The Passion of Joan of Arc many times over the years, but since it has been a while I was looking forward to this one. I watch this film differently than I watch anything else. I spend the first half deciding whether I like it or not, but then it dawns on me that I am confused because there simply is no other film like this. And by that point, I am locked into the terror that eventually generates the chaos of the final complex of edits. I go through this exact process every time I watch it.

Overstreet: Yeah, if we’re talking about “processing” the movie, I can relate to your confusion. If we’re talking about the emotional ordeal of it, I can relate to the “terror” you mention.

I saw Joan for the first time just a year ago. But in preparation for our discussion, I watched it twice more. Perhaps it was the timing of that second viewing, but it was a sickening experience. It was the week before American re-elected the president, and every form of media was full of the clamor of accusation, bile, prejudice, presumption, insinuation, condemnation. Politicians, pundits, and voters alike were worked up into a froth and a frenzy. Few seem interested in learning or listening. Even an ideal candidate would have suffered despicable cruelty from fickle crowds.

So you can imagine how resonant this film seemed to me. I felt like I was watching more of the same… except the subject of all this scorn was a woman who, unlike compromising politicians, refused to tell the people what they wanted to hear.

Now, her martyrdom plays like a nightmare in the back of my skull. I close my eyes and I see flickering images of that poor, tormented woman turning, turning, turning, but finding no relief from the gallery of grotesque faces that leer, taunt, scorn, accuse, and condemn.

Leary: Yes. We had an interesting moment when trading emails one night in which we both independently decided that Joan of Arc is a horror film. This is one of those films that is always brought up in conversations about cinema and transcendence. And rightfully so, as it contains many of the formal elements that would later become evident in directors like Bresson, Bergman, and later Dreyer. But, at the same time, this is one of the most carnal films I can think of, in the sense that it is constructed entirely out of faces, grimaces, and minimal but emotionally charged physical movements.

And the end, of course, makes all the implicit brutality of the film very vivid and direct. Her torment in the flames and then the collapse of her body into Dreyer’s spare frame is sheer visual horror.

Overstreet: That scene… that scene! I’ve seen much more “realistic” depictions of people burning alive, but this one, which is almost impressionistic, is the hardest to watch. And it’s because the camera has given us such an intimate experience with the face now obscured by the flames.

I don’t know that I can say anything that hasn’t been said about Renée Maria Falconetti in the eight decades since she delivered this feverish performance. Falconetti’s genius is to make Joan a character who has been swept away from the shores of ordinary human understanding. Whatever she’s found has made her lost to the rest of us.

Can you think of any other performances of traumatic inspiration or madness as persuasive as this one? If my suspension of disbelief is ever disrupted, it’s because I’m worried about the actress herself. I’ve only experienced that on a few other occasions: Emily Watson in Breaking the Waves and Joaquin Phoenix in The Master, to name two.

Leary: Maybe Klaus Kinksi in Aguirre. Falconetti certainly calls into question the method cliché of actors like Christian Bale losing massive amounts of weight for a role, or Daniel Day Lewis talking to everyone for a year like Bill the Butcher. At some point, that process just becomes an attempt to remind me that I am watching something really real. Whereas here, the strength of Falconetti’s performance is the sense of endurance it requires.

•

Overstreet: Joan is not an endearing character, the way Falconetti plays her. We may pity her for the cruelty of her captors, but we will also pray to be spared any visions like hers. This Joan seems attentive to new senses that have awakened, so that she’s “seeing” and “hearing” another world, and only occasionally surfaces to discern the harsh details of her immediate surroundings. She’s like the seer played by Samantha Morton in Minority Report, her mind suspended in some kind of euphoria, her body suspended in a cold pool, occasionally trembling with visions of a hundred bloodthirsty Nosferatus as they skulk about and prepare to strike.

She makes it easy to see why human beings “blessed” by God with visitations and visions find themselves so frequently condemned to death or at least branded as insane.

Leary: Yes, I remember really struggling with Falconetti the first time I watched Joan. I just didn’t get it. I recall not being able to find some point of access that would unlock the oddity of her expressions. But I think you are on to something in accepting that she is always just beyond our reach, just beyond our drama translation skills because she is acting with a grammar that resists interpretation. I think it was Jonathan Rosenbaum that called this the pinnacle of silent cinema, and possibly the pinnacle of all cinema. Joan does call into question the ease with which we have accepted all the bells and whistles of post-talkie cinema.

I think one reason Joan remains on these lists is because at some point it becomes a transformational experience. Our senses are so bombarded by every small twitch in Falconetti’s gaze, the constantly shifting angles of Dreyer’s staging, and the drama of all these details. The silence vanishes. Learning to appreciate this film requires unlearning a lot of what we think is necessary in cinema. There is a neat little irony in the idea that the agony modern audiences feel while adapting to this silent film is reflective of Dreyer’s famously agonizing process.

•

Overstreet: There is never a moment in which I doubt that Dreyer is grieved by what he’s depicting. It all seems completely sincere. By contrast, his great-grandson Lars Von Trier — who seems intent on turning “Suffering Joans” into a genre — appears to enjoy devising ways for his heroines to suffer.

There isn’t a hint of irony in the whole thing. Nor is there any attempt to intellectualize Joan’s sufferings. The aggression of her accusers becomes a hallucinatory assault, the camera constantly shifting to draw us into Joan’s vertigo.

And the faces of these monsters… it hurts to look at them. Why don’t we see such extravagantly expressive faces like this on the big screen today? Among the accusers, I saw faces that were like the leering expressions of gargoyles inspired by a furious Robert Loggia and laughing Robert De Niro, and a priest who makes David Warner look gentle and kind.

When the accusers ask Joan about her age, one with a devil-horns hairdo twists one of those horns as if sharpening it and grins salaciously, as if sharing a dirty joke. It’s enough to make you fear some kind of gang rape is about to take place. What follows is just as merciless. Joan’s suggestion — that God is something we cannot define, and his power is something we cannot exploit — frightens these men who need to keep God, and women, so rigidly defined.

Leary: This is another element of horror in the film and brings us back to some of your first comments. The scandal in the film is one that involves the nature of revelation, authority, and power. The fact that this is a Church inquisition makes this even more harrowing in that the one institution from which a measure of grace and wisdom is expected is really a chamber of horrors. There are few exceptions in which these great men of authority aren’t pock-marked, self-important gargoyles.

The inquisition becomes merciless to the point of absurdity, but Dreyer doesn’t allow us to accept this as a simple indictment of the Church. When one looks closely at the set itself, we see a lot of exaggerated angles, doors and windows that don’t quite match up, and other architectural oddities that throw every frame out of whack. The set, which I believe is still intact, is itself a work of surrealist installation art. I think Dreyer sees his Joan in his avant-garde set as a challenge not just to the Church, but to modernity itself — to seduction by the Enlightenment idea that our patterns of power and authority are based on our ability to distinguish between what is real and what is not. This conceit, in which the modern Church is entirely complicit, always leads to cruelty.

Overstreet: That’s very helpful. His composition makes me claustrophobic, but I hadn’t thought about the implications of that. Your observation makes me of the decade I spent working in downtown Seattle, and how much more easily I became discouraged those days. I often suspected that it had to do with the vertiginous experience of being surrounded by so much architectural audacity, cut off from views of creation.

•

Leary: So having watched this a few times recently, what do you think about its place on the list?

Overstreet: It makes me suspicious that it should have placed higher. (I was pleased when it topped the Arts and Faith Top 100 Films list, which you and I helped create.)

I’m always trying to break the habit of “critic-speak.” It’s a language of grand declarations that no moviegoer has the right to make. Still, I’m tempted to say that there has never been, and never will be, a more terrifying film than this one. The trial proceeds as if it’s been scripted by Kafka. The verdict is so clearly predetermined that the questioning feels like a sort of revelry. The stakes could not be higher, but these jurors are playing at a sort of torture porn for each other.

To watch this movie is to suffocate with Joan even before the smoke begins to rise.

•

Invitation, not coercion

James P. Carse, from Finite and Infinite Games: A Vision of Life as Play and Possibility:

Storytellers do not convert their listeners; they do not move them into the territory of a superior truth. Ignoring the issue of truth and falsehood altogether, they offer only vision. Storytelling is therefore not combative; it does not succeed or fail. A story cannot be obeyed. Instead of placing one body of knowledge against another, storytellers invite us to return from knowledge to thinking, from a bounded way of looking to an horizonal way of seeing.

Thanks to artist Karen Renee for sharing this quote with me.

I might argue a bit with this: I think it's unfair to say that storytellers ignore truth and falsehood altogether. On the contrary, a good storyteller is proceeding by following what "rings true," by proceeding based on what emerges from all that has come before.

The great Flannery O'Connor sounds to me like she's talking about truth when she says,

The fact is that if the writer’s attention is on producing a work of art, a work that is good in itself, he is going to take great pains to control every excess, everything that does not contribute to this central meaning and design. He cannot indulge in sentimentality, in propagandizing, or in pornography and create a work of art, for all these things are excesses. They call attention to themselves and distract from the work as a whole.

But insofar as a good storyteller is not seeking to persuade, but remains attentive to what the narrative wants to reveal to her, then yes, I see a lot of truth in Carse's quotation.

Stories fail when storytellers allow our pre-conceived notions of truth to commandeer the story being revealed, when we become too eager to narrow the story into point-making or argument-delivery, and lose our proper posture as a receiver and a reflector rather than a teller or, worse, a weaponizer. In that sense, combative storytellers are poor storytellers. When we perceive the storytellers intent to convert, we see a ploy at work, and we are no longer an audience caught up in a story but a subject upon whom a manipulator is operating.

As Katherine Paterson once said in a Books and Culture interview:

Novelists write out of their deepest selves. Whatever is there in them comes out willy-nilly, and it is not a conscious act on their part. If I were to consciously say, ‘This book shall now be a Christian book,’ then the act would become conscious and not out of myself. It would either be a very peculiar thing to do — like saying, ‘I shall now be humble’ — or it would be simple propaganda....

Propaganda occurs when a writer is directly trying to persuade, and in that sense, propaganda is not bad. … But persuasion is not story, and when you try to make a story out of persuasion then you’ve done something wrong to the story. You’ve violated the essence of what a story is.

And then there's Dorothy Sayers, who in her essay "Dante and Charles Williams" recognizes that the truth of a story is beyond the grasp of the storyteller. The storyteller may perceive some of in the process of discovering and reflecting, but if it is a good story, there is always more to discover.

But it sometimes happens that it is not the poet himself, but another, who discovers the wider relevance [of the poet's work]. If so, he is justified in so interpreting it in the place where he finds it; for the relevance was always potentially there, and once seen and recognized it is actually there forever. This does not, of course, mean that we can read into poets anything that we jolly well like; any significance that contradicts the whole tenor of their work is obviously suspect. But it means that in a very real sense poets do sometimes write more greatly than they know; and it also means that every poet’s work enriches not only those to whom he transmits the tradition, but also all those from whom he himself derived it.

In this matter, I'll give the last word to the poet Scott Cairns, who said in an interview with Image:

I think writers with actual intentions generally end up saying things they already thought they knew, and I’m not much interested in reducing my vocation as a poet to something like propagandist. I write poems to find things out, not to communicate some previously ossified conclusion.

Birthday Party on Bald Mountain

75 years ago today, Disney's Fantasia — directed by Norman Ferguson — opened. It was the first of its kind in many ways, most notably in that it was the first film presented in stereophonic sound (a speaker was positioned, with others on either side of it).

And it remains the boldest, most ambitious animated feature that Disney has ever produced. What would it take to bring back that kind of vision to the most powerful animation studio in the world?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xHEMkbyXFxs

Hard to say, but Steven Greydanus has noted that one upcoming Disney movie seems to be subtly acknowledging Fantasia's influence.

And The Hollywood Reporter has reported that Disney is developing some kind of live-action adaptation of the "Night on Bald Mountain" sequence. Yikes.

To mark this anniversary, I'm linking to Greydanus's Decent Films review of Fantasia, where he writes,

If Fantasia failed to spark a hoped-for entertainment revolution, its achievement is all the more starkly singular. A joyous experiment in pure animation, an ambitious work of imaginative power, a showcase of cutting-edge technique, and a celebration of great music, it is without precedent and without rival. I’ve watched it far too many times to count, and I have yet to begin tiring of it.

He also noted Fantasia's debut on Netflix at Crux.

I also recommend Roger Ebert's write-up from 1990, in which he heralded the 50th anniversary release for its excellence.

And the D23 blog has "Fifteen Fascinating Facts About Fantasia" ... featuring some intriguing trivia about Bela Lugosi ... and Dopey.

Details, details...

James Wood in The Nearest Thing to Life:

...if the life of a story is in its excess, in its surplus, in the riot of things beyond order and form, then it can also be said that the life-surplus of a story lives in its details. For details represent those moments in a story where form is outlived, canceled, evaded. I think of details as nothing less than bits of life sticking out of the frieze of form, imploring us to touch them. Details are not, of course, just bits of life: they represent that magical fusion, wherein the maximum amount of literary artifice (the writer's genius for selection and imaginative creation) produces a simulacrum of the maximum amount of nonliterary or actual life, a process whereby artifice is then indeed converted into (fictional, which is to say new) life. Details are not lifelike but irreducible: things-in-themselves, what I would call lifeness itself. (38)

This quotation from Wood's extraordinary book addresses, in one potent paragraph, the big question I explored in a presentation I gave at The Glen Workshop in 2013 — "An Ecstasy of Particulars" — which was inspired by, and dedicated to, the late Robert Siegel, a dear friend and a great poet.

You can read Siegel's poem, which is a beautiful demonstration of what Wood is talking about, in the poem "Half a Second," which is available on page 169 of Within This Tree of Bones: New and Selected Poems, or in this Examiner feature (which includes an interview and many of Siegel's poems).

Anyway — Robert, if you're reading this from the Great Beyond, I think you'd like James Wood's book.

•

Has a small, specific point of detail in a painting or a film or a poem ever powerfully spoken to you?

You're invited to share them on the Looking Closer Facebook page.

For me, the list of such details would be endless.

But I immediately think of the sugar cube in Krzysztof Kieslowski's Three Colors: Blue. This moment gave me an intuitive understanding of what was happening — or what was threatening to happen — to the main character at that point of the story. It was about both the thrill in, and the fear of, filling so caught up in a flow of inspiration and emotional truth that a person nearly loses all sense of self altogether, dissolving into transcendence.

That's the power of finding just the right detail at just the right time on just the right canvas, so that it becomes what it is only there, in that point of relationship to everything else. Like a radiant, colorful agate on the beach, it is beautiful right there — but if it is pulled out of that moment, stolen away, claimed as "the meaning" of the moment, it loses its life and luster.

As William Carlos Williams once wrote, there are "No ideas but in things."

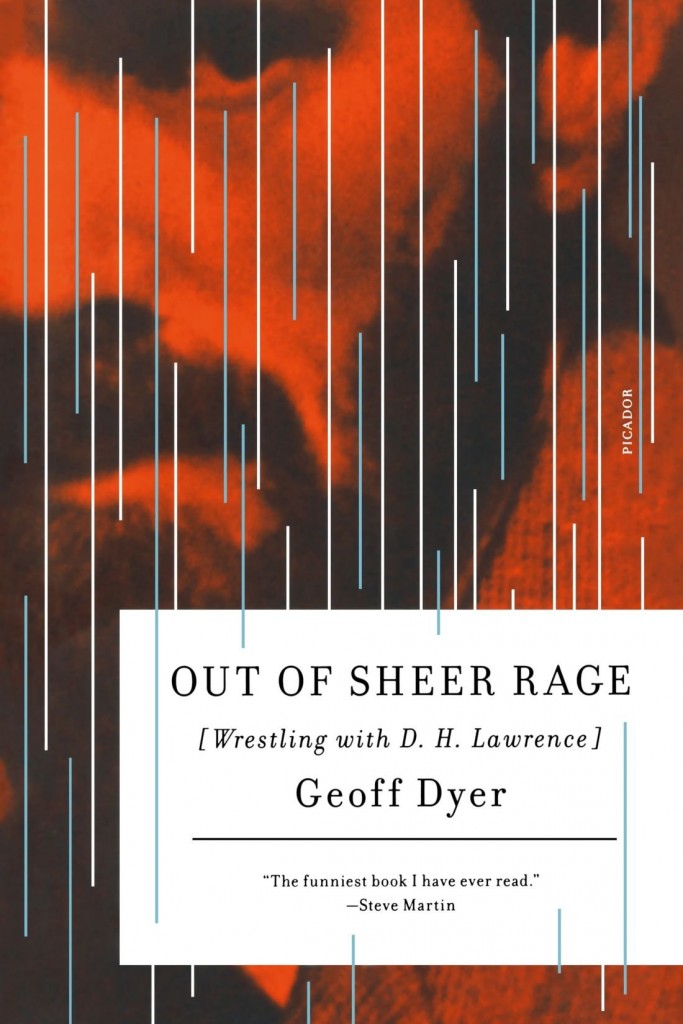

Needful thwarting

Geoff Dyer, Out of Sheer Rage:

The perfect life, the perfect lie, I realized after Christmas, is one which prevents you from doing that which you would ideally have done (painted, say, or written unpublishable poetry) but which, in fact, you have no wish to do. People need to feel that they have been thwarted by circumstances from pursuing the life which, had they led it, they would not have wanted; whereas the life they really want is precisely a compound of all those thwarting circumstances. It is a very elaborate, extremely simple procedure, arranging this web of self-deceit: contriving to convince yourself that you were prevented from doing what you wanted. Most people don’t want what they want: people want to be prevented, restricted. The hamster not only loves his cage, he’d be lost without it.

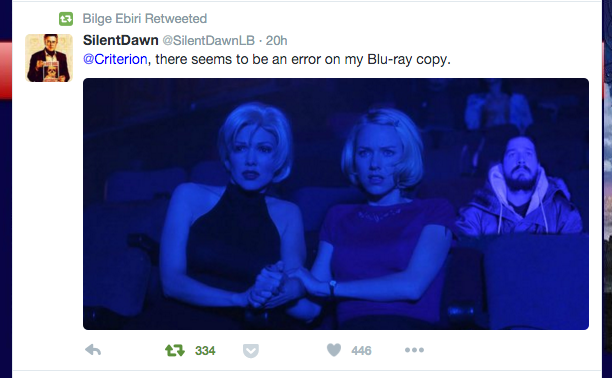

Looking Elsewhere: November 12, 2015

I love it when my friends are well published. But this is a rare occasion. Two of my favorite writers on film — one a recent graduate of Seattle Pacific University, the other a recent graduate of SPU's MFA in Creative Writing program — are featured in the new issue of Bright Wall/Dark Room.

Lauren Wilford gives an epic and insightful close read of Vertigo. The essay is now featured in its entirety at RogerEbert.com.

It involves a thought experiment. Wilford proposes that we

...experience "Vertigo" through the eyes of its female lead, Judy Barton. What was once a mystery becomes a horror film, a story of anxiety so profound that it approaches body horror.

In the same issue: Alissa Wilkinson on The Birds.

(But you'll have to buy the issue to get that.)

Congratulations, Lauren and Alissa!

Looking forward to the day you and your significant others all decide to move to Seattle.

•

The backlash against Starbucks' holiday cups is going too far.

•

Steven Greydanus, at Crux, writes:

Steven Greydanus, at Crux, writes:

In the cultural upheaval following the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, a wave of German historical films cast a critical eye back to Germany’s painful 20th-century history.

...

These new German historical films or “German heritage films” are typically accessible and popular in form, classically realistic in style, and moralistic in tone, inviting viewers to empathize with historical figures or characters in historical contexts in their individual choices to collaborate or to resist, and to contemplate what we would have done in that situation.

He goes on to compare and contrast two films about "faith, conscience, and state-sponsored evil": Sophie Scholl: The Final Days and The Ninth Gate.

•

For anyone who's been paying attention...

What to Read on Veterans Day: The Things They Carried

“Everything sparkled.”

That line from Tim O’Brien’s The Things We Carried would be sentimental and sugary in most contexts.

But in this masterful short story collection, it’s all we need to know about how, when the writer was drafted into the Vietnam War at a young age, he suddenly perceived his home. We get plenty of details: “The old chrome toaster, the telephone, the pink and white Formica on the kitchen counters. The room was full of bright sunshine.” But we know he means that he saw “everything” — far more than a bunch of appliances — with new appreciation in view of the hard news of his pending deployment.

O’Brien is a master of lines that draw us into states of mind, that stay with us, that continue to work on us. His work will reward the attention of any writer, like myself, who wants to learn from a master. It's a perfect Veterans Day text: a fusion of memoir and fiction that was a finalist for both the 1990 Pulitzer Prize and the National Book Critics Circle Award.

I could write an essay on O'Brien's long sentences, which are often rhythmic and melodic (and sometimes meaningfully repetitive), embodying moods and perspectives that burden soldiers’ experience — sensory impressions that come from living in an adrenalin rush; the surreality of the world to the war-trained eye; the vertiginous effects of trauma — before, during, and after a war. But it's the short sentences that stun me, that ring out at times like gunshots. As ordinary as they seem at first, I’ve come to believe that he is as careful about those as he is about the lines that apply pressure to them. He gives them a poet’s attention. They stick with me like a burr or a thorn. Sometimes, they’re explosive.

I could write an essay on O'Brien's long sentences, which are often rhythmic and melodic (and sometimes meaningfully repetitive), embodying moods and perspectives that burden soldiers’ experience — sensory impressions that come from living in an adrenalin rush; the surreality of the world to the war-trained eye; the vertiginous effects of trauma — before, during, and after a war. But it's the short sentences that stun me, that ring out at times like gunshots. As ordinary as they seem at first, I’ve come to believe that he is as careful about those as he is about the lines that apply pressure to them. He gives them a poet’s attention. They stick with me like a burr or a thorn. Sometimes, they’re explosive.

He’s well-aware of the power of sentence fragments. I won’t forget his description of a friend falling under sudden fire: “Boom. Down. Nothing else” (6). Regarding the turmoil he felt upon getting drafted, he says, “The emotions went from outrage to terror to bewilderment to guilt to sorrow and then back again to outrage. I felt a sickness inside of me. Real disease.” Those two words stick with me after that paragraph: “Real disease.”

Later, hiding at the home of a benevolent stranger just a short dash from the Canadian border, trying (but failing) to keep his plans to flee the draft secret, he spends a lot of words describing his enigmatic host. Then he says this: “The man was sharp — he didn’t miss much. Those razor eyes” (47). Those eyes stay with me. By not finishing the sentence, he makes us pause and imagine why those eyes impressed him, and to then complete that sentence our own way. The fragment implies its own question: Those eyes… what?

But it’s the short, complete sentences that work the most magic on me.

Testifying that war’s horrors teach soldiers to strike poses of irreverent callousness toward life (otherwise, how would they persevere?), he gives us this:

They were actors. When someone died, it wasn’t quite dying, because in a curious way it seemed scripted, and because they had their lines mostly memorized, irony mixed with tragedy, and because they called it by other names, as if to encyst and destroy the reality of death itself. They kicked corpses. (19).

The first short sentence is bold and intriguing. What follows is explanatory and insightful. But my takeaway from the paragraph is the concrete detail of the three-word sentence that follows. “They kicked corpses.” That I will remember. In the context, the implications of it are clear and even reasonable. But they still shock.

Recounting how his company would “play long, silent games” of checkers, he uses four short sentences that stand in stark contrast to the context in which the games were played: “You knew where you stood. You knew the score. … There was a winner and a loser. There were rules” (31).

After ugly flashback specifics of a summer job in which he hosed out the blood out of pig carcasses and then went home “smelling of pig,” he says — seemingly unnecessarily — “It wouldn’t go away” (41). He’ll go on to describe, in detail, just how deeply the stink of death had sunk into his skin and hair. But “It wouldn’t go away” resonates ominously: an echo bouncing back from all that is to come — what we already know will be a story of indelible war wounds. It wouldn’t go away: the reality of being drafted; the hardships of being a soldier; the terror and shame and damage of having witnessed war, having waged war, having survived.

Describing how he kept himself busy on the Canadian border, trying muster the strength to cross over and flee the draft, he writes,

On two or three afternoons, to pass some time, I helped Elroy get the place ready for winter, sweeping down the cabins and hauling in the boats, little chores that kept my body moving. The days were cool and bright. The nights were very dark. (48)

My mind seizes upon “The nights were very dark,” and connects it to the “silence” in the middle of the following sentence. There is a leak in this busy, well-lit picture, and it’s that bottomless pit of the dark night.

And the moment upon which that whole story turns? He writes,

The money lay on the table for the rest of the evening. It was still there when I went back to my cabin. In the morning, though, I found an envelope tacked to my door. Inside were the four fifties and a two-word note that said EMERGENCY FUND. (51)

We know what this means. But before it fully sinks in, he gives he next three words their own chilling line: “The man knew.”

Short sentences emphasize how close he came to absconding — their brevity reinforces how easily he could have stepped over. “I could’ve done it,” he says (54). He gives us a one-sentence paragraph: “I tried to will myself overboard” (56). Then, another: “I gripped the edge of the boat and leaned forward and thought, Now” (56). By breaking these into their own paragraphs, introducing more gaps and pauses, he slows the reader down, and he amplifies these tense moments of almost-ness, of indecision, of fate in the balance. Then, a two-sentence paragraph: “I did try. It just wasn’t possible” (57). By saying “I did try,” he sounds as if he feels compelled to confess his sins.

In “Enemies,” when one soldier beats up another, we have this descriptive sentence: “For a while it went back and forth, but Dave Jensen was much bigger and much stronger, and eventually he wrapped an arm around Strunk’s neck and pinned him down and kept hitting him on the nose.” Then he adds, “He hit him hard.” The reader has probably already guessed that. But stating the obvious only forces us to know what we might want to minimize. And then, even though he has noted that Jensen “kept hitting him,” he adds another short sentence: “And he didn’t stop.” That gets a capital and a period to make us feel how the fact made a strong impression. He’s repeating this fact about the hits because Jensen kept repeating the hits.

In the longest chapter of the book — “Sweetheart of the Song Tra Bong” — O’Brien crystallizes a horror story’s revelation with this: “Vietnam made her glow in the dark” (109). Then he does it again: “She was lost inside herself” (110).

This makes me want to go back to my novels — and my essays-in-progress — and to apply pressure to every sentence. To strive for diamonds. When I think of these soldiers, and all of the things they carried, detailed in long passages of inventory, I will remember this, and all that it implies — the hope and the heaviness — “They carried the sky” (14).

•

Page numbers reference the 20th anniversary hardcover edition of The Things They Carried, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2010.