First great rock band record of 2016

Put aside for a moment that the getaway-car rush of guitars in the song you’re about to hear sounds familiar; soon enough, I’m going to argue that the resemblance of Shearwater’s “Pale Kings” to another arena-rock anthem is appropriate, perhaps even deliberate. But let that go for now, and just catch these lyrics:

You know how sometimes

You’re so tired of the country

You could run to the ocean

And surrender your life…?

This song has my attention right now…because I do want to run to the ocean. I do want to get away from it all, escape the endless headlines of struggle and strife, wash all of the politics out of my head, listen to the wind and the waves and start again.

And yet…well, look at the rest of the verse:

But in the same breath

A light burns through your dreaming

And blows holes in the ceiling

Till there’s nothing but sky

I can relate to this experience—this careening between despair and hope, anguish and inspiration. And I know I’m not alone in this whiplash life, this season of extremes, when prayers and praises sung on Sunday morning give way to campaign-season panic on Monday:

Run out

Like a ribbon unreeling

Head down and careering

Colors drained from your life

But listen

Just the sound of your breathing

Blows the cover of silence

Blows the cover of lies

With incendiary light

In this song from Shearwater’s new album Jet Plane and Oxbow, there is a strong, unifying thread of uniquely American contradiction: There are stories of characters who hide away behind wires with their guns and their fears. There are ugly portraits of a nation full of “disconnected lives,” crippled by a “dimmed conscience,” guarding itself with “fences like knives,” and having a tendency to “piss on the world below.”

And yet hope keeps breaking through—a vision of a better world, streams of fresh air through pollution, rays of starlight through darkness:

You know how sometimes

You’re so tired of the country

Its poptones and its pale kings

And its fences like knives

But in the same breath

Your heart breaks with the feeling

With love and with grieving

For its irrational life…

Yeah, I do know.

And so it seems perfectly appropriate to me that this song rides the same kind of high-speed guitar riff as U2’s “Where the Streets Have No Name,” a song about how we keep on “building then burning down love”—and an appeal to that impulse that urges us to “reach out and touch the flame.”

[To continue reading this exploration of Shearwater's Jet Plane and Oxbow, and its U2-ish ambitions, read the whole article at Christ & Pop Culture.]

My Oscar predictions and preferences?

I try to avoid writing about the Oscars because, well, its track record speaks for itself.

When you look back on the last several years, do films like The Artist and Argo spring to mind as the movies that meant the most to you? Were The King's Speech and Crash the movies that illuminated the heights of cinema's powers?

Why do we treat this America-focused fiasco like its awards are actually meaningful on the subject of assessing artistic excellence, in view of the great feast of cinema offered around the world every year?

But I'll make an exception on Monday. I'll talk about the "Best Picture" nominees with some particularly insightful friends. The occasion will afford us an opportunity to discuss whether or not the films highlighted by this year's Academy actually have much meaningful to offer us.

And you're invited.

So... Monday could be just your first day of a long week. Or it could be the day you have dinner at Hales Ales Brewery & Pub in Seattle's Ballard neighborhood and listen to me join a Kindlings Muse discussion with Dr. Jeff Keuss, novelist Jennie Spohr, and musician Anna Miller.

It'll be a live podcast recording of our conversation about all of this year's Oscar Best Picture nominees and just how artful and meaningful they are.

I can guarantee you this: While we don't claim the be the last word on the year's greatest cinematic art, we will give you something more substantive about these films than the actual Oscar ceremony will.

Since we can't prevent the Oscars from happening... let's have a party and make something worthwhile out of the whole endeavor. Claim your seats here, so you can join us. Maybe you'll want to ask a question during the last part of the show when we open it to the audience. Maybe you just want to relax and watch something more interesting than a presidential campaign debate.

Or maybe you just want to wait and listen online when the podcast is posted at The Kindlings Muse. But... oh, I shouldn't forget to mention this... the burgers at Hales are the best I've had in Seattle.

Hail, Caesar! (2016)

A powerful man sitting behind a desk? Check.

A suitcase full of money? Check.

A night drive on a dark and winding road? Check.

High-speed banter à la Preston Sturges? You betcha.

Yes, indeed — Hail Caesar! is a movie by Joel and Ethan Coen. It has all of the defining characteristics.

In fact, it's more like a Coen Brothers film festival. As we follow Edward Mannix — the Catholic (and thus conscience-burdened) Capitol Pictures production "fixer" who is the wandering but binding thread of the story — through his daily routine of keeping feature films on schedule, on budget, and under control, we get a grand tour of the spectacularly realized movie sets, the genre conventions, and the pre-HUAC political paranoia of the 1950s.

And each soundstage comes with its own cast and crew, its own set of troubles and triumphs:

• the parlor-room cocktail drama Merrily We Danced, where director Laurence Laurentz (Ralph Fiennes) struggles to un-drawl his Texan lead actor, a dopey Hollywood heartthrob named Hobie Doyle (Alden Ehrenreich);

• an Esther Williams-style "aquamusical" in which the main mermaid is played by a snarling and scandal-prone starlet (Scarlett Johansson);

• a goofy Western with its standard-issue comic-relief drunkard;

• a South Pacific-style musical, in which dame-deprived sailors are turned loose in a song-and-dance number as frenzied in its footwork as it is flagrant in its euphemisms (I've now lost any remaining misgivings I had about Channing Tatum's movie star status — he's sensational); and, best of all,

• the titular Ben-Hur-style "Tale of the Christ," starring a sort of Charlton Heston/Clark Gable mash-up named Baird Whitlock (George Clooney, adding another memorable idiot to his impressive Coen Brothers collection).

These multiple personalities are the film's greatest achievement and its biggest problem at the same time: While Hail, Caesar! is never less than entertaining, the movie's constant mode-changing — each environment introducing new characters and backdrops and styles — results in a film that just doesn't hold together. This is one of those rare occasions where the Coens' aesthetics upstage their writing and unbalance their momentum.

The Coens have proven time and time again that they can weave wildly disparate scenarios together into an unlikely, coherent whole: Raising Arizona's H.I. McDonagh has such a strong voice and persona, never to be outdone by his co-stars, that he commands our attention and affection; O Brother, Where Art Thou? moves episodically through the familiar chapters of The Odyssey; The Hudsucker Proxy is unified by a glorious soundtrack and an enchanting magical realism; and in The Big Lebowski, well — the ever-abiding and loveably long-suffering Dude just ties the whole room together.

But Mannix (Josh Brolin), our beleaguered guide blundering through wonderland, is so stable, steady, and understated that it's hard to focus on him in the midst of so many bizarre, cartoonish co-stars. And it doesn't help that an intrusive narrator keeps taking us away from him to spend time with a long-winded secret society, tangents that dull the punch of the picture.

It isn't Brolin's fault that Mannix isn't a strong enough center point; this may be the most likable performance in his increasingly impressive career. (Who could have imagined that Brand of The Goonies would grow up to have enough range for such roles as Oliver Stone's George W. Bush, Paul Thomas Anderson's "Bigfoot" Bjornsen, and the Coens' lunk-headed Llewelyn in No Country for Old Men?) But we're so busy adapting to the movie's constant costume changes that it's hard to discern what is really at stake for him, besides the possibility of professional burnout. And it's hard develop much care for what becomes of him as he marches from soundstages to nightclubs to studio meetings.

I've already heard from enough Coen fans and film reviewers to know that the film is going to find a range of super-fans, nay-sayers, and everything in between. But speaking for myself, I found too many of the film's talky encounters to be straining for the kind of inspired chemistry that characterizes the best of the Coens' manic comedies. It succeeds only in fits and starts. But when it succeeds, it soars — as in Fiennes' dialogue tutorial (which, alas, was a focus of the trailers); the aforementioned "No Dames" dance number; a brilliantly unexpected tangent featuring Frances McDormand; and the action's outrageous climax at sea.

Still, a disappointing Coen Brothers comedy is (with the exception of The Ladykillers) still a much better time at the movies than almost anything else playing in theaters. The performances are reason enough to bring me back to buy another ticket — especially Ehrenreich's, who seems to have been produced by some kind of Coen Brothers Cast Member Algorithm; he's perfect for their dialect-heavy dialogue.

Perhaps the biggest disappointment for me was that Emily Beecham, who makes a strong impression in the one parlor-room scene she plays over and over again with Ehrenreich, doesn't have any more to do in the film. I want to see a whole film about her character. She looks so perfect in 1950s fashion that she'd be a knockout as the lead in a Lucille Ball biopic.

Having said all of that — and I'm being deliberately vague here to avoid spoilers, because the more you discover on your own the better time you'll have — I'm most interested in how the film explores tensions between Hollywood'$ bottom-line prioritie$, the idea that movies can do some real good for "the common man" (Remember Barton Fink?), and appeal of faith — in this case, the Gospel quite specifically.

[What follows could be described as vaguely spoiler-ish, but not really.]

I've already seen more than one reviewer treating Hail, Caesar! as if it is makes a mockery of Jesus along with those who make fools of themselves in claiming to following him. I couldn't disagree more.

While Hail, Caesar! finds plenty to satirize in religiosity — in the parlance of the pious, in the blondeness of Hollywood Jesus hair, in debates between religious leaders — the role of the faith itself remains untainted. Christianity is, after all, what keeps Mannix from crumbling under the pressure. The film is book-ended with the fixer's crises of conscience in a confessional booth, clutching his rosary and — for all of his professional indiscretions — yearning to be the man he was meant to be.

And, just as The Hudsucker Proxy's holy fool and The Big Lebowski's bathrobed Dude were both comical Christ figures exploited and persecuted along their almost-blameless way, so Hail, Caesar! hints that Mannix is, in this not-so-heavenly kingdom, the beloved son who must speak wisdom and bring order to an unholy rabble. He's even given a "last temptation" — a choice between suffering fools for the rest of his career or taking the relief of an "easy" job (working for Lockheed Martin on a project involving H-bombs, which causes him to shiver and murmur "Armageddon").

While Mannix may be the "redeemer" of botched motion pictures, the Messiah Himself has an even more surprising and meaningful role. The film's opening shot shows us Christ suffering on the cross for sinners, and nothing about it is meant for laughs... until the camera descends to a sinner's awkward confessions. That figure will return again, in the flesh and blood of a genuinely tortured extra, radiating glory that may occasionally bleed through the cracks in these hard-hearted Hollywood exteriors. Some will interpret this as a scene about the power of movies, not the power of the Gospel. But it works because it proves both: The Gospel is about revelation through incarnation, and cinema at its best — like any art form — finds human beings imitating that same act by practicing the mysteriously collaborative work of creativity.

This passion play provides, for a moment, an icon light bulb bright enough to expose the foolishness of human behavior and show these buffoons how to better themselves. Consider it a contemporary work by Pieter Bruegel the Elder. Whether they mean to or not, the Coens find in the Gospel a beacon that beckons everyone out of their self-absorption, their petty concerns, their troubles, and their banality. Even Baird Whitlock himself may, for one unwitting moment, believe the testimony that his character delivers at the foot of the cross. That the scene inevitably collapses into exposing human foolishness only serves to emphasize the mysterious singularity of that figure who remains just out of frame.

Whatever the case, I was moved by this unlikely moment.

As with the musical undercurrent of O Brother, Where Art Thou?, it is that surprising suggestion of the sacred in this spectacle that will bring me back to Hail, Caesar's uneven affair. I doubt it will ever be one of my favorite Coen films, but man oh man do I wish this film had been around when Matt Zoller Seitz invited me to discuss the theology of the Coen Brothers. This movie brings more to that subject than anything they've yet made.

And, as per usual, the strongest impulse I have upon seeing a new Coen Brothers movie is the desire to see another new Coen Brothers movie. What in the world will they think of next?

•

Share your impressions in the Comments below or on the Looking Closer Facebook page.

Turn It Up: Mavis Staples, PJ Harvey, and more

Due to the demands of recent deadlines, an annual writers retreat, and an illness, I've fallen behind on some things... including my music column "Listening Closer." But that will return next week with a focus on new music by Shearwater.

That doesn't mean I haven't been listening to great stuff.

Mavis Staples's EP Your Good Fortune was one of my favorite records of 2015. And here she comes already with another one: Livin' On a High Note.

You can read all about it in this revealing New Yorker article.

And here's a track from it.

Also on the "I Can't Wait" list... PJ Harvey's The Hope Six Demolition Project. Here's "The Wheel."

Thanks to my new friend and coworker Dusty Henry, music critic for The Seattle Weekly, who woke me up to some great music that I would have otherwise missed in 2015.

For those suffering Radiohead withdrawal, here's Aero Flynn: "Dk/Pi"...

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IUVybg8zlbQ

And here's Car Seat Headrest, another new sound for my headphones.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cApmjEbKQHk

Timbuktu (2015)

On Saturday night, I had the rare opportunity to do what I love to do.

I invited a room full of Christian writers and special guests to travel with me to a village on the southern edge of the Sahara Desert in West Africa. It's a perilous place: Islamic extremists — carrying out jihad against anyone who offends them, including their fellow Muslims — patrol the streets carrying machine guns and shouting out long lists of things that transgress their understanding of god's law. Women must wear socks and gloves. No one is allowed to play music or sing. Adultery carries a death sentence.

We were anxious and uncomfortable, to say the least. But we were there.

We were there by the transporting power of filmmaker Abderrahmane Sissako. In truth, we never actually left beautiful and rainy Whidbey Island, which lies between the Olympic Peninsula and Western Washington State. But as we watched Sissako's film Timbuktu, we had the enlightening opportunity to tour this village, visit a cattle farm, and observe clashes between the wise and the ignorant over how to interpret the Koran and honor God.

We were there by the transporting power of filmmaker Abderrahmane Sissako. In truth, we never actually left beautiful and rainy Whidbey Island, which lies between the Olympic Peninsula and Western Washington State. But as we watched Sissako's film Timbuktu, we had the enlightening opportunity to tour this village, visit a cattle farm, and observe clashes between the wise and the ignorant over how to interpret the Koran and honor God.

These Christian writers — Catholics and Protestants alike, members of The Chrysostom Society, including such accomplished writers as Luci Shaw, James Schaap, Harold Fickett, Jeanine Hathaway, and Matthew Dickerson — determined to wait until the next day to discuss the film, allowing this intensely affecting film to work on our minds and hearts before plunging into conversation. But on Sunday afternoon, we gathered in a circle for an hour to share impressions, reactions, and questions.

This is what I love to do with friends, with students, with artists: To gather before challenging art, look closely, contemplate, interpret, discuss, learn, and then carry our epiphanies with us back into our lives in such a way that they season our opinions, our behavior, and our priorities.

(And you can join the discussion too. Share your thoughts or questions regarding Timbuktu in the Comments below, or on the Looking Closer Facebook page here.)

Here are ten of the many things that the Chrysostom Society pondered and discussed after watching Timbuktu: images that moved us, characters who surprised us, moments of musical inspiration, unanswered questions.

The opening shot.

A gazelle is running. But there is no sound at all. Until...

In retrospect, why does this startling scene serve as such a meaningful opening?

The image of two men struggling to get out of a lake.

A bright swath of gold sunlight reflected off of water. Two silhouettes, two men moving in opposite directions. During this long shot, we hold our breath, for we know that we are watching a turning point in the history of this troubled community. The image stays with us. Why is it so effective?

The village imam.

This holy man bravely and boldly argues with the jihadis, demanding that they leave this place of prayer and worship. He stands up for women and their rights. He calls the whole concept of "jihad" into question, directing the militants to carry out jihad in their own hearts, rooting out immorality there before concerning themselves with the morality of others. How does this compare to Jesus' own teachings about morals and judgment? Consider... the issue of stoning will come up before the movie is over. What did Jesus say to those who gathered to stone a woman accused of adultery?

The women and their sufferings.

One woman is ordered to wear gloves even as she's preparing fish at the market. Another is arrested for singing. Another is arrested for adultery. A married woman is approached by a jihadi while her husband is away. A stranger asks a woman for her daughter's hand in marriage, and when he is refused, threatens to take her by force "in a bad way."

Do all of the Muslims agree on how they should be treated? What does that tell us about Islam?

That flamboyant woman with the rooster.

Is she a prostitute or a "day wife" for the extremists? Is she a witch, performing voodoo in order to manipulate the soldiers? She comes from Haiti, and she makes mysterious references to the events that brought her to this village. What is her role in the city? Why do the extremists respond to her the way that they do?

The video-production scene.

A young Muslim man is directed to make a speech in a video for the jihadis. He is reluctant, and lacks passion. He is supposed to condemn Western culture. He is expected to condemn rap music, saying he has chosen God over music. And yet, he is being filmed with digital cameras and spotlights. What are we to take from this scene?

The bouncing soccer ball.

Arguably the film's most beautiful sequence, a football game is captured with graceful cinematography, capturing the joy and imagination of the young men as they engage in spirited play. But the whole sequence is bittersweet, for they are pushing the limits of what their armed guardians will allow, and they can't even use a real ball. Meanwhile, the ball that has been confiscated goes bouncing through the village, and no one will step in to pick it up for fear of what condemnation might fall on them.

How the man brought before a judge responds during his trial.

Even though the circumstances of a violent encounter are ambiguous and complicated, a condemned man accepts his "fate" without struggle.

Why?

What does this suggest about concepts of justice within Islam?

Technology.

A child raises a cell phone to the sky. What does this repeated image mean to you?

That masked man...

Who is he — that character on a motorbike who frequently rides through the town? He remains masked. And in the film's nerve-wrackingly climactic conclusion, he plays an important role.

I brought Timbuktu to this group because I knew that they were unlikely to encounter the movie any other way. But I also knew that, being accomplished writers and artists, they are observant, attentive, and intuitive in their interpretations of what they see, hear, and read. I wanted to learn from them. I had already seen the movie, read about it extensively, and written about it. But I was able to see so much more through their questions and conversation.

How else would we have ended up having such a substantial discussion about our Muslim neighbors, those abroad and those here in America? None of us are likely to find ourselves in any of these villages any time soon — at least, not together, not in circumstances where we would be free to discuss the correlations between Muslim communities and Christian communities, the points of theological agreement and disagreement?

In the days after the screening, I received several thank you notes from the writers, which I wish I could forward directly to the filmmaker himself, since he was the one to make such a brave work of art..

One wrote, "Thanks so greatly for bringing the film along and talking so eloquently about it. It has to rank as one of the most difficult films I've ever seen, one I'll not forget soon — and therefore one of the finest. It was a joy to talk about it with you and the others."

Another said, "Thank you for introducing us to this film. Deeply disturbing and profoundly necessary."

And another asked for a list of recommendations of films set in Iran, Iraq, and other places where Islam is the primary faith. "That film will stay with me for the rest of my life," he said.

This was just one gathering, just one film, just one discussion. But it felt to me like my most important and rewarding film-related event of the year. It gave us practice in listening to, and learning to love, our neighbors. It helped us confront, wrestle with, and begin to overcome some of our misconceptions about those who believe differently than us.

And in this current political climate, when the two leading Republican candidates both promise to "carpetbomb" people like this "until the sand glows," Christians need to consider how such statements clash with Christ's call to love our enemies, to pray for those who persecute us, to seek justice, to love mercy, and to walk humbly with our God.

When we watch a movie like this, we are reminded that such people as these are not merely our neighbors — they are our family. We should be seeking reconciliation, not destruction. When we harden our hearts toward them, the behavior that results only increases their hatred toward us and their will to destroy us. The Gospel of forgiveness, peace, and reconciliation is the only answer that gives us hope.

Long, long ago, the sons of Abraham all worshipped the same God. But then, like three brothers born on the same mountain, they went their separate ways, had their separate journeys, and ended up with profoundly different perspectives on that mountain. Christians, Jews, and Muslims have very different ideas about God... but they all look back at the same mountain from different places.

They have different impressions of what kind of mountain it is, and what their responsibility is in relation to that.

But they look to the same mountain. We are family. And, as Christ taught us, we must love one another, tender-heartedly, forgiving each other. And if it costs us our lives, remember — Christ has overcome death. If we truly believe in him, then our enemies have no way to threaten us, because death has already been defeated, and we are safe in the inclusive and welcoming love of our God.

First Impressions of Timbuktu

Here are some notes I made at Letterboxd after my first viewing of Timbuktu.

I’m tempted to give it 5 stars, but I don’t like doing that after just one viewing. My enthusiasm may be compromised by the timeliness of this film. We need intimate portraits of those faithful to Islam, and those unfaithful to it. We need them right now. And here we have one. I’m grateful.

Does that mean it’s a masterpiece? This is my first experience with filmmaker Abderrahmane Sissako. I’m moved by the narrative, the performances, the patience, the complexity, and the beauty. But I’m not sure I see Sissako as a director who composes meaningful images so much as he is a storyteller who knows how to film a good story. I’d like to see more visual poetry on the screen. I need to think this over and read some more. I need more time.

But I’m confident in my sense of its greatness. My most reliable source of thoughtful film reviews, Steven Greydanus at Decent Films, agrees with me.

Here is what Timbuktu caused me to ponder:

When any religious law ceases to be a way of showing us that we all, falling short of righteousness, need God’s love and mercy…

When any religious law is bent to stifle the playful, free, and creative (and thus human) expression of love and worship…

When any religious law ceases to be a design that helps human beings support one another in equality and love…

When any religious law seeks to concentrate power in the hands of a few, instead of investing power in service of those who lack power…

When any religious law becomes a system that people can manipulate, exploit, and revise to their own advantage…

… then that law no longer has anything to do with God. (That is to say, with Love.) Unjust religious law, or good religious law that is manipulated and abused, divides instead of uniting, kills community instead of building it, diminishes the humanity of those in power, and makes saints out of the oppressed for what they suffer.

In this film, the aging Muslim leader who speaks knowledgeably about the desire for peace, pleading on behalf of those who suffer injustice, clearly has roots running deep into faith. Those who oppose him, quoting the same sacred texts, are clearly self-interested and narrow-minded. They cherry-pick verses that will support their cause, disregarding the fuller interpretation of the text.

This is a very specific film about specific cultures clashing in a specific time and place. But it looks so much like what happens in any religion or tradition — even the one in which I find the meaning and richness and joys of my life. I have seen behaviors like those of the violent extremists in this film among Christians. Christianity, like Islam, is always full of professing followers of Christ who ignore anything in Christ’s teaching and example that is inconvenient for their agenda. Many are prone to seizing the law that was given for human flourishing and then bending it to exalt and protect themselves. They forget that Christ presented himself as the fullest revelation of the law — and he did that by abdicating conventional forms of power, investing himself in service of the poor, the marginalized, the outcasts.

The fruit of the Spirit, the Bible says, are love, joy, peace, patience, kindness, goodness, faithfulness, gentleness, and self-control. Where we see these things cultivating one another, Love is alive. And God is Love. In that sense, we can see God at work in the Timbuktu narrative: He is there in the love a family, in the resistance to forces that divide, in the language of those who speak truth in love, in the joy of the music, in the grace of the children.

Thus, I must object to those who just throw up their hands and say “The world would be better off without religion.” Any signs, any vocabulary, any code — “secular” or “religious” (if you believe those things are exclusive, which I don’t) — can be distorted and subverted for evil purposes. Love is the question that must be posed to any belief to test its quality; and love is the answer that this question demands.

Timbuktu stands out among films about Islam and Islamic extremism by making everyone involved — traditionalist and extremist, irreligious and religious, loving families and arrogant tyrants — human, rather than caricatures. When an audience is persuaded of a character’s humanity, the audience will connect with that character — whatever their culture, class, or gender. We identify with humans who suffer and with humans who abuse power. Thus, in its human specificity, Timbuktu becomes more relatable, and less likely to be judged simplistically, than so many films about our age.

We all, wherever we live, whatever religion we claim or deny, find ourselves shaken by the same warring impulses: within religions, organizations, communities, families, marriages, and even within our individual hearts. Thus, I think Timbuktu is a great film for everybody — so long as it is watched attentively and discussed.

Once in a while...

I'm coming up on the tenth anniversaries of my first two published books.

The arrival of Auralia's Colors was a great thrill, a dream come true, a privilege — all the clichés. To see some of my work published and set out on tables in Barnes and Noble... I couldn't believe my eyes.

Nevertheless, I'm a little discouraged as that decade anniversary approaches. Publication inspired in me a belief and a hope that, by writing and publishing books, I might indeed find opportunity to do the work that college was supposed to prepare me for. I've always aimed to serve as a writer and a teacher: working with students eager to learn about creative writing or film studies or some other aspect of art, imagination, and faith. But five well-received books (one of which is has become a popular textbook at the school where I work) and 10 years later, those doors have still not opened. It's become pretty clear to me that academic degrees, not publications or experience, are the credentials that really matter to schools when it comes to persuading them that I might have something to offer. Here's a lesson, aspiring writers: A pile of books, many hundreds of articles, and 15 years of public speaking are apparently not much of a resumé if you're hoping to teach.

But other days, I feel differently.

I think of all the friends I've found among my readers. I wouldn't trade them for the fortune I would have made if my books had been best-sellers. I think of the cities, schools, and churches around the world I've been able to visit on invitations prompted by those books. My world might still be very small if it hadn't gone this way.

And every so often, something happens that tells me I need to revise my understanding of what it means to teach. Today, I received a note from a teacher in Ipswich, Massachusetts — a friend whom I had just seen last weekend at a writers retreat. She said:

Today in Intro to Creative Writing, I arrived a little jet-lagged, and I asked students to talk in pairs about the kind of writing they wish to emulate. Shakespeare, Robert Frost, Vonnegut, Tolkien, Shel Silverstein, Judith Viorst, Judy Blume. The seventh or eighth student said, "Jeffrey Overstreet." I asked which title. "The whole Auralia's Colors series, but especially [The Ale Boy's Feast]."

I said I'd just spent some time at a retreat with you, and she was almost undone. After class, she said, "I'm in love with the Ale Boy." I said, "Well, who wouldn't be?"

Now, I don't share this to boast. I suspect that many little-known writers (novelists, poets, bloggers) like myself occasionally get a note like this; it's probably very common. No... I share this for two other reasons:

First: To impress upon you that it can mean so much to a writer or an artist if you send them a little note about your appreciation of their work. This note from a friend made such a difference for my spirit that I'm compelled to pass it on: This week, I'm going to let some artists know what they mean to me. Those few lines on Facebook came to me like a shot of adrenalin, or a cure for what ails my spirits — a realization that the hardest work of my life may not be of any particular value to employers, but it was valuable to some readers here and there. It made a difference for someone somewhere, and even if I hadn't found out about it, that would still be the case. I want to give that gift of encouragement to the artists whose work most moves me.

Second: In today's publishing world, the publishers look to the authors to be self-advertisers, and I have not blogged about my four-volume series, The Auralia Thread, for a while. So, hear this: It's still out there! Auralia's Colors, Cyndere's Midnight, Raven's Ladder, and The Ale Boy's Feast are still a bargain at online bookstores. And they still carry my heart in their pages. Those novels and my memoir of dangerous moviegoing, Through a Screen Darkly, are the best fruit of born of my education.

And I hope they bring you some pleasure.

There. I've done my self-promoting duty.

I'm not going to go around claiming my books are "essential reading" or anything. When I read them now, I see that I still have a lot of room to grow as a writer. And I'm not going to spend my creative energies marketing myself — I spend close to 40 hours a week marketing a school for what its students and alumni do with their educations, and that's enough marketing for me.

But I know from the joy that I feel when I write and when I teach that, even if they don't earn me a paycheck, these are the things that God made me to do. Eric Liddell's famous line from Chariots of Fire — "When I run, I feel [God's] pleasure!" — comes to mind when I do what I do best. Even if I only get to do those things on my lunch hour or in my "spare time," I offer these things with enthusiasm to those who will receive them.

If you're at all intrigued... enjoy. If not, revisit one of your favorite books, albums, or movies... and then send the artist a note. It won't cost you anything but a minute. And it can make somebody's day.

It might even do better than that. Me, I feel more compelled than ever to write another story as soon as possible. Maybe I'll end up just giving it away. Why not? There are many more rewarding jobs out there than those that anybody gets hired to do.

Hateful Eight vs. Revenant

I've come to admire Evan Cogswell's perceptive reflections on film. He blogs over at Catholic Cinephile, participates in daily discussion at Arts & Faith, and is a generous Looking Closer Specialist. I'm grateful for his friendship, support, and insight.

Evan's recently he's made some intriguing comments about some of 2015's biggest big-screen events. When he mentioned that he was writing down some thoughts on why he thinks Quentin Tarantino's controversial new close-quarters epic The Hateful Eight is a more successful work of art than Alejandro Innaritu's The Revenant, I invited him to share those thoughts here, and he graciously accepted.

I had seen The Revenant the night before, and the more I thought about it, the more dissatisfied I became with Innaritu's decisions. (I posted some off-the-cuff notes at Letterboxd.) And I see here that Evan has some of the same reservations I did regarding the disconnect between the film's visual splendor and its narrative aspirations. But he's taken the time to develop his critique much more completely. (And he's way ahead of me on another point: He's seen The Hateful Eight.)

Here's Evan:

This year's award season has seen the release of two Westerns – both from fairly talented if flamboyant filmmakers, both set in the merciless winter, both about mankind's capacity for evil, both featuring remarkable cinematography, and both featuring deliberate and prominent religious references. Yet, for all these similarities between Alejandro G. Iñárritu's The Revenant and Quentin Tarantino's The Hateful Eight, I found the Tarantino film to be far more rewarding, thought provoking, and most importantly a successful piece of filmmaking. The simple reason for this is that The Hateful Eight accomplished exactly what it set out to, and The Revenant did not.

The first and most obvious point of comparison, and the one that gave me the idea for this essay, is the cinematography. Emmanuel Lubezki's work for The Revenant is undeniably beautiful, and the wide angle lenses he uses capture the vastness and beauty of the snow-covered plains and forests as well as the peace and beauty of the sunlight and water. To some extent Lubezki captures Hugh Glass' (DiCaprio) feeling of isolation, but that is undermined when the camera moves in for extreme close-ups while maintaining the wide angle lenses. It wastes the field of vision, and even more distractingly, Iñárritu chooses to have the actors breathe on the lens as if to remind us that the shoot took place on location, and it was really cold and really difficult.

Another point of distraction is that the frequent worm's-eye-view of trees is copied from the gorgeous work Lubezki did for Malick's The New World. Finally The Revenant's beautiful cinematography becomes monotonous, mostly because it starkly contrasts the dark, brutal nature of the story: a man mauled by a bear, then betrayed and left for dead, finds the will to survive so he can take vengeance on the man who murdered his son. That is simply not a beautiful story, and trying to portray it as such comes across like the creepy kid from American Beauty.

In stark contrast, The Hateful Eight is fully aware of the ugliness of its story, and the cinematography reflects that. Like Lubezki in The Revenant, cinematographer Robert Richardson opens with wide angle shots that reflect vast landscape, but the darker lighting overshadows the natural beauty. If my memory's correct, there's only one scene in The Hateful Eight in which the sun brightly illuminates the landscape, which is kept in sharp focus by the wide angle lenses Richardson uses for that scene, and it's arguably the most horrifying scene in the movie. However, that scene is the one where Tarantino's theme becomes abundantly clear: all of these characters are equally depraved and repellent, and their hatred for one another will lead to their demises.

As that hatred leads to acts of vengeance and brutality, Richardson shifts to longer lenses, which make the film seem more oppressive as the set and the characters close in on one another. This is especially clear when John Ruth "The Hangman" (Kurt Russell) boasts that he is bringing Daisy Domergue (Jennifer Jason Leigh) to hang, and he states that anyone who tries to stop him will be killed. Russell and Leigh stand in the middle of the haberdashery, the walls closing in upon them, and the other characters pushed out of the frame. They believe they are the center of the story, and their hatred leaves no room for anyone else. The next major scene with Russell and Leigh takes this to an even greater level, as a smaller area of the haberdashery takes up even more of the frame. If it's not clear from the story itself, the cinematography makes it blatant: the hatred on display is suffocating not only for the characters but the audience as well.

I do not mean to suggest that Lubezki's cinematography in The Revenant is bad; on the contrary, it displays tremendous skill. I do think it is badly misapplied to the story Iñárritu is trying to tell. Similarly, there is no denying both Iñárritu and Tarantino have much talent as directors. Even though neither of these films is my favorite of their work, both films clearly show someone who knows how to use a camera, has a distinctive visual flair, and works well with actors. However, both directors suffer from a similar immaturity and weakness: they cannot resist showing off. With Tarantino that showing off usually appears in his scripts, and with Iñárritu it appears in difficult, technically impressive, and distracting camera techniques.

For last year's Birdman, a film I liked immensely, Iñárritu crafted a script which played to his strengths as a filmmaker and mostly obscured his weaknesses. The Revenant's script is a conglomeration of ideas and themes about justice, revenge, divine providence, and survival which at times feels more like a list of ideas than an actual story. It neither works on its own, nor does it hide Iñárritu's flamboyant showing off. The aforementioned fogging of the camera is just one example.

Another example is the early battle scene which is shot mostly in one long take. As the camera follows the actors, the feeling is not one of excitement or dread for the characters, but a feeling of curiosity, wondering how Iñárritu managed to work all the special effects into that take without stopping to edit. The perpetual wide angles serve as a constant reminder that The Revenant was shot on location, which did not draw me into the story, but simply made me feel sorry for the actors due to the cold in which they obviously had to work.

As several reviews have already pointed out, Tarantino's immature penchant for blurring the line between disgust and pleasure is on display in The Hateful Eight, and there are some scenes where he is clearly using the adjective in the film's title to get away with showing some, well, hateful behavior which we really did not need to see. The scene shot in bright sunlight that I referenced above is the most glaring example, even if it explicitly drives home the theme of film. Another scene draws a blatant parallel between the racism of the past and today's Black Lives' Matter movement. It's a worthy point, but I don't disagree with those who argue Tarantino is using that as his excuse for throwing the n-word into the script every few sentences.

In spite of all that, the depravity on display does add to the movie's central point: racism, misogyny, and all other forms of hatred are destructive to society and to individuals. As those attitudes play out in multiple quests for vengeance, the depravity escalates to the horrific finale. Tarantino even reins in his normal aestheticized violence, replacing it with much nastier realistic violence. It may be unpleasant, but everything serves the story.

On the other hand, the story of The Revenant, while also about revenge and dehumanizing acts of violence does not progress naturally to its finale. We see many scenes which are meant to impress upon us the extreme lengths which DiCaprio went to for the sake of the movie, (which will almost definitely win him an overdue Oscar) but none that lead up to his final act. Without giving any spoilers, it's the type of act which Christian film critics often like to discuss and rave about, especially considering the reference he makes to God as being in control of life. However, it all comes completely out of left field, as if "ambiguously-motivated-quasi-spiritual-moment" was the last box Iñárritu felt compelled to check off.

The repetition of one line from earlier does not add continuity to DiCaprio's final act, especially considering the first utterance of that line was followed by a brutal act of violence which completely contradicts the supposed mercy which the line offers. When DiCaprio's character repeats the line, it does not come across as profound, but as a lazy paraphrase of Batman's final line to Ra's Al Ghul in Batman Begins.

The Hateful Eight also has religious references, which are better integrated into the film. The film opens with a shot of a wooden crucifix covered in snow, setting the stage for a movie in which all the characters think of themselves as their own saviors, and Tarantino returns to that idea and to the crucifix several times. The shots of the crucifix may have been tacked on, (I don't think they were) but when you add something at the beginning of the film and return to it, it influences everything we see after it. When you add something new at the end, it comes across as an afterthought to pander to a certain audience.

When I walked out of The Revenant, my first comment was, "It's like watching a talented director trip over himself. You can kind of see what he's attempting, but his desire to show off his talent is getting in his way." When I walked out of The Hateful Eight, my initial reaction was, "It contains some of Tarantino's trademark immaturity, but the vicious realism of the violence might make this his most conscientious film yet." After a few weeks of reflection, I think both those first impression were pretty accurate.

As I said, the stories of both films concern dehumanizing violence and acts of vengeance, but that vengeance is approached quite differently. Considering Tarantino's penchant for graphic violence, I admit that from a basic description of the plots, The Revenant sounds like it should be the more rewarding viewing experience. However, the integration of all elements in service of the story, for me, made The Hateful Eight far more worthwhile.

As one last example, consider the scores; the score for The Revenant is good music which creates atmosphere as it partially recalls native American indigenous music, but it's laid over the film without adding much to the characters or the story. Morricone's sinister contrabassoon theme is flawlessly integrated throughout The Hateful Eight, creating both mood and enhancing character development.

When I was doing my undergrad, I took a course in which six student composers each composed incidental music for one of the drama school's six plays during that school year. The first thing we learned for all composers, sound technicians, lighting designers, and anyone else who works behind the scenes was this rule: never, ever do anything that draws attention to itself and takes the audience's attention away from what's happening on stage. That rule also applies to film, and The Revenant breaks it repeatedly. The Hateful Eight does not.

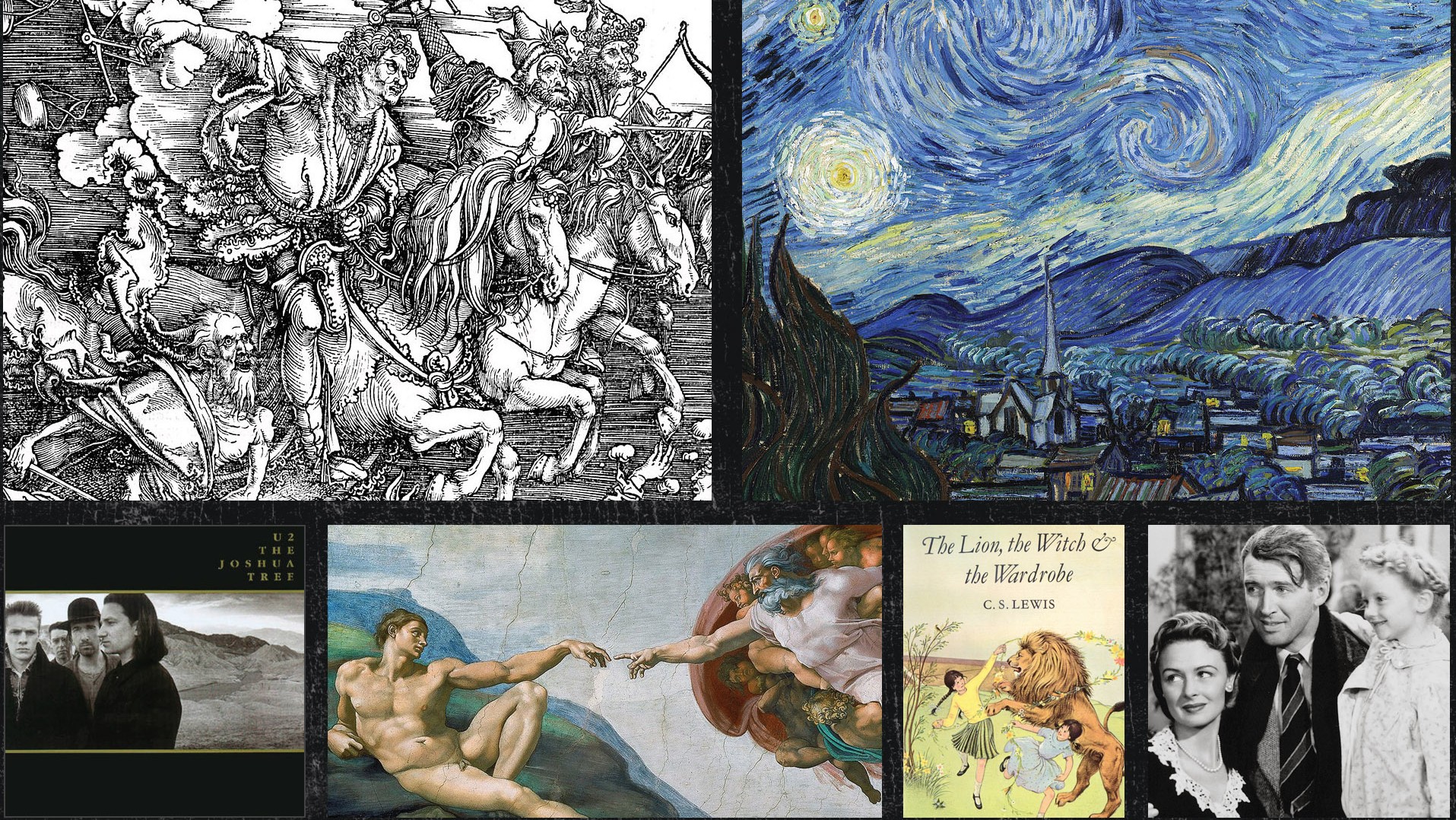

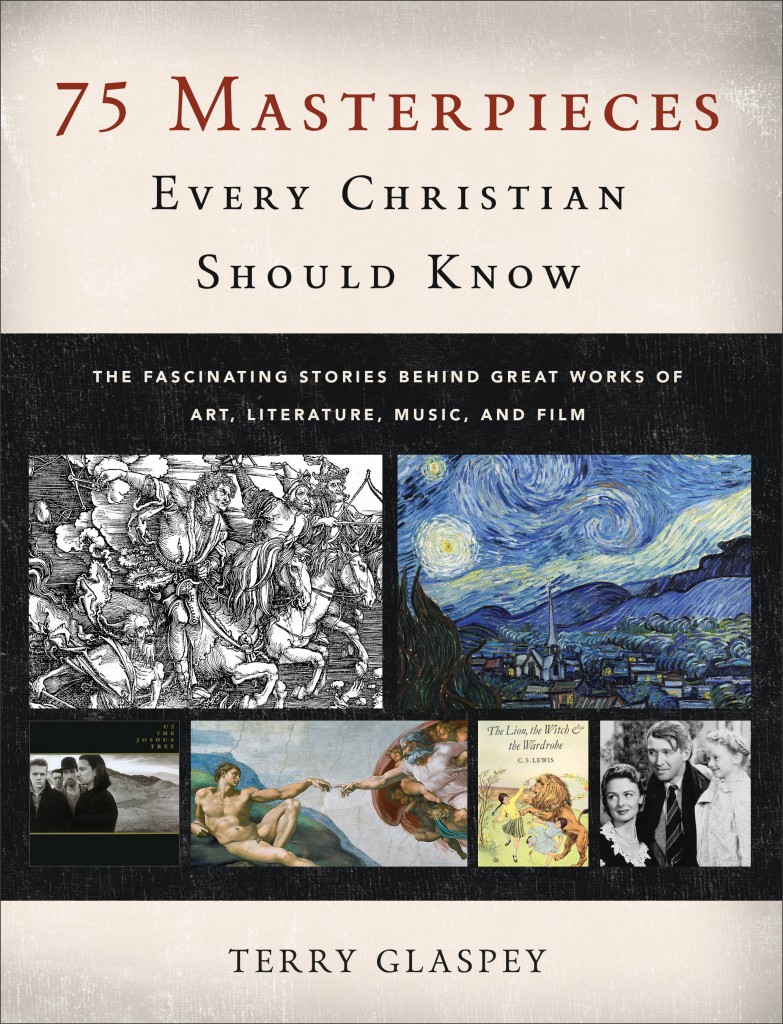

75 Masterpieces

This week has been one marred by the loss of masters — C.D. Wright, David Bowie, Alan Rickman — artists whose work will be meaningful for many generations to come.

We don't remember them for the originality of their "messages" or "themes" — although they explored questions and experiences that most of us can relate to. We remember them for how they did things. Contrary to so much of what I "learned" from the disposable quality of so-called "Christian art" when I was growing up, it is not the message of a work that makes the work great — it is the imagination within it. In fact, the more excellent the work, the more it invites us to explore a variety of questions and themes, never narrowing into something as conclusive as a "message." As Roger Ebert said (and I'm so fond of repeating), great art isn't about what the work is about — it's about how it is about it.

I am still learning to recognize and appreciate greatness in art, because the community in which I grew up was lacking in appreciation and curiosity about art. They liked to surround themselves with things that were comforting and familiar, and avoided great art because its poetic nature was "too difficult" (that is, it required contemplation and didn't spell things out for them); or they condemned it as "too dangerous" because it made them uncomfortable (when that discomfort was actually an invitation to mature and increase in understanding).

So I need knowledgable curators and tour guides, people who will teach me to see.

My friend Terry Glaspey is a fellow pilgrim in the wonderland of the arts. And his experiences have made him an inspiring tour guide. Terry has experience serving on the board of directors for The Society of Research and Education on Church History (SEARCH), and his book Not a Tame Lion was an ECPA Gold Medallion finalist. He is also the author of The Book Lover's Guide to Great Reading.

My friend Terry Glaspey is a fellow pilgrim in the wonderland of the arts. And his experiences have made him an inspiring tour guide. Terry has experience serving on the board of directors for The Society of Research and Education on Church History (SEARCH), and his book Not a Tame Lion was an ECPA Gold Medallion finalist. He is also the author of The Book Lover's Guide to Great Reading.

His new book 75 Masterpieces Every Christian Should Know is just what it claims to be: his carefully curated exhibition, his tour through art that has changed the world and made its mark on his imagination. The result is a beautiful book full of full-color reproductions and personal reflections.

I had the privilege of interviewing Terry about this impressive project. If you want to respond to any of his reflections, post something in the Comments below or over at the Looking Closer Facebook Page.

Overstreet:

I imagine you learned a lot in the research process. Which entries gave you the greatest sense of discovery and enthusiasm?

Glaspey:

There were so many fascinating discoveries I made along the way. Of course I knew a great deal about many of the artists, writers, and painters going into the project. But as I was trying to narrow my list (while at the same time as I was trying to expand the diversity it contained) I got a chance to find unexpected depth of faith commitment in a number of artists.

For example, though I had long admired her novels, I really didn’t understand the depth of Jane Austen’s faith until I began to read some biographies and discovered references to some prayers she had written for use in her family’s devotions. When I tracked them down I found the prayers to be not only beautiful (as would be expected), but also very confessional and heartfelt and self-revealing. In fact, when I discovered that these prayers were not widely known, I contracted with a publisher to print a small volume of her prayers, to which I added an introduction and biographical sketch. It has been published as The Prayers of Jane Austen.

Other discoveries, such as the stories behind James Tissot’s collection of paintings of nearly every event in the life of Jesus, the profound spirituality of the great African-American painter, Henry Ossawa Tanner, and the quirky delight of Howard Finster’s folk art were among my favorite new encounters.

One important caveat: I am suggesting that these are the 75 greatest masterpieces. Such an attempt would be foolishness. I am mostly trying to point to the amazing beauty, depth, and diversity of what has been created by Christian artists. These are not necessarily the greatest masterpieces, but each one is a masterpiece worth re-visiting.

Overstreet:

Did you feel that any of these works have gotten a bad rap with Christians, and needed something more than an introduction — maybe a defense?

Glaspey:

For the most part I avoided trying to build a defense for any of these works, though I did warn that some of them might take a bit more effort to fully access than others. I’ve gotten rather fatigued with the tendency of many Christians to narrowly accept or dismiss works based upon what is perceived to be the worldview behind them.

My essays on these pieces are unapologetically celebratory. I wanted to point people to art, music, literature, and film that was worth exploring and to give them a sense of how that creative person’s faith was integrated with what they created.

One thing that didn’t concern me was trying to prove that any of these creatives was a role model for Christian living. My emphasis is upon what they created and what they professed, no matter how imperfectly they might have lived out that confession.

Overstreet:

Did you find, when you started out, that you had a list much longer than 75, and had to narrow it down? Or did you have to build your way toward 75?

Glaspey:

Well, it was never a problem of finding enough masterpieces to include. The hard thing was to decide what had (sadly) to be left out. My general ground rules for inclusion in this particular project were that

1) the creator self-identified as a Christian. Some of them are Protestant, some Catholic, some Orthodox, and some rather unorthodox. Some, like Emily Dickinson, struggled between faith and doubt, but seemed to be people for whom faith ultimately got the upper hand!

2) I only included one piece by any one artist. It was very difficult in some cases to make that choice. You could have chosen other representative masterpieces for Rembrandt, Chesterton, El Greco, and others which would be just as good a choice. But I had to pick one, and my reasons sometimes had to do with the wonderful stories behind particular works.

3) The work needed to be a work that has been acclaimed outside of the Christian world. I was looking for works whose greatness was not due just to a message, but to the quality of their craft and the creativity of their vision.

I have actually, just for fun, created a second list of 75 more masterpieces, which maybe I’ll post on my website at some point. I want to explore some of them in the same way in the months and years to come. I’ve written a piece on the painter, Emily Carr, and have done extensive research on Arvo Part. I’d like to explore faith in the tradition of the blues, the connection between the theology of the Franciscan movement and a new realism in early Renaissance painters, and add another icon or two to the list. That is just the tip of the iceberg. So much worth exploring!

Overstreet:

Today, those films, books, albums, and paintings that tend to be labeled as "Christian art" are critically maligned. But these selections you've made seem to be appreciated across cultures and generations. Why do you think that is?

Glaspey:

The problem with much “Christian art” in our time is that it veers too close to being merely propaganda. Preaching has its place. But that place is in the pulpit, and not so much in creative expression. The best art is not primarily about delivering a message but in evoking the right kinds of questions from those who view or read it or listen to it.

Also, I think a lot of faith-based art is so concerned with driving home its message that it neglects to be realistic about the human condition and human motivations. It is either an imagining of what we might wish the world was like (the saccharine little villages of Thomas Kinkade, which are pretty as decorations but tell you almost nothing interesting about the real world) or the triumphal art that aims to show the superiority of Christianity over every other way of viewing the world (such as the bombastic preachments and uncharitable dismissal of all competing worldviews you’ll find in a movie like God is Not Dead). I’m not saying that someone might not get a bit of comfort from a Kinkade landscape or a bit of confidence from a Christian movie, but it isn’t going to offer the depth of insight that a great painting or a great film might.

We are too easily satisfied with fast food entertainment and diversion when there are gourmet meals of creativity available from the master chefs of the imagination. Nothing wrong with a little fast food, but I think our palates are enriched by better fare and our souls are more nourished by more complex fare. And much of the great art is a little more demanding—it demands closer attention, more thought, and even a little patient contemplation. The question is, are we willing to expend such effort?

My take is that if a creative person has labored long over their masterpiece, we should at least be willing to expend a little effort in trying to open ourselves up to it. Sometimes we’ll still walk away shaking our head. But sometimes, with just a little effort and patience, a work of art will open itself up to us and maybe make a last change in us.

Overstreet:

I recently saw a quotation of Emily Dickinson challenged by a Christian who pointed out that Dickinson's poetry reveals doubts about, and dissension with, Christian faith. That person responded saying that we should not waste time "slumming it in secular minds" when we have the beauty of the Scriptures available to us. You've included Emily Dickinson in this collection. How might you respond to that rather critical response? What are the rewards of meditating on the work of artists whose ideas about faith may not align with our own?

Glaspey:

What I love about Emily Dickinson, Graham Greene, and several others whose work is featured in my book, is that they are fellow-strugglers. They do not traffic in the much-too-easy triumphalism that is the limitation of many Christian artistic creations. They knew themselves too well to try to sugar coat their writings. They are honest about the struggle of believing and living out the demands of the life of faith. Sure, we need works that provoke celebration and worship, but we also need works that are honest about the dark night of the soul, about our doubts and struggles and our wrestling with God.

Frankly, the Scriptures are not at all hesitant about letting us see the struggles and failures of the great people of faith. As “people of the book” we know that the real human story is one of dogged pursuit of God while at the same time battling with our own sinfulness, failure, fear, confusion, and the complexity of our mixed motives. This is a world of darkness and evil, while at the same time a world of wonders--a world filled with what Bruce Cockburn has called “Rumors of Glory.” The best art reflects these tensions.

Overstreet:

There is such a wide variety of works represented here. Are there common ideas, though, that the collection as a whole might impress upon readers to help them discern the art that is worth meditating on from the art that might not be worth so much attention? Are there common ideas that come from this collection that might influence artists as they think about their own work?

Glaspey:

One of my deepest hopes for this book is that it will inspire today’s creatives. We have not only an amazing heritage, but also a tradition. Today’s artists, writers, musicians, and film makers can nourish themselves with the work of those who have gone before them and then bring forth their own unique take on that tradition. The tradition should inspire, not inhibit.

I remember hearing a live concert recording from Neil Young in which a frustrated audience member, who had evidently heard one too many long guitar solos for his taste, shouted out: “It all sounds the same.” Without missing a beat, Young responded, “It’s all the same song.” In a certain sense, all creative artists are playing variations on the message and the human experience that is part of the tradition to which they belong.

Overstreet:

If parents wanted to read through this with children, what selections would you highlight for their attention?

Glaspey:

If parents and teachers, homeschoolers and educators were to find the book useful for helping children explore the creative heritage of their faith, I would be a very happy author indeed. That was always in the back of my mind as one of the uses for the book. There is little in the book that could not be easily adapted for use with older children, but I might suggest starting with the chapters on Chartres Cathedral, Pilgrim’s Progress, Handel’s Messiah, “Amazing Grace,” George MacDonald, Van Gogh, Frank Capra, The Chronicles of Narnia, and Tolkien for starters. If there was sufficient interest I’d like to develop a little study guide that families or individuals might use to introduce these works and explore them more deeply on their own.

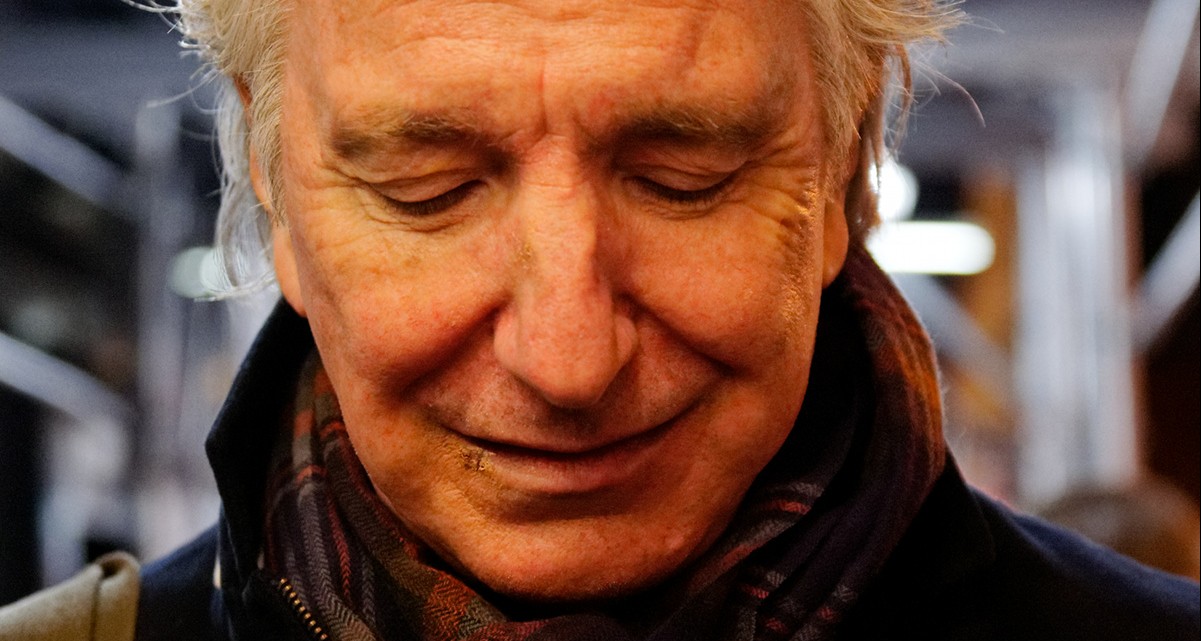

A great voice falls silent

Not to diminish his striking appearance: That noble nose, the formidable forehead, that subtle and bittersweet smile.

But it was the voice, wasn't it? Sonorous, authoritative, superior, and so easily spoofed (best by Bendedict Cumberbatch). That was Alan Rickman's signature. With him, even casual conversation sounded like poetry.

He seemed born to play theatrical villains who think of themselves as sophisticated and debonair.

And yet, for all of his beloved turns, it is his role as Colonel Brandon, who swoons over Kate Winslet's Marianne Dashwood, in Ang Lee's Sense and Sensibility, that I love most. He demonstrated phenomenal range there, deftly persuading us that a man of integrity, heart, and abiding love could move with authority through that world of pretense, hypocrisy, and greed. That was a rare appearance of a male character whose courage and greatness was displayed through love and fidelity rather than violence.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=clTG6sYtJig

Few actors find their perfect on-stage/on-camera counterpart. Rickman did: He seemed the perfect project partner for Emma Thompson; we should have seen them as co-leads in more romances. They were made to be together onscreen. If you haven't seen 2010's The Song of Lunch, which is about a turbulent reunion between former lovers at an Italian restaurant in Soho... you should. It may not be the greatest love story ever told, but the film is a symphony of Rickman's subtle facial expressions.

In fact... here's the whole thing for you.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=l3b_Jtwdoow

But even more impressive than his chemistry with Thompson... his 50-year relationship with "the love of his life," Rima Horton, the woman he married only a few months before we lost him.

Here was a celebrity who knew how to be a celebrity: By working — playing characters, directing films — with obvious love, and then by going home and having a good life off-camera without needing to get attention for himself. One of the reasons I admire him is that I know so little about him outside of what he made. May many others take note of dearly he was loved for his work, and how what we know of him now — his kindness, his generosity, his wit — we know now from those who worked with him, not from petty disputes, from corporate maneuvers, or from turning himself into a brand.

I had hoped to see a late-career victory lap of great performances from Rickman. He deserved more, and greater, roles than those he had. But he made every opportunity something unforgettable. Nothing was too ambitious, not even living up to fan expectations of Severus Snape in the Harry Potter films. And nothing... by Grabthar's hammer, nothing was too ridiculous for him. Not even this...

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KJ3_u3lxr7c

There was, will only ever be, one Alan Rickman.

May he rest in the peace and grace of God.

•

Feel free to post your own reflections or favorite moments in Comments below, or here: Looking Closer's Facebook page.

•

One more thing...

We must acknowledge that today the torch officially passes to Rickman's obvious onscreen heir, one who can speak with the same kind of authority... and who is well aware of the resemblance.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CnbN3Pya_AM

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xgxwLQsM0iM

2015's best films for a church basement film club?

Okay, the Golden Globes are over, and now we know that The Martian was the best comedy/musical of 2015. Because of course it was. Television told us so. This leads me to conclude that Mad Max: Fury Road isn't getting nearly enough appreciation for being a fantastic documentary.

Now for something completely different: What 2015 films would be the best to recommend to Christian audiences? What titles will challenge them, expand their understanding of how art can engage meaningful questions, and lead them into fruitful discussions? Maybe this is a good way to say it: If you were starting a "Looking Closer Movie Club" in your church basement, inviting adventurous viewers from your congregation, which films might be best to consider sharing with them?

The Arts & Faith Ecumenical Jury Awards for 2015 represents an interesting community of accomplished film critics that assembled to ponder these questions. I'm honored to have been a part of it. The result is a strange and surprising list of films... perhaps most surprising for what movie rose to the top. Follow the presentation of winners at Image. Here's Part One.