Welcome to the New Looking Closer Journal

Post Update (2012).

Well, here it is: The original post of the Looking Closer blog. You've found it. There are posts on this blog that have earlier publication dates, but that's because they were originally published on the Looking Closer website, which was a separate entity at the time. This was the post that launched the blog and opened up new avenues of writing for me. I've started the engines on a lot of journals and creative endeavors that died early deaths, but this one stayed alive and eventually flourished, thanks to the support of readers like you. And I'm so glad that so many of you have been companions on this long journey.

•

Welcome, Looking Closer readers!

Having despaired of my e-mail journalkeeping, something that never occurred more than once a month due to the struggles with America Online and its e-mail list limitations, I am taking a whole new approach to my casual note-taking.

I'm trying my hand at a blog.

This blog will be a place to let you know news bits, provide interesting links, and formulate early review thoughts on film, music, books, etc. While the Looking Closer site will continue to be the place where I publish finished reviews, this will be a place for more casual chat, whims, and fleeting thoughts.

I hope you find it to be a useful enhancement to the Web site. Frankly, I'm not so sure myself yet whether I will find it to be a comfortable fit or not. We'll see.

Jeffrey

Enemy at the Gates (2001)

[This review was first published at the original Looking Closer website in March 2001.]

-

Ready to test your imagination?

Picture Jude Law as a Russian shepherd-turned-sniper. Then imagine Ed Harris as a sinister German Nazi. Yeah, Enemy at the Gates, a new film by Jean-Jacques Annaud, asks you to suspend your disbelief with all of your might. We see several familiar Hollywood stars as characters of foreign origins, in an area of the battle where the U.S. never becomes a presence onscreen.

This is going to be a problem for some moviegoers — especially as the film makes its way around the world. But there's nothing quite so incongruous as, say, John Wayne as Genghis Khan. Fortunately, the actors are quite compelling. Bob Hoskins hams it up as Nikita Kruschev, and Joseph Fiennes plays a socialist political officer.

For the most part, the actors do little to convince us that they are anything but prominent British and American actors playing dress-up. They do not attempt strong accents. Their avoidance of "serious acting" conventions seems to emphasize that this is, indeed, a fiction, very loosely based on a true story. I actually like this choice. It helps me get over the strangeness early and focus on the "true story."

That true story, to the best I can gather, is that there was a shepherd in Russia named Vassili (Law) who became a sniper, and that sniper became something of a hero who inspired troops during the long and terrible battle for Stalingrad in 1942. Legend has it that the Nazis sent a special sniper named Konig (Harris) to specifically try and shoot down this famed farmboy gunner in order to dishearten the socialist forces.

The good news is that Annaud finds room in this story for some fantastic, suspenseful sequences. The bad news is that he shoves in a love triangle melodrama that feels forced and awkward.

In the opening scenes of the film, we are shown Kruschev's forces running to certain death into heavy Nazi activity. When they turn back, their own forces shoot them for being cowards. A political officer named Danilov (Fiennes) discovers Vassili's incredible skill during this gory, stomach-turning sequence. Later, when he stands among those being reprimanded for the losses, Danilov is challenged by Kruschev to come up with a plan to boost the spirits of the failing troops. "We need heroes," he insists, striving to provide an idea to encourage the men. "Do you know any heroes?" Kruschev asks. "I know one," he says. And so he begins to manufacture a mythos around Vassili and make him a hero.

Thus the movie seems to settle in on a question and a theme: What makes a hero? Secondarily, there is this question: Must a hero be perfect? Can he be flawed?

Danilov is taking advantage of Vassili's skill to forward his own reputation with Kruschev. He likes Vassili's skills, but considers this hotshot shepherd boy to be a lesser being because of his poor education. When a lovely young Jewish woman in fatigues (Rachel Weisz) shows up on the scene, both Danilov and Vassili are smitten. Danilov is determined to win her by emphasizing his higher intellectual status, but of course, it is Vassili's simple-minded determination and skill that wins her heart. He's the one who's exhibiting bravery, while Danilov hides behind selfish and egotistical excuses.

Meanwhile, Vassili's fame spurs Nazi retaliation — a sinister German sniper named Konig (Ed Harris) comes looking for him, and a battle of cleverness and precise shooting is under way. After Vassili gets advice from a seasoned veteran (Ron Perlman in an over-the-top, amusing performance), we watch him crawl through ruins, through pipelines, and under the mountains of dead bodies in search of an open shot. Annaud shows a real knack for hold-your-breath suspense here, enough to make me hope he will do more action-adventure in the future and leave soppy epics like Seven Years in Tibet behind.

It is also refreshing to see a war hero that isn't a cookie-cutter, flag-waving American crying "Freedom." Law plays Vassili as an uneducated, frightened, insecure human being who earns our respect by enduring difficult pressures, demonstrating patience and discipline, and doing what he can to provide an example of valor for his disillusioned countrymen. He isn't driven by personal revenge. He isn't some silhouetted icon of myth and legend. He does his job because he wants to be a responsible soldier.

And his opponent, Konig, is not just a cold, calculating cartoon, but a human with flaws and personal grief, striving to conceal his wounds. Watch how Harris portrays Konig in the inevitable final confrontation. It's not your typical showdown. It is a memorable moment between two human beings who know each other as well as they do their fellow soldiers, even though they have never met.

I am also impressed at how the film shows the redeeming qualities of Vassili without glorifying his Marxist ideology. Near the end, a key character suffers a breakdown of faith in his own philosophy, and thus, not having a defined political side to root for, we are left only with individuals, their choices, their instincts for what is right. Vassili is not a killer at heart, unlike the reptilian Konig who demonstrates a rather psychotic fascination with the science of his murderous work. Vassili fights because he must, and because he pities the people and the troops around him. After all, these miserable Russian soldiers face a death sentence if they don't fight and quite possibly another death sentence if they do. So Vassili, scared and almost beaten, gets up again and takes up his rifle to keep the dream alive, to fuel the rumors of his exaggerated hero status, to provide them with an inspiration, even as his own life is on the line. This is a complicated, unusual, and exciting hero.

In spite of these impressive aspects of the film, I cannot fail to mention its weaknesses, which are few but obvious. It borrows rather heavily from Saving Private Ryan in its opening sequence, although it does so with effective ambition. Again we are made to feel the vulnerability and panic in these poor soldiers.

But my biggest complaint with the film, as is often the case, is with its soundtrack, composed by James Horner. The film's main motif is almost a note-for-note copy of John Williams's theme for Schindler's List.

Horner has made a career of cut-and-pasting soundtracks from other composers, especially Williams. It first got on my nerves when his theme for Willow turned out to be a boiler-plate trumpet anthem like the Indiana Jones theme, and it peaked in last year's The Perfect Storm, where his music was so overbearing it actually spoiled the suspense of a rather amazing tempest at sea. A good soundtrack should subtly accent what is going on, like adding italics or underline to a sentence. Horner's approach sometimes suggests that the movie is not good enough, that the music must pound the audience into submission. While his Enemy at the Gates score is more restrained than The Perfect Storm, it is still borrowing power from a better movie to try and elevate something that really needs no help at all.

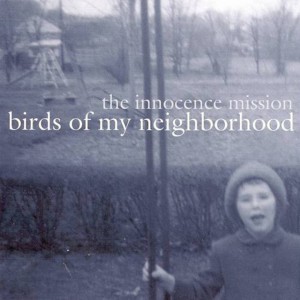

The Innocence Mission - Birds of My Neighborhood

April 2006 UPDATE:

The new re-mastered version of The Innocence Mission's Birds of My Neighborhood lets this masterful recording expand to fill a room, resonating in hardwood floors, giving the listener the freedom to move about in the spaces between Don Peris's exquisite guitar stylings and the fragile beauty of Karen Peris's vocals. It's the next best thing to having them visit you personally in your living room and play you a song... a dream I haven't given up on yet. I know, it sounds funny to dream of having one of your favorite bands visit your home, but hey... if music as glorious as The Innocence Mission's can exist and find audiences amid the clamor and buzz, then I'm inclined to believe in miracles.

These songs are as fresh and beautiful as the day they were recorded, more than five years ago. While Don and Karen have moved on from those days of deep darkness in which they crafted such palpable sounds of sadness and hope, their work continues to give voice to the wounds and wishes of people everywhere today. And rather than merely wallowing in angst, these songs are journeys that move us from a place of grief to a place of gratitude and grace.

•

This review was originally published at The Phantom Tollbooth in September 1999.

•

Imagine a girl and a boy sneaking into an empty cathedral, carrying guitars. They sit down beside some candles. The boy begins to play; the girl to sing in sweet ethereal tones the poetry of their personal praise to their Savior, the stories of their lives, the accounting of their trials...but all of this is done quietly, so as not to draw a crowd. That's the kind of thing you'll hear when you listen to the music of The Innocence Mission. Intimate, resonant... a timid sound in an enormous space.

Don Peris's instrumentation sounds sometimes more like the bells of a country church than an electric guitar. His interaction with his wife, vocalist and lyricist Karen Peris, speaks of a deep understanding of each others' artistic strengths, and the same goes for their longtime bassist Mike Bitts, who gives the songs backbone. While Steve Brown's percussion was well-suited to previous outings, his absence here does not hurt these quieter pieces.

When Karen Peris sings, the words may come straight from her diary, her most revealing meditations on the things she cares most about. But anyone can relate to the feelings and questions there, and find comfort in the answers that she herself finds sustaining and restoring. She's not preaching; in fact she may not even be aware of the audience at all. And her contemplations are so deeply rooted in life's most meaningful things--faith, love, humility, family, compassion--that no matter how unfamiliar the characters in the song or how cryptic the circumstances that inspired it, the imagery is intense and powerful, like what might have happened if Denise Levertov had written a song with Simon and Garfunkel.

Without sacrificing any of these qualities, the band turns over a new leaf with Birds of My Neighborhood. After their explorative debut album, which found them aspiring to be a radio-ready pop band a la 10,000 Maniacs, the Mission hit their stride with Umbrella, settling on a fusion of pop and folk that has only occasionally bent the ear of mainstream radio (with hits like "Bright as Yellow"). That sound has become their signature--crystalline, meditative--a simple combination of guitar, vocals, and percussion that owes something to Simon and Garfunkel's Sounds of Silence and Neil Young's Harvest. Umbrella focused on childhood memories and a growing understanding of faith. Glow was more ambitious, excerpts from a family history, with similar instrumental restraint that allowed some tracks like "Everything's Different Now" to soar to new heights of energy and enthusiasm.

Now, with Birds of My Neighborhood, there's a different thread…loss. It's like we've turned a page in the photo album to the darker side of life--breakups, despair, the loss of friends and the realizations that the good old days are over.

Friends have moved away.

One tree has come down, another one flowers and sways.

Miri was lost for five days.

From upstate at school one friend writes

Everything is changing while the day sky stays blue.

Changing around him, and me without you.

Appropriately, the music is more audaciously sparse than ever, as though nothing can rise above a whisper when speaking of such things. As in Bob Dylan's Time Out of Mind, we hear echoes of the past haunting the singer. Even "Follow Me," the band's first cover also included on a John Denver tribute collection, seems edged with sadness, perhaps alluding to the tragic death of the songwriter himself. (Indeed, the song preceding it makes reference to a man who flew "away in spring in a light blue and silver plane" and "now the snow has covered everything.")

The simplicity and concentration of these poems might have been merely mournful in the hands of any other songwriters, but somehow Karen Peris can find hope and strength without sugarcoating the sadness and discouragement. She reminds the recurring, mocking figure of the "laughing man" that, just as faith can move mountains, she can find a way to row through the icy waters of "The Lakes of Canada." In "I Haven't Seen This Day," every morning seems a new world of possibility in spite of recent trials:

Oh mourning dove, we'll go up to my roof.

Oh mourning dove, we'll go into the sky.

This day is filling up my room,

is coming through my door.

Oh I have not seen this day before.

In "July," perhaps Karen Peris's most sublime lyrics of all, she tells us of a season of drought where "we both wake up so dry/that no more tears can leave us." Such intense hardship is a new country for the Innocence Mission, but even at midnight the day begins.

Our friend came in

out of nowhere, with lit

sparklers in both her hands for me,

and saved the day

when I had run away

to envy and black feelings.

And the world at night

could see the greatest light.

Too much light to deny.

With repeated listenings, you will find these songs stay with you, and in spite of their acknowledgment of life's darker side—indeed, because of that inclusion—they can be a source of strength, turning our attention to the future and to the benevolence of the Divine. I've taken to playing Birds on my headphones on the bus ride home from work; it reminds me that, when things seem heavy and burdensome, I have much to cherish, anticipate, and enjoy.

Often dismissed as merely sentimental and naively optimistic, The Innocence Mission remain a needle in a haystack, a mother lode of musical gold in the mountain range of modern pop music. While so many bands dwell on cynicism, on shallow love songs, on diatribes and proselytizing, Karen and Don Peris and Mike Bitts have crafted four albums of praise songs, meditations, reminiscences, poems, and stories that have the evocative power of an old photo album. They offer themselves through music as good friends, trusting the attentive listener enough to confide in them.

Five words or less: Deep comfort and delicate grace.

Over the Rhine's "Ohio": A Double Dose of Brilliance

"I want to do better, I want to try harder," sings Karin Bergquist at the opening of Disc 2 in Over the Rhine's monstrous, beautiful, country-laced double-album Ohio. The next line in the same lyric gets at the essence of the album: "I want to believe... down to the letter."

Clearly, they are trying harder. And, yes, they're doing better too. Turning the spotlight fully on Karin's performance as a stellar vocalist and an intense, intuitive interpreter of Linford Detweiler's poetic lyrics, Over the Rhine have burned what many will declare their brightest hour, and this reviewer would be hard-pressed to argue.

While somewhat different in character, the two records fuse into an impressive tome of short stories about faith fallen on hard times, relationships breaking up, a nation losing its grip on its ideals and innocence. Call it a heart attack in the heartland-outcries for redemption, rejuvenation, and guidance.

Sonically, Ohio finds Linford and Karin adding colors to their palette, expanding on the folk-rock foundation of their strongest album-Good Dog, Bad Dog. There's a bit of the power-pop polish of Films for Radio, but primarily the duo and their everchanging body of supporting players dig deeper into the enchanting organic sound the fans have come to love. Producer/engineer Paul Mahern, a mixing-board veteran of recordings by Neil Young, Willie Nelson, Iggy Pop, and others, captures a bright and polished sound, even though there are no samples, loops, or special effects anywhere on the whole project. What makes the material sound so new and fresh is the surprising dose of country in the mix, and the new interest in storytelling rather than confessional catharsis. It's likely to provoke Emmylou Harris to revise her list of "Songs I Must Cover."

Of course, the question is: How did they convince their label, Virgin/Backporch, to let them release a double-album when they remain, mysteriously, such an low-profile wonder?

Double albums happen for supergroups after the release of the Album that Made them Big. I suspect that the folks at Virgin, being in on the secret of the band's abilities, just couldn't resist the idea of two full discs of new material, even if only for their own indulgence. Who knows? Whatever the reason, it's good news for Rhine-landers. Most of the 21 new songs can stand with the best work the band has ever done.

Most of them. This listener prefers to think of Ohio as One Perfect Album and then a second disc that could be called Encores and Great New Ideas. Disc One flows beautifully, taking you to exhilarating heights, then down into the bluest blues and painful craters of heartbreak. Disc Two keeps one foot planted in the band's essential sound and style, but set the other foot in unexpected territories. It feels to this listener that two tracks toe the line of "b-side" material. Fans will argue about "the song that could have been cut." But it is almost inappropriate to quibble about this in view of how generously the band has delivered this time around.

Here is a journey through Disc One, to scratch the surface of the project's riches, and then a few thoughts on Disc Two as well. (Wouldn't want to spoil too many surprises....)

And of course, these interpretations are all the opinion of just one listener. To quote some of the band's own lyrics:

I am truly skeptical of all that I have said...

DISC ONE

In "B.P.D.", a knockout opening number. Karin's chords provide persistent piano pulse. You start itching for the guitars, and they come, finally, but Karin's vocals are what carries the song into the stratosphere. It's a revelation, like you've never heard her before. "I'm waiting for the end," she sings, "Waiting to begin again." And you half-expect to hear some sort of explosive transformation right at the microphone, as the song builds in intensity. (In concert, it does explode-don't miss the next OtR tour, because they take these songs to higher heights, carry them greater distances.) Karin seems to be singing a reproval to someone whose foolishness she cannot prevent, clean up, or help. But the more she sings, the more she seems to include herself in the reproval, until she concludes, "Only God can save us now."

The song burns with a kind of energy that gives you high expectations for the rest of the album. And those expectations are met over and over again.

"What I Remember Most" is a soulful number. It aches with a lover's suspicion that a relationship may all be coming to a close. The singer, while devastated by her own intuitions of disintegration, sounds confrontational, trying to bring on the inevitable catastrophe so at last she can know the truth and be set free from this period of uncertainty.

The saddest songs are the happiest

The hardest truths are the easiest

Put us both to the test

And tell me if you still need me

And I will swallow these words

And see if I can still believe

The brilliance of this album's lyrics lie in the way each song of relationship, with its particularity and storytelling, still leans toward addressing larger issues-the breakdown of innocent faith; the divorce of a nation and its ideals. Sometimes, the lyrics do more than lean that way. Karin sings:

This American dream may be poisonous

Violence is contagious

Crowded or empty

I walk these city streets alone.

Since the album's angst seems capable of capsizing it at this point, the band fortunately lets the sunshine in with "Show Me"-a clear choice for the first single. And while it is as shameless a pop number as they've ever recorded, the country styling and zippy guitar solo make it stick. And the lyrics are a country mile from your typical pop sentiments of infatuation. Karin's singing about a time-tested love, the rewards of fidelity in the midst of the intimidating chaos. She lays out a simple appeal on a bed of la-la's: "Can we make it last? Can we make it real? Come on and show me how it feels..."

Continuing in this vein of things we can affirm in our distress, "Jesus in New Orleans" is a tipsy little number of blissful blues, with enough of a sense of humor to juxtapose "Jesus" and "bloody Marys" in the same line. It's almost like Linford is showing off how good a lyricist he's become, spinning little webs of exquisite physical details that say so much about emotional truths. "She wore a dark and faded blazer / with a little of the lining hanging out..." Karin makes this character real, singing, "The road's been my redeemer." It is worth noting that, while this album finds the band reflecting with a heavy heart on the wounded state of this world, they are making even bolder assertions of responsibility and faith in the midst of it:

But when I least expect it

Here and there I see my savior's face

He's still my favorite loser

Falling for the entire human race

Ain't it crazy

What's revealed when you're not looking all that close

Ain't it crazy

How we put to death the ones we need the most...

"Ohio" is the album's most intimate moment, taking the album's spiritual themes to the specifics of a small-town breakdown. Karin sings alone at the piano, and this is where the album drops anchor. She's turning pages of memories like browsing through a photo album, broken by the story of collapse, and yet relieved to leave it all behind. (Karin grew up in Barnseville, a small town in the Ohio Valley, while Linford grew up not far away in Hartville and Fairpoint.) Perhaps it is the personal nature of these stories that makes this record clearly the pinnacle of Karin's career as a vocalist. She has never sounded better or more inspired. I'm convinced God invented vowels so Karin could sing them, long, slow, drawn out.

"Suitcase" is another heartbreaker, all the more sour for its sweet musicality and the almost casual nature of Karin's vocals.

Whatcha doin' with a suitcase

Tryin' to hit the ground with both feet runnin'

Aren't you trippin' on your shoelace

You're stealin' away on a sunny day

Well aren't you ashamed at all

Funny but I feel like I'm fallin'

The longtime concert favorite "Anything at All" finds its finest musical arrangement here. Tony Paoletta's visceral dobro notes curl around the edges of the verses. It also gives us another gospel-grounded affirmation: "Sooner or later, things will all come around for good / Sooner or later, I won't need anything..."

"Professional Daydreamer" gives new punch to the sentiment "Parting is such sweet sorrow." It's another song about the strong bonds of intimacy and the bloody agony of parting.

"Lifelong Fling" is as dreamy and sexy as anything they've recorded. It's a ramble that echoes their concert favorite "My Love is a Fever", in which Karin chews on the lyrics, stretching and twisting the words like they're made of salt water taffy. As she illustrates the joys of true love's journey, she makes it as enchanting as a children's picture book. Get a load of this:

The moon blind-sided the sky again

As we grabbed loose ends of the tide and then

The slippery slide

You know I can't say when

I ever took a ride that could slap me this silly

With roiling joy

Linford's keyboards mix with Paoletta's toe-curling pedal steel in an extended jam that only heightens the joy.

And then they lower the boom.

"Changes Come" is a difficult song for me to write about... perhaps I shouldn't. For this fan, it rivals "Latter Days" as the most exquisite, painful, and glorious thing they've recorded. At their Cornerstone concert, Karin said that they wrote this song after watching the news while tanks rolled through Baghdad and Bethlehem. You'll believe it. And during this soulful lament, performed entirely by the two of them, she confesses some intimate fears in frank, but fitting, words.

The finale soars as she slowly shifts the refrain: "Changes come, turn my world around" into an echo of Psalm 40: "Jesus come, bring the whole thing down..." If you don't need a period of silence after this song, you aren't paying enough attention.

DISC TWO

Disc 2 continues the storytelling cycle of lives cracked open, of raw and painful need for solace and healing.

"Long Lost Brother" is the song quoted at the beginning of this review. "I thought that we'd be further along by now," she sings, a sentiment that rings true as we watch the news of pre-emptive war. It's another profound and plaintive cry for a second chance in the ruins of this world we have wrecked.

"She" is an achingly sad story of domestic abuse, in which Karin struggles to focus on the woman's sad story and state of mind, but can't help injecting her own feelings that she should put a gun to her husband's head.

"Remind Us" returns Karin to the piano for a heavy-hearted anthem of wartime and mourning:

Can't bear the news in the evening

We're going to bed and we're going to war

All of this for

Anyone's guess

If we forget anything

Heaven forbid someone would remind usSinners and saints, priests and kings

Are we just using God for our own gain

What's in a name

Open your eyes...

Railing against complacency in times when action and clear thinking are crucial, "How Long Have You Been Stoned?" growls along a cantankerous rock and roll groove,

"Nobody Number One" rambles in the vein of "My Love is a Fever" in which she wrestles with the incurable problem of pain and hard questions: "You can't put no band-aid on this cancer / Like a twenty dollar bill for a topless dancer / You need questions, forget about the answers..."

"Cruel and Pretty" turns a Chagall painting into song, as dreamy as a sultry summer evening, celebrating the power of art to draw us up out of our sufferings into "the backstreets of heaven."

And yet, while the sincerity remains strong, the intensity of the early songs begins to slacken, slightening the album's overall impact. "When You Say Love" is a zippy little number, but a keyboard bit that I find annoyingly simplistic accompanies the redundant refrain.

"Fool" is a soulful performance in which Karin croons for a holy fool... probably THE Holy Fool... to continue seeking her in spite of her meandering nature: "Fool, pursue me from heaven above or to hell below / Just don't let go..."

"Hometown Boy" revisits their new country-flavored style with shimmering slide guitars, sharing more intuitions about the world "breaking down", more sentiments about wanting to get out of town instead of slipping into complacency.

When the new version of the fan favorite "Bothered" finally arrives, it gives the record a much-needed return to the poetry and intensity of the first disc. The new slide guitar, punchy rhythms, and dreamy background harmonies are a nice new cast for the song. But it begs the question of why they felt it necessary to record it again. Perhaps they felt that the lyrics, which exhort us to put aside our fears and turn our attentions to faith, was a proper conclusion to a journey through sufferings, changes, and disintegration. I'm not complaining--it's beautiful.

Surely, though, the final track, "Idea #21 (Not Too Late)" stirs up enough intensity to bring closure, with its echoes of "How long?" It brings the car to a slow stop in the driveway of a church, for a rousing bit of gospel. Who could ask for a better destination in view of all of these tales of sorrow and searching?

ALL IN ALL...

Ohio is evidence that Linford and Karin are in as prolific a period as any chapter of their career, undiscouraged by change-ups in the band makeup, ready to explore new expressions and sounds both old and new. Fans will certainly be pleased to have such a feast of fine work, but the question lingers-will Ohio's plentitude blunt its impact on newcomers? Would an abridged, more focused edition made for a stronger, more cohesive release?

Time will tell. Surely the band struggled with those questions. But when it comes down to it, you would be hard pressed to cut this back to a ten- or even a fifteen-song collection. We can be grateful that Over the Rhine is in peak condition at 10 albums old, and show no sign of slowing down. They remain one of contemporary music's deepest and strongest rivers, offering rest, refreshment, inspiration, and reflection... to those fortunate enough to find them.

Best in Show (2000)

[This review was first published at the original Looking Closer website in 2001.]

•

Sometimes humans are more beastly than their pets.

Christopher Guest's new "mockumentary" about dog shows, Best in Show, revels in that fact. The nine human beings that converge on Philadelphia for the Mayflower dog competition seem themselves to represent a wide variety of breeds, grooming styles, and gaits, regardless of the quality of their dog. They all want to be validated by the success of their particular pooch. And the pressure has them all on the edge of cracking.

Guest is drawn to this sort of context. In This is Spinal Tap, which he co-wrote with Rob Reiner, he spoofed heavy-metal showbiz, turning the volume up to 11 on the pomposity, lunacy, and theatrical bombast of arena rock. In one of the 90s most underappreciated comedies, Waiting for Guffman, he painted an affectionate portrayal of a small town drama group dizzy with Broadway ambition while they prepare a musical. In both films, most of the humor came from a wide array of characters who are blind to their own eccentricities. But Guest was able to treat them warm-heartedly, so audiences could enjoy their company and see themselves mirrored in these exaggerations, like looking into a warped mirror at an amusement park.

Best in Show continues the tradition. In the company of spoiled dogs, these characters reveal their own pride, their own aspirations, and their own alarming breaking points. The movie might as well have been about a fashion show for children, a sports car exhibit, or an art show. The owners are the real subject here. Their treatment of each other, their bark, their bite, and, of course, their mating habits... we learn more than we might care to from behind-the-scenes bickering and boasting.

Guest has an affection for human oddities. He isn't afraid to tell us the embarrassing and alarming truths about his subjects, but, as Steve Martin does with characters in his own films, he finds room to forgive and even admire them. They're too crazy to be real, and yet I'll bet we all know people who behave like these folks. And if we're honest, we'll admit that we sometimes can be so petty ad so proud.

The film focuses most on Gerry and Cookie Fleck (Eugene Levy and Catherine O'Hara), a middle-class, rural couple whose unlikely marriage is peppered with uncomfortable mysteries. Levy has a strange disorder of the feet. O'Hara's has a list of ex-boyfriends a mile long, and it's a small world; much to Gerry's chagrin, these exes seem to be waiting behind every tree. Their journey to the dog show becomes something of a marriage encounter, and we wonder if the trials of their journey will break them apart or bring them together.While almost all of their scenes are laugh-out-loud funny, they do become endearing personalities; we care about what happens to them in the end.

Stefan Vanderhoof (Michael McKean) and the flamboyant Scott Dolan (John Michael Higgins) are a gay couple who spend more time grooming themselves than their criminally-cute canine. Harlan Pepper (Christopher Guest himself) southern-drawls about his bloodhound's telepathic powers, his own strategies in fishing, and a budding interest in ventriloquism. Kennel owner Jane Lynch (Christy Cummings) brags about the champion poodle owned by the grossly-glamorous Jennifer Coolidge (Sheri Ann Ward Cabot). And Parker Posey and Michael Hitchcock are the far edge of frightening, their marriage based on name-brand fashion wear preferences and varities of Starbucks coffee.

The most outrageous personality of all waits until the final chapter of the film to appear. Fred Willard plays Buck Laughlin, the show's television broadcast announcer, and he brings down the house with his dimwitted commentary, self-absorbtion, and unintentionally revealing one-liners. Willard became one of my favorite comic actors in Roxanne, when he played the small town's mayor and declared, "I would rather be with the people of this town than with the finest people in the world!" Here, he's funnier than he's ever been, as Laughlin relentlessly delivers inappropriate banter. (''It's terrible to think that in some countries, these dogs are eaten!'')

Best in Show stretches out its scenes to allow for more improvisational genius, more unlikely moments of manic hysteria, more subtle observations about its characters. Frankly, I think the movie could have used another twenty minutes. Not more laughs, necessarily. But 90 minutes doesn't give us much time to think about what Guest might be suggesting about human nature. Perhaps he just wants to have fun, but I sense a striving for something more. I suspect he wants to show us something about the nobility of simple accomplishments. There is a celebration of simple folk, of teamwork, of small victories. And, as in Guffman, there's an appreciation for the spectacle of those events... dog shows, community theater, or whatever...that bring people together and challenge their creativity. If Guest wants to do this, I think he might dig a little deeper.

But that's a minor gripe. In a year when comedies are rushing to new lows in crass humor and mean-spiritedness, Best in Show is an excellent example of how funny a movie can be merely by observing human nature honestly, at its brilliant best and miserable worst. It's only 90 minutes long, but I'll bet it's the best hour of laughs you'll find at the movies all year, and probably one you'll want to revisit again and again.

Sam Phillips - A Boot and a Shoe

When no one’s listening I have so much to say...

When no one’s listening I have so much to say...

That’s a line from “How to Quit,” the first song on Sam Phillips’ A Boot and a Shoe. It’s a loaded line. She’s been a critically acclaimed singer-songwriter since her debut The Indescribable Wow in 1988. Her work has been consistently produced by the best in the business—T-Bone Burnett—every step of the way. If the torch of the Beatles’ sound, style and songwriting prowess has been carried by anyone, it’s been Sam, who sometimes seems to be singing the catalogs that great band would have produced had they stayed together, alive, and relevant. You’d be hard pressed to think of a vocalist so interested in sonic invention and re-invention. Her songs have been the soundtracks for films, her catchy pop hooks have been the barbs of commercials, and her smooth harmonies have supplied the interludes for a popular television series. And yet today, she remains “undiscovered.”

All the better for the fortunate few who have faithfully followed her all these years. It means we stand a chance of getting into the intimate concerts Phillips is performing at a few select venues around the country. Her tours are rare and wonderful events. And this time Phillips is sharing with audiences the confessions, pain, poetry, and revelations of a pivotal time in her life.

I was broken when you got me

With holes that would let the light through.

As she so often does, Phillips is again focusing on a state of brokenness and the way that having our hearts split open by betrayal, anger, loss, and change can open us to the influence of divine grace. When Phillips sings about loss, the songs just ache with personal confession and raw need. It’s a theme that goes all the way back to her 1986 album The Turning.

You probably know the story. (If so, skip to the next paragraph.) In 1986, Phillips was recording under the name Leslie Phillips, and was a celebrated Contemporary Christian music pop star. That kind of singing made fans of safe, preachy, positive Christian music uncomfortable. When she unveiled songs about disillusionment, unanswered prayers, and a restless need to break away from the expectations of her judgmental peers, it quickly became clear that such honesty did not belong in the Christian music industry. The Turning proved indeed to be a turning point. She changed her name to Sam, her childhood nickname. And she married T-Bone Burnett. Thus was born one of the most interesting marriages in rock history.

Sam’s music has always been about two kinds of relationships, the flawed, needy, desire-driven human loves, and the transcendent, mysterious, elusive romance with a benevolent God who never lets her rest. God is a mystery lover, a relentless pursuer, who constantly whispers that we should look past the visible world to invisible realms of truth and mystery. His love does not follow the straight lines of logic or reason, but asks us to step into the darkness of faith. On her last album Fan Dance, she sang, “I’ve tried, I can’t find refuge in the angle. I walk the mystery of the curve.” That courtship continues here….

All night, all night,

I’ve been looking for you all night…

No straight lines when love unwinds out in the night where you took the light

You’re all around but I haven’t found you

You’re coming in, right through my skin,

Oh comrade, what do you need?

While the listener cannot escape the sense of God’s nearness to the singer, A Boot and a Shoe is primarily about the collapse of a human relationship. We are given hints of this mismatched couple’s story. While the singer was drawn to the magnetism of someone who met her needs, she has found herself unable to keep them from being torn apart by human desire. Whatever the details of their marriage, it’s clear that Phillips is again at a turning point. She sings about wanting more, wanting to maintain the relationship, but realizing that it is too late and there is nothing she can do.

Thus, this record reveals a significantly changed artist, one who is letting go, humbled, softened and bruised. She has lost that cocky edge, that searing sarcasm, that voice of authority.

Thus, this record reveals a significantly changed artist, one who is letting go, humbled, softened and bruised. She has lost that cocky edge, that searing sarcasm, that voice of authority.

In “Love Changes Everything” she sings about being glad for the experience, even if she must also humbly admit that things have become broken beyond repair.

Love changes everything

I’m not sorry we loved,

But I hope I didn’t keep you too long

And yet she bravely vows to continue in relationship for the good that can come of it. In a way, she’s affirming the good work they do together, even when intimacy fails.

We’re not experts

We are believers, ministers of silence

Let no man pull us under doubt

I’ll always open my hands to you

I’ll be right behind you

In “If I Could Write”, things become even more explicit, as she talks about this significant other who tends to draw “girls looking for themselves in [his] eyes.” Was she once one of those women, impressionable and vulnerable? The reference to his ring, which he no longer wears, is as blunt as any line on the album:

I took your ring that never comes off and put it on

Sorry to lose you, sorry to keep you after you were gone

Nothing is small, nothing is unexpected

I want more

When I go this time I don’t think I’m coming back.

Desire’s the element I can’t fight,

Dream is the arm of God.

The album is not all so confessional and sad. There’s an infectious sense of playfulness. Where Fan Dance was an album heavy with acoustic guitar, this album is her most percussive endeavor. The drums are quirky, unpredictable, and dominant. In the groovy shuffle “Draw Man,” both Carla Azar and Jim Keltner provide percussion while the Section Quartet carve out a rough-edged string solo. This fantastic ensemble returns her to one of her favorite subjects… digging deeper, excavation, exploration. And yet she’s still exploring—in fact celebrating—her relationship with her creative partner:

Dig baby you’re a draw man

A pipe man, a furnace, a filler

Let’s make time escape

Let’s excavate the surface…

Her refusal to resort to self-pity and despair gives the album room to develop a pervading sense of hope. It’s a feeble but unfailing belief that in the brokenness there is opportunity. In what may be the most beautiful song of her career, “Reflecting Light,” she sings,

Now that I’ve worn out, I’ve worn out the world

I’m on my knees in fascination

Looking through the night

And the moon’s never seen me before

But I’m reflecting light…

It’s that sense of wholeness in brokenness, of being a channel for grace, of suffering being the conduit for a testimony of unconditional, everlasting, sublime love that continually elevates Sam’s music. And what sets apart this collection is the way she draws back from that hard-edged, stern, assured voice and sings more softly, more cautiously, as if to herself in the darkness where she, having lost it all, she is experiencing a fullness beyond herself, reflecting light from a truer source than herself. Help is coming on God’s time, not ours.

So we conclude with an affirmation that God’s love is the kind that waits until the thing is dead and buried, and that’s when new life comes. As Bono sings, “Midnight is where the day begins…”

Help is coming, help is coming

One day late

After you’ve given up and all is gone

Help is coming one day late

You try to understand, you try to fix your broken hands

But remember

That there always has been good like stars

You don’t see in the day sky

Wait till night

We may not understand, and my tentative speculative endeavors to understand these lyrics may be spectacularly misguided. But the lyrics are so beautiful, spacious, and sung with such sadness and need that they lead me to the place again to which The Turning led me in 1986... to a remembrance of my vulnerability and total dependence upon the mystery of Christ, my rock and my redeemer, when all else is shifting sand ... even those contracts I tend to assume are most binding.

When no one's listening, she does indeed have so much to say... for those with ears to hear.

Sam Phillips will be playing at the Century Ballroom in Seattle on June 5th, 2004.

Bringing Out the Dead (1999)

2015 Note: This review was originally published at a church website called Green Lake Reflections in 1999, and was quoted in the very first installment of Christianity Today's Film Forum, which was hosted at that time by Steve Lansingh.

•

It sounded promising. The greatest American director working in his favorite neighborhood again, with one of the greatest American film actors. When you hear Martin Scorcese, Nicolas Cage, and a story about the underbelly of New York, you automatically anticipate raves on all critical fronts. And Bringing Out the Dead delivers a lot of what Scorcese fans expect. But not enough of it.

Great acting. Great cinematography. And Scorcese himself in his best role so far... the voice on the radio that calls ambulance drivers out on their cases! But is it a great story?

Perhaps Scorcese was drawn to the idea of working at night, in a modern context, revisiting the tension and the menace of New York streets as seen from behind the wheel, applying his newer filmmaking tricks to a story that echoes his early classics (Mean Streets, Taxi Driver). Unfortunately, while he still films these streets with an intimate understanding and photographic finesse, the script doesn't really work. Instead of watching a character disintegrate or rise from the ashes, this movie's hero has already fallen too far, and we just watch him being miserable.

Bringing Out the Dead is like a sad, pale echo of Dante's Inferno. Frank Pierce (Nicolas Cage) is an ambulance driver named Frank Pierce, the son of a nurse and a bus driver. So he's a little of both. That's one of his jokes, one of the bits of humor he clings to so desperately in order to maintain some semblance of sanity. Frank is in trouble. He's slowly burning out after countless nights of visiting crime scenes and attempting to rescue the lives of New York's self-destructive night life. Most of the cases he responds to are merely the "regulars", people prone to hurting themselves in desperate bids for attention and love. One is called Mr. O, and it's not hard to see why; when they visit him he can only communicate with long moans. "Ohhhh... ohhhhh."

Frank's various ambulance partners are either weaker, stronger, or weirder versions of himself, who either try and encourage him to stay strong or else speed him on his way to becoming a casualty himself. I half expected one of his half-crazy cohorts to suggest they go to Brad Pitt's Fight Club and let out their anxieties in a fistfight. Haunted by the ghost of Rose, a homeless woman who died during his CPR efforts, Frank drinks, smokes, and depends on adrenalin to keep himself moving, fearful of the thoughts the catch up to him when he stands still. Just as many of the wounded are too tired to go on living, Frank is so tired of his job he is begging to be fired.

Frank explains the toil of his job as a failed lifesaver to the audience in a steady, sleepy narration. After meditating on the fleeting joys of saving a life, he observes, "Taking credit when things go right doesn't work the other way around." When a patient dies, as is usually the case, and the families and friends at the deathbed grieve, all Frank can muster is a feeble "I'm sorry." And then come the voices. Victims reappear, blaming him, crying out, dragging him down.

It's only when one of his colleagues plunges headlong into madness that Frank himself receives a shock to his system and tries to wrench himself free of despair and rid himself of Rose's relentless ghost. I kept waiting for Scorcese to give us room to consider questions of faith or an opportunity for love, to contemplate where a soul might find solace in this context. But he seems too preoccupied with the violence and the bizarre predicaments that Frank discovers along the way. This frustrated me and made me wonder why he would want to pound on the audience this way.

But there is much to admire about the film. As Frank, Nicolas Cage is excellent, a believably desperate soul. Since his jarring, incredible performance in Birdy, Cage has been the best actor around for playing haunted, desperate men, whether it's comically (Raising Arizona), commercially (Face Off), or melodramatically (Leaving Las Vegas). As this desperate soul at the wheel, he's mesmerizing. And his supporting cast is just as strong: Ving Rhames, Jon Goodman, and Tom Sizemore are his partners, and Patricia Arquette (Cage's wife) is the lost and lonely soul with whom he discovers a tenuous friendship.

But even as the cast were entertaining and appropriately bedraggled, I found myself anticipating a compelling plot to rise up amidst these details. Perhaps I had the wrong expectations, but even if this film is intended as a mere character sketch, its a tedious sketch that wears out its welcome long before we see Frank Pierce come to any kind of epiphany. Bringing Out the Dead employs a lot of talent in yet another aimless, dark and violent story. The last thing the cinema needs is more blood, violence, and despair. Films like Three Kings show us that violence can be effective, even essential, to storytelling. This film does not. And I don't recommend it, unless you care to see the best Nicolas Cage performance in several years, or some more of Scorcese's brilliant camera work.

Swimming Pool (2003)

This post includes two reviews here: My own and a guest review by Michael Leary.

•

The supremely talented French actress Charlotte Rampling and director François Ozon clearly enjoy working together. Rampling relishes psychologically complex roles. Ozon respects his leading ladies enough to give them challenges.

In Ozon’s Under the Sand (2001), Rampling played a French woman who chose to live in denial of a tragedy — namely, that the sea had swallowed her husband. She developed a fantasy life that their marital bliss continued, even as her friends began to see cracks in her sanity. But instead of regarding her as a psychopath, we were drawn into sympathy for her. After all, she seemed happy so long as her imagination kept true love alive.

Now, Swimming Pool turns things around. A different sort of loss, a different sort of fiction, a different body of water.

Rampling plays Sarah Morton, a British mystery writer, who learns that there is no better cure for writer’s bock than a good hard rejection. When her handsome publisher (Charles Dance) offers her a retreat a la Enchanted April at his idyllic Italian getaway house, she accepts. But when she flirtatiously suggests that he join her there, he either ignores the hint or misses it entirely. Sarah departs with wounded pride.

Despite the idyllic conditions of her vacation, Sarah’s humiliation sours into ugly resentment. Like any good writer, she gets right down to work, exploiting her experience for literary inspiration.

But things go from bad to worse when the publisher’s obnoxious daughter Julie (Ludivine Sagnier) appears out-of-the-blue. Like salt in an open wound, the girl manifests all of the seductive raw materials that were lost to Sarah years ago. At first the reluctant housemates hiss and spit like angry cats. But when Sarah glimpses psychological bruises beneath Julie’s seeming perfection, she lunges for them, determined to transform what she learns into a writer’s vengeance.

Julie struts through most of the film half-naked, lounging nude by the spectacularly blue pool and baiting men from the nearby town into one-night stands. While the character is certainly an exhibitionist, Ozon’s intentions with Sagnier are not pornographic. Instead, he creates a visual point/counterpoint: Sarah’s souring physique and Julie’s statuesque shapeliness, Sarah’s mature British formality and Julie’s adolescent French libertinism. Who seems more monstrous in the end, the shallow temptress or the sophisticate who, while smiling, is a villain? It is no wonder that Sarah cannot tolerate the decorative cross on the wall of her room. She has little regard for her own conscience, which becomes very clear when a dead body shows up in the backyard shed.

Swimming Pool ends up not so much a mystery as a revenge story. But this time, Sarah’s wounds have not won our sympathy. This begs the question: Is Ozon suggesting that the artist at work is engaged in empty self-gratification?

Unfortunately, the film’s dissatisfying surprise-ending spoils intriguing questions and possibilities with a predictable contrivance. Despite Rampling’s compelling performance, we emerge from Swimming Pool feeling cheated. What began as a high dive becomes an abrupt landing in the shallow end.

•

A Second Opinion - by Michael Leary

There are a few things thing that make Swimming Pool a predictable film, and there are a few things that don’t. It really is classic, predictable Ozon. Take for example his lecherous Water Drops on Burning Rocks (2000), a film that plays with itself like an obscene Rohmer script in three acts. Its form is timeless and classic, but somehow Ozon manages to turn the convention on its head through the storyline. Much in the same way, Swimming Pool is a classic mystery thriller, but one that manipulates itself to a rather unconventional level of mystery and leaves us with a wry unexpected twist that alters our perception of the entire film. Where the film gets highly unpredictable is that Swimming Pool’s twist turns out to be uncharted waters, even for someone like Ozon.

As is customary for Ozon, the camerawork in Swimming Pool is alluring, almost sensual. Similar to his other 2000 film, Under the Sand, his shots more frame states of mind than they frame characters. He places people in scenes by means of composition as Hitchcock often did, but with a certain continental flare. We move from texture to texture and focus to focus under the influence of some cinematic rhythm. Guided by this visual precision, Ozon takes us from a listless and despondent London to a charming villa in Southern France. The first quarter of the film is dominated by these silent sequences in which we simply watch Rampling explore this gentle shift in her environment. It may be these subtle psychological passages that Ozon has a gift for catching on film.

The script itself is by Ozon. It's Claire's Knee meets Vertigo or something of that nature. The story unfolds at a clever pace and even though at times it unravels by the numbers, we don't mind because Rampling pulls it off with a frightening ease. Rampling plays Sarah Morton, the writer of a famous churlish detective series. Coming to grips with the fact that she is a potential has-been, she visits the office of her beguiling agent, a man transparently interested in Sarah as a cash-cow. So he advises her to take some time off at his French villa, and perhaps write a new book while she is there.

After a few days, to her unveiled dismay, her agent's teenage daughter pops in for a holiday as well. Equal parts, shameless lust, sordid charm, evenly tanned skin, and je ne sais quois, Julie’s reckless abandon is a startling dialectic to Sarah’s British rigor. Everything from Julie’s dirty relationships with older men from surrounding towns to the foods she fills up the fridge with stand in contradistinction to Sarah’s emotional repression and ascetic diet. The delicate friendship they eventually forge occurs through conversations about Julie’s distant mother, and the hesitant rifling of Julie’s private journal rekindles Sarah’s literary genius. She begins to write a book, no doubt starring Julie and the clues that comprise the mystery of who she is. And as she writes, the narrative takes a few strange steps into the other side of the looking glass. On this side of the story we find that Sarah and Julie may not be all that different after all, and the cool blue water of the swimming pool becomes the backdrop for the stuff only the best dime store crime novels are made of.

All of these brilliantly crafted relationships unravel in the last frame of the film, closing on Rampling’s intriguing smile. The book she brings back from her vacation is like nothing she has ever published, not your average pulp “whodunit.” And as it turns out, neither is Swimming Pool. What seemed to be straightforward storytelling is revealed as an intimate character study. What seemed to be mysterious really just turns out to be intentionally vague. Some may leave the film underwhelmed; feeling tricked into a conclusion that raises more questions than the film has the ability to answer. But taken as a brilliant psychological adventure Swimming Pool has the fortunate position of being able to spurn such analysis, and the turn toward the inexplicable at the end of the film only serves to add more depth to a character that it seemed Rampling had taken as far as she could go.

Gangs of New York: a Looking Closer Film Forum

This edition of Film Forum was originally published at Christianity Today on December 19, 2002.

•

Gangs of New York is director Martin Scorsese's much-anticipated film about an uprising of Irish immigrants against a gang called "Nativists" who seek to drive them out of Civil-War-era New York City.

Leonardo Dicaprio stars as Amsterdam Vallon, a tough young Irishman who returns to a poor New York neighborhood called The Five Points in order to avenge the death of his father (played in the prologue by Liam Neeson.) Vallon's father died a principled Irishman defending the rights of Irish immigrants to live in peace on American soil. His murderer was William Cutting (Daniel Day-Lewis), also known as "Bill the Butcher," the leader of an immigrant-hating gang. Vallon's revenge quest gets complicated when he finds himself adopted as the Butcher's apprentice in all things devious and violent. The stakes are raised higher when he falls in love with Jenny Everdeane (Cameron Diaz), a pickpocket and con woman who is dangerously close to the Butcher's cold cruel heart.

This story would seem predictable. But when the inevitable confrontation finally arrives, Scorsese pulls the rug out from under us. We realize the film is not about something as frivolous as a blood rivalry between two men. It is about the consequences that occur when the rich turn a blind eye to the poor.

The violent clashes that bloody these filthy streets are symptoms of poverty in the big city. In the 1860s, immigrant men were drafted into Civil War duty as soon as they stepped off the boats, even if they were not supporters of Lincoln. Meanwhile, rich men could buy their way out of the draft for about $300. Seeds were planted for distrust of the government, and prejudices that deepened during that time continue today. This deep civil unrest sparked a fire that became the Draft Riots, an outburst of rage and violence that threw New York City into a Civil War of its own, the bloodiest riots in American history. Scorsese concludes his film with a suggestion that the oppression of the poor by the wealthy continues today.

Dicaprio makes Vallon a charismatic savior, rallying the Irish to his cause; but alas, he is only a savior by violence, far too willing to compromise his innocence in order to achieve his goals. Thus, the price of vengeance grows costly indeed.

Dicaprio's solid work pales in comparison with the spectacular return of Daniel Day-Lewis. His sneering, roaring, monstrous performance as the Butcher will remind you of Robert DeNiro in his prime.

The supporting cast is effective as well, featuring strong turns from John C. Reilly (Magnolia), Henry Thomas (E.T. The Extra Terrestrial), and Brendan Gleeson (Braveheart.) Cameron Diaz holds her own in the midst of such formidable talent.

The script by Jay Cocks, Steven Zaillian and Kenneth Lonergan shows a close study of the dialects, accents, and prejudices of the day. The cast sinks their teeth into the script with the same enthusiasm they would give to Shakespeare. In fact, the film resembles the sort of bloodstained epic Shakespeare would have written had he been a student of American history.

Gangs is a complicated film, both great and deeply flawed, that plays like a dirge for the poor who still suffer from the neglect of the rich and powerful. Regardless of the creative liberties taken by Scorsese in telling his tale, it's the most shocking and troubling film about American history I've ever seen. (My review is at Looking Closer.)

Other religious media critics have yet to offer reviews, but mainstream critics are already debating the pros and cons of this long-awaited production. Rumors of trouble between the director and the studio have led to debate about the difference between this version and an earlier, much longer version of the film. Columnist Dave Poland mourns the absence of Scorsese's original vision from this abbreviated edition.

Richard Schickel (TIME) is quite impressed: "Today when audiences go into the past, they want fantasy. They're not looking to pay for history lessons. Thus Gangs may be the epic's last gasp. If so, it is a gasp that sings, howls, like a grand tenor at an Irish wake." Roger Ebert (Chicago Sun-Times), who offers an interview with Scorsese, claims, "No movie has ever depicted American poverty and squalor in this way."

David Denby (New Yorker) is not satisfied. "What's on the screen [is] grisly and heavy-spirited. Somewhere along the way, Scorsese's conception turned vague and then got pickled in excessive production values." But he praises Day-Lewis's acting as an event in itself. "[The Butcher is] a consciously theatrical monster, and Day-Lewis — an actor playing an actor — returns to performing with a glee that he's never shown before."

from Film Forum, 01/02/03

Gangs of New York, which Film Forum covered in detail two weeks ago, continues to irritate and infuriate religious press critics with its graphic violence. Further, some were not pleased to see American history portrayed with such rough edges.

Michael Elliott (Movie Parables) is one of the few praising its achievement: "While DiCaprio does a fine job playing the conflicted Amsterdam, this film belongs to Daniel Day-Lewis who presents one of the most complex and richly shaded villains in recent memory. [The filmmakers'] vision of what Manhattan might have looked like over 150 years ago is magnificently realized."

Simon Remark (Hollywood Jesus) also raves: "No other filmmaker has looked at the human condition and the inner struggle between flesh and spirit quite like Martin Scorsese. … Scorsese again looks at the human condition and the strongest of human emotions: love and hate. Scorsese again proves to be one of the most significant, profound filmmakers of our time."

Others are too battered by the film's violent subject matter. Gerri Pare (Catholic News Service) "With all the characters so vicious, the story has little emotional resonance. Despite the film's belabored ultra-realism, it fails to be dramatically stirring. Instead of a story about the immigrant experience in 19th-century New York, it seems more about butchery for its own sake and the love of slaughter." Movieguide's critic says the film is "a bloody, dark, depressing, hopeless depiction of 'eye-for-an-eye' violence, torture, and cruelty, plus graphic sexual immorality and nudity. It is not an American History film, but a revisionist political treatment that attacks faith, God, and America. This movie reaches new lows in bloodletting." Phil Boatwright (Movie Reporter) "Scorsese somewhat informs us, but then he beats the crud out of us." Holly McClure (Crosswalk) says simply, "If you don't want to see a bloody, violent movie, then don't go see Gangs."

Will Johnson (Relevant) says, "Beautifully shot, wonderfully orchestrated, and skillfully pieced together, Gangs … is an awe-inspiring film. However, before the three hours pass, you can't help but feel betrayed and cheapened." He calls it "gratuitous, lengthy and unbelievable. To say that this movie's conclusion was one of the most disappointing endings of all time is an understatement. I was angry and sad simultaneously." Steven J. Greydanus (Decent Films) also calls it "perhaps the most impressive and ambitious disappointment in this year of ambitious cinematic disappointments. Shakespearean in aspiration, operatic in scope, spectacularly mounted, Gangs … is a remarkable cinematic effort. If only it were about something."

But Steven Isaac (Focus on the Family) says, "I walked away more grateful than ever for my cushy 21st century life. Today we thrive in a society governed by law and order to be envied by all other countries, and this movie makes one immensely grateful for that."

Isaac's sentiments seem to contradict the film's conclusion, which suggests that the rich in America continue to thrive even as they continue to ignore the needs of the poor, both here and abroad. Thus we are forced to consider that the violent struggle between the rich and the poor is not over, and has in fact expanded, causing those beyond U.S. borders to rise up against the wealthy and powerful of this nation.

Coming Home to Ohio: Linford Detweiler on OTR's double album

[This interview was originally published July 30, 2003, at the original Looking Closer website.]

-

On August 19th, 2003, Over the Rhine will celebrate the release of their tenth album by making it a double.

Ohio boasts two full-length discs of new material. And that most astonishing thing is that, after they have played for ten years to stellar reviews, chances are 9 out of 10 that you’re reading this and saying to yourself “Who are Over the Rhine?”

Somehow those who discover the band always come to the same conclusion: “These guys are going to be big.” But they have not yet become “big” in the sense of Rolling Stone covers or MTV or Super Bowl halftime shows.

The fans, when they stop and think about it, are probably grateful. There is something intimate and immediate about the band’s live shows that would be difficult to duplicate in a large arena. But they show no signs of slowing down, and that breakout may yet happen, especially with the catchy new single “Show Me” reaching the radio and euphoric numbers like “B.P.D.", “Changes Come”, "Long Lost Brother", and "Bothered" burning at the four ends of that new double-album.

Perhaps the poetic, discomfortingly honest nature of their lyrics have set them apart as a bit too literary for the fast-food consuming crowd that browses the aisles of Tower Records looking for music instead of listening for it.

But those who care about art, beauty, subtlety in musicianship, the history of American music, and good writing tend to find their way eventually to this band from Cincinnati.

'Over the Rhine' has been the moniker over several combinations of performers, but two names have stayed the same—Linford Detweiler and Karin Bergquist. They're two unique singer/songwriters born in the Ohio Valley that first had a love for music, then found a love of collaboration, and eventually fell into the kind of love about which most great songs have been written. Currently gearing up for a major tour, Detweiler and Bergquist are joined by bassist Rick Plant, who recently toured with Buddy Miller; drummer Will Sayles; and multi-instrumentalist Paul Moak for what promises to be one of the most thrilling live shows ever to take place under the banner Over the Rhine.

I caught up with Linford a couple of weeks after witnessing their tour kickoff concert at the Cornerstone festival in Illinois. We chatted a bit about the festival and its remarkable history, and then got down to business discussing the new project.

A Double-Album?!

Overstreet:

You've certainly been busy writing songs! What did this double-album idea come from?

Detweiler:

I think as far as the turning point, we had been thinking in the studio about which ten or twelve songs are we going to pick to embody this experience of recording and everything that was happening around us, and which ten songs were we going to save for a year and a half later. And that’s what was killing us. I didn’t feel like we could pull 10 songs out.

So I sat down and talked with the band and it just popped into my head—double album. I said it to Karin and Paul. Of course immediately it had the sense of a joke, but a few minutes later we said “Wait a minute!” It just made a weird sort of sense. I called two journalists that I trust just to see how it hit them, one in England and another one here in the States. Both of them were very skeptical at the outset. I mean, “double album”, it just sounds self-indulgent and silly. Both of them had the same reaction that we had. About five minutes later they were too curious to dismiss the idea outright.

We were only really willing to do it if our label would agree to sell it for the price of a single CD. The compromise was that they needed to tack on an extra buck to cover the packaging. Everybody came on board.

It’s our 10th project. It just felt like it might be fun to do something a little different. We’re going to do a special edition on vinyl, in a gate-fold jacket. We’re really excited because we’ve never done a release on vinyl before.

We started thinking about it and thought, well, we can’t really imagine the history of rock and roll without The White Album … London Calling … Exile on Main Street … Songs in the Key of Life. Believe me, there aren’t very many good ones. It’s funny, people are very passionate about double albums. Everyone has a few that they can’t imagine their record collection existing without.

I’m curious to know if we made a big mistake.

Overstreet:

We have both albums on all the time! But I do think the listener might need to take a deep breath between the two parts…

Detweiler:

And I love that you can do that! It’s two fairly digestible records. You can listen to one and then put it away and take a break. I like that more than trying to put fourteen songs onto one cd and having a really long record. It made sense.

For a double album to work, there has to be a lot of variety. There has to be something in each song that is quintessential to the band. It could be just one line in the lyrics. That’s what we went for. It was an intuitive process.

Overstreet:

For the record, Disc One is my personal favorite.

Detweiler:

[laughs] I’ll be very interested in the responses of people who have followed the band’s music regarding which disc they like better. We’ve had a strong number of raised hands in our circle of friends where people seem to love Disc Two. Something started to happen on that CD.

As far as the sequence of what went on the first and what went on the second—I didn’t really think about it that much. We had just finished mixing and I went back to the hotel room and I had to come up with a sequence so the label could hear the record, and that was my first attempt… and we just went with it.

On Disc One, I was thinking of Side A and Side B, like turning the record over after “Ohio”. It felt to me like Disc One is the essence of what we did, and Disc Two is more like… “All this stuff happened too.” But there were too many songs we couldn’t do without.

Overstreet:

You carried a lot with you into this period of songwriting. It’s been a heavy couple of years for you and Karin, with all the unexpected events that took place with Karin’s mother.

Detweiler:

It was a tragic thing that happened out of the blue. Karin’s mother [Barbara] is 69 and she suddenly suffered a devastating stroke that left her in a wheelchair only partially able to communicate. Karin has had to go through this whole grieving process for the loss of a parent. And she lost her father unexpectedly back in ‘94. Of the people in our circle of friends, Karin is the first to have to deal with a lot of these issues. Most of us have not had to navigate that terrain yet.

The good news is that Barbara is well cared-for. She does have some ability to communicate. She is comfortable and is trying to make the best of it.

Karin has weathered it well, all in all. We’re going to break up the tour so she’s not away for more than three weeks at a time. We’ll go home and check in and make sure everything’s okay. She visits her mom a couple of times a week. It used to be several times a year, so that’s good in one way; it’s too bad it has to be in a nursing home. But yeah, she’s doing all right. Thank you for asking.

Karin has really enjoyed getting to know the workers and the residents where her mom lives. Someone described the place as a head-on collision between comedy and tragedy. It’s been heartbreaking and hilarious, inspiring and sobering, you know? It runs the whole gamut in there.

Overstreet:

You frequently mention the value of eavesdropping to a writer. There must be a lot of inspiration in experiences you have there, interacting with the residents.

Detweiler:

When you’re just sort of getting your feet wet there, yeah, there’s a lot to take in. Karin’s been in there more than I have.

One of my first memorable experiences there: a lady wheeled herself up to me and said, “Excuse me, I don’t mean to bother you. I don’t mean to be a burden. I was wondering if you could help me. We gotta get outta here!” [laughs]

With Alzheimer’s patients there’s just this sense of being lost and wanting to find your way back home. One would say, “How do we get back to shore?” Karin has talked about going up to this woman named Geneva [who responded to her by exclaiming “Only God can save us now!”]

It goes back to that metaphor of having ‘ears to hear and eyes to see’… there are these little clues, these little snippets of the eternal that are constantly coming into focus for a few moments and then disappearing. I often wonder how much we miss.

Just from a writing standpoint, there are little bits of interesting language constantly coming at us and we want to take some time to snag things.

Yesterday I was filling up the car with gas, and I saw something on the pump, a little notice that said: The gasoline island is under constant surveillance.

The gasoline island! It was so great.

There are so many cultural and societal movements that would gladly turn us into passive bystanders. I think part of the artist’s calling is to try to rip that veil open and help people keep their eyes open.

OHIO … and the Guy who Kept Showing Up

Overstreet:

Well, the theme of Being Lost and Trying to Find Our Way Home is clearly winding through the lyrics of the new album!

Detweiler:

Good!

Overstreet:

The album is such a journey… like a tour of Dante’s Inferno, with stories about mourning, loss, marriages in trouble, the bruises of abuse. And yet there is so much beauty throughout the album.

I’m curious. You mentioned a couple of other titles that were in the running—Only God Can Save Us Now and then Elvis is King and Jesus is Lord. But you settled on Ohio. Do you feel these songs are all connected in some way to the Midwestern experience?

Detweiler:

We had a number of working titles. We went with Ohio because, over the course of recording this series of songs—I guess a lot of people take a long time to get to this place I’m about to describe—we realized that this music is what we do. And it’s probably not going to go away any time soon. As far as writing and recording songs… I’m guessing we’re going to be doing that for the next twenty years. It felt like we were coming home to that place… that music has a lot to do with why we are here.

We’re finally allowed to just own that without being edgy about it, without being haunted by this feeling that any day now we’re going to move on and get on with our “real lives”, or something more important, or any number of those fears and doubts that sometimes provide a backdrop for the artist. It just felt like coming home.

The very first song we recorded for the collection was Karin’s song "Ohio." She plays more piano on this record. It seemed to be a central song to the project.

In the last couple of years we’ve thought a lot about moving away, and realized that in some strange way this is home and probably always will be. We’ve got great friends here and… I don’t know. It was a simple title and it seemed to feel right.

Overstreet:

And yet, there is this sense of transition throughout the record, a sense of loss and painful change in the world beyond the borders of Ohio. You mentioned that the day you wrote “Changes Come” was the day you turned on the news and saw tanks rolling through Baghdad and Bethlehem.

Detweiler:

Karin wrote the music for that song, and she wrote the chorus hook—“Changes come, turn my world around.” We sat down together and wrote those verses pretty quickly. And then we recorded it in one take: She played guitar and sang and I played piano, and then I went back and recorded the Hammond organ and she started developing the little ‘Karin choir’ in the background.

It was a really cathartic moment for us. There’s this sense of sadness and disappointment that pervaded the recording sessions. On the one hand it was a really joyful time for us, but watching what went down in Iraq and what was going on in the Middle East we had this overwhelming feeling like ‘We’ve got to be further along by now!” There was sort of this sense of helplessness and yet we wanted to stay focused on our work, which was in some ways the most redemptive response we had to what was going on. It gave substance to our beliefs that we live in a world where ideas are more powerful than ‘smart bombs.’

We’ve been thinking a lot about children and, like every prospective parent, the world we’re bringing a child into. Sometimes the only sane response is “Thy Kingdom come”, whatever that means in terms of what we can get our hands on, whatever we can do to push the world in a direction where something like Christ’s Kingdom makes sense.

Jesus kept turning up on this record. That can be a little bit problematic when you’re trying to do your work. We were recording songs, making a double album, and Jesus kept turning up. But we were up for it.