My Box of 64: Episode 2 - Mischa Willett & the power of practice

On the second episode of the new Looking Closer audio journal, My Box of 64...

I welcome poet and Seattle Pacific University writing instructor Mischa Willett to talk about why he gave up on entering poetry contests, to share why he memorizes his favorite poems, and to read poems from his new book Phases.

Also, another "Letter to Thomas."

And a response to a question from a reader: How do you know if you're a writer?

Join me for another program exploring creativity, conversation, and community.

Don't Think Twice (2016)

Don't Think Twice? Do watch once... or maybe even twice.

Writer/director Mike Birbiglia's 2016 comedy — perhaps better described as a 'dramedy'? — has a modest goal: to dramatize the struggles of talented comedians working together to keep their dreams alive. Seems simple enough, right? But think about it: How many movies about comedians have you seen that were both funny and convincing?

Don’t Think Twice is remarkable for so many reasons. Its cast of collaborative characters convince me that they are working comedians, each with unique troubles that fuel their comedy, each with creative aspirations, each committed to the collaborative magic of improv, and each capable of restraining their substantial egos in order to make a corporate effort work. The movie springs with agility between their highs, lows, and late-night performances. And it avoids predictable formulas...

... except for this: the familiar debacle of "The Theater That Is Being Closed Down." It's a tried and true American movie formula. "The Man" is shutting down the show. Can the performers hold on to their magic, their relationships, and their dreams? Still, there's nothing wrong with a formula if it's invested with passion, particularity, and imagination. And Don't Think Twice pushes the pending closure aside so that it's just a dark cloud over a far more pressing dilemma: What happens if dreams of stardom (in this case, places on the legendary TV show "Weekend Live!") start coming true anyway... but only for one of them? Will the subsequent surges of jealousy, suspicion, and unspoken grudges sink the whole ship of the troupe's long-running enterprise?

Even when Birbiglia's intertwining storylines do take predictable turns, somehow he finds the most discomforting way possible to make those turns. And yet none of the anxiety or awkwardness feels forced. We find ways to care about each member of the team, even when we see them at their worst.

What's more, the movie doesn't feel like it's been made with any bitterness toward those who become famous. Rather, it reflects lived-in wisdom about the struggle to succeed. Contrary to popular belief, fame — the movie seems to say — is often just as costly (if not more so) for the person getting the big break than it is for the dreamers who jealously watch him go.

Another lesson: Be careful what you wish for. A role on a famous TV show might subject you to the whims of a cruel and unusual show-runner whose business savvy requires suppression of anything like a human soul.

For all of these virtues, the script is just the tightrope that Birbiglia has set. The movie's real magic comes from those who perform so persuasively all the way across it. Birbiglia's got himself an excellent ensemble, featuring Gillian Jacobs (Community), Keegan-Michael Key (Key & Peele), Kate Micucci (Garfunkel and Oates), Tami Sagher (30 Rock and How I Met Your Mother), and producer and writer Chris Gethard. And then there's Birbiglia himself in a self-effacing turn that's both sympathetic and infuriating. Before it's over, the movie serves up a startlingly substantial celebrity-as-himself cameo that somehow rings as true as anything in the movie.

Having said that, I did feel there was one thing missing here, and that comes from my own experience in an improv comedy band and in a community that includes accomplished improv comedians. I miss the joy that improvisers know when things really work, when the performance takes on a life of its own, when the comedy blows up into something bigger than any of the performers anticipated. That is a high unlike anything else in the world.

Don't Think Twice focuses primarily on the challenges and awkwardness involved when one person achieves a success that the rest of them dream about, and thus it becomes a drama fraught with angst, insecurity, anger, and heartbreak. That's all very, very well done. But it would have been that much more convincing if I'd seen more of the giddy highs that make "Yes, and—" exercises so addictive and rewarding.

That's just a quibble. Don't Think Twice seems like a small wonder, until you zoom in to see just how much Birbiglia and Company are accomplishing. I'm so glad that friends spoke so highly of it, so that I went after it even after the season of year-end lists and Oscar assessments had passed. Don't let this low-profile highlight get away.

Man... I have such huge admiration for people who stay committed to lives in the theater even when their wildest dreams don't come true. It's a rough vocation, and a difficult one to pursue humbly and with a generous spirit. But I know people who do. They rarely get the ovations they deserve, or the credit for all of the other hard work they must do to stay afloat.

My Box of 64: the new Looking Closer audio journal!

Before the big announcement, some background...

When I was a kid, a big box of crayons with a sharpener represented, for me, full creative potential. It heightened my heart rate. It inspired adrenaline. It made me want to make stuff.

But, on my family's budget, it was too expensive — especially when we already had some crayons and colored pencils in the house. And so, that super-sized set came to represent something just out of reach: the capacity to bring all of the colors to life.

I can hardly complain. That creatively ambitious kid grew up to have more than his share of opportunities to do creative work and share it with the world. This year marks the tenth anniversary of my first two books: the novel Auralia's Colors, and my memoir of dangerous dangerous moviegoing Through a Screen Darkly. Having been granted those unexpected, unlikely opportunities — and the subsequent publications, speaking opportunities, and teaching work — I live in a state of perpetual gratitude. What's more, I'm blessed with a creative, supportive community.

But I'm not interested in looking back and settling for nostalgia. Any opportunity I've had to tell stories, write reviews, edit other people's work, publish, speak, and teach has felt like practice for the next thing.

So I'm still reaching — wanting a chance to share more stories and bring new ideas into the world. In recent years, increasing pressures and troubles have forced me to postpone or give up on a variety of dreams and projects. I lack the resources, the connections, the opportunities, and the time — especially the time — to realize my creative visions to my own satisfaction. (There won't be more novels anytime soon unless I find the kind of work that makes a project of that magnitude possible.)

Meanwhile, all around me I see vibrant, creative people struggling to make ends meet and fighting to keep their own artistic visions alive, hoping to bring light into a darkening world.

So I've decided to start something new. Something creative. Something that I can manage in the midst of a difficult and demanding schedule.

I call it...

This opening episode begins with a long introduction: a letter that I've written to the most mysterious person in my life.

Then, I welcome a special guest.

And that's just the beginning.

Moving forward, you'll find the episodes become unpredictable. I aim to misbehave.

It will be fun. I'll host interviews with special guests about their own creativity. I'll do some storytelling — glimpses of new and unpublished fiction. I'll share poetry readings — in my voice and in the voices of the actual poets. I'll premiere new music from musicians I love. I'll review movies (of course). There will be conversations about artmaking, about the writing life, and about how to keep hope and creativity alive. There will be discussions and debates about movies. And much, much more than that.

I hope that this new Looking Closer audio journal — My Box of 64 — will provide for you some creative inspiration. I hope it will introduce you to exciting new art, artists, and ideas. And I hope it will prompt you to share with the rest of us the work that is inspiring you creatively.

Here's how you can be part of the show:

Follow My Box of 64 on Twitter, and engage the conversation there. Selections from those exchanges will become part of upcoming episodes.

•

Follow the Looking Closer with Jeffrey Overstreet Facebook page, where a lot of My Box of 64 updates, previews, surprises, and opportunities for listeners to participate will be posted.

•

Add MyBoxof64@gmail.com to your contacts. Why? You can send emails to ask questions, share anecdotes, and recommend music, books, movies, poems, paintings, and more — anything that might be worth reporting in an upcoming episode. I'll share selections from what I receive there.

•

Check out new music by Robert Deeble at PledgeMusic.

•

And so it begins... a new Looking Closer adventure. What's in your box of 64? I hope you'll share it with me.

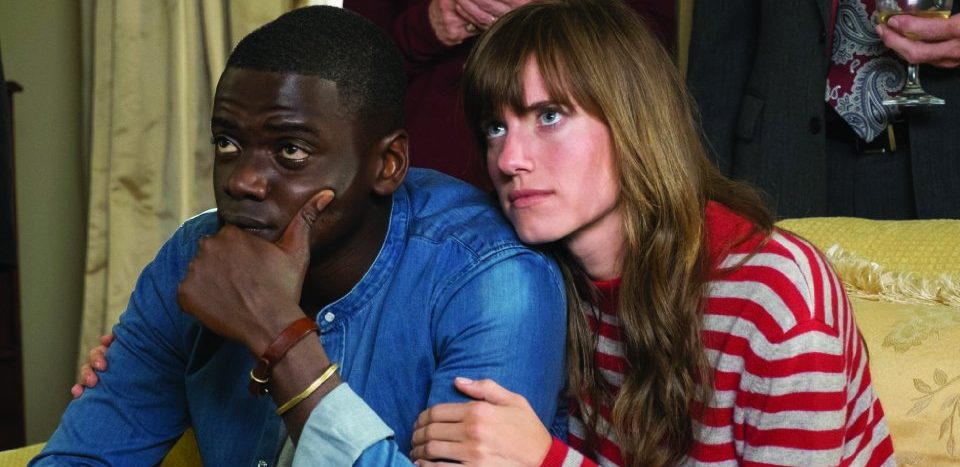

Get Out (2017)

Earlier this month, my students wrote film reviews of Ava DuVernay's film Selma.

I pulled sentences from each of them and projected them onto a screen, asking the class to help each other repair grammatical errors in some of the weaker sentences. (This is a great exercise. The class wakes up because the broken sentences might be their own. It becomes like a contest, each student striving to discover the best fix for each problem.)

One of the sentences was missing a semicolon.

But one of the students said, "I see a bigger problem than that. The writer makes a reference to how she is learning to empathize with 'the African American community.' It would be so much better if she said 'African American communities.'"

I nearly choked, I was so startled. I had been so focused on grammar and punctuation that I had overlooked a far more important issue. In a review reflecting the writer's respect for the Civil Rights Movement, the writer had committed a faux pas that I am almost certain I've committed in the past, reducing a complex population into an unfair generalization. Yes, there are as many kinds of 'African American community' as there are kinds of 'Caucasian community' or 'Christian community,' and by bundling them all into one perceived culture, we can — with the best intentions — make our problems worse.

I admit it — even though I'm on a minimum-wage income as an adjunct university writing instructor, I'm among the most 'privileged' populations in the world. I'm a white, middle-class, American male. No matter how much I embrace ideals of equality, liberty, and justice for all, I can't escape my past. I marinated in my community's racial and cultural ignorance and self-righteousness.

Perhaps if I had read my student's paper more closely, I would have seen the problem in this sample sentence that needed the most urgent attention. Perhaps not. Whatever the case, I was more a student than a teacher in that moment when an attentive student — yes, an African American — took the rest of us to school on a hurtful complication in the composition at hand.

I felt this way again and again and again through the first hour of Get Out, the directorial debut of the extraordinarily talented Jordan Peele (of Key and Peele). It's probably better categorized as a thriller than as a horror movie, but it was horror that I felt as I recognized the behaviors of the villains in this film, even as many in the theater around me laughed in recognition, clearly familiar with such misunderstanding, disrespect, and abuse. Peele comforts the afflicted whose experiences correlate with those of its protagonist, and he afflicts the rest of us, the comfortable, who often perpetuate racist behaviors and vocabularies even when we have the best intentions.

The first hour of this movie follows Chris Washington and Rose Armitage, a young couple who spend a catastrophic weekend with Rose's white and wealthy family. Chris (played by Daniel Kaluuya) is black, and Rose (Allison Williams of Girls) is white — and Chris is anticipating problems in when he meets the parents. Rose quickly dismisses his concerns.

But when they arrive at the Armitage homestead, even the family's most flamboyant and boastful claims of progressive values — they would have voted for Obama if he could have run for a third term! — cannot conceal the remnants of racism in their language and behavior. And even more disturbing than the obvious, lingering forms of cultural prejudice are the self-righteous and self-congratulatory displays of support for Chris as a representative of "the African American Experience." Chris has to grin and bear it as the mere fact of his arrival has white people declaring their admiration for Tiger Woods.

The second hour takes wild twists and turns as the Armitages' community descends upon the homestead for an annual party, exponentially increasing Chris's challenges and troubles. The bizarrely condescending nature of this community confirms our suspicions of wickedness at work, but confounds our expectations about what shapes the evil might take.

I could easily spend the rest of this review lecturing about the importance and timeliness of movies like this. But I'd rather not, if only because I almost skipped Get Out for that very reason. Don't get me wrong — I know the need for prophetic, truth-telling art. But I must admit that when I want to head out for a few hours of escapism and imagination at the movies, the last thing I'm looking for is yet another lesson in the obvious.

I'm up to my eyeballs in editorials, essays, and books on the ongoing reality of racism in America. I read it in the news, I see it in almost every move that the Trump administration makes, and I see alarming harm in the lives of my students and my community. I read authors like Eula Biss and Claudia Rankine in eagerness to discover how I've been conditioned in cultural racism since birth. Why? I want to believe that I study these things because I take seriously Christ's desire for me to love my neighbor. But it's also likely that I'm more frantic to avoid the appearance of evil and to distance myself from the crimes of my cultural heritage than I am to actually achieve holiness.

And it's because of that doubt about my own intentions that I think it's best for me to back off from sermonizing. These are lessons I would do better to receive than deliver.

And besides, I'm delighted to report that, while the buzz about its "cultural relevance" was valid, the accomplishments of this film on almost every other level of filmmaking craft are substantial. Bring on the future of Jordan Peele cinema! The man can write, and the man can direct. The meticulous pacing, the precarious and precise balance of its discomforts, the ingenuity of its premise, the (sigh) timeliness of its social commentary — these are all commendable. But most impressive of all — Peele clearly has a fantastic gift for directing actors. Get Out is a near-miraculous triumph of ensemble acting.

I have a hard time imagining this movie working with a different cast than this one. Everyone is so perfect for their roles, demonstrating remarkable complexity.

Be warned: What follows in this review contains moderate spoilers. I'm praising this film more for readers who have seen it than for those who haven't.

Bradley Whitford's knack for horror-movie roles surprised me in Cabin in the Woods, and as the mad genius Dean Armitage — Rose's father, who immediately embraces Chris with such fervor that we are immediately suspicious — he impresses me even more. In fact, this performance reverse-engineering his West Wing work so that his Josh Lyman character now seems far more intelligent than he once did, and far more capable of steering a presidency in dangerous directions.

Catherine Keener proved her capacity for unsettling audiences way back in Being John Malkovich, and she does it again here by backing away from her tendency toward hard-edged flourishes. She's subterranean here, a malevolent spider luring prey into her web. She plays Missy Armitage, Rose's mother, as half-doped on sleeping pills, dwelling in some "Sunken Place" of her own where monsters dwell. (Perhaps that's because she apparently waits up all night in the dark, hoping some unsuspecting visitors will stumble within reach of her powers.)

Allison Williams's go-for-broke performance is brilliantly convincing even if her character, as written, is as close as the film comes to a storytelling cheat. She makes Rose into a beauty both alluring and menacing. As the film progresses, that spark of audacity and danger in her eyes intensifies, and eventually we understand why. She's like Kellyanne Conway 30 years younger — before the compulsive lies and appetite for destruction became so obvious. She's all teeth and jaws and flaring eyes, like some cross between Amanda Peet and an Anglerfish.

The supporting cast earn their screen time by making priceless moments out of their characters' important contributions. Stephen Root (always magnificent), Marcus Henderson, Short Term 12's Lakeith Stanfield, and especially Betty Gabriel — I can't say enough about all that they accomplish in their limited screen time.

But highest honors go to Daniel Kaluuya himself, who says so little aloud, and yet is able to perform such a broad range of emotions and bewilderments. There are several scenes here in which he makes long journeys, thinking through the implications of the behaviors and mysteries all around him, and he doesn't say a thing. He's a maestro of reactions, double-takes, self-control, and telltale twitches. I can't think of a performance in any fish-out-of-water story that drew me more powerfully into the protagonist's misgivings, angers, and fears. As the situation becomes increasingly far-fetched, so Kaluuya's performance becomes more and more impressive; thus, I remain emotionally invested in his progress of solving the mystery and, well, getting out.

I do wish that the revelations of the last act were clearer. The amount of exposition necessary to help us understand the full extent of Peele's sci-fi ideas is, well, distracting... and unsuccessful. I never fully figured out how the villains' conspiracies worked until I started digging deep into post-viewing debates among viewers who had clearly seen it more than once and become somewhat obsessed. (I'm delighted, though, to discover that the villains' motivation has less to do with race than it does with a lust for immortality — even though racism gets more play).

Nevertheless, the cast did more than just suspend my disbelief. When the focus was on their nuanced, exquisitely crafted performances, they had me gasping for air and cringing through a wild variety of discomforts. As the film's storytelling wandered too far into the weeds and got too tangled for this viewer's tracking, they kept me caring and hoping for a dozen different resolutions, only one of which occurred, sending me back out into the night jumpy, twitchy, anxious, upset, and yet buzzing with the rare experience of having been completely absorbed by a horror film.

I'll leave any further commentary on Get Out's cultural relevance for others who can speak with more authority and wisdom than I can. Besides, if I narrow my consideration of this movie to those issues, I am doing this movie a disservice. Get Out is worth seeing in a theater for more reasons than the urgency of reaffirming America's commitment to "liberty and justice for all." Jordan Peele has just proven not only that he is an important voice in a time of a national identity crisis, but that he also knows how to craft an edge-of-your-seat thriller.

Song to Song (2017)

First, a rant about one of my least favorite words:

I've asked my students to stop using the word "relatable" in their art criticism papers.

It's not a bad word. (There is no such thing as a bad word.) Used skillfully, every word has its place. But I've noticed that students who haven't written about movies before often show a preoccupation wth a movie's emotional accessibility. It's as if a movie is only as valuable as its emotional "impact" (there's another word I ask them not to use) on them.

But aren't movies about more than feeling? Don't well-made films engage our intellect as well as our heartstrings?

"Relatable" means "able to be related to something else," or "enabling a person to feel that they can relate to someone or something." So when a student, writing about movie, calls it "relatable," what they are usually doing is making a leap from "I found that I could relate to something in this movie" to the presumption that "This movie is, thus, relatable." That's a questionable assumption. If a movie makes me feel something, can I assume it will have the same effect on you? And even if it does, well... what good is that? We are fickle creatures, and our emotions can flare up easily if someone pushes the right buttons. Does that automatically mean that the cause of those emotions is praiseworthy?

In a general sense, almost any movie is relatable in that almost every movie is about human beings, human experience, human expression, and human creativity. Thus, to write that a movie is "relatable" is to say almost nothing of value. It is so nonspecific that it wastes space.

We should also remember that one of art's greatest powers is its capacity to draw us beyond the sphere of the familiar. If I only focus on art that seems immediately and clearly relevant to my present circumstances, I'll box myself into a small and unsurprising world of self-affirmation.

So, that is my rant. And it is, believe it or not, just a preface for what I'm about to say regarding Terrence Malick's new film Song to Song.

•

For all that I have just said, questioning the importance of finding a movie "relatable," I have to admit that there was only one moment in Song to Song, Malick's eighth dramatic feature, that commanded my attention when I first saw it. The moment caught me up out of a sort of half-bored contemplation of glamorous actors (everywhere!), creative cinematography (every single shot!), and my own increasing frustration with Malick as a director (his movies so far this decade are all starting to feel the same, their sense of redundancy increasingly blunting their effect).

And the moment that got my attention, that drew me suddenly and completely into the movie, did so because it was, for me, yes... relatable.

In fact, I choked. This particular scene caught me off guard precisely because I recognized it. I related. I'd lived it. I saw a character's heart breaking in a scenario so similar in every way to my own experience of loss that I almost had to look away. As a man stood staring in disbelief, asking his lover questions that he didn't want to ask in order to hear the answers he'd dreaded hearing, I felt a sudden pressure, as if a massive storm front were rushing in over the theater and obliterating a blue-sky day.

It wasn't because the characters were interesting.

Like most men and women in Malick's recent films, the characters in Song to Song reveal so little about themselves that they are little more than ciphers. They're a selection from Hollywood's It-List, beautifully dressed, meandering about open spaces, and wistfully spouting meditations so devoid of particularity or character that it's like the actors were given their lines on fortune-cookie slips, told to read them whisperingly into a microphone, given a paycheck, and sent home for the day.

But here was something that rarely happens in Malick movies anymore: a substantial conversation that serves as a turning point in the plot. Maybe that had something to do with why I found myself sitting up straighter. For a few moments, someone asked questions... and someone had answers.

And then it was over, this crucial, plot-turning, life-changing exchange washed away by waves of wistful interior monologue, carrying us back into the perpetual motion, perpetual emotion, perpetual light shows, and perpetual introspection that have become Malick's modus operandi.

My emotional seizure subsided. The movie played on, and I felt only half aware of it, the rest of my attention now tangled up in the memories that the moment had unlocked.

So, I'd found a relatable moment. And its effect was to underline just how ephemeral and distant the rest of the movie seemed to me.

•

Song to Song is the fourth film in Malick's deep dive off the mountain of prose into the something that looks like poetry (even if the narration is too simplistic to sound like it). Brett McCracken at Christianity Today recently called this series "cinematic wisdom literature." And sure, there's wisdom in these reflections on love and lust. There are Biblical allusions. We can write pages and pages on the nature of love, innocence, temptation, and sin based on the equations of love's simple algebra being acted out before us.

It's just a shame that these parables, these stories of pilgrims and progress, are so moralistic and heavy-handed, and that these movie stars aren't given characters substantial enough to make me forget I'm watching Ryan Gosling pretend to have chemistry with Cate Blanchett. (Ouch, what a lifeless mismatch.)

It's hard not to get caught up in the trending arguments about which "New Malick" films are masterpieces and which are self-indulgent revels. When I saw The New World, I felt I'd seen a new kind of movie invented; its balance of "poetry" and "prose," grounded more in history and particularity than anything since, worked so perfectly for me that I saw it six times in the theater and went on to purchase every edition in every format. I could hardy contain my excitement for what was to come. Then came The Tree of Life, which aspired to greater things, but left me with an unsettling sense that Malick was beginning to repeat too many maneuvers.

And I was right to be unsettled. While the light has remained dazzling throughout To the Wonder and Knight of Cups, too much has seemed derivative of past epiphanies. It's as if Malick's movies have become not only increasingly interior, but increasingly withdrawn from the world. As Lubezki's magical cameras bring us closer to glamorous celebrities than we've ever dreamed of being — his cameras almost fly right down Rooney Mara's throat during one crazy black-light sequence here — I've never felt more distant from characters played by any of these fine actors.

Your mileage may vary, as they say, but Song to Song amounts to only a few of the things that I love about Malick and way, way too much of all the things I don't. It has all the narrative subtlety and sophistication of a Chick tract. How I'd love to see Malick shift to other people's scripts now, or literary adaptations — something with some meat on its bones.

After those moments of mid-film crisis, the movie never drew me back in. It just kept me busy looking: Looking at beautiful light, beautiful architecture, beautiful faces, beautiful composition, and, oh... those beautiful people. Malick seems capable of casting whomever he likes and turning them loose on his boundless dance floor, where they come together to spin, twirl, weave, embrace, caress, tumble, separate, glare, and scatter.

This time around, the basic plot outline — which is all we really get (there isn't enough detail for me to call it much of a narrative) — follows a manic punk-sy dream girl played by Rooney Mara (the credits call her "Faye"), the boyish musician who wins her heart (Ryan Gosling, playing a minimalistic, jazz-free version of his La La Land character that the credits call "BV"), and the producer (played by Michael Fassbender's predatory grin) who exploits them both with all the subtlety of a comic-book supervillain so that he can keep, as the Bible would say, "know" Faye.

Before it's over, they'll all take tumbles with other lovers (Cate Blanchett, Natalie Portman, and Bérénice Marlohe) who get to live out their Vogue's Hollywood Issue dreams, looking more alluring than they ever have before in long sequences of teasing, foreplay, and — here's a Malick first — orgies.

I'm not sure how the residents of Austin, Texas, feel about this portrait of their town. The place has never been given such glorious, panoramic attention, and I doubt it ever will again. I feel like I know the place now, from the mosh pits of rock festivals to the high-rise balconies of the rich and famous. Here's a movie in which the scenery is much more interesting than the movie stars moving through it — until we're blessed by this Malick movie's version of a priest: punk rock high priestess Patti Smith, who gives the movie some fleeting moments of being grounded and almost believable. I suspect that her dialogue is unscripted; it sounds like it's based in lived experience. And it sounds, refreshingly, like a genuine human moment.

The only other sequence that compares comes when Cook (Fassbender) steps away from Rhonda (Portman) and the prostitute who, it's implied, recently completed their threesome. This character seems like a fully developed human being with stories to tell and scars to reveal. For a moment, I imagined a "New Malick" movie fulfilling the potential shown in The New World and The Tree of Life to further navigate trails blazed by Wim Wenders in Wings of Desire, giving us the real sense that we're descending into an actual city, where the figures we see have complicated histories and lives.

But no, the camera is too committed to riding the emotional jetstreams streaming between the high court of Hollywood royalty. And that's a shame, because all I see are Mara, Gosling, Fassbender, and Portman emoting. All I see is a pageant of "love moments" (to borrow a phrase from the movie) so general that, while they may be relatable, they're the farthest thing from interesting.

All of this time spent meandering in their company "reveals virtually nothing about any of them," says Mike D'Angelo in Las Vegas Weekly, "even though the leads—as is the case in every Malick film—continually relay their innermost thoughts in whispery voiceover. Replace the entire cast with catalog models and the movie would play much the same, and look far more honest."

It's easy to find oneself daydreaming about films in which these actors inhabited compelling stories. As the credits rolled, I wanted to go watch Carol again — just to see Mara play a character I believe in, and to see Blanchett find some actual chemistry with her supposed love interest.

"I took sex, a gift — I played with it," confesses Faye in one of her many spells of stating the sledgehammerly obvious. But do we ever hear her play a song? She is a musician, after all, and this is a movie about how she got lost in the business. Do we ever get a sense of the music she's so eager to share with the world? No. We hear fragments of Patti Smith, of Bob Dylan, and whatever band allows Val Kilmer to carve an amp into fiery pieces with a chainsaw.

Call it La La Languish. Maybe you'll find it relatable.

Silence... like you've never heard it before.

Those mysterious people at Image Journal have just dropped the trailer of the century.

https://vimeo.com/210654913

If you loved The Secret of Kells

For the grand finale of my film-focused research writing course at Seattle Pacific University, I treated my finals-weary students to a screening and discussion of The Secret of Kells. I didn't even realize until I was loading up the movie that, lo and behold... it was St. Patrick's Day. And so, another audience fell in love with one of the most extraordinary animated movies ever made.

The Secret of Kells becomes more precious to me every time I see it — and every time I listen to the soundtrack. And I've watched the follow-up film, Song of the Sea, become a favorite to so many moviegoing friends.

So my pulse quickens watching these teaser videos for Wolfwalkers. Tomm Moore and his amazing Cartoon Saloon team are making magic again. Thanks to Ken Priebe for bringing this to my attention soon after it was posted today!

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fZdv_f9f5Jo

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_NW2QZJSglQ

Embracing dangerous neighbors in Of Gods and Men

I recently posted a review of Martin Scorsese's Silence that was written by a high school student who took my online film course called "Viewer Discussion Advised."

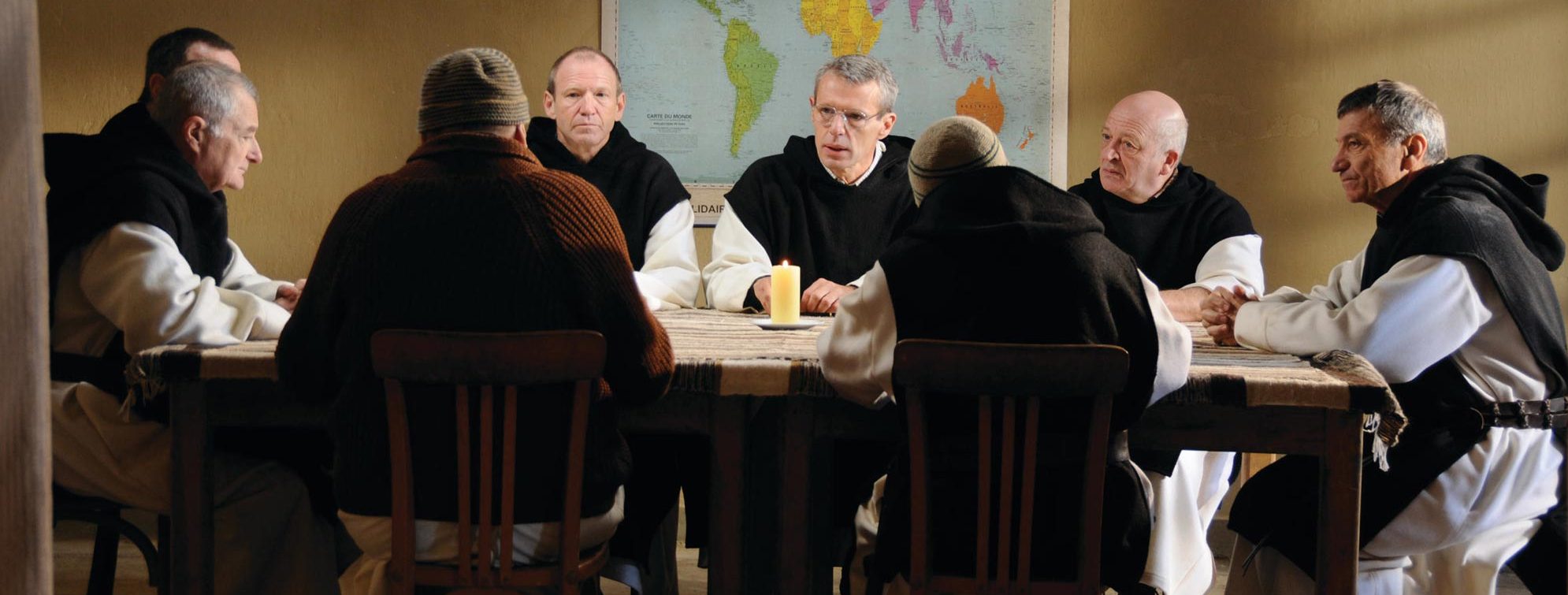

Today, I'm sharing another review by a first-time film critic who took that class with me over seventeen weeks. Her name is Martha-Grace Jackson, and she's in eighth grade. She watched a film that I doubt many eighth graders have seen — an extraordinary drama about Trappist monks in Algeria: Of Gods and Men, directed Xavier Beauvois. And if she writes like this in eighth grade, well, I will want to see what kind of reviews she's writing when she finishes high school. (I've done only a bit of copyediting here for this publication.)

In Xavier Beauvois’ film Of Gods and Men, eight French monks must decide whether to leave the war zone they live in and return to the safety of France, or to stay with the people in their village who cannot leave. Will they return to France to save their own lives and leave the people behind? Or will they stay and continue to aid them?

Their village is an Islamic terrorist war-zone in Algeria, and the government there is not helping much. The monks provide medical and physical care for the people living in the village, many of whom are refugees. The monks are Christians, though the people in their village are an eclectic mix of religions, many of which are Muslim. Part of the monastery is a hospital and brother Luc (Michael Lonsdale) is a doctor, probably the only doctor in the area. Their leader, Christian (Lambert Wilson) is of the opinion that they should stay and many of the other monks are unsure. The monks believe that there are more ways to beat the terrorists than by killing them. They continue to minister to the people despite opposition and danger.

The screenplay is simple and the only music you hear is that of the monks chanting. All of the Algerian scenery portrayed is beautiful and calm. True to the time and events, the costumes are simplistic. The uncomplicated nature of the film places the viewer in the monks’ place to see the situations through their eyes. The movie’s minimalist approach achieves the aspect of truth in the movie.

The film, which is beautiful in many ways, is sometimes hard to follow and difficult to grasp. (I am sure it would be easier if I was a native French speaker.) The portrayal of the government in particular is confusing because the monks are in opposition to it in certain ways but in other ways they seem to be in agreement.

The movie emphasizes the impact for good that empathy can have and the impact for evil that violence has. The ways in which the monks empathize with the people are unusual; they ask for no payment or recognition, and they work for Christ and not for other men. They also empathize with the terrorists and are sorrowful when their leader is cruelly killed by the government. There is more than one way. Violence is not the only or the best way to combat evil.

If I was in the situation that the monks were placed in, I would be sorely tempted to return to the safety and comfort of home. Many people would probably tell me that that was a good decision and to care for myself above all else. The film was inspiring to me because the monks were selfless and humble. They cared so deeply for the people, more deeply than they cared for their own safety and comfort.

This film is a meaningful, inspiring picture of Christ-like love for others. The monks lay down their lives for the people. I would recommend this movie to people, but tell them to come to the film with an open mind and to wisely consider the monks’ actions.

Martha-Grace Jackson is an eighth grader from Charlotte North Carolina. She is child 2 of 7, a serious violinist and pianist, teaches some young students, and enjoys studying Greek and Latin. She also enjoys crafting, listening to podcasts, and reading fantasy fiction.

Q&O: What should I see this week?

Q:

It's the post-Oscar-season slump, when studios typically dump their trash into theaters. If I have an itch to go to the movies, what rates as something better than dumpster diving?

O:

You're right — a lot of "leftovers" are wasting space on the big screen right now. But take courage! You can make good use of your moviegoing time.

Teaching classes at four schools, I'm finding it hard to make time for this March moviegoing madness. But I'm glad I saw The LEGO Batman Movie. (Here's my review.)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rGQUKzSDhrg

I liked A United Kingdom, mostly because the two lead actors elevated rather mediocre material. (Here's that review.)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pX5vI4osR50

If you haven't had a chance to see I Am Not Your Negro, make the time. It is an extraordinary experience, and it's meaningful to celebrate the prophetic voice of James Baldwin with a moviegoing community. On the big screen, the subject gets the honor he deserves. I haven't reviewed it yet. Why? It demands substantial attention, and I get emotional when I think much about it. So I'm looking for a window of time in which I can do the subject justice.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rNUYdgIyaPM&t=1s

More recent releases — I've heard great things about Get Out, and I cannot wait to see it! I've heard mixed reviews for Logan. And you'd have to pay me some good money for me to spend any time watching Kong: Skull Island or The Shack.

But the movie I'm most excited about seeing in a theater this month? Kedi.

https://vimeo.com/152779982

Reflections on Scorsese's Silence

I've been teaching a 17-week online film course for high school students. My students read Through a Screen Darkly, keep reading journals where they respond to what they read, participate in a private Facebook group discussion about film interpretation, watch a wide variety of movies, and write reviews of them.

One of my students, Carly Anderson, made a special request for her final film review. Even though she watched one of the assigned films along with her classmates, she also went out to see Martin Scorsese's film Silence, and she was inspired. Could she write about that instead?

I was delighted by her enthusiasm. I was even more pleased with what she turned in.

So, with her permission, I'm sharing this — her passionate paper on a difficult film, one that made a strong impression on her.

•

清、この夜、ほしは、光

(kiyoshi, konoyoru, hoshiwa hikari)

This is the opening line to “Silent Night,” in Japanese, and I will never forget singing it with faltering words to a room full of small Japanese-American children after a Christmas church service. Something settled into my heart that night as I tried to carry on conversations in a language that struggled to roll off my tongue. I stood at the head of a small community room with a few of my other nervous classmates, a worn-out hymnal in my hands, and watched as a room full of Japanese Christians smiled and moved their lips along to the beloved words. Makoto Fujimura’s book Silence and Beauty was weighing heavily on my mind and I could not help but see this tranquil scene through a lens of sadness for the “mud-swamp of Japan.”

This year I have been taught by a Japanese pastor and his wife who are trying to teach Japanese children about their heritage, both Christian and Asian. They also run free classes for high school students where they teach Japanese through the lens of the Bible. Much of our vocabulary has come from books full of hymns and Christmas carols. I am constantly amazed by this couple; their self-sacrifice for their community, their bravery, and their love for Christ are inspiring to say the least. Unlike many of their countrymen, they have accepted the gospel of grace, a gospel so difficult for their people, and internalized it. It is because of them that Martin Scorsese’s Silence (沈黙) affected me so deeply.

My friend and I sat in tearful shock as we watched the film. Expecting the normal credits and opening soundtrack, we were greeted with severed heads, Christians being tortured with boiling water, and absolute silence. A despairing priest, Father Ferreira, speaks into this awful scene, saying he has not abandoned the faith, but even as the words are spoken, he falls to his knees in the mountain ash with nothing more to say.

When word reaches Portugal that he has apostatized, renouncing God in public, his two students, dedicated Jesuit priests like himself, follow in his footsteps. They set out to bring the gospel to “the ends of the earth” and rescue their despairing mentor. With a desperate Japanese man named Kichijiro, who has renounced his faith to escape death and watched his family burn for their God, they enter Japan in secret to bring hope to those who continue their faith alone. They have no idea what awaits them.

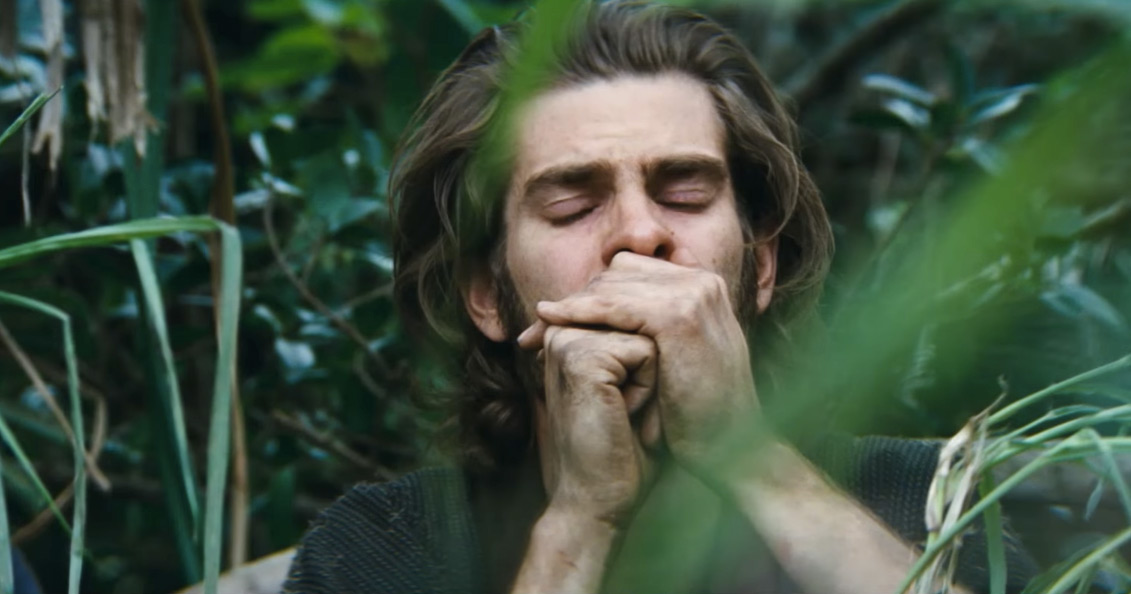

The acting was unlike anything I have ever seen. I did not feel as though I was watching a movie or even a documentary. I kept tearing my eyes away from the screen and glancing around the darkened theater to convince myself that I wasn’t in Japan. Andrew Garfield’s performance left me speechless and spellbound for I was entirely convinced of his sincerity.

The movie was visually ingenious. It irrevocably convinced me of Scorsese’s brilliance. The beauty of the setting stands in stark contrast to the horror of the story. The screams of the burning, the drowning, and those whose blood soaks the earth are the only soundtrack, filling my mind as I watched. It felt as though I was watching a mental war. Because we had studied the language, my friend and I could understand every word the Japanese Christians were screaming, even the words that weren’t subtitled. Their desperate pain and faith tore at my heart, posing a thousand horrible questions. Is there salvation after you renounce your God? Can you still love Jesus and publically proclaim that he does not exist? How many times can you fail and betray what you love before forgiveness runs out.

This is not a film of pat answers and easy morals. It does not present heroes who have all the answers, only dedicated men who risk everything to enter a hostile Japan. It is difficult and straining, but that does not mean it is without hope. Father Rodrigues, the main character, commits his greatest sin during a frenzy of compassion, unable to endure the groans of his fellow Christians who are a bleeding and screaming in the service of a God they have already rejected. He is a kind man who rejects Christ to save the suffering. His guilt consumes him and his compassion is erased by despair as he is forced to do the work of his enemies, but his mission is not fully ended and the faithful of his past and future become a quiet mission. His companion, Father Garpe, may have been stronger and more fiercely dedicated, but his trials were not the same. Father Garpe’s body was assaulted and his limits were tested, but the Japanese set out to destroy Father Rodrigues’s mind and faith.

What would we do? The answer is unclear. In this dizzying movie the strong become weak and see their own frailty, while the weak find the strength to die for the faith that will not let them go. After the silence has been endured, when Rodrigues can hear the voice of God again, it seems that grace has not entirely forsaken the lost. It seems that his greatest moment of weakness is when he hears the voice of Christ most clearly.

Much like Japan’s culture, this movie is a swamp of symbolism, confusion, and unbreakable faith. Of the 200,000 Christians in Japan during the Edo period, at least a thousand were martyred and many of the rest died in hiding, persecuted and poverty stricken. They died for a symbol and no answers were given, but even in the silence there was light.

Perhaps it is true that Christianity cannot take root in Japan, but even in the last moments of the movie as the murmurs of the Buddhist monks filled the air, I felt a strange sense of surging hope for a country that may not remain as it is forever. The movie’s final image is burned into my mind because it is an image of faith in brokenness, worship after failure, and trust after denial. Perhaps Peter felt the same way on the night Jesus died. He had failed in his faith and denied his savior but even as the sound of the rooster’s crow echoed in the air, Peter became the cornerstone of a new and faithful church.

Perhaps, even in the “mud-swamp” of Japan, the gospel of Christ will someday take root. Even through failure and despair and human weakness, it will reach into this “Silent Night” at the very ends of the earth and bring light to a desperate people. I have seen Japanese people accept grace with my own eyes. I have seen their kindness and open bravery and, even in the silence and trauma of their past, I have watched them begin to sing.

•

Carly Anderson is a high school senior from Charlotte, North Carolina. She is a historical fiction enthusiast, an obsessive writer, and an amateur musician. On the side, she quotes “The Princess Bride," reads Japanese comic books, and makes amazing guacamole.