The Breadwinner's gun-wielding coward

Nora Twomey's Oscar-nominated animated film The Breadwinner is now streaming on Netflix in the U.S.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yQBQw-Bh1pg

And I am so glad. The timing of its streaming debut was perfect for my teaching plans this week.

I teach an academic writing class on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays, in which I show films from around the world to expose students to unfamiliar cultures, worldviews, and ideas about faith and culture, and to show them how religious ideals influence films as wildly different as Raising Arizona, Tokyo Story, The Fits, and The Son. Yesterday, I showed The Breadwinner.

The students were enthralled. And, as with the other two features from Cartoon Saloon, a second viewing impressed me even further. I am convinced that this is the most imaginative and important animation team in the world right now. (Here's a thoughtful review by Scott Douglas of Mountain Express. And you can read my own review of the film here.)

As my students quietly departed the classroom, I asked them to come back on Monday with questions inspired by the movie, questions that could become the focus of research papers about the movie's subjects, themes, and artistry.

Me, I had a very specific response this time, and questions I couldn't stop thinking about for the rest of the day. I think I find the movie's most frightening character — that young, gun-wielding Taliban trainee, as simple and undeveloped as his character seems to be — to be more disturbing than any villain I've seen in a movie for a while.

Perhaps it's because he seems driven by an irrational power beyond himself. His sense of insecurity is obvious, and thus, provided with a gun, he wages an endless war against anything he doesn't understand. He rejects his own education as "useless," and punishes his former teacher, showing nothing but contempt for a soft-spoken old man who lost his leg defending the very community in which this young blowtorch grew up. He abandons any notion of love, and treats women as something to seize and use or to terrorize and destroy. He reaches for any stupid reason he can think up to punish those who have the dignity and integrity and understanding that he lacks.

The gun doesn't kill people, no — but it enables the one who carries it to unleash a reign of terror on his neighborhood, fueled by his insatiable desire for control and superiority.

Meanwhile, Nurullah's quiet family gleams as a fragile wonder, a candle's flame doomed by a rising storm, in which the much larger guns of the "enlightened" West will unleash terror on this entire society, as we seek to punish and seize and use and control what we do not understand.

And here at home, I check the news and find out that our President wants to address problems of increasing violence by distributing even more guns into our communities and schools — which will, of course, only further empower the reckless, the angry, and the insecure. (For a better understanding of what might actually help our nation recover from its disease of gun-empowered hatred, read Nicholas Kristoff's New York Times analysis.)

Once upon a time I would have looked at The Breadwinner as a movie about a foreign culture toxic with hatred, prejudice, greed, and a demonic sort of hyper-masculinity. Now I look at it and see a reflection of my own society, in which men who worship the power of guns are clinging to them in desperation, hiding behind them, terrified that their illusion of superiority will be spoiled and the truth of their weakness and insecurity will be exposed.

Black Panther (2017): Post-Panther Questions

A Letter to the Wakandan High Council

(or Wakandan Royal Court, or whatever you wise and troubled royalty

— who sit around Black Panther's throne like you're inspired by

Jedi Council meetings in the Star Wars prequels — call yourselves)

Dear Wakandan Royals,

If you are willing to accept mail from those of us moviegoers who have no access to your kingdom — those of us who (as the movie reveals) have been kept from discovering this high-tech African paradise, those of us who are apparently looking at an illusion of dense forests when we zoom in toward Wakanda on Google Earth — I would like to be among the first to congratulate you.

You've won me over in ways that no Marvel movie has. This isn't fanboy enthusiasm. I've seen all of the Marvel films out of a sense of responsibility, entertained by great actors in flamboyant performances, amused but often bored by the comic-book narrative formulas, and weary of simplistic good-guy/bad-buy showdowns. The Avengers and Doctor Strange are the only two I've had a desire to see more than once... until now.

Black Panther — your story about the death of King T'Chaka, the rise of King T'Challa, his quest to recover some of your magical precious metal called Vibranium from murderous villains, and his subsequent struggle with a righteously angry challenger for the Wakandan throne — is a dazzling big-screen moviegoing experience.

While I'm still uncertain how your kingdom's massive Invisibility Cloak prevents planes from straying into your airspace, and I probably don't want to know what happens to birds who strike your concealment shield, I cannot wait to see the wonders of your world a second time.

I write to you with more than praise, though. Your movie movie made me think, which Marvel movies rarely do. And, as a result, this one has left me troubled by questions.

I wish I could say that Black Panther stands out as an exceptional Marvel movie narrative. Alas, I cannot.

Exceptional context? Yes. Your film's imaginary world is really not so imaginary: It represents a vision that represents histories of racial and cultural memory that have been all but beaten out of recent generations by centuries of cruelty and exploitation at the bloody hands of European colonization and slave traders. It represents a big-screen flag raising: a celebration of dignity and cultural riches that the rest of the world doesn't know about and, often, doesn't want to know about. It's a triumph, and a humbling thing for someone like me, embarrassed and ashamed of the privilege I've inherited through my own ancestors' disgraceful history.

Exceptional conscience? Indeed! Black Panther complicates the usual good-guy/bad-guy routine by giving our hero — King T'Challa (played with quiet nobility by Chadwick Boseman) — an attachment to a wrongful and fearful isolationism, wanting to keep his kingdom of Wakanda separate from a world that would seek to corrupt it. Who can blame him? And yet, this prioritization of self-preservation leads to withholding help when help is needed, and from refusing relationships when they are essential to the future of a healthy world. The stage is set for a hero's moral awakening.

And it helps that he's surrounded by wise, powerful, and assertive women as well as men. In Wakanda, we don't need to see a righting of wrongful gender inequality. All we need to do is see the dignity, strength, and intelligence of T'Challa's mother Ramonda (Angela Bassett), his genius sister Shuri (Letitia Wright), his justice-seeking sweetheart Nakia (Lupita Nyong'o), and the army led by Okoye (Danai Gurira), and we can all see in Wakanda what we need to see realized around the world.

The hero/villain dynamic is also complicated by the motivations of T'Challa's most dangerous enemy — Eric Killmonger (played by Michael B. Jordan, who revels and struts in this moment with the cocky fury of a real-world Panther: Cam Newton).

Killmonger isn't easy to write off. His reasons are righteous, though his tactics are not. He wants to seize the throne in the name of generations of Africans who, cut off by Wakanda's extraordinary resources and powers, have suffered unspeakably and (worse) unnecessarily.

So, yes: On matters of context and conscience, this is an ambitious epic.

Black Panther is a lot of wonderful and inspiring things, and many of those things are technical achievements. Far more engaging than the familiar, formulaic beats of its heroic symphony are the unconventional instruments that make it rock. T'Challa's story isn't particularly engaging, but it serves as a sturdy scaffold for all kinds of colorful pageantry, winning performances, and meaningful advances in cultural and racial representation.

It's a relief to know that Marvel stories can be based in parts of the world beyond big-city USA, rather than taking that tourist-y approach that seems so annoyingly American — merely dropping in to other countries to use natural wonders as dramatic backdrops, or to visit gurus who hide in remote places. As Coco is for Pixar, Black Panther is rightfully celebrated as a Marvel groundbreaker, opening this mega-franchise fantasyland for stories that honor other histories and experiences. How much better that even the director is African American. (Let's face it: Coco, for all of its cultural authenticity, still had a white guy in the big chair.)

All manner of praises for Black Panther's sights and sounds have already been sung: Not since Doctor Strange has the Marvel template come alive with such kaleidoscopic spectacle. I would watch this movie just to bask in the glory of the costume designs — from the bold green lip plate sported by Isaach De Bankolé (who, for obvious reasons, has no dialogue) to the exquisitely filigreed crown worn by Angela Bassett to that spectacular makeup Forest Whitaker wears.

I love how you've made such ancient and traditional designs so convincing in part of a futuristic society. Even their highest-tech Wakandan fighter jets impress, looking from above and below like tribal masks.

The action scenes are an aesthetic pleasure, even outside of that folk-art context.

The car chase hyped in the trailer turns out to be a rollercoaster ride of sleek, streaming neon, and the big James-Bondy battle in a dark casino outdoes Skyfall with some thrillingly gratuitous choreography and color that made me gasp; one flourish of Danai Gurira's red dress made me applaud.

And I think this may be the first Marvel score that I've been eager to hear out of the context of a screening: the music that Ludwig Göransson brought back from Senegal and South Africa gives this adventure a personality all its own.

Black Panther is also inspiring — albeit heavy-handed and on-the-nose — in its Timely And Relevant political commentary. Normally I would have little patience for pulpit-pounding, but the world's gone so stupid lately that I'm happy to hear such obvious sense about the essentiality of global community being shouted at audiences. (Good grief: The end credits speech is so February 2018, I half-expected the speechmaker to break the fourth wall and say "Am I right, America?")

So, this brings me to the questions that rose to the surface after I emerged from the happy delirium of the crowd, questions that bug me like itches I can't scratch. Because for all of the things that Black Panther achieves, a work of efficient, surprising, and inspiring storytelling, it is not.

QUESTION ONE:

If Wakanda is such an advanced and enlightened society, and if its leaders rule in wisdom, why permit such a ridiculous ritual as a hand-to-hand combat challenge for the throne to continue?

Is physical supremacy really so important in a king?

There might be someone with a legitimate complaint against T'Challa, but what if that challenger stands no chance against him in the ring?

The fact that such an important matter is decided by a fight that could potentially end with a fatality suggests that there are problems even more fundamental than isolationism at work in Wakandan society. And it's a problem that has infected the Marvel franchise from the beginning.

There's a second part to this question:

If you really must focus on introducing challengers as if the throne is a World Wrestling Federation trophy, why can't you make your hero more interesting than his challengers?

I admire T'Challa's softspoken style and even-temperedness: those are good leadership qualities. But he doesn't command the screen the way any of his opponents do.

QUESTION TWO:

You want us to believe that the Wakandan world has chosen to hide from the rest of our world for centuries, rather than offer their technological advantages, their miracles of healing, and their wisdom to help suffering peoples around the world. And you acknowledge, in this movie, that this history is a shame, a wrong that needs correcting.

But I have a difficult time believing that the Wakandans were willing to keep their cover during the extraterrestrial invasions that threatened the entire earth like those we've seen in The Avengers, especially if they had the technology to stop it. This movie seems awfully willing to forgive Wakanda's history of isolationism without taking into account how many times they've put the whole planet at risk, how many genocides they've ignored, how many environmental crises they've allowed to fester.

Are they enlightened, or aren't they?

QUESTION THREE:

Is it because you know that Marvel movies have a global audience that you speak in such simplistic dialogue?

Marvel movies are often praised for their snappy writing. Most of these characters stay within their action-figure molds, delivering lines that sound like they were written with a Marvel-branded "magnetic poetry" kit.

Only a few scenes here achieve anything close to nuance. I'm rather fond of the good-humored exchanges between T'Challa and his feisty sister Shuri, who seems to idolize James Bond's Q.

QUESTION FOUR:

Did you pay any attention to the reviews for the DC franchise's first decent movie — Wonder Woman — which consistently lament how so much fun and imagination could conclude with such a mundane showdown between a hero and a villain?

Don't get me wrong: Michael B. Jordan is one of the most distinctive and interesting villains to come along in a Marvel movie, and he becomes more interesting as the movie goes on. Unfortunately, he's most interesting at the end, just when we're really getting to the root of his complaints, the heavy heart of the matter.

With so much potential to explore larger themes, it's a shame that Black Panther's battle scenes become increasingly derivative — those between tribal factions, those involving fighter jets rocketing out of Wakanda, and those that involve T'Challa's fights with Killmonger — dragging this movie back down into the familiar muck, where moral quandaries are resolved with physical blows rather than triumphs of humility, generosity, or grace.

This problem hangs like a curse over Marveldom. Only Doctor Strange has found a way to momentarily break its tedious grip.

QUESTION FIVE:

What is it with this movie's Return of the King obsession?

I'm not just talking about the distracting confrontations between Andy Serkis (who seems giddy here, unleashed to be a monstrous human being instead of a Gollum or an ape) and Martin Freeman (who seems to combine his two most famous performances — Bilbo and Watson — without finding anything new, unless you count a distracting American accent that often sounds overdubbed).

Mostly, I'm distracted by the climactic battle scenes, the twists that turn them, the appearance of armored pachyderms, and some of Black Panther's far-too-Legolas-like maneuvers. I'll stay off the spoilers, but it's a shame that Wakanda, with its concerns about renewable energy sources, can't stop recycling on the battlefield.

Why not invite some more imaginative and artful screenwriters to put more "Brainy" in the Vibranium?

What's more — Black Panther's finale has so many frantic storylines going on at once that none of them have a chance to become absorbing the way that earlier action scenes were. (Poor Martin Freeman, playing such an extraneous character throughout, ends up on an aerial mission that feels included for the sole purpose of providing some video-game material. Watching Sherlock, I feel sorry for Watson; here, I feel sorry for the actor.)

That's Enough...

I could go on with the questions, oh Great and Mighty Wakandan Council, but I'd rather return to expressing my gratitude for the highlights, which I will not soon forget...

... especially, the sight of that all-female army led by Danai Gurira's Okoye. Okoye's brilliantly acrobatic performance with her vibranium spear, will stick with me as one of the most kinetic, balletic wonders I've seen at the movies since Zhang Yimou's Hero.

Frankly, if the Wakandan Royal Family has any sway with the High Council of the Kingdom of Marvel, I'd like them to put in a request for a spinoff movie focusing on Okoye herself. She steals this show whenever she's in it. And now that Wakandans are finding a new spirit of engagement with the world beyond, I'd love to see where her combination of conscience and kick-assery take her.

Similarly, I find myself hoping that Marvel is bound for a braver, more creative future. So long as it brings on visionary artists — like your movie's writer-director Ryan Coogler, his co-writer Joe Robert Cole, and Doctor Strange's Scott Derrickson, who have all refused to settle for the standard parameters of Marvel storytelling — they just might turn me around and make me a Marvel fanboy yet.

Sincerely,

Jeffrey Overstreet

P.S.

Ant-Man and the Wasp looks like fun.

Wingfeather climbs from bookshelves to screens

When my novel Auralia's Colors was first published, it was promoted by the publisher, WaterBook Press, alongside the first novel of another fantasy author like myself: Andrew Peterson.

That book was titled On the Edge of the Dark Sea of Darkness. And so began The Wingfeather Saga: a series of Peterson's fantastical novels that weave a tapestry made of threads of inspiration drawn from sources as wildly different at The Chronicles of Narnia and Monty Python's Flying Circus. They've enchanted countless readers with their humor and their heart. If you haven't discovered them yet, you have many hours of fun ahead of you.

The parallel publications of the books in Peterson's saga and the books in my own series (The Auralia Thread) occasioned the development of a meaningful friendship, one that has blessed me with not one but two brothers in fantasy writing: Andrew and his brother, A. S. Peterson (author of The Fiddler's Gun).

It also introduced me to a community of artists, writers, and readers that has rallied around the Petersons for years: The Rabbit Room. Their annual Nashville gathering, called Hutchmoot, has given me some of the most meaningful experiences in imaginative community, and introduced me to life-changing friendships.

And now, Peterson has teamed up with animator Chris Wall and a "fellowship" of filmmaking talents to bring their vision to the screen.

You can watch a new 15-minute short film on YouTube, Facebook, Vimeo, and Amazon Prime for free. That should give you an itch to see more... on the page and on the screen.

https://vimeo.com/248762872

You can find out much more on Peterson's website, which recently posted this:

We’re excited to plunge headlong into the odd and dangerous world of The Wingfeather Saga and to share these stories with a broader audience as we bring the books to new life through a fully CG animated short film.

Tom Owens (head of story How to Train Your Dragon 2), Keith Lango (Valve Corp), Nicholas Kole (Disney, Hasbro) and J. Chris Wall (VeggieTales) have joined forces with Andrew Peterson to create Shining Isle Productions and bring the best-selling novels The Wingfeather Saga to life on screen. After a wildly successful Kickstarter campaign (top 15 animated projects of all time), they created a 15-minute short film that debuted December 26, 2017. With an innovative painted style CGI with 2D environments, they’ve created a distinctive visual look and extended that to their motion style which emulates stop-motion using limited breakdowns. They are developing the story for distribution as a multi-season series which will explore the entire four-book [series].

I wish Peterson, Wall, and their partners in imagination the very best as they take this to the next level.

Jóhann Jóhannsson: Arrival and Departure

This is unreal.

This morning, I sat down to write in a quiet corner at the back of the Roy Street Coffee shop, opened my laptop, put on my headphones, and pressed "Play" on Jóhann Jóhannsson's strange and mysterious score for the Denis Villeneuve film Arrival.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qsaRJ4j4xIo

Arrival has become a reliable soundtrack for imaginative writing: It takes me into liminal spaces where mysterious ideas emerge.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=F0ahB25FJ6o

And as those deep, dark tones unsettled me in ways that make me want to write, I sipped my coffee and started closing social-media apps so that I would have the freedom to think for myself.

I didn't close them fast enough. A headline caught my eye:

Jóhann Jóhannsson, ‘Theory of Everything’ Composer, Dies at 48

I'm stunned. Kicked in the gut.

He's just getting started as one of cinema's most exciting composers. He can't have left us already.

He's only a few months older than me, for mercy's sake.

Today, this music is not about "arrival" — but "departure."

https://vimeo.com/145497571

Jóhannsson's imagination unleashed some of the most distinct and evocative sounds I've heard in recent years of cinema.

He did not follow a template, imitate other film composers, or tell us how to feel. Instead, drawing from the rich reservoirs of musical imagination that flourish in his Reykjavík home, he had a knack for conjuring sonic equivalents for our own unvoiced questions, our unease in the presence of mystery, and our deep connections to the worlds beyond the reach of our senses.

https://vimeo.com/47395755

When I watched Arrival, I saw some unusual and startling imagery of aliens, but I felt those encounters more powerfully in what I heard than what I saw. And I remember noticing the unexpected influence of the music in Sicario and Prisoners as well. I fully anticipate that he will play a central role in Garth Davis's upcoming film Mary Magdelene, starring Joaquin Phoenix and Rooney Mara.

And I'll welcome his haunting of my headphones, my moviegoing, and my imagination for many years to come.

Rest in peace, Jóhann Jóhannsson. May you find mercy and grace in embrace of the Mystery from which your music came. And thank you for bringing such sounds into the world.

https://vimeo.com/johannjohannsson

Paddington 2 (2018)

[This review was originally published at Good Letters, the official blog of Image.]

As immigrants fall to the fury of fearmongers, could it be Paddington the bear (a household name for families who cherish children’s books) who reawakens the heart of England to compassion, cooperation, and community?

As if designed to shame isolationists, Paddington 2 sends its hero (a soft-spoken immigrant himself) stumbling into a case of mistaken identity, where he’s blamed for a crime he didn’t commit. The story sparks when Paddington, saving money to buy a beautiful popup book of London for his beloved Aunt Lucy, reveals the existence of this hardbound treasure to a fortune hunter who believes that the book contains a treasure map.

And so begins a tug of war over a vision of London—one that leads to a robbery, a wild nighttime pursuit through London streets, and the incarceration of the city’s finest CGI citizen.

Do you remember the Brown family—Mr. Henry (Hugh Bonneville), Mrs. Mary (Sally Hawkins), Young Jonathan, and Young Madeleine—who adopted Paddington in the first film? You can imagine how distraught they are, with Paddington thrown in the paddy wagon.

It doesn’t help that the judge ruling on Paddington’s case happens to have a terrible haircut: the fault of Paddington himself, who, it turns out, isn’t cut out to be a barber. Making matters even worse, Paddington’s conviction throws fuel on the fire of the Browns’ racist neighborhood watchman (wild-eyed Peter Capaldi), who capitalizes on the moment to preach paranoia and prejudice.

Sound serious? Don’t worry. Paddington 2 recaptures the subtle charms of director Paul King’s original, and succeeds brilliantly as a film that’s as richly rewarding for adults as it is for kids.

While bombing at the U.S. box office, it currently stands as the best-reviewed film in the history of Rotten Tomatoes. What gives? Scott Renshaw of the City Weeklyhas it just right: This is “exactly the kind of movie parents always claim they want for their children, but too rarely support with their dollars.” Support this film!

Appointing themselves as investigators, the Browns hunt the real criminal, a disguise-happy crook, with the clever use of every detective’s most essential tools: a bulletin board, push pins, and lots of yarn to connect the clues.

Meanwhile, Paddington—locked up with lawbreakers on charges of “grand theft and grievous barberly harm”—stumbles through big-house dangers with only his gentle naiveté and Aunt Lucy’s marmalade recipe to save him.

His prison bears a suspiciously symmetrical resemblance to the one in Wes Anderson’s The Grand Budapest Hotel, and is packed with a similar number of celebrities. Most dangerous of all is the prisoners’ chef: a gruff giant called “Nuckles” (Brendan Gleeson at his best). This bearded brute strikes fear into the hearts (and rolling pins into the heads) of his fellow prisoners.

Nevertheless, Paddington is a peacemaker. Spreading his sweet and sticky influence, he can soften the hearts of the most hardened criminals.

But wait, there’s more-malade.

I haven’t talked about Phoenix Buchanan yet—the thieving thespian who should have gone to prison in Paddington’s place, but instead seems to be slipping into a sort of schizophrenia. Scheming in the company of costumes from his past as a star in the West End, he’ll do anything to escape his late-career humiliation as a dog food spokesperson and buy his way back into the spotlight.

And look who’s back in the spotlight! Hugh Grant seems absolutely giddy about scoring the juiciest role he’s had in, well, his career. As Phoenix, he carries on whole conversations with himself in past roles: Scrooge, Poirot, and various Shakespearean heroes. (And don’t count him out at the end: He might live up to his name and rise from the ashes of the credits.)

Grant and Gleeson are the highlights in a film full of famous faces giving their all to celebrate a picture of a multicultural London. It’s an award-worthy ensemble, right down to the diminutive bear, gently voiced by Ben Whishaw. Stumbling through references to Charlie Chaplain and Buster Keaton, the bear’s soft answers turn away wrath, his soft fur proves an advantage for a window washer, and his soft heart is big enough to persuade all of England that immigrants bring them more hope than hardship. Few CGI characters have interacted with humans so seamlessly.

If it sounds a bit busy, it is. Paddington 2 has so much story going on that it overlooks one of the narrative’s most important results. Note that Paddington’s chief desire is to bring his Aunt Lucy to London so that she can see the place for herself, and the movie’s most enchanting sequence occurs when Paddington opens his big London popup book and then walks right in. And what makes the dream possible? An art that Aunt Lucy passed on to him—a creative craft he can offer almost anywhere to bless anyone he encounters.

And if I might make one more slight gripe about this critical favorite: When the film, which has been beautifully engaging in unexpected ways throughout its first ninety minutes, suddenly plunges into a prolonged action sequence involving passengers on parallel trains, I can feel the Pixar template intruding. Audiences expect a frenzied finale. Here, that feels a Brit out of character. But don’t let that stop you from chasing down this most magnificent marmalade sandwich before it’s deported from theaters: It’s soft, its sweet, and it’ll stick with you. Take your BBC-loving friends, because few movies have featured more celebrity cameos since 1979’s The Muppet Movie.

Paddington 2 is a Who’s Who of British talent, featuring Joanna Lumley, Noah Taylor, Eileen Atkins, Jessica “Spaced” Hynes, Claire “The Trip to Spain” Keelan, Richard “The IT Crowd” Ayoade, and Simon Farnaby (Garfunkel on The Detectorists).

It’s unlikely that a bear can beat Brexit. But it is likely that this film will become, like The Muppet Movie, an enduring favorite for the lovers, the dreamers… and me.

This review is brought to you by the Looking Closer Specialists,

whose donations keep this website alive against all odds.

Thanks in particular to Claire Tanner for making this review

possible. Did you enjoy this review? Donate the price of a movie

ticket, or as much as you wish.

-

-

Overstreet's Favorite Films of 2017: The Top Ten

It's that time at last: Time to offer reflections on the ten films released in 2017 that mean the most to me.

(I posted a countdown of #30–#11 earlier this month.)

It was a great year for women in film — both behind and in front of the camera. The DC Universe got its best film since The Dark Knight from director Patty Jenkins, with Gal Gadot superhumanly powering Wonder Woman to blockbuster success. Mudbound, directed by Dee Rees, earned an Oscar nomination for Mary J. Blige (Best Supporting Actress) and the first-ever nomination of a woman for Best Cinematographer (Rachel Morrison). We enjoyed empathetic portraits of woman seeking to defy the pressures of the patriarchy and live authentic lives in A Quiet Passion and Phantom Thread (although the latter could have shown more curiosity about its 'heroine'). And even some of the films directed by men were powerful in exposing and grieving the sins of our power-mad, abusive, patriarchal society: Look no further than the film in second place on my list of favorites.

It was also a great year for endeavors in empathy for people of other cultures and religions, and for the poor: My favorite romantic comedy of the year asked us to consider the experiences of a modern family of American Muslims and the struggle of one young man to live in the tug-of-war between America's cultural ideals and the standards of his family's religion. My favorite horror film was about the racism of those who would congratulate themselves as being "progressive." Another of my favorite films asked us to live with the poor and troubled families suffering at the edges of America's toxic fantasyland in Florida, and portrayed that community with such compassion that they seemed more compelling, courageous, and beautiful than any glamorous archetypes, and their struggle was shown to be so much more visceral than any superhero's. Any my favorite animated film was about a young woman trying to help her family survive under the cruel hand of the Taliban.

What a year!

And as I have seen so many of these films only once, I can only offer a "first draft" of this list. As time passes, my appreciation and understanding of these films will grow and change, and as I revisit them, I will see more strengths and, perhaps, some weaknesses. So this list is likely to change. Keep in mind that there are still several critically acclaimed films I have yet to see — case in point: Frederick Wiseman's celebrated documentary Ex Libris: The New York Public Library. Also: The Work, Call Me By Your Name, Princess Cyd, and, most importantly, the final film by Abbas Kiarostami: 24 Frames.

And if you're asking where popular favorites like Three Billboards and The Shape of Water are, well... suffice it to say that those movies didn't work for me. At all. Sorry.

#10 and #9

Get Out — dir. Jordan Peele

https://youtu.be/sRfnevzM9kQ

mother! — dir. Darren Aronofsky

https://youtu.be/XpICoc65uh0

Both Get Out and mother! are powerfully directed.

Both films create suffocatingly grim environments for their lead characters, trapping them in nightmares where they slowly awaken to the fact that they are being exploited. Their humanity goes unrecognized by their community. Their endeavors for respect and love go unsatisfied. Their attempts to play meaningful roles in someone else's world are taken for granted. Ultimately, these characters will realize that nothing they can do will save them from the manipulative, egomaniacal Supremacy that controls the game.

And in both cases, all of the elements of the ensemble and the environment work together beautifully, like pieces of some fiendishly designed clock, to increase our anxiety and to give us empathy for the sufferers. Considering just how outlandish both fantasies are, it's unsettling just how true-to-life they feel, and how truthfully they reflect the state of democracy and false religion in America today. I shared these characters' sense of anguish, in that I have felt much the same sense of despair looking around at the cruelty and greed dismantling democracy in America.

We need art like this: to confirm cries of conscience, to help strengthen the things that remain, and to help us grieve the destruction of good things that so many people spent so many decades — even centuries — trying to build for the good of the world.

Both of these films were ambitious, audacious, and could easily have fallen apart by losing their delicate tonal balance. Both manage to be terrifying and hilarious. Both succeed by just going for it and letting bombast and explosive panic serve as a good thing, without collapsing into recklessness or self-indulgence.

And both end up offering meaningful readings. In the case of mother!, we can find multiple meaningful interpretations. This was the year of #MeToo and the "Silence Breakers," and mother! gave us a mythic story about the progress of this struggle since time immemorial in marriage, in art, and in religion. This was the year that #BlackLivesMatter took things to the next level, protesting Amerikkka's rule by white supremacists, and Get Out refused to let anybody off the hook.

Both movies were meaningfully and masterfully directed. They may have been extremely unpleasant for many audiences, but I admired the risks taken, the wild visions pursued and achieved, and the conviction of the actors' performances.

In Get Out, Daniel Kaluuya plays all the right notes to guide us steadily through the dissonant chord changes of the movie's horror and comedy. I'm delighted that the Academy chose to honor him. For her work in mother!, Jennifer Lawrence deserved just as much recognition; she gives an extremely complicated performance, and her supporting cast (featuring Javier Bardem, Ed Harris, and especially Michelle Pfeiffer) is extraordinary.

#8 and #7

The Lost City of Z - dir. James Gray

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hjqtP459uo8

A Quiet Passion - dir. Terence Davies

https://youtu.be/Ffc8tLkviOo

Both The Lost City of Z and A Quiet Passion are about brave explorers — one in realms of the imagination and spirit, the other in jungles of Bolivia.

Both of their lead characters are famous historical figures who were seen as eccentric and countercultural.

Both individuals were driven by something more than ego. Emily Dickinson wanted a life of authenticity, living without compromising or conforming to the expectations of her culture or religious tradition. Percy Fawcett wanted to prove himself a man of integrity, but that ambition was eventually overwritten by a stronger drive to find the truth about the origins of civilization — and that was influenced by a sort of spiritual awakening, a longing to rediscover a sort of Eden.

Both pioneers sacrificed a great deal to pursue their visions. Both tested the patience of their loved ones to a breaking point. Both were lost in suffering and troubling mysteries.

Both films give their lead actors their most complex and demanding roles yet: Cynthia Nixon as Emily Dickinson gives the best performance by an actress I saw all year. Charlie Hunnam's work as Percy Fawcett paints a portrait of a man losing himself in the momentum of his vision.

And both of these films are magnificent, mysterious, and sumptuously filmed. Davies' film is more intimate and painterly; Gray's film is an epic the scale of which we rarely see attempted, a film full of echoes of Apocalypse Now.

#6

Columbus - dir. Koganada

https://youtu.be/zRT2yKhRlTE

When a touring architecture scholar collapses before a lecture in Columbus, Indiana, his fall brings together two unlikely seekers: the young and directionless Casey (a radiant Hayley Lu-Richardson), his admiring fan, and his resentful son Jin (John Cho), a Korean-American translator.

Casey’s days, darkened by vocational uncertainty and the cloud of her mother’s depression, are brightened by this chance to show a skeptical visitor around her neighborhood and share the beacons of architectural beauty that have kept her from drifting into despair. As they wander around the city and ponder the meaningful mysteries of asymmetry in Columbus’s public spaces and churches, their tenuous friendship transcends “Will they or won’t they?” routines.

Meanwhile, the scholar's vigilant, harried assistant (Parker Posey) works to heal the prodigal's family rift.

If you know me, you know that there is no idea closer to my heart than "Beauty will save the world." Here's a movie for a film festival on that subject. Beauty becomes the magnetic influence that draws broken people toward fulness — and toward one another (through which a greater fulness can be found).

First-time director Kogonada is an artist of admirable patience, vision, and subtlety. Recalling Linklater’s Before Sunrise, Coppola’s Lost in Translation, and (above all) Jem Cohen’s Museum Hours — which it resembles almost too much — Columbus is an exquisite, soft-spoken surprise about the reconciling and rejuvenating effect of (for lack of a better term) intelligent design. I can't wait to see what he does next.

#5

The Big Sick — dir. Michael Showalter

https://youtu.be/PJmpSMRQhhs

I won't apologize for this pick. Yes, it's a romcom formula right down to the Lines You Knew They Would Repeat at the End. Yes, it goes for big obvious laughs at times. No, there's not a single image demonstrating anything like poetic composition.

This may drive some cinephiles nuts, but the fact is that a movie made with the production value of a typical TV sitcom might still be capable of inspiring, moving, and winning the heart of somebody like me — and that does not represent a failure of judgment.

I love this movie for qualities that are impossible to fake, and for very personal reasons.

I believe in these characters. I believe in the complexity of their relationships. I believe that formulas are formulas because they reflect something common and true, and that when you invest them with honesty and lived experience and imagination then the recipe serves the result rather than the result just filling in the blanks of the recipe.

I also saw this soon after spending the better part of a week in the hospital with the love of my life, who underwent emergency brain surgery and was on such heavy drugs for a week that she lost many days of her memory. During that time, I experienced some of the same anxieties experienced by Kumail here. I also experienced, with Anne, one of the key conversations that Kumail and Emily have here — the one about how my version of the story about her is not really her story because she was not exactly present to experience it — which leads to a profound disconnect in our emotions related to the crisis. This movie gets that strange and difficult conundrum.

But above all, I love how this becomes a love story between a young man and his girlfriend's parents, who are themselves demonstrating, in their disputes and betrayals and failures, that love is a verb, and one that rewards long-suffering and resilience and forgiveness. The whole cast is extraordinary — Kumail Nanjiani and Zoe Kazan convince us that this is based on Nanjiani's own true story — but Ray Romano and Holly Hunter are miraculous here. I would watch a spinoff TV series if it was about their characters' marriage.

And yes, this movie is very, very funny.

And let's not overlook that this movie celebrates the reality of peace-loving American Muslims. In 2017, it feels like a glorious blast of truth and love in an environment stormy with lies and hatred.

I can tell you a hundred things that I love about cinema that this movie doesn't seem to know exist. But I love this movie anyway, and expect I will love it just as much the fourth time I see it.

Thanks to my friend Josh Hornbeck for taking me to see this on opening night at the Seattle International Film Festival, where we also got to enjoy a post-screening interview with Kumail Nanjiani and Emily Gordon, who deserve their Oscar screenwriting nomination.

#4

The Breadwinner - dir. Nora Twomey

https://youtu.be/9G6yZZguI04

This marvel of animation and empathy is magnificent, timely, and true. I stand in awe that a studio invested so many resources, so much work, and so much love in a film so contrary to what our Disney-drunk audiences have come to expect from animation.

Caution: You will be moved. Gut-punched, possibly. I was. Nevertheless, I would recommend it for children — not small children, but ages seven and up perhaps — especially if parents and teachers talk with them about it. Cartoon Saloon is doing work as essential as any film studio I know.

You can read my full review here.

And now I will hand the mic to the great Presbyterian minister Frederick Buechner:

Literature, painting, music — the most basic lesson that all art teaches us is to stop, look, and listen to life on this planet, including our own lives, as a vastly richer, deeper, more mysterious business than most of the time it ever occurs to us to suspect as we bumble along from day to day on automatic pilot. In a world that for the most part steers clear of the whole idea of holiness, art is one of the few places left where we can speak to each other of holy things.

Is it too much to say that Stop, Look, and Listen is also the most basic lesson that the Judeo-Christian tradition teaches us? Listen to history is the cry of the ancient prophets of Israel. Listen to social injustice, says Amos; to head-in-the-sand religiosity, says Jeremiah; to international treacheries and power-plays, says Isaiah; because it is precisely through them that God speaks his word of judgment and command.

And when Jesus comes along saying that the greatest command of all is to love God and to love our neighbor, he too is asking us to pay attention. If we are to love God, we must first stop, look, and listen for him in what is happening around us and inside us. If we are to love our neighbors, before doing anything else we must see our neighbors. With our imagination as well as our eyes, that is to say like artists, we must see not just their faces but the life behind and within their faces. Here it is love that is the frame we see them in."

(from Wishful Thinking, later republished as Beyond Words)

#3

Mudbound - dir. Dee Rees

https://youtu.be/xucHiOAa8Rs

Thirty minutes in, I pretty much gave up, thinking that Netflix's original film Mudbound was taking on far too much: too many narrators, too many storylines, too many Big Issues, too much Condensed History. Plus, it was working like a full-cast audiobook with illustrations provided by the School of Malick Apprentices — and I like my movies when the images speak as much or more so than the script.

But illustrated narratives are a powerful medium, nevertheless.

And thank God I didn't turn it off. 45 minutes in I was hooked. An hour in, my heart was breaking. And it would wring me out with its whole-hearted, whole-bodied performances, its vision (expansive enough to include the essential role of Gospel in its world), its unflinching acknowledgement of Amerikkka's past and the implications of Amerikkka's present, and its refusal to oversimplify any character into an uncomplicated hero. I don't remember the last time I sat through end credits with tears streaming down my face.

This was America then. This is America now. Anything I might mention that feels slightly contrived in this film's craftsmanship just isn't worth getting worked up about when held up to the magnitude of this film's Truth-telling, its astonishing cumulative power, and the importance of sharing it far and wide with our families and friends.

I admit, I thought it looked like too obvious a reach for prestige and awards and political point-scoring and Netflix Original territory marking. And I admit I also doubted due to the prominence of Hedlund, whose many high-profile roles so far haven't done much for me. (Perhaps that had more to do with how they were written, I don't know.)

But everything works here, including the cinematography and score. Carey Mulligan is in top form, Jonathan Banks is downright terrifying, Jason Clarke is perfectly complicated, Jason Mitchell is outstanding, and Rob Morgan and Mary J. Blige are the film's broken hearts that beat as one. And Garrett Hedlund, whose past performances have never quite worked for me — God bless him, this is a career high, a performance that leaves me grateful.

Dear director Dee Rees,

Your movie is a gale-force lament that I needed. I hope my country — and our leaders — will watch and take it to heart. I don't expect that. But I don't underestimate the power of art — even good old-fashioned multi-narrator storytelling like this. It shouldn't have worked in such an efficiently directed feature film, but you made every one of these 134 minutes count. I am humbled and grateful.

Thanks also to Steven Greydanus for nudging me to see this before publishing my year-end list.

Lord, have mercy on this nation. Forgive us our trespasses. Forgive us our convenient silences and inaction. Forgive us our ongoing failures to repent and to make amends and reparations. And deliver us — and all who suffer our injustices — from evil.

#2

Phantom Thread — dir. Paul Thomas Anderson

https://youtu.be/xNsiQMeSvMk

In Phantom Thread, the extraordinarily talented but insufferably self-absorbed Reynolds Woodcock (Daniel Day-Lewis), a renowned dress designer, goes to a bistro, falls under the spell of a beautiful waitress, and proceeds to order almost everything on the menu. He's hungry. And when he's hungry, that means he's inspired. He's an artist, and he's ready to work.

His waitress is named Alma (Vicky Krieps) — which, and I cannot emphasize this enough, is also the name of the woman who married Alfred Hitchcock, and who suffered faithfully alongside him as he made masterpiece after masterpiece, his attention so caught up in his vision that he made a public embarrassment of himself by obsessing over the leading ladies of his films. Woodcock is the same way: He's obsessed with what he decides is a sort of Platonic ideal of a woman, and keeps casting women who look like her, trying to capture a kind of magic so that he finds inspiration enough to continue his run of breathtakingly beautiful dress design.

Phantom Thread is the story of what happens when one woman refuses to accept Woodcock's ideal of a one-sided relationship, which is a model of exploitation. She wants intimacy. And she is willing to go to extremes to get it. The movie's disturbing and yet absorbing tension comes from the possibility that the artist might, eventually, come to realize that he does need love, that he is deeply flawed and needy, that he — with his extreme opinions and fragile (read 'easily aggravated') sensibilities — is a terror to live with, and that he needs to surrender control on occasion in order to enjoy a real partnership.

It's also the story of how a woman determines to teach her man that his idea of love is self-serving, and that something greater is possible.

This becomes a clash of titans — Vicky Krieps is, remarkably, a match for Daniel Day-Lewis in bringing these characters to life. And it also fails to escape a rather troubling and perverse picture of a marriage, in which intimacy only becomes possible by the establishment of some rather unhealthy routines. But altogether, it works on several levels: as a darkly comic caricature of the uneasy compromises and contracts that partners must strike in a marriage; as a portrait of the demanding and difficult relationship between an artist and his muse; as an analysis of the contradictions and sicknesses that characterize the careers of so many artistic geniuses (especially Hitchcock, whose style this movie celebrates); and of Paul Thomas Anderson's own creative obsessions (this film plays with many of the same subjects and themes we saw in Punch-Drunk Love).

I don't like throwing this word around prematurely, but I'm confident in saying that this movie is a masterpiece — and it achieves that status in ways I can only call "classical," methods that most filmmakers don't even attempt anymore.

I won't indulge my questions and suspicions about what this film says about Anderson himself, because I honestly don't think he meant this as a self-portrait so much as an exploration of timeless ironies about artists and muses. (Others can obsess about that if they want: the Pop Culture Happy Hour podcast already has, in a conversation that interpreted the film far too narrowly.) I think these are distinct characters in a story all their own.

If you don't take Phantom Thread as a comedy first and foremost, or if you think that it's supposed to be romantic, then I think you will find the film frustrating. But if you see it as a satirical depiction of a kind of mutual madness that seems strangely recurrent in the world of artists, then I think you'll find much to enjoy here. Watching Phantom Thread I had that rare experience of being so "caught up" in the mastery of the film's artistry that I couldn't think about anything else, much less what I wanted to say about it. And as someone who has learned over 30 years to "take notes" for a review while watching a movie, that's a rare and exhilarating experience.

Suffice it to say that this film's strength and its weakness is in its stylistic perfection. Every shot, every line, every flicker of light, every performance (Leslie Manville is a joy), every edit, every flourish of its sumptuous and extraordinary soundtrack — I can't find anything I would change...

... except this: While I do think that Phantom Thread is a beautifully empathetic tribute to the women who often enable male artistic geniuses to do their best work, I also think it's particularly meant as a tribute to Alma Hitchcock. Life must have been difficult for Alma, playing that difficult and even humiliating role at Alfred's side, supporting him in his obsessions even when that included sexual preoccupations with Grace Kelly and others of that "type."

But for all of this film's evident empathy for its own Alma — in some ways, Leslie Manville's character Cyril, Woodcock's assistant, is the real "Alma" here — it never considers where its female characters come from, or who they are outside of their devotion to Woodcock. Yes, perhaps I'm slightly influenced by the political trends of this year, but that's not a bad thing, because those trends are trending in the right direction. Alma is an admirable character in what she demands from Woodcock, and in her agency in the relationship. But Anderson, the male artistic genius behind the camera, still falls short in his lack of curiosity about the women of Phantom Thread, just as he fell short in Punch-drunk Love (which I still think to be his most perfectly realized masterpiece) in developing Emily Watson's character.

Speaking of Punch-drunk Love, that film also had a sense of spontaneity, a sense that much of its magic happened before the camera without any forethought. I don't feel that kind of magic in Phantom Thread.

But I do feel it in The Florida Project...

...and that's part of why The Florida Project is my #1 favorite film of 2017.

#1

The Florida Project — dir. Sean Baker

https://youtu.be/WwQ-NH1rRT4

The Florida Project is the Disney movie of the year.

You probably know what I mean: Taking place just outside the borders of Disney World, this movie tells the story of what America's fantasies cost. It creates a divided world, in which the rich can come and go and indulge in pre-packaged make believe, while the poor struggle to survive day to day, kept conveniently out of sight. But where is the most impressive make believe taking place? In the imaginations of the children who, in their American poverty, are able to imagine their ways through living nightmares, even in the near-certainty of their pending ruination. This is the power of cinema, that a film like this can cultivate so many moments of explosive joy in the midst of so much misery and trouble.

The Florida Project is the most groundbreaking work of filmmaking I saw this year. It tells an extraordinary story, and yet it seems documentary-like in its authenticity: The soaring cinematography, the musical colors, the exhilarating editing, and the poetic resonances that accumulate over the course of the film seem to defy explanation.

How did writer/director Sean Baker (and co-writer Chris Bergoch) make this movie?

How did he outline such a complex story arc when so much seems to have unfolded spontaneously?

It's as though the Almighty commanded a crack team of guardian angels from Wim Wenders' Wings of Desire to descend upon these rundown Florida hotels just outside of Disney World to choreograph incredible moments of children at play, of helicopters hauling tourists back and forth in the background, of dangerous activity on the streets, of unpredictable weather. In reality, those angels are Baker and his team: They bring a spirit of patient observation, compassion, and empathy to this film that seems, well, divine.

Moment to moment, as we follow the unsupervised and sugar-high children who call the Futureland hotel — and other nearby hotels — home, their interaction seems entirely unplanned. They have unexpected outbursts. They seize upon, and riff on, the most unlikely conversational accidents. Their mischief is so original that it seems impossible that it was scripted — except, perhaps, the one bit of mischief that causes an emotional transformation of key relationships. Whether they're tormenting Bobbie the Futureland Manager, or climbing all over the motel as if it's made of playground equipment, begging for money to go get "free ice cream" from a soft-serv stand, breaking into motel utility rooms, spying on a topless woman at the motel pool, exploring abandoned housing projects (and playing in the crumbling asbestos, which they call "ghost poop")... they are completely convincing. I'm not sure how much of this is authentic play and how much is rehearsed, but whatever they case, these kids seem completely unaware of the presence of a camera.

Brooklyn Prince, playing Moonee — who eventually emerges as the film's central character, her arc bending toward heartbreak — gives a performance of such irrepressible energy that it's hard to believe any acting is involved at all.

I can think of very few films in which poor, desperate people are portrayed so truthfully, without any attempt to sentimentalize them or exploit their pain, and yet filmed with such a loving and respectful gaze. Bria Vinaite's performance as Moonee's mother is a thing of furious and fearless beauty. Her character, Hailey, could so easily have been detestable, but Baker wisely captures moments that reveal the devastating influence of absent fathers and mothers, so that Hailey is revealed to be resourceful and even generous in spite of her complete lack of education in adulthood, responsibility, or grace.

Hailey is so extreme that she threatens to overwhelm the movie whenever she's onscreen — but balance is provided by Willem Dafoe in his most surprising and endearing performance. As Bobby, the Futureland manager, he's almost reprising his role as Jesus, suffering for the sins of the world as he tries to keep the building from collapsing under the weight of its inhabitants' broken dreams. He's magnificent.

I found Sean Baker's breakthrough film Tangerine to be every bit as unique and rewarding as the film-festival hype had promised. But The Florida Project is a miracle.

And, like Phantom Thread, it has a scene in which an immature and emotionally unhealthy character orders one item after another off the menu, more food than any human stomach should hold. In Phantom Thread, Woodcock orders fine food beautifully prepared. In The Florida Project, Moonee orders everything off the greasy diner menu. The two orders perfectly capture the contrast in the two films' styles. Paul Thomas Anderson was aiming for gourmet, and he achieved it. But Baker was improvising, experimenting, and weaving together accidents with unknown actors in much the way that Terrence Malick does with celebrities in glamorous settings. And Baker cooked up a greasy mess that is every bit as meaningful and nourishing, if not more so, than Anderson or Malick could have made with the same material. I prefer the greasy mess. It's constantly, relentlessly surprising.

At one point, Moonee takes her friend Jancey (Valeria Cotto, also astonishing) to one of the wild edges of her neighborhood and climbs up onto a massive, distorted tree trunk. This, she announces, is her favorite tree — because it tipped over, but it keeps on growing. It may be the only moment in the film that feels scripted. But it's also a perfect summation of the film's unlikely beauty: Each one of these characters has been knocked down, and clings to a fragile existence in an overlooked corner of a country in decline. And yet each one keeps growing, in ways wondrous and strange, right before our eyes.

For me, the experience of visiting The Florida Project is an exercise in learning to love our neighbors: It's awe-inspiring, humbling, and holy.

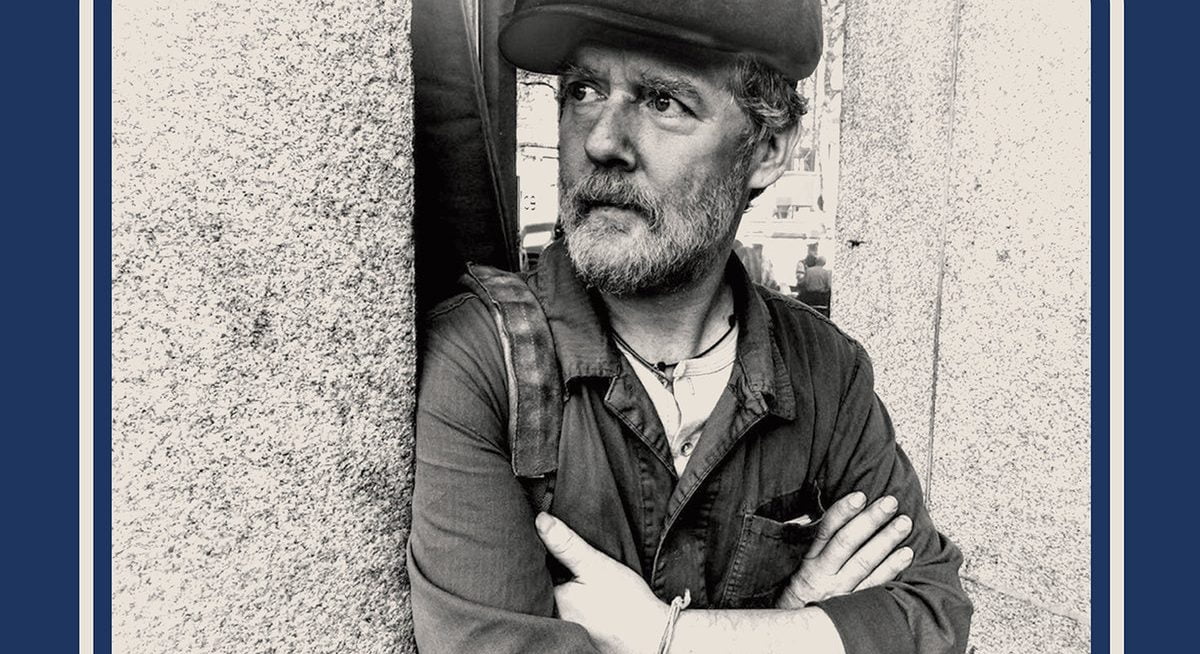

Wheels on fire

We're just a few weeks into 2018, and already the wave of protest music has risen high, led by The Decemberists and now Glen Hansard. Let it hearten you and give you a sense of good company, as we who believe in America's ideals of equality, liberty, and justice for all persist in supporting and strengthening the good things that remain during these days of the anti-American, anti-Christ, GOP wrecking ball.

Here's Hansard with "Wheels on Fire" from his new record Between Two Shores.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8DmugDwiVpU

You're building us up just to tear us down

You think that nothing's gonna stop you now

But I hear you're preaching from a nervous throne...

Your wheels on fire

Your one desire

Is to roll and rule over everyone

Come on let them do it

We see right through it

You can roll and rule

But we will overcome...

Overstreet's Favorite Films of 2017: #30-#11

It was a year of sequels that exceeded expectations.

It was a year of women — directors, writers, cinematographers, actresses — succeeding against the industry odds to deliver many of the freshest and most inspiring big-screen visions.

It was a year in which I found myself unmoved by many of the films that impressed friends and colleagues — most notably, The Shape of Water, Dunkirk, A Ghost Story, Baby Driver, and Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri. (I went in excited about what I'd heard; I came out frustrated by films that just didn't work for me.)

It was a year in which we turned to the movies for reassurance that there is still a benevolent imagination and a conscience at work in the world.

While I cannot say that this year gave me many films that will last as all-time favorites, there were so many that made the tour memorable and surprising. Here are quick notes on #30 through #11 of my 2017 Favorites List. (I'll post the Top 10 next week.)

#30

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FRlUJrEUn0Y

Jane — dir. Brett Morgen

I learned a lot from this film... like the fact that Jane Goodall was married to Jonathan Pryce, and that they became the parents of Owen Wilson. (Okay, not really... but the resemblances are uncanny.)

And I've learned a lot from reading about this film — primarily, that a lot of people I respect really, really dislike Phillip Glass. Huh. I'm grateful, I guess, that I do not share their opinion. I barely noticed the music in this film — I think it served to effectively sew together a lot of "found footage," typical National Geographic Special stuff (the kind that makes me suspicious that some things weren't staged), and "glamour shots" of Goodall's famous legs.

But seriously — I'm more amazed by the abundance of footage of Jane's early work that makes such a complete narrative possible than I am by the footage of her up-close-and-personal engagement with the chimpanzees.

This is the kind of movie I would have been warned about in my childhood community of evangelical Christians. They would have condemned this due to their rejection of Jane's scientific observations about evolution and her decisions about career, marriage and parenthood. (Many, I'm afraid, would still condemn it.) I'm grateful for teachers — men and women of deep faith and a deep respect for reason and truth — who came along to set me free from the notion that a work of art reflecting one human being's ideas and decisions is automatically a film endorsing and celebrating all of those ideas and decisions.

Jane doesn't strike me as any kind of indoctrination or screed. If it recommends anything, it recommends that we should be brave, curious, and careful to recognize that both good and evil are active in nature, and that we must nevertheless love the created world for the greater good. What kind of church would object to such things? (A church that would support a science-hating, educating-hating, woman-hating President, I guess.)

This film captures a testimony, but it does not preach — it leaves us room to observe Jane and come to our own conclusions (like, for example, realizing the folly of coming to anything at all like ultimate conclusions in a world as wondrous and complicated as this).

In this film, Jane's testimony strikes me as both an inspiration and a cautionary tale. Somehow, I've never known her story. I'll go on thinking about her for a long time. Her fearless curiosity, her compassion, and her reverence for the created world minister to me (to preserve a word I learned in childhood) in ways that fear, ignorance, and condemnation do not. And they remind me of things I learned from those evangelicals' own Scriptures: the importance of casting out fear, and of attending to "what has been made," because creation is full of testimonies about what some call Mystery or Glory or Love — what (or better whom) I call God.

The natural world is a language of its Maker, full of living words that go on speaking meaningfully to us. Jane and Janemake me want to attend to them better — with humility, discernment, and conscience.

#29

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fTvy8ab1NSo

The Trip to Spain — dir. Michael Winterbottom

The subtler development of themes over the course of the journey, the constant critique of these two unceasingly competitive egos, the correlations between the past (described in show-offy tour guide monlogues) and the immediate — these make every mundane exchange resonate with something more. (And something Moor, or, better, something Moore.)

I want to be the jogger that Steve Coogan is.

I want to prioritize family the way Rob Brydon does.

I want to eat everything they eat.

I want to drive the roads they drive.

I want a road-trip buddy who enjoys improvisational sparring.

And yet...

It's somewhat disappointing how preoccupied this film is with revisiting highlights from earlier material, with diminishing returns. (Again with the Roger Moore, Sean Connery, and Al Pacino! The Moors/Moores sequence is exasperating.) I'm increasingly weary of the celebrity-impressions competition between these two; I'm increasingly sympathetic with the unimpressed women at their table who demonstrate the patience of saints.

But still, The Trip to Spain is a pleasure and a palate cleanser after a summer of disposable noise and typically overstuffed "big" movies.

#28

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=id0HEelDIuk

Their Finest — dir. Lone Scherfig

A film set in 1940 — wartime, in the months after the dramatic rescue effort during the Battle of Dunkirk. And I love it. It surprised me. Just when I thought I had it figured out, it would turn into something more than I expected. And here's the biggest surprise: It stars Gemma Arterton.

Their Finest was my favorite film about Dunkirk released this year. It's a movie that *knows* it's a movie, that wears its genre conventions on its sleeve, and that fumbles those conventional moments as often as it succeeds with them. But along the way, it finds flashes of real life that I found surprisingly affecting — surprising because the short blurb I read prepared me for a light romantic comedy. You can find romantic comedy here, but this film has higher ambitions.

And that should be no surprise It's directed by Lone Scherfig, who directed An Education.

When I wrote Auralia's Colors, I was determined to avoid any scenes that felt familiar in the fantasy genre — and so I avoided battle scenes, scenes of wizards facing off with monsters, etc. While there *are* wars in the story, we learn about them from their distant repercussions on others, or by picking up hints about them in dialogue and rumors. I find that much more interesting because the Big Spectacle Events have been done so often that they rarely ever interest or move me.

Their Finest felt like a wartime film that showed me other people, other places, other aspects of war that I'm not accustomed to seeing. And as I watched the film's lead characters — screenwriters — applying themselves to their art even *during* air raids, I was moved to see the assertion that artmaking is still worth doing even in such scenarios. (Yes, their art is compromised — it's the studio system of filmmaking, and the movie acknowledges this outright in ways that make us laugh and groan.)

Also, this movie has Bill Nighy. Who can make any more worth seeing (except, perhaps, Love, Actually).

I look forward to revisiting this for the subtle pleasures it offers.

#27

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5hKtgrj7UXo

Graduation — dir. Cristian Mungiu

This is what we'd see more often if the Dardenne brothers were more cynical. (Dire-dennes? Dark-dennes?)

I have no doubt that this is not meant as satire; this is the way the world works in so many societies (including, increasingly, my own). But Cristian Mungiu's extremely narrow focus on corruption makes it difficult for me to be completely caught up in his vision. I was mightily impressed with Mungiu's 4 Months, 3 Weeks and 2 Days, and Graduation is clearly a masterful work from the same truth-telling imagination. And this is a film about subjects that I care about deeply — namely, the value of integrity, and the importance of becoming a "living word," an incarnation of one's professed beliefs. Graduation, on that subject, would make and interesting double-feature with Ang Lee's The Ice Storm: A parent's integrity is their most influential form of teaching.

There is much to admire here, from the understated performances (although Lia Bugnar plays one of the most zombie-fied victims of a loveless marriage since Allison Janney's practically comatose character in American Beauty) to the meaningful complexity of some of the images (I wanted to grab screenshots of several moments just to study them, especially those in which religious icons are peering out at us from edges of the frame).

Mungiu's critique of Romeo's quid pro quo relationships is so obvious and relentless from the beginning of the film that Graduation becomes increasingly didactic as the movie unfolds, to the point where plot twists start to feel like they're merely prolonging a conclusion that we all know will bear a bitter sting of irony. (By contrast, the Dardennes' own Rosetta seems an even more remarkable achievement is exploring Kafka-esque conditions with efficiency and never having a moment that feels like The Lesson.) When we arrive at the scene where a small child, representing Romania's future, stares up at a duplicitous adult and asks "How should I behave?", the complexities of the film's many braided storylines begin to seem unnecessarily extravagant.

Still, I cannot help but marvel at the craftsmanship, and many of my favorite critics are promising that a second viewing will be more rewarding.

#26

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=k_jgf_LHEis

World of Tomorrow Episode Two: The Burden of Other People's Thoughts — dir. Don Herzfeldt

More complex than Blade Runner 2049, more emotionally engaging than The Last Jedi, and funnier than any comedy I saw this year, Episode Two picks up where World of Tomorrow left off by taking the ideas that made the original my favorite short film for classroom discussion and spinning them in wild new directions.

Emily Prime has become my favorite big-screen child, and her clones have the capacity to terrify us and break our hearts for their sufferings. Herzfeldt's experimentation with colors, textures, and shapes (They Might Be Giants fans will have reason to celebrate here) take us on journeys so surreal and abstract that we feel, after the film's brief running time, that we have been on a journey more substantial than most feature films dream of providing.

While I can't imagine a sequel that matches the perfection of the original, I'm grateful to have had the chance to revisit Emily, and grateful for these sobering warnings about where technology is taking us. Alas, I am not optimistic about humankind's willingness to listen and heed these warnings, but for those with eyes to see, this thing will scorch your eyeballs with the truth.

#25

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lKq7UqplcL8

Kedi - dir. Ceyda Torun

Things this film is really about:

God.

Love.

Human Beings.

Mercy.

Generosity.

Particularity.

Paying attention.

The poor.

Cultural diversity.

Resourcefulness.

Aliens.

Survival.

Therapy.

The windows and doors of Istanbul.

The rooftops of Istanbul.

Shoes.

Istanbul political tensions.

Various meats and cheeses.

Cats.

#24

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EsozpEE543w

T2: Trainspotting - dir. Danny Boyle

"Nothing. Emotional attachment, that's all."

That may be what brought Danny Boyle back to this, his most memorable — and polarizing — material, and what will bring this film its audience.

But still, Boyle's version of THIS IS 40 works is, in my estimation, a more interesting KNIGHT OF CUPS than KNIGHT OF CUPS was. That is to say, it's a better representation of mid-life "What's It All About — and How Do I Make Something Of It?" panic.

I'm not sure what I'll think of this tomorrow, but while it's playing, this has beauty, brains, heart, and a surprising amount of soul. The marriage of colors, rapid editing, music, adrenaline, and an inclination toward compassion here reminds me more of Millions than any other Boyle circus.

Cinematographer Anthony Dod Mantle shows some new moves here that are breathtaking, including a simple swerve during a confrontation between Begbie (Robert Caryle) and his son that I can't believe I've never seen in a movie before; it reminded me of being startled by that brilliant close-up framing of Cruise and the Pre-Cog in Minority Report—a simple framing of two bodies in a space that makes you wonder why no one's thought of it before (as far as you know).

Sure, as with most of his work, it's a bit too much movie and bit too short on film. I really didn't need for this to climax with a Blade Runner-lite smackdown. Still, Boyle's a magician. He could make a movie about a routine custodial sweep of an office building and make it more visually exciting than most action movies. Here, he's a craftsman at the peak of his powers.

P.S. You've got to watch the conversation between Boyle, McGregor, Carlyle, and Miller in the DVD extras, if only to watch Boyle try to explain what "meta" means to a wide-eyed McGregor and a skeptical Carlyle. And Miller sits there looking like he'd rather be anywhere else in the world.

#23

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VSB4wGIdDwo

Wonder Woman - dir. Patty Jenkins

Well, what do you know?

Here's a superhero movie that is also an exhibition of beautiful image composition; first-rate performances from all involved; substantial mythopoeic implications; remarkably conscientious reflections on good, evil, and the nature of violence; wry comedy; cleverly unconventional Christology; and profound reflections on the evils that men (specifically) do. What's more, it acknowledges the complicating reality that there is "so much more" about humankind, a mysterious quality that suggests we might hope to receive better than "what we deserve."

I'm rather astonished to say this about a superhero movie, and downright gobsmacked by the fact that this is a DC movie, and that Zack Snyder (my nemesis) is involved... but I really admire this film.

Kudos to Patty Jenkins for one of the best-directed superhero films I've seen. Kudos to Chris Pine for once again making everything he's in a little better than it might have been. And wow — Gal Gadot. Sure, she seems to be made for movie cameras, radiant in the same way that Audrey Hepburn was, but it's a relief that the camera never treats her as a sex object, never ogles her like she's in Playboy, never presents her as a product designed for men. Lucky for Gadot, she's allowed to demonstrate (where so many other actress are not) that she's much more than just a pretty face — as an actress, she's funny, she's surprising, and she makes comic book dialogue sing. (Now, let's see what she can do in a movie that doesn't have an obligation to blow things up!)

I'm sure that I'm influenced by the fact that this is one of those all-too-rare films in which the great David Thewlis gets to play a prominent role. I think that his performance in Naked is still the most astonishing lead performance by an actor in a film I've ever seen.

Unfortunately... well, the finale of this film is its least satisfying stretch. It runs out of originality and settles for a by-the-numbers showdown. I wish DC had learned from Doctor Strange that there are other kinds of conclusions, or at least other kinds of showdowns that can send us out on a note of "Wow, we've never seen that before."

#22

https://lookingcloser.org/blog/2017/08/09/hawkins-and-hawke-paint-a-radiant-romance/

Maudie — dir. Aisling Walsh

This year, Sally Hawkins gave an extraordinary performance as an afflicted woman who, disrespected and practically silenced, finds unlikely love with a "monster" of a man. No, I'm not talking about The Shape of Water, a film that I didn't like much at all. I'm talking about a film based on a true story: Maudie, which also stars Ethan Hawke in a memorably gruff and complicated turn. If you haven't seen it, you should. It's beautiful.

#21

https://lookingcloser.org/blog/2017/08/30/robert-pattinson-has-a-good-time-as-bad-guy/

Good Time - dir. Benny and Josh Safdie

#20

https://lookingcloser.org/blog/2018/01/09/spielberg-invites-you-to-post-dramatic-stress/

The Post — dir. Steven Spielberg

#19

https://lookingcloser.org/blog/2017/04/30/the-haunting-of-a-half-hearted-woman/

Personal Shopper - dir. Olivier Assayas

Kirsten Stewart is mesmerizing as one of the most complicated and interesting characters of this or any year. It's a haunted house movie. It's a stalker thriller. It's a consumer-culture critique. It's experimental. It's mysterious. I can't say I really understand it. But I was enthralled all the way through, and I have given up many hours to reading the many fascinating interpretations it has inspired. Even better, it shows that the director of the magnificent SUMMER HOURS is one of the most unpredictable directors alive.

#18

https://lookingcloser.org/blog/2017/05/27/i-believe-in-doctor-jenny/

The Unknown Girl - dirs. Jean-Pierre and Luc Dardenne

The world's most consistently masterful filmmaking team delivers another film that quietly serves as the antidote to 95% of our available new-release options.

Magnificent and timely, The Unknown Girl is challenging me take my eyes off of the soul-bruising abuse happening in the headlines hour by hour; it’s reminding me to return to the unglamorous but necessary and ultimately redemptive work of patient, diligent, disciplined love for those who need it most. Not exactly the kind of blurb that sells you on the movie, is it? Well, that's the problem: The true and victorious power in the cosmos is the one you must seek out. It speaks in a still small voice. You have to learn to want it. And when you do, it begins to dazzle you gradually until you too become frustrated that others look at you funny when you tell them what kind of movies you like.

I love the Dardennes, and while this does not yet rank for me as one of their very best, it is another incredible film that knows more about love than most films Americans will see in their lifetimes.

#17

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rGQUKzSDhrg

https://lookingcloser.org/blog/2017/02/12/the-lego-batman-movie-trumps-expectations/

The LEGO Batman Movie - dir. Chris McKay

What can I say? I laughed so hard the first time that I doubted my judgment. Was it really as smart, as intelligent, and as phenomenally executed as it seemed? Second and third viewings were just as rewarding. And in a year that was painfully short on occasions for laughter, this movie was medicine. Sorry, Christopher Nolan, but I have a new favorite Batman movie — the one that gets the character better than any others have, and that is wise enough to see the biggest problems with the whole Dark Knight mythos.