Shrek (2001)

A Re-Introduction

to the Looking Closer Review of Shrek

The name Eric Metaxas first came to my attention not because of his bestselling Bonhoeffer biography, but because of his review of Shrek in Books and Culture. I wasn't a huge fan of Shrek, but upon reading his interpretation of the film, I felt compelled to defend it. Having covered early reviews in my column at Christianity Today a week earlier, I came back to wrestle with Metaxas's reaction in detail. A week later, I documented an ongoing debate among the magazine's readers and moviegoers about the controversy.

I suspected that our differences wouldn't end there — and now, 18 years later, my suspicions have been more than confirmed, as he has in recent years become an apostle of Trump-ism, championing the "leadership" of man who has demonstrated that he is an unrepentant sexual assailant, a relentless bully, a pathological liar, and a white supremacist. But we're not here to examine Metaxas's integrity.

We're here to revisit Shrek, as I restore a long-missing piece of the Looking Closer archives. Much of this review appeared in my Christianity Today coverage, which I then revised and expanded for this site. Here it is.

The Original Review

Both Anthony Lane at The New Yorker and Eric Metaxas at Books and Culture are popular critics on important platforms. And both of them are upset about Dreamworks’ new animated movie. They think Shrek is trying to teach us that we don’t need fairy tales.

With all due respect to these writers, I’m a little surprised that they’re missing the actual target of Shrek’s snarky and irreverent story.

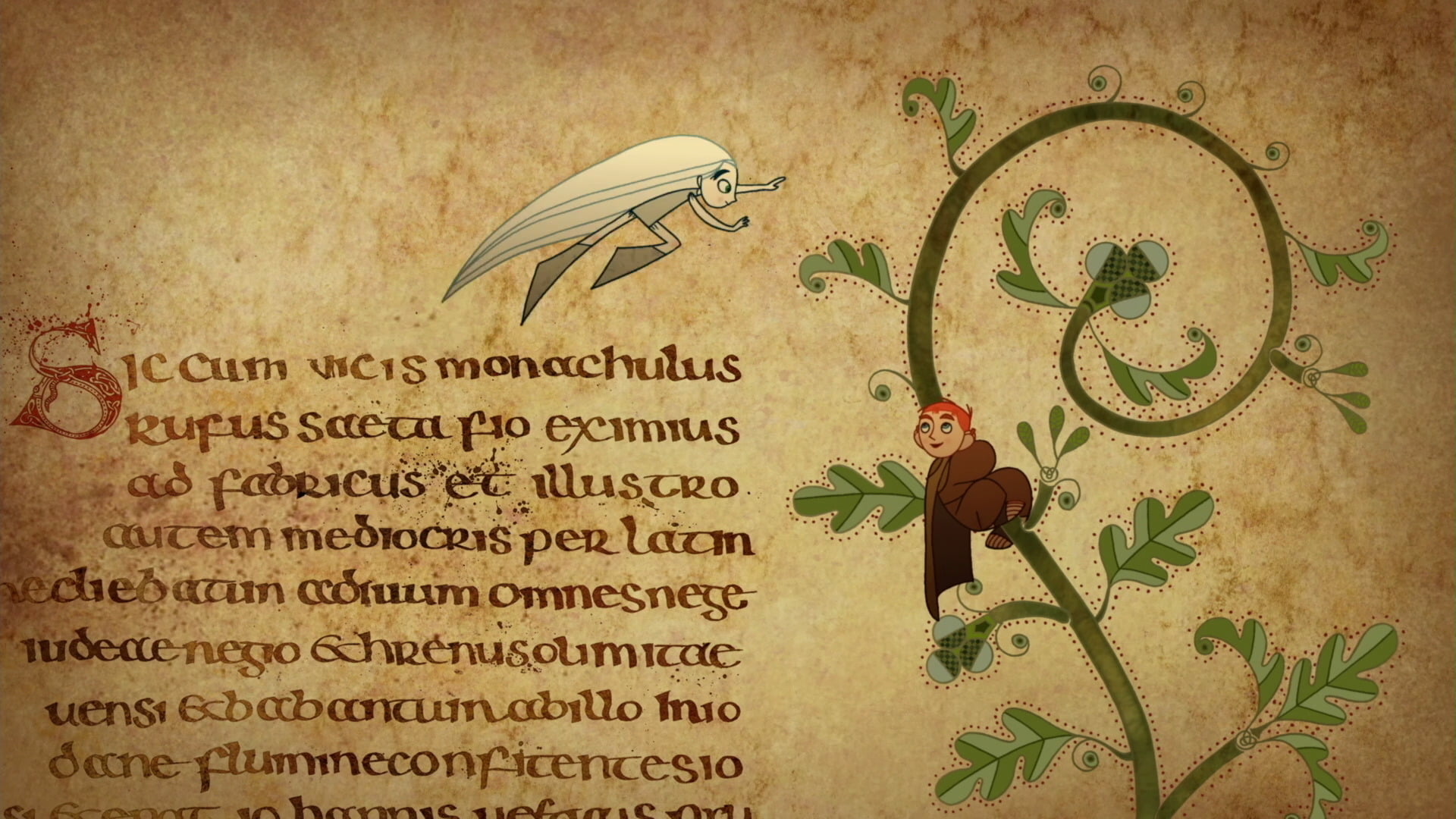

Let’s start at the beginning: Shrek is a somewhat subversive fairy tale about a reclusive swamp-dwelling ogre who strikes a bargain with an egotistical, power-mad overlord.

The disgruntled ogre’s swamp has become crowded with fairy tale characters cast out of the castle where the wicked ruler Lord Farquand routinely tortures and abuses them. Shrek, demanding to be left alone in his unhappy existence, marches in to the castle and makes a deal: In exchange for a little peace and quiet back home, he agrees to rescue an imprisoned princess from a fire-breathing dragon so the conniving Farquand can marry her and become king. With sidekick Donkey in tow, Shrek ventures off on a journey that will teach him that the world does not have the right to call him ugly. Beauty — surprise surprise — is more than skin deep.

Even as it embraces a familiar fairy tale structure, Shrek pokes fun at the biggest Fairy Tale Dismemberment machine of all: Walt Disney Studios. The movie exuberantly and sarcastically skewers the clichés that have become Disney’s bread and butter, even as it pulls off some heart-warming and surprisingly meaningful storytelling of its own.

It’s also the flashiest animated feature yet from DreamWorks, the studio led by former Disney exec Jeffrey Katzenberg. With enthusiastic vocal performances by Mike Meyers (Shrek), Eddie Murphy (jabbermouth Donkey), Cameron Diaz (Princess Fiona), and John Lithgow (the moo-ha-ha menace Farquand), the movie never applies the brakes, plunging headlong through action, machine-gunning jokes, and innumerable pop culture references. It has an advantage in its devil-may-care attitude, which gives it a fresh and unique energy; but that same advantage dates the movie, shortening its shelf-life… and it makes the film off-puttingly cocky and arrogant. This doesn’t kill the fun, but it does unfortunately taint it with unnecessary flaws.

Still, while the film has an attitude problem, its primary observations are sound.

Shrek doesn’t want us to shrug off the beloved fairy tales of ages past… or even to critique them. No, this movie is dependent on the very fairy tale models that it lovingly lampoons. Rather than condemning traditional stories, I think Shrek is slamming what Disney has done to those stories by sterilizing them.

Disney studios and animators, with films like The Little Mermaid and Pocahontas, enforce for children that only a certain Barbie-esque look is “beauty.” They also perpetuate a sort of pop-culture paralysis, hammering into our heads the necessity of Diva-delivered pop anthems at any emotional turn in the story.

Worst of all, Disney force-feeds us contrived happy endings, contrary to the original fairy tales that aspire to tougher truths. Some of our best fairy tales sometimes deliver tragedy and horror as well. (Read any Brothers Grimm lately?) Disney’s relentless happy-ending hysteria sets kids up for disappointment, and puts pressure on them to live up to superficial and materialistic standards of excellence. Better to take the long, hard road to a Joyful Ending — a substantial vision of hope — than to sell young imaginations a happy ending full of artificial sweeteners that eventually cause cancer.

[Update: Plenty of readers are answering Eric Metaxas’s critique in Books and Culture with objections.]

I will agree with many critics that Shrek is reckless in its humor. Sex jokes and double-entendres are inappropriate in movies for small children. And surely storytellers working with such vast resources could find something more inventive than the fart-jokes that fill what passes for “all-ages entertainment” in this country.

But to some extent I agree with David Ansen at Newsweek, who asks, exasperated, “Why can’t scripts this smart and economical be written for flesh-and-blood actors?” He calls recent CGI movies like Shrek and Toy Story “throwbacks to the classical style of Hollywood filmmaking, where the story came first, the stars knew their place, and the movies were made to please the widest possible audience without stooping to the lowest common denominator.”

I also sympathize with Salon.com’s Stephanie Zacharek and The New Yorker‘s Anthony Lane, who both express dismay at the film’s state-of-the-art animation. Lane summed up the complaint: “I don’t recall firing off indignant letters to Warner Bros. to complain about Wile E. Coyote and his insufficiently detailed snout. All I ever required of Road Runner was a drastic simplicity … and I still want the same thing.” Yes, digital animation can do marvelous things for movies. (Check out the effects in Moulin Rouge!) But must we waste resources and energy so we can pridefully show off our technical prowess in a kids’ cartoon? Toy Story‘s animation seems a good balance of skill and simplicity. Shrek, with its swirling 3-D Donkey fur, is perhaps taking things a touch too far. Don’t distract us from the storytelling with the latest technological flourish; use it only if it serves to enrich the storytelling.

Still, Shrek‘s pros outweigh its cons, making this delightful entertainment with a refreshingly honest message: You don’t have to look like Cameron Diaz to be beautiful. Beauty is a deeper thing. And plastic surgery is a waste of money. It is part of society’s downfall that we embrace the Princess Fionas when they’re glamorous rather than real.

While we owe many thanks to Disney studios for some of animation’s highest achievements, they have been asking for a rebuke like this for a while. Early on in the movie, when one of the characters prepares to break into a platitude-heavy pop song, the grouchy ogre furiously tells him to shut up, and the story marches on. Kids and grownups alike laughed and applauded appreciatively. For those of us weary of Disney formulas, DreamWorks’ Antz and Shrek are evidence of animation’s exciting future. Disney is like pop music for the masses, clean, cheesy and dreamy; DreamWorks is rock ‘n’ roll—rebellious, rowdy and real. Let’s hope Disney is paying attention. And let’s hope Katzenberg has worked out his grudge, and can now go on to stronger storytelling, leaving cheap shots and in-jokes behind.

The Coen Brothers: Winning With Losers

My friend Damian Arlyn has a new piece up at Veritas Journal, and it's worth reading. Here's a clip:

Whatever the reason for their fascination, Joel and Ethan Coen seem determined to be the movies’ “patron saint(s) of losers.” Like that biblical passage that declares that the “last shall be first, and the first last,” their choosing to shine the light on the conquered rather than the conquerors could almost be considered an act of grace or a sort of “karmic justice,” balancing the cosmic scales in a society that rewards champions and marginalizes everyone else.

This brings back memories of that long night of frenzied emailing, several years back, with Matt Zoller Seitz (RogerEbert.com) about the theology of the Coen brothers' films.

Chungking Express (1994)

Behold! I'm running my first lap around a new track: a 500-words-or-less film review format. What can I accomplish within tighter constraints? This will be give me practice in saying more with less — good exercise for any writer.

A few thoughts on

Wong Kar Wai's Chungking Express

[For this third viewing, I watched the Criterion Collection edition. These comments contain some spoiler-ish plot points.]

In a jukebox, three display-only CDs pirouette, catching and refracting rainbows and golden light, seemingly animated by music, and presumably full of their very own songs — and as they spin, their edges never touch.

It's a perfect picture of the close-but-not-quite romances between characters in the two Hong Kong stories that make up Chungking Express, Wong Kar-wai's whimsical, melancholy 1994 masterpiece.

Look at these two mopey cops—played by Takeshi Kaneshiro and Tony Leung—both recently jilted, both caught in a routine circuit of their beat and their hangouts. They're both bound for close encounters with mysterious women: one a drug dealer trying to escape her boss's tyranny (Brigitte Lin, solemnly opaque in sunglasses and a yellow wig); the other, a minimum-wage cafe worker (Faye Wong, so wide-eyed and mischievous that she probably inspired Jeunet to make Amelie).

Okay — so, you can picture the jukebox. Now picture a bin full of tins of canned pineapple, containers marked with expiration dates to remind us that they will soon pass their prime, and their time of maximum sweetness is running out. That, too, speaks about these characters.

Or, dig if you will the pictures of goldfish aquariums, insisting that this is a story about hermetically sealed worlds in which characters drift and dash, dreaming of worlds beyond their routines, surrounded by reflections and distortions that make us wonder who's dreaming whom. (Note how often characters are seen through glass, pressed against glass, confined by glass.)

In both stories, luminous women are illusory, elusive, enigmatic. And the more I spend time with this film, the more I suspect they're just fantasies — Mandarin Pixie Dream Girls living in the imaginations of crush-prone police officers — not real characters caught in unexpected encounters. Both women seem curiously maternal: Purse-carrying Woman in Wig doesn't want a relationship but leaves a birthday card for her boyish guardian; Cafe Counter Girl advertises herself with every move of her window-washing dance, but what she really wants to do is clean her man's house, make his bed, dust his shelves.

Uniforms play a big part for both men and women here. And as audiences long to see these characters break out of them, these restrictions are the source of the energy, the constraints that control the tension of viewers' longing. Chastely gazing at one another in private spaces, their longing burns brighter than any sex ever could.

Still, while its ideas of love are as feverish as an adolescent's dream, I can't deny that Wong's world is one of lasting, substantial pleasures. These flirtations may be as glossy and shallow as the soundtrack's pop songs, but they represent longings for magic, for transcendence, as deep as any "California Dreamin'."

It's also a masterwork of crowded composition, breathtaking montage, and glorious motion. These characters lean into glass, enraptured. And so do we.

(Note: This is by far the very best film in which Jim Davis's Garfield has a major role.)

Elf (2003)

Imagine... a new band of superheroes made up of characters who were raised by inhuman species:

- Princess Mononoke, raised by a wolf goddess!

- Mowgli, hero of the jungle, raised by wolves!

- Tarzan, another hero of the jungle, raised by apes!

- Peter Pan, who was raised by birds! (It's true. Read J.M. Barrie's The Little White Bird.)

They would fight the Penguin, of course.

But who would be their leader, the one to make inspiring speeches, the one to keep them hopeful during their darkest hours?

How about Buddy, the boy raised by elves?

[The following is an amalgam of my original Looking Closer review and commentary I contributed to my Christianity Today Film Forum column on November 1, 2003.]

In case the title isn't a big enough hint, take note: Elf is not a story about the birth of the Christ child.

I say that because some Christian media reviewers are lamenting the lack of Jesus in this movie. They would, of course, complain about irreverence if Jesus was in this movie.

Now that we've cleared that up, let's consider what Elf really is:

Elf takes place in that sugary realm of holiday myths about Santa, reindeer and (surprise!) elves. While its tone veers from childlike (A Muppet Christmas Carol) to childish (Christmas Vacation) and then way out into sheer absurdity (Pee-Wee's Big Adventure), it remains clearly a fantasy, one that tells [imagine that I am switching now into my Movie Trailer Guy voice] a formulaic tale about unconditional love, the value of wonder, the importance of finding one's place in life, and the rewards of having faith in things unseen.

Fortunately for all of us, Elf is just funny enough that, after the whole family has made the trip to the shopping-mall cineplex to see it for the first time, you might find Mom and Dad sneaking back to the theatre on their own just to laugh their way through it a second time.

You might... that is, if Mom and Dad find Will Ferrell funny.

It offers 95 minutes of high-spirited, laugh-out-loud holiday silliness, and, in its endeavors to become a Christmas favorite, it avoids the usual bottom-of-the-joke-barrel banality that cheapens most SNL-based movies. But Will Ferrell is one of those Saturday Night Live comedians—the polarizing personalities who audiences tend to love or hate. If you find his man-child personas amusing, you'll probably love Elf.

It tells the story of Buddy (Ferrell), a grown man who works as a toymaker with Santa's elves at the North Pole, thinking all the time that he too is an elf. Buddy doesn't realize that he was born elsewhere, or that his real family lives in Manhattan. An accident "delivered" him to the North Pole when he was an infant, and jolly old Saint Nick (Ed Asner), unsure what to do with the baby, handed him over to the sullen, stammering Papa Elf (the perfectly cast Bob Newhart) for an education and a job. And now, Buddy's an enthusiastic part of the team, even if he is beginning to wonder why his stature is so disproportionate to his peers.

When Buddy learns, finally, the reason that he stands out from the crowd, and discovers the explanation for his lack of elf-like talents, he sets off to find his real family. He arrives in New York and marches right into the office of his father, a Scrooge-like children's lit publisher (James Caan). Needless to say, his arrival is not exactly welcomed, and the ensuing trials are traumatic for dear old Dad, baffling for the big "boy," and a laugh-riot for audiences.

In spite of the outrageous premise, I'll venture to guess that you too will find Ferrell's performance irresistible. I was happy to suspend my disbelief as he bring his man-child whimsy into the middle of a surprisingly realistic Manhattan. Wait until you see him ignore Papa Elf's advice about bubble gum, or his first experiences with crosswalks, rotating doors, or escalators. His courtship of a wide-eyed beauty (Zooey Deschanel) seems doomed to failure, but it's surprising how much chemistry this goofball and his disillusioned date discover. Buddy's simplistic views of life, in which people's names are either on the Nice or the Naughty List, make for many memorable confrontations—his first encounter with a department store Santa may be the year's funniest scene.

The North Pole episodes are also a hoot and a holler. Director John Favreau cleverly incorporates his human cast with the backdrops and puppets of those beloved Rankin-Bass Christmas television classics like Santa Claus Is Coming to Town and Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer. Even the old snowman narrator, formerly voiced by Burl Ives, makes an appearance. This makes for a unique collage of environments, in which Favreau makes use of some of the same forced-perspective methods that Peter Jackson employed so well to make men tower over hobbits.

Watching Elf, I caught a glimpse of how another recent Christmas movie packaged for family entertainment — Ron Howard’s ill-conceived How the Grinch Stole Christmas — might have been better. There’s no spooky or gaudy makeup, very few big-budget effects, and the story is full of simple setups that allow for high jinx that feel like the fruit of inspired improv. While both films star talented improv comedians who give the proverbial 110%, Elf is likely to inspire annual visits, where The Grinch seemed intent on annoying and exhausting audiences. Elf is an enjoyably modest, playful, low-stakes affair; it does so much with so little. The Grinch was a turkey overstuffed, overcooked, and drowning in sauce. (That wasn't Jim Carrey's fault—I maintain that his performance was outstanding in spite of his gaudy, overcrowded context.)

This flimsy Scrooge-redemption story doesn't put on the weight it might have if a gifted screenwriter had imagined a more ambitious narrative. But frankly, I like Buddy just the way he is. Christmas movies are prone to being preachy, and sometimes a stack of highly decorative cookies is just the right thing in a season full of stress. It fumbles its way to a frenzied finale that feels more like a chore than a victory lap, but so long as Ferrell is onscreen, it's fun.

The first time I saw it, I smiled and shrugged. Since then, it's become a staple, a goofy ride on a carousel of holiday favorites. It won't change you, but it might get you hooked on its frivolous high.

[And now I can't stop thinking about the potential of a Buddy-focused force of Christmas-season superfriends. They just might save the world.]

24 Frames (2018)

Thanks to Jessica Mesman Griffith, the new editor of Good Letters, the Image film blog, I am back writing about movies again for my favorite journal about art, culture, and faith.

In my many years of writing reviews and essays about cinema, my most satisfying and rewarding experiences took place during the years I contributed perspectives on movies at Good Letters. I published a hundred essays there, covering films as distinctive and different as A River Runs Through It and Let the Right One In, Man on Wire and Empire of the Sun.

And I'm also delighted that my first subject is the enigmatic, meditative, and magical film by Abbas Kiarostami called 24 Frames.

It's not just a review. It's a personal essay organized into nine short meditations inspired by the film. Some are personal reflections about ways in which my life correlates with Kiarostami's vision, and some are direct examinations of the art and its beloved artist.

Here's how it begins...

1.

We’ve been watching the bird feeder. As the day comes into focus with the bedroom window’s frame, the light catches steam rising from our morning mugs like smoke rising from sacrifices on altars. Anne and I attend, blank journals propped like tents in our laps. We are not alone. Our cats, Mardukas and Zooey, keep vigil.

The stage is set: the background, a stand of slender trees; the foreground, a moss-upholstered fence. The cast? So far, only Alan: That’s what Anne has named this pudgy, defiant squirrel who lashes his tail at the salivating, trembling cats.

Suction-cupped high on the glass, a bowl of golden seeds beneath a plastic awning looks like a see-through balcony. The bird feeder prisms the sunrise—first red, then pearl—summoning a shimmering danseuse to slowly pirouette on our bedroom wall. This miasma, Anne once said, looks to her like the Spirit christening the apostles’ heads as they sang unfamiliar languages.

Our hushed anticipation before the frame feels particularly promising today because I engaged in a similar ceremony last night: 24 times, in fact. I watched Abbas Kiarostami’s film 24 Frames. And it tuned my senses to savor pregnant pauses, readying me for surprise.

2.

In a 150-seat shoebox at the Northwest Film Forum, seated with eight or nine silent strangers in hard, unfriendly seats, I worried: Would this be worth it?

The title 24 Frames refers to two dozen short films just under five minutes each. Each one reveals a single photograph of a view—a landscape, a wilderness stage, a pastoral scene—that Kiarostami captured, often through a window. But as we stare into big-panoramic snapshots, those ocean waves advance, those storms roil—and, in an exception, a 1565 painting by Bruegel the Elder called “The Hunters in the Snow,” a dog meanders through the scene. Digital artists, at the photographer’s direction, have conjured dreamlike action within a frozen moment. Snowflakes drift. Crows, pigeons, gulls, and ducks glide, complain, and agitate. Thunder activates amorous lions. A shadow heaves at the screen’s edge, then stands: a slumbering cow, awakened by the herd. In a rare view of human beings, Muslim tourists ogle the Eiffel Tower while pedestrians pass without pausing.

Some cynical critics have called these pictures “screensavers.” At The Filmstage, Giovanni Marchini Camia writes, “The result, it must be said, is … often quite tacky.” And sure enough, two viewers at our screening surrendered by the third frame, tiptoeing down the aisles to escape what they could not quickly comprehend.

But almost all of us were slowly undone by the film’s insistent whisper.

Read the whole article — Parts 1–9 — at Good Letters.

Overstreet Archives: The Matrix Trilogy (1999 – 2003)

In "Overstreet Archives"...

...I dig up early reviews and articles that I inadvertently left behind somewhere along the road between the late-1990s and today. Sometimes I never got around to reformatting them for a new version of the site. Sometimes I took them down because they were in dire need of editing or proofreading. Whatever the case, here they come.

But let's face it:

The design of LookingCloser.org isn't the only thing that has changed since the late '90s. The writer has changed, too. So I may interrupt the text of these early reviews with updated commentary or corrections as I encounter—and argue with—earlier versions of myself.

Let's begin...

...with a series that made me feel out of step with my generation.

Almost everyone around me loved The Matrix, and then they seemed disappointed by the sequels. But I was in the other lane, heading in the opposite direction. Frustrated by the original, and far more excited about other sci-fi films playing in theaters nearby, I didn't get excited about this epic saga until its closing chapter, The Matrix Revolutions. Why? Well, the reviews will explain.

Here are my original articles, with new notes, on The Matrix (1999), The Matrix Reloaded (2002) The Matrix Revolutions (2003),

The Matrix (1999)

[This is an abridged edition of the original review, published on the occasion of the film's first theatrical release.]

If you like science fiction, Keanu Reeves, video games, and kung fu movies, you’ll probably give The Matrix five stars. But if you begin to lose interest — as I do — after five minutes of effects-enhanced martial arts action, or if you think Keanu Reeves has yet to learn diddly-squat about acting, you’ll probably find yourself engaged by standard-setting visual effects but unmoved by these unremarkably archetypal characters .

Don’t get me wrong: The Matrix is a wild ride — and worth the ticket price to see the art of digital animation advance. There’s enough visionary work here to make 130 minutes feel more like 60.

And the premise has potential:

In the future, human beings are little more than batteries that power machines, machines that have conquered the world. "Living" in suspended animation, people are entertained by a false reality transmitted into their brain by the "Matrix" so they will relax and keep pumping out the power. But the machines have a problem: A few have escaped this illusion-world and are forming a rebellion against the Matrix.

And those few, led by technology guru and philosopher Morpheus (Laurence Fishburne), are expecting — yea, actively seeking — their prophesied messiah.

Now, I've got nothing against mythological archetypes. I love it when a formula is fulfilled with imagination and innovation. My deepening love for cinema does not threaten to spoil my enjoyment of action or sci-fi. But I'm increasingly impatient with movies that aim no higher than to entertain eyeballs. It seems like a rare event that a filmmaker delivers a genre movie that rewards attention, reflection, and discussion. Action thrillers like Die Hard and Face/Off, ponderous serialized space-fantasy like Star Wars, and dark sci-fi parables like Blade Runner and Existenz are among my favorite films, rewarding revisitation regularly.

Where does The Matrix rank in this, uh, matrix of genre movies? Between bursts of slick, stylish action, it raises some interesting questions about where society is headed. (Are becoming mere generators, consumers dutifully sustaining their conquerors—the corporations?) But it provides only action-figure mannequins to play out the story, and it digs no deeper than Stoner Philosophy 101. It can't decide whether it's a tongue-in-cheek action adventure or a soul-searching sci-fi epic. And it does not strike a satisfying balance.

[2019 Update: Okay, Overstreet Archives — hold on. Whether or not you're right, you're going to be surprised at how this movie remains not only popular but also provocative. It will become a cult classic. It will become the cornerstone of Keanu Reeves' career. It will inspire two sequels, all kinds of imitators, fan fiction, and an anthology of animated shorts. Pastors will draw sermon illustrations from it for decades to come, until you're tired of hearing them. And your good friend Bart Cusveller will co-author a book of theological reflections called The Matrix Reformed. So... go on, but you're about to learn that others found plenty to talk about in this film.]

A couple of years ago I might have enjoyed this slightly philosophical adventure more, but it arrives in the wake of sci-fi endeavors that explored some of the same ideas with greater courage and more reward.

Last year, we saw two films—Dark City and The Truman Show—that were about fabricated worlds in which a hero tries to make sense of all that is artificial and learns how to overcome it. There are allegorical implications in each. But both of those films outshine The Matrix in almost every way. Dark City director Alex Proyas and The Truman Show's Peter Weir actually let their actors do some acting. Proyas also knew how to tell a complicated story and address serious philosophical questions without giving up his relentless (and astonishing) pace.

In The Matrix, I found myself yawning through the kung-fu, wondering when we were going to be allowed to contemplate this fascinating premise and its philosophical implications.

Sure, it has breathtaking action and stunning animation, but Face/Off and Die Hard demonstrate that fast, frantic action movies can also develop memorable characters. Watch Face/Off again—notice how a few short scenes of intimate drama, performed by actors who are acting (John Travolta, Nicolas Cage, Joan Allen), make these two character into memorable, witty, intelligent, driven characters, so that we actually feel something for them in the end. All that The Matrix does to make us care is to beat them up a lot; after all, audiences will care about any hero if he just suffers enough.

If The Matrix had replaced a few tedious minutes of men using each other as punching bags with a few revealing minutes of character development, or reached for the tongue-in-cheek kung-fu attitude of Big Trouble in Little China (which also has memorable characters and lines I remember more than a decade later), it might have become something truly special.

I knew that I had paid to see an action movie, but The Matrix kept raising questions that made me want it to be so much more. For example, if these revolutionaries have been waiting for years for "the One" who would be their savior, I want to know what is special about the One—why he's so unique, what he can do that's superior to any of the rest of them. Surely he can boast of better things than merely fighting harder and faster than them. Surely!

(Sigh.) I guess not.

All of that religious anticipation and all we get is a savior whose epiphany leads him to a disappointing answer: "Guns. We need lots of guns."

Keanu Reeves, who became famous by feigning (?) dull-wittedness in the Bill and Ted movies and then aspired to more serious acting (My Own Private Idaho, Much Ado About Nothing, Devil’s Advocate) seems to have surrendered to his fate — he’s an action figure. As Thomas Anderson—or "Neo", the long-awaited Messiah of cyberspace—he just looks angst-ridden, incapable of inspiring anyone to welcome him into Jerusalem with palm branches.

If anybody has a chance to act in this film, it's the great Laurence Fishburne. Fishburne has demonstrated his ability before in films like Searching for Bobby Fischer and Deep Cover Unfortunately, he blows his opportunity here for a defining role. Morpheus, a mysterious renegade Yoda who endures to train the Savior and see the world freed of the curse of the machines, could have been a fascinating stranger. Instead, he’s expressionless (unless a toothy half-grin makes one expressive), and he makes every line sound like a pronouncement of historic gravity spoken from a pulpit.

[2019: Okay, I'm going to interrupt again: Really? Fishburne's the only actor who impressed you? Did you not enjoy Hugo Weaving's hammy, sneering, hilarious turn as Agent Smith? You're going to learn to love him. You'll also seek out films like Proof, in which he's outstanding, and you'll even begrudgingly accept him as Elrond in The Lord of the Rings in just a few years (even though he's not as good as Bowie would have been). You'll come to admit that he is, throughout this trilogy, a juicy highlight.]

Worse, Morpheus's declarations of the "truth" to Neo are so condescendingly pretentious that if I were Neo I'd have laughed at him. These "teachings" are meant to inspire respect and awe, but they’re so lacking in substance that they just become annoying.

"You want to know what the Matrix is, don’t you?…You’re not ready yet." (insert action scene) "You will know…Soon." (insert action scene) "Are you ready?" "The answers are out there, waiting to be found…The truth is hard to swallow." "No one can tell you what the Matrix is." (insert action scene) "You have to experience it…For yourself." "Are you ready?" (insert action scene) "Soon." (insert chase scene) "Guess what? I don’t actually have the answers." (ANOTHER kung fu scene) "You want answers, don’t you?" (insert big shootout) "You’re probably wondering…" "Hard to believe, isn’t it?"

For an interesting comparison, see Mystery Men, which is also in theaters this year: There's a movie that sees the comic potential in a figure like Morpheus—in that case, he's The Sphinx.

After Yoda taught Luke Skywalker, there was still a lot of movie left for Skywalker to put his education to work. But there’s no story left by the time Keanu is finished. There's only room for a big gunfight.

Since Keanu and the cast fail to captivate me, I have a lot of time to think about other movies while The Matrix unfolds — movies this one stole from, movies it cannot match. What if I had cared about the hero? What if the classically-trained actor Rufus Sewell (Dark City, of course) was the potential savior of the world instead of Surfer-Dude Reeves? What if the teacher-pupil interaction between Fishburne and Reeves had been interesting in their conversations as well as their sparring, like the swordfight training scenes of Anthony Hopkins and Antonio Banderas in The Mask of Zorro?

And just as the credits are about to roll, The Matrix makes the same blunder that blunts the ending of 1999's grander sci-fi spectacle, The Fifth Element. As the buzzer is about to sound, the movie decides to announce that True Love—out of the blue—is the solution to all ills. Remember how, after two hours of blowing things up, "true love" just seemed a jarring and unearned conclusion to The Fifth Element? Same thing here. True love develops so suddenly between two characters in The Matrix that it scared the daylights out of me. I'd watched the development of an anti-gravity kung-fu partnership, and I might have detected a faint pulse of hormones in these mannequins — but love? When does anybody in this movie have time to fall in love?

The guy that sat next to me shook his head and said, "You know, now that they finally explained the Matrix world, they’ve set up a context for a cool story!" I think he's right. Maybe the sequels will fulfill the promise that the first hour of The Matrix gave us. Maybe there is more to Neo than meets the eye in this film. Maybe he's got more than fast hands.

So go see The Matrix, buy some popcorn, and check your brain at the door. Enjoy the fights. Enjoy the effects. Just spare yourself the unpleasantness of searching for meaning in its madness.

Two Responses to My Original Review of The Matrix (1999)

Melody Fields is a student of Medieval history, literature, and philosophy.

Peter Chattaway is a film critic for various Christian publications such as Christianity Today, B.C. Christian News and Christian Week.

Melody Fields:

While I agreed with several points Jeffrey Overstreet made about The Matrix, i.e. the lack of characterization, the several missed opportunities to delve, and the love interest, I have to disagree fundamentally with his perspective.

Firstly, I don't think Neo is a Christ figure. Morpheus explains that there was a man, who trained him, and the oracle predicted his return: a rebirth, not a birth, and thus a Buddha, not a messiah. Therefore, all Jeffrey's complaints about how Morpheus trains Neo has to do with a misinterpretation of theme: this movie is an amalgam of Western concepts of the reproduction of power and Eastern methods of escaping it. Think Zen, and all those "are you ready," "when you're ready" comments make sense. It's not that you have to bend the spoon; that's impossible. You just have to recognize that the spoon doesn't exist. And so in an Althusserian (Marxist critic of power structures) world where every individual has been interpolated into a false consciousness—where every individual, no matter how enslaved can be your enemy because he or she is so attached to the dream that they'll die to protect it—the only way to combat such ingrained belief is not to believe at all. Enter postmodernism.

That is why I have to disagree. I believe the movie allows you to investigate serious issues. But it requires a paradigm shift to recognize that disbelief is a powerful philosophical tool.

As for the movie's emphasis on "guns, lots of guns": the question is... Can you tear down the master's house with the master's tools? My take on this is: a little bit.

The shoot out was remarkably well done, but what saves the day is not more guns, but rethinking, or more correctly, not thinking clearly. Which is why Keanu Reeves is the perfect man for the job. He's so "not there", and not being there is exactly what's needed. The kid in the Buddhist get-up is too serious for the job; he's thinking East, but can't live West. Keanu attempts to blend East-West into, well, into disbelief; so the Kung-fu is only effective to a point. In America, you need a gun to win the day, or at least start the day off right. The final scenes of the movie literalize America's motto: "Make my day." The ultimate promise is not for a post-trib millennium, but to destroy the false-consciousness which enslaves humanity. It's postcolonial, oppositional theory based in an Althussarian world-view plus Zen postmodernism. And that's why it's not supposed to feel finished, or polished, or profound.

The kiss, by the way, is a spoof. You're supposed to groan. Didn't we all groan when they ran off into the sunset? The effective part though is that the backdrop for this kiss is not the beautiful west, but the ugly reality. It turns out that Plato's Cave of Western Philosophy is just a dream, and once you get outside, the reality is pretty darn ugly. Question is, would you go back in for the steak? If you're looking for a moral to the story, it's this: America is a fantasy, and people are enslaved in not-so-pleasant circumstances to serve as the labor (battery) to keep our dream alive. We think we're more free than Indonesians, but it's all just a corporate nightmare, and once you realize that, will you abandon the fantasy, or ask for another steak?

So that's why I think Mr. Overstreet is wrong about The Matrix. It's what postmodernism is all about; you need an entirely new critical apparatus to enjoy the entertainment. Drop the Christian motif and the Western attachment to belief (when Neo is "starting to believe" he's only starting to believe in disbelief), and I think you'll find a spectacular vision of postmodern oppositional consciousness.

P.S. You should note that I'm not a proponent of The Matrix's premises, but I like to see any philosophy (or anti-philosophy) well portrayed.

Peter Chattaway:

I'm currently embroiled in a debate with a guy who made the same basic point as Ms. Fields: Neo is a Buddha figure, not a Christ figure (for a Christ figure, he recommended Rufus Sewell's Dark City character). I'm not so sure. In my original review, written after I'd seen the film only once, I did my usual thing and harped on the film's Gnostic escapism; but after seeing it a second time, the Christ-figure elements stood out a little more. (The second time around, I was also less fazed by the film's length than I was the first time around. Maybe I just saw it with a better audience, I dunno. Check out the second review at B.C. Christian News.)

In essence, what I think we have here is a Christ figure in form, but a Buddha figure in essence. I think.

The Christ-figure elements are too numerous to mention—the John the Baptist stuff (and don't tell me that "training" scenes are foreign to Jesus; he was a follower of John's before he branched out on his own, y'know), the "baptism" in the mirror, the fact that his coming was prophesied, the fact that the human refuge is called Zion, Neo's death and resurrection (in a glorified body, you might say), and so on. But the overarching paradigm is essentially Gnostic and, insofar as Gnosticism is antithetical to Christianity, non-Christian. It posits that the world we live in is not really there, that we are free souls trapped by some jealous, soulless mechanism (the demiurge in Gnostic mythology, the machines in The Matrix, the aliens in Dark City, the TV producers who can't live the "blessed" life on their own in The Truman Show, whatever), and that the best thing we could possibly do is rebel, recklessly if need be, to assert ourselves against all odds. (Philip K. Dick, author of the books that became the films Blade Runner and Total Recall, was particularly emphatic on the need for spontaneity, and he is listed in the notes to The Nag Hammadi Library—the official scholarly collection of Gnostic texts -- as a prime specimen of modern Gnosticism.)

So the Gnostic Christ is the Christ who encourages us to follow our impulses (just as Mouse encourages Neo to do; but what if our impulses lead us to kill our fellow humans, as Neo's do, or even our comrades, as Cypher's do?); he is the Christ who encourages us to trash this world, or at least ignore it, because it's only a distraction anyway. Contrast that with the, for lack of a better word, orthodox Christ, who embraces creation and extols the value of the material world (not least by becoming material, a part of creation, himself), who knows that our very souls need some sort of cleansing that no amount of impulse-following can give us.

Is Neo a Christ figure? Yes, but I can understand why people might think otherwise. It is commonly thought that Christ knew what he was doing from the day he was born, if not sooner. (Did every kick in the womb follow a divine purpose?) This is why movies about Jesus are usually very, very boring. Jesus, as a character, has nowhere to go; he sometimes gets all but reduced to a supporting player in his own life story as the film in question follows the other characters, i.e. the ones who followed Jesus or plotted against him (the 1961 King of Kings is a big culprit here).

But a character who learns his mission in life, who acquires a sense of his own divinity? Well, sure, that sounds more like Buddha, alright.

But the principal idea behind Buddhism and other Eastern religions, as I understand it, is that all people can tap into this inner divinity if they try hard enough; the principal idea behind Christianity is that Jesus had a unique relationship with the divine. The degree to which Jesus may or may not have had to learn his vocation is simply unknown.

So perhaps the question we ought to be asking here is whether or not Neo is unique. Yes, there was that other guy who trained Neo's predecessors, and Neo is, in some sense, a rebirth of that character, but I don't recall the film making an explicit plug for reincarnation, any more than the gospels argue that John the Baptist was a reincarnation of Elijah. John and Elijah had a lot in common, yes, and John was seen to be a fulfillment of the prophecy that Elijah would return; Neo and his predecessor have a lot in common, and Neo is seen to be a fulfillment of the prophecy that his predecessor would return; the parallels to Christian thought don't stretch credulity all that much, and there is no need to assume reincarnation there.

So ... is Neo unique? Does the film put him on a pedestal, or does it suppose that that which Neo has learned is somehow learnable by everyone? On this point, the film is, I think, unclear. One could argue that, in the end, Neo has become just another rebel like Morpheus or Trinity—somebody who can leap tall buildings in a single bound, yada yada. But I suspect that there is more to it than that; Neo, in his moment of glorified resurrection, does something which no other character seems to be able to do, namely, he kills Agent Smith. He doesn't just fight the guy off until he can get an exit, the way that Trinity does at the beginning; nor does he take a good beating, the way that Morpheus does in the third act; he actually sees through the Matrix, sees it for what it is, and enters Agent Smith in order to destroy him from within. He vanquishes the foe in a way that no other character is apparently able to do. And so I tilt towards believing that Neo is, to some extent, unique... and thus a Christ figure, not a Buddha figure.

But, as I say, he is a Christ figure in form. In essence, the values or worldview or basic approach to life espoused by the film through Neo, is more eastern than western, and thus, perhaps, reflects the Buddha more than the Christ.

The Matrix Reloaded (2003)

[This is an abridged, edited version of the review that was published during the film's first theatrical release.]

Even at the movies, you can have too much of a good thing.

The Matrix Reloaded takes every aspect of 1999's The Matrix and turns it up to '11.' There are more awe-inspiring visuals; more stylish and thrillingly supernatural kung fu that will fry the circuits of the Cool Meter; and more brain-bending ideas about reality, illusion, freewill and determinism.

Unfortunately, these excesses end up making Reloaded more like Overloaded.

The philosophical riddling becomes too convoluted. The awe-inspiring fight scenes run too long, delivering few surprises and zero suspense. And the kung-fu/wire-fu confrontations become tedious. This may seem hard to imagine for fans of the original film. But even the biggest fan of chocolate mousse cake can only eat so many pieces before he gets sick.

A quick review may be necessary before you go back to Matrix-land. Neo, a mild-mannered computer hacker, has been pulled out of his dull existence by spooky and violent strangers informing him that he may be “The One.” He learns, the hard way, that his whole world is an illusion, “the Matrix,” and that he has been duped into a false existence while his body and the bodies of almost all human beings on earth are actually in prison, being drained as batteries for a world run by wicked machines. Neo goes “unplugged,” joining the enlightened resistance, the remnant of humanity hidden deep underground in a place called Zion. But before he gets there, he must go into the Matrix and battle the malevolent and manufactured “Agent Smith,” a trial that reveals his awesome abilities and confirms that he may indeed be the Prophesied One.

I was not a big fan of The Matrix. It had intriguing ideas that got me thinking about philosophy and religion. It also had some fantastic action that provoked a hundred action-directors to imitate it. We learned that science-fiction films can still integrate spiritual questions with techno-babble and captivate our imaginations with movie magic. The Wachowski Brothers stole the special effects Oscar right out from under George Lucas’s much-hyped return to the Star Wars universe in 1999.

But as you have probably learned from going on dates, looks aren’t everything. The characters were flat and lacked back-stories. The movie’s “true love saves the day” conclusion was unconvincing, even preposterous. (Who had time to fall in love?) Its buildup to the arrival of a Messiah took a nasty turn when that Messiah’s moment of revelation found him asking for “Guns. Lots of guns.” And its philosophical ideas, while interesting, were delivered in sanctimonious and annoying speeches. Style stifled storytelling and substance…

…and the same occurs here, but more of it. As The Matrix Reloaded gives us too much of what we liked in The Matrix, we get tired and become more and more aware of its weaknesses.

First, the strengths. Trust me, Reloaded is an unforgettable marathon of visuals that will knock your jaw right off its hinges and kick it under the seat in front of you. This movie is to special-effects films what Mercedes Benz is to automobiles— slick, shiver-inducing, and smooth, running like a zillion well-oiled machines. Anyone who played a part in what we see in this film deserves our heartiest congratulations. It will make a great DVD—you can play your favorite parts over and over and skip the glue, the flimsy storytelling, and the flat dialogue.

The kung-fu (choreographed by Yuen Wo-Ping ) seems to exhaust the possibilities of the art, although I’m sure the third film Revolutions will prove that they haven’t.

[2019: As many kung-fu films have shown since The Matrix Reloaded, I clearly underestimated just how much more imagination could be demonstrated in the genre.]

And the stunts are breathtaking… although not as breathtaking as they would have been if they hadn’t been heavily enhanced by digital animation. You just keep realizing that when you're inside the Matrix, the stuff onscreen really is an illusion. Oh, how I miss the days of real stuntmen. How I miss the special effects of glue, puppetry, and other handmade effects that made you ask “How did they do that?” (That’s why the new Star Wars movies, visually impressive as they are, lack the magic of the originals. Everybody knows how they did that.)

Speaking of George Lucas, the Wachowskis are following his example in more than just special effects… and that’s a bad thing. (In case you’re wondering, yes, we have now shifted gears to talk about its weaknesses.)

Why did they have to imitate his lack of attention to actors? The stars here act as if they have no time for emotion. They proceed with grim determination, from one action sequence to the next. They do not capture our concern or care the way the persecuted and desperate rebels did in The Empire Strikes Back, the standard by which all sequels are measured. (That was back when Lucas still let real directors direct his stories.)

Our heroes’ familiar faces remain, unfortunately, familiarly blank, coming to life only when violence breaks out. As Morpheus, Laurence Fishburne muses, preaches, and mopes—but dude, he owns that saber! As Trinity, Carrie-Anne Moss is the franchise’s weapon of mass destruction. I repeat what I wrote in my original Matrix review… I’d rather the whole series was about her. She’s all-business, determined to develop a memorable character in spite of a confining script, an even tighter latex suit, and a contract clause that forbids her to bless us with a big smile. It’s Hugo Weaving who gets to smile, clearly aware he won the battle of personality in the first film. Too bad his big scene is also the film’s most unnecessary.

And of course, there’s Thomas "Neo" Anderson (Keanu Reeves), the dumbfounded Savior, “The One.” Reeves soldiers on with that same stunned look that we all had when we realized that the world’s fate rested on this guy’s shoulders. In the first movie, Neo’s signature line was “Whoa.” But in this movie, as he seems to forget his newfound supernatural powers at key moments, the unspoken refrain becomes … “Duh.”

"Duh."

So, devoid of compelling or complex characters, the story has very little… well… story. The film’s preoccupation with stylish effects-driven confrontations make Matrix more and more SEGA than saga.

Compared to the multi-thread plotting of X2, this storyline seems pulled out of X-Box. Here’s the gist of Reloaded:

The heroes are trying to short-circuit the war before the Sentinels, squid-like drilling machines that fulfill the role of Empire’s Imperial walkers, reach Zion and crush the rebellion. So Neo, Morpheus, and Trinity plug themselves into the Matrix and set out on a wild goose chase. Find the Oracle (the late Gloria Foster). What does the Oracle say? Find the Merovingian (Lambert Wilson). Once you find the Merovingian, find out where he keeps the Keymaster (Randall Duk Kim.) Find the Keymaster. Once you find the Keymaster, use the Keymaster to find the Architect (Helmut Bakaitis, who looks like the father of Colonel Sanders, Sigmund Freud, and Robert Altman).

Of course, each one of these contacts will be preceded by a spectacular kung fu match with either the Seraph (Collin Chou), dozens of copies of Agent Smith 2.0, or the Twins (Neil and Adrian Rayment, who look like The Thompson Twins reinventing themselves as an albino version of Milli Vanilli.) Or you might face the temptation of a seductress called Persephone (Monica Bellucci).

Where is all this headed? What happens if you win? This happens: You get another big lecture from the most sanctimonious character of them all.

After only an hour of this game, I was bored with watching the Wachowskis work their joysticks. I just wanted something new, something that would make me care about the plight of Zion. Unfortunately, the mystery of Zion is spoiled right away. This place that was mentioned with hushed reverence in the first film is not quite what we’d hoped.

Zion is a maze of underground caverns where all of the survivors have gathered to model the expensive leather fashions they purchased. Where did they get them? When the surface was conquered by machines, did survivors go on a looting spree in the bombed-out malls before they fled into hiding? We get to know some of them, like Link (Harold Perrineau), the bland sidekick. And we quickly learn that being a supporting character for the Wachowski Brothers is no different than being a supporting character for Warner Brothers Television in one of those lousy courting-cancellation sci-fi series like Andromeda.

And what do the Zionists do when they find out the machines are just a few days away from obliterating their existence? They get drunk and party like a bad Zima commercial, turning up the joyless tribal cacophony, engaging in chaotic scantily-clad Dirty Dancing till the dawn. As a much wittier critic at The National Post observed, “It removes an important element of dramatic tension from the plot: If the machines don't get these people, syphilis surely will.”

Please, I’d rather live in the Matrix than with these folks! At least in the world of illusion, frequently glimpsed religious symbols suggest that the prisoners are still engaged in spiritual growth, whereas this subterranean colony responds to persecution with hedonistic revelry.

I suspect that the moral of the saga is this: The only true way to live freely as a human being is to disobey, to rebel, against any high power, against any control. (When one of Neo's adoring followers says, "You saved me!", Neo insists, "You saved yourself.") If that is indeed the lesson, then this series cannot come to any satisfying conclusion.

As Bob Dylan insists, "You gotta serve somebody." Human beings are meant to follow a higher power. Their problem is that they keep following the wrong powers—primarily, their own misguided selves. Morpheus, Neo, and Trinity are right to strive against the tyranny of a cruel Architect. But if they conclude that they are alone in their struggle, that there is no benevolent higher power offering a better way, then their only option is slavery to yet another corrupt power: their hearts. Being human, having imperfect appetites, they will veer off any track toward fulfillment.

Morpheus can't have it both ways. He can't insist on rebellion against higher powers and yet place his hope in having been born for a "purpose," having been guided by "Providence." If we indeed have a "purpose" in this life, one worth discovering, one that means something, it must have been purposed by someone. If Providence does exist, then we had better learn some humility and, yes, obedience. All I see in Zion is willfulness, defiance, and pride.

Shots of this mass-Lambada are intercut with a lovemaking scene for Neo and Trinity that lacks any trace of chemistry. The kiss shared by Han Solo and Leia in The Empire Strikes Back, and the similar kiss between Wolverine and Jean Grey in X2, held more steamy romance and more personality than this dull, awkward interlude. Suddenly PG seems more real—and racier—than R.

Those who mock the Star Wars prequels for flat acting and cheesy dialogue will be dismayed to see that this virus has reached Zion. I would argue that things are worse here. Lucas’s lifeless character interaction at least enriched the storytelling with history, details, some humor, and some mystery. The Wachowskis’ character interaction comes in two flavors: preaching and pummeling. I feel like I'm switching between the Psychic Network and the WWF. You can feel the writers getting desperate for snappy, quotable one-liners at the end of each action sequence.

The Twins glance at each other during the endless freeway chase scene and say, “We are getting aggravated.” Amen.

The first film had moments of real horror (the bellybutton bug and the mouth-zipping), thrillingly chilling moments of revelation (the definition of deja-vu), and small character moments that made a few of the characters break out of their flatly scripted role. This film has only one scene in which the effects step aside and the particularity of line readings and character detail get us at the gut level.

When Neo and the gang finally catch up to a creepy Frenchman called the Merovingian, he turns out to be the film’s most interesting character. He treats them to the one truly unique scene, an exchange infused with personality, humor, and new ideas. It is also short and sweet. Like the memorable Matrix scene when Mr. Smith first interrogated Neo, the thrill of the unpredictable takes over, proving that personality clashes are far more suspenseful that fisticuffs. The film’s most troubling, twisted, and interesting moment--the only moment when the villains seem truly malevolent instead of just violent—comes from something as surprising as the restaurant dessert tray.

I’d like seconds of this kind of thing, please.

I’d like seconds of this kind of thing, please.

"Look at you, filthy American idiots, you dress-wearing kickboxing types, you go around underground with your sunglasses on and your messianic powers, and yet, with a few lines of dialogue here at this restaurant, without striking a single blow, I steal the movie right out from under you!"

All of the great middle movies have tried to outdo their predecessors: The Empire Strikes Back, The Wrath of Khan, Terminator 2, The Two Towers, and this year's spectacular X2: X-Men United. But what I find myself remembering fondly are the character moments, the ways relationships change, the humorous and human developments. The visceral, searing confrontation between Vader and Luke Skywalker; the tragic farewell between Spock and Kirk; the bonding moments between heroic Terminator and fatherless boy; Gollum's quiet conversation with himself; Magneto revealing the horrifying truth to Xavier in the plastic cell.

These sequels had characters with histories, personalities, complex relationships, and interesting things to say. They didn’t stand around and alternately pummel and preach at each other. Neo can fly like an arrow, but I’m never convinced there’s much of a mind behind those sunglasses (which he inexplicably wears even in the dark.) That’s not Keanu’s fault. It’s the fault of storytellers who haven’t found a head or a heart in their hero. If the storytellers don’t care enough about their characters to develop them, why should we care about them?

It is still possible to save this series. The Wachowskis have a lot of loose ends to tie up in Revolutions, but they have also given themselves great opportunities to deepen their characters. Morpheus's ego and his faith have been dealt a serious blow; how will he respond? Neo is more confused than ever; what will he do? The nature of Agent Smith has changed: What will happen to the way he hates humankind now that he can see them from a different angle?

If the Wachowskis can slow the pace of the adventure without shifting into pretentiousness and dense verbosity, they could concoct some compelling character moments. If they learn that audiences can be excited by more than bullet-time and “burly brawls,” and that action is more exciting when we care about those who are acting, they might prove that this foundation can support a grander structure than we have yet glimpsed. They might show that all of this sound and fury signifies something… that elusive “purpose” Morpheus keeps talking about. If they do, it will be a revolution indeed.

The Matrix Revolutions (2003)

[This is an abridged, edited version of the review published during the film's first theatrical release.]

The Matrix Revolutions fails to wrap up the myriad loose ends that the trilogy’s second part, Reloaded, left flapping in the apocalyptic wind of its relentless hot air. And yet it is an improvement on its predecessors.

The Matrix saga, as you know, is primarily about the enslavement of humanity to dehumanizing and exploitative machines. (Do they represent technology? Capitalism? Media culture? Sin? Who knows?) And yet, with the arrival of what is allegedly the final chapter, the central dilemma remains unresolved. The machines are neither victorious nor overthrown. We're left with many nagging questions about the issues raised early on: What is the Matrix? Who exactly is "The One" and where does his power come from? Is it possible to win the war? Is there a difference between human being and machine? Is there a true religion?

While there are many enthusiasts who will be surprised at this chapter's lack of resolution, what is most surprising is the movie's avoidance of the things that earned it so many nay-sayers, including myself. While The Matrix was decent entertainment—a curious hodge-podge of religious ideas and philosophical tangents with a few nifty special effects thrown in for good measure—it never developed engaging characters. Who wants an epic adventure about mannequins in sunglasses? Reloaded was far worse, a bloated affair of overlong, artificial kung-fu fights, tedious and pretentious speeches, and pancake-flat dialogue.

I walked into Revolutions fully anticipating another two hours of sci-fi sanctimony and CGI demonstrations. I was floored to discover that Revolutions is a compelling, astonishing war movie, and the most purposeful and intense of the trilogy.

Why? What changed? Certainly not the dialogue, which remains tepid and convoluted. And it’s not the profundity either—the Wachowskis have created such a mess of ideas that it just can’t be congealed into a meaningful whole. But on several fronts where the first two failed, this one succeeds.

First of all, this is a movie about human beings. The characters suddenly have strong emotions—even Neo (Keanu Reeves) gets mad, sheds tears, plays with guts. I even became convinced, after seeing no solid evidence in the first two films, that he and Trinity (Carrie-Anne Moss) had actually fallen in love. There is a tenderness and a depth in their exchanges that has been lacking until now. And the holier-than-thou, Shakespearean-soliloquy-spouting Morpheus (Lawrence Fishburne) is now a humbled, haunted, shell of a man, scrambling for what remnants of his faith he can salvage. Even the Oracle, a computer program, develops enough personality and passion to earn herself some kind of credit toward becoming human. (Mary Alice is a subtler, more interesting Oracle than the late Gloria Foster.)

Secondly, the film makes me care about the people who are resisting the machines. The people of the besieged underground city of Zion suddenly quit acting like lazy libertines and come to life, mounting one of the most inspiring and exhilarating last stands ever filmed. Revolutions is, above all, a war movie. The battle to save Zion, which seems to fill half of the movie’s running time, is brutal, bloody, and convincing; it avoids the video-game look that dominated the action sequences of Reloaded. Here, computer animation and real footage are combined with galvanizing power. The apocalyptic imagery of that battle is worth looking at frame-by-frame for its masterful choreography of combatants. The squid-like battle-bots called Sentinels stream like long ribbons of wrecking balls, huge flocks of clamoring starlings, or a squadron of death angels, as they force their way into the massive caverns where the Zion dwellers have been hiding.

There were more moments of awe and dread in this conflict than in any of the Star Wars or Lord of the Rings battles I’ve seen onscreen. To make me care that much about these people this late in the game required some genius, and Revolutions delivers it.

Sure, the series cannot escape the problems that have become a permanent part of its style. The talk is still pedantic and heavy-handed. The characters lack back-story and history, and thus the changes they undergo are not terribly dramatic. Worse, the filmmaker Brothers squander their best ideas. Scenes inside this “wonderland” of the Matrix are limited to a clever sequence in a train station and an indulgent, ridiculous S&M club where the Merovingian savors his own personal hell.

While it is clearly the darkest, this is also the funniest of the three films. A confrontation with the Merovingian involves an amusing handgun standoff, and he gets some more wonderfully slimy lines off. “It is remarkable how similar the pattern of love is to the pattern of insanity,” he mutters. Unfortunately, Persephone (Monica Belucci) has nothing to offer this episode but cleavage.

But the Merovingian isn’t the only enjoyable supporting player this time. Bruce Spence (who will pop up again in The Return of the King as The Mouth of Sauron) is a powerfully grisly latecomer to the cast, playing an enormous half-scarecrow, half-Rob-Zombie villain called The Train Man, but unfortunately he only has time to be introduced and then his part is done. Also, a charming trio of “programs” give us the first glimpse of a likable family unit that the series has offered.

My favorite scene is the long overdue confrontation between the Oracle and a dozen Mr. Smiths. It’s the funniest and juiciest exchange in the series.

Mr. Smith. Wow. Hugo Weaving has been the best thing in the series since it began, the only actor to bring personality to his character in all three films. I love this guy. Here, he outdoes himself, making the most of every slimy line, going over the top at last. Finally, we have a character to match the intensity of the film’s CGI. Every time Smith opens his mouth in this film, I’m grinning. If I were the Academy, I’d recognize the work he put into this role, the way he made something memorable out of every moment he was onscreen—give the man a nomination.

Add to that the fact that they found an actor capable of an uncanny Mr. Smith impression—Ian Bliss who plays Bane, the Zion citizen lying unconscious and “infected” by Smith at the end of Reloaded. I kept waiting to catch him lip-syncing to Weaving’s voice, but no… it’s just a dead-on impression.

The other cast members deserve kudos as well. Carrie-Anne Moss seems deeper, more sincere, more breakable. So does Keanu Reeves, who finally finds some real emotion and some humanity in Neo. Jada Pinkett-Smith is finally given something to do as she develops a likable snarl and actually musters some Han Solo charisma in her “go for it” piloting style. I love how she ends up bossing Morpheus around as if he’s a sullen Chewbacca.

The visual wonders of Revolutions surpass those of the Star Wars prequels and parallel the achievements of WETA Workshop in The Lord of the Rings saga. This episode escapes the dull, dispiriting blues of the first film and the sickly greens of the second. It boasts a full palette: colorful explosions, sunlight, and a fiery approximation of Neo’s new powers of sight jazz up the otherwise inky and rain-wet textures.

Revolutions is a masterpiece of sound design as well. The special effects are dizzying, and the movie abandons the heavy metal soundtrack of its predecessors, taking an Orff-esque choral chant as its epic motif. This deepens our sense that this is about something more important than ego and microchips.

Many of my colleagues are condemning the film for its lack of a resonant resolution. Indeed, we still lack satisfactory answers to many important questions posed by the films about the nature of reality, religion, faith, and love. Thus, it falls far short of the Star Wars trilogies and Tolkien’s epic in the sense of metaphor and meaning.

And yet, I was encouraged in a way by this failure. I was worried that the Wachowskis would try to foist some false religion on us, or preach some cheap New Age slogan. Instead they seem to suddenly come to their senses and realize that they have no answers. Thus, all that remains is an array of ideological relics, like traces from several archaeological digs scattered across the same floor.

Emerging most intact from the rubble are remnants of Christianity. As they tried to subvert Christian faith by suggesting that God is just a human invention of convenience, they cut themselves off from any source of redemption outside of “the human spirit.” And the human spirit is not enough, because human beings are by nature flawed, self-interested, and diminutive in the grand scheme of Creation.

Failing to come up with any tangible replacement for God, or for Christ, the Wachowski brothers resolve their film by quietly surrendering their journey, falling back on the answer so true that it has consistently popped up in the subtext of mythology since time began. The Matrix trilogy is, in the end, a Christ story, albeit an incomplete version. In fact, the cross makes a clearer appearance in Revolutions than anywhere in Jackson’s Middle-Earth films.

Too bad their exploration allows for no resurrection. This movie’s hero takes a road to the cross so people can be free in this life. But it is unfortunately implied that the film’s slogan means what it says: “Everything that has a beginning has an end.”

However, the Oracle does mention something about Neo having the power to tap into “The Source.” It makes me wonder if this may prove to be a crack in the theory of finality—if the Source might be able to redeem this world in a way neither man nor machine seems able to accomplish.

I honestly hope we haven’t left The Matrix behind. It’s finally beginning to get interesting. I only hope somebody (who can tell a story) will turn loose all of its potentially profound and compelling visions. For now, we’ll have to be content with this, a closing chapter that performs better than anticipated, but still fails to take us far enough. The storytellers have yet to offer much insight on the subject of good, evil, and the Divine, but hey, at least they finally discovered human beings.

They Shall Not Grow Old (2019)

Peter Jackson has saved his best Middle-Earth movie for last.

I know — it sounds like I'm baiting a hook just to get you to read about a documentary. But no, I'm serious: If you want to understand The Lord of the Rings, you should probably understand the furnace into which Tolkien was thrown, from which he somehow emerged alive, and by which a fire was lit within his mind and heart — an ache that could only be expressed in languages he invented, in vocabularies beyond the limitations of realism or allegory.

It would be inappropriate to treat The Battle of the Somme, the bloodiest and deadliest day in the history of British military engagement, as a footnote in the life of the guy who gave us Hobbits. Tolkien's service there is not why the subject interests me. But I am interested in how a story that goes on inspiring readers with beauty and hope was born from such a hellish occasion. And so it's remarkable that Peter Jackson, whose big-screen adaptations of Tolkien's beloved fantasy trilogy were so celebrated (and whose three film adaptations of The Hobbit were maligned, and rightly so) would be the driving force behind They Shall Not Grow Old, an extraordinary tapestry of World War One testimonies by the surviving soldiers who were sent into that madness against the Germans.

Honoring these intimate archival recordings, Jackson reveals harrowing accounts of the misleading propaganda that summoned so many young men, the dehumanizing pressures of the war, the particular chaos and slaughter of the Somme, the burdens that the survivors would have to carry, and the betrayals, abandonment, and loneliness that awaited those few who returned. And as we listen, he fills the screen with highlights (that word sounds trite and inappropriate here) from more than 600 hours of material from the Imperial War Museum and BBC archives. Much of it is sharpened and focused, but then, as in Wings of Desire and The Wizard of Oz, its black-and-white footage suddenly blooms into color and detail that takes your breath away.

The footage casts no doubt on the grim and grisly testimonies. I know that much of this imagery has been easily accessible for many years, but it is another thing to see it on a grand scale, so carefully restored, so wisely organized and edited. I won't soon forget the stories or the images: Bodies bent at unnatural angles. The mud that swallowed soldiers whole. A parade of men in blindfold-bandages suffering from mustard-gas blindness. Vast fields of dead rats. As we look back at gazes both solemn and snarky, frightened and fierce, we're often aware that a soldier's expression was one of the last pleas or semblances of strength he ever expressed.

Then comes the Somme, a battle so fierce we should be grateful that Jackson shifts here from photography to illustrations from war-propaganda magazines. These violent comic-book images may not qualify as realism, but they are very likely a kindness in comparison to what on-site images would have revealed. (There aren't any, apparently — a mercy.)

It's enough to drain all romance from the recent blockbuster imagery of Wonder Woman leading men on a charge into No Man's Land, as if those soldiers lacked the courage until she arrived. (Seriously—why celebrate someone seemingly immune to the forces against which so many men marched and by which they were slaughtered?)

And yes, though Jackson doesn't acknowledge it in the film, one of those young men who somehow survived was Tolkien. There with the British Expeditionary Force — a second lieutenant, only 24 years old — he endured the deadliest day in British military history. “Junior officers were being killed off, a dozen a minute,” he said. He began writing by candlelight "in bell-tents" and sometimes "down in dugouts under shell fire.” (For more on this, read Joseph Loconte's examination of these correlations in his 2016 New York Times editorial.)

It's easy to spot, in the sobering Somme imagery, the inspiration for the Dead Marshes, one of the scariest stretches in The Lord of the Rings. I half-expected to see Gollum lurking in shadows, or Samwise stumbling into the muck and crying out about "dead things ... dead faces in the water!"

Simon Tolkien, one of the novelist's grandsons, has observed (for the BBC) similar correlations:

Evil in Middle Earth is above all industrialised. Sauron’s orcs are brutalised workers; Saruman has ‘a mind of metal and wheels’; and the desolate moonscapes of Mordor and Isengard are eerily reminiscent of the no man’s land of 1916.

The companionship between Frodo and Sam in the latter stages of their quest echoes the deep bonds between the British soldiers forged in the face of overwhelming adversity. They all share the quality of courage which is valued above all other virtues in The Lord of the Rings. And then, when the war is over, Frodo shares the fate of so many veterans who remain scarred by invisible wounds when they return home, pale shadows of the people that they once were.

In They Shall Not Grow Old's making-of presentation (a 30-minute exhibition that has been offered post-credits during the theatrical run, and that will undoubtedly appear in an expanded exhibition on home video releases), Jackson goes into great detail to describe the challenges that colorization artists and restoration technicians faced in fulfilling his vision, as well as the vast resources they needed in order to approximate the appearance and sounds of the battle.

I agree with film critic Michael Sicinski that these endeavors to approximate the original colors and details aren't entirely convincing. In notes at Letterboxd, he remarks, "We never forget we are watching something additive, not organic." But still, I cannot underestimate how impressive the results are. They look more like the imagery of dreams than footage of a battle currently in progress.

However, that's not the most important part of this experience. In this, I agree with Sicinski again: The real treasure here is "an unusually brilliant collage of pre- and mid-war footage together with the first-person recollections of dozens of British vets, their voices weaving in and out of each other like a nation's chorus." This is not a case of "Go big or go home." The home video experience will be similarly impressive because the most influential, inspiring, and sobering aspect of the film is its relentless reel of audio testimony from the soldiers themselves.

They tell their own stories, recounting the propaganda and recruiting techniques that persuaded them to leave home, to give up their belongings, to head out into the trenches, and then to learn that nothing could have prepared them for the forces that would overwhelm them.

I hear a strange and unsettling compliance in the voices of these old men as they talk about being young men eager to get involved. It isn't so strange that boys would want to serve their country. But the lack of questions or hesitations when it comes to what they might be asked to do, what ethical questions might come into play — that I find difficult to understand.

Their memories are so harrowing that it's hard to believe that they emerged with enough sense to be able to put them into words. Expressions that have become clichés are nothing of the sort in this context—when one, speaking of the brotherhood between soldiers, says, "You fought for the man next to you," you can understand why, and you believe him. More than once we hear soldiers testify of someone next to them being here one minute, in pieces the next. Their stories of how they survived in the trenches defy belief. The fact that some were only fifteen or sixteen is appalling. The sense that engaging in such combat was a rite of passage in "becoming a man" is all the evidence we might need that something is wrong in our manufactured definitions of 'manhood.'

Critic Steve Sheehan at The Digital Fix argues that the movie is too relentless, too crowded. "These men’s stories need to be heard but they also deserve to be given space to breathe. For the audience to digest and process the enormity of what they are seeing, the words and pictures need more time to settle." Perhaps. I tend to think that the relentlessness of the testimonies represents, to some extent, the experience of being there: They did not have time to breathe as the madness unfolded around them and demanded everything of them, so why should such testimonies be padded for our comfort?

Victor Morton who, similarly impressed by the long record of testimonies (voices that are not identified until the closing credits), notes at Letterboxd that "the film feels like one man, your great-grandfather telling My Story, as the voices become a chorus singing as one."