The Queen (2006)

Stephen Frears' new film The Queen begins just before that catastrophic car crash, seemingly provoked by pursuing paparazzi, took the lives of Diana, Princess of Wales, and her boyfriend, the rich playboy Dodi Fayed. With an efficient and effective montage of news clips, Frears reminds us (as if we could forget) just how popular Diana had become, and why.

Unlike Queen Elizabeth, who stuck to the typical rituals of her tradition, Diana was an adventurous do-gooder. She was as big as Paris Hilton, and much more charitable and generous. She fought for AIDS awareness. She spoke up when her people wanted to hear from her. The world was charmed by the way her wedding to Prince Charles resembled a fairy tale. And people were overjoyed to see a "commoner" like themselves, a schoolteacher, a local beauty, enter into such glory with pomp and extravagance. The formality of it all was thrilling.

But eventually, she became symbolic of something else. When the extramarital affair of her husband Charles became public, and all of that symbolic expression was proven empty and corrupt, Charles showed no signs of repentance or remorse. And thus Diana came to represent another aspect of being "ordinary" in Britain — the establishment had made a show of their honor and devotion to her, and then betrayed her.

And so she set out looking for love, as her marriage was “a bit crowded.” With her went the hearts of masses of Brits, looking for some other symbolic fulfillment in globe-hopping affairs. Diana became vigorously "modern."

She became, as Tony Blair named her in a speech, "the People's Princess." And by implication, the rest of the royals were no longer of the people, but of a bygone era.

When she died after a car crash in Paris in 1997, people from around the world who had been enthralled by Diana's dramatic story went into a state of shock. Then came the outpouring of grief in expressions of music, poetry, and, yes... flowers.

So many flowers were brought to the gates of Kensington Palace that they looked like a flood of grief pouring up the avenue.

And they symbolized more than the broken hearts of Diana’s countless fans. The waves of that flood surged against the gates like some kind of apocalyptic judgment against the Royal Family, a rising tide threatening to swamp and even submerge the monarchy for good.

An expression such as this demands a response. But the response they desired did not come from the palace.Where was the Queen? Why weren’t the royals giving emotional public tributes to the woman Blair called “The People’s Princess”? Why couldn’t the cameras get inside that palace to give us the scoop? Where was the drama we demanded? And why wasn’t the flag above Buckingham Palace flying at half-mast?

The outraged public hunting for scapegoats, and the royals would not come down and weep and participate in the wild circus of public mourning, it was inevitable that the crown would become the target of a nation's rage.

And still the palace was silent. This eventually stirred up rumors, and anger, and eventually the kind of resentment that can boil over into violent action.

Stephen Frears’ film The Queen takes us into the middle of this chaos. And the result goes a long way toward answering the question of the royal family's silence, helping us to understand why Queen Elizabeth II failed to respond for so many days. Some may even come to agree with the way that the Queen handled Diana’s death. While Frears’ film is hardly a whitewashing of the walls of the House of Windsor — he lays the faults of the royal family bare for all to see — he does help us begin to grasp the reasoning behind the restraint, and the purpose of keeping certain things private rather than parading them out at the whims of the public.

Frears finds this conflict to be the heated core of many cultural tensions, and by focusing on the figure hidden behind the palace walls, he ends up revealing much not only about the scandal but about a continental shift in British history.

He takes us inside, where we learn that the royals really weren’t so devastated over the loss, except insofar as they had to comfort two boys who had lost their mother. To make a big emotional speech? That would have been dishonest, and worse (in their estimation), inappropriate. The Queen and her husband had been bothered by Diana, for she was so foreign to their legacy and traditions and sense of propriety. Diana made public things that they, in their embarrassment and shame, wanted to keep private. all of the matters within the palace a public affair. While they had been troubled by Charles’ infidelity, they hadn’t considered it their responsibility to deal with such family affairs on the public stage.

Still, it’s clear that they were partly to blame for the disaster. The royals proved themselves capable of covering up and ignoring their sins much the way the U.S. government is capable of covering up or downplaying the crimes of its own officials, or the way the church tends to be quick to absolve its own priests and pastors. The Queen isn’t a celebration and exoneration of the Royal Family — it portrays them as self-interested and avoiding any question of what sparked this crisis in the first place: Charles' deception and infidelity.

We watch as the Queen, who has always been bothered by Diana’s popularity, bristles as her son's dirty laundry is hung out on the front lawn for all to see. The customs she carries on have lived for many generations; so she assumes, as does her blunt, bitter, temperamental husband Prince Phillip, that this public hysteria is just a phase that will pass in a few days.

But it doesn’t. No, the world really has changed.

And it’s going to take Elizabeth a while to absorb the truth that the monarchy is not very well respected or understood any longer. When she wakes up to learn about the tragedy, it’s as if she’s waking up to a whole new era. The slow march of progress has gone on too gradually for the reality of it to sink into the royals heads and hearts.

Frears' film might have served merely to show the breakdown of the family as they absorb the discovery of their own declining importance. But instead, it serves to quietly and carefully awaken us to what it has cost Britain to shove this institution aside in the name of “modernization.”

We experience this awakening through the slow but admirable wizening of Tony Blair, who is played with impressive accuracy and intelligence by Michael Sheen.

When Charles (played by Alex Jennings, who does not resemble the Prince of Wales at all) returns Diana’s body to England, the queen slips away from the media circus and goes to Balmoral, hoping the whole thing will blow over.

Meanwhile, Blair does the dutiful thing in responding to the people and representing them, giving their grief an eloquent voice. And his popularity skyrockets. He might have let that heroism go to his head, and called for reform that would have toppled the monarchy and robbed it of any relevance at all.

But he did not. And the film portrays him as beginning to understand that this is not merely obstinance he faces. Early in the film, we see him rolling his eyes at the royal family. “Will someone please save these people from themselves?” he asks, exasperated. And his wife, Cherie Blair (Helen McCrory), writes off the royal family as a bunch of "freeloading, emotionally retarded nutters." But Blair isn’t willing to write the family off. He can see their naiveté and corruption, but he doesn’t want to throw the baby out with the bathwater.

It is, he begins to understand, the burden of a legacy weighing on Elizabeth’s shoulders. If she concedes to his requests to grant the people's demand for a speech and a public funeral, she betrays the tradition, and she shows that the crown is vulnerable to arrows fired from the spiteful kingdom of gossip. She refuses to surrender herself to acting at the whims of an impulsive and demanding people. But if she does not, the people may turn against the royal family and all of their history in contempt.

Some critics are saying the film portrays Blair as an opportunist, seizing the day to advance his own popularity. But in this film, I see more than that: I see a man who, like Diana, is impulsive, emotional, and intuitive. But more than that, he's also patient, willing to consider other perspectives... other cultures, in fact. He bristles when others suggest he’s merely playing a smart game. He becomes a sort of translator, justifying the ways of the monarchy to a disgruntled people, even as he tries to coax the Queen toward a sacrificial act in the name of reconciliation.

If the film has a weakness, it is not the way it makes a sympathetic hero of Blair. It is instead the way it gives little thought to one of the primary causes of the crisis. The monarch’s crime was not, as the people decided, an unwillingness to break their own rules and put on some elaborate charade. It was their willingness to cover up and give sanction to the prince in his infidelity in the first place. It was their silence, and thus their consent, to the betrayal of the symbol of marriage... marriage between husband and wife before God, and between the royalty and their public

Title and authority places upon a person more than the usual weight of personal responsibility — it places upon them the burden of leadership, and of preserving the meaning of symbol and ritual. When a king or a prince betrays his wife, or a president deceives his nation, he communicates to the nation that he lacks integrity and restraint and self-control; but worse, it communicates that he has no respect for the covenant of that marriage, or the value of a promise.

In protecting Charles and behaving as if it was Diana's responsibility to just tough out the affair, the royal family condemned themselves. This issue goes all but overlooked in the film.

But then agian, this is not a movie about Charles' unfaithfulness to Diana. It’s a film about the Queen's faithfulness to history, and to fulfill the vows she took.

Thus, when Elizabeth’s crisis point comes, it is not a breakdown over the death of Diana. It is instead a moment of surrender to the weight of her responsibility, after doing what she can to hold together what's left of her legacy. Her heart is broken with the help of a beautiful elk — a fourteen-point buck who inspires the local hunters. He comes to represent the beauty and elegance of Elizabeth's tradition, and it is shocking to see the utter disregard that some people, like hunters with rifles or tabloid reporters armed with microphones, can have for such regal grace and beauty.

Overall, the film is powerfully eloquent about the weaknesses of the monarchy's traditions, and even more eloquent about what we are losing as cultural trends slowly push that institution aside.

The last shot of the film is perfectly chosen. And I couldn't help but wonder if it offers a wry comment on the change: The queen and her Prime Minister are walking through the manicured garden, staying on the prescribed path, and who is it that runs roughshod across the grounds, disregarding these lines and ignoring the classical fountain and statues? The dogs.

Judging from the way many of the viewers around me yipped, snapped, and yelped at every opportunity to mock the queen and the monarchy, it’s clear that the dogs will continue to have their day.

While the film is about an historic British monarch on one level, it is, on another, about the reigning queen of British screen acting.

As she has proved again and again — especially in Robert Altman’s Gosford Park — Helen Mirren is a masterful actor. She can communicate with a quiver of her brow or the slightest tilt of her head more eloquently than most actresses can with a whole emotional speech. She has proven this again and again, reminding us that there is no substitute for craft and control.

In The Queen, it is precisely her craft and control that make her performance so powerful. If she wins the Academy Award this year — and she’s unlikely to have any serious challengers — it will be a lesson to those who think that scenes of emotional breakdowns or zealous speeches are the best opportunities an actress can hope for.

In this role, it is Mirren’s task to put on a mask that has hardened through centuries of tradition, manner, and duty. And her triumph is that she is able to convey a world of complex emotions through that mask. While the others around her burst with emotion, her quiet resilience slowly becomes a show of strength that demands respect. It is her restraint rather than hysteria, her quiet rather than a boisterous speech, and her effortless poise rather than grandstanding, that shake the house.

This performance is especially resonant because it reinforces the central lesson of The Queen. Mirren’s approach to acting is classical, formal, thorough, and subtle. It comes from a lifetime of practice, and her dedication to doing everything the way it should be done gives her integrity and strength. Based on the honors it usually hands out, Hollywood would have us believe that greatness lies in mere audacity, in the willingness to perform daring sex scenes or to burst into geysers of tears on cue. Mirren’s performances are not exhibitionism... they are slow-burn revelations that will stand the test of time.

And thus, it is a perfect bit of casting to have her play Elizabeth. For, like the Queen, she may be old-fashioned, but she understands the power and the purpose of restraint.

Here’s hoping that the Academy recognizes such exceptional work, and gets it right this time.

Perhaps they’ll even decide to honor the director as well.

There aren’t many directors capable of doing what Stephen Frears has done so far in his career. Think back on his wide array of notable, memorable films, which have spanned so many different subjects in strikingly different contexts, genres, and styles. From sumptuous period pieces like Dangerous Liaisons and Mary Reilly to the hip crime caper The Grifters, small-scale comedies like The Snapper and The Van, troubling thrillers like Dirty Pretty Things, and hip comedies like High Fidelity, he’s one of the most versatile directors working today.

And if I were asked to rate his accomplishments, I'd be tempted to call this one his finest.

-

Directed by Stephen Frears; written by Peter Morgan; director of photography, Affonso Beato; edited by Lucia Zucchetti; music by Alexandre Desplat; production designer, Alan Macdonald; produced by Christine Langan, Tracey Seaward and Andy Harries; released by Miramax Films.Starring - Helen Mirren (the Queen), Michael Sheen (Tony Blair), James Cromwell (Prince Philip), Sylvia Syms (the Queen Mother), Alex Jennings (Prince Charles), Helen McCrory (Cherie Blair), Roger Allam (Sir Robin Janvrin) and Tim McMullan (Stephen Lamport). 103 minutes.

The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King (2003)

An much-abridged version of this review was published at Christianity Today.

An much-abridged version of this review was published at Christianity Today.

•

In a recent British poll, U2’s song “One” was voted the greatest song of all time. Okay, perhaps it wasn’t a poll of musicians, historians, and songwriters, but of music fans. Still, the poll proves that U2’s song about longsuffering has struck resonant chords in its listeners over the last decade. The refrain, “We’ve got to carry each other…” is indeed powerful and true.

The song is not included in the soundtrack for The Return of the King, but the same sentiment, the same chord, is struck in a line of dialogue, in a vividly literal image, and in a metaphor that will move viewers to tears around the world for decades to come.

It happens when brave Samwise Gamgee, perhaps the most inspiringly brave soul to ever journey across a silver screen, cradles the suffering and battered form of his dearest friend, and determines to finish the journey on his own two feet if he has to. Sam is suffering the hardest thing that a loving soul must suffer—not his own personal torment, but the torment of seeing the one he loves suffering from a burden that cannot be taken away. Crumbling from the burden of grief, he grits his teeth and says, “I can’t carry it for you, Mr. Frodo, but I can carry you.”Read more

What are your favorite fantasy novels... for grownups?

We had a lot of fun a few weeks back considering what the best fantasy novels for young readers might be.

That prompted this question from a reader named Melissa:

I really enjoyed your recommendations for "what to read after Narnia" with your kiddos. We are loving DiCamillo!

Do you have a similar list for adults? I've read The Lords of the Rings, Harry Potter, and your books, and I would love to know what else is worth reading. I've looked on your site and haven't found a recommended books section, but maybe I overlooked it.

Well, Melissa, here's what springs immediately to mind:

- Watership Down - Richard Adams

- Winter's Tale - Mark Helprin

- The Gormenghast Novels - Mervyn Peake

- The Book of Atrix Wolf - Patricia McKillip

- Dune - Frank Herbert

- The Sparrow - Mary Doria Russell

- Momo - Michael Ende

- Sailing to Sarantium, and the sequel Lord of Emperors - Guy Gavriel Kay

- Sabriel - Garth Nix

- Sunshine, and Deerskin - Robin McKinley

That's my hasty, off-the-top-of-my-head response. I'm sure I'll revise it soon.

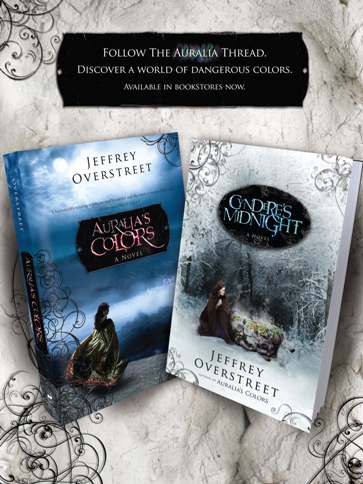

And of course, I'm rather fond of books called Auralia's Colors and Cyndere's Midnight, for some reason. :)

I'm sure this is going to open the floodgates, so brace yourself for the recommendations about to appear in the Comments. (I'll bet it takes about, oh, ten minutes for the name George R. R. Martin to pop up....)

Auralia's Favorite Bookstores

Auralia's Favorite Bookstores

You can find copies of Auralia's Colors and Cyndere's Midnight at any of your favorite bookstores, but these fantastic stores have been especially supportive in sharing The Auralia Thread with their customers and communities.

Many thanks to all of them!

Cyndere in Singapore

Cynthia writes:

Hello from hot and humid Singapore! I have become a fan of your blog for about 2 years now. It was introduced by a friend of mine who lives in LA. Generally I don't trust film critics, but I found an unpretentious opinion and style in your writing. I found myself going back to the blog over and over again, just to keep up with what's happening in the film world because obviously in this part of the world, we rarely get the non-blockbuster, mainstream, art-house/indie type of flicks. ...The main reason I'm writing is to congratulate you on The Auralia's Thread. It was a surprise to find Auralia's Colors in the book shelf of Singapore's BORDERS and when Cyndere's Midnight was released, I tried my luck only to find it, once again. It's amazing how powerful words can be; I probably wouldn't be able to sum up Auralia's stories in a few sentences but I sure can describe the visuals running through my head. It was as if your words are like the threads to the images of Auralia's world and once the images conjured up in your mind... they took over the words. Strange.Have fun in your book tours, readings and other promotional obligations. I love Seattle, and how I wish I could go to one of your readings. It is a perfect city for hearing Auralia's adventures over a good cup of coffee. Thank you.

My Third Conversation with Charlie Kaufman

I first met Charlie Kaufman when he visited Seattle to promote Adaptation. I met him again when he came back to talk about Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind.

About a week and a half ago, when he returned to Seattle to discuss his fantastic new movie Synecdoche, New York, I interviewed him a third time. This was the most enjoyable and in-depth of the conversations. A few short excerpts appear here, in my latest article for Image's "Good Letters."

Kaufman is one of my favorite interviews, because he loves to talk about big ideas and philosophy. I've always wanted to prompt him to share some of his views on faith, and this time, that opportunity came.

Eventually, I'll publish the whole conversation. But I've got to meet some assignment deadlines first...

Win an Auralia Thread poster!

So... I spilled the beans and mentioned that I have some glorious new posters for The Auralia Thread.

And I'm planning to give away ten of them.

Want one?

Come up with one of the ten most creative blog posts about Auralia's Colors or Cyndere's Midnight.

Here are the guidelines:

- It must be new, not a re-post of something you've done before.

- It must introduce readers to Auralia's Colors and/or Cyndere's Midnight in a creative fashion, giving them some idea about the book.

- It must include a link to your favorite bookstore website (Barnes and Noble, Third Place Books, whatever...)

- You're welcome to use photos, audio files, video... whatever you like. Be creative. But also, please be considerate. There are kids reading these books as well as adults, so keep it respectable.

I've appointed a couple of Auralia fans who will serve as judges, and they'll decide whether you have a poster coming.

When it's ready, email me with "POSTER CONTEST" in the subject line, and give a link to your blog post.

The contest is open until midnight on Christmas Eve!

Keep in mind, there are ten posters up for grabs, so your chances of winning are good.

I'm already sending a poster out to Catherine Gaffney, for what she did here...

Artist's Forum Part Two: The Artists' Compulsion

ARTISTS FORUM

The voices of artists on the front lines.

Copyright © 2002 by Jeffrey Overstreet

Reproduction is forbidden without permission of the author.

Contact Jeffrey Overstreet at joverstreet@gmail.com.

FORUM THREE: The Artist's Compulsion

from The Crossing, The Compelling Issue, published in Summer 1999

featuring: Alan Brozovich, Nants Iremonger, Carol White Kelly, Scott Nolte, Geoff Pope, Fritz Liedkte, Gary McKibben, Ervin Toucet, Kathy Pritchard, Patricia Emerson Mitchell, Jason Dorsey, and Matthew Winslow.

THE SUBJECT:

Some create because they like to play with creative stuff, like a kid with crayons. Others create because they have issues to work out on paper. An artist may, like Michaelangelo, explore the stone to find the figure inside. Another may have a passion to beat that stone into submission until it matches the vision in her head. Some write poetry to see more clearly. Others write poetry for the love of observing its effect on an audience. Some paint to praise God; others, to understand Him; others, to obey him; and others find they don't think about God at all in relation with their artmaking.

What compels you to create? What are the forces that draw you to your work? Tell us (in 400 words or less, please) why you do the work you do.

Here are some of the anecdotes and reflections they shared with us:

A DANCER:

Trying to explain the motivation behind an activity that comes naturally and that I enjoy immensely feels strange to me. I have to remind myself that not everyone feels the natural fit of dancing. Not everyone is at home with it. But for me, the drive to dance, to move to rhythm, is powerful. If the music speaks to me, my inner rhythm longs to reach out and connect. If the lyrical content is something that I feel strongly about, that longing to connect can turn to an ache. There are times when I find myself in a place or situation where I have to exert a conscious effort to not move because it would not be appropriate. When I get to make that connection with the rhythm, all is aligned with the world. It feels like coming home.

Listeners of music might feel one with the music in their minds. Musicians feel it when the music seems to take on a life of its own and instead of them playing the music, the music plays them. They’re in the zone and loving it. Dancers (trained or untrained) listen and respond with their bodies. If you dance, your instrument is your body—for tap dancers, especially your feet. And the music is playing you. Though learning the steps is vital, tap dancing is not about the steps. It’s about the rhythm, the groove, the connection. It is so right. I guess I do it to come home.

––You can find Renee Pinzon "at home" teaching tap dancing at Tim Hickey’s Dance Studio in Kirkland, WA.

A POET:

Poetry struggles to grasp something of beauty and distill it into words. When I write, I want to capture a moment, to condense it and hold it so that it is mine. Often those moments involve pain and brokenness. I think this is where the ache in poetry comes from—poets look at the world and see that all is not right.

Some Christians would prefer to gloss over brokeness, and focus only on the uplifting. But I don’t see Christ glossing over anything during his time on earth. He spent his whole life among broken, aching people. And while his miracles fixed some external brokeness, his mission was ultimately one of internal, spiritual healing. This requires honesty about what isn’t right in life.

Poetry finds beauty in the brokenness. It unlocks memory and sets free areas of pain. I believe God is honored by the truth and beauty that results.

––Alan Brozovich writes poetry and songs. He teaches

English and journalism at Rosslyn Academy in Nairobi, Kenya.

A MUSICIAN:

If you asked me why I play oboe and English horn I might have the audacity to answer as Flannery O’Connor did to a similar question referring to her writing. She responded bluntly, "Because I’m good at it." If one believes in the Creator, in the One who gives us our gifts and talents, it isn’t arrogance but a statement of truth and, thus, responsibility to say "I am good at it." If I am good at music, mustn’t I use this God-given talent to the best of my ability? Why would God give such an "unnecessary" and seemingly frivolous gift? We don’t need music to eat or breathe. Why should God bless any of us with artistic gifts? Perhaps because God’s chief end is, as John Piper says, to glorify Himself and enjoy Himself forever. As the Creator of all creators, I believe he values beauty.

He must believe it important. (Certainly His magnificent creation shows us that!)

I can instantly and easily state that one reason I do what I do is because it brings me great joy. There is nothing like the mournful sound of an oboe or English horn. There is something about the painful joy that it brings me. In a poem I described it: a "knife inserted, slowly twisted, steals my soul." While to some of you that might seem awful, to me it is awe-full.

But any musician might say the same thing I have just said. As a Christian I feel that my music is not merely to satisfy my desire to play, or to satisfy that of the audience. Ideally, it is to glorify God. It is, as well, a way for me to give others a different method of glimpsing God (whether they are aware of it or not!)

I think it all comes down to acceptance of my talent (admitting with a humble and thankful heart that God has given me this gift), obedience to my Lord (pursuing excellence in what I do), and praise to the Creator every time I place a reed between my lips.

––Patricia Emerson Mitchell is English hornist of the San Jose Symphony, principal oboist of Opera San Jose, and a freelancer. She has worked with a wide range of artists and groups––from Pavorotti to The Moody Blues to the San Francisco Opera.

A PAINTER:

I am compelled to create by two primary impulses: blood and water. By blood I mean my ‘gene pool.’ I am a son, grandson, and great-grandson of artists. My great-grandmother on my mother’s side, Fanny Y. Cory, was a nationally recognized illustrator of children’s books, a cartoonist and a superb watercolorist. (Her daughter, Sayre, inherited those creative juices, but marriage and a snide remark from her brother—"You have talent but no genius!"—dammed that creativity up.) My

father, Jack Dorsey, a brilliant artist but a bungling businessman, was a full-time professional watercolor artist in the seventies and early eighties. I didn’t realize it then—we were the epitome of the ‘starving artist’ family. But it was a fun life! I have photographs of myself painting outdoors at dad’s feet, as serious about my craft as a five year-old could be.

Perhaps an even deeper and more foundational impulse is water: I was born and raised on Camano Island. I am gripped by that place. The dappled colors dancing on the water at sunrise, the dark damp of the pathless woods, the grey mountains framing the glassy Sound, the cry of the eagle and the gull, and the splash of a salmon’s tail as it chases herring have woven themselves into my soul. Painting allows me to recreate this world surrounded by the waters—a world which, as Hopkins said, is "charged with the grandeur of God."

––Jason Dorsey of Seattle paints with oils and preaches as assistant pastor of GreenLake Presbyterian Church.

A SINGER/SONGWRITER:

Music is, for me, a multi-dimensional form of journaling. It is therapy and release. In a logical, bottom-line-driven world, music gives my soul a chance to express itself, and, sometimes, to be healed through that expression.

The forces that compel me range from anger and frustration to pure joy. Music can be a prayer of thanksgiving, a plea for understanding, or simply a new way of telling a story. Often a confession, music is always a catharsis, and sometimes a prophecy. Anticipating a season of change, I penned "Cocoon": "Take me to the center, bind me up / Keep me through the winter, bind me up / Wrap me in your hibernation, season of transfiguration…"

Composing and singing are what I do, who I am. Perhaps I understand this now more than ever, having just recovered my piano from its three-year home at Madison’s Café to bring it back to my house where it is more accessible. Not being able to play or write songs (at least, not conveniently) has amounted to an unwelcome vow of silence. My piano has been in my living room for two months now, and I must say, I’m feeling much more myself again.

––Kathy Pritchard is a singer/songwriter and co-founded Madison’s Café, a haven for performing artists and hungry Seattlites.

A WRITER:

I was thirteen when my dad, who owned a candy company, received identical Christmas gifts from two distributors, and gave one of them to me. The gift was an Executive Planner. It had monthly tabs and about ten lines to write on each day. I had previously been given journals and diaries, but they didn’t interest me. Dad’s present did, perhaps because it was a Planner just like his.

Soon I was writing about how I nervously shot a free throw over the backboard, how I liked a girl named Liz, how my friend Clay frog-gigged, how many yards I had gained in football games, how God both scared and cared for me. I never showed anyone my Planners and rarely shared anything I had written. The exceptions were love notes and writing in yearbooks. I would take friends’ yearbooks home and spend hours on drafts before committing my ink to the bound pages.

Then in college I read Heart of Darkness by Joseph Conrad. The book intrigued me to the point of envy. How could anyone have gripped me so intensely with his writing? Conrad’s plot and his insight into human nature captured me, but I was mostly seized by his vivid descriptions and the rhythm of the words; with these he took me into the heart of Africa, the heart of Man, the heart of Art!

I also read Melville and Eudora Welty, memorized lines by Milton, Donne, and Gerard Manley Hopkins. I was fascinated by their details and style, stunned by their perceptions and passion. My professors raved about Shakespeare and Blake. A teammate, while pole-vaulting, could recite lines by T. S. Eliot; another friend had read almost everything by Hemingway. I wrote papers on Faulkner, Virginia Woolf, and William Carlos Williams. I nearly worshipped James Joyce and e. e. cummings. And I wanted to write with the same spontaneity, vision, and skill. I was compelled to try. I imitated. I rearranged. I imagined—and created! And I am still compelled at 35 to try to create like the great writers, especially the poets.

––Geoff Pope is an award-winning poet and teacher in Seattle.

A DIRECTOR:

Artists should be the most curious observers of people and society. As a theatre artist, I’m interested in the what, why, how, and where of life, and I respond with stories that should be told and heard by people living today. (Why tell a story no one wants or needs?)

I like questions. I like plays that pose questions. Personally, I know about God’s ultimate answers to some of my questions, but rather than impose that on an audience, I look for the script with questions that beg his answer. Jesus’ parables created new questions in the mind of the hearer. Unlike some preachers who ramble on and on with Answers, Jesus placed the responsibility with his audience to personalize, analyze, wrestle with and claim the truth.

––Scott Nolte is the Producing Artistic Director

at Seattle’s Taproot Theatre Company.

A PHOTOGRAPHER:

I’m about as interested as the next guy in knowing the Why of what I do. I’ve thought much about it, and reasons do surface: incarnation, expression, therapy, embodiment, beauty, yearning, seeking the source, being made in the image of the Creator, love. Such matters are important to consider, and deepening my understanding enriches my life and work. But sometimes I become bogged down by too much pondering. It’s then that I throw up my hands and say, "I dunno! I just like to make things." And then I go and do so.

––Fritz Liedtke is a photographer and writer in Portland, Oregon.

A POET:

Long aware of the power of words, late in life I have come to putting them on paper with some intentionality and discipline. That they are in the form of poetry both surprises and delights me, as does the fact that creating this poetry, arduous and prolonged a process though it may be, feeds my soul. Why now, why this medium after all these years, I ask myself. As a child of the Depression raised in a house where money was scarce and love of the written word was palpable, I was as well a young woman of those rather innocent and politically incorrect fifties. I went to college, yes, but my graduation was followed quickly and without question by marriage, children, involvement in church and community. Writing, that gift that had been encouraged by my parents and professors throughout my growing up years, gave way to preschool and PTA’s, Betty Crocker cookbook dinner parties, and desultory book discussions. Only after the comfortable predictability of this life was broken by divorce and the discovery that a family-secret genetic disease had presented in my husband did I wake up and begin to write.

Through the twenty years that he lived with and finally died from Huntington’s, my fountain pen bled ink. Now I wrote down fear, anger and remorse, tears, forgiveness, and reconciliation, courage, laughter, and love. Now I wrote, and will continue to write, as Seamus Heaney describes poetry, "truth told slant." That slant tells me what I need to know, what I fear to know, and, over and over again, what I long to know, that God’s abiding grace falls indiscriminately over our flawed and blessedly, beautifully ordinary lives.

––Carol White Kelly writes poetry in Seattle.

A MAGICIAN:

I have always had a desire/need to "play." It goes as far back as I can remember. It is play for me. I can still remember what it turned me on as a kid and I get to do the same things now as an adult to hopefully delight other kids. . . grown or otherwise. I do a magic trick where the handkerchief gets stuck on my hand and I can't shake it off. It is an effect I would have loved as a kid and I always hear at least a few kids cracking up at my antics. I see myself in those kids. That is me as a child. For some reason it is very satisfying to experience this.

For a long time I felt like a "freak" in the Christian circles. Now I don't really care. My interests have opened doors for witnessing and evangelism. I have always loved hockey. I taught my son and son in law how to play. We have had an effect being a witness to other hockey players even to the point of saying the closing prayer at a marriage where the bride and groom walked out of the marriage ceremony under a "canopy" of upraised hockey sticks. Traditional "safe" Christians would never have had this opportunity. I became interested in performing magic. It opened doors for me working with gangs in Chicago working with David Wilkerson. It disarmed a couple potentially dangerous situations where I was now considered "cool" after performing a couple tricks. It made me welcome where I would have otherwise been considered an outsider.

Playing hockey, juggling and doing tricks are things that I occasionally NEED to do to stay on an even keel. They are like pressure relief valves in my life. I used to apologize for having these needs, but now I come to acknowledge them as "gifts" from God. They are just what I am. To deny these needs is to deny part of who I am.

—Gary McKibben (sometimes called "Professor Gizmo"), is a magician, juggler, and hockey player.

A NOVELIST:

I write because that's what I enjoy doing. I'm reading John Piper's Desiring God right now, so I think my answer [to this Forum question] would probably be that in doing so, I take delight in our Lord. Tolkien discusses this in On Fairy Stories, how any creation by an artist is really a sub-creation of the true Creation. When I write, I take delight in being a part of our Lord's Creation.

—Matthew Winslow is working on novels in Seattle, Washington.

Artist's Forum Part Two: Artists and Criticism

ARTISTS FORUM

The voices of artists on the front lines.

Copyright © 2002 by Jeffrey Overstreet

Reproduction is forbidden without permission of the author.

Contact Jeffrey Overstreet at joverstreet@gmail.com.

-from The Crossing, The Critical Issue, published in Winter 1999-

featuring: Todd Driscoll, Nancy Dyer, Fritz Liedtke,

Chad Sides, Jim Stark, and Rich Swingle

THE SUBJECT:

We asked a variety of artists how they deal with criticism--both praise and derision. Are they ever tempted to compromise to avoid bad reviews? How do they discern which critics to hear out and which critics to shut out? And how do they turn criticism--even when poorly communicated or downright nonsense--into a benefit?

Here are some of the anecdotes and reflections they shared with us:

Jim Stark:

There are many traps waiting for us. First a tender one—our close friends and family. They may praise our work even when we know it is inferior, or shatter our confidence by criticizing work which we feel is ‘right’. Colleagues can do the same thing. And our expectation of opinions can be even more dangerous. We can be tempted to plan our work to please the experts rather than the rest of the audience, substituting a display of technique for real truth, real viability, in the work.

At all times, we are our own worst enemies—we can make so many different kinds of mistakes! Aside from the mistakes we might make within the work, there are the blunders which can invalidate our work before we even begin. We might choose the wrong goals for our work at the outset, or indulge our own personal tastes to the detriment of the final product. We might give too much credence to praise or blame from those who are working with us, displacing our focus from its proper object. Worst of all, we might seek praise before excellence.

The best response we can hope for from the audience is a mix of laughter and tears. The best way we can respond to criticism is, once having taken its value to heart, to wake up the next morning having forgotten it.

Jim Stark wandered as a professional theatre gypsy

for years before settling with his wife

and two year-old daughter in Hanover, Indiana,

where he teaches theatre at Hanover College.

Now he knows his audiences by name.

Nancy Dyer:

When a friend is critical of my work, as long as it is done without intent to hurt, I appreciate their suggestions. That type of criticism helps me see what others see when they look at my work. I want to learn to look as an outsider at my work so that I can make my work as accessible as possible.

It hurts when someone reads something I wrote and hands it back with barely a word. Or when someone looks at a still-life drawing and says, ‘What is it?’ It is discouraging not to be understood.

I maintain balance by having a few friends around me who believe in me and my abilities and are always ready and willing to participate in my creative process, whether it's viewing what I've done, acting as a sounding board for one of my ideas, or encouraging me to stretch my skills. I also remind myself when someone doesn't appreciate my work as much as I'd like them to, that not everyone has the capacity to appreciate all forms of creativity. For whatever reason, God has placed a desire to create inside of me, so I must.

Nancy Dyer of Seattle is a graphic designer by profession.

She has always dreamed of being an artist and loves writing,

drawing still life pictures, and taking "art" photographs.

Todd Driscoll:

The kind of response most valuable to me is one which clearly indicates why the individual enjoys a particular photograph or why they do not. "I really like your work," with no explanation of what is aesthetically pleasing or moving (i.e., the composition, lighting, etc.) does not benefit me as an artist. If, on the other hand, they merely criticize the work, but offer no reason for their reaction, it definitely doesn't help me improve my work. I don't mind criticism, but it must be constructive.

Todd Driscoll is a professional photographer and aspiring screenwriter in Seattle.

Chad Sides:

The biggest compliment anyone can give me is to tell me they enjoyed reading or hearing my poetry. I value this over praise of my speaking voice or any prose I write. It is because poetry is the only thing I don't do for an audience. I write for myself and for God. I never sit down with ‘What will others think when they read this?’ on my mind. I just write until I feel a sense of completion.

I do appreciate constructive criticism from poets I respect because I know I can always improve, but this is usually done in a setting where I am also criticizing the other poet. If I can't take it I shouldn't be giving it…. Criticism given with an edifying spirit is easily swallowed; it must stem from knowledge, be delivered in love, and be accompanied by praise of the good. It also keeps the ego in check, if it's not out of hand already.

Chad Sides writes poetry and works to help promote Christian musicians.

Rich Swingle:

I've been touring for three years with a one-person play called A Clear Leading. It tells the story of John Woolman, an early American Quaker who spoke out against slavery over a century before the Civil War.

The current version is the fourth, and each of those four versions has had numerous refinements. If it were software, this would be A Clear Leading 4.7. Those revisions have, for the most part, been inspired by outside sources. Most of them have come from invited sources: people I respect enough to ask for criticism. Many, however, were unsolicited. Through honing your craft and seeking the Lord's wisdom, hopefully you build a greater understanding of which piece of criticism to use and which to cast aside.

On this last version, I felt I had it! I was receiving standing ovations, so I thought rewrites were history. Then I performed it at a Quaker college and was castigated because so much of the storyline is fictionalized. I took immediate steps in way of publicity, program notes, and epilogue so that people no longer suspected that every character and incident was a fact of history.

"Whew!" I was done...I thought. I had a piece that portrayed Woolman in a way that could have happened, though it wasn't in any history books, and I was making that clear to audiences.

But I continued to receive feedback from Woolman scholars who showed me that I had elements of the story that were in opposition to known facts. I gave Woolman's parents a slave: they didn't have one. I gave Woolman's love interest (and future wife) a brother: she didn't have one. If this were a painting I could have covered those things up. But a play is like a machine: if you take away or alter a small spring or bolt, the whole thing doesn't work.

So now I'm hard at work on version 5.0, gearing up for a New York production in January. Rewriting has already lead to improvements. I'd appreciate your prayers...and your feedback.

Rich Swingle lives in New York where he leads

The Lamb’s Theater, writes plays, and acts in them.

Fritz Liedtke:

Viewers make comments about my photographs in their body language, words and purchases (or lack thereof). Such comments may be encouraging and insightful. I learn much about a photograph from what others see and feel in it; their perspective broadens mine. And yet, disparaging comments—or the lack of comment altogether—can lead to doubt and questions about both myself and my work.

Ansel Adams says, "I do not believe that anyone can (or should) attempt to influence the artist in his work, but the artists should remain alert to comment and constructive observations—they just might have potential value in promoting serious thought about the work. … The photographer should simply express himself and avoid the critical attitude when working…. Only when it is complete should we apply careful objective evaluation to our work."

It is difficult both to remain open to others’ comments and remain true to my personal vision. I believe that working for the sole purpose of winning others’ praise is a sort of prostitution, and is not true to the unique vision God has given me. I am responsible to do my work, just as you are responsible to do yours, and nothing less.

We long to share our vision and handicraft with others, and perhaps to expand their experience and vision. But we also long for approval and encouragement. I have to remind myself that even if nobody but God and me saw my work—though that would be terribly difficult—it would still be worth doing. Why? Because it glorifies God, and that is what my life is for.

Ultimately I must be concerned with the praise of God, with ‘fame’ in his eyes. As C.S. Lewis says, "…Not fame conferred by our fellow creatures—fame with God, approval or (I might say) ‘appreciation’ by God. …This view [is] scriptural; nothing can eliminate from the parable the divine accolade, ‘Well done, thou good and faithful servant.’"

Fritz Liedtke is a photographer living in Portland, Oregon.

His article "On Singing Well" appeared in the premiere issue of The Crossing.

Artist's Forum Part One: Artists and Honesty

ARTISTS FORUM

The voices of artists on the front lines.

Originally posted in The Crossing.

Copyright © 2002 by Jeffrey Overstreet

Reproduction is forbidden without permission of the author.

Contact Jeffrey Overstreet at joverstreet@gmail.com.

FORUM ONE: Artists and "Honesty"

-from The Crossing, The Honesty Issue, 1997-

featuring: Bob Briner, Michael Demkowicz, Clint Kelly, Reverend Michael Kelly, Scott Nolte, Rose Reynoldson, and Bryan Rust

THE SUBJECT:

The novelist grumbles as he re-writes a book to please the publisher, because the process smacks of compromise, of "dishonesty". A songwriter shares melody and poetry with an unresponsive audience, and she is wounded by the undervalueing of her "honesty". An actor berates what can or can’t be portrayed onstage, because such limits prevent an "honest" performance. Veterans complain a Vietnam War film is not "honest about the truth of the situation in Vietnam." Honesty is a virtue. Isn’t it? For artists?

We asked some experienced artists--as well as some patrons of the arts--a series of questions about honesty and artmaking. Do you find it risky or difficult to be honest in your own art? If so, what risks do you face? Where and when do conflicts arise? What do you do about them? What do you see as an artist’s responsibility in balancing what he or she desires to communicate versus what the audience wants, expects, or needs to hear?

Here are some excerpts from their thought-provoking replies.

Rose Reynoldson:

In writing fiction and/or poetry, I always encourage writers to be transparently honest in their writing. When we hope to conceal or not reveal some true incident or thought, it's like a girl who goes to the doctors and says, "My friend thinks she's pregnant. What should she do?" And the doctor says, "Let me examine you and see if you are really pregnant."

That is, the reader senses such subterfuge and tries to psyche the writer out to determine what the truth is. But if we are gut-level honest, the reader gets a jolt of impact and experiences—perhaps even understands personally—what is written about and doesn't consider the writer at all.

It's like the eel in the depths of the ocean that escapes possible predators by emitting light, thus blinding its pursuer. By honesty we escape readers' trying to read us instead of our stories/poems.

—Rose Reynoldson is a published poet and taught imaginative writing at Seattle Pacific University for many years. She now lives in Wenatchee, WA.

Clint Kelly:

When King David was at his spiritual height, he was deepest in confession. The power of Schindler's List is that it does not look away from man at his worst. The glory of the Cross is that the Creator, bloodied and dying, hangs there in your face. In all of these examples, Redemption comes on the heels of "defeat" and is all the more beautiful and desirable because of the struggles that occasioned it. Find a venue where your honesty works. It may require you to switch mediums or to leave familiar country for parts unknown. Time is short. Make your move.

—Clint Kelly is a published author of novels, non-fiction books, and journalism.

He is also copywriter and publications coordinator for Seattle Pacific University.

Scott Nolte:

One of my actors is playing a character that swears - in a play at a different theatre! I got phone calls from well-meaning Christians telling me to rein him in. The actor's risk in telling the Truth, is that Bad People talk Bad (like fallen creatures). Any artist willing to point out the fallenness of our society (and its need for Redemption) will run the risk of his brethren's judgment, since many have blotted out their own pre-redemptive memories, words, actions. What they were redeemed from is anyone's guess!

I have Ps. 37:3 (NASB) on my screensaver. If an artist truly "dwells in the land, and cultivates faithfulness" he knows his community and is known by them (both are known by God). His work is less suspect because it comes out of love, respect, connectedness, faith, trust, grief, compassion and knowledge. If we were less preoccupied by "Our Art, Vision and Giftedness", and more cognizant of people we see/touch/smell/vote with, our voices might be heard far beyond our wildest dreams.

I have a long term vision for my audience. I'm praying that as they know us they'll want to maintain a relationship of trust and discovery. I can't tell them all my thoughts or expose all my styles today, any more than I should teach my nine year old welding. It's not safe, yet. The artist's relationship with a viewer/reader/audience member is like a cross between a tour guide and a discipler. We can point things out, but we must know our community well enough to be sure they see just a hair more than they wanted to.

-Scott Nolte is an actor and director of Seattle’s nationally-acclaimed Taproot Theatre.

Bob Briner:

I am not sure what I do in writing should be considered art. It seems to me to be more of a craft. I wish I could write artistically, but I see myself as more of a journeyman.

However, questions of honesty and its costs do come up. Recently, I did a column for a national magazine in which I praised a small college and its students for stepping out on a big national stage to represent Jesus and the Gospel. A part of the story seemed to me to be that these students came from a tiny, very unattractive town(a Nazareth) but still performed brilliantly in a very cosmopolitan undertaking. The problem was that I seemed to offend more people with my comments about the unattractiveness of their town than I encouraged by my praise of the quality of the service they performed. Honesty has its price.

-Bob Briner is the author of Roaring Lambs, a book of interviews

with Christian artists that are influencing cultures around the world.

Reverend Michael Kelly:

"Cut the baby in half!" That graphic command of absolute brutality came from the wisest man who ever lived.

Certainly only a few truths are more urgent and fundamental than which womb that child came from and whose breast he would suckle at. Truth is easily lost in unverifiable testimony. The intense nature of King Solomon’s famous case compounded the confusion and raised the stakes. He certainly had the authority to carry out his order, but it is apparent that he also had the wisdom to know he would never need it.

The artist has been given a similar power to reveal truth. But the artist’s power is best used when tempered by wisdom. The wise and powerful artist knows that his pen or her brush can sweep deeply enough to kill, but is more wisely used to simply expose us that we may either live better or die a bit more on our own. This art does not leave us unchallenged or un-molested by truth, it simply leaves us room to find the hope and life that truth always brings, even when that truth is stark and brutal.

My hope as a pastor and as a Christian is that art by Christ’s followers has the power to expose dark places and the wisdom to leave those newly illuminated souls a place to live in the light of that truth.

—Rev. Michael Kelly, Green Lake Presbyterian Church, Seattle

Bryan Rust:

When writing lyrics or poetry, I often find myself using fictional situations or characters to describe an emotional state of mind. Any time someone delves into fiction, there is a danger of hiding behind "fuss and nonsense". I have to take care that there is an experiential truth at the heart of every piece of verbal camouflage. This truth has to be reflected in the place of choice names and character names, in the choice of evocative words and phrases.

Occasionally, the best way to say something is to state it as plainly as possible. However, there is a tendency towards penny-plain literalness in most late 20th century writing. I would like to see more writers (myself included) push themselves to use language in new and unexpected ways. Greater artistic risks must be taken to get to the core of communicating universal truths.

— Singer/songwriter Bryan Rust recently completed his second independent release "Immaculate Misconception".

Michael Demkowicz:

It is always a risk to be honest in my art. My ego comes in for a continuous thrashing. The work consistently shows me — and others — with embarrassing frequency, how little I know and understand about what I am doing after twenty years. Both my seeing and my craft aspire to transcendence and excellence, but the reality is too often merely adolescent and mediocre. As a photographer, I am not merely exhorted by, but bound by the William Carlos Williams dictum: "No ideas but in things." The things I explore with my camera may prove stale to some, controversial to others, since the medium precludes direct statement. Others’ opinions may help, but too often they distract. Sometimes they may lead to conflict. All I can do is listen carefully, note what rings true, check my motives, and keep on working. Aspiring to transcendence and excellence is a tall order, but I agree with John Ciardi when he asks: "Why go to art for anything but the hugest and most lovingly involving difficulties? Why die in a puddle when there are oceans to drown in?"

— Michael Demkowicz is a professional photographer in Portland, Oregon.