Hoop Dreams: Why the Academy Snubbed It

At long last, we know the story about why one of the great American documentaries was kicked to the curb by the Academy. Here's the story.Read more

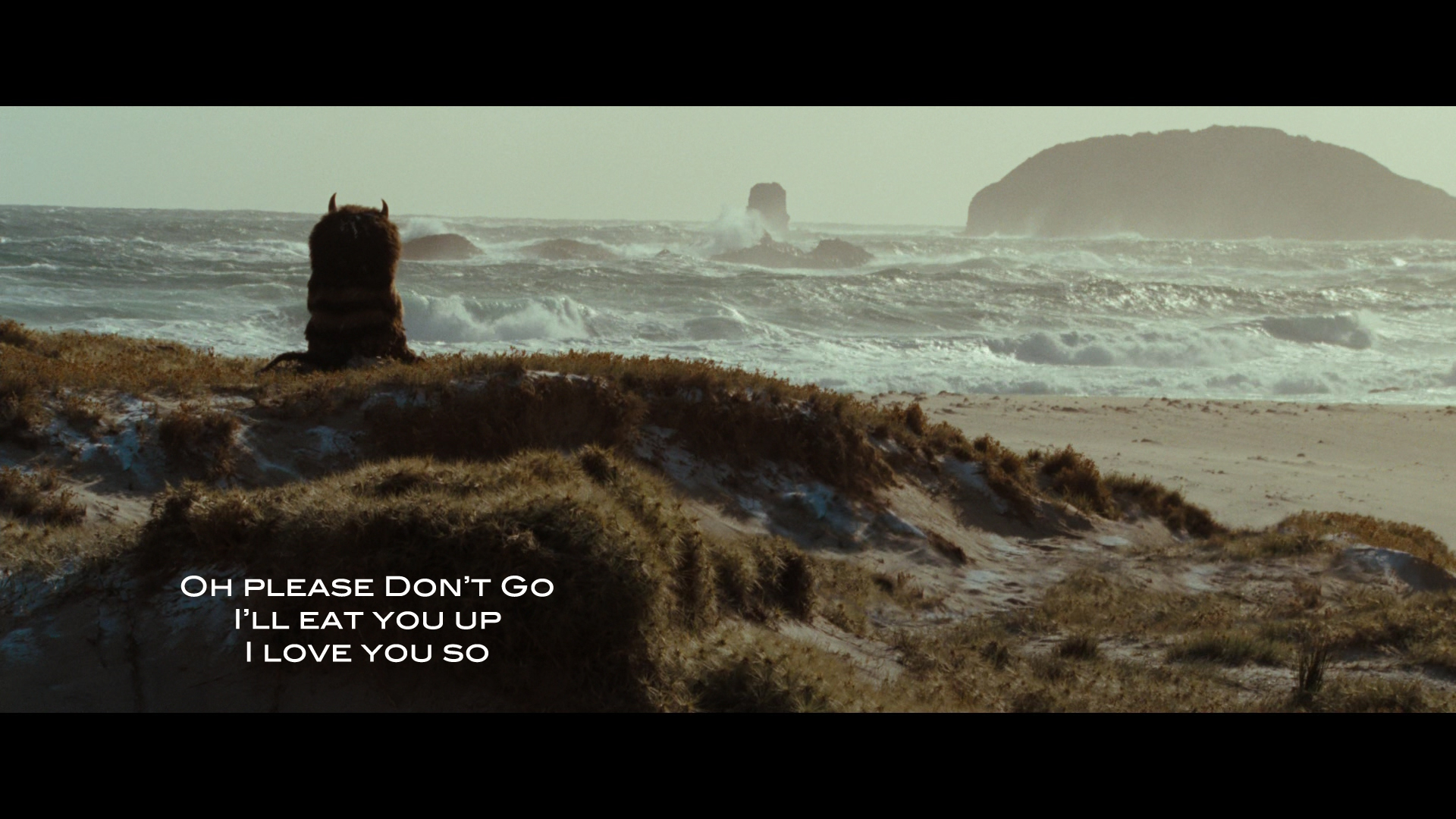

Where the Wild Things Are (2009)

This review was originally published at the Image blog, Good Letters.

This review was originally published at the Image blog, Good Letters.

-

By the time Max shouted “Let the wild rumpus start!” on opening day ofWhere the Wild Things Are, a rumpus was already raging among the film’s critics.

Reviewers have been roaring and beating their chests in debate. Were director Spike Jonze and screenwriter Dave Eggers faithful enough to author Maurice Sendak’s lavishly illustrated pages? Should they be treated like kings? Or sent to their rooms without dinner?

I’m not too concerned. Debating Peter Jackson’s fidelity to J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings makes some sense, as Tolkien gave the filmmakers an encyclopedia of detail. But Sendak’s Where the Wild Things Are contains—count them—ten sentences in forty eight pages. How could the movie be anything but an extravagant embellishment?

Do the filmmakers show respect for Sendak’s work?

Enough, I think. What is more—they avoid the pitfalls of so many storybook adaptations.

Wild Things might have been just another crass cartoon, the blanks filled in with relentless snark, fart jokes, and unnecessarily frantic tangents. Most mainstream filmmakers would have made the monsters’ wild rumpus the film’s raison d’être.

Instead, Jonze and Eggers have crafted a thoughtful, poetic, personal interpretation.

And while I’m disappointed that they skipped my favorite images—the transformation of Max’s bedroom, the Sea Monster, the Wild Things swinging from branch to branch — I’m impressed with the film’s approximation of Sendak’s artwork. The set designs and costumes have fantastic textures. Fabric, fur, and glue give the creatures a convincing weight that no digital code could equal.

Nevertheless, the film’s most marvelous wild thing is Max. The actor, nine-year-old Max Records, reminds me of Kelly Reno who played Alec in The Black Stallion — there’s a similarly genuine awe in his face as he tames a magnificent mystery. He makes Max a big-screen rarity: a complicated, surprising, real-world kid.

It helps that Eggers has read between the lines, filling in what Sendak’s prose didn’t say. He’s wrapped his screenplay around its most significant mystery, a question some readers never consider — the absence of Max’s father. Due to the film’s fleeting mention of Dad, the film canbe “read” as a poetic meditation on childhood in the aftermath of divorce.

And why not? Max’s unruly behavior, his powerful compulsion to escape into a world where he’s in charge, his imagination’s monsters — these have always suggested that Max is more than a little upset about something.

The father’s absence casts a shadow over the film. It explains why Max’s mood darkens with every perceived abandonment. When Claire runs off with friends, he’s ruined. When his mother divides her attention between a job and a boyfriend, he riots.

It makes sense that Max would protest, run away, and sail into the storm of his subconscious. Like Ofelia in Pan’s Labyrinth, he plunges into a dark wood where monsters present him with challenges relevant to his “real world” trouble.

The Wild Things—marvelously animated by the Jim Henson Company’s master puppeteers — are as big and fuzzy as the furry critters of Hayao Miyazaki’s My Neighbor Totoro. But they’re not the quiet, comforting helpers of Miyazaki’s world. As in Sendak’s storybook, they’re menacing and miserable.

And in Eggers’ interpretation, these bad animals are prone to betrayals, cliquishness, and smashing up their own homes. That is to say, they’re not just manifestations of Max’s rowdy spirit. They’re revealing his experience of the “big kids” and grownups back home.

The first phase of Max’s fantasy—in which Wild Things submit to his will—is typical of kids who want their own way, who want to dominate their superiors. But like most artists, Max reaches a point where his invention takes on a life of its own. Succumbing to selfishness, prejudice, and disloyalty, the Wild Things disappoint him, reflecting how bigger folks have let him down.

The burly beast called Carol becomes like Max’s ideal Dad, a rowdy giant who obeys his whims. But Carol eventually reveals jealousy, prejudice, and an explosive temper. His contentious relationship with KW, the most maternal of Wild Things, is revealing. Their disputes hint at what Max might have heard before his father left.

When he tries to resolve such conflicts, his subjects answer with his own brash retorts. Exasperated, he repeats his mother’s scolding: “You’re out of control!”

But we see more than Max’s troubles. His longings burn bright as well, illustrated most powerfully when the Wild Things collapse after a “rumpus,” sleeping happily in “a big pile,” suggesting a harmony that Max is missing. Putting the Wild Things to work on a utopian fortress, he shows his desire for creative collaboration.

Wild Things isn’t Spike Jonze’s first exploration of these themes. Being John Malkovich was about adults living out their self-serving fantasies, controlling and manipulating others to satisfy beastly desires. That story ended without any hint of grace, its characters burning in a hell of their own making.

Malkovich is definitely not an all-ages film, but I think Wild Things is a fine, challenging film for young moviegoers. It will challenge its adult viewers too—especially parents and teachers. Children often feel powerless in the turmoil we unleash. If we tell them they’ll just “have to adjust” to the consequences of our selfishness, they might do more than invent wild things. They might become them. I’m surprised that the end credits didn't employ David Bowie's classic song “Changes.” He sings:

And these children that you spit on

As they try to change their worlds,

They are immune to your consultations,

They’re quite aware of what they’re going through.

I’m grateful for the glimmer of hope in his take on Wild Things, just as I’m grateful for Sendak’s enlightening take on The Prodigal Son. I, too, visit my imagination’s “wild things” through storytelling. The beast-men I encounter there take on lives of their own, often reflecting my own failures and sins back to me, sending me home sobered, humbled, grateful for the “hot soup” of grace.

Moviegoers Who Stare at So-So Comedies

Meh.

Or better... meh-eh-eh-eh-eh-eh.

The Men Who Stare At Goats is... amusing. Not much more than that.

Guillermo Del Toro's Hints About "The Hobbit"

TotalFilm has a revealing interview with Guillermo Del Toro about his two upcoming Hobbit movies.Read more

Criterion's Wings of Desire: My Favorite Movie Gets Its Ideal Treatment

The best way to see Wings of Desire is on a very big screen. But it's also important to see a print that delivers its extravagant imagery without distortion or damage. Thanks to The Criterion Collection, a pristine version is now available on DVD and Blu-ray.

My revised review of the film is here. Read more

"Raven's Ladder": Somebody's Starting Rumors

Uh oh.

Now I'm getting notes in my email that a copy of Raven's Ladder has slipped out of the publisher's hands. And somebody's read it. And they're spreading around reports like this one and this one. How delightful... I mean, how premature!

Read more

The Blue Raft on Cyndere's Midnight

Many thanks to the folks at The Blue Raft for their encouraging words about Cyndere's Midnight. Read more

Lorna's Silence (2009)

An earlier version of this review was published at Good Letters, the Image blog.

•

NOTE: The following article discusses specific plot details that qualify as "spoilers."

You’d think after thirteen years of marriage, Anne and I would be able to read each other’s minds.

"Why did you flinch just now?"

"What? I didn't flinch."

"You did. I asked you a question, and you flinched. Why did you flinch?"

Truth is, I really don’t know. After 39 years, I still don’t understand—or particularly like—many of my own emotional responses, thoughts, or motivations. And I’m particularly oblivious to my expressions and what they convey. I might be good at poker, since I apparently have some confusing and unintentional twitches, but then again I’d be terrible at reading other players. I’ve learned that jumping to conclusions about others’ minds can land me in a world of trouble.

Considering how complex our thoughts can be, not to mention the myriad ways we can send confusing signals to one another, it’s a wonder that we ever connect with anybody in a meaningful fashion.

Perhaps that’s why the films by Jean-Pierre and Luc Dardenne fascinate me.

In five powerful movies, these celebrated filmmakers forego the conventions that make big-screen characters easy to read. Their work is characterized by close observation. They turn off soundtrack music, avoid special effects, and deny us anything in the way of exposition and back story. We’re dropped into tense, life-and-death circumstances in medias res, and left to find our bearings. Their actors are masterful in bringing mysterious, unpredictable men and women to life. Just when we begin to draw conclusions about them, something happens to make us question our assumptions.

In the Dardennes’ third film, The Son, we watch Olivier, a carpentry teacher, instruct young apprentices. As he waits for a new student named Francis to arrive, he becomes twitchy and anxious. When Francis shows up, Olivier starts sneaking around and spying on him. Viewers are likely to worry that the carpenter is following some sinister, depraved impulse. But when we glimpse the private storm raging behind Olivier’s blank expression, our understanding is transformed.

In their new film—Lorna’s Silence—a beautiful but inscrutable young woman behaves with what seems to be heartless cruelty. Lorna (Arta Dobroshi) is a young Albanian earning wages as a dry cleaner in Liège, Belgium. She shares an apartment with Claudy (Jérémie Renier), a heroin addict who has been paid to marry her so she can become a Belgian citizen.

Fabio, the crime’s overseer, has promised Claudy more money if he’ll divorce Lorna after she gains citizenship. A Russian mobster is next in line to marry Lorna so he, too, can be a Belgian. What Claudy doesn’t know is that Fabio and Lorna have agreed to kill Claudy with a drug overdose to save money.

Lorna seems to accept the murder plot without flinching. Her mind and heart are set on opening a snack shop with her Russian boyfriend Sokol.

But the more time Lorna invests in her marriage charade, the more Claudy asks of her in his fight against drug addiction. He doesn’t want a divorce. He needs Lorna’s help, because he knows he can’t clean up on his own.

Compared to Lorna, Claudy’s an open book. He’s a drowning man crying out for help. His need is writ large in his face and frantic behavior. Forcing him to sleep alone, in anguish, on the couch, Lorna shuts herself in the bedroom. But when we see her striving to convince Fabio to abandon the murder plot, we detect something awakening inside her.

In truth, it’s something more powerful than pity Lorna feels. When she asks Claudy to beat her—hoping that bruises will convince the authorities to grant her a divorce, thus making murder unnecessary—Claudy’s response reveals that he’s more humane than her co-conspirators. And later, when she catches him on the verge of self-destruction, she leaps into action trying to save him. They end up fighting on the floor.

So much for hiding their feelings. That visceral struggle on the floor breaks down any barriers that concealed the truth about Lorna. In what happens next, she and Claudy discover and reveal exactly who they are. They’re vulnerable and starving for love. They need to be needed. Maybe they have something to offer each other after all.

In the Dardennes’ five recent films, individuals pursuing survival and fulfillment are awakened by the subtle work of conscience to their need for love and for each other. And the desperate decisions they make, breaking their “silences,” are often costly and burdensome.

This awakening usually leads to a break from the city’s mean streets. The Son concludes in the woods, where a struggle becomes like the vigorous, furious embrace of tough love. InL’Enfant, a criminal on the run ends up seeing the truth about himself in the midst of freezing waters, and this provokes his first courageous, selfless act.

In Lorna’s Silence, conscience frees Lorna from her enslavement and she flees into the wild. It’s as if she’s stepping out of a dehumanizing civilization and into a spiritual realm. In her bright red pants, she looks like a fairy tale character running from wolves. At last, she has faced the truth of cruelty, and she goes looking for something kinder. She’s seen that what she wants and what she needs have been confused.

As Lorna seeks refuge, we’re given inklings of a new life beginning. The sphere of her concern has expanded to include the well-being and safety of somebody else. We hear the strains of a Beethoven sonata—a rare occurrence of soundtrack in the Dardennes’ work—as if it represents a groaning too deep for words.

Lorna may not be safe. But at last, she’s expressing the reality that she denied and concealed for so long. She knows the truth and it has set her free.

Maybe that’s not such a bad idea—a break from the city, a cabin in the woods. Maybe there I could hear myself think. And figure out why I flinched.