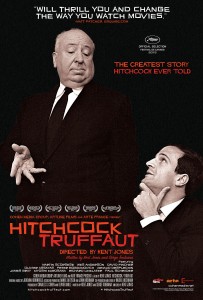

Many thanks to Joshua Wilson, who blogs over at F for Films, for sharing his impressions of Kent Jones’s new documentary Hitchcock/Truffaut — a film I’ll catch as soon as I have a good opportunity. Thanks, Josh!

•

As chance would have it, I finally picked up my own copy of the classic book Hitchcock/Truffaut this past summer, the same year that a documentary on the subject was released by Kent Jones. As a further coincidence, I realized that the film would be playing at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, the very week that I finished reading the book. So this past weekend I went to see the film in a sparsely attended theater, eager to see what Jones could add to Truffaut’s groundbreaking study.

The film opens with a brief introduction to the book, its author, and the subject. The book, first published in 1966, was assembled primarily by author and filmmaker François Truffaut from a series of interviews he taped in 1962 with the great director Alfred Hitchcock, with assistance in translation by Helen Scott. A Revised Edition, which completed Truffaut’s assessment of Hitchcock’s final films, was later released in 1984, mere months before Truffaut’s death.

Though Jones’s film does present a good summary of the book’s contents, it serves not just as a companion and appreciation for the book, but also as an updating and extension of it. Truffaut, famously a film critic turned film director, was at pains to use his book as a critical testament to demonstrate to the world that Hitchcock was not merely a great entertainer, but truly the greatest artist that the medium of cinema had yet seen. As a young filmmaker with a handful of films under his belt at the time of the interview, he brought an authority, a technical expertise, and a sympathetic sensibility to his questions and analysis that could only come from a fellow director. So it is fitting that Kent Jones chose to explore the subject of Hitchcock/Truffaut through the lens of interviews with great contemporary filmmakers such as Martin Scorsese, Olivier Assayas, David Fincher, and many others. Unlike the book, which primarily moves chronologically through Hitchcock’s career, the film is structured more thematically. Some of the discussion of Hitchcock’s silent pictures, for example, comes much later when discussing the elements of his visual style.

Of course, Jones includes a lot of excerpts from the taped interviews themselves, which is tantalizing for anyone who has read the book. (Apparently nearly 12 hours of the original tapes are available online!) For one thing, many of the anecdotes that elicit a smile when read are laugh-out-loud funny when heard in Hitchcock’s own voice. Another interesting thing about the recordings is hearing the voice of the interpreter. It seems plausible that her mediation significantly shaped the discourse between the two directors, especially when you see the subtitles for Truffaut’s words at slight variance with what Helen Scott is saying. In editing the dialogue for publication, Truffaut also excised some of the racier comments, or the places where Hitchcock asked to go “off the record.”

One of those areas where Hitchcock was reticent to comment was when Truffaut asked him about whether he considered himself a Catholic artist. This part is present in part in the book, but apparently Hitchcock did not want to discuss it at one point. This section of Jones’s documentary is helped by the comments of Martin Scorsese, another artist of undeniable Catholic sensibility, and an encyclopedic guide to the cinema. Hitchcock and religion is a rich area for discussion, and being able to view the scenes from The Wrong Man referenced in Truffaut’s book again in light of the comments by Scorsese and Desplechin makes me want to rewatch a film that I did not appreciate much when I saw it some years ago.

It is fun to hear the famous “all actors are cattle” line from the master’s mouth, but even better to find it in the context of a meaningful discussion of the relation of acting to filmmaking as a whole. Hitchcock’s qualities as a visual storyteller are made apparent through an anecdote about filming I Confess with “method” actor Montgomery Clift. The directors interviewed give a sympathetic and somewhat speculative appraisal of Hitchcock and his approach to character, partly spurred by fascinating (and somewhat unusually self-doubting) comments in Truffaut’s book, where Hitchcock questioned whether he should make films that explored looser narrative structures.

When the discussion turns to Vertigo, director James Gray suggested that the truest viewpoint in that film is that of Kim Novak’s character, but Hitchcock keeps our focus throughout the film on the viewpoint of Jimmy Stewart’s character. This reminded me of Nick Allen’s review, where he expressed disappointment that no female filmmakers are interviewed for his project. That is indeed an oversight, but hopefully one that will be less and less common in future films of this type.

Jones’s film lingers for a long time on Vertigo, which is widely considered Hitchcock’s (or even all of cinema’s) greatest achievement. This is again a point of departure from Truffaut’s book, which gives a seemingly cursory assessment of that film. Notorious, which Truffaut regarded as the “quintessence of Hitchcock,” and his favorite film, doesn’t receive as much attention as I would have liked. It does get an analysis of the famous long kiss scene, though, and also fittingly gets the final “word” in the documentary, visually speaking.

I think Truffaut would be proud to see this film, because the testimony of so many great filmmakers from the present confirms that his goal of getting others in the film world to appreciate the particular artistry of Hitchcock’s work was realized. And the fact that I saw this movie in the Museum of Fine Arts, a literal art-house theater, testifies that Hitchcock has taken his place as an Artist in the canon of cinema.

There was a time, described by director Paul Schrader in the documentary, when even a film like Vertigo was nearly impossible to find and view. Now we have instant access to the whole catalog of Hitchcock’s films through streaming and discs. Every DVD and Blu-ray is packed to the gills with commentaries, making-of features, and the like. But even in the midst of all that wealth of discussion, Truffaut’s book remains a vital and important document in seeking to understand Hitchcock’s work. And now this companion film by Kent Jones highlights and extends that conversation into the 21st century for more generations of moviegoers to join.