Shadow in the Cloud (2021)

The setup seems simple enough: Here's Maude: a determined young woman in a pilot's jacket, marching across a runway with a leather satchel. She climbs aboard a B-17 bomber — that oh-so-cinematic of warplanes — and insists that her package contents are classified. After the flight crew — all men — flare up predictably with with scorn and sexism, they begrudgingly accept her credentials. But they refuse her anything more than a flicker of respect. And soon, Maude's consigned to to the seat of a ball turret gunner — that spherical cell protruding beneath the plane like a barnacle on a ship.

If "ball turret gunner" sounds like a euphemism, it might as well be one: Poor Maude is subjected to a barrage of sexual harassment over her headphones to the point that we have to wonder who the real "enemies" are in this scenario. As we watch her suffer in close-up, she begins to resemble Falconetti's anguished Joan of Arc — tortured by her leering, satanic jury. Strapped into that claustrophobic's nightmare, Maude spends the first half of the movie barely able to move, which makes things seem so much worse when she is persecuted by a vicious gremlin.

What could go wrong? Will Maude be abused by her crew? Yes. Will they seek to discredit her? Yes. Will the crew become divided in their willingness to cooperate with her? Yes. Will that endanger their safety? Yes. Will the gremlin damage the plane? Yes. Will enemy planes attack them even though these bombers believe they're safely out of range? Uh-huh. Will the Mystery Box be opened against Maude's strict instructions? What do you think?

And I haven't really spoiled anything: Those are the turns you can see coming.

Okay — someone's probably still stuck on the fact that I dared mention this over-the-top action thriller in the same sentence as that most sacred of cinematic works: The Passion of Joan of Arc. Shadow in the Cloud is made in the tradition of Saturday-matinee cliffhangers that throw plausibility out the window in order to keep audience guessing and gasping, as if the theater is actually an amusement park ride. It's as ridiculous and excessive as Dreyer's art film is earnest and austere. But I stand by the comparison if only to highlight the remarkable commitment of actress Chloë Grace Moretz to the role of Maude. What makes this film unusually compelling is how Moretz brings such conviction to her performance that we want to see how she comes out of this even as the world around her poses greater and greater threats to our suspension of disbelief. If I were just describing the narrative, it would seem like one of those goofball “so-bad-it’s-good” entertainments. But Moretz makes it all worthwhile, treating this as the sort of audition that will expand the range of films she headlines in the future.

There are other things to admire here: Director Roseanne Liang and cinematographer Kit Fraser keep things compelling even during the hour that Maude's stuck in cramped quarters. Mahuia Bridgman-Cooper's synthesizers stir up good John Carpenter vibes. And when the gremlin is mysterious, a shadowy symbol of trauma, it's sufficiently creepy. (The more literal it becomes, and the more clearly we see it, the more disappointing and ridiculous it seems.) The special effects overall are just sharp enough to strike a balance between the convincing and the absurd. The sound design, while chaotic, works well to put us in mind of what the world must sometimes feel like to women forced to manage in contexts where men feel empowered to disrespect and abuse them.

One of the film's greatest strengths is that is is blessedly short — only 82 minutes. (And, frankly, the last ten minutes should have been either trimmed or reimagined, as they give the film a bumpy, cringe-inducing conclusion.) I suspect this erratic flight might lose a few viewers in its turbulence. But if you can accept that the movie isn't really interested in plausibility, and that it just wants to get audiences cheering for its persecuted heroine as she unleashes her inner Ripley — fighting misogynists, dismantling idiots, and punching gremlins in the face — well, I think you'll have fun with it.

Some of you may be wondering if this is some kind of remake. Haven't we seen a gremlin tormenting passengers and crew before? The film admits its inspirations, opening with footage from a classic animated short in which a monster haunts a warplane pilot. That concept has inspired other takes, including a well-known episode in the Steven Spielberg anthology series Amazing Stories. But this is the most elaborate version yet imagined for the screen.

The only real misgivings I have about the film stem from a name in the credits: Max Landis, who is listed as a co-writer with Liang. Landis has disgraced himself with abusive behavior towards women. And for a while I was worried that he might be trying to perform penance by making a movie about woman standing up to a gang of ugly misogynists. But it didn't take long to find details that set the record straight: Liang made this movie after rewriting whatever initial script Landis had written. I don't know how much of what we've seen came from his original draft, but I don't really care. This final product makes misogynists look wretched, and rightfully so.

Quite a few actors have given demanding performances in confined spaces — Tom Hardy in Locke, Colin Farrell in Phone Booth, Ryan Reynolds in Buried, Brie Larson in Room — making Shadow in the Cloud the latest entry in an unusual genre. But Moretz distinguishes herself impressively. While the narrative around her seems to have been designed by storytelling gremlins more interested in mischief than meaning, eager to bend everything to the breaking point, Moretz seems to be daring the screenwriters to come up with demands that she cannot handle. The farther this airplane hurtled through space, the more eager I was to see how far she was willing to go. And, almost as if she sensed me watching, Maude eventually growled at the screen "You have no idea how far I'll go!"

She was right.

Bonus: If you're riding the Kate Bush high provided by the latest season of Stranger Things, you'll love the end-credits sequence here.

Hit the Road (2022)

Are seasons still a thing? It's still July (for a few more hours anyway), but this Seattle heat wave has me yearning for autumn conditions.

Ever since I saw Panah Panahi's debut feature film, the dark road-movie comedy Hit the Road, I've imagined pulling my car off the hot Seattle streets, finding myself a patch of shade, and splaying my upper half out the window the way that the exhausted, exasperated driver Farid does in in this film. If you were to glimpse him as you drove past, you'd think that he might have been shot, or suffered heatstroke, or been attacked by carjackers who dragged him halfway out, knocked him unconscious, and then abandoned their gambit. Farid leans backward out the car window, his arms splayed as if pantomiming crucifixion, his face turned skyward. He might be praying. Or he might just be exhausted.

But Farid (Amin Simiar), the "big brother" of the road-tripping family, is feeling anxiety about more than the heat. Yes, he is driving his parents, who are difficult, and his younger brother, who is hyperactive, beneath cloudless skies on a mysterious trek to the Turkish border. So the typical stresses of being stuck in the car with a temperamental family are weighing on him. Moviegoers themselves should expect to feel a bit strained themselves by Farid's father's sullen, abrasive demeanor; his mother's spirited attempts to turn frowns upside-down; and his little brother's loudness and irrepressible energy.

But it's worse than that. The heat beating down on the car is literal enough, but it might also be a metaphor for the troubles from which Farid is running, and the daunting gamble he is about to make with his life.

I could say more, but much of the pleasure of Panahi's impressive first film is in the way we're kept guessing about what is really going on. This is Iran, and this is a movie made by the son of the great Jafar Panahi, an heroic Iranian artist who has nearly died in prison for resisting his government's cruelty and censorship and making art that challenges injustice. So we should not be surprised that the car at the center of the screen feels like a pressure cooker, and that while the comic chemistry of this anxious family may remind us of American family road-trip comedies like Little Miss Sunshine, this takes place in a much scarier world, where the wrong run-in with police could end with incarceration or even executions. (Come to think of it, many Americans do run that risk every day. So this film might be more "relatable" for some than others.)

Is Panahi the Younger thinking of his father by casting the wonderfully grouchy Hassan Madjooni as Farid's father Khosro, who has to accept his backseat position due to a broken leg, and who is further afflicted by an infected tooth? Madjooni looks at times like one of those big, hairy, cantankerous Muppets as he argues with his wife, wrestles with his flailing and flamboyant younger son, and rolls his eyes as his warnings and counsel go ignored. It would be easy just to take him as comic relief. But as the movie unfolds, we begin to sense that there is much more to this man than meets the eye, and that his troubles might be signs of sacrifices he has made for this family.

By contrast, Mother — played with radiance and affecting heartbreak by the beautiful Pantea Panahiha — is an icon of optimism, affection, and warmth for her whole family. And yet, for all of her bright smiles and songs, she cannot hide that the secret of this journey is tearing her apart inside. Watch, and you'll catch her turning away, shedding sudden tears, and then mustering the strength to turn back and brighten the weary travelers' spirits again.

And then there's the flamboyant six-year-old, played by Rayan Sarlak, who resembles the Tasmanian Devil from Looney Toons, and who will have moviegoing parents glancing at each other in sympathy as they recall their own toddlers' most hysterical behavior. He may test your patience, but I think you'll be thankful for him by the film's end. When the full details of Panahi's narrative are revealed, you'll be thankful for any source of levity.

Oh, I've almost forgotten to mention the fifth traveler — the ailing dog Jessy, who goes almost unseen for much of the movie, miserable and motionless in the rear of the vehicle. Jessy seems like a metaphor or a manifestation of — what? This family's troubles? Their hopes for their country? Their future? It's hard to say, but where dogs are usually useful as jokes in road-trip comedies (I'm particularly fond of the one in the Chevy Chase/Jon Candy classic The Great Outdoors), this one only triggers a few laughs, serving more as a sign of foreboding. There is a sense of desperation about this journey — the family has already lost their house for reasons that won't be revealed until late, so the prospect of losing any family member (even the dog) threatens to turn this comedy into a tragedy.

There are big surprises along the way, the biggest of which involve sudden catapults into fantasy. One in particular reminded me of Richard Linklater's Waking Life, in which characters philosophizing together across a patio table might suddenly morph into clouds drifting through space. This caught me off guard, as the director's style carries his father's comical take on realism forward with such confidence; I was never expecting special effects, images that play like waking dreams, or musical numbers sung to the audience. (I'll need to see it again to decide if these really "work" — they are brave choices, but they felt incongruous and discombobulating for me on this first viewing.)

But my favorite surprises come courtesy of cinematographer Amin Jafari, who occasionally pulls back for impressive long takes with the family and others appearing in the far distance, sometimes on the horizon as if figures in a shadowplay. These moments, revealing the winding line of the road zigzagging across golden hills as if uncertain about its own direction, seem to refer to masterworks by another legendary Iranian filmmaker: Abbas Kiarostami. I wouldn't have been surprised if characters from Kiarostami's Koker trilogy showed up at one of the roadside stops.

Even as you can feel governmental oppression constraining Iranian art, you have to marvel at the courage of the artists who risk their lives to bring their visions of suffering and hope to the world outside. I am sure that there are many aspects of this film — blatant and subtle — that I am missing due to my privilege: I've never walked these roads, suffered these limitations, or lived with such grim prospects. But as I sense my own country giving up its hard-won freedom to the schemes of con-men and fascists, I sense that I have much to learn from artists like the Panahis — both Senior and Junior — who suffer with eyes wide open, using what tools they have to fight the power, to tell the truth, to laugh despite their sufferings, and to hang on to hope... for future generations, if not for themselves.

In view of that, although I find its bittersweetness discomforting, and although its conclusion leaves me struggling to make sense of what I've seen, I am grateful for Hit the Road. In a year of so many excessive and almost-meaningless blockbusters, audiences need challenges like this one to remind them that art, at its best, is not just about entertainment: art afflicts the comfortable and comforts the afflicted. Art isn't just what we watch; art is what gets us talking, struggling, arguing, and asking questions. Art makes us work in order to help us grow.

And Panah Panahi is, thank goodness, a true artist who is just getting started. May God bless the hard roads ahead of him. May he find attentive audiences. May he know safety. And may he find places to pull off the road, rest in the shade, and dream his way to even greater art for a world that needs it.

Everything Everywhere All at Once (2022)

This post is dedicated to those whose contributions have significantly supported LookingCloser.org in recent years: the site's muse Laure Hittle, and executive producers Chris Angus, Benjamin Bronsink, Kimberly Fisher, Timothy Grant, Cynda Pierce, and Julie Silander. Thank you so much, my friends!

After living on a diet of Disney+ for years, film critic Cravis Frankly has returned — mostly because he's curious about Everything Everywhere All of the Time. I was happy to see him and encourage him to expand his cinematic horizons a little.

Frankly:

Why does this review look different from your usual reviews?

Overstreet:

What better way to review the year's best multi-verse movie than with multiple accounts of multiple viewings?

Frankly:

Okay, but I'm late getting to this movie because I always prioritize what the box office tells me to see. I'm a puppet you see. I go where the Mighty Hand of Marketing tells me to go. And I haven't seen much promotion for this one. But I'm curious because the Honest Trailers video for Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness praised Everything Everywhere All at Once as the far superior multiverse movie. So, tell me: Will there be spoilers?

Overstreet:

The fourth part of this post will have spoilers — I will discuss the film's controversial conclusion, as I'm seeing interpretations that trouble me. I recommend that you skip that part until you've seen the film. Much of art's power lies within its capacity to surprise us. You don't want to miss out on surprises.

Frankly:

Proceed.

FIRST VIEWING

Overstreet:

Take the title as a warning: Everything Everywhere All at Once is what you will see, hear, feel, and think about during these two hours and nineteen minutes. For audiences who need hyperactivity to stay awake and engaged at the movies, this may be hard to beat for entertainment. In The New York Times, A.O. Scott describes it as a "swirl of genre anarchy." Daniels — that's what the filmmaking team of Daniel Kwan and Daniel Scheinert call themselves — have rocketed from the audacious and discomforting comedy of Swiss Army Man to a similarly audacious and discomforting superhero extravaganza that feels like the next ten Daniels movies playing... well... all at once.

Swiss Army Man was... weird. It was like Castaway if Wilson the volleyball was replaced with the farting corpse of Harry Potter. Is this movie as weird as that one?

Overstreet:

Oh, yeah. I found Swiss Army Man off-putting abrasive — sort of show-offy in its crass brashness. Everything Everywhere has moments like that too, but the highlights outshine the more cringe-worthy moments.

Frankly:

So... what happens?

Overstreet:

Okay, buckle up. I'll try to sum this up in one big sentence.

Frankly:

May I diagram the sentence when you're finished?

Overstreet:

Be my guest. Here goes:

Evelyn (played by the great Michelle Yeoh) lives an exasperating life of multi-tasking as a wife trying to save her marriage to Waymond (Ke Huy Quan); a mother trying to save her relationship with her despairing daughter Joy (Stephanie Hsu); a laundromat manager trying to save the family business from an aggressive auditor (Jamie Lee Curtis); a daughter trying to take care of her declining father Gong Gong (James Hong); and a dreamer (a novelist, a singer, and more) trying to sustain her romantic hopes — but when she discovers that she is just one of countless Evelyns living different lives across an incomprehensibly complicated "multi-verse," she must learn to advance her multi-tasking skills exponentially in order to fight a demonic power called Jobu Tupaki, a black hole that threatens to suck all meaning from the universe, and that is rapidly corrupting her daughter.

That summary only scratches the surface of everything going on here.

Frankly:

May I change my mind and not diagram that sentence?

Overstreet:

I wouldn't blame you. Maybe one of our readers will try it. That'd be cool.

And you're telling me that the movie works, as busy as it sounds?

Overstreet:

For what it is, it works better than I would have dreamed. It's not "my kind of movie," mind you — I prefer movies that give me time to think, movies that do more "showing" than "telling," movies that prefer beauty to busy-ness. But, as fast-paced action extravaganzas go, this is pretty spectacular, and one of the best since The LEGO Movie, Mad Max: Fury Road, or Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse. It's more of a rollercoaster than a book of poetry. Actually, it's more like a whole amusement park, celebrating its influences and innovating on the Marvel movie template.

Frankly:

You don't usually enjoy CGI fests.

Overstreet:

This isn't a CGI fest. That's one of its most distinctive achievements.

I haven't even begun to talk about the Daniels' technical achievements here. The movie moves at such high speed that viewers susceptible to seizures might want to take caution. Without much at all in the way of digital animation, the Daniels fill every inch of the screen with razzle-dazzle in a way that would probably leave Edgar Wright breathless and ecstatic. Collaborating with a small team of visual effects artists working in practical media, [Daniels] have achieved a joyous spectacle as exhausting as it is constantly surprising. There's an indieWire piece by Jim Hemphill that will blow your mind if you read it after you see the film. Hemphill writes that the film's feast of effects "are even more astonishing when one watches the end credits and realizes that they were not the work of a high-end post-production facility but a handful of craftspeople...." Basically, five people are responsible for most of film's sugar-high of special effects: Zak Stoltz, Ethan Feldbau, Benjamin Brewer, Jeff Desom, and Matthew Wauhkonen. I don't think it's an exaggeration to say that there is more invention and imagination in fifteen minutes of this movie than there is in the entirety of any Marvel Universe movie I've seen.

On every other count, the film is impressive. The Son Lux score is effective, and the end-credits song by Mitski, David Byrne, André 3000, and Randy Newman — yes, you read that right — is really worth staying around for.

Frankly:

You haven't even mentioned the thing that got my attention in the first place: The return of Short Round from Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom! He's really in this movie?

Overstreet:

He is, and he's fantastic. He even gets to say and do things that are clever references to that performance from, what? Almost forty years ago!

In fact, the whole cast is uniformly fantastic — a perfect ensemble. And that's remarkable, considering the original plan was for the film to star Jackie Chan, and then was reinvented to star Michelle Yeoh and Awkwafina. The final lineup — Yeoh, Quan, Hsu, Curtis — would all be worthy of the praise "awards-caliber work," if awards meant anything. I mean, we already knew Yeoh was great, but who would ever have thought she could do this?! And I sincerely hope Jamie Lee Curtis is remembered at next year's Oscar season — unlikely, but this is the funniest, bravest performance of her career.

It sounds like you really love this movie.

Overstreet:

There's a lot to love about it. And the sensory overload of it may translate to some as greatness. It doesn't for me — not yet, anyway. I'm not sure its adds up to much more than the sum of its parts. Its weaknesses are, for me, almost as significant as its strengths. The fast-forward action scenes are inventive and fun at first, but eventually, for me, they become headache-inducing. And it has so many jokes about butt plugs and penises and S&M that the amusement devolves into a recurring groan of "Why?!" It never pauses long enough to give us a chance to think or use our own imaginations.

Some of its all-caps messaging has me cheering — and even, in more than one scene, tearing up; this is a movie with its heart in the right place, emphasizing the importance of generational flexibility, with grandparents and parents learning to expand their worldviews in the name of love, and young people learning to hang on to hope in spite of the evidence. (Turns out, the grownups who have doomed the world might not be entirely irredeemable.) Watch for a moment when Waymond quietly reveals the secret of his strategies: "This is how I fight." In that moment, he becomes as inspiring to me as any superhero I've yet seen on the big screen.

But while I can endorse much of the movie's messaging — particularly the way in which Waymond influences Evelyn's perspective — I can't admire the heavy-handedness of it. For all of its imagination, this movie's finale feels overlong and preachy. As Calum Marsh wrote on Letterboxd: "In what dimension is it remotely justifiable to have a 40-minute emotional climax?"

Frankly:

Actually, you're making it sound like a lot of my favorites. Like Endgame.

Overstreet:

How did I know you were going to say that?

Frankly:

I go where I'm expected to go.

SECOND VIEWING

Frankly:

You went back for more?

Overstreet:

I knew I would eventually give this a second go. There was too much happening "all at once" for me to feel like I'd given it a fair assessment. So, I seized an opportunity to catch a Saturday afternoon matinee, and I'm glad I did.

I decided to focus on something other than the storytelling this time, and I was able to just relax and surrender to the waves of visual creativity. I originally rated this on my Letterboxd account at "3 1/2 stars," and those ratings are off-the-cuff and insignificant — but I'm going to go ahead and bump it up to "4 stars" now. While the storytelling is more sophisticated, layered, and thoughtful than any Marvel movies but Spider-verse, I would count this film up there with some of the greatest achievements in visual effects. I didn't notice a blip of digital animation — everything is done with clever editing, lots of festive and decorative props, and convincing camera tricks.

The amount of work invested here by Yeoh, Quan, Hsu, Curtis, and Hong in so many complicated action scenes, so many costume changes, so much makeup, so many stunts — it's hard for me to fathom. There's more visual and storytelling imagination in 15 minutes of this than in the whole of Doctor Strange In the Multiverse of Madness. If Everything Everywhere this doesn't run away with the effects Oscar next year (and, let's face it, it probably won't), I'll wonder what qualifies Academy voters to vote on this matter.

Even so, it still feels too long. The Everything Bagel finale drags on interminably, and I find myself just wanting something, anything, to wrap it all up. That's why I'd still call Spider-Man: Into the Spider-verse my favorite multi-verse movie of all time.

THIRD VIEWING

Overstreet:

[Singing.] "Sucked ... into... a baaaaaagel." I think I'm going to be singing that line along with Stephanie Hsu whenever the terrible headlines of the day get me down.

Frankly:

You went back yet again. Why, if it annoys you?

Overstreet:

Almost everyone we know is still talking about it and Anne hadn't seen it yet. She's a big Doctor Who fan, so I had a feeling she'd love this. And she did.

Frankly:

Did you change your mind about anything this time around?

Overstreet:

Still too preachy; still about 15 minutes too long.

But I'm finding that it's a great one to watch at home with someone who hasn't seen it before. How many movies deliver such consistent surprises, so many unexpected delights?

Each time I've seen this, I've enjoyed Stephanie Hsu's performance more. And although the movie is already overstuffed, I would have loved to see more of Jenny Slate as Debbie the Dog Mom. I know some folks are worked up about Dierdre's character strongly resembling a pre-existing character, but I'll never stop enjoying Jamie Lee Curtis's go-for-brokeness here.

For what it's worth, Yeoh's Evelyn showed up in Anne's dreams last night, after the movie.

Frankly:

Whoa. She's entered the multi-verse!

Overstreet:

It would seem so. She said that Evelyn, in the dream, was always at a distance. Anne and I were apparently trying to catch up with her. And then we realized that Evelyn was pregnant in this dimension. So... it'll be interesting to see if that figures in a sequel. Whatever the case — I wish Evelyn and her new baby well.

Thoughts on the Film's Conclusion

Frankly:

Okay, I've seen it now. I think the movie broke my brain.

Overstreet:

You mean... broke it worse than usual?

Frankly:

You said you have thoughts about the conclusion. I'm glad to hear that, as I found one particular line troubling.

Overstreet:

Is it the moment when Evelyn embraces Joy? When she says back to her daughter the same two despairing words that she herself, at her lowest point, was saying?

Frankly:

Yes. She says, "Nothing matters." That bothered me. Doesn't that make this movie... nihilistic?

Overstreet:

It bothered me when I saw it the first time. But I've thought about this during both the second and third viewing, and... no, I don't think so. In fact, I think Evelyn is turning those words upside down.

You're not the only one worrying about this. But, contrary to what some of my friends and colleagues have called "a nihilistic conclusion," I read Evelyn's utterance of "Nothing matters" not as a surrender to meaninglessness, but as quite the opposite. I read it as a reassurance from mother to daughter that, no matter what happens, nothing can break her love for her daughter. All of the hard feelings? All of the failures? All of the misunderstandings? All of the disagreement? None of it matters — she will still love her daughter, still pursue her, still desire to be with her. That strikes me as an ideal culmination of their struggles. Evelyn decides to "fight" the way that her large-hearted husband Waymond has been fighting — prioritizing unconditional love and embrace over every argument.

If I'm wrong, and Evelyn's line is meant as a surrender to the great Everything Bagel of meaninglessness, well... yes: That would mean that all of the movie's fuss over purpose and potential and love and forgiveness implodes at the last minute. That wouldn't make any sense to me at all. That would make it one of the bleakest and most despairing films I've ever seen. The film's epilogue — "All of the Time" — doesn't feel like that to me at all.

And thank God for that.

Anyway, thanks for the conversation, Cravis! Movies aren't worth much if we don't chew on them after they've been served to us.

Frankly:

I suppose. But may I say that my movie stomach hurts?

Marcel the Shell With Shoes On (2022)

“For my next trick,” says Joseph Cornell ... “I have put the world into a box.” And when he opens the box, you see something dark and glittering, an orderly mess of shards, refuse, bits of junk and feather and butterfly wing, tokens and totems of memory, maps of exile, documentation of loss. And you say, leaning in, “The world!"

– Michael Chabon, "Wes Anderson's Worlds"

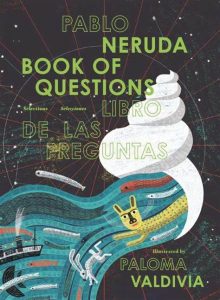

A new hardbound book stands up, cover out, the star of the show on our living room mantelpiece. It's a large picture book (you know — "for kids") illustrating seventy of the original 320 questions in Pablo Neruda's Book of Questions. A couple of favorites: "What news bursts forth from the leaves on those first days of spring?" "Why don't they teach helicopters how to draw honey from the sun?"

The childlike inquiries throughout the book — imagine a particularly creative four-year-old who doesn't want to go to sleep and so keeps asking questions — enkindle imaginations for inquisitive pre-schoolers and for adults who have sustained a childlike capacity for wonder (and for poetry). And the extraordinary art by Paloma Valdivia reminded a friend of mine of The Very Hungry Caterpillar, while it made me think of the complex, interlocking designs in Cartoon Saloon's The Secret of Kells. Every turn of the page (some of which unfold into three-panel panoramas) reveals a variety of surprises. The more you notice the purposefulness in the playfulness, the more the pages speak to you of a meaningful world.

The childlike inquiries throughout the book — imagine a particularly creative four-year-old who doesn't want to go to sleep and so keeps asking questions — enkindle imaginations for inquisitive pre-schoolers and for adults who have sustained a childlike capacity for wonder (and for poetry). And the extraordinary art by Paloma Valdivia reminded a friend of mine of The Very Hungry Caterpillar, while it made me think of the complex, interlocking designs in Cartoon Saloon's The Secret of Kells. Every turn of the page (some of which unfold into three-panel panoramas) reveals a variety of surprises. The more you notice the purposefulness in the playfulness, the more the pages speak to you of a meaningful world.

This was one of those rare occasions where Anne and I get a book from the library and, within moments of opening it, order a copy for our home library. We were absolutely dazzled by its playful shapes, its vivid colors, and its secrets which emerge if you pay attention to patterns and to the relationship between each question and each picture. It made us feel like children again discovering what would become a lifelong favorite. It felt like good medicine in hard times. It felt like relief.

One page, for example, features a camel bowing his head low to almost touch his nose to that of a tortoise. The text offers this exchange:

What's hidden under your hump? said the camel to the tortoise.

And the tortoise asked: What talks are you having with the oranges?

This immediately reminded me of a story I had once written and illustrated for my mother's birthday, in which a tortoise arrives at a birthday party, pops open his domed shell like the trunk of a car, and reveals that he is delivering the birthday cake.

I love this frame of mind whenever I find my way to it, either by the inspiration of another artist or in my own artmaking,. Such awakenings remind me that I once thought this way all the time — that these are, in fact, re-awakenings. And I liked thinking this way. I want to think this way more often. If I do, I will inevitably give it some form of expression. I want to invite the world to play with me in this way.

The same kinds of questions, the same kind of imagination, the same kind of joy emanates from the new film Marcel the Shell With Shoes On.

If A24 doesn't send this into theaters generously, they're going to lose a lot on what I believe has the makings of a cult classic. This is movie magic on the scale of The Muppet Movie, with just as much heart and just as much humor. And, in its astonishing extraordinary merging of stop animation and live action footage, it stands as one of the most remarkable achievements in animation I've ever seen.

Expanding on a series of short stop-animation videos that they began making and posting on YouTube back in 2010, filmmaker Dean Fleischer-Camp and actor Jenny Slate give their irresistibly charming character Marcel — a tiny, one-googly-eyed seashell who toddles around on little pink shoes and monologues without ceasing — his first feature-length adventure. And that's really all you need to know: Marcel asks questions as ebulliently as a four-year-old. And that's just the beginning of his childlike creativity: He also rigs up all kinds of inventive Rube Goldberg contraptions around the house for purposes of work and play, and often comes up with observations that resonate with wisdom. Every scene has a surprise that jabs a laugh from the audience, but there's also a layering of subtle visual humor that will reward those who come back to pay closer attention. All of this sustains the characteristics of Marcel that Dana Stevens described (in Slate, no relation to Jenny) as the charm of those original videos: "Marcel possessed a distinctly uncorny optimism founded on admirable self-love. Marcel did not want to sell you a product or a dream; he just wanted to tell you about what he liked and share his world."

While the movie unfolds effortlessly, as if Fleischer-Camp really did just turn on a camera to document the life of his new roommate, there's a lot more going on here than there was in the viral videos.

First, there's a more ambitious look at Marcel himself, his history, and his environment. And moviegoers don't need to see the earlier material — this film works perfectly as an introduction. As usual, he's voiced by Jenny Slate (Zootopia, The Obvious Child), in the most perfect match of character and and actor since Jim Henson as Kermit the Frog: He sounds a bit like a three-year-old boy coming down with a cold — and yet there's an irrepressible joy in that voice even when he's expressing his deep sadness or melancholy. There's a squeaky edge to his chatterbox style, but I have yet to hear from anyone who finds him annoying.

As Marcel tries to comprehend why anyone would make a movie about him, he finds himself explaining to others that a documentary is "like a movie but nobody has any lines and nobody even knows what it is while they're making it." It's funny because it's true. But it's also fitting because the filmmakers weren't working with a detailed screenplay. Much of the dialogue was improvised. It's a remarkable thing to imagine: The filmmakers had to align Slate's improv with the excruciatingly slow art of stop animation, and that they succeeded in a way that suspends our disbelief is nothing short of genius-level artistry.

To infuse all of this with such love and such conscience, well — that reminds me of a filmmaker I rarely ever mention when describing great filmmakers. Marcel is the kind of film that I suspect Jim Henson would have loved: It's childlike, playful, hopeful and wise — and all of this without ever stooping to sentimentality. Its characters seem to have been brought to life with patience, attention, and love. Whether Marcel is navigating the house by steering his tennis ball "rover" down the stairs, climbing the walls with the help of honey on the soles of his shoes, zip-lining in an old sneaker, or sleeping on a soft slice of bread, walking his "dog" (a piece of lint on a leash), or just wondering about the wide world beyond his AirBnB, he's always exactly right — a fully realized character.

Then there's "Nana" Connie, Marcel's grandmother, who invests her time in mini-gardening and in offering healthcare to injured neighbors. Voiced with exquisite tenderness and wisdom by Isabella Rossellini, Nana is immediately one of the great big-screen grandmas. If you're very, very lucky, she'll remind you of your own. She's also proof that cartoon characters do not need to be wacky and flamboyant — she's an endearingly soft-touch character, a voice of unhurried wisdom.

Plot? There are a few threads weaving in and out of one another until they all merge for a surprisingly satisfying conclusion (one that involves no villains, and relies on no violence whatsoever). There's the fact that Marcel and and his grandmother were separated from their community in a sudden calamity, leaving them deeply scarred with loss. There's the sacred ritual: Marcel and Connie faithfully attend to every episode of 60 Minutes, with Marcel asking Nana to "make the noise" of the shoe's ticking-clock motif. (They stan reporter Leslie Stahl, a detail that may seem arbitrary at first, but it feels like inspiration by the end of the film.)

A cast of supporting characters make their own marks, like some spiders who watch Marcel's life as if he's their favorite show, or the honeybee drunk on honey who has trouble understanding windows. There's the fact that Dean himself — yes, the filmmaker — is in the AirBnb because his life's been overturned by a breakup (interesting, since he and Slate broke up before they made this film together). When Marcel becomes an internet sensation — yes, the film weaves in the true-life details of the shell going viral — new possibilities open up for him to make meaningful connections, but new troubles develop as well (like selfie-hungry fans showing up on the lawn). And then there's the fact that Nana Connie is getting older, which makes Marcel's loneliness and vulnerability seem that much more worrisome.

The ways in which Marcel and Nana Connie make the most of their isolation should seem inspiring to audiences who endured the COVID lockdowns, and especially those creative viewers who have felt separated from essential communities and audiences. I wouldn't call it a lockdown movie, but it feels like just the right movie for right now. Marcel declares, in what will probably become one of the most quoted lines by critics and fans, "I want to have a good life and to stay alive, and not just survive but have a good life.”

And while the film's makeshift narrative seems to have been improvised into being — unpredictable, meandering, and refreshingly unhurried — when it arrives at its stirring conclusion it seems as if every moment along the way was necessary, every scene important in contributing to its perfection. And as the credits roll, I find myself looking around in vain for a movie that it even vaguely resembles. Marcel the Shell With Shoes On is an almost unclassifiable film: It's not exactly for kids, but kids will love it. It's not exactly a mockumentary, but it plays with documentary conventions. Neither comedy nor drama seem sufficient. It works as "a coming-of-age movie" as well as anything else. We are witnessing a formative season in a child's life: Marcel's heart swells with so much love that when much of what he loves is taken, he has a hollowness inside where we hear a spacious roar, wave upon wave of longing and grief.

Pondering Marcel's pain, I'm reminded of Michael Chabon's New Yorker reflections on the films of Wes Anderson. There, he writes,

The world is so big, so complicated, so replete with marvels and surprises that it takes years for most people to begin to notice that it is, also, irretrievably broken. We call this period of research “childhood.”

There follows a program of renewed inquiry, often involuntary, into the nature and effects of mortality, entropy, heartbreak, violence, failure, cowardice, duplicity, cruelty, and grief; the researcher learns their histories, and their bitter lessons, by heart. Along the way, he or she discovers that the world has been broken for as long as anyone can remember, and struggles to reconcile this fact with the ache of cosmic nostalgia that arises, from time to time, in the researcher’s heart: an intimation of vanished glory, of lost wholeness, a memory of the world unbroken. We call the moment at which this ache first arises “adolescence.” The feeling haunts people all their lives.

Anderson observes that some "hunker down atop the local pile of ruins" and merely "make do." Others react more aggressively, contributing to the brokenness like kids "running through piles of leaves." But some strive in answer to "a vague yet irresistible notion that perhaps something might be done about putting the thing back together again."

While Chabon is thinking about Anderson's young protagonists in films like Moonrise Kingdom, he might as well be describing Marcel. As if the filmmakers envisioned a sort of Wings of Desire for kids, the first part of the film (maybe half) focuses on getting to know how Marcel and Nana Connie live, how they see the world, what they're capable of doing there, what they love. Then we spend the second half leaning into the longing, watching them take action with increasing urgency, participating in their striving to do something about that "vanished glory," that "lost wholeness." Marcel might just retreat into the hollowness of his shell. But, with coaching from his grandmother, he is not content to just "make do." He and Nana make the most of their circumstances, make a new world in the crater of the old one — and then, they lean into the possibility of restoration, risking further heartbreak in pursuit of the dream of reconciliation.

Marcel the Shell With Shoes On shines with a particular soulfulness — at least for now — because it is as yet unconnected with any obvious marketing empire. It doesn't appear to have franchise aspirations (although I would be first in line for a sequel). And there's no apparent tidal wave of Marcel merch coming our way. If you catch a few clips in commercials, you might reasonably worry that a feature-length film of this stuff is too sticky-sweet. But I'm hypersensitive to sentimentality, and I think this is one of the most beautiful films of 2022. As Dana Stevens writes, "The script is almost diaphanous in its spareness, yet these minimally animated assemblages ... convey an enormous complexity of feeling."

I suspect Marcel will become a favorite for those children and adults alike who make time for it. It's already one of mine. Like the original Muppet Movie, the first LEGO Movie, Miyazaki's My Neighbor Totoro, and Toy Story, it's an original in which the storytelling is as strong as the style. At times, it even reminds me of Finding Nemo, my favorite Pixar film, for how its aesthetic beauty leaves me with the feeling that I've just awakened from a dream. Marcel's world is an immersive environment that makes us more fully appreciate our own.

Just as I have learned more from Kermit the Frog about living a meaningful life than I have from most movie characters, I'm adopting Marcel as a mentor during dark times. I am accepting the challenge of Fleischer-Camp, Slate, and the poet Pablo Neruda. If I live in the pursuit of wonders as Marcel does, I will be less likely to retreat into my shell. He makes me want to embrace my own diminutive stature in the world, because in doing so I realize — or, better, remember — how vast the world of possibility really is. And, in spite of everything, how grateful I am to be a part of it.

Emergency (2022)

Full disclosure: The credits for the Sundance-award-winning Emergency include the name of a dear friend of mine. Her good work is earning her opportunities to work on many impressive films and television series, so I've been looking forward to this one. I don't believe that the involvement of friends of mine in film productions has ever swayed my opinion of the films themselves; my reviews of those films have sometimes made things... awkward between us. But that's the cost of integrity. So here we go.

If you were anything like me when you were a kid, you probably loved to read and re-read Alexander and the Terrible, Horrible, No Good, Very Bad Day. I suspect that's where my love for what I'll call calamity comedy (calamedy?) began — movies like Martin Scorsese's After Hours or the Coen Brothers' The Big Lebowski, films that begin with something unfortunate or unfair happening to the protagonist, and then one problem on top of another takes everything from bad to so much worse. We laugh because we know the feeling. We've had days like that. It's likely we've had years like that. That's what makes the book's refrain "I think I'll move to Australia" funny. Who among us hasn't wanted to pack up and move out of our own troubles?

But in America right now, it seems we're trapped in a terrible, horrible, no good, very bad decade, and the troubles keep coming. It's hard to laugh about them without feeling cynical or, worse, hard-hearted.

Emergency has all the makings of a great calamity comedy. I mean, what would you do if you and your best friend were college students who found an unconscious girl on your living room floor, limp as a noodle, reeking of booze, and face-down in a pool of her own vomit? Would you call 9-1-1? Would you carry her to your car and get her to a hospital?

The answer might seem easy for you, reader... if you're white. But our two panicking protagonists are black. It's the unconscious girl, who might in fact be dying, who is white. See the problem? Calling the cops doesn't sound like such a good idea. Taking her to the hospital — that sounds risky too. Anywhere cameras can catch them will make things look bad for everybody. And driving her to one of that night's big parties and laying her down on the lawn? Absolutely not.

Perhaps you're thinking that this doesn't sound like a very comical situation. You're right. It isn't.

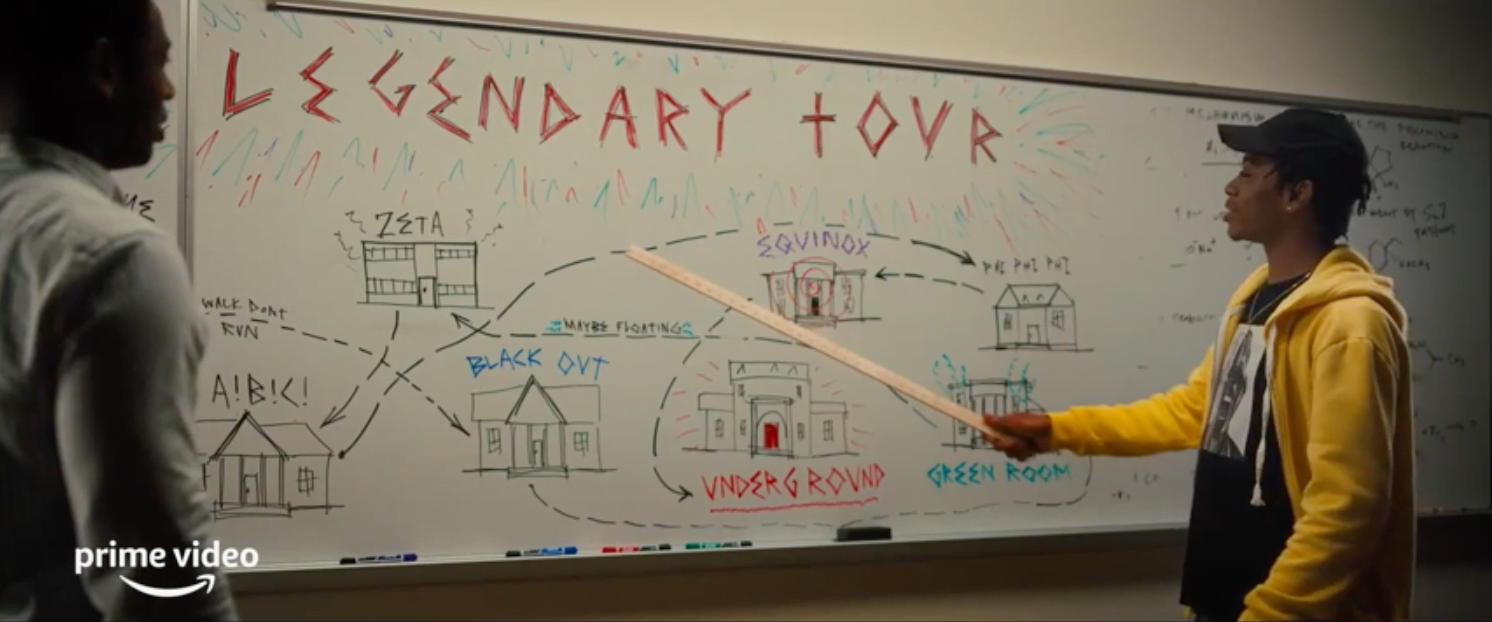

The last time we followed a bunch of guys from drinking party to drinking party, it was Edgar Wright's The World's End, and their mishaps increased until they found themselves trying to survive in a dystopian world after aliens blew up civilization. This time, the stakes are so much more believable and, thus, more sobering. Kunle (Donald Elise Watkins) is a wiz-kid biology student with a bright future, and we don't want him to stumble onto the wrong side of the law and blow his big opportunities. But Kunle's mischievous friend Sean (RJ Cyler) wants him to gamble it all to complete something known as "The Legendary Tour," hitting a marathon of parties in one night. And then there's the perpetually stoned Carlos (Sebastian Chacon), a buffoon who they hope to avoid — and so, of course, against their best efforts, he ends up tagging along.

So, at first glance, no — this doesn't sound funny. The stakes are too high.

And yet, while the crisis is so plausible and the stakes so high that we feel meaningful suspense, the filmmakers find plausible humor within these volatile friendships as they careen from mishaps that range from "terrible" to "horrible" to "no good" to "very bad." We aren't laughing at the gravity of the situation; we're laughing in recognition at the absurdity of how hard it is to — yes, in honor of Spike Lee, whose influence on the filmmakers is obvious, I'll say it — do the right thing. As these three amigos try to figure out who the unconscious Emma (Maddie Nichols) really is, how to save her life, and how to get her back where she belongs, they are prone to making the worst decisions with the best intentions, and their goofy camaraderie inspires laughs that break up the tension without ever minimizing the seriousness of the crisis.

As if that isn't enough for us to track, the filmmakers skillfully braid the young mens' adventures with another storyline about Emma's sister Maddy (Sabrina Carpenter) trying to track her down with help from her more level-headed friend Alice (Madison Thompson), Alice's new flame Rafael (Diego Abraham), and the power of Apple's phone-tracker. These three are almost as funny and endearing together as Emma's anxious would-be rescuers.

Perhaps the sense that there's something new, fresh, and authentic about Emergency comes from the rare combination of an African American director — Carey Williams, impressive with his debut feature — directing a screenplay by a Mexican-American woman: K.D. Dávila. That shouldn't be a big deal in 2022, but it is. And I hope they work together again. Williams and Dávila cook up engaging chemistry between colorful characters, zigzagging between plot threads efficiently; every character matters, every twist makes pretty good sense

Matt Zoller Seitz at RogerEbert.com is right on when he highlights one of the movie's strong points:

The best thing about Emergency is its willingness to let a scene breathe and play out at length—a rare quality in an era in which entire movies are edited like trailers for themselves, as if terrified that if they take the foot off the gas for even an instant, stimulus-craving audiences will announce that they're bored and quit watching. There are a solid half-dozen scenes built around characters talking to each other that could be self-contained, perfectly shaped short films if you lifted them out of their context.

It works until it doesn't. There is so much caper potential here. But as it has become daily news to hear about racism rampant in police departments and the shoot-to-kill/ask-no-questions habits across America, the film cannot help but struggle to balance all that it has on its mind. And the more the storylines spiral downward toward an inevitable convergence that we know is probably going to involve law enforcement, the more we can feel the genre needle tipping toward Timely & Relevant Drama (think The Hate U Give, which also featured Carpenter) and away from either Calamity Comedy (like Booksmart) or Horror (like Get Out). That's not a failure — these open wounds of injustice deserve close attention. The high-tension crescendo works pretty well, thanks to some predictably presumptuous cops. But as the film's fun-house mirror stabilizes and confronts us with a soberingly familiar reflection of America in 2022, it becomes heavy-handed. And it never really successfully recovers. Comedy is a declaration of hope for order in the face of disorder. And the disorder we see in extreme close-up here, well... who among us see much hope for repairing it?

After that, the film stumbles in search of a resonant way to wrap things up. The multi-stage epilogue tries several ways to make us laugh and several ways to make us cry. But it's trying too hard. Even Cyler, good as he is, can't wring any genuine pathos out of these scenes.

The actors are all strong, but it's a problem that Cyler (who also starred in The Harder They Fall) is such a born movie star — he owns the scene whenever he's onscreen, and shines so bright next to Watkins' Kunle that the imbalance is distracting. Similarly, Sabrina Carpenter who plays Maddy really sells us on her substance-amplified panic as she tries to track down her missing sister. The rest of the cast don't have the charisma to keep up.

But these are quibbles. There's a remarkable cleverness to the writing throughout. I'm particularly fond of how Kunle, terrified that he might have spoiled his research project back at the lab by leaving a fridge door open, says over and over again "I just wanna check my cultures.” That ongoing refrain might be hinting at any of the film's myriad levels of social commentary.

Though this feels like a "first film" for almost everyone involved, there's a current of truth and sincerity running through it — the pulse of a heavy heart. In its best moments, Emergency makes us think about the dilemmas that young black men in America must frequently face. What do you do if you need to call the cops but you know that the cops might end up being an even greater danger than whatever is driving you to call them? The movie doesn't claim to know the answer. I don't know either.

And somehow, I don't think moving to Australia is the answer.

Crimes of the Future (2022)

Film studios have repurposed so many old toys, old video games, old amusement park rides — so many products in hopes of capitalizing on moviegoer nostalgia. They've even gone to the board game closet. (Remember Battleship?) I'm surprised we haven't had to suffer Operation: The Movie yet. (I'm sure that screenplays for this must exist!)

Don't get me wrong: I don't mean to be cynical. I scoffed at the idea of The LEGO Movie once, and when it finally arrived, it turned out to be an instant animated classic.

But Operation? Could something so ridiculous actually work? It would take a steady hand.

I nominate director David Cronenberg.

In fact, if you re-introduced Cronenberg's latest sci-fi shenanigans — a film called Crimes of the Future — and slapped the title Operation on it, that would work! Most of the tension in Crimes of the Future comes from watching futuristic surgeons poke and probe a patient's innards, pull particular organs out into the light, and try to avoid errors.

Think about it: This is right in Cronenberg's greasy wheelhouse, right? He's made a career of drawing attention to our bodies — how fragile they are, how uncontrollable, how troubled and troubling. And in doing so, he's investigated the troubled and troubling impulses that compel those bodies. Think of The Brood, The Fly, and Crash. Consider my two personal favorites: eXistenz and A History of Violence. He's a composer who plays variations on themes, but only after he's opened up his organic pianos and experimented with their architecture. He shakes up our certainties, blurring the definitions of things we'd hope are fixed. And in doing so, he holds up a troubling funhouse mirror to misdeeds human beings already commit.

Let's carefully withdraw some of the internal treasures of Crimes of the Future and see if they enlighten us.

Moviegoers know how normal it has become to share the personal in public — selfies, pictures of food we're about to eat, and other social media exhibitionism are as common as commercials now. So it's easy to assume that we will take this openness to new and unforeseen extremes.

That's the premise here: In a future not far out of reach or the realm of possibility, it turns out human beings, having found ways to make pain and infection a thing of the past, are now literally baring their hearts and spilling their guts onstage, surrounded by cameras. They've turned surgical procedures between consenting surgeons and patients into public performance art.

And then, in a twist that could only have come from Cronenberg himself, the patients are conscious during surgery. It is on one of these celebrity surgery tours that we meet our main characters. Patient Zero is Saul Tenser — played with conviction by Viggo Mortensen. Tenser might make audiences tenser, but he seems surprisingly zen himself when it comes to being dismembered in the spotlight. You might even say it's his purpose in life, as he suffers a disease called Accelerated Evolution Syndrome, which busies him with the work of birthing new organs into existence. His surgeon isn't trying to cure him; she's more like a celebrity of archaeology or geology, digging up natural wonders on camera.

These surgeries on Saul's morphing form are performed by his partner Caprice (Lea Seydoux, at her gentle best). There are a lot of close-ups of incisions, of Caprice (and others) rooting around in Saul's insides as if looking for a toy in a Cracker Jack box, or a lost LEGO at the bottom of a ball pit. This is done with a mix of reverence and whimsy, which makes Caprice's name seem all the more apt. (The term caprice can refer to impulsive action. It's also a form of the term cappricio, which refers to artwork that represents a mix of real and imagined aspects.)

And there are "treasures" inside of him, at least according to Caprice and the attentive audiences as these performances: That’s the biggest idea of all in this challenge to our suspension of disbelief. In the future, Saul's Accelerated Evolution Syndrome isn't viewed as a disorder but as innovation. He's growing new organs that might adapt, expand, and evolve what a human being can be.

If you're not squirming yet, you probably should be. This movie will probably make you uncomfortable. You’ll see dripping bits of innards removed and held up to the light by awestruck scientists just the way David Attenborough might lift up a never-before-seen species of frog that can heal itself. If that makes you squeamish, steer clear.

But on the other hand, the film isn't gory in the sense of gushing blood or sudden violence. Fear not. Or, well... fear a little less, anyway. It’s all very clinical. This is no glorification of body alteration. Nor is it "torture porn" — not in the familiar sense, anyway. Cronenberg may take us to troubling places, but he always does so in order to explore important questions. In Cronenberg on Cronenberg, he says, "I think of horror films as art, as films of confrontation. Films that make you confront aspects of your own life that are difficult to face."*

Images of Saul on the operating table, or having his body manipulated by the skeletal arms of a robotic chair so that he can successfully swallow and digest his food, are more challenging than gross. They confront us with questions about Saul's character: Is he a genius, a madman, a holy fool, a martyr for a good cause, an abomination, or all of the above? Cinematographer Douglas Koch (who filmed I've Heard the Mermaids Singing way back in 1987) often frames Mortensen in Falconetti-esque closeups, so we see him "suffering" in states of near-sexual ecstasy as his body goes to "work" on new inventions.

And for all of its biological curiosity, Cronenberg's film remains far more intently focused on philosophical inquiries.

Crimes opens with a horrifying vision that will set our minds on crimes of the recent past and present. We see a young boy named Breckan (Sozos Sotiris) picking at flotsam on the shore, with an overturned ship (a reminder, perhaps, of the Costa Concordia or other ocean-wrecking disasters) as a backdrop. Breckan isn't looking for fish. He has a sort of amplified case of pica — he doesn't just chew on plastic; he's ravenous to eat it. So we're immediately prompted to view how our technological advances have corrupted our environment, and how our environment is corrupting us.

What's even scarier is that this boy is unwittingly connected to a conspiracy that wants to embrace the corruption, wants human beings to hunger for what is toxic. Breckan's mother (Lihi Kornowski) condemns him as an abomination, knowing that his father (Scott Speedman) may have ties to extremists who are trying to turn the human body into a natural recycling plant for synthetic substances.

But Cronenberg has more than pollution and the genetic disruption of our groceries on his mind. He's thinking about other kinds of appetites, including our hunger for entertainment and art.

Crimes of the Future investigates about the mysterious and personal nature of art: where it comes from, how it asks artists to expose themselves in costly ways, how commercial and corporate interests corrupt it, and how crowd-pleasing can run counter to an artist’s own visions. It dares to confront us with a messy, bodily manifestation of what artists are doing as they wrestle questions into art, as they fight with troubles to produce new pearls of wisdom. I can't help but wonder if Cronenberg wasn't thinking of Rumi, who wrote (in his three-volume work of mystical poetry Masnavi), "New organs of perception come into being as a result of necessity. Therefore, O man, increase your necessity, so that you may increase your perception." In having his torso literally unzipped, Saul is making himself frightfully vulnerable, putting himself at the mercy of his muses. And, in such a state of necessity and "openness," he is able to receive new revelations and, in a sense, give birth to them and release them into the world for better or worse.

What some critics seem to be missing is that the film’s regular adoption and repurposing of common artist-speak to this context of exhibitionist surgeons and exhibitionist patients is not only clever — it’s often hilarious. I laughed out loud several times over the course of this moody, shadowy exploration, and the fact that nobody else was laughing made me wonder if artists aren't the movie’s intended audience — those who wrestle with questions common to these agents of dismemberment. "Be open with me," one lover pleads with another, referring to a very literal openness. "I want to know what we’re getting into," says another, not far from the operating table.

Much of the film's comic cleverness comes from its outstanding ensemble cast. If you can stomach (I’m sorry) the onscreen entrails, you will be treated to one of Mortenson’s finest performances, Seydoux’s loveliest and gentlest work yet, and — perhaps best of all — Kristen Stewart’s inspired comic turn. Stewart plays Timlin, a surgery-geek fangirl. As the observant Sarah Welch-Larson has already noted, Stewart's performance DNA carries traces of Peter Lorre. Timlin whispers mischievously to Saul that "Surgery is the new sex," but when she later comes on to him the old-fashioned way, he responds, "I’m not very good at the old sex.”

Timlin's just one of a large cast of supporting characters, all of them messing with ethical boundaries. This doesn't bother me, as the film feels playful, almost improvisational, a jaunt through a Curiosity Shoppe of Cronenberg Horrors rather than a seamless tapestry of storylines.

I was particularly delighted to see indie filmmaker and actor Don McKellar show up in an important supporting role. There's something to this: McKellar starred in Atom Egoyan's 1994 film Exotica, another unpredictable film set in a strange underworld. In that film, he played Thomas, a secretive and eccentric entrepreneur who, under the cover of a legitimate pet store, was illegally importing and selling rare bird species. There's something intuitive about casting him here as Wippet, Timlin's partner at the National Organ Registry, a sort of startup branch of government that investigates and catalogues organs and their functions the way the Internet Movie Database catalogues movies.

Wippet's here to expose some of the ways in which capitalism can corrode artistic vision; to show how narrow-mindedness can prevent artists from new discoveries; and then to question just how "healthy" it is to incubate such perverse visions. These are matters that I, as a fantasy writer, find close to my heart. They inspire me to reexamine what I'm doing when I write, and — perhaps more importantly — why I'm doing it. So maybe I'm one of the few who will feel satisfied with what they're served here.

All of this is elevated by a rich score from the great Howard Shore (yes, that Howard Shore, who bears more responsibility for the gravitas of Peter Jackson's Middle-earth movies than he gets credit for).

Those who take Crimes of the Future too seriously will probably be frustrated with it. It's a whimsical meditation, not a culture-war argument. Its characters exist to cultivate questions, not to inspire fans and sequels. Those who expect a typical narrative arc that culminates in an adrenalin-rush finale will wonder if there’s been a mistake and the projectionist skipped the final reel. (Wow… there’s some film vocabulary that doesn’t make sense anymore!) But Cronenberg isn't here to play to expectations. He's always been comfortable with, even aggressively curious about, ambiguity. It's a fearless and unsettlingly honest investigation of the same question that drove the first Jurassic Park movie: What happens when human beings let ambitions get ahead of conscience?

And, almost as if there's something in the air, Crimes arrives at the same time as Kogonada's extraordinary (and extraordinarily soft-spoken) futuristic sci-fi vision After Yang, another film in which characters "break open" the "core" of an experimental human. Both films provide gentler, more thoughtful ways of confronting audiences with the implications of technological advances, avoiding the flagrant alarmism of so many dystopian visions. They just might make us more content with the flawed bodies we have, less eager to meddle with what we've been given.

I emerged from this film laughing about the possibility of a new Crimes of the Future edition of Operation. Imagine a version of that beloved childhood game in which you have no idea what your tweezers will withdraw from that poor clown's bodily cavities. You might find yourself wondering about the movie's final moments: whether they represent someone "winning" at the game, or if someone has bumped the electric boundary and set off an alarm. Typically, that's been seen as an error, a failure, a loss. But perhaps there's a scarier possibility: What if we make ourselves believe that transgression is a virtue?

*Note:

I failed to cite Cronenberg properly in my 2007 book Through a Screen Darkly, so I'm correcting that error here: Cronenberg's words come from Chapter 4 of Cronenberg on Cronenberg.

Maverick (2022) (Part Two)

[Before you read Part Two, which focuses on Top Gun: Maverick, you'll probably want to read Part One — a quick overview of my history with Top Gun.]

Comments on this review are closed. If you want to know why, read the note at the end of this post.

More than 30 years since his heroic 1986 hi-jinx, Captain Pete "Maverick" Mitchell hasn't matured much at all.

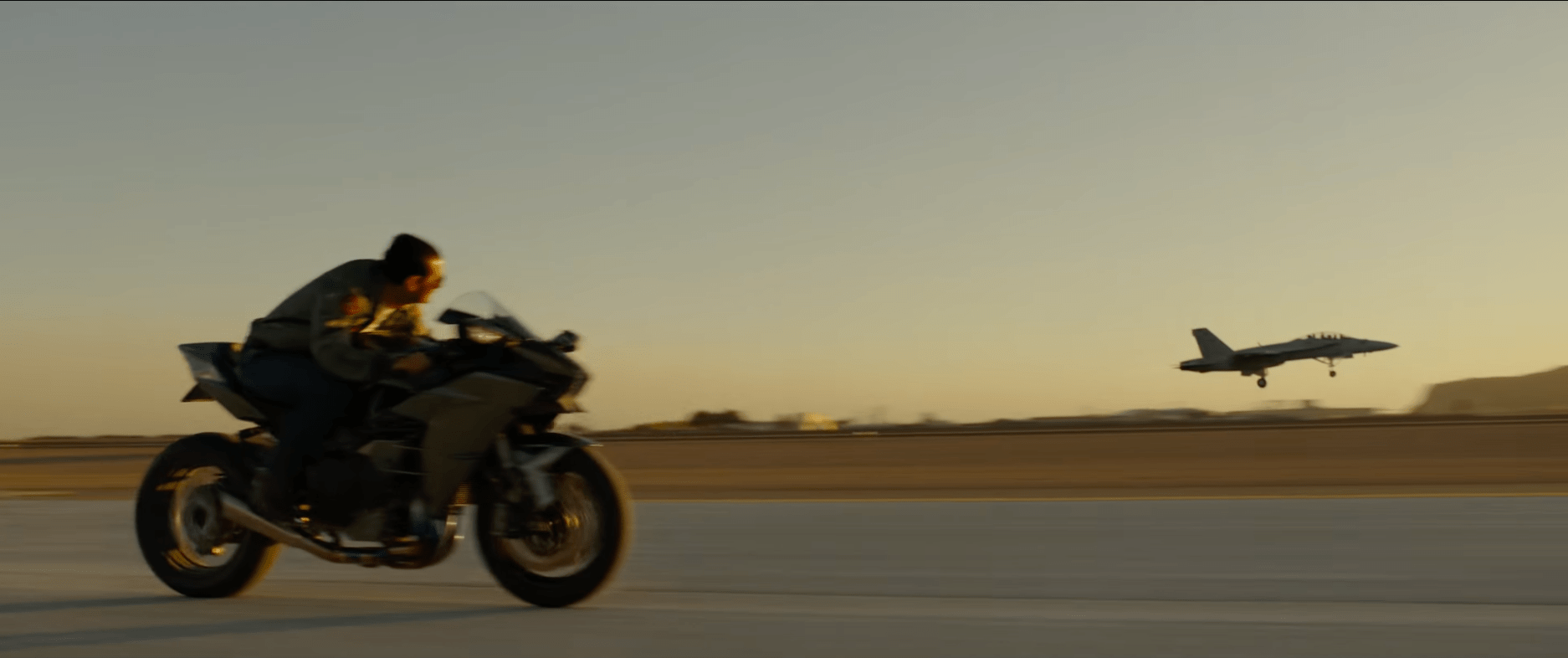

He lives in a man cave — scratch that: Mav cave — that is a museum to his own glory days: the motorcycle! The aviators! The jacket and its boy-scout badges! It's as if Mav is a Marvel superhero who has been waiting for an upgraded costume and upgraded accessories, waiting more than 30 years for a sequel.

The fact that Cruise still looks 20 years younger than he is helps to make this illusion convincing.

Anyway, Mav's still working for the U.S.A. — this time as a test pilot flying cutting edge stealth planes. And, surprise! He can't be bothered with things like restrictions. So he's working with a team that gets predictably nervous about his predictably boundary-pushing behavior. When Rear Admiral Chester "Hammer" Cain (played by Ed Harris, cast for gravitas that will make up for auto-generated lines) shows up (predictably) to shut down the hypersonic "Darkstar" program, declaring drones the way of the future, Mav (again, predictably) takes it personally.

So he reacts by living up to his name, testing Admiral Cain's temper and pushing himself to a point of calamity. He'll endanger the lives and cost the U.S. military extraordinary amounts of money, knowing that he has nothing to fear more than a lecture from a superior officer. (This sequence culminates with an amusing visual punchline that may remind you of the moments after Indiana Jones "nuked the fridge.")

During that shocking revelation of Mav's lasting immaturity and egomania, we see — and not for the last time — women and people of color standing around in wide-eyed adulation at the ascendant Ageless White Man, while other, lesser white guys look on in solemn envy.

As my friend Jack Jamieson quipped on Letterboxd, "Maybe Scientology works?" He's kidding, of course — but one can't help but wonder if Cruise and Company don't see this as a major marketing campaign. Even my friend Steven D. Greydanus, in his rave review at The Catholic World Report, says this of Cruise: "As hard as he’s worked over the last dozen years or so (oh, how hard he’s worked!) to win his way back into viewers’ good graces, the sense of weirdness around his personal life (including but not limited to his strong identification with Scientology and a series of media disasters) lingers."

After the necessary verbal rebuke, Mav's "misbehaviors" are all dismissed. It's clear that even the Admiral understands Mav's status as Man-God (Mav-God?), and thus he is beyond reproach. In fact, he is consequentially promoted, sent right back to the place he's been yearning for: Top Gun. (Shocker!) He's been summoned by Admiral Tom "Iceman" Kazansky (Val Kilmer), who is now the commander of the U.S. Pacific Fleet, and seems eager to use his power to glorify God (that is, Mav).

When he arrives at NAS North Island, Mav's ego takes an initial hit when he realizes they aren't asking him to fly into enemy territory, but rather to be an instructor for top pilots who will fly the mission themselves. For a moment, I was really intrigued: Perhaps Top Gun: Maverick would take us in an unexpected and meaningful direction! Perhaps this would be a story about learning to accept one's age, and about humbling oneself to discover the rich rewards of teaching!

With respect to another big summer movie on the horizon... Nope.

Mav will, of course, end up flying the mission himself, with his students as his wingmen: the best pilots of F/A-18E/F Super Hornets pilots who are overseen by Vice Admiral Beau "Cyclone" Simpson and Rear Admiral Solomon "Warlock" Bates.

Oh, I'm sorry — I meant wing-people. There's a female pilot here — which shouldn't even merit a mention in 2022, but I bring her up because the film is still so far behind the times that she's subjected to being the punchline of a joke about being, yes, "a wingman." (Sigh.) Okay. I guess the film's target audience might still think that's funny.

This team's task is urgent and incredibly dangerous. A foreign country (we can't know who it is or, you know, we'd actually have to think about the situation and consider America's rapidly deteriorating role on the global stage) is enriching uranium in a depression surrounded by steep mountains. Pilots will have to sneak in by flying just a few feet above the ground to escape radar detection, and then they'll have to fly out by veering up and over a high ridge, moving at high speed to elevations unfit for human life. And, of course, there are missiles and even more advanced aircraft ready to take them out — that's how video games work.

But here's the sticking point: During their desperate run through the crater, the American pilots have to bomb a specific target. The approach will not be easy. The target area is only two meters wide. It's a small thermal exhaust port, right below the main port. The shaft leads directly to the reactor system. A precise hit will start a chain reaction which should destroy the station. Only a precise hit will set off a chain reaction. The shaft is ray-shielded, so they'll have to use photon torpedoes.*

Wait — forgive me! I lost my mind for a moment there. Those last several lines are actually drawn directly from 1977's Star Wars. The mission just seems so familiar, I guess my brain switched tracks mid-review! Bear with me.

The training is rushed, tense, and complicated by two of the pilots: one, Lieutenant Jake "Hangman" Seresin (Glen Powell) and Lieutenant Bradley "Rooster" Bradshaw (Miles Teller), who look poised to take over if Cruise doesn't return to the franchise. Hangman has that devil-may-care smirk that is mandatory for a cocky hero, and Rooster... well, he's capable of resembling Anthony Edwards's Goose from the first film, which is appropriate since he is, of course, Goose's son. One of the film's central tensions flares up when Maverick and Rooster clash — but Rooster isn't holding a grudge over Goose's death in the first film, as you might expect; it's over something much more bureaucratic and uninteresting than that. Never mind.

You can pretty much guess where it goes from here: Mav aggravates the Powers That Be. The deadline gets moved up. The mission is run when the crew doesn't seem ready. And, yes, Mav will have to be heroic.

That leads to one of the film's true highlights: a venture into unexplored narrative territory, as a rescue mission requires characters to take actions that have no parallel in the first film. I won't spoil them for you. But for the first time, in its final 40 minutes, the movie surprised me. It surprised me with a tangential adventure I hadn't seen coming.

Still, one of the two most promising opportunities that Top Gun: Maverick has to demonstrate wisdom comes in the development of Mav's new love interest, Penny Benjamin. Penny's played by Jennifer Connelly, another icon of '80s fantasy films — Labyrinth most notably. (When Connelly first appears onscreen as a bartender, there's a David Bowie song playing in the background, and I had to applaud the cleverness of that. It's my favorite moment in the whole movie.) If anybody has a good chance to teach Mav something about growing up, it's Penny. She has history with Mav and should be able to speak to him about his weaknesses in ways that he will hear. By devoting more attention to her character, background, and context than anyone else in either movie, they surprised me by making her interesting. So, does she matter much in the end? Does she stand alone as an individual, presenting us with another vision for what matters?

Again... nope! Penny only ends up throwing fuel on the fires of Mav's ambitions, independence, and wish-fulfillment endeavors. She's there to give him a second chance, to invite him into her bedsheets, and to show up as a trophy at the end of the film in a supermodel pose — I am not making this up — leaning on a shiny Porsche as if he's won the grand prize on The Price is Right. I am not making this up. If the rest of the film had been crafted as satire, I would have laughed even harder than I did at this moment.

The second most promising aspect is a creative re-introduction of Mav's former rival: Iceman. If you were one of the few who watched the remarkable recent documentary Val, about the actor Val Kilmer, and the ruination of his film career by one misfortune after another, you might have wondered, like I did, if they would find a way to bring Iceman back for Top Gun: Maverick. And they did! The reunion of Maverick and Iceman provides what may be for most viewers the movie's most emotionally affecting exchange. For me, much of that emotion comes from the fact that they invited Kilmer to be a part of this at all! It's just so good to see him again, knowing the suffering he continues to endure.

But I can't help but feel they could have dignified Kilmer and his character by investing more imagination in his return. That's the thing about Top Gun: Maverick — the very few things it does with real imagination shine out as highlights, even though I can still imagine more meaningful choices they might have made even there.

It isn't my aim or my duty to recount the rest of the narrative: Moviegoers are having fun with this one, so, by all means, go have fun! I'm just here to give you some thoughtful first impressions of the film without spoiling it for those who haven't seen it yet.

And it isn't my intention to take cheap shots or merely complain about the movie. [UPDATE: I'm going to say something now in bold print for those who keep firing f-bombs at me for my opinion of this movie, because they seem to be so upset by my Rotten Tomatoes blurb on this movie that they're not able to read the whole review clearly.] I had fun watching Top Gun: Maverick. The flight training scenes and aerial combat are exciting and often exhilarating due to the fact that they aren't animated — they're actual footage of some impressive stunt flying. It's fun to see familiar faces, although I'm not feeling compelled to highlight any particular performance — Cruise is doing things we've seen him do a million times. (As I said in Part One of this essay, He's always best when he's playing a self-doubting villain or a hot-tempered man-child who needs to grow up.) The whole operation has been carefully calibrated as one of the most powerful fan-service productions of all time, giving those who have the first film almost memorized so many dopamine hits — flashbacks, nostalgia hits, variations on familiar scenes — that they'll be grinning as brightly as Tom Cruise himself when it's over. As entertainment that rewards your senses without challenging us to consider anything of real substance, it's great! Director Joseph Kosinski, who made an entertaining but unfulfilling sequel to Tron more than a decade ago, and whose 2013 sci-fi adventure Oblivion surprised me with its extravagant visuals and its playful genre references, is likely to have the biggest hit of his career with this film by delivering everything the studio could have hoped for, everything Tom Cruise could have hoped for, and everything they might have anticipated moviegoers could want.

But I'm not one of the moviegoers they were thinking about. I love a great action movie. This year, I've enjoyed Everything Everywhere All at Once multiple times. Raiders of the Lost Ark, Die Hard, and Mad Max: Fury Road are among my all-time favorite films. And I've seen films about the American military that rank as favorites: The Thin Red Line, for example, is a work of transcendent beauty and wisdom. But I'm afraid that Top Gun: Maverick is a shiny, well-executed barrage of clichés. And it ends up reinforcing archetypes and values that I see as root causes of destructive afflictions in our culture. As much fun as it is when a familiar formula is well-executed, this movie is also an altar to America's obsession with youthfulness, its exaltation of white super-men (showing people of color as inferior), its worship of heavy artillery, its insistence that we not think much about the consequences of violence, its permissiveness toward what we now wisely call "toxic masculinity," its adoration for recklessness rather than integrity, and (sigh) its objectification of women as trophies.