X-Men: Days of Future Past (2014): Or, Confessions of an X-Men Ex-Fan

When Mutants aren't fighting for their rights... what do they do? Do they vacuum their apartments? Do they go to baseball games? Do they watch cat videos?

Or does the Mutant Experience require constant employment of powers against those who hate Mutants, or against those Mutants who abuse their powers?

I hate to say it, but X-Men: Days of Future Past and its four big-screen predecessors (not to mention spinoffs like The Wolverine) make Mutant life look absolutely miserable. For all Mutants.

Anyway... am I the only one feeling fatigue about the sufferings of these characters? Seems like every episode is another version of the same thing. More efforts to eliminate Mutants, more exhibitions of Mutant power used against their oppressors, more arguments about how to use that power. These things reflect important struggles that every generation faces regarding race, sexual orientation, or any other kind of basic human diversity. But sometimes these stories seem so fiercely focused on scenarios that require violence, I just stop believing. By dwelling on the clashes of power, we lose sight of what's being fought for. In fact, we never see it at all.

When director Brian Singer's superhero sequel X2: X-Men United opened back in April 2003, I was thrilled. Here was a sequel that surpassed expectations, delivering on the promise of a first film that broke new ground and made comic book movies seem relevant and exciting. The writing was smart and efficient. The cast was great. The effects were fantastic without being intrusive. And the heart of the whole endeavor seemed... human. It felt inspired by comic books, but it played onscreen like something more substantial.

I blogged that X2 was "the most rewarding big-screen comic book I have yet seen. Anybody working on comic book films — or Star Wars films — should be devoting themselves to understanding what makes the movies of Bryan Singer work."

This all took place during second year of writing Christianity Today's Film Forum, where I was comparing and contrasting the views of other critics from Christian media and mainstream sources. I found a variety of opinions there. (The fundamentalist evangelical movie-morality-watchdog site Movieguide, true to form, used the opportunity to judge one of the actors for his sexual orientation, causing those Christian film reviewers who actually care about art to stand out in stark contrast.) In my Film Forum, I quoted my friend Steven Greydanus of DecentFilms.com: "Larger in scope and darker in tone than its predecessor, as rich in invention but expanding on it, X2 is the most ambitious, sprawling superhero saga to date. This is now one of Hollywood's best and most promising franchises."

With two strong installments, the developing series proved that it was possible, in a genre known for formulaic mediocrity, to make memorable, meaningful movies that could inspire thoughtful discussions. I couldn't wait for the third movie.

Well, a lot has happened since then.

Bryan Singer left the series, as you probably remember, in order to make what turned out to be a highly disappointing attempt at restoring Superman to the big screen. Superman Returns felt like a mix of unnerving nostalgia (Brandon Routh looked like Christopher Reeve, but lacked the charisma) and failed chemistry (the romance was a flop). But what the Superman failure even harder to take was that Singer had done this instead of bringing his X-Men series to a satisfying close, which everyone believed he could have achieved. Instead, we got The Last Stand — director Bret Ratner's crap-tacular ruination of the trilogy. What a letdown. In my X-Men enthusiasm, I visited the set of The Last Stand, and watched the sun go down while the crew raced around in the woods to film a clash between Wolverine and Magneto. Watching the result on the screen, surrounded by X-Men fans, was physically painful.

Bryan Singer left the series, as you probably remember, in order to make what turned out to be a highly disappointing attempt at restoring Superman to the big screen. Superman Returns felt like a mix of unnerving nostalgia (Brandon Routh looked like Christopher Reeve, but lacked the charisma) and failed chemistry (the romance was a flop). But what the Superman failure even harder to take was that Singer had done this instead of bringing his X-Men series to a satisfying close, which everyone believed he could have achieved. Instead, we got The Last Stand — director Bret Ratner's crap-tacular ruination of the trilogy. What a letdown. In my X-Men enthusiasm, I visited the set of The Last Stand, and watched the sun go down while the crew raced around in the woods to film a clash between Wolverine and Magneto. Watching the result on the screen, surrounded by X-Men fans, was physically painful.

After several years of fan resentment, we cautiously approached a prequel directed by Matthew Vaughn — X-Men: First Class. It was an engaging reboot of sorts, led by a cast of up-and-coming stars including James McAvoy, Michael Fassbender, and Jennifer Lawrence. But it showed signs of serious bloat, reaching for something even more epic, and losing the charm of the first two. It was an improvement, but it wasn't enough to make me start watching movie calendars for a follow-up.

And now here we are with Days of Future Past, the fifth X-Men film, the first to combine the casts of both series, and the long-awaited return of Brian Singer to the controls.

While l I felt very little hope that Days of Future Past would stand out from the pack as exceptional, this video review from the tremendously trustworthy Steven Greydanus got my attention:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4SEE8XfMM4Y&list=PLPu38Ui5dTDINmv5o5eF6Y0GAlkTBqoeP

Intrigued, I read his in-depth published review.

And that was enough to rekindle my old enthusiasm, prompting me to hand over more money than I should ever spend on a movie (almost 20 dollars) in order to join some friends for an opening-weekend show.

The result?

While I respect Steven's devotion to the comic book genre and his discernment about what makes a good superhero movie and what makes a bad one, I just can't muster more than a flicker of the enthusiasm he feels for this movie.

It would be easy to go on blaming Ratner for my X-Men disillusionment. But that's not it.

Here's the real answer: I've overdosed on superhero movies. Theaters have become saturated with comic book heroes. New films and sequels seem to pop up every week or two. I've seen so many heroes, so many supernatural powers, so many transformations, so many explosions, so many big cities devastated by supervillains, so many showdowns, so many human bodies pummeled beyond what any real human being could withstand, that I'm exhausted. Going to the movies now feels like going to my favorite cafe for breakfast only to find that 75% of the menu has been taken over by sugary breakfast cereals: high on sugar, low on nutrition. Even a Grade-A superhero movie can make me feel cynical about the state of cinema in general. I read a lot of messages from readers who were frustrated with my non-review of The Avengers, but that was where I felt something snap inside of me.

I understand why Steven Greydanus is excited — he's had a lifelong love affair with comic books, and I haven't. His appetite for this stuff is ten times larger than mine. Back when superhero films were a new frontier — Tim Burton's Batman movies were a hoot, Sam Raimi's Spider-man had real spirit. Things really peaked with Christopher Nolan's The Dark Knight, which made as much or more of superhero source material than I thought possible, and Guillermo Del Toro's Hellboy II: The Golden Army, which showed that the comic book template could be filled to bursting with handmade creativity. But now, steroidal CGI superhero films are a dime a dozen, each one aiming to be bigger and more intense than the last. They've lost me. I'm no longer a member of the audience that these movies are made to please.

When I look back at the history of superhero films, the only one that appears in my list of 120 favorite movies is The Incredibles. And that's because it was a film that was about much, much more than fighting the latest oppressors, about standing up for rights or freedom or the American Way.

There are too many great films in the world that I have yet to see for the first time. Why spend valuable time on more disposable showdowns between mutants and aliens and people produced in a lab?

If I were to write a full review and then set it alongside Steven's, you'd probably see a sort of conversation something like this...

Steven:

"[It's] one of the geekiest comic-book movies ever made — and one of the best. It’s easily the best superhero movie since The Avengers — and, like The Avengers, it plays as a triumphant climax to an uneven series of earlier films."

Me:

Well, on the subject of over-long, overly loud, over-populated, exhaustingly paced, excessively convoluted, suspense-free superhero movies, I can't disagree: This one is an impressive achievement. It's relentlessly entertaining. Helluva ride.

Steven:

"... Days of Future Past brings together various strands of a franchise that sprang from a single source but has grown unwieldy over 14 years and six varying installments. ... [But it] gracefully harmonizes these tensions, weaving together different timelines with older and younger versions of [the same characters.]"

Me:

I can't imagine how difficult it was to write this screenplay. It's quite creative in the way it sews the prequel cast and the original cast together, sure.

But, wow, it's a challenge to follow. The importance of time travel to this script really complicates matters. Keeping straight who's who will be easy for fans, but not newcomers. But even fans will be challenged, I think, as they try to keep track of the characters' varying powers — some of which are different between earlier and later manifestations of the characters.

With so many powers available to Team Mutant, it's hard for me to feel any sense of crisis. It seems there's a superpower that can solve just about anything.

Steven might reply that longtime fans of the comic book series will already be familiar with "an influential 1981 storyline by X-Men chronicler Chris Claremont and co-plotted by writer-artist John Byrne" ... a storyline involving the rise of the fearsome Mutant-killing robots called Sentinels.

To which I'd reply that I'm not one of those fans. Unfamiliar with 30-year-old comic book storylines, I thought that the Sentinels just seemed like Terminator-esque drones made up of the stuff of a dozen other movies. Big, loud, full of fire and bluster, they're just the sort of summer-blockbuster explosion-generators that shoot down my interest in a movie.

I'm not going to try to talk anybody out of liking Days of Future Past. I can see why it's getting such great reviews. It's exactly what X-Men fans want: An even bigger X-Men movie, with even more of their favorite characters from the mythology. It's full of adrenalin-rush action, standard-setting special-effects, and great actors. The film playfully engages with period-piece storytelling by visiting our heroes in the days after Kennedy's assassination, and every few moments we see another superpower employed cleverly in a ploy, a jailbreak, or a fight. And it delivers, in bolder strokes than ever, the same ol' X-Men message about "stop persecuting those who are different" — perhaps the most popular sermon being preached on big screens today. Best of all, it gives us permission to disregard Bret Ratner's installment as if it never happened. Singer has devised exactly the comeback his fans wanted, and I suspect that they'll forgive him that Superman Returns debacle.

If I really admired anything in the film, it was the dedication of the cast. The actors — James McAvoy, Michael Fassbender, and Hugh Jackman especailly — look like they were forced by Singer to watch Sean Bean's death scene from The Fellowship of the Ring every day and told "That's the level of performance I want from you! In every scene!" (Poor McAvoy. Just think about the last three or four films he's been in, and think of how many times we've seen him spluttering and trembling and shouting and red-eyed and teetering on the edge of madness. He must be exhausted.)

If I really admired anything in the film, it was the dedication of the cast. The actors — James McAvoy, Michael Fassbender, and Hugh Jackman especailly — look like they were forced by Singer to watch Sean Bean's death scene from The Fellowship of the Ring every day and told "That's the level of performance I want from you! In every scene!" (Poor McAvoy. Just think about the last three or four films he's been in, and think of how many times we've seen him spluttering and trembling and shouting and red-eyed and teetering on the edge of madness. He must be exhausted.)

But in the whole film, I found only one sequence particularly memorable: one involving the heroics of a newcomer called Quicksilver. He stole the show, upsetting a showdown in the Pentagon with a demonstration of power that is distinct for its playfulness and humor. But (maybe I missed something) why does Quicksilver disappear after that? Why doesn't he follow our heroes through the rest of their adventure? Seems to me that his could have solved all kinds of problems in the second half of the film. Instead, he was... well, what was he doing?

Soon after that scene, I just gave up trying to care. I find that any circuitry I ever had to enjoy this kind of movie was overloaded and melted down by two Spider-man franchises, Captain America, Thor, Hulk, Iron Man, Watchmen, The Dark Knight Rises, and a half-dozen other heavily merchandised blockbusters. So many variations on the same things. So much effort invested in topping what was done last time. So many frames overstuffed with more action than I can hope to track with my eyes or my intellect.

I enjoyed last year's Wolverine movie more than Days of Future Past because it had a sense of pacing, a far more human scale, and it modulated its intensity so that there were real rises and falls, crescendos and decrescendos. This movie is all crescendo, and sometimes several crescendos at once.

And frankly, I'm tired of hearing the mutants complain about their plight. I think the people, the neighborhoods, and the environment all around them that suffer the consequences of their violent clashes... well, I have more and more sympathy for them all the time. I don't come to care for Mutants by watching them fight back against villains. But I might come to care for them if I saw some storytelling about who they really are, and what it's like to live like one. How many times must we hear a Mutant moan "Humans hate us because we're different, never mind that we're laying waste to their cities and armed forces and police squads and famous buildings in movie after movie after movie"?

And frankly, I'm tired of hearing the mutants complain about their plight. I think the people, the neighborhoods, and the environment all around them that suffer the consequences of their violent clashes... well, I have more and more sympathy for them all the time. I don't come to care for Mutants by watching them fight back against villains. But I might come to care for them if I saw some storytelling about who they really are, and what it's like to live like one. How many times must we hear a Mutant moan "Humans hate us because we're different, never mind that we're laying waste to their cities and armed forces and police squads and famous buildings in movie after movie after movie"?

Before Days of Future Past ended, I found myself thinking about Star Wars, and, well... I have a bad feeling about this.

I suspect that Days of Future Past shows us where Star Wars is going next: More and more of what the fans want, more and more climactic and explosive conflicts. The stories in the original Star Wars trilogy could be told. That is to say, you could read them in a fairly simple storybook and follow what was happening. The first two films in the X-Men series were somewhat similar that way. But I fear that, as with the Marvel Universe stories and the Abrams Star Treks, we're going to watch the Star Wars storylines become blackberry vines, spreading wildly, becoming impossibly intertwined, knotting themselves up until we spend so much time talking about trivia that we're no longer thinking about what these stories once meant to us. At some point, it stops feeling like storytelling. Instead, it feels like we're watching rounds of some massive multi-player game where characters' powers can be juxtaposed and combined in endless variations. Moments of real gravity and imagination will become rarer and rarer in the sprawl of More, More, More. They'll become elaborate, overly self-referential, expanding and exhausting variations on Yoda's sermons: "Anger, fear, aggression... the dark side are they."

I would so love to see screenwriters set free to explore new storytelling territory, asking new questions, allowing Star Wars to grow in quality, not just quantity.

Deep into Days of Future Past, Professor X gives a short homily about the power of hope. Patrick Stewart delivers these lines with dignity and emotion. And they sting all the more because it was hope — hope for some real vision and imagination — that led me to hand over almost 20 bucks to see this movie. If anybody's ever going to restore my hope in this genre, they're going to have to catch me off guard. They'll have to draw me in with reports of poignant storytelling and unforgettable images.

That is to say: depth over sprawl, revelation over rehash.

The Return (2003): Why Moviegoers Everywhere Must Learn to Say "Zvyagintsev"

If you hear film buffs shouting "Zvyagintsev!" in the coming months, do not say "Gesundheit." The proper response is this: "When do I get to see Leviathan?"

Congratulations to Russian filmmaker Andrey Zvyagintsev for winning the screenplay award at the 2014 Cannes Film Festival for his new film Leviathan (not to be confused with the documentary film by the same title that was in my top 5 favorites of last year). Having eagerly surveyed the critics' responses to the films that played there, Zvyagintsev's Leviathan is the Cannes contender movie I'm most excited to see in the coming year. In The Guardian's five-star rave, Peter Bradshaw says "Andrei Zvagintsev's latest is a very strong contender for the Palme d'Or — a mix of Hobbes, Chekhov and the Bible, full of extraordinary images and magnificent symmetry."

Sony Pictures Classics bought it, and here's hoping they bring it to America right away.

Ten years ago, upon seeing Zvyagintsev's first feature film, The Return, I said on this very blog, "Watching this film, it’s hard to shake the impression that you’re seeing the debut of a great artist. It’s too early to say if Andrey Zvyagintsev is one of the great filmmakers of our time. But the one film he has made deserves to be discussed in the same way we discuss work by Tarkovsky (The Mirror), Kieslowski (The Decalogue), and Bresson (Diary of a Country Priest)."

2004 was a year of cinematic discoveries for me. The three English-language releases that won my enthusiasm were Danny Boyle's Millions, Pixar's The Incredibles, and Michel Gondry's Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind. But the four films I enjoyed the most in 2004 were films I discovered for the first time, but that had already been revered as masterpieces for years. They were Robert Bresson’s Au Hasard Balthazar, the most unforgettable two hours I spent in a theatre; Bresson’s A Man Escaped, a similarly profound and challenging masterwork; Béla Tarr’s Werckmeister Harmonies, which is very difficult to find (I saw it thanks to a generous friend with a VHS copy); and Tokyo Story, the masterpiece by Yasujiro Ozu about family ties, respect for one’s elders, and the necessity of humility and love.

Looking around, I didn't see any new 2004 releases that shared that kind of timeless poetry ... except one: The Return.

Here are some of the first-impression notes I jotted down...

•

Watching this film, it’s hard to shake the impression that you’re seeing the debut of a great artist. It’s too early to say if Andrey Zvyagintsev is one of the great filmmakers of our time. But the one film he has made deserves to be discussed in the same way we discuss work by Tarkovsky (The Mirror), Kieslowski (The Decalogue), and Bresson (Diary of a Country Priest).

Great storytelling, excellent cinematography, a beautifully subtle soundtrack, sensational performances by three actors, a poetic script resonant with Biblical allusions — The Return is never indulgent, never superfluously stylish, and always convincing. That is what sets it apart from the handful of films I considered choosing as my top recommendation for 2004.

The story follows two brothers who must deal with the unexpected "return" of their father, a man they've never known. They try to take their mother's word for it, but when the mysterious, quiet man takes them on a journey that morphs from fishing trip into a desperate and frustrating mystery, the brothers argue passionately over the man's true identity and what he intends to do with them. Are they being led to their deaths? Is this a rite of passage into manhood? Is it a lesson in wilderness survival skills? What in the world is going on?

On a deeper level, the film leads us to ask questions about our own experiences with authority figures. Is it ever enough to just "trust and obey"? Is it arrogant for us to demand justification for the behavior or instructions of our elders? If there is a god, what is he like? Is it cruel for God to expect unquestioning obedience of us? Or is it his right? What is God really up to, and what is our part in his plan? Does he love us? Would he place us in danger unnecessarily, or has he ever demonstrated his love for us in any significant fashion?

The film ultimately feels like a lost Dostoyevsky novella brought to life. It powerfully echoes questions that have haunted spiritual seekers since ... well ... since God first told us not to mess with that blasted tree.

Like each episode of Kieslowski's Decalogue, The Return is a small but potent story that never becomes preachy, didactic, simplistic, or dishonest. And yet it captures how good and evil work in our lives. It fulfills the highest rule of art: "Show, don't tell."

The relationships, the motivations, the decisions all goad us to see ourselves in these characters, and to abstract from the specifics into discussions of our impressions of God and our responses to him.

The conclusion is confounding, frustrating, and yet brilliant because it is specific to this story rather than merely an allegorical flourish. I was on the edge of my seat in those final minutes, worried that the film was going to become too obvious in its implications, rather than merely suggesting spiritual realities. Instead, the opposite occurred: The film arrives at a provocative conclusion that will get viewers talking and suggesting a variety of interpretations.

The two young actors, Ivan Dobronravov and Vladimir Garin, are extraordinary as the brothers who respond to their new father figure in starkly contrasting ways. I hope to see their faces again. Konstantin Lavronenko is perfectly opaque as the father — the role could easily have been overplayed to exploit our hopes or fears, but he remains mysterious, played with just enough particularity to be persuasively human, but remaining enigmatic enough to suggest archetypes of patriarchal authority from fathers to governors to God.

What resonates for me most in the film is not the theological implications of the father's behavior, but rather the implications of what the two boys' responses are to a fatherly authority figure. I can't help but ask myself which brother I most resemble in my responses to authority figures... especially God. Am I Vanya, a suspicious doubter who wants to know why my designs for the journey are so often frustrated in favor of some mysterious, larger purpose that remains beyond my reach? When I get angry and self-absorbed, God doesn't put his plans on hold to wait for me to catch up and get excited about them. It's up to me to engage with God at this point, because he's gone out of his way to engage with me time and time again. Will I obey begrudgingly? Will I obey wholeheartedly? Those who do wholeheartedly obey without blinking ... are they gullible fools, or are they just kissing-up to the Authority in order to be treated like the favorite son?

I'm already eagerly awaiting Zvyagintsev's next film ... just as I will eagerly await someone to tell me how to pronounce his name, so I can go around shouting it.

My friend and colleague Michael Leary wrote about the film for The Matthews House Project, pondering how the film sizes up to the work of Russian master filmmaker Andrei Tarkovsky. He wrote:

Tarkovsky's films do deal explicitly with spirituality and psychology of certain cultural situations, but they do so with a social or historical realism that roots the spiritual revelations of his films within the unfolding of concrete, historicized realities rather than mythical ones. The Return on the other hand opts to be driven by overtly mythical overtones, and the strength of the film lies in Zvyangintsev's uncanny knack for storytelling. He chooses simply to focus on his characters and their story instead of the culture of post-Soviet Russia, a theme which pervades much of contemporary Russian filmmaking.

At Catholic News Service, Gerri Pare wrote:

For those who prefer their movies to offer neatly wrapped-up narratives, The Return won't offer much of a return for the investment, but it's possible to look beyond the melancholy story and appreciate the incisive character studies. The story suggests biblical dimensions of good and evil and the unwelcoming landscapes and choppy waters add to the thriller-like atmosphere of foreboding and dread that populate this chilly, enigmatic tale.

Gadzooks! A Godzilla for Malick Fans?

Change my mind, moviegoers.

I've made clear that I'm done with movies that turn urban devastation into entertainment. I still haven't given two hours of my life to watch Man of Steel, thank God. But the more I read about Gareth Edwards' Godzilla, the more intrigued I become. Might this film actually give me food for thought? Or are film reviewers simply showing signs of desperation, clutching at straws in order to find something to say while yet another blockbuster comes in like a wrecking ball to bust up city blocks?

Here are some of the more intriguing paragraphs I've read about Godzilla...

Matt Zoller Seitz on Godzilla:

While "Godzilla" is less a satisfying drama than an immense, sometimes terrifying sound-and-light show, it's got a good heart. It's tough but never glib or cruel. Even when its titular amphibian is rising from the sea to flood and crush major cities, the film never becomes a mere display of special effects prowess. We're aware that Godzilla and his foes are animals—parts of a long gone, pre-prehistoric ecosystem, like the real creatures that dot the movie's margins: bats, birds, iguanas, dogs, wolves, beetles. There's a bit of H.P. Lovecraft in how the script (credited to Max Borenstein) turns the kaiju into mythic reminders of humanity's arrogance and youth, and an unexpected (but delightful) touch of Terrence Malick's Transcendentalist humility in how the director lavishes attention on meadows and forests and rolling waves. (The movie's final shot evokes "The Thin Red Line." Yes, really.)

At The Dissolve, David Ehrlich writes:

At The Dissolve, David Ehrlich writes:

In Godzilla, almost all human action is futile and/or fatal.... Godzilla is both humanity’s reckoning and its salvation, a response to our unchecked parasitic relationship with the planet and a reminder of our ultimately supporting role as stewards rather than beneficiaries. Steven Spielberg exerts an undeniable influence on the way the film moves, but Hayao Miyazaki’s work best anticipates where it goes. If Jurassic Park is about the perils of playing God, Godzilla responds that just being ourselves is bad enough.

...

Godzilla isn’t an action movie, it’s a spectacle of humility.

...

This is a story about exposing the myopia of the human perspective and then humiliating our inherently egocentric POV. We’re just another part of the equation Godzilla has come back to balance, an urgent reorientation that Edwards turns into a story by gradually disempowering his human characters, conflating us with the bad guys until Godzilla can emerge as an aspirational figure.

...

The film’s evocative closing shot serves as a resonant reminder that just because we’re the planet’s predominant storytellers doesn’t mean that the story is necessarily about us.

Meanwhile, thanks to Josh Larsen at Think Christian for bringing Elijah Davidson's brilliant Godzilla-meets-Job piece to my attention:

I’m glad I’m not the only one who thinks of Job when watching Godzilla.

...

Elijah Davidson, co-director of Reel Spirituality, recently watched the older version for the first time and afterwards put together this frame-by-frame comparison of the 1954 Godzilla and descriptions of Leviathan from Job 41. Eyes like the rays of dawn? Breaking iron as if it was straw? Causing the depths to churn like a boiling pot? Certainly sounds like Godzilla, and Davidson has the pictures to prove it.

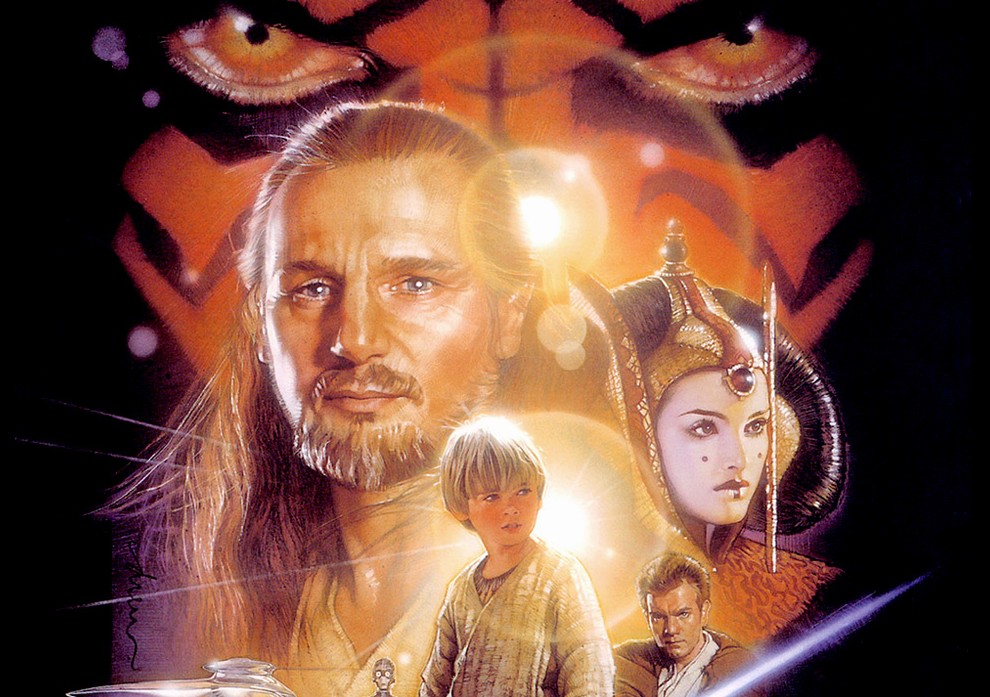

Star Wars - Episode 1: The Phantom Menace (1999): Looking Back 15 Years

UPDATE: May 2014

Star Wars - Episode One: The Phantom Menace is 15 years old this week.

I know, I know. Take a deep breath. Let go of your anger, young Jedi.

Most of us agree that it was a major disappointment. Many had hoped for a new trilogy that would be, for a new generation, what that first trilogy was for those of us who experienced it as children — something truly revolutionary, enthralling, and worth watching over and over again. But it was easy to see, right away, that The Phantom Menace was not that kind of event. And time has not been kind to it.

Fact is, the revolution happened just months before Menace arrived. It was called The Matrix.

Moviegoers were caught off-guard by a film so efficient, exciting, and innovative that Menace seemed bloated and even boring by comparison. Who would have thought that the year of Obi-wan Kenobi's return would conclude with the world talking excitedly about something starring Keanu Reeves from the makers of Bound?

Still Star Wars had the power of legacy — it was still the most important and beloved big-screen franchise. We had no notion, yet, of what would happen when Peter Jackson's The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring would open. I was hopeful. I was even willing to forgive its stumbles in hopes that the second and third parts would build upon its potential.

Two years later, Jackson came along and set the bar far, far higher by showing what was possible when you combined the mythic sweep of Star Wars with rich literary source material, first-rate acting, and an appreciation of natural beauty. (There's nothing in the Star Wars universe to compare with the beauty of New Zealand.)

Months after Fellowship arrived, Joss Whedon's Firefly premiered on television... and it seemed to be made from everything that The Phantom Menace was missing. It captured much of the first Star Wars trilogy's magic in the sharply drawn characters; the efficient and engaging banter; and taut, suspenseful storytelling. Nathan Fillion's Mal was clearly created in tribute to Han Solo. Fox did a fine job of mishandling the series, showing the episodes out of order and burying it on Saturday afternoons. But a lot of Star Wars fans found it, and now they cherish that series more than any of the Star Wars prequels.

So now, with so many brighter lights outshining it, it's difficult for me to remember what it was like to see The Phantom Menace when it opened. What was fresh and exciting there now looks like mediocre even by standards of TV adventure series. Its heavy exposition, its mediocre performances, and its leaden dialogue — I'm obligated to mention the abrasive Jar Jar Binks — disrupt the film's occasional flourishes of the old Star Wars magic.

In retrospect, 1980's The Empire Strikes Back seems like a film from an altogether different franchise: Involving, frightening, endearingly hand-crafted, acted by creatures we recognize as flesh-and-blood human beings who are driven by real passions... if there was ever any doubt that it's the strongest film in the series, those doubts are demolished now. Empire was written and directed by people who were interested in taking characters seriously. It still powerfully suspends my disbelief. By contrast, Phantom Menace feels like a movie made by the "Yes Men" of a CEO who has become tone-deaf as a writer, preoccupied with merchandising and digital effects innovations, and indulging nostalgic whims that seem incongruous with world he had already established, the world that so many moviegoers had loved. The result looks computer-generated, plastic, and artificial.

So I look back on my original review of this film with some chagrin. The big screen was starved for inspiration, and there was just enough in The Phantom Menace to make me grateful for its arrival. But that gratitude was quickly overcome by frustrations over mediocrity and missed opportunities, which were accentuated by better work from imaginations that had grown up fueled by the inspiration of Lucas's earlier work. I would trade the whole prequel trilogy for a couple of new episodes of Firefly.

And as we look forward to J. J. Abrams's resurrection of the franchise, it's worth pointing out that Star Wars movies will shine only insofar as they are crafted by people who value the power of real actors, real materials... and characters that look like they might actually have existed a long time ago, in a galaxy far, far away.

•

Star Wars, Episode One - The Phantom Menace: The Looking Closer Review (1999)

George Lucas shows us with Star Wars - Episode One: The Phantom Menace that he can still give audiences more special-effects dazzle and more fantasy mayhem than any other director.

While it’s certainly flawed, and in some ways deeply disappointing, The Phantom Menace is still an entertaining, occasionally exhilarating, ultimately exhausting adventure movie. Lucas has never been a great director of actors, and he now seems to have more interest in people standing around and talking than in gunslinging action (which causes most fans of the original Star Wars trilogy to squirm fitfully throughout this film). But let's be fair: Lucas is also telling us a different kind of story — a story about politics, about government, about a galaxy in a period of relative peace in which cracks begin to spread that will lead to a collapse as dramatic as the sinking of the Titanic.

Aragorn's Favorite Peter Jackson Movie (Hint: It's Not The Return of the King)

It's another return of the king!

Aragorn is back, and he is as full of wisdom and insight as we might expect.

Viggo Mortensen was interviewed by Tim Robey for The Telegraph, and he is reflecting on his experiences playing the part of Aragorn in Peter Jackson's Lord of the Rings films.

To be fair, Mortensen also talks about other chapters of his career and his latest projects.

But what's especially interesting for me — and, I admit, satisfying — is that Mortenson's perspective on Jackson's films sounds an awful lot like what I wrote in my reviews of those films... including both installments of The Hobbit that we've seen so far.

Here's an excerpt*:

Mortensen thinks – rightly – that The Fellowship of the Ring turned out the best of the three, perhaps largely because it was shot in one go. “It was very confusing, we were going at such a pace, and they had so many units shooting, it was really insane. But it’s true that the first script was better organised,” he says. “Also, Peter was always a geek in terms of technology but, once he had the means to do it, and the evolution of the technology really took off, he never looked back. In the first movie, yes, there’s Rivendell, and Mordor, but there’s sort of an organic quality to it, actors acting with each other, and real landscapes; it’s grittier. The second movie already started ballooning, for my taste, and then by the third one, there were a lot of special effects. It was grandiose, and all that, but whatever was subtle, in the first movie, gradually got lost in the second and third. Now with The Hobbit, one and two, it’s like that to the power of 10."

In case you missed them, here are some of my posts and reviews related to Jackson's adaptations (or desolations?) of Tolkien.

Here are my interviews with the cast and makers of The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King

Here's are my original reviews of The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring (newly restored to my online archive, by request); The Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers (a shorter version was published in Christianity Today), and The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King (also originally published at Christianity Today).

And here are my reviews of The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey.

At Seattle Pacific University’s Response magazine: “Back to Bag End.”

At Image’s blog – Good Letters: “The Hobbit on Steroids.”

And here's my response to The Hobbit: The Desolation of Smaug.

*Thanks to Anodos at artsandfaith.com for bringing this interview to my attention.

30 Must-See Movies for Kids

Over at Letterboxd, where I keep a journal of the movies that I see, I've added some new film lists.

One is the result of a Facebook prompt: My friend Sarah Partain was listing her favorite films for children, and she suspected that my list would be similar. We do share several favorites, but I became ambitious and ended up with a list of more than 30.

I consider it a work in progress, so feel free to suggest others, and they may show up on my revised list.

Keep in mind: I was thinking of films for children, not teenagers. I was tempted to include films like The Fellowship of the Ring and The Empire Strikes Back, but those feel like adventure films made with a teen-to-adult audience in mind. The movies on this list I recommend specifically for children, although some, like Watership Down, are took dark for very young children.

Other recent lists I've posted at Letterboxd include:

Overstreet’s 30 Favorite Directors (by favorite title) (alphabetical)

“Also Starring Tom Waits”: In Order of How Much I Love Him In It

Treasure: My Favorite Films from Each Year of My Lifetime

And, of course, the mandatory, ever-changing Jeffrey Overstreet’s Favorite Films.

And there are many more.

I recommend you start your own Letterboxd account. It's becoming one of my daily internet stops, a place to keep a film diary, and to discover and discuss new films with enthusiastic and intelligent moviegoers.

•

If you appreciate this post and enjoy Jeffrey's work exploring the territory where art, faith, and culture intersect, you're invited to "Put Your Name in the Credits." Cast your vote for "Keep Looking Closer Alive." Make a donation. Offer whatever you feel moved to contribute. All donations will be applied directly to that materials, events, and experiences that make the blog happen. That's a Looking Closer promise.

Ten Years Ago Today...

Just marking the occasion...

Seems to me the best way to mark the 10th anniversary of this blog is to point you to the essay that inspired it — a few words about art and discernment written by my friend, mentor, and high school English teacher, the photographer Michael Demkowicz. It's called "Mystery and Message: What We Talk About When We Talk About Art." It's the closest thing this blog has to a mission statement.

Stay tuned for ongoing 10th anniversary posts, as I continue to look back at the highlights of each year of Looking Closer's first decade.

In case you missed them, here are the reviews so far:

If you appreciate this post and enjoy Jeffrey's work exploring the territory where art, faith, and culture intersect, you're invited to "Put Your Name in the Credits." Cast your vote for "Keep Looking Closer Alive." Make a donation. Offer whatever you feel moved to contribute. All donations will be applied directly to that materials, events, and experiences that make the blog happen. That's a Looking Closer promise.

Saving Mr. Banks (2013) ... or Squandering Mr. Hanks

Dear moviegoers who enjoyed Saving Mr. Banks, including those among my friends and family,

I'm glad you had a good time at the movies.

Seriously.

I would be nothing but a snob if I scorned anybody for enjoying a heart-warming work of fiction like this one.

I recognize that there are a lot of things moviegoers will enjoy here:

- Tom Hanks, being witty and skillful;

- Emma Thompson, being amusing and... British;

- nostalgic musical celebrations of Mary Poppins™;

- Paul Giamatti, in warm and lovably congenial mode;

- Colin Farrell and Ruth Wilson finding some humanity in a child's tragic flashbacks.

You see, Disney baked this big, heavily frosted cake to make people happy, and that's what they've done.

But if you want to hang on to that warm feeling, you may just want to stop reading — because "happiness" is about the opposite of how I felt when I finally sat down to watch Saving Mr. Banks.

I wanted to enjoy the movie the way you did. But I could not, and I'm going to explain why. You may think I'm just being impossible and unreasonable. You may roll your eyes just like Walt and the Sherman brothers—Richard and Robert—do in this movie whenever P. L. Travers voices her grievances about their plans to turn her beloved novel into a movie. Nobody likes a party-spoiler. Audiences are laughing at Travers' obstinance because, well, most of us have had to deal with a stick-in-the-mud before. No wonder this movie is a crowdpleaser: It's about joyful entertainers who find a way to bend a grouch to do what they want. To use the movie's own words, it's about "teaching the witch to be happy" — even though you can hear them thinking of a word that rhymes with "witch."

I just want to ask two questions:

1) Do the ends justify the means?

That is to say: If an artist means to give audience a good time, does he have license to rewrite recent history so that the climax of the story is completely false, misrepresenting the character of the film's central historical figure?

Many made a fuss when Spielberg's Lincoln arrived because it testified that one congressman voted for slavery when, in fact, the record shows that he voted to abolish it. In Saving Mr. Banks, we have a far more egregious departure from the eyewitness testimonies.

But we'll get back to the question of historical accuracy later. Most films that are 'based on a true story" are revising that history in one way or another. Before we talk about how much revision is appropriate, let's pretend that this movie gives us a "true story" ... and get to my second question... the one that burns me like heartburn as I watch this film.

2) The movie concludes with all of the fanfare of a Disney happy ending. But is this really a happy ending? Or is it a tragedy?

Seriously, how is this a happy ending?

Saving Mr. Banks tells us a story in which two misguided characters clash over a collaboration. One of them has a warm, welcoming personality, and he just so happens to be a beloved figure in entertainment history. The other is relatively unknown by audiences, and she's shown to be unpleasant, bitter, and exasperating. We're talking about personalities here. But personalities and convictions are two different things. To the audience's delight, Mr. Nice Guy prevails over Mrs. Madness. But what really happened here? Was Mr. Nice Guy really "the Good Guy" who should have prevailed?

I'll tell you what happens in this movie: A businessman takes away an artist's personal vision and refashions it to what will please the majority rather than what will convey what the artist meant to express in the first place. He has done so by putting her under tremendous pressure, driving her into a decision she doesn't want to make. And this is tragic because, all along the way, his own ideas were good enough that he could have built his own original story without stealing a storyteller's property and causing her great distress.

I have a personal aversion to Christian pop music that copies the sound and style of mainstream artists and rewrites the words into pandering praise lyrics. In the same way, I'm allergic to the way that Walt Disney Sudios has plundered the treasure chest of children's stories, legends, fables, and fairy tale — ripping the big, beating hearts from those stories' chests and replacing them with mechanical Disney cliches. Disney often tells us what we want to hear rather than what we need to hear. Until recent years, when some admirable exceptions have arrived (thanks to the influence of storytellers like Andrew Stanton, Brad Bird, and John Lasseter), almost every family film that Disney has produced has been a cliché-heavy story of "follow your heart" or "find your Prince Charming."

In Saving Mr. Banks, we see Disney as the Evangelist of Crowdpleasing determining to exploit the work of Travers as the "unbeliever." It ends by providing a Happy Ending that celebrates Disney's own legacy, and that forces the character of Travers to end up weeping in the realization that Disney's vision is superior...

... which (and now we're back to Question 1) isn't what happened.

In taking on the story of Walt Disney and P.L. Travers, director John Lee Hancock and his collaborators had a chance to tell what is, in truth, a story rich with provocative questions about telling the truth, about collaboration, about art, about entertainment, and about how artists can give the world tremendous gifts that have been made from the wounds they've suffered. Instead, they've made a film that Disney is right from the beginning, and that the only proper way to end the movie is to revise history and force Travers to bow to his superior wisdom.

You can see from the very beginning that this isn't a movie about art... it's a movie about breaking the stick-in-the-mud.

"The creator of our beloved Mary!" shouts Don DaGradi (Bradley Whitford).

"Poppins," says Travers. "Never, ever just 'Mary.'"

Immediately Travers is portrayed as impossible. But doesn't she have the right to ask people to respect her work, whatever her personality? The name "Mary Poppins" does, indeed, give us a different impression than just Mary. Surely she has the right to impress that upon the storytellers. It sounds wise to me. But the moment is staged to make us laugh at her ridiculousness, and to sympathize immediately with the Disney storytellers who see Mary Poppins as theirs... already!

Disney is portrayed as a longsuffering saint, bent on blessing the world by prying treasure free of the greedy hands of the person who found it, who owns it. Or, as I saw it, he plays a corporate CEO who is so used to getting his way that he's insulted when a mother won't easily hand over her dearest child to be despoiled of her lessons and brought up all over again from the beginning to suit his fancy.

I don't for five minutes believe that this film's "What Really Happened" story is much like what really happened at all. It's all too Holly-wood-ified and all-star-cast-ified.

Thompson understands that she's supposed to play Travers as stubborn and demanding. But when we finally hear Travers' real voice during the film's closing credits, we learn just how exaggerated Thompson's performance has been. She's played a sort of Saturday-Night-Live caricature. I'm guessing that the filmmakers asked Thompson to watch Downtown Abbey and play Travers the way that Dame Maggie Smith would have played her—furrow-browed, scornful, aloof, stubborn, nose turned up.

The whole time, I was left wondering one simple question: If Disney wanted to tell his own version of the story so badly, why not just change the names and tell the story he felt was best? Why must there only be one story about a nanny who comes to help children struggling in a dark and money-corrupted world? People write derivative stories all the time? Why did the film have to have the title, the names, and the direct association with Travers?

One reason: Money. The book was so beloved — so beloved for what it was — that Disney new he'd draw a huge audience if he could exploit that popularity. For all that he's saying about taking this character that his daughter loves and putting her on the screen, well... he's not bringing that character or that story to the screen. He's bringing something quite different altogether.

"You don't know what she means to me," Travers tells Disney. And the movie, trying to salvage Disney's character, gives him intimate moments where he reveals to her that he understands better than she does.

And before the movie is over, we'll see her weeping in ecstasy as the movie breaks her heart with its beauty.

That is not what happened, apparently.

I'm all for artistic license, but not when the studio rewrites history to glorify its namesake at the expense of someone else. Here is a Disney movie telling us that the wrong-headed artist finally caved in and bowed down to him, when Travers reportedly wept through the movie because she was so upset about having her child ripped from her hands and brought up to be something quite contrary to her wishes.

Steven Greydanus is far more forgiving in his attitude toward this film than I can be, but he does say,

Saving Mr. Banks is history written by the winner: a Disney movie that regales us with just how ridiculously hard a prickly, capricious British authoress made it for our Uncle Walt to bring us Julie Andrews and Dick Van Dyke in one of the most beloved family films of all time.

Walt won that war of wills and Disneyfied Mary Poppins; now, adding insult to injury, he’s Disneyfied her creator, playing her abrasive personality for laughs as well as making her more conventional than she seems to have been. Travers has become a ridiculous creature of fun, just as she feared Mary Poppins would be. The closer Saving Mr. Banks is to history, which I suspect is not very, the more deeply it would doubtless have enraged Travers.

Perhaps if you love Disney’s Mary Poppins, you can shake your head indulgently at Travers’ misguided efforts to thwart the cinematic apotheosis of her magical nanny: Some people just don’t know what’s good for them. I confess I’ve never fallen under Mary Poppins’ spell, either on the screen or on the page, but for what it’s worth, my sympathies are rather more with Travers than with Disney.

Read more: http://www.ncregister.com/daily-news/sdg-reviews-saving-mr-banks#ixzz30aqyy3lV

And I find myself nodding along with Amy Nicholson as she writes:

Why does it matter that Saving Mr. Banks sabotages its supposed heroine? Because in a Hollywood where men still pen 85 percent of all films, there's something sour in a movie that roots against a woman who asserted her artistic control by asking to be a co-screenwriter. (Another battle she lost — Mary Poppins' opening credits list Travers as merely a "consultant.") Just as slimy is the sense that this film, made by a studio conglomerate in a Hollywood dominated by studio conglomerates, is tricking us into cheering for the corporation over the creator. We take sides because we can't imagine living in a world without the songs the Sherman brothers wrote for the film: "Let's Go Fly a Kite," "Feed the Birds," "Chim Chim Cher-ee." We wouldn't have had to either way; if Mary Poppins had collapsed, Walt planned to package up the songs wholesale for Bedknobs and Broomsticks.

Saving Mr. Banks would have been a meaningful contribution to the Disney legacy if it had actually portrayed P.L. Travers. But Richard Brody concludes:

Travers’s life left plenty of fascinating backstory for Hancock and his screenwriters to explore. But by narrowing it to her childhood in Australia, they elide the underlying cultural conflict between her and Disney—the age-old confrontation between art and commerce, between uninhibited personal expression and commercial bowdlerization—and reduced it to a story of two adults who still have issues with their fathers.

Travers would have been right to suspect that Hollywood—and, especially, Disney—could never show anything like intimate life as she knew it to be. Had “Saving Mr. Banks” shown Travers in all her complexity, it would have redeemed the studio’s honor—would have proven that a family-friendly movie could expand its definition of family to embrace those which, formerly, were beyond the studios’ purview. It would have been a vision of progress—or, dare I say, of hope. Instead, perversely, the movie of 2013 reënacts the willful omissions, the moralistic elisions from a movieland more than half a century old.

It would be very easy to create a Cape Fear-like "Fake Trailer" for this film in which Travers is a wounded, panic-stricken artist struggling to escape Disney the Stalker Businessman. That's the movie I'd rather see, actually. It would be far more interesting. It would also be, unlike Saving Mr. Banks, based on true story.

Instead, what we get is It's supercalifragilisticexpiali-shameless. A spoonful can help the medicine go down, but it can also trick audiences into swallowing a lie.

The biggest shame of all is that this is how Disney squandered our opportunity to see Tom Hanks play Walt Disney. He's perfect for the part. And with the right script, they could have made an extraordinary film about one of history's most influential imaginations.

Only Lovers Left Alive (2014) — Forget Twilight: These Are My Favorite Vampires

We're all vampires.

That is to say, we all have particular kinds of "blood" that we seek — sources of sustenance and inspiration that keep our eyes open and our hearts beating in a dark and punishing world.

For me, it's a particular kind of beauty and mystery that I find in art. That art cost the artists their own blood, sweat, and tears. It cost them countless hours of labor. It cost them, to some extent, their lives. But I need the passion they have poured on on paper, the dreams they have released through the veins of their guitar strings, the pain they have endured to give something meaningful to the world.

In my memoir of dangerous moviegoing, Through a Screen Darkly, I've written about how the pursuit of excellence in artistry has led me off on a lonely road. As I followed my questions, obsessions, curiosities, and passions, the art that called to me led me farther and farther from the commercial entertainments that dazzle (and sometimes merely distract) "the Majority." Even as I have found greater and greater joys, more and more substantial sources of sustenance, I've also felt a greater alienation from the Majority, and a deeper sadness at just how much great work goes overlooked and misunderstood by so many. It seems that many settle for splashing in puddles and never move on to discover the rivers, the lakes, and the seas of great art.

I know, I know: These sound like the words of a snob. But ask yourself: What in your life are you passionate about? If you like mountain climbing, don't you wish that you could bring the Majority with you, if you could show them the view from a mountain peak, they would change their lives and strive for those rewards with greater zeal? If you love baseball, don't you find yourself wishing you could communicate to the Majority just how marvelous and mysterious and thrilling and fascinating this sport that bores so many can be? If you are a "foodie," and you discover a favorite restaurant that nobody else knows about, don't you wish you could reveal the particularities of that place to people who seem content to live on burgers and fries?

For me, it's movies. And I wish I could open up the worlds of director Jim Jarmusch to larger audiences of moviegoers. But the rewards of his work are only likely to come to those who invest a lot of time and patience and discussion in the experience. He does not design his work for those who accept only instant-gratification. (I tried to describe Jarmusch's artistry in a two-part blog post — here and here — when his last film, The Limits of Control, arrived.)

The curse of the vampires in Jim Jarmusch's new film Only Lovers Left Alive is that they are lovers of all that is best in life. Their physical need for nourishment from human blood reflects the way each one of us needs beauty, truth, and excellence — the good things that human beings "spill blood" in order to convey.

Adam, played with magnificent gravitas by Tom Hiddleston (Loki from The Avengers), is an ancient vampire who has learned to love — and help create — the best of art and culture through the centuries. He is increasingly depressed, put off by the ignorance, the immature appetites, the thrill-seeking, the recklessness, the childish and unthinking ways of "the zombies" ... by which he means the majority of the human race. By this perspective, it is not the vampire but the common human being who is a monster — the one who follows appetites in the pursuit of happiness, rather than following discernment in the pursuit of life-giving beauty and sustenance.

By the way, Adam lives in Detroit — a place that was once a symbol of America's passions and its drive for excellence and innovation. But now, Detroit is in ruins, a ghost town, a place that represents the disintegration of America's greatness. He can still find a decent rock and roll show from time to time, but most nights you'll find him playing with guitars and amps in his haunted house, trying to drown his blues in sound.

His "dealer" — a "zombie" called Ian (Anton Yelchin) who is "alive" enough to recognize the greatness of Adam's music — brings him vintage guitars for his collection and he jams through the night in search of the next beautiful noise.

But Adam cringes at the idea of fame. The truly tremendous artists, he believes, know better than to fall into the trap of celebrity. Nevertheless, his music is leaking out into the world, where it will be exploited and, ultimately, misunderstood. His depression is leading him, at long last, to suicidal thoughts.

Adam, being a lover of all good things, has a timeless love for Eve, his partner in passion through the centuries. Eve, played beautifully by Tilda Swinton, lives in Tangier, where she hangs out with another ancient vampire — Christopher Marlowe (yes, that Christopher Marlowe). Marlowe — John Hurt, magnificent — snarls about Shakespeare as a hack and a thief, and bemoans how difficult it is anymore to find blood that isn't "contaminated." This, too, speaks to how difficult it is for those who love good things to find authenticity in art and culture, things that are not corrupted by commercial influences.

So what happens when these melancholy guardians of cultural treasures are visited by Eve's long-absent younger sister, Ava? Ava has no sense of responsibility, no respect for what is truly valuable in the world. Mia Wasikowska plays Ava with the energy of a rambunctious, undisciplined child.

These characters, as they drift through urban disintegration, are the ultimate Jim Jarmusch characters. Like the burdened pilgrims in Down by Law, Dead Man, Ghost Dog, Broken Flowers, and The Limits of Control, they are possessed by a terrible melancholy as they tour the world in search of something worth living for, as they watch mediocrity flourish and excellence neglected, as they see people settle for insufficient, manufactured comforts. They are philosophical loners, wandering through wastelands. Cherishing what is wise and wonderful, they are doomed to alienation. And their need for one another runs deep.

Only Lovers Left Alive is Jim Jarmusch's dark and mournful version of Wim Wenders' Wings of Desire. His angels are vampires. And as these immortals watch over a decaying city (Detroit, this time), they are not exhilarated by the movement of grace so much as burdened by disappointment with, and even contempt for, careless and zombi-fied human beings. They're more Cassiel than Damiel.

The most obvious correlation with Wenders is the vampires' attraction to great music: As they meander through night life, lamenting their bloodthirsty curse, they'll put everything on pause and stick around for a great show (White Hills and Yasmine Hamdan — wow! — taking the spotlight that Wenders has given Nick Cave, Lou Reed, and Sam Phillips). Peter Falk doesn't show up playing himself, alas — oh, I wish he were immortal — but John Hurt's turn as Christopher Marlowe provides a similarly witty twist.

I found Only Lovers to be the perfect late show on a stormy night. It offers the rare luxury of a dreamy stroll through an exquisitely detailed world. I especially love Tilda Swinton here — this is easily my favorite performance of hers. With her wild hair, her penetrating gaze, and her somewhat spooky demeanor, she seems to be doing an Annie Clark (St. Vincent) impression. (Or maybe Clark has been imitating Swinton all this time?) She brings the same distinct mix of beauty, fierce intelligence, and alienating strangeness that causes her to stand out from all other actors working today, but this time there's also a softness and a joy that makes her more sympathetic and enjoyable. She and Hiddleston are a perfect pair. Similarly surprising, Wasikowska is turned loose from her usual uptightness, and gets to be gloriously unhinged — finally!

And the camera has never loved John Hurt's face as much as this camera does. The amazing cinematographer Yorick Le Saux, who filmed Swimming Pool, I Am Love, Arbitrage, and Olivier Assayas' Carlos, finds extravagant beauty in the ruins of Detroit, the exotic back alleys of Tangier, and the fantastic disordered museums of the vampires' living quarters, just as he finds more beauty in the faces of these actors than most movies bother to notice.

I'm inclined to suspect that Only Lovers will be regarded among the "good but not great" Jarmusch films. There are times when I wish the script had given these actors more to discuss, more questions to wrestle, more testimonies of their experiences. I'd like to believe that the vampires (and, thus, Jarmusch) see potential for greater good in humankind than just... you know... good taste. What do they think of human kindness? Are they aware that there is a higher love than that of young lovers making out by moonlight, or music lovers adoring a Gibson guitar? If all of these great books, beautiful musical instruments, and sweet late-night jam sessions don't bring these "true lovers" any lasting consolation, then what good are they, really? Don't these treasures point us toward a sense of cosmic love, a suspicion of some grand design?

As Henry Miller once wrote,

Art is only a means to life, to the life more abundant. It is not in itself the life more abundant. It merely points the way, something which is overlooked not only by the public, but very often by the artist himself. In becoming an end it defeats itself.

I think the richest idea that this film offers, one that Jarmusch only begins to explore, is the idea that bloodshed is necessary for the vampires to know "everlasting life." Isn't it true that those who truly love the world give freely of themselves to sustain the world? In Jarmusch's dark world, vampires survive on blood that others have given up. But in order to enter that world of immortality, they must give up some the blood they call their own. There's something happening here. A sequel could explore this idea further.

Frankly, I'm dreaming of a long-running TV series that follows them from city to city, around the world, learning to live with the zombies that spoil everything, savoring the treasures that remain. In that sense, when the vampires bite in order to "turn" the more promising minds and hearts among the common folk, they are evangelists bringing the blind to the threshold of salvation. They are drawing them toward the world's great lights. Now, if only they would see that those lights are not the source of light, but rather, as Arcade Fire has sung... just reflectors of the light's true source.

Still, while there is little to suggest a religious vision among the vampires, they have a sense of the sacred that the rest of the world has lost. In pursuit of what is beautiful and real, they've taken the road less traveled, and that has made all kinds of difference. Their growing appreciation for all that is best has made it harder to live humbly and patiently among other human beings, but it has also given them a deep love for one another and for what is possible in the world.

What is it in your life that you love that the rest of the world fails to appreciate? Perhaps we can all understand the longings these vampires feel. Perhaps we can "turn" one another toward the light.

•

Hey, Moviegoers: You're Invited to a Secret Seattle Q&A

If you could meet and interrogate your local film critics, free of charge, would you do it?

Yesterday, in a Seattle Pacific University lecture hall, several students had the rare privilege of meeting the legendary film reviewer Richard T. Jameson, editor of Film Comment from 1990-2000.

Candid, funny, and thought-provoking, Richard responded to interview questions from Seattle Pacific film instructor Todd Rendleman. He shared some film history, reflected on the legacy of Roger Ebert, and reminisced about his own personal history of falling in love with movies. He talked about what it takes to pursue film criticism as a vocation, and he taught us Seattleites a thing or two about our own local movie-house history... including the history behind the Edmonds (a charmingly old-fashioned movie theater, one of my favorites).

I was especially pleased by Jameson's words about the need for excellence in film-criticism writing, and everyone laughed as he talked about what it's like to be married to another film critic (the wonderful Kathleen Murphy).

I'll be writing about the event for Response.

Next Thursday, May 8th, it's my turn in the hot seat. Rendleman, author of Rule of Thumb: Roger Ebert at the Movies, will be asking me questions about being a film critic, about being a Christian in the world of film, about Through a Screen Darkly, and... well, actually, I have no idea what he's going to ask me. I'm ready for anything. Bring your own questions.

But here's the thing: You won't yet find anything about this event online, so I'm here to spoil the secret. You're invited!

Come to Seattle Pacific next Thursday, and you'll find us in Room 109 of the Otto Miller Learning Center, at the intersection of 3rd Avenue West and Nickerson, just across the street from SPU's Royal Brougham Pavilion (the athletics building).

CORRECTION: On Tuesday, May 13, "Critics at Work" continues with Seattle film critic and radio personality Robert Horton.