Best Use of Music in a Movie: Share Your Favorites

On Twitter, the poet Amy Newman asked me to share my pick for "Best Use of Music in a Movie."

When a poet as gifted as Amy Newman asks you a question, you answer it.

Few people would be qualified to choose the "best use of music in a movie." I'm certainly not. Neither are any of us, probably. There are just too many movies, too many pieces of music.

But we are qualified to share our favorites. And I'm likely to go on amending this list as I go on thinking about it.

I want to hear from all of you. Don't just name your favorite soundtrack. Name a moment or a scene in which the fusion of imagery and music elevated the experience into something amazing. It could be dramatic or hilarious or mysterious or bizarre. What's a moment in which the music transformed the image, and the image transformed the music?

Here are just a few moments in movies in which music and imagery have fused most memorably for me:

- Three Colors: Blue — The concert for the reunification of Europe (Zbigniew Preisner)

- Three Colors: Blue — The visitations of the blue muse, especially the time that Julie tries to escape by immersing herself in the swimming pool and the music follows her down. (Zbigniew Preisner)

- The Double Life of Veronique — Veronika's last performance (Zbigniew Preisner)

- Raising Arizona — The prologue, "Way Out There" (Carter Burwell)

- The Hudsucker Proxy — Discovery of the hula hoop (Carter Burwell, with a little help from Igor Stravinsky)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ng3XHPdexNM

- 2001: A Space Odyssey — Just about any musical moment.

- The Grand Budapest Hotel — The flight to the monastery by chairlift (Alexandre Desplat)

- Punch-drunk Love — "He Needs Me" (Shelley Duvall)

- Raiders of the Lost Ark — "The Map Room" (John Williams)

http://youtu.be/J_SGlGHF_XQ

- Magnolia — "Wise Up" (Aimee Mann)

- Almost Famous — "Tiny Dancer" (Elton John)

- Midnight Run — The piano blues of Jack's reunion with his ex-wife and daughter (Danny Elfman)

- The Graduate — "The Sound of Silence" (Simon and Garfunkel)

- Apocalypse Now — "The End" (The Doors)

- Watership Down — The ascent, "Climbing the Down" (Angela Morely)

- Toy Story 2 — "When She Loved Me" (Sarah McLachlan)

- The Dark Crystal — "The Funerals" for the Mystic master & emperor; the "Love Theme" during the boat journey (Trevor Jones)

- Once — “Falling Slowly” (Glen Hansard and Marketa Irglova)

- The Royal Tenenbaums — ”She Smiled Sweetly / Ruby Tuesday” (The Rolling Stones)

- U2: Rattle and Hum — "With or Without You" (the finale)

- Just about any musical moment from The Muppet Movie (Paul Williams)

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nhU24xxbnsU

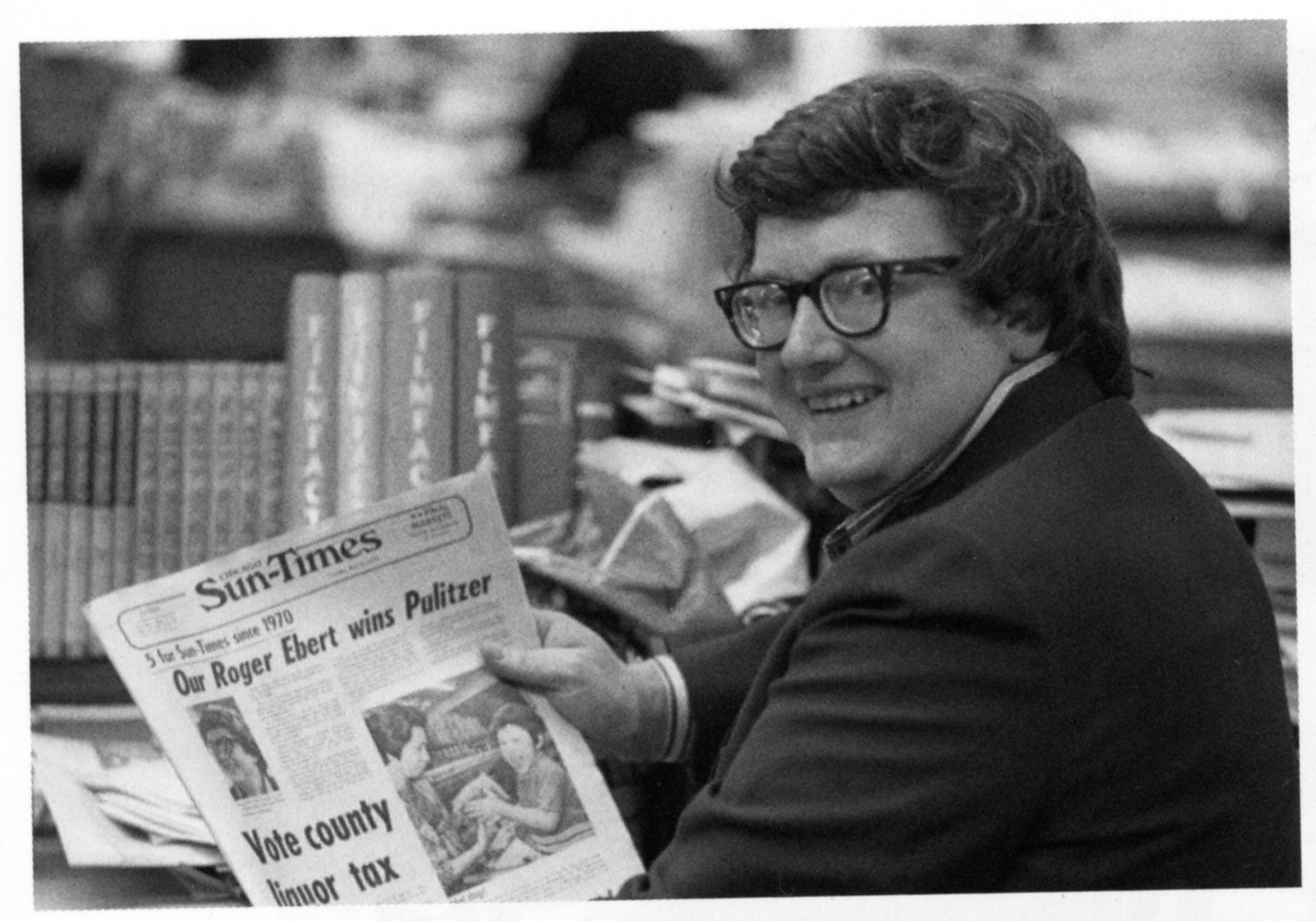

Life Itself (2014): first impressions

"Drama holds a mirror up to life, but needn't reproduce it."

Roger, Roger, Roger. Here I am watching a film about your departure, and I'm still jotting down things you said that will be worth quoting in my own film reviews.

There is a lot to love in this — Steve James' raw, honest, and reverent documentary about the life of Roger Ebert.

Surprisingly, one of the most admirable aspects of the movie is that it is also a revealing, respectful look at the life of your longtime partner and nemesis, Gene Siskel.

I have written in my own film-reviewer's memoir — Through a Screen Darkly — about how much the two of you meant to me in my childhood. I owe you such a huge debt of gratitude. It was fascinating to look behind the scenes at your rise as a journalist, your rigorous standards as an editor, your contentious relationship with Siskel (which brought out the best and worst in both of you), and your inspiring marriage to Chaz. I've been wounded by those self-righteous, judgmental "Christian media" voices that have condemned you for your "worldly" perspectives. Your attention to, and enthusiasm for, excellence, artistry, beauty, and truth have been one of the most instrumental influences in my life, drawing me closer to God and to an apprehension of life that humbles and blesses me.

I have written in my own film-reviewer's memoir — Through a Screen Darkly — about how much the two of you meant to me in my childhood. I owe you such a huge debt of gratitude. It was fascinating to look behind the scenes at your rise as a journalist, your rigorous standards as an editor, your contentious relationship with Siskel (which brought out the best and worst in both of you), and your inspiring marriage to Chaz. I've been wounded by those self-righteous, judgmental "Christian media" voices that have condemned you for your "worldly" perspectives. Your attention to, and enthusiasm for, excellence, artistry, beauty, and truth have been one of the most instrumental influences in my life, drawing me closer to God and to an apprehension of life that humbles and blesses me.

Of the many amazing testimonies and anecdotes offered in this film, I was particularly moved by the words of Martin Scorsese and the testimonies of other filmmakers regarding what it meant for someone to come along and really pay attention to what they had done, to really care about helping audiences see.

And while we're on the subject, Roger: I love Steve James, too; he was the best choice to direct this film. His films Hoop Dreams and Stevie are two of the finest documentaries I have ever seen — they have elevated the art form. I appreciate the clinical honesty he employs throughout this film — honesty that you insisted on.

But something tells me that the movie might have been a greater testimony to your life and your passions if it had been invested with more imagination, and little less focus on your hospital trials, and even fewer of the standard talking-head testimonies. As you yourself once wrote, "A movie is not about what it is about. It is about how it is about it."

Having said that: Roger, you remain one of the ten most influential human beings in my life, and I am grateful for your work. It was a blessing to be invited with Mr. James into your last days and struggles, and to be reminded that, while you were irascible at times, you were more interested in helping us embrace life than in persuading us to be impressed with you.

I suspect that God marveled at your passion, enthusiasm, intellect, and insistence on truthfulness. For good reasons, you had other "names" for God, other ways of engaging God, than most of us. But it seemed to me that this came from your drive for authenticity, and your refusal to let the Wonder and the Mystery be boxed up and exploited the way the Almighty so often is by those who prefer to resolve questions rather than explore them. (Perhaps this has something to do with why Terrence Malick's The Tree of Life and To the Wonder — the film you reviewed last — resonated so powerfully with you.)

Whatever the case, may you rest in God's mercies and know his peace.

•

[Does this review seem familiar? It was first published on Letterboxd. Folks who follow me on Letterboxd often see my first-impression notes and reviews before they're posted here.]

•

Related Posts

- Roger Ebert and Todd Rendleman: An Unexpected Friendship, A Remarkable Memoir

- Thank You, Roger Ebert. Now, Rest in Peace.

- Roger Ebert Remembers “The Last Temptation of Christ”

- Roger Ebert on Redemption

Snowpiercer (2014): A Few First-Impression Notes

Terry Gilliam's Brazil + Jean-Pierre Jeunet's Delicatessen + Peter Weir's The Truman Show + Alfonso Cuaron's Children of Men + John McTiernan's Die Hard.

Terry Gilliam's Brazil + Jean-Pierre Jeunet's Delicatessen + Peter Weir's The Truman Show + Alfonso Cuaron's Children of Men + John McTiernan's Die Hard.

Link those cars together and, wow, what a helter-skelter train!Read more

Boyhood: The Podcast!

It has arrived: The epic podcast conversation about Richard Linklater's Boyhood (and his other films as well).

Featuring:

- Your host, Christ and Pop Culture genius Richard Clark

- Alissa Wilkinson, chief film critic at Christianity Today

- Film reviewer Wade Bearden

- And... me.

To listen, all you need to do is contribute to the worthy cause of CAPC (Christ and Pop Culture).

Get access to this conversation now!

From the Director of "Metropolitan" and "The Last Days of Disco"

Recognize these lines?

You know that Shakespearean admonition, 'To thine own self be true’?

It’s premised on the idea that ‘thine own self’ is something pretty good, being true to which is commendable.

But what if ‘thine own self’ is not so good?

What if it’s pretty bad?

Would it be better in that case not to be true to thine own self?

Critics Vs. Audiences: Whom Shall We Trust?

When I shared some reviews that question the quality of a faith-based film, I received a scornful comment.

So far, I've only received one. I anticipate more, based on experience. But if I only get one, I'll be just fine with that.

The commenter — "M Didaskalos" — read my previous post: "Looking Closer at When the Game Stands Tall."

And here's his response, which I will answer point by point:

Didaskalos:

Gotta love the haughty disdain that pervades so many critics' reviews of When The Game Stands Tall.

Overstreet:

It looks to me like the critics were doing their job: critiquing artistry with skill and professionalism. They pointed out strengths, and they pointed out weaknesses.

If they have some "disdain" for poor artistry, well, isn't that their job?

Our call as reviewers... as audiences... is to push back against sentimentality and mediocrity and propaganda, for the sake of excellence in art — just as doctors are charged with pushing back against cancer for the sake of a healthy human being.

As the sometimes-snarky Flannery O'Connor wrote:

"The fact is that if the writer’s attention is on producing a work of art, a work that is good in itself, he is going to take great pains to control every excess, everything that does not contribute to this central meaning and design. He cannot indulge in sentimentality, in propagandizing, or in pornography and create a work of art, for all these things are excesses. They call attention to themselves and distract from the work as a whole."

As reviewers, then, it is our job to expose anything that weakens the work, and praise anything that strengthens it.

But do go on.

Didaskalos:

On the exalted-arbiter-of-movies website, RottenTomatoes, a scant 18 percent of critics nod approval to [When the Game Stands Tall]. Seventy-seven percent of audience reviews (almost 10,000 vs. the 56 critics' reviews) are approving. http://www.rottentomatoes.com/...

Overstreet:

I may be wrong, but your tone here sounds a little "haughty" and "disdaining." I suppose I could be misreading it.

I'm curious: Do you think that the difference between the critics' rating and the audience rating automatically means the audience is the side that shows integrity?

Food critics tend to have problems with fast-food fare like McDonald's hamburgers. But people love those hamburgers and consume them in mass quantities! To whom should we give the benefit of the doubt? Who is more likely to help us understand whether that meal is good for us?

By the way, a "scant" 20% of critics "nod approval" to Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles on Rotten Tomatoes. But 60% of audience reviews (more than 93,000 vs. the 99 critics reviews) are approving. Should I thus assume that the critics are wrong, and that Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles is an admirable work of art?

The comedy Let's Be Cops has an even lower critical rating: 16% positive. Audiences are 64% positive. Again, are the critics clearly off base?

Let's see what happens when the big-screen adaptation of the famously trashy sex thriller 50 Shades of Gray arrives. Rotten Tomatoes will show you that no critics have reviewed yet... but the film has a 96% enthusiasm rating ("Can't wait to see it!") from audiences. Are you ready to tell me that "audiences" will be more reliable than critics when it comes to that one?

I'm not saying that a critical majority is always right, but it's certainly not as simple as saying, "Well, yeah, but normal moviegoers love it!"

What are critics, by the way?

In my experience, they are the "audience" that is so devoted to the art of cinema that they study it, write about it, and hold artists to a high standard. Their opinions may differ, but they aren't a different species than "audiences." They are just more inclined to distrust a simple, immediate, emotional response. They look closer.

If you're going to go in for surgery, would you entrust yourself to the general public that has some familiarity with the human body, but not a lot of experience in studying and working with the body? Or would you rather entrust yourself to a trained surgeon: someone whose primary focus is the study of, and salvation of, the body?

Didaskalos:

When ordinary (especially Christian ordinary) people do noble things, mundane as their words and acts often are in real life, critics fairly elbow each other out of the way to dismiss another box-office success as "platitudinous," "threadbare," "cliched" or [fill in your own pejorative adjective here].

Overstreet:

I would love to see some examples of what you're saying. I often see critics use those terms... but they're not describing the subject itself. They're describing the way in which the subject is portrayed. I can't remember the last time I saw a critic slam a movie because a character was being noble. No, I see them commenting on the way that it's portrayed. Big difference.

I've seen films about Jesus that deserve to be written off as "platitudinous," "threadbare," and "cliched" ... but that's not a criticism of Jesus. It's a criticism of screenwriting that would earn a B- in a decent screenwriting class, or unimaginative camerawork, or scenes that oversimplify what the Scriptures portray.

Sophie Scholl was a movie about a Christian who stands up for faith and truth — and that film was praised to high heaven by critics. But because it was in a foreign language, and it wasn't given the usual, flashy, entertaining treatment, audiences weren't interested. My favorite film of 2013 — the highly acclaimed independent drama This is Martin Bonner — was about ordinary people wrestling with questions of faith and trying to behave decently toward one another. That, too, was celebrated by almost all reviewers who saw it, but because it didn't look like a flashy Hollywood production, and it didn't have a big-name movie star, it didn't get distributed.

I could list other examples. The point is this: It's not what the characters believe in or do that aggravates critics, usually. It's the artfulness (or lack of it) with which they are portrayed that makes a difference to critics.

Didaskalos:

The real-life coaches whose lives are portrayed in the film seem to be not altogether displeased about WTGST.

[Didaskalos included a long excerpt from this article by Debbie Elias. If you follow the link, you can read the whole thing.]

Overstreet:

No surprise there. People tend to be pleased when the media portrays them in a positive light.

By the way, I looked at the other reviews written by Debbie Elias, who wrote that review of When the Game Stands Tall for The Examiner. I can't say I'm impressed with her discernment about films. Look at her track record. She seems similarly enthusiastic about Sin City: A Dame to Kill For (she gets the title wrong) and The Expendables 3, and, well, almost everything she's reviewed there. That Expendables review doesn't appear to have any actual criticism in it. It sounds more like she asked the film studio, "What would you like me to say?"

Anyway, regarding how the coaches respond to the movie: If I'm looking for insight into the excellence of a portrait, I'm not going to ask the person who posed for it. If I want to understand why Picasso's Blue Guitar is a masterpiece, I'm not going to ask guitarist Jimmy Page. I'm going to ask someone who is gifted in looking closely and interpreting how a work of art means.

I'm only mildly curious about whether people feel like they've been portrayed accurately onscreen. When a great portrait is made of a person, that portrait is just as likely (if not more so) to disturb the subject as please him. I'm suspicious of artists who are concerned about whether or not their subject likes the result.

There's a great story about this told in the lyrics of Bob Dylan's song "Highlands" ... but that's a story for another post.

Didaskalos:

Love, humility, self-effacement, altruism? Well, no wonder so many critics are harrumphing at the movie.

Overstreet:

So, now you're saying that critics, in general, disapprove of virtue.

In my experience, love, humility, self-effacement, and altruism are often celebrated by critics. In fact, the reasons they have such high, demanding standards about artistry is that they believe such things deserve to be portrayed with surpassing excellence, not shoddy craftsmanship.

Critics are, in a way, like car mechanics who examine automobiles for the sake of ensuring excellence, integrity, and safety. That car may be used to transport relief to suffering populations. It might be used to chauffeur the President of the United States. It might belong to a saint or a drug dealer. That doesn't matter. What matters, to the mechanic, is whether or not that car is in excellent working order.

Where the Game Stands Tall may be about fantastic people. All the more reason for critics to care passionately about the quality of the movie that celebrates them. A film that preaches, that sentimentalizes, that oversimplifies... those things deserve to be criticized, no matter the subject, because they harm a work of art.

I haven't read any reviews that condemn the people who inspired the film. I've read reviews by critics who question the artistry of the movie that celebrates them.

You say "haughty disdain." I call it discernment.

When the Game Stands Tall (2013): A Looking Closer Film Forum

When the Game Stands Tall is getting a lot of attention in evangelical Christian culture. Of course it is. It's a match made in evangelical Christian movie heaven: It's about football, and it stars Jim Ca-jeezus.

Evangelical culture loves its Christian celebrities, and few inspire more confidence and enthusiasm from that audience than the handsome professing Christian who suffered so much to play Jesus in Mel Gibson's box office phenomenon.

And evangelical culture also loves sports movies — I suspect because sports stories fit so neatly into the evangelical Christian mindset: that the world can be divided into teams of winners and losers, and that they have the corrective lenses to show the world who the winners really are.

It's a simple formula: Show that winning and losing is fraught with trouble if the game is played for the wrong reasons (for glory, for money, for self-gratification). Then show the athletes learning some Sunday school lessons about humility and teamwork. And once they've learned those lessons, then give the audience the satisfaction of seeing those who are In The Right achieve personal victories (reconciling the family, winning the virtuous but skeptical girl, overcoming the bullies)... and, usually, scoreboard victories as well. By affirming basic Sunday school lessons in a way that congratulates believers as winners, the formula is almost foolproof. It flatters Christians that they're on the Winning Team — and it shows up unbelievers and misbehavers as being on the Losing Team.

It's salvation based on character. It's about ranking people in God's kingdom based on whether or not they believe the right checklist of things and evidence the right checklist of behaviors.

It's tribalism at its best.

Further, it makes promises that the Gospel can't keep... promises the Gospel never made.

Am I saying that When the Game Stands Tall is guilty of these things? No. I haven't seen the movie. But "Christian entertainment" that fits my description has made me skeptical whenever another Faith Plus Sports movie opens... and there are so many of them.

If I sound cynical about the relationship between evangelical culture and sports, it's because I am. I've seen the paradigm of sports used to corrupt Christ's call to humility and servanthood. We are rarely left with the sense that following Christ is an experience of unanswered questions; of difficult faith (which is the assurance of things hoped-for, not achieved; the conviction of things not seen, rather than the conviction of certain triumph); of actual persecution instead of swift resolution; of suffering rather than fleeting difficulties.

This may make it sound like I simply hate sports and shouldn't be writing about a subject I detest.

But it is precisely because of this — that I love the games so much — that I struggle with the way Christian culture so often buys into the problems with, rather than the real glories of, sport.

I've lost almost all patience for televised sports and movies about sports. Chariots of Fire remains a favorite, particularly because of the way it complicates the usual formulas, giving us two very different stories about two different runners, and examining the role that running plays in the lives of its enigmatic runners. What do we think of the runners' motivations? What are we to make of their differing worldviews and religious beliefs? How are we to reconcile these two stories? Chariots of Fire is quite an exception to the rule — a movie with enough ambiguity to give viewers very different experiences. Most sports movies show such a lack of imagination, and such unwillingness to wrestle with questions that don't have obvious answers.

Growing up, I loved striving to master the skills of basketball. I loved the chemistry of generous teamwork, the thrill of executing a beautiful play, the exhilaration that occurs when I team taps into some kind of magical momentum. I loved how the exercise made me feel so alive and awake. I loved the camaraderie that became possible among guys who otherwise had little in common. But many others seem to accept, endorse, and even embrace aspects of sports that poisoned the whole experience for me.

If I were making a film about high school, college, or professional sports, I would not gloss over the questionable aspects of sports culture that athletes and audiences tend to overlook. I would ask viewers to do more than cheer about good virtues and good guys. I'ad ask them to exercise the muscles in our skulls. I'd look closer at:

- how sports culture tends to amplify an unhealthy view of masculinity based on primitive misconceptions of power and the prioritization of warrior glory;

- how it encourages the exploitation of women as sex objects;

- how it makes a "hero" culture out of what really should be a "servant" and "saint"culture (and hero cultures tend to arrive at a certain permissiveness and ethical laziness; heroes are allowed to "get away with stuff" just because they have our favor);

- how the prioritization of glory at any cost leads to disrespect for, and destruction of, the body (especially in football);

- how the commercialization of sports ends up encouraging lifestyles that are the antithesis of teamwork, health, and wholeness;

- how money corrupts the whole enterprise, from outrageous salaries to the excesses of the circuses that tend to surround professional sports events;

- how sports culture glorifies youth, and finds little of value in the experience of aging, so that athletes vanish from the national stage once they are too old to dominate the stage (unless they have enough charisma to become part of the youth-worshipping media machine);

- how "fan spirit" usually devolves into tribalism;

... and I'm just getting started.

Anyway, let's just say I rarely see a film about sports that doesn't throw fuel on the flames of my frustrations and disappointments. They all want to tell us that sports aren't really about winning and losing, but how we play the game... and then the lessons that they do deliver are oversimplified and slogan-like. Further, the climactic moments of the film are often really about winning and losing and sending the audience out on an emotional high.

Sports films are also less than interesting when it comes to cinema. They usually mimic the frantic editing of pro-sports commercials, amplifying and glorifying the bone-jarring impact of physical collision, and framing athletes as if they are gods. They rarely give evidence that the artists have thought about the meaningful art of composition. Nathaniel Hawthorne wrote, "Nobody, I think, ought to read poetry, or look at pictures or statues, who cannot find a great deal more in them than the poet or artist has actually expressed. Their highest merit is suggestiveness." Suggestiveness is the thing I find most lacking in sports films. If you can think of good examples to the contrary, by all means, share them! I'd be hard-pressed to think of a sports-related film that doesn't deliver more of what the audience wants than what it needs, and that's because sports culture tends to do the same thing.

So it comes as no surprise that the reviews for When the Game Stands Tall fail to intrigue me.

And these reviews, from some of the critics I regularly follow, do little to persuade me otherwise.

Susan Wloszczyna for RogerEbert.com:

To fully understand what’s in store in the real-life football parable “When the Game Stands Tall,” it’s probably good to know that star Jim Caviezel’s most noteworthy film role was as Jesus in “The Passion of the Christ.” Turns out his ability to preach and sway his disciples comes in pretty handy as Bob Ladouceur ... ... His approach to the game, one that he has given most of his life to, is perhaps best summed up in a quotation from Matthew 23:13 that is recited onscreen: “Whoever exalts himself shall be humbled. And whoever humbles himself shall be exalted.” In other words, it is not about you, it is about others. All these sentiments are worthwhile, of course. And considering that De La Salle is a Catholic school and Coach Lad also was a religious studies teacher, they aren’t gratuitous. Still, most often in its early stages, the melodrama onscreen edges precipitously close to dissolving into a puddle of platitudinous pabulum served in the manner of a rote Sunday school lesson.

Steven Greydanus for The National Catholic Register writes:

... the paradox at the heart of the sports-movie genre is that the game is its raison d’etre, yet most sports movies want to be about more than just the game. ... Like many movie coaches, Bob is so committed to his work that he neglects his family, at least until a life-threatening crisis forces him to step back from coaching for a while. Then he has a moral epiphany: He has been a lousy husband and father. Perhaps if he’d ever watched any sports movies, he might have seen that coming. ... The film insists that there’s more to life than football. Yet the players urgently tell one another, not only at the outset, but even at the climax, “No matter where we go or what we achieve, nothing is going to come close to what we have here.” The idea of life climaxing at high school is depressing enough; more importantly, it undermines the movie’s bid for larger themes.

Scott Tobias for The Dissolve writes:

... while discipline and self-control certainly figure into Ladouceur’s teachings, there’s also a passion and drive that’s totally absent from Caviezel’s performance. It’s not that the film needs any more goosing — it’s broad and shameless even by inspirational-sports-movie standards—but its basic lack of plausibility starts with him. ... When The Game Stands Tall mostly sticks to the idea that moral character and determination, rather than talent and tactics (and scheduling), explain why Ladouceur and De La Salle succeeded on such an unprecedented scale. That strain of magical thinking is a curse to sports—and to movies about them, too.

But Mark Moring, who was my editor for several years when I wrote reviews for Christianity Today, stands up for the film:

... this is no mere cheesy Christian movie with an “evangelistic agenda.” It’s a very good inspirational sports movie reminiscent of those that Disney has done so well — like Remember the Titans (2000), The Rookie (2002), Miracle (2004), Invincible (2006), Secretariat (2010), and this year’s Million Dollar Arm. Part of what made all of those films so enjoyable was knowing that they’re true.

•

If you appreciate this post and enjoy Jeffrey's work exploring the territory where art, faith, and culture intersect, you're invited to "Put Your Name in the Credits." Cast your vote for "Keep Looking Closer Alive." Make a donation. Offer whatever you feel moved to contribute. All donations will be applied directly to that materials, events, and experiences that make the blog happen. That's a Looking Closer promise.

The Flood Hits Home Video: Give Noah a Chance

Here comes the flood. Again.

Since Darren Aronofsky's surprisingly (and maddeningly) controversial film Noah — starring Russell Crowe, Jennifer Connelly, and Emma Watson — has finally arrived on home video (video on demand, streaming, blu-ray, and DVD), let me point you to my own review and the best reviews of the film I have come across to date.

I encourage you to see it... especially since there's a flood of new Biblical epics coming our way, and it'll be good to compare, contrast, explore, and discuss them.

Read My Review of Noah

Look Closer at Noah

A commentary and a variety of notable reviews by some of my favorite film-lovers.

Listen to a Kindling Muse Podcast Discussion of Noah

Featuring Dr. Jeff Keuss, Dr. Christine Chaney, Jenny Spohr... and me.

Who Among Us Is Thirsty? — A Reflection on the Loss of Robin Williams

I am sick at heart over the loss of one of my favorite imaginations.

The great Robin Williams struggled, seeking healing and help, for many years, in rehab and — according to a close friend of mine — in church.

His great performances — The Fisher King, Good Morning Vietnam, Insomnia, Good Will Hunting, The Adventures of Baron Munchausen, Awakenings — are among my all-time favorites in cinema. Even his cameo appearances were often something to treasure. (Think of Dead Again or Deconstructing Harry.)

Costumed as Mork from Ork, he was on the cover of the first magazine I read as a child: an issue of Hot Dog! Soon after that, I eagerly opened an issue of Dynamite, which featured an interview. I can't remember which of those two magazines it was − I was only 8 or 9 at the time − but one of them included an interview in which Williams talked about freedom of the imagination in a way that made a huge impression on me. He spoke of how his parents would buy him die cast model kits, and he would go home, open them up, mix up all of their pieces, and then build contraptions born of his own wild imagination.

Costumed as Mork from Ork, he was on the cover of the first magazine I read as a child: an issue of Hot Dog! Soon after that, I eagerly opened an issue of Dynamite, which featured an interview. I can't remember which of those two magazines it was − I was only 8 or 9 at the time − but one of them included an interview in which Williams talked about freedom of the imagination in a way that made a huge impression on me. He spoke of how his parents would buy him die cast model kits, and he would go home, open them up, mix up all of their pieces, and then build contraptions born of his own wild imagination.

That method translated well to his frenetic, surprising, wildly unpredictable comic style. Nobody could improvise like Williams.

But it was probably more than just imagination. His energy and uninhibited flamboyance were probably enhanced — in a way similar to steroids — by substance abuse. Moreover, his ability to fling himself beyond the bounds of our own imaginations was very likely driven by pain, by a compulsion to escape (or at least deny) a roiling sadness, fear, and suffering that was still waiting for him when he landed.

For better or worse, he made magnificent art out of wrestling darkness.

I could write a book on what his characters have meant to me. He made good movies great, and mediocre movies worth watching. I didn't care for Spielberg's Hook, but I loved Williams's in it. Williams's remarkable restraint was the most interesting thing in Awakenings. And while I cringed at how Mr. Keating in Dead Poet's Society spurred his young students toward recklessness instead of maturity, Williams did a wonderful job of inspiring a love for the communal celebration of art, and that inspired me to begin a reading group that continues in my community almost 25 years later.

But it's The Fisher King that means the most to me. His performance as Parry moved me so deeply that I wrote about him in my moviegoing memoir, Through a Screen Darkly. And I was delighted to write a brief celebration of the film for Arts and Faith's "Top 25 Divine Comedies." In Terry Gilliam's inspired masterpiece, Williams found the heart of a man who could be a fool, a clown, a dreamer, a lover, a grieving widower, a poet, an inventor, a dancer, and a Knight of the Round Table. He careened between seemingly impossible hopes and seemingly irreparable damage. With every Tasmanian-Devil flourish, he led us to suspect that this was not just a storyteller's invention, but an actor revealing things about his own stumbling progress through life.

And the stumble from which Williams cannot recover on his own... that stumble has me wondering. I know some lively, hilarious, flamboyant people. How much of their wild charisma comes from a deep need to be loved, or a compulsion to escape their darkness? Who among my friends and acquaintances might be feeling what Williams felt — a similar sense of weakness, oppression, or hopelessness? Who within my reach might be thirsty for a word of tenderness and care, for help in a time of fragility and perceived failure?

I could let those questions hang in the air: Typical generalizations that turn this post into a chance for me to sound conscientious and big-hearted.

But that wouldn't be the truth.

•

Last night, as I drove home from work, I listened to the NPR tribute to Robin William's legacy, and there were tears on my face. They were genuine tears. I love what Williams gave the world.

When I arrived at home, I sat on the couch and shared the news with Anne, who was shocked and saddened like most of us.

And in those moments of sorrow, there was a knock at our front door.

I opened the door to find an anxious, red-faced man with matted blonde hair and a sticky mustache. He was holding buckets, a spray bottle, and a long-handled squeegee. If William Sanderson — the actor who played Larry on the TV show Newhart and android designer J. F. Sebastian in Blade Runner — had played one of the homeless men alongside Robin Williams in The Fisher King, he would have looked just like this.

The stranger said, "I hope I'm not bothering you, sir, but may I help you out by washing your windows?"

We are not used to interruptions like this at all. But this fellow had been to our door two weeks earlier asking the same question. And I immediately reminded him, "Sir, I'm sorry, but as I told you last time, this house is a rental, and any work done on the house needs to be approved by our landlords."

Even before I finished saying this, he recoiled a step as if I'd pushed him. He blinked fitfully and looked away down the street, saying, "I'm so sorry, sir. I'm so sorry. You're right. I forgot about that, sir. There's just so many houses in this neighborhood, I don't remember everything. I'm sorry. I won't bother you again."

And he was gone. He was gone very quickly.

I sat back down with Anne. And a moment later I felt a great pressure, as if a storm front had suddenly overcome our house. I tasted the sharp edge of the way I had spoken, felt my throat go dry. All I could fumblingly say to Anne, "I was too hard on that guy."

"Maybe we could give him some food," she said. "He's just hoping to earn some money, right? He's probably hungry."

I felt even more ashamed. Anne was a few steps ahead of me, thinking of ways to help the stranger.

I am not making any of this up. And what's more — at the time, I was completely blind to the stark contrast between my distress over Robin Williams's loneliness and despair and my attitude toward the man who had knocked on my door.

Now, it seems like the farthest thing from coincidental timing.

We went out the front door to call after him, but he was gone. We got in the car and drove around the neighborhood.

And by God's grace, we found him.

He was walking along, door to door, with the stride of a character that Robin Williams might have played: a broken man, someone who has lost what once held him together, a Don Quixote charging at windmills with a sponge on a stick, a weary soldier staggering along in a desperate search for a Holy Grail.

I approached him and apologized for being curt with him. He quickly waved his hands and told me that I'd done nothing wrong. He was far more gracious than me. Feeling awkward and unhelpful, I handed him a carton full of the pizza we would have eaten for dinner, which he immediately accepted. I gave him some money for bus fare. And he did not make any requests. He was grateful, and he moved on, looking for a way to share what he had to give in hopes of receiving something... just a little grace... in return.

This did nothing to make me feel better. I still feel like a fool. It wasn't enough. Too little, too late. Even after that sharp jolt of shame and my fumbling recovery effort, I feel that I showed only the barest trace of care for that stranger.

I didn't ask if he would like to join us for church on Sunday morning, where he might have met others who could introduce him to far more useful resources.

I didn't even ask his name.

In that exchange, I was the one with the most missing pieces.

•

So who am I to ask why Robin Williams succumbed, in one minute of one hour of one difficult day, to hopelessness?

If a man with a loving wife, with children he cherished, with adoring fans all over the world — with all of these advantages that many of us covet, thinking they would solve our problems — can still stumble into the abyss during an hour of hopelessness, then I am probably surrounded by people who are teetering on that precipice every day. For I can see so many struggling with depression, addiction, regrets, and private shame... and most of them lack those advantages. Like the man on my doorstep, they don't have family or a home. They can't do a commercial and make a quick thousand bucks. They cannot fix what the world has broken within them. And they have no inclination to call out for a loving God because they do not see evidence of any such thing in the people he created... especially me.

No, it wouldn't be appropriate to beat myself up about how I failed the man who knocked on my door. That would be, in a way, egocentric and unmerciful. We all fail one another on a daily basis. We can all do better.

I know I'm not capable of being anybody's savior, but I can unfold the map of my experience and point to places of grace, places to which others have led me. I want to invite anyone who is thirsty to come back with me to places where I have found living water. The wells. The rivers. The oceans. In nature. In art. In community. In Christ.

I want to be more vigilant. I want my friends to know that they can talk to me if they need a listening ear. I don't want to be too busy for them. I don't want to hear myself speaking shallow assurances. I don't want to assume that somebody else is taking care of things. And I don't want to pretend that I have all the answers. (If I had all the answers, I wouldn't need any faith. I want to love. To suffer alongside. To echo others' demands for understanding. To cooperate in an upward climb towards hope.

And yet I know from experience that sometimes even a lavish show of love and grace is not enough for us to save each other from our weaknesses, diseases, and darkness. Sometimes the head, the heart, and the delicate internal compasses are too broken and we cannot find our way to the truth. That yawning abyss around which Robin Williams desperately danced... there, but for the grace of God, go you. Go I.

Even so: The darkness is weaker than the light. Even if it swallows us up. Because the light, too, was swallowed up. Remember? When you're down, the light is down there with you. You cannot fall from its reach.

On his album "Civilians," Joe Henry sings words that have haunted me since I first heard them, words of incredible consolation and hope:

We're taught to love the worst of us

and mercy more than life

but trust me...

mercy's just a warning shot across the bow.

I live for yours

And you can't fail me now.

Something in my heart resonates with these lines. I believe them to be true. I believe that God's grace is great enough to overpower our own failures, and that love surpasses our capacity to imagine it. There is nowhere we can go that Christ has not gone before us, nowhere so far that our cries for him will not be heard by his mercy.

In closing, I'd ask that you watch this clip from my favorite Terry Gilliam film... and my favorite Williams performance. Two of my friends posted it online within minutes of the breaking news, and I'm grateful, for it remains one of my favorite scenes from a lifetime of moviegoing. It resonates because the character, Parry, a poor and troubled soul who is searching for the Holy Grail, finds consolation in a story that is greater than himself, a story that may have given consolation to Williams during dark nights. I cannot imagine that those words, once memorized, ever stopped echoing in Williams's mind, even if they were, in the midst of a crisis, momentarily drowned out by the voice of despair.

May God forgive all of us for our moments of failure, and grant all of us the mercy and peace that our hearts so desire.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wN3bcE7ldHg

Lucy (2014) : A Looking Closer Film Forum

"I have a confession to make," said a former professor of mine when we sat down to talk over lunch.

He looked genuinely troubled.

"Okay," I said, a bit anxious, stirring the ice cubes in my tea.

He ran his fingers through his hair until it stood up straight. He glowered down at the shrimp in his stir fry. He sighed and said...

"I went and and saw Lucy."Read more