Looking Closer at Terrence Malick's Knight of Cups

[This post will be updated with more reviews and excerpts as I discover them.]

Terrence Malick's Knight of Cups screened at Berlinale today.

And since Looking Closer readers have, historically, been more excited about and more interested in Malick than any other director, it's worth paying attention.

Here come the reviews...

1.

Slant (Fujishima)

With Knight of Cups, Terrence Malick achieves the sense of stylistic ossification that many accused his last feature, To the Wonder, of embodying. The difference is that the earlier film was still, in its own rather elemental ways, tied to actual flesh-and-blood characters on screen. In Knight of Cups, by contrast, Malick seems to have finally decided to do away with humans altogether. In some ways, this is the filmmaker's 8 ½: a feature-length riff on his own creative frustration, with Christian Bale as his directionless stand-in, a screenwriter suffering from spiritual ennui. But then, of course he's bored and frustrated: He lives in Hollywood, after all, and if works like The Day of the Locust and The Player have shown us anything over the years, what else is Hollywood but a cesspool of decadence and empty hedonism?

2.

Variety (Chang)

Malick remains concerned almost entirely with interior states; with the spiritual connections that are forged and ruptured between individuals; and with the grim consequences of a life lived in continual exposure to the world and its most corrupt elements. (In that respect, one movie it clearly recalls is Sofia Coppola’s “Somewhere,” another example of an auteur employing a highly specific, image-driven cinematic language to explore celebrity ennui.) It’s a moralistic stance that may in and of itself cause certain viewers to recoil, particularly when Dennehy’s earnest, prayerful father figure and Armin Mueller-Stahl as a grave-looking priest are on hand to nudge Rick back toward the straight and narrow.

Those tarot references aside, Malick’s view remains a deeply and unapologetically Christian one; Rick’s story may echo that of the lost knight, but it also has obvious roots in the parable of the prodigal son, and throughout “Knight of Cups” you can just about make out the voice of a father patiently, insistently calling his wayward child home. It’s that instinctive compassion that keeps the film from turning crushingly didactic, along with the myriad aesthetic pleasures afforded by the Malick’s typically dense layering of image, sound and music.

3.

indieWire (Jessica Klang)

Those of us who had hoped that "Knight of Cups" might see Malick changing tack a bit after the progressive steps toward a far-off horizon that were "The Tree of Life" (which, if you're wondering, I loved) and "To The Wonder" (which I did not) are bound for disappointment, as his new film finds him more abstruse than ever, and more involved with existential questions which are beautiful, vital, universal, and also completely unanswerable.

4.

Movie Mezzanine (Michael Pattison)

With vacant eyes and mouth agape, man continues his seemingly irrevocable fall from innocence, in Terrence Malick’s eternally juvenile seventh feature Knight of Cups.

...

Indeed, Malick takes the kind of dramatic displacement that he so dangerously let free in To the Wonder to another level entirely here, dragging what scant storyline there is by the scruff of its reluctant neck, capturing some startling images along the way as he allows platonic ideals to stand in for the real thing. Beautiful women on balconies and on beaches; a self-suffering protagonist; declining marriages and tension-fuelled familial relationships. As one character claims late on in this folly, “no one cares about reality anymore.” The obvious refrain to which, of course, is “speak for yourself.”

5.

indieWire (Eric Kohn)

Still, there's something inspiring about the take-no-prisoners approach of Malick's cosmic vision, which follows its own path. In the context of a story about the restrictions of commercially-mandated filmmaking, it may be the closest we get to a mission statement in the elusive director's career.

But even if one goes with the flow and embraces its underlying thematic focus, "Knight of Cups" falls short of sustaining a coherent stance. While its formalism resembles "To the Wonder" and "The Tree of Life," it lacks their singular focus. By distilling his appeal to its most rudimentary elements, Malick regularly lingers on the cusp of self-parody. Rick's struggle has its moments of magical splendor, but just as frequently feels as hazy as the diminished memory of that fabled knight.

6.

Hollywood Reporter (Todd McCarthy)

Having swung so far out of orbit on To the Wonder to have been sucked into a creative black hole,Terrence Malick makes it about half-way back to terra firma with Knight of Cups. A resolutely poetic and impressionist film about creative paralysis, indecision, father and sons, female muses and life slipping away as surely as water down a river, the seventh feature from this takes-his-time writer-director is far more partial to free association and stream-of-consciousness notations than to conventional storytelling. The upshot is a certain tedium and repetitiveness along with the rhythmic niceties and imaginative riffs. But whereas his last work of real weight, The Tree of Life, achieved rarified moments of emotional and lyrical expressiveness, this one mostly operates on a more dramatically mundane, private and even narcissistic level.

7.

The Guardian (Peter Bradshaw)

With his latest film Knight of Cups, however, Malick has frankly declined. There are moments of visual brilliance here, moments of reverence and even grandeur. He is always distinctive, and anything he does must be of interest. But his style is stagnating into mannerism, cliche and self-parody. Where once he used his transcendant visual language to evoke heartland America, these tropes are now exposed in being applied to tiresome tinseltown LA, where a screenwriter played by Christian Bale undergoes what has to be the least interesting spiritual crisis in history.

8.

Little White Lies (Sophie Monks Kaufman)

Knight of Cups is glistening pearl from Terrence Malick is a blissful, transcendent and desolate treatise on love.

The most anticipated film of Berlinale 2015 looks set to be the best one. It’s hard to imagine equivalent notes of grace and meaning being struck in this competition or indeed in this world. Grace and meaning are not new adjectives for describing the work of writer/director Terrence Malick but, gratifyingly, this time his distinctive poetic cinema encases a simple and coherent narrative. Existentialism from a rich playboy makes it tonally comparable to Paolo Sorrentino’s The Great Beauty but this also an absorbing study of the stresses of being a womaniser. Really.

...

Malick doesn’t judge his lead man for his elegantly wasted lifestyle. The whispered voice-over that – to the amusement of detractors and scintillation of devotees – has become Malick’s failsafe way of evoking higher consciousness has never been more exquisite, repeatedly finding the barest way to communicate the anguish and complexities of the human spirit.

9.

Fandor Daily (David Hudson)

The wispiness and the whispered voiceover (ranging again from snippets of dialogue to prayer-like calls out into the cosmos; my favorite: “Ah, life.”), but most of all, the sheer repetition become, all too soon for this viewer, overbearing. When the credits rolled, all I could think was, “Thank God it’s over.” Rumor has it that the film Malick shot all but simultaneously with Knight of Cups, the one set in Austin’s music scene, will likely premiere at Cannes in May. I sincerely hope that the fresh milieu will rejuvenate the imagination of one our greatest living filmmakers.

As It Is In Heaven (2014)

I will not mention Terrence Malick when I review As It Is In Heaven. I will not mention Terrence Malick when I review As It Is In Heaven. I will not mention Terrence Malick when I review As It Is In Heaven. I will not...

Oh, forget it.

To reference Terrence Malick in reviews of films about faith is becoming as common as referencing Flannery O'Connor in reviews of Southern fiction. But that's the power of an artist's vision: Malick and O'Connor both sought to reflect hard truths without flinching. Both sought to find hope by marching through — instead of around — the darkness. And in doing so, they spoke to an audience that knew darkness and was thirsty for something meaningful. They presented a picture of faith in which there were actual stakes. Both refused to accept the vocabulary of their medium, and instead expanded it, showing us things we've never seen before, taking risks to convey beauty and truth in new ways. And in doing so, they did something far better than "send messages" — they captured imaginations.

To reference Terrence Malick in reviews of films about faith is becoming as common as referencing Flannery O'Connor in reviews of Southern fiction. But that's the power of an artist's vision: Malick and O'Connor both sought to reflect hard truths without flinching. Both sought to find hope by marching through — instead of around — the darkness. And in doing so, they spoke to an audience that knew darkness and was thirsty for something meaningful. They presented a picture of faith in which there were actual stakes. Both refused to accept the vocabulary of their medium, and instead expanded it, showing us things we've never seen before, taking risks to convey beauty and truth in new ways. And in doing so, they did something far better than "send messages" — they captured imaginations.

Now, their artistic descendants are embracing and expanding those vocabularies.

What's more — the best of them are going beyond imitation, and demonstrating that they have attended to and absorbed the visions and innovations of other great masters.

In the case of Joshua Overbay, the director of As It Is In Heaven, we have a unique debut that may remind audiences not only of Malick but also of Robert Bresson, Ingmar Bergman, and more recent visionaries like Jeff Nichols (Shotgun Stories, Take Shelter, Mud).

So forgive me but, yes — As It Is In Heaven, shot by Isaac Pletcher, looks a lot like a Terrence Malick film in its haunting opening shots of a woman in a white gown moving through Edenic environs toward a river where a baptism is underway.

So forgive me but, yes — As It Is In Heaven, shot by Isaac Pletcher, looks a lot like a Terrence Malick film in its haunting opening shots of a woman in a white gown moving through Edenic environs toward a river where a baptism is underway.

Behold: A kindly older man they call "The Prophet" (John Lina) is baptizing a newcomer (Chris Nelson). Around him, the followers in this Kentucky church (cult?) rejoice at the salvation of another soul. Their community is growing.

Communities of faith tend to grow bolder and more secure in their beliefs when their numbers increase. (How many pastors take congregational growth as assurance of God's blessing and approval?) In this case, the community needs assurances. They follow a leader who sees this small sect as distinct from the rest of the church. They want to believe that they are special, that they have found the answer. They want to believe that if they obey this man, they will be delivered from a world that has hurt them, let them down, and sent them in search of an escape.

The day of reckoning, says the Prophet, is very close.

Well, he's right about that. A day of reckoning is coming. But not the way he thinks it is.

In a turn of events so portentous that you might even call them "Biblical," the heir apparent — Eamon (Luke Beavers), the Prophet's only son — is passed over for this humble, reluctant stranger. The one who has been given the rather loaded name of "David."

David seems earnest, eager to prepare the people. He wants to see them purified from sin so they will be worthy of redemption — an idea that anyone familiar with the Gospel will recognize as, well... the opposite of Jesus's teachings, and rather like the teaching of those Jesus most firmly rebuked.

What's remarkable is that all of these characters live within the cult. We're not given an outsider's perspective that will make us feel comfortable. We come to care about these people, and our hopes rest on anything that draws any of them closer to freedom, closer to truth. What's more, we get a sense that each one has suffered some kind of alienation or severe loneliness — lacking a family or community or a sense of purpose. No wonder they might be drawn to this ready-made family, community, and purpose.

(I wonder — How often do we stop to consider what might lead other communities around the world to unite beneath the banner of some fanatical ideology? It's so much easier just to say "They believe the wrong thing, and thus they deserve our condemnation." Perhaps if we were stronger exemplars of our own beliefs, and showed the rewards of it to our neighbors, they would not seize upon such misguided causes, such communities where they can find a sense of belonging. But that's a subject for another time.)

I'm tempted to argue that the cult itself just doesn't seem very plausible. What kind of people would entrust their lives to such a mercurial, self-proclaimed "prophet"? But I watch the news. And I hear the stories. I know a lot of people who have been rattled by the collapse of a major church right here in Seattle, a church that placed far too much authority and power in the hands of one man, a man whose good intentions were not enough to make up for his misguided and legalistic ideas. Most people I know stood around saying "Why can't these congregants see where their choices are leading them?" But that sense of satisfaction that comes from belonging to the right team, from being assured that the Right Man is doing the thinking for you, from believing that any kind of questioning or criticism is an attack... that will steer you away from the Gospel every time.

What's more: The larger a cult becomes, the more persuasive and compelling their collective affirmation of a false prophet becomes. Who's likely to volunteer as a nay-sayer when a barn full (or a sanctuary full) of congregants are cheering for their pastor?

What's more: The larger a cult becomes, the more persuasive and compelling their collective affirmation of a false prophet becomes. Who's likely to volunteer as a nay-sayer when a barn full (or a sanctuary full) of congregants are cheering for their pastor?

It would have been easy to villainize David — to make him seem insane or malevolent. The film is far more troubling because we can see David's eagerness to be a good leader. We can see him leaning into prayer and intuition for guidance. Oh, what a little theological guidance could do for him. Oh, what a close reading of the gospels would reveal. (If you want to argue for the importance of Biblical literacy, show people this movie.)

So, seeing David's naivete and the burden of responsibility, we're afraid for him as his followers distrust him and question his claim of authority. But we're afraid most for those followers who have so much to lose if they are led any farther astray. Viewers won't forget Deb (Shannon Kathleen Baker), the mother of an infant who is commanded to deny her baby nourishment during a cult-wide fast in the name of holiness.

It would have been easy to write this off as a story of "crazy Southerners." But Overbay is careful to make the cultists seem as if they might have come from anywhere. (As he points out in this revealing interview with Alissa Wilkinson at Christianity Today, you won't notice Southern accents in the cult.) That makes this group seem like it might be just about anywhere, around the corner.

The film stands as a convenient refutation of the common cliche "All religions are the same." Perhaps you remember that moment in The Polar Express when the conductor said, "The thing about trains... it doesn't matter where they're going. What matters is deciding to get on." Yeah, that sounded nice, but it's total b.s. It matters very much which train you climb on. Because trains will take you in different directions, to different destinations, on different tracks. You know how that inspiring song goes: "People get ready, there's a train comin', pickin' up passengers coast to coast... And faith is the key!" Ah, but faith in what? In whom?

Does this train exist under the tyranny of law, where you must earn your salvation with good behavior? It's a seductive idea, this notion of earning your place on a Gospel train by following the rules of the conductor. And it's an exciting thing for a lonely, lost soul to surrender freewill, or to learn a code, in order to purchase the embrace of a community called "The Chosen" in Jesus's name. It's even more exciting if you're assured salvation for your behavior.

Here's a hint: If you find that your train's conductor

- claims to get "words from the Lord" that directly contradict Jesus's teaching,

- casts off the good news of God's unconditional love and grace for a new rule of law that makes him the judge of who's "chosen" and who isn't,

- sets himself up as "the shepherd" and the sole arbiter of truth,

- isolates the community from outside connections,

- teaches that God will "leave the earth to rot," and

- interprets people's hardships as evidence that they're hiding secret sins ...

... you're probably on the wrong train.

I prefer a vision of the Gospel I stumbled onto in Joe Henry's Invisible Hour:

There’s a train already come,

There’s a train already come,

Her hands are birds, her heart a drum —

Lo these many years...

In other words The Kingdom of God is at hand. Don't feel like you need to go find it. It is, as Jesus said, within you.

It may surprise some viewers to learn that there were many Christians instrumental in the making of this film. It was directed by Joshua Overbay, written by him and his wife Ginny Lee Overbay, with the support of students from a Christian school — Asbury University. And I offer them my sincere congratulations. They have refused to take the path of so-called "Christian movies" — that growing industry of movies characterized by zealous evangelism, propaganda, and (alas) a destructively dualistic view of the world.

Most films that get branded as "Christian" demonstrate a fundamental misunderstanding of how art works and what it is for. But these filmmakers? Although many of them are Christians, they show no eagerness to make a "Christian Movie" — that is, a film designed to persuade viewers to become members of a particular team. Rather, they have employed imagination and excellence in carefully composed images and a subtly crafted narrative that respects viewers' intelligence. By inviting us into an experience rather than subjecting us to an illustrated sermon, and by demonstrating compassion for all of their characters rather than setting up a false dichotomy of "good guys" and "bad guys," they create a space for encounters with beauty, mystery, and truth, where all kinds of good contemplation and revelation can occur.

Think of the countless hours of tedious work invested in the typical CGI-drenched Hollywood blockbuster. Then consider that this suspenseful film was shot without any special effects over the course of 17 days. This is powerful filmmaking, admirable for the resourcefulness of the artists. There is no substitute for the power of actual human beings, the actual rhythms of human relationships and dialogue, the power of silence, and the influence of actual environments in front of a camera.

Think of the countless hours of tedious work invested in the typical CGI-drenched Hollywood blockbuster. Then consider that this suspenseful film was shot without any special effects over the course of 17 days. This is powerful filmmaking, admirable for the resourcefulness of the artists. There is no substitute for the power of actual human beings, the actual rhythms of human relationships and dialogue, the power of silence, and the influence of actual environments in front of a camera.

I'm tempted to say that these filmmakers have asked us to consider how prone human beings are to desire a different Christ than the one we we've been given, and to reconsider what the claims of the Gospel might actually be. But no — that's just what I find myself thinking about. The movie makes no move to preach or proselytize. Instead, it shows a path that moves in the wrong direction, so that the audience senses the deepening shadows, feels the disorientation that comes when we lose track of the sun's true position in the sky.

In that sense, I'm tempted to say that As It Is In Heaven may have been influenced by, of all things, The Blair Witch Project. Just as that film limited our vision to what one wanderer's handheld camera showed, cursing us to constant claustrophobia and motion-sickness in a maddeningly endless forest, so As It Is In Heaven gives in us an increasing sense of vertigo by closing us in — psychologically, communally, and spiritually.

If I have any trouble with the film at all, it's that I suspect that life within cults is actually less stifling than this — that they discuss more than just their charismatic leader, that they talk about where they came from, what they miss, what about the world outside they might still love and covet. (I'm grateful to an insightful colleague who found the right words for this.) These characters might have come to life even more fully if the film had given us a fuller sense of their histories and interests.

But that's quibbling. Watching As It Is In Heaven, I was never less than enthralled. As bizarre as the scenario might seem at first, it's happening in all kinds of ways all around us. And if we're not vigilant, it's happening to us as well — in how we allow ourselves to be carried away by the charisma, the flattery, the promises, and visions of appealing figures like patriarchs, pop stars, pastors, presidents, CEOs, and even technological devices.

By asking these good-hearted but misguided people to make incredible sacrifices for his incomplete vision — and by limiting their environment to the houses, barns, and woods they've made the base of their separatist activities — the Prophet has doomed them all.

•

As It Is In Heaven is now streaming on iTunes and Vudu.

•

Looking Elsewhere

Michael Leary at Filmwell:

If Overbay can produce something so accomplished (truly, this film is marked by Overbay’s sense of nuance and precision) with so little, I am excited to see what he could put together with a bigger budget.

And I am not sure to what extent Overbay would agree, but this is Christian art in a clear, engaging, and historic sense. At times the film feels like a religious faith wrestling with its own object.

Wade Bearden at 1MoreFilmBlog:

The fact that Joshua and Ginny Lee Overbay have crafted a film that nourishes the mind and aesthetic sense of believer and atheist alike redounds to their credit. Here’s hoping the Overbays resist the temptation to pander to a niche market in subsequent films, and continue to create artful, broadly appealing movies.

Discover The Chrysostom Society: Meet Editor and Book Enthusiast John Wilson

In the early days, they plotted how to kill each other.

That may sound like unseemly behavior for a group of celebrated Christian writers. But you can read all about the murderous conspiracies of The Chrysostom Society in their first collaborative literary effort: Carnage at Christhaven. It’s a serial murder mystery — satirical, smart, and subversive — each grisly chapter contributed by a different society member. (It was first published in 1989.)

That may sound like unseemly behavior for a group of celebrated Christian writers. But you can read all about the murderous conspiracies of The Chrysostom Society in their first collaborative literary effort: Carnage at Christhaven. It’s a serial murder mystery — satirical, smart, and subversive — each grisly chapter contributed by a different society member. (It was first published in 1989.)

None of them, not even the writers themselves, were safe within those pages. (Even inspirational Christian writer and Society member Philip Yancey turns up dead.)

Whatever one thinks of this book, this enterprising fellowship of writers can’t be accused of taking themselves too seriously.

Read all about their strange history here, at the Society's worldwide web headquarters.

I'd recommend any of their collaborative books, which you can browse here.

My current favorite is A Syllable of Water, in which Robert Siegel, John Leax, Scott Cairns, Luci Shaw, Erin McGraw, Virginia Stem Owens, Emilie Griffin, Jeanne Murray Walker, Philip Yancey, and more share advice for writers of all different genres. This is the first book I require students to order when I teach creative writing.

I've been enjoying the Chrysostom Society's writing since high school, when my father gave me a treasure of a book called Reality and the Vision. (It's been republished under another title: More Than Words.) In it, authors like Madeleine L'Engle, Stephen Lawhead, Luci Shaw, Philip Yancey, and Walter Wangerin Jr. write about their favorite writers.

I never dreamed that I would someday, through a spectacular clerical error, find myself a member of the Society! This group has become the community that encourages me most in my own writing. I've just returned from a Chrysostom gathering in Texas, where I read a rough draft of a personal essay and received excellent counsel in how to revise it.

I never dreamed that I would someday, through a spectacular clerical error, find myself a member of the Society! This group has become the community that encourages me most in my own writing. I've just returned from a Chrysostom gathering in Texas, where I read a rough draft of a personal essay and received excellent counsel in how to revise it.

As a gesture of my gratitude to them for welcoming me into their strange rituals and secretive endeavors, and as an expression of my enthusiasm for their work, I'm going to introduce you to some of the Society members one by one.

Let's begin with the Society's most notorious hoarder of books: John Wilson, the editor of Books and Culture.

John Wilson's work on Books and Culture has led me to books that I treasure, poets I faithfully follow, and enlightening perspectives on movies as well. (I've even had the privilege of being published in its pages.)

As Wilson himself has said, the journal is not just about books. It's about everything.

Books and Culture convinced me at a very young age that Christians could write criticism that was as intellectually adventurous and insightful as any criticism. I encourage you to subscribe for one year, and you'll see what I mean.

But this isn't just about the publication — it's about the man. John Wilson is a close reader — of books, of art, and of people. He was a big believer in my novel Auralia's Colors, and supported me with encouragement throughout that four-book project. (He's also a close reader of Twitter, but watch out: His scalpel-like intellect does not suffer fools gladly.)

On night after I had lectured at the Laity Lodge Writers' Retreat, Wilson and another Chrysostom member talked with me late into the night, persuading me to consider my own future as a writer in a whole new way. That led to my decision, after years of uncertainty, to pursue a masters in creative writing. It was the right choice. And without his recommendation, I might not have started up that path at all.

John Wilson is also an editor at large for Christianity Today magazine. He received a B.A. from Westmont College in Santa Barbara, California, and an M.A. from California State University, Los Angeles. You can find some of his reviews and essays in The New York Times, The Boston Globe, First Things, National Review, and beyond. He and his wife, Wendy — also a born encourager of writers and artists — live in Wheaton, Illinois.

Here's a great interview with Wilson about his work.

http://vimeo.com/71837288

And here is his list of his favorite books of 2014.

When John Wilson speaks, my library gets larger. And my life gets richer.

What Breakup Record Cuts Your Heart Open? Readers Respond!

Last week, I invited you to listen closer to Björk’s song “Stonemilker” — the first song on Vulnicura, the Icelandic artist’s brave and beautiful musical chronicle of struggles with (and, ultimately, severance from) a great love.

Last week, I invited you to listen closer to Björk’s song “Stonemilker” — the first song on Vulnicura, the Icelandic artist’s brave and beautiful musical chronicle of struggles with (and, ultimately, severance from) a great love.

As I marinated in that music, I began thinking about how commonly I hear songs about heartbreak, but how rarely they have that raw, serrated quality of actual human experience.

And then I posted a question on Facebook and elsewhere: What breakup songs or breakup records mean the most to you? What music do you find entangled in your own hurtful experiences of separation?Read more

Listening Closer: Bjork's "Stonemilker"

On Facebook last week, I asked people to share their favorite breakup songs and breakup albums. I’d become enthralled by a powerful new album lamenting the loss of love and of a family unit, and I wanted reference points to help me evaluate it fairly and avoid exaggeration and hyperbole in describing it.

My interest in the specific titles posted on my Facebook page — “Coldplay’s Ghost Stories!” “Adele’s 21!” Simon and Garfunkel’s ‘I Am a Rock!’” — was quickly surpassed by my interest in the sheer enthusiasm with which people responded.

We have strong feelings about breakup songs, apparently.

This shouldn’t surprise me: Sharing your heart with someone who in turn takes sledgehammer to it understandably leaves an impression.

So my latest "Listening Closer" post at Christ and Pop Culture quickly grew into a two-part installment. This week, I’ll tell you about the song that sparked the questions. Next week, I’ll pass along reader recommendations and share the one that means the most to me.

Looking Elsewhere: January 24, 2015

I'll conclude with a few words about the American Sniper hubbub.

But first, here are some of the things that caught my attention on the Wild Wild Web in the last couple of weeks...

FILM

- Michael Sicinski's review of The Imitation Game is brilliant.

- Then, continuing the awesomeness, Sicinski talks about the legacy of great religious cinema... and how the new "Christian movies" look miserable by comparison.

- Alissa Wilkinson is keeping a Sundance Film Festival diary for Christianity Today. Today she reviews The Witch.

- Steven Greydanus delivers his Top 10 of 2014. Several of those titles still haven't opened in Seattle. (Sigh.)

- Michael Leary at Filmwell on Paul Harrill's wonderful film Something, Anything. It's streaming now on iTunes!

- Look at the new Cannes jury co-presidents!

LITERATURE

- Alex Malarkey: "I did not die. I did not go to heaven. I said I went to heaven because I thought it would get me attention." Well, it certainly made your publisher a lot of money, Alex. And now it has thrown fuel on the fires of cynicism about the idea of heaven for people who were already skeptics.

- Artur Rosman interviews Gregory Wolfe, and it's great.

- Thanks to Alan Jacobs for sharing "Coleridge on the Reading of Fairy Tales."

CREATION

- Isn't it amazing how those who argue that global warming is real have actually rigged the entire cosmos to back up their silly ideas?

SPORTS

- My favorite sports event of the year: The NFL Bad Lip Reading.

MUSIC

- Here's the first review of Bob Dylan's new album: Shadows of the Night. And here's an interview in AARP. And here's a song.

- Listen to the new Punch Brothers album, produced by T Bone Burnett, at Press Play. It's full of joy and harmony and invention and astonishing musicianship. "This Little Light of Mine" will never be the same ("Little Lights").

- The Guardian calls Carrie and Lowell "The Best Record Sufjan Stevens Has Ever Made." I can't wait.

- St. Vincent has an awesome new song: "Bad Believer."

- Bettye LaVette's new album, produced by Joe Henry, features covers of Bob Dylan and Over the Rhine. It's streaming here.

NOW... ABOUT AMERICAN SNIPER...

Last week, I saw people making comments on Twitter that implied Selma is a movie for liberals and American Sniper is a movie for conservatives.

That made me sad: Why spoil works of art by reducing them to partisan politics, when there is so much in both films for everyone to enjoy, admire, examine, and discuss?

Then I came across this, from Marilynne Robinson's "Imagination and Community":

When definitions of 'us' and 'them' begin to contract, there seems to be no limit to how narrow these definitions can become. As they shrink and narrow, they are increasingly inflamed, more dangerous and inhumane. They present themselves as movements toward truer and purer community, but, as I have said, they are the destruction of community. They insist that the imagination must stay within the boundaries they establish for it, that sympathy and identification are only allowable within certain limits. I am convinced that the broadest possible exercise of imagination is the thing most conducive to human health, individual and global.

[emphasis mine]

Read that quotation again.

Then consider these quotes from Chris Kyle, the "hero" of American Sniper:

On being a sniper:

“You do it until there’s no one left to kill. That’s what war is. I loved what I did… I’m not lying or exaggerating to say it was fun.”

“I wondered, how would I feel about killing someone? Now I know. It’s no big deal.”

“There’s another question people ask a lot: Did it bother you killing so many people in Iraq? I tell them ‘No.’ And I mean it.”

On the moral ambiguity:

“I have a strong sense of justice. It’s pretty much black-and-white. I don’t see too much gray.”

Now consider the reaction that many are having to the film.

Personally, I would be cautious to take as gospel anything said about moral ambiguity by someone who suffered a lot of PTSD.

And the actor who played Chris Kyle says that the film was not meant to express political support for, or criticism of, the Iraq War. It was supposed to be a movie about the damage that our veterans have suffered, and how we need to take care of them.

If it’s not this movie, I hope to god another movie will come out where it will shed light on the fact of what servicemen and women have to go through, and that we need to pay attention to our vets. It doesn’t go any farther than that. It’s not a political discussion about war, even…It’s a discussion about the reality. And the reality is that people are coming home, and we have to take care of them.

Maybe if we heeded Robinson's words — which are actually a translation of the Gospel message regarding how Jesus calls us to open our arms to people of different cultures, classes, vocations, and genders — we would help break the cycle of violence in the world. It could begin by referring to our "enemies" (and yes, even those who might provoke the term "savages") as our "neighbors," and learning how to pray for them and desire God's mercy on them (as Jesus did), instead of fooling ourselves into believing that gunning them down will advance God's kingdom in the world.

P.S. My friend Lindsay Marshall linked to this article , and noted:

It seems to me the heart of the problem is when believers (of any kind, religious and otherwise) expect art to serve as their echo chamber. They look to it to confirm their opinions rather than as a vehicle for exploring others' experiences. We rob ourselves of a rich opportunity to build empathy and deepen our understanding of Truth when we do that.

But heck, if we're just going to use film to confirm our beliefs, let's at least get it right and pick the film with a main character whose values actually line up with the teachings of Christ.

Listening Closer to Joe Henry's "Sparrow," The Lone Bellow, and Jessica Pratt

It started back when I learned to diagram sentences. Elementary school weirdo that I was, I loved it.

I loved taking a complicated sentence and chalking its various parts on the blackboard until it looked like a tree branch stripped by winter. But unlike the dissected frogs in my science class, diagrammed sentences seemed even more alive when we were finished with them.

In a way, I’m still pursuing that strange exercise, for there are profound mysteries living within great songs, just begging for investigation.

Take, for instance, the first song of Joe Henry’s album Invisible Hour (my favorite album of 2014).

It's the subject of the second installment in my new series called "Listening Closer," published on Mondays at Christ and Pop Culture.

•

And when you're done reading that column, put on your headphones because there's some high-priority listening up at NPR First Listen for a limited time...

The Lone Bellow's new album Then Came the Morning is streaming there.

And so is an intriguing new record by Jessica Pratt: On Your Own Love Again. She's new to me, but she has certainly won my attention.

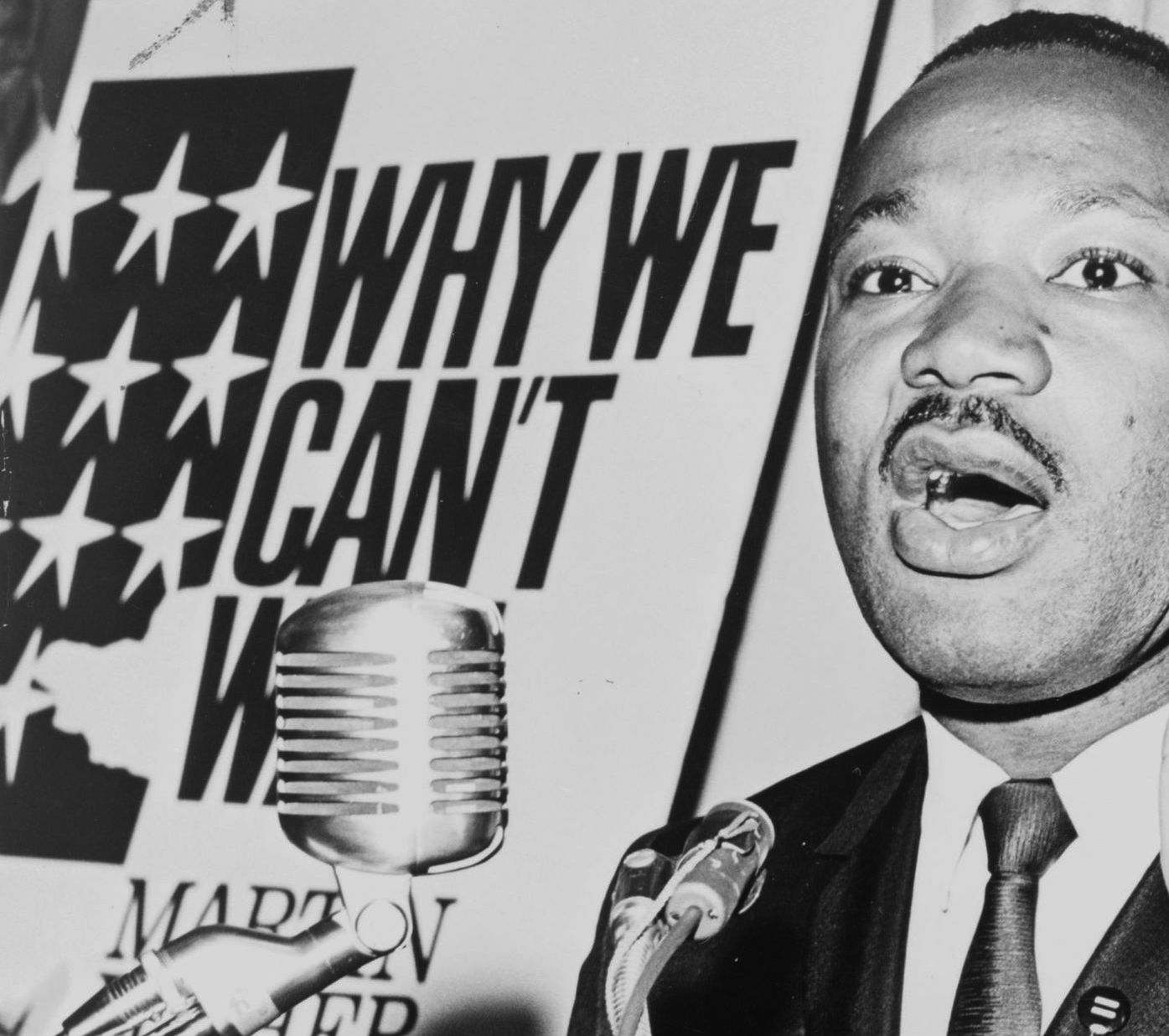

"Our nation was born in genocide..."

I could write and write and write about the Gospel truths spoken by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

But he's the great orator. Let's make a space for him to speak.

If you feel weighed down or despairing over the racism rampant in the world today, remember this...

“I believe that unarmed truth and unconditional love will have the final word in reality. This is why right, temporarily defeated, is stronger than evil triumphant.”

If you wonder what kind of difference you can make, remember this...

“Everybody can be great ... because anybody can serve. You don't have to have a college degree to serve. You don't have to make your subject and verb agree to serve. You only need a heart full of grace. A soul generated by love.”

If you read more great words from this great man today, feel free to share them in the Comments here.

Here are some more that stopped me in my tracks today.

They were shared by Lindsay Marshall, a high school teacher and mother whose students are blessed to have her:

Our nation was born in genocide when it embraced the doctrine that the original American, the Indian, was an inferior race. Even before there were large numbers of Negroes on our shores, the scar of racial hatred had already disfigured colonial society. From the sixteenth century forward, blood flowed in battles over racial supremacy. We are perhaps the only nation which tried as a matter of national policy to wipe out its indigenous population. Moreover, we elevated that tragic experience into a noble crusade. Indeed, even today we have not permitted ourselves to reject or to feel remorse for this shameful episode. Our literature, our films, our drama, our folklore all exalt it. ("Why We Can't Wait," 1963)

[UPDATES]

I would love to copy the quotations I found in this piece by Christina Cleveland, but better to send you to the page that shared them.

Why We Need "Selma"

We need this movie.

We need it for this reason: Wherever Martin Luther King Jr. carried his dream, racists and scoffers assembled.

Americans have made some admirable progress since then. But is it over? Was the dream realized?

When I praise this movie that was made in celebration of King's dream — guess what happens. The taunters and scoffers assemble.

This fellow showed up on my Facebook page, responding to my praise for the film Selma.

He continued with his condescending, hateful speech. I blocked him so he won't post such stuff on my pages again. I suppose he feels he was unfairly treated. If so, what an irony.

[UPDATE]

Today is Martin Luther King Day...

and as I shared a TIME Magazine article about marchers in Alabama who assemble in honor and respect for those who were slain and persecuted — and who still are — in the South, this guy responds to my post:

When I responded that a march in memory of those who were slain and beaten against America's own laws and standards of human rights, he responded again.

Personally, I suspect that those who have to deal with the burden of prejudice every day of their lives are more "tired of it" than that guy.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5fsv2lidFzc

May the Lord have mercy on America, and may he root out all forms of prejudice and hatred in our hearts.

Sow the seeds of compassion. Take friends, family, and especially young people* to see Selma.

*This film contains scenes that will be troubling in the best ways for adults. But I'd argue that those scenes are too intense for small children.

Do You Hear What I Hear?

This week, I begin a new year-long adventure: "Listening Closer."

Thanks to the imaginations of the folks at Christ and Pop Culture, I will write about one song every week, opening it up to consider what's inside, where it came from, what it might mean, and why it has caught my attention and stayed on my mind.

When I first started writing about art, I was just a kid, and I was just as interested in writing about music and literature as I was about movies. In time, the movie-writing drew an audience, and so I invested myself more heavily in that.

But I've missed music-reviewing.

Ideally, I'd love to host actual listening parties. Wouldn't it be fun to explore these things together in person? I'm hoping that someday I'll get to exercise the disciplines that I developed as a student at Seattle Pacific University in an actual classroom, adventuring into an exploration of the intersection of faith and art. Even as a high school student, I fell in love with the experience of investigating texts, movies, and music with students. (I'm so grateful to the schools that have invited me to share with students in this way — Northwestern College, Judson University, Biola University, Lee University, Valley Christian High School, and especially Covenant College, where Anne and I had the joy of serving as Writers-in-Residence. I'm looking forward to visiting Houston Baptist University to speak about faith and fiction-writing in 2015.)

But for now, I'm enjoying opportunities to explore art and faith through writing — and I'm thrilled for the chance to get back to a vigorous investigation of music once again.

Thanks especially to Richard Clark and Mary Elizabeth Baggett, who will — much to the benefit of all of you — monitor my behavior and, more importantly, edit me.

Here is the first installment of Listening Closer.