#Ferguson and #Mockingjay

Two guys — a blogger and his friend — after watching the blu-ray of The Hunger Games: Mockingjay — Part One on the friend's giant plasma TV:

Blogger: "So, let me get this straight. You were cheering for Katniss and her friends in their rebellion against the evil oppressors."

Friend: "Right."

Blogger: "But she's acting in an anti-authoritarian way."Read more

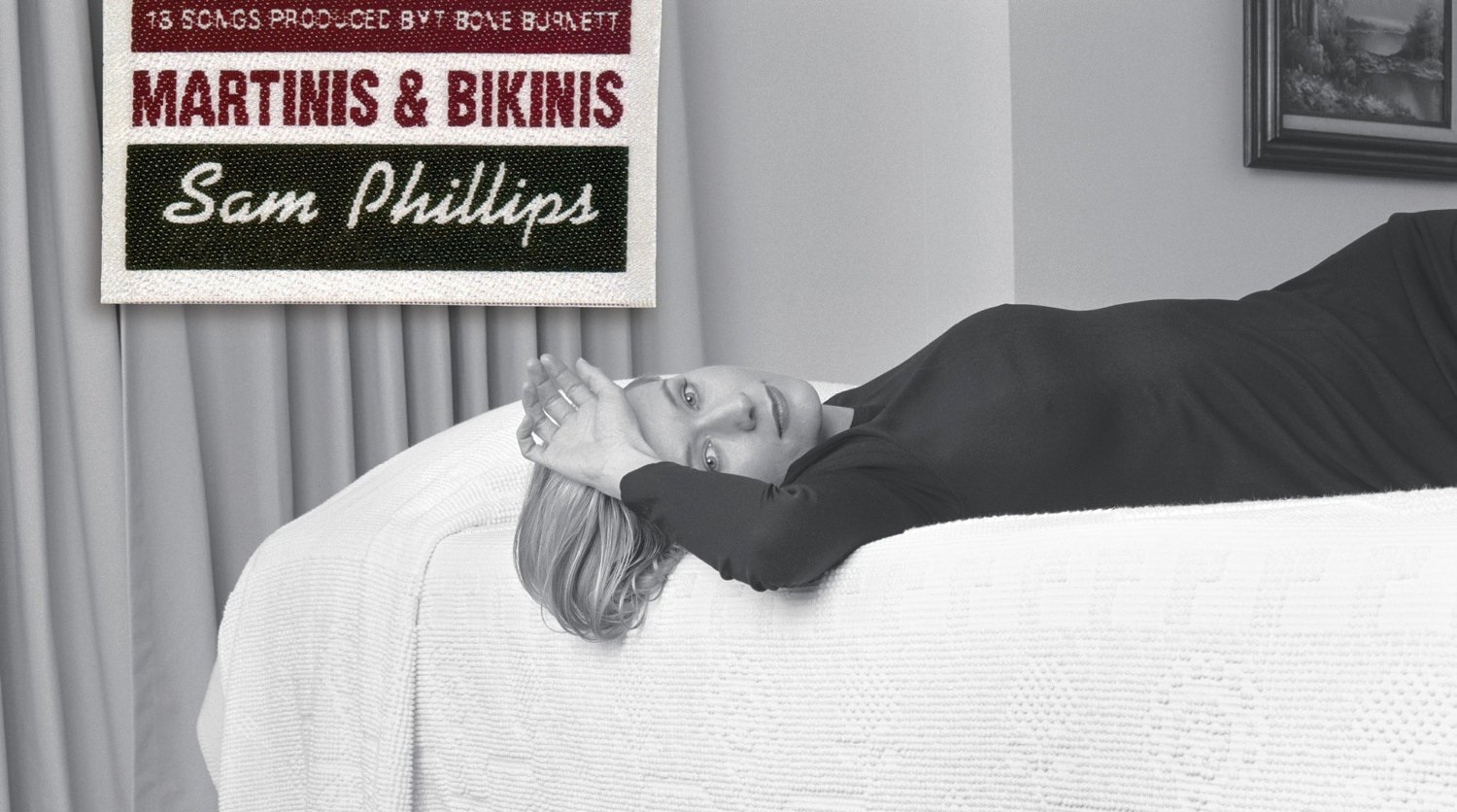

Flashback: My conversation with Sam Phillips

This weekend, Sam Phillips joined Joe Henry onstage for what was reportedly a knockout, 2 1/2-hour concert. Oh, if only I could have teleported down to L.A. to at the Coronet. I've been in a bit of a funk, knowing that I was missing one of my dream concerts.

This weekend, Sam Phillips joined Joe Henry onstage for what was reportedly a knockout, 2 1/2-hour concert. Oh, if only I could have teleported down to L.A. to at the Coronet. I've been in a bit of a funk, knowing that I was missing one of my dream concerts.

To cheer myself up, I'm revisiting one of the highlights of my life as a journalist and as a faithful, attentive Sam Phillips listener.

The following interview was published in Image Issue #60, the 20th anniversary issue, in early 2009. Later, in May 2011, Image presented her with the eighth annual Denise Levertov Award.

•

In 1987, three years after Harper’s heralded her as the “Queen of Christian Rock,” Leslie Phillips sang these words: “You lock me up / with your expectations / Loosen the pressure you’ve choked me with / I can’t breathe.”

That song appeared on an album called The Turning, and the title spoke of her decision to step beyond the boundaries prescribed for her by the Christian music industry. Two years later, Phillips reemerged wearing her childhood nickname, Sam, and presented herself to mainstream audiences as edgy pop artist whose imagination might qualify her as the late-arriving fifth Beatle.

Over the course of three albums (The Indescribable Wow, Cruel Inventions, and Martinis and Bikinis), she became a critics’ darling, and her whip-smart lyrics about love, politics, faith, and desire made it clear that her “pop star for Jesus” days were over. After a best-of collection (Zero Zero Zero) and four more albums (Omnipop, Fan Dance, A Boot and a Shoe, Don’t Do Anything), Phillips is still “turning,” still in transition, still defying expectations. She played Jeremy Irons’s mute girlfriend, a German terrorist, in Die Hard with a Vengeance, performed a spooky closing-credits number at the end of Midnight Clear, scored scenes for TV’s Gilmore Girls, and played herself in Wim Wenders’s film The End of Violence. Her career has included collaborations and appearances with Bruce Cockburn, Elvis Costello, Jimmy Dale Gilmore, Marc Ribot, Van Dyke Parks, and T-Bone Burnett. One of the most consistent aspects of Phillips’s work has been its literary quality; well read listeners will find a whole library of allusions in her songs. The on-line All Music Guide writes that Phillips “never coasts on the fumes of her influences, but turns them on their head and gives them new life.”

She was interviewed by Jeffrey Overstreet.

•

Image:

In 1994, Newsweek’s Jeff Giles remarked that you “began studying philosophy and religion” when you were fourteen years old. And in the interviews you gave to CCM Magazine near the close of your Christian music career, you were quoting Lewis and Chesterton quite comfortably. Did their influence play a part in your decision to step off of that platform? Did other writers influence that choice?

SP:

It’s hard to be specific about influences. I always believe influences are absorbed and then come out in the strangest ways, probably never the way you’d want or plan. They just sway you. A lot of those writers I was quoting early on were like rungs of a ladder. I’d been through a very confusing and difficult thing, and I had to grab onto something. My sister-in-law, who is from Cuernavaca, Mexico, went to seminary. When she graduated she was very young, twenty-four, I think. Faced with the question of whether to become an ordained minister, she decided not to. She had the wisdom to see that at twenty-four she didn’t know how to counsel married people, or people who had been through a lot of loss or had a lot of debt. She decided that her true calling was to become a teacher. She’s a wonderful teacher to this day. I think she was so wise to say no thanks. I was an idiot. I was egotistical. I thought, “Oh, I can save the world. Sure, no problem. I’m up for it. And I can not only make music, but afterwards I can talk to people who need professional counseling and help them.” I was put in a position where I was supposed to live my life as an example for other people. There was so much pressure to be—not exactly perfect, but a very weird version of perfect. So, when freedom came, when the mystics came blowing through my world, it was such a relief. I hung onto those writers, especially Thomas Merton. He’s the only one who has fully resonated.

Image:

What drew you to Merton?

Merton grew so much after his first books. At the end of his life he came to see The Seven Storey Mountain as a nice, quaint little book. He looked back and thought, “That’s not me anymore.” He almost apologized for what I believe is a great book—what everybody thought was a great book. I can relate to his evolution and to where he ended up. I like his being able to embrace Zen and not be threatened by it. I feel at this point in my life that I can worship in a Buddhist temple just as well as in another kind of church. I might as well be in New Mexico looking at the mountains. I don’t feel I have to adhere to a certain regimen or routine or dogma. There’s a beautiful thing about getting to that stage. Most of the people I meet after shows who really want to talk have been through the same kind of thing. They started out with fundamentalism and have been on a journey for something more, for a spirituality that’s bigger, that’s attempting to be as big as God is or should be. Merton is a beautiful writer. He’s humble enough to take what he can from this to help him on his way. It’s like Peter’s revelation, when the sheet comes down from heaven and there are all these things on it that were forbidden in the Old Testament. And the revelation that God gave him was this: “See all these things? Go ahead and eat them. It’s okay, it’s a new time.” I feel that about Christianity. That’s a metaphor for me. I take that as: “You know what? If Yoga helps you, if you can embrace Zen and that helps, if that lets you understand God and life and love more clearly, if that helps you on your way, then it’s okay.” God is bigger than all of this, than doctrine, than dogma. Those things are going to fall away. God’s going to outlast all of the institutions and all of the trappings.

Image:

You’ve got to admit that talking about a book like Chesterton’sOrthodoxy is not normal behavior for a Christian pop starlet. When did this intellectual curiosity begin in you?

SP:

It started at age ten or eleven. My dad is a great reader. He loved to go to the library, to bookstores. I would go with him and poke around. My mom was a Presbyterian, and I’d been to church with her, and to Sunday school, but it didn’t stick. I wasn’t interested. At age eleven, I somehow found this crazy book. It was some kind of positivism, but with a Christian twist, the notion being that if you praise God in every situation, grateful for everything that comes your way, things will change because of that attitude. The writer described her experiences where disasters would happen and she would just say, “Well, okay, God knows best, I’m going to be thankful for this. I’m going to praise God anyway.” Then these crazy, miraculous things would happen to her. I was fascinated. This Christianity, this belief system was changing this person’s life. I was hooked from that moment. Then the local Pentecostals (or some kind of ’costals) were having a regular meeting at our little civic center a few blocks away from my house, doing their thing, and I would go check that out. I was fascinated, and fascinated by parachurch organizations like Calvary Chapel in Costa Mesa, California, which was a youth movement piggy-backed on the counterculture. They had free concerts, and it was all evangelical. It was based around an invitation at the end to become a Christian.

Image:

So you made this journey on your own. Your family wasn’t bringing you into it.

SP:

This was really my own thing. When I started out at ten, I was pretty much on my own, just reading and putting pieces together. When I was in junior high, in a youth group at the local Presbyterian church, a couple of college-aged women became like older sisters to me and took me under their wing. We would go to Calvary Chapel and investigate some of these happenings. We were exploring the subculture. I found my way into the Vineyard, where I met Bob Dylan and all these crazy Hollywood people at a young age. T-Bone was also there, although I didn’t know him at the time. I went through an interesting journey as a young kid before graduating from high school, coming into contact with all these characters. At that time a lot of people were turning to Christianity, a lot of people who since have left the church. It was an odd time, and it’s hard to explain this to people who know fundamentalism now, who see the very political church, the very showy church, and the televangelists. This was more of a groundswell. I’ve always thought it would be interesting to write a book on those times. It was a beautiful time in the church. People can’t understand the difference between what was going on then and what goes on now.

Image:

You must have felt some tension, becoming successful in a very prescriptive Christian rock world, while the writers who fascinated and inspired you were coloring outside the lines.

Things were happening simultaneously in my life. I was reading more, meeting people who had faith but who were not involved with the church. And the church was getting very political on the abortion issue. And then my record company was demanding dishonesty from me, saying weird things like, “This song just sounds a little too sexy. We don’t know why, but you’ve got to change it. And no, we don’t know how you’re supposed to change it.” At that point it just got ridiculous. I said, “This is ludicrous. I’m not going to continue with this label.” At first they were upset and said, “You have to. You’re under contract.” I was selling well enough for them that they didn’t want to let me go. But I said, “There’s a moral clause in my contract. And you know what? I’ve slept with someone that I’m not married to. And I’m not ashamed to tell anybody about that. And I will.” They said, “Okay, you’re free to go. You’re out of your contract.” That’s how easy it was to get out of it. That’s how silly it was. But it was a good parting of the ways. The label, and the church I was attending at the time, were worried that here was this young girl running around talking about Christianity who might not always toe the line, who was getting out of the barn and away from their control. They found it threatening. They were trying to rein me in, having me do secretarial work at the church to help put me under their control. I have crazy stories about some of the fringe characters that I met in the parachurch organizations—from former groupies to former drug dealers, and one guy who had done hard time in prison now had a prison ministry. There were so many amazing, colorful characters who I have great affection for—a lot of really good human beings who were deeply flawed, who were trying to have some kind of spirituality, trying to help people, trying to change the world in their own way. It was a complicated decision to leave, and a very complicated time for me. And Merton seemed very clear, very simple, very calm in the wake of all that had gone on in my life during those years.

Image:

You’ve joked about writing a tell-all memoir.

SP:

I certainly could write a gossip book. But my gossip would only make it funnier and more heartbreaking. The people themselves were pretty extraordinary. I’m so glad to have had that experience at a young age. Every time somebody asks me how I got into the music business, I just roll my eyes. Obviously they don’t have time for me to explain, not really. It’s not a career path anyone should try to follow. Or could follow.

Do you still read Chesterton and Merton? Were there others who gave you comfort or inspiration along the way?

SP:

Malcolm Muggeridge was another. His writing was really beautiful to me. I haven’t read Chesterton in quite a while, but he is one of the more logical, wellspoken, clever, brilliant writers around. He helped give me clarity. Lately I’ve felt more akin to Alice Waters. Before she started on her culinary journey, when she was very young, she worked for a political campaign and was disillusioned when her candidate didn’t win. So she said something like, I’m going to go create my world. I loved that, because she absolutely did. She changed cuisine. She changed the way we eat and the way we think about food. She was talking about organic farming and sustainable living a long, long time ago. She has her famous garden up in Berkeley, a public garden that helps underprivileged kids. I find Chesterton and some of my early reading a little further away from me now. Later I went more in an Alice Waters direction: I’m going to create my own world and do the music I want, do things that are interesting to me. I didn’t leave behind the logic, the eloquence, and the thoughtfulness of writers like Chesterton, but I became more interested in imagery and things beyond words. I always have a sense that the music is a lot bigger than what I end up writing about. I’m always aspiring to get there, to do better. I’m now interested in more imaginative writers like Henry Miller, and some of the poets. Jean Giono became such a profound part of my life. When going through my divorce, I was reading Jean Giono’s The Horseman on the Roof, which is such a beautiful metaphor for somebody who feels lonely and disconnected, yet finds a beautiful point of view up on the roof, looking down on things. Even though they’re isolated, they find some great perspective in that pain and insanity of having to live up on a roof.

Image:

Some people will jump to the conclusion that, since you share Merton’s appreciation for Zen, and your faith is opening you up to see merit in other traditions, you’ll end up deciding that all religions are saying the same thing.

SP:

Thomas Merton never said that all religions are the same. There’s a big problem with saying, “I believe in all religions,” because that’s impossible. How can you reconcile all religions? They’re very different, and you obviously wouldn’t know what you were talking about. I think what Merton expressed was closer to what I feel: he embraced the mystical part of every religion and believed that those small corners were connected. And I believe that too. The Bible says we see through a glass darkly. We may not have all the facts and all the doctrines correct, but I’m not sure that at the end of the day that’s the point. If we miss a few points, I think it’ll be all right.

Image:

You read a lot of Lewis along the way as well?

Absolutely. He’s beautiful. If you’re a fundamentalist, you’ll find he’s a little outside the box. He’s so articulate. The metaphors in his fairy tales.... I didn’t love the Narnia movies, but I felt strong emotions when I read the books. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings is certainly my favorite of those kinds of stories, and the movies couldn’t have been better. There’s something in almost every scene that you can turn toward your own life, that can go metaphorical: the steward is ready to kill his son, and he kills himself because he just doesn’t get that there’s hope. It’s about how egotism and negativity can ruin your life and the lives of those around you. Lewis will always have a place in my heart because of the tenderness and humility of those Narnia stories. They make it so real to children, and it takes great humility to get down to that level, especially for someone as wordy and intellectual as those Oxford guys were. I will always love Lewis for doing that.

Image:

In your journey as a writer you’ve moved from the didactic, prescriptive tendencies of Christian pop and into a more literary realm. In the song “Five Colors” you say: “I’ve tried, I can’t find refuge in the angle / I walk the mystery of the curve.” It seems that your attraction to the fantastic and to poetry has influenced not only your interests but also your method of exploration. Your lyrics have become more challenging, requiring more from the listener.

SP:

I certainly don’t mean to make demands on the listener. To me, if I’m trying to tell people what to believe or what’s right, that wears people out much more than opening the song up and allowing them to be struck by some image. A woman said to me recently that she loved Fan Dancebecause it played like a movie in her head, there were so many images. I love that. That is exactly what I wanted. I’d rather take somebody into a world, so that when the music’s over, they don’t know exactly where they have been, but they know they were transported. Even though that’s a small thing, a brief thing, something you can’t explain, in the end it helps us change and grow, helps us love, and inspires us to move forward.

Image:

What writers have your attention now?

SP:

I completely fell in love with Gaston Bachelard, who wrote The Poetics of Space and The Poetics of Reverie. I absolutely adore him. If you haven’t read him, I would start with The Poetics of Space. I think you’ll find no end of inspiration from that book. He was very ambitious in his analysis of poetry, and he’s a poet and a dreamer himself. He talks about, for instance, how you return to your childhood home in your dreams, and what it means that you still think of it and how it affected you. You’ll say, “I went back to my childhood home, and it was so small,” or “It’s not the way I remembered it.” My grandmother’s home seemed like Narnia to me, infinitely big, and we’d go in and play all kinds of games. But when we go back, it’s like, “This is so tiny. How’d we ever fit in here? How could we imagine things in here?”

Image:

There are so many different forces and influences moving through your songs—references to your reading, relationships, and experiences with religion and the recording industry. What about your family? Did your parents have anything to do with your intellectual curiosity and your aversion to, as you call them, “the metal teeth of ugly rules”?

SP:

My mother and father chose lives and professions that were sort of classic and small. At the time, it seemed American and logical that the best way to proceed in life was to have kids, stay in one place, and get a good job. But I always felt that it never fit either one of them. They both had wild parts. I’m not sure that ever really manifested itself in my mother. She kept things in and was able to stick with the structure. My dad did have some moments where he acted outside the box. But I always felt that they never really got to be who they were. They always seemed to have a double life: the life they were leading and the life they wanted. Maybe they just didn’t have the courage. Or, in the end, maybe they didn’t think it was worth it, or responsible, or logical, because of what was American or what was accepted. I’m not sure how this affected my life. They gave me a lot of love and encouragement, and despite their shortcomings and prejudices, they wanted me to do well and be happy. People talk about the middle child always being neglected, but I felt that I stood out and maybe got too much attention. I think my brother and my sister feel this way. I’m not sure I understand how my parents shaped me, but that may change in five, or ten, or twenty years.

Image:

Do your parents appreciate your music?

SP:

My mother is very much a fundamentalist. She loves me, and she prays for me all the time and hopes for the best. I think she thinks, “Well, I don’t understand it, but I love her and I’m with her all the way.” My dad appreciates it, but it’s not his cup of tea. I don’t think he’s interested in the kinds of things I’m talking about. My mother has a little more of a leaning to understand it, but she would shy away from any Christian who embraces Zen. She doesn’t want to mix it up. She wants it more black and white.

Image:

Rainier Maria Rilke shows up in your songs from time to time. For example in the song “Your Hands,” from your 1996 album Omnipop.

SP:

I’ve been reading him a long time, starting with, of course, Letters to a Young Poet. T-Bone introduced me to that book early on, and then it seemed to have a resurgence, particularly in AA circles. That book made its way into the culture in a big way. When Wim Wenders asked me to be in his film The End of Violence, I said, “Wim, I would love to be in your movie if you would just translate a little bit of Rilke for me.” I think he was a bit taken aback. He stiffened a little, but he did laugh and say maybe he would think about it, though he still hasn’t done it. I was a little embarrassed that Robert Bly’s translations of Rilke’s poems touched me so deeply. I started wondering if it was Bly I loved, or Rilke. I started wondering about how close those translations were, and how much liberty Bly had taken—even to the point of considering taking German. But I had sung a Bach cantata, and I just felt it wasn’t a language I wanted to speak. It’s not as pretty as French. Rilke’s ideas seem to be big enough that they just leap over the forms and the languages, which is quite a feat for a poet. I love him, or what I gather of him in my crude, English-only mind.

Image:

I understand you’ve been reading Eduardo Galeano. What appeals to you about him?

SP:

A friend of mine who is from Mexico suggested Galeano’s political books. Then I found The Book of Embraces, which is an interesting combination of magical realism, essays, stories, and political writing. I just fell in love with that book. It was tough and funny and sad and beautiful. I love the form of it, too— it’s in very short sections. I probably fell in love with it because I was touring a lot. It’s hard to read on airplanes and buses, so the short form became very important for me.

The liner notes of A Boot and a Shoe include a photo of you holding a copy of Henry Miller’s The Heart of the Matter. Miller wrote that “Art is only a means to life, to the life more abundant. It is not in itself the life more abundant. It merely points the way, something which is overlooked not only by the public, but very often by the artist himself. In becoming an end it defeats itself.” That’s a powerful statement.

SP:

I agree. I think that’s why I love Miller so much. He goes on to say that if we were really whole, we wouldn’t have to make art. I think he’s right. I don’t think art is an end in itself; it’s pointing toward something. It’s a process of us trying to love ourselves and embrace our world, to get somewhere to be whole, I guess. Not perfect, but whole. I love Henry Miller, but I started reading Anaïs Nin first. I remember seeing a couple of the volumes of her diary among my dad’s books when I was young. They were up on the high shelf, so there seemed to be something naughty about them. Also, my dad was reading something by a woman! That got me curious. Instinctively, as a young adult I picked her up out of a wish to be naughty and separate from my parents. I was really taken by her. There was something beautiful about her. When you get further in, the later volumes of the diary get taxing and difficult to read, because not only is she leading this terrible double life with these men, but she’s also losing the youth that meant so much to her at one time. She sent me to reading Henry Miller. I just fell completely in love with him. It wasn’t Tropic of Cancer, or Capricorn, although those were the first books I read. His essays are what got me.

Image:

Your song “Hole in Time” is dedicated to Walker Percy.

SP:

T-Bone had a connection to Walker. He knew him and could have introduced us. I’m sad we didn’t get that chance. Lost in the Cosmos: The Last Self-Help Book is brilliant, and still relevant. He was an amazing southern writer. When you get into the geeky part of the literature, you find there were letters and mutual admiration exchanged among Thomas Merton, Flannery O’Connor, and Walker Percy. They all corresponded at some point, and had written about each other. O’Connor is one of my favorites, too. Her work is so simple and beautiful and heartbreaking. She’s just got the dickens in her. You can imagine her finishing some of these stories with a little sly smile. But I haven’t been able to fit her into my work. She’s just beyond me. Who she is is such a part of her writing. I feel that about certain musicians, that who they are comes out in their work. Who Louis Armstrong was came out in that phrasing and that voice. There’s a heart and a soul there. I would aspire to have as great a voice as a writer as Louis Armstrong has as a player. But I have a long, long way to go. I don’t even know if I’ll ever get there.

Elvis Costello, Tom Waits, and Peter Buck have all listed Martinis and Bikinis among their favorite records. Alison Krauss and Robert Plant covered your “Sister Rosetta Goes before Us,” and it’s the most widely celebrated track on their album of duets, Raising Sand.

SP:

If I’m about anything at this point in my life, it’s writing songs. I’m not even about singing those songs. I’ll tell you, when I saw Alison sing “Sister Rosetta” live, it was like seeing that song go out and have a life. Like a child off to college, it was flying the nest. It was beyond me. That was such a great reward. I felt that same sort of thing happen once looking at a Jackson Pollock painting at the Museum of Modern Art. It stirred me, and I felt that the painting was alive. I thought, “How did this guy do that? He’s dead, and yet this painting is just grabbing me. It’s clearly alive.” That’s what I feel strongest about: I want songs to go beyond me, so they won’t be stuck with my voice and my versions of them. I want them to go and have their own lives, so they’ll mean something to somebody twenty, thirty, forty, fifty years from now. I felt that way about “Sister Rosetta Goes before Us” when I heard Alison sing it. It was a funny moment; not a proud moment, just a relief, a peaceful moment, a feeling of: oh, finally. I’ve been singing these songs for so darn long, and one finally got out of jail. It got out of the building. It got to fly.

For more information on 2011 Denise Levertov Award: An Evening with Sam Phillips, click here.

What Do Rhiannon Giddens, Sam Phillips, and the Movie "Amélie" Have in Common?

When a music critic declares an album “perfect,” it tends to say more about that listener’s enthusiasm—and, perhaps, hubris—than it does about the record. So I’m holding myself back from that kind of overreach here.

Suffice it to say that I’d have a hard time imagining a stronger “debut” record for Rhiannon Giddens than Tomorrow Is My Turn, an album that seems to immediately negate its own title by declaring “Today! Today belongs to Giddens.”

Here is Giddens’s chance to step into a solo spotlight under her own name for the first time, and what does she do? She shows respect to a legacy of performers who have come before her.

Here is Giddens’s chance to step into a solo spotlight under her own name for the first time, and what does she do? She shows respect to a legacy of performers who have come before her.

One of those names in particular just might become your new favorite rock n' roll guitarist. (Hint: Are you a fan of the movie Amélie?)

Check out my latest edition of "Listening Closer." Listen to a track from Tomorrow is My Turn, and learn about the inspirations for this incredible record.

The Strange Little Cat (2014)

[This review was included in my Favorite Films of 2014 post. But, for the archives, it gets a post of its own.]

•

In one scene, two young people play Connect Four.

Do you remember Connect Four? I loved playing this game when I was a kid. There was the tic-tac-toe fun of trying to see connections before somebody else did, but it was more complicated than tic-tac-toe, and it also had tactile elements that made it more satisfying: the sound of the chips clattering together, the sound of them dropping into the grid slots, and the oh-so-satisfying sound of unhinging the rack at the end of the game so the chips fell out and cascaded across the tabletop like reward tokens from a Las Vegas slot machine.

It seems an incidental moment in The Strange Little Cat, Ramon Zurcher's one-of-a-kind, somewhat experimental investigation of the controlled chaos in a French family's overcrowded flat.

But there are no incidental moments. All things here are important, a little strange, interconnected in ways obvious and subtle, potentially revelatory.Read more

Oscars 2015: Listen to My Discussion and Debate with Dr. Jeff Keuss, Novelist Jennie Spohr, and Producer Anna Miller

Finally... an Oscar year that brings some much needed focus to a subject sorely overlooked at the movies — great men with big dreams!

But seriously: Really, Oscars? Were all of the best films of 2014 about ambitious but misunderstood men with big visions for art, for change, for science, for innovation?Read more

Something, Anything (2015)

Ida, Ewa, Gloria, and now... the final contestant in this, the Looking Closer Beauty Pageant.

Readers, let me catch you up: In early 2014, I began a four-part series in which I focused on films that captured the rare cinematic marvel of a living, breathing, three-dimensional female character — somebody who does not capture our attention by being fashion-model "perfect," but rather by evincing a far more human kind of beauty.

Readers, let me catch you up: In early 2014, I began a four-part series in which I focused on films that captured the rare cinematic marvel of a living, breathing, three-dimensional female character — somebody who does not capture our attention by being fashion-model "perfect," but rather by evincing a far more human kind of beauty.

The fourth part of the series has been long delayed because it took the movie a while to become available to the public. I initially included it in on my list of Favorite Films of 2014, but since it didn't play nationwide (online) until January 2015, I've withdrawn it from last year's list. It will figure highly on my list for 2015.

Thanks to iTunes, Vudu, and Amazon Instant Video, you can watch it at home right now. And I'm not exaggerating to say that you would probably have a more meaningful time watching this movie on Sunday night than you would watching the Oscars' Popularity Contest (in which all of the Best Picture nominees are about men reaching for some kind of fame, power, and importance. By contrast, this is a film about a woman trying to escape a world of superficiality in order to find a life of truth and meaning. Ladies and gentlemen... meet Margaret.

•

If we're not careful, life becomes a costume party.

We put on our various personas—for work, for school, for church, for friends, for families, for spouses, for dates—and what we put on opens up parts of our personalities and shuts down others.

In Something, Anything, the first thing we see is nail polish. It's part of Margaret's ritual, how she prepares to take her place at the table during a social gathering with friends and her significant other. It's clear right away, in a scene when we see her making a commitment to take on a new role—the role of wife and, her friends automatically assume, mother—that Margaret is willing, but not exactly enthusiastic. She seems surprised, withdrawn, laughing nervously as she says what everyone around her is expecting her to say. But notice: When her boyfriend proposes, she says two things: "Yes." And "I don't know what to say." Hers is a life of capitulation, of accepting the shape of a life (note the symbolic gesture of a consumer-culture marriage: the aiming of the Box Store Bridal Registry Gun) without ever really coming to life. We move from Margaret painting her nails to Margaret picking up paint chips to imagine the color of her nursery.

And so she sets out on a journey that is very familiar to American moviegoers: the difficult and often oppressive life of the suburban housewife. In films as different as American Beauty, Edward Scissorhands, Little Children, and The 'Burbs we have seen men and women trying to fit neatly into their neighborhoods, content to follow the program like a piece in a factory-made house, only to realize that an authentic life requires more than going through the motions. Such stories usually condemn those communities with broad brush-strokes of condemnation and contempt. And they urge their protagonists to break free from the prison of commitment, the humiliation of sacrifice, and launch out into a self-centered "seize the day" adventure.

But not this film. Instead of "Go out there and revel in your time!", Something Anything has the wisdom to point us toward the ministry of a still, small voice. I'm not "reading too much into it" — the film actually opens with these lines:

Who has seen the wind?

Neither I nor you:

But when the leaves hang trembling

The wind is passing through.

- Christina Rosetti

A spirit, moving in mysterious ways, has already set Margaret at odds with her real-estate coworkers, who play games with their clients' lives behind the scenes to make as much money for themselves as possible. After a life-and-death crisis exposes for Margaret all that is empty and false about the life she has half-heartedly chosen, she finds she is better able to empathize with those home-seekers and home-sellers who find themselves in desperate circumstances. And she knows that the way, the truth, and the life are calling her off the path of capitalism's false promises. I want to proceed carefully here, so as not to spoil the plot for you, but at one point she mentions that she feels "pregnant." And I think it's a loaded statement: She may mean it one way, but I think we're meant to sense that there is something within her that wants to be born. A new idea. A new life.

A spirit, moving in mysterious ways, has already set Margaret at odds with her real-estate coworkers, who play games with their clients' lives behind the scenes to make as much money for themselves as possible. After a life-and-death crisis exposes for Margaret all that is empty and false about the life she has half-heartedly chosen, she finds she is better able to empathize with those home-seekers and home-sellers who find themselves in desperate circumstances. And she knows that the way, the truth, and the life are calling her off the path of capitalism's false promises. I want to proceed carefully here, so as not to spoil the plot for you, but at one point she mentions that she feels "pregnant." And I think it's a loaded statement: She may mean it one way, but I think we're meant to sense that there is something within her that wants to be born. A new idea. A new life.

So, no... Margaret is not bound for an Eat Pray Love tour of self-indulgence and shallow pleasures. Even though her father offers her just that — a getaway to Europe — she will retreat instead into quiet, into soul-searching, into places where all of the noise and distraction and temptations fall away. Margaret's friends, as if taking the wrong notes from the Book of Job, only offer her the counsel of consumerism: Let's go shopping! She'd rather retreat to a job in a library... to read. She'll open a Bible. She'll go to a monastery in search of an old friend who, she suspects, might actually see her for who she is instead of who the world expects her to be. She'll look for hope and healing in beauty and intimacy. And in doing so, she'll get off the path of mass-produced, factory-approved American fakery and onto the path of faith.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uBWn5rG71fQ

Filmmaker Paul Harrill has made something quiet, observant, provocative, and quite contrary to the popular narrative of American love stories. He taps into deeper truths by zooming in on the suggestiveness of little things — like the way Margaret returns to the home that she has left, and the front door creaks as if she's entering a haunted house; like the enchanting (and completely real) night world of fireflies he brings to the screen. The fireflies may seem to some like just a cool visual to enhance a quiet movie, but they're much more. Margaret, like the fireflies, is finding that she must retreat into a sort of darkness, far away, where people would have to work hard to find her... and there, in that faraway darkness, she might just come to life, come to light, and rise.

It isn't an exaggeration when I say that the subtlety and sensitivity of Ashley Shelton's lead performance reminded me, at times, of Juliette Binoche in Three Colors: Blue — which, by the way, is my favorite performance by an actress.

And speaking of monasteries, the monastery that Margaret visits is the first-ever movie shoot on the property of Abbey of Our Lady of Gethsemani, the Trappist monastery in rural Kentucky famous for being the home of the beloved monk, mystic, and writer Thomas Merton. I should mention here that I have read more of Thomas Merton's writings than any other writer, and I've been more powerfully blessed by his words than any other teacher. I sensed his spirit in every scene of this film.

And that may be the highest compliment that I can give this film: It's profoundly contemplative in a way that reminds me of great films about faith, like the work of Robert Bresson, Krzysztof Kieslowski, and Terrence Malick. I think Thomas Merton would have liked it. I'd recommend it as a prime example of how contemporary filmmakers can engage questions of faith. In a time when we hear so much hype in Christian circles about "the new wave of Christian movies" — only to find those movies to be preachy, mean-spirited, crass, and mediocre (at best) — I find very different adjectives coming to mind when I watch Something, Anything: It's truthful. It's affecting. It's poetic. It's profound. And it's often very beautiful. I'm grateful.

•

For a second and third opinion, I highly recommend Glenn Kenny's review here and Leah Anderst's comments here.

Seek Justice. Love Mercy. Walk Humbly.

"And what does the Lord require of you? To act justly and to love mercy and to walk humbly with your God."- Micah 6:8

1. Seek justice.

2. Love mercy.

3. Walk humbly with your God.

Sounds like one of those "Pick two" jokes.Read more

The Lone Bellow, U2, Bob Dylan, and Aaron Strumpel – or, How I Learned to Stop Scowling and Love Liturgy

Catholics. Among the fundamentalist evangelicals who surrounded me as I was growing up, the word bordered the obscene.

I trusted that there were good reasons for this. I was always quick to believe unflattering things that adults told me about other cultures, communities, and church denominations. I felt more secure if could dismiss as a waste of time—or as the way of fools and villains—what I did not understand. And from a distance, Catholic tradition looked suspiciously foreign, weird, and mysterious. If there was anything we did not tolerate in the evangelical worship services of my upbringing, it was mystery. The Gospel was meant to be explained, after all.

I may have sensed, on some level, the dissonance between such prejudice and Jesus’ own teachings. But if I did, I suppressed it. That sense of superiority, of being on the right team, of having Jesus’ favor: they felt too good to give up.

One of the easiest targets on my denominational dartboard was liturgy.

Catholics, Episcopalians, anyone who went to mass instead of church or participated in services heavy with recitation was treated with suspicion. “The mass is just a whole bunch of people going through the motions,” I’d say. “Kneel down, stand up, sit down, chant and sing the same old prayers, Sunday after Sunday. It’s so mechanical and repetitious,” I’d say. “In our church, we pray aloud one at a time about our own concerns. We don’t just, you know,read prayers.”

But what did I do, right after church, when I got in the family car, or ran off with friends, or walked home with my headphones plugged into my Sony Walkman?

The answer will lead us to music by The Lone Bellow, U2, Aaron Strumpel, Bob Dylan, and more. Read the whole confession, along with song recommendations from many Looking Closer readers, in my latest "Listening Closer" column at Christ and Pop Culture.

Two Visits to London, Two Well-Rounded Characters

This weekend, I had an incredible amount of writing to accomplish. So I only allowed myself two breaks, and I stuffed them with two movies.

I chose wisely.

The two I chose have a few things in common. Both films take us to London. Both bring beloved characters to life (one fictional, one historical). And both of those characters are... shall we say... well-rounded?

Otherwise, they're completely different. One is a complete surprise. It's an adaptation of classic children's literature, but the trailer was so appallingly bad, promising a movie overstuffed with the worst tendencies of hyperactive kiddie entertainment, that I was tempted to start a petition to have the film buried before it ever reached theaters. But opening-weekend reviews caught me by surprise. I can't think of a case in which the film itself turned out to be so much better than its trailer.

Otherwise, they're completely different. One is a complete surprise. It's an adaptation of classic children's literature, but the trailer was so appallingly bad, promising a movie overstuffed with the worst tendencies of hyperactive kiddie entertainment, that I was tempted to start a petition to have the film buried before it ever reached theaters. But opening-weekend reviews caught me by surprise. I can't think of a case in which the film itself turned out to be so much better than its trailer.

The other film? My expectations were high. The director — Mike Leigh — is one of my favorites. And I'd been hearing raves for many months since it made the festival circuit.

As I'm still scrambling to get my assigned writing done, I only gave myself time to jot down first impressions of both films at my Letterboxd film journal. Here they are: Initial thoughts on Paddington and Mr. Turner. Catch both movies if you can.

God, Family, Country... Right? American Sniper's Troubling Anti-War Truth

So, I avoided seeing American Sniper for a few weeks because the highly politicized debate about it was so intense. I'd been given a very strong impression from certain ugly responses to the movie that it was a celebration of heroism in the Iraq War; that it glorified the killing of Iraqis; that it depicted the Iraq war as another case of Americans saving the world; and that it failed to question why in the world we went there in the first place.

Well, I was greatly relieved to find out that the film isn't like that at all. American Sniper is — like Unforgiven, like Million Dollar Baby — a film about the damage that the exercise of violence does to muscles of our minds and hearts, however honorable our intentions in exercising it.

In that sense, it's a Clint Eastwood movie through and through. And a pretty good one.

What troubled me most was not the movie itself, but that so many people could watch this movie and feel exhilaration at the violence, and that they could respond in a way that demonstrates they missed so much of what the movie was showing them.

It's the equivalent of watching a movie about the devastating effects of concussions on the brains and bodies of football players and running out to say "I've decided that I want a career in the NFL!"

To react that way — to celebrate the Chris Kyle of American Sniper as a role model and hero — is to minimize care and compassion for Kyle's wife and his children. It is to join him in blaming the death of a fellow soldier on the mere fact of carrying difficult questions about what defines a "just war" — questions that are the sign of a healthy conscience. It is to hold up PTSD as a condition to be desired and even celebrated.

My whole Sunday-night moviegoing experience was surreal. This movie exists to encourage viewers to consider what we require of our soldiers in misguided and ethically compromising war efforts, to cause us to question what a lifelong exercise of heavy artillery is likely to do to our perception of the world. And yet it was preceded by six film trailers designed to thrill us with the glamorous spectacle of heroes wielding guns, firing guns, and aiming guns at the camera.

On my way out of the theater, I passed five brightly lit posters for coming attractions that displayed their main characters holding up guns.

I feel like I've been taking crazy pills.

We have met the enemy, and he is us.

Making all of this so much worse... an audibly uncomfortable 4-year-old boy was in the seat behind me through the movie. And as soon as the movie wrapped up coverage of Kyle's war tours — as soon as he came home to learn to live with his family again — that father led his little boy out of the theater.

God, have mercy on us.

As I'm pressed for time this week, I am gratefully handing over the rest of this commentary on American Sniper to Brian McLain, who has given me permission to share his Letterboxd post on the film.

•

Thinking back over Clint Eastwood's filmmaking career — particularly the later years — there has been a reoccurring theme of fathers abandoning their children. A Perfect World, Unforgiven, Million Dollar Baby, and even Gran Torino all feature this theme prominently. American Sniper may be his strongest indictment yet.

As of this date (January 31, 2014) American Sniper has been destroying the box office. People are flocking to the theater to see it three and four times. While it's not surprising that a film about war would have it's supporters and detractors, American Sniper has practically become a touchstone for defining progressive and conservative. Those on the Right are touting this film as a patriotic masterpiece; the ultimate hero biopic. Those on the Left are rebuking Eastwood and those on the Right for blatant jingoism and glorifying killing. For the life of me, I can't understand how either side got there after watching this film.

American Sniper is an anti-war film. Eastwood has said so himself: "The biggest anti-war statement any film" can make is to show "the fact of what [war] does to the family..." Eastwood does this by pitting Kyle's real family — his wife and children — against his false family — the military. Some may bristle at my use of "false family," but I would argue that this is what Eastwood is attempting to say in his film (as well as in his previous war films). Aside from an early childhood scene around the dinner table, every meal that Kyle shares is with his military family. When Kyle returns to Iraq for his second tour of duty, he's immediately greeted with a "Welcome Home!" These men are his brothers and, in fact, they are the one's that get his time — emotional and physical. Later in the film, Kyle's wife tells him that he is a stranger to their home. He truly is. Many watch this and consider this a necessary sacrifice. Eastwood disagrees.

When watching a film, especially a biopic or historical event piece, it's important to pay attention to the events that the director chooses to portray. Often, the biopic is simply a checklist of the important events that happened in the subject's life, from birth to death. Eastwood, however, spends the bulk of the film following Kyle in Iraq, countered briefly with his time back home between tours. We're given a few moments in Kyle's early life that serve two functions: they show the events that led toward Kyle becoming a sniper in Iraq, and they serve as signposts for the viewer to see Eastwood's thesis, so to speak.

For instance, early in Kyle's life, his father tells him he has the gift of aggression and praises Kyle for beating up his little brother's bully. Right away the metaphors are flying and as if to emphasize this, Eastwood gives a rather overly dramatic view of schoolyard violence (foreboding the extreme violence we see during the war scenes), as Kyle essentially caves in the other boys face — Eastwood wants us to know that he will not be glorifying the aggressor in this film. The next scene is Kyle as an aimless adult. He and his brother live for drinking, sex, and the rodeo. Prompted by an event on the news that shows a deadly embassy attack, Kyle joins the SEAL program. Now, the events in Kyle’s real life that led up to his military career did not unfold in this manner, but I think that Eastwood is using Kyle's life as a template for many of the young men that join the military — aimless, unsure about the future, not interested in college, etc… (of course this is a broad generalization and does not apply to everyone). Immediately we see the military taking the aimless Kyle and molding him into a warrior. Well, "molding" is probably not the right term to use for this. We only spend a couple of minutes here, but it's important to understand what Eastwood shows us. While I'm sure that SEAL training encompasses a variety of physical and mental training exercises, we're basically shown one — the SEAL version of waterboarding. As the instructors hurl insults and abuse at the trainees, they blast their faces with powerful water hoses. This imagery will also come back later as we watch Kyle and his men invade a home and inflict abuse on an innocent family.

We then get the meet-cute, courtship and marriage of Kyle and his wife Taya. Again, it's important to see what Eastwood fills these scenes with. Throughout these few minutes, we get a number of important questions by Taya: "Does it make a difference?" "Why do you do it?" How will you feel when there's a real person on the end of that gun?" Every reply by Kyle is clichéd: "I love my country." "I trust my training." At one point Taya asks "Do you really think you're protecting us?" Kyle: "Yes, if we don't stop them over there, they'll come over here." Taya: "Really?" This will not be the last time this question is asked. Interestingly, Eastwood frames their marriage with gun imagery. Their courtship begins with Kyle's marksmanship winning her a giant stuffed bear at a carnival. The last scene we see shows Kyle playfully pointing a gun at his wife. The false family — whether truly or symbolically — is always encroaching on the real family. Even their wedding scene (the bride's happy moment) is filled with cheers — not for their marriage, but for the news that they've been deployed to Iraq.

Much like Kyle's pre-war life, it's important to pay attention to the war-time moments that Eastwood shows us on screen. Kyle's first kill is a child. Again, this is not accurate to Kyle's real life - he never actually killed a child — but similarly to the lingering shot of a drone later in the film, it serves as a reminder of the type of war being fought. Additionally, it's also important to recognize the moments that Eastwood does not include. There is no conclusion to the war. Despite the timeline of the film going up to 2014, we don't get the announcement of the troops coming home, the capture and death of Saddam Hussein, or the death of Osama Bin Laden. The closest we get is the death of a rival sniper, which is conveniently summed up with the phrase "mission accomplished." Ring any bells?

Other moments that are important to mention: The frequent use of the word "savages." Early on this is used to specifically refer to the Taliban. Later, it becomes a catch-all for Iraqis in general. It's also important to recognize how Eastwood frames the brutality in the film. As I've already mentioned, the deaths are not your typical Hollywood deaths — they're meant to convey realism, that even the death of an evil terrorist is weighty. Related to this, when we do see moments of extreme evil from members of the Taliban, the events that lead to this evil are a direct result of American involvement, or American miscalculations. Perhaps the toughest scene in the film — at least for me — involving the execution of an innocent man and his young son, is a direct result of Kyle going against orders. Later, when one of Kyle's closest comrades — Marc, a fellow SEAL team member — begins questioning their role in Iraq, he asks Kyle if he thinks it's worth it (them being in Iraq). Much like his response to Taya, Kyle answers with something like "of course, you don't want these savages coming into San Diego, do you?" Marc simply stares at Kyle for a few seconds, as if in disbelief, before saying "OK, let's go kill them.”

Many critics have accused the film of lying, pointing out that Eastwood leaves out many important details from Kyle's life, or embellishing other parts, in order to make Kyle appear more heroic. They criticize the ending, accusing Eastwood of ignoring some of Kyle’s documented lies and outrageous proclamations. There may be a number of reasons for this, but my guess is that the reason Eastwood does this is because American Sniper is not primarily a biopic of Chris Kyle. It's a film about war in which Kyle serves as the ideal model of the American warrior. In Kyle we have the all-American everyman who offers himself for his country and allows the military to shape him into a noble warrior. Eastwood, though, pulls back the rug and shows us the dirt that lies beneath. It's pretty filthy and when we ask "who did this?“ Eastwood points the finger right at us. While Eastwood is critical of our military, their foreign policy and their priorities concerning family, he never casts the soldiers in an evil light. He goes to great lengths to show how they are manipulated and programmed to make the choices they make. According to the writer of the film, Jason Hall, the ending wraps up Kyle’s life in a positive light because of his sympathy for the soldier and his family. After Kyle’s death, Taya told Hall that he needed to tell the truth, but to also remember that their children didn’t know their father and that this film would play a big part in how they perceive him. Eastwood, I believe, is comfortable with such a neat ending because he’s not interested in criticizing the actions of Kyle. Instead, he directs the criticism toward our culture — a culture in which we praise men who abandon their families for another one. A culture that gushes over youtube videos of little girls breaking down when they see their daddies after a years absence, when little girls should never be placed in that position to begin with. A culture that continues to believe that sending our husbands, wives, mothers and fathers overseas is necessary for our safety. A culture that revels in the destruction of life — whether it be just or unjust. A lot of ink is spilled — especially by the conservatives — rightly critiquing the loss of fatherhood in our inner cities. Yet these same critics are quick to applaud the loss of fatherhood in this other arena. That’s hypocrisy. I believe Eastwood wants us — the viewer — to ask ourselves some tough questions.

Perhaps the movie is best summed up in a scene that appears about 3/4 toward the end of the film, during Kyle’s third tour of duty. Marc asks Kyle whether his New Testament bible is bullet proof. Kyle replies "You mean the one I keep in my chest pocket?" and Marc says "Yeah. I never see you open it, so I just assumed..." After a moments pause, Kyle sheepishly replies, as if asking his own question, ”Yeah, well, 1) God 2) Country 3) Family… Right?"

Wrong.