Mystery and Message

No one has taught me more about considering and making art than "Mr. D."

That's Michael Demkowicz, who was my high school English teacher, and who remains a dear friend to this day.

Demkowicz is a photographer, and several of his prints hang on the walls of my home. But he has also influenced what I read, how I watch movies, and how I listen to music. And he was extraordinarily generous and observant in reading and responding to early drafts of my "memoir of dangerous moviegoing," Through a Screen Darkly.

I'm making it an annual event to feature my favorite single article on art, an essay called "Mystery and Message" that Demkowicz contributed to my first arts publication, a short-lived periodical called The Crossing, which contained articles written to encourage and inform Christians who were striving to create art outside the arena of blatantly evangelical, agenda-driven "Christian art."

It's short. It's wonderful. Take a few minutes and read it...

•

Mystery and Message

or What We Talk About When We Talk About Art

by Michael Demkowicz

•

Art is what happens when a person encounters mystery and feels compelled to make something of it.

That something may come out in music, movement, words, clay, pigments, or — in my case — silver bromide. And that something is not exactly an expression of the mystery, though much may be expressed. It is not exactly an explanation, though many things may be explained. That something that is art may tell a great deal, but it is not precisely an accounting. It points, and it may even surround, but it never quite communicates. To some, the ambiguity and incompleteness—the "not exactly", the "not precisely" — comprise art’s failure and frustration. To others, they are its wonder and delight. Art is what comes out of an encounter with mystery, providing a lasting record of that encounter.

Elbert Hubbard asserted, "Art is not a thing, it’s a way." In my experience, most working artists would tend to agree; critics and commentators would disagree. They approach from different directions. Both opinions hold weight. To the extent that making art is an encounter and points others toward that encounter, it is a way. But the work of art itself must stand or fall as a thing on its own.

There is, then, much to talk about when we talk about art. I know — I have been in countless such discussions over many years. I used to be a teacher who made photographs. Now I’m a photographer who teaches. My life has required both doing and explaining how to do. These are very different matters.

Understanding such differences is crucial, both to the artist and to those interested in art. Failure to see these differences results in talking at cross purposes — even crossed swords. Perhaps a consideration of art as both a thing and a way will help us remember why we go to art, and why we stumble into unproductive conversations.

When we come to a finished work we face a challenge. We sense that there is meaning there somewhere, but the art itself doesn’t go out of its way to help us understand it. Archibald MacLeish said: "A poem should not mean / But be."

When people respond to a poem, a painting, a song, they are responding to the thing that is art. This is appropriate. The piece stands on its own, apart from any intent of its maker (conscious or otherwise). As they consider the piece, if they are thoughtful, they will begin to trace their reactions back through their experience of the piece to see if their "reading" has any basis. They pay close attention to the work and their encounter with it. If they are experienced in their critical analysis, they will compare aspects of the work with other pieces by this artist or with similar things by other artists. They will try to articulate their sense of the maker’s vision.

At some point, people may venture to compare the vision of the work with their own. Whatever their perspective — if they are Christians, Marxists, Feminists, or hold any religious or philosophical position — they will no doubt find aspects of the work to commend or attack. This may prove fruitful, as individuals test their understanding against the challenge of the work and others’ views — even against the challenge of others with a similar philosophy. Depending on individual temperaments, such exchanges will be stimulating, invigorating, and enriching; or, they will be frustrating, threatening, and angering. The play or song or film has contributed to everyone’s knowledge and experience — the audience is now included in the artist’s encounter.

At some point, people may venture to compare the vision of the work with their own. Whatever their perspective — if they are Christians, Marxists, Feminists, or hold any religious or philosophical position — they will no doubt find aspects of the work to commend or attack. This may prove fruitful, as individuals test their understanding against the challenge of the work and others’ views — even against the challenge of others with a similar philosophy. Depending on individual temperaments, such exchanges will be stimulating, invigorating, and enriching; or, they will be frustrating, threatening, and angering. The play or song or film has contributed to everyone’s knowledge and experience — the audience is now included in the artist’s encounter.

But what happens when a person in the audience meets the work and immediately — even abruptly — announces an evaluation of it? (He found it uplifting. She approves of the message. He is offended by the language. She is upset by the frankness of the sexuality. It is too violent, ugly, loud, irreverent.) Whatever the merit of such comments, they carry little weight because they do not result from careful reflection on the work. They result in a superficial endorsement or dismissal. Indeed, there has hardly been an honest encounter with the work. Shallow reactions, no matter how sincere or well-meaning, create strain with anyone who does not already agree, and prevent worthwhile discussion or critique.

As Christians, we are perhaps likelier than some others to fall into this trap of earnest shallowness. Because we know Truth, we are aware that there are lies and error. "We must be vigilant!" An individual issuing the sorts of pronouncements described above might consider himself vigilant, a defender of the faith: "But God’s Word says…!" or "Truth mixed with error is error!" After all, if we were raised in church, we were brought up on preaching, and presented with a clear message. But art is not merely clever or slick preaching. The ambiguities presented in art are often jarring, even threatening. A mind unsettled by even honest fear about "clouding the message" may have difficulty seeing that art is much more a matter of exploration than exposition.

Art takes us, as John Ciardi says of a poem, "through the moment of experience to the moment of insight." Yet this moment of insight may be a while in coming. So a person inclined to hasty judgment in terms of theology or doctrine may reject much insight in the effort to repudiate what is truly objectionable. Such a person might dismiss Shakespeare’s portrayal of evil in Macbeth as endorsing or wallowing in evil; he or she might fail to see that a film or story or photograph may walk the line between being about immorality or evil and being immoral or evil itself. And, of course, most irony and satire would be lost on this person.

Such difficulties in talking about art are, of course, not confined to Christians. It is important to understand, however, that shallow or hasty reactions to art are really not talking about the art itself! Rather, they reveal more about ourselves—our beliefs, our tastes, our fears, our biases—than they tell us about the art. It can be difficult to remember that the "beauty" of an artistic encounter with evil or life’s deep questions lies in the truthfulness and clarity — even "rightness" — of the artist’s witness. Integrity, especially in matters of troubling and difficult reality, is not always immediately "beautiful." We may have strong initial reactions, but we must be honest about the beliefs and biases we bring to a discussion, then respond carefully and thoughtfully to the work itself.

Still, even honest and thoughtful people discussing a work may face an additional challenge if the artist is present. The artist may have trouble relating to what the audience is saying. While the others are talking about a thing, the artist is remembering the process of getting there: the way. The results range from awkwardness to condescension to outrage to paralysis.

Still, even honest and thoughtful people discussing a work may face an additional challenge if the artist is present. The artist may have trouble relating to what the audience is saying. While the others are talking about a thing, the artist is remembering the process of getting there: the way. The results range from awkwardness to condescension to outrage to paralysis.

The impulse to art is intuitive, not analytical. The process of making art is taking experience on faith in much the same way that the audience encounters the finished work: "I have faith — though I could be mistaken — that there is something meaningful here, and I bring to bear everything I can to make sense of it." Since self-consciousness of any sort is death to the creative effort (from doubts about talent to financial considerations to doctrinal concerns — the list is endless), artists learn to be wary of analysis and uncomfortable about explaining their work. Let us not forget that there are questions to which the answer cannot be given by direct assertion, only in the work itself. Similarly, there are actions and works which answer questions we have yet to pose. Some art, in fact, challenges us to ask the questions.

An artist’s misguided attempt to explain his work can lead to paralyzing self-consciousness. Several times I have been stuck for long periods after interested people asked me intriguing questions about my photographs. Having talked too much about meaning, I have found myself unable to be still and wait for the mystery to make its way back into my work. I impose my formulas. The result is invariably contrived and stillborn. I’ve learned that talk about the work is not the work. I’ve learned to respond with an honest "I don’t know" when people ask me what something means or "Why did you do it that way?" Artists with less experience may not know how to graciously deflect well-intentioned but—to them—dangerously irrelevant questions. A thoughtful audience will seek more sensitive, less threatening ways to engage the artist about the work. Ultimately, both artist and audience must return to the wonder that brought them together in the first place.

Art, as both a thing and a way, reminds us — even compels us — to "be still and know." In a real sense, the artist feels compelled to "make something of it." The resulting drama or dance or picture or poem calls us — audience as well as artist — to know something. We may be enraptured by it or offended. We may be delighted or disturbed. Our initial reaction to it may be skewed by intellectual, spiritual, and emotional baggage we bring to our experience of it. It may take us days, weeks, or even years to come to terms with what the work stirs in us. It takes faith, patience, and humility to be still and know amid all of the ambiguity of life and art.

And the language of creativity, whether from maker or receiver, moves into the spiritual realm of metaphor: "It spoke to me." "I was deeply moved." "It clicked for me." And finally, "I got it."

The Force is strong in this one...

Let’s start with the obvious: Wilco’s lyrics can be weird. Cryptic, even.

But I find them endlessly intriguing. They remind me of something Nathaniel Hawthorne wrote:

Nobody … ought to read poetry, or look at pictures or statues, who cannot find a great deal more in them than the poet or artist has actually expressed. Their highest merit is suggestiveness.

I don’t think Jeff Tweedy’s lyrics are arbitrary or empty. The more time I spend with his writing, the more I sense themes emerging. Sometimes I’ll find exciting implications on the first listen; sometimes a possibility ambushes me long after I’ve given up trying. The joy is in the uncertainty.

I’m thinking about this as I listen to “The Joke Explained,” the third track on Wilco’s new album Star Wars. I’ve been playing this record a lot, and I’m willing to bet that by the end of 2015, this will be the only Star Wars that I find supremely satisfying — full of immediately exciting sounds and intriguingly suggestive details that keep me coming back for more.

[This is only the beginning. Read the full exploration of Wilco's wildly imaginative Star Wars in my latest "Listening Closer" column here.]

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8I_DU5rXXOo

A film score scholar defending... Ladyhawke?

Ladyhawke turned 30 in April. I was all set to celebrate that anniversary, lonely Ladyhawke fan that I am.

But then things started going very wrong in my blog's last network home. And I just didn't feel much like hosting people for interviews there. So I took several months off, moved to this new place, and boom — now I get my Ladyhawke fix.

So here's the deal:

I received an unexpected package in the mail. It was from Timothy Greiving, a film score scholar whose thoughts on soundtracks I have long respected. Turns out Greiving knows my dark secret: I love — to an embarrassing degree — what may be the most maligned soundtrack in movie history. And, making me feel courageous enough to admit that, it turns out that he does too.

I still enjoy watching Ladyhawke now as much as I did then. In the wrong hands, it could have been a silly catastrophe. But director Richard Donner (Superman: The Movie) treated the material as seriously as if he were directing Shakespeare. The cinematography is glorious, full of iconic moments, including a star-making, moonlit moment when Michelle Pfeiffer makes a breathtaking entrance.

And I cannot say enough about what the cast brings to the material. Donner gambled by casting Matthew Broderick as a trouble-prone thief who carries on a one-sided conversation with God throughout. Broderick was a teen star at the time, riding a wave of popularity with two big hits: WarGames and Ferris Bueller’s Day Off. But it works because even though he’s the character who carries us all the way through, he’s not really the leading man. He’s the comic relief, which the film needs as a counter to the gravity of the rest of the cast. Rutger Hauer is in rare heroic form. Michelle Pfeiffer plays a beauty you’d believe knights would fight for. John Wood plays the villain—an imperious bishop with a satanic heart, helped by a sinister wolf-trapper played by Alfred Molina. And best of all, there’s the great Leo McKern in a show-stealing turn as a priest with a serious drinking problem.

But back to the soundtrack: Greiving, who writes about film scores for NPR, didn't just pick up a copy of the soundtrack for me. (I already have it.) No, he sent me La La Land Records’ new limited-edition 2-CD soundtrack.

When I listen to this music, my head fills with vivid images from a movie that ignited my 15-year-old imagination. What’s more, it’s an album that I asked my parents to play on the car stereo during road trips through Oregon, and much to my surprise, they came to like it—electric guitars and all. What’s more, I listened to Ladyhawke while I wrote stacks of fantasy novels in my late teens and on through college.

So I cannot give you an objective review—it’s all tangled up in experience.

Instead, let's consult the man himself, who wrote the liner notes for this release.

Please welcome Timothy Greiving.

•

Give us some background on your relationship with film soundtracks. Which were the first to grab your attention? How did you become a film music journalist?

In 1994 I heard the soundtrack for Jurassic Park (on cassette) in my cousin's minivan in Florida. I was ten. I had to ask what he meant by "soundtrack" ("You mean like dinosaurs roaring and stuff?"). I realized I already loved the soundtracks of John Williams from the Star Wars and Indiana Jones films (among others), went home and bought Jurassic Park, and just started collecting—at first—John Williams scores. He was my first love, and remains my favorite composer/musical artist of all time. It gradually expanded into film scores in general, and became a lifelong obsession.

I began writing for the e-magazine Film Score Monthly Online in 2008 (for no pay), which let me in on a world where I could interview composers (eventually some of my idols) and write about the art form I loved more than any other. It was intoxicating, and eventually blossomed into paying work writing liner notes for specialty, archival soundtrack releases. I moved to Los Angeles in 2011 to get a master's in arts journalism, and have slowly built a career as a freelancer writing and producing radio stories for various outlets (NPR, Variety) almost entirely on the niche field of film music.

What are some of your favorites?

My favorite score of all time is John William's A.I.: Artificial Intelligence. The film hit me at the sweet spot of 16, and became my favorite film. As he often does, Williams wrote a tapestry of unforgettable themes for characters and situations, and in A.I. with a mature depth and melancholy and aching beauty. The score ends with a heartbreaking lullaby theme that perfectly concludes and sums up the whole work. Other favorites are E.T. (for similar reasons), James Newton Howard's Signs (where he takes a tiny three-note motif of mystery and brilliantly coaxes it into a symphonic masterpiece about faith restored), and George Fenton's poignant, Oxford-flavored score for Shadowlands. (I have hundreds of favorites...it's so hard to narrow my focus!)

How much does the quality of the movie itself affect your opinion of the soundtrack?

There's something really wonderful when the alchemy of film and score work together to create a singular, magical experience. But I love many, many scores for films I don't care for or haven't even seen. One of the beautiful things about film music is that it's arguably the only "layer" of the filmmaking process you can peel off and enjoy as its own art form. Jerry Goldsmith is a close second to Williams in my heart, and he made a career out of scoring stinkers. I love his scores for The Final Conflict (the third Omen movie, which I've never seen, but looks pretty awful) and The Shadow. There's a long list of scores I love but have no affinity for the film they accompany.

You've just written the liner notes to a collector's edition double-disc soundtrack for the 1985 Richard Donner fantasy film Ladyhawke, which is a sentimental favorite of mine. It's hard for me to admit my love for that score because so many people rate it as one of the worst soundtracks ever composed.

You had to give Ladyhawke some serious attention to do the write-up that you did. How dod you feel about the soundtrack? And why do you think people have such strong feelings about it?

People have strong feelings because the juxtaposition of heavy, synthy rock music with the medieval story/imagery feels jarringly anachronistic to a lot of people. Several film critics drew attention to the score when Ladyhawke came out (critics often ignore the music altogether), and mostly because it distracted them in a bad way. Most people would expect big, Romantic-era, (let's face it) John Williams-style fantasy music for a film about knights and castles and magic, so to hear something so unapologetically poppy and "contemporary" is/was criminal to many filmgoers. And in 2015 it now has the added "crime" of being dated and not contemporary. But many will defend the score and its power in the film, and many have come around to appreciating the effect Richard Donner was going for.

I never knew this film or its score until I was assigned to write the liner notes for this release, so it was a revelation to me. If I'd encountered it just a few years ago, it probably would have triggered my gag reflex, because I had such a strong distaste for ’80s film scores with heavy synth/rock flavors. But over the last two years or so I've completely fallen in love with the work of Kraftwerk, Tangerine Dream, Vangelis, Giorgio Moroder, etc. (everything I used to despise!), so Ladyhawke came along at a great time.

I'm still not a big fan of the film itself, but can appreciate its qualities.

You obviously put a lot of work into these Ladyhawke liner notes?

I always love interviewing directors and the people who made the film and the composers who wrote the score, and on Ladyhawke I got to interview Richard Donner and his wife, producer Lauren Shuler Donner, as well as the star Rutger Hauer. Both were great interviews, full of fun memories and interesting trivia. I also got to speak with composer Andrew Powell in depth about his compositional choices, working with Donner, the criticisms of anachronism he's had to deal with for 30 years, and a lot more. It was a very rewarding project overall.

Have you had any interesting responses to this release? Is there a Ladyhawke soundtrack fan club out there that's going to snatch these up?

I haven't heard much myself, but I know it's sold very well for the record label that put it out (revealing that the score's naysayers are only very vocal, and not necessarily in the majority). I don't know about a fan club devoted just to this score, but there is a community of film music nerds (okay, aficionados to be polite) who gobbled this up, as well as fans of the Alan Parsons Project. ’80s film scores sell exceptionally well in general, in part because the current zeitgeist is nostalgically obsessed with the movies of that decade.

What do 1989, Moonrise Kingdom, and Gattaca have in common?

Imagine this if you will: I've started hosting a regular evening discussion group where all of us who love to look closer gather and watch films, or listen to albums, and then stay up late discussing them. Imagine I give each one of you an opportunity to choose which album or movie we're going to give our close attention. What movie or music would you choose? And why?

I posed this question to the Looking Closer Specialists, and here are their recommendations for this imaginary discussion group. Some of them wrote out their recommendations for you, and some addressed them directly to me.

You are free to take their suggestions and start your own group. We'll be with you in spirit. You could even call it "Looking Closer" if you wanted to...

Bob Denst retired from the Tucson Fire Department after a full career and is currently experiencing Life 2.0 as a student in the Seattle Pacific University MFA program for Creative Writing. He recommends:

Bob Denst retired from the Tucson Fire Department after a full career and is currently experiencing Life 2.0 as a student in the Seattle Pacific University MFA program for Creative Writing. He recommends:

Gattaca. Yes, there are better movies, but this is one that I can recommend unequivocally to just about anyone. It manages to combine a whodunnit with science fiction. But those genres serve as the packaging for a great think piece. I have had multiple wonderful discussions with people, especially my family, about the ideas and questions that movie raises. And the movie only becomes more prescient as our genetic reach and grasp increases. It's also visually stunning. It never gets caught up in a futuristic look which so often dates itself within a few years. It still looks fresh even though it came out 18 years ago. The performances are a delight to watch: Ethan Hawke. Jude Law is fantastic. Uma Thurman. And Alan Arkin is so much fun. Even Gore Vidal, Tony Shalhoub and Xander Berkeley in supporting roles give more than they had to. All in all, thoroughly entertaining and thought provoking.

Peggy Harris has written about film and theology for Cokesbury, the educational imprint of Abingdon Press. She recommends one of my recent favorites:

Peggy Harris has written about film and theology for Cokesbury, the educational imprint of Abingdon Press. She recommends one of my recent favorites:

Moonrise Kingdom. Here's why: I am the daughter, granddaughter, and niece of movie theater owner/managers. Movies have run in the family since silent film days. (Family legend claims my grandmother met my grandfather when she played the piano at a silent movie.) I saw every movie, including age-inappropriate ones, free — from early childhood until I left for college. That means I was awash in an unedited flow of stories, from the original Parent Trap to Cool Hand Luke, from The Love Bug to Midnight Cowboy and The Graduate. I escaped life through films, and I think escapism is a driving force for most movie watchers today. (That doesn't set a high bar for art, unfortunately.) But I confess that's where I began. Thinking about movies, engaging with them, and engaging with others who love film — that all came later for me. Your website and your book, Through a Screen Darkly, played a part in moving me beyond escapism and deep into the potentially life-changing aspects of the stories woven on the screen. Just one example: Not until I read the comments from you and others on this site did I begin to fully appreciate the work of Wes Anderson. I mean, really — most of his films are so PRETTY. It was easy to sit back and enjoy the escape of watching them. Now I interact with their underlying themes, which have enriched my life. And I'll end on an ironic note — as Geoffrey O'Brien wrote in a post you recently shared about Moonrise Kingdom, one of those recurring themes is ESCAPE.

Winston Chow has been singing since he was 5, but never formally learned to read or play music. When he's not enduring the commute to software engineering work in Silicon Valley, he helps college kids learn to sing in the church choir. He recommends:

Winston Chow has been singing since he was 5, but never formally learned to read or play music. When he's not enduring the commute to software engineering work in Silicon Valley, he helps college kids learn to sing in the church choir. He recommends:

Both 1989 albums by Taylor Swift and Ryan Adams.

At the very least, compare/contrast the album tracks — "Blank Space", "Out of the Woods", and "Shake It Off". I know some may roll their eyes and ask, "Why that fluffy pop-princess Taylor Swift?", but I've been inexplicably drawn to listen to Swift's 1989 much more than I thought I would. When Ryan Adams released his cover album of "1989", I figured out why.

(Thanks, Jeffrey Overstreet, for posting Adams's cover of "Shake It Off"!)

Joseph Susanka has been doing development work for institutions of Catholic higher education since graduating just such an institution in 1999. A grateful resident of Wyoming, he spends his free time exploring the beautiful Wind River Mountains, keeping track of his (currently) seven sons, being amazed by his (currently) lone daughter, and thanking his lucky stars for Netflix. He picks another of my recent favorites:

Joseph Susanka has been doing development work for institutions of Catholic higher education since graduating just such an institution in 1999. A grateful resident of Wyoming, he spends his free time exploring the beautiful Wind River Mountains, keeping track of his (currently) seven sons, being amazed by his (currently) lone daughter, and thanking his lucky stars for Netflix. He picks another of my recent favorites:

I’m going with Certified Copy when my turn rolls around, for two reasons.

First, because it seems only appropriate for the unveiling of the new “Looking Closer” site that I select the transformative viewing experience for which Jeffrey was most responsible. I’d seen references to Kiarostami’s film floating around for quite a while without thinking much of it, but when his atypical review – OK, it wasn’t really a review; more of a reflection — appeared in Image, I was inspired to give it a watch, and it was as thoughtful, provoking, and spectacular as he suggested.

Second, it seems wise to pick a film that is not only sure to inspire discussion – this one will, without a doubt – but also one that has enough complexity, nuance, and ambiguity to reward a close examination by a group of thoughtful and like-minded folks. (Also, the acting is amazing. I could watch Binoche and Shimell in this film forever and never grow tired.)

Joshua Wilson is a singer, teacher, husband, and father of five. He occasionally blogs on films at fforfilms.wordpress.com. He makes a surprising choice:

Joshua Wilson is a singer, teacher, husband, and father of five. He occasionally blogs on films at fforfilms.wordpress.com. He makes a surprising choice:

Tough choice. I'm going to pick Billy Wilder's bitterly dark Ace in the Hole.

In this film, Wilder presents a bleak picture of our contemporary media culture. A man who is tragically caught half buried in a collapsed cave provides the scoop of a lifetime for Kirk Douglas's bottom feeding newspaperman. He intends to capitalize on the story for profit and career advancement, and sets the stage for a literal media circus, complete with tents and Ferris wheels.

But as easy as it is to criticize the disgustingly self serving and corrupt actions of the newspaperman, Wilder's satire is directed just as much towards us who so frequently use the tragedy of others as a consumable form of entertainment. When the resolution comes, the crowd picks up and moves on, taking with them their "I was there" stories, and leaving only their camping garbage, caring little for the hurting people who remained behind.

It's been described as misanthropic, and it does veer towards melodrama near the climax, but I feel that some topics require an extreme depiction in order to break through our callousness and shake us up a bit into paying attention. This is a film that has only grown in relevance proportionally to the growth of the influence of media in our daily, even hourly experience.

Evan Cogswell is an organist, composer and film enthusiast who occasionally blogs about film at https://catholiccinephile.wordpress.com/ His recommendation is the most obscure of them all:

Evan Cogswell is an organist, composer and film enthusiast who occasionally blogs about film at https://catholiccinephile.wordpress.com/ His recommendation is the most obscure of them all:

I've been mulling over what to chose, and I'm going to stretch the definitions to do both an album and a movie. This DVD recording of the 1984 musical Sunday in the Park with George. This production was recorded and aired on PBS in 1986, and it's been a long time goal of mine to make as many people as possible aware of this musical about art, creating art, engaging with art, and the influence of art on both the public and the artist.

The musical doesn't tell a traditional story (which makes many people bored quickly); it's comprised of a series of fictitious vignettes about George Seraut as he paints his masterpiece Sunday Afternoon on the Island of la Grande Jatte. More interested in his work than anything else, Seraut is so committed to his vision that he tries to use his art as a substitute for relationships. Jumping forward 100 years (with a very funny song about modeling from the characters in the painting), act 2 is about Seraut's fictitious great-grandson who believes good art = $$, and has no commitment to his own vision or creating a good work of art. The theme of human connections runs through many of Sondheim's musicals, but this is his most optimistic, because art does make life worth living, healing and connecting people from different times and cultures.

Levi Douma recently quit his studies at the conservatory in Utrecht, Holland and became a practitioner of transcendental meditation. He chooses:

Levi Douma recently quit his studies at the conservatory in Utrecht, Holland and became a practitioner of transcendental meditation. He chooses:

Yasujiro Ozu – Tokyo Story (Tokyo Monogatari)

In a book called Through a Screen Darkly, there is a part where the writer complains about how few people these days take time to endure a so-called slow movie like Ozu’s Tokyo Story. Childlike me felt up for a challenge. I would watch the whole thing without falling asleep, just to try to get better focus. That “not-trying-to-like-it” attitude would prove most effective, because I had in the doing opened myself to the voice of the art, and all other inside voices and thoughts were just quietly expecting.

I was deeply moved by the film, especially the character of Setsuko O Hara (Noriko) made a strong impression. Her kindness overwhelmed me. “That’s the person I want to be!” I thought. She made conservative-like virtues heartfelt and beautiful. Yasujiro Ozu shows quiet admiration for things many people think are boring; he takes you to that subtle level where the quiet virtues are. He shows us how valuable family bonds are, how we must cherish them.

I realise, although strong it was, this experience is only the beginning of grasping the deeply felt kindnesses one can give and receive in a family. Tokyo Story was for me a revelation, a first step into a healthier direction. I need to appreciate and understand Ozu’s movies more, that’s why I picked this movie to look closer.

Daniel Melvill Jones is spending his early 20s working for a technology company while he anxiously waits for the right time to return to school. (Trusting the Grand Weaver's plan is hard but fruitful.) In the meantime he is serving his local church, reading an ever growing stack of volumes, and posting on occasion at danielmelvilljones.com. I'm honored that Daniel would cast me as Bilbo in the scenario that he shares here (although I hope he means Tolkien's Bilbo, not Peter Jackson's):

Daniel Melvill Jones is spending his early 20s working for a technology company while he anxiously waits for the right time to return to school. (Trusting the Grand Weaver's plan is hard but fruitful.) In the meantime he is serving his local church, reading an ever growing stack of volumes, and posting on occasion at danielmelvilljones.com. I'm honored that Daniel would cast me as Bilbo in the scenario that he shares here (although I hope he means Tolkien's Bilbo, not Peter Jackson's):

What a dream discussion group! We would be like a fellowship of boisterous hobbits who have sat at the feast of Elrond and are now gathered together in some snug pub. Loudly we voice our opinions of the elvish lore we heard, pestering our guide Bilbo (Jeffrey), who has helped initiate our appreciation of music and stories. What tales or legends should we repeat amongst us? It would be tempting to dwell on the ones we all enjoyed the best; the all-encompassing spirit of a Terrence Malick saga, the delicate miniature of a Wes Anderson, the grit and humour of a Cohen Brothers volume, or the black and white beauty of a Wim Wenders or a Charlie Chaplin. Maybe we could search the depths of heartache and grace brought to us from just over the Rhine, sink our teeth into the Edge's guitar chords, or dance to rhythm of Saint Paul Simon.

Yet having learned so much in this company, I seek further understanding. Already I've grown from our feasts together, but my appetite remains unquenched. Specifically, I would like to better understand one who has been a minstrel, poet, prophet, and storyteller to several generations. I'd like a primer on Bob Dylan. Which album should we dwell on? I say we choose Jeffrey's favourite, which is, well, let's look... ah, I've found it: Oh Mercy.

The Bible says it, but that doesn't settle it.

It happens far too often.

It happens in sermons broadcast around the globe. It happens in political speeches. It happens behind closed doors where pastors reprimand congregants.

It happened to me just a few weeks ago. I heard someone say (and I'm paraphrasing): "But the Bible says _________, so you have to believe it! You have to accept it! Do you believe the Bible is the Word of God? If you do, then you'll do what it says!"

And I immediately wanted to interrupt. I wanted to say...

"Yes, the Bible is the Word of God. I believe that. But even more than that, Jesus is the Word of God. And to me, if the Bible's true purpose is to reveal Jesus to the world, then this influences how I read the Bible. I need to understand why each book of the Bible was included, and how each book serves to help reveal what was distinct and essential about Jesus.

"So when you say 'The Bible says...', I say back to you, 'Why do you think the Bible says that? Do you think everything the Bible says is an instruction? Do you think every part of the Bible is equal, and to be understood as a Law? Or do you think that we should seek to understand how each book of the Bible, each line of the Bible, distinctly serves to help us understand and appreciate the Living Word Himself?"

That I believe the Bible is the Word of God does not mean that I can pull any line out of its context and take it as direct instruction for my behavior. If I do that, I will wreak havoc through misinterpretation, bending verses toward purposes they were never meant to serve.

That I believe the Bible is the Word of God does not mean that I assume all Scriptures are easily understood, or that everyone is meant to arrive at the same understanding about them. So even if the Bible "says it" ... that doesn't "settle it." Far from it. If the Bible says it, the proper response is for me to humbly, faithfully, and diligently investigate what it means... and for me to be willing to hold back from ever asserting complete certainty about its proper interpretation, as I remain a sinner, incomplete, seeing through a glass darkly. The Bible, taken as a whole, is more like a great poem than a great how-to manual; my understanding of it evolves and deepens the more I attend to it, and I often find myself surrendering interpretations about which I was once zealously certain.

That I believe the Bible is the Word of God does not mean that I will accept as my marching orders any Biblical verses that do not harmonize with the teachings and actions of Jesus himself. For example, any use of Scripture employed to scorn, ostracize, or judge our neighbors in this world runs directly contrary to the spirit of Christ. The only times I see Christ himself expressing scorn and contempt, it's when he's responding to those who seize Scriptures and use them to put others down as being unacceptable and raise themselves up as enlightened and righteous. In short, Jesus speaks scornfully specifically to those who wave God's Word scornfully at some "unacceptable" Other from a position of false superiority; he shows them that he is the Only One with permission to assert such authority.

I believe that the words of any passage in scripture exist in a context; and that context exists within a particular document; and that document is written in a particular genre that may be eyewitness testimony, or poetry, or a particular personal letter to a particular community, or a record of history passed on through written and oral traditions. Thus, to assume that any particular paragraph is meant as a lesson in what we should do is to disrespect what the Scriptures are.

The Old Testament is full of stories and poems and chronicles of rules and records of passionate human expression that show us the flailing of humankind, demonstrations of desperation and hope in a world without Christ. There are great revelations of wisdom, but not everything everyone says — not even the psalms of David — are meant to be examples we should follow. They are sometimes meant to reveal the insufficiency and failing of the human heart and to reveal our need for Christ, who will answer those expressions. When the psalmist angrily asks God to bring about the slaughter of mothers and babies, I do not take that to mean that he's in a Christ-like spirit — rather, I take that passage as showing me that even if I confess my most vengeful and violent desires to God, God will still show mercy to me and listen to me and love me. And then he will answer — as he did through Christ — by showing us a different possibility.

Yes, all scriptures are profitable for teaching, reproof, correction, and training in righteousness... because they help reveal (often by contrast) the scandal of his love and grace. Some scriptures reveal Jesus by reflection, some by anticipation, and sometimes by stark contrast to his example.

Christ makes all things new, asking us to love our neighbor, to serve the outcast, to help the poor, to put our arms around those who offend us, to refrain from retaliation, to accept and endure persecution as Jesus himself did even to the point of death because he meant to demonstrate a victory over death rather than a defense against it.

This is where I get into trouble with a lot of my fellow believers, but I take everything written by believers after Jesus with half a grain of salt.

I have never been convinced that we're to accept every line written by the Apostles in their letters as 100% Pure Jesus Gold.

Were they inspired by God? I have no doubt. They are rich with priceless wisdom that reflects Jesus's influence and the movement of the Spirit in the heads and hearts of the writers. But I think that they give us evidence that their authors are imperfect human beings struggling — bravely and insightfully — to live out what they learned from Jesus. In their writing, we see both wisdom and shortcomings, moments of glorious revelation and moments of imperfection. We see them growing and changing. These writers were inspired by, influenced by, and led by Jesus... but they were not Jesus. They were not 100% reliable Bose Surround Sound Speaker Systems channeling God's own voice. And in no way were their writings meant to be taken as a Replacement Law for the one Jesus fulfilled in his grace and sacrifice.

They were writing in faith. If God took over their minds and dictated everything they wrote, they would not have been writing in faith — they would have been writing in certainty. Or, better, they wouldn't have been writing at all. God could have shown up and handed them things already written, but he didn't. His disciples and apostles wrote, building on what they had learned from Jesus, with astonishing insight, but from an incomplete human perspective.

I struggle with many passages in the New Testament, trying to reconcile how they align with things Jesus himself said and did. It is important that I go on struggling. But I must guard my heart against seizing hold of the Apostle Paul's writings and using them in a way that overrides what Jesus said and did, using them to excuse self-righteous or ungraceful words or actions against others. If I do find myself clinging to Paul's words in order to defend my position, and that position seems to clash with Christ's own teaching, then I'm probably committing one of two possible errors: I'm misunderstanding Paul's meaning, or I'm embracing and favoring one of his not-so-perfect passages.

So the Bible may say it. But do I agree with it? Does that "settle it"?

Sorry... I reject that question.

Not everything in the Bible is written there for us to agree with and obey. All Scriptures are there to challenge us, to tease our minds into active thought. They are not there to secure our current set of opinions, but to call them into question. That is to say, all scriptures exist to drive us into a deeper relationship with (and thus dialogue with) Jesus.

I suspect that if I take any passage to Jesus and ask "What am I to do with this Scripture, Jesus?", he will answer something like this:

"How much does this Scripture resonate with what I've shown you and done for you? Is it there to serve as harmony with, or as dissonance with, what I AM? It's literature, for crying out loud. It's not a book of rules. It's supposed to be hard work. Be transformed by the renewing of your mind, that you may know what the will of God is. Don't be hard on those who don't understand it fully yet... because have I not been forgiving of you over all these years of your as-yet-incomplete understanding? Here's what I ask of you: Put away your knife, zealous disciple. Seek justice. But love mercy. And walk humbly with your God. Because I love your company, and I'd hate to lose you."

-

So that is why I didn't speak up today. That's why I didn't interrupt.

If I had spoken up, I probably would have responded with words that, while driven by a desire for justice, would have been spoken with something less than mercy and humility. I needed to calm down, to remember how much I still have yet to understand, and to write all of these things with a disclaimer taken from an Over the Rhine song: "And like all true believers, I am truly skeptical of all that I have said."

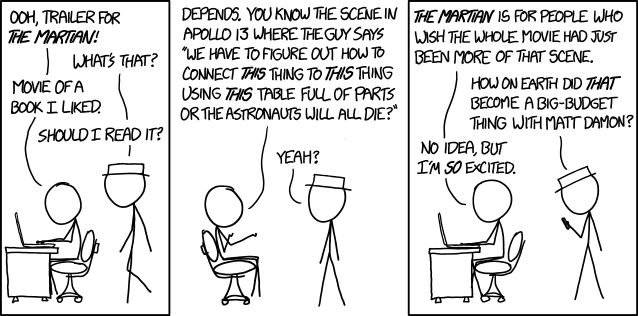

The Martian (2015): A Looking Closer Film Forum

The Martian has a reputation: Science enthusiasts — even more than science fiction enthusiasts — think the novel is the best thing since the Large Hadron Collider.

Of course, it takes more than a lot of scientific details to make a great novel. And it's even more of a challenge to turn a great novel in to a great movie — or even a good one.

Turning to my go-to community of film-loving writers, I find some enthusiastic responses to Ridley Scott's film — which is built on an adapted screenplay by Drew "Cabin in the Woods" Goddard. But I also found some expressions of frustration and disappointment that remind me of how many "event movies" like this one have failed to live up to the hype for me. (Can anybody say... Interstellar?)

King of the Geeks, Drew "Moriarty" McWeeny at HitFix, turns in a review that suggests this movie might restore my interest in the work of Ridley "I Once Spent a Few Years Making Masterpieces, But Decided It Wasn't for Me" Scott:

Working from an aggressively smart and funny screenplay by Drew Goddard, adapted from the also smart and funny book by Andy Weir, "The Martian" is so confident, so relaxed, and so completely sure-footed that it almost looks effortless. It takes a genuine master craftsman to take something as complex and difficult as this and make it look easy, but it also takes an artist with a great ear to take something as dense with exposition as this is and make it practically sing.

So how does the guy who fumbled "Prometheus" and "Exodus" so hard that it felt like he was trying to sabotage the studio turn around and absolutely nail this in terms of tone?

Ken Morefield at 1MoreFilmBlog writes:

Towards the end I was ready to forgive all the streamlining and predict that The Martian would end up somewhere on my annual list of Top 10 favorites. But the end was a tipping point as far as my own reader-response. It was small, but it was so needless. Then the needlessness of it left me wondering if Scott, whose films post-Blade Runner have been good but keep getting watered down, has lost faith in his audience to accept or process the least bit of thematic complexity. The film’s epilogue reads less like a humbling celebration of human cooperation and more like a motivational speech from a veteran selling American exceptionalism.

And Jaime Christley at Slant gets right to the heart of what frustrates me about so much Interstellar-like science-fiction:

It hardly seems interested in its characters or in any depiction of their work, settling instead for types of characters and kinds of scenes.... The Martian goes in for the idea of texture and tics and human behavior, but there's no conviction, and no real push for eccentricity. What's left is a string of Pavlovian prompts to ensure that our emotional cues arrive on schedule.

Nor is there much awe. ... When Watley muses to his video diary about the billions of years that'd passed on Mars before he set foot on this or that hill, he's only right in fact. In spirit, in imagination, we'd already conquered it, and Scott's intrepid botanist is merely a johnny-come-lately, in a film where curiosity is in shorter supply than the oxygen.

But I'll go see the film anyway — probably because I'm encouraged by Alissa Wilkinson's carefully modulated praise at Christianity Today:

In a blockbuster world ruled by dystopias and conspiracies and shadowy bureaucracies, The Martian's cheerful attitude about the general decentness of people comes across as almost a throwback. Unlike nearly every sci-fi film of the recent past, The Martian doesn't spend any time wondering if humanity deserves to survive. It takes it for granted that we do, as long as we can figure out the mathematical equation that will help us do so. We survive because we solve problems, and we work together to do so, sometimes even with people whom politicians might tell us are our sworn enemies.

War Room (2015): A guest commentary by Anonymous

The following post-viewing commentary on War Room was submitted by a Looking Closer reader and a Christian friend whose passion for excellence in the arts is an inspiration to many. And he has an incisive sense of humor.

You've been warned.

I'm honoring this friend's request to remain anonymous. (No, it's not me writing under a pseudonym.)

•

When you are walking to your car and confronted by a man with a knife who asks for your money, the correct thing to do is to say, “Put down that knife, in Jesus’s name!” Because the man will look at you as if these are not the droids he is looking for, and then go running, so perhaps that’s what Obi-Wan should have said instead of “Use the Force.” Or maybe that could be a pitch for Star Wars: Episode Ten: Jesus Awakens – A Kendrick Brothers Production.

Elderly African-American pronounce the word “war” as if it is spelled “whoaaah,” and don’t tack an “r” on at the end, although since, in this movie, the word “whoaaa” is always followed by the word “room,” there’s no need for such a pesky, unnecessary consonant.

When you’re in your prayer closet (the one that you’ve taken everything out of so that you won’t have any distractions), make sure to still have your cell phone in there, because it’s not distracting at all. But that way, when you are finishing up your prayer time you can get a text from “Missy,” who just saw your out-of-town husband in a restaurant with some woman, and even though your husband is a sales rep and probably has dinner with women all the time, Missy can spot a slut when she sees one, and is right to interrupt your time with the Lord to spread some juicy gossip.

If you pray for your husband at the exact moment he is at a restaurant considering having an affair, he will get stomach pains, and then go throw up.

If you pray that your husband’s deceit will be exposed, that will happen, too, and he’ll lose his job.

If you pray for Satan to leave your living room, your husband will eventually give you a hot fudge sundae and a foot rub.

You should always have a room-temperature cup of coffee standing by. This is so that, when you are asking your real estate agent about her relationship with God, and it’s clear that she’s kind of a lukewarm Christian, you can offer to get her coffee, and come back with a room-temperature cup of the stuff for her (but a hot one for yourself), and when she drinks hers and grimaces, you can then go into a mini-sermon about how it’s better to be hot or cold, and she will smile and nod at you, as if bringing her that cup of coffee was the perfect way to make your point, except I would have been asking, where’d you get that lukewarm cup of coffee from, when the pot that you poured the coffee from was hot? Only the old woman probably would pronounce it “poahhhhr.”

If your feet stink, your daughter will tell you. Also, your closet will smell horrible, so it might not be the best place to turn into a prayer room, the aroma of Christ notwithstanding. Oh, and then when your husband goes to rub your feet, he’ll put on a surgical mask, thinking he’s being cute, but I would have been asking – all that prayer just saved our marriage; can’t the Creator of the universe do anything about those stanky feet?

If your feet stink, so does your breath. The UPS guy who delivers your prayer journals can testify to that, because you fell asleep in your prayer closet, and when you went to answer the door, you breathed all over him, which is the correct thing to do to a UPS guy who comes to your door.

More than 35 churches are listed in the credits, which means that there were thirty-five times more churches involved with this movie than there were script consultants. Wait, that’s not how math works – thirty-five times zero is zero, so there were zero times as many script consultants on this movie than there were churches involved. Shoot, I think my math is still off. There were more than 35 churches listed in the credits, and zero script consultants; that’s what I learned watching this movie. Unless one of those churches also had a script consultant who went there, which can’t be true, since anyone who knows anything about writing wouldn’t be welcome in any of those churches.

If you’re a paramedic and a Christian, but this movie doesn’t give you an opportunity to demonstrate either of those traits, the way to let the audience know is to say, “I’m a paramedic. But I’m also a Christian.”

Old African-American women numerically order their favorite rooms in the house. They will tell you, “This is my third favorite room in the house,” about the dining room, and “This is my second favorite room in the house,” about the sitting room, but it won’t be until you are leaving that you ask, “What’s your favorite room in the house?” even though you most certainly already opened the door to the prayer closet that is her favorite room in the house because – being a realtor – you would have wanted to see behind every door, except you didn’t look in that one closet, which is the old lady’s favorite room, and also you really can’t count it as a room when you list the house, since it’s just a closet, unless now we’re counting closets as room, which means that one of the things that I learned from this movie is that I live in an eight bedroom house.

About twenty people are credited as “Jump Ropers” in the credits, because there’s a sequence at an event where that’s what people do. It’s quite a popular sport, apparently, as there were literally dozens of people cheering the jump ropers on. Except isn’t the proper term for a person who jumps rope “Rope Jumper”? Nope, according to this movie, anyone who jumps rope is a jump roper.

When your former boss (the one who fired you because you were fudging your sales numbers, and who you confessed to stealing from, too) forgives you and decides not to prosecute you for your crimes, that is an example of God’s grace, because that’s what a character says in this movie. But isn’t that actually an example of your former boss’s grace? Or maybe black people think that white people are agents of God, so I guess that’s what I learned from this movie.

If a closet has been used as a prayer room by an old lady, a retired pastor can walk into that closet, and then step out, and then step in, and then out again, and declare, “Someone has been praying in here,” as if it was a hotel room where someone had been smoking, and you can still smell the odor, except this was a different closet than the one used by that woman with the stinky shoes, so I don’t know what kind of odor that old lady left behind.

More than a dozen people with the last name “Kendrick” are listed in this movie as part of the “Clean Team,” and I have no idea what a “Clean Team” is, but at least now I know the answer to the question, “Who do you have to sleep with to become a member of the Clean Team?”

“Thousands of people” prayed for this movie. I learned this because it says so at the end of the movie, along with the declaration, “God answered!” It should be pointed out that God also answered Jesus’s prayer of “Take this cup away from me.” The answer was “no.” But this move got made, so apparently God responds much more favorably to jump ropers and members of the clean team than he does his own son.

Bill Clinton’s operatives will do whatever it takes to get him elected president. Oh, wait, that’s something I learned from The War Room, a movie with a title so close to this one that a lot of Christians will probably end up watching it thinking that it’s this movie, and wonder when Bill Clinton is going to go into his closet to do whatever it is he does in there, which probably isn’t to pray, but I bet that retired pastor can figure it out, just by looking. Ew.

Orson Welles said that there were two things he never believed when he saw them in a film: prayer, and sex. There’s no sex in this film, so Welles would have been happy about that, but about that other thing, this movie seems to be an exercise in proving Orson Welles exactly right.

(NOTE TO THE FILMMAKERS: Orson Welles was an actor, writer, and director, who made a film called “Citizen Kane,” which illuminates Mark 8:36 (“What good is it for a man to gain the world but forfeit his soul?”) The film is available for purchase or rent at sites other than christiancinema.com.)

We need to raise up an army of prayer warriors, is what the final sermon – excuse me, speech – excuse me, it’s a prayer; it’s the final on-screen prayer by the old woman who has a new prayer closet in her son’s house, who’s probably wondering where his mother wandered off to. But at the end of the movie she prays that God will raise up an army of warriors, who (according to the visuals on-screen as she prays) should pray in the schools, and around tables, and with their babies, and for the city of Atlanta, and at colleges, and police stations, and Washington, DC, and in every corner and culture in America. Except for Hollywood. There’s no suggestion that anyone should pray for Hollywood, because that place is full of heathens, so they can all go straight to hell.

Simone Weil on pagan mythology

Here's Simone Weil writing — in Waiting for God — on how, by resisting Christ in her pursuit of the truth, she came to realize that he is the truth waiting for her within everything — even pagan mythology:

For it seemed to me certain, and I still think so today, that one can never wrestle enough with God if one does so out of pure regard for the truth. Christ likes us to prefer truth to him because, before being Christ, he is truth. If one turns aside from him to go toward the truth, one will not go far before falling into his arms.

...After this I came to feel that Plato was a mystic, that all the 'Iliad' is bathed in Christian light, and that Dionysus and Osiris are in a certain sense Christ himself; and my love was thereby redoubled.

I love this.

This is so much more rewarding a perspective than deciding that we need to counter "worldly art" with "Christian art."

First of all, even art by the most Christlike of human beings will be clouded with error. We are human makers, and our vision will weave truth and error together no matter who we are — so "Christian art" (if there can be such a thing) will be immediately at problematic as anything else.

First of all, even art by the most Christlike of human beings will be clouded with error. We are human makers, and our vision will weave truth and error together no matter who we are — so "Christian art" (if there can be such a thing) will be immediately at problematic as anything else.

Secondly, if anything is truly *art*, then it has some semblance of excellence, imagination, beauty, and truth in it. Instead of taking a contentious stance toward the imaginative expressions of other "worldviews," Christian freedom allows us to open ourselves to receiving reflections of Christ in the good, the true, and the beautiful within everything.

If we are to call any art "Christian," let it refer to the beauty of the work, not to the intention of the artist — for so much narrow-minded work tainted with self-righteousness falls under the label "Christian," and so much that is revelatory of the glory of God comes to us labeled "secular."

War Room (2015): A Looking Closer Film Forum

When War Room, the latest movie by the Kendrick brothers (who also made Facing the Giants), scored the #1 spot at the box office — on a very weak moviegoing weekend, with little in the way of competition — the film's media campaign became celebratory, as if this was some kind of major victory for Jesus.

"This might be the biggest upset since David grabbed his slingshot!" proclaimed a poster on social media.

And then, making a bad thing worse...

And then, making a bad thing worse...

"Are you ready to battle the right way? Grab your friends and family and see War Room today!"

That pretty much resolved things for me: I have no desire to see anything that uses such tactics to get attention.

I really don't understand this ad. In this scenario, who is Goliath? Who is the Enemy of God in their fantasy?

And in what way are they like the One Chosen to Lead the People of God?

(I like Dean Batali's response on Facebook: "Does this mean War Room is going to grow up and have an affair with Bathsheba?")

When we recast the Gospel as "us" versus "them," we unplug the power of the Gospel. What is the Gospel's claim, after all? That Jesus's love was victorious in a "battle" was between God's love and the Devil's chief weapon: death.

And that battle is over. Once and for all.

The battle is not between Christians and society. As a matter of fact, the "full armor of God" that believers are called to put on is made of love, truth, and righteousness — subverting any concept that we are to seek victory in material terms (the box office least of all).

All of that to say — I won't see the Kendricks' film because I want I try to focus on films that offer beauty and truth. And it would be painful to see a false gospel proclaimed.

And this really sounds like a false gospel. Some respectable and insightful Christian voices are going a long way to convince me of that.

•

Here's John Mark Reynolds at his blog Eidos on War Room. And before any fans of the movie write him off as a ranting anti-Christian, you might want to see who he is first.

He writes:

War Room isn’t a good movie. I hate to say that War Room is not a good movie because I want to encourage Christians to make movies. The movie isn’t very well made, the acting is marginal, and the writing is wretched. Nobody talks like the characters in the film and the plot holes are very great. Trust me. If you steal drugs and money for your stash, you will go to jail.

War Room is a film that allows African-Americans a voice. That is a good thing, but a bad thing is that [the] voice given to these characters is so sanitized and homogenized. This movie plays it so safe with the audience it hopes to lure that it betrays any authenticity.

If you enjoyed the film, I am not saying you are wrong to enjoy it. Enjoy. Yet know this: the fact that so many Christian films are wretched, overly written, and full of religious jargon is harming this generation. Do you want to know one reason for people leaving the church?

•

My friend Allison Smythe made this comment on Facebook, but I think it's worth sharing as a post of its own. (I'm breaking it into paragraphs for easier reading.) Allison's talking about the storyline of War Room, in which a woman solves the problem of her abusive husband by "submitting" and praying a lot. Allison says:

Women in these circumstances typically resort, consciously and unconsciously, to unhealthy survival techniques to negotiate/survive the crippling societal and church sanctioned imbalance of power which include denial, rationalization, appeasement, minimizing harmful behavior, and manipulation. The movie presents Jesus as a sanitized and efficacious version of those techniques.

What the woman might come to realize in that prayer closet once she's willing to surrender these destructive techniques, become honest about her own broken and harmful behaviors and accept her equal worth as a child of God is that she must take responsibility for the state of her life and of her children. She is not responsible for her husband's behavior but she is responsible for her own. The movie attempts to show a woman empowering herself through forming a relationship with God but then makes a vast presumption about what that surrender to God should look like — the same exact submission to husband minus the attitude.

Had the 'genie prayer' not worked for another decade, what further amount of damage should she and her child have endured? "It was for freedom that Christ set us free," not another sanctioned version of bondage.

If this movie sparks this desperately needed dialogue in the church it's at least good for that. Christians can be so terrified of hard conversations and of being shown up. Offended by language? Offended by writing technique? What great excuses to evade the heart of the matter. Get your outrage in perspective. Then those outside the church might one day find you honest enough to give you a listen.

•

Joel Mayward published a post called "The 'Faith' of Faith-Based Films: On Moralistic Therapeutic Deism in Christian Movies." Referring to the film's enthusiastic Christian fans, he says

when this faulty theology is confronted or when Christian film critics and pastors offer a thoughtful critique of the film, the response often seems to be, "Well, you're wrong. The movie made me feel great, and

I feel encouraged, even convicted to pray more. And who are you to speak judgmentally and negatively about other Christians and what God is trying to do through their work? God inspired me and changed my life through this movie. How dare you question that?"

Well, I dare question it. I think it's dangerous when we stop the questioning regarding our faith and our art. (It's equally dangerous when we only question and never come to any solid conclusions or ground our feet in good theology and relationship with the Creator). More importantly, it raises a larger question, one about the relationship between personal experience and sound theology:

If someone believes an experience to be good, and it inspires them to genuinely follow God more, does that make it true?

If I come to a personal conclusion that is ultimately good--at least in my eyes--does it really matter how I got there? Why criticize the process if the end result is beneficial? Perhaps the ends justify the means.

...

The response of "I liked it, so stop critiquing it" may be an indicator that our faith is placed in something less than the death-and-resurrection power found in Jesus and the reign of his kingdom values in our world.

•

I'm not familiar with Jon Ellis, but his passionate critique of the Kendrick brothers' oeuvre sums up much of what has troubled many of my fellow Christians about the Kendricks' work:

Incredibly bad aesthetics aside, the movies of the Kendrick brothers (and many other “Christian” filmmakers, for that matter) are dragging people into the pits of hell with their heretical “name it, claim it” depiction of Christianity. For example, their second movie, Facing the Giants, taught that the “good” of Romans 8:28 is defined by the standards of a wealthy, individualistic, and hedonistic West. Years ago, my wife and I watched it together, and during the locker room scene, the “What are you living for?” speech, I turned to her, shook my head sadly, and sighed, “the only way that this movie can come even close to redeeming itself is if the team goes out and loses.” Of course, the team won – with a kicker named David kicking the winning field goal to beat a team named the Giants. Come on.

Then, responding to urges from his readers to go see War Room and comment on it, he sees the movie and is overwhelmed by how much he has to say about its failures as a movie:

The storytelling, filmmaking, and “form” flaws of War Room are so numerous as to create a veritable piñata for critics; and, as a bonus, we critics don’t have to cover our eyes when we swing our rhetorical bats at it. To be honest, as I look over the notes I took while watching War Room, that rhetorical bat is starting to feel heavy and I’m starting to wonder if I’ve taken more than my fair share of swings at the War Room piñata. With that in mind, and with several pages of notes about the ubiquitous film score, bad acting, and a long and sundry list of storytelling faux pas remaining unpacked, it’s obvious that the Kendrick brothers blatantly violate the standards of storytelling and filmmaking. Failing in its form, War Room tells the audience that God doesn’t care about art that strives to honor Him through excellence in form.

Sadly, many Christians are ok with that. They, too, have bought into the lie that function in art washes away the sin of bad form.

•

Okay, now let's move on to what the movie looks like to people who have devoted themselves to discerning what is excellent, mediocre, and lamentable in the art of cinema.

Here's Scott Renshaw in Salt Lake's City Weekly, whose reviews I've often appreciated:

The faith-based drama War Room wallows an an infantile concept of prayer that turns God into a genie.

Then he elaborates at Letterboxd:

... [S]tructurally, the movie is a mess, building to so many different endings it really should’ve been called The Return of the King of Kings. And even more troubling is the mix of victim-blaming in an emotionally-abusive relationship and an infantile depiction of prayer that turns God into a genie who gives your husband food poisoning before he can cheat on you. All the Satan-rebuking speeches in the world can’t make a story uplifting when it subtly suggests that you can tell a real Christian by the way everything always works out exactly the way they pray for it.

And lo — the great Richard Brody in The New Yorker:

The societal divisions and exclusions that the movie perpetuates are, rather, those of class, of money. There are no poor people in “War Room,” with the exception of the off-screen character of Elizabeth’s sister and unemployed brother-in-law, who are seeking to borrow money for rent and a car payment (though even their poverty is presented as temporary and readily reparable). The entire movie takes place between comfort and luxury; economic success comes off as the great unifier.

Kendrick doesn’t preach the gospel of wealth; he also doesn’t suggest the trials of faith arising from the wearying struggles of unrelenting poverty. The religion of “War Room” is a religion without sacrifices—except for attitude.

Looking Closer: A New Blog Awakens

Hello, class!

Please find a seat, get out a piece of paper and a pen, and settle in. Welcome to the first day of a new school year.

That's what it feels like for me, anyway, as the curtain goes up on a new version of Looking Closer.

Some of you may be longtime readers. Some of you may be newcomers. Whoever you are, let me start off by making one thing clear: At Looking Closer, nobody needs to raise a hand in order to make a comment or ask a question. This class is a conversation. I'm looking for fellow explorers, not fans or followers.

That's why, as you've noticed, I've arranged our chairs in a circle.

"What are we studying?"

We're a fellowship. We quest to find and lift up all that is beautiful and true and imaginative in the world of art — in movies, music, literature, and more — and to practice discernment, call out mediocrity, and put behind us anything that threatens to waste our time.

We don't do this because art is an end in itself: There are far too many websites in the world that amount to little more than "I liked this movie!" and "Thumbs down for this!" Those are reactions.

We're planning on going farther than that. We're going to ruminate.

You know what that means, don't you?

We're going to chew on and draw nourishment from the substantial things. Our minds are going to dwell on whatever is true, whatever is honorable, whatever is just, whatever is pure, whatever is lovely, whatever is commendable, whatever is excellent or worthy of praise.

Art, deeply considered, teaches us to see more clearly, interpret more wisely, feel more deeply, love more expansively, and live more meaningful lives. That's what we're after.

And we'll practice fearlessness. There's always a temptation to stick with the entertainment that mirrors back to us what we like, what we agree with. Similarly, there's another temptation: To avoid the discomfort of art that presents ideas contrary to our own, that upsets us with the sights and sounds of the world's afflictions and ugliness.

We will resist those temptations.

We will make ourselves vulnerable, because it is only in vulnerability that we can open ourselves to the Truth — and the Truth wants to change us and reconcile us to one another.

We will allow ourselves to engage other artists' perspectives, as alarming as they might be, because that is an exercise in listening, taking an interest in, and loving our neighbors.

Thus, we'll be prepared to discover goodness in art from all over the world, and from any worldview.

In a world crowded with consumers who embrace whatever is advertised, and noisy with voices driven by condemnation and fear, I want a community that's more inclined to boldly go where no audience has gone before in the expectation that we will find beauty and truth in unexpected place. Creativity is a venture that involves faith — a collaboration with mystery — and any artist, whether they're aware of it or not, can unleash wild truth into the world.

So, as we climb mountains to breathtaking views and descend into dark places to uncover hidden treasure, we will look and listen — and then look and listen closer — willing to be inspired by even those artists who are most different from us.

Excuse me while I catch my breath. I'm getting carried away.

I'm not a voice of Authority telling you how it is. I'm not the Gandalf on this journey: I'm not here to lecture or declare things. I'm here to invite you to walk alongside me to experience and contemplate things.

I'm a tour guide. It's my job to point at things up and say "Check this out. Here are some of my thoughts about it. But what do you think?"

On those occasions when I do hold forth, consider it a contribution from a fellow explorer, not a sermon from a pulpit or a verdict from a judge. Since any response to a work of art is an act of faith — a tentative venture to find an expression for a mysterious undertaking — I've embraced this disclaimer from an Over the Rhine song as one of my mantras: "And like all true believers / I am truly skeptical of all that I have said." Consider that the "P.S." to anything I publish.

My reviews and lists? You can take them or leave them. They're just one traveler's experience, a treasure map that you may find rewarding. And you're invited to reply with your own reviews and lists. I'll be posting plenty of other opinions as well, in hopes of stirring up some discussion.

I also mean for Looking Closer's community to be an oasis from the vast territories of corrosive digital discourse. Keep reading, and I'll say more about how that works at Looking Closer.

But first — some of you may be wondering:

What qualifies me to be a tour guide through arts and culture?

Well, I'm learning as I go.

I do come from a family of teachers. My mother has a rare gift for — and a passion for — teaching small children; she loves that above all, and spent many years teaching preschool. My father spent many years teaching at the high school I attended, as did my uncle. Having grown up around educators, I've found teachers to be the most influential people in my life — either in the classroom or on the page.

I cherish the classroom experience. It was in the hopes of creating a space for classroom-like discussion of texts, images, and music that I introduced the first version of Looking Closer in the late 1990s. I was surprised by how many people showed up. Some came to tell me I was wrong about everything. Some were fearful Christians who told me I should stay far away from the corrupt, dangerous, and secular world of the arts. Others were not religious — and they told me that the arts were no place for a religious — and thus corrupt, judgmental, and self-righteous — beilever like me.

Nevertheless, I found a community of seekers — people of all kinds of faith who wanted to go searching for beauty and truth together, without dividing the world into "us" versus "them."

The fact is that I have found art from all over the world, and from all kinds of people, to be rewarding and inspiring to my faith.

And that happened, although in an unconventional way: As I worked a city government job to pay off student loans, I found my first teaching gigs as a writer — specifically, in a decade-long stand as a critic and/or columnist at Christianity Today. Then I became a monthly film blogger for Image. I wrote about film and interviewed filmmakers for Paste. And I wrote about film-related books for Books and Culture. During those years, I also started blogging at what became Looking Closer.

Those experiences led me to write a memoir about how art has been a guiding light in my life: Through a Screen Darkly. And although it never occurred to me that I was writing a textbook, the volume — published by Regal Books — Through a Screen Darkly took on a life of its own. It has become a resource on movies, creativity, cultural engagement, artistic discernment, and faith, taught in courses at a variety of colleges and universities internationally — from Seattle Pacific to Biola to King's College in New York. I'm amazed and grateful for that unlikely development.

And there are more stories coming. I may even try some of them out on you here at the new version of Looking Closer. (I haven't done that before.)

So when I write about my experiences with art, I speak as one in love with the creative process and with the conversation that surrounds it. Every movie I see, every book I read, every song I play on the car stereo, and every conversation with other explorers teaches me more. And then, when I lose myself in the act of making something new, that becomes a learning experience unlike any other.

I'd prefer to do this in-person.