Brooklyn (2015)

When I look at the eight films nominated for Best Picture at the Academy Awards, one title lunges at me like a mama grizzly attacking my cynical Oscar assumptions.

Sure, you've got the Brave and Important Movies About Important Social Justice Issues Starring Several White Celebrities (Spotlight and The Big Short). The first one was... pretty good; the other, just okay. You've got the obligatory nod to a Spielberg movie (Bridge of Spies) that was... pretty good. You've got the blockbuster full of famous names that almost everybody liked (The Martian) — and it was pretty good too. One has a scenario so distressing that it would have been nominated no matter who directed it (Room). Pretty good! You've got the Most Likely to Succeed, with its trifecta of Oscar-bait maneuvers: the one that brings back ideas that were executed more innovatively and meaningfully in past films that the Oscars passed by (The New World); that stars an actor who deserved the award at least once in past years (that guy from The Wolf of Wall Street); and that features cast members going to almost psychotic extremes to get attention. Aaaand you've got the wild card that shows Oscar's desire to seem punk rock (Mad Mad: Fury Road), but that stands little to no chance of actually winning. (It was awesome.)

And yet, there among the noisemakers and prestige pictures is a modest, quiet, good-natured film focused on women, immigrants, and loneliness. And it focuses on a protagonist who has not one but two honorable and admirable young suitors. There is no villain. There's nothing showy about it. The cast succeed through understatement. The conflict is not contrived. The style is not attention-seeking in its realism, nor is it gratingly stylized.

And yet, there among the noisemakers and prestige pictures is a modest, quiet, good-natured film focused on women, immigrants, and loneliness. And it focuses on a protagonist who has not one but two honorable and admirable young suitors. There is no villain. There's nothing showy about it. The cast succeed through understatement. The conflict is not contrived. The style is not attention-seeking in its realism, nor is it gratingly stylized.

The most common complaint I've heard about Brooklyn? "There's just not enough conflict in it to make it interesting." Actually, that has a lot to do with why I had no trouble suspending disbelief, why the human-scale tensions of the story took hold and made me care. It's the only film among the Best Picture nominees that actually moved me to genuine, non-compulsory tears. And it marks the graduation of lead actress Saoirse Ronan from the class of Quirky and Charming Young Actors to that rare class of Leading Ladies Who Seem Like Genuine Human Beings instead of future cosmetics models.

It's kind of hard to believe that Brooklyn exists. This premise doesn't exactly leap off the page as big-screen material: In 1952, Ellis Lacey, an Irish shopgirl dispirited with the options open to her for the future, seizes an opportunity to escape those discouraging templates and emigrates to America. There, she struggles to find her feet. Challenged and assisted by roommates, friends, a kind-hearted priest, and a lovestruck Italian suitor, she begins to find her way, only to find her progress complicated by troubles from the world she left behind. And yet the result is so patiently developed, so warm-hearted, so humane that — in spite of the fact that almost none of the clothes look lived-in, almost none of the cars look like they've ever driven through a puddle, almost none of the props look like they've been used before — the characters became unusually three-dimensional and compelling.

Is it a startling work of directorial mastery? I don't think so. Director John Crowley and screenwriter Nick Hornby have made something that feels something like a handsomely filmed Masterpiece Theater movie perfect as a date-night choice for people who love to read. (It is, in fact, an adaptation of a celebrated novel by Colm Tóibín.) But considering the competition — I think 2016's selections are a fairly mediocre (and alarmingly whitewashed) lot — I'm more than happy to see such an honest, heartfelt work getting attention. (And I'm in favor of anything in this toxic political climate that reminds us that America is a nation of immigrants.)

And as crowdpleasing love stories go, this one was surprisingly unpredictable. In almost every scene I felt myself bracing for conventional movie twists — especially when it came to the suspicious goodness of the young men in Ellis's orbit. I was pleasantly surprised every time.

I'm delighted to see Saoirse Ronan shine so brightly here. I feared she would take the Cate Blanchett route, and start focusing only on prestige pictures with roles that shout "SERIOUS ACTING." But the combination of Grand Budapest Hotel and Brooklyn have made me a fan of her subtle humor and her ability to steal a scene quietly instead of competitively. She serves her characters in a way that serves the whole picture. And she's learning to use more than just her amazing eyes in a performance, fulfilling the promise she showed in Atonement.

Also worthy of shout-outs: Emory Cohen, who gives the best Young Johnny Depp performance since, well, Young Johnny Depp himself appeared in What's Eating Gilbert Grape? Jim Broadbent as a gentle and generous priest (boy, did we need one of those this year). Domnhall Gleeson, in his one hundredth supporting performance in 2015 (or at least it seemed that way). And Julie Walters brings a bit of reckless humor to the proceedings as a smirking landlady.

There are moments when the film's respect for the promise of America gets a little gauzy and shiny. But there is real human hurt in this story of hard decisions. Most people need stories about how important it is to love you neighbor as yourself. But some of us also need stories about the second half of that equation — that to invest oneself only in duty, seeking to fulfill only the expectations of others, is to live dishonestly, and to disrespect the will and the gifts one has been given for a purpose.

Ronan's radiant Ellis is a great character. I didn't realize, because of the pronunciation of her name, the significance of that name. But when I saw it spelled out at the end of the film, I had to smile. Of course. Perfect. What a great New York story.

In retrospect: the most amazing film of 2012

In 2012, a short film that didn't play on big screens was overlooked for awards and was treated as a joke by a few snarky Facebook users. But in retrospect we can now see that it was not only relevant, it was downright prophetic.

[Source.]

Meanwhile...

The Revenant (2015)

The time has come in my survey of this year's lineup for Best Picture at the Oscars for me to turn my attention to the movie that has been judged the front-runner.

I'm tempted to pass over it, because its favored status has had the effect of dividing critics into Those Who Love It and Those Who Disliked It Before But Who Really Hate It Now Because the Academy Will Probably Bestow Upon It an Honor It Doesn't Deserve.

If you've read my Oscar-season blog posts before, then you know that I don't think the Oscars have much, if any, credibility on the matter of great art. Commerce corrupts the whole affair so much that it is reduced to a popularity contest. Sure, it's a contest that can, sometimes, bring some attention to a few worthwhile productions. I like the Oscars primarily for how they remind us that cinema is collaborative, bringing the efforts of countless artists together, and for how this showbiz circus fills an evening with speeches made out of gratitude — but that's about as far as my affection goes.

I say that as preface to this: my overdue review of The Revenant. My impressions have nothing to do with its Oscar chances. This is just the inevitable working out, in writing, of the frustrations I have felt about the film since I first saw it — long before it emerged as the Oscar favorite.

•

For my friends and colleagues who love Alejandro G. Iñárritu's The Revenant — that epic story of suffering, survival, and revenge based (well, just barely) on the story of frontiersman and trapper Hugh Glass — I can go this far in agreeing with them:

The film leads us through phenomenal landscapes and weather, and depicts struggles with animals, elements, and sprawling battlefield violence that are as convincing as any ever filmed. I admire its technical achievement. And I admire its focus on showing rather than telling.

Several of those same friends and colleagues treat this as a film to be appreciated for the art of its aesthetic achievement rather than the art of its storytelling. And I wish I could agree — it would be easier, and I wouldn't feel conflicted about parting ways with moviegoers I respect.

I get it: Cinema is not to be critiqued the way we critique novels. Cinema is more than just a way to illustrate a story. I actually agree with those who say that, when it comes to cinema, imagery is more important than story — just as I agree that sound and melody are more important to song than lyrics. Motion pictures: Just as you can take away lyrics and still have a piece of music, you can take away narrative and still have a movie.

Some of my favorite films — from Vertov's Man with a Movie Camera to Tarkovsky's Zerkalo to Wenders's Wings of Desire to Kieslowski's Three Colors: Blue to Malick's The Tree of Life — are more interested in visual poetry than sequences of events. And The Revenant has the craftsmen and visionaries it needs to become one of those great work of imagery, of performance, of poetic association.

But that's not the movie we have. The movie we have insists upon its narrative as central, and the script by Iñárritu and horror filmmaker Mark L. Smith (Vacancy) paces his production to deliver episodic action. If The Revenant's narrative had been as substantial and intriguing as the visual spectacle, it might have become one of the most enthralling big-screen stories I've ever seen. Epic stories of distinction, nuanced character development, suspense, and insight have unfolded in just such a historical context as this one.

But for all of the glory of the context, for all of the extravagant efforts of the cast, this narrative strikes me as juvenile, unimaginative, eager to seem profound, but constantly failing to cultivate any interesting ideas.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qtZat1Ljq4M

In case you haven't yet heard the premise, here goes: In the early 1800s, a company of trappers endure rough conditions in a desperate flight from Native Americans through a region that will, in time, become the Dakotas. Trapper Hugh Glass (Leonardo DiCaprio, seemingly ready to die for an Oscar) and his native son Hawk (Forrest Goodluck, playing someone in a forest without any good luck) are persecuted by one of their fellow travelers, a base and fuming fellow called Fitzgerald (Tom Hardy at his hardiest). We suspect that, as soon as he gets his chance, Fitzgerald will do something horrible. His chance comes all too conveniently when Glass, out of the blue, gets shredded to within a half-inch of his life by a wild animal. (You've probably heard about that scene. Believe what you've heard. It will give you nightmares.) The attack gives Fitzgerald his opportunity to be really evil. And the course of the film's next two hours are basically determined: Glass must survive in order to catch up with Fitzgerald and kill him. Along the way, he will endure unbelievable bodily harm. He will have run-ins with Native Americans. He will have close calls with reprehensible white men. And he will have visions of a supernatural nature.

And when his climactic showdown arrives, has the narrative gained layers of meaning and significance? I don't think so. The villain insults the masculinity of Glass's son, and the final round of growling and grappling and bloodletting ensues. The whole film feels like a reel of NFL egos, injuries, brawls, and trash-talking. It's a movie of constant unnecessary roughness.

For this viewer, every event in the story — from battles with wild animals, to battles with native defenders of the homeland, to elaborate feats of wilderness survival — seemed staged more to give Iñárritu a chance to show off technical virtuosity, to beat his own chest the way these characters beat their own, rather than to enrich the story or develop any kind of suggestive qualities.

But let's put the story aside, if we can, and focus on this much celebrated imagery...

•

Many have lauded the film's immersive aesthetic — how it brings us spectacularly close to the action, and gives us a palpable sense of the elements. There is blood splatter on the camera lens! The bear even breathes on the camera, fogging it! It's true. These things happen. They happen so brashly and frequently that they constantly draw my attention the camera itself, and to the question "How did they do that?" They keep me thinking about the director himself. And when they do, they diminish my suspension of disbelief.

Thus, The Revenant is not immersive, although it uses tools that can be effective in immersing me. It's so intent upon immersing us that its sheer force in doing so is what dominates the experience. It's immersive-ish.

Perhaps you will find yourself reminded of great directors with distinct styles: Terrence Malick, for example — an artist who cultivated a personal and distinct aesthetic while collaborating with a variety of cinematographers, especially Emmanuel Lubezki.

And you'd be right in seeing a resemblance, for, in fact, this is Emmanuel Lubezki, filming what often appears to be a continuation of his unbounded, sweeping cinematography for The New World.

Yet, this time around, Lubezki's camera is not intent on characters and their interior lives, or even on characters at all. These characters don't change over time: they are constant, pressing on with their one defining characteristics. The hero exists to be wronged, injured, broken, and struggling to overcome it all so he can settle the score. The villain exists to do him wrong. The hero's son exists to suffer weakly so that the movie can kindle our desire for violent justice.

And I wished, for 156 frustrating minutes, that I could leave this predictable and inevitable clash of brutes — with their playground-bully insults, their fighting and more fighting, and the eventual killings and horrors and striving for revenge — and just wander through the glorious environments in which it was all taking place. Lubezki's wide-eyed cameras seem to want to drift away too. In Malick's movies, the camera can do that, can drift off and, thanks to Malick's editing genius, find threads of poetic significance within anything they approach. Juxtapositions of images suggest that this is a way of talking about that. Creation "pours forth speech." But here the tyranny of this story for boys who think masculinity is about physical endurance and muscle and weapons keeps pulling Lubezki back to what Innaritu finds important: the violence of men and the violence of nature.

Similarly, devotees of Andrey Tarkovsky will sense a certain familiarity in a variety of sequences. More than one film critic referenced Tarkovsky in describing the film's look. Then this video came along to silence any doubters.

https://vimeo.com/153979733

Imitation is the sincerest form of flattery. But again, here is imitation that seems to seek greatness by association. It's an "I can do that too" spirit without demonstrating an understanding of how these shots make meaning. These Tarkovsky images are from different films in which the camera's life suited the story it told — and one of them (Zerkalo) represents a surreal soup of memory and dreams.

So, The Revenant ... it has the appearance of great films, but it does not demonstrate an understanding of what made those films substantive. It's not as rich as Malick, but it is, well, Malick-ish. It isn't the equivalent of Tarkovsky, but it is Tarkovsky-ish.

What the movie lacks that these masters offer is a narrative worthy of the aesthetic. The Revenant does not investigate anything beyond its simple survival-for-the-sake-of-revenge narrative substantially enough to arrive at a conclusion that resonates. Not for this viewer, anyway. Some have argued that it nobly attributes to Native American tribes the dignity and humanity they deserve. And they do have moments of basic nobility. But the fact is that they remain marginal to the narrative — a pursuing force, bloodthirsty as orcs, or a parade of regal and wounded dignity. None of them become characters. And their sufferings and deaths are paced so as to provide new fuel for the central white hero's vengeful resolve.

So the film is not really committed to its gestures of respect. It's not compassionate — it's compassion-ish.

[ For a thought-provoking perspective on The Revenant's narrative,

read Melissa Tamminga's review at Letterboxd. ]

Some have stepped up to argue that the film has a profound spiritual vision. Look at how Glass's wife appears as a spirit to minister to him! (Yes, she levitates, like Jessica Chastain in The Tree of Life, or like a certain spectral figure in Tarkovsky's Zerkalo.) Look at that ruined chapel with its painting of a crucified Christ! Sure, these scenes exist. They suggest that the film wants us to accept that this is a world in which sacred mysteries are at work. But these are fleeting glimpses of mystery, images that the film quickly leaves behind in order to zoom in on spectacularly choreographed battles and struggles. It feels like the filmmakers have seen movies that tap into a sense of mystical Christianity, but aren't sure how to do it themselves.

For me, this is a central question to pose to any movie to understand what it really is: What does this movie love? That is to say, where does it focus its energy? The Revenant always comes back to its central character's physical fight with enemies and the elements. That is what it is most interested in. For all of its feints in the direction of conscience and spiritual inquiry, almost every sequence is primarily about staging visceral violence to the point that it becomes exhausting. It's not conscientious. It's conscientious-ish.

I wish I could write a different review. I wish I could take seriously the film's few moments in which characters show mercy, or in which a sense of divine intervention is at work. But those moments feel like token gestures. While The Revenant has the scope and ambition of Apocalypse Now, it has none of the poetry.

And, as Michael Caine once said to me, "If you're sitting there thinking to yourself 'Michael Caine is giving a great performance' then I have failed." I never stopped thinking about the actors, the cinematographer, or the director. In their constantly showy maneuvers — and that includes Leonardo DiCaprio, who strives so fiercely during his every moment onscreen — they kept spoiling my desire to suspend my disbelief and get caught up in the film itself.

•

Is it just Oscar-ish?

No. It's right up Oscar's alley. Oscar loves audacity. It loves the great directorial innovations of the past when they are finally applied to something that makes enough compromises to become crowdpleasing and popular. As far as that goes, The Revenant is an Oscar movie all the way. This is exactly what the Academy loves to reward: imitations of greatness, celebrated by audiences who are finally accepting as mainstream what was visionary a decade ago.

Just as Ridley Scott's Gladiator made much of a stolen Terrence Malick-ism (a man walking through a field with his hand outstretched to the long grasses) and applied it to an elementary revenge epic, giving it that air of masculine spirituality, and won the Oscar that Malick has never won, so Iñárritu's Revenant will, most likely, do the same.

Let's get it over with.

Room (2015)

"I've heard it's good, but there's no way I'm going to see that movie."

I've heard that on several different occasions from several different people — and all of them were mothers.

And who cam blame them? Room is a movie about a woman living out a nightmare.

For the record, I am a male of the species, and I am not a parent. And frankly, my heart didn't leap at the prospect of seeing a film about a woman who is imprisoned for seven years in a toolshed, and who gives birth to and raises a boy for five of those years.

But as the movie Short Term 12 made me want to follow actress Brie Larson anywhere, the raves for her performance in Room sealed the deal: I was going to sit through this movie no matter how difficult. And I am so glad I did — not only because Larson is magnificent, but also because the boy playing her 5-year-old, Jacob Tremblay, is quite a discovery.

Tremblay gives one of those child-actor performances that comes along once every few years, in which the child seems oblivious to the camera, so immersed in the character, the scenario, and the relationships that it almost disrupts your suspension of disbelief. (Think of Victoire Thivisol in Ponette, Anna Paquin in The Piano, Max Records in Where the Wild Things Are, or Quvenzhané Wallis in Beasts of the Southern Wild.)

Now, you might still be thinking "I don't want to watch a mother and child suffer like this." And that's a reasonable objection. You don't have to.

But what captivated me about the first hour of this film is the tenderness, the imagination, and the radiant love at work in the mother-son intimacy — how, as in Life is Beautiful, a parent must sustain a child's hope and capacity for joy by translating their circumstances into a sort of schoolroom. Their tiny cell — which they call "Room" — does begin to seem rather spacious as we learn how Ma is making the most of the available space, their necessary furniture, the wardrobe in which Jack sleeps, and the tiny skylight high on the ceiling where the appearance of a leaf becomes a momentously "teachable moment."

I don't want to give any spoilers, but I do want to offer some reassurances to worried moviegoers: You may have heard that the main character is a rape victim, and that's true — but there are no onscreen rape scenes. You may have determined to avoid scenes of graphic abuse, but the appearances of the villain are few and surprisingly non-violent. I'd encourage moviegoers to see Room in spite of — and, in fact, because of — its intense emotional journey. The rewards are well worth what the film demands of its audience. Director Lenny Abrahamson and writer Emma Donoghue (adapting her book) show remarkable, admirable restraint in their depiction of this nightmare.

Unfortunately, the film's second half feels a bit unsure about what to do with its time. What could have become a study of lives lived beyond "Room" — lives similarly bound, limited, and confined by other kinds of walls — takes a rather meandering path instead. It's an observant, patient, but not particularly compelling study of the challenges faced by trauma victims after the worst of their sufferings.

Again, I'm trying to avoid spoilers in this review, so I'll leave it to you to decide if the second part of the movie maintains stylistic continuity and storytelling substance. I found Abrahamson's directorial imagination to become less and less interesting the larger his canvas became, the more he "zoomed out" from that initial closed space. He delivers a few inventive and Malick-esque flourishes within "Room," but the film's point-of-view feels too flexible and inconsistent to me, so that I lose intimacy with the characters and my sense of a strong central thread in the later chapters.

And yet... and yet... Room has strong staying power, primarily because of the intensity of its premise. I did not imagine that I would relate to Ma and Jack during their time within the toolshed, or that I would feel such emotional resonance with the challenges that come to them later.

For the record, I did not grow up locked in a toolshed, and my mother was not a sex slave. My father was not abusive. My parents were creative, resourceful, and a lifelong model of faithfulness and generosity. My childhood seems too good to be true when compared to this horror story. And that in itself makes Room seem horrifying to me in a different way than it would to a victim of abuse.

And yet there was something deeply, hurtfully familiar about Room. And I suspect that you will think so too. We all can name a "Room" that we've experienced: a space that was too small, a context that was too oppressive or confining, a scenario that limited our freedoms or kept us from access to the truth.

And yet there was something deeply, hurtfully familiar about Room. And I suspect that you will think so too. We all can name a "Room" that we've experienced: a space that was too small, a context that was too oppressive or confining, a scenario that limited our freedoms or kept us from access to the truth.

For me, in childhood, my "Room" was the way that a fundamentalist evangelical culture taught me that "The World" beyond our community of the faithful was too corrupt, dangerous, and worthless for us to engage. We were safe in our religious room, our religious vocabulary, our certainties, our insularity. I'm grateful that I received the grace of good teachers who introduced me to great art and literature, which served as windows on "The World," and which also served as a mirror, revealing that there was just as much sin and corruption and trouble right there in our "Room." I'm grateful for the wisdom of theologians who showed me that the Scriptures are full of exhortations to engage, celebrate, and love "The World Outside" with courage and humility. But breaking out of the box of conservative-evangelical separatism and escaping into the kind of world that God meant for us to explore and inherit — that was a costly, painful process, and the wounds of that experience will always be with me.

In adulthood, I have found myself trapped in another kinds of "Rooms" where my needs have been disregarded, my creativity stifled, where a well-intentioned endeavor to "think outside the box" inspired jealousy and insecurity in others who effectively ensured I would not get that chance again.

During my graduate studies in writing creative nonfiction, I came to realize that most (if not all) of my memoir-focused essays were ultimately about escape — escape from limited perspectives, insufficient vocabularies, exploitative relationships, functions that serve others' purposes but disconnect me from my calling.

If you were to write your own personal Room stories, what would the Rooms be? Are you still trapped in them? Have you convinced yourself that it's better there, where you know what to expect? Do you find yourself free sometimes, but then drawn back in at other times? I suspect that you can name individuals, communities, and other forces that have locked you up, denied you access to the truth, and sought to exploit you for their own purposes.

This is the gift that Room gives us: a narrative and a vocabulary that lends itself readily to so many of our day-to-day challenges. Sure, it's about a nightmare scenario, and I'm inclined to think that objections from those who refuse to see it are evidence that they know this emotional territory already, or else they have a healthy aversion to seeing any child deprived of freedom, family, friends, and open skies. God bless them! But I also believe that, while Room is a difficult and demanding experience, it will be useful to moviegoers in their discussions about their own challenges. It will kindle our our attention to and compassion for our neighbors, and increase our desire for the freedom to become what we were meant to be.

•

[If you appreciate this review, you can say a little "thank you" by contributing a little something to the support of this website. It's a labor of love, but it costs me. This review was made possible by the generous support of Looking Closer Specialists. You can become one. Here's how.]

A Martian, Mad Max, and a Mortgage Loan walk into a bar...

Mad Max: Fury Road. Spotlight. Room. The Revenant. Brooklyn. Bridge of Spies. The Martian. The Big Short.

At The Kindlings Muse, a live podcast event at Hales Brewery and Pub, I talked with Seattle Pacific University's own Dr. Jeff Keuss, Jennie Spohr, and Anna Miller about the eight films nominated for White Picture.. I mean Best Picture.

We talked about which films moved us, which films didn't, which are most artful, and which are most meaningful.

And now you can listen to all of the laughs (there were laughs) and tears (okay, there weren't tears, not that I noticed). The podcast is up!

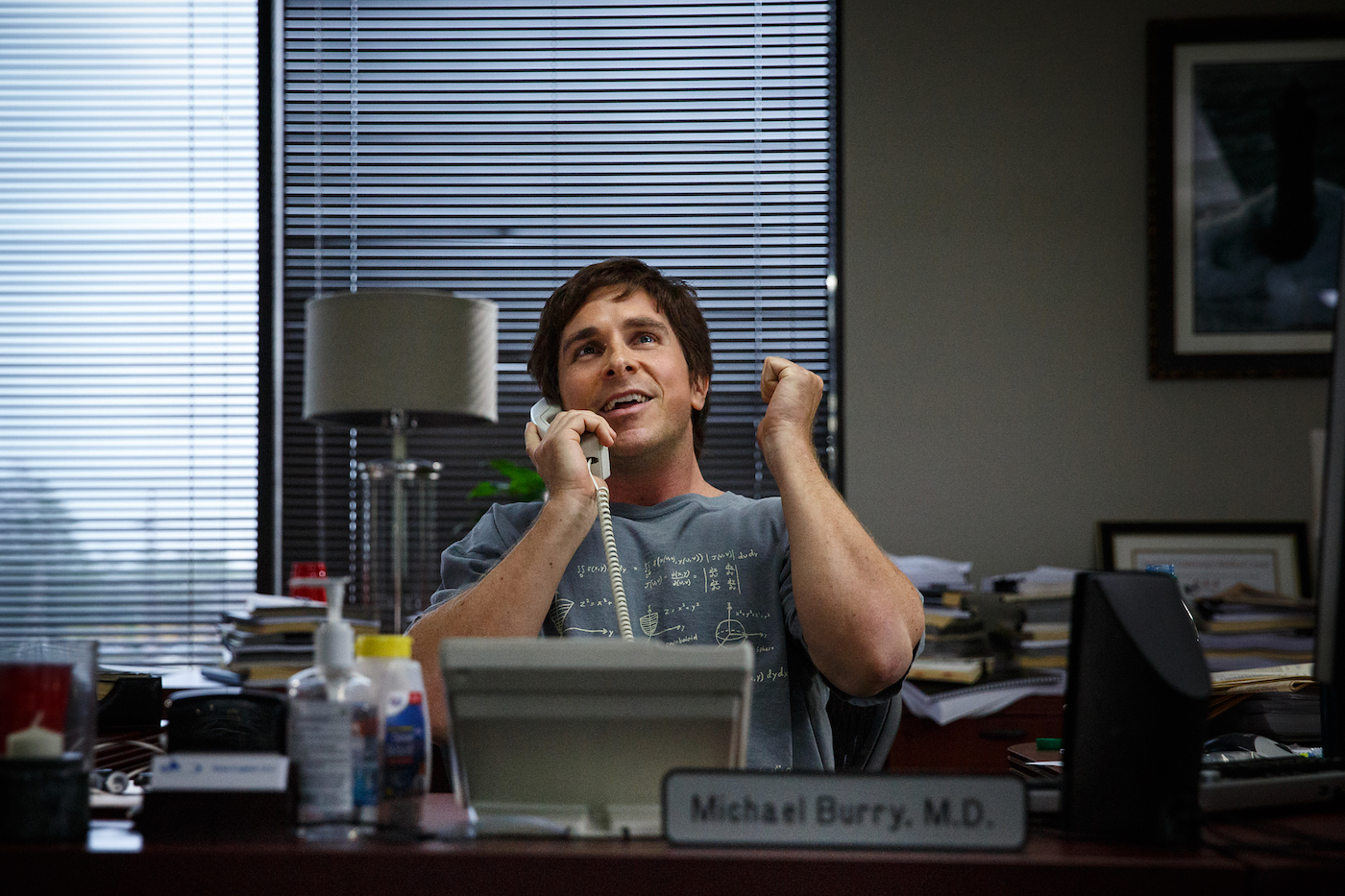

The Big Short (2015)

[This review is made possible by the Looking Closer Specialists who support this blog. I'm grateful for you, Specs.]

•

Adam McKay, director of Anchorman and Step Brothers, has his first Best-Picture-nominated film at the 2016 Oscars.

If you haven't yet seen it or read about it, that may be because the subject matter doesn't appeal to you. It's a high-spirited, humorous investigation of a horrible chapter in American history: the chapter in which our democracy was pretty much overthrown by liars and cheaters who robbed us of 99% of America's wealth.

Based on Michael Lewis's book of the same title — a detailed autopsy of the American economy, devoid of the movie's satirical flourishes — the film traces the recent financial crisis that resulted when the markets collapsed due to rampant greed and an epidemic of ignorance. It stars Christian Bale, Steve Carell, Ryan Gosling, Brad Pitt, and about a dozen other bromancing cool kids.

And yet, while it's nominated for Best Picture, Best Director, Best Supporting Actor for Bale, and Best Adapted Screenplay, I found it as to be as frustrating as it is engaging. That's not because it does anything badly — the editing is fast and clever, the script expertly weaves a tapestry of plot lines, and the actors invest in their characters to strike a wide range of notes from whistle-blowing sincerity a la Michael Mann's The Insider to the absurdist comedy of Anchorman. It's just that it does too many things well that feel conflicting and incongruous. For every scene well-written and well-acted (and there are many), there are interruptions, segues, and flourishes that feel showy, snarky, and smug.

And ultimately, the story that it tells does not go far enough.

Here's what I hear this movie saying about itself:

"Americans need to understand these things: That their government is not running the show. That the people have been, are being, and will continue to be exploited — robbed of the money, the homes, the comforts, the security, and their children's futures — all that they've earned through honest hard work. That the thieves are above the law, untouchable, throwing wild parties with their money, and devising ways to take more besides from them and their children. That the middle class is tricked into thinking that this is all somehow the fault of immigrants and the poor.

"But these things are Complicated. And middle-class Americans don't like Complicated. They'd rather be slaves than have to do the work of thinking things through. They'd rather be exploited, mocked, and ruined than have to pay attention, learn a new language, and do what's necessary to redeem the system from within and hold criminals responsible. It's easier to suffer and complain and channel the energy of hurt into supporting some promise-making politician than it is to learn how we let this mess develop in the first place, and then get busy striving for change.

"So let's make a movie that gets people's attention, wakes them up, and teaches them what they need to know!

"But how?

"Well, what wakes up middle-class Americans and gets their attention?

"Celebrities.

"And not just any celebrities — the cool kids. Gosling. Bale. Pitt. A lineup of theWorld's Sexiest Man — actors who will attract female viewers who want them and male viewers who want to be them — and let's have them explain the tough stuff. We'll give it all the slickness of a great heist movie. We'll make it play like Ocean's 14. (Can we get Brad Pitt to eat and drink a lot onscreen? That'll work as a subliminal link to the whole Ocean's series.)

"And then when things get really complicated, we'll bring in Margot Robbie and Selena Gomez to break the fourth wall and explain things, because everybody will pay attention to them. This will be an obvious joke, and they'll laugh, sensing the satire in it.

"But that's ironic, right? Because the fact is that most moviegoers have shown up precisely because we've loaded this things with actors they already like. They're not here because they want to learn about sub-prime mortgage loans. They could have read books about that, read articles about that, or learned about that any number of ways. They're here for the famous people.

"So that's how we'll trick them into actually learning something."

That's what I heard the movie saying. That was its attitude.

And here's what I heard myself saying as I drove home from the movie:

I understand the good intentions of this movie. I can even admire a few of the performances.

And I appreciate a good satire. I count Dr. Strangelove, Waiting for Guffman, The Player, and many others among my favorites.

But this one feels condescending, uneven, un-cinematic, and cynical.

Condescending: Even though I agree with the movie's presumption that the majority of Americans really would rather read about celebrity gossip than learn how they are being exploited, I don't think that insulting the audience is the proper mode for challenging them. "Here's Margot Robbie in a bubble bath to explain this to you. LOL."

Uneven: If this had gone hard into satire, instead of shifting into that mode whenever things get "complicated," it could have been a real circus. But even though I laughed at some of the film's satirical flourishes, I found that the film's more sincere stretches — particularly the stories of Mark Baum (Steve Carell) and Ben Rickert (Brad Pitt) — feel like they're from a different film, a drama that might have been more substantial. So, while Carrell invests heavily in a drama of conscience, it's not what it could have been if the rest of the movie had lived in that world and not played to those with fleeting attention spans.

Further complicating matters is the smugness that radiates from this movie's star-system cast: I'm not blaming the actors individually, but I think that the all-star lineup does more to push this film into the realm of fantasy — like the Ocean's films — than it does to persuade us of the urgent reality that Americans do, yes, need to understand. Only occasionally did I feel myself drawn into these characters' dramas; most of the time, I was thinking about the actors and their performances which is, right there, a sign that something isn't working (at least for me).

Un-cinematic: Sure, it's slick, flashy, and entertaining in its rhythms. It's a blast to watch our favorite Hollywood kings play weird and wacky characters.

But I don't come away with a single memorable image, or one that is more than the sum of its parts. This is a movie in which cameras point and shoot people as they talk. No interpretation or participation necessary.

Cynical: Yes, I get that Margot Robbie was in The Wolf of Wall Street. But The Wolf of Wall Street was a film so fueled with anger that its satire was consistently ferocious: a funhouse mirror that punished its subjects by revealing their black hearts, and that honored as noble those who labor (however wearily) to resist. It was a jealousy-killing film: Who would want to be the "successful" men of that movie? The luxuries, glamour, and trophies were shown to be inseparable from the evils that made men pursue and possess them. It went to extremes to comfort the afflicted and afflict the comfortable. Entertainment was not its main mode. So, sure, I appreciate The Big Short's nod in Scorsese's direction. But it's not on the same level of artistry. I've seen The Wolf of Wall Street, and Big Short... you are no Wolf of Wall Street.

Did I learn some details about the housing market's collapse? Yes.

But you know what else I learned? That there's nothing we can do. Nothing. Selfish bankers collapsed the world economy; the self-interest of those who might have prevented the collapse blinded them to the pending disaster; and the government effectively pardoned the whole crooked conspiracy because, well... that's who owns them.

So while I came away with a very familiar sense of disgust for the wealthy criminals who run America in the name of Sacred Capitalism — and that's a fine thing for a work of art to inspire: a contempt for evil — I also came away with a sense of apathy and despair about a system that's so rigged every effort to break free only benefits the Enemy more. Satire is not duty-bound to present a solution, but its very truth-telling should feel like something of a victory in itself — that giddy buzz of have set truth off the leash to do its work in the world. Perhaps you get that sense from this, but at first viewing I do not. I feel only bitter resignation.

And yet, here's the thing: I don't really believe that there's nothing we can do. Despair and cynicism will keep me from striving to effect change, and so this movie may actually compound the problem by sending us away not much more than entertained. I want the film that makes me feel driven to do something, even if that just means I should seek meaning in more than money, and learn from the way history is already damning heartless hedonists.

When it's over, the slick style, the parade of coolness, and the smug cleverness all give me a sneaking suspicion that somehow this movie will end up putting more money in corporate pockets while the audience goes home feeling good about having seen a Serious Film About Something Important, and then makes plans to go see either Spotlight or Star Wars the next day.

•

But... having said all of that... I remind you that these are first impressions. I feel it's only fair to give some space for contrary opinions on this one, as a good number of critics and moviegoers I respect came away convinced they'd seen a great satire.

Listen to the great Filmspotting debate between Josh Larsen (whose experience was similar to mine) and Adam Kempanaar (who thought this the best movie of the year).

Listen to Glenn Kenny at RogerEbert.com who writes:

I started off feeling skeptical about this movie: the hairstyles and clothes of the main characters were more ‘90s music-video than early 2000s, and the sometimes-color-desaturated flashbacks to some characters’ back stories were a little on the drearily commonplace side. But the narrative momentum, combined with the profane wit of much of the dialogue, and the committed acting going on beneath the hairpieces, all did their job. ... You are free to disagree. But this is a movie that uses both cinema art and irrefutable facts to make its case. It’s strong stuff.

And my good friend John Barber, one of the Looking Closer Specialists, gives us a great example of how art strikes us differently because of who we are, the roads we've walked, the burdens and joys we've known. He writes this...

[SPOILERS AHEAD]

First, I loved it a whole lot.

Second, I completely understand why some people didn't (take a listen to the episode of Filmspotting in which Adam and Josh almost come to blows over this movie for more evidence).

I read Jeffrey's review and totally get it. I just don't agree. Rather than being condescending, I found it exhilarating. There was a joyousness in the storytelling that I found lacking in the obvious parallel film of the year, Spotlight (a movie that I liked and appreciated, but never really captured me). I adored the Robbie, Bourdain, Gomez, etc. interstitials. Maybe I need to be condescended to, but I thought they were the perfect outworking of the film's brashness

I really didn't want to see The Big Short. It's just that I decided that I wanted to see all of the Best Picture noms, so I made time for it. I had no interest in this one, and it's possible that my affection for it possibly stems from having low expectations.

My favorite line in the whole film comes from Brad Pitt's character, near the end, when his young friends asked him why he helped them and he says (this is from memory, so forgive me if it's off), "You wanted to be rich. Now you're rich." The struggle that some of the main characters go through (Bale's character is an exception, which I'll get to in a moment) when they realize that as they expose the corruption of the system, they still stand to profit immensely, is fascinating to me. And Pitt's line came back to me at the end as a sort of restating of Mark 8:36, "For what does it profit a man to gain the whole world and forfeit his soul?" As Carell's character sits on his patio and realizes that his moral high ground is gone, and he has no choice but to sell, I saw a man crumble under his own false sense of morality.

Now, Bale. This one is personal for me, so I understand if this is way off base. But the fact is that his character reminded me so much of my oldest son that it was a bit scary. My son, Sam has Asperger's Syndrome. I have no idea if Dr. Michael Burry has the same thing, but I felt the echoes if it all over him. The intellectual disconnect between Burry and his partner is one that I experience daily. Burry's incredulity at the idea that no one would support him was so spot on that I can't hardly describe it. I can see why many might think Bale's performance was over the top, but I found it spectacular.

Bottom line: The Big Short was, for me, that anomalous film that takes a situation that could have been so incredibly monotonous and it makes something joyful out of it. Whether I actually understand the financial crisis or I just think I do, the effect is the same. I came home wanting to tell everyone around me about this movie — AND IT'S A MOVIE ABOUT DEFAULT CREDIT SWAPS.

I only have eyes for Mad Max: Fury Road and George Miller this award season, but if this one pulled it out, I'd be happy. And as Adam Kempanaar said on Filmspotting, "All Hail Adam McKay!"

Terrence Malick's Zoolander

Thanks to my friend Damian Alryn for bringing this momentous cinematic event to my attention.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0J4DcJE1GtU

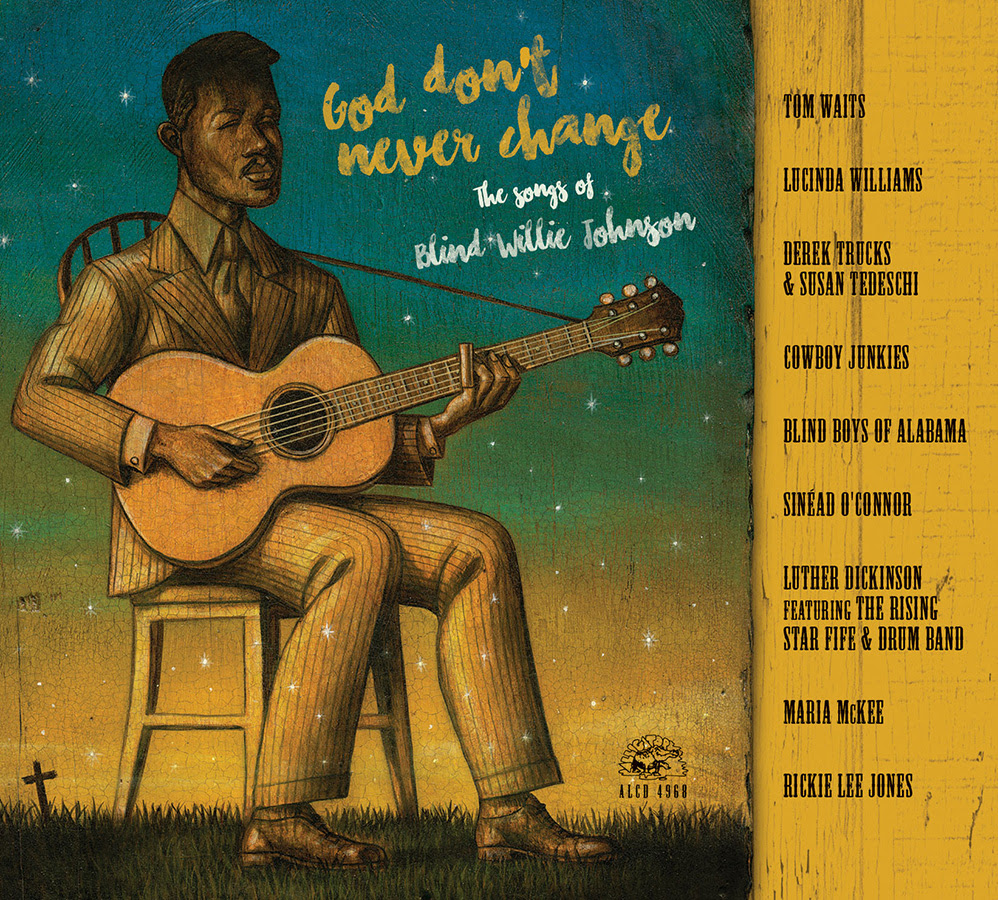

Tom Waits, Lucinda Williams, Maria McKee cover Blind Willie Johnson

Well, this is cool! Howl & Echoes has determined my soundtrack for today:

A new album paying tribute to Blind Willie Johnson is about to be released, including covers of his blues tracks by Tom Waits, Sinead O’Connor, Lucinda Williams and more.

That "more" happens to include Cowboy Junkies, the Blind Boys of Alabama, Maria McKee, Rickie Lee Jones and Luther Dickinson. My kind of party.

Zoolander 2 (2016)

Yes, this is my review of Zoolander 2. Bear with me.

This week, Kanye West invited fans to Madison Square Garden for an over-the-top party celebrating his new album, The Life of Pablo, and launch "Yeezy Season 3," his new wave of fashion. There, he teased the over-dressed and adoring crowd with tracks — not live performances, just tracks — while the spotlight fell on a despondent fashion show populated by bored models who had been directed to hold their poses for the duration. Somewhere in the crowd, Kim Kardashian West, dressed in so much feathery whiteness that even Bjork must have been impressed, moved about like some kind of intergalactic queen, or like a supporting character from a deleted scene of The Fifth Element.

After that, with his fans clamoring to get the album for themselves, West proceeded to delay the record's actual release so he could revise the music. With his anxious fans giving him all the attention he could dream of, he began tweeting out a stream of boasts and claims about himself, comparing himself to the Apostle Paul, boasting about how he's rich enough to buy his family houses and furs and anything they want, and then painting himself as a charitable servant of humankind. Then he referred to himself in the third person, saying, “He is the greatest living artist and greatest artist of all time." By contrast, even Donald Trump's ego seemed suddenly modest. Nobody seemed concerned about the fact that West had, earlier this week, pronounced Bill Cosby innocent — or, rather, "INNOCENT!!!!!!!" — of the many sex-crime accusations made against him.

While all of this unfolded, Zoolander 2 opened.

Zoolander 2 is a sequel to Ben Stiller's 15-year-old satire that gave the world a grand occasion to laugh at the excesses, the narcissism, and the inanity of that pop culture place where fashion trends and commercial music intersect. The original film enthusiastically lampooned pop culture's lavishly dressed posers as mentally deficient egomaniacs whose charitable acts are to establish "centers for kids who can't read good" even though they wouldn't be caught dead trying (and failing) to read on their own. Focusing on two supermodel enemies turned allies, Derek Zoolander (Stiller) and Hansel (Owen Wilson), it was like a fashion version of Dumb and Dumber, but crafted by far more intelligent filmmakers. Just as Anchorman needed only to slightly exaggerate the reality of egomaniacal-anchorman-as-celebrity culture in order to make us recognize this present Idiocracy, Zoolander was funny because it was true.

What's troubling is that the original seems tame now.

The realities of pop culture hero-worship and fashion-world indulgence have become so much more extreme that they've become almost impossible to lampoon. For any new Zoolander movie to have teeth, it would have to send up not only the models, the designers, and the fashion shows themselves, but also what goes on behind the scenes: the exploitation, the crime, the greed, and the materialistic and covetous public who worship these egomaniacal (and naked) emperors.

Instead, Zoolander 2 seems to have been committee-designed for fan service. It only looks backward, celebrating the risks it took last time, and then hitting those same buttons faster and harder. Zoolander 2 feels Zoo-longer, as if it comes from the same factory that pumped out a bloated, disappointing Anchorman 2. There are too many plotlines. There are too many characters. There are too many sequel clichés.

And there are way, way, way too many cameos. The closing credits name-check so many celebrities and famous fashionistas that I think I only recognized half of them during the movie. Some, like Willie Nelson and Neil Degrasse Tyson, don't convince me that the filmmakers asked them to be in the movie at all; rather, it seems like this must have been a case where the committee said "Who's cool? Let's get 'em!", or else certain celebs applied enough pressure to be promised a spot in a sequel to their favorite comedy.

It's kind of amazing that so many talented imaginations could not come up with something more substantial than this in the 15 years since the original.

As Owen Wilson's Hansel says, "Let's talk about what worked." What worked? Just enough that I can say I'm glad I saw it, but not enough that I recommend anybody pay the full ticket price.

For all of the rehashes, in-jokes, and pointless guest appearances, Zoolander 2 gets something right every few minutes — just enough to stay entertaining. As with Anchorman 2, the strongest stuff shows up in scenes that look like they were achieved through a dozen improvised takes. (I look forward to the outtakes.) I laughed. A lot. Especially in the first half, as we learn what happened to the main characters immediately following the previous film.

Most of the comedy credit for that goes to women of the cast. Kristen Wiig, unrecognizable under puffy makeup, speaks as if someone taught her all the wrong vowels early in childhood, and I just wanted the whole film to be about her. Penelope Cruz, who dominates any moment she's onscreen, gives as much to this performance as she does to arthouse cinema. Christine Taylor... well, her appearance is one of the film's best — and creepiest — ideas.

Only a couple of the male actors make the most of their time in this overcrowded spectacle: Will Ferrell revives Mugatu as if he's spent time playing this nightmare clown every day for the last 15 years (but I doubt anybody's like to go around quoting any of his lines this time around), and — no spoilers — the actor who plays himself as a member of Hansel's family (no, entourage!) (no, orgy!)... that guy is so amazing that he almost makes you care about his absurd subplot.

Unfortunately, the biggest problem with Zoolander 2 is our hero himself. Ben Stiller walks through this as if he's already resigned himself to a failure. In the first film, Derek had a disability — he couldn't turn left. Here, he can't seem to move in any new directions at all; the script gives him little more to do than connect the plot's dots on a familiar circuit: a fall from fame, a second chance, and a superhero showdown, punctuated by a few uninspired references to favorite moments from the original. Add to that a half-baked story about him trying to be a good father to his indignant son (Cyrus Arnold, the only sympathetic character); a revelation of a Temple of Doom-like satanic cult (such a predictable idea for a sequel); and typical small-world revelations of familial connections, and you've got a sequel made of all previous sequels.

I once attended a reunion with friends I hadn't seen in 20 years. It was held at a flashy video arcade and bowling alley, where the crowds, the noise, the flashing lights, and the distractions made it hard to focus, to enjoy any worthwhile moments with old friends. Oh, there were hugs, there were laughs, there were stories told about the good times we used to have. But the attempt to make sure everybody was dazzled and entertained backfired so that it was, ultimately, wearying and frustrating — a non-reunion, where we had no chance to break any new ground.

That's what Zoolander 2 feels like. It's doomed to be one of those sequels that serves to make us think about what might have been.

But then again, maybe the time for Zoolander has passed. If you watch footage of that Yeezy Season 3 event — an exhibition of unparalleled self-indulgence, uninspired fashion, and ass-kissing hero worship — you realize the reality has become more outlandish and unhealthy than any satire could reach. (By the way, regarding Kanye: I have no doubt that there's some great music in there somewhere. After all, once upon a time, Kanye West did seem to be serving the music instead of building a self-glorifying empire. But any quest to focus on his recordings in the midst of his own self-hype is like an attempt to appreciate the music playing from ceiling speakers in a crowded shopping mall.)

There's too much talent on display in Zoolander 2 to write this off as a waste of time. Kristen Wiig can't not be funny. And Penelope Cruz is such a blessing to the big screen that I'd follow her right out of this movie and into any other story she chose. But there's just as much here to test our patience as there is to reward it. At one point, a prankster labels Hansel as "lame," and Derek reads it aloud as "lamé." Similarly, the filmmakers seem confused as to how much of this is satirizing a foolish fashion-world and how much is just, well, lame.

The Cure, New Order, Bruce Springsteen... reimagined.

Congratulations to Cameron Dezen Hammon on the release of Words Don't Bleed.

Cameron's a gifted writer. I had the honor and privilege of workshopping some of her evocative prose in Seattle Pacific University's MFA in Creative Writing program, under the direction of great writers like Paula Huston and Lauren Winner. Cameron's essays were some of my favorites of that experience, including those about her personal history of life in Houston; about the lingering shadow of 9/11 that has marked her life directly; and about her deep empathy with those who live in borderlands and in-between places, zones that make them seem insignificant to some and threatening to others.

I didn't find out until later that Cameron was as likely to captivate an audience with music as with writing.

I didn't find out until later that Cameron was as likely to captivate an audience with music as with writing.

What's more: I never expected to find myself revisiting some of these '80s pop hits. Nor did I imagine that these dude-centric songs would sound so strange and new if sung by a woman.

And these arrangements are surprising and inventive.

So if you've ever been a fan of George Michael ("Father Figure"),

Robert Palmer (she turns "Addicted to Love," a goofball rock anthem, into something seriously creepy, like Sarah McLachlan's "Possession"),

Don Henley ("Boys of Summer"),

New Order ("True Faith"),

Morrissey ("Suedehead"),

The Cure ("A Night Like This"),

Simple Minds ("Alive and Kicking"),

Black Rebel Motorcycle Club ("All You Do is Talk") (okay, they're not all from the '80s),

Hall & Oates ("Maneater"),

Bruce Springsteen ("I'm on Fire"),

or The Call ("I Don't Wanna") ...

... check this out.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dzjxdGgTps0