To Read or Not to Read: The Confessions of X

Who is X?

No, this isn't about the new X-Men movie. This is about a mysterious character, one who has remained a question mark through many generations of readers.

No, this isn't about the new X-Men movie. This is about a mysterious character, one who has remained a question mark through many generations of readers.

Now, thanks to the imagination and research of author Suzanne M. Wolfe (Unveiling), readers have a chance to draw closer to, and gain a clearer picture of, this character — who she might have been; who, in some ways, she must have been.

•

Many years of blogging have taught me not to launch a new series of posts on a whim. Often, an idea that sounds good at first fizzles when set in motion. And sometimes, my schedule changes and I run out of time to sustain a series.

So I am tentatively — very tentatively — beginning this new series: "To Read or Not to Read?"

Disclaimer: It will be intermittent at best, due to the busyness of my schedule in the coming months. But I've been meaning, for a long time, to start serving writers and readers more directly on this website. It's time to take a strong step in that direction.

Another disclaimer: I approach this subject with fear and trembling. Blogging is a fast-paced and often rough-drafted affair. While I'll focus on the excellent writing of other writers, and while I'll do my best to write these posts carefully, this is my blog. This is where I write and share things that are written hastily and spontaneously. I wish I had the luxury of time to revise and edit these posts to a point that they're worthy of being published in print, but no — my writing life, which happens in spare moments outside of my full-time employment, does not currently afford me such time. So bear with me.

With all of the best intentions, here goes: A series focusing on the first chapters of books in my library.

Let me revise a line from Roger Ebert: My focus will not be on what the books are about — my focus will be on how those books are about their subjects. It will be about the craft of writing. I want this series to encourage readers to pay closer attention to the art of what they read (assuming that they actually read books), and to encourage writers to bring new lenses to their own writing for purposes of revision (assuming that they actually revise).

My primary questions will be these:

- What do the opening pages of the book in question accomplish?

- How do they accomplish it?

- Who is the intended audience of this book, based on how it is written?

- What can we learn about capturing readers' attention without stooping to cheap tricks, sentimentality, or heavy-handed "shock and awe"?

- Do we want to keep reading?

- And if so, why?

This series is inspired by the discipline of literary annotations that I learned while earning my MFA in Creative Writing at Seattle Pacific University, with the guidance of my mentors: authors Paula Huston and Lauren Winner. While the 62 annotations I wrote there were more formal, and less like a first-person journal entry, they taught me to find joy in a regular ritual of reading and then writing about the craft of what I've read.

And I'll begin with a book that seems like an obvious choice for the initial post...

The Confessions of X, by Suzanne M. Wolfe

•

Want to read an interview with author Suzanne M. Wolfe? She was interviewed by her husband Gregory Wolfe, founder and editor of Image, at Image journal’s blog, “Good Letters": Part One, Part Two.

Want a quick glimpse of what the book is about? You can read all about it here.

But rather than focusing on a plot summary, I want to walk us into the book without any setup, just to see what we can gather from Chapter One.

If you want to get the most out of this, read Chapter One first (it's short). You can access the text through "Look Inside" at Amazon, or via this link at Google Play.

When you're finished, come back and read my page-by-page commentary on just how Wolfe casts a spell over her readers.

•

Paragraph One: The curtain lifts on a courtyard view: We see a well, and we see it through the eyes of a first-person narrator. It's a present-tense description — this is happening now, with engaging immediacy.

A "young man in a dark tunic comes to draw water," and soon the dogs are lapping up what's been spilled. Thus, even before we know our narrator, we know this: Thirst. And not just thirst, but a blessing, a grace, as the dogs are only drinking because of what's been spilled as the boy draws water.

But what do we see most vividly in this paragraph? The boy himself — his neck showing "white below the hairline, tender like the milky stems of new grass in spring." Why is the narrator so intent on the boy? Right away, whether the reader knows it or not, the seed of a question has been planted. This narrator notices this youth, takes some tender time with details. Why? Is this boy an important character? Does he resemble someone?

The text doesn't explain this. It's a suggestion. It gets the imagination working. That's what good art does. It invites participation. We begin asking questions, making guesses, collaborating with the author on image-making.

Paragraph Two: And then the boy blesses our narrator with a gift: "Here, Mother." The intrigue deepens. Mother? He cannot be her son, for she has observed him as a stranger. But he knows who she is... and he calls her Mother. Perhaps she's from a convent, or perhaps this is a formal title of someone known and respected.

Paragraph Three: Our narrator does not introduce herself formally to us. But already we are gathering information through osmosis, as events unfold. She replies to the boy "I think you, you who could be the son of my son's son." Aha! Her age comes into focus.

Paragraph Four: She describes a very, very old woman she once saw, with vivid physical details. "I have become that woman," she says. Notice how effortlessly, and how creatively, the author sketches her narrator's appearance without compromising a first-person point of view. And we might assume that this woman who is "old past counting" must be someone with all the answers.

But in Paragraph Five she humbly deflects that assumption:

When the people in the courtyard ask me what they must do in such times, I am silent; when they ask where God has gone, I am silent; when they show me the bloated bellies of their children, I look away. They think endurance is wisdom and perhaps that is so, but it is not the wisdom of men but of women, for though we live longer, history does not remember us and so we are a mystery to each generation.

Without stepping out of the specifics of her circumstances to deliver exposition, the narrator has just opened up questions that sound like they might frame the whole novel: Where is God? Why all of this suffering? Do faith and experience lead to answers?

And, perhaps more importantly: What is the wisdom of women?

Most readers will already know, going into this book, that our narrator has a history with a famous figure. But this paragraph gives us our first textual clue that this is the "confession" of a voice that has been kept offstage. In fact, we'll find that it's the the voice of a woman who influenced one of literature's most famous innovators. This will be the opening of a treasure trove, a glimpse of world-changing events, of world-changing ideas, through a head and a heart that history's male voices have neglected. In this, there is a sort of reconciliation — the provision of a puzzle's missing pieces, and a gesture of justice and compassion in honor of a human being who was unfairly silenced. She is, in fact, the "X."

What's more, we may begin to guess what the author of this book is, herself, driven to explore. Suzanne Wolfe, we can safely assume, has questions on her mind, questions that require her to take imaginative measures, questions that require something more than mere reason. The "What if?" of fiction allows us to entertain possibilities in ways that mere argument cannot. We can consider speculative scenarios to see what "rings true" beyond the grasp of clinical explanation. I suspect that Wolfe herself did not know where this story would take her, or what it would reveal. Authors who are open to discovery, who perhaps undertake a novel in order to discover, often write with a contagious energy.

In the next few paragraphs, notice how gracefully we're given a geographical and historical context without ever lifting our attention from the matters at hand, without drifting from the narrator's immediate scenario. Notice how we begin to learn the details that have shaped her, the scars and burdens she carries.

And if there is any doubt about who this mystery of history might be, that is all but solved — at least for a well-read audience — at the bottom of Page 2:

I have come to this place to sit beneath the pear tree he planted to remind him who he is.

In the history of theology, memoir, autobiography, and philosophy, there is one pear tree that towers over the rest. It's the pear tree that became the scene of a crime, which led to a profound evolution in the character of Saint Augustine.

And so the stage is set: The woman Augustine loved and "left behind" is our guide into this untold chapter of history, into an intimacy that Augustine's own confessions denied us.

A note about audience: These first pages are written with eloquence, with evident research, and with a poet's vocabulary. What can we discern about the audience for such a book? I suspect that it was not written for people who merely want to be entertained, who need constantly sensational events. I suspect that it was written for an educated audience, one that is interested in history but that can also believe that figures from centuries ago can still speak with relevance into our lives. I suspect that it is written for people who are willing to be patient as the author slowly draws them into an immersive story. I suspect that it will not appeal to readers who just want to read about young people, or about violence, or about good guys versus bad guys, or about the easily intoxicating fizz of an adolescent's idea of love. It's about — and for — adults who care about becoming fully human, rather than adults who want the shallow comforts of a sanitized or simplistic story.

I could stop there, but I want to highlight what happens in Paragraph Eleven, so keep reading.

An old dog makes his home in the courtyard and lies beside me when the shadows shrink to knives against the walls.

The ensuing scene finds our narrator writing with affection for this animal, one who does not fear her (perhaps because he, too, is old and suffering?), one who has been "abandoned by his master in the exodus" as she was. How does she behave with this animal? She treats him tenderly; she feeds him bread "piece by piece." There is no mention of old Augustine, but we are already being schooled in the character of this "abandoned" woman, and how she may feel toward her famous former lover.

This is one way to develop relationships in a story: To suggest things about a character's attitude, thoughts, and behavior toward another by a forerunner.

And I would be remiss if I closed my reflections on this chapter without highlighting just how much Wolfe's prose wants to be read out loud. Read this line about the narrator's lost son from Paragraph Thirteen: "Never have I loved with such rapture, that tiny body bequeathed me out of blood, a long laboring through the night and then the day coming and with it, you, my son."

This is the voice of an eloquent and educated character, someone more learned than most women of her day. That may come as a surprise. It may hint at the revelations to come.

And what is more – there is poetry, music, in this speech. The alliteration of body, bequeathed, and blood; the rhythms of the line; the obvious and the subtle rhymes.

When we arrive at the end of this short Chapter One, we read this:

Long ago he said that when something is lost to us, its image is retained within us until we find it again. Crippled by the loss of it, the memory demands that the missing part should be restored. This I believe.

An Augustine scholar might have been tempted to begin the chapter with this — a huge idea, one that demonstrates knowledge of Augustine's beloved memoir. But Wolfe is wise to close with it. We have been drawn in by specifics, by suggestiveness, by a scene, by characters, by beauty, by music. And now, as we arrive at this large idea about memory, loss, and longing, it feels earned. We have particulars that fill in the blanks. We feel the love within our narrator for her long lost companion, her respect for his intellect—and yet we don't see her as a woman who exists to exalt her man. She is an individual. An equal. She has thoughts of her own and a voice worth hearing. And through her recollections, we will read Augustine's own confessions differently.

More importantly, we will — if our conscience is awake and alert — become more inclined to seek out the voices of women on matters that have historically been left to men.

•

So... to read or not to read?

I don't know about you, but I am hooked. I'm excited. So much work has been done in such a few pages. This novelist knows what she's doing. And this novel wants to expand my understanding and my world. Let's grow.

10 Cloverfield Lane (2016)

On Friday, my first free day after my MFA graduation, my friend Jordan and I celebrated by going to a concert in downtown Seattle. The show was advertised for 8 p.m., but when we arrived we learned that the band we'd come to see — Shearwater — would not take the stage until 11 p.m.

What to do for three hours?

So we walked to the nearest cineplex and found that we were just in time to see 10 Cloverfield Lane. I really had not seen this coming. What a surprisingly satisfying twist for my evening.

And that's what I kept thinking to myself through 10 Cloverfield Lane's various turns: "I really had not seen that coming. What a surprisingly satisfying twist!"

The film, and all kinds of reviews, have been out for a while. So, rather than deliver a review that follows the formula you can get elsewhere — the plot summary detailing how a young woman gets trapped in a survival bunker with a dopey young dude and an unstable tyrant; the origin story of Cloverfield; the usual praise for franchise genius J.J. Abrams, the uncanny correlations with the recent Oscar favorite Room — I decided to do something different. I asked this website's most dedicated supporters if they had any questions.

And lo... they did.

So here's an unconventional report on 10 Cloverfield Lane. Thanks to Daniel Melvill Jones, Evan Cogswell, Laure Hittle, and Joshua Wilson for the questions:

Is this movie just a flash in the pan?

A surprise everyone will talk about in March and will forget about come July?

Is it worth paying attention to? Because that trailer was kinda intriguing...

I think it's going to rate high on my list all through the year, and Dan Trachtenberg has immediately become a director worth watching.

There is so much to love about 10 Cloverfield Lane: The references to Psycho, Alien, and Die Hard. The brilliantly strident and suspenseful score (which the Filmspotting guys rightly highlight as Herrmann-esque). The editing, which is edgy and efficient. The Chinese puzzle box of the film's deceptively simple underground bunker environments. The jump-scares. The sound effects — especially the door to Michelle's cell, the creak of which seems to have been synthesized from the sound of a crowbar to the skull and a woman's final scream.

And three cheers for Mary Elizabeth Winstead, delivering brilliantly in the lead role she's long deserved. I've wanted to see her take a big swing for the fences, and here she takes it, and the results are glorious. 10 Cloverfield Lane openly nominates her to be our next Sigourney Weaver, and I find no reason to protest.

Which variety of M&Ms goes best with this film?

M&Ms with Pretzels.

Because the tension in this movie, which keeps changing as you assess and reassess what you believe to be true about the situation, will tie your nerves into pretzels. Thus, it's satisfying to crush bits of pretzel between your teeth.

I'm assuming that this is a sequel — or a prequel — to Cloverfield. Is it?

That is a very good question. I'm glad that that answer turns out to be what it is. But I don't want to say much more than that.

Do I need to see the first one before seeing this one?

Cloverfield? Look, when it came out I wasn't even aloud to go to the theatre. I just remember lots of talk about the shaky cam and the post 9-11 shock. So what's the big deal?

Full disclosure: I've never seen Cloverfield. I know it's a monster movie that works like a mash-up of Godzilla and War of the Worlds. The reviews persuaded me not to make it a priority while it was in theaters. Perhaps there are things about this film I don't understand because of that... but for what it's worth, I didn't perceive any problem. This experience works as a standalone film — a solidly satisfying time at the movies.

Is this a monster movie?

Oh, yeah. But not in the way you're thinking.

I've grown to enjoy John Goodman thanks to his extended partnership with the Coens.

His presence here has me intrigued. Should I be?

Definitely. The great John Goodman is back in the kind of role he's had far too rarely since Barton Fink. He makes Howard utterly unpredictable, unreadable, hilarious, and sometimes terrifying. I wouldn't mind seeing him remembered next award season.

What did the folks at 12 Cloverfield Lane think during the events of this film?

A very good question. For most of the movie, though, you'll be wondering: Are there any folks at 12 Cloverfield Lane? Is there anybody out there at all?

If there is anybody next door, I suspect that they spend the film's period of time wondering "What are all those strange noises?" and "Why does it sound like John Goodman's voice is roaring up from the earth?"

But I would hope that they were too busy reading and discussing Through a Screen Darkly to notice.

Jeffrey, why are you spending your valuable time on (what seems to be) a monster flick?

From the hand of J. J. Abrams no less.

Don't you (and we) have better things to do? Can this benefit us at all?

Well, it gave Jordan and me a high-spirited time at the movies. We laughed. We panicked. We held our breath. We jumped. We cheered. We saw a smart hero thinking her way out of a trap. We saw a villain who was, in part, sympathetic. We saw heroic acts of selfless courage. We saw an excellent display of cinematic skills. We saw a demonstration of movie literacy. And we experienced a screenplay that always kept us guessing. That's more than enough for me.

My three favourite film makers are Wes Anderson, Terrence Malick, and the Coens.

Do you see their hands on the influence of this flick? Whose influence do you see?

I see a lot of Alfred Hitchcock, David Fincher, Edgar Wright, and Steven Spielberg.

Winstead seems to be wearing a tight tank top for most of the film.

How does this film treat women, in an age of Wonder Woman costumes

vs Mad Max's de-objectified harem?

I think she's dressed fairly sensibly, considering her circumstances. The costume emphasizes her vulnerability, which makes her courageous actions that much more arresting. Also, I think the costume ends up strengthening the film's homage to Sigourney Weaver in Alien.

Did you like it so much just because your expectations were lower than, say, Hail, Caesar!?

Well, my expectations on this one weren't very high or very low — I didn't know what to expect. That worked in my favor, I think.

Is this a sign of new life for the mainstream post-apocalyptic film?

Is there any hope for the future of mainstream film?

(All my friends went to see Batman v. Superman and I'm kinda depressed about this.)

There's all kinds of hope for commercial cinema — post-apocalyptic films and otherwise!

I think we're in a pretty good place, actually. Sure, there are the juveniles who waste our time like they waste their filmmaking resources — like Michael Bay and Zack Snyder. But there are a lot of wild imaginations who are getting good chances to show us how it's done: Edgar Wright and Drew Goddard, for example. They make brilliant, satisfying, apocalyptic movies with heavy joke density, genre innovations, and sharp writing.

I wish more Americans would discover Stephen "Kung Fu Hustle" Chow: His new movie The Mermaid is the most satisfying fantasy film, action film, and comedy I've seen so far this year. There's no reason for him not to be hugely popular. It's just that Sony blew it and didn't distribute his movie.

I hear you've been doing some new fiction writing.

If this were your story, what chapter would you add?

What twist would you throw in? Which character would you most like to borrow?

I can't speculate much without dropping spoilers about this movie, so let's just say that I would love to pick up where 10 Cloverfield Lane leaves off and write the next installment. There's so much potential for this to become an intriguing franchise in which the episodes are only loosely connected, and each chapter tries to outdo the last by confounding our expectations.

There will be a lot of talk among moviegoers about whether or not this film's finale really works. The way Trachtenberg sets everything up, the movie could go in any of a number of strange directions. Lucky for us, he and and his team of writers (which includes Damien Chazelle, who wrote and directed Whiplash) drive this thing headlong into the most absurdly hilarious direction available. I was laughing out loud in giddy delight.

Don't let anybody spoil this movie's twists for you. In retrospect, I have to salute whoever designed the trailer, which gives away surprisingly little of the film's grand scheme. I'm grateful to have walked in knowing next to nothing about the story. It was one of those rare pleasures of discovering one smart surprise after another.

•

Oh, by the way... after the movie we went back to see Shearwater.

And the surprises kept coming. When the band came back, after a glorious show, to play an encore, lead singer Jonathan Meiburg said, "Seattle, you have options. You can go home and sleep, cuz it's been a long day ... Or you can stay and listen to us perform the entirety of David Bowie's album Lodger."

And he wasn't kidding.

So yeah, I'd say that I had pretty fantastic graduation party.

Who I thanked on my MFA graduation day

One week ago today — Saturday, March 19, 2016, at Camp Casey Conference Center on Whidbey Island — I was invited to the podium before my special guests, as well as the students, faculty, and staff of Seattle Pacific University's MFA in Creative Writing.

This was the moment: I would give a reading from my final manuscript — the best pages from two years of writing.

I wish you could have been there.

Lauren Winner introduced me. And while I won't share what she said here, I will tell you that I treasure what she said, and will carry it with me as a source of inspiration for the rest of my life.

I also cannot share what I read, as I hope to publish it someday — either in a journal or a book, or both.

I will, however, share with you my own introductory remarks from that presentation. Because I am very, very grateful to a lot of people whose support enabled me to climb a high mountain.

Over those two years, I read 62 books and wrote papers on them all. I also wrote several longer critical essays, as well as hundreds of pages of original creative nonfiction. I did this while working full time, sustaining a regular music column, and blogging here for you.

And I couldn't have done that without these people.

Here is what I said before the reading:

To Gregory Wolfe, the director of Seattle Pacific University's MFA in Creative Writing program. Greg is making of himself a sort of living sacrifice that Image, the Glen Workshop, the Chrysostom Society, and the MFA program might become for us — at least for me — a sort of promised land I didn’t know I’d been seeking.

To Aubrey Allison (the MFA program coordinator): Everybody talks about how graceful you are. I think you’re a badass with a deadly sense of humor. Thanks for showing all of us so much love.

Thanks also to Tyler McCabe, the Image program director, and all on the MFA/Image team, and to Seattle Pacific University. I’m hard-pressed to think of anywhere else in Christian higher education that shows such respect and support for artistic freedom.

Paula Huston — I’ll say that I’m lucky, but I mean that I’m blessed to have begun in time to run the full course of the program with you. Everything Alissa Wilkinson told me was true: Your tender and truthful responses to my essays are still doing good work in my head and heart.

Lauren Winner: Who cornered me after I spoke at a workshop, asked me questions about my life plans, and then proceeded to host a spontaneous intervention, with the help of John Wilson from Books & Culture, helping me regain the vision for my life that I’d had to abandon two decades earlier. They convinced me that an MFA was the best possible course of action. And then, Lauren, thank you for not going easy on me — for your uncompromising criticism. Your lenses exposed bad habits in my writing that I hope I am learning to break. In the interest of avoiding what you call “overwrought language” — I will stop there.

To Robert Clark, who persuaded me to take the Creative Nonfiction track when at first my mind was set on fiction, and who hosted a Seattle writing salon, so I could enjoy his critiques free of charge. I have no regrets about CNF, Robert — just jealousy for those who get to dream up stories with you and Gina Ochsner.

To Scott Cairns, who has been a counselor in person and in poetry for almost 20 years; to Jeanine Hathaway and Jeanne Murray Walker, for sharing my appreciation of Anne’s poetry. To Luci Shaw, for praying with me during one of my low points. To Warren Farha, who served up heaping plates of literary beauty, nourishing my spiritual formation.

To you, my MFA community — especially Bob Denst — thank you for your generosity in everything from listening to libations. Thanks, Nick Olson, my CNF brother; the current CNFers, from who I have just begun to learn; and to a certain piece of furniture — some of you know what I mean.

Now, of those who launched with me at the starting gun, only one has kept pace with me to cross the finish line. Christian Downes, I have no boring friends, but you are the friend who is farthest from boring. You first impressed me with your style, then with your writing, and recently with your close-readings and critiques. Thanks for sharing pints, and thanks for sharing poems that translate for me as a call to stillness, humility, and openness to natural revelation. When people ask me if we did that cohort tattoo bonding ritual, I’ll just say, “Yes, we did, but I can’t show you mine because Christian’s the one who actually wears it.” And then I will realize how unsettling that sounds, and I’ll point at something up in the sky, turn, and run.

Finally, my family:

Thank you, Mom and Dad. You taught me to value reading and writing; you let me be a weird kid for whom being sent to his room was a reward instead of a punishment; and you let me spend more time with a typewriter than a television. I can honestly say that I have never experienced what people call a “crisis of faith” — and that’s because your love for each other and for God has shown me what is possible. (And no, that is not "overwrought language.")

Which brings me to a grace I do not know how to describe. Thank you, Anne. Thanks for listening to all of my complaining about my packets never being good enough. Thanks for making every potentially lonely evening of homework into a study party. You are my first reader, my first responder, and a fourth mentor. I think of these two years as a sort of parenthood — raising pages with lives of their own — and they've been the richest of our 20 together so far. And your poems are like tuning forks for my disordered and sometimes decimated attention. When I read them, everything dissonant in me resolves for a time, and I can rest.

So, that's how things started.

And then I read an essay.

And there was much rejoicing. During one of the week's festive occasions, my friend Bob Denst snapped this rare picture of me actually smiling.

And there was much rejoicing. During one of the week's festive occasions, my friend Bob Denst snapped this rare picture of me actually smiling.

This is the end of two unforgettably inspiring years, and the beginning of a new phase in my life as a writer.

I have my evenings and weekends back to do the writing I was born to do. With God's help, eventually I'll find more even more hours to apply myself to my true vocation. And with the help of this MFA, hopefully I'll find a good opportunity soon to teach classes in film studies and creative writing.

I appreciate your prayers and support.

Cheers, everybody.

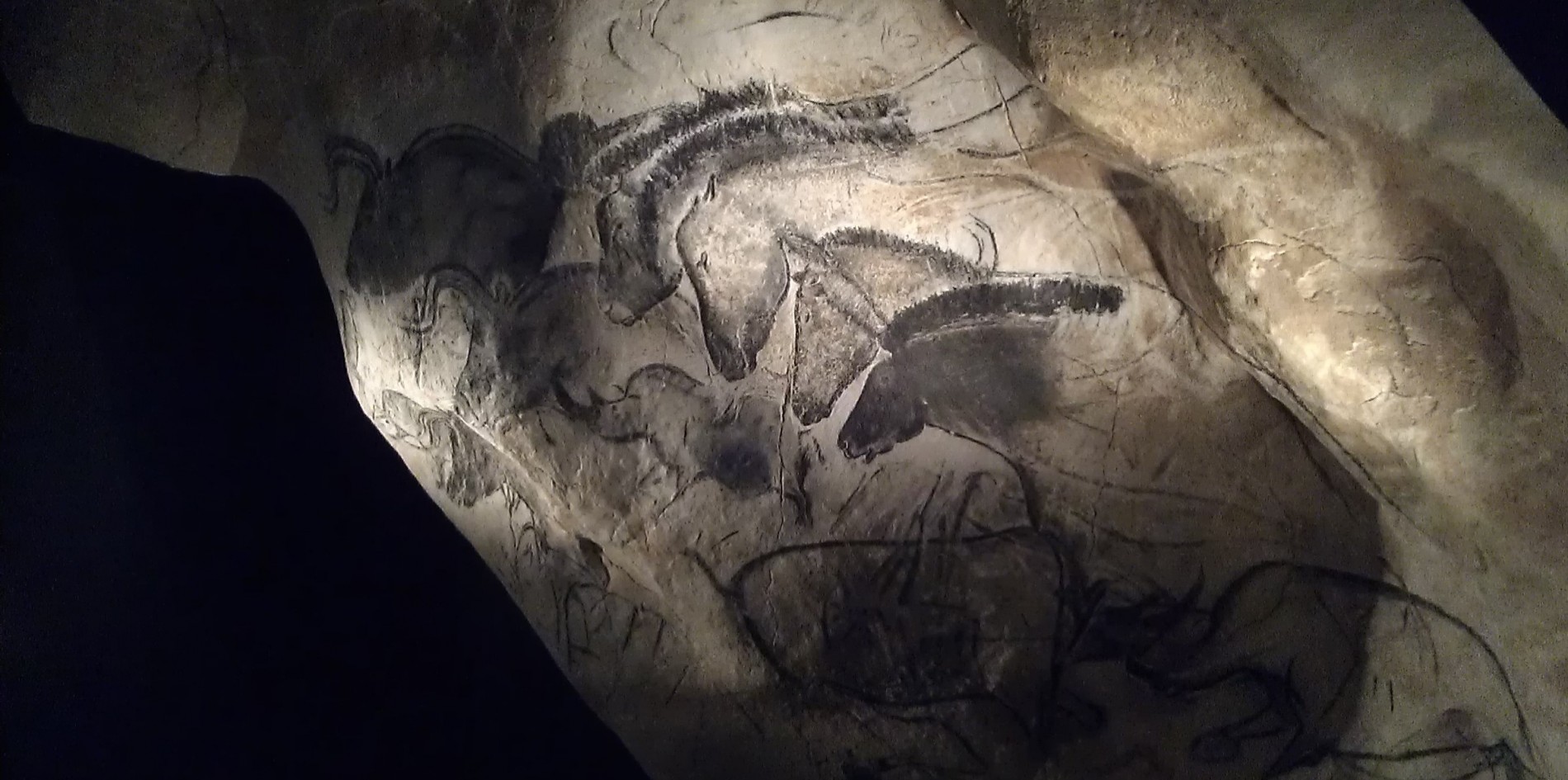

Cave full of treasure

In "The Cave and the Cathedral," an essay published in Image, Gregory Wolfe — the founder and editor of Image, and the director of Seattle Pacific University's MFA in Creative Writing program — writes about seeing Werner Herzog's film Cave of Forgotten Dreams, and what this cinematic tour of the world's oldest art gallery, the Chauvet Cave, revealed to him.

It’s a typical Herzog film—personal and eccentric, marked by moments of insight and marred by a number of strange non sequiturs—but it may be the best footage of this cave the world is ever likely to see, given the French government’s decision to refuse public access to it. When I saw the hand-held camera lights illuminate the first image on the wall, I found myself transfixed.

What he goes on to consider transforms this essay from a film review into a contemplation of what such "primitive" art can mean for us today.

I've read this essay several times and I've heard Wolfe present it at the Glen Workshop. It gives me chills every time. And it's the kind of writing that makes me want to do my own work of writing about film better.

If you like it, then take note: It's the opening chapter of Wolfe's new book The Operation of Grace.

Knight of Cups (or, All My Favorite Critics Disagree)

The Seattle press screening of Terrence Malick's Knight of Cups is happening next week during my office hours at Seattle Pacific. That's the problem with being a film critic but also being, you know... employed. The screenings for press are often held midday, when I can't leave the office. So I'm going to miss the movie that Looking Closer readers most want me to review in 2016.

(If any publicists are reading this, hey — if I had a screener link, this Malick fan would be publishing a full review right now. That's how I reviewed To the Wonder, anyway.)

That's alright. I like watching Malick late at night because there's something dreamlike about slipping into the current of his distinctive style — the challenge of his poetic juxtapositions; the movement of Emmauel Lubezki's cameras, which seem to be guided by wind; the tempestuous weather of his musical score; the mesmerizing murmur of intertwined interior monologues.

And, since a tidal wave of reviews by reliable and insightful critics is currently flooding film sites across the Internet, I'm tempted to take my time and write something different than a review after the surge subsides. I'll until I've marinated in it for a while and then write about what it opens up to me in my own life. Malick films tend to have that effect.

Maybe I'll find that I relate to Rick (played by Christian Bale) — showbiz pilgrim making melancholy progress through the flash and dazzle of a sex- and success-obsessed Los Angeles. His lifestyle's nothing like mine, but as someone who lives in a whirlwind of art and entertainment, I can imagine the women that lure and intrigue him being like the art that beckons to me, often with false promises of profundity. Or maybe I'll find that this is a greater departure from the kind of work that I consider Malick's best — the films that give their characters distinct and human voices instead of vague philosophizing.

Who knows? My favorite critics are more divided over this one than they are over most films. Once again, Malick has inspired some, unsettled some, and exasperated others.

Matt Zoller Seitz at RogerEbert.com — clearly aware that his mentor Roger Ebert wrote his very last review in a state of rapture with Terrence Malick's last movie, To the Wonder — picks up where Ebert left off with Knight of Cups: enamored, enchanted, inspired. He calls it "a film that teaches you how to watch it," and then proceeds to to write his review in the film's meandering interior-monologue style. He calls it

...one of the most committed examples of the principle “form follows function” that you’ll see—so much so that many viewers will find it impenetrable and intolerable.

...

The whole movie is a collection of ellipses of different sorts, a series of suspended moments, cordoned-off spectacles, fleeting instants that could be beautiful or emptily pretty, meaning-filled or meaningless.

...

Everything, everyone, every place, seems disconnected here; as superficially lovely as "Knight of Cups" is, it's Malick's bleakest film in some ways. Treat the world as it deserves to be treated, Rick's father says. There are no principles, only circumstances. Nobody's home. The lushness of the imagery contradicts him, but without shutting him down.

He acknowledges — somewhat incredulously — that many if not most critics will be more frustrated than inspired.

Justin Chang, at Variety, acknowledges this as well:

Those who have had their fill of the director’s impressionistic musings will find his seventh feature as empty as the lifestyle it puts on display; for the rest of us, there’s no denying this star-studded, never-a-dull-moment cinematic oddity represents another flawed but fascinating reframing of man’s place in the modern world.

Chang is particularly aggravated by "the degree to which Bale’s magnetism has been drained away here." But he adds:

... Malick’s view remains a deeply and unapologetically Christian one; Rick’s story may echo that of the lost knight, but it also has obvious roots in the parable of the prodigal son, and throughout “Knight of Cups” you can just about make out the voice of a father patiently, insistently calling his wayward child home. It’s that instinctive compassion that keeps the film from turning crushingly didactic, along with the myriad aesthetic pleasures afforded by the Malick’s typically dense layering of image, sound and music.

Glenn Kenny, at Some Came Running, says he's "appalled":

Glenn Kenny, at Some Came Running, says he's "appalled":

I admired The New World, I loved Tree Of Life, I was challenged by and ultimately admired To The Wonder, and all the while I recognized a quality, maybe I could call it an undercurrent, within Malick's work that had the potential to trip it/him up very badly, and in Knight Of Cups, I thought, it did. This is (part of) what I wrote to the representative of the film who had invited me to see it those months ago: "So. I thought the movie beautiful, which is almost a given, but I also found it frustratingly evasive. Maybe it's because the milieu is so specifically Hollywood but I felt that the elliptical, indirect narrative style felt like a kind of a cheat. I also felt that the supposed spiritual emptiness experienced by the lead character was overly aestheticized, and there was some weird special-pleading male privilege in his flitting from beautiful woman to beautiful woman and yet always feeling so empty and pursued by the ghosts of his failed familial male relationships. So I was kind of brought down by the whole thing."

A.O. Scott at The New York Times agrees, even if he wasn't as fond of To the Wonder as Kenney:

... Mr. Malick has always been more interested in states of being than in cause and effect. His philosophical temperament and his sensual disposition can produce work of haunting, almost ecstatic power — I certainly feel that way about “The Tree of Life” — but in “Knight of Cups,” as in “To the Wonder,” the deployment of beauty strikes me as more evasive than evocative.

And the deployment of beauties is more exploitative than anything else. The nameless, voiceless, topless women — whose lithe bodies at once symbolize Rick’s existential quest and distract him from it — might as well be premium-cable eye candy. Like Paolo Sorrentino’s “Youth,” “Knight of Cups” settles into a lukewarm bath of male self-pity, a condition perhaps more deserving of satire than sanctification.

Ah.. but maybe not? Sophie Monks Kaufman writes at Little White Lies:

Existentialism from a rich playboy makes it tonally comparable to Paolo Sorrentino’s The Great Beauty but this also an absorbing study of the stresses of being a womaniser. Really. ...

A cynic might say that Malick has filtered the objectification of women through arthouse sensibilities, but he is a step ahead. This is the story of a man whose drug of choice is women. The way he sees them is necessarily at a distance. This is his whole issue. Malick has crafted the perfect philosophical basis for obsessively filming the world’s most beautiful woman in a way that is sublimely tasteful and reverent. All the while something is scratching at Rick from beneath. ... As Rick leaves gracious ladies behind, the idea suddenly dawns that maybe the pearl is meaningful communication in all its painful self-interested candour.

Brett McCracken at Christianity Today says,

Knight’s impenetrably subjective posture (basically fragments of image-memories from Malick’s psyche) and resistance to “plot” is in a weird way the key to unlocking its mystery. If the film has a point, it is that “discerning a point” is harder than ever in a world where mediated experiences of “beauty” are more ubiquitous, accessible and customizable than ever, but less and less tied to rubrics of meaning.

And of the film's cast of unclothed beauties he says,

This aspect of Knight, taken at face value, is almost enough for me to not recommend the film. The effect of the repetitive, intentionally indistinguishable sequence of Rick’s liaisons with women (certain shots, on beaches or in convertibles, are repeated with multiple women) is numbing, grotesque, squirm-inducing. ... The audience becomes increasingly uncomfortable. Beauty shouldn’t be this sleazy, this empty, to the point that we want to slink in our seats, look away, or walk out.

But this is where Malick’s critique of Hollywood, as a sort of stand-in for the larger spiritual “searches” of mankind, comes into focus. ... [Rick's] in a dream world, half asleep, making no progress on his spiritual quest because the beauty that should be pointing him higher is instead luring him deeper into idolatry.

David Ehrlich at Slate begins with this: "What if the Entourage movie had been directed by Terrence Malick?... Ari Gold … Johnny Drama … always you wrestle inside me."

Then he expresses frustration with Malick's increasingly steady focus on the search for meaning, which denies his films the surprise of "serendipity" that once graced his early masterpieces.

the problem isn’t that Malick is repeating himself—after all, the process of revisiting the same material every year is the bedrock of most theological study, and even true believers find it hard to remember Rick’s ultimate takeaway that suffering is an expression of God’s love. The problem is that Malick never forgets about the pearl. ... Malick has moved from self-discovery to self-affirmation; he knows exactly what he’s looking for, and Knight of Cups, for all its splendor, made me wish that he could take a swig and forget.

Even farther out is Alissa Wilkinson, chief film critic of Christianity Today. You can read her Tweeted responses at Storify. [Udpate: She might have written a full review for CT, but McCracken beat her to it.]

UPDATE #1: March 7

Elijah Davidson talks with Michael Wright at Reel Spirituality.

And Richard Brody at The New Yorker posts the most enthusiastic exaltation of the film I've encountered.

Is there a better review of Raiders on the Internet?

C.S. Lewis once said, "An unliterary man may be defined as one who reads books once only." Ah, but there are so many books! How does one decide which volumes to read a second time?

Lewis's line might be revised to apply to moviegoers: Those who truly love cinema know that it is better to watch a good movie twice than a good movie and a bad movie, and that great cinema is defined by how it goes on rewarding viewers with each successive look.

But what makes a great film review? A review is successful if it demonstrates the reviewer has been looking closer, has been examining the film through a variety of lenses that reveal different aspects of its quality. A great review makes me see the film with fresh eyes. And when the reviewer's gaze shows me new things to appreciate, I find myself eager to go back and watch it again. That's why I sometimes revise my film reviews on this website. That's why I continually update my "favorite films of the year" lists going back over my whole lifetime.

When I'm asked to name my favorite film, my typical answer is this: On Sunday, Tuesday, and Thursday, it's Wim Wenders's Wings of Desire. On Monday, Wednesday, and Friday, it's Three Colors: Blue. But on Saturday? It's Raiders of the Lost Ark. These are the three films I have watched most often in my life, and they're the films I suspect I'll continue to revisit the most for years to come, noticing more every time.

I remember reading Roderick Heath's review of Raiders of the Lost Ark in 2012 and thinking "I need to read every review this guy writes."

I remember reading Roderick Heath's review of Raiders of the Lost Ark in 2012 and thinking "I need to read every review this guy writes."

Here's a sample paragraph:

Raiders’ historical setting didn’t just allow the filmmaker to play with retro tropes, but also offered a chance to escape the killjoy angst of the ’70s, though there’s still a definable edge of the mistrust of officialdom in the portrayal of the feds who commission Indy’s quest. The film’s final joke riffs on a main theme of Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977), where a source of inestimable wonder and dread is last seen being stashed away in a colossal warehouse under bureaucratic auspices so the world might forget such destabilising influences exist. This scene itself is almost a meta-commentary on the film’s own driving principle. Trucking in the Nazis as baddies and making Indy a premature antifascist, however, signals a less cynical sensibility. The results of Indy’s gallivanting through the streets of Cairo combating Egyptian goons initially skirts the endemic racism of much of the old pulp pantheon, but other aspects, like Indy’s dogged good friendship with Salah and the way the Egyptians who fill the background slowly shift from being Nazi tools to active supporters of Indy, give the film some links to the egalitarian spirit of WWII-era movies like Sahara (1943). Salah likes reclaiming the heroism stolen by imperialists for themselves back, singing Gilbert and Sullivan’s anthems of official heroism but freeing them from nationalist specificity: he is the “monarch of the sea”; “A British man is a soaring soul” describes himself, Indy, and Marion. Moreover, as in subsequent episodes, the sense of underlying truths in the world’s mythical pantheons demands a slow adjustment to a deeper empathy and understanding of what those pantheons imply about the human condition and its origins.

This is a voice of authority, one I quickly come to trust because I don't hear sweeping generalizations or axe-grinding or mere fanboy gushing.

Alas, I haven't fulfilled that vow. (Mental note, Overstreet: Next time you're on a long flight, catch up on your Heath.)

[Read more about Jeffrey Overstreet's personal history

with Raiders of the Lost Ark in Through a Screen Darkly,

a memoir of dangerous moviegoing.]

But when I discovered some colleagues admiring this review last week I realized that I should feature it here as one of the Looking Closer Exemplars: it's a standard-setting work of film criticism.

If you want to read more by Roderick Heath, follow Ferdy on Films and This Island Rod.

Have you read a more observant and thought-provoking review of Raiders of the Lost Ark? If so, please post a link in the Comments!

P.S. Here's a little something handmade by my friend Damian Arlyn:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=i70ihENC7wE

Risen (2016): a Looking Closer film forum

I admit — I'm intrigued by the mixed reviews for Kevin Reynolds's Risen that are coming in from reliably discerning friends and film critics.

I believe art exists to invite us to explore questions. When it sharpens its intent to "deliver a message," it ceases to be art, and I lose interest. Thus, most "Chrstian movies" — as well as most movies about Biblical subjects — don't interest me. They come across as manipulative salesmanship, or as preaching to the choir.

But when a movie about Jesus gets some admiration from the religious-press reviewers who understand the nature and purpose of art, and when it also gets some praise from film scholars who have consistently offered rewarding perspectives, I'm ready to buy a ticket. Well... at least a matinee ticket.

Steven Greydanus (at National Catholic Register) says Risen is better in the early going, showing us the Passion "from a decidedly unfamiliar perspective. Risen might be the only Jesus film in which we first encounter Jesus on the cross, already dead or nearly so." He's disappointed that the film's Jesus "says nothing very surprising," and asks, "Shouldn’t the risen Lord sound more profound than Yoda or Aragorn?" But then he concludes with this:

For all its issues, Risen remains more interesting in some ways than a straightforward dramatization of the Gospel story like Son of God. It’s far from fully satisfying, but for devout viewers its strengths may outweigh the defects.

Peter Chattaway offers a close scene-by-scene reading of the film. In his review at FilmChat, which he published first, he invokes Roger Ebert:

Movies, as Roger Ebert liked to say, are empathy machines, and one of the great things about Risen for its first hour or so is how it allows us to imagine what it would have been like to be on the outside of this story. After the big turning point in the upper room, however, it becomes very much an insider’s story — and one that assumes the audience’s familiarity with the back-story.... Instead of opening up the story to non-believers, it feels like the filmmakers are, by this point, ticking off a list of familiar stories that believers would want to see.

That said, there is still a lot to like about Risen. It’s an imaginative and reasonably grounded take on an old story, and it just might encourage people — both inside the church and out — to step outside their comfort zones a little and imagine how the world looks from the other side’s point of view. And that is no small thing.

Matt Zoller Seitz at RogerEbert.com agrees that Risen's first half works, but the second half "resorts to pictorial cliches you associate with kitschy religious art and lets its story devolve into a series of clunky set-pieces." But he finds plenty to admire:

Although the filmmaking in Risen isn't at the same high level as that of The Gospel According to St. Matthew," The Last Temptation of Christ and The Passion of the Christ, it's on the same creative wavelength. We're not hearing a genteel sermon delivered from the pulpit of in an air-conditioned megachurch, but the harsher phrasing of a street preacher.

Bilge Ebiri (at Vulture) writes:

While nobody will mistake [Kevin Reynolds] for Martin Scorsese, his films usually demonstrate a nice mix of atmosphere and grit. He tells mythic, heroic stories, but he usually finds convincing ways into them, placing us in these worlds.

That works well in Risen … until it doesn’t. As you might expect, the God stuff eventually becomes more pronounced. This is a film produced by Sony’s faith-based handle Affirm Films and aimed at the evangelical market, so we do get some (clunky) pyrotechnics and worshipful looks by the time it’s all over. But still, for a film that could have easily become bogged down in Sunday School reverence, or culture-war opportunism, Risen presents an intriguing, oblique approach to a Bible movie.

Also: Alissa Wilkinson interviewed Joseph Fiennes at Christianity Today.

And it's worth remembering: Brian Godawa described the movie as "a Christian apologist's wet dream." Huh. I've heard sermons that would incline me to believe that's a bad review.

Fujimura in Neverland

I am reading Refractions, a treasure trove of a book filled with meditations on art, faith, America, China, and the shadows of 9/11, written by the great visual artist and advocate for the arts Makoto Fujimura. And as I was reading this morning, I discovered that it contains a beautiful chapter about Marc Forster's film Finding Neverland.

Forster, as a director, has made some films I enjoy and admire (Stranger Than Fiction, World War Z), some that leave me with mixed feelings (World War Z, Monster's Ball, The Kite Runner), and a few that I don't care to ever see again (Machine Gun Preacher, Quantum of Solace).

I've always had a soft spot in my heart for Finding Neverland, but my own review became an exhibition of my weaker tendencies as a reviewer: I wrote with haste and redundancy, and I was annoyingly long-winded.

I've always had a soft spot in my heart for Finding Neverland, but my own review became an exhibition of my weaker tendencies as a reviewer: I wrote with haste and redundancy, and I was annoyingly long-winded.

So I was delighted to find this gem of a review, which I'm featuring as the second review in my "Looking Closer Exemplars" series, reviews that I would hold up to students as excellent examples of what film reviews can do and be. Fujimura doesn't demonstrate any compulsion to write all of his thoughts on the film. He doesn't make sweeping declarations as if he is the Authority on the subject. He mediates on the film's virtues, offers a few prompts toward a critical appreciation, and then shares personal insights about how the film speaks about, and into, our own experiences. Rather than telling me what to see, he makes me want to see.

It's a lovely review, a model to keep in mind for people who write about film, and — thank goodness — it's online so everyone can read it.

Observing Lent with Lucinda Williams

You’ve probably heard that if you listen to Pink Floyd’s The Dark Side of the Moon while watching The Wizard of Oz, it’ll seem like they were meant to go together. Their profound synchronicity just seems too specific to be coincidental.

That’s how I felt a couple of weeks ago when some of my coworkers walked across the street for Seattle Pacific University’s Ash Wednesday service while I, behind schedule on several project deadlines, had to stay at my desk. As I worked, I wondered—as many Christians do during the 40 days before Easter—what exactly it would mean if I had gone with them: Would I have been merely reacting to a social media prompt out of a sense of peer-pressure obligation? Or would I have been capable of opening a place in my heart for meditation on Christ’s sufferings, for practicing reliance on God’s provision?

I didn’t have time to think it over, though. The clock was ticking. So I put on my headphones (music helps me focus) and pressed “play” on Lucinda Williams’ new double album The Ghosts of Highway 20, which had just arrived in my mailbox from Amazon.

I didn’t have time to think it over, though. The clock was ticking. So I put on my headphones (music helps me focus) and pressed “play” on Lucinda Williams’ new double album The Ghosts of Highway 20, which had just arrived in my mailbox from Amazon.

Whoa.

These songs—they work as perfectly for an Ash Wednesday liturgy as Pink Floyd serves as a soundtrack for the Yellow Brick Road. While my friends had gone to the sanctuary, I went to church with Lucinda Williams.

•

That's how my new installment of "Listening Closer" begins over at Christ and Pop Culture. Want to read the rest of it?

The day I met Alejandro González Iñárritu

It was almost ten years ago now that I sat down to talk with Alejandro González Iñárritu about his first Best Picture nomination: a film called Babel, which I found challenging, ambitious, and complex. To date, it's the only one of his films I enjoy.

Last night, when Iñárritu won the Academy Award for Best Director for the second year in a row, I was aggravated. I would have chosen differently. I think his recent films have been a case of sound and fury signifying, well... almost nothing.

Last night, when Iñárritu won the Academy Award for Best Director for the second year in a row, I was aggravated. I would have chosen differently. I think his recent films have been a case of sound and fury signifying, well... almost nothing.

But when I rediscovered my interview with him from 2006, I found it easier to let my typical sense of Oscar frustration go. Iñárritu is a man of deep convictions, some of which have grown in the rich soil of his Catholic upbringing. They may not make for very meaningful art, but I appreciate some of his views.

In that conversation, which you can read in its entirety here, he spoke about his love for his family, his Catholic background, and his desire to make art in "uncomfortable" territory. He said:

For me, Babel is about human beings left alone with each other. There's an absence of God. In a way, we have been dealing with the consequences of our own greed, our own selfishness. We punish ourselves with the way we act [toward each other.]

God made very clear what we need to do. And we are the ones that haven't followed those rules. We always complain and get angry at institutions and religions. But it is not religion or institutions—it is us. The problem is us. We destroy everything that we touch. We destroy marriages, parent-child relationships, governments. Before, it was the monarchy that failed. Then, the czars failed. Then, communism failed. Globalization and capitalism are failing. There's corruption in every institution. It is not the fault of God. It is us. This film clearly shows that man is trying to survive, lonely, without God.

I remember enjoying our conversation. And while Birdman and The Revenant — his Best Picture-winning films — are both, for me, more frustrating than rewarding, I'm still interested in this guy's imagination and ambition. It'll be interesting to see what he does next.

Which is your favorite of Iñárritu's films? And what do you admire about it?