Simon says

Until its release next week, you can stream the new Paul Simon album Stranger to Stranger at NPR's First Listen, and it is well worth a listen.

Simon's been hinting that he might take a long hiatus from songwriting, and I hope that isn't the case... especially in a year of sudden, unexpected, and devastating losses to the music world. But if, God forbid, this would turn out to be his last album, I can't imagine a more perfect finale than the song "Proof of Life," which plays late in this fleeting (37 minutes!) set.

In August, we'll celebrate the 30-year anniversary of Graceland. I can only hope that I'm still growing, learning, and burning with the intensity of creativity that I hear on Stranger to Stranger when I'm Paul Simon's age. This album is ablaze with wisdom, humility, and faith.

Bob Dylan — from faith to faith

Right before I turned out the lights last night, I realized that I hadn't acknowledged a very important birthday. So I opened Facebook to make a few quick notes.

Well, I wrote a lot more than a few quick notes. There's no way to be concise about a living legend.

In the end, what I wrote is blog-post-sized, much more than a Facebook status update. So I'm sharing it here today. After all, nobody's stopping me from celebrating Bob Dylan all week long.

•

I can't let the day come to an end without acknowledging the 75th birthday of one of the most influential human beings in my life.

Bob Dylan — a poet who followed the truth until he recognized that the truth was Jesus, and then, instead of building an altar there at that spot of revelation, he followed Christ from straightforward Gospel songs out into a wider world of subjects, and beyond any familiar vocabulary.

As he ventured so much more deeply "further up and further in" to the mysteries of the Incarnation, his own evangelical fans, for the most part, became alarmed that they no longer recognized his vocabulary and branded him a "backslider" and a "disappointment." After all, once you're a Christian, shouldn't you just stay in church where it's safe, singing songs loaded with Biblical references, or else launch an evangelical movement of some kind?

(I've even heard people say that his salvation must never have been genuine in the first place — a judgment so presumptuous that it seems to trespass into territory that the Scriptures say belongs to God alone.)

I'm with those who think that the Gospel enhanced Dylan's already formidable powers of perception and poetry, and that the truth set him free to explore even more bravely, honestly, and insightfully through territories far beyond the comfort zones of those who would prefer that faith remain safe and familiar.

Listen to Oh Mercy or, even though some Dylan fans will cringe at the thought, Under a Red Sky.

Listen to Time Out of Mind and Love and Theft.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EfP52-SPNdY

These records are rife with allusions, parables, psalms, and proverbs. They lead Dylan all the way back to classics of the American songbook, and as he sings those familiar tunes in the context of his vast exploration, he finds threads within them that suggest they were sacred music all along.

God bless you, Robert Alan Zimmerman. "You gotta serve somebody" — indeed! And it sure seems to me that you serve the Way, the Truth, and the Life. Keep your heart in the highlands... you wild man, you voice crying in the wilderness.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5lDTyffguGw

And in your honor, I amplify these words from Thomas Merton:

"…if revelation is regarded simply as a system of truths about God and an explanation of how the universe came into existence, what will eventually happen to it, what is the purpose of Christian life, what are its moral norms, what will be the rewards of the virtuous, and so on, then Christianity is in effect reduced to a world view, at times a religious philosophy and little more, sustained by a more or less elaborate cult, by a moral discipline and a strict code of law. ‘Experience’ of the inner meaning of Christian revelation will necessarily be distorted and diminished in such a theological setting. What will such experience be? Not so much a living theological experience of the presence of God in the world and in mankind through the mystery of Christ, but rather a sense of security in one’s own correctness: a feeling of confidence that one has been saved, a confidence which is based on the reflex awareness that one holds the correct view of the creation and purpose of the world and that one’s behavior is of a kind to be rewarded in the next life. Or, perhaps, since few can attain this level of self-assurance, then the Christian experience becomes one of anxious hope — a struggle with occasional doubt of the 'right answers,' a painful and constant effort to meet the severe demands of morality and law, and a somewhat desperate recourse to the sacraments which are there to help the weak who must constantly fall and rise again. This of course is a sadly deficient account of true Christian experience, based on a distortion of the true import of Christian revelation."

Listen. Do you hear it? It's not dark yet, but that slow train's still comin'...

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mns9VeRguys

Last Days in the Desert (2016)

What do you call the sufferings of a man who forces his family to live with him in a remote, desolate location because Jerusalem is corrupt?

"Just deserts."

Okay, forgive me for that.

Last Days in the Desert, from director Rodrigo Garcia, brings a wandering, troubled, and all-caps HUMAN version of Jesus, played by Ewan McGregor, into contact with just such a fellow — a stubborn recluse (Ciarán Hinds) who wants his wife and son to remain with him in the middle of nowhere in order to escape the distractions of city life. Jesus, reluctant to keep company with the family, is ultimately drawn to the frustrations of a beleaguered and increasingly resentful son (Tye Sheridan of The Tree of Life and Mud), and camps out with this family to see what he can do about the boy's angst and, eventually, the sufferings of a dying mother (Ayelet Zurer).

Directed with admirable patience, spaciousness, and contemplative inclinations by Garcia, and lensed by the masterful Emanuel Lubezki (The Revenant, The Tree of Life, Children of Men), Last Days in the Desert achieves something that very few Jesus films have achieved: Strangeness. That's about the highest compliment that I can give this crew. They made a movie in which I wasn't so distracted by the film's faithfulness, or unfaithfulness, to the Scriptures because I was so captivated by the narrative's unpredictability. I never knew what was coming next, and so my brain stayed busy throughout — a rare pleasure. When we finally arrive at images of the crucifixion, even those were unexpected.

What's more — I rarely believe any movie about Jesus, even for a moment, because I rarely see a Jesus who might be something more human than a piece of stained glass. This Jesus is extremely physical, extremely accessible. It's easy to relate to him. In fact, it's so easy to relate to him that I think the Jesus Movie pendulum might be swinging too far to the opposite extreme — but I'll get back to that later.

McGregor gives a surprisingly complicated performance as both Christ and "the Demon." His Devil is wonderfully unstable — leering and sneering one minute, blinking blankly the next, and sometimes stumbling into moments of profound loneliness.

But the more we watch this Jesus's angst, the more I begin to suspect that McGregor is struggling as much as I am to figure out what this script is really about. (The answers McGregor gives in the "special presentation's" closing interview about his attempt to connect with something more... yeah, that's how I felt too.) Even Lubezki seems unclear about what's expected of him; his imagery is attractive but it rarely ever suggests anything. It's like Garcia watched The Last Temptation of Christ, got excited about the early scenes in which Jesus seems rather lost and confused in a maze of his own "Daddy issues," and decided to make a whole movie about that without any special insight.

The father/son themes are primal enough to resonate with some moviegoers, I'm sure. (And I like Stephen Holden's note: "Make what you will of the fact that Mr. García is the elder of two sons of a literary god, the Colombian author, Gabriel García Márquez.")

But even though I appreciate ambiguity and spaciousness in art, I just never felt these plot points, conversations, or images achieving any kind of poetry. It's so spacious, so spare, I imagine folks can, and will, imagine all kinds of things it might mean.

(Disclaimer: My suspension of disbelief and my ability to appreciate the film were dealt a profound blow by the "special presentation" introduction, in which two young men — who are apparently recognizable figures to consumers of Christian pop culture — gush superlatives for this film in a way that tells me they don't watch that many art films. I immediately distrusted their judgment, and my feelings about having purchased a ticket worsened when I learned we'd have an unwanted and unremarkable praise song foisted upon us before the movie. By adding more, they made the experience of the movie something less.)

I might even have enjoyed the film more without Garcia's last act jump to the crucifixion, which feels obligatory and uninspired. It distracted me, asking me to find some connection between what Garcia imagines might have occurred in the desert and what Jesus ends up willingly suffering. I wanted to gain some insight into how the film's surprising central narrative informed Jesus's subsequent ministry, but the film's two jarring last-act leaps forward in time left me flailing for any rewarding interpretation.

Am I to conclude that since Jesus encouraged a troubled son to remain faithful to a difficult father that he was empowered to do so himself? Am I to assume that, watching a man risk his life to obtain something valuable for his family, Jesus found the will to put his own life on the line? Or is it that Jesus is so distraught by death's hold on this poor family that he feels compelled to break the Devil's power? Your guess is as good as mine.

Whatever the case, the film gives us no reason to believe that this Jesus is capable of anything miraculous at all. Sure, the Devil mocks him for holding back, but that's not enough. McGregor's Messiah is so human that he scolds himself for not having better advice for the struggling family, and exhorts himself with a variation on that famously fictional Francis of Assisi quote: "Preach the Gospel at all times and when necessary use words." Any supernatural activity — levitation, for example — occurs only in Jesus's dreams, unless you count his arguments with the Demon, who we're led to believe might just be some kind of Fight Club alter ego, or an earthbound "shadow" to Jesus's soaring bird.

Frankly, McGregor's Jesus didn't really have to be Jesus at all — he might have just been a "holy man." Garcia seems to hold fast to that possibility as if to make sure not to alienate those in the audience who aren't Christians. Jesus becomes an everyman: a guy just trying to figure out what a stubbornly silent God wants from him, and — get this — a fellow prone to falling for Satan's simple tricks, like impersonating a dying woman and rasping deathbed lies about her husband's unfaithfulness. (In one scene, Jesus actually asks the Devil to show him the boy's future in something like the Mirror of Galadriel — and the scene feels an awful lot like Jesus succumbing to temptation and asking for the Devil's help. Even stranger, we're supposed to believe that the future the Devil shows Jesus is true.)

These fanciful departures from the familiar plot aren't wrong for an artist to imagine — sometimes, distortions of convention result in surprisingly rewarding discoveries that help us see the familiar with new appreciation. (See The Last Temptation of Christ.) But they sure don't align with anything in the gospels' mentions of the young Jesus, who was so confident that he amazed people with his teachings in the temple. The farther Last Days goes, the less I find myself capable of imagining that this story is anything but Jesus Fan Fiction from a fan somewhat unfamiliar with the source material.

Oh, how I hate to share these misgivings about Last Days. I'd love nothing more than to see more challenging interpretations of the Gospel on the big screen than the "Christian movie industry" has provided so far. And this certainly qualifies. But the real challenge for any Jesus-movie filmmaker is in presenting a Christ who is both persuasively human and unnervingly divine. We've had far too many who adhere to the American Evangelical stereotype of the supremely confident, off-puttingly nice, white-skinned and blue-eyed magician Jesus — the one who grants wishes, and whose enemies make us think of supervillains instead of ourselves. We've had only a few striking depictions of God's only son that show us a human being who wrestles with temptation and struggles to stay warm at night.

I'm hard-pressed to think of an actor who who strikes the right balance better than Willem Dafoe in The Last Temptation of Christ. It's a flawed film, sure, but Dafoe's version of the Christ occasionally, in his humanity and his strangeness, gives me that unsettling sense that, yes, Jesus must have been something like this. Even as evangelicals went into a panic about how Martin Scorsese's controversial film "blasphemed" the Son of God, I quietly found my faith growing stronger as I watched it.

If Last Days strengthens my faith in anything, it's in McGregor's abilities as a leading man. His villain is an especially compelling creation, delightfully surprising in his complexity, startling in his humor, and recognizably human in his loneliness. Viewers might find him just pathetic enough to kindle some sympathy for the devil.

[This review is brought to you by the Looking Closer Specialists,

who have been generous enough to support my work

during a season when I'm short on time and resources.]

The Jungle Book (2016)

[This post was originally titled "A Mowgli I Can Believe In."]

•

For the first time in my experience with The Jungle Book — an experience that includes growing up with the 1967 animated Disney film, knowing all the words to all of the songs, and then being surprised by the strangeness of Rudyard Kipling's original story sometime in my teens — I care about Mowgli.

I have director Jon Favreau and screenwriter Justin Marks to thank for that. In Disney's "remake," a sumptuous and CGI-saturated Jungle Book, they have liberated the story's central character from his lack of character and given him some real energy, some real heroism, some real... "red flower," if you will.

Mowgli has always been what I call a "pinball character." The story launches him out of his proper place through some spring-loaded calamity, and the unfolding narrative is just a matter of watching him bounce, careen, and roll from one unlikely character or environment into another until he finally settles, seemingly inevitably, back in human society where he belongs.

And, as with most pinball machines, the ball is the least-interesting part of the machine: it's what the ball hits that lights up and makes exciting noise. The fun in The Jungle Book has always come from the various wild-animal candidates who befriend him (Bagheera the panther, voiced modestly here by Ben Kingsley), mooch off of him (Baloo the Bear, voiced appropriately by Bill Murray), want to eat him (Kaa, sensuously hissed by Ssscarlett Johanssssssssson), and want to tear him limb from limb (Shere Khan the Tiger, a seething Idris Elba).

This Mowgli — well, first of all, to borrow a line from Pinocchio, he's a "real boy." And I don't just mean he's played by a human (although the young and spry Neel Sethi is a brilliant surprise, looking more like someone we'd see in a classic by Satyajit Ray than any live-action Disney film). This Mowgli is a three-dimensional character even if you watch the film in 2D (like I did). He's quick, clever, expressive, and, in the film's most surprisingly affecting scene, courageously compassionate.

And yet, we still haven't arrived at the reason why I suddenly find myself caring about him. I like this Mowgli because he has some credible reservations about his panther guardian's intent to reunite him with human society.

As a boy who grew up sustaining some serious aversions to the unimaginative, over-serious, and off-puttingly contentious world of adults, I feel a deep ache of empathy when this "man cub" comes within site of a village and feels repelled by the sense of violence and arrogance that radiates from the lights of its fires. I won't get too spoiler-ish here, but suffice it to say that, while it has some moviegoers scratching their heads, the conclusion of this version feels just right to me. I'm still trying to make my peace with my own species. I'm still trying to figure out how to stay alive without playing "dirty human tricks." Humankind isn't inclined to support or respect those who desire to live by compassionate creativity rather than by competition and power games.

Now, I know that's a harsh generalization. But it's a good one, in my experience. There's already talk of a sequel, and I sincerely hope that we see a more nuanced picture of human society there. But the quick glimpses we get here rang dismayingly true.

Having said that... this film is a mixed bag of good news and bad news.

The bad news? The end-credits sequence — a fantastic innovation on the Disney tradition of beginning and ending their movies with the opening and closing of a storybook — is the most brilliant thing in the entire film. I won't describe it, because it's such an imaginative surprise. But I didn't want that playful onscreen party to end.

The good news? The feature film that precedes that dazzling display is just about as good as anything Favreau has given us. It's particularly valuable because it's a film I can heartily recommend for all but very young (or very sensitive) children. (There's a tiger, you see, and he's very, very scary.)

I had to fight hard to approach this film with an open mind. I'm not crazy about Disney's compulsion to cash in on elaborate "live-action" (read 90% CGI, 10% actual footage) remakes of their animated classics. And as a huge fan of Bill Peet, a brilliant author and illustrator of children's books who was influential in the design of the original, I prefer its visual style. I can't say that I think Tim Burton's Alice in Wonderland has made the world a better place, and I haven't heard anything about Cinderella that made me want to see it in the theater.

But Favreau's Jungle Book manages to avoid all kinds of typical stumbles. It doesn't treat the kids in the audience like second-rate intellects, and it doesn't swing too far in the directions of Cute or Crass. If you're looking for a faithful adaptation of Kipling though... well, you'd do better to adjust your expectations than avoid the film. This is about as true to the literature as Children of Men was to the P.D. James source (that is to say, hardly at all). But the screenplay by Justin Marks is a good one (he's the guy writing Top Gun 2, of all things); it gives families a story that defines true humanity as living in friendship, compassion, courage, humility, creativity, and conscience. The storytellers take some admirable risks — especially in their development of Mowgli's character into a conscientious, large-hearted, non-violent hero.

As a high-adventure story inspired by (but not really based on) Kipling... it's "just so."

•

It's a busy week, as I'm deep into planning my upcoming course on film, the visual arts, and apologetics. So I'm going to hand the rest of this post over to the Looking Closer Specialists — readers who have shown remarkable support for this website, helping me keep it alive.

•

So, as with Cinderella and Alice in Wonderland,

here we have another extravagant "live action" remake

of a Disney animated classic. Are you glad they went to the trouble?

Are kids and families better off for having two versions?

Chris Angus:

I think where the first film excelled was with the hand-drawn character animation and how those cartoon characters were interacting. In those regards Disney was at the top of their game. If I remember right they intentionally placed the characters over the story, compared to their other films at the time.

The first version was a quirky and fun look at relationships. This version is a large, sweeping, and majestic adventure. They have different scopes and I appreciated them for different reasons. I loved the beasts that were created in this version and how they interacted with each other and the boy. I also enjoyed the scenery.

Joshua Wilson:

Yes. I haven't seen the animated version in a long time, but I feel that this one is superior. The animated film is a minor work in the Disney canon.

Carl-Eric Tangen:

I had fun watching it as an adult, but largely because I had a frame of reference from my childhood. It was interesting that Favreau said he did not set out to do a "faithful" remake, but rather one that was faithful to his impression of the original film as a kid.

My apocryphal paraphrase: So, when Favreau got the job, he tried to recall and write down everything he remembered about the movie and how it made him feel as a kid, etc. He tried to use that as a starting point for how to approach the film before revisiting the original for the first time in 30 years. So you have the terror of King Louie, for instance, who is basically King Kong, coming from an adult who is trying to translate his childhood thrill into a new experience that makes sense to him today. Interesting, at the very least.

Levi Douma:

I think this movie has a lot of good ideas, but they don't work together well. The more serious tone and the songs, the animation and the live-action — all feel as if created by different departments. The story really is the best thing, but the movie as a whole feels crippled by the familiar elements they have to put in. So maybe the form "live-action remake" is to blame and we should not have any more of them.

•

Is there a value to a lavish CGI Jungle Book that

the hand-drawn animation version doesn't have?

Or does this version just increase your appreciation for the original?

Angus:

I prefer hand-drawn animation but I also appreciated the characters in this film, and I enjoyed some of the lavish backdrops. I think the two films can sit side by side. Time will tell if this film becomes the classic that the earlier film has. I suspect it won't. Actually I would be surprised it it did.

I generally prefer 2D animation over 3D when it comes to fully cartoonish characters, but these characters sat somewhere between cartoon and real life in the vision of them. So I thought 3D fit them fine. I really liked the design of these characters. The tiger was wonderfully sinister in both his design and actions. I thought he was a great character.

Douma:

The CGI style is too "realistic" and serious. Even though the animals behave like humans in a way, in this movie they look 100% like real animals. That is different from other Disney movies where the animals not only behave like humans but also look human in a way. But this was necessary of course because of the physical presence of the young actor who played Mowgli. I think the hand-drawn version has more freedom. The seriousness of the very realistic CGI does not match up with the playful musical style the filmmakers want to recreate.

Wilson:

I love hand-drawn animation dearly, but this movie was a great venue for the chosen treatment. The transition to the dry season sequence was a beautiful example of what can be accomplished through this style.

•

How do you feel about the way they

worked the original songs into the film?

Did it work?

Angus

"I Wanna Be Like You" fell completely flat. It didn't work at all. "The Bear Necessities" was completely fun. I loved how the boy was diggin' right into it. That was one of my favorite moments with him.

Douma:

I agree with Chris Angus, "The Bear Necessities" was fun, but King Louie (the monkey) sang a happy jazzy song while he was covered in dark shadows.

Wilson:

I agree with the other responses. "Bear Necessities" fit better than "I Wanna Be Like You." They should have left that for the charming end credits. It became redundant at the end because of the repetition, rather than a fun surprise. It undermined the mafia-boss/Colonel Kurtz scariness of the moment, but that may have been intentional.

Tangen:

I don't think they needed to work in the music nearly as much as they did. I had mixed feelings about the King Louie song — it was both surprising and jarring and scary (good things, in my humble opinion), but it also reminded me of the little Goblin Town revue in Jackson's The Hobbit. But perhaps, more than anything, it brought up the realization of how rare and odd it is for us to encounter songs in films today. It used to just be common practice, even Hitchcock did it once or twice.

•

What is this story really about?

Without going into specific spoiler territory,

what do you glean from this narrative?

Is Mowgli a hero, and if so, why?

Douma:

It's about being yourself and to be able to express that. What the movie seems to add to this is that it totally doesn't matter if your environment is not compatible with your personality or skills and that your talent will still benefit you and them. I am very curious about what everyone thought about the ending compared to the ending of the original.

Angus:

This story isn't just about the boy. It's also about the animal kingdom that interacts with the body, defending him, or against him. The film is about the animal kingdom and how the boy does or doesn't fit within it. It shows respect for the animal kingdom but also has an element of "human exceptionalism." The boy can make fire. He has his "tricks."

I would think that this film shows more of a Biblical view on the idea that humans are expectional, being made in the image of God, even while the animal kingdom has immense value.

Wilson:

This Jungle Book conveys the idea that "man" is responsible for taking care of the natural world, for sure. But I also got some hints of the notion that human interaction with nature has the potential for elevating and ennobling it.

Baloo, for selfish reasons, is the first to see the benefits to the animals in allowing Mowgli to use his "tricks," the animal name for the tools he creates. Bagheera and the others come around, mainly due to his interactions with the elephants. The elephants are treated with a quasi-religious reverence. Mowgli treats them with respect, but is not afraid to direct them.

Mowgli is a hero in the story, but he is still a child. The story wants us to see that we humans can learn from nature, even if we are its master by means of our technology. That's why a child is the protagonist: he has to still be in the position of a learner, and be inexperienced. Kaa and King Louie have to be extremely large, though, so that we the viewers will see their exotic and frightening power like Mowgli does. The giant bonfire in the town is similarly outsized.

What's the best reason to see it?

Or, if you're thinking it's best avoided,

what's the best reason for that?

Angus:

The best reason to see it is because it sent what is left of my inner child on an adventure that wasn't found in the earlier film. The earlier film had other attributes that this one didn't have though. It was much more magical in how it dealt with the relationships between the child and the animals.

Douma:

The best reason to see it is because of its messages about conformity and self-expression or "being yourself," even though the bold statement the ending seems to make in comparison to the plot of the original Jungle Book confused me.

Wilson:

The best reason to avoid it in theaters has to be the almost half hour of dreary to execrable trailers for family "entertainment" that I had to sit through.

Bono. Eugene. The Psalms.

This post has been amended for the sake of clarification. If you read Version One and were offended, I ask you to read Version Two closely. Thank you!

•

Eugene Peterson, author of The Pastor and sometimes-celebrated/sometimes-criticized translator of The Message, is — in my humble opinion — a national treasure.

I may not always prefer his translation of Biblical passages over other translations, but I am grateful for The Message in how it serves as one powerful lens in a useful array of lenses on the original Greek and Hebrew texts.

And I am just as grateful, if not more so, for Peterson's series of theological meditations that include Christ Plays in Ten Thousand Places and Eat This Book. From his lakeside perch at Flathead Lake, Montana, Peterson has contemplated and written about the scriptures and the Christian life as profoundly as any contemporary Christian writer I have encountered.

Full disclosure: I've had the unlikely privilege of getting to know him as a friend and as a counselor over the last decade through our mutual membership in a writers group called The Chrysostom Society and through Peterson's occasional participation in The Glen Workshop. So I'm more than a little biased. He is as humble, as generous, and as large-hearted as you might have heard. And his smile is as explosively joyous as any I've seen.

So it is a joy to see his work celebrated in any fashion. I was particularly pleased to see him receive the Denise Levertov Award from Image, an award that acknowledges distinct and substantial contributions to conversations about faith and art.

And here is Peterson again, receiving a glowing tribute from Fuller Studio by way of a personal endorsement from by a man who is both the biggest name in rock music and the biggest name in evangelical pop-culture cred.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-l40S5e90KY

Filmed by my friend Nathan Clarke (director of an excellent documentary called Wrestling for Jesus), and hosted by Fuller seminary faculty member David Taylor (editor of For the Beauty of the Church), this short video chronicles a visit by the U2 front man to Eugene Peterson's Flathead Lake home for a conversation about the Psalms.

The film gives admirable attention to the context of their conversation, a place so beautiful it practically shouts out echoes of the Psalms. (Flathead Lake is where I was hiking when I got the inspiration for my own four-book fantasy series, stories that gave me a way to explore how the created world and our own creativity do a redemptive work in the world. "What a spot!" — indeed.)

There was so much buzz about this video before its release that I found myself anticipating a monumental conversation about the Psalms. As it turns out, the video scratches the surfaces of some really intriguing questions. But it still plays only like a trailer for the conversation that the teaser made me hope for. Each little chapter of this 20 minute video feels like an advertisement for a larger, more adventurous work.

Amendment #1: One of the filmmakers tells me that the actual event captured and shared here took very little time at all, and that part of the contract involved limiting the video to this short span of time. Fair enough. That doesn't mean my expectations should have been different — the teaser didn't tell us it would be such a brief conversation. But it's good to know that they've given us what they could.

Even though it's a short video, I kind of wish that the project either bore a different title (one that kept me from expecting that the film's primary focus would be The Psalms) or had been split into two parts: An introduction, which would have been about how the rock star and the pastor came to be friends; and then a second video, which would have documented this fleeting chat about the the Psalms. As it is, it feels about 50/50... part fanboy event (a meeting of good friends captured on film so their fans can savor the sight of it — something that I admit I enjoy), and then an earnest but fleeting consideration of the Scriptures.

Don't get me wrong — the story of the famously self-effacing megalomaniac "opera singer" and the quiet whisper-voiced Protestant minister is one worth telling. I remember how my heart rate accelerated when Jan and Eugene first showed me snapshots of their startling first encounters with Bono, and laughed about how they had initially ignored Bono's phone calls because they didn't know who he was. I think it's fantastic that Peterson's quiet, humble, disciplined work has blessed Bono and influenced the lyrics of the world's biggest rock band. And so I'm relieved that this Fuller Studio video plays more as a tribute to Peterson's meditative interpretations of the Scriptures than as yet another Christian pop culture artifact laying claim to Bono as "one of us."

And, frankly, I like this video as much for its acknowledgement of Jan Peterson's gift of hospitality as for anything else. I'd have put Jan's name in the title alongside Eugene's. Jan is a glorious human being, a model of generosity. Eugene's work would not be what it is without Jan's tremendous love and care. You get a sense of that here.

•

Having said that, I do love what they say here, however briefly, about the Psalms.

It was only recently that I overcame many years of troubled feelings about the Psalms and their evident call for violent judgment, for their often searing displays of rage and desire for destruction. It just seemed so contrary to the spirit of Christ. But a prison chaplain — Chris Hoke, author of an excellent new memoir called Wanted — recently got me thinking about how the Psalms are not meant to be an endorsement of asking God to kill our enemies, but as a demonstration that God can take and hold all of our flawed expressions, all of our volatile emotions. We are invited to vent, to rant, to express the full truth of our imperfect thoughts and emotions in the presence of God's grace and affection.

And then what happens? How does God respond to those impassioned and temperamental poems and prayers? God answers our complicated and somewhat corrupt prayers with an answer: Christ himself, who shows that the only way to overcome the sins of our enemies is to receive them without retaliation, to save the world from sins by absorbing them without perpetuating them.

Christ, as Peterson acknowledges in this video, responds to violence with love, saving the world. The Psalms are not complete without God's response to them. We need to see the whole picture. If anybody holds up David's appeals for God to smash his enemies to a bloody pulp and says, "See? This is what God wants!" ... they are doing harm to the full purpose and glory of the Scriptures.

Insofar as this video reminds us of this, I am deeply grateful for it.

•

The easy thing to do would be to stop there — to just pile on, to gush with love for two amazing guys and a video that honors them.

But Bono says right here in the video that he wants Christians to be more honest about the good things and the difficult things. So here goes:

I just can't shake the discomforting sense that the larger-than-lifeness of these personalities will, for some, distract from the subject at hand. I wish that there could have been more attention given to the Psalms themselves, in proportion to the super-coolness of this meeting.

Amendment #2: Okay, so the actual conversation had strict time limits that prevented this from being a monumental theological discussion. I understand that. But still, since that information is not given to us in the video...

I'd rather have a window on this brief conversation than not, so I'm content to be grateful for what we've been given. But I must admit that in a 20-minute video called "The Psalms," it's a little disappointing that we don't get to the Psalms at all until almost halfway through the production.

•

And there's another thing — something that isn't the fault of the filmmakers or anyone involved, but that I should admit I experience as I watch this video.

As the credits for this video roll... and roll... I cannot help but feel a familiar struggle rising in my heart and my gut.

Amendment #3: What do these lists of names represent? I matter-of-factly concluded that this was a very expensive production, and that these credits represented support of some material means, financial or otherwise. I've been informed that the list is long because David Taylor is graciously thanking friends who offered all kinds of support, including friendship and prayer. So, while my assumption comes from a lifetime of reading end credits lists and watching for the list of donors, movers, and shakers, I was in error in thinking that these organizations actually funded the production.

Amendment #4: What follows here has been described as a "stab" or an "attack" on the people who supported this video. I ask you to please read it carefully and observe that I clearly state otherwise.

Forgive me, friends who worked on this video — I don't mean to condemn the effort at all. I only mean to voice, in honesty, a conflict that I feel as I watch it.

Any event like this is necessarily complicated because of the reality of celebrity. And when I see so many Christian organizations rallying around this event, responding with enthusiasm to the opportunity to highlight cultural celebrities talking about the Scriptures, it makes me wish for a similar collaborative enthusiasm on projects that aren't about big names.

Bono and Eugene Peterson are both giants on the world stage because of the quality of their work, sure, but also because the enthusiastic responses to their work generate a kind of ripple effect, a glamour, a desire to be close to those who are so popular and beloved. I feel this difficulty even in this blog post, when I mention my personal connection to Peterson: Why do I mention that? To bring some credibility to my claims? To impress people that I know Eugene Peterson? It's a difficult issue, and I'm sure that I am sometimes guilty of name-dropping for the hope of gaining some kind of admiration from the association with a famous person. What an absurd thing to do.

(More than one person has noted, with the arrival of this video, that I myself am now only "one degree of separation from Bono... through multiple people!" Whatever. If I let myself get excited about that, what does it say about me and how I measure the value of my relationships?)

I'm not accusing anybody involved with the video of being celebrity-obsessed. I'm just acknowledging that it is a complicated thing.

And that complication makes me somewhat suspicious whenever I see long lists of organizations and people "supporting" a production involving celebrities. I'm sure many of them were totally sincere and innocent in doing so — whether donating or offering moral support or praying. That's great.

But wouldn't it be even more inspiring to see a collaboration of Christian arts organizations like this for something that isn't guaranteed to draw a million eyeballs with the gravitational pull of celebrity?

What about all of those Christians in the arts who are doing honest work, and who, given collaborative support like this, might surprise Bono with exactly what he seems to think is missing?

When I hear Bono talking in this video about how "suspicious" he is of Christians in the arts, I get what he's saying — there is a lot that passes as "Christian music" that is really just crowd-pleasing mediocrity, wish-fulfillment choruses, the musical equivalent of aromatherapy. But there is a whole world of music out there being made by Christians that is at least as substantial, honest, raw, and complex as anything U2 has recorded. Why does Bono seem so ignorant of that? Part of the answer has to do with an unwillingness among many Christian organizations to support art that takes risks, that acknowledges ambiguity and doubt and trouble.

If a lightning bolt of luck were to catapult any one of the profoundly talented artists I know to global success like Bono's, Christian organizations would rally to associate themselves with that artist. But how many are brave enough and generous enough to be there at the critical stages of formation, willing to participate in the unglamorous planting as well as the joy of the harvest? I know so many whose art has received worldwide acclaim, but because of the lack of material support from those who have the resources to make a difference, they've had to surrender their work for the sake of making a living, and have faded into cultural obscurity.

Personally, I'm more moved when I see shows of support for artists at the ground level, support for the hard work of manifesting beauty and truth when there is no glamorous name or brush with celebrity involved.

I can think of several organizations — Image, for example: a community devoted to the cultivation of beauty and art and to supporting artists of faith, one that has to struggle to meets its costs week to week, that relies on a trickle of donations to survive — that commit themselves on a daily basis to the cultivation of great art rather than chasing the Big Names.

I can think of others too — I see some of them in the end credits here.

Amendment #5: I repeat, I'm not pointing an accusing finger at anybody listed in the credits of this video. Some of those people really do devote themselves to the cultivation of great art.

I realize that this sounds like a cynical conclusion to a YouTube event that does, in fact, glorify the Scriptures and celebrate two — no, more than that! — humble servants of God.

I realize that it could sound like a criticism of those who made this video.

And one more time with feeling: That's not what I'm saying. I'm glad this video exists, and I'm happy to see several friends of mine doing good work to bring it about.

I just want to see this collaborative spirit of support lasting longer than this visit from the rock star to the pastor. Here's hoping that it does.

No hard feelings, folks. But it's worth talking about.

Midnight Special (2016)

"You still haven't reviewed Midnight Special. Why not?"

Who's asking?

"Call me... Amalgam."

That's not a name.

"It's my name. I'm the amalgam of the moviegoers who have asked you about Midnight Special. And I'm losing my patience with you. This was, for many film lovers, the most anticipated film of season, if not the year. And you saw it on opening day. And now it's gone from theaters, and you still haven't reviewed it."

I was busy. Busy finishing graduate school. Then busy being sick for several days. Then busy dealing with unforeseen troubles at — wait, why am I explaining myself to you? It's a movie.

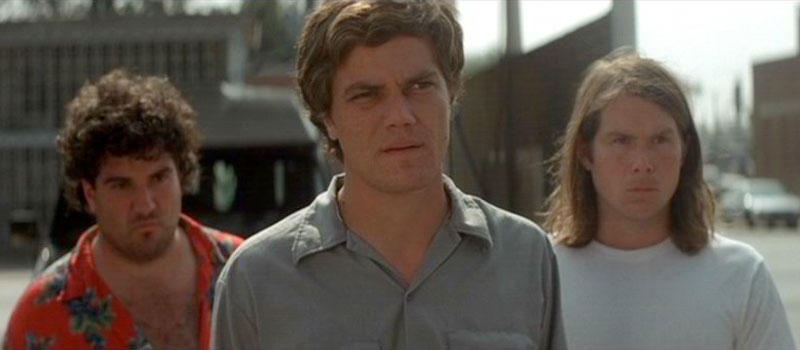

"It's not just any movie. It's from one of the most compelling young directors working today: Jeff Nichols. You talked up his first movie like it was a major event. And now, among cinephiles, you hear the name Jeff Nichols everywhere as a talent outshining one of his own accomplished indie mentors — David Gordon Green."

Why are so many critics treating Nichols as some exciting new director, highlighting how talented he is for somebody so young? It's been almost ten years since Shotgun Stories. Which is, by the way, still his best film.

"Come on. Take Shelter is his best film. It's so much more confident, so much more... cinematic."

Take Shelter is really good. I don't mind anybody picking it as their favorite. It just isn't as satisfying overall for me. While I really like the ending, the movie feels about 15 minutes too long. Shotgun Stories doesn't overstay its welcome. It's a perfectly measured story, totally suspenseful, every scene essential. Anyway, I'm glad to see critics are giving Midnight Special some serious respect. But I just don't get all of this 'Oh, how exciting, to have a new talent on the stage!'

"Most directors appear and fade away quickly. He's a young director among directors who have proven themselves worth talking about. He's what... in his mid-30s? You have to get excited when you see a new talent pull off two, three, and then four films worth seeing in a row!"

Fair enough, Amalgam. I'm excited. He's on a streak. But your definition of "new" is interesting.

"I think he still seems 'new' because he's trying so many different kinds of things, and we still don't know what to expect from him. I remember you introducing Shotgun Stories to a bunch of students at Northwestern in Iowa, and there was this sense that a major new talent had arrived. But you could put that movie up against any of his other films, and viewers might not guess it was the same director. Shotgun Stories was so understated and believable. But Midnight Special? Like Mud and like Take Shelter, it's something completely different."

You didn't find Midnight Special to be understated and believable?

"It's about a superhumanly gifted child who comes from a cult-like community, who has powers nobody can explain, who is on the run from the law and others, and who..."

Careful, spoilers. The opening scenes are so unusual and clever, you don't want to ruin the surprises.

"You haven't even seen the opening scenes. How do you know?"

It's true. I got stuck in traffic, and got to my seat about 10 minutes into the movie. That's never happened to me before. And I'm not happy about it. But I have it on good authority that those ten minutes are brilliantly executed. And anyway, as man-who-fell-to-earth stories go, Midnight Special seems pretty understated to me, and surprisingly human for long stretches of its running time.

"Well, okay. For movies of this kind, it's thoughtful and intimate. But there are wild and crazy things going on here that don't feel like they're coming from the same universe as what happened in Shotgun Stories or Mud. This is a production on a much more ambitious scale than even Take Shelter. And Jeff Nichols doesn't disappoint with the special effects. They really are awe-inspiring at times."

No argument there. But the more subtle they are, the stronger they are. I'm not crazy about the atomic-blast imagery in this film, but I will never forget a certain moment that involves a boy standing alone in a gas station parking lot, while something appears in the sky behind him. That... I've been dreaming about that scene since I saw it.

"I remember seeing the trailer, seeing that the kid's eyes light up like LEDs, and it made me cringe. I just didn't know if I would buy it. But wow... in context, it's shocking. It's really wonderfully disturbing."

Yeah, I think that the kid's strangeness works because the effects are simple and effective, but also because of the way the adults respond to those moments of superhuman strangeness. I think the movie's greatest strength, its big beating heart, is the father/son connection. Roy (Michael Shannon's character), and Alton (the boy played by Jaeden Lieberher) have a remarkably intimate and intense connection, considering how little they say to one another. I think it's their physical relationship. We see Roy carrying Alton, suffering for and with him, physically shielding him. It's rare that we see that kind of intimacy. And I think that's a very, very good thing.

"I agree, but let's not leave behind Nichols's expert crafting of a convincing science fiction experience. It's not as visually ambitious as a Spielberg spectacle, and some of the effects in the finale were... well, they made me think of Tomorrowland and other weaker sci-fi films. But still, with so many great films already made in this Superhuman Stranger territory, I've gotta hand it to Nichols. He somehow managed to kindle enough strangeness to make this feel fresh for most of its running time."

Some of the strangeness comes from horror films as well as the classic '80s sci-fi blockbusters. I can trace the DNA of multiple details in almost every scene. One scene in particular lifts an idea right out of David Lynch's Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me. Lifts it right out of my favorite scene, in fact.

"You mean, the 'David Bowie Visits the FBI' scene? Yeah, I caught that too."

But I'm not complaining. He's not a copycat; he's paying respectful and reverent homage to his influences. Nichols has a story all his own. You can tell he's wanted to make this movie for a while. It really feels like he's been staging some of these scenes for a long, long time. That's why I find it kind of surprising that the film feels so... old-fashioned.

"Old-fashioned. That phrase used to mean something different to you and me. It used to mean... old. But now 'old-fashioned' refers to movies from the '80s that still feel fresh in our minds."

Well, we're getting old, Amalgam. But seriously — what is it that makes Midnight Special feel so... 1985?

"Well, in the 1980s, special effects were becoming increasingly impressive, but also increasingly affordable. More and more filmmakers were taking advantage of new technology to bring wild sci-fi concepts alive onscreen in persuasive ways. So we suddenly had a rush of movies using special effects to blow our minds with wild spectacle. But the best of the sci-fi films from the '80s dared to develop well-rounded characters. That's why Midnight Special feels like a Son of Spielberg production. There's a strong sense of real people in real situations who discover that they do not have the vocabulary, the frame of reference, or the resources to deal with what's happening to them. It's Close Encounters of the Third Kind. It's E.T. It's Starman. Or... a more recent comparison... it's War of the Worlds."

Okay, okay, I've heard those comparisons before. But I think there's something substantially different going on here than what we get in Spielberg films about wonder. Instead of responding to Alton's otherworldly powers with awe and ecstasy, these characters respond with grief — grief at their inability to save someone they love from forces beyond their control. The more magical he seems, the more he's being taken away from the human sphere. And it works. That's where the film manages to take hold of me. That's what makes me care.

"So you did... like it?"

I can't answer that. I like things about Midnight Special. If you're asking me if I think it's a good science fiction movie, the answer is 'No. It has great sci-fi moments, but it's less than the sum of its parts.' That's because when we finally discover what's Really Going On, it doesn't feel... revelatory. It's just like 'Here's the ending we decided to go with.' It's not something that fulfills the deeper questions raised by the movie. It's not something that gets us any closer to understanding the Why of what this film is really about.

But if you're asking me if I value the movie, the answer is 'Yes.' Because I think that what we see happening in the heads and hearts of the adults feels like genuine turmoil, genuine separation anxiety, genuine grief at the prospect of losing a child to something they don't understand.

"I liked the ending. It felt like a surprising variation on the way these movies usually end."

Oh, it's an intriguing variation! Definitely! Those moviegoers inclined to read films like these as Christian allegory will have a grand time with Midnight Special because it suggests that 'The Kingdom is at hand' instead of saying 'The Kingdom is way up in heaven and we'll ascend to be there someday.' I like the novelty of that. I just wish it was a more satisfying conclusion for this story.

"What would you have done differently?"

I think a lot of the problems in the film are about just how how undercooked some of these supporting characters are. I wish they were more distinct — particularly Sarah, the mother played by Kirsten Dunst. Dunst gives us all she's got, but 'it' isn't very specific. She never develops into more than, you know, a very worried mom, anxious and sad. Only Michael Shannon's Roy fully persuades me of what's happening. And the farther the camera strays from Shannon, the more the film feels just like a variation on a formula.

"Adam Driver's scientist feels real to me. And a surprising change-up from the norm for the role of the Scientist in Pursuit."

Driver's good. I'm glad that Nichols lets his character be somewhat goofy. He's like Keys from E.T., except Nichols doesn't feel compelled to make him seem like a bad guy.

"True. But, nevertheless, there are bad guys in the film."

There are. And they're one of the film's real weaknesses. They're just dumbasses with guns. They're surprisingly one-dimensional threats meant to keep the audience on edge. They don't feel like Jeff Nichols characters. Shotgun Stories... you ask me what movie I would show people to get them thinking and talking about violence in America, and I would start with Shotgun Stories. He's usually so sensitive about the role of violence in his films; but here, the guys with guns seem to be nothing more than a way to jack up the tension.

"Fair enough. Did you think Midnight Special 'overstayed its welcome,' though, like Take Shelter?"

No. I liked that it didn't feel the need to give us an epilogue. It stayed focused on its central question: How will we respond when we realize just how far beyond our control the world really is? Midnight Special awakens our sense that there is much more is at work in the world than is dreamt of in our philosophy.

"Nice work, Shakespeare."

But you know what I mean? That moment — the boy, standing in the parking lot, and then you see what's happening, out of focus, in the distance? It feels scary, but it feels true.

"Yes. That was an amazing moment."

That's what got into my dreams last night. I was sitting on a mountainside with a large crowd of friends, like we were all on some kind of retreat, and I suddenly noticed something going wrong with the sky. And I knew, in my heart, that it was the end of the world. It was a paralyzing feeling — feeling as though we are all witnesses, like an audience, for the end of the world.

"Well, that's more severe, in a way, than what happens in the movie. It isn't the end of the world."

No, but it was one of those moments, you know? Moments when you are so captivated, so scared and enthralled, that you forget you're watching a movie. I haven't experienced many moments like that since I first saw Close Encounters of the Third Kind.

Midnight Special may not be the most satisfying narrative, but it delivers moments that are the reason I go to the movies. Moments that kindle my faith in a world far more extraordinary than what we usually assume. Moments that make me want to resist going home to my routines. After seeing this, I just wanted to get in the car and drive all night, out of the city, into the unknown, eager to witness strange and mysterious things. It made me want to hit the road and flee all surveillance, all networks, all technology. It made me want to step out into those ambiguous spaces of storytelling where we discover things that are unsettling and new. That's worth the price of a ticket.

Dreams come true. Be a part of one.

How would you like to be a part of my first-ever class on cinema, the visual arts, and apologetics?

How would you like to spend time looking closely together into a gallery of imaginations, visions, and lives — and talking about what it all means?

I've been dreaming about this opportunity for years — a chance to spend several weeks looking closely at the relationship between the history of visual art and the history of faith, with a particular focus on cinema.

I've been dreaming about this opportunity for years — a chance to spend several weeks looking closely at the relationship between the history of visual art and the history of faith, with a particular focus on cinema.

I've been taking notes, reading, and arguing with myself about which films would be best to bring to such a conversation.

And now, it's happening.

I've taught week-long film seminars at The Glen Workshop. I've taught weekend film workshops at a variety of schools. And I taught a quarter of creative writing at Covenant College. But I'm delighted to announce that Houston Baptist University is the school that, taking note of my 15 years of "teaching" online about the relationship between film and faith, has offered me my first opportunity to teach a full course on the subject, and to get students writing creatively about cinema. Through their graduate program in apologetics, I'm teaching an online course called "Film, the Visual Arts, and Apologetics."

I visited HBU a year ago, when they invited Scott Cairns and me to speak at their annual writers' conference. I felt honored to be in such accomplished company, and to find so many kindred spirits there. I even got to visit Joshua Sikora's class on the films of Terrence Malick, where I found a large group of students eager to dig deep into questions about the interplay of spirituality and cinema. I find it exhilarating when a Christian college takes on challenging cinema so fearlessly. So I'm blessed to have this new opportunity to participate in what they're doing at HBU.

We're going to have a grand time. Apply by May 1, and you can be part of this first Fellowship of the Moviegoers.

We're going to read about beauty, look at historic works of visual art, watch challenging films, and talk about what we're experiencing over eight weeks... and very possibly become a close-knit film-loving community.

I'd love to have you along for the journey.

And no... you don't have to travel to Houston. The class is online.

What movies will we watch? That's for the students to discover. But I'll say this. One of them may be...

April and the Extraordinary World (2016)

Ten minutes from my house, in downtown Edmonds, you'll find a shop called Otherworlds. It's filled with sci-fi and fantasy books, role-playing games, fan merch from Firefly and Buffy and Doctor Who, birthday cards printed with the Indiana Jones font that say "You belong in a museum!", geek gadgetry and trinkets, and — most interesting of all — steampunk costumes.

And not the cheap stuff. We're talking elaborate, high-quality masks and hats and jackets and shoes and fake weapons (like vampire stakes) and accessories — and enough fancy spectacles and goggles to fill a Guillermo Del Toro movie. It's extravagant fantasy dress-up for people who have big budgets for costume parties.

I love this stuff. I wish I could afford some of those hats. You get the feeling that putting one on will automatically transform everything around you. There's something about this imaginary world, this alternate history where computers and electricity never took over civilization, where people travel by zeppelin, where ground transportation is powered by steam, that re-enchants the world.

So why is it that, whenever I ask for recommendations of the great steampunk fantasy novels, the answer is almost always heavily qualified? "Well... there are good steampunk books. But the great one is yet to be written." I've heard that more than once. Occasionally, someone will make an argument that Cherie Priest is the best steampunk author out there, but no, not the one that all steampunk fans have been waiting for.

That always raises another question. What's the great steam-punk movie? There aren't many contenders. The Golden Compass? Good steampunk elements, lame movie. The closest thing to a great one that I've seen so far is Sky Captain and the World of Tomorrow.

I had high hopes for April and the Extraordinary World, even though the American-release title sounds more than a little desperate to get our attention. It turns out that this French animated epic, directed by Christian Desmares and Franck Ekinci, and spun from the imaginative loom of French graphic novelist Tardi, delivers on the title: It's about a young woman named April... and she's having adventures in a world that is truly extraordinary: one clouded with coal pollution, grim with post-war ruins, and alive with robots and strange modes of transportation.

But the problem is that April's world is so extraordinary that neither the characters nor the story itself every really amount to much. It strikes me a film in which the artists were so caught up in the wild possibilities of their alternate history that they couldn't bring themselves to spend much time thinking beyond the story's rather perfunctory treatment of questions about science and responsibility.

So, see if this sounds good to you: History veers wildly off in an alternate direction during the late 19th century, when Napoleon III forces scientists — and not just any scientists, but all of the famous ones we can name-check — to help him produce an army of invincible warriors. Living in hiding, one family of good-hearted scientists are more interested in discovering a cure for bodily harm and death. But when Napoleon's surveillance finds them serving some other cause than his own, the family tries, and tries, and tries to escape. (This is the first of the film's many long-running chase sequences.)

April, of course, gets away with her talking cat Darwin (another triumph of science) and, though they don't know it yet, what may well be the cure-all potion. And the film's simple storyline is pretty much determined: She (voiced unremarkably by Marion Cotillard) and Darwin (by Philippe Katerine) will have adventure after adventure dodging the bad guys, trying to recreate the serum before age and illness end the cat's life. That timid young miscreant in the shadows will, of course, go from spying on April to falling for her. And everything will eventually come full circle to... well, that would be telling. Let's just say that it involves a rocketship, reptiles in robot suits, and an Edenic wonderland where what's left of earth's natural beauty clings to life.

Perhaps steam-punk enthusiasts will find this satisfying. (Film critic Glenn Kenny was certainly enthralled.) And sure, details like this world's double Eiffel Towers, the spectacular cable car lines, the sinister dark clouds sparking with lightning are occasionally awe-inspiring. But the Keystone Cops klutziness of the police who pursue April rarely registers as funny. The constant shoot-outs, chases, explosions, Transformer-like shape-shifting of vehicles and buildings — all of this makes things too clamorous, and the escapes are always so outrageous that no one is likely to feel anything like suspense. In the constant calamity, I never quite get attached to the characters (with the exception of Darwin the Cat, who is a one-of-a-kind animated character from his whiskers right down to his cartoon testicles).

Perhaps steam-punk enthusiasts will find this satisfying. (Film critic Glenn Kenny was certainly enthralled.) And sure, details like this world's double Eiffel Towers, the spectacular cable car lines, the sinister dark clouds sparking with lightning are occasionally awe-inspiring. But the Keystone Cops klutziness of the police who pursue April rarely registers as funny. The constant shoot-outs, chases, explosions, Transformer-like shape-shifting of vehicles and buildings — all of this makes things too clamorous, and the escapes are always so outrageous that no one is likely to feel anything like suspense. In the constant calamity, I never quite get attached to the characters (with the exception of Darwin the Cat, who is a one-of-a-kind animated character from his whiskers right down to his cartoon testicles).

By the time the film finally brings the heroes face to face with the villains, these two hours are beginning to feel more like three.

What's it all really about? This "extraordinary world" (a more accurate translation is "twisted world," but that might not have sold tickets in America) is suffering from severe pollution and environmental devastation due to its dependence on charcoal — merely an exaggeration and a dry satirization of our own self-destructive addiction to oil.

But the film has no real insights to offer, just a murmur of melancholy bordering on despair. April's bravery will lead to a blandly explosive conclusion, and it will all conclude on an artfully poignant note. But for my money, the period-detail exaggerations of Guy Ritchie's Sherlock Holmes movies get me closer to the right balance of storytelling and world-building that would make up the steampunk movie of my dreams. And as tributes to Tardi go, the comic-book glories of Luc Besson's The Extraordinary Adventures of Adèle Blanc-Sec — a live-action fantasy adventure that might have been a surprise hit in America if it had been given a good marketing push — remains the most rewarding.

So, here's an opportunity, artists: Steampunk is a wildly popular genre that is still waiting for both a defining novel and a defining movie. For me, that most satisfying steampunk experience remains that curious costume shop, which if filled with artifacts from an otherworldly experience, silent and suggestive, filling my head with stories of my own.

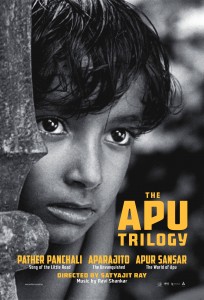

Two hours of texture

"Rotting away in one place year after year does no one any good."

Obvious? Perhaps. In the whole of Satyajit Ray's landmark 1955 film Pather Panchali, that is the closest thing we find in the dialogue to a "message" — and it's pretty on-the-nose.

Still, we shouldn't rely on what the characters say to tell us what the movie is about. The wisdom of this movie is in the silent gazes of its characters, who are often shown staring — staring at one another, staring into space, or in the case of the ancient grandmother, staring into increasing darkness. Despite what that head-shaking neighbor wryly observes about the suffering and the stuck-ness of the movie's central family, Ray reveals enough natural beauty in this place of rot and ruin to make Terrence Malick weep.

While the father's gaze is turned to faraway opportunities, while the mother's gaze stares into all that she does not have, and while the daughter's gaze looks increasingly downcast because of her dwindling hopes, the young boy's eyes are wide open, soaking in the wonder of what surrounds him, the occasions for joy, the horrors of loss and death, the lies that people tell, the secrets that they keep, and the sinister advance of advanced and electrical foreign cultures. He is the one who makes the strongest impression. He is the one, we suspect, in whom Ray sees himself. The boy's eyes are his cameras.

Where Danny Boyle (God bless him and his boundless enthusiasm) couldn't help but exaggerate India's appearance in Slumdog Millionaire — turning so many scenes into carnivals of color and style, dressing the movie up in flamboyant exaggeration — Ray's approach is to attune our eyes to what he finds at hand, to find beauty rather than impose it.

Where Danny Boyle (God bless him and his boundless enthusiasm) couldn't help but exaggerate India's appearance in Slumdog Millionaire — turning so many scenes into carnivals of color and style, dressing the movie up in flamboyant exaggeration — Ray's approach is to attune our eyes to what he finds at hand, to find beauty rather than impose it.

I am so glad that I finally sat down to watch this film all the way through, and I'm looking forward to the rest of the trilogy. You can watch Pather Panchali as a heart-smashing drama. You can watch it as a coming-of-age tale, in which a young boy's wide eyes become our own. You can read it as a progression of Italian neorealism, as a variation on Ozu's sense of composition, or as a precursor to the nature-versus-technology tensions of David Lynch.

Or, thanks to The Criterion Collection's beautiful restoration, you can lean forward and marvel at this tour of textures:

- Dust.

- The smooth skin of a child; the exquisitely detailed skin of an old woman.

- Tears.

- Leaves.

- Mud.

- Long feathered grasses.

- Electrical towers stark and looming like the aliens from War of the Worlds.

- Billowing smoke from a train.

- Water striders making giddy circles on still water.

- Rain.

- Rain in late-night lightning.

- A comb through wet hair.

- Spiderwebs.

- Bogwater, swallowing a long-kept secret.

While Ray never denies that this family needs hope and provision, his imagination casts a wide enough net to help us see that their world of poverty is not a dead end, but is rich with beauty. They may rightly hope for escape, but we will want to go back to this place again and again.

Before Midnight Special: Looking back at Jeff Nichols's masterful debut

I've just seen Midnight Special, and I'm working on a review. But first, I think it's worthwhile to remember that director Jeff Nichols was able to make Midnight Special — to build up to such an ambitiously Spielberg-ian project — because he has had such a strong first decade as a filmmaker.

So let's look back almost ten years to his debut, 2007's Shotgun Stories. In 2008, I had the privilege of interviewing Nichols. And when I was invited to speak about film at Iowa's Northwestern College, I asked that we begin my visit with a screening of this film, because it's such a strong demonstration of the power of movies to challenge our thinking and stir up discussion and debate. And I still think it's capable of doing that for us today. It may be a more important film now than it was then.

[This post was originally published at Good Letters, a blog hosted by Image, on September 24, 2008.]

•

I tried to write about Shotgun Stories without mentioning you-know-who. It’s become such a cliché. A talented new artist captures a sense of the sacred and the profane in the American South, and before you can say “Christ-haunted” or “Southern Gothic,” there she is! It’s almost as if the standard-bearer of the genre created the South, just as the man who made Middle Earth is mentioned whenever we discuss contemporary fantasy.

For me, the American South seems as fantastical as Mirkwood Forest. I’ve never lived there. My understanding has come from stories like Wise Blood and The Violent Bear It Away. So, when a bold new voice brings the truth to life in the cotton fields, catfish farms, family feuds, and civil wars of Arkansas — as writer/director Jeff Nichols has done with his first feature, Shotgun Stories — I can’t avoid the comparison. Within a few short scenes I sense a compelling authenticity and a familiar flavor of insight.

Nichols’s leading man, Michael Shannon, seems to have emerged from an illustration in a book by Faulkner or Steinbeck. He plays Son, one of three despondent Hayes brothers embittered by their father’s neglect. Son, Boy, and Kid are poor, but resourceful; cantankerous, but loyal; uneducated, but keenly aware of injustice. As they sit on a curb at the end of a workday, their conversation is revealing: “This is one empty-ass town.” “It’s like we own it!” “If I owned this town, I’d sell it.” “We don’t own the square root of shit.”

After news arrives of their father’s death, Son and his brothers crash the funeral. There, we learn that Mr. Hayes abandoned them for something new, a “redeemed” life — he sobered up, married a good Christian woman, gave his life to Christ, and raised new sons. Son interrupts graveside prayers, harshly reminding the astonished mourners that his father’s sins went unconfessed and unresolved, and then spits on the coffin. Thus begins a violent, bloody civil war between the two sets of sons.

Nichols knows this territory. He grew up in Little Rock, Arkansas, and he clearly drew some insight from that Bible-belted region. (He even gave Merle Johnson, the pastor of his childhood’s Trinity Methodist church, the role of the funeral’s minister.) And he’s benefitted from his friendship with director David Gordon Green (George Washington, Snow Angels), who attended North Carolina School of the Arts with him. Both artists know the power of pregnant pauses and open spaces. Like Terrence Malick, Nichols knows that the sight of a combine transforming an Arkansas cotton field into an apocalyptic dust storm is as eloquent as anything his characters might say.

But the film’s most formidable character actually never appears — except when he’s inside that pine box. Nichols tells me that developing the late Mr. Hayes was the first step in writing this story. “Then,” he says, “when you step away from the father, you’ve built an entire world for your characters to live in. [So much] happened before the movie starts, the train is at full speed by the time we join in.”

Nichols sees this story as a reminder that faith must be “a holistic practice.” He says, “Hayes was able to turn things around in a relatively positive way. The one thing he didn’t do was go back and fix what he left behind. Whether that was from shame, or from something else, it doesn’t matter. You can’t say you’re one thing and be another. You have to examine your entire life. I think that’s what Christianity is really all about for me. It’s about constantly striving to be something that’s decent.”

As simmering hatred rises to a boil in the film, it’s uncanny how some moments, some lines, seem inspired by recent speeches and justifications for global conflict. That brawl in a liquor store parking lot may as well be a Baghdad skirmish.

https://youtu.be/EHgLR6TYyOQ

Nichols resists summarizing Shotgun Stories as either a political statement or a character drama. “It had to be both,” he says, “in order to avoid falling short on either count. But there’s no question that what is going on in the world is directly reflected in Shotgun Stories. An eye for an eye is alive and well in the American consciousness, and in our political policies.... You look at these conflicts in the world and wonder, how can we resolve these problems? All of these ‘feuds’ are supported by plenty of history... history that validates a lot of anger. But both sides can just go on perpetuating the violence into... into forever.”

Avoiding both sentimentality and predictable shootouts, Nichols arrives at a thought-provoking conclusion. “Some people like the ending, some people don’t. Some are crying for blood,” he says. Laughing, he adds, “Me, I find it extremely scary.”

It’s enough to remind one of what a certain famous Southern writer said: “The Christian writer does not decide what would be good for the world and proceed to deliver it. Like a very doubtful Jacob, he confronts what stands in his path and wonders if he will come out of the struggle at all.”