Walking out of The Secret Life of Pets

This just in on Facebook from my friend Christy Tennant Krispin — a testimony worth considering:

My son and I just walked out of The Secret Life of Pets.

It was a mutual decision — he showed remarkable discernment for an 8-year-old boy.

My first moment of disgust was when they introduced the lead bad guy and he was voiced by Kevin Hart with a hyper-stereotypical black thug voice. I was so disappointed. I'm trying so hard to teach my son how to see his black brothers, and then I take him to yet another movie where the negative stereotypes are reiterated. (Thank goodness, again, for the decision J.J. Abrams made to make one of the lead heroes* in the new Star Wars movie a black man. Let's have more of that, please.)

It would have been so much more creative and funny if they had voiced the lead thug with someone like Melissa McCarthy. Now that would have been hilarious. We should/could have left then, but it was when the pets started discussing how they could kill their humans/owners — when they started talking about chopping them up in a blender — that we were done. My son put his hands over his ears and said, "I don't want to hear this." I told him we could leave and find something else to watch, and he eagerly agreed.

I came home and looked up reviews, only to find that none of them I read (even from PluggedIn and Common Sense Media) shared my concerns. They gave positive reviews.

So for what it's worth, neither I nor my son enjoyed it, and we disliked it enough to leave and ask for our money back.

We stopped at a garage sale on the way home and I gave my son some of the money from our refund, which he used to buy a microscope for $2. Which I thought was a great choice.

And now we're off to the library so he can pick out another movie to watch on DVD. Maybe they have The Force Awakens" available. Now that's something we'd really enjoy.

UPDATE

It turns out that Christy is not alone.

Thanks to Steven Greydanus (who gives the film a "C-" at Decent Films) for pointing me to this review from Walter Chaw at Film Freak Central:

It's not remotely witty, never for a second clever, and with a typecast Kevin Hart voicing a one-trick racial pastiche of a bunny, it underscores the cultural divide between those who think Minions and The Lorax are unwatchable dreck and those who are wrong. It's machine-tooled to make money, which it will after the manner of other things that make money at the expense of your children, but it's worth considering that the reason for most of the terrible things in this world is our agreement that critical thinking is a burden, while anti-intellectualism is a roadmap to our survival as first a civilization, then as a species. In our society, saying that something is "for kids" means that it's better, safer...unless it's entertainment. The greatest trick the devil played is convincing an entire culture that it's better not to waste time wondering if what you put in your child's head is productive and smart. So long as there's no sex in it, game on. If The Secret Life of Pets(hereafter Pets) were a chair, it would be made of broken glass and rusty nails. But hey, never mind, why criticize? It's just for kids.

"First Step Into a Larger World..."

"You've taken your first step into a larger world." - Obi-Wan Kenobi

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HUb_zpdyDpU

Star Wars goes Saving Private Ryan in this intense, revealing highlight reel full of new alien costumes, heavy violence, and surprisingly cinematic promise. I'm not ready to get my hopes up about the narrative, but this is beginning to look like the most skillfully filmed, most convincingly realized Star Wars movie of all.

Soon, there will be a Star Wars episode for every moviegoer — those who like children's stories, those who like abstract art films, those who like hyper-violent war movies, those who like poetic meditations, those who like comedies. George Lucas gave storytellers a box of 64 crayons, and now, for better and for worse, the kid in everyone gets to take it all apart and put it all together again with his or her own imagination.

Unlike what we've seen from Marvel so far, the Star Wars universe offers so much more than heroes and villains. It has a range of possible scenarios and characters that aren't limited by superhero tropes. Its best stories are those that, in the midst of all the whiz-bang adventure and violence, resist the temptation to become intoxicated with violence, and instead carry a soulful sense of grief over loss, an earnest concern for sacrifice and reconciliation, a hope for peace and the redemption of villains. The heart of the original trilogy is Luke Skywalker's realization that power can make him a monster, but forgiveness and peacemaking can redeem heroes, villains, and the cosmos as a whole.

Yoda's first words to Luke become his best words to Luke: "Away put your weapon!" So, if the new Star Wars movies do what they're capable of doing, they'll make kids want to be brave enough to embrace non-violence rather then sending them scrambling to buy toy blasters.

There will probably be a lot of disappointing films, but I'm sensing that an impulse of one-upmanship among directors, each of whom have always wanted their shot at taking Star Wars to the next level, may result in some surprisingly creative cinema... aesthetically, at least, but I'm hoping they all compete to write the best, most meaningful Star Wars story.

Anyway, either this trailer has given me real hope, or my coffee is giving me a fleeting but naive shot of optimism.

Whatever the case, Star Wars is turning into the big screen's most engaging creativity contest.

May the Force be with them, and may the artist with the most wisdom win.

La Dolce Vita (1960)

One of my favorite things: Camping out in my home office, putting on a classic film I've never seen before, and live-posting my thoughts to the Looking Closer Specialists. Why? They're a smart, film-literate bunch, and I end up learning from their observations. A few months ago, I live-posted my first-impressions of La Dolce Vita for them, and it led to some revealing exchanges. It's always good to discuss a classic with viewers who know the movie better than me.

Of course, live-posting is clumsy posting. So these first impressions have been cleaned up a bit.

•

Ah, that famous opening shot — Jesus on the cross, flown across the city like a Macy's Thanksgiving Day Parade Balloon.

I know this shot not because I've seen it before, but because I've seen it spoofed before... most effectively in Steve Martin's L.A. Story, when a hot dog is helicoptered over Los Angeles.

The rest of this film will be Christ-haunted. He'll hover over everything. Is that what Fellini intended? Probably not. But that doesn't matter. It's what the film does, not what the filmmaker intends, that matters.

•

Maddalena (Anouk Aimée), getting out of the car and leaning against a retaining wall, strikes me as quite possibly the inspiration for all of those glorious Christopher Doyle shots of Maggie Cheung leaning against the alley wall in Wong's In the Mood for Love.

If so... thank you, Fellini.

•

"You need friends in high places these days," says the woman who leads Marcello down into her flooded apartment.

Uh-huh. What did I tell you?

•

Already I'm noticing the prominence of stairways and transparent barriers (curtained windows, glass walls, maze-like divisions and barriers). They ways we separate ourselves from one another. The crazy paths that we, like Marcello (Marcello Matroianni), carve for ourselves in a world that doesn't look up.

•

Driving Emma to get help after her suicide attempt, Marcello arrives at the bottom of a long stairway. The camera pans up to find a nun waiting at the top: Friends in high places, eh?

•

A press agent, reporting on the arrival of a glamorous Swedish film star at an airport, says as an aside, "Nice piece of meat, eh?"

The paparazzi were clearly as beastly then as they are now.

(Is it true that the word actually comes from the photographer named Paparazzo in this film?)

•

I love how, in the "press conference" for Sylvia, the pin-up blonde actress from America — Conference? It's really just a bunch of drooling idiots asking stupid questions — somebody asks if she thinks Italian neorealism is alive or dead. And she looks as though she has no idea what that means.

It's a moment that's all too depressingly realistic.

•

While Marcello's infidelity is portrayed as a moral failing, Emma's feelings about her man's betrayal make her look awfully pathetic. This has the unnerving effect of making Marcello hold on to his appeal in spite of his behavior.

Poor Yvonne Furneaux. It must have been exhausting to play this hysteria.

•

What a great long shot of Emma, anxiously talking on the phone while sitting on the edge of her bed, down a long hallway where buckets of paint and brushes and newspaper sit neglected.

•

Aaaaand we're ascending another stairway. In a church.

"Shhh," says Sylvia (Anita Ekberg). "We're in a church."

Marcello, trying to look cool, is chasing the actress upstairs, looking for his moment. There are disorienting, vertiginous effects as we follow his ascent, while the bells ring. Is this meant to be a blatant homage to Vertigo? Hitchcock's masterpiece opened two years before this movie. Seems plausible.

•

"You are the first woman on the first day of creation. You're mother, sister, lover, friend, angel, devil, earth, home. That's what you are: home. Why did you come here? Go back to America please? What will I do now?"

So... America gets the blame for Sylvia, the mother of all temptations.

•

When Sylvia starts leading everyone around the party in a parade, I'm flashing forward to the inanity of the circus parade, the line dance of fools, at the end of 8 1/2.

Already, at this point of the film, I'm pretty sure I'm going to end up preferring 8 1/2.

•

I love how, when Sylvia leaves the party, Marcello goes after her carrying her shoes... underlining that this is all an illusion, and the magic could vanish at the stroke of midnight. But it's a reversal of the values of Cinderella — in this case, the magic spell is a dream of vanity. And in this case, the coach will not carry the princess back down to earth, but just further into the maze of fame.

•

A great moment: Marcello, the morning after his frolic in the fountain with Sylvia (and his subsequent beating from Robert), goes into a cathedral and hears someone whisper his name.

His first instinct is to look up.

•

... And, of course, he is invited up. Up to meet the padre: Another friend in high places.

Steiner: "As you see, these priests don't fear the devil."

•

Steiner on the cathedral organ: "Sounds we're not used to hearing anymore. Like a mysterious voice from deep within the earth."

•

Marcello envies the man with the family, the home, the stability, the maturity, the apparent success. But...

"The answer isn't being locked up at home. Don't do what I've done. The most miserable life is better, believe me, than an existence protected by a society where everything's organized and planned for and perfect."

This speech. Oh man.

"Sometimes at night the darkness and silence weigh on me. It's peace that frightens me. I fear peace more than anything else. It seems to me it's just a facade with hell hiding behind it."

Look up, dude.

"One should live beyond passion and emotion in the harmony found in perfect works of art, in that enchanted order. We should learn to love one another, to live outside of time, detached. Detached."

Wow, what a speech.

The seemingly successful man, whom Marcello admires, who has a house and a family and means and sophistication, who seems to have achieved any ambitions Marcello might once have had... even this man is dissatisfied with his circumstances.

He senses that art is reflecting what is missing. (Is it making "sounds like we're not used to hearing anymore"?)

But I'm intrigued by his suggestion that the answer is in detachment. Surely it isn't. Love requires the opposite of detachment. And this whole film is full of vigorous, visceral, bodily love.

And yet... and yet... this speech follows so hard upon his words about art, I wonder if I'm interpreting him correctly. (Maybe something is lost in translation.) It's true that beauty is, in a way, indifferent — it gives and gives to the just and the unjust; it is a wild expression of God's grace. (Simone Weil writes about this.) I wonder if what he's referring to isn't exactly detachment from life, but perhaps detachment from fear and circumstantial concerns.

•

Heading into Spoiler territory now:

I was startled to full attention by the grim turn of events near the film's conclusion — the circumstances involving the demise of three characters. I wasn't sure what to expect after that. And what happened was, yes, entirely unexpected. Just another party? Really?

Ah, but this one brings out the worst in Marcello — he's going to pieces. Faced with mortality, he knows that the path he has chosen offers no consolation, no meaning, no hope.

•

The finale on the beach ... I'm not quite sure yet what to make of it.

The young Lolita-like woman calling to Marcello seems to suggest both an invitation back toward innocence, but also an invitation toward the most severe kind of error he could make.

So, as he walks away, he seems to be in purgatory, unable to take a path toward redemption or a path toward ultimate destruction... and, frankly, unable to tell which of those two the offered route represents. The path toward the girl might actually represent innocence, but at this point, isn't any direction that Marcello goes corrupt merely by virtue of his incurably depraved intent?

Sing Street (2016)

Someday we'll find it,

The rainbow connection —

The lovers, the dreamers, and me.

- "The Rainbow Connection," The Muppet Movie

•

[This review is dedicated to Laure Hittle, one of the Looking Closer Specialists,

whose contributions to keep this website alive made this review possible.

Want to become one of the Specialists and join our Facebook group? Here's how.]

•

When you were a teenager, what was it about your body that embarrassed you the most?

I'd have a hard time making a short list of possible answers for myself. In high school, I had a variety of nicknames mocking my nose, my bowl-shaped haircuts, my crooked teeth, and the strange curve of my spine. But worst of all — and this continues today — my neck and face would blotch blood red when my adrenalin spiked. Today, it's most noticeable when I get up in front of a class for a lecture. But when I was a kid, it spiked ever higher the closer I got to a girl. Nothing I could do about it.

From the early scenes of John Carney's Sing Street, I felt a strange kinship with Conor, the young and artistic Dublin teen played by Ferdia Walsh-Peelo. I noticed a surprising physical resemblance between him at age 17 and myself at that age. But then it happened — he bravely approached a girl right out his dreams (or at least out of a Duran Duran music video), and lo... his neck and cheeks flushed crimson. I burst out with a laugh of recognition — the kind you laugh when you feel like crying.

Conor — even though he's skinny and awkward and obviously poor, even though he's moving through a dangerous and bully-dominated boarding school environment — puts on a show of confidence, as I used to do. He is audacious, as I used to be.

He marches right up to Raphina (Lucy Boynton), a beauty who looks a couple of years older than him, and who is probably the most worshipped girl in his neighborhood. And he makes her an offer. Will she be the star in his band's next music video? Never mind that he doesn't have a band. Or a song. Or a video.

Which is something I would have done. Even though I was the kind of guy girls liked to have "as a friend," not as a boyfriend, I was crazy enough to save up to secretly purchase a diamond — a diamond! — for a girl I liked, without any comprehension of how insane it was, or how much damage it would do to my reputation. I was out of my mind when I was in love, but that's the point — when you're "caught up" like that, you learn just how brave you can be. You may make a fool of yourself, but you may also discover what you're capable of.

I was a lot like Conor. I hope that, in some ways, I still am.

Add to this that the film is set in 1985, just a couple of years before I was Conor's age. So, even though it is set in Dublin, Sing Street's soundtrack seems to have been composed by someone with a direct line to my nostalgia circuits.

So how can I help but root for this guy, as he tries to give shape to his dreams while suffering the storms of his own adolescence and his family's poverty?

Carney's film Once balanced a sort of "man on the street" realism with lush and romantic musical flourishes, and it did so with such heart, and with such appealing cast members, that viewers — including me — could not resist. Sing Street is even more blatantly conventional in its underdog-chases-the-girl-of-his-dreams cliches. It's like Say Anything meets Billy Elliott meets The Commitments — in the best possible way.

A great deal of Sing Street's fun is in the way it celebrates the sounds and the style of the '80s. The audience laughs in recognition as Conor and Company put on looks inspired by overcoated, lipsticked, and eyeliner-smudged pop idols like Simon Le Bon and Robert Smith. (Watching these guys nervously consent to makeovers, I couldn't help but remember my own sense of panic as I emerged from my own freshman dorm room wearing makeup for a band photo shoot.)

And what this film does best is what Once did best: Carney, who was once in a great band called The Frames, captures the magic of songs coming together through improvisation, cooperation, and imagination. Anyone who's been in a band will recognize the sort of fever that sweeps through this group of rookie rock stars as their rhythms and riffs starts connecting and catching fire.

And, unlike so many other birth-of-a-band movies, Sing Street's songs are really good. They wear their '80s influences on their sleeves (as they should, since it's a movie about learning by imitation), and they get their Brit pop hooks in.

One thing Conor has that I never had is an older brother: Brendan (Jack Reynor) is the film's secret weapon, its truly tragic figure. Brendan believes that he's already — by being wasted — all of his chances as an artist and a visionary. So he appoints himself as Conor's advisor, living vicariously through the kid's crazy drive, determination, and success.

It would be easy to say that Sing Street is as cliche-driven as most formulaic Top 40 pop songs. But what's remarkable is just how affectionately and winsomely it embraces those conventions, never pretending that they come as a surprise, and delivering them with personality and particularity. These characters are persuasively real. In the predictable troubles of Conor's family life, there is a gracious tone of compassion and genuine sadness. In the unlikely love story, there's remarkable sweetness and tenderness; as in Moonrise Kingdom, this is a real romance, not a rush to lose virginity. And so, when the joys come, they've been earned.

Joy is the film's reason for being, and joy wins the day.

The film's only real weakness its incongruously one-dimensional villain. The Catholic school headmaster is a cruel cartoon, representing the film's wholesale dismissal of religious faith — even as it paints rock and roll as the way of salvation. He's a convenient target at the film's finale, giving the heroes opportunity to shame their enemy and gloat. It's a note of cheap crowdpleasing that sound dissonant in the context of so much heart.

Nevertheless, I found myself moved by the film's fairy tale finale. Are these kids crazy to cast off family, education, and tradition, and launch into the wild blue yonder in pursuit of their dreams? Yes, actually. I suspect it will not go well for them in the long run.

But as today's dreamers face increasingly disheartening obstacles, as artists around the world have become so exploited that they cannot make a decent living, it is rather exhilarating to feel, if only for a few moments, that they're being brave by pursuing their dreams. Maybe it'll make a life-changing impression on some dreamers in the audience.

I think it made an impression on me.

I saw my younger self there on the screen, willing to give everything for the love of my art, for the call of the dream. And I missed that awkward, vision-driven kid very much. I left the theater singing. And a couple of weeks later, I wrote my resignation letter — the adrenaline pumping redness into my face — and determined to leave the job that was killing my dreams. I set out, against all odds, to try doing what I love. Like a fool. Like a dreamer.

That's the power of a movie like this one. It'll make you "drive it like you stole it."

Pray for the Conors and the Raphinas of the world... the lovers, the dreamers, and me.

Farewell to the Master

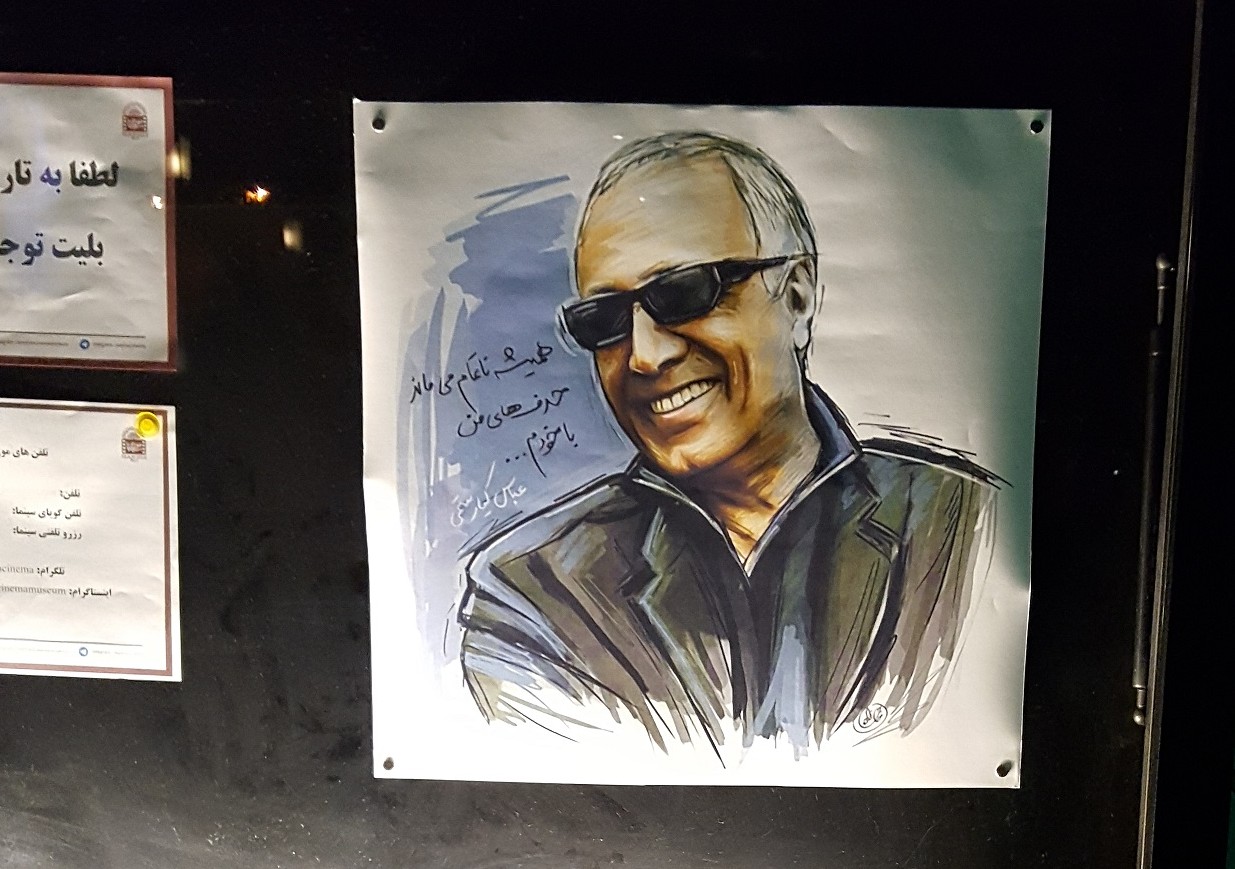

My favorite living filmmaker?

I don't know how to answer that. Not anymore. The answer was clear — Abbas Kiarostami, the visionary who brought us Taste of Cherry, The Wind Will Carry Us, Certified Copy, and Like Someone in Love.

But Kiarostami died on Monday, July 4. He was in Paris, where he had been receiving treatment for cancer. He was only 76. And I was eagerly anticipating his next film.

As it's the end of the quarter, and I'm busy grading papers, I haven't had time to write up a suitable tribute celebrating his work. So I will have to settle for sharing some others, and revisiting the couple of times I've written about his films.

Here are my reviews of

- Like Someone in Love, and

- Certified Copy (which is my favorite film of this decade) so far.

Here are remembrances from:

Howie Movshovitz (NPR):

Kiarostami was revered by many around the world, and he mentored and inspired two generations of filmmakers in Iran. According to friend and translator Khazeni, he always saw beyond his status.

"He had at once a grasp of his stature and a complete humility vis-à-vis what had been decreed about his work," she says. "He just worked. That was what he had to do. ... And that's what makes me so unhappy about the news of his death, because he had many more films to make."

Tina Hassannia (The Globe and Mail):

...while Kiarostami has long been championed as one of cinema’s greatest artists – a filmmaker who deftly balanced humanism and poetry – his legacy rests on one, giant accomplishment: his films frequently challenged the simplistic image of Iranians as religious fundamentalists. His work demystified an entire people who were so often misrepresented by the Western world.

Moinak Biswas (The Wire):

The passing of Abbas Kiarostami (1940- 2016) is one of those moments of mourning that have become rare. It is more common to mourn the loss of technological forms than individuals in the world of filmmaking today, as we are told the age of the masters is no longer with us. Kiarostami was indeed one of the very few filmmakers to emerge in the last couple of decades to be recognized as an ‘auteur’, long after the word lost its currency in film criticism. It is not easy to think of another artist who dedicated himself with comparable seriousness to thinking and feeling with the cinema, to exploring the mingling of life and image into a single breath and flow.

Kevin B. Lee (Fandor) :

Kiarostami’s relentlessly open and inquisitive understanding of cinema was and remains indispensable at a time when “cinema” appears to be dissolving into something else. The advent of digital media and social media platforms has led to an explosion of moving image forms, transforming what we once knew as “film” into any number of modes and mediums. I wager that most people who’ve seen Kiarostami’s films haven’t seen them on film, but on DVD or online video. What does it mean to watch them in these conditions, when they for the most part seem intended for the cloistered quarters and undivided attention afforded by the theatrical cinematic space? Even when Kiarostami embraced digital filmmaking in the 2000s, he did so in such a way to stretch attention spans, not compress or cater to them.

https://vimeo.com/173859927

Vahid Mortazavi (Fandor):

... here lies the essence of Kiarostami’s cinematic trajectory: from the start, we see a unique filmmaker whose obsession with the act and ethics of looking is reflected in the development of his characters. They grow ever richer while he continues to search for the right way of looking into human nature.

Tope Ogundare (Fandor):

This video is a brief exploration of Kiarostami’s use of cars as dramatic spaces, featuring the dubbed narration of the Iranian great, from his masterclass/documentary 10 on Ten.

https://vimeo.com/173468448

Via Melissa Tamminga, here's a documentary called "Abbas Kiarostami: The Art of Living":

https://vimeo.com/173519394

And here's Melissa's wonderful piece on Certified Copy.

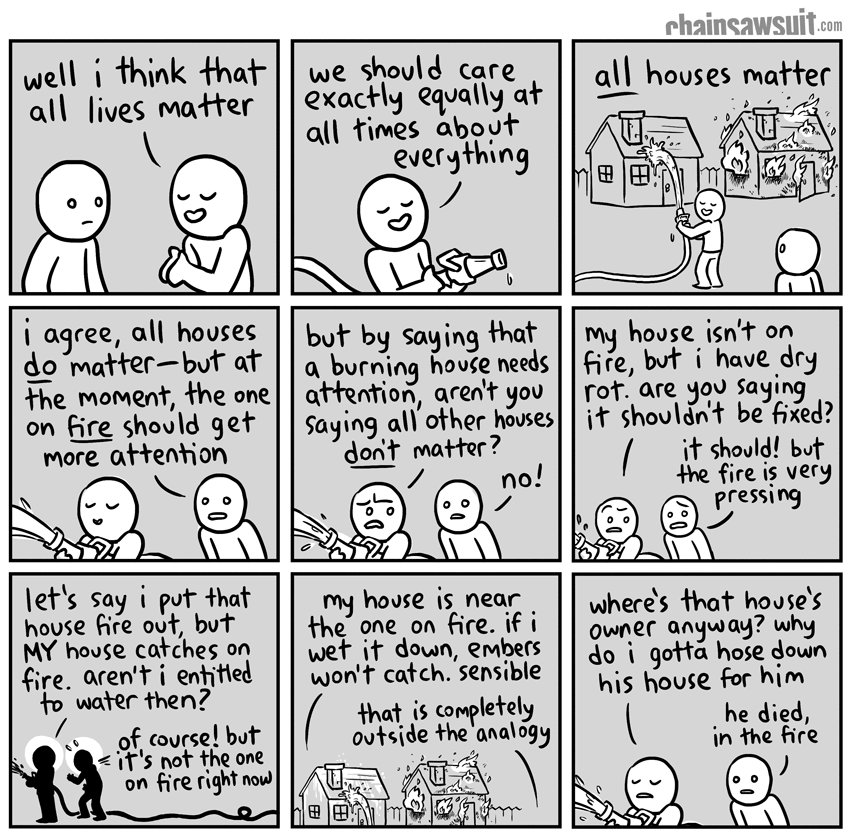

House on fire!

Sometimes, a comic strip can help clarify a complicated issue. This one is worth sharing this week, via Chainsawsuit.com.

Archival footage of creation discovered?

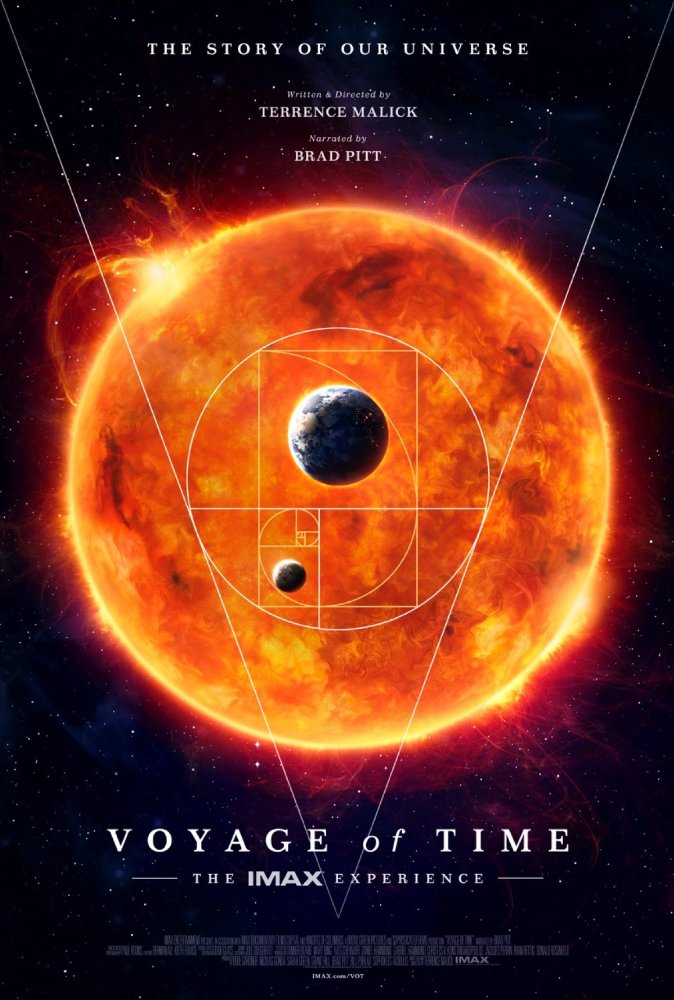

If you went back for seconds and thirds on Terrence Malick's The Tree of Life for the thrill of its big-screen cosmic excursions, this new documentary might seem almost redundant. But the teaser here, in spite of the uninspiring voice-over by Brad Pitt, is enough to make me suspect we'll see much that we haven't seen before.

https://youtu.be/YVyWObJY9FQ

(More information here.)

I've never been a big IMAX fan. The immersive effect of an enormous screen is pretty cool for a while, but it always makes movies into something more like an amusement park ride than an encounter with art.

Personally, I'm more interested in the long-form, non-IMAX version of the film, which is narrated by Cate Blanchett. It seems obvious that we'll get more of a sense from that one about what compelled Malick to make this journey. Surely its about more than mere camera wizardry. As cameras become more sophisticated, nature photography seems to become more dazzling all the time.

And past documentaries that have sought to overwhelm me with a constant river of dazzling images have not stayed with me past my dizzy, meandering stroll back to the car.

Bakara, for example, was awesome while you were watching it, but I can't remember if it did much in the way of exploring ideas.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KIxawleLISM

Malick's passion for this project suggests it will be more than a compilation of mind-blowing images, more than the sum of its awesome parts. (Its Awe Sum?)

As with Malick's last few films, I'm proceeding with caution and controlled expectations. I haven't been wholly swept up by his meditative mode since The New World. But right now, considering the nature of this month's turbulent news — murders, guns, lies, betrayals, greed, prejudice, wars, rumors of wars — something glorious, cosmic, and revelatory of the Creator's sovereignty throughout the universe might be just what the doctor ordered, restoring perspective, inspiring a sense of possibility, and even making me long to experience what our Maker will do beyond this wicked and wearying age.

Finding Dory (2016)

This review is dedicated to Cynda Pierce. I have recently suffered some heavy setbacks to my work as a writer. Cynda's generous support of this website made a timely trip to the movies — and this review — possible. I'm grateful for her gift of encouragement, and her membership among the Looking Closer Specialists.

•

She's a fish. With serious short-term memory loss. Who has been separated from her family and her home for years. And who doesn't know how to find her way home because, well... she can't remember much of anything. There's just this impulse in her heart saying "Seek! Find! Seek! Find!" There's this emptiness where love used to be, and it says, "Heal me! Fill me up!"

Yeah, Finding Dory is a Pixar movie. So you're right to assume that its big, broken heart beats loud and clear within moments of its beginning. When we hear its desperate, stumbling rhythm, our own broken hearts beat more powerfully in recognition. And we are drawn in — almost all ages, almost all moviegoers — to the hope of the film's promise: We will see some kind of reunion, reconciliation, and restoration before it's over. We want to believe. It builds our faith.

It's hard to believe that any movie — especially one stamped with the Disney brand — would have left such a huge plot thread untied and loosely wavering, like a long tendril of kelp, in the undersea currents. But Finding Nemo's central narrative question — Will poor Marlin make his way across the ocean to find poor little Nemo and bring him home? — was so compelling that our joy in its resolution was enough to send us home happy, undistracted by the fact that the memory of their traveling companion Dory remained a blank slate.

That question recently surged to the surface of our moviegoing memories, thanks to Pixar's massive marketing effort for Finding Dory. And yeah, like most moviegoers, I went for the bait of it: Hey! Why is she so forgetful? And what important things might she have forgotten?

So I was happy to be caught, reeled in, and dropped in the bucket for another voyage across Pixar's gleaming waters.

My trust in Pixar as a studio remains strong, despite a couple of disappointments along the way. (Everybody brings those sub-standard titles up, so I don't have to.) And my trust in Andrew Stanton as a director and storyteller remains unshaken. (No, I don't think the box office failure of John Carter has anything to do with the quality of the movie itself, which I found to be a lot of fun.)

I did feel some trepidation as I took my seat, though. Did I really want a sequel to what I consider to be Pixar's most beautifully realized film, its most perfect execution of its narrative strengths? Could a follow-up do anything but dilute the formula?

Well, if you go in expecting a landmark like Finding Nemo, you'll be disappointed, because what was so landmark-y — watermark-y? — about that film was its animated environment. We'd never seen anything like its sumptuous colors, its dreamy slow-motion currents, its filtered light and murky shadows. To be immersed in such a beautiful aquarium for 90 minutes was like enjoying the best bath ever. I came out feeling baptized, blinking, reluctant to return to the harsh angles and fierce lights of the cineplex. Finding Dory, by comparison, has no equivalent revelation to deliver. And yet, it makes the most of its time under the sea — and it makes much of its surprisingly frenzied adventures above the surface.

So if you want to go back to a favorite place, revisit familiar faces, and have a new adventure that allows you to explore more of that world, well... dive on in. The water's fine. Come for the supremely confident (if overly familiar) Pixar-distinct storytelling. Laugh in disbelief at what feels like a playful new recklessness in the humor. Enjoy a first-rate cast of voice actors: Ellen Degeneres manages to avoid letting her talkative character become shrill or annoying, and the supporting cast are strong without overdoing anything. (My favorite, this time around, is an unexpected contribution from Sigourney Weaver.)

And, as long as the end-credits may be, don't move. Stay for the most satisfying end-credits gag of all time.

I shouldn't have to tell you this, as it's a Pixar film, but yes: Bring tissues. You may cry. I did.

Even though it's about a fish. With a short-term memory problem.

Why did I cry, yet again, at a Pixar movie? I've never lost my memory, nor have I forgotten my way home to my parents.

But I, too, have gaps in my heart that I cannot fill. (I suspect that you do too.) I have questions I cannot answer. (So say we all.) Forgive the cryptic confession: But I know that I too have been living, for many years, in a context that is not my home, not knowing how to get out of there, and not knowing what to do if I ever did. Somewhere along the way, in the aftermath of a calamity I could not control, I was caught in an undertow of change that dragged me from my heart's natural habitat and left me "stuck" in a sort of "holding tank," unable to go back, unable to move forward, misunderstood, and taken for granted. I let my fears of the unknown persuade me to choose this out-of-placeness over the risk of seeking a place where I belong.

And somehow, this story of a fish who feels helpless and insecure, but who seizes a moment of courage and launches herself out into the unknown... it made me feel hopeful.

And that's not all I take away from Finding Dory.

I think one of the keys to this movie comes late in its running time: a conversation about the problem with relying too heavily on a plan. Dory discovers that while her life has not gone according to plan, many of life's best gifts have come unexpectedly — outside of a plan.

This feels like a sort of meta-comment on the movie. Finding Dory does follow certain conventional storytelling beats — and I, like Mike D'Angelo, was a little disappointed by the predictability of the film's "focus on the family" trajectory, and by the abruptness of its resolution. But despite the familiar narrative scaffolding, which fits what they taught in the Pixar storytelling masterclass I once attended, the most memorable joys of the journey are the things that artists undoubtedly "discovered" in the course of spontaneous play, in the progress of asking "What if?" moment by moment. Finding Dory is loaded with such happy accidents and surprises.

One of them, Hank the Octopus (sorry — Septypus!) almost takes over the movie. Flamboyant and full of surprises, he's a joy to watch. I'll bet he wasn't so prominent in early drafts. I think the artists just fell in love with all of the ways he could enliven a scene, and they kept on discovering new things they wanted to do with him. And you know what happens when artists love their own creation: The audience loves him too.

While my own journey has been one of botched and bungled plans, a few wrong turns, and many days squandered in paralyzing doubt, I must admit that many of my life's best blessings came unexpectedly along the way. And hopefully I can see them as ways that that the Great Storyteller has been prompting me to head homeward, to start finding my way back to the place that I belong. More surprises, I dare to believe, will emerge.

Master Stanton, if you're reading this: Thank you! Thank you for refusing to settle for just another sequel. Thank you for insisting on taking us to new places. Thank you for writing a story that will enrich the experience of revisiting the original. Thank you for refusing to give in to that sequel-maker's worst temptation: "Go darker." By returning to big, joyous, heartfelt filmmaking — after the industry dealt you an unjust and injurious blow — you inspire me. I, too, want to get back to the work I was meant to do. I don't want disrespect, disappointment, or calamity to have the last word in my creative life. If you can get back up and do this after the way that you've been treated, well... maybe I can too.

•

Must-Read Reviews of Finding Dory

I highly recommend that you check out these responses to Finding Dory:

There is lots to love about the film. I enjoyed the relentless creativity that seemed to find its focus when the filmmakers limited themselves to the confines of the Marine Life Institute. The new characters, all with physical or attitude issues, were a constant delight. I admired how it emphasized that both family and close friendships play unique roles in life. But what captivated me was how the story of Dory's memory loss related to my own life.

Finding Dory is pleasant, amusing, modestly clever and occasionally moving, though it never approaches the emotional or creative heights of Finding Nemo, the greatest father-son story in Hollywood animation history and one of the best American cartoons ever made.

In Memory of Peter Shaffer

This morning, a friend showed me some snapshots of her vacation in Italy. As I looked at image after image of extraordinary artistry on display in places both sacred and public, she remarked, "Nobody does stuff like that anymore. You have to wonder why."

I don't have to wonder why. Those artists were paid, even commissioned, to bring beauty into those spaces. And their work could not be easily pirated and duplicated: The one-of-a-kindness of it was precious and preserved.

Okay, sure — even in those days, artists were "bought" and exploited. The world has never been particularly kind to creatives. But the age of the Internet has brought us, in some ways, to a new low. Beauty is so available, so easily ripped off and copied, that the world has decided it's a waste to support new artists with a living wage. Why pay musicians or painters for something new? Why not just grab something off the Internet that already exists, alter it, and use it for your own purposes?

•

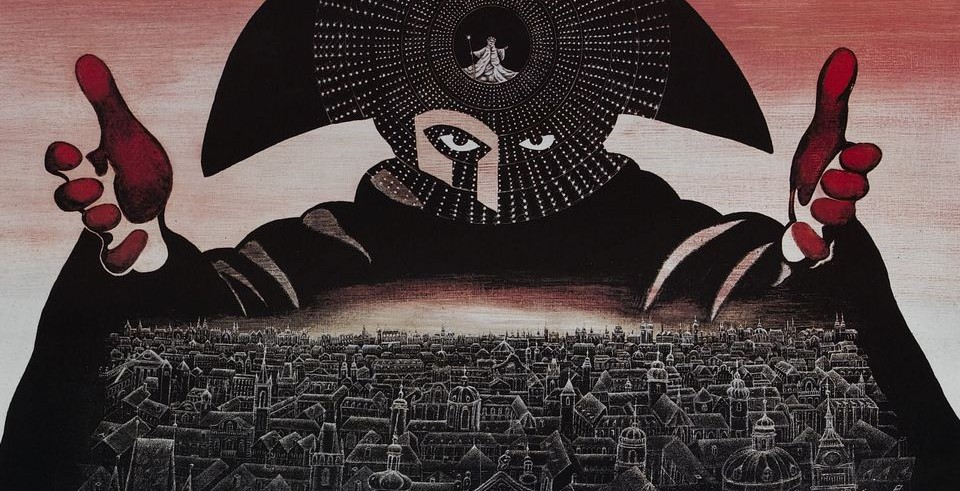

This is on my mind because I am just learning that Peter Shaffer passed away today at the age of 90.

Shaffer was one of the lucky ones whose work was celebrated enough to give him a career as an artist.

And yet, his play Amadeus, which became a film I celebrate in my book Through a Screen Darkly, is a truth-telling work about the exploitation of artistic genius. It's a lament for how true vision can go unrecognized while the visionary lives, and an acknowledgment that great work is often discovered and appreciated only when the inconvenient artist is no longer with us (if that work is ever discovered at all).

Amadeus reinforced for me what the Scriptures mean when they say that God shames the proud by raising up the humble. The Mozart of the movie is a foul-mouthed, bawdy, womanizing alcoholic. He's everything the self-righteous establishment refuses to accept. But he's gifted with vision that opens the heavens so that anyone — anyone — can hear echoes of the glory of God. That's God's way of saying that we can't earn divine favor or win true vision like a prize. That's God's way of demonstrating unconditional love and grace, so that no one has any right to boast.

In Amadeus, how does the self-righteous "expert" on composition respond to evidence of God's "unfair" economy? Like the religious leaders scowling over the devotion inspired by Jesus and his apostles, he's consumed by jealousy and bitterness. In the end, the real genius lies in ruins, while the mediocre and self-righteous Salieri snarls in resentment.

It would be a complete tragedy, except that beauty goes on doing its work, calling us all to pay attention to the source.

Amadeus remains one of the most influential works of art in my life. It taught me to appreciate wisdom and beauty wherever I find it. It affirmed my suspicions that God's most glorious revelations will often come from the most unlikely people — people who whose voices would be silenced at Christian schools for their troublemaking, people who would be rejected from church congregations for how they smell or how they won't "clean up." And it reassured me that even if I pursue excellence in my art, I am not guaranteed appreciation, respect, or even a decent income.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NlpxjBgG-7E

While historians will pick Amadeus apart, Shaffer's fictional tribute to Mozart offers profound insight into how and why the world stifles creativity, exploits creative people, and celebrates mediocrity.

Mozart's imagination is disruptive — it tells us that we haven't figured everything out. Mozart's imagination threatens so-called experts — it reveals them to be as petty and as prideful as anyone. Mozart's imagination shows us that beauty can be found everywhere, regardless of our hierarchies. And yet, alas, Mozart's imagination sets self-interested human beings to work in figuring out how they benefit from someone else's genius. Thus, Mozart's imagination ends up forced into the service of crooked systems.

Shaffer's Mozart could amplify "the voice of God." And so he was persecuted by the jealous, exploited by the powerful, and deprived of the support he needed.

•

Whether or not Shaffer's Mozart is anything like the real Mozart, there's no way to deny that the plight of this Mozart correlates to the plight of gifted musicians — gifted artists — today. I know so many people who invested heavily in artistic educations in order to refine and strengthen their art, and who now spend most of their hours doing something entirely different because even their best artistic efforts wouldn't put food on their table or a roof over their heads.

I think of Amadeus whenever I'm reminded that I can either apply myself to my art or earn a living wage.

I think of Amadeus when I hear Christians condemning my favorite artists and entertainers for their moral failings. "What? You like that guy's movies? You like that woman's music? Do you know what kind of life he lives? Do you know what I read about her?"

I think of Amadeus when I see commercial entertainers stealing great ideas from unappreciated masters (who never made a "hit") and turning them into box-office success.

And the exceptions? The artists who do find a way make a living off of their work? Don't kid yourself — most of the art that plays on big screens is there because someone other than the artist is making most, if not all, of the money. The music that's promoted and marketed? It may come from somebody whose work has earned them "success," but it's likely that they're still owned by a company who receives most of the reward.

Those artists who refuse to play capitalism's games usually end up having only as much time for their art as most people have for a "hobby" — they have to do other kinds of work if they want to survive. And the world is deprived of what God might have revealed through their work.

This is the devil's world, for now. He's doing all he can to keep good artists down, to stifle beauty, and to turn what glory is revealed into a "profitable" opportunity.

But he doesn't have to win every time.

Who in your life today would give the world beauty and imagination if only they had more support? Who spends their days laboring on something other than their art in order to make ends meet? How many musicians, novelists, and painters might bless the world in life-giving ways if they were compensated for their work?

Amadeus tells the far too familiar story of an artist who became a living sacrifice for the sake of revelation, and ended up exploited, suppressed, ruined, or all of the above. Watch it again, and see if he reminds you of anyone you might know who labors in the fever of a vision, and who goes overlooked, unappreciated, or exploited. Let this movie work on your heart. Think of the artists in your life, those who have given you glimpses of something beautiful and true, and give them a note of encouragement today. And consider donating to their futures, even if all you can spare is a little each month.

Let's see if we can turn loose a little beauty that doesn't have strings, or parasites, attached.

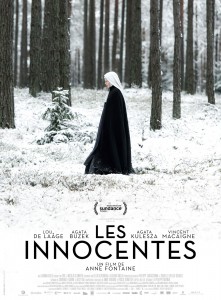

The Innocents (2016)

Name one movie that is

1 — directed by a woman,

2 — filmed by a woman,

3 — focused primarily on female characters, and

4 — deeply concerned with matters of faith.

I can think of many films directed by men, and focusing on men, that rigorously wrestle with questions about belief and doubt. I grew up with them: Chariots of Fire, A Man for All Seasons, Amadeus. Consider Terrence Malick's recent string of films, or Xavier Beauvois's Of Gods and Men. Later this year, we'll finally have Martin Scorsese's much-anticipated adaptation of Silence.

But The Innocents is a remarkably rare event.* It might rightly be called Of Gods and Women. What a tremendous contribution Anne Fontaine has made to cinema's library of films about faith!

Fontaine takes us back to 1945, one of cinema's most filmed and familiar chapters, but then veers off the well-worn paths that lead to battlefields and parks her cameras at two unfamiliar locations: a convent where Benedictine nuns (Polish) are praying, singing, and suffering, and a camp in Warsaw where the French Red Cross are working to help wounded soldiers.

As we arrive at the camp, so does one of the nuns. She's begging Mathilde, a young doctor (Lou de Laâge), to risk the fury of the camp commander and come back with her to the convent to save a dying woman.

What Mathilde finds at the convent, though, is much more than a pregnant woman in trouble. She finds a traumatized community, one devastated by the war crimes of the "liberating" Red Army. And for these believers, what they have suffered brings an added terror — they believe that God will find them guilty of corruption and send them to hell. Guilty of what corruption? Well, most reviewers will spell out these things for you, but I'm grateful that I had the experience of learning the nature of this story's horror from the film itself, so I'll stop there in my plot description.

Suffice it to say that these women have every reason to be heartbroken. And so the film admirably invites us to live in the tension of these questions. While moviegoer sympathies are more likely to settle within Mathilde's skeptical and agnostic perspective on the situation — several scenes lean too far in to anointing her as the One Reasonable Human Being — the nuns are portrayed with respect and compassion. And as we watch certain wartime evils rise up and tear Mathilde's reliance on reason to shreds, we begin to feel, with Mathilde, the allure of Christianity's consolations.

The poster for The Innocents rightly celebrates the film's most cinematic idea — the black and white of a nun's habit within the the black and white of a snowbound woods. It suggests that the world itself is a figure that suffers like one of these struggling sisters, caught in a quandary of faith and doubt, the very clash of its colors a manifestation of being torn between opposing forces.

The poster for The Innocents rightly celebrates the film's most cinematic idea — the black and white of a nun's habit within the the black and white of a snowbound woods. It suggests that the world itself is a figure that suffers like one of these struggling sisters, caught in a quandary of faith and doubt, the very clash of its colors a manifestation of being torn between opposing forces.

That is the image I will remember the most. Beyond that , The Innocents is a movie of faces. Faces that have witnessed horror. Faces reflecting a struggle of failing faith. Faces wide-eyed and mystified by faith. Faces torn by fear and denial. And the shining eyes of Lou de Laâge, which mirror back to us our own stages of incredulity, horror, anger, grief, and fleeting joys. (This seems to be a coronation year for Lou de Laâge as France's brightest new star — she can also be seen currently starring opposite Juliette Binoche in The Wait (L'Atessa).) By the end of the film, I was still struggling to remember the nuns' names, but I almost didn't need them — the faces told myriad stories, and we are invited to find ourselves within many different experiences of faith and doubt.

Having said that, I must also note that this film that is much stronger in its characterization, performances, and narrative than it is in its imagery. I wish that Fontaine and her cinematographer Caroline Champetier showed a more poetic visual sense. But I love Champetier's reliance on natural light; the film's shadowy passageways and radiant oil lamps; the occasional and startling blaze of flames in a world painted in blacks, whites, and greys. And I love the film's judicious use of music, giving us long silences and an intimate experience of the convent's sung prayers.

I felt a twinge of disappointment when the plot took a more conventional, suspense-raising turn just past the halfway point, one that makes the film feel more like a "movie" and less like a complex engagement with fundamental epistemological questions. (Trying to avoid spoilers here, but one character does reveal a streak of villainy that suggests the screenwriters wanted more suspense, or somebody for the audience to boo.) And there are times when the film tips the scales too far in Mathilde's direction, characterizing enlightenment as the act of casting off abandoning "organized religion" in order to "really live" in the world outside. (In that sense, this might make an interesting double-feature with 2014's black-and-white wonder Ida.)

But for the most part, The Innocents is a remarkably respectful film, and one that brings a large cast of female characters to life more fully than moviegoers are accustomed to seeing. What's more, I was delighted to see one of the film's only male characters defy my expectations and become a memorably nuanced individual.

I saw this at the Seattle International Film Festival, in a packed house, and the audience gave it a warm and appreciative ovation at the end. That was exciting to witness in this oh-so-"unchurched" city. Thanks to my friend Alissa Wilkinson (Christianity Today) for encouraging me to make the time for this one during a week when I really couldn't afford the time for a movie. I'm glad I did — it was well worth it. We're in Month #6, and for what it's worth (this hasn't been a particularly impressive year yet) — this is my Movie of the Year so far.

*Note: I can think of one other recent film that fits the three criterion listed at the beginning of this review: Vision – From the Life of Hildegard von Bingen, which deals with the tension between religion and science, faith and fear, legalism and freedom. But I'm guessing that you haven't seen it, as it played very few places. Another reader has suggested Higher Ground, a film that is about a woman on a challenging faith journey (but which didn't particularly work for me). Perhaps you can think of another.