The great Nicolas Cage shows up for Dream Scenario, but is the movie worthy of him?

An early draft of this review was originally published on November 27, 2023,

at Give Me Some Light on Substack, months before it appeared here.

Subscribe, and you'll read many of these reviews while the films are still breaking news!

Diamond rings and all those things

They never sparkle like your smile

And as for fame, it’s just a name

That only satisfies you for a while…

You say you hunger

For something you can’t get at all

And love is not enough anymore…

If I was king for just one day

I would give it all away

I would give it all away

To be with you…

— Thompson Twins, “King for a Day”

For a movie about the world’s most uninteresting man, surrounded by a supporting cast of even less interesting characters — yes, I realize that’s a contradiction, and nevertheless it’s true — Dream Scenario sure plays around with a lot of interesting ideas!

Dream Scenario, the A24 Flavor of the Month from writer and director Kristoffer Borgli, is a wise and witty satire about America’s cultural obsession with “going viral,” the fleeting and fragile nature of fame, and the cost of being a household name if the public turns against you. For starters.

This ultimately underwhelming psychological thriller follows a frustrated academic, Paul Matthews (Nicolas Cage). Paul suffers from a sort of mediocrity that makes him a not-so-innocent bystander on the stage of life. He’s a ho-hum husband, an extremely uncool dad, a sort of “blank” in a world of exclamation points. His lack of agency doesn’t just make him uninteresting; it makes him annoying. He’d be lost if it weren’t for his longsuffering spouse Janet (Julianne Nicholson), who seems to still love him for who he is. Otherwise, Paul shuffles through every day yearning to be admired by his daughters, longing to be respected by his colleagues, and dreaming of being recognized for his studies on the psychology of ants. And he gets… wait for it… antsy when another academic infringes on what he considers his intellectual territory.

But it’s hard to be celebrated for one’s publications if one can’t find the will to sit down and start writing. And, like another character Nicolas Cage played in Charlie Kaufman’s provocative Adaptation, this avatar of Kaufman-esque insecurity and awkwardness just can’t bring himself to compose the pages that might finally put him on the Map of the World’s Somebodies.

In my creative writing classes, we always get around to talking about “the Story Spine,” an elementary formula that can be identified in anything we recognize as a story. There’s the situation: the “Once Upon a Time…” line. There’s the normalcy: the “Every day…” line. And then comes that most important moment, the thing we call the Inciting Incident. It’s the line that says, “But one day….”

The Inciting Incident of Dream Scenario, the big idea that sets the primary drama in motion, is this: Inexplicably, Paul starts appearing in everyone’s dreams. Everyone’s. His face is the face of an enigmatic dream epidemic. And he’s catapulted to global fame almost overnight. Fame for doing… nothing. He’s just suddenly everywhere.

It’s a great twist, a brilliant premise for the age of memes and TikTok influencers. Paul is recognized by everyone, his world is turned upside down, and he’s appearing on talk shows. Why? For doing next to nothing. For appearing to do something. His bored and despairing students suddenly find him interesting.

What comes next in the Story Spine? A sequence of steps that we call “And because of that….” Each of these steps represents a chain reaction set in motion by the Inciting Incident, a series of ripple effects and consequences leading to the inevitable step that we call “Until finally…” when everything reaches a point of resolution or collapse.

One of the most significant “And because of that….” steps in Dream Scenario is this: Slowly accepting and them embracing his fame, Paul starts looking for a way to exploit the moment: He scrambles to secure a cart (that is, a book deal) that he can place before the horse (that is, any actual writing). Maybe Paul’s moment has finally come.

And who can blame him? Let’s face it: We all want to be seen as special. We crave the flattery of positive attention. Here’s his chance, in the spotlight on the world stage, to reveal what he really has to offer.

But we also know that for every cultural idol who has earned our respect and admiration, there are a hundred more who have become household names for reasons that are questionable at best. Has Paul prepared properly for the moment? Does he have something to offer?

And there’s another dangerous question on the table: It’s no secret that a lifetime of good work can be flushed down the cancel-culture toilet if the X-Ray of media attention discovers (or fabricates) a celebrity’s character flaw. As Suzanne Vega sings, “When heroes go down / They land in flame / So don't expect any slow and careful / Settling of blame.” Is Paul a person built to survive the searing scrutiny of global fame?

Michael Cera — perfectly cast in view of the fact that he’s often chosen to play human “blanks” — plays an opportunistic marketing agent named Trent. (Because it’s spelled kinda like… “Trend,” I guess?) Trent is the first marketplace predator to pounce on Paul’s unlikely “influencer” potential, hoping to sign him to advertising deals with a cola company. Of the film’s many “moves” to score points of social commentary, this may be the sharpest, making us think about how many celebrity spokespersons we listen to per day, and wonder why we find any merit at all in their endorsements of anything. (I write this as another pizza commercial with Shaquille O’Neal is playing on my TV.)

Paul doesn’t want to become a spokesperson for anything. He wants to be known for who he actually is and what he actually cares about. But nobody is really interested in either of those things. Love may be attention — thank you, Lady Bird — but not all forms of attention are love. It takes Paul a while to realize that people are only interested in him for a couple of reasons: For some, he occupies the spotlight they crave for themselves. For others, his fame represents a kind of currency, and they want to find a way to cash in. I’m reminded of the wisdom of that clear-eyed seashell in Marcel the Shell With Shoes On: There’s a difference between an audience and a community. Paul has stumbled into one, when he needs to do the work necessary to play a meaningful part of the other.

Wow — on paper, this sounds like such a great movie. Kristoffer Borgli has so much of what he needs here to deliver a great film.

First, he has such a promising premise. He sends Paul along a narrative trajectory rich with opportunities to mirror back to us our own complicity in the absurdities of pop-culture exploitation. Paul enjoys the kind of fame that most TikTokkers’ dream about. But then, he ends up suffering the worst kind of consequences that most fame-seekers ignorantly risk… and many, unfortunately, find. Media spotlights can glorify those who seek them and those who accidentally stumble into the glow. But they can also burn the same “lucky winners” — great artists and soulless opportunists alike — into ash in a moment, whether they have made a mistake that deserves such judgment or not.

At its best, Dream Scenario drives us to ask important questions:

- Do we really want to be famous? What do we want to be famous for? And what purpose do we hope that fame will serve?

- When we look around, do we see fame bringing true health and human flourishing to the people we admire? What does living in the spotlight cost a person? Are we ready for that?

- Wouldn’t it be better just to do good work consistently and quietly? Do we really want to run the risk of bankrupting our whole life’s work and the security of our loved ones, inviting a plague of dehumanizing surveillance?

Secondly, Borgli has one of Hollywood’s most recognizable marquee names in the lead role. Nicolas Cage may be the perfect star for this part, given that his career has been a rollercoaster of the highs and lows of fame. He’s had top-billing in prestige pictures. He’s won an Oscar. He’s had romances and breakups that have been tabloid cover stories. His media history is one of achievement and embarrassment. But we can’t escape the question that comes with any new Cage movie: Which Cage are we going to get? The one who just shows up and cashes in? Or the one who does the work?

Good news: Dream Scenario stars the Great Nicolas Cage. For more about 90 of the film’s 105 minutes, Borgli serves up a sequence of intriguing scenarios, but they only work because of Cage’s creativity. Given the challenge of playing someone who isn’t interesting, Cage does something interesting with every single scene. Since the comic performances that made him famous in the late ‘80s, his flair for hilarity has only returned on rare occasions like Ridley Scott’s Matchstick Men, Spike Jonze’s Adaptation, and Werner Herzog’s Bad Lieutenant Port of Call New Orleans. But he’s as surprisingly funny in Dream Scenario as he was surprisingly dramatic and endearing in 2021’s Pig. Let’s get him yet another Oscar nomination, Academy!

Julianne Nicholson, playing Paul’s longsuffering wife, is lovely. (I’ve been a fan of hers since Tully way back in 2000, and I’m still reeling from her fierce performance in Mare of Easttown.)

But that’s where the good news stops. The supporting cast, given half-cooked characters with nothing interesting to offer, aren’t given much of an opportunity to make memorable impressions. And it’s not for lack of talent: The film squanders the presence of Tim Meadows (who isn’t allowed to be funny?), Dylan Baker (who isn’t given a single interesting moment to play?), and Shithouse’s Dylan Gelula (whose character, in a more talented screenwriter’s hands, might have stolen the show?) I’m most frustrated to find Amber Midthunder, so kinetic and compelling in 2022’s excellent Predator prequel called Prey, given nothing to do at all except make half the audience say “Wait—why do I recognize her?”

Perhaps the most surprisingly disappointing aspect of the film, given that it’s from the studio that gave us The Green Knight and Everything Everywhere All at Once, is that Borgli doesn’t conjure a single compelling image. I wouldn’t call Dream Scenario “a bad dream,” but it sure is a bland dream. If anyone finds images from this movie memorable, it’s because a situation is interesting, not the way that it’s captured. We get a shot of crocodiles cornering a young woman; another of a girl suddenly levitating; a few of Paul viciously attacking people; another of young man being stalked by a blood-red devil. And yet, while the prospect of creating these images must have seemed exciting, none of them — not even the one in which David Byrne’s giant suit from Stop Making Sense makes an appearance — are particularly striking or suggestive. Very few filmmakers know how to achieve a truly dream-like “surreality” — and I don’t think Borgli has David Lynch’s number in his iPhone contacts.

Thus, moviegoers are likely to come away from Dream Scenario talking about Cage or offering their various takes on the film’s obvious zeitgeist commentaries. But it’s the pictures in motion pictures that make the most lasting impressions. And on that count, what Dream Scenario could have been is something we can only dream about.

And yet…

As underwhelmed as I am by the last fifteen minutes of Dream Scenario, I’ve been thinking about it a lot. So much of what it reflects back to us about our own fame-obsessed culture is worth taking to heart.

In my twice-annual sessions of Imaginative Writing, my intro-to-creative-writing class at Seattle Pacific University, I occasionally encounter a student who has decided they want to “be a writer.” They tell me about their favorite books or screenplays — usually popular franchise stories with adjacent movies and games. They tell me they tried to register for my Advanced Fiction Writing class, but discovered that the Intro course was a pre-requisite, and so they’re jumping through this inconvenient hoop. What they’re really interested in, they say, is getting published.

Experience has taught me to smile, be respectful, and quietly insist that the introductory course is not just a hoop to jump through. My writing classes are about learning and practicing the disciplines that lead to strong writing: craft exercises, freewriting, ambitious reading, small group workshopping, and revision, for starters. These will help them discover that writing can be a richly rewarding way of life — an abundant and meaningful life! — whether or not it leads to publication. (I love Annie Dillard’s anecdote in The Writing Life about a writer who was approached by a student and asked, “Do you think I could be a writer?” “‘Well,’ the writer said, ‘do you like sentences?’”)

Publishing? That’s a whole different subject. I remind my students that a whole lot of terrible writing gets published, and a whole lot of great writing is rejected by 70 publishers or more before it finds a home… if it ever finds a home. I tell them about the five year span in which I wrote five books under contract, and how they were some of the most stressful and punishing years of my life, nearly burning me out as a writer. They blink, and it’s clear to me that I must sound like one of the adults in a Peanuts cartoon. They’re not really hearing me. Their mind is already made up: They’re in love with the idea of being known as a writer, and not at all ready for the rigors of writing. Most of them have no idea what that involves. (Hint: Malcolm Gladwell wasn’t far off when he wrote about “the 10,000 hours.”)

Within a few weeks’ time, these students who have decided to be writers tire of actual writing. And it turns out that the stories they felt so compelled to tell were just a grab-bag of familiar twist-ending formulas: “My narrator was dead the whole time! Surprise!” “The protagonist dies of a car accident at the last moment — nobody saw that coming!” “The food they were eating… it was people!” “Surprise! The whole thing was just a dream!”

Perhaps I sound cynical. I’m not. I find impressive writers in these classrooms too, and sometimes one of those ambitious, career-minded dreamers actually turns out to have real talent. I just graded a stack of revisions in creative nonfiction, poetry, and fiction, and I recognize those who are likely to write for the rest of their lives: They are enjoying the work of revision. I’m always willing to be surprised.

What troubles me are not the ambitious, career-minded students. What troubles me are the forces that so often shape their expectations and their preoccupations with a fast-track to fame. They don’t understand just how dangerous our desire to be recognized, celebrated, and validated can be. Attention, like any exciting drug, can become an end in itself and distract us from meaningful work. It can cost us our privacy. It can cost us our friendships and families. It can test our integrity. Typically, these dreamers don’t realize what it takes to win a cultural spotlight, much less to sustain that kind of attention once you have it. They don’t know what can happen when the heat of pop-culture glory hits you and reveals just how much — or, more likely, how little — you’re ready to offer. And they forget that the simple fact of being a fallible human paints a target on your chest, so that simple stumbles that used to be incidental have become an invitation for public condemnation and scorn.

https://youtu.be/q3x9iUL-74w?si=cso28RYJcgLAphqK

We’re surrounded every day by famous figures like Dream Scenario’s protagonist who have become popular for frivolous reasons. But even those who have earned their way to fame by their meaningful contributions to society are vulnerable when they stand before a fickle and mercurial public. In an ideal world, audiences would focus on the work, not the maker. “There is no such thing as an artist,” writes Annie Dillard in Holy the Firm. “There is only the world, lit or unlit as the light allows. When the candle is burning, who looks at the wick? When the candle is out, who needs it?” What a world it would be if we heeded those words and gave up this circus of celebrity nonsense. But that’s not the world we live in.

During the few years in the late 2000s when all of my publishing dreams were coming true, and I was thrilling at the sight of my own books at the front of Barnes & Noble bookstores, something happened to me. My relationship with writing changed. I became much more focused on engaging audiences, much less focused on the writing itself. And I nearly collapsed chasing every opportunity to promote the books, marketing and marketing, doing interview after interview, scrambling to try to sustain the momentum of potential. I wrote more hastily, more desperately, as the demands of the Machine took more and more of my energy and attention.

In Dream Scenario, Paul hasn’t even begun to do the academic writing that he wants the world to know him for. But it’s not just his writing — or, rather, his dream of writing — that suffers. He’s also failing to live up to his potential as a father, as a husband, as a member of a community. The hype of his success is filling up his life with even more nothingness. Perhaps if he were a human being first and a celebrity second, he might have some actual wisdom and work to offer when this almost-arbitrary spotlight of celebrity finds him.

That may not be the wisdom that Dream Scenario intends to impress upon us. (To be honest, given the film’s rather haphazard conclusion, I’m not exactly sure what the film ends up hoping we understand.) But it’s the wisdom that has me replaying the film in my mind.

Merriam-Webster has chosen the word authentic as the 2023 Word of the Year. And it’s a word that seems to me to be at the heart of Dream Scenario’s questions. Yes, Paul Matthews has gone viral. But does he have what it takes to do something worthwhile with that attention? Does he have what it takes to stand strong if and when the audience turns against him?

If that merciless spotlight ever swings back around to me again, I hope I’m wiser. I hope I’m prepared to make something more meaningful of the moment. And if it doesn’t? That’s just fine with me. It’s probably for the best.

The Holdovers lives up to its name

An early draft of this review was originally published on November 12, 2023,

at Give Me Some Light on Substack, months before it appeared here.

Subscribe, and you'll read many of these reviews while the films are still breaking news!

“You might try The Holdovers,” I heard myself saying to one of my former students who stopped me in the hallway to ask for a film recommendation. I’m not a big fan of Alexander Payne’s films. I find that his work tends to zigzag between off-putting cynicism and a sort of desperate sentimentality. But there’s a lot to enjoy in this one.

“I saw the trailer,” the student replied. “It’s about a professor, right? At a boys’ school? So, it’s like a new Dead Poets Society?”

I don’t remember what I said. (I was on my way to class, in a hurry, as usual.) If I’d had time, here’s what I would have said:

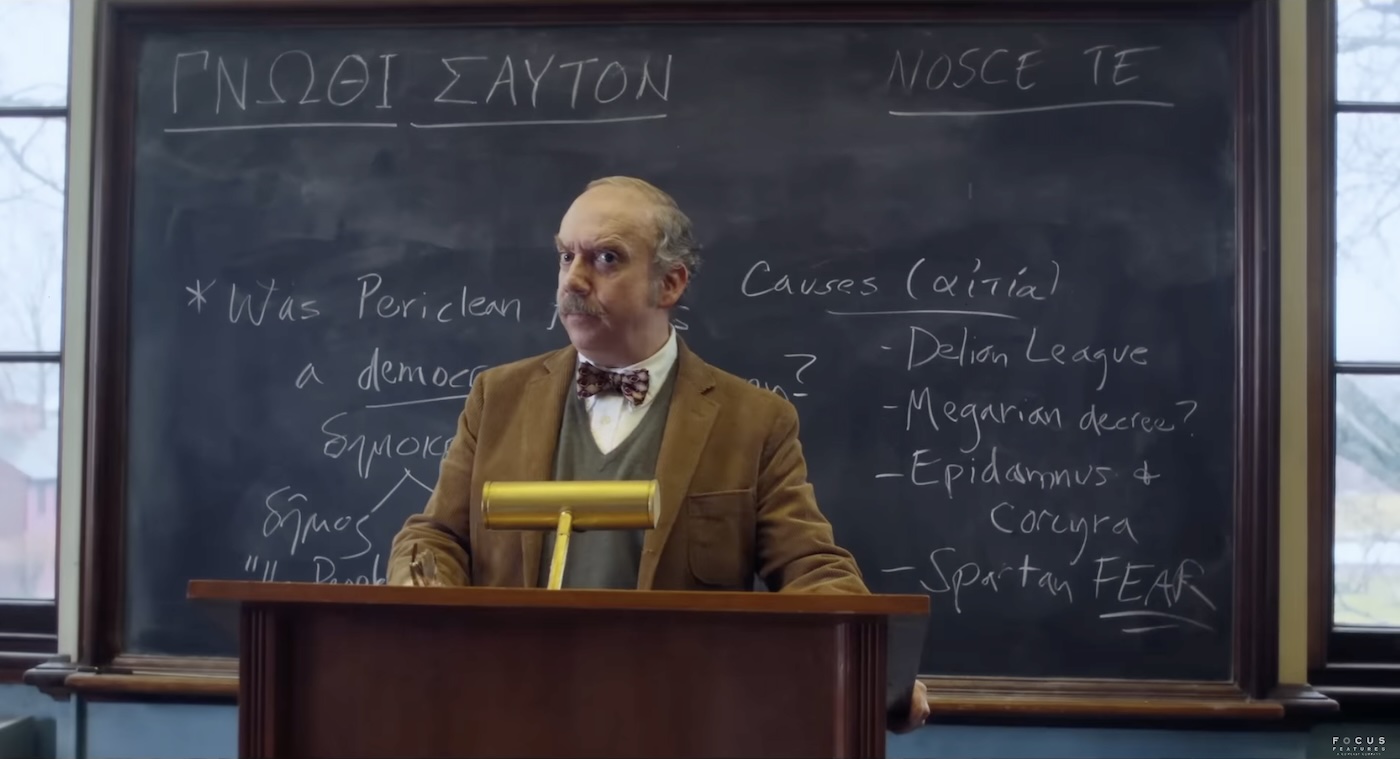

The Holdovers certainly feels like it could be taking place in the same world as Peter Weir’s classic boys’ school drama. Dead Poets was set on the campus of a Vermont school called Welton; The Holdovers is set among the traditional brick buildings of a New England boys’ school called Barton.

But the contrasts are more interesting than the similarities. Dead Poets took place in 1959, as Elvis was on the rise and The Beatles were about to blow up the pop culture world. Counterculture was about to challenge and change American culture’s strict norms. The Holdovers, by contrast, takes place in 1970, and the boys of Welton are fighting to avoid madness, trapped in a world prescribed by their controlling parents and an even more controlling patriarchal academy full of faculty who grumble about the death of culture.

The narratives follow arcs that are thematically complementary but hierarchically flipped: Weir’s film is about an unconventional teacher (played by the unconventional Robin Williams) who challenges tradition and champions creativity, poetry, and passion. Payne’s film is about a maddeningly legalistic classics professor (played by the wonderfully curmudgeonly Paul Giamatti) who, stubbornly rooted in tradition, butts heads and locks horns with students who would challenge him to become more creative, more spontaneous, more open-minded. The pioneering teacher of Dead Poets clashes with his institution in hopes of saving his students from cultural suffocation. The old-school prof of The Holdovers… well, he is the institution — so much so that even his colleagues might recommend he be institutional-ized. He’s the one who needs saving.

For the first hour, the story unfolds as a three-strand braid, following characters stranded on campus during the holiday break:

Giamatti’s Professor Hunham, his casual conversation as peppered with Latin phrases and literary allusions as his lectures, staggers around the corridors “babysitting” the titular “holdovers” — the boys who have nowhere else to go. It’s clear that his obnoxiousness is a front for some kind of deep hurt, but the nature of that burden won’t become evident until the trials of this purgatorial season wear him down and expose the wounds.

One of the stranded, a smart but obviously wounded young man named Angus (the very impressive newcomer Dominic Sessa), hates Hunham as much as the other students. But he’s quite possibly the most observant and mature of the bunch. And before long he’s testing his intolerable supervisor’s patience not so much to punish him as to figure out what makes this grouch such a monster. (It’s obvious that Angus, too, is destined to reveal dark secrets.

Meanwhile, both Hunham and Angus are fed by Mary Lamb (Da'Vine Joy Randolph), the head cook and administrator of the school cafeteria. The source of Mary’s hurt is obvious: Her young son was the only Barton boy sent to fight in Vietnam, lacking the privilege and prejudicial protection of the majority. Mary’s discernment is as sharp as any of her kitchen knives; she sees through Hunham’s bluster and she knows what Angus needs.

(I cannot deny that filmmaker Chad Hartigan has hit the nail on the head in his Letterboxd notes about this one: “Da'Vine Joy Randolph gave an electric, star-making performance in Dolemite is My Name that didn't get her a sniff of awards attention but as soon as she plays the help in a white people movie the Academy is gonna take notice.” [Sigh.] How long, O Lord, must we sing this song?)

Over the course of their brief but torturous (and snowbound) detention on campus, they will have no choice but to cope with one another. What they do choose, however, is surprising: Hunham tests the electric fences that pen him in. Hunham chooses to loosen his famously unforgiving standards as he begins to care for the young man. And Mary will give her grief something to do: She’ll provoke Hunham to emerge from his shell and start discovering the world through the frame of the television. What’s more—she’ll support Angus in pursuing what he really needs. Their conversations and collisions will lead them on episodic adventures: to a hospital emergency room, to a bowling alley, to a Christmas party, and beyond.

The farther they go from their campus routines, the more they learn about each other’s secrets, and, well… the more the movie begins to test our patience with a sequence of shamelessly tearjerking scenes that feel less inclined toward literary integrity and more inclined towards easy crowd-pleasing. It’s bound to be the kind of movie that earns a bunch of Oscar nominations but then quickly becomes just another title on Payne’s hit-and-miss IMDB record.

Yes, unfortunately, The Holdovers really lives up to its name. It keeps us at least 15 minutes too long — I might go so far as to say 30 — and I counted at least three moments where I might have faded the film out, subtly and quietly. But Payne keeps prodding it further, as if he’s never quite satisfied with any of these understated moments but wants to go for the Oscar-moment jugular, concocting some kind of confrontation that will push all the right buttons.

And that’s a shame, because I enjoy the world he’s crafted here. It’s a film critic’s responsibility to recognize this aesthetic as an homage to 1970s Hal Ashby classics, right down to the folk-song interstitial flourishes. (Damien Jurado is a surprisingly effective stand-in for Cat Stevens — so much so that we didn’t really need an actual Cat Stevens number, but we get that anyway.)

But Ashby films always remain rebellious enough, earnest enough in their anti-establishment impulses, to avoid ever surrendering to corporate influence. And Payne’s film feels anxious about achieving heavy buzz, and so it ends up reminding me even more of early '90s Oscar bait like Scent of a Woman, scenarios that build toward a character taking an heroically moral stand in a moment of extreme pressure, something to make us cheer and cry.

Come to think of it, Dead Poets does this too, but it does so in a way that leaves us uncertain about the consequences. For all we know, several of those boys will get kicked out of school. And Robin Williams’ Mr. Keating might get hit with lawsuits. By contrast, The Holdovers ends a little too neatly for me,

Sideways remains the only Alexander Payne film where the tension between cynicism and sentimentality has mostly worked for me (and even that movie has a scene that I count a jarring, ugly misstep into cruel caricature). This movie errs in the other direction. It never feels dangerous; instead, it feels a little too sentimental.

But I'm inclined to say this one is still worth seeing for its playful homage to a very specific slice of cinema history, for its three lead performances, and for a few very good scenes that come before those last, long 30 minutes.

Beauty and the rock'n'roll beast: Sofia Coppola's Priscilla

An early draft of this review was originally published on November 8, 2023,

at Give Me Some Light on Substack, months before it appeared here.

Subscribe, and you'll read many of these reviews while the films are still breaking news!

Does the camera love Cailee Spaeny’s Priscilla Presley more than any young protagonist in Sofia Coppola’s filmography?

That would be quite a claim to make. Let’s see:

- Kirsten Dunst’s cloistered Lux Lisbon is angelic and ethereal in The Virgin Suicides (1999);

- Scarlett Johansson’s Charlotte in Lost in Translation (2003), tender and pensive in dark hotel rooms and the amber glow of hotel lounges.

- Dunst is a canvas for mischievous makeovers as Marie Antoinette (2006).

- In Somewhere (2010), Elle Fanning’s Cleo has the wide-eyed curiosity of a four-year-old in a teenager’s undecided definition.

- Audacious trespassers and thieves, fronted by Emma Watson strong-willed ringleader in The Bling Ring (2013), invest so willfully in superficial surfaces that the void behind their flirtatious gazes is funny and frightening.

- And the candlelit frills-and-lace dresses of Fanning, Dunst, and Nicole Kidman in The Beguiled (2017) seem like a wounded soldier’s morphine-induced dream.

So many incredible actresses. So many indelible performances. And all of them captured with reverence through Coppola’s loving lenses.

Nevertheless, I’m going to say yes: Spaeny, convincingly playing a 14-year-old dressed up to look 24, and respectfully adored by cinematographer Philippe Le Sourd, is so magnetic in every scene of Priscilla that even Jacob Elordi’s Elvis almost dissolves when she’s onscreen beside her.

Right away, Coppola has her audience right where she wants us: We want to intervene and save Spaeny’s Priscilla from the cyclone of celebrity that is going to carry her out of her Kansas and into Elvis’s Oz, while at the same time we cannot wait to see how fame and fortune transform her into an influential icon envied by women twice or three times her age. This is, as they call it in this buzzy business, “a star-making performance.” And that adds yet another layer of conflict to the proceedings: We’re watching Spaeny’s ascent to superstar status even as she brings to life a cautionary tale about that very thing.

From the moment we see her in the diner at the film’s opening — lonely, vulnerable, a tangle of teenage uncertainties, thinking she knows better than her parents (as we all did at that age), and failing to conceal her restless longings — we’re hooked. There’s a Disney Princess light in her eyes. We have no doubt that a global superstar, one so worshipped and successful that nobody dares deny him anything, will notice this walking “I Want” song. We have no trouble believing that — even though (cue the Michael Caine accent) she’s only 14 years old! — the Beast will seize upon the Beauty as his ideal and lock her up in his palace like a trophy. It’s discomforting because we disapprove of this before it happens, and yet we ourselves cannot wait for it to happen. Spaeny has the rare and mysterious power that defines iconic actresses, and we’re already longing to see all of the versions of Barbie to Elvis’s Ken that she can become.

This trouble — hating what’s happening even as we’re mesmerized — sticks with us through the whole two hours: It’s painful to watch as Priscilla’s parents (Ari Cohen and Dagmara Dominczyk) lose their feeble resolve to protect their daughter from the charms of the circling celebrity. They’re easily seduced, as she is, by Elvis’s magnetism. And while it’s one of cinema’s most familiar tragic story arcs — a young woman doomed to serve as a dress-up doll for a manipulative and self-destructive Svengali in a world made for men — it’s as potent and relevant as ever.

In Coppola’s lush, dreamlike recreation of Priscilla Presley’s own testimony (the film is based on her own memoirs), we watch the young, starstruck, and frightfully naive young Priscilla Ann Wagner become the live-in (and, thus, housebound) girlfriend of “the King of Rock and Roll”; wander those Graceland corridors in a downward spiral of debilitating loneliness and uncertainty; demand reassurance after his early affairs come to light; win his worthless vows of devotion and fidelity; and become the mother of his child. Her charismatic controller orders her not to change, but we know it’s impossible: He’s captured a human being in her most transitional and formative years. Ever so slowly, she will writhe in the realization of the trap into which she has walked so willingly, so eagerly, so naively. As her self-knowledge grows, so does her doubt about his declarations of devotion — and this kindles a dissatisfaction over the freedoms he enjoys but she is denied. She inevitably becomes for Elvis a conscience, so long as he’s willing to tolerate one; and thus, she’s an intensifying reminder of his vanity.

We should have seen this movie coming: it’s the perfect match of subject and artist. Sofia Coppola makes movies about young women who live in varying states of isolation, their perspectives and priorities shaped and misshapen by the bubbles in which they grow up.

It was a bubble of parental over-protection and control in The Virgin Suicides. Bubbles created by show business stranded the protagonists of Lost in Translation and Somewhere. Politics, patriarchy, and wealth kept Marie Antoinette in captivity. The women of The Beguiled are stranded in wartime isolation, but they’re also bound up in the systemic misogyny of their culture.

In all of these contexts, film critics keep on finding good reason to speculate about Coppola’s attraction to such stories. After all, she grew up in a sort of fantasy world herself, the daughter of Francis Ford Coppola and a part of that American show business dynasty. Her movies have always seemed like testimony by way of creative analogy. It’s clear that she’s wide awake to the alluring and dangerously distorting effects of such privilege, as well as to the ways in which girls can lose agency under the close watch of controlling father figures. And her movies sometimes follow their restless captives in some kind of search for escape into something that seems more authentic.

It’s surprising that she didn’t bring Princess Diana to the screen before Pablo Larrain made Spencer. It seemed a perfect biopic subject for her after Marie Antoinette — but would it have been too similar a project?

The same question aggravates me a bit as I reflect on Priscilla. It has a lot in common with Spencer, so much so that I wonder if a double feature of the films would make for a fascinating study or seem merely redundant. And it has such tremendous thematic and aesthetic overlap with all of Coppola’s previous work, that it’s beginning to feel like this auteur’s filmography has become something of a bubble in itself, one I’d like to see her break free from. (2020’s On the Rocks, with Bill Murray and Rashida Jones, was something of a departure in subject and style, but that film felt more like something she made casually, improvisationally, and for fun between more serious features.) Priscilla, like all of the young women who look so good in such dehumanizing contexts, enchants us through what critic Hannah Strong calls Coppola’s “hyper-feminine aesthetic,” a “surface appeal” that seduces even as we realize that it’s draped over “a desire for freedom at any cost.”

I’m beginning to sense some diminishing returns in this redundancy: One might be tempted to say that Coppola is so in love with the glory of these toxic fantasy lands that the greater effect of her work is to increase their gravitational pull rather than to instill in us a wisdom about the abuse that takes place there. In her New York Film Festival capsule review, Veronica Fitzpatrick notes that “Priscilla is best when it’s sensual, not didactic, but that doesn’t mean it doesn’t do both.” She’s right, and this may be most evident in a scene where Elvis condemns Priscilla's preferences in outfits, strictly instructing her to wear only certain things that match his preferences. Spaeny is dazzling in these costumes, and in this context. And I started having PTSD flashbacks to that nightmarish scene in Hitchcock’s Vertigo where Scotty forces Judy to wear certain things and do her hair a certain way, dismissing the dress she clearly prefers. But isn't the movie itself clearly taking most of its pleasure in, and investing most of its energy in, aestheticizing Priscilla as a '60s fashion icon? Hitchcock’s focus is on the psychosis at work in this dynamic. Coppola’s, someone might persuasively argue, is on the pleasure of deciding for ourselves which dress is most enchanting on Spaeny. Fitzpatrick herself also admits that the movie is “unable to help itself from doing what it wants to critique.” I’m not quite ready to defend the film against any concerns that, on the subject of the objectification of women, it might be doing more harm than good.

Still, artists are who they are — they come from somewhere, they know certain important things based on their experience, and, by virtue of the limits of those experiences, they don’t know other important things. We love to find those threads that connect individual entries in a visionary director’s portfolio, threads that give the body of work a recognizably human voice. It would be presumptuous to expect movies from Sofia Coppola that aren’t somehow rooted in her most fundamental sympathies. Isn’t that often the dichotomy of auteurism? We expect to see manic neuroses, narcissism, self-destructive amorality, and even pedophilia in Woody Allen movies, and I’ve given hoping to see some kind of breakthrough, any story about an awakening conscience from him. Nevertheless, I always hope to have a sense that an artist is growing — not only in their abilities but in their curiosities and wisdom. And I think Coppola has explored stories like this before in ways that have offered richer rewards.

What would interest me most is seeing what kind of story she might tell about the “After” of this movie’s “Before.” Unlike Coppola (apparently), I’m not as interested in Priscilla’s angst as I am by what she might become when those bending borders finally break under pressure. We are so well-versed, as moviegoers, in the plight of the princess trapped in a tower. And that brings a sense of frustrating stasis to the whole affair. While Spaeny, who I cannot help but see as a miniature Natalie Portman/Shailene Woodley hybrid, is an exquisite avatar — not only for Priscilla herself, but for any promising young woman seduced by a fantasy* — I cannot shake the sense that we’re not really getting a strong sense of her capacities as an actress, as Coppola keeps her bound up in iconographic poses.

I should pause here to acknowledge that one of the movie’s most surprising and unsettling effects is how it so quickly and so convincingly turned me against the very Elvis for whom I was feeling empathy and admiration just a few months ago watching Baz Luhrmann’s Elvis. Priscilla, more than any film I can remember seeing in recent years, has revealed to me how susceptible I am to a strong filmmaker’s rhetoric. What do I really make of Elvis Presley, perhaps the most definitive American icon? At this point, I don’t know. But insofar as Presley’s testimony via Coppola’s dramatization is credible, I have to revise my understanding of Elvis’s legacy going forward to reckon with these chapters, which expose an inexcusably predatory and exploitative aspect of his character.

Jacob Elordi’s performance as Elvis rarely adds up to more than a passable impression of the famously idiosyncratic star. The physical resemblance is not particularly convincing. (The astonishing performance by Austin Butler just last year is still so vivid in my memory that it’s hard not to be thinking of his superiority in every scene of this film.) Maybe if I’d seen Elordi’s work in Euphoria I might have a better sense of what drew Coppola to cast him. But in his cartoonishly lean and looming stature, he emphasizes just how dominant Elvis was in this relationship with a child; Coppola seems to know this and uses it to powerful effect. And for that, I am grateful. Moviegoers need balanced, nuanced studies of their cultural icons. Luhrmann’s Elvis had its virtues, but Coppola provides a much-needed counternarrative.

Much of the press around this film has focused on the fact that the Elvis estate refused to permit Coppola to use Elvis’s songs in her movie. But you know what? I’m glad. This movie gives the King just the right amount of attention, and we don’t need any reminders of his strengths here. Elvis has received more than his due when it comes to adoration and reward for his art. And this movie isn’t about him. Relying upon her familiar finesse with contemporary pop soundtracks, Coppola gives the film a perfectly gauzy, dreamy sound that enhances the melancholy of Priscilla’s state of suspension in superficiality.

In fact, it’s not imagery that I will remember about the film’s jarringly abrupt conclusion. It’s a song. Coppola’s talents as a playlist maker remains untouchable. In her deep-dive examination of the director’s musical journeys, Sydney Urbanek writes, “To think of Coppola’s early videos as a mere preamble to her features is to sidestep how she still cuts her action to accommodate the songs she loves rather than the other way around….” And Priscilla’s climactic needle drop is a knockout. Indeed, it’s the best thing about the finale. I’ll save the surprise for you to discover. Suffice it to say that I cheered when I realized what was playing, even though I wouldn’t learn until after the credits rolled that there are important historical motivations for applying that song to Priscilla’s prison break. (Look it up.) It's an inspired choice for an otherwise underwhelming conclusion.

Is the song supposed to spell out for us what Priscilla is thinking as she makes her famous exit from Graceland and takes her first step into freedom and autonomy? I don’t know. I’m not sure what to make of the ending, actually. I come away more disappointed than intrigued, as that moment gave me a fleeting surge of hope that the story was about to take us somewhere new, into a glimpse of the woman Priscilla would become. Maybe I was expecting too much. Maybe Coppola can’t quite imagine a character outside of a dehumanizing bubble.

Larrain’s Spencer concludes with the same startling abruptness, and yet that final moment felt just right. For all of the creative license Larrain took with Diana’s historical account, and for all of the presumption he brought to his depiction of that icon’s interior life, he created for us a three-dimensional human being. His Diana is possessed of a fierce intelligence beyond the hairdos and dresses. We get more than just glimpses of who she really is in her intimate conversations with her assistants, and in moments of joy and tenderness with her children. The last image of Spencer is more complicated and interesting — and thus more memorable — as well. The runaway princess seems to have landed on another, equally challenging planet.

It’s interesting to me that two more of the year’s biggest movies conclude with their leading ladies turning their backs on the men who adore them and walking off into a future alone. It happens in Martin Scorsese’s Killers of the Flower Moon. And it happens even more memorably in Greta Gerwig’s Barbie, which concludes with a celebratory flourish, as Barbie begins to define herself beyond the context of a toxic co-dependency. It leaves me wondering what a Sofia Coppola Barbie movie might have looked like. I suspect it would have been soft, quiet, lush, luxuriant, and aching with melancholy. It would have indulged with greater reverence in hair, makeup, and costumes. It would have, come to think of it, been a lot like Priscilla.

* I was tempted to write this reflection as a comparison of Priscilla and that old Jim Henson/George Lucas rock-star-chasing-an-underaged-muse fairy tale Labyrinth.

Misgivings about "a masterpiece": Killers of the Flower Moon

An early draft of this review was originally published on October 28, 2023,

at Give Me Some Light on Substack, months before it appeared here.

Subscribe, and you'll read many of these reviews while the films are still breaking news!

Ban this teaching, Ron DeSantis. I dare you.

(Apparently, Oklahoma is working on doing that very thing — erasing an essential truth from American history so that new generations live in ignorance. Oklahoma: Land of the Wisdom-Free, Home of the Less-than-Brave!)

Did you know that the peak of Google searching for “Mike Pence” happened when a fly landed on his head on national television? That fly may be the most famous of its kind since the fly who landed on Paul Freeman’s face and appeared to crawl into his mouth during a key scene in 1981’s Raiders of the Lost Ark.

I want to know how director Martin Scorsese managed to track down the Mike Pence Fly and then, in the production of Killers of the Flower Moon, direct it to land symbolically on the heads of characters whose hearts have gone dead. I need a journalist to ask the big questions! And let's get that bug a supporting actor nomination!

But seriously, I have trouble believing the appearance of a fly on the head of Sheriff William Hale — during a scene in which he is feigning concern for local Native Americans, and covering up his conspiratorially murderous endeavors against those same people — is just a coincidence. (No, that’s not a spoiler, unless you’re new to the idea that the First Peoples have been the targets of a genocidal strategies since so-called “American history” began.) There are other moments later in Killers of the Flower Moon when flies buzz about the heads of other criminal characters as if to draw attention to their cold, dead hearts, and their distinctly American malevolence.

Killers belongs in the genre we call “True Crime,” a longstanding tradition of American entertainment that the movie eventually acknowledges—and, before it’s over, explicitly dramatizes. The film, like the book by David Grann that inspired it, in an exposé revealing crimes against humanity that white supremacists and Christian nationalists would rather erase from school history classes—carefully documented conspiracies that have gone unpunished and that contradict the very principles that patriotic Americans have typically boasted about. It reveals that, for all of our self-congratulation over defeating the Nazis in World War II, we are equally capable of—and guilty of—race-based genocide.

And Scorsese isn’t just focused on what white settlers, with the cooperation of their “by the white people, for the white people” government, have done (and continue doing) to Native Americans. There’s a smart glance sideways, as this story’s violence unfolds, toward news footage of the Tulsa Race Massacre.

The movie is not subtle in suggesting that if we don’t ever—even now, in 2023—face fully our moral failings and complicity in this violence, if we can’t take action to make amends, we encourage the undeniable swelling of Nazism and other tumors of hatred and violence within the bodies of our own communities and cultures. So long as we support, enable, and make excuses for criminals in positions of power—as Pence did for Trump, and as our weak-willed protagonist does in this story—we are bound to increase a debt of depravity for which the bill will someday come due.

Killers of the Flower Moon has so much more to offer than an historical whodunnit.

Grann’s deeply troubling account is about a former Texas Ranger who joins the FBI in its early days and is sent to investigate relentless murders of the Osage people in Oklahoma. Scorsese’s movie, staying true to the historical details, reimagines the narrative, postponing any coverage of that investigation until after we’ve become invested in the community where the crimes are carried out.

We’re introduced instead to Ernest Berkhart (Leonardo DiCaprio), a slow-witted World War I war veteran who returns to his Oklahoma-based family in Osage territory to receive a hero’s welcome and find a new life working for his uncle, William “Bill” Hale (Robert De Niro), the local deputy sheriff. Ernest’s face isi almost always contorted in efforts to make sense of this society, his responsibilities, and his own conflicted conscience. He’s surprised by, confused by, and even a little aggravated by the fact that the Native Americans there are among the wealthiest Americans he has ever met, enjoying the rewards of having found oil on their land. Like the cab man famously played by De Niro himself almost a half-century ago in Scorsese’s early masterpiece Taxi Driver, Ernest is easily confused and deeply insecure. Like Henry Hill in Scorsese’s GoodFellas, he’s easily duped and manipulated into carrying out the dastardly deeds of a criminal mastermind. And like Kichijiro in Scorsese’s adaptation of Shasuko Endo’s Silence, Ernest is doomed to become a fear-driven fool, prone to betraying even those he loves the most when the devils who control him require it.

When Ernest falls for Molly (Lily Gladstone), a local Osage woman who matches the “body type” he describes to his uncle as his sexual preference, Hale seizes this opportunity to secure their marriage in a way that will also re-route fortunes from Molly’s family toward his own.

In the movie’s opening scenes, Hale instructs Ernest to “educate” himself on the Osage through a children’s book about their history. If you’ve seen the trailer for Killers of the Flower Moon, you’ve heard Ernest repeatedly sound out the words of a question: “Can you find the wolves in this picture?” And the implication is clear: In this film, some villains may be obvious. Others may lurk in the shadows, wearing the “sheep’s clothing” of civil servants, philanthropy, healing, and faith. As Ernest scowls at a picture-puzzle illustration in the book, he lacks the imagination and intellect to realize that his own kin are deliberately embedding and entangling themselves in Osage communities like predators stalking prey with intent to take their land, their oil, and their fortunes.

The most obvious of the villains is probably clear to us through casting alone: De Niro plays Sheriff Hale as a charismatic politician with all the right (and the “Right”) religious vocabulary, feigning Christian conviction while pulling strings to rob the Osage blind. And he’s good enough at this game that Osage elders honor him as a champion of their cause, even relying on his resources to seek out those responsible for the “epidemic” of murders in their community.

Like the proverbial frog in the pot of boiling water—or, in this case, boiling oil—Ernest is easily persuaded to embrace a contradiction that will break him apart from within: Even as he loves Molly and starts a family with her, he’s soon following his uncle’s orders for increasingly flagrant violence, an Oklahoman application of nationwide campaigns advancing a genocide of Native peoples. Even as Ernest struggles with the harrowing and debilitating intensity of Molly’s grief over mounting losses to her family, he goes on covering up his uncle’s sins, even negotiating terms with notorious hit men himself, unable to persuade himself that the man he’s been conditioned to adore could be such a serpent… such a wolf.

As many critics have observed already — I’m especially grateful for Alissa Wilkinson’s outstanding reflection at Vox.com — Killers of the Flower Moon continues a profound trend in Scorsese’s recent filmmaking. As in Silence and The Irishman, he is stripping away the glamour and glory that he afforded criminals in films from GoodFellas to The Wolf of Wall Street. While his movies have never condoned the evils of the gangsters that so fascinate him, they have always given more attention to the charismatic characters committing the crimes than to those who have suffered from the greed and the violence.

I hold that we need Taxi Driver, for all of its horrific bloodshed. We need stories that inspire our empathy for the poor, the social outcasts, the alienated young men who can easily, if they are denied care and guidance, and if they grow up in a context of toxic, gun-worshipping masculinity, become sociopathic killers.

What’s more, much to the chagrin of many of my Christian colleagues, I think we need The Wolf of Wall Street too. Its extremely R-rated portrayals of misogyny serve to deconstruct a corrupt cultural iconography. It peels away the flashy facades of those who live in wealth and privilege, showing us the cancers rotting the heart of the American experiment. (Even recently, Christian film critics were calling me out for approving of “pornography.” What Scorsese’s doing isn’t pornography. He’s placing images equivalent to those that seduce young men into dangerous criminal gangs right alongside images of the devastating consequences of such lifestyles. It’s an effective, if risky, bait-and-switch.) The Wolf of Wall Street has already served us as a prophetic vision of America’s past, present, and future: It showed us how a capitalist society, devoid of moral vision, enables and empowers compulsive liars. It all but predicted that we would soon promote a con artist like Jordan Belfort to the office of President. I think almost daily of the irony that most evangelicals who, making a fist of one hand and shaking it at me for praising The Wolf of Wall Street and its morally depraved antihero, will simultaneously, with their other hand, vote for politicians who behave just as malevolently as that antihero. They can’t stand the discomfort they feel when they see such behavior on the screen, even as they enable an Antichrist guilty of the same behavior to reach the White House, hoping he’ll deliver on his false promises to them.

Having said that, I am grateful to see Scorsese, in these later years of his career, expanding the frame of his vision. In Killers of the Flower Moon, he gives unprecedented attention to those who suffer from the crimes of the gangsters who so fascinate him. The compassion and lament woven into the fabric of this tapestry represent a deepening of conscience and wisdom. He is bearing witness to the deep hypocrisy of this so-called “Christian nation.” He is doing his best to educate us about our cultural sins and the moral responsibility we bear to make amends for them. In Killers of the Flower Moon, he does this in a way that admits his own complicity in a history of injustice. All of this seems like a progression from things he said to me when I interviewed him during the theatrical run of Silence. (You can read that conversation here.)

The fact that he’s working on yet another film about Jesus, at the suggestion of Pope Francis himself, fills me with anticipation and hope. I have great respect for his first film about Jesus, despite its weaknesses, and I hold in even higher esteem his reverent adaptation of Silence with its portrait of devout Christian missionaries discovering the consequences of presumptuous evangelism.

Nevertheless, I find that Killers of the Flower Moon leaves me with deeply conflicted thoughts and feelings.

As big-screen entertainment, it is impressively artful on almost every level of craft, from the performances (with one notable exception that I will critique momentarily), to the period recreation of 1920s, to the powerful scoring by Robbie Robertson. The 3-hours and 25-minutes fly by in what feels more like 120.

But while I commend Scorsese’s conscientious efforts to spotlight the sufferings of the Osage people, and to give Lily Gladstone’s Molly the most prominent role of any woman in any of his 20+ feature films, I feel that the great director’s preoccupation with “wolves” too often dominates this picture. For all of the energy he invests in honoring the First Peoples by revealing how they were deceived and slaughtered, his fascination with the depravity of powerful men still seems the subject he’s most excited about dramatizing.

And that makes Killers of the Flower Moon, in spite of its notable strengths, feel like a missed opportunity.

The movie is strongest when the camera is focused on actors playing the Osage community, particularly Lily Gladstone as Molly. Or, when it is focused on Robert De Niro, who is doing some of his best work here since Michael Mann’s Heat in 1995.

I'll probably be in the extreme minority on this point — but here we go: I find Leonardo DiCaprio's lead performance to be, for all of its Oscar-begging showiness, the film's weakest link. It’s not that his acting is poor, exactly; it’s that there’s just too much of it. He seems to be striving so hard for a Brando-level transformation here (are those cotton balls he's stuffed into his cheeks?), that he seems almost desperately needy for attention whenever he’s sharing a scene. This is a movie that needs generous performances.

During the first two hours, I was content to brush off DiCaprio’s familiar intensity, in part because it was refreshing to see him cast off any sex-symbol status and create such an absolutely wretched protagonist. Ernest is so dumb, so gullible, so pathetic; his conscience is just a feeble spark buried under a heap of ashes, one that we hope will suddenly flare into action. But in the third hour, DiCaprio's familiar capital “A” Acting — which always has a hint of desperation about it, as if he's trying to live up to “the promise” that critics hyped up during those impressive childhood performances — takes over. And he goes Full-Revenant, contorting his face in such paroxysms that he looks he's fighting a CGI bear to be animated in later. Unlike any other actor in the movie, DiCaprio seems to be running on a script designed to earn an Oscar nomination. It’s like there are tiny coaches running around inside his head shouting Act! Act! Act!

As a result, I have trouble believing that Molly, who seems so wise, so careful, so dignified, would fall so easily for this stammering dope. (That makes this the second American History Epic, after Gangs of New York, for which Scorsese has set DiCaprio as a romantic lead, and I end up constantly thinking about the actor's striving instead of believing the character he's playing.)

There's so much wonderfully nuanced acting going on all around DiCaprio that he almost seems nervous about it. By contrast, performances by De Niro and Gladstone and Plemons and — the most pleasant surprise here — Jason Isbell (!!) seem effortlessly convincing and magnetic.

By contrast, what a relief it is to see De Niro invested again, being his actual age instead of having to act against de-aging tricks like he did in The Irishman. As William Hale, De Niro makes this “Bill” every bit as malevolent as Daniel Day-Lewis’s “Bill the Butcher” in Gangs of New York. But unlike that hyperviolent monster, Hale never has to fire a bullet or throw a knife to become the film's fearsome anti-soul, a black hole of lies and schemes and greed. On a couple of occasions, De Niro jump-scares us with that old Max “Cape Fear” Cady smile, and I was just so glad to see that he's still capable of committing fully to a complicated role.

But then again, just as I have trouble believing in Molly’s love for Ernest, it wasn’t that long ago that I wouldn't have found the community’s trust in the obviously duplicitous Hale too implausible. The charade of civility and religiosity that Hale puts on to gain control over the community seems like a con to me from the start. But now I understand it — it’s not that Hale is fooling his fellow Americans. It’s that the white “Christian” community developing around him would rather turn a blind eye to his moral failings, and enable a monster of "their own kind," than have to share the world with cultures they see as inherently inferior. The Devil doesn’t need to don a disguise; he just needs to promise insecure “Christians” that he’ll give them cultural supremacy, and they will hand him a badge, a Senate seat — even the White House. All they ask is that he sweep aside the neighbors they see as "incompetent" and "savage."

This is happening right now, in real time, even this week, as a man who cloaks himself in the lies and distortions of Christian nationalism seizes the role of Speaker of the House. The tactics of the villains spotlighted here by Scorsese are being practiced in broad daylight by today's GOP. There's a direct line from Bill Hale to Jordan Belfort to "President" Trump. And Scorsese isn’t shy about highlighting that, giving Hale scenes in which he boasts about his “close friendships” with the very people he seeks to erase.

Given my experience with the evangelicals who condemn The Wolf of Wall Street but vote for DeSantis and Trump, I don't expect that Killers of the Flower Moon is going to do anything to awaken "Christian" America's collective conscience. They'll call the depiction of Hale an "attack" on Christianity, just as they said of Paul Dano's mad evangelist in There Will Be Blood (perhaps the big screen’s closest equivalent to a Flannery O’Connor monster that we’ve seen since John Huston’s Wise Blood). They’ll make a fuss about this in order to drown out the implication that their own churchgoing communities might be complicit in American genocide.

Meanwhile, Gladstone's Molly becomes the film's suffering Christ: at times a Mona Lisa, wisdom shining in a penetrating gaze and a tight-lipped silence, and at other times a Joan of Arc, slowly burning before our eyes at the stake of white supremacy and flagrant greed. (If it had been up to me, I’d have given Gladstone top billing. DiCaprio doesn’t need it. And it feels inappropriate to even suggest that heart of the movie beats for Ernest and not for Molly.)

The camera may be enamored of DiCaprio and De Niro, but the magnificent score by Robbie Robertson is a direct line to Molly’s heart, pulsing with sounds rooted in Native tradition. In this grand finale to a relationship that began with 1977’s The Last Waltz, Scorsese and Robertson give the film one of its most distinctive flourishes. And it serves as a profound conclusion to a series of Robbie Robertson records that have celebrated Native American traditions — most significantly 1994’s haunting Music for the Native Americans. He provides us with a voice for Molly’s lament in more than words can say.

In her, we glimpse a genuine faith. Scorsese goes so far as to show us avatars of the spirits she believes in, appearing not as delusions for a traumatized victim but as an elder steps into the afterlife. With this, Scorsese boldly affirms that Molly is more intimate with a Holy Spirit than of her “Christian” neighbors on the scene. And in the film’s closing shot, we get a sense that the spirits who anchor her, both within time and beyond it, represent a higher power that will bring about an inescapable reckoning for all of the sins so blasphemously committed under the banner of "Christian America."

A bittersweet conclusion and a nagging question

How do I express the second of my lingering frustrations with the film without ruining the surprises and challenges of the film’s final fifteen minutes?

I’ll do my best.

Suffice it to say that Scorsese, as “earnest” as he is here about exposing the truth about America’s genocidal crimes against the First Peoples, makes a sudden stylistic turn near the end that makes it almost inevitable that our post-movie conversations will be as much about him as they are about the sufferings of the Osage people or about the ways in which white Americans’ insidious and ongoing efforts to eliminate Others continue today. And that involves a fleeting cameo appearance.

I want to come away from Killers of the Flower Moon talking about and thinking about and grieving for the Osage and all of the other tribal peoples who were slaughtered by myriad strategies, all obscene, all satanic. And I do. But who did I spend the first hour after the movie thinking about and talking about? And who do I see professional film critics talking about most in their reviews? Scorsese.

In Alissa Wilkinson aforementioned piece at Vox.com, she highlights how this movie works continues a trend evident in Scorsese’s last few movies to reveal something about the filmmaker’s own soul-searching. Near the end of the piece, she writes,

Showing up at the end of Killers of the Flower Moon to specifically note how the story of the murders and of Mollie’s family was largely ignored is a tacit acknowledgment that [Scorsese] knows this isn’t a perfectly constructed story, either. Here he is, a man whose success comes at least in small part from proximity to the kind of men who murdered, asking for forbearance. For forgiveness, in a sense. An admission that these real events are not really fodder for an award-winning movie with a red-carpet Cannes premiere. None of it ever really has been.

She’s right, of course. (Wilkinson is one of the wisest writers in film criticism these days, and I’m so grateful that she’s publishing on such a prominent platform. I hope we get to see many more years of her work there.) What she’s highlighting needs our attention. Any close analysis of a work of art is bound to give some attention to what we know of the artist.

At the same time, it concerns me that so much of what I’m seeing and hearing in the wake of this movie’s arrival is preoccupied with talk about Scorsese himself.

The life within a work of art is so much greater than anything the artist might intend or even begin to understand. In every class I teach about creative writing and literary analysis, I fight a losing battle with students over the idea that the “real meanings” of any works of art are something the artists keep like secrets, and that they are the only ones who can truly answer our questions. It’s just not true. An artist might have all kinds of thoughts, intentions, and convictions that lead them to put marks on the page. But once the marks are there, the marks have lives of their own, bringing with them worlds of association and history that the artists weren’t thinking about. And when audiences examine those works, they bring their own ideas, fears, and questions to the encounters, which means they will see make new connections and see new possibilities. In my countless conversations with artists, I have come to love the frequent experience of seeing an artist discover that their art means something they’ve never thought about before.

Thus, while I’m interested in talking about a film’s director in the broader conversation about the film, it’s the art itself and the work’s energy matter to me so much more than the artist. As Annie Dillard writes in Holy the Firm,

There is no such thing as an artist: there is only the world, lit or unlit as the light allows. When the candle is burning, who looks at the wick? When the candle is out, who needs it? But the world without light is wasteland and chaos, and a life without sacrifice is abomination.

Yes, Scorsese is making sacrifices here at the end of his career — sacrifices that may be a form of atonement for earlier works that devoted more awestruck attention to swaggering crooks than to those who have suffered for their crimes. But how much energy shall we expend on admiring his act of conscience when we might instead devote meaningful time and effort in the greater matter at hand: the neglect of those who have suffered immeasurable loss in the violence enabled and even enacted by Americans?

Most of the post-movie conversations I’ve experienced about Killers of the Flower Moon have been about Scorsese, his bravery, his character, his bold choices in the final minutes. Very little of the discussion has focused on the sufferings of First Peoples—which I want to believe is the true focus of the film—or on the ways in which Sheriff Bill Hale, his greed, and his violence against brown- and black-skinned Americans is perpetuated today by Christian nationalists and by Republicans who are seeking to censor true chapters of American history like these.

Sure, when it comes to what we talk about when we talk about Killers of the Flower Moon, much of the responsibility lies with the audience. Maybe it’s just easier to talk about the celebrities than it is to talk about the depth of our complicity in crimes against humanity. But the fact remains that my attention—and I suspect the attention of the audience—suddenly shifts during those final minutes in a way that turns our attention to Scorsese’s conscience rather than the dead for whom we’re (hopefully) grieving. It’s a conundrum I’m struggling with. If I write a novel, I don’t want do anything in the storytelling that will make articles published about the book focus on me, my personal history, or the health of my conscience. I want people to be shaken by the questions and characters that shook me as I wrote the story.

Don’t get me wrong: This isn’t a last-minute dismissal of Killers of the Flower Moon. It’s a great film, and one of the most important events this year in American pop culture. I’m just saying that I wish I had been able to remain enchanted by Scorsese’s magnificent storytelling, and moved by Gladstone and the rest of the cast who were so generous in their ensemble performances. I wish I had been less distracted by the itchy feeling that, as the credits finished rolling, Scorsese might have, even with the best of intentions, ended up making things too much about himself.

Regardless of my aggravations, which I express here in the hopes that they might at least season the larger cultural conversation we’re having about the film, I believe that this movie’s strengths—its urgent and excruciating truth-telling, its often extraordinary artistry, its profoundly affecting score, and the burden of responsibility it reveals to us in our suspension of disbelief—are what matters most. These are the reasons I am so grateful that the movie exists. If we do not join Scorsese in this public acknowledgement of these crimes, taking responsibility for our complicity, and engaging in meaningful and substantial repentance, we're bound to see history repeat itself. Or worse.

And I don’t want those flies settling on my head.

Three Colors: Blue at 30

An early draft of this review was originally published on September 14, 2023,

at Give Me Some Light on Substack, months before it appeared here.

Subscribe, and you'll read many of these reviews while the films are still breaking news!

I first saw Three Colors: Blue in its original theatrical release way back in 1993.

I was impressed by Krzysztof Kieślowski’s follow-up to the magnificent The Double Life of Veronique. In fact, I was moved.

I had no idea that, thirty years later, it would be one of two films that I would name when asked “What’s your favorite film of all time?”

Art takes time. Our relationships with works of art grows and changes over time. And Three Colors: Blue engages questions about art, faith, love, and the meaning of life in ways that no other film I’ve ever seen does.

I’ve talked about my love for this film for years, and written about it on numerous occasions — for my own website (LookingCloser.org), for Image, and elsewhere.

And yet, when I was invited to write a substantial study of a film that has demonstrated great “spiritual significance,” I jumped at the chance to write about Blue again. This time, I couldn’t stop writing. I ended up with an essay one adjective shy of 10,000 words.

It’s called “To Love and Be Loved in Return: 30 Years of Discovering Kieślowski’s Blue.”

It is now published in a volume that includes work by some of my favorite writers on the intersection of faith and film — including Steven D. Greydanus and Evan Cogswell, to name only two. And the book was edited by Kenneth Morefield. These three and other contributors to the book have long been a part of an online community of cinephiles who are also people of faith. The discussion board ArtsandFaith.com eventually developed 20 years of archived conversations, open to the public, focused on countless films, albums, books, and other varieties of art. Alas, that extraordinary body of work, which had been hosted by the literary arts journal Image, was closed down and erased a few years ago. We lost a documented history of how the dialogue on faith and art had grown and changed over decades.

But this book represents an important historical artifact. The Arts & Faith Top 100 was a list of “the most spiritually significant films” ever made, and it was voted on and re-voted on, revised every few years, so that we had a variety of published lists. We also voted on and published variations on the list, such as “The Top 25 Divine Comedies” and “The Top 25 Films on Mercy” — comedies that directly address spiritual questions and concepts.

Now, Cambridge Scholars Publishing has published Film as an Expression of Spirituality: The Arts and Faith Top 100 Films.

It’s a book that includes a variety of essays on some of the films included in that list. (The working title of the project was The Soul of Cinema: The Arts and Faith Top 100 Films, but the publisher scratched that title and came up with the final version. I actually prefer the original title.)

Many thanks to editor Kenneth R. Morefield for his long-suffering dedication to the project.

The book includes close examinations of so many profoundly inspiring films, including Dreyer’s Ordet, Scorsese’s Silence, Bergman’s The Seventh Seal, Antonioni’s L’Avventura, Pasolini’s The Gospel According to St. Matthew, Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, Joffé’s The Mission, Weir’s Witness, Axel’s Babette’s Feast, Miyazaki’s Spirited Away, Lee’s Do the Right Thing, Burnett’s To Sleep With Anger, Hausner’s Lourde, Schrader’s First Reformed, and more.

The Eight Mountains (2023)

An early draft of this review was originally published on September 14, 2023,

at Give Me Some Light on Substack, months before it appeared here.

Subscribe, and you'll read many of these reviews while the films are still breaking news!

I continue to believe that much of Peter Jackson’s success with his film adaptation of The Lord of the Rings had to do with how enthralled audiences were with seeing the glory of New Zealand — those mountains, those panoramic wildernesses — projected on such a grand canvas. The more our attention is absorbed by screens, the more we tend to be creatures of indoor-habit, and the more we long for what we’re missing: the created world in its sensual, ancient, awe-inspiring glory.

That is, no doubt, why I added The Eight Mountains to my must-see list the first time I saw the trailer. And that will remain, most likely, the thing I cherish most about the experience.

Somehow I’ve missed both of the previous films by director Felix van Groeningen — Beautiful Boy, a reportedly harrowing drug-addiction drama about a father (Steve Carrell) and son (Timothée Chalamet), and The Broken Circle Breakdown, the story of a rocky romance between Belgian bluegrass musicians. The latter was co-directed by Charlotte Vandermeersch, and the two have collaborated again here on this adaptation of a novel by Paolo Cognetti: an epic story of a friendship that began in childhood and remains strained but strangely unbreakable over their courses of their troubled lives.

The Eight Mountains is several things at once:

- a celebration of the Italian Alps, ruggedly glorious landscapes that deserve long, slow, panoramic attention;

- a study of how men tend to live lives either inspired by their fathers, wounded by their fathers, intimidated by them, or longing to fill the voids that they left; and

- a philosophical meditation on two ways to live life—by devoting oneself to a singular place and passion, or by following questions far and wide.

As it begins, eleven-year-old Pietro, the son of a Turin-based engineer, spends a summer with his mother in a rental in Grana in the Italian Alps, and there he meets Bruno, the one remaining child in a slowly disappearing mountain village. While the city boy is enchanted by the village boy’s raw, rough, aggressive demeanor, and while he delights in how happy this lonely stranger seems to be to have a friend, their relationship is quickly complicated: Pietro’s mother wants to help the boy socialize and find opportunities away from his grim situation at home. And Pietro’s distant, difficult, hyper-masculine father embraces Bruno as the kind of son that he wishes Pietro would be.

How can Pietro find peace as Bruno’s soul mate if his friend only worsens his sense of insecurity and insufficiency around his own father?

One of the film’s strengths is how convincingly it tracks both Pietro and Bruno over many years. They are played in childhood, late teens, and then adulthood by three sets of actors — child-actors Lupo Barbiero and Cristiano Sassella, then Andrea Palma and Francesco Palombelli, and finally Luca Marinelli and Alessandro Borghi. And all of these actors are excellent choices. We believe the time-shifts without trouble, a feat rarely achieved in films that cover such large spans of time. (I still feel like I’m shut of out of the near-universal enthusiasm for the Oscar-winning Moonlight because the differences between the actors playing the central character were so jarringly distracting.)

I was drawn in to The Eight Mountains early, just as I was with a thematically similar Belgian feature — Lukas Dhont’s Close — at the beginning of this year. Cinema is a world in which artists and audiences alike seem perpetually uncomfortable with the subject of male friendship. Don’t get me wrong: We need movies like Brokeback Mountain. But it’s as though the medium has become so hyper-sexualized that we don’t know how to focus on anything but eroticism when two bodies share screen space together for a prolonged period. I still get headaches recalling how so many moviegoer conversations about The Lord of the Rings devolved into arguments about whether Frodo and Sam were gay, or whether it wouldn’t have been better to re-imagine Samwise as female so we could scratch our insatiable itch for romantic subplots.

In her review, New York Times film critic Manohla Dargis notes, “The spiritual dimension of Pietro and Bruno’s bond has its appeal, and one of the movie’s pleasures is that it takes male friendship seriously.” But she cannot help but give the next several lines to wondering about the “expressly erotic dimension [of] the men’s love for each other,” and explicitly speculating, “Perhaps, during one of the long summer evenings they spend together after Pietro returns to the area, one quietly reaches for the other under the cover of night.” Is this tangent really necessary? Did I miss something — or is there no suggestion whatsoever, however subtle, that their friendship takes such a turn?

At the mid-century mark, I can look back at dozens of substantial friendships that have lasted decades with men and women alike — and these stories include all kinds of outdoor adventures and camping trips — that have been healthy and meaningful while remaining responsibly and effortlessly platonic. Storytellers, particularly in television and movies, seem to lack imagination, discipline, and curiosity on this subject, and I’m sure that has a significant ripple effect on real-world behaviors. Maybe sexual harassment and assault would be rarer if we grew up attending to stories about the possibility of, and the rich rewards of, intimate and yet platonic friendships… I don’t know. Is my experience so rare? What a miserable life it must be for people who cannot enjoy friendships without being tormented by the question of “Will we or won’t we?”

Anyway, I would have been disappointed if van Groeningen and Vandermeersch had given in to such a familiar and predictable storyline and lost the film’s distinctive focus on the ways in which fathers — either present or absent, loving or difficult — shape their sons and influence how those boys will relate to other boys. That is, for me, the most interesting thread of the film, so much so that I sometimes struggled to stick with the movie as the fathers faded into the spectacular backgrounds.