Radio (2003)

An earlier version of this review was originally published in a Film Forum column at Christianity Today.

•

Radio is another sport-oriented true-life drama from writer Mike Rich, who wrote The Rookie. Like that film, which was one of 2002's most rewarding and surprising releases, Radio focuses on the way a community comes together to lift up one individual and help him surmount difficult obstacles.

In Radio, the spotlight falls on a South Carolina high school football coach named Harold Jones (Ed Harris). Jones's wife, his daughter, his team, and a whole community (minus one wicked banker) assist him in his efforts to help a lonely, misunderstood, mentally disabled person — James Robert "Radio" Kennedy (Cuba Gooding, Jr.) — find friendship and purpose.

The film is significant in that it breaks Cuba Gooding, Jr.'s streak of lamentably bad roles and forgettable performances. Since he won his Oscar for Jerry Maguire, Gooding has signed up for a bunch of awful lowbrow comedies (Rat Race, Snow Dogs, Boat Trip.) Here, however, in a role that could easily have been overplayed, the actor shows remarkable restraint, and makes us care about a young man who needs love. What is more, he becomes an example of unconditional love by the way he responds without selfishness or grudge to those around him who have in the past mistreated him.

But the most striking thing about Radio, at least for this reviewer, is its unconventionally intense concentration on one neighborhood's charitable endeavors. Most sports movies culminate with "the big game" and a cliffhanger tie-breaker. Here, although there is a montage about the local team's wins and losses that is framed in the same way as the one in The Rookie, there is very little emphasis on competition. Sports are merely a backdrop, not the main event. Director Michael Tollin — whose last film was Summer Catch with Freddie Prinze Jr. — has his priorities are in the right place as he makes the human drama the center of our attention.

In fact, the lack of any suspense becomes a problem for the movie. Radio oversimplifies its central dilemma — and its characters — so much that there is nothing much to consider or concern ourselves with. We sit secure in the obvious rights and wrongs of the situation, cheer for the nice guys and boo the cookie cutter villain who is uncomfortable with Radio's acceptance. (Why he is bothered by Radio is not much explored.) And if any uncertainty arises regarding where a scene is going, the music declares for us what our emotional response should be. Despite the fine efforts of Harris and Gooding, Jr., Radio nearly drowns in James Horner's overbearingly sentimental music.

The Rookie had complex, realistic, believable characters. Radio may be based on a true story, but the supporting players that populate this film seem flat and one-dimensional. Despite its honorable intentions, it practically pounds us on the head with simple moral lessons, and there is an unfortunate lack of things to think about afterward. We've had our most basic convictions affirmed, our emotions have been pushed around, and we walk away knowing very little about Radio, his condition, his background, his way of thinking, and the ethical questions regarding how to care for someone like him.

Making Songs Out of Stories: Over the Rhine's Linford Detweiler on 10 Years of Songwriting

[This interview was originally published at the website for a non-profit arts organization called Promontory Artists Association in February 2000.]

•

Linford Detweiler has learned to take it easy.

It’s a Saturday afternoon in Seattle, unusually sunny for late February, and he joins my wife Anne and me for coffee and cranberry juice at the University Plaza Hotel, his home for the weekend, far from his Cincinnati headquarters. Linford, his wife singer/songwriter Karin Bergquist, and their band––Over the Rhine––are in town for two special shows, a momentary tangent from their larger purpose…touring with the Cowboy Junkies.

This tour has brought new opportunity and energy to Over the Rhine, not to mention exposure to a larger audience. Appearances on The Late Show with David Letterman and Sessions at West 54th have placed them on well-watched platforms. This publicity is an unexpected highlight after a period in which their previous record label, I.R.S., folded, and their future seemed uncertain. It's been a decade-long rollercoaster ride from varying levels of obscurity to varying levels of fame.

Now, a new record contract with Virgin/Backporch may be the greatest opportunity they’ve yet had. While Over the Rhine have never been in the Top 40 or on the cover of Rolling Stone, word-of-mouth is having a cumulative effect. Current celebrities Sixpence None the Richer even thank Linford and Karin for their influence. The new deal has brought most of their recordings back into print; their latest independent work, the critically acclaimed Good Dog Bad Dog, is available in a new package with the addition of a new song.

An adventure like this might make some performers a bit shaken, anxious, exhilarated. But Linford seems content to take it in stride. Our conversation does not dwell on their imminent celebrity status, politics, other musicians, or scandals, but rather on books, songwriting, and the personal experiences that enrich his writing.

•

What are you reading these days?

A book that I just started is called Bird by Bird by Anne Lamott. I kept hearing her name, and my sister Grace lent me a few excerpts from it last time I was up visiting her. And Karin picked up a copy of Traveling Mercies. So Lamott is the current writer in our lives. We’re going to be performing at the writer’s conference at Calvin College. It’s a pretty amazing little gathering up there. Anne Lamott’s one of the main speakers, and Maya Angelou, one Karin’s favorites is speaking as well. And Chaim Potok.

I tend to come across a writer and try to read a good handful of what they wrote before I move on. My sister Grace and I both quit reading when we got to high school. We both went to boarding school in Western Canada, and we'd been avid readers. I didn’t start reading again until I was a junior in college. In school, we read what was assigned to us; we didn’t read for pleasure. The author that got me reading again was C.S. Lewis. Then I went through a big Dylan Thomas phase. I read a lot of what he wrote. Then I discovered Southern American writers like Flannery O’Connor and read everything she wrote, and then Annie Dillard. I’ve been reading a lot of Frederick Buechner’s stuff.

How did you get started writing songs and starting a band?

I wish I could say that my starting a band was shrouded in mystery, that it was some sort of profound artistic part of the project. But I was just naïve. I loved music. We said to ourselves, let’s start a band, get our songs on the radio, make a lot of money, live in England, buy a farm…. And while we didn’t achieve a level of success that we’d hoped for right away, we have in one sense or another accomplished most of these things. Just not all at once. It’s been life changing in ways I couldn’t have imagined. I learned fairly early that being famous was not what I really cared about. What I do love and care about is the words.

What do you find is the best kind of support and encouragement you receive from your friends and your fellow songwriters?

Michael Wilson has been a great inspiration. He was the first real "artist" that showed me what art could be about. He has this ability to pick out the unremarkable details of our lives and hand them back in a way that makes us see them for the first time. He’s shown me how we can learn to keep our eyes open to what’s behind the fabric of the ordinary. His work has been hugely influential. He’s also a very deep listener. He introduced me to a lot of good things. For example, he was the first person to play Tom Waits for me. Now that’s a perspective-altering experience!

And there’s another individual… I suppose technically he’s my pastor…. Dave Nixon. He’s a gifted writer, he has his doctorate in classical languages. He married Karin and I. He’s in the process of working through reinventing what church might look like.

It’s an extra challenge to work together with Karin as a creative couple, isn’t it? How do you two manage to work together as a team? Do you do most of your work together, or separately?

Karin and I… we’re together probably more than any other couple I’ve ever met. We do try to give each other some degree of solitude, to give each other that gift of time. We’ll work separately and then bring our work and sit down together. She’ll play me a song, and often I’ll say, "Don’t change a thing." Other times, she will have worked out the melody and I’ll supply the words. Often I’ll have a whole song worked out ahead of time. I see my job as being to write songs that allow her voice to bloom.

Many of our readers tell me about struggling with their work, about lack of success, doubts about their calling to be an artist. A lot of your work seems to deal with periods of doubt, struggle, darkness, even depression. Tell me about how you’ve dealt with the hard times as an artist, how you’ve worked through them.

There have definitely been difficult times. At the beginning sometimes things wouldn’t go the way we wanted them to, and I’d think "I’m not cut out to do this." Some of the most difficult relationships of my life so far have occurred with somebody that I was working with in the band. And that has been an exhilarating and sometimes devastating exercise in being a human being.

I go to this Trappist monastery called Gethsemane in Kentucky, just two hours from Cincinnati where I live. They have about a thousand-acres there where I can walk and think. I found out about it reading Thomas Merton. It’s a chance to be quiet. When I’m there I realize that the world really is a noisy place.

I went down to the monastery in 1995 and said "I think I’m going to let it go" and I made peace with that. Because of these stories we grow up with in the church, I had the image of Abraham’s son on the altar. And I basically said, "That’s it. I put it down. I’m free. I’m still young, and I’m going to go rethink my life." But when I got home, the first message on my machine said, "Hey, Linford… every spring Miles Copeland has this retreat with writers at his castle in Southern France and we’d like you to come over and hang out with songwriters and be a part of this. We’ll pay your way. All you have to do is show up." And then the next message was something else. Everywhere I turned it was clear, "Don’t quit music. You’ve started a story that’s not yet completed." So I ended up staying in it. And I feel really excited about that part of it now.

The mystery at the heart of so many creative people is that we’re trying to make sense of the story that we’ve been handed and the story that we’re helping to write with our lives. We write to try to figure out what we believe is true, and to try to make sense of what’s happened. On the one hand we bemoan difficult childhoods… or whatever it is…but on the other hand those difficult things make us who we are. It wasn’t Karin’s first choice for her dad to leave and never come back when she was three years old, for her to be the odd girl growing up in a small town in Ohio, the only one without a father…. Whatever pain was part of Karin’s journey has made Karin who she is. And she wouldn’t sing what she does if she had no abandonment. You listen to a song like "Poughkeepsie", and you know she’s definitely wrestled with depression at times.

You’re reminding me of watching Roberto Begnini win his Oscar in 1998. He ran to the microphone and thanked his parents for the greatest gift they could ever have given him… poverty.

Yes! Karin taped that, and we re-played that so often. I think that’s why I desire to write more and more. To try to make sense of the story of my past. And what went down in my family…oh, if you only knew. There’s a lot there, and I feel like I’m ready to start opening it up and looking at it. I think that’s where it starts. It starts with what we experience, and if it ends up being a fictitious character or a memoir or whatever, it doesn’t really matter.

•

So I go up Poughkeepsie,

look out o'er the Hudson

and I cast my worries to the sky.

Now I still know sorrow,

but I can fly like the sparrow

'cause I ride on the backs of the angels tonight.

-from "Poughkeepsie"

•

Do you write for an audience or for yourself? You make it sound like songwriting is a very personal private thing you do for yourself.

What goes along with writing for yourself is accepting the fact that your audience may be non-existent. It’s not really fair to write to please yourself and then bemoan the fact that you’re not hugely popular.

I’ve learned this from other artists that I respect. If you can’t say to others "To hell with what you think" to some degree, you’ll second guess yourself, and you’ll never create anything. A fair amount of what I do, I do based on a set of instincts that I’ve developed, by paying attention to what I love or what moves me, and hanging around with people that inspire me. I’ve never done anything that I really care about while trying to second-guess what somebody’s going to like. The healthy position for me is what I called in a song 'healthy apathy'.

I’m not really big on seeing a newspaper clipping and thinking, "Oh, I’ve got to write a song about that." I’m not one of those writers like Bruce Cockburn who tries to get a point across; it’s more of an intuitive thing. I’m trying to tell something that feels taut from beginning to end. I learn about what I’ve written along with everybody else.

C.S Lewis talked about wanting to "delight" and "instruct" in his writing. Sometimes the wanting-to-instruct was a bit too much for me. But he certainly did delight as well.

You certainly don't preach at us, like the Christian music you hear on religious radio. But the language of faith is woven throughout your work. It seems that right now there are lot of artists blurring the lines between other genres and Christian music, revealing more of what is possible for a musician of faith.

What has been your relationship and experience with the church and church communities in view of your music?

I’ve made it a point not to engage with the reactionaries. I try not to go into a place where the people expect us to be something that we’re not. When we started Over the Rhine part of my naïve self, having grown up in the church, hoped that Over the Rhine would be somehow a damaging blow to "Christian Music" in that it would be something that would blur the lines and draw people away from that mentality. And to some extent I think we’ve succeeded in shaking that up a bit.

I can remember people looking at us eight or nine years ago and thinking we were something alien in that we would play 150 club shows a year and then play the Cornerstone and Greenbelt festivals. People that were exposed to us at Cornerstone thought that we were a little bit odd. But now it’s a "no-brainer" for some band that came out of somebody’s youth group to go play in a club. Everybody does it now.

We did stop once at the Creation festival, right before we signed with I.R.S. Records. We were out on tour, we were going to play Cornerstone the next week. We thought "Why don’t we just stop by and put our records out." We could set up a little booth and find a few allies. And we were almost run out of there! It was one of those classic things where mothers gather together to protect their children from all of this "New Age" imagery. Karin and I were hanging out there biding our time and people would approach us in groups, a spokesperson with other people looking over their shoulder. We tried to engage them. One of the directors of the festival stopped by because well-meaning sixteen year-olds were coming back with their youth pastors’ arms on their shoulders saying, "I want to give this tape back. You never mentioned Jesus anywhere." Whatever. It was a bad experiment. Since then, we’ve been really good about realizing that certain people have an agenda for what they want to do, and if we don’t fit in, we’re not going to force it.

There has been definite progress. Sixpence None the Richer have started in a much different place. Theirs has been much more a youth-group audience. And now, with their self-titled album, it’s great to see them setting an example that you can move on to more ambitious songwriting, like yours, without sacrificing faith, without throwing the baby out with the bathwater.

(laughing) If that’s what they’re going to do, then they’ve got their work cut out for them. That was a very special record.

Do you envy the sudden phenomenal success Sixpence have experienced, or do you say to yourself, "There but for the grace of God go I?"

I was basically tickled pink for them. That’s everybody’s dream, especially at their age, to get that kind of attention placed on a song. It opens a door to a whole new level of a career. I don’t particularly envy them the process it took for them to get there…it was grueling. And I don’t envy them the fact that in a lot of ways their life now is not their own, and every nuance of their career will be scrutinized now. I can look back at certain points of my career and if that would have happened then, I would have taken the money and skipped town or self-destructed in various ways. I wouldn’t have had the resources to handle that.

If you could go back and talk to your younger self, back in 1989, and give yourself any messages or any warnings about the road that lay ahead of you, what would you say to yourself? And would your younger self go on ahead anyway?

I don’t think that I could do it again, but I would certainly encourage myself to do it again.

If you really want to do it, you embrace the chaos and don’t look back. When we first started to get [Over the Rhine] off the ground, to the point where we could actually make a living doing it, I said, "Every resource that I can possibly muster, every ounce of personal energy, I want to put in this. If we fail, I want to be destitute, and out on the street with nothing. I don’t want to have a little nest egg set aside that is my safety net for not making it." It’s been a labor of love, and we’ve never really cashed in, but we’ve had some nice surprises along the way. The madness of four people in a car traveling across the country staying in one hotel room is something I don’t think I could psyche myself up to going back to.

You've been touring and singing with the Cowboy Junkies. Has that affected the direction of Over the Rhine's music?

The Junkies get a lot of flak because they do this dreamy, "torchy", smoky music. Some people think it’s boring and sleepy, and to others its phenomenally unique and amazing. I see them constantly trying to rock their own boat, trying different things. Some things we're recording with them for their new record is in almost a Radiohead vein. I want Over the Rhine to do what we do best. Reckless curiosity is important, but it’s more important at the beginning of a journey, and then you want to rein it in and focus it.

Tell me about some of the more recent songs. There's a lot of sadness in these songs, as you said earlier, and the first song, "Latter Days," is a heartbreaker.

•

There is a me you would not recognize, dear

Call it the shadow of myself

And if the music starts before I get there

Dance without me

You dance so gracefully

I really think I'll be okay...

- excerpt from "Latter Days"

•

Where did this song come from?

It’s become an important song for me. It was written in my bedroom, I was just scratching some things down. When it's happening, you never know at the time that something is going to be that essential to your work. It’s just very informal. And that’s just one of the purest things I’ve ever written.

I was questioning another one of those periods where I felt like I was done with music, that I didn’t have what it took. So the whole bit about "dancing without me" is to other musicians… "You go on ahead and do it. I’ll get there eventually and I’ll be okay." The lines about, "I just don’t have much left to say"… that's very literal. "I’m supposed to be writing these songs, but I’ve been dashed on the rocks and I’ve got nothing left."

It wasn’t too long after Karin’s dad died that I wrote the song. He was really quite known for being a good dancer… he was a Presence. Those two images planted the seeds.

To me, there’s something about that sadness that is ultimately joyful. Some people wouldn’t see it that way. In one of the new songs that I want to record, the first line is "The saddest lines are the happiest, the hardest truths are the easiest." Karen Peris of The Innocence Mission has this sweet sadness that she carries. Other people have remarked on it. She carried this intense sadness that was so beautiful, and yet when she expresses that and you hear it coming out, it causes me so much joy even though it’s so sad. I guess that mystery, that sweet sadness, is something that fires my imagination.

You try to tell a story on a record. "Latter Days" is the first song on "Good Dog Bad Dog", but by the second song ["All I Need is Everything"] this person is already starting to realize that this place of brokenness is one of immense strength and renewal. Now that I realize that I’m completely shattered, I’m at a place where good things can happen.

Tell me about the new song "Moth", from "Amateur Shortwave Radio".

•

There's no savior hanging on this cross

It isn't suffering we fear but loss

When there's no one else around to blame

You're a burning moth without a flame

If you were to take my place tonight

See yourself in a different light

If you were to take my face tonight

Wouldn't Jesus be surprised?

- excerpt from "Moth"

•

Karin wrote the chorus and I wrote the lyric. She came up with "There’s no savior hanging on this cross, it isn’t suffering we fear but loss."

It really could be a song about an abusive relationship. People are willing to suffer for years in a situation that they know is ultimately destructive because the greater fear is losing it, making a fresh break. But you come to a place where the only redemptive option is to walk away. There’s no savior that can bail you out at this point. "When there’s no one else around to blame…"

In a sense it was a song about the original lineup of the band. We took it as far as we knew how, and in order for any good to come out of the future we need to move on to another situation.

"Faithfully Dangerous" is another intriguing lyric.

•

Your paint dries, the canvas smiles,

with two eyes you lift yourself up.

Stroke your skin, there are teeth marks to be sure.

Maybe we're best close to the ground.

Maybe angels drag us down.

I wonder which part of this will leave the scar.

- excerpt from "Faithfully Dangerous"

•

I must have written "Faithfully Dangerous" while I was reading The Writing Life by Annie Dillard. She talks about leaving "toothmarks" in manuscripts, and that’s a song to me that’s about creativity. If you do something creative, it’s going to be a wild ride, but make your peace with it. You’ll probably get dragged through the dirt, but maybe that’s good for you.

For me to talk about specific songs is fairly rare. I usually can’t do that too much. Putting the website together [www.overtherhine.com], looking back at our story, at where we’ve come from and where we want to go, I can see where songs fit into the story, but at the time it’s very intuitive.

What do you do to recharge, or when you can’t write?

Reading, maybe just doing nothing for a while. I’ve learned to make peace with that. It’s probably just exhaustion… (laughs) or lack of talent. The ground is just lying fallow.

Your bulletins to fans and the liner notes in your albums demonstrate a love of writing and of poetry. Sometimes I wonder if we’re going to see a book of poetry or memoirs with your name on it.

I've been thinking about it, actually. Perhaps when we get to a place where I have some time to focus on something like that...I would very much like to try.

Monster's Ball (2001)

[This review was first published on the original Looking Closer website on May 12, 2002.]

-

In Monster’s Ball, Billy Bob Thornton plays Hank, a corrections officer carrying intense racial prejudice in one hand and a sidearm in the other. Hank’s aging father Buck (Peter Doyle) constantly reinforces the family’s race-hate, calling Sonny, Hank’s son, "weak" because he befriends their black neighbors.

Halle Berry plays Leticia, the wife of a convicted killer, a mother trying to raise her son right and survive as a black single mother in the middle of the South’s racial tensions. After the criminal is executed, Hank’s dispute with his son (Heath Ledger) intensifies. But as he watches Leticia grieve while she works at his favorite late-night diner, he comes to care for her, and love begins breaking apart his prejudice.

Make no mistake: This is a story about people who are severely damaged and lost, behaving in reckless, dangerous ways as they nurse their particular needs for love, understanding, and intimacy. People are killed. Men lash out in racist hate. Father and sons call on and use prostitutes to find fleeting satisfaction. A mother beats her son. Lovers fall into hasty sex while under the influence of alcohol. It is not a pretty picture, and definitely not a film for younger viewers, or for the squeamish.

But the central theme of the story is this — hate, even hardened racism, can be overcome by love and compassion. Hank and Leticia are moving towards a mature relationship the way toddlers learn to walk — they’re making every variety of mistake, fumbling their way towards the basic lessons of love, gaining wisdom inch by inch. Their missteps are clearly portrayed as missteps. (Hank’s interaction with a prostitute is not glamorized, but shown as the joyless, empty, and contemptible exchange that it is. Thus, when he finds true love, the revelation is all the more meaningful.) Each mistake Hank makes teaches him something.

The performances of Billy Bob Thornton and Halle Berry are excellent. Billy Bob Thornton again shows he can make a bad script seem good. Halle Berry pours herself, heart and soul, into the character, making this her most impressive performance yet.

But director Marc Forster makes us too intimate with these characters. When two of them get drunk after a devastating day, they tumble into sad and desperate sex that is so explicit it will destroy viewers' suspension of disbelief and set them to thinking about the actors themselves. Sex scenes may have been necessary to illustrate the incremental, intimate relationship that develops, but the way Forster has filmed them makes them disruptive. It’s a primary rule of art, Mr. Director — less is more.

I also think Forster portrays Southern prejudice a bit too intensely. Sure, prejudice is still easy to find in certain areas of the U.S., but the movie doesn't explore the issue very thoughtfully. It's just loud, offensive, and in-your-face — a bunch of brutal clichés played for shock value, to make contemporary audiences gasp and end up hating the bad guys. If I lived in the South, I’d find the relentlessness of these portrayals to exhibit a prejudice of their own.

The films seem more evident upon reflection, after its powerfully meditative mood music and leisurely camerawork are finished. Forster is a little to excited about his film’s symbolism, and he uses it heavy-handedly. During one scene we see jarringly incongruous pictures of someone trying to free a bird from a cage. Yeah yeah, we get the point: Leticia’s caged heart is being set free. Not only is that a cliché, but there is no bird or birdcage in the story, unless I missed something; thus the audience is left trying to figure out "Whose bird is that?" If Leticia had kept a bird, that would have been just enough of suggested metaphor. As it is, it is nothing but a metaphor... clumsily cut and pasted into the film.

The movie’s leisurely pace gave me room to remember where I’d seen this story before. Monster’s Ball is The Crying Game, re-set in the American South, where bad men are prejudiced against blacks instead of homosexuals. The hero begins the movie participating in the execution of a man whose wife he will, racked with guilt, decide to befriend and support. As in The Crying Game, these two very different people will fall in love, and of course, the hero’s connection to the execution will remain secret until the end.

But we also have As Good as it Gets here, as Hank and Leticia get to know each other through quick, tense, prejudice-laced exchanges in a diner, while she pours his "black" coffee and serves his "chocolate" ice cream. Perhaps the unflatteringly graphic electric-chair scenes will give the film the added importance that worked for Dead Man Walking.

This is a movie hard-wired for critical acclaim, so loaded with issues that it may have backfired among Oscar voters. While it won Roger Ebert’s "movie of the year" mention, it hasn’t become an "event" film for any reason other than Berry’s occasional state of undress.

But far be it from me to say the film is empty. Heavy-handed and derivative as it is, thanks to its two central performers, it strikes some resonant chords about forgiveness, compassion, and doing the right thing.

The Dish (2000)

[This review was first published at the original Looking Closer website in 2002.]

-

The Dish is one of those rare movies that does not aspire to be anything but short, sweet, and good for the heart. Thus, it doesn't arrive like an "event," and it leaves not with the hoopla of a blockbuster but with the whisper of a rumor. Those who plan their moviegoing by the Box Office Top Ten, or by what gets advertised on television, will miss it. Those who are paying attention and catch it will tell their friends about it like it's a valuable secret.

It's not going to win any awards — it’s biggest recognizable name is Sam Neill (Jurassic Park), in a restrained and understated performance.

It’s biggest special effect is a satellite dish that… well… it sits there, and occasionally swivels gracefully.Read more

Star Wars, Episode Two: a film forum

My coverage of reviews for Star Wars, Episode Two was originally published in the Film Forum column at Christianity Today in May 2002.

•

The previous Star Wars film, 1999's Episode One: The Phantom Menace, has become the most successful of the entire series. Ironically, it is also considered one of the most disappointing — and even despised — adventure movies of all time. Three years have passed, and we now have Star Wars, Episode Two: Attack of the Clones. In this chapter, young Anakin Skywalker starts giving in to his foolish impulses, rejects the counsel of his teachers, and responds to the temptations that lead him on the path of the Dark Side. His primary weakness is his infatuation with the beautiful Senator Padme Amidala.

Most critics are thankfully saying Attack is not a clone of Episode One. But does that mean Lucas has found his "space legs" again? That's a matter of heated debate.

Those religious press critics who have spoken reflect the same spectrum of opinions that the series has generated since 1977. Most are thrilled with the action and effects. Some express reservations about the quality of the writing and the acting. And a few are worried that the messages about belief in the Force are not sufficiently Christian.

Steven D. Greydanus (Decent Films) joins the chorus lamenting the film's weak dialogue and acting. But he has much more to say: "If [Clones] doesn't quite recapture the charm of the original trilogy, it does combine more enjoyable characterizations and dialogue and better paced storytelling with even more dazzling imagery. [Lucas] may have the tone-deaf ear for dialogue of a dime-store pulp novelist, but he's still got the visionary eye of a technological Tolkien, and the worlds he creates are pure magic. When Lucas creates visuals like these, he's doing something quite simply unmatched by anything anyone else in Hollywood is doing, or has ever done."

Greydanus also highlights ethical lessons of the film: "While Lucas's story doesn't touch upon the underlying moral issues of human dignity and the sacredness of human life in its origins, the progression it shows from the optimistic promises of cloning technology to the dehumanizing reality that actually follows remains an evocative metaphor for the false hopes of human cloning experimentation. Whatever Lucas's intentions, his story resonates with the prophetic warning of John Paul II that 'man must be the master, not the product, of his technology.'"

He goes on to praise the film's recognition of celibacy and marriage both as valid, honorable institutions, while the pursuit of dangerous liaisons is portrayed as "living a lie."

Michael Elliott (Movie Parables) says, "I don't think I was alone in wondering if perhaps the steam had gone out of the Star Wars franchise. Nor do I think I'll be alone in celebrating George Lucas's return to form in the highly exhilarating and enjoyable Episode II." He explains, "Clones … has more of a psychological depth to it as it begins to lay out the course of a good man who turns bad. We see the bad seed planted as Anakin Skywalker receives some 'advice' from a false counselor. 'Trust your emotions,' he is told. This … opens Anakin's heart to the temptation of disobedience as he rejects his understood moral code to act out of passion rather than reason."

Lisa Rice and Tom Snyder (Movieguide) caution readers that they should beware of false messages: "Star Wars IIseems to have abandoned the positive, theistic orientation that the first episode seemed to be moving toward at times. Apparently, George Lucas has decided to slightly reinforce the Buddhist leanings of the saga, where the heroes (and villains) engage an impersonal, illogical, spiritual, and transcendent 'Force' in a mystical, partially occult way."

Bob Smithouser (Focus on the Family) offers a few cautionary words about the "theological hodgepodge … reflected in The Force." He also calls Clones "a wild, satisfying adventure" that lacks "the carefree, organic quality of the earlier films. You wish the young actors would just relax, have fun and stop treating the material as sacred."

The mainstream press avoids discussion of the film's "theological hodgepodge," focusing instead on issues of craftsmanship. Those who enjoy Lucas's imaginative environments and who value Lucas's effective, efficient visual storytelling give the film rave reviews, even as they note its familiarly mundane script and wooden performances. But others are unmoved by the sights and sounds, condemning the film for Lucas's failings as a writer and for his work with the cast.

Many scorn the film's romance plot as derivative and dumb. Kirk Honeycutt (Hollywood Reporter) declares, "These two fall in love not because romance sparks but to suit the needs of subsequent movies." Roger Ebert (Chicago Sun-Times) adds: "Padme and Anakin [are] incapable of uttering anything other than the most basic and weary romantic clichés, while regarding each other as if love was something to be endured rather than cherished."

Ed Gonzalez (Slant) faults the flat conversations: "Lucas' toys always look better when keeping mum and waving their sticks around." Roger Friedman (Fox News) says that Yoda "literally saves Episode II from quicksand," but then complains, "What's completely missing … is any jauntiness or sense of fun, camaraderie or purpose. This second generation of Star Wars characters all sound like Keanu Reeves delivering a soliloquy from Hamlet."

"Mr. Lucas seems to have lost his boyish glee," agrees A.O. Scott (New York Times). "[Lucas] … has lost either the will or the ability to connect with actors, and his crowded, noisy cosmos is psychologically and emotionally barren."

And Lisa Schwarzbaum (Entertainment Weekly) says, "Here we are again: not entertained, not nearly enough, by an installment … that exhibits a chill, conservative grimness of purpose, rather than an excited thrill at the possibilities of cinematic storytelling."

But when Schwarzbaum says we, she's not speaking for a large portion of her peers. Some of Episode One's strongest naysayers come away impressed this time.

Chris Gore, editor of Film Threat magazine, writes, "I have been one of Episode I's most outspoken critics for the last three years. [It's] … one of the greatest disappointments in movie history." He agrees that Clones'dialogue is "cringe-inducing." But in spite of this, he's full of praise. "Clones is epic, entertaining, romantic and funny—it is a true Star Wars film. When I walked out of the screening, all I could think of is that I want to get right back in line to see Clones again."

Todd McCarthy (Variety) turns in an rave: "Virtually everything that went wrong in Menace has been fixed, or at least improved upon … The exposition and sense of storytelling are clearer and more economical, all the main characters have significant roles to play, the detailing of the diverse settings is far richer, the multitudinous action set-pieces are genuinely exciting, there is now the dramatic through-line provided by a love story, some of the acting is actually decent, and even the score is better."

"Clones is much better," agrees David Denby (The New Yorker). "Digital invention is becoming grander, wilder, more free-spirited. Lucas and his computer artists have a ball with the climactic scene … The mayhem is delirious fun."

Two weeks ago, David Poland (The Hot Button) wrote, "George Lucas takes a movie world obsessed with CG and big images and tops every single film ever made going away. The story moves in surprising and clever ways as well as in obvious and expected ones." This week, he insists, "No film has ever come close to [Clones'] visual complexity and beauty."

What do the film's fans have to say about the weaknesses? "If it can be easily faulted for cardboard characters and clunky dialogue," writes Michael Wilmington (Chicago Tribune), "then it should be recalled that these are defects of the entire series—which takes most of its cues from the old Flash Gordon serials, as clunky and cardboard as they come. This is visual storytelling of a high order, and though we've heard and seen it all before, it has never been with quite this childlike awe and incredible elaboration. The movie keeps topping itself, not dramatically, but with one pure, explosively delivered, ripely detailed action set-piece after another. This is a landmark film, for technological bravura … if nothing else. Clones celebrates a certain youthful spirit in both moviemaking and movie watching; because it's as much phenomenon as movie, audiences will either ride with or reject it. I was happy to take the ride."

After I stay up for the late-night showing on Thursday, I'll post my opinion of the film at Looking Closer.

Admittedly, Episode One suffered from bad acting and poor writing. Then again, so did 1993's Return of the Jedi. But I have to wonder—isn't griping about bad dialogue in a Star Warsfilm a little like pointing to artificial butter flavoring on movie popcorn? You can state the obvious, but why belabor the point? Lucas's work in screenwriting and directing actors has always been substandard, and critics should indeed acknowledge that. But shouldn't they give more credit to his grasp of visual storytelling and his vision for harnessing technology and using it to free his imagination? These talents seem sorely undervalued and even ignored. Further, it is a rare wonder, the way that moral and spiritual truths are powerfully illustrated and communicated by the Star Wars stories. Like the Arthurian legends he so clearly reveres, Lucas is giving us an alternate history rich with parables.

The Patriot (2000)

This is an archive of one of the earliest Looking Closer reviews. I keep it as a souvenir of the early days (although I hope I've learned a thing or two about writing since then).

•

The Patriot is an ambitious epic, exhausting more for the emotional toll than for its running time.

Mel Gibson inhabits the character of Revolutionary War hero Benjamin Martin with admirable physicality and emotional range. After suffering a personal attack by the British, Martin struggles to control his rage as he leads effective counterattacks on them. The story that unfolds is episodic and formulaic, with few surprises. But it is packed with full-scale battles, sneaky rifle shooting in the woods, and risky strategizing between desperate men. The movie will be a thrill for audiences who like their heroes big and strong, their tragedies multiple and devastating, and their movies simple and straightforward.

Unfortunately, if you’re looking for anything philosophically, intellectually, or historically enlightening, the waters here are pretty thin. It only tells us things we already know, and it repeats those simple truths often and loudly.

A Good Strong Hero

Popular culture has become obsessed with de-mythologizing history's admirable men and women. It is a cynical age. One can hardly imagine what a new biopic on Abraham Lincoln or George Washington would look like. It seems like the only interesting detail about Thomas Jefferson, according to recent re-tellings, is that he slept with a slave girl. Modern art and entertainment is preoccupied with discrediting the honor of great men, or justifying the crimes that made them notorious. The prevalent perspective is that greatness and morality are relative and a matter of interpretation. We make ourselves feel better about our own indiscretions, or those of our current leaders, if we can say "Well, the great men weren't really so great."

I must give The Patriotcredit for striving to give us an admirable national hero... a man who puts his life on the line for family and country. It's good that the big screen still has room for heroes who honestly and wholeheartedly strive to be good men. Seeing the good and the bad in a hero can provide some balanced perspective, but I prefer to zoom in on a character's strengths rather than his weaknesses.

However, I must also add that The Patriot, although it has a well-balanced, flawed hero, swings too close to Nation-worship. It is so caught up in its own salute to one man's nobility, and to the glory of men who fought for freedom, that very little rings true or honest. Early America is painted with too soft a brush. There are, I am informed, historically documented instances of British soldiers as brutal as this film’s villain. There were slaves who have been freed, happily continuing to serve their masters. And there were heroes. But this film gathers these exceptions together into a bundle for the sake of arresting drama. The result is a skewed and misleading portrait of the war and the times.

An Idealized World

The film's greatest technical achievement, its collection of battle sequences, is not necessarily something worth boasting over. There are many prolonged, slow-motion battle sequences that flaunt authentic weapons and innumerable convincing slow-mo deaths. Director Roland Emmerich (Godzilla, "Independence Day") likes to slow down the movie’s epic battles, so audiences can appreciate the exquisite details of the bloody conflicts. While his hero is conscience-stricken about killing, Emmerich sure enjoys serving it up in generous helpings.

Off the battlefield, The Patriot looks more like adventure-novel illustrations than a historic recreation. Our heroes walk through nothing but the most gorgeous scenery. Their clothes never look lived in. They exist in rooms that are free of dust or signs of regular activity. It reminds me of a history play at an elementary school. And the dialogue provided for the characters by screenwriter Robert Rodat (Saving Private Ryan) isn't much more interesting. They speak in bland and ponderous conversations, without any hint of personality or dialect. It makes you long for a script revision by the Coen Brothers or Billy Bob Thornton.

But it's not just the simplicity that bothers me. It is the manipulation. The film doesn't hesitate to grab the most blunt instruments to make you cry, to make you angry, to make you cheer, to make you so emotional that you can't think straight.

Making Sure the Audience Cheers

Right away, Colonel William Tavington (Jason Issacs), the British officer who leads the offense against our hero, is shown to be a sneering rebel, a madman with authority, a sadistic butcher who does not follow the codes of British military conduct. He throws down the gauntlet early, murdering a young boy, one of Martin’s sons. Later he smilingly rounds up a whole village and burns them to death. All he needs is a big black cape and heavy, distorted breathing.

It's true, there were some heinous war crimes in the Revolutionary War. This does not make it fair, however, to stack the deck in this film and call it "historicism". Making Darth Tavington the sole focus of our aggression turns our sympathies with inappropriate force and prejudice against the British. Other Brits — including the orderly Cornwallis — are shown grumbling about Tavington's methods. But Tavington is still the central representative of the British in this film. Everything leans toward giving him what he has coming.

This burning of the villagers in a church is, according to a recent article on Salon.com, a crime that the Nazis committed once, not something the British did. Having used "artistic license" so freely, Emmerich and Rodat are sure to have the audience up in arms, shouting for the death of Darth Tavington. No need to waste time with a historically accurate portrayal when you can just embellish and make the enemy like the Nazis at their peak. That'll rile the crowd up real good.

Emmerich doesn't stop there. He's going to get us teary-eyed if he has to sucker-punch us to do it. So he brings up slavery, something we all agree on, something we all can get emotional about. But he oversimplifies that too.

The one black member of the militia is nothing more than a token here; he doesn't get any lines except as the spokesman for slaves who dream of a free world. The "slaves" that work for Benjamin Martin here have been conveniently "set free" and are so enamored of his spotless family that they serve him "of their own free will." Later, when the Revolutionary War is over, they can't wait to start building a "New World" ... by voluntarily continuing their current servitude instead of pursuing their own families, their own lives.

In fact, any black character in The Patriot is there either to make inspiring remarks about slavery and freedom, or to further accentuate how great the hero is. We don't have to deal with a single, suffering slave in the whole bunch. Once again, the movie is providing us with fuel for emotions, not something to think about, not evidence of the more difficult and complex realities of the time. It is true that there were slaves who chose to serve their masters freely. But here again, The Patriot has given us an exception to the rule because it is more palatable to the audience and heightens the emotional drama. If Martin was portrayed as having slaves that forced us to confront the reality of actual slavery, we wouldn't like him as much. It would have made him more... human. That would have run the risk of asking the audience to think for themselves.

Any storytelling that pretends something complex is actually something simple is irresponsible storytelling and bad art. It is on the complex issue of whether violent retaliation was the best method that Emmerich is most manipulative.

Thou Shalt Violently Retaliate

One scene best sums it up: When a reverend is ministering to his congregation, a soldier walks in and asks men to join him and enlist in the armed resistance. The reverend, interrupted and annoyed, questions whether this is appropriate timing. It is, after all, a worship service. He is quickly admonished. Within seconds, the apologetic minister is shown awkwardly fumbling for his own rifle. "A shepherd must protect his flock," he says, rushing out to shoot the British. Our heroes smile…the poor fool has decided to be a man. The music crescendoes. Clearly, in this movie's moral structure, anybody who hesitates to respond to the British immediately and with violence is misguided. In this saga of men fighting for a free country, freedom of opinion is frowned on. The reverend is not afforded a free will.

Be careful. The movie already has you cheering for the things you agree with. Are you sure, though, that you agree with this? Is this particular issue so black and white?

Nobody gets to question the morality of the colonists’ violent opposition...except Benjamin Martin. But his hesitation at the film’s beginning is shown as fear and worry over his family, not a true moral conviction about violence. Later, when the violence has hit home, he says he is ashamed about doing nothing. Again, we are told that the cost of warfare makes it a moral imperative to become violently involved.

There are often other ways of dealing with oppression. If there aren't, why didn't Christ urge the oppressed Jews to take up arms? I’m not saying pacificism was the colonists’ best option; I believe, though, we should respect and consider the thoughts of those who examine other ways of retaliating.

Mel Gibson as... Mel Gibson?

A fellow critic has persuaded me that The Patriot is a more responsible film than Braveheart. (The hero actually resists the pull to get revenge.) But because it follows the basic Braveheart formula, there's not much new here. The battlefields look the same, except for the uniforms and weapons. And the music sounds the same... big, patriotic, and John-Williamsish (this time it IS John Williams.) In spite of his attempts to vary his roles (Payback) Gibson has become predictable in action movies. They become countdowns to a bloody showdown and a pious speech. It worked best in his performance as Hamlet. (He’ll never find a better screenwriter than Shakespeare!)

Benjamin Martin, in this film’s portrayal, is a dutiful man, bound by honor to family and country. But he is haunted by his past war crimes, and his conscience is strong. We do see one particular moment when that old monster within him reawakens against the British, and for a moment the film comes to life with a frightening brilliance. Our hero act inappropriately. But even this loses its sting, merely because of who we are watching. It might be a character flaw for Benjamin Martin, but it's what Mel Gibson does best. As any Gibson Guy must do, Martin remains restrained until the breaking point. Then the camera zooms in on Gibson’s best trick... the eyes dull, the face drains of expression, and the animal takes over. Mad Max has returned.

Not only that, but Benjamin’s eldest son Gabriel (Heath Ledger), who provides the obligatory love story (another important part of the film's well-worn formula), appears to make his debut as the next Mel Gibson. We love Gabriel because he's an echo of classic Gibson...the rebel with a cause who gets the girl, has his own revenge score to settle, and his own glorious bloody showdown. Two Mad Maxes for the price of one!

So if you want another Mel Gibson-brand epic, with simple, dramatic, noble gestures… this is your movie.

But if you want a truly inspiring film about war, nobility, and freedom, rent Kenneth Branagh's adaptation of Shakespeare's Henry V. With less than half the budget, and with language that's delicious to recite, Branagh will inspire you to be a patriot of great character. Roland Emmerich knows a cannon can do a lot of damage, but Shakespeare knew that a well-crafted speech can inspire a thousand soldiers.

Forgive me if I am a bit impatient with this film. I am weary of seeing the same movie, with minor variations, played over and over again. Sure, these are moral heroes and detestable villains. But so what? This year's Gladiator had a little life in its dialogue, and a few pleasing new twists, but, like The Patriot, it still boiled down to this: "You killed someone in my family... so I will, eventually, impale you on something." In the name of freedom. Of nobility. Of America. Of Ireland. Of Rome. Or whatever. It all boils down to an endorsement of violence as a way to resolve differences. Today's history lesson: History goes on teaching us nothing.

Max (2002)

[This review was first published on the original Looking Closer website on May 12, 2003.]

-

Noah Taylor is best known for his charming lead role in the romantic comedy Flirting, and more recently made memorable marks on Almost Famous and Vanilla Sky. Now he’s starring as the most notorious monster of the 20th century.

Max dares to delve into the life of Hitler in the days before the Holocaust, and Taylor is scarier than any orc in his intense performance as Adolf. His performance reveals a bitter, wrathful, prejudiced, and explosive young man torn between his desire for an audience and his mediocre talents as an artist.Read more

The End of the Affair (1999)

[This review was first published at the original Looking Closer website in 1999.]

-

The End of the Affair takes us back to London in wartime. There, we're told a story in which the echoes of air raid bombings leave scars on history and hearts.

At first, it might sound like the tale of a simple love triangle: The wealthy and beautiful Sarah Miles (Julianne Moore) betrays her boring husband Henry (Stephen Rea) and begins a passionate affair with an obnoxious novelist named Maurice Bendrix (Ralph Fiennes). But then, a most unlikely fourth party becomes involved... none other than the Almighty himself.

This turbulent story finds its epicenter in a key moment when the war collides with the lovers during a secret rendezvous. A sudden and dramatic turn leaves Maurice in grave distress, and Sarah turns to God for help. It's the film's most profound and vivid scene... she kneels so that we only see her clasped hands, and she makes a desperate bargain with God.

And God answers.

If God were to grant you a request as directly as He does for Sarah here, it would be difficult for you to shake your newfound assurance of His presence. The End of the Affair gets its title from the fact that it changes Sarah tremendously. But the biggest flaw in Neil Jordan’s movie is how severely it contradicts the core of Graham Greene’s novel, how it lets the affair in question continue after this point, whereas in the book this event truly marks "the end of the affair."

In the novel, Sarah is changed forever. In the film, she is far more fickle; although she remains aware of God, she continues to behave in a way that is displeasing to Him.

What is strange about this movie adaptation of The End of the Affair is just how far director Neil Jordan went to alter the last chapters of the story. (I owe thanks to Peter T. Chattaway for sending me excerpts from the novel demonstrating this divergence; I haven't read the entire novel for myself.) I cannot go into great detail about the changes without spoiling what surprises the film has for you, but I will say that what might have been a story about the long hard but rewarding road of virtue becomes in the film a confusing and contradictory muddle of broken promises, lies, prayers, attempted corrections to behavior, and then backslidings.

The film wants to make grand statements about something, but about what is unclear.

Are we supposed to hope Sarah stays true to God, or to Maurice? Or do we hope her husband has a change of heart and tries to reinvigorate their marriage? Neil Jordan seems to be primarily interested in having excuses to put the two lovers in bed for long athletic bouts of sex. And yet, even there the characters are joyless, acting rebelliously as though proving a point rather than proving their love.

Jordan's approach betrays what might have been a powerful story.

Maurice Bendrix is clearly a villainous man; he cheats, he lies, and his obsession is so intense that he shows little care for Sarah's troubles or questions. He drives her to yet another failing that fills her with guilt before God.

Julianne Moore's performance is very strong as a woman at war with herself, torn between loyalty to God and desire for her lover. She makes Sarah seem courageous to deny her lust and turn away from the affair. But Jordan's revisions rob her of this nobility in the end, making her fickle and celebrating her compromises. She is left weeping in a church telling God that she just can't keep her promises. Later, when her "goodness" brings about an honest-to-goodness miracle, it's hard to understand, since she's already given up on virtue. In the novel, it must make more sense... she remains true to God in spite of hardship, and her sacrifice prompts a miracle and hardens her angry lover's heart against a God in whom he claimed never to believe.

So why does the movie try to convince us that the parting of these lovers is a tragedy? To all available evidence, they were bad for each other from the start.

What a sad and melancholy piece of work. The marvelous Stephen Rea as Henry is allowed only to mope and feel sorry for himself. His monotone monologues make him a prime candidate for a Prozac prescription; at least he'd be a more cheerful weakling. As Maurice, Ralph Fiennes basically reprises his English Patient role as the heroic destroyer of covenants and promises. He gives Maurice a prominent forehead that seems to emphasize his bone-headedness. He's supposed to be a good novelist, but his romantic overtures sound like the work of a smitten freshman doing homework for Poetry 101. And the affair itself, like that at the center of The English Patient, seems more foolish than tragic, because all that binds these two characters is carnal desire.

To make matters worse, what I suspect will be remembered as Michael Nyman's most overbearing soundtrack works hard to lend pathos and tragic heroism to the lovers' dalliances. The backdrop of relentless rain makes the proceedings more dour, and the cinematography shows us a grim and un-romantic London.

In fact, the only scenes that carry any laughter or lightness are those that feature a private detective named Parkis. Employed by Henry and Maurice to discover Who has stolen Sarah's heart, Parkis tries to relate his discoveries to his employer. Ian Hart (Backbeat) plays Parkis perfectly. He's a nervous wreck, so scared of his own need for love that he uses detective work as an excuse for voyeurism. Parkis is a prisoner of British manners who can't just say "I found her crying..." but instead stammers "Tears were an issue." I found myself wishing for another movie in which Parkis was the main character, living out a comically miserable existence running errands for these selfish and sour lowlives.

It seems Neil Jordan, who in interviews has talked in a detached way about God being the greatest "invention" humans have created, exhibits a hard heart toward God and religion in this film. This is disappointing. Jordan has told such powerful stories of compassion and forgiveness in his finest works, The Crying Game and The Butcher Boy. In the novel, it seems Graham Greene is wrestling with his own personal experience and the guilt of having been unfaithful (the book is said to be based on his own wartime affair.) In the film, the perspective seems very much that of Maurice, who sometimes refuses to believe in God, while at other times lashing out at God as a scheming entity who robs us of our desires.

Any honest believers will admit that they suffer lapses, or at least challenges to, their faith. All of us get angry with God from time to time when things don't go our way. But this is evidence of weakness, of selfishness. This is the state of the child angry at his parents because he wants to be the center of the universe, and in fact, he isn't. This is not a state to be championed, glamorized, or celebrated. It does not make heroes out of men. And I don't feel sorry for Maurice or for Henry, as the film wants me to, when they don't get what they want.

The End of the Affair leaves me wishing that Maurice and Henry... and Neil Jordan, perhaps... discover the rewards of a "giving" kind of love, rather than stewing over what they didn't "get" out of self-serving obsession.

-

Writer and director - Neil Jordan; based on the novel by Graham Greene; director of photography - Roger Pratt; editor - Tony Lawson; music - Michael Nyman; production designer - Anthony Pratt; Sandy Powell - costume designer; producers - Stephen Woolley, Neil Jordan. Starring - Ralph Fiennes (Maurice Bendrix), Julianne Moore (Sarah Miles), Stephen Rea (Henry Miles), Ian Hart (Mr. Parkis), Jason Isaacs (Father Smythe), James Bolam (Mr. Savage) and Samuel Bould (Lance Parkis). Columbia Pictures. 105 minutes. Rated R.

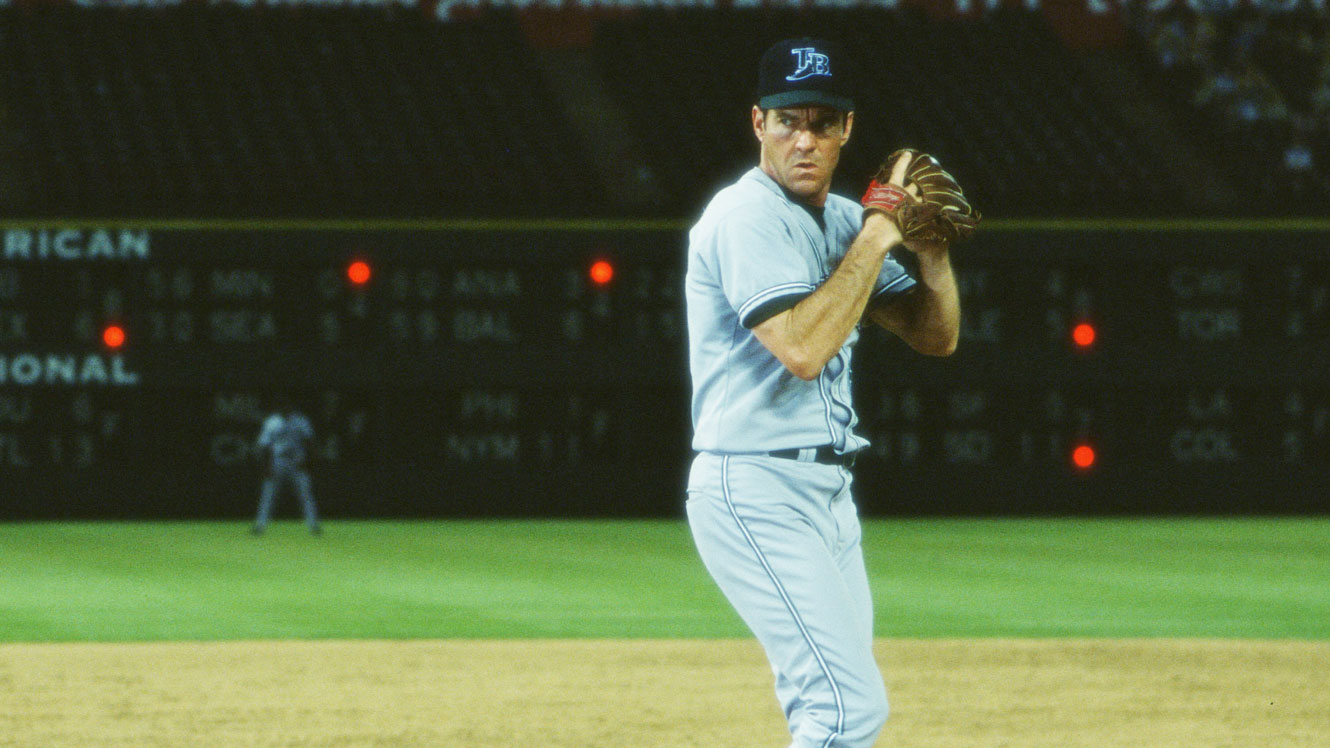

The Rookie (2002)

I’m not much of a baseball fan. I’m not much of a Disney fan. But The Rookie surprised me. Not only is it the best Rated-G movie for grownups since The Straight Story… it boasts what will be remembered as one of the best performances of the year.

Dennis Quaid plays Jim Morris, a middle-aged Texas schoolteacher who tried to turn turn pro-baseball pitcher long after most men would have given up. Endearing, understated, full of humor and angst, Quaid's performance may be the highlight of his impressive career.

Director John Lee Hancock, whose most significant work previous to this was the script for the uneven drama A Perfect World, has done everything right with this film. He’s walking a well-worn path, daring to tell yet another tale about a guy who never thought he could make the big leagues. But this adaptation is grounded in facts, and Hancock is careful not to embellish things to make the crowd happy. He moves us without sending Hancock to the World Series and without giving him any bottom-of-the-ninth victories. The tears and the thrills come from moments of character development, not moments on the scoreboard.

Hancock gets strong work out of cinematographer John Schwartzman and the editors. They avoid quick-cut action and give community baseball the light, pace, and feel that it really has. After the movie, I found myself itching to take some friends to the park with a baseball and gloves, just for conversation and catch. When the camera goes to the big leagues, Hancock’s perspective gives us the right feeling of awe at the vast stadium, the hot white lights, and the size of that green green field. He even takes time to show us how long it takes to run from the bullpen to the pitcher’s mound. I’ve never been to a professional baseball game, but I’m pretty sure now that I know what it feels like.

Jim Morris’s story deserved to be told, as likely as it was to become a sappy, sentimental button-pusher. The guy dreamed of the big leagues all through his childhood. He got close with some impressive 85 m.p.h. pitches, but then hurt his shoulder and was told by the doctors not to pitch anymore. So, disillusioned but not self-centered, Morris humbly went to work, like so many Americans, at jobs that weren’t part of his dream. And he built a rewarding life, one that would have been rich and meaningful even without the miracle.

But the miracle was quite a bonus. Morris, encouraged by his students to give his dream one more shot, discovered that surgery had somehow improved his arm. And what happened post-40 was so unlikely that he almost turned back out of fear… fear of what success might do to the life he had built brick by brick.

I was deeply moved by The Rookie’s honesty and grace — not words I would usually use to describe formulaic Disney product. The term "formulaic" is not a compliment. Many films (especially Disney films) are lazily produced because the filmmakers are banking on the success of a predictable formula, which they follow without bothering to enhance it. It takes the touch of an artist to invigorate a familiar outline with fresh ideas, or to use metaphors that make the work resonate on different levels. The Rookie is one of those rare, wonderful "formula" films that tells its story with earnestness, believability, attention to detail, and fully developed characters. It favors understatement over exaggeration, subtlety over sentimentality (although occasionally it lets the syrup flow.) Even in the "familiar" moments, the filmmakers restrain the music, effects, and close-ups that routinely command us to weep. Instead we have that uncomfortable feeling of watching real people in quiet, intimate, life-changing moments.

My thanks to whoever it was that let Hancock take his time, spreading this relatively simple story over two-hours-plus, so we could become acquainted with all of the supporting characters. Rachel Griffiths makes Morris’s wife a believable, tough, hard-working, naturally sexy woman. Bryan Cox brings a rough likeability to the role of Jim's father, even though he comes closest to filling the stock role of a villain. And the kids are believable too. These aren’t the perfect, always-happy never-a-problem cabbage patch dolls that played Mel Gibson’s kids in We Were Soldiers. The Morris baby bawls and tries their patience. And Hunter, Morris’s young son, is given a unique sense of humor when his wide-eyed admiration might have quickly become the stuff of cheap television drama. Hancock’s patience with his actors allows them to find moments of convincing humanity. We feel we could travel to Texas and meet these people, browse antiques in their dusty shops, and pull up a chair in their warm meat-and-potatoes homes.

There is a startling moment near the film’s conclusion when Morris grabs hold of his wife’s hand and looks at her with an expression of amazement and gratitude. We're looking at him, waiting for permission to celebrate his achievement. But no. He doesn't say a word. He just looks up in amazement. The credit for this miracle does not belong to him. It belongs elsewhere... with those who coaxed him and helped him get there. It is in no way the Hollywood moment you’d expect — it turns our attention away from Morris and reminds us of the powers and miracles that brought him to that place. It rings true.

Morris is not a big screen hero in the "I did it my way" tradition. His achievements are the result of a cooperative effort that emphasize how we are all role models for each other — parent to child, husband to wife, teacher to student … and sometimes even students to teacher.

The Rookie, against all expectations, is one of the finest family films to come along in the last decade. (It will have to be a rather incredible year to push this one out of my year-end Top Ten list.) One can only hope that the folks who gave this one the green light will recognize why it works so well. If they do, then hopefully we can look forward to more films as finely crafted as this. And I’d add this request for any filmmakers out there: Would you please continue offering Dennis Quaid parts as rich as this one? He deserves them.

The Rookie (2002): guest review and film forum

The following review was contributed to Looking Closer by guest reviewer Ron Reed, and the Film Forum was published at Christianity Today.

•

Ron Reed:

Your grandfather once told me it was okay to think about what you want to do until it was time to start doing what you were meant to do. That may not be what you wanted to hear.

When there's an envelope taped to a birthday present, you pretty much know what's going to be inside, but that doesn't mean you don't open it. This movie's a lot like that: it's an inspirational greeting card of a movie – in its look, in the shape and style of its storytelling, and in its "follow your dream" sentiments. But that doesn't mean you shouldn't bother watching it.

When a film sets out to tell the story of a high school science teacher and baseball coach whose uninspired players make him a promise to try out for The Bigs if (against all odds) they win the championship, chances are this story's going to run the base paths in pretty familiar fashion. And when Coach is a guy who hangs a medallion of Rita, patron saint of impossible dreams, from the mirror in his pickup truck, it's pretty much preordained that things are going to work out.

The real surprises come in how this movie gets where it's inevitably going, in the attention it pays to the difficulties human relationships go through in the pursuit of dreams – whether they also happen to be divine callings or not. One of the people at the centre of Jim Morris's life is his father, a preoccupied man made over into the image of the military that owns him and directs his steps: the accomplishment of the movie-makers is not to leave Dad and son stuck there, but to track that troubled relationship on into adulthood, without falsifying it. When the elder Morris advises his son to do what he is meant to do, I couldn't help remembering a similar conversation with my own mother as I faced a decision whether to go into the ministry or to pursue the life of a theatre artist. I wonder if it's just a personal reading, or whether this father's advice doesn't ultimately convey something about the inevitability of living out one's vocation – particularly one that's being steered by the unstoppable Saint Rita and the prayers of a pair of Texas nuns. (On her deathbed, Rita was asked by a visitor if she'd like anything brought from her home town. She asked for a rose. The visitor returned to the family estate, frozen in the middle of winter, and found a single blossom on an otherwise bare rose bush.)

The other central character in this man's life is his wife Lorri, and Rachel Griffiths' portrayal truly provides the centre of gravity for this film. What an actress! She charges the standard-issue strong-but-supportive wife role with tremendous electricity and presence, and every one of her big scenes is filled with unspoken nuance before or between or after the lines – check out her exit from the porch after the talk about their son, her reaction to the sport coat call, or the scene where she finds her husband in the bullpen. I hear she's a regular on Six Feet Under. Almost makes me consider watching television.

For all its too-handsome instant-nostalgia look, the film gives us lots of specific detail as well. The family's arrival in Big Lake, Texas is marked by "Bang the Drum Slowly" on the theatre marquee. Elvis sings the gospel-tinged "Midnight Rider" as Morris throws BP. The high school ball games may be predictable in serving exactly the plot functions we know they'll have to serve, but they also feel like ball, and not Big League TV ball either. Jim's son wears his rally cap at a key moment in the game, and we realize that he's getting the kind of fathering his dad never got. It's a treat to see this ordinary father arrive at try-outs beleaguered by the minutiae of baby maintenance, and I appreciated the light touch about the "miraculous" increase in this washed-up pitcher's fastball. I love the concision of that next-to-final shot, summing up this man's life and calling in the high school trophy cases, and then the final image of nuns scattering flower petals – they're roses because of Saint Rita, and they're yellow because, well, this is Texas!

I'd recommend this movie for families to watch together – it's a well-made, positive story with faith elements that can provide an entertaining evening together or some great conversation about real questions of vocation or the miraculous. Still, I can't help thinking the writers let us down with this treatment of the true story of Jim Morris's improbable shot at the major leagues – could it be that shrinking the role of faith to a good luck amulet and one pre-game prayer session denies us any sense that Christianity offers anything more than a mix of destiny-shaping magic and civic religion. Does God serve no more role in this believer's life than to provide baseball miracles at the request of some long-ago nuns? Is that what authentic personal faith looks like, or is it just a Hollywood kind of shamanistic superstition?

But most of the time I'm just glad that Hollywood can make a baseball movie – and this is very much a Hollywood movie – that's also about the hard work of marriage and parenting and being parented. More surprisingly, it doesn't feel obliged to negate the power of God that worked in this man's life. In The Rookie, God may be on the bench, but at least He's allowed in the ballpark.

•

Film Forum on The Rookie

Until now, screenwriter John Lee Hancock was best known for penning A Perfect World, directed by and starring Clint Eastwood. But this week Hancock has delivered a rare gift to moviegoers, a G-rated family film that has audiences cheering and critics raving. Many are saying Dennis Quaid gives the best performance of his career in the leading role. In fact, The Rookie is the most acclaimed G-rated film since David Lynch's The Straight Story.

Sources say very few details in this true story have been altered to please the crowd—there's noBeautiful Mind revisionism to make a fairy tale out of difficult fact. Hancock and screenwriter Mark Rich found the tale of Major League Baseball pitcher Jim Morris powerful enough to inspire audiences without adding sentimental glop. And what a story: Morris surrendered his baseball career and his dreams when he injured his shoulder and doctors told him he'd never get his impressive abilities back. So he built a new life as a husband and a father, a community baseball coach, and a high school chemistry teacher. That's remarkable on its own, but when Morris's students challenged him to chase his dream one last time, he went for it. At 40 years old. And the dream came true.

Sports movies are too often tailored to convince us that all we need is willpower and a dream. The Rookie could easily have become a cliché about the glory of sports. But moviegoers testify that above all this is a story about the power of supportive and encouraging families and communities to make unlikely things possible. While this spoils the myth of the independent, self-sufficient hero, it offers a far healthier example to those chasing dreams of achievement and excellence.

Michael Elliott (Movie Parables) is inspired by the story. He writes that Hancock and Rich "do lay the schmaltz on a bit thickly. But, to their credit, they do replicate the small town flavor of a community bound together by the personal heroics of one of their own. The way the people important to Jimmy rallied around him, encouraging and exhorting him to go forward to achieve his goals … is exactly how members in the body of Christ are to help one another."

In a review appearing online today, Douglas LeBlanc (Christianity Today) highlights "the film's prevailing theme of grace coming into the lives of people who pursue their dreams with courage and love." LeBlanc argues that Morris's quest for the major leagues is "less interesting … than the back story written by Mike Rich. Morris's father is so emotionally repressed that he cannot touch his son even in a moment of athletic triumph. Character actor Brian Cox brings subtlety to a role that he could have easily overplayed. The tentative steps toward reconciliation between father and son make the G-rated Rookie a worthwhile outing."

Jamee Kennedy (The Film Forum) calls it "a triumph of heart and soul and a wonderfully uplifting movie. Although the film's promos drip testosterone-laden baseball action, this film is really all about second chances and what we do with them."

The U.S. Council of Catholic Bishops calls it an "uplifting charmer. In spite of a few sags in momentum … Hancock's film pulls on the heart strings … while pleasing and inspiring without the slightest suggestion of violence, sex, or even a crude word."

Bob Smithouser (Focus on the Family) says the film "celebrates hard work, community, perseverance and the need for spouses to share a common, unselfish vision for their home. Also, there's a sharp contrast between healthy and unhealthy approaches to fathering. The Rookie is guileless entertainment with lots of heart and plenty for parents and teens to talk about."

Holly McClure (Crosswalk) calls it "one of the best baseball movies ever made. Much more than just a story about the sport, it's a testimony that God can give second chances in life no matter how old a person is. This one will go on my list as one of the top ten movies this year, and I predict it will be a huge hit!"

Lisa Rice (Movieguide) says Dennis Quaid "gives an excellent performance. [The Rookie is] so well made, that it should win many awards. It also serves as a telling example to Hollywood that clean … pro-family movies can be the hottest ticket in town."

Douglas Downs (Christian Spotlight) responds euphorically: "Christians and people that value high morals need to support this film. Let's create some positive buzz!"

Some Christian critics prefer to focus on what the movie doesn't have. Mary Draughon (Preview) writes, "It's heartwarming to see an entertaining, feature film about a loving family. The Rookie's glaring absence of sex, violence and foul language … adds to its charm."

Even hard-to-please critics in the mainstream press are won over. Stephanie Zacharek ofSalon.com writes, "The idea is sentimental, but Quaid dries all the sappiness out of it. There's something in his face that suggests both contentment and restlessness, but even more important, the sense that it's perfectly natural (and understandable) for the two to coexist in all of us. That's what makes his moments of joy—the swollen music on the soundtrack notwithstanding—seem pure and wholly believable."

Kirk Honeycutt (Hollywood Reporter) says it "derives its power by sticking to the facts."

Jeffrey Wells (Reel.com) finds it a rare treasure: "Comparisons have been made to Remember the Titans, but that film was 'entertainment' … [it] used every trick and ploy it could think of to stir the emotions. [The Rookie] works its peculiar magic without seeming to milk, shovel, or pull any one's chain."