The difference between Gandalf and Saruman

I grew up in a Baptist church. There were a lot of good-hearted people there. I'm still in touch with some of them.

But at 14, I began to smell, in that community, a certain stench.

It wasn't the hairspray of the church ladies who sat in the pew in front of me — although that was a poison as suffocating as the fallout of nuclear explosions.

No, it had to do with a fear of those in the world around us who believed differently than we did, who laughed at our faith and our Gospel and our traditions. And that fear manifested itself in seeing cults and conspiracies everywhere; in condemning artists whose love for mystery was, we presumed, actually a reckless opening of their souls to the devil; and in a ravenous appetite for money and for political influence.

I remember several Sundays in which a banner was draped across the front of the sanctuary, and each week it announced a dollar amount that congregants had given in a church fundraising campaign. It wasn't celebrating the generosity of God's people toward serving the poor. It was a campaign for a larger building on the church property for offices and activity rooms. And it made me uncomfortable — to raise my eyes from prayer and see dollar signs.

I also remember feeling uncomfortable during sermons that prioritized judgment over grace, that ranted against the evils of pop culture and "liberalism." There was more said about the evils of "culture" than was said in observant interpretation of the Scriptures. I learned that the Bible was something you sifted to find individual lines that would back up opinions you already held, not something to study to understand what it meant in its context and history.

In my church and the others that I visited — all Protestant Evangelical churches (Catholics and Episcopalians were not to be trusted; they were too mysterious and sensual in their inclinations) — the arts were primarily discussed in terms of their corrupting influence.

I bought into this for a while. I remember how I, during the turmoil of my teens, stood up in church to rant against the evils of rock music that my friends enjoyed. I was haunted by missionaries who had visited our church to tell us that the drumbeats of rock music originated from demonic practices in Africa, and that the very sound of them could inspire demonic influence in me. Wanting and enjoying the pats on the back and the approval of my community, I was ready to go to extremes. It felt good to rant against imaginary enemies.

I lived in fear. An exhilarating, self-righteous fear.

•

Meanwhile, the arts within the church, when they were acknowledged at all, were characterized by mediocrity and a sort of sentimentality that exalted a white, middle-class, European heritage — you know the paintings I'm talking about — and not the kind of awe-inspiring and discomforting beauty that distinguishes great and timeless art.

I was bored with Christian art. I felt guilty about it, but the music that "Christian artists" badly and jealously imitated was so much more exciting when it was new and fresh on "secular radio."

I began to succumb to the gravity of beauty over didacticism, of mystery over zealotry. I came to favor exploring questions over preaching answers.

And in time, the affirmations of God's glory that I found in the arts — which spoke to me so much more powerfully than culture-slamming sermons — made an arts critic out of me. Instead of keeping diaries, I wrote reviews (mostly for myself) in which I recounted glimpses of Jesus' teachings in the creativity that stimulated my imagination. I wrote for that audience of one because writing was a more focused way of thinking; it was better than just reacting.

This strengthened my faith. I wanted to highlight how the teachings of Jesus were alive in the music, the stories, the poetry, and the movies that attracted and inspired people. God's glory, I found, is alive and well beyond the walls of the church — in culture and in nature. And I heard Jesus observing the same thing in his own sermons and stories.

I wanted the Gospel more than ever: a wild, liberating experience of love and grace and reconciliation. Not an angry subculture. Not a resentful congregation, maneuvering for political influence in order to legislate morality, advancing agendas that would make sure "they" were properly punished for their immorality. (Apparently God's promises of justice were not fast enough or severe enough.) I saw that they would rather condemn the poor in our neighborhood for their "dirty" language, and drive them out of the neighborhood, than listen to what such desperate language was actually about: suffering, frustration, longing, and need.

It does not surprise me, but it breaks my heart, to see how so much of what is called "the Church," and how many who call themselves "evangelicals," are throwing out all they ever said about "character" in their raging sermons. For so many years they spewed wrath against, for example, Bill Clinton for his sexual infidelity. They lamented the sinful lifestyles of celebrities. But now, they pledge allegiance to a compulsive liar; a boastful misogynist; one who brags about sexual assault and then refuses to repent when exposed; a man who wants a return to the days when African Americans who protested "were shot"; who wants to deport millions of immigrants; a cartoonish extremist for the cause of egomania and greed.

What happened? Why the collapse of those non-negotiable standards and convictions?

Because he bought them. He bought them with promises of political influence. He smelled their gullibility, and he pounced.

Does anyone think that those who are skeptical about the integrity of the church are blind to this?

•

Remember when evangelicals condemned Martin Scorsese's movie The Last Temptation of Christ?

I remember a huge pamphlet I received from James Dobson in which I learned all of the crimes against God that the movie contained... it was remarkably detailed. And, when I decided to check its accuracy against the film itself, it turns out that, while the film is far from perfect, most of the "offensive details" either didn't exist or where entirely misunderstood.

The scenes that drew their most wrathful objections were actually scenes in which the devil shows Jesus a life-story alternative to dying on the Cross. The devil promises him the comforts of what looks like a successful human life — a path that would lead him away from risk, hardship, suffering, and sacrifice. Many rightly cringed at the sight of the son of God getting down off the cross, sleeping with a prostitute who has a crush on him, and living happily ever after.

But you know how that movie ends? Jesus sees right through that vision. He sees the hook within the bait. He sees the lie in that temptation. And he triumphantly rejects the devil's temptations to compromise. Rather than seeking worldly influence, he chooses, instead, to suffer for the sake of the poor, the sick, the lost, the vulnerable, and the needy — to be the one who will bear the world's worst tortures so that the suffering can see just how far he will go to remain faithful to them. That is his victory. He overcomes fear — even fear of pain and death. And God makes of him the name that is above all names.

The very evangelicals who condemned The Last Temptation have now given in to the very same temptation. Rather than suffer for the sake of the Gospel's integrity, they have embraced someone who, they believe, will deliver them from evil. They have let fear drive them to anger, and anger drive them to opportunism and compromise. They have lunged for offers of privilege, resources, and political influence from a man who seems to enjoy behaving like a devil in public. And now they are uniting to condemn those within their denominations who insist on faithfulness to Jesus's teachings — like Russell Moore of the Southern Baptist Convention — because the truth exposes their failing.

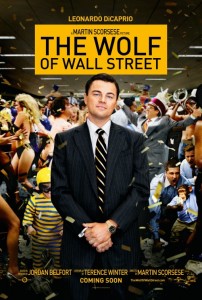

By the way, speaking of Martin Scorsese movies condemned by evangelicals...

These same evangelicals condemned his recent movie The Wolf of Wall Street — a movie about a greed-driven liar, cheater, and womanizer, that exposes the shocking excesses, indulgences, and crimes that the very rich routinely commit with impunity.

And who now do these evangelicals support for President? A man who behaves in public just like "the Wolf of Wall Street" behaved behind closed doors. Why? Because he promises them "perks." That's how this Wall Street wolf gets what he wants — he tosses treats to the sheep to win their support, because it will benefit him in his lunge for power.

Who do these so-called "evangelicals" think they're kidding with their claim to be "Pro-Life," while their candidate of choice fans flames of racial and religious hatred that will, in time, cost so many more children of God their lives? This man is already boasting — boasting — about how his campaign promises and rallying cries were lies meant only to build up his following, and that he never really meant them. And the crowds he's insulting? You can see them on the same screen, even as he admits these things, and they go on smiling and cheering — as he mocks them for their gullibility.

Those are the faces that young people will remember as "evangelicals."

And those are the faces that made me, even at 14, want to follow Christ into the kind of faith that I had heard about in the hymns we once sang in that Baptist church... like this one:

’Twas grace that taught my heart to fear,

And grace my fears relieved;

How precious did that grace appear

The hour I first believed.

•

I have so often been asked, by non-Christian friends, why the ongoing evils of the church don't convince me to leave Christianity behind. It's a good question. I have seen some of my closest friends abandon Christian faith — on one occasion, the closest friend I had in all the world — because of the hypocrisy, the judgmentalism, the self-righteousness, and the hard-heartedness of so many American evangelicals.

But that's the thing: None of the church's compromises and failures put a dent in the actual Gospel. They only confirm its glory by placing themselves in contrast to it.

"Evangel" means "Good News."

"Evangelical" is supposed to mean "bringer of the Good News."

And the "Good News," properly represented, lights up a blaze of joy among the poor, the suffering, the neglected, the immigrants, the alienated, and the outcasts. It makes clear to everyone that they don't need to proclaim that their "lives matter" — it persuades them beyond a shadow of a doubt that they do matter. It attracts them like a magnet. It doesn't repel them, or increase their fear for their safety.

Jesus himself told us that "many will come in my name and deceive many." He reserved his sharpest rebukes for those who dressed as representatives of God, but who didn't like how he embraced those whose lifestyles offended them, and who would eventually sell him out for money and privileges that would help them maintain the illusion of religious authority.

•

I may someday suffer for having published words like these. I have no illusions about that.

Jesus promises that those who follow him will suffer at the hands of those who desire and obtain power and authority.

Remember A Man for All Seasons?

Remember how the church turned against one of its own who dared to stand alone in faithfulness to the Good News? Who do we remember and honor today?

Remember The Lord of the Rings?

Remember how Gandalf refused to reach for the power of the Ring? We stand in awe of that character for how he rejected awe-inspiring power because he knew that it would corrupt him and make him more dangerous than anyone.

It's what distinguished both Gandalf and Galadriel from Saruman, who thought that an alignment with Sauron would help him get what he wanted.

If you follow Jesus, then you find yourself too intoxicated by the joys of selfless love to consider compromising that in the pursuit of power.

That's why it's a rare marvel when we see someone of political influence who distinguishes himself or herself by their devotion to the poor. If you follow Jesus, then you find yourself welcoming and supporting immigrants; serving and living among the poor; and supporting those who are so exploited and abused and persecuted that they have to carry signs insisting on the basic truth that their "LIVES MATTER." (Why would you feel compelled to insist on such a thing, unless the world around you had beaten you into almost believing that your life doesn't matter?)

If you find your heart is breaking for those who cry out in protest over their mistreatment, then — even if you don't think you're religious — you are close to Jesus. Much closer, anyway, than those who pray loudly in his name and then make deals with liars who, day by day, break down a nation's hard-won civil rights, align themselves with tyrants who commit war crimes (like bombing hospitals); and give hope and new ambitions to those who would commit hate crimes and advance white supremacy in America.

•

These are the words of Donald Trump's director of African American outreach (which means "former reality TV star," but whatever), pledging devotion to a man who has shown open contempt for African Americans.

These are the words of Donald Trump's director of African American outreach (which means "former reality TV star," but whatever), pledging devotion to a man who has shown open contempt for African Americans.

She says: “Every critic, every detractor, will have to bow down to President Trump. It’s everyone who’s ever doubted Donald, who ever disagreed, who ever challenged him. It is the ultimate revenge to become the most powerful man in the universe.”

Of course, she's just talking like Trump himself, who said this a few months ago: "Politicians have used you and stolen your votes. They have given you nothing. I will give you everything. I will give you what you’ve been looking for for 50 years. I’m the only one.”

Remember — this is the man that James Dobson, a hero in my childhood's Baptist church, just endorsed in Christianity Today, and described as being "tender to things of the Spirit."

•

Put on the full armor of God, believers.

Because days of testing are upon us, and they will only intensify. The full armor of God isn't military armor. It isn't political influence. It isn't Braveheart's war paint, his bloodthirsty vengefulness, or his "righteous" anger.

It's this:

Stand firm then,

with the belt of truth buckled around your waist,

with the breastplate of righteousness in place,

and with your feet fitted with the readiness that comes from the gospel of peace.

In addition to all this, take up the shield of faith, with which you can extinguish all the flaming arrows of the evil one.

[Notice: We are not called to shoot arrows, but to extinguish them.]

Take the helmet of salvation and the sword of the Spirit...

Aha! We're to take up a sword, right? God wants us to strike!

...which is the word of God.

Oh. Right. What is the Word? It's the Gospel. It's Christ himself, who tells Peter to put away his knife, who heals the wounds of his enemies, and who then opens his arms to all of the punishment that a fearful world can throw at him. That is our sword. Unconditional love.

And then what does Jesus ask us to do, once we've suited up?

Pray. Not for the favor of a corrupt President. But like this...

"Forgive us our trespasses as we forgive those who trespass against us.

And lead us not into temptation.

But deliver us from evil."

Amen.

•

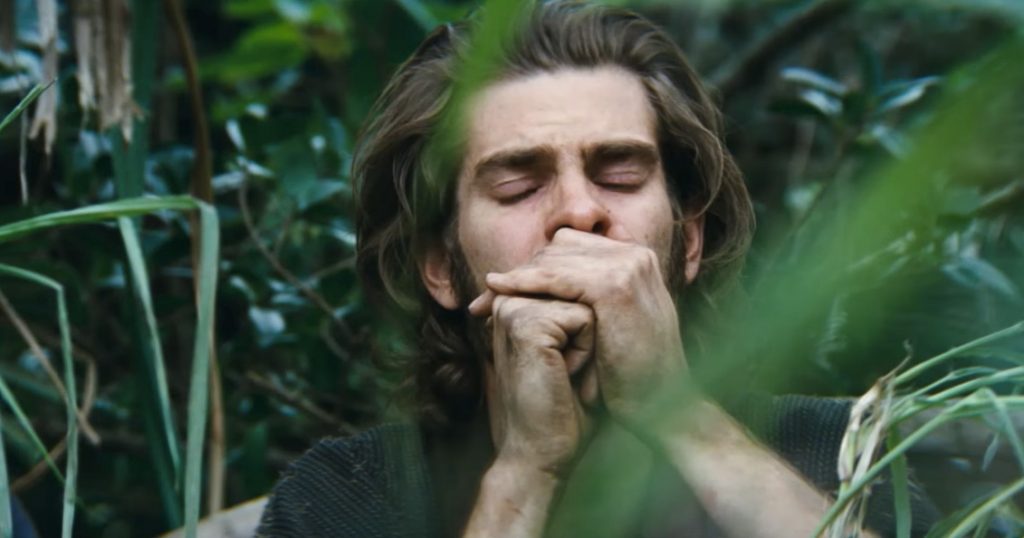

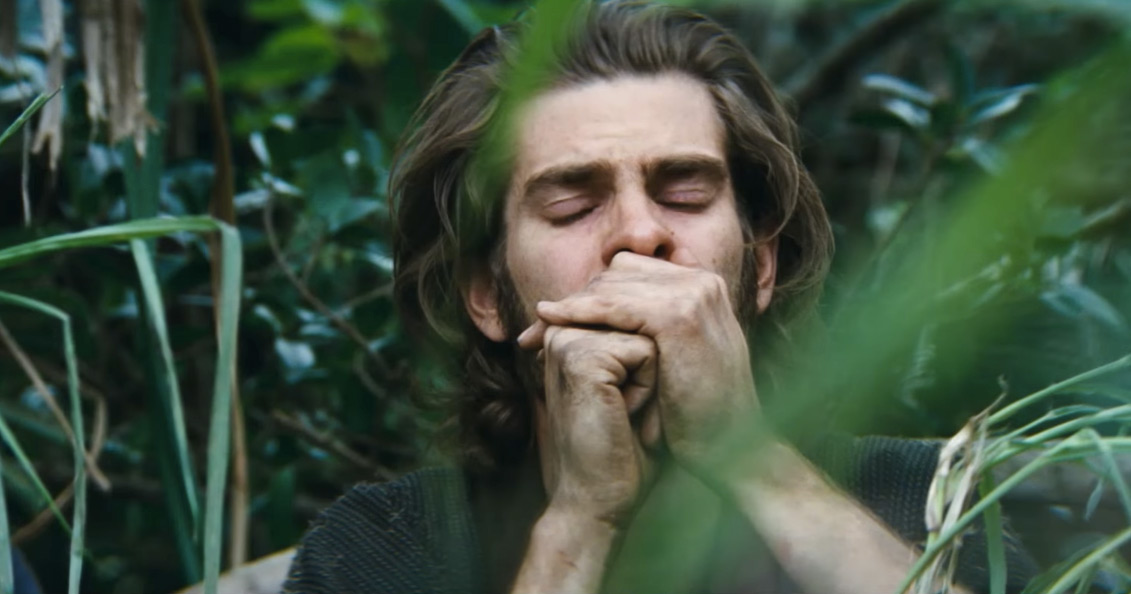

By the way, there's a new Martin Scorsese movie opening this week.

It's going to cause controversy in the church.

It's about what happens when believers speak truth to power. And it isn't pretty.

Brace yourself.

The test of a great Star Wars story

“Star Wars at Christmas?” “Put it back in May where it belongs.”

Some Star Wars fans had “a bad feeling about this” when The Force Awakens was scheduled for December 18, 2015. But complaints were forgotten when the movie opened to rave reviews.

Me, I’ve associated Star Wars with Christmas since I opened my first Star Wars toys on Christmas morning in 1977, while the original was still in theaters. Dozens of those original action figures—capes, lightsabers, blasters, and all—keep vigil on my bookshelves still today, almost forty years later. They kindle creativity in me. Star Wars only hinted at a cosmos of storytelling, and during those holiday vacations from homework, I dreamed up my own stories about that galaxy far, far away.

Apparently so did many others who grew up to be filmmakers. And now, with Disney’s promise that Star Wars movies will be an annual event, we can assume that droids and stormtroopers will become as common as reindeer and snowmen in December.

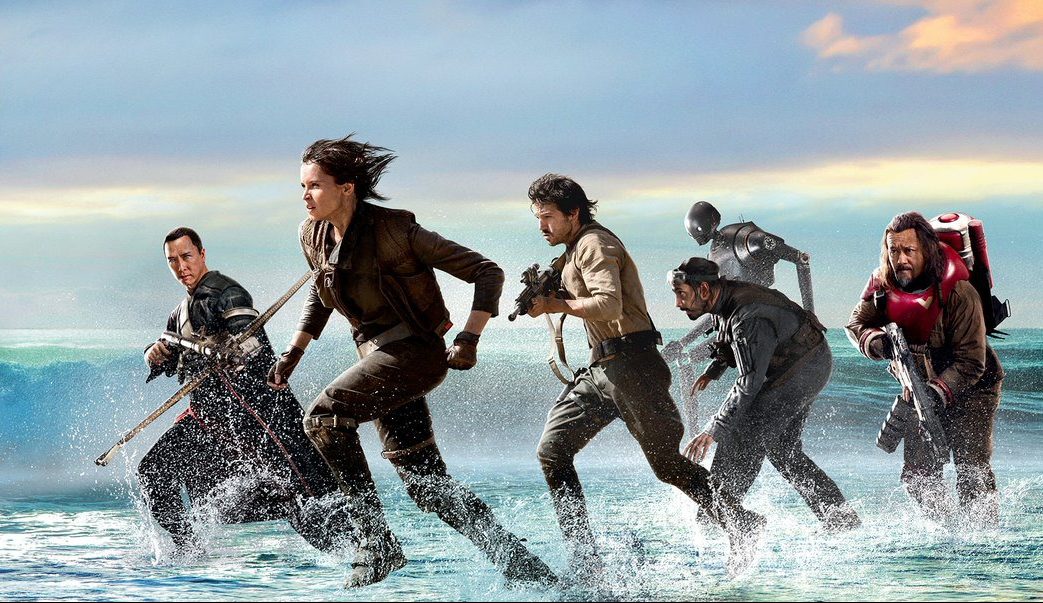

I haven’t heard protests about the Christmastime release of Rogue One: A Star Wars Story. (By the time you read this, I’ll have seen Gareth Edwards’ movie. And, let’s face it, so will many of you.) But I have heard other concerns: Will this episode—the first that doesn’t focus on Skywalkers—feel like the real thing? Or will it just feel like a money grab? Does Edwards understand what makes Star Wars unique and beloved?

Wait a minute: What does make Star Wars unique and beloved?

I think I know.

Read my reflections on the secrets of a great Star Wars story in my "Viewer Discussion Advised" column at Christianity Today.

Star Trek Beyon-and-on-and-on...

This is not a review. How can I review a movie if I didn't pay attention to it? And — I admit it — I did not... no, I could not pay attention to Star Trek Beyond.

It's such a letdown to discover that what the Star Trek franchise has always celebrated as "the final frontier" is so full of familiar, unsurprising, yawn-inducing storylines, worlds, and alien races.

It's also disappointing when special effects saturate films so completely that it has the effect of making everything seem unreal in the worst way. The crew of the Enterprise began this series with their basic character sketches based on the original series with a few surprises to spice up the mix. But they aren't growing and expanding. Here, they seem less like well-rounded characters and more like, well... characters described in 140-characters (that is to say, a Tweet).

Bored to Vulcan tears by all of the next-to-nothingness that was so acrobatically "filmed," I let my mind wander in some strange directions.

First I started imagining that the character of Jaylah had been on her way to star in Hellboy III — she certainly looks the part — when she crash-landed on... um... what was it called? Altoid-mint? But that idea made me sad. Because I really want to see Hellboy III.

Then, I started thinking about how much I wish the crew of the Enterprise could go back in time and save Anton Yelchin from that confoundingly terrible fatal accident that was just one of so many admirable-artist-deaths that darkened 2016.

Then, trying to cheer myself up, I decided that I should try Photoshopping Beyoncé-as-Uhura onto the Star Trek Beyond movie poster, with her standing in front of the letters O-N-D so it just says Star Trek Bey."

Then, trying to cheer myself up, I decided that I should try Photoshopping Beyoncé-as-Uhura onto the Star Trek Beyond movie poster, with her standing in front of the letters O-N-D so it just says Star Trek Bey."

And then I started daydreaming about a spinoff series, directed by Lemonade's Khalil Joseph, in which Bey-hura leaves all of these Enterprise idiots behind, and has kickass adventures of her own.

And at the 1-hour 40-minute mark of this thing I couldn't care any less than I did and I turned the movie off.

But Bey-hura, directed by Khalil Joseph — that stuff just kept unfolding and was one of the best films I've seen all year. In my mind.

Your new favorite Christmas movie

The world outside—it’s a dangerous place. Stick with Christian community. Where it’s safe.

I have received that message—sometimes blatant, sometimes merely implied—within so many Christian communities from childhood through adulthood. I’ve been instructed to read only Christian texts, attend only Christian schools, support only Christian charities, seek out Christian doctors, root for Christian football players, heed only Christian music, and beware of “secular” influences. Last week, in response to my Christianity Today review of Arrival, some readers warned me that my soul was in jeopardy for seeking wisdom in a Hollywood movie. Once, on a Sunday morning, I carried my heavy heart down to the beach for some solitude and prayer, and a pastor later scolded me for choosing to spend time in nature (“an unreliable source of God’s wisdom”) instead of within God’s house. Stay inside. Where it’s safe.

Brendan, the young ninth-century hero in the 2007 animated feature The Secret of Kells, has learned similar lessons. Monstrous marauders are on the march, seeking to slay anyone in their path. And the woods are full of pagan forces. Stay inside, says Brendan’s guardian. Be safe.

So begins this extraordinary animated film. The Secret of Kells might be a rewarding choice for your family during the Christmas season. It’s bursting with imagination, music, inspiring characters, and a celebration of a holy book that brings light into the darkness.

Here’s the story... in this week's edition of "Viewer Discussion Advised."

Manchester By the Sea (2016)

Twice now I've walked into a movie on a dry cold Seattle day and then emerged to become immediately enchanted by a change in the weather — to be specific, heavy snowfall. And both times, the discovery of the weather made me wish I'd spent the time wandering in a winter wonderland instead of sitting in the theater enduring more than two hours of Emotion Over Imagination.

The first time? Well, it was Titanic. If that blows my moviegoing credibility with you, I'm sorry... you might want to stop here. I admit it, I never really liked Titanic, even though it would go on to win a bunch of Oscars. It was so rigged for easy pathos, calibrated to affirm every adolescent impulse of the heart (that is, the hormones).

This time, the movie is, again, an Oscar front-runner — even though it lacks the big special effects, the sex appeal of a marquee-name "it"-girl and "it"-boy of the moment, and the crowd-pleasing "lovers in a dangerous time" hook.

This time, the movie is, again, an Oscar front-runner — even though it lacks the big special effects, the sex appeal of a marquee-name "it"-girl and "it"-boy of the moment, and the crowd-pleasing "lovers in a dangerous time" hook.

Manchester by the Sea is a much more grownup movie, about adults dealing with unfathomable tragedy and grief, and trying to figure out how to fulfill their responsibilities in the mess that the world makes of their lives. It comes from Kenneth Lonergan, a writer and director I greatly admire who has made two masterful films already — You Can Count On Me and Margaret. It arrives on waves of festival buzz. And I walked in, on a cold Seattle evening, eager to see what all the fuss was about.

Then I walked out into a snowstorm, and my film-induced funk was immediately erased by joy.

Maybe the snow sparked my imagination, but I couldn't help imagining how Manchester by the Sea might have become a better film than it is. Call it Moodslumper By the Sad.

For example, this would've been a lot more fun if Kyle Chandler had been playing an older version of Ben Affleck from Good Will Hunting and Casey were reprising his role from that film. He seems like a grownup version of that bone-headed kid who was capable of doing unspeakable things with his big brother's baseball glove (a scene I like to call "Mitt Wrongly").

But never mind: I don't mean to malign Casey Affleck. He's fine here as a human bruise, staggering around like someone has thrown a brick through the back of his head and now it weighs him down wherever he walks.

In fact, every fine actor in this ensemble delivers, including Chandler, Michelle Williams, and Lucas Hedges. But, for the first time with a Lonergan film, the heaviness weighing on everything stifles the movie. I just never feel enough fight in it: It's just Hard Life Guy Suffers Hard Things After What We Suspect Must Have Been Other Hard Things, And Then Oh My Yes He Really Really Did Suffer Other Hard Things, And Now I Can Only Guess That More Hard Things Are Coming. This lacks the enthralling literary-fiction complexity of Margaret and the compelling characterization and comedy of You Can Count On Me.

And Lonergan's own appearance — which remains a highlight of his first film — drop-kicks me out of the movie this time, as it all but confirms my suspicions that this is a movie in which an artist is Working Through Things. (Affleck looks, and even has some of the mannerisms, of a younger Lonergan... so it's weird to see Lonergan show up in person and yell at what I think must represent a younger version of himself. Cathartic for him, maybe... but not for us.)

Here's the thing: I just wrapped up teaching a college fiction-writing class, and I spent the quarter trying to pull the writers back from always going for broke with those BIG LOUD SCENES in which teenagers clash with the irresponsible, hard-drinking, hard-swearing, prone-to-drunken-violence adults who are raising them. (As far as I know, none of these students were writing from experience on this, so why the attraction to such ugly scenarios?) Maybe I'm a little burned out on shock-and-awe domestic eruptions like this; I admit that my lenses may be smudged.

But this film, constantly underlining its pathos with big sad classical music, never takes hold for me.

Okay, one scene grabbed me by the throat: It is, of course, the scene pictured on the poster, in which Michelle Williams gets her big moment. And it works because, well... Michelle Williams. But even that scene gets spoiled by a terrible, terrible edit in which her mouth is clearly not saying the words that we're hearing.

I recently revisited Tom McCarthy's The Station Agent — a comedy focused on three bruised and disheartened characters (four if you count Michelle Williams' adorable librarian) — and found it far more affecting than this. It allows its characters to play a wide range of notes, to have lives that take on poetically suggestive qualities, and to surprise us. Hard as their lives are, I always want to go back and revisit their stories to explore the imaginative play of the filmmaking. I think I'm one-and-done with Manchester.

Oh, well... I offer these hasty first impressions and ask you to receive them with heavy grains of snow-melting salt. A lot of my favorite film critics are really loving this, so I'm going to shut up now and let you decide for yourself whether to descend into this solemn, sullen story of sadness. Seriously — it may speak to you. I wish it had spoken to me. Instead, what I'll remember about the evening was how that shopping mall looked in the snow, and what a relief that was.

Arrival (2016)

Reader, I confess: I clicked “unfriend” last month. Several times.

Understand, I wasn’t ending friendships. I was respecting them — by refusing to let Facebook’s limitations do them further harm. It troubled me to see conversations we might have enjoyed in person go so horribly awry on social media. And anyway, our heated arguments attracted other angry voices, voices that overwhelmed our debate with snark, hostility, bullying, even hatred. I had to shut things down.

Nevertheless, I lose sleep at night over that “unfriending.” It feels like unforgiveness. It feels like despair.

So Arrival, the new science-fiction feature from director Denis Villeneuve, kicked me where I already hurt.

Read the complete post of my reflections on Denis Villenueve's film, Arrival, in my weekly column: Viewer Discussion Advised.

Doctor Strange (2016)

It’s easy to see why director Scott Derrickson’s adaptation for the Marvel movie super-franchise is such a success.

First: Marvel is a machine that makes blockbusters.

Second: Strange boasts standard-setting special effects. (Many say it’s inspired by Inception, but its wildest moments have equivalents in comics that predate Christopher Nolan.)

Second: Strange boasts standard-setting special effects. (Many say it’s inspired by Inception, but its wildest moments have equivalents in comics that predate Christopher Nolan.)

Third: Strange is played by one of this universe’s biggest stars—Sherlock’s Benedict Cumberbatch as the goatee-sporting, cloak-draped hero.

And fourth: It sticks to the basic Iron Man outline—rich egomaniacal genius is humbled, saved by science, and finds direction and purpose as a soldier in the cosmic fight against evil.

The more I think about it, the more these two hours of “escapism” seem relevant.

I wrote about this for Christianity Today in my column "Viewer Discussion Advised." Read the whole thing.

Are the Coen Brothers "filmmakers of faith"?

Last weekend, I accepted an invitation to St. Leo University near Tampa, Florida, to participate in a public discussion about — of all things — the movies of the Coen brothers.

Brent Short, the school’s director of library services, organized this seminar, and we were joined by Erica Rowell (author of The Brothers Grim: The Films of Ethan and Joel Coen) and Mark T. Conard (editor of The Philosophy of the Coen Brothers). For three hours we learned from one another and took questions from the audience.

It all seemed so Halloween-y. We talked about the Coens’ catalog — so genre-diverse, so full of tricks and treats. We talked about their crazy characters — H. I. McDonagh, Barton Fink, Jeffrey Lebowski, Marge Gunderson — all of whom deserve to become Halloween costumes.

But the film that haunted me all weekend was one that opened nine years ago this month. No Country for Old Men seems to resonate more meaningfully every time I see it.

In fact, that film contributes to my increasing sense that the Coen brothers deserve serious consideration as "filmmakers of faith."

To read my full article on this subject, check out the latest installment of my column "Viewer Discussion Advised" at Christianity Today.

How to Prepare for Scorsese's Silence...

A Man for All Seasons gives us Paul Scofield’s finest hour. As he sinks his teeth into Bolt’s delicious dialogue, I defy anyone to remain unmoved.

I recommend we prepare for Martin Scorsese’s adaptation of Shusaku Endo's Silence by revisiting this classic. Directed by Fred Zinnemann from a script by Robert Bolt (adapting his own stage play), A Man for All Seasons puts its Christian hero to a test that recalls the climax of Endo’s narrative.

More — a man as famous for his moral integrity as for his intellect — is ordered by King Henry VIII to sign an oath granting the king authority over the church. In this way, the king hopes to escape a heirless marriage to Queen Catherine and marry Anne Boleyn, maid of honour to Queen Catherine and sister of Henry’s former mistress. More’s refusal turns the world against him. England wants an heir.

But More is a man immune to the Devil’s seduction. His blessing won’t be bought. He won’t kiss up to a womanizing politician for his own advantage, and then feebly justify it by saying, “Hey, King David was a sinner too.”

Here's my review — a long with a 10-question post-viewing discussion guide — at Christianity Today.