Arcade Fire Now

Some off-the-cuff first impressions of Arcade Fire's new album: Everything Now.

•

For the band's fans, if you're interested, you can scroll down to the end to see my quick ranking of the band's records so far, according to my preference. That way you'll know whether you want to give my notes on the new album any attention at all.

Everything Now: I'm enjoying it.

The comedian Steven Wright once quipped "You can't have everything. Where would you put it?" He might as well be writing lyrics for Arcade Fire. That one-liner sums up what's troubling this band of burdened prophets this time around. In one sense, the Internet and trends in globalism have given many people unprecedented access to immeasurable resources. But what good is that if, once we have everything, we don't know what to do with it?

This becomes clear in the title song, which is so catchy that I'm likely to regret spending so much time with it. Everything Now finds Arcade Fire spinning in a blender of Bee Gees and Abba-style sounds — dancey, poppy, cheesy, heavy on horns and synths and beats. While the colors flash more cheerfully than they have on any previous Arcade Fire record, the lyrics still stagger under the weight of the world. This time, they're wringing their hands about a world that Radiohead prophesied almost 20 years ago: "In a while / Everything all of the time."

Every inch of sky's got a star

Every inch of skin's got a scar

I guess that you've got everything now

Every inch of space in your head

Is filled up with the things that you read

I guess you've got everything now

And every film that you've ever seen

Fills the spaces up in your dreams...

The world they're bemoaning this time has reached Peak Entertainment, Peak Distraction, Peak Information, Peak Access. And it doesn't take too much to see how the pace of this frenzy prevents anybody from finding fulfillment.

As the song comes into clearer focus, we find a family at the heart of it, and here the problem is hardly subtle:

Daddy, how come you're never around?

I miss you, like everything now

Mama, leave the food on the stove

Leave your car in the middle of the road

This happy family with everything now

We turn the speakers up till they break

'Cause every time you smile it's a fake!

Stop pretending,

You've got everything now.

Yes, the concern about family communication and intimacy still burns at the heart of Arcade Fire's convictions. In that sense, they maintain a sense of focus and identity: They are like an ambulance charging through town and broadcasting warnings about deadly preoccupations, hoping to save some lives. And it's hard to know whether these nostalgic dance tracks are meant as satire, or whether there's a certain self-consciousness at work, a desire to find some fun in the midst of this present apocalypse.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zC30BYR3CUk

They're also doubling down on their declarations that people are using and abusing religion out of self-interest. In "Signs of Life," another soundtrack to a frantic search for meaning, Butler sings, "Love is hard, sex is easy / God in Heaven, could you please me?" You have to feel sorry for the Almighty, who, through the Arcade Fire lenses, is being treated like a vending machine. People want fame or pleasure or, at the very least, a painless existence. (In "Creature Comfort": "... God, make me famous / If You can't, just make it painless...".) As a result, real love and real life remain out of reach; people keep running from puddle to puddle, too lazy to make a journey to the sea that would fulfill their longings.

It's like they're making a whole career out of variations on "I Still Haven't Found What I'm Looking For."

Picking up that thread, you can find your way through every song as another lament for a way the world has let the singer down... until "Good God Damn." That's the song where a suicidal soul begins to wonder (note the importance of punctuation): "Maybe there's a Good God, damn." At the suggestion of a benevolent deity, the singer has second thoughts about ending it all.

If these themes and lyrics strike you as feeling a bit like U2-lite, you're not alone. While this is Arcade Fire's lightest record musically, it's also their lightest lyrically. That's not to say they're dealing with frivolous themes (although sometimes I wish they would take themselves less seriously). It just means they're writing more directly, without the densely layered storytelling and poetry of previous work.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_Dx4IAD1NLo

So, when it comes to the songs and what they're about, I don't get the nasty backlash that seems to be prevailing among Arcade Fire fans. No, it's not a monumental achievement like Funeral or The Suburbs, but if they aimed that high on every endeavor, they'd burn out — or their fans would. Even U2 and Radiohead have their lighter, more playful, more experimental records.

What I find somewhat disappointing is that there aren't any standout tracks this time around — at least, not for this listener. I'm fond of "Signs of Life" and "We Don't Deserve Love" above all, but they don't land with the musical force of "Neighborhood" or "Windowsill" or "Wake Up" or "Keep the Car Running." (Nothing beyond the title track of Reflektor sticks with me like those songs, for that matter.)

And that is my ongoing concern about this band. Album by album, I'm not yet convinced that they are capable of great musicianship. They write more substantial lyrics than 99% of the bands currently playing. Their artistic ambitions are admirable. Their collective conscience is wide awake. Their moral compass is true. But it's hard to sustain, record by record, that sense of rock and roll authority if you don't have a vocalist, a guitarist, a bassist, a keyboardist, or a drummer who can step into the spotlight and show us that this music is more than just scaffolding for lyrics. Hold the music of Arcade Fire up the brilliance on display on any record by U2 or Radiohead, and it's clear that they haven't yet earned the right to swagger.

Still, they don't have to be U2 or Radiohead. They have their own distinct personality, and in a time when few bands show a capacity for, or even an interest in, taking the torch of Meaningful Rock into the next decade, I'm grateful that Arcade Fire are aiming high. I would rather listen to one of their albums many times, digging deeper as I go, then run in a panic from one pop release to the next in search of the Next Big Thing.

And these are grooves are, well, groovy, baby.

But let me close by reminding you: Back in January, Arcade Fire released a surprise sing: "I Give You Power," (featuring Mavis Staples). It was a knockout. I wish this album could have accommodated that track, but I'm not sure it would have fit in.

So here's an idea: How about bringing Mavis into the band? Why not make her the lead singer? That could be a band to rule the world.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NiblaBqJjIg

A few quick notes on how earlier Arcade Fire records have held up for me:

- Funeral. One of the all-time great sophomore records. The self-titled debut didn't prepare me for the focus, the storytelling, the poetry, the personal passion blazing through each track, and the go-for-broke power of this thing. Strong from beginning to end, and "Wake Up" is an anthem for the ages.

- The Suburbs. An enormous record in quality and quantity, one that fulfills the promise that this could become the biggest band in the world. Soaring ambition that captures timeless truth within an epic tracklist of songs about a very specific time and place.

- Neon Bible: Half a great record, half a very good one. U2-ish in its prophetic power. "Windowsill" and "Keep the Car Running" are instant classics.

- Reflektor. I admire, again, the double-album ambition and the concept-record coherence of the thing. But it sounds a bit like the band's been reading their most adoring reviews and taking themselves a bit too seriously. (I could be wrong; this is just an impression.) While it's always interesting, and the title song runs on lyrics that are as strong as anything they've done, the rest doesn't really sink in and stay with me like their best work. Perhaps it's because, as they're lacking any strong vocalists, I'm waiting for excellence in the musicianship that lives up to the ambition of the creative vision. It's just hard to escape the sense that their reach exceeds their grasp here. U2 has done huge, lasting, epic records, but they also routinely pump out irresistibly singable, focused, efficiently crafted songs, and the singular sounds produced by all four members of the band are worth close attention. Arcade Fire's feeling a bit like an overabundance of "pretty good."

- Arcade Fire. This debut presents us with a band that doesn't sound like anybody else before or since. It's a crowded, muddled sound, but take the time to sort through the layers: It has a certain replay value, and it rewards close attention as listeners begin finding their way through.

Being time and Stalker time

[There are some spoiler-ish comments regarding Andrei Tarkovsky's film Stalker ahead.]

•

I'm in the Zone.

It's one of the most mysterious places in all of cinema. Some say that wishes are granted there. Some say it can swallow human beings whole, and that is why so few return. For several decades, it has challenged travelers; there haven't been many easy roads for finding it, and when they get there they've found it in poor condition.

But, thanks to the cinematic saints at The Criterion Collection, Stalker, Andrei Tarkovsy's beloved science-fiction classic has been restored and released for movie lovers everywhere. Now we can travel with the Stalker himself, sneaking across heavily guarded borders and out into the wilderness in search where we learn, for better or worse, the secret of our deepest longings.

And this new edition is, as I'd heard, a revelation. Stalker feels like a whole new film. The chapters cast in sepia tones are so exquisitely deep that they make me reevaluate the quality of my TV screen. They make me want to freeze-frame the film every few moments just to appreciate the detail in these dilapidated rooms and eroding environments. And the full-color stretches give me the feeling I could step right through into "the Zone."

This is my second full viewing of the film. I remember it being "difficult" the first time. That didn't surprise me — it has a reputation of being an almost impenetrable and patience-testing experience. I can point to several sequences that have probably prompted moviegoers to give up, exasperated, complaining that "nothing happens."

But, to borrow a line from Cameron's The Abyss, "You have to look with better eyes than that."

There is a lot going on in Stalker; you just have to engage, to ask questions about what's happening. If a scene shows you some passengers on a train just watching the countryside pass by for several minutes, ask yourself about everything: the sound of the tracks rattling under the train, the strangely hypnotic quality of the rhythm, the reason why the camera is zooming so tightly on the characters' heads instead of bringing the scenery into sharp focus. I frequently pushed the "Pause" button this time, rewinding scenes so that I could pay attention to the specificity of the screenplay after finding myself distracted by the sound design and visual composition. It's rare, that sense that a movie is so spacious that you can focus on new things every time.

And this time, I'm finding the film to be strangely personal.

What happens in this film?

A brooding man known as a "Stalker" — in the sense that he "stalks" a mystery — wakes, rises, and ventures away from home for an excursion that turns out to be a kind of routine. There is some angst in the fact that his vocation draws him away from the woman he loves. He's called (by what, we wonder?) to take others into a strange, foreign territory in search of an epiphany: a revelation of meaning and purpose, and the fulfillment of their most fundamental longing. Stalker is the most self-serious version of a genie-in-a-bottle story I've ever encountered.

The travelers — the Stalker (Aleksandr Kaydanovskiy), the Writer (Anatoliy Solonitsyn), and the Professor (Nikolay Grinko) — wander. They get lost. They find a path. They draw near to the place where they hope they will learn something. Their surroundings may not seem that alien, that spectacular — but the degree to which they do seem so is driven by the quality of the travelers' attention.

I'll leave you to discover what becomes of the Writer and the Professor — what their longings are revealed to be, what their intentions in making the journey are really about, and what becomes of them. The Stalker, though, seems to return with a newfound sense of his own fundamental longing. This self-knowledge, this renewal of purpose, seems to make a kind of contentment possible that he lacks at the beginning of the journey. And it has everything to do with recalibrating his heart, with recommitting himself to his wife and to his daughter, a strange child who seems to be have been both cursed and blessed by her father's vocation.

And as I watch, I am startled to find that this film, which I remember as being such an arduous subject of study suddenly seems accessible, welcoming, fitting me like a heavy coat for a harsh world.

Where am I right now? I rose this morning, I gathered up what I need for a venture into "the wilderness" (books, devices, chargers, a water bottle). I headed out of the house, although I wasn't happy about leaving my wife's good company. I wandered. I got lost and wasted time (some of it on social media, some of it in traffic). I found a path into the novel I now want to write, and searched for that sense of discovery and joy that tells me I'm moving in a rewarding direction.

And when I came home, I was glad to be home, I was filled with a renewed sense of love and gratitude for my wife, and the fierce attention I gave the world around me and my work on the page was then refocused on her, and I saw her better than I might have seen her if I had merely stayed home in her company.

It seems like a routine for the forgetful, for the foolish. Why do I have to go and come back in order to really feel at home?

But I do this. I do it again and again. I don't know how to explain why, except to say that I often come home with renewed perspective, with renewed appreciation to the blessings I've been given, with renewed gratitude for the intimacy of my marriage and the possibility of rest. And in those excursions through other worlds — ferryboat rides across Puget Sound and back, hikes along beaches or through quiet forests, long drives through unfamiliar neighborhoods, or long stays at local coffee shops and pubs where my journey takes me into texts or music or conversations — I find the vocabulary I need to express what I am learning. I find materials for my art.

Author Gregory Wolfe, the publisher of Image (an extraordinary literary journal about art, faith, and mystery), writes about watching Stalker and seeing it as a film in the great Russian tradition of art about God's "holy fools." He affirms, reflecting on this film, that "to approach mystery is a long, arduous pilgrimage, best undertaken by those who know themselves to be beggars and fools."

Surely Tarkovsky was thinking of T.S. Eliot, who in "Little Gidding" of The Four Quartets writes, "I shall not cease from exploration, and the end of my explorings will be to arrive where I started and know it for the first time."

I love the double meaning of "end" in those lines: He will not cease from exploration, but the end — the purpose — is to apprehend the truth of what has been before him from the start..

•

Today, I find my way to a view of the water, and I open my old, bent, underlined copy of Madeleine L'Engle's Walking on Water: Reflections on Faith and Art.

L'Engle, a longtime mentor via her nonfiction, prompts me to think about "being time." L'Engle says that it's "something we all need for our spiritual health, and often we don't take enough of it."

It's been several years since I devoted myself to writing a new novel. I never meant for such a lapse to occur. But I know what caused it: I lost the support that, for so many years, had made "being time" possible. My day job had been a joyous, fulfilling experience of teamwork, creativity, camaraderie, and creative freedom. When the work load became unsustainable and people started getting sick, my own health and spirits suffered. I lost the strength to write.

Since then, I've been fighting for a life in which I can recommit to regular writing. I am so grateful to the Looking Closer Specialists — some readers of my work who recognize the time and resources that it costs me to keep this site alive. They continue to donate generously, in small and large amounts, and those contributions are helping me find my way back.

But the windows of time available to me are still small. Frustration frequently overcomes me, sinks me, makes me wonder if my creative life is over. I'm expecting myself to return to my best immediately: a level of high productivity, pages and pages of good writing. It isn't working.

And Madeleine L'Engle has reminded me why. I wrote Auralia's Colors and its sequels when I had time during my day to go stalking: to take long walks, to sit outside during my lunch hour, to spend substantial time in prayer, to pay attention to details and colors and natural forces.

I need my being time: the hours that are necessary for exploration, for contemplation, for stalking new ideas.

Writing is not about finding the time to put down on paper what you already have in your head. Well, a lot of people do that, but very little writing worth reading comes about that way. I go back again and again to an observation made by the poet Cecil Day-Lewis (and in other variations by many other writers besides):

First, I do not sit down at my desk to put into verse something that is already clear in my mind. If it were clear in my mind, I should have no incentive or need to write about it. We do not write in order to be understood; we write in order to understand.

The poet Scott Cairns offers a similar insight:

I think writers with actual intentions generally end up saying things they already thought they knew, and I’m not much interested in reducing my vocation as a poet to something like propagandist. I write poems to find things out, not to communicate some previously ossified conclusion.

And if I want to offer something that I haven't offered before, I have to take the time to explore new territory, to have days where I walk what turns out to be a dead end, to wander and suffer uncertainty about the value of what I discover. And I want to bring readers with me, so that they too have time to discover new glimpses of the truth.

"The truth," writes Emily Dickinson, "must dazzle gradually." That implies that I need time to find things that ring true. In the very same poem, she exhorts the writer to

Surely this poem was on Tarkovsky's mind when he wrote the Stalker's dialogue! The fearful, trembling travel guide tells his traveling companions, “The Zone demands respect. Otherwise, it will punish you. … We don’t go in a direct line. We’ll go roundabout. … Here, the straight path isn’t the shortest. The more indirect, the less risk there is.”

Artists, scientists, theologians, followers of Jesus — all truth-seekers need time for wandering. For stalking.

I recently asked Linford Detweiler of Over the Rhine — one of my favorite songwriters, and an artist whose faithfulness to his work is constantly inspiring — how his new projects are developing. He responded, "It's a time of hunting and gathering." I've heard this from him before. It means that he probably doesn't have any new songs he's ready to share with me. But he's exploring and bringing ideas home, ideas that may, in time, become a song worth sharing. In the past, those seasons have been short or long, but they have always led him to rewards worth sharing.

I told him to take his time.

•

So why am I finding it so difficult, now that I have some windows of time, to take the time that I need for stalking?

I'm beginning to believe, with some chagrin, that it has something to do with having achieved a dream, having succeeded for a time.

I grew up dreaming of writing an original fantasy series. I grew up dreaming of working as a movie critic. Both of those dreams came true for a time. And it did, for a while, wreck me. The exhilaration, the waves of relief and joy and gratitude that engulfed me — those have passed. And now I'm back at the beginning. I want to get that back. I'm not happy to find myself back in the fog, in a place where I'm intimidated by unknowns and possibilities. And, as I get older, I have an increasing sense that my time is running out. How do I choose what to do?

In Art and Fear, one of those little books that artists share with one another like precious secrets, David Bayles and Ted Orland write that this is a common experience for artists who have, at one time or another, finished something. "There's a painful irony to stories like that, to discovering how frequently and easily success transmutes into depression" (11).

I want to get back to that high of riding on a vision that is flourishing. Instead, I'm staring at a blank canvas. An array of embryonic ideas buzz about the room. I hold my net and feel paralyzed. I know that the path forward will involve stalking, swinging, missing, stalking, swinging, missing, and only occasionally catching anything worth keeping.

Bayles and Orland again:

The function of the overwhelming majority of your artwork is simply to teach you how to make the small fraction of your artwork that soars. One of the basic and difficult lessons every artist must learn is that even the failed pieces are essential. X-rays of famous paintings reveal that even master artists sometimes made basic mid-course corrections (or deleted really dumb mistakes) by overpainting the still-wet canvas. The point is that you learn how to make your work by making your work, and a great many of the pieces you make along the way will never stand out as finished art. The best you can do is make art you care about — and lots of it.

The rest is largely a matter of perseverance.

(Art and Fear, 5–6)

Is it any wonder that Tarkovsky spends so much time and attention on close-ups of the Stalker's head, the Writer's head, and the Professor's head? Aren't these domes of bone and brain the true location of "the Zone," the battlefields where seekers struggle to break free from their fears, their delusions, and their vanity in order to open themselves to revelation and the change that it can bring?

•

At the end of Stalker, the child is strange and quiet, but exercising mysterious powers.

I am not a parent. I'm not sure what this movie means to parents. But I know what it means for me, right now. My next story, whatever its future, whatever it might come to mean, is growing and changing and behaving in mysterious ways. That is, in part, because I'm doing what I'm supposed to do: I'm exploring and making something out of my exploration. And the story is already unsettling me, wanting to behave in unexpected ways.

That's just one of the paths of contemplation I wander as I watch the film this time. But it's the one that brings me much closer to the film this time, to a place where I can honestly say that the movie has become more than just an academic subject for this film student — it's become a companion, a teacher, a book of wisdom. A mirror.

So today, it's an hour in a secondhand bookstore. Okay, two secondhand bookstores. It's taking the time to read a daily scripture passage and an homily on my "Jesuit Prayer" app. It's taking an old, unfinished story and rewriting a chapter of it in the voice of a strange new storyteller.

It's a walk by the water, with a copy of Walking on Water in hand. It's a time of stalking, with Tarkovsky's Stalker still flickering behind my eyes.

Spider-Man: Homecoming (2017)

Yesterday, I wrote about why I keep buying tickets for Spider-Man movies even though I suffer from a near-perpetual case of superhero burnout.

That was all preface for this: a few words about Spider-Man: Homecoming.

•

I wasn't one for parades when I was a kid. As an introvert, I was not drawn to the crowds, to the noise, to the long day of sitting and watching. As the son of health-conscious, budget-conscious parents, I didn't want a day of seeing neon-colored cotton candy I couldn't eat, or souvenirs I couldn't have. I would rather have stayed home where I could be active in making stuff rather than just playing bystander.

But my parents inspired my interest in the Portland Rose Festival Parade by pointing out that Spider-Man would make an appearance. And so unfolded an episode of family history in which I reportedly felt betrayed by his failure to show up as scheduled. I sulked and complained until, at the very end of the parade, a tow truck played the part of caboose, hauling Spidey's broken float. And there he was, waving — somewhat sheepishly, I remember — to the viewers who were still paying attention. I think I felt embarrassed for him. He should have been the parade's main event. He should have driven the crowds mad, instead of, well, being driven.

That's how I've felt about several of the Spider-Man big-screen movies: They've rarely come anywhere close to the quality of the visions in my own imagination. They've seemed like huge, noisy, blustery, bombastic vehicles in which we who grew up reading dime-store comics and watching The Electric Company catch glimpses of the webslinger that we love.

The first feature-length Spider-Man, the opener of Sam Raimi's trilogy, found a winning Peter Parker in Tobey Maguire (even if he had already played a college student for Ang Lee five years earlier), a note-perfect J. Jonah Jameson in J.K. Simmons, and a perfectly heart-throbbish MJ in Kirsten Dunst.

But once the film bypassed the scenes of Parker's giddy realizations about his superpowers, and we moved into the his primary conflict with the Green Goblin (Willem Dafoe, giddily wicked), who bore a strange resemblance to the similarly split personality of Smeagol/Gollum in The Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers, things began to feel strained. And the CGI action only emphasized our hero's artificiality. He lacked weight. When the storylines finally converged, they delivered an anticlimactic resolution that, like Christopher Nolan's Batman Begins, called its hero "heroic" for refusing to kill the bad guy even as the audience was still treated to the gratifying sight of the villain's own deadly machinery turning and skewering him. Ugh.

Spider-Man 2 came to the rescue, becoming the movie I'd wanted to see since childhood. It tapped into my own wild imaginings of what the real Spidey would look like in action. Since its arrival, it's been the only movie that beats with a Spider-Man heart, drawing me back again and again.

When I talk to my film students about the art of great action scenes, I point to its thrilling elevated train sequence which combines a showdown with Doc Ock (Alfred Molina at the peak of his powers) with a desperate attempt to save a bunch of screaming passengers. In doing so — if you think I'm exaggerating, just watch the scene — he becomes, through his web-slinging frenzy an imitation of Christ, his sufferings spelling out Stations of the Cross (right down to the cruciform pose, the bloody wound in his side, a sort of "death scene" in which awestruck and heartbroken onlookers realize who he "really is" ... and then, a rising again.

Raimi's third film built on the success of the second, and I was delighted to find Raimi trying out some wildly audacious ideas — particularly a musical sequence that unleashed Parker's dark side. But it was burdened by typical sequel-itis, overstuffed with anemic storylines, forgettable villains, and, well... James Franco.

Director Marc Webb (it's still hard to believe, isn't it?) spun a reboot — one that was necessary, with Maguire now in his 30s — and his choices for Parker and MJ had their strong points: the athletic Andrew Garfield and wide-eyed Emma Stone had obvious (and true-to-life) chemistry. But they didn't look like high schoolers, and we couldn't escape a sense of "too soon," "too familiar," and "too automatic." Perhaps the pressure and the poor reviews were what hollowed out Garfield's features enough to win him the lead role in Scorsese's Silence.

By contrast, director Jon Watts' boldly inventive Spider-man: Homecoming feels fresh, inspired, and consistently surprising.

Surprise Number One? It's amazing how Watts — whose previous feature film, a tightly wound thriller called Cop Car, demonstrated how much he can do with very, very little — could leap with such confidence to such a large scale project. He makes it look even easier than Spider-Man bounding up the side of the Washington Monument.

Surprise Number Two? Homecoming was written by six screenwriters — usually a promise that the film will be uneven and probably awful. It isn't. The writing feels focused, refined, and alive with an eagerness to fulfill every Spider-Fan's dreams. It's really good.

I love how Homecoming's writers zoom in and find a story happening almost entirely within a small neighborhood, one likely overlooked by the Avengers as they bound around the globe. In fact, they find the story in the debris of the Avengers' recklessness, the very rubble that troubles me so much when superhero movies leave it unexamined and unswept, its cost uncalculated.

The origin story of this young Spidey's first big nemesis begins in the heart of somebody dealing with all of that debris — a clean-up crew and salvage foreman, Adrian Toomes (Michael Keaton), who finds treasure in the garbage, and who decides to do something with it when his experience of the Marvel Universe is minimized and dismissed. Keaton — insert Birdman jokes here — plays Toomes as a justifiably frustrated businessman who just wants to be treated fairly. When he's pushed too far, he's becomes a high-tech version of Michael Douglas in Falling Down, ready to unleash hell in order to get noticed.

That is good storytelling. Go team!

Surprise Number Three? The Michael Keaton I loved in the '80s — the one who brought such wickedly entertaining energy to Beetlejuice — is back! It was good to see him as a resilient real-news American hero in Spotlight, but I've missed the maniac I once loved in Tim Burton's early work. Keaton's fantastic here, evolving from temperamental to, well, absolutely mental.

Surprise Number Four? Tom Holland. He's not just another Peter Parker: He combines Maguire's knack for wide-eyed exasperation, Garfield's athleticism and grace, and characteristics that I suspect are inspired by the best boy-heroes of the 1980s (especially the stammering Michael J. Fox, the mischievous Matthew Broderick, and the earnest Sean Astin). Best of all, I can believe that Holland is in high school. Here's hoping that Holland, 20, can preserve that kid-like spark for a few more movies.

The Spider-Suit delivers Surprises Number Five, Six, and Seven: The suit's origins finally have a plausible explanation. (Nobody ever believed Parker could design such a thing himself.) And it turns out to come loaded with capacities that will catch even die-hard fans off guard. (The film’s substantial Civil War tie-in sequence is a laugh-out-loud surprise, one of the cleverest ideas in the film. You can feel the screenwriters’ excitement as they brainstormed their way to a breakthrough.)

Perhaps the biggest surprise is just how consistently Watts and Company go on surprising us, all the way to the end-credits "stinger" that earns what may be the biggest post-credits laugh ever achieved. The movie flows effortlessly, scene by scene, from Parker's practice-run crime fighting into his unexpected entanglement in high-stakes villainy, led by The Vulture. The movie prolongs their separate storylines, increasing our concern about how and when they will finally face one another in a showdown. The turn that brings them together, eye-to-eye, exposed, comes like a gut punch. It may smack of the "It's a Small World" Syndrome that weakens franchises, but it's still a zinger of a surprise.

Problems?

The movie has a disappointing dearth of Marisa Tomei. Captain America: Civil War teased us with the revelation that Tomei would play an Aunt May young enough to be a love interest for Tony Stark. Here, she doesn't have time to play much more than a threat to Parker's secrecy.

And speaking of Stark: Much has been written about the irony of Tony Stark — who has shown himself to be spectacularly immature, reckless, and irresponsible — becoming a mentor to Parker, trying to impress upon him his need to start small, be responsible, and grow into his role as a superhero. Yeah, that doesn't work for me either. While Spider-Man: Homecoming is supposed to establish the webslinger as a force to be reckoned with in the world of the Avengers, it also ends up accentuating just what poor role models those Dream Team players really are.

And that's an unexpected blessing, whether the filmmakers realize it or not. In a film that seems to be the film about Parker proving himself and earning his way onto the Avengers’ team, we end up questioning such ambitions — in fact, it might give thoughtful moviegoers pause when the next Avengers-focused epic comes around, causing us to ask if there might not be more cons to having Avengers around than pros.

But these flaws are small enough to make me think that Spider-Man has finally found some big-screen storytellers worthy of his promise. The only deeply disappointing move they make is probably one that all Marvel storytellers are contract-bound to deliver: a showdown sequence so saturated with CGI, so contrary to the laws of physics, so full of unnecessary sound and fury that it feels for a few moments like it belongs in another movie.

Why do Spidey and Vulture have to have a fight on an airplane? And I do mean on — not inside — an airplane? Why do they have to invest 10–15 minutes in a climactic showdown at all? Why not imagine something new? In both Wonder Woman and Spider-man: Homecoming, the movies’ strengths — their chemistry sets of likable personalities — make the finales feel like a letdown, sequences that, if I were watching them at home, I would fast-forward through.

Having said that, I felt a surge of relief as the struggle resolved. It's a surprising variation. I won't spoil it. Suffice it to say that you shouldn't let that triumphant music play out without realizing the nature of Peter Parker's triumph. What choices does he make here? How does that stand in stark contrast to so many other superhero movie conclusions — including those that focus on this character?

So, while I'd argue that Spider-man 2 still stands at the top of the list as the only manifestation that truly touches transcendence, giving Spidey a mythic quality that resonates with genuinely religious implications, Spider-man: Homecoming touches greatness too. Watts and Company give us a new Parker and a new Spider-man entirely sufficient to the task of course-correcting and extending the webslinger’s adventures on the big screen, emphasizing Spider-Man's inclination to save rather than win, to show mercy rather than superiority.

And the movie touches greatness in another way too, one that might be more timely and important.

As I write this, there are white supremacists marching on the campus of the University of Virginia in Charlottesville. They are raising their hands in Nazi salutes. And our President is refusing to oppose them — which means, of course, that he is breaking from a national tradition of opposing Nazism, which emboldens Nazis. In fact, he is equating those who oppose racism with hate movements. He is the President of White Supremacy.

So I'm not going to miss an opportunity to say how much I love the way Spider-Man: Homecoming tells the truth about the reality of multicultural high school communities without serving up any self-congratulatory gestures.

When we see Parker with his friends, he's fits into a wide-ranging spectrum of colors, cultures, and personalities. His best friend Ned, who dreams of being the "chair guy" who runs Spider-Man's control center, is played by Hawaiian actor Jacob Batalon. And Michelle, a tough-talking member of Parker's debate team, looks like she could become a gutsy superhero too, if she just had the right costume. But Parker's crushing on Liz (Laura Harrier) here — not a white, red-haired Mary Jane. And nobody comments on Liz's blackness, her braininess, or the fact that she's significantly taller than him.

Now that's progress, America. That turns a movie about a heroic Spider-Man into a heroic Spider-Man movie.

And if you told me that this Spider-Man was coming to town, I'd say he deserves a parade.

Why I keep getting stuck in Spider-Man's web

In my favorite wedding photo, my friends Melody and Geoff and their wedding party, all dressed up, stand on a playground near Salem, Oregon, looking formal and organized. Me? I'm in the air above them, limbs splayed like a dancer who doesn't know what he's doing. I've jumped from a swing on a swingset at the edge of the frame — a detail most people don't even notice when they first look at the image. I've had people look at it and say "How in God's name did you jump so high?" The photographer caught me at just the right moment after the launch.

And yes, I scuffed up the knees of my slacks when I landed.

It's one of my favorite photographs: It captures exactly the flamboyant enthusiasm I felt about seeing my friends take their own leap into the wild blue of marriage.

But it wasn't just the wedding that I was excited about. It was the swingset.

I used to love swings as a kid — the sense of freedom that came from testing the strength of those tethers, the strange sight of my feet kicking the clouds and the bright blue ceiling, the feats of courage that became possible when I could trust the anchor of the swing.

A few weeks ago, Anne and I visited an empty park just down the road from our house. Drawn to the swingset, I realized that I couldn't remember the last time I'd gripped those chains, dared myself to see how high I could go. I had forgotten how much I loved that dizzy rush.

And then I felt it again the next day, sitting up straight in a faux-leather recliner in the Regal Alderwood Stadium 7 Movie Theater watching Spider-Man: Homecoming.

I don't know why I've never wondered about this before: Why Spider-Man? Why was he the only superhero who captivated my imagination when I was a kid? Why did Superman fly right over my head without turning it? Why did Batman stay in the shadows, a figure of only mild curiosity? Spider-Man... I wanted the mask. The whole costume. The webslingers.

Perhaps it had something to do with spiders. Spiders scared me. The idea of being bitten by a poisonous spider was the stuff of nightmares. (Watching what happened when my younger brother was bitten by a brown recluse only amplified my phobias of those eight-legged invaders in my basement.) In The Auralia Thread, my series of fantasy novels, trees become diseased, and their branches break free and become vicious spider-like monsters.

Was Spidey my hero because he takes the powers that scare me and makes them his own?

Was it that Peter Parker is a kid? Superman is a grown man, after all. But wait — no, he isn't. He's an alien. His human identity is his alias. That sets him apart from my experience. Batman, he's wealthy... which is even more foreign to my experience than being an alien. But Spider-man... he blends into his high school class, and lived out my superhero fantasies as an afterschool special.

I asked my friends on Facebook: Do they agree that Spidey is more compelling than Superman? A flood of affirmatives followed, like these:

"Superman is boring. ... Spider-man struggles with teen stuff and he's got a really funny fast wit. Superman just punches."

"It's hard to make a literal god interesting in a fight. You know the whole time [Superman's] just holding back so he doesn't accidentally erase the planet. Spidey, however, has some stuff to work through and he's rather fragile in comparison."

"Spider-Man is more relatable to kids since he's kinda a kid himself with common, everyday problems, like doing well in school and getting a job. Whereas, Superman seems more distant, since he only has to worry about saving the planet and dating Lois Lane."

"It is easy to identify with a kid who gets picked on and isn't understood, but who secretly has great powers."

"I really think it's the outfit. Spider-Man just looks cooler to a kid. Most of the kiddos who are into Spider-Man have never seen one of the movies (mine and most of his friends). He saw a picture of Spider-Man with a bunch of other superheroes and he zeroed in on Spider-Man — when he was 3. There's just something about that mask, I think."

All of these replies are interesting. But I can't find, in any of them, an explanation for why I've always found this character to be so much more compelling than other superheroes. I think it's something else. The answer that resonated with my discovery came from 7-year-old Owen:

"I ask myself, 'Would I have fun being that person? Spider-Man? Yes. He can shoot webs and swing from them. Superman? He can just shoot laser beams and fly.'"

That's it. It's not just that he's a web-slinger. He swings.

You see, I've had dreams of flying, but I've never really done it. I wanted to fly when I was a kid, but the closest I could come to it was to climb onto the thick, bristly rope swing that hung from the towering birch in my backyard, kick off from the trunk, and swing in as wide a circle as I could manage. With the end of the rope firmly fixed to a high branch, I could swing my feet and soar up past the edge of the roof of my family's one-story house. I could stand on the rope's fat knot and spin as I swung. I could grip it tightly and raise both feet up into the air.

This was more fun than jumping out of trees and crashing to the ground. There was tension. There was arc. There was the sense of being free and yet held. In a word: suspense.

When I watch Spider-Man sling his webs and Tarzan-vine his way from building to building, I know what that feels like. I can feel his exhilaration. It's just like dreaming of having my own race car — it's a thrilling prospect because I know the sensation of driving.

What's more, there is something deeply human about the feeling of a swing. We want to fly, yes, but we also fear the consequences. A swing remains bound, anchored, trustworthy. It keeps us from sailing free of our moorings. It's the financial security that allows us to make a wild bet. It's the family that's there to catch you if your dreams fail and you fall.

And in the parlance of art, it is the firmness of real-world particularity that allows us to suspend our disbelief when we watch a movie, read a novel, or hear a song. We can lose ourselves in the wildness of The Lord of the Rings because we are anchored in the simplicity of the Hobbits. We can delight in wackiness of The Princess Bride because we always come back to the fact that it's a story read by an old man to his grandson. We love Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band because, for all of the psychedelic tangents, the songs are always drawn back to such simple and effortlessly lovely melodies. We watch CGI Transformers bound around the globe in Michael Bay action movies, but we don't believe what we're seeing unless they land with convincing weight; our faith in what we're shown depends upon the grip of gravity.

When it comes to superhero movies, I love those that keep me grounded with some measure of human experience. When I watch the Hellboy movies, for example, I'm delighted because Hellboy, despite his spectacular backstory, his fantastical powers, and his monstrous appearance, has such recognizably human traits. He snarls and curses and fails. He likes kittens and sings Barry Manilow songs. He's not a god duking it out with villains in the skies or smashing skyscrapers — at least, not very often. He captures my imagination with superhuman heroics precisely because there is a line connecting him to familiar human experience.

In that, Spider-Man's webslinging ways become a metaphor for the humanity at the heart of the stories — like Harry Potter who came after him, he's an insecure kid discovering his talents, and he can use them heroically so long as he doesn't lose his anchor... that connection to gravity that creates and controls what Annie Dillard calls "the tension of the audience's longing."

Spider-Man, well... he don't mean a thing if he ain't got that swing.

•

Tomorrow — Part Two: My review of Spider-man: Homecoming.

Maudie (2017)

"Our ideas of perfect are so imperfect..." - Sam Phillips, "Power World"

That line comes from a song inspired by Thomas Merton. Merton, a Trappist monk, keenly observed that love has almost nothing to do with how we live up to standards of law or righteousness. Love's treasures can be fully experienced by those condemned as inadequate, unworthy, even offensive. In truth, love may be even more alive within those who suffer much, those who feel gratitude for small blessings, those who are poor in spirit.

In view of that, I propose that you won't find a more striking image of true love on the big screen this year than the picture of Everett Lewis wheelbarrowing Maud — his small, arthritic housemaid — along a rugged road.

It's a story that we wouldn't believe if it were presented as fiction. Truth, as we know, is stranger — and Maudie, a tender and observant film written by Sherry White and directed by Aisling Walsh, is based on the unlikely rise to fame of Maud Lewis, a world-famous Christmas-card painter from Nova Scotia. Like Maud herself, the movie comes to life within daunting constraints. Like a towering array of sunflowers rooted in a plastic flowerpot, it transcends its basic mold — the familiar beats of a standard biopic — to offer vivid rewards.

I may not know enough about art to recognize the genius in Maud Lewis's folk-art scenes of flowers, birds, cats, and farm life. But in view of the strange circumstances from which her art emerged, I marvel at her story: how she endured the body-bending curse rheumatoid arthritis, the crimes and cruelty of a faithless family, the belligerence of the fishmonger named Everett who would hire and eventually marry her, and the way her poverty failed to protect her from the harshness of the elements.

As Maudie and her rough-as-barnacles husband, Sally Hawkins and Ethan Hawke are an inspired match onscreen. Hawkins manages to find a human being within the complexity of Maud's severe physical contortions and twitches. She's easy to care about because she's such an injured bird. But Hawkins asks for more than pity; she finds a quick wit and a flair for feistiness in Maud's half-murmured voice. Hawke, in what may be his bravest performance, is even better, taking inspiration, I suspect, from mid-1980s Tom Waits (see Down By Law) for his grunt-based dialect and sullen body language, to create an endearing beast who sees the beauty in Maud's mess of troubles.

How much of this represents the reality of Maud and Everett's story?

I'm almost afraid to investigate. I suspect that Walsh and White are taking a lot of artistic license here to give the film a satisfying arc, but these characters are now as real in my mind as people I've known. Though the conventional revelation of "real footage" at the end reveals that their extreme "actors workshop" exercises aren't extreme enough to approximate what Maudie and Everett really looked like, Hawkins and Hawke create a completely convincing relationship between social outcasts, finding moments of surprising humor between instances of Maud's stumbles and Everett's bursts of violent temper. (Whenever the film feels like it's falling into Hallmark-card sentimentality, Everett manages to bring us right back to ugly realism.)

And, like Maud herself, the movie isn't much for words. The screenplay is simplistic, obvious, and sometimes sentimental, with characters calling each other by name frequently, and even adding tags like "Sister" to make sure that we understand the relationships between characters early on. Maud's brother Charles is given only enough lines to establish himself as a money-grubbing villain, and her Aunt Ida looks like the Big Bad Wolf in a Grandmotherly disguise.

But the film's imagery, filmed by Guy Godfree, is exquisite throughout, finding unvarnished beauty in particularity and avoiding the museum-exhibit glow that could easily have romanticized the scene of Everett's ramshackle cabin. Meditative music by Cowboy Junkies' Michael Timmins (with a song by Lisa Hannigan) weaves warmth through the cold, hard details of the Lewises' life in a weatherbeaten cabin.

I'm a sucker for films about artistic awakenings, and the movie that this most reminds me of was my favorite film of 2009: Seraphine. But it also reminds me a great deal of Jeff Nichols's 2016 movie called Loving, with its focus on complicated intimate moments between seemingly simple people, its consistent preference for quiet moments over big dramatic flourishes, for dust and grit over shiny surfaces, for suggestion over statement, for the nuances of great actors in top form.

So, yeah — if you're tired of the beats of typical biopics, you're right in suspecting that this will seem disappointingly familiar at times. But I'd encourage you to go see it anyway. This is a case, in both the movie's artistry and its lead character, of something beautiful blazing to life within firmly fixed constraints.

It also shines as a substantial illustration that love can take root even in the context of failure, frailty, and poverty — in fact, those things just might be what make it possible.

If I were to write further about this film (and I hope to), I'd probably end up writing a sermon about Maudie as a movie about the Beatitudes:

Blessed are the poor in spirit,

for theirs is the kingdom of heaven.

Blessed are they who mourn,

for they shall be comforted.

Blessed are the meek,

for they shall inherit the earth.

Dunkirk (2017)

When I first saw Titanic, I thought, "I'd have enjoyed this so much more if the movie hadn't disrupted its powerful depiction of the sinking ship with an unremarkable melodrama about young lovers." The director's attention to the jaw-dropping details of how the ship came apart became a powerful parable about ambition corrupted by hubris, and an unsettling portrayal of how quickly the "civilized" turn barbaric when threatened.

Thanks to Christopher Nolan, I've finally seen an equivalent of the movie I'd imagined.

Wait, no — let me revise that claim. Dunkirk feels less like a ship-focused Titanic and more like what we would have seen if a ship-focused Titanic had been made, had been successful, and had inspired sequels that kept on heightening the number of simultaneous calamities. Dunkirk is like Titanic 5 — in which several Titanics hit the same iceberg at the same time... and then are attacked by enemy warplanes and warships, while passengers flee through the corridors of the sinking ships, pursued by German soldiers with rifles.

Sound like your kind of movie? If you're one of Nolan's tribe, then you've blown past anticipation already; you've seen the film two or three times already, and you're celebrating another victory for your hero. The barrage of rave reviews I've read have been as bone-rattling as any German air raid.

Nolan is a singular presence in this era of large-scale filmmaking. He's all about "shock-and-awe" spectacle, and yet, unlike Michael Bay and Peter Jackson, he's keen on jolting our senses and our intellects. His high-testosterone leads are as compelling as any giants of modern mythology, and yet they are not god-like superheroes — they are unconventionally complicated and conflicted, exposing the contradictions inherent in our Western idols.

Nevertheless, from the pell-mell pace of Memento, to the furious clash of egomaniacal magicians in The Prestige, through the heavy hardware and heavier moral quandaries of his Dark Knight trilogy, and into the far-reaching ambitions of the mind-bending Inception and cosmic Interstellar, Nolan has inspired what may be the most enthusiastically loyal fanbase at the movies: a host that often seem inclined toward a sort of hyper-masculine hostility if their hero's integrity is questioned. Read some of their raves, and you'll quickly recognize a dominant tone: that he is a master beyond criticism.

Dunkirk probably won't change that. The movie lives up to the hype. No doubt about it — the roar of Dunkirk will leave your ears ringing, your heart racing, and your fingernails bitten down to the quick.

And it does so by immersing audiences in a claustrophobic's nightmare.

You probably know the basics of the historical account. If you want the movie to surprise you about that, skip this paragraph: A cross-section of Allied forces – Brits, Belgians, Canadians, French — were herded like sheep by wolves until they were surrounded on the beaches of Dunkirk, France. There, they were easy targets for the German soldiers pressing in by land and by air: 400,000 men, trying to stay alive through wave after wave of deadly assaults, from May 26 through June 04, 1940, until civilians were mobilized to speed their boats across dangerous waters to evacuate the survivors.

I've read admiring praise for how Nolan foregoes traditional narrative, eschewing character backstories, and avoiding conventional character arcs. But that's not entirely true: He just trims his storylines down to the merest threads, acquainting us with the key characters with impressive efficiency. That way, our primary experience is a vicarious experience of disorientation, panic, and desperation. Things move too fast for us to fall into the comforting familiarity of formulaic war stories.

Nolan's not interested in creating heroes through Herculean feats of bravado. (I'll mention the cast later — this isn't a movie about star power. The lead actors are meant to blend in with the mad mass of desperate men — just everyday soldiers and civilians, not to rise up like UK stand-ins for John Wayne or Bruce Willis or Mel Gibson.) He's not interested in setting up villains for spectacular defeats. (In fact, we don't meet the enemy face-to-face here. It's easy to forget that they're Nazis; they might as well be the forces of natural disasters, sending tsunamis and tornadoes and volcanic eruptions down on a vulnerable village.) Nolan's interested, instead in exposing, at one extreme, the deafening madness of war that tends to send soldiers home in ruins, and, at the other, the awe-inspiring inner strength that can inspire men to empathize in the midst of conflict, and risk their lives for others — even strangers, even foreigners.

That's what makes Dunkirk such a fascinating document. It is more intense than anything Nolan's made before (which will please his thrill-seeking audiences), and yet it also does more to undermine, and then redefine, the idea of the Western hero than anything Nolan's made before (which may cause war-movie enthusiasts to feel like they didn't get quite what they paid for). Here, if the soldiers have guns, the guns seem like little more than baggage to carry. Here, if they launch a clever scheme, it's upset just as it gets started, or it falls apart in disagreements between desperate men.

Does that add up to this film being "Nolan's masterpiece," a claim I have heard from several accomplished critics?

That's a question that nobody can answer conclusively. Your position on that will have much to do with what you go into the cinemas hoping to find.

Me, I tend to admire Nolan's smaller, quieter, more contemplative films more than those that seem to equate exhausting the audience with serving them. (The film's blaring score is so relentlessly overbearing that I was tempted to hold up a sign in protest: "ZIMMER DOWN, HANS.") While Dunkirk is a historical recreation that, like Paul Greengrass's United 93, rattled my nerves as if trying to traumatize me, it didn't move me in more than a couple of fleeting moments. And in its relentless pile-up of crises — between which it constantly shifts to maximize prolonged suspense — it actually pushed me away into watchful detachment rather than drawing me into a suspension of disbelief.

One twist in particular, which comes fairly early, subjects a brave young soul to a life-threatening injury. It is meant to be alarming and ironic. Instead, it felt clumsy, abrupt, and entirely unconvincing.

I'm also sympathetic to what Sam Van Hallgren, producer of the stellar film podcast Filmspotting, jotted down in his notes at Letterboxd. He wrote that the film's scale seemed "at once huge and yet still too small. It never felt to me like there were 400,000 thousand men on that beach. I'd believe maybe 5,000?" He also found the film's climactic show of courage and honor strangely insufficient; surely the real rescue efforts must have required much more than we see here.

Whatever the case — I've already been informed that I am wrong, that I'm blind to the towering genius of Nolan's talent, that this is one of the greatest war films ever made. Every moviegoer is entitled to their opinions, of course. My responsibility is to describe what didn't work for me, but praise what is well done.

And there is much to praise here:

- the approximation of war's discombobulating chaos, in editing, in non-linear storytelling, in sound and fury;

- the recreation of a war without a hint of digital animation — the seamless and virtuosic lifelikeness;

- the conclusion, which refuses sentimentality, and recalls the deep ironies and sadness of Spielberg's Empire of the Sun.

And, of course, the performances, precisely for their unglamorousness — for the way big stars consent to sink into characters that would not stand out as superhuman. Tom Hardy is something of an exception, in that he's given the film's most conventionally heroic turn, and yet he doesn't strike iconic poses or speak quotable lines: he's just a severe and attentive gaze, the rest of him cloaked in pilot's leather. It's a combination of his performance in Locke, where he spent the whole movie behind the wheel of a car, and his turn as Bane in The Dark Knight Rises, where he had a mask on the whole time; he accomplishes so much with so little.

Also impressive, Mark Rylance, somehow finding the secret to making tender-heartedness look like strength; Cillian Murphy, as a shell-shocked survivor doomed to live in nightmares; Kenneth Branagh, in an uncharacteristically understated turn; and Fionn Whitehead, who gets the most screen time, and who plays the perfect ball bearing, steered and thrown and trapped and controlled by forces beyond a soldier's control.

By the way — if you ever hear anybody say that soldiers who get captured or retreat are "losers," make them sit and watch Dunkirk ten times without a break. This is a film that comes not from men's idealistic imaginations about war, but about the grievous burden of having experienced what war really is. I can't help but think of C.S. Lewis, J.R.R. Tolkien, and Watership Down's Richard Adams, whose fantasy epics are distinguished by the sense of mournfulness that keeps battle-scenes from ever feeling fun, from ever looking like an attractive way to live. Dunkirk tells the truth with an appropriate burden of grief.

I might also note that for me, a man who has been blessed with freedom from any call to war, the emotional experience of this film is the best approximation I know for what it feels like to love my country in 2017, and to wake up every morning to find wealthy superpowers recklessly tearing down the fundamental engines of democracy and human decency. I know that's not what Nolan intended, but as I watch soldiers running back and forth, ducking and dodging each new horror, I sat there saying "Yes. This is what it feels like."

Ultimately, though, the film's greatest truth comes in glimpses of cooperation between individuals and nations, decisions to suffer and serve together, decisions to fulfill the responsibilities of one's position with integrity, decisions to show brotherly and neighborly love.

So, no — I don't call Dunkirk a favorite, much less a masterpiece. It's high on noise, chaos, and anxiety, and low on the visual poetry that is, for this moviegoer anyway, cinema's highest art. Nevertheless, it provides a necessary corrective to the dangerous machismo of most war films, celebrating heroes as those whose concerns have more to do with cooperation than individual glory, with the common good over superhero distinction. I'm glad it's out there. Especially now.

A Ghost Story (2017)

Have you ever become a ghost, haunting someone — or some place — that you loved?

I have. Once upon a time, I loved my office. It seemed too good to be true.

For several years, I worked in a space I had filled with artwork that inspired me. Even better, my standing desk was set against a floor-to-ceiling window, so I enjoyed a panoramic view of a garden alive with Japanese maples and magnolia trees. Behind it loomed the university's clock tower. On a typical day, rivers of students rushed through the garden, hurrying to and from their classes. Between those parades, the garden rested, while woodpeckers, hummingbirds, squirrels, crows, and the occasional raccoon paid visits. In the blue dome of sky above, bald eagles circled.

The beauty of that place was good medicine for my head, heart, and imagination. And it influenced my work — I wrote better, edited better, thought better while I was there. One of the school's teachers, a world-renowned brain scientist, once explained to me that this combination of practicality, personality, and perspective was an ideal circumstance for mental acuity and innovation. I had no trouble believing him.

And then, influenced by workplace trends, the supervisors decided to remodel everything. I was relocated to a corner, under harsh fluorescent lights, facing a wall. I still don't understand why.

Bob Dylan once said that "Nostalgia is death." If we strive to preserve or to restore something that has passed, we can do harm to ourselves and, worse, to others. I admit, I was probably not an ideal coworker in those last years of my work there. If I'd been wiser, I would have left that job, handing it over to those whose interests and priorities had no room for me. Instead, I stayed. I struggling to adapt. To be loyal. To survive until things improved. Things did not improve. And my appeals for some help fell on deaf ears. My creativity suffered and my spirits slumped. I struggled to avoid resentment. With chagrin, wondered if I would devolve into that grumbling oaf who gets assigned to the basement in the movie Office Space.

If this leads you to guess what I was like when my high school girlfriend broke up with me, well, you'd probably guess right.

When I love something, or somebody, I am not likely to let go easily. I am, you might say, easily haunted. Memories of good things that have passed, they torment me. And if I don't find a way to move on, I become ghost-like myself, hovering over the ruins of what has crumbled.

*

I thought about that office while I watched the celebrated new film by director David Lowery, in which a man becomes so attached to his house for the memories it contains that he cannot let go of it. He can't let go when his wife wants to move. He can't even let go after death.

A Ghost Story is a moody and, yes, haunting film. In earlier films like 2013's Ain't Them Bodies Saints, and in last year's remake of Disney's Pete's Dragon, Lowery established himself as an artist more inclined to crafting quiet, intimate, suggestive scenarios than big, explosive entertainment. This new movie is so hushed and meditative that it makes his previous work seem loud and busy.

To play out this heavy-hearted drama, Lowery has brought back his Ain't Them Bodies Saints stars: Casey Affleck and Rooney Mara. They play another troubled couple, but this time we never learn their names. (End credits call them only "C" and "M.") To viewers familiar with the highs and lows of long-term relationships, their highs and lows probably seem ordinary. He seems to be a recording artist, recording his longings in airy falsetto, while she... well, if the movie tells us what she does, I missed it. Their most memorable adventure happens one night when strange noises jolt them out of bed and send them sneaking about to find the source.

Horror movie fans will have ideas about where this might be going. They'll be wrong.

Eventually, M feels ready to move on, but C feels a strange connection to this address — a connection the film doesn't entirely explain. And his opportunities to enlighten us are few. He dies suddenly, and for most of the film he is a silent ghost — manifesting as a Halloween caricature. (Shall we call him Hole-y Sheet? No? Okay.)

C-Ghost spends days, and eventually years, brooding in the rooms he loved, resenting and troubling others who try to make memories of their own there, and watching the tides of change advance upon his yard.

C-Ghost's inability to speak to the living has much to do with the film's most powerful strengths and its most frustrating weaknesses. It invites us into his long silences, to keep vigil during stillnesses during which "action" amounts to subtly shifting light which glimmers in sharp contrast to the apparent permanence of C-Ghost's bitter resolve.

If, after one viewing, I was asked to say what I think A Ghost Story is about, I would suggest that many of the hints in this almost-silent, spacious film point to ideas about the corrupting nature of nostalgia, sentimentality, and fixating on — rather than grieving and surrendering — a lost treasure. C-Ghost strives and strives — as I did in my doomed quest to turn back the clock and recover the ideal working conditions that I had known — to keep the "glory days" from slipping away, a world that had fit him so perfectly.

It becomes fairly obvious that the problem with ghosts is an inability to let go, to accept time and loss, to open themselves to what the forces of change might bring. C-Ghost's journey will involve a slow education in the early history of this property that he so fiercely desires. He'll learn hard lessons in cruelty, injustice, and losses far more troubling than his own. The "real Treasure" is — as you can probably guess — not a house, not a scrap of land... but love, a fragile and delicate thing that happens in the Now, in tender exchanges, in openness and generosity and surrender.

That's my best guess at what this film is about — at least for now.

*

While the film's silences demonstrate Lowery's willingness to challenge his audience, those silences also became somewhat frustrating for me. Many of my favorite films are similarly meditative, but quiet and confusion are two different things. You may have a different experience, but A Ghost Story took me on a long and circuitous journey that tried my patience.

While I appreciated the moody rooms, the delicate prisms and reflections on the walls, the affecting lead performance by Rooney Mara, and the gutsy gimmick of the Halloween costume haunting a hospital, a house, and a history, I found myself increasingly confused and confounded with the movie's startling turns in the second half. It feels like it would have worked better as a short film, sticking to the modest strengths of its first half, before the tangents in the second half that seem to be straining to Say Important Things. I never quite tuned in to what its second half wanted me to discern. And in the culminating scene, when a big secret is revealed, it doesn't help me at all.

I'll try to avoid specifics, but the conclusion reminds me of the famous mystery at the end of Sofia Coppola's Lost in Translation — the famous "What does he whisper in her ear?" moment — but blown up to a feature-length mystery. In Coppola's film, the whole rest of the movie provides hints and suggestions about what that private exchange might mean. Here, most of the movie remains ambiguous, creating a constant implied refrain: "What do you think?" And that leaves me grasping for a credible interpretation of its conclusion.

So, if a college sophomore tells me in class that <i>A Ghost Story</i> is great because "It can mean whatever you want it to mean" ... I will cringe and admit that, "Yes, its ambiguities are so huge that it really is a big-screen Rorschach test."

But 'Openness to Any Interpretation' is not a quality of Great Art."

I can throw some popcorn onto a tabletop and call it art because, well, it's "open to interpretation." That doesn't mean I'm right. Real art, on the other hand, invites us to discover meaning by studying relationships between elements within a frame, and the more observant an interpretation, the more connections we can make between the details we've been given to support that interpretation. Blade Runner, back in 1981, confounded audiences; as years passed and viewers began connecting dots and speculating about the Why of its refusal to follow a formula, its meaningfulness was revealed. Interpretations gain credibility over time, as more and more "readings" reinforce it, revealing the integrity of the work, the sense that nothing is extraneous or unnecessary.

That doesn't mean "weaker" interpretations are useless. Our interpretations tend to reveal things about us as well as the work itself. We bring our own particular questions, experiences, and interests to the table, and that will influence our relationship with a work of art. So, what we experience watching a movie like A Ghost Story might be both meaningful even if it is more about us than the work itself. I have no doubt that many viewers will embrace this film as meaningful in the way that their assumptions about the movie fill up its spaces. And that's fine.

But does the movie itself support those interpretations? Is there enough evidence within it that others will come to those same conclusions, and we'll begin to see more clearly some particular truths in the midst of these mysteries?

I go to art for the opportunity to encounter a truth too big for words, one that lives in mystery and metaphor, one that can be shared. Like climbers who approach a mountain from different directions, we might see it differently, but there is still a growing sense that we are climbing the same mountain, that there is a "there" there. It may be that a subsequent viewing will help me find something more substantial here. But if I were to hear Lowery, say, "No, your student's right — the movie doesn't have a truth of its own; it's whatever you want it to be" ... well, thank you, but I want my money back.

So when Josh Larsen and Adam Kempenaar of the Filmspotting podcast talk about the ending of this film, and one finds it particularly hopeful and the other doesn't, all I can do is shrug and say, "Who can say?" If there is evidence in the film to incline us one way or another, I sure didn't see it.

*

Still, I don't want to give the impression that I'm dismissing the film. I'm just saying that, as someone deeply familiar with grief and loss, I was surprised to find myself unaffected by a film so widely celebrated as a masterpiece.

I admire how A Ghost Story favors restraint over the sound and fury and busy-ness that qualifies as entertainment for most American moviegoers. I don't share the opinion of the the moviegoer who, sitting next to me, huffed and puffed impatiently through the first 20 minutes and, during the already famous Pie-Eating Scene, wheezed, "Okay, okay, we get the point. This is ridiculous." This is not a movie about "getting the point.") Here's a film characterized by humility and restraint in the presence of unanswerable questions.

I just think that, after my first viewing, the film may value the power of ambiguity a little too much. It drapes beautiful images of shadows and light over questions that seem important. I'm just not at all sure what those questions really are. Whatever mystery I'm supposed to meet there just stares blankly back at me, out of reach.

*

Note: I read with amazement that the movie's much-discussed Pie-Eating Scene represents the first time that actress Rooney Mara ever tasted pie in her life. Wow. For me, that is a more particular and interesting revelation than anything in the movie itself.

Also: Speaking of Mara... after making a strong impression on me in Carol, and doing such great work this year in A Ghost Story and Terrence Malick's Song to Song, she is making an extraordinary career of playing characters whose speak through emotions (those eyes!) rather than words. Now I want to see her in a Coen brothers movie so I can see how she handles actual dialogue.

Confessions to a counselor about Wonder Woman

Someone breaks your heart. Or you lose your job and you need guidance into a better future. You survive a violent childhood and suffer from PTSD. Or you're grieving the loss of a loved one. You know where to go. You seek out a therapist, a counselor, a spiritual director.

But where do you go to sort out your feelings about this new Disney live-action Beauty and the Beast?

If you're like me, you seek out the company of wise and discerning counselors like Tara Owens (a moviegoer, a spiritual director, and the author of Embracing the Body) and Marcus Robinson (a songwriter and an associate pastor).

A few weeks ago, I found myself in their good company, in Owens's Colorado Springs office, sinking into a comfortable chair as if I'd come seeking counsel. She closed her door and made sure that everybody knew: We were "IN SESSION" — "DO NOT DISTURB." We were safe. We could share secrets, confess our moviegoing sins, and say what we really thought about summertime movies.

Let me explain: The Anselm Society — a community formed by a network of Colorado churches who are cultivating "a unique vision for the future of the Christian faith" — has a podcast called "Believe to See." I was invited to join show hosts Robinson and Owens for a frank conversation about this summer's big screen options. The result? We poured out our passion for, and our frustrations with, films like Wonder Woman, Baby Driver, Get Out, A Quiet Passion, The Fits, Timbuktu, and others. We laughed. A lot. We threw down challenges for moviegoers. We confessed our frustrations about "Christian movies."

And we wrestled with a profound question: How shall we pronounce the name "Gal Gadot"?

I'm not just saying this: My time with Marcus and Tara was one of the best hours I've ever spent talking about movies. I was a grand time full of laughs, epiphanies, and insights. I'm grateful that they invited me into such a lively conversation.

And now you can listen to the whole thing:

Life in the Dark

I opened the new film issue of Image today, which was edited by cinephile Gareth Higgins and Rectify writer/director Scott Teems, and I was immediately caught up in a complicated conflict regarding one of my favorite filmmakers: Robert Bresson.

In the essay called "Necessary Images," Teems writes,

For years I’ve wrestled with this seemingly straightforward declaration from the notebook of revered French film director Robert Bresson (a small book, but a bounty of inspiration). I’ve wanted to believe in his “necessary images” and therefore aspire to create them. To use simple, unadorned imagery to distill the filmmaking process to its fundamental elements: juxtaposition and montage, sound and music. To tell a story with pictures. To eliminate beauty for beauty’s sake. And to resist the urge to manufacture emotion, lest I betray my lack of faith in the form.

The realization of this principle, in theory at least, would compel the audience to project themselves onto the screen, to bridge the gap between the expressed and the intended. It would necessarily result in the creation of films in which—to paraphrase Flannery O’Connor — “two plus two equals more than four.” That is to say, it would result in art.

If simplicity is the ultimate sophistication, then Bresson was one of our most sophisticated filmmakers. The quiet confidence with which he allowed his stories to unfold never ceases to astonish me. Like his Japanese contemporary Yasujirô Ozu, Bresson was fearless in his formalism, and the best of his work conveys a deep respect for his audience and a profound trust in the power of pure cinema.

And yet.

That's a loaded "And yet."

Teems goes on to say that while he admires Bresson, he's "rarely" moved by Bresson's films.

That might be a good argument against Bresson's mantra — but Teems doesn't really mean to discount Bresson.

And I'm glad of that. Because I have found Bresson's rule puzzling for a very simple reason: I think his images are uniquely and hauntingly beautiful.

Take Au hasard Balthazar, for example – one of my favorite films. By eschewing gaudy adornment, Bresson crafts images that focus my attention on the mysterious glory of the human form, the expressiveness of a human hand, or even the quiet opacity and poetic suggestiveness of a suffering farm animal.

https://vimeo.com/98484833

And you'll find that Teems, too, ends up acknowledging the power of Bresson's carefully composed images, along with the achievements of many other directors — including several of my favorites, like Krzysztof Kieslowski and Abbas Kiarostami.

I recommend you read the whole editorial, and then pick up the whole film issue of Image. It's necessary.

And beautiful.

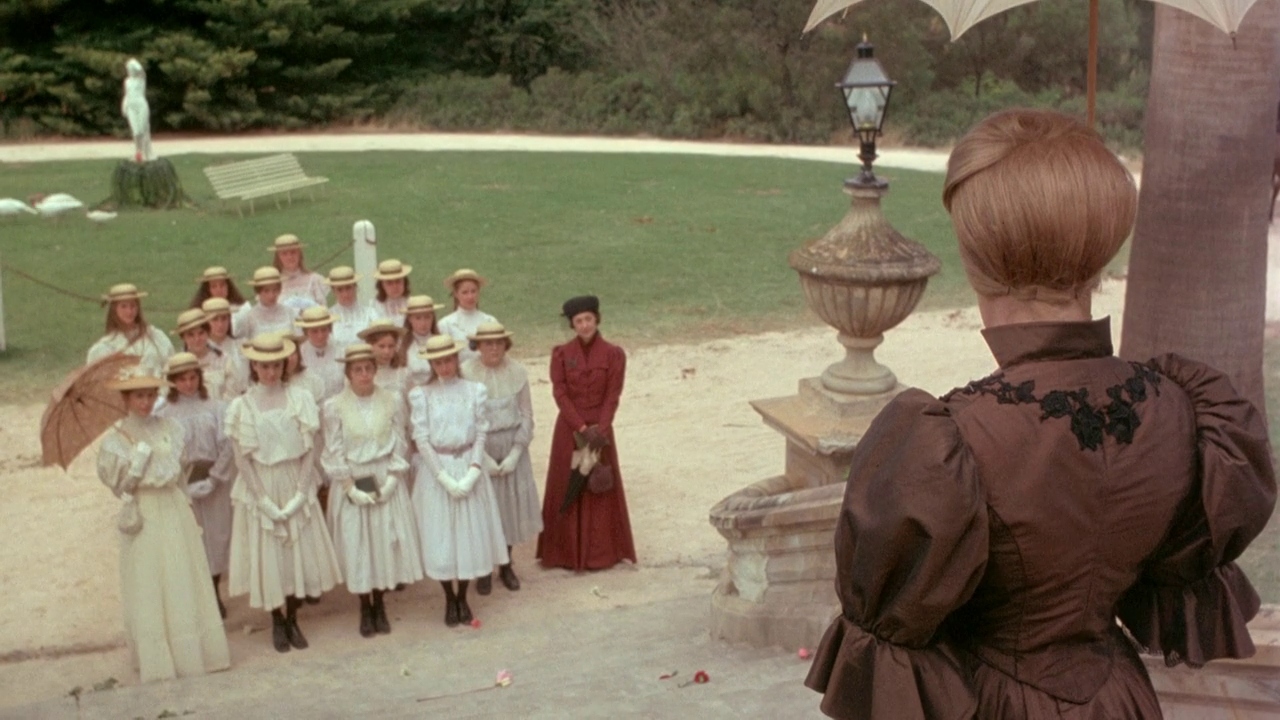

The Beguiled (2017)

Peter Weir's Picnic at Hanging Rock — the 1975 film that set the tonal template for Sofia Coppola's films — is more powerfully present here than in any of her previous work, even The Virgin Suicides.