Film Forum: mother! and the haters

You've probably heard that Darren Aronofsky's latest film, mother!, is polarizing and controversial.

You've probably heard that it scored an "F" on Cinemascore.

You may have even heard Christian media voices condemning at as blasphemous.

Cinemascores, of course, have nothing at all to do with the artistry, beauty, mystery, and truth at work within movies. They have everything to do with audiences experiencing something and reacting: "That's not what I wanted to see. You didn't give me what I like."

Sometimes, moviegoers react in protest because what they saw failed to intrigue, challenge, or inspire them. Sometimes they react merely because they were uncomfortable, and most people don't go to the movies to become uncomfortable.

This is happening with mother!, especially among Christian viewers who are jumping to conclusions that the movie is nothing more than a hateful attack on the church. Feeling that the movie comes from a hostile imagination, feeling offended, and feeling deprived of that familiar, reassuring sense of being entertained, they protest.

In doing so, they may be expressing how much the church means to them. I'm glad that the church means something to them.

Unfortunately, they're also demonstrating that they're not listening. They're not listening to other perspectives, to the artist, or — most importantly — to the movie itself.

Before I share some of those other perspectives, let me give my defense of this film a little more context. (If you're willing to read that, I'm grateful: It demonstrates a willingness to listen, and I'm not exactly accustomed to that.)

A couple of years ago, I watched a presentation by a popular Christian filmmaker. He presented a manifesto for Christians in the cinematic arts. He wanted to start a movement. He began by describing “the biggest problem we face today.” This "biggest problem" wasn’t poverty. It wasn’t the threat of nuclear holocaust or the threat of mass casualties to increasing natural disasters. It wasn't our own sinful nature. "The biggest problem we face today," he claimed with solemn conviction, is that young people are leaving evangelical churches.

He then presumed to present a primary cause of this mass exodus: there is better "entertainment" available to them elsewhere. Why would they stay in church when their desire to be entertained can be so easily satisfied elsewhere? The lack of high-quality Christian entertainment, he said, leads young people to immerse themselves in entertainment that exposes them to dangerous worldviews and offensive content. So, he declared, we must seize the resources available to us and create entertainment that will give them a safe and exciting alternative.

“I want three things when I consume entertainment properly,” he said. The screen lit up with his priorities in ALL CAPS.

First: “SEE WORLD VIEW REPRESENTED.”

According to the speaker, Christian moviegoers want movies that show them the world the way they already see it. They don't want to be troubled by a worldview any different from their own. This, he implied, should be our priority.

This strikes me as complicated. I know a lot of Christians. And their worldviews different dramatically.

Second: “DON’T WANT TO BE OFFENDED.”

Christians who “consume” movies, says the speaker, want to avoid anything that would run contrary to their moral sensibilities, upset them, or lead them into temptation. “I don’t want to cover my eyes or ears, or to cover my children’s eyes or ears,” he said.

This, also, seems complicated to me. I know a lot of Christians. They are "offended" by different things. And what does "offended" mean, anyway? I recently came across these words in a comment on David Dark's Facebook page:

"'Offended' isn't a feeling. It's a word we use when we don't want to name our feelings."

When we say we are "offended," what do we really mean? Does profanity offend you? Profanity can be spoken in hate and recklessness. It can also express anger or hurt or injustice. It can also express that someone doesn't have the language to express their frustration. Are we really listening? Does Jesus teach us to flinch and avoid people who are upset, or angry, or uneducated?

Third: “WANT TO BE ENTERTAINED.”

The speaker says that Christians who go to the movies want to be entertained. He lists this among Christians' top three priorities in their engagement with media.

We want to be entertained as opposed to… what? Being bored?

That seems extremely subjective. I know a lot of people — Christian or otherwise — who are entertained by very different kinds of work.

If I’m not misreading this passionate culture-warrior, I suspect that he means that Christians want something comfortably familiar and agreeable — something we can enjoy without trouble.

But here's the thing...

Art's purpose is not to show us our own way of thinking. Art invites us to pay attention to our neighbors, especially those who are different than us, so that we can experience new things and, through patient observation, grow to understand and appreciate them, perhaps even embrace and agree with them.

Art, then, becomes an essential way in which I can follow Jesus Christ’s admonition to “love your neighbors.” How can we love our neighbors if we don’t develop a quality of attention that enables us to listen to, contemplate, and engage with perspectives and experiences different from our own?

I'm a Christian.

When I go to the movies, I want to encounter a wide variety of worldviews.

I am not afraid of things that make me uncomfortable. When I feel offended, that often reveals my own weakness and fear and desire to withdraw from an encounter with a person who has urgent needs.

I want more than entertainment. I want to listen, to think, to learn, and to grow, even if that means experiencing works of imagination that reflect convictions different than my own.

And when I engage with art, I find that my faith grows stronger, my capacity for loving my neighbors increases, my appetite for experience and education grows, and I have greater courage to go venture beyond the faith-dulling comforts of home.

•

So...

When I watched mother!, I saw how easy it would be to read it as a narrow, simplistic, anti-Christian allegory.

But I also saw all kinds of things going on that didn't align with that reading, and that suggested other more complicated readings.

What I perceived most of all was a deep sense of compassion and empathy for the female figure in the film, for how her creativity was neglected, for how her pending motherhood was devalued and exploited, for how her hard work to make the world a better place was disrespected and destroyed.

I felt the "groaning" of creation, the cry of injustice from women, from nature, from the beautiful world that was spoken into being by a loving God but that is afflicted and tortured by definitions of God that are primarily concerned with all things male.

While I'm still thinking through and discussing what I experienced, I found three things were crystal clear:

- I was not necessarily seeing my own worldview on the screen. I was hearing from a neighbor, based on his own experiences, and I was receiving some challenging ideas and questions. So long as I am concerned about beauty and truth, this can only lead to growth and wisdom.

- I was uncomfortable, and — yes — at times I felt offended. And yet, as I thought through what I had seen and engaged with other perspectives, I realized that those feelings of "offense" were more about me jumping to conclusions than they were about what the movie was actually about.

- And this was not about entertainment. This was about art... which is better than mere entertainment. This was a call to a meal, not a treat; a challenge, not mere reassurance. This was a call for conversation, not applause.

As a Christian who grew disillusioned with conservative evangelical churches in America, I can tell you that I didn't leave because I wasn't "entertained." I moved on because of the self-centered, insular nature of those churches I attended. I moved on because of an unwillingness to listen to (and thus love) our neighbors. I moved on because of a fundamental misunderstanding of the power and purpose of art.

I'll share what I wrote down, in a sort of fever of inspiration, after seeing the movie.

But first, let me share some other perspectives from some of the moviegoers whose patient and observant interpretations have been blessed me with insight over many years:

Michael Sicinski (at Letterboxd):

On the one hand, it's about the eternal struggle to create, with a blocked poet (Javier Bardem) sacrificing his wife and muse (Jennifer Lawrence) in order to bring forth genius into sick and hungry world.

...

But on the other hand, mother! is a feminist examination of the denigration of the domestic sphere. Lawrence is a literal home-maker for Bardem, working to restore his destroyed family house and keeping him in food and drink while he attempts to write. Once he is able to produce, she is regarded as extraneous, the home front a menial distraction.

The central portion of mother!, which is marvelous on both an intellectual and a technical level, emphasizes the Lawrence character's needs and desires as trivial, the material demands of life as a nagging necessity for the vaunted poet. This is made evident when the older couple (Ed Harris and Michelle Pfeiffer) show up, a kind of faux-benevolent home invasion that soon becomes one opportunity after another to humiliate "Her." Eventually, a swarming group of the Poet's acolytes takes over the house, treating Lawrence like a gauche interloper.

Like the suitors in Penelope's home in "The Odyssey," their sense of entitlement is both comical and shocking. At every turn, they seem to demand that "She" justify her very existence, and Lawrence's beleagured character is cast as a shrew just for attempting to maintain basic order. Aronofsky asks us to consider whether artistic creation really demands the orgiastic anarchy and unmitigated violence into Lawrence and Bardem's home devolves. And is Lawrence a "nag" for wanting her own work respected?

I find mother!'s critique of gender and creativity compelling because it speaks loudly and indicts the very worst parts of me. When I write, I frequently have to pause because my wife or daughter calls me away, to tend to some domestic matter, or to share some interesting idea with me. Sometimes it's frustrating. I would prefer uninterrupted solitude. But those flashes of frustration are momentary, because I recognize that I have made, and continue to make, the decision to live with other people, people I love more than I love myself or my work.

Evan Cogswell (at Catholic Cinephile):

The question at the heart of mother!, Darren Aronofsky’s latest bizarre fever dream heavily infused with Biblical allegories, is what happens when an artist abuses that power.

...

Mother herself is another allegorical character, with touches of the Virgin Mary, Hestia, and Aphrodite, but she is primarily drawn from Gaia, or mother nature herself. Whatever combination of metaphors mother is meant to represent, Lawrence draws on them all effortlessly, creating a sympathetic character who never seems gullible or foolish for blindly going along with her husband or pouring all her energies into refurbishing their mysterious house, another process of creation and a sort of vocation that no one, including her creative genius husband, appreciates.

Aronofsky has said that his original idea for mother! was to convey a feeling of dread and helplessness as one watches their home destroyed, an allegory of mother earth’s helplessness in the face of environmental destruction That is an easy interpretation to see, especially considering the selfless giving of mother to her husband and the increasingly disturbing string of guests he parades through their home because they love his work. At the same time, if the invasion of the home is a parallel to humans destroying the earth, it also functions as an example of a self-centered artist allowing his wife’s handiwork to be abused and destroyed because he wants all fame and glory for himself, not much different from an abusive artist trying to usurp glory from God or misuse His creation.

Alissa Wilkinson (at Vox), in a review that, she pointed out on Twitter, got a nod from Aronofsky himself:

... [T]here’s so much pulsing beneath this film that it’s hard to grab onto just one theme as what it “means.” It’s full-on apocalyptic fiction, and like all stories of apocalypse, it’s intended to draw back the veil on reality and show us what’s really beneath. On one level, Mother! is also about what partners of artists have to deal with (that Aronofsky and Lawrence met while shooting this film and started dating is … confusing). And, like Noah, it’s about humans’ proclivity to wreck anything good with their own unfettered desires and selfishness. It evokes The Fountain in its view of history; it evokes Black Swan in its uncanny ability to get into the relationship between women’s physical pain and the soul.

And in case it’s not clear, this movie gets wild. If its gleeful cracking apart of traditional theologies doesn’t get you (there’s a lot of folk Catholic imagery here, complete with an Ash Wednesday-like mud smearing on the foreheads of the faithful), its bonkers scenes of chaos probably will. Mother! is a movie designed to provoke fury, ecstasy, madness, and catharsis, and more than a little awe.

But if he’s directing with abandon, Aronofsky is also entirely in control. Nothing happens in Mother! he doesn’t intend. The apocalypse works just as expected. Bits of his earlier creations are present everywhere, but this seems like it could be in its perfected state. The world he’s created feels practiced and familiar and yet entirely new. But by the end, he burns it all down. Time to start again.

Do these reviews give you enough reason to pause and question the hastily hostile reactions and the narrow interpretations elsewhere in Christian media?

Here's what I wrote as soon as I got home from the movie:

Note 1: I really didn't expect to be writing what I'm writing now. I expected to roll my eyes, thankful to have merely survived another blast of Aronofsky intensity.

Note 2: Your experience may be very different than mine. The woman who sat behind my friends and me stood up as soon as the credits began to roll and said "Disgusting!"

-

First impressions:

If Lars Von Trier so loved the world that he gave a rip about how women feel, then whosoever attended his movies would not feel revulsion, but would find themselves moved and rewarded.

Okay, that was a lame play on a famous verse—but bear with me. If the director of Melancholia and Dancer in the Darkdidn't take such obvious pleasure in tormenting women (both the actresses and the characters) in his films, but rather sought to respect and honor them through sculpting expressions of empathy, we might end up with something very like Darren Aronfsky's new film: mother!.

mother!—I'm lowercasing it because I'm told it's the right thing to do—is Von Trier-esque in many ways except the most fundamental: it is a film of deep compassion. Compassion for women. For what is often understood as the "feminine" forces, the womb-like qualities, at work in cosmos. For women whose lives are creative works of art. For Mary, the mother of God. For the mothers and wives who devote their lives to the impossible challenge of making a family and a home. For women whose creative expressions are neglected compared to those of men.

I've avoided reading reviews because I didn't want other people's interpretations in my head. And I am glad I did, because I'm playing with so many interpretations right now. And I think that's the way it's supposed to be. This isn't a film you'll "figure out." It's a film that offers you call kinds of readings worth considering, and it can substantially reward them. It's not the monumental work of ego and pretentiousness that I've heard some people say it is.

And I did not go into this as an Aronofsky fanboy. Of his many films, The Fountain is the only one that has stuck with me. I admire his mind, and have enjoyed my interviews with him. But his films have often felt like too much style and not enough substance—like wild exhibitions of his power that ultimately point back to him instead of to some deeply meaningful takeaway.

I went into this expecting the usual Aronofsky bombast: sound and fury signifying, well, not nothing... but not enough to justify the hurricane force of his style.

The style is significant. The cinematography feels improvised, but the more you think about it the more you see how purposefully and carefully edited it is. It shows us just what we need to see, and there's enough going on that I'm sure I'll go on discovering more in subsequent viewings. Yes, it makes us feel trapped and desperate, but not in a way that makes me resent the director; rather, I feel I'm being asked to consider what the world feels like to Lawrence's character (who just might be The World). It's not about making the audience squirm, but approximating the experience of its central character—a character of mythic proportions.

And the sound design: Oh, my. This film's force has as much to do with its meticulously crafted sound design as anything I've seen in a long time.

But here, perhaps for the first time, I feel that there is enough substance to justify Aronofsky's style. (Yes, I know—style can be substance. What I mean is that every choice contributes to the richness of the whole, complicating the network of metaphors in interesting ways, rather than just being another heaping scoop of sensory stimulation.

Comparing this to music: This isn't a symphony playing a shallow rock song or just showing off how loud it can be. This is a symphony playing a work that has a reason to be, a work woven from meaningful questions, and lamenting wrongs of a cosmic nature.

In locating this centrifugal force of a scorned woman's rage, Aronofsky unleashes what we are already seeing happen in nature around us: the world striking back at mankind's version of "God" and saying "You can't rightfully worship a creator god who devalues the natural world of his own creation, who perpetuates or excuses its exploitation, or who oppresses the feminine."

This film is not able to be boiled down to a Rosemary's Baby remake, or a critique of Christianity, or a critique of religion in general, or an allegory of the artist and his muse (although all of those things have some merit). It is open to a thousand interpretations, not because it's meaningless, but because it is making connections between realities in the manner of an ambitious poem. It is seeing correlations between people, archetypes, and phenomena. A good poem about the artist and his muse is a poem about God and his creation... is a poem about a marriage... is a poem about inequality... etc., etc., etc.

Most Aronofsky films have made me think too much about Aronofsky. This one does too. But this time, I feel like he isn't so much thinking of drawing attention to himself as he is interested in drawing attention to a cosmic tragedy: the exploitation of women, the exploitation of nature, and the blindness of men in overlooking and devaluing what the feminine force of the cosmos gives and gives and gives.

Having said that, I would be able to enjoy this film so much more if I didn't know about his past relationship with another leading lady and the child that came of it. I don't want to think about those things as I watch, but I can't help it. Yes, he offers a flamboyantly self-effacing portrait of the artist (and anyone with a god complex) as an egomaniacal monster; so there may be some attempt here at self-examination and making amends. But still... I'm not convinced that this stands as an expression of confession or repentance. It feels more an artist who has killed for inspiration and is now singing about the grief (as the song goes)*. [My friend Pete Peterson got to this lyrical reference before I did.]

And the fact that Aronofsky and this leading lady are now a new item makes the whole thing feel rather icky. I suspect that we will someday look back at this film and be as preoccupied with stories of the director's relationship with actresses as we are when we talk about Hitchcock films... and that's not a good thing. We should focus on the work itself and its possible interpretations, undistracted by the artist and his personal life. But Aronofsky is making that almost impossible.

Films I thought about while watching and then in the post-viewing conversation:

Melancholia (Von Trier)

The Passion of Joan of Arc (Dreyer)

What Lies Beneath (Zemeckis)

Vertigo (Hitchcock)

The Fountain (Aronofsky)

The Tree of Life (Malick)

Black Swan (Aronofsky)

I'm in no way saying that mother! is derivative. I think this film will stand the test of time and earn its place in dialogue with those films as a strong piece of work, superior to anything Aronofsky has yet made. He's been a director who has intrigued me in the past, but I feel he's made a significant step forward here. Now he really has my attention.

Em-Bark on a new Wes Anderson adventure

Good dog, bad dog... Wes Anderson has rounded up a pack of 'em.

In the past, Anderson has talked about his love for Richard Adams's Watership Down, and that was evident in the way he borrowed elements of that story's climax for The Fantastic Mr. Fox. Will this be influenced by Adams's The Plague Dogs? (That's one heart-sickeningly vision of the world, and certainly not a story for children.)

Get ready. FOX Searchlight will "let the dogs out" in March 2018. If there's any justice, Over the Rhine will compose the soundtrack. (Not likely, but wouldn't that be perfect?)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dt__kig8PVU&feature=youtu.be

Innocence Mission: past, present, future

I awoke to find a new interview in Cordella Magazine with The Innocence Mission's Karen Peris, in which she talks about the band's history, recent work, and future plans (including plans for new albums!)

She also says this, which made me stop and think:

As a reader of poems, I have most often been touched by poems that are visual, that get at something true, but leave a lot of space for the reader to imagine and connect. So that is always my goal for what I write, in spite of how unattainable it may seem.

Recently, I've been looking at a lot of photography of undersea life. Anne has a magnificent book of vivid imagery of creatures no sci-fi movie could have imagined, and they are sparking new storytelling ideas for me. Somehow it doesn't surprise me that Peris's evocative lyrics are inspired by image-focused poetry. Pictures speak more powerfully than messages.

She then goes on to talk about her favorite picture books:

Laura Carlin and Beatrice Alemagna are two illustrators I love. One daydream I have is to make a children's book, so I work on that sometimes.

That has me asking a question I don't think I've ever asked at Looking Closer: What are your favorite children's books when it comes to illustrations? Share some recommendations in the Comments, and I'll come back later this week with some recommendations of my own.

In the meantime, here's Karen singing a song that conjures all kinds of images from my childhood of reading and dreaming...

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q2s9LAtKPDg

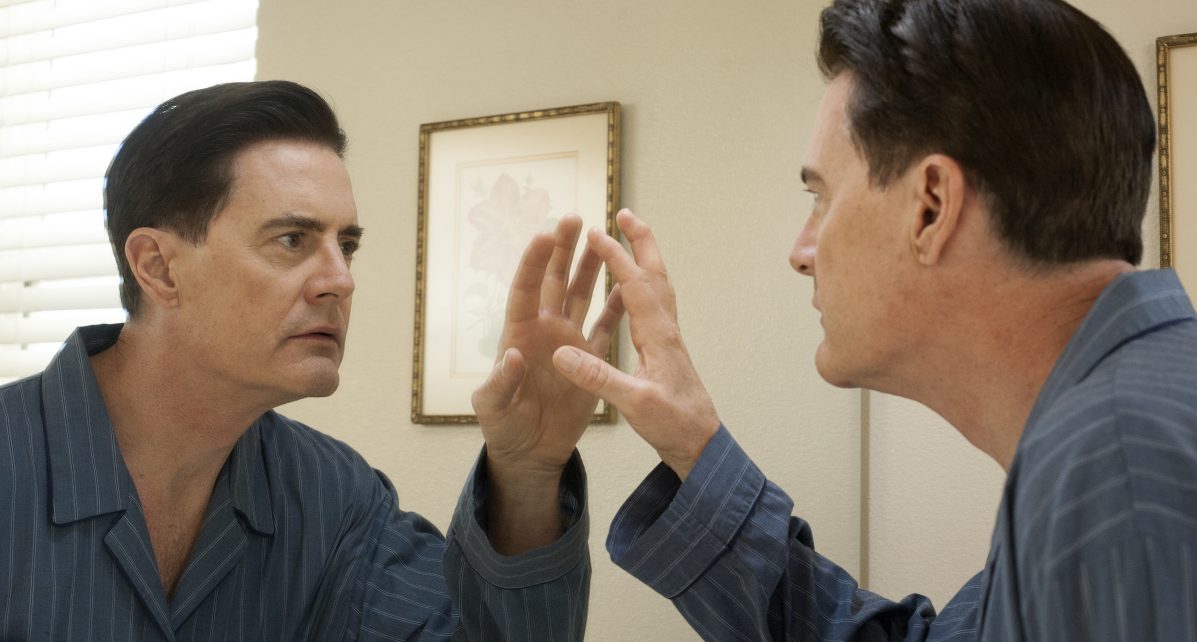

Agent Cooper goes to pieces

For 25 years, I've outlined essays about David Lynch's cult-classic television series Twin Peaks. Now that there's a new 18-episode series on Showtime that serves up a spectacular sequel—Twin Peaks: The Return—that desire has been even stronger. I don't think I've ever written one... until now.

Thanks to Adam Bryan Marshall and the hard-working team at Christianity Today who challenged me to condense some thoughts on this extravagantly creative and innovative series into one readable piece. I really need a book-length project to scratch the surface of my thoughts about David Lynch's art.

But here's a start:

Twin Peaks: The Return Gets Cosmic Conflict Disturbingly Right

Welcome to a new & improved Looking Closer!

Looking Closer?

It's looking better!

Here's a quick note about the improvements you're seeing on this website.

New Bruce Cockburn, Lizz Wright, Lone Bellow

Three new records that I've been eagerly awaiting are getting "first listens" this week. But these free previews will disappear when the albums are officially released, so act quickly if you want to hear them before you buy them.

Listen to Bruce Cockburn's new album Bone on Bone at No Depression.

Listen to Grace, the new album by Lizz Wright, produced by the great Joe Henry, at NPR First Listen.

Listen to Walk Into the Storm, the new record by The Lone Bellow, at NPR First Listen.

Essay of the year?

Ta-Nehisi Coates' latest essay "Donald Trump is the First White President" was posted today. It's drawn from his upcoming book We Were Eight Years in Power.

And I think it's the most significant examination I've read about what has led Americans to declare war on the nation's own historical and foundational ideals.

It's powerfully crafted piece of writing as well. I intend to share this essay with my students this fall in order to challenge them to move through the emotions that they feel while reading an intense political argument, and to examine the way in which the writer has organized his thoughts and backed up his claims. I think it will stir up important conversations.

But like any explosive device, Coates's essay — an explosive designed to blast truth into a culture where truth is being suppressed and distorted — needs to be handled with great care. Misinterpreted, or placed in the wrong hands, it could set off angry and destructive shouting matches. Proceed with caution and discernment.

Me? I feel like I've just read the opinion of a world-class doctor after he examines the advance of an extremely complicated disease. His argument rings true to me. But this is the kind of harrowing revelation that drives me to prayer, because I don't see a solution outside of a nationwide revival inspired by the Holy Spirit.

I recommend that you read the whole thing. Share it. Discuss it. The first step in striving to recover from a deadly cancer is learning the truth about what the disease really is, and naming it, out loud, no matter how much it hurts.

A new U2 experience begins

Here's Bono, speaking to The (flourishing) New York Times about their upcoming album Songs of Experience:

What’s the difference between ‘Innocence’ and “Experience’?” he said. “The core of ‘Innocence’ to me is a lyric from our second album, which says, ‘I can’t change the world, but I can change the world in me.’ The core of ‘Experience’ is — and this is cheeky! — ‘I can change the world, but I can’t change the world in me.’ And so you realize that the biggest obstacle in the way is yourself. There are things to rail against, and there are things that deserve your rage, and you must plot and conspire to overthrow them. But the most wily and fearsome of your enemies is going to turn out to be yourself. And that’s experience.

And the Edge says,

On this record, we went, ‘Is it going to be played by people in a bar in 25 years?’

What do you think of their new song "The Blackout"? Will you be singing along in a bar in 25 years?

How about this new one? Here's "You're the Best Thing About Me":

https://youtu.be/PbGSiJ9iat8

Perhaps you are one of those who is frequently "irked" by U2. You're welcome to your opinion. But I'd encourage you to read this personal reflection by David Dark, published recently in America Magazine:

Is it possible to seek total global pop domination for decades on end, to really believe your work is worthy of it, and to remain somehow soulful, sane and socially righteous all the while? Definitely, maybe. Either way, they are determined to find out for themselves. They refuse to think of themselves as a nostalgia act. Do we wish they would? Would we prefer that they stop standing up for their loves and shelve their creative selves?

I sure don’t. They have gone before me my whole life long, championing and amplifying thoughtfulness at every turn. I think of them as a celebrity cheerleading section—a pep band, if you like—of freedom movements the world over, celebrating those who hunger and thirst after righteousness, those among us (Lord, I want to be in that number) they occasionally refer to as “comedy people.”

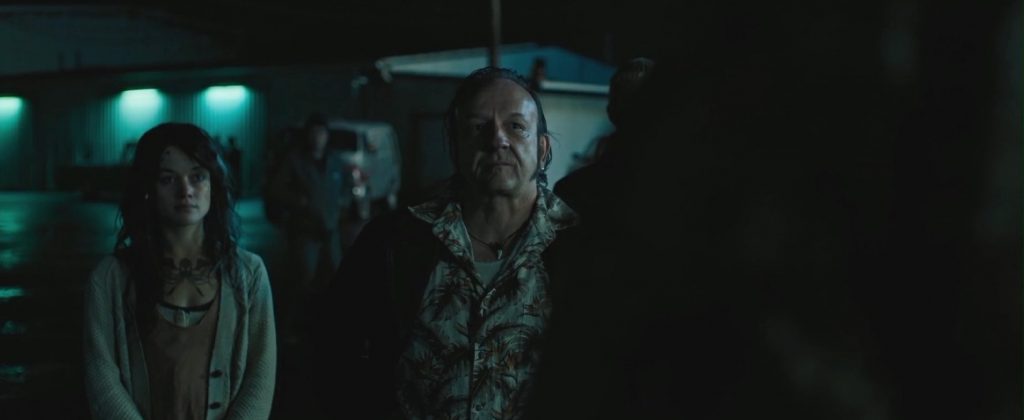

I Don't Want to Live In This World Anymore (2017)

Please welcome to LookingCloser.org a guest reviewer who has been corresponding with me about movies and film criticism for years: Daniel Melvill Jones.

Daniel lives in the foothills of Calgary, in Alberta, Canada, where, after five years of working for a little company called Apple, he's on a new adventure: earning his BA in English. His writing and photography are collected at danielmelvilljones.com, and he is the co-creator of Assumptions podcast. He tells me that when the Muse inspires him, he loses a lot of sleep — so I'm grateful that he stayed up late to share this review of this recent Netflix Original:

•

The world has overwhelmed Ruth (Melanie Lynskey). She’s resigned herself to a lonely routine of nursing dying patients before coming home to her ramshackle house in a working-class Portland neighborhood. When a particularly mean-spirited patient of Ruth’s dies with a racist curse on her lips, and Ruth comes home to find her house robbed of her laptop, anti-depressants, and her grandmother’s silver, her slow-building crisis reaches a breaking point.

She takes shelter on her friend's living room couch and breaks into sobs of desperation, comparing her nasty patient‘s death to her grandmother‘s good deeds. "It doesn't matter. They'll roll her out, and she'll become ... smoke. Just, carbon. And now, I'm the only one who remembers any of that, and pretty soon I'll just be carbon too. So none of it matters."

Those are the opening 10 minutes of the Netflix exclusive I Don't Feel at Home in this World Anymore — Macon Blair's directorial debut and winner of this year‘s Sundance Grand Jury. They articulate both Ruth‘s emotional state and the film‘s central dilemma. Ruth sees herself surrounded by assholes, so why does the world reward them instead of her? If this is all there is, how is she to respond to such absurdities?

With a stubborn determination rising underneath her timid exterior, Ruth realizes that the police detective (Gary Anthony Williams) is treating the crime as a standard case rather than a personal offense. If justice is to be served, she will have to be the initiator. This includes confronting one of the assholes in her life — a neighbor whose dog keeps pooping on her front lawn.

And so we meet Tony (Elijah Wood), who arrives fully formed with his backstory leaking out through details, like his obsessions over ninja sticks and nut milk. His barely contained rage is controlled through backyard weight lifting and devoted churchgoing. He is quick to surrender this bristling exterior, revealing a tender conscience and an earnest poise. After awkwardly apologizing for his dog's bathroom habits, he hears her story and joins in her outrage.

As Ruth and her new friend are drawn into a wider world of desperate drug addicts and miserable trophy wives, events spiral out of control.

We‘ve previously seen Blair in front of the camera in Jeremy Saulnier‘s Blue Ruin and Green Room. As a director, he borrows those films' mounting danger and knowledge of America‘s grim underbelly. But these darker elements are balanced by Blair‘s endearing characters and quirky sense of humor. He makes deft use of the film's 93 minutes, getting mileage out of minor incidents and reusing seemingly thrown-away props — like a plaster of Paris footprint cast — to propel the story forward.

In Ruth's eyes, she is the only victim in a world of ungrateful bastards who are constantly taking from her. But as her story expands into the backyards of her eclectic neighbors, the dripping forest campsites of the homeless, and crusty pawnshops of those on the fringes, she is sucked into their lives and learns that her desperation is felt by the poor and the privileged, the decent and the destructive alike Her pain is just a small part of world‘s sufferings. And through her self-righteous quest for her own justice, she becomes complicit in a sequence of violent and ultimately tragic events.

What then is the right response to such a cold world of grief and greed? In Tony, we see someone who is in many ways similar to Ruth. He is far from perfect, often too lost in his own world to notice his impact on others. But something inside of him flinches at the wrongs she commits. There is a permanence to his life that can‘t be explained by mere gas and carbon, suggested visually in several strange scenes, each lit with warm backlight.

In Blair’s vision, the world is a haunted place containing a swift and terrible inertia. The score’s lush synths, funky rhythms, and mounting electric guitar chords play an important role in coloring this environment. The story is self contained, an entertaining ride but revealing few additional insights on a second viewing. There are hints towards a higher hope, yet these glimmers can’t quite escape the growing sense of inevitable loss.

Does the bloody conclusion of I Don't Feel at Home in this World Anymore answer the dilemma articulated so eloquently at its beginning? Ruth expands beyond herself. In encountering Tony, she experiences someone with a conscience shaped by a devotion to a higher power. By entering into the messy lives of others, Ruth becomes less sure of her own self-righteousness; but not before learning the consequences of wielding a sharp blade.

In the endless rows of Netflix, this quirky thriller is worth seeking out.

Good Time (2017)

In Raising Arizona, H.I. McDonagh turns to Glen, the closest thing he has to a friend, and — perhaps softened for a moment by the beer he's drinking — asks, "Do you ever get the feeling that there's something powerful pressing down on you?"

On the surface, it's just a set-up for a joke: Glen makes a smart remark about how he's asked his wife to lose some weight.

But it's also one of those moments when the Coen brothers let us know that there are serious concerns running through the veins of their exaggerated comedy. Those concerns are economic: H.I. and his wife Edwina are living at the poverty level, where a life of crime begins to look like the only way to keep a family afloat. What other option is there, when the government takes such "a bite" out of every paycheck?

Of course, before the movie is over, H.I. and "Ed" will have learned something more profound than an economics lesson. (Combine their names, and you get "High Ed.") They'll have learned something redemptive about love, grace, and hope. But does the audience have the humility to learn alongside some dumbass criminals?

When I introduce my film students to Raising Arizona, I almost always have one or two in the class who dislike the movie because they can't find any compassion for a character who would commit a crime — even if it's a comedy, and even if the character suffers serious consequences. But most of the students get it: They understand that any character who resembles a human being will have character flaws and make poor decisions from time to time. They understand that it can be worthwhile to zoom in on even a hardened criminal to consider the forces influential in such dangerous decisions, the forces that can direct a human being to dangerous and even deadly folly.

Many if not most master filmmakers — from Vittorio De Sica to Martin Scorsese, Luis Buñuel to Danny Boyle, the Coen brothers to the Dardenne brothers, Terrence Malick to Michael Mann — cannot resist making movies about men dragged into the undertow of crime. Their antiheroes compromise to survive. They compromise to get what they want. They compromise in anger, lashing out at a system that oppresses them. They compromise in a sense of cynicism, realizing that the people who make and enforce the laws are just as guilty (if not more so) of breaking them. They compromise for love. Or maybe they compromise for the love of the game, the thrill of the chase.

Antiheroes used to be a mark of cinema for grownups — stories of morally ambiguous characters for audiences who have enough experience with art and literature to consider nuance and to appreciate that the world can't be conveniently organized into the Black Hats and the White Hats. In recent years, though, it seems that antiheroes have become the stuff of young-adult and even childrens' entertainment.

Consider Harry Potter, who frequently bends and even breaks the rules to accomplish what he wants, and is eventually understood, excused, and even congratulated for his exploits. I've been more disturbed by some of the Potter stories than I have been by "harder" stories for adults about characters who behave far more dangerously, particularly because Potter is so young and naive and yet is always rewarded for transgressing boundaries set by his elders. If I were a parent, I wouldn't want my child learning from that.

Consider how many of today's young cinephiles grew up with the idea that vampires are admirable and sexy... or, at the very least, pitiable. Instead of Dracula — a sinister, manipulative, and extremely wicked invention who can serve as a metaphor for real-world evils — they picture vampires as being like Twilight's gaunt, fanged Robert Pattinson as a misunderstood romantic hero whose vampirism is not something he embraces but a curse he must conscientiously bear in order to live. In a sense, vampires have become just another class of sympathetic crooks, driven to lawbreaking by pressures beyond their control. I like the complexity of some of these films, and I think it's irresponsible to portray any villain as irredeemable, as a lost cause from the beginning.

In view of all of this, I've been puzzling over two questions:

First: Can a movie still serve up a hardened criminal who is both truly human and yet also guilty of actual wrongdoing? That is to say — are we doomed to a cinema of villains who are either cartoonishly one-dimensional (and thus inhuman) or ultimately a victim of circumstance and beyond fault?

Second: Is the story of the criminal with a heart of gold exhausted? Shall we give it a rest for a while? It's such a common big-screen theme that it's challenging to find new narratives on the subject. What's more, it's hard to find filmmakers who aren't, themselves, so seduced by the glamour of crime that their movies become fantasies that turn lawbreaking into a sort of dream life, an intoxication, a way to experience vicariously what we lack the courage — or the craziness — to commit in real life.

*

So here comes Good Time, the new Cannes-celebrated film by the Safdie Brothers.

With their first two releases, Daddy Longlegs and Heaven Knows What, they've won praise for their raw, riveting portrayals of characters caught in compromising circumstances — characters who win viewers' sympathy despite dangerous inclinations. Now they've made their Taxi Driver, their defining film about a man whose experience has taught him that things like "law" and "order" are just obstacles in a game, and that the purpose of this game is to get his hands on the money it will take for him and his brother to live on the run. On the run from what? Clues along the way suggest an abyss of loneliness, disrespect, and perhaps some abuse. It's as if they've never known a moral compass, experienced a loving family, or learned to think about the consequences of their actions.

Good Time will be the Safdies' breakthrough to a bigger audience, largely because their lead character — Connie Nikas, the Energizer Bunny who compels the audience's attention by running and running and running from one chaotic circumstance to the next and having the dumb luck to stay alive — is perfectly cast. If a film like this had been made in the '70s, it would have starred Martin Sheen, halfway between the charismatic All-American Crook he played in Badlands and the All-American Military Hero broken down into savagery in Apocalypse Now. Connie needs to be handsome, charismatic, cocky, reckless, terrified, and unstoppable. So it's something of a surprise that he's played by Robert Pattinson.

But this isn't the Pattinson we know. This is Pattinson reborn, an actor who has thrown caution to the wind. All of the restraint, the repression, the slow-burn, the simmering energy that made him a generation's sex symbol in the Twilight movies has been cast aside. This can't be the same actor who played a mumbling introvert hiding behind a bushy beard earlier this year in The Lost City of Z. This is an actor unhinged, charging through chase sequences with so much energy that he makes Baby Driver's Ansel Elgort look like a guy who wouldn't know how to get a car from the driveway to the road.

The less you know going in, the better. Suffice it to say that Connie's life only makes sense if he and Nick, his mentally disabled brother, are A) together, and B) free from the supervision of the grandmother who apparently raised them. Where are the parents? What happened to Nick, that he behaves like someone who suffered daily concussions as a child? The answer to that question is probably the key to understanding these two young men and their unnatural commitment to one another. But buckle up — this movie doesn't have the patience to spell it out for us.

How will Connie and Nick break free from "the system"? It doesn't matter. Connie, declaring that nobody loves Nick as much as him, determines to make things up as he goes, dragging his bewildered-but-trusting brother with him. (The names are not accidental: We have the "Con," a criminal mastermind, and we have "Nick," which is a word for both a wound and a thief.) "The system" is anything that would separate the brothers or keep them from living independently, doing whatever they want whenever they want.

So that includes the psychiatrist (Peter Verby) who, in the opening scene, seeks to help Nick find the resources that he needs to live safely, securely, and under proper supervision. It's probably not an accident that the movie opens with a psychological interrogation a test that vividly recalls the Voight-Kampff interview at the opening of Blade Runner. The Safdies immediately want us wondering just how many pieces are missing from the Nikas brothers' minds and hearts, and just what has brought them to this place of desperation.

But "the system" also includes love. Connie's older girlfriend (Jennifer Jason Leigh, who seems doomed, since The Hudsucker Proxy, to play women so wretched and lost that they're almost intolerable) is clearly important to him only as a resource for money and transportation and anything else he might need to keep his desperate life together. He'll drop her the moment she's in the way. The same goes for the grandmother that he and Nick abandoned.

And so the film becomes a rush, as Connie draws his brother into a bank robbery scheme and a flight from the law — one that separates the brothers and sets the stage for Connie's most desperate acts. When he and Nick get separated, we stick with Connie until the end of the film, tracking his efforts to reunite with his brother, find the money they'll need to get away, and exploit anybody he encounters (a shuttle driver, an elderly stranger, an underaged girl, a drug dealer) to stay ahead of the cops.

It's easy to excuse Nick, Connie's brother. While he's prone to violence, he also gives us plenty of evidence that he's survived plenty of violence that came at him unprovoked. His participation in a pre-school-level care-center exercise late in the film reveals, for those paying close attention, just how lonely his life has been, how his world is entirely empty except for that single thread of faithfulness he has found in his brother. Played brilliantly by Benny Safdie, one of the co-directing brothers, Nick is an easy case for empathy.

But Connie is more complicated. We can see him sometimes pausing, held up by the faintest flicker of conscience: offering a sip of juice to a hospital patient whose room he is using as a hideout, or pausing to regret having drawn a minor into his scheme to recover misplaced drug money. But most of the time he is knocking people down without mercy, doing whatever he can to stay on the run.

And he makes it happen. Like a Looney Toons character, he gets in and out of the most impossible situations. In aerial shots of his car on the road or his bright red jacket burning like a comet through alleys and streets, he sometimes looking like Pac-Man trying to escape ghosts in a maze. He's not opposed to draining the bank account of an old woman by manipulating her dim-witted daughter, beating someone to the edge of death in order to steal their clothes as a costume, or setting a ferocious pit bull on someone he has baited into believing is his partner.

Pay attention, and you'll notice that there is something distinct about Connie in this cast of characters. He's the handsome white male. Give him a chance, and he'll dye his hair blonde. Is the secret to his success as simple as white privilege? Does he tend to command every scene that he enters by quickly asserting himself as an authority, and the rest of the world must comply or be smacked down? He's not the biggest guy in the film. He's not the strongest. He's not even necessarily the smartest. But he gets away with everything.

In an interview on All Things Considered, Benny Safdie says, "I do think that [Connie] is a mentally ill person himself. ... He's going to surround himself with people like him." In that sense, viewers might have good reason to read the film as a political commentary: Is this a film about the madmen running the country, about rich white racists who surround themselves with people as perverse as themselves because they know their unjust privilege empowers them?

"I think I was a dog in a previous life," says Connie. "In fact, I know that I was. That why they love me so much." The claim is preposterous — not his claim of reincarnation, but his claim of being loved. Who loves him, really?

Can we love him? I dare say that the Safdie brothers do: They film him his boundless energy in a state of reverent awe. But will audiences embrace him? Is he empathetic enough that he becomes a legitimate antihero?

I'm not so sure. Connie bears wounds that inspire genuine concern, but his hell-bent inclinations make him, in my opinion, more a force to be feared and stopped than one I would hope to see break free.

*

I am making Good Time sound heavy and profound. And it has all the ingredients of a complex and rewarding psychological thriller.

But the film's overpowering — I'm inclined to say overbearing — aesthetic is one of hyper-saturated colors, extreme noise, and constant sensory overload. I'm sure this is meant to represent the panic-attack existence of its protagonist. But the effect is one of constant interruption, of preventing the audience from having any chance to reflect on Connie's choices and consequences. That may be the point: When you live in this state of desperation, you don't have the luxury of a conscience. Maybe this is a movie meant to be deconstructed and discussed, not meditated on as we watch. If so, I can appreciate that.

But after a while, I found myself detaching from concerns about the characters, and falling in love with the kaleidoscopic colors, lights, shadows, and sounds instead. Good Time works much better for me as a run through a psychedelic amusement park, tethered to a tour guide who has lost his mind. I suspect that the films aspirations to seriously explore subjects like "white privilege" are largely hindered by its method.

The soundtrack, in particular, goes from supporting to overwhelming its subject. It's like being stuck in an '80s video arcade in which all of the synth-y sound effects are syncopated and harmonious and yet seem to be competing for dominance. The music is a bit like Vangelis on speed, too, which is, come to think of it, another suggestion that Blade Runner is a major influence here. If I'm supposed to notice the relationship between the two films, does that suggest that the Safdies wonder if these brothers have been "programmed," designed to live a life of uncontrollable impulse, so much so that they they seem mystified by their own occasions of conscience? Perhaps. But Blade Runner brings us to a place of spiritual awakening, to the beginnings of self-knowledge and redemption. Such things seem beyond the capacity of Connie Nikas.

If you come away from Good Time with enough presence of mind to feel heavy-hearted over the lack of love in this movie's world, instead of buzzing with glee over its rollercoaster ride, I'd say that you have a particularly resilient and powerful conscience, one that can withstand quite an assault on the senses. That probably says more good things about you than it does about the film.

In view of cinema's ongoing love affair with criminals, I'm interested in Connie's unique commitment to self-destructive momentum. Is he a tragic figure, a champion of brotherly love, a psychopath, a genius, or all of the above? If he's related to any other movie monster, he might be closest to the human meteorite played by David Thewlis in Mike Leigh's Naked — a seemingly unstoppable figure of arrogance, contempt, and bloodthirsty opportunism.

In his monstrous compulsions to lure others into his schemes, drain them of their resources, and cast them aside, Connie Nikas looks to me like the first real vampire that Robert Pattinson has ever played.