Three qualities of beauty

I think I might just scrap all of my syllabus explanations regarding how I grade essays and short stories in my writing classes. I'll just replace those with this passage from Umberto Eco's The Name of the Rose:

For three things concur in creating beauty:

first of all integrity or perfection,

and for this reason we consider ugly

all incomplete things;

then proper proportion or consonance;

and finally clarity and light,

and in fact we call beautiful

those things of definite color.

— Adso, in The Name of the Rose by Umberto Eco

Prospect (2018)

Anne and I have just returned, delirious with amazement, from a rainforest on a distant planet.

That is to say... my wife and I have just enjoyed the privilege of attending a filmmakers' hometown preview screening of Prospect. Granted, this kind of movie isn't for everybody: It's hard-core science fiction, full of spaceships, alien life forms, dangerous foreign environments, and heavily-armed explorers operating outside the reach of any law enforcement (that is to say, it's bloody and violent).

But Anne is both a poet and a sci-fi nerd. And I'm a film critic with a particular love for films like Alien, Blade Runner, and Star Wars; an SPU professor who encourages students to study, think critically about, and appreciate excellence in filmmaking; and an author of fantasy novels.

So this was like a dream date for us.

And it was a thrill to dive into a crowd of cheering sci-fi fans who were enthusiastic about this dream-come-true movie from the opening to the closing credits.

They had good reason. This wasn't just a screening: It was a celebration, marking one resourceful filmmaking community's arrival at the end of a long and taxing journey.

And while I didn't work on the movie directly, it was a joy to see the triumph of three filmmakers whose dreams took root during their years as Seattle Pacific University undergraduates: Zeek Earl, whose student screenplays I had the joy of reading and critiquing; Chris Caldwell, who as a young man dreaming of making movies encouraged me in my film criticism; and Brice Budke, who attends my church, and whose financial expertise made this unlikely movie possible.

A futuristic vision with classical bones

Prospect follows the story of a young woman named Cee (Sophie Thatcher of TV's The Exorcist and Chicago Med) whose father Damon (Jay Duplass) brings her along on an interstellar treasure hunt to a remote moon, where he's aiming to dig up a mother-lode deposit of gemstones that will help them get out of debt and secure a better future.

But when they run into other, similarly motivated scavengers, do they earn the right to be seen as heroes? Do they have the moral high ground? Or is this just a battle between ruthless hunters who will stop at nothing to come home with the treasure?

The answer — at least when it comes to Damon's decision-making — quickly becomes clear, and the storyline take a drastic and violent turn, leaving Cee separated from her father and frantic to salvage some kind of hope for survival in this strange and unpredictable environment.

Threatening them both are a mysterious pair of crooks-for-hire, and soon Cee will find herself in a situation where her survival depends on her ability to discern how much she should trust a gun-slinging opportunist called Ezra (Pedro Pascal, whose charisma steals the movie from his costars).

How's the movie?

Clearly, I cannot claim to be entirely unbiased in any commentary on Prospect, but I'll try to be fair. To make clear that I'm not suspending critical discernment, I'll begin here with matters I might have highlighted as needing a little more attention. But keep in mind, these are quibbles. If I didn't know these filmmakers, I would still have been powerfully impressed.

So let's start with the screenplay.

Prospect, while it boasts exquisitely designed (and handmade) costumes, sets, and world-building enhancements, is somewhat lacking when it comes to depth of narrative and complexity of character development. And the weakest link is, unfortunately, the main character: Cee.

Cee wins our sympathies primarily because she is young and vulnerable, and characters who get our attention because they're vulnerable may hold our attention through suspenseful scenarios, but they don't live on in our imaginations unless they have distinctive personalities and memorable backstories that give us particular cause to hope for not only their survival but their success. Cee is defined by sketchy references to her pop-culture preferences (playlists of futuristic pop music, a particular young-adult storybook), the absence of her mother, and her sense of uncertainty about her birthplace. It's a decent foundation, but I would have liked to get to know her better.

Still, she's compelling. And in the role, young Sophie Thatcher is remarkably convincing: She makes the character persuasively knowledgeable about space travel and various scientific procedures (like performing surgery on alien specimens to harvest their internal surprises, as well as surgery on other human beings to save their lives), and she gives Cee an authentic mix of fear and resourcefulness in the midst of crises.

This is enough to bring the character to life, but we end up with more questions about her than answers. The film might have been stronger if the script had revealed more about how Cee's passions — music, literature, her longing for her mother, and her budding conscience — shape her decisions. A good point of comparison would be Mattie Ross, the young heroine of the Coen brothers' adaptation of Charles Portis's True Grit (a story that clearly served as inspiration for Prospect). Mattie's opinions are always clear, but so is the arc of her character development: We want her to survive not only because she's suffering, but also because she's on her way into wisdom.

Perhaps the primary reason that Prospect comes up short in Cee's characterization is because of its prioritization of — and, let's face it, delight in — thrillingly staged face-offs, showdowns, shootouts, and narrow escapes. While I would have preferred a finale less reliant on pew-pew-pew!, stab-stab-stab!, run-run-run, fight-fight-fight! , I'm well aware that I'm in the minority as a conscientious dissenter when it comes to resolving sci-fi adventure with violent clashes. For fans of the genre, scenes of spectacular combat are often the main event, the biggest thrill, the basic building blocks of the narrative.

So most audiences are going to come away from Prospect having seen what they bought tickets to see: spectacular, otherworldly visions that create almost unbearable suspense, culminating in an explosive finale.

And on that count...

When it comes to sci-fi, this movie learned from the best.

In the tradition of Alien's handmade hardware and effective intimacy, Prospect makes us believe by avoiding digital wizardry for most of its running time (the few outer-space spectacles are dazzling, immersive, and state-of-the-art). Almost everything we see onscreen is real, made by brilliant craftspeople, giving a rough and lived-in detail to every space traveler's helmet, every steam-punky weapon, every bizarre alien life form unearthed at the treasure-hunter's dig. I love how Cee's space gear and clothing are decorated with insignias representing her favorite pop-culture phenomena, just as my own MacBook is busy with the logos of bands, brands, and vacation destinations.

What might be the film's most powerful advantage is its Pacific Northwest rainforest setting, in which the play of light, shadow, greenery, clouds of dust and insect life, and more combine to offer an environment that stands out in an era of digitally constructed landscapes. If Terrence Malick were making hardcore science fiction films, they would look a lot like this.

And it isn't just the hardware. The adventure, as sci-fi action goes, is intense, frenetic, and immersive. This isn't the first space adventure set in a glorious rainforest, but Return of the Jedi set us rocketing through the trees on speeder-bikes; by contrast, these travelers have to run for their lives on foot, burdened by heavy armor, stumbling through moss and vines, clambering over fallen trees, and beset on all sides by clouds of space dust and dangerous alien organisms. And that makes the gunfights and hand-to-hand combat between Cee, her father, and the rifle-wielding enemies that much more visceral and unsettling.

The intimate and difficult chemistry between Cee, her father, and Ezra is always engaging and tense, largely due to the fact that their conversations buzz, snap, crackle, and pop through unreliable speaker-headset acoustics. Straining, I caught only about half of what the characters said, but that's not a problem. It seems like a deliberate strategy to increase a sense of realism and to make us lean in to pay closer attention.

This is the most believable sci-fi stuff I've seen in a long, long time.

What's more, it's also meaningful.

A hunter with a heart of gold? Not exactly, but...

The film's most meaningful work is done in the character of Ezra, who arrives as a frightening villain, and who remains a frightening villain, but one who shows increasing potential for redemption.

In a scene-stealing performance that is two parts Nathan Fillion (Firefly) and one part Tom Hardy (Mad Max: Fury Road), Pedro Pascal is a force to be reckoned with. And speaking of the Fillion resemblance, the dialogue in Prospect — best realized in Ezra's voice — plays like a minimalist episode of Firefly: this film is more a Western in structure and dialect than an exploration of science fiction concepts. It's The Treasure of the Sierra Madre stuck together with superglue and staple guns.

The story finds its moral center not in Cee, but in Ezra. He's convincingly reckless, self-serving, and unhesitatingly violent. But as he follows his instincts for the sake of survival, he also reveals a clear awareness of the compromises people make for their own advantage, and begins to develop an admiration for Cee's similar drive and her willingness to compromise. Might he end up teaching Cee something valuable, perhaps lessons he's learned the hard way? Might he even be capable of caring?

You'll see. If I say more, I'll spoil the fun.

Overall, Prospect tells a story about how opportunism and greed endanger the bonds that keep us all alive, and — for one essential middle scene, during a long walk in the woods — about how stories help us find meaning and purpose in an existence that wants to convince us that survival is all that matters.

And while I might hope for a sequel that digs deeper into the virtues of character and the power of poetic sensibilities, I am absolutely satisfied by this film's convictions about the power of tangible particularity, its wonderfully realized world, and its go-for-broke efficiency, making the most of every moment, every prop, every ray of light, and every leaf and caterpillar in the forest.

Ready? Into the woods!

Go see it at the Seattle International Film Festival... or you'll have to wait for its eventual theatrical release

Prospect will have several screenings at the Seattle International Film Festival in the next couple of weeks.

P.S.

Anne loved it.

Game Night (2018)

Strange, but the last time I watched a movie about a group of friends getting together to play games, it was set in Iran. About Elly, a film by the great Asghar Farhadi, explored tensions burning beneath the surface of civility in Northern Iran. And the suspense skyrocketed the moment that one of the players disappeared from the scene. We suddenly realized that our characters were caught in a far more serious game than we'd thought.

Now we have another film built on a similar scaffold: Game Night is also about friends, games, secrets, lies, a disappearance, sudden violence, and the overturning of audience assumptions. Both films are about couples questioning how much they really know about each other.

But where Farhadi had big socio-political ideas on his mind, screenwriter Mark Perez just wants to have fun. Game Night is a playfully subversive comedy, one so tightly wound with smart and surprising jokes that I found myself trying to remember the last time I'd seen a commercial comedy full of movie stars that captured and held my attention so completely. And in searching for comparisons, I found myself reaching all the way back to the late 1980s.

You've been to game nights, right? You know the folks who are so bent on winning that they'll sometimes spoil the fun? Perhaps you — like me — are that person. Max and Annie (Jason Bateman and Rachel McAdams) are those players. They're a match made in Milton Bradley Heaven: the Beatrice and Benedick of Backgammon, the Johnny and June of Jenga, the Sonny and Cher of Scrabble. And after these game-night opponents become allies and tie the knot, they then make a habit of tying their Pictionary pals into knots.

Patient and willing to play along are Michelle (Kylie Bunbury), Kevin (Lamorne Morris), and the village idiot — Ryan (Billy Magnussen, deliriously dopey) — who always brings a pretty new contestant as a date. They have a lot of history, these six socialites, and we quickly learn that this history has given them some hard lessons.

One of the most challenging lessons involves an outcast: Gary (Jesse Plemons), a widowed and glum policeman, who knows how to kill a party's joy. Keeping Gary out of Game Night proves a tough puzzle for even Max and Annie to solve.

But there's a bigger problem: Brooks (Kyle Chandler, surprisingly unhinged), Max’s boastful brother and the most competitive of them all, is back in town. Speeding up in a sports car, he's clearly the bane of Max's banal existence. And so, when Brooks invites the group to a game night at his place, we can sense that the whole event will be rigged, and we start rooting right away for Max and Annie to uncover the ploy and beat Brooks at his own game.

But then it all goes gloriously wrong, as someone in the party is suddenly removed from the game board, and the pieces are scattered — players going search of clues to what might be a trick or something more traumatic. It certainly isn't a treat for them...

... but it is for us. Directors John Francis Daley and Jonathan Goldstein remind audiences that comedies are best when they're trimmed to perfection. I blame Judd Apatow for burning me out on big-screen comedies; his movies tend to be so bloated with sophomoric indulgence and unnecessary tangents that, while I might laugh along the way, I never feel compelled to go back for another go-round. Daley and Goldstein make every moment count. And they throw in some wild surprises, including appearances by the great Jeffrey Wright and the great Danny Huston.

Putting the game in Game Night will mean, of course, that the movie wants to outwit us. And it tries. Some of us will figure out the trick. Some of us will wish the trick had been something cleverer. As if admitting disappointment in its own climactic surprise, it tries another surprise, and that only makes things feel more implausible, as if the movie is getting desperate to blow our minds. (Clearly, I'm trying to keep the curtains closed so you don't glimpse the climactic details that I found shrug-worthy.)

But while this might have been a better movie if it had found a more satisfying conclusion, the experience — like any good game night — is more about the good company of the players, the joy of the game, and, for adults, the kind of play that can make us feel like kids again.

Give extra points to Rachel McAdams, whose performance has a hint of mania to it. You're going to want more McAdams comedies after this: She lifts the movie to another level of energy, making us believe in her alarmingly competitive impulses, while Jason Bateman weighs it down a bit, making no effort to give us a distinct character.

Watching Game Night, I felt like I was back in the 99-cent movie theater I visited every week in the late '80s, watching comedies that starred Tom Hanks and Shelly Long, or Tom Hanks and Meg Ryan, or, well, just Tom Hanks — particularly The 'Burbs, which is clearly one of this movie's most significant inspirations. Note the panoramic views of a suburban neighborhood, in which any house might be holding secrets. Not the familiar sense of paranoia and suspicion, as if the neighbors might be up to something nefarious. (The most specific 'Burbs reference is the sight of Gary, that unnervingly watchful neighbor, who is frequently seen cradling a little white poodle.) It's a vibe I haven't felt since Joe Dante was at the peak of his powers.

The only regrettable move that Game Night makes is in its curious insistence on revisiting its ugliest joke — a nasty locker-room gag about self-gratification. I hate that I have to bring this up, but... gross.

I'm eager to watch Game Night again, and I suspect I'll like it even better the second time – the test of any great comedy. (How quickly Taika Waititi's What We Do In the Shadows rose in my estimation from a hilarious Christopher-Guest-like satire to one of my top five films of 2014, all because of a riotous second look.)

But I really think that this movie, like classic board games, will come to be loved as a classic party movie — one that inspires rooms full of friends to quote their favorite lines and cheer for their favorite characters. And any time a movie comes along that can become a binding thread for a community, one that unites them in laughter — that's a good thing.

The Theology of the Coen Brothers? A Conversation Between Matt Zoller Seitz and Jeffrey Overstreet

The following conversation between Matt Zoller Seitz and me was originally published at Indiewire.

A reader recently asked me if I could redirect him to that conversation. I told him that his timing was uncanny, as I was just about to share that dialogue with students in my "Film & Faith" class at Seattle Pacific University. But when I looked it up, I discovered that something has gone wrong with the formatting of the piece at that original location, making it difficult to read. Unable to edit that website myself, I inquired about publishing the piece here in an updated format.

So, with permission from Indiewire, here is the conversation that occurred at Seitz's invitation, which was originally titled "O Coen Brothers, Where Art God?"

Matt Zoller Seitz's Editor’s note:

So, I was watching Raising Arizona for the 400th time the other night, and laughing at the sheer Freudian-Jungian comic bookish-ness of having the lone biker of the apocalypse appear in conjunction with the hero, H.I. McDonough, having a dream. It’s almost as if he was summoned by the hero’s dream—as if he’s a metaphor made flesh. You can see the biker as a physicalization of the hero’s internal struggle to put down the outlaw within, and become domesticated. The biker is an id creature erupting from inside of H.I.—the return of the repressed, I guess Freud might say—only he’s riding a giant Harley and he’s got shotguns and grenades.

And then I started to fixate on something else: the sense that there’s an equally strong religious or spiritual dimension to that scene. It’s as if the biker is a demon being summoned like a supernatural creature from a horror movie or an ancient folktale. Ed doesn’t call him a “warthog from Hell” for nothing.

And this in turn got me thinking about all the other instances in Joel and Ethan Coen’s filmography where it seems as though supernatural forces, or at least nonrational or uncanny forces, are at play—where what you’re seeing doesn’t quite seem to be metaphorical, if you know what I mean. There’s an angel and a guardian angel in The Hudsucker Proxy, and the actual stoppage of time. The villain in No Country for Old Men seems like Satan himself, or a demon from hell, not unlike that biker from Raising Arizona. The bad guy in The Ladykillers is basically Satan, doing battle with an old widow, and their dynamic recalls Robert Mitchum and Lillian Gish in The Night of the Hunter, which was a Manichean story that quoted the Bible and from folktales and fairytales rather liberally. A Serious Man draws on Jewish theology and folktales quite pointedly, and it ends with what looks rather like a miracle, or maybe a curse, or the apocalypse; and in any event, the film seems to connect with No Country for Old Men, which also has a fire-and-brimstone, or Revelation, kind of vibe.

And at a certain point I just thought, “I need to get Jeffrey Overstreet to talk to me about this, and see what he thinks.” Jeffrey is a novelist and one of my favorite film critics. He writes with great lucidity and compassion about all sorts of movies, from all sorts of angles, but what I value most about his work is the theological-moral perspective he takes on things. He’s not a dogmatic scold, sifting through popular art looking for work that fits a rigid world view; he’s more interested in Looking Closer, as his blog title suggests, to discover what, if anything, the work is saying. That’s what I think he does in this conversation.

— Matt Zoller Seitz

Matt Zoller Seitz:

Do the Coens believe in God? Can we even say that for sure? Do they believe in the non-rational, the supernatural? Or are they just pranksters pulling our chains and hoping to spark conversation pieces like this one, while they sit there snickering? What do you think?

Jeffrey Overstreet:

As Emily Dickinson says, “Success in Circuit lies….” So, forgive me, but I’ll get to that question about God in a circuitous fashion.

I think it’s great that the scene that started your engine for this conversation is “The Emergence of the Lone Biker.” I think it’s one of the most intriguing in the Coen brothers’ whole repertoire. (I can’t say “repertoire” in this conversation without giving it an exaggerated Southern pronunciation, just as a Coen brothers character would say it.)

Anyway, that scene is not only resonant with apocalyptic, supernatural implications — it’s intriguing in that it serves as one of several portals into their other films. It’s one of those recurring motifs, those strands of thread that stitch the Coens’ whole body of work together.

Raising Arizona’s H.I. has the Lone Biker, who greatly resembles Sheriff Bell’s nemesis in No Country for Old Men — Anton Chigurh. Both are lone figures of chaos, wrath, death, and judgment, prone to blasting “the little things” (bunnies, birds) and the innocents. In fact, there are shots of H.I.’s troubled sleep, in which he dreams of apocalyptic things, that mirror Llewelyn’s troubled sleep after he brings the money home in No Country. There are strong connections between H.I. and Llewlyn, fools-in-arms right down to the way that their stolen goods drag them down into much darker and more frightful trouble. The allure of “what other people have” — money, a family, power, fame — is the pathway to hell for so many Coen characters.

But there are a variety of crooks in the Coens’ world. There are boneheads like H.I. and Llewelyn, who take what doesn’t belong to them and regret it. There are power-mad figureheads and CEOs and “Men Behind Desks” like Waring Hudsucker in The Hudsucker Proxy and the Big Lebowski in the film that bears his name, and the Hollywood studio execs in Barton Fink, and Leo in Miller’s Crossing… crooks who are insulated and egomaniacal, corrupt and rotten to the core. There are flimsy fools of apathy and inaction, like Larry Gopnik in A Serious Man and Ed Crane in The Man Who Wasn’t There. Those who insist on forcing the world into order through the power of law —Sheriff Bell in No Country, Tom Reagan in Miller’s Crossing, Rooster Cogburn in True Grit — end up despairing, unless they act in allegiance to some kind of higher law, embracing mercy and mystery.

In fact, the only characters I can think of who aren’t seriously messed up are Marge Gunderson in Fargo and Mattie Ross in True Grit.

So, back to your question about God: I think the Coens suggest him via negativa. They show the incompleteness and insufficiency of a vision that leaves God out. There are clearly human evils at work —evils of foolishness, carelessness, folly, and evils of greed and deliberate violence. But there are also evils of apocalyptic, seemingly supernatural proportions. As No Country demonstrates, good deeds and the power of law are not enough to save the world. Ultimately, the best we can do is seek justice, love mercy, and walk humbly in the presence of something greater than ourselves.

The whole “white hats versus black hats” view of the world

MZS:

It’s very elusive, very tricky, very coy, I guess you could say — the way they deal with these issues, or don’t deal with them.

From Blood Simple onward, the Coens have offered up plot after plot after plot wherein good and evil square off, but both good and evil are as comical as they are formidable. Good is noble but rather dull, or conventional and predictable. Evil—or corruption—is more exciting, I suppose, or at least superficially sexier than good, but kind of pathetic in the long run. Anton Chigurh is distinguished by his isolation and his grotesqueness. The crooks in Fargo bang prostitutes in hotel rooms after a Jose Feliciano concert, and seem to last all of ten minutes before Johnny Carson comes on; meanwhile, Marge Gunderson and her husband seem truly satisfied in their “boring” suburban home, in their shared bed.

In the Coens’ work, the settled, slightly boring but essentially satisfied “good” collides with the evil, the chaotic. And the fate of the world, or at least these characters’ own little world, is at stake.

But here’s the really interesting part for me: in a Coen brothers film, you can never be entirely sure if good really defeated evil or if evil destroyed itself, through overconfidence or inattention or just plain bad luck.

Luck is such a huge factor in the Coens’ work. Blood Simple, Raising Arizona, Miller’s Crossing, Fargo, Barton Fink, Burn After Reading and so many other Coen brothers films have plots that seem driven by mysterious clockwork forces that could either be weighted in favor of “good” or not . . . . But then again, you kind of can’t tell. And while I think I know what the Coens think of their bad guys, I can’t be entirely sure if what I’m seeing onscreen is a condemnation, however comic, or merely a presentation.

Are they moralists, or are they anthropologists?

JO:

I think they’re out to subvert the whole “white hats versus black hats” view of the world. I think they do believe in good and evil, but they seem to see all of humanity as having one foot planted in both camps. Their character cannot be “the Good,” but the more they “lean in” toward love, the more peace and hope and goodness they find.

Think of H.I.’s final dream, the one about growing old with a family and feasting. Think of Marge and Norm celebrating the 3-cent stamp and the upcoming baby. Think of how the most moving and inspiring moment in True Grit comes not when Cogburn blasts the bad guys, but when he carries Mattie across miles and miles trying to save her. The more these characters try and crush evil, or to diagnose it with the intellect, or try to make themselves better through the sheer force of will, the more hopeless and sick at heart they become.

Think of poor Barton Fink, who rants and rants about intellectuals who want “to insulate themselves from the common man, from where they live…” And what is Barton doing? He’s recoiling from his neighbor, trying to insulate himself from a “common man.”

But the wallpaper keeps peeling away, and he will eventually have to deal with the ugliness, the corruption, that is common to everyone. His only hope for relief, it seems, comes when he learns to carry his “box of corruption” with him, rest, and look around at what beauty he can find in the midst of the world’s seeming-absurdity. (And what is that diving pelican in the final moment but an affirmation that there is something absurd in the sublime, and something sublime in absurdity?)

In the same way, Sheriff Bell in No Country, for all of his efforts, must sit at the table with his wife, confess to a sense of hopelessness and futility, and “lean in” to a dream, to a sense that maybe there is a glimmer of hope, but it exists beyond our control.

That is why I think there is profundity in Delmar’s baptism in O Brother, Where Art Thou? It’s grace. A fool like Delmar, and maybe even a fool like Ulysses, can “be saved” when he accepts grace. When these characters have a sort of Damascus-road encounter with something greater than themselves, and allow the gravity of that to draw them away from their wicked ways. “Well,” he tells his friends, “as soon as we get ourselves cleaned up and we get a little smellum in our hair, why, we’re gonna feel 100% better about ourselves and about life in general.” That doesn’t work. But he will begin to feel better about himself when grace inspires him back toward the straight and narrow, when love “cleans him up.”

Even Mattie Ross, for all of her righteous anger, pays a heavy price for trying to fix the world by force. After she is “disarmed,” she seems to realize that the greatest reward of her adventure was not justice achieved by violence, but the mysterious bond that formed between her and Cogburn, who strove so mightily to help her. The Coens’ paint a picture of a world botched beyond belief, and beyond humanity’s capacity to repair. But there is something transcendent about what those characters who know love enjoy. They touch something that operates in, through, and beyond the human sphere.

Hey, even Private Detective Visser in Blood Simple has a sense of it. He’s preoccupied with Russia, where “everyone pulls for everyone else.” But in Texas… “you’re on your own.”

Just drifting through, like the tumbling tumbleweeds

MZS:

I want to dig into this a bit more, this sense that bedrock Judeo-Christian concepts inform the Coen brothers’ filmography. I think it’s self-evidently true to say this, like saying that David Cronenberg is fascinated by the fragility of flesh and its overlap with technology, or that Steven Spielberg has daddy issues. But at the same time, it’s an observation that conflicts with the popular perception of the Coens as being cold or disinterested moral relativists—or at the very least, film school pranksters, guys who are all about homage, and who don’t believe in anything, really.

They certainly do hold their cards pretty close to their vests in that regard. But maybe not as close as detractors might say?

They’re essentially comic storytellers, even when they’re making supposed dramas, but after watching their work for nearly thirty years, I’ve concluded that deep down, they’re among the most moral, even moralistic, filmmakers working in the Hollywood mainstream. Good and evil aren’t metaphorical to them, even though they take on overtly symbolic guises at times. There is a right way and a wrong way to live. They do judge the corrupt, the weak, the impulsive and the greedy in very unflattering terms. When the bad guys in The Ladykillers get foiled, they seem to be struck down—smitten as if by God himself, then dumped onto a garbage barge like, well, human garbage, I guess. And then there’s that line in the police car near the end of Fargo: “There’s more to life than a little money, you know. Don’t you know that? And here ya are, and it’s a beautiful day. Well, I just don’t understand it.”

What you say about surrendering to a higher power, or to the possibility of enlightenment or even “rapture,” as a Christian might put it, runs throughout Joel and Ethan Coen’s filmography—that sense that you have to let go, to surrender to cosmic forces rather than fight them, and let the universe sort itself out. That’s not to say that the outcome will necessarily favor Good, or even favor you personally—just that, as the films tell their stories, the universe has a way, and we don’t necessarily know what That Way is, and ultimately we’re all just drifting through, like the tumbling tumbleweeds in The Big Lebowski.

Do the Coens want to try to make sense of any of this? I don’t know . . . There are times when they seem as baffled as the rest of us. They certainly have a fondness for narrator characters who try to put everything in perspective and fail miserably and very amusingly. The narrator Moses—what a name!—in The Hudsucker Proxy, or Sam Elliott’s cowboy in Lebowski, kind of lose their places as they’re trying to put a frame around things. The Coens seem to get a kick out of tantalizing us with answers while laughing at the very idea that there could be answers.

JO:

Well . . . they sure don’t seem to think we’ll know answers on this side of Sheriff Bell’s dream. But there is something out there. There is somebody running the clock.

I’m uncomfortable with the term “moralists” when it comes to the Coens. Mere moralism isn’t enough. Moralism is just arithmetic: A fool plus his money are bound for hell. That’s not an accurate summation of their sensibility, because look at how the loving and the righteous and the innocent die miserably in their films. Exhibit A: Lana, from No Country. “Karma” is far too narrow a concept for the Coens.

Furthermore, there is too much respect for mystery in these films for the storytellers to be mere moralists.

Now, I don’t think the answer is to start trying to pin a religion on them. A Serious Man makes it painfully clear that religion can become like Arthur Gopnick’s book “The Mentaculus” … a labyrinth of laws and reasoning that ends up making as much sense as the absurd, self-contradicting legal defense of Ed Crane in The Man Who Wasn’t There.

Religion, while it binds communities and brings meaning through ritual, is ultimately not enough. I’m not willing to brand the Coens as “covert Christians.” And even if I did, the word “Christian” is about as meaningful anymore as the word “conservative” or “Democrat”, or the term “the American way.” It means a million things to a million people. But they are definitely drawn to a vision of the cosmos that resonates with my understanding of Christ’s teachings. That is to say that “righteousness,” the ways of religion, and the law-focused method of an “Old Testament” worldview, are ultimately insufficient.

We cannot earn our way to heaven by being good. We cannot save ourselves. The Coens know that “all have sinned,” and they know that “the wages of sin is death.” Everybody is likely to die miserably in their movies, whether as a result of their own evil or someone else’s.

But there is something out there, some kind of offer of grace, and when we glimpse that, goodness happens in us. We begin to love not for selfish reasons, but as a response, as a reflection, as if we are instruments being tuned up by something greater than ourselves.

No, I think that the clearest summation of their worldview comes from Mattie in their True Grit remake: “You must pay for everything in this world, one way and another. There is nothing free except the grace of God.”

The small and humble people of the world

JO:

On a side note, while I don’t see anything as simplistic as a “Christ figure” in the Coens’ films, I do love the way some have speculated that “The Dude” himself is a “holy fool” who acts as a sort of signpost toward Jesus. We see him doing carpentry (badly). We see him “taking it easy for all us sinners.” He walks around in a robe, and hangs out with all manner of fools and crooks without an inclination toward judgment. He even bowls alongside a “false Christ” (“The Jesus”). And what does he drink at the grocery?

Okay, I know, it’s a crazy stretch, probably a coincidence, but I love the suggestion of “dual nature of Christ” in the carton of half-and-half. (Cathleen Falsani has a whole book on this, by the way: The Dude Abides: The Gospel According to the Coen Brothers.)

The Coens love the fact that God uses the small and humble people of the world to shame the greater.

MZS:

Well, I didn’t want to come at this head-on, because it seems very un-Coen-like, but you went there first: I take it you believe that the Coens believe in God?

JO:

Accept the mystery.

Okay, more directly: I think they believe in grace. I think that they’re likely to give the great mystery enough respect that they won’t name him. They’d rather show than tell. Or, if you will — they don’t believe in God, they believe in G-d. That’s my inclination.

But then again, many great artists who profess to profound doubts, cynicism, agnosticism, have given us inspiring theological art. Listen to Woody Allen say he doesn’t believe in right and wrong, or good and evil, or God. But then he tells stories about men who, when they commit all manner of sins, are haunted, conflicted, dissatisfied.

Perhaps the Coens’ films are another case of the art knowing more than the artists. And that is what should matter anyway. I don’t much care what the artist believes. I care to discern what the art reveals.

Annie Dillard once wrote, “There is no such thing as an artist: there is only the world, lit or unlit as the

light allows. When the candle is burning, who looks at the wick? When the candle is out, who needs it?But the world without light is wasteland and chaos, and a life without sacrifice is abomination.” I love that. Give me the work and its mystery. Don’t ask me what the artist believes.

MZS:

Then what do you think the work reveals, about God, about faith, about the possibility of a moral code that can help us make sense of things?

I feel like the Coens are very culturally conservative beneath it all, and not anything close to the snickering secular humanists you might think they are, considering their reputation as pranksters. I felt like the Nihilists in The Big Lebowski were the Coens’ playful mockery of critics who’ve called them Nihilists—”Ja, we are nihilists, we believe in nothing!” they repeat, chasing the hero through his dreams with huge castrating scissors. The Coens aren’t nihilists. They believe in something. And yet they don’t spell that something out. It emerges organically while you’re watching their films, maybe because they’re not entirely sure what “it” is, either. They can see the contours but not the details, maybe? It’s tricky and very subjective, what they’re doing, and what we’re doing as we watch they’re doing. It’s like looking for shapes in clouds. You see what you want to see, and maybe you’re right to see it, or maybe if you were a couple of miles in the other direction you’d see something else entirely.

There’s an aspect to their work that reminds me of going to Sunday school as a kid, and I don’t mean that as a knock, not at all. It also reminds me of hearing my grandfather tell stories about his childhood by way of moral instruction. They’re illuminating the universe, or at least exploring it. But they’re not going about it in a didactic way. There’s something fundamentally humble about them, as visually and structurally and generically flamboyant as they sometimes are. I feel like they’re figuring things out, too—figuring themselves out, figuring the world out, and laughing at themselves, and the rest of us, for thinking there’s An Answer to anything.

JO:

I get why it reminds you of Sunday School, but I never get the sense that they’re lecturing. I get the sense that they’re holding up a mirror to all of humanity, themselves included, and showing us

what a hilarious and pathetic mess we all — Coens included — make of things. I think Barton Fink has self-critique built into it — they’re making intellectual movies, but they know that even ambitious art like that can only go so far. Their constant nods to Sullivan’s Travels, especially in Hudsucker and O Brother, tell us that they know that there is redemption in a certain kind of self-effacing laughter. I suspect they see themselves as Larry Gopniks… exasperated by the insanity in the people around them, but then capable of perpetuating that same destruction with their own judgmentalism and compromise.

What many people perceive as condescension, as “sneering at their characters” … I disagree with that characterization. I tend to see that as a sign of their humility, maybe even compassion, and above all… affection. We are deeply moved when Tom Reagan shows mercy to Bernie in Miller’s Crossing. We feel that something has died when he becomes the figure of wrath later. Visceral responses like that are what we need in order to remember what is really at stake in this world. And I love their films for triggering those responses, and making me look for signs of beauty and grace in this world. As Dylan sings – and I can’t wait to see them visit Dylan’s scene in their next film! — “It’s not dark yet, but it’s gettin’ there.”

Chuck Jones clearly loved his Looney Toons characters. He loved their language, their exaggerated features, their cleverness, their vanity, their folly. But he loved those characters. And his depictions of human folly in the circus of those cartoons was a form of insightful humility, about all of us ridiculous human beings. So I think the Coens’ work disturbs audiences because it reminds us that, contrary to so many Hollywood messages, “being good” isn’t the answer. Being good is good, but—as Bill Murray says in Wes Anderson’s Moonrise Kingdom—it isn’t enough to fix things. Their movies “ring true” when they remind us that there is a “wrath that’s about to set down,” as Rooster Cogburn says. If that wasn’t true, it wouldn’t strike such a resonant chord in audiences. The Lone Biker of the Apocalypse in Raising Arizona is coming, and there’s something elemental and true about him. We ourselves have unleashed him, as H.I. declares. In No Country, we’re warned that we “can’t stop what’s comin’.” There is a moral code, yes, and we violate it in countless ways. We’re screwed.

But their work doesn’t stop there. It engages and encourages us by leaving us with moments that transcend all of that doom, all of that destruction. Their suggestion of the possibility of grace is not so much a sermon proclamation as a desperate hope.

And it wouldn’t move us so deeply if the anticipation of grace weren’t built into us somehow. It moves us because, on some level, we know it’s true.

Ready Player One (2018)

Like an espresso shot of pure nostalgia, the opening pulse of Van Halen's "Jump" gives the new Steven Spielberg movie a shiny, synthesized start. And you can bet that moviegoers everywhere feel a rush of adrenaline and lean forward, ready to play.

Well... some moviegoers, anyway.

Particularly, those who grew up in the '80s.

Specifically, guys who grew up in the '80s.

Dare I say white guys who grew up in the '80s?

Yeah, this movie will be most popular among those nostalgic for a particular period of pop culture, in which movies followed particular formulas. Guys were meant to rise above their circumstances and Fight the Power, embracing The Hero's Journey. Girls, while it was cool if they showed some attitude, were mostly trophies to be won. It was best to accessorize with the coolest vehicles and weapons. And scowling corporate villains could always be taken down by a diverse gang of who would enable the hero to take a well-timed shot when the moment came, resulting in an orgasmic explosion of light and noise.

I can't help but pause right there. Let's remember the fact that while "Jump" was a huge hit — a blast of radio sunshine that could (forgive me) jump-start anybody's heart and make anything seem possible — it was also controversial with Van Halen fans because it sounded so much like a sell-out, a genuine rock band famous for its guitars suddenly opting for electronic hooks that any five-year-old could play on a cheap Casio keyboard.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4TgAVD_exzg

What prompted this obvious compromise for the rock band that almost all Americans had air-guitared to at one time or another? The pressure of corporate influences? An insatiable appetite for a blockbuster? Whatever it was, Van Halen stopped behaving like a rock band and decided to go for a pop-star makeover. It didn't matter that David Lee Roth said that the song was inspired by a suicide-jumper he saw on TV: the song sounded like the farthest thing from dark and dangerous. It was a pep talk that could just as well have been performed by Huey Lewis and the News (and their upcoming hit "The Power of Love," which pumped like rocket fuel through Back to the Future, sounded an awful lot like it). Van Halen had lost something essential in the name of crowd-pleasing.

Similarly, Ready Player One is both a flashy, fun adrenaline rush and a baffling artistic and commercial compromise that seems to drain integrity from everyone involved — particularly its director. It has all the exterior dazzle that used to make summertime adventure movies into box-office hits. But there's a hollowness at the center, the sense that something authentic has been lost in the prioritization of crowd-pleasing over vision. This movie is, for Spielberg, a lot like what would happen if U2 recorded a record that was an homage to all of the contemporary Christian bands who wanted to sound like them, and thus the masters ended up reduced to sounding like their own mediocre imitators.

There were good reasons for concern. Ernest Cline's blockbuster YA adventure novel — a story about a generation of young people fighting to save their virtual reality escape from the corrupting influence of corporate control — has earned mixed reviews for its dubious vision of a nostalgia-focused future. The Oasis, the digital fantasyland into which an apathetic populace has withdrawn, is strangely preoccupied with the 1980s, the pop culture of its author's youth, and we're asked to believe that Planet Earth in 2045 has stopped dreaming up ideas of its own, everyone preferring to play with their grandfathers' action figures.

Such a premise would suggest a meaningful story arc: Rebel! Let's break free from this cultural paralysis! Remember the words of Bob Dylan: "Nostalgia is death." Let's be creators again, making something new, imitating not the surface of those inventions, but carrying on the work of soulful imaginations from which such influential ideas came! And let's engage as human beings, face to face, again... instead of settling for a community of fake, disembodied identities bent on wish fulfillment.

But that's not where Ready Player One goes.

For all of the energy its characters expend fighting "the Man," they're ultimately opting for the Illusion over the Real, the sentimental over the sincere, the derivative and synthesized over the original and human. This is a movie for those who listen to U2's "Even Better Than the Real Thing" and miss the irony. And when human beings start dying in the real world — specifically, people related to the hero! — the movie and its characters seem eager to overlook such serious consequences, as if the actual damage of humanity's departure for an artificial world were just too much trouble to bother about.

To borrow a line from one of Spielberg's earlier movies, it seems like the inventors of the Oasis "were so preoccupied with whether they could, they didn't stop to think if they should." But this movie doesn't take such concerns seriously. It believes that this absorbing world of recreation is pretty fantastic, so long as our boringly good young white guy is at the controls.

*

Let's get specific.

In Ready Player One, we're introduced to an ugly and dilapidated 2045, in which the only fun to be had is found in a virtual reality game called the Oasis. The Steve-Jobs-like inventor of that multiplayer escape, James Halliday (Mark Rylance, Spielberg's favorite leading man of the 2010s), is dead. But this sad-faced Willy Wonka has, like a philosophical and despondent version of Mark Zuckerberg, lives on within the digital fantasyland that has drawn everyone — like Facebook today — into its enchantments. He haunts this world of overlapping video games and pop-culture references like Spielberg himself, clearly grateful for the adoration of generations, but also regretful and perhaps even remorseful over how his inventions have literally gone "viral" and become a false world over which corporations battle for control.

In the middle of this, a young man named Wade Watts (Tye Sheridan, trying to make something of the dullest hero the big screen has seen in some time) is proving to be the primary rival against a corporation's attempt to solve the biggest puzzle Halliday ever designed, one that promises "control of the Oasis" (whatever that means) to whomever wins this digital treasure hunt. Wade is a bored kid, living in denial of his circumstances, living in the dystopic world of "the stacks" — a sort of junkyard world in which skyscraping piles of RVs and storage units serve as condominiums for the poor. He hates his reality and wants a way out. The big Oasis game looks like a lottery he can win to become a genuine slumdog millionaire.

Watts is a simple kid: He wants a fast car, a gang of sidekicks, a dream girl, and the keys to the kingdom. And the movie, rather than challenging these self-centered fantasies, is eager to deliver them. So he drives Back to the Future's DeLorean, chases a sexy red-leather motorcyclist (from Akira of course), rounds up a standard late-80s "diversity pack" of companions, and goes up against villains who recall the tyrants of Tron, Ferris Bueller's Day Off, Raiders of the Lost Ark, and The Matrix. (The film isn't entirely 80s-focused.)

As I said earlier, this would seem, at first glance, like a story about learning to break free from the ultimately unfulfilling time-suck of online gaming, realizing the ways in which our world's digital paradises can manipulate us and exploit us, and rediscovering the more important and meaningful work of engaging with flesh-and-blood people, the natural world, and calls for justice and truth.

Nope. Ready Player One is giddily enthusiastic about its alternate universes. Nowhere is this more apparent than it is in those scenes when characters do drop their digital guises and the real world around them seems just as likely to fulfill their fantasies and serve up 80s-style action.

*

It's been a long, long time since we've seen Spielberg caught up in a state of pure inspiration. He's a much older man than the one who gave us Raiders of the Lost Ark, E.T., Jurassic Park, or even Minority Report, and he's more preoccupied with celebrating stories of American idealism, conscience, and leadership than dreaming up blockbuster entertainment. So I'm surprised that this material captured and held his attention. It requires him to design a kaleidoscopic alternate universe, a virtual-reality amusement park that serves as a crowded and chaotic homage to the adventure-movie era in which he himself was king.

Here's the good news: For surprisingly long stretches of screen time, Ready Player One is loads and loads of fun for an '80s boy like me. As big-screen amusement parks go, this is a wild ride. We're strapped into its rollercoaster and launched into a rush that rarely slows down. We move so fast, we barely have time to recognize the barrage of pop-culture references hurtling over, under, and past us. In one early sequence, our hero's online alter ego drives Back to the Future's DeLorean in the road race that must have been designed by someone who never stopped dreaming up demolition derbies for his Hot Wheels cars. In the chaos, we glimpse dozens of familiar costumes and vehicles, like an iconic red motorcycle from Akira, while King Kong gallops into the melee, smashing everything in sight.

The action is dizzying, overcrowded, and relentlessly loud, but if you have the strength to pay attention, you'll see a lot of cleverness that could only come from the choreographer of the Indiana Jones movies. This movie would be a lesser thing if it had been made by anybody else. Somewhere within America's most distinguished living chronicler of historical dramas lives that girl-crazy teenager who couldn't wait to send a bullwhip-slinging hero on horseback in pursuit of a Nazi tank.

And he clearly hasn't outgrown his adolescent impulses when it comes to stories for boys. One of Ready Player One's most endearing — and groan-worthy — aspects is how it plays as an allegory about a teenage boy mustering the guts to kiss a girl. The movie makes so, so much of its hero's infatuation with one of his online rivals that when he finally does lock lips with her, it can only seem anticlimactic. But that is soon followed by a scene involving an awkward attempt to fit a key successfully into a keyhole, and... okay, I'll stop there. Suffice it to say that this movie will speak more powerfully to boys who are anxious about their first time than it will to a generation worried about the soul-sucking nature of virtual reality.

But that's the problem: This is supposed to be a movie about kids who escape the hardships of the real world by dreaming their way through wish-fulfillment fantasies. It even goes so far as to confront him with the possibility that Art3mis (Olivia Cooke), the tough-talking female in skin-tight leather who has won his fantasizing heart, might actually be, in the real world, some overweight nerd living in his parents' basement. But no — this movie doesn't have the courage of its convictions: When he finds her, she's as predictably and generically attractive as most 80s-movie trophy girls, reinforcing the fantasy and dismissing any actual questions about authenticity.

Even the movie's most underlined attempt at "relevance" ends up feeling like a cop-out. How can you make a movie that genuinely challenges us to consider the corrupting influence of corporate control over art and imagination when the movie you've made is bursting with evidence of expensive mergers and franchise ownership? After Sorrento the villain is mocked, foiled, and shamed, you can sense something more menacing at work in all that the end-credits of this movie suggest.

That's why Ready Player One ultimately feels like a cop-out: Its idea of the "real world" is as much of an '80s-style entertainment as its digital escapes, and thus it has no integrity on matters of meaningfulness.

*

It's hard to know how much to praise the cast here, since we see more of their avatars than we do of the actors themselves.

I can't help but feel a bit sad that Tye Sheridan — adorable in Malick's The Tree of Life, and promising in David Lowery's Mud — would get his biggest "break" in a role that leaves him upstaged by Parzival, his digital stand-in who looks like a young, anime equivalent of Labyrinth's David "Goblin King" Bowie. Olivia Cooke wins the Ideal 80s White Girl role, and she's engaging enough in a maddeningly undeveloped character who happily consents to being Parzival's trophy before it's over.

It's ironic that the actor demonstrating the most human idiosyncrasies here is the scowling and sneering Ben Mendelsohn as the villain. Playing the heartless businessman who would rule the Oasis, Mendelsohn has the most interesting face in the film, both in the "real world" and as an avatar who resembles a steroidal suit-and-tie mash-up of Superman and Jon Hamm.

Contributing to the film's inability to separate "the real world" from the digital one is the fact that Wade's team of sidekicks is such a predictable — and predictably feeble — nod in the direction of diversity. The roles are played by Lena Waithe (who reminds us of a young Leslie Jones so much that you kind of wish they'd just cast Leslie Jones), Philip Zhao (whose character name, "Sho," seems like a deliberate reference to Short Round, a Spielberg character I'd rather not celebrate), and Win Morisaki (who, playing Daito, the token Japanese character, has an avatar named, of course, Toshiro). These actors are given little (almost nothing) to do.

The movie does a fine enough job concocting crises and adventures that follow the formulas of Lucas/Spielberg adventures. It's engaging enough, and the effects are never less than awe-inspiring. And one sequence involving some digital trickery that returns us to one of cinema's most familiar environments represents a first in adventure moviemaking. But then it has to find a way to end. And that's when it is revealed that this movie can only end up being disingenuous. For a story that would ideally be about shaking ourselves free of the debilitating spell cast on us by the option of alternate realities, this one can't bring itself to push back against that with conviction, and ends up with a half-hearted endorsement of "Engaging with realty... at least a couple of days a week." Whoa, there, Spielberg... that's a tall order!

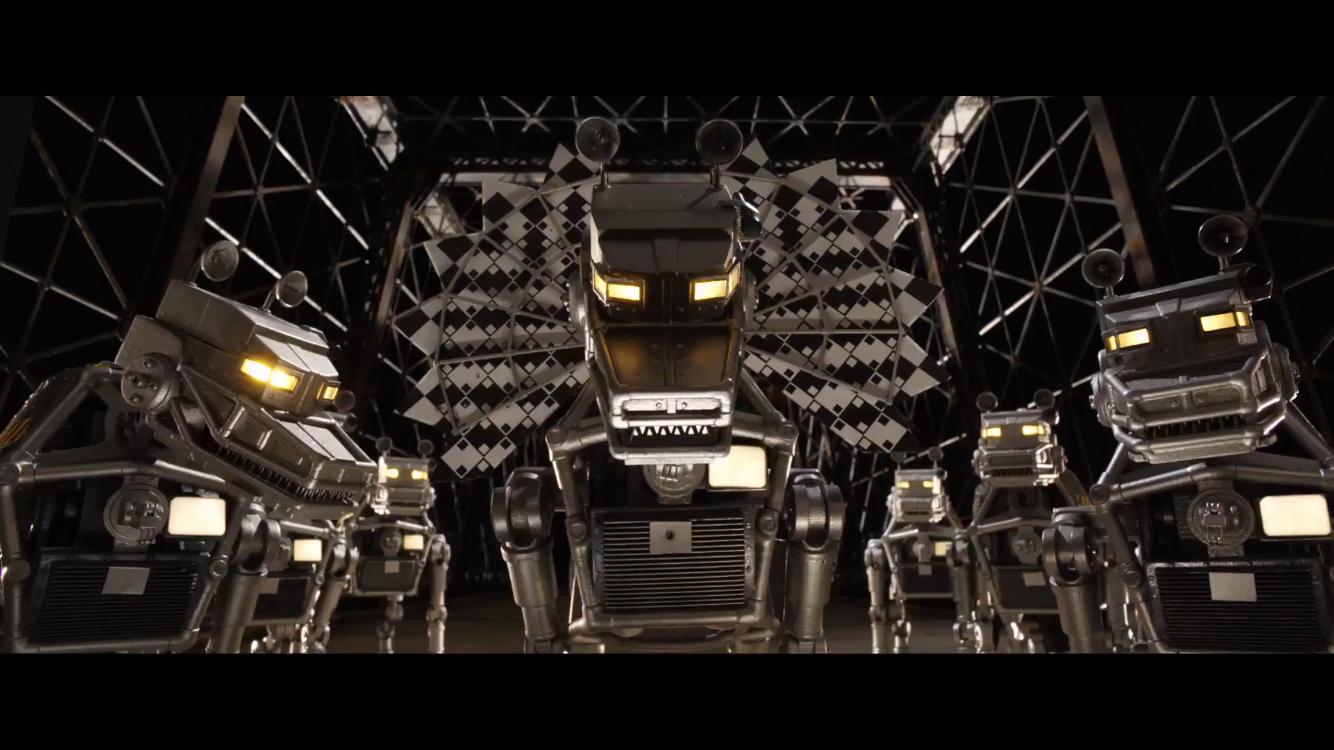

I'm avoiding spoilers here, partly because there really aren't any. This is basically a thousand interconnected video games running all at once, video games that have all of the stuff of '80s movies, but none of the soul. (It's weird that The Iron Giant figures so prominently in this movie, considering it's not an '80s thing.) The movies being celebrated here often had much more substantial characters than this movie does. They also often had much more substantial human stories at their hearts. The last time I checked on the Iron Giant, he was declaring, once and for all, that he did not exist to be a weapon. This Iron Giant, well-intentioned as he might be, is present to fight.

While there are a few action sequences that spark with that good-old-fashioned Spielberg inventiveness (the big car races that figure heavily in the trailer have some moments of pure genius), the scenes that dare to reach for real emotion and (worse) real lessons have all of the weight of the Hook finale.

The person having the most fun here is Alan Silvestri — yes, Spielberg has turned to someone other than John Williams for his score! But there's a reason for that: It wouldn't do much good to ask Williams to spoof himself, so Silvestri whips up the biggest musical mashup since Ewan McGregor and Nicole Kidman sang all the world's top pop love songs in one crazy Moulin Rouge medley. You'll recognize derivative motifs from a dozen movies. Most notably, whenever a bearded old wizard hands a treasure to his young hero — like Spielberg ceremoniously handing the keys of his kingdom to generations who actually seized them decades ago — the melody is just a couple of notes different from the one that played when a Knight of the Round Table surrendered the Holy Grail to Indiana Jones.

But in this case, the Grail is just a video game prize, and one that represents money. I guess that makes sense in a movie that reduces everything to points on a scoreboard.

In Rogue One: A Star Wars Story, somebody shouted "Save the Rebellion! Save the dream!" Unimaginative, but I cared. The rallying cry here might as well be "Save gaming from corporate control!" And how can that feel inspiring in a product as obviously corporate as this? When the game's avatars lose a round and implode, they dissolve into a clatter of golden currency. I swear I heard that sound when the movie itself imploded, in those final minutes, in a shower of noble sentimentality.

Still, it's fun while it lasts. And considering how much more aesthetically engaging this is than almost anything else in theatres right now, well... might as well jump.

Praising Paul, Apostle of Christ

In The Los Angeles Times, Justin Chang makes clear his Christian faith while also making clear that the conversation about "Christian movies" is focusing on the wrong movies.

After all, movies that earnestly engage with the questions and ideas at the core of the Gospel (Chang mentions Last Days in the Desert and Silence as good examples) tend to be overlooked by Christian audiences, while those that are propagandistic and popular with evangelicals are those that misrepresent Jesus's own teachings.

Describing contemporary Christian movies, Chang writes,

My reservations have little to do with standard criticisms like awkward performances or clunky production values — venial sins, surely, for new filmmakers trying to find their way. What rankles about a cinematic sermon like “Letters to God” or a morally offensive wartime drama like “Little Boy” isn’t the mediocrity of the craft; it’s the calculation inherent in the enterprise. There’s a smug complacency with which these movies preach a message ostensibly meant to set the world passionately ablaze.

I didn’t check all these prejudices at the door when I recently caught up with “I Can Only Imagine,” “Paul, Apostle of Christ” and “God’s Not Dead: A Light in Darkness,” the three highest-profile Christian-themed releases of the spring moviegoing season. But I watched all of them in a tentative spirit of optimism, intending to gauge the present state of what I have often hesitated to describe as art, and hoping to be pleasantly surprised. And at least two films in this cinematic trinity largely succeeded in overcoming my inner skeptic.

He goes on to explore the strengths and weaknesses of the three films, expressing admiration for how Paul, Apostle of Christ avoids the common failures of so-called "Christian movies."

How much value are we willing to ascribe to a work of art simply because it aligns with our beliefs? And how much can we trust our tears? Any honest believer who has sat through a worship service has certainly asked whether they are hearing the authentic voice of God or simply being emotionally manipulated by the music — and then proceeded to wonder if the two might not, somehow, be one and the same.

I certainly can’t say whether the swells of emotion I felt while watching “Paul, Apostle of Christ” are attributable to the Holy Spirit or simply a competent level of artistry by all involved, and I’m not terribly interested in parsing the difference. By far the most intelligent, absorbing and stirring of these three movies, writer-director Andrew Hyatt’s well-acted drama of imprisonment and martyrdom implicitly rebukes the “God’s Not Dead” franchise by reminding us what actual persecution looks like. It returns us to a vision of ancient Rome (the film was shot on location in Malta) where some of Christ’s earliest followers were routinely burned alive in the streets or condemned to death in the arena.

Similarly, Steven D. Greydanus at The National Catholic Register finds much to admire in Paul, Apostle of Christ:

Shot on a budget and a tight schedule in Malta (where Gladiator and Troy, and more recently Risen, were shot), Paul, Apostle of Christ is remarkably authentic-looking. The screenplay is intelligent and thoughtful, with only occasional missteps, ranging from an occasional poorly chosen phrase (like Luke’s “thoughts and prayers”) to a late moment in which a character who has suffered a trauma more dangerous than Paul’s floggings is up and about far too quickly.

But then he points to the potential for the film to be misunderstood and embraced for the wrong reasons:

Paul, Apostle of Christ is dedicated to all who have been persecuted for their faith. This potentially raises a sticky point.

...

In our day, global persecution notwithstanding, American Christians are generally far less aggrieved than many of us are inclined to think. It’s easy to imagine many comfortable viewers watching Paul, Apostle of Christ as if it were not only a story of our heritage, and one that resonates with the experiences of suffering souls around the world, but a mirror of our own experience.

On the other hand, the film’s clear repudiation of violence in the name of Christ, its repudiation of efforts to seize the reins of power by any means necessary, and its theme of seeing enemies as human beings are especially welcome today. Sometimes in the effort to resist evil one risks becoming what one opposes, or worse. Paul, Apostle of Christ suggests that it’s always better to suffer evil than to be brought to its level in resisting it.

Movie's Not Christian — and Vox's Not Dead

How great is it that Alissa Wilkinson, making her own Christian faith clear, has the opportunity at Vox to expose how the the God's Not Dead trilogy is misrepresenting the Gospel?

It's easy, after all, to point out how awful these movies really are. But to do so while highlighting the betrayals of Christianity inherent in these films is, ultimately, a better form of Christian witness than almost all so-called "Christian movies."

Christians ... are supposed to be people who follow the teachings of Jesus, who instructed his followers to practice a fairly extreme form of not fighting back, instead turning the other cheek to someone who slaps you and giving your shirt to the person who sues you for your cloak.

...

The goal, in the end of each of the films, is to win — whether it’s vanquishing a foe in a classroom, winning a court case, or gaining the higher ground and being the de facto winner in the court of public opinion.

The greatest offense of the God’s Not Dead series may be its failure to imagine for its audience what a truly radical belief in a living God would look like. The movies, crippled by their own narcissistic inward turn, prove their imagination is far, far too small.

Isle of Dogs (2018)

It might be the devil, or it might be the Lord,

But you're gonna have to serve somebody....

Thus singeth Bob Dylan. And thus showeth director Wes Anderson in his latest film Isle of Dogs.

Any dog lover knows the particular and purposeful joy that dogs seem to take in serving their masters. So it's easy to feel the burden of the protagonists in this extravagantly animated film. Yes, the main characters here are canines who, suffering from an epidemic of Dog Flu, have been deported from the fictional Japanese City of Megasaki to the living hellscape of Trash Island, sometime in the not-so-distant future.

The particular gang of dogs at the center of our story includes Chief (Bryan Cranston), a gruff loner who reluctantly ranges about with the talkative and disgruntled Rex (Edward Norton), the rumor-spreading Duke (Jeff Goldblum), Boss (Bill Murray), and King (Bob Balaban). They're a pack of self-proclaimed "indestructible alpha dogs" who spend their days searching for garbage good enough to sustain them; fighting over that limited supply with other snarling packs; and sneezing their way through one melancholy, master-less day after another.

It's hard to see how they stand a chance of escaping; how they'll quell the mass hysteria of the Japanese people who, brainwashed by anti-dog propaganda, have turned against them; how they'll overcome the campaign against them led by Mayor Kobayashi, a fearmongering tyrant; or how they'll expose the conspiracies that have silenced scientists and suppressed the efforts of dog-loving truth-tellers back home.

But where there's longing there's hope: Rex's determination to find a better life keeps the eyes of his pack brothers open for opportunities. They're sick of their trash-heavy diet — I'm sure that you, browsing your streaming video options, can relate — and eager to find something better than this half-life.

Enter Atari, a young Japanese orphan. Yes, this is a Wes Anderson movie, after all. So it's going to be about a child (or a man-child) striving to make a life in the shadow of an overbearing parent or authority figure. Just as the children in Moonrise Kingdom fled from their irresponsible parents in search of love, Atari (voiced by Koyu Rankin) has run from the seemingly heartless uncle who adopted him — Mayor Kobayashi, of course. He's stolen a plane in order to search for his one true friend and confidant: his deported dog, Spots.

And, sure enough, he's crashed on Trash Island right in front of Rex's pack.

Yearning for a master, Rex and company are immediately drawn to Atari and inclined to help him search.

But Chief stays at the edges of the scene, grumbling, refusing to risk spoiling his illusion of self-sufficiency by making himself obedient to any master. He makes his philosophy clear in three words: "I don't sit."

This would seem like a clear, straightforward, honorable theme, one sturdy enough to serve as the heart of a good story. But Isle of Dogs — a story that Anderson imagined with help from Roman Coppola, Jason Schwarzman, and Japanese actor and writer Kunichi Nomura — is his most complex and ambitious narrative.

The drama of the search for Spots is set in a strangely complicated context, a culture that seems drawn more from popular Japanese movies than from Japan itself. It's a Japan of magical realism, as fanciful — perhaps more so — than the completely imaginary Republic of Zubrowka in The Grand Budapest Hotel. There's a cruel overlord, a brainwashed people, an endangered company of truth-seeking scientists, and an uprising of conscientious children. You might sense some obvious overlaps with conflicts currently making headlines, like those involving egomaniacal authoritarian leaders; the deportation of innocents who have been misrepresented as threats; persecuted scholars and suppressed studies that might save lives; and passionate young idealists speaking truth to power.

But the film never seems preachy or self-consciously relevant. It's too caught up in the complexities of its foreign context, its frequent allusions to classic cinema, and its unlikely literary mash-ups. The influence of Akira Kurosawa is obvious, but I see an even stronger influence. Anderson has gone on the record as a big fan of Richard Adams's Watership Down, and Isle of Dogs resembles nothing more than the plot of another difficult and heartsickening Adams epic: The Plague Dogs.

Unfortunately, while this choice to set his futuristic fantasy in some kind of pop-culture distillation of Japan enables Anderson to weave elaborately ornate animated tapestries, pepper his screenplay with poignant haikus, and send composer Alexandre Desplat into a fever of taiko rhythms, it also finds him indulging ideas and images that are provoking cries of cultural insensitivity.

I admit, I flinched when the dogs chuckled in excitement at the sight of a billowing cloud of smoke over an explosion in this Japanese environment. And while it's clearly meant to be amusing that Japanese characters have names drawn from Japanese pop culture — specifically from things that American audiences will recognize — the heroic dogs have inexplicably American names. (Justin Chang and Jen Yamato, in The Los Angeles Times, have described this problem more eloquently, and in greater detail.)

How does this story about Japanese tyranny, propaganda, and misinformation relate to the central storyline about dogs and masters, or about the difference between blind servitude and freewill?

Perhaps we're to consider the fact that Mayor Kobayashi is being "mastered" by his fears and his vanity. Perhaps we're to see the consequences of blind loyalty to a fallible master as the hound-haters of Megasaki are brainwashed into hysteria.

I'm not sure yet.

I suspect that, whatever the storytellers were thinking in weaving these plot threads into such an elaborate tapestry, Isle of Dogs is best interpreted as a story about the importance of willful service for the greater good. Anderson, whose stories always draw us into the tension between maverick independence and community service, wants his animals to remain gloriously untamed, but he also knows the necessity of compromise and cooperation.

Thus, the only step that the obstinate Chief can take toward fulfillment is a step toward the lonely, injured boy who has come to Trash Island, thrown a stick, and commanded him to fetch it. Only by consenting to serve someone good will Chief find purpose and relief. But he will have to reckon with his own knee-jerk reaction to trouble: his tendency to bite.

In that sense, I suppose, Isle of Dogs has something in common with the most recent movie from that other Anderson: Phantom Thread. That, too, is a story of a delusional ego who, fancying himself as independent and insulating himself against the dangers of relationship, makes himself and everyone around him miserable. Only through an inconvenient commitment — in Phantom Thread, love and marriage — can the hero escape his self-inflicted imprisonment.

And Chief isn't the only one who needs change. As with all Anderson films, there's a patriarchal giant who, while intolerably insensitive, might not yet have strayed beyond redemption. Mayor Kobayashi himself will have to recover a conscience or suffer the violence of a rising revolution. Only by seeking a cure for the Dog Flu, rather than merely banishing the sick, can Kobayashi help the Japanese Archipelago, which is by its very definition a scattered society, reconcile its fractured body.

*

I write all of this with admiration for Anderson's narrative ambitions, awe for his aesthetic achievements (Isle of Dogs is his most intricately detailed and luminous film), and love for his boundless imagination.

But I also write in a state of agitation and frustration.

Isle of Dogs, while it represents a new high in Wes Anderson's visual pageantry, was also for me, in my first viewing, the least affecting Wes Anderson narrative. I felt that I was looking at the movie instead of feeling myself drawn in. As I tried to get my bearings in this fictional foreign context, seeking an answer for the question "Why Japan?", I remained distracted and perplexed. While I could identify the contours of the narrative's themes and trace the arc of Chief's story, I never felt drawn into its characters' personal conflicts the way I was drawn in so powerfully to the conflicts at the heart of Anderson's previous films (most especially The Royal Tenenbaums, Fantastic Mr. Fox, and Moonrise Kingdom).

But I know better than to blame Anderson or his movie. While I might suspect, at this point, that Isle of Dogs is taking on too much storytelling for its running time, and giving insufficient attention to its many characters, I must also admit that I felt somewhat detached in my first encounters with The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou and The Grand Budapest Hotel, two films that I have grown to love, films that eventually — on my second or third viewing — moved me deeply, even to tears.

Also, I'm not really a dog person. Perhaps my failure to feel firm tugs on my heart-leash has to do with the fact that I'm partial to different kinds of pets — cats, for example (who have very good reasons to file grievances against these storytellers).

Like Chief, I'm slow to pledge allegiance to a filmmaker. Contemporary American directors who have proven consistently trustworthy are few. But Anderson is one of those I faithfully follow around the Trash Island of the cineplex. It isn't blind obedience that sends me fetching every stick he throws — rather, it's the fact that every time I do, I find myself eventually rewarded with more than just a snack. Anderson doesn't do treats — he serves full meals.

I may not be enthusiastic about this particular meal just yet, but I suspect that I will, after two or three rounds with it, catch on to the game that Anderson's playing. He's a good master... of his art.

And when I get a chance to see Isle of Dogs playing on a big screen again, I will be happy to sit.

*

This review is made possible by the Looking Closer Specialists,

whose support for this website keeps me going to the movies

while I strive to earn a living as an adjunct professor.

If you enjoyed this review, consider making a small donation to my work.

An American who deserves a parade

Today, we celebrate the 90th birthday of an exemplary American — one who knew the secret to making America, or any neighborhood in the world, great.

We need him now. We need to be more like him — now.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FhwktRDG_aQ

The Decemberists record the a-pop-alypse

Just four years ago, America was singing Tegan and Sara's pop anthem "Everything is Awesome." Sure, the audience was in on the singers' joke. In its satirical context — The LEGO Movie — the song was thick with irony: It highlighted the protagonist's blissful ignorance about his culture of conformity. And we sang along with our tongues planted firmly in our cheeks (which is easier than it sounds).

And yet, there was no denying that the song's unbridled enthusiasm and power-pop punch was ultimately spirit-lifting. Many of us actually liked the song for how the positivity of its music flew in the face of so much aural ugliness. Kids loved it, and parents felt like kids when they joined the chorus — at least until the song wore out its welcome. And the movie, for all of its sophisticated satire, was worth revisiting for, above all, its flamboyant celebration of creativity. A massive corporate blockbuster, hyper-marketed for maximum dollars, The LEGO Movie became one of the year's most vital works of anti-establishment art. You know... for kids!

It appears that the Decemberists, whether they know it or not, were influenced by this.

Colin Meloy and his band of kindred storytellers have made an impressive career out of dark, depressing concept albums about doomed lovers, doomed sailors... anybody doomed, really. Good luck classifying their sound: They've famously fused folk, alt rock, prog rock, stage musicals, country, and more. And it makes sense that they would throw a saddle on 2018, this ticking time-bomb of a year, and ride it Slim Pickens-style down toward a seemingly inevitable American apocalypse with a song called... I am not making this up... "Everything is Awful."

And, God bless them, they've kindled some of the same contagious energy that made me sing that LEGO Movie song a few too many times. For all of its straightforward declarations of trouble, the song kindles a rock-and-roll joy that acts as an antidote to the song's central claim. I haven't had this much fun singing about cultural decline since R.E.M. sang "Stand" or "Shiny Happy People."

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wLUegZFZWq8

In fact, the whole record — I'll Be Your Girl — has this effect on me.

Perhaps it'll play like nostalgia for you. These sounds do see piped from some deep reservoir of late '80s and early '90s synth-pop. Besides R.E.M., I'm hearing early They Might Be Giants and other Sgt. Pepper-y parties like, well, World Party.