A Star is Born (2018)

Rocket Raccoon has a reputation as the Guardian of the Galaxy who machine-guns equal measures of bullets and bad language. In that sense, he's like a fusion of two more characters played by Bradley Cooper: He's a gunner like American Sniper's Chris Kyle and he's a snarling cuss monster like, well, the latest Cooper character — Jackson Maine in the latest remake of A Star is Born.

And that comes as a surprise.

I walked into what I believed to be a sort of prestige picture, a remake of a melodramatic musical so classic that it can be rightfully credited with establishing certain silver-screen cliches, and I was ready for it to feel formulaic. I was also prepared for this to feel like the coronation of Lady Gaga as a Grade-A movie star: As Ally, a made-to-order pop starlet, she's playing a role far less distinctive than the one she actually inhabits in today's musical cast of characters.

But I wasn't prepared for this to feel more like a Bradley Cooper vanity project — one in which he orchestrates every gaze — from the camera's adoringly upturned angles to the hero-worship wetness of the leading lady's eyes — in a clear attempt to announce himself as The Sexiest Man Alive.

Add to that the bizarro-choice of replacing his voice with a Sam Elliott impression so overbearing that I found myself straining to endure. But we'll get back to that later.

You don't need a plot synopsis from me on this film: You already know it's a rags-to-riches story of a down-on-her-luck Ordinary Girl who works as an [Insert Difficult Job She Can Flamboyantly Quit] and who still lives with her dad. You already know she'll be discovered in an unlikely [Insert Sexy Meet-Cute Here] by a Drug-Addicted Superstar. You know they'll have the slo-mo Love-at-First-Sight necessary for us to want his worldly success to save her... and her conscience to save him.

You can sense it coming if you haven't seen the trailer: the glorious moment when he thrusts her into the spotlight and the world loses its mind in the first flush of her irrepressible onstage passion. You can just as easily sense the trouble coming: If the extreme close-ups of Jackson Maine taking drugs, Jackson Maine taking swigs, Jackson Maine taking more drugs, Jackson Maine drinking everything in sight don't tell you what's coming, neither would reading a Wikipedia synopsis before the movie.

To be fair, Cooper the Director has put together a convincing-enough world of arena-rock shows, big audiences that worship his character, backstage road-crew expertise (featuring a Designed-for-Oscar Supporting Role for an almost-always-crying Sam Elliott), and flashy imitations of the Grammies and Saturday Night Live that complete his representation of the "Riches" after the rags.

But the inevitability of Cooper's storytelling is amplified by the haste with which he moves through its pop-song routine. After the first 45 minutes that do a halfway-decent job of developing Ally's character as a spirited singer who's as likely to throw the first punch in a barfight as she is to confess her insecurities about her looks to a drunken Casanova on their first grocery-store date, Cooper leaps from one All Caps Scene to another. It's like we're watching a lengthy, spoiler-packed trailer of a longer movie's major moments: the Big Rock Numbers, the Substance Abuse, the collaboration montages, the Bathtub Intimacy, the Jealousy of the Success Story He's Launched, the Further Substance Abuse, and the Pending Crisis. I haven't seen the original or the other remakes, but this sure doesn't make that prospect palatable. (I can only hope that earlier versions don't have this Edited for ADD pace.)

Melodrama, as a genre, eschews subtlety. But the way some of these scenes play big basic chords as if they've just invented them, it feels like watching a great pianist try to hit the highs of a Chopin piano concerto on a five-button Baby's First Keyboard. That big scene set at the Grammies, which may as well have a chapter title "Calamity!", is downright embarrassing — and not in the way it intends to be. ("Far from the shallow," my eyebrows.)

And all along the way, Cooper carpet-bombs his scenes with f-bombs as if it's possible to cuss your way to an Oscar. The aggravation of this is exacerbated by the Rock God posturing, the fake accent, and the generic early-'90s Seattle rock vocals. I mean, come on, Cooper: As an actor you can be pretty good... but Eddie is Vedder.

As a result, Cooper is to this movie what Jack is to Ally's career: He's the thing that makes the beginning possible and the thing that nearly spoils everything for her. She's too good for him. She's too good for this movie.

It might be worth some chuckles to see a supercut of Cooper's curses from A Star is Born re-dubbed with an impression of his Rocket Raccoon voice. Outside of that, I doubt I can stomach revisiting anything from this movie.

But judging from the sniffles I heard all around me during the steroidal moments of angst and crisis, A Star is Born might be just the kind of Super-Sized Escapism that could win an Oscar. Maybe in these times of unfathomable violence and destruction in the world around us, moviegoers are so desperate for escapism that they need heavier doses of the same old illusions. Maybe they need to believe, if only for 145 minutes, that what matters most are the sufferings of a white male celebrity who can't properly enjoy his success, and a pop goddess whose rise to glory is interrupted by harsh realization that alcoholics make terrible boyfriends.

To steal a line from the movie: Lady Gaga, "it wasn't your fault." You're a star. No argument there.

Join me for two special screenings of Prospect in Seattle

Here’s your chance to meet filmmakers Christopher Caldwell and Zeek Earl, the makers of the new science-fiction thriller Prospect.

Caldwell and Earl (Seattle Pacific University graduates in 2009 and 2010) have earned extraordinary opportunities in making high-profile commercials and acclaimed short films under the banner of their commercial production company, Shep Films. I wrote about these two for SPU back in 2013. But I'd been following their pursuit of filmmaking success long before that, acting as an advisor for Earl was writing a screenplay as an English major.

Their first feature film, Prospect, opens in theaters in November. They will make special appearances at two of those opening-weekend screenings in Seattle, and they’ve invited me to host an interview and Q&A after the movie.

We’re hoping to see SPU moviegoers — faculty, staff, and students — in the audience to enjoy the movie, ask questions, and cheer them on.

Join me either Thursday, November 8, at 6:45 p.m., or Friday, November 9, at 7:30 p.m., at Regal Meridian 16 Cinemas downtown.

Puzzle (2018)

As Puzzle begins, we see Agnes vacuuming her house. She looks as dull and as dimly lit and as dusty as the house she's vacuuming.

This is how you might expect a movie to begin if it's going to be about the drudgery of being a neglected housewife. You might also anticipate a great deal of what's ahead. You'll brace yourself for scenes of domestic tensions; of a belligerent husband; of a concerned friend raising questions that Agnes brushes off in her fear, shame, and humility; of Agnes resisting temptations to pursue something—or someone—representing her own desires and potential.

The fact that I'd heard the premise — "This is the story of a neglected housewife who discovers a passion for jigsaw puzzles and secretly slips away to pursue competitive puzzling" — did not help matters. I was ready for a whole lot of "been there, done that":

- the woman's secretive training behind the backs of her disapproving husband and children;

- the conventional development of a Mr. Miyagi/Karate Kid relationship with a genius;

- a training-for-competition montage;

- her family's inevitable discovery of her secret life and passion;

- a sudden turn that threatens her ability to participate in the competition;

- a joyful rush when she finally breaks free of her family, or when they finally come around to supporting her, and she gets to compete anyway; and, of course,

- the suspenseful (but inevitable) tournament victory.

And, of course, the 'Plain Jane' appearance of our hero would dissolve so that she looks like a glamorous celebrity at the end — thank God!

I admit that I smelled these maddening cliches right away. These are tried-and-true crowdpleasing paces, but I've seen too many movies to find them interesting anymore. I started fast-forwarding through the movie in my mind.

But, fortunately, I was sitting in a theater and did not have a remote in my hand.

Puzzle may begin in a way that feels familiar and formulaic. And it does, in fact, include some of those unsurprising turns. But it is a much, much more rewarding experience than I expected.

Heed this warning: Avoid the trailer at all costs. I can think of few previews that spoil more of a movie's important turns than this one. Suffice it to say that, after that worrying start, almost every scene of Puzzle comes alive with small pleasures, big surprises, and exquisite subtleties of storytelling, performance, and cinematography.

Much of the credit is due, I suspect, to the writers.

IMDB lists Puzzle as Polly Mann's first screenplay, but her co-writer Oren Moverman worked on such outstanding indie hits as Love & Mercy, The Messenger, and I'm Not There (with Todd Haynes). They've made Agnes and her jigsaw-genius mentor Robert into nuanced, believable, and complicated characters.

Perhaps most importantly, they've made her husband Louie into someone who is simultaneously overbearing, loving, naive, sympathetic, and frightening. It should have been easy to cheer for Agnes and to root for her to abandon her horrible husband for a romance with someone who really sees her. But Puzzle is not that movie. Mann and Overman chart a course that risks alienating the audience by committing to the complex humanity of its characters, and by refusing to support the lie that difficult marriages can be happily and blissfully abandoned.

That's just one of the ways that Mann and Overment cleverly avoid the pitfalls of genre cliches. Most impressively, they devote very little time at all to puzzle competition events. Yes, we're on our way toward heated puzzle matches. But get this: Agnes has no rival. We're not given a villain to root against. In fact, we don't even witness any culmination to an edge-of-your-seat championship round!

Instead, the film focuses on a tangle of messy relationships. I believe in Agnes, Louie, and their two sons—one of whom is escaping by way of college, the other hanging around home with clear eyes and, yes, a big heart. This family, flawed as it is, is a loving family. They disappoint each other. They give each other second and third chances. And they soldier on as a family even after explosive clashes. What a rare and marvelous thing to witness.

Don't overlook the film's treatment of the family's faith, either. Louie and Agnes are Catholics, and that becomes an influential factor in Agnes's moral struggles when her husband takes a harsh stand between her and meaningful engagement with the world beyond housework. Is her faith an avenue of freedom and salvation, or is it just one more cultural pressure restricting her to frustration?

Even more impressive, the film refuses to give the audience a clear conclusion of tragedy or triumph. It arrives at a messy but meaningful conclusion that is open to interpretation. For me, this was even more satisfying and thrilling than the summer's stunt-driven Mission: Impossible movie.

I also commend cinematographer Christopher Norr, who filmed Scott Derrickson's masterful horror film Sinister, for infusing this film in sumptuous color and light. While it's a script-based film, with most scenes being filmed matter-of-factly, it offers moments I wanted to live in for a while, radiant in ways that reminded me of Kieslowski's Three Colors trilogy.

But I must, above all, celebrate what Puzzle's three leads achieve: an exquisite, discomforting, and fully human chemistry. As Agnes, Kelly Macdonald—an actress I would happily watch on a far more regular basis, worthy to be remembered for so much more than No Country for Old Men, Brave, and Gosford Park—shines in the lead. Her face is a powerfully expressive text conveying complicated emotions and thoughts, and representing hairpin turns of understanding and decision that are always convincing.

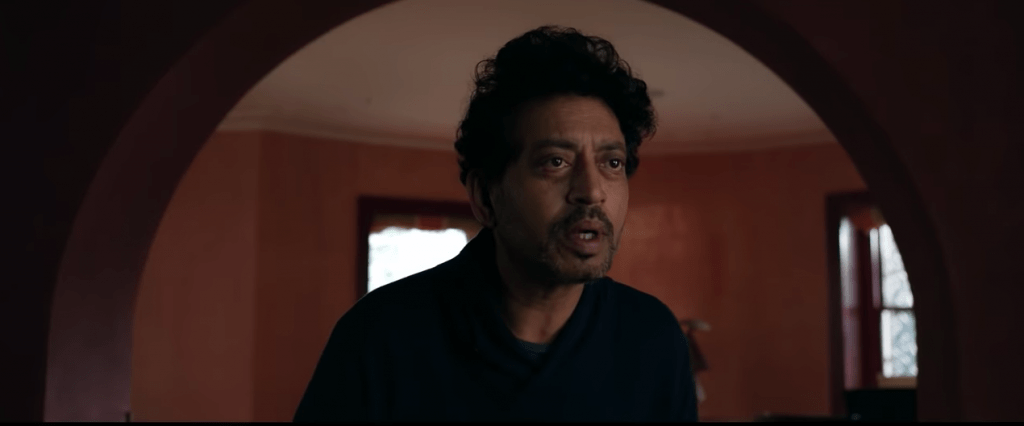

Irfan Khan (The Namesake, The Darjeeling Limited)—an actor who deserves so much more praise and glory than American audiences give him—turns unremarkable lines into surprising moments. I'd call this Oscar-worthy work in a supporting role.

David Denham has, in some respects, the most difficult job here. I've only known him as Pam's aggravating boyfriend on The Office, but he makes Louie one of the most memorable big-screen fathers and husbands I've seen in recent years. Late in the film, I found myself rooting for him to make the right movies, change his heart, and redeem himself from past mistakes.

Puzzle, directed by Mark Turtletaub (a producer on that indie landmark Little Miss Sunshine), brings so many three-dimensional pieces together into a small, substantial, and intricate surprise — one that has stayed with me since I got more than I bargained for on an occasion of spur-of-the-moment, late-night moviegoing. (It makes me curious about Rompecabezas, the 2010 Argentine movie on which this film is based.)

So if you're worried about being bored by a movie about jigsaw puzzles, or weary of films about the living hells experienced by housewives — I mean, come on, I know so many extraordinary stay-at-home moms who live rich and rewarding lives — let me encourage you to give Puzzle a try anyway.

I almost heeded my concerns and skipped it. And I'm so glad I didn't.

Dead Poets Society and the Legacy of Dr. Luke Reinsma

Today, I walked down the English Department corridor at Seattle Pacific University and saw something that stunned me.

I saw a friend of mine, a recent graduate of SPU's MFA in Creative Writing program, settling into his new office. For most people, this would have been an unremarkable sight: a professor at work. But it startled me, and not for the first time. I was expecting — and will, for a long time to come, go on expecting — to see someone else beyond that door. I thought I'd see Dr. Luke Reinsma, a legend of SPU's English program, surrounded by his books, his feet up on his desktop, the Oxford English Dictionary open in his lap. It's a sight I've seen frequently over almost 30 years of experience at this university. It means a lot to me, as Reinsma is one of the most influential figures in my history.

Here's the thing: I've had time to get over this. Reinsma announced his retirement a few years ago. And I wrote an essay celebrating his legacy back then, before he found ways to keep one foot in the work of teaching by covering some adjunct courses here and there.

But now that his bookshelves are gone and someone else is setting up shop, I feel it's time to re-post this: an article I wrote for Christianity Today. At the time, CT's entertainment editor Alissa Wilkinson had asked me to write about a movie that I'd changed my mind about. I thought of Dead Poets Society. And then I realized it was a chance to write about my favorite professor.

Here's what I wrote, what Christianity Today published, four years ago this week.

He’s leaving. I can hardly believe it. Dr. Luke Reinsma, professor of English at Seattle Pacific University, is retiring.

Two weeks ago I revisited Peter Weir’s Dead Poets Society for the first time in twenty years. Watching Robin Williams play that charismatic English teacher who transforms the lives of repressed prep-school boys, I had flashbacks to my undergraduate years when Reinsma was my academic advisor.

As a freshman at SPU in 1989, I found that this idiosyncratic professor lived up to the reputation I’d heard from former students. I learned to love how, when he handed back my essays, he had written almost as much on them as I had written in them. An exploration of The Canterbury Tales, a coffee conversation about the origins of the Arthur legends, an independent study of Old English, a post-movie talk about Quentin Tarantino—every time we met, we dug deep into the substance of our subject.

Now, he’s boxing the books that blessed his office with an aroma of scholarship and mystery. I’ll miss his Richard Farnsworth mustache. His quick and mischievous eyes. The perpetually windblown hair that he sculpts wildly with both hands as if trying to wring out the words he needs to express his big ideas.

He changed my mind about so many things. I realize now that, due to his influence, even my perspective on Dead Poets Society has changed — dare I say matured?

The Space Between Chaos and Control

Still shaken by news of Robin Williams’ death, I knew that even his mediocre movies might now become emotional experiences. Williams was such a commanding big-screen presence that some filmmakers seemed to think that they needed nothing more than his improvisational genius to make a good movie. But his did his best work—The Fisher King, Good Will Hunting, Insomnia, Awakenings—with directors who knew when to restrain him and when to unleash his Tasmanian Devil personality.

That tension between chaos and control made him perfect for the Dead Poets role of Mr. Keating.

Set in 1959, the film focuses on the strict routines, rituals, and rigor of Welton Academy, a conservative preparatory school where young men are pressured to score highly on tests not only by headmasters and instructors but also by demanding parents. In their classrooms, in their rows, at their desks, on the clock—everything happens by the book.

Mr. Keating takes a sledgehammer to their comfort zones. The first thing he does? He gets them moving—bodily—as if education might involve more than the head. He leads them out of the classroom and coaxes them to engage mysteries.

Similarly, Dr. Reinsma led his undergraduates out from under the merciless buzz of fluorescent classroom lights into the cool of Pacific Northwest mists, up challenging trails in the Cascades, until we emerged above the clouds to study our texts on sunny mountaintops.

Keating climbs too—right up onto his desktop. And then he invites his students to follow. “Why do I stand on my desk? . . . To remind myself that we must constantly see things in a different way.”

So Reinsma had us discuss how texts challenged, unsettled, and even offended us. We learned that “love thy neighbor” means listening to experiences altogether different from our own. And he coached us to voice personal reactions, craft personal opinions, and back up personal interpretations with textual support. We were not there to receive his perspectives, but to discover our own.

Keating seeks to save spoiled, obedient boys from society’s narrow definitions of success. “Medicine, law, business, engineering—these are noble pursuits, necessary to sustain life,” he says. “But poetry, beauty, romance, love—these are what we stay alive for.” The arts, he knows, can equip young hearts with compasses of conscience and passion.

Similarly, Reinsma was (and still is) allergic to the idea that arts and literature are a garnish on the plate of academia. It pained him to see so many schools prioritizing business, science, and mathematics, as if doctors were telling him that the health of the hands and the head mattered more than the health of the blood and the heart.

You’d guess that I embraced Dead Poets Society as a personal favorite.

You’d be wrong.

Threatened by Freedom

I first saw Dead Poets Society a few weeks before I moved from Portland, Oregon, to “the Emerald City” for college. In some ways, the movie impressed me. I already dreamed of a career that allowed me to write and teach, so I applauded Mr. Keating’s passion for literature. On that, we agreed.

Moreover, the film’s young cast—Robert Sean Leonard (who would later play Watson to Hugh Laurie’s Holmes on TV’s House), Josh Charles (whose role on TV’s The Good Wife would win him a host of female fans), and Ethan Hawke (who . . . well, you know Ethan Hawke)—powerfully impressed me.

Nevertheless, I came out of Dead Poets Society grumbling. And I furrowed the brows of my fellow English majors by holding a grudge against it all through college.

At the conservative evangelical institution I attended kindergarten through high school, I had always sought to fulfill and exceed the hopes and expectations of not only my teachers but also the God in whom they had taught me to believe. That meant achieving “straight A” report cards in academics and in morality. No misbehavior, no drugs, no sex, no profanity—you know the drill. Their guidance seemed to work: In my senior year, I lived up to their hopes and graduated with honors and scholarships. Might as well have draped a “Mission Accomplished” banner in my bedroom. I was ready for the rest of my life.

Not really.

Outside of the school’s controlled environment, I was deeply insecure. I knew how to impress adults, but not my peers. Fearing the peer pressure that Friday chapel assemblies had warned me about, I was utterly terrified of unsupervised parties. I became judgmental toward (and, frankly, jealous of) classmates who enjoyed greater freedoms than I did. My imagination animated scenes of extracurricular debauchery. To escape, I lived in a self-inflicted quarantine, troubled by dark speculation about those who might be drinking, smoking, or going out on unchaperoned dates.

As I watched Dead Poets Society, Welton’s oppressive administration seemed like the Evil Empire—but Mr. Keating seemed like an equal and opposite threat. With his “Seize the day!” mantra, he seemed to shout “All things are permissible!” without the necessary caution of “But not all things are profitable!” He seemed a false Christ, granting his students a license to lust, sending them off into lives of unhinged sensualism.

It didn’t make me any more comfortable to see a character who looked like me—tall, awkward, and big-nosed—getting drunk at a party, then trying to kiss another young man’s girlfriend while she slept. (You know what really stung? His name is Overstreet.)

Watching Neil Perry—the student whose burgeoning love of the arts is crushed by his father’s condemnation of “nonsense”—become a tragic figure, I blamed Mr. Keating’s apparent disdain for parental authority. I felt he had goaded Neil to embrace drama and disrespect over discernment, and thus the boy had lost all control. Nothing short of a conversion to Christianity—I believed—could have straightened Neil out. Keating had failed to show Neil what really mattered.

And that’s where I misjudged the film so badly.

I was so preoccupied with the boys’ reckless rebellion that I missed the contrast between their sophomoric declarations of independence and their compassionate teacher’s counsel. “Sucking all the marrow out of life,” says Keating with quiet authority, “doesn’t mean choking on the bone. Sure, there’s a time for daring . . . and a time for caution. And a wise man understands which is called for.”

In sharp contrast to the boy’s controllers, Mr. Keating models a healthy balance of freedom and responsibility. He descends into that world of order, accepting the form of a servant, and makes all things new. He shows them what the imagination, taking the shape of love, makes possible.

He may not speak of Jesus. But he’s an imitation of Christ.

A Delicate Balance

Looking back at authority figures who have inspired my respect, and at those who have been driven by ego and a desire to control, I’ve come to suspect that anyone who seeks to instill character in another person by force will produce an equal and opposite reaction. Those Dead Poets boys aren’t anarchists or hedonists. They’re human beings pushing back against forces that would press them into dehumanizing molds.

Are they extreme? Immature? Petty? Sometimes. But who can blame them? Who, besides Keating, has shown them an example of wisdom and integrity?

The film’s tragic turn comes when those given authority over Neil show no respect for his imagination or sense of calling. They serve their own ends. I’d even say that Neil’s father is threatened by the possibility that his son might find more fulfillment than he, in his fearfully insulated world, will ever permit himself to know.

It’s a dangerous business—freedom. I’ve known those who, given their first glimpse of it, plunged without discernment into rash decisions, costly consequences, and never recovered. My younger self would have said, “I told you so.” Now I wonder: What (or who) inclined them to throw themselves overboard? Moreover, I’ve seen others who live in fortresses of caution and self-righteousness, showing no grace to those who live more freely. In either case—there, but for the grace of God, go you and I.

God forbid that I punish my younger self for holding respectable principles. No—I’m just saying that I held them too tightly. What began as desire to avoid sin darkened into judgment of (I called it “praying for”) anybody who appeared to enjoy what seemed dangerous, no matter how responsibly they enjoyed it. So long as “the laws” of my moral universe served as guardrails to keep me from crashing out of bounds, they were meaningful. But when I began looking down on others from a place of prideful “righteousness,” my precious morality stopped supporting life and stifled it.

With the guidance of teachers like Reinsma, I’m coming to see how my fears of injury have kept me from climbing mountains. I explore a larger world now, and I’m grateful. As we learn to exist in that tenuous balance between courage and caution, we will all stumble. But that’s how we learn to mature from the basic exercises of “righteousness” into the exhilarating dance of grace.

A Grand Conclusion, A New Beginning

At the conclusion of Dead Poets Society, Mr. Keating is betrayed by a student and dismissed by the school. But as he departs from a faculty of smugly authoritative traditionalists, he clearly remains the boys’ one true mentor, teacher, and inspiration.

For Dr. Reinsma at Seattle Pacific, the story has a happier ending. His “Last Lecture” was met with uproarious applause from a teary-eyed audience of grateful students, alumni, and admiring faculty. I cried too. But I realize now, thanks to the final moments of Dead Poets Society, that Dr. Reinsma cannot retire from teaching. A title, an office, a classroom—those are not the source of his influence. It’s who he is. It’s how he lives. Those around him will go on learning from his example.

The Dead Poets Society honors Keating by standing on their desks. It’s a beautiful tribute. It works. But I don’t want to stand on a desk for Reinsma. Someday, I’d like to stand behind one. Or, wait . . . no! Better yet—I want to push desks aside entirely, draw students out of gridlike rows, and go with them into larger worlds that my greatest teachers opened for me.

It would be a daunting responsibility. And an extravagant privilege. I would need a healthy sense of caution, yes. But also—a courage better known as “faith.”

A great film about linguistics has arrived...

"I like Arrival because it’s about a linguist and about the kinds of things linguists find fascinating. I am not a scholar of film. But I do know well-done linguistics when I see it, and I see it in Arrival."

That's the opinion of Dr. Kathryn Bartholomew, who has been a regal and inspiring professor of linguistics at Seattle Pacific University over the last three decades.

When I launched a new interview series at North By Pacific Northwest, I began by asking Dr. Bartholomew which film she would show people if she were invited to host a screening. Her choice was a pleasant surprise.

You can read her insights into Denis Villeneuve's recent science-fiction brain-buster at spu.edu/nxpnw.

Three Identical Strangers (2018)

On an impulse of curiosity, I ventured out for a late-night movie at my neighborhood's second-run theater. The title, Three Identical Strangers, was intriguing — especially since I knew it was a documentary. But that's the only thing I knew.

I expected the theater to be quiet and almost empty. After all, this movie isn't exactly a box office smash. And it's been playing for weeks. But I was pleasantly surprised. Why were so many people out to see this so late at night, and so late in this movie's theatrical run? I don't know, but my guess, now that I've seen it, is that word-of-mouth is spreading. From the opening moments to the end, it's riveting. Everybody stayed, silent and gobsmacked, and then burst into boisterous conversation that continued in the lobby long afterward. It seemed everybody was eager to come to terms with the twists and turns of the story they'd just discovered.

I'll keep my synopsis to one basic paragraph in order to preserve the movie's surprises:

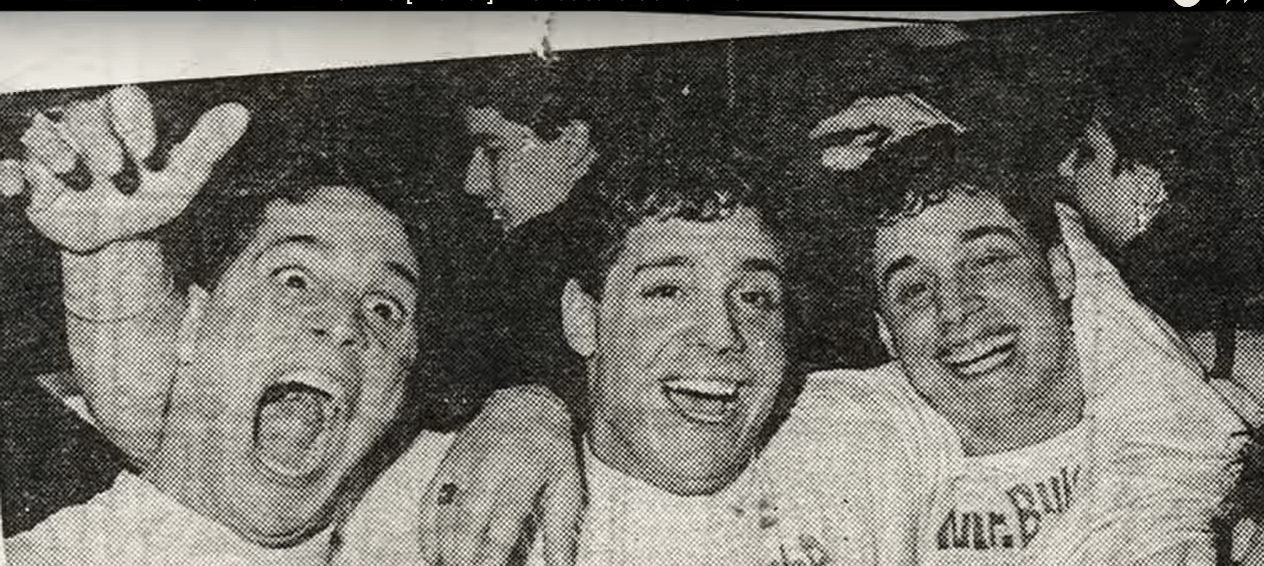

Three Identical Strangers zooms in on three young men—David Kellman, Eddy Galland, and Bobby Shafran—who, upon discovering one another in 1980, find that there's a good reason they look alike, sound alike, think alike, and act alike: they're triplets, separated at birth, and then adopted into families who didn't know their new sons had brothers.

It's also about how their story brought them sudden superstardom, success, and challenges beyond anything they could have imagined. (The American television audience, so easily and eagerly entertained, just couldn't get enough of the fact that all three brothers preferred Marlboro cigarettes, apparently.)

It's also about differences between the families that raised them. But you're probably already sensing that things will take a dark turn (several, actually).

And then it does: Troubles emerge not only within the brothers' seemingly miraculous unity but also in the culture that surrounds them. In fact, the dangers from outside have been working in sinister and stealthy ways from the beginning. You might begin to wonder if this isn't a documentary at all, but an unnervingly lifelike sci-fi/horror film.

In short, it's a story about "nature versus nurture"—with a heavy dose of Dr. Ian Malcolm's rant about the hubris of reckless scientists.

And by the end, it's become a powerful reinforcement of Rogers' philosophy.

I've been thinking about it for days now. Wardle seems fascinated by some of my favorite questions: How much of who I am is influenced by the basic building blocks I've inherited from, say, my grandfathers, both of whom were carpenters? I'm not a carpenter, but when I write, I am preoccupied with architecture. Is there something happening here? Or have I become someone shaped more by teachers, texts, and other outside influences?

Even more so, I'm interested in the relationship between who we become and how much love we've received growing up.

You may hear in those words an allusion to another recent documentary: Won't You Be My Neighbor? Ever since that profoundly affecting movie opened, I've been haunted by Fred Roger's words: "Love is at the root at everything, all learning, all relationships, love or the lack of it." The insight here isn't exactly breaking news, but those are just the right words at just the right painful moment for moviegoers like me who are grieving the loss of wisdom in the White House, and the loss of love and compassion as an American priority.

How did I not know this story already? It was in the papers when I was a newspaper-loving ten-year-old; it was the focus of talk shows and news programs that I watched. (Good to see you again, Phil Donohue and Tom Brokaw!) With its charismatic leads, its hilarious twists, and its unsettling true-crime revelations, it's as movie-worthy as true-life drama gets. But I wouldn't want to see a full dramatization: There's just, well... too much drama, and it works because you have to keep reminding yourself: This is real. These aren't actors. This script hasn't been revised to sensationalize the truth. And if you tried to depict these developments in a big studio production, with one actor playing three parts, you'd lose the film's best "special effect": the physical reality of the triplets themselves.

No, a documentary was the right choice — and director Tim Wardle has organized his material here brilliantly, his chapters carefully arranged not only for suspense and surprise but also to give weighty attention to the ethical and philosophical questions raised by each new stage of the story. It's remarkable how much impressively useful and entertaining footage of the actual events exists, and how effectively that footage leads the audience from the initial amazement, laughter, and joy, into sudden alarm, a sinking feeling of suspicion and dismay, and then grief, and, ultimately, well-founded anger.

Chapters are stitched together with modest but effective recreations, something that could so easily have been overdone. At times, the filmmakers underline the Big Moments too heavily in ways that distract from, rather than enhance, the drama; these events are drama enough on their own. (The only moments in the movie that annoyed me were a few occasions when the filmmakers decided to replay key clips, again and again, as if to say "Remember this moment? How do you feel about it now? And... now" )

It's a minor quibble. I was engaged—enthralled—throughout. The film never felt like it was embellishing the story to sensationalize it. And I was particularly intrigued because of my age: Everything from the footage of TV news and TV talks to the fashions, furniture, cars, and styles reinforced my amazement that these guys were growing up in the same world where I'd grown up, and having such wildly different experiences. I can't imagine what life was like for any of them, in these bizarre circumstances, and yet their contexts were so familiar that I kept expecting to see my own family members in the background, leaping from my old Polaroids to the screen.

That makes the inhumanity of the film's "villains" that much more troubling. When, in the movie, an exasperated man asks how it can be possible for human beings to be so audaciously evil in the mistreatment of parents and children, I wanted to stand up and say "Preach!"

And I'm sure that my anger was increased by my awareness of horrors happening in the world today. This may seem like something of a tangent, but it really isn't. Three Identical Strangers relies on the fact that a moviegoer's conscience will recoil at the idea of family members being separated and exploited.

This is a painfully difficult movie to watch in a year when Americans are welcoming the vulnerable, the desperate, the poor, and the war-scarred by breaking up their families, throwing their children in cages, deporting the parents, and doing all of this in the name of "security."

I used to criticize Hollywood movies for making villains too preposterously heartless, but man... I've learned the hard way that there is no such thing. I hope I live to see the great and harrowing documentaries that memorialize the names and faces of those who have written this year's atrocities into American history, to caution coming generations that seemingly unthinkable sins can be committed right here, right now, by the people all around you. It happened when I was a kid. It's happening now. If we're not careful, it will happen to people we know. If we're not attentive to the Spirit of Compassion, we'll be complicit in similar sins.

After all, no matter how different we are, based on genetics or upbringing, we all have the potential to set own interests over the well-being of others, the capacity to rationalize our crimes.

Crazy Rich Asians (2018)

Busy days call for fast, spontaneous writing. I have an hour, so here's some quick thinking about Crazy Rich Asians...

~

What I knew going in:

This is an important big-screen event for American moviegoers.

Directed by Jon M. Chu, Crazy Rich Asians is based on the bestselling novel by Kevin Kwan. And it's inspired a range of positive reviews, from euphoric raves calling it "fun, funny, gorgeous, and swoon-worthy" and "a joyous, eye-popping, dramatic spectacle," to begrudgingly positive assessments that it is both "refreshingly unfamiliar" and "deeply formulaic."

And it stands out among 2018 big-screen releases in the U.S. for one very good reason: It's been 25 years since the last big-American-movie-studio production of an English-language movie featuring an all-Asian cast. That was The Joy Luck Club, which was delightful, and which should have been (but, alas, wasn't) the first of many such productions. (More about this later in the review.)

~

What it's about:

A girl loves a boy, so money shouldn't matter... right?

Wrong — that is, if you ask the boy's rich mother who has wealth-and-family traditions to uphold.

If you don't already know the premise, well, it's simple: Rachel Chu (Constance Wu), an economics professor at NYU, is about to learn that the term Chinese-American is less about being Chinese than she thought.

When she travels with her boyfriend Nick Young (Henry Golding) back to Singapore for his best friend’s wedding, she'll meet his family and discover (how did she not already know?) that he is the Prince Charming of one of China's wealthiest and most prestigious families. His mother and grandmother, the Young family's matriarch, are devoted to tradition and wealth. And even though she's a distinguished academic, she falls far short of "marriage material" in the eyes of Nick's mother.

If this sounds like a Cinderella story, that's because it is: It's built on that familiar fairy-tale scaffold, right down to the moment where she runs away at midnight and her prince has to pursue her. Chu doesn't hide that fact; he celebrates it throughout.

~

What I admire about it:

The cast, particularly Constance Wu and Michelle Yeoh.

In the lead role of a crowded movie, in which everybody seems to be competing to give the performance that everybody heads home talking about, Constance Wu is perfect. She convinces us right away that Rachel is not only pretty but also genuine, thoughtful, and intelligent. In other words, she's not the genre standard of the easily confused, easily duped, easily shaken damsel-in-distress who needs a romantic rescue. Surrounded by examples of glamour-standard beauty, Rachel outshines everyone by demonstrating integrity and conscience, by serving as a calm at the center of the movie's sensory-overload storm. She seems three-dimensionally human, a character of nuance and thoughtfulness, and I wanted to see her escape the flamboyance of the film so that we could enjoy her company better. I would have happily followed her anywhere.

And then there's Michelle Yeoh. She seems like she might be reflecting on other, better roles she's played as she wanders through the film, a rare and regal talent caught up in a carnival of Chinese celebrities. Even though she's the "wicked queen" role in this fairy tale, one that could so easily be overplayed and one-dimensional, she makes Eleanor Young a contemplative, troubled soul burdened by a difficult pas. She doesn't need a dramatic redemption arc so much as she needs time to navigate a storm of conflicting emotions and influences in order to arrive at a moment of clarity. I suspect that sequels are not likely to focus on Eleanor, but I kind of wish they would.

~

What gets emphasized in everything I read about this movie:

Representation.

And rightly so. The more I've explored the world of cinema, the more frustrated I've become by how little of the world's most glorious cinema goes overlooked by American audiences merely because they're conditioned to prefer movies about Caucasians.

As I walk around any neighborhood in my city, and when I teach classes of American undergraduates, I see a dazzling diversity of ethnicities and cultures. But when I join large crowds at popular movies, I generally see the screen dominated by white folks who occasionally have a token Diversity Friend. It's easy to see how so many rural Americans who prefer a white-centric neighborhood live under the illusion that America is a white nation only lightly seasoned with Other Kinds of People. It's time we started seeing more depictions of the rest of the world, and the cultures in which our neighbors have history, families, and foundations.

Will Crazy Rich Asians inspire more of this kind of thing? Not because it's the right thing to do, no. But if it makes a lot of money, yes. And if the opening weekend numbers are any indication, I think we'll be seeing more movies that feature Asian Americans — including, I suspect, sequels. (Kwan has written two follow-ups to the novel.)

Whatever works: We need a big screen that acquaints us with a larger, more diverse world, so that we can discover common ground with — and care for — our neighbors of all nationalities, colors, and cultures. I'd love to see more more movies set in Singapore — and other locations that are as foreign to most Americans as Mars — that unite American audiences.

~

What the movie actually looks, smells, and sounds like:

A simple rom-com cupcake soaking in a bathtub of money sauce.

~

What the story thinks it is about:

Money is exciting, sure, but it will mess up your life, Cinderella. Choose true love over money if you want to live right.

~

What almost everybody was talking about as I got caught in the slow-moving crowd traffic to the exit:

Man, money is awesome.

For a film that wants us to admire its Prince Charming for his seeming immunity to the wealth-focused priorities of his family, the majority of the screen time feels wildly disingenuous. I'm drawn back to the question that I find most interesting to pose to any movie: What does this movie love? I agree with Filmspotting's Josh Larsen, that Crazy Rich Asians seems to be "mostly a celebration of conspicuous consumption."

Based on what I've seen so far this year, this is the best big-screen example of a frustratingly familiar cognitive dissonance: It's a rare thing to see a movie that practices what it preaches. The relationship between what you say you believe in and what you demonstrate by your decision-making will prove to others whether or not you are a person of integrity. Similarly, what a movie seems to mean through its narrative and what it really means by its visual preoccupations are often two different things.

Crazy Rich Asians is a three-ring circus of excessive spending. The camera ogles over the dresses, the jewelry, the houses, the cars, the feasts — and not with any interest in particularity that might give us an appreciation of any one particular exhibit, but rather with a determination to render us helpless by sheer relentlessness.

~

Note: Rachel is the Cinderella of the movie. She's the Chinese-American poor girl from the cellar being drawn into a Chinese Prince Charming's lavish world of the rich and powerful. Her character is a lowly economics professor who teaches at NYU. Do you know what the base salary is for an economics professor at NYU? $215K a year. That's this movie's idea of The Poor Girl who audiences will find relatable.

P.S.

Oh, yeah... did I like it? It was a pleasant, air-conditioned escape from the health-advisory air pollution choking Seattle right now.

And, again, it gives me hope for a richer, more diverse American cinema.

Having said that, no, I don't think there's enough here to make it a must-have for the home library. I recommend it as an amusing entertainment for a Friday night with friends. Like an over-decorated cake, it's a sensationalized sweet treat and little more. And cakes aren't really my thing.

Eighth Grade (2018)

I'm watching Eighth Grade, the first feature film written and directed by standup comedian Bo Burnham. And we've come to the scene in which 13-year-old Kayla, played by the effervescent Elsie Fisher, digs deep for the courage to walk out into a classmate's crowded backyard and through that rite of passage called a Pool Party.

The movie is playing on a typical Seattle arthouse cinemas screen. But this vivid flashback I'm suffering is playing in IMAX 3D.

The movie is playing on a typical Seattle arthouse cinemas screen. But this vivid flashback I'm suffering is playing in IMAX 3D.

Bear with me a moment. Let the memory play out...

I've arrived at Corrie's house for my class's first pool party. This place is a mansion. And, meandering about in swim trunks, a towel slung over my shoulder, I have it all to myself. I'm 14 years old.

While air conditioners hum softly—an unfamiliar tone, as this is Portland, Oregon, where 80 degrees gets categorized as "a heat wave"—I move in barefooted disbelief through a labyrinth. Adrenaline roars in my ears as I meander from strange, empty bedroom to strange, empty bedroom, my steps soundless across thick carpets that seem brand new.

I don't want to be there. But I know I have to be. It's expected. All the cool kids are doing it, and I so, so want to be cool.

Still, now that I'm here, now that I've stripped down to my trunks, I can't bring myself to go out there. Out there. In front of everyone.

I examine dust-free antiques that look more like showroom exhibits than the stuff of a family home. I scan bookshelves for familiar titles, finding only romance novels, their covers unnerving me with images of women in billowy dresses sinking into masses of masculine muscle. Picture frames open like windows onto idyllic, rainbowed villages. By comparison to my natural habitat, this is a rich family's wonderland. I feel out of my element. Intimidated. Painfully aware of my naïveté. A cat glares at me, judging me, from a perfectly spread bed.

This is one of many vivid memories I retain from the one and only pool party I ever attended in middle school. I remember that long, terrifying silence in the house, when I occasionally mustered the courage to approach a window and look down into the backyard, with its lawn of chemically amplified green, and its enormous pool. My classmates were shouting, laughing, splashing, diving. They seemed liberated, wildly alive—so different from the kids I knew in the classroom, where I was the confident, happy, talkative one and many of them seemed miserable.

I remember that I stepped back into another of the mansion's many bathrooms to look yet again and see if this mirror would give me any more confidence. It didn't. My skinny torso, my skinny arms, the moist and pimpled outbreaks on my face—none of it looked ready for daylight.

I tried to remember how to be in a pool, but all I could remember was sitting in a plastic wading pool when I was seven, and abandoning swimming lessons at an athletic club due to frustration and an allergy to chlorine. But I had to go out there. The potential for humiliation at hiding in the house was as high or higher than it was for jumping in with kids who actually knew how to swim.

I threw my towel over my shoulder. "Get it over with," I said. "People who are even less popular than you are out there." That didn't help.

I took a deep breath, said an earnest prayer, and I walked out the sliding glass door into certain humiliation. I strode swiftly across the patio. Everything shifted to slow motion. I reached the edge of the pool. I saw a few heads turn. I heard someone say my name. I jumped.

~

It's all coming back as I watch Eighth Grade for the first time. My heart is stuck in my throat. The suspense is worse than it's been at any other movie this year—including Hereditary with its ghosts and Mission: Impossible—Fallout with its threat of nuclear apocalypse.

I'm not the first to respond to Eighth Grade as if it's a PTSD trigger. Few escape those years of physical transformation, emotional turmoil, peer pressure, and anxiety without scars. And few filmmakers have the courage, the artistry, the empathy, and the resolve to represent those years truthfully. Most movies about early-teen experiences oversimplify things with wish-fulfillment endings, characters rigidly categorized into types, or an obsession with raunch that suggests the storytellers never really grew up.

But Bo Burnham, with the help of Fisher's extraordinarily complicated and convincing lead performance, has given us a film that strikes me as creative and compassionate. It's like he had it carefully b.s.-tested for authenticity by real-life eighth graders. It works because of his care and attention to this lonely character, the way he draws us into her experiences, the way he refuses to get lazy and pour this batter into a pre-existing cake mold.

I almost wanted this movie to settle for a formula. It would have provided some relief from the all-too-real stress of revisiting that context of crushing uncertainties and strange longing. I keep waiting for one classmate to emerge as a villain. That would make it a movie, a routine, a game I know how to play. But it doesn't. My eighth grade class didn't have villains either—just a lot of similarly insecure and awkward teenagers. Sure, some of them were guilty of bullying—we glimpse that potential in Kayla's classmates. Some were self-absorbed and clique-ish—and those are easy to spot here too. My class, like Kayla's, had one or two who were extremely odd in their hobbies and obsessions. But Eighth Grade refuses to cast judgment on anybody. Adolescence is like a storm that has descended on this community of young people, and they are all enduring the pressure in their own ways.

In that, I'd rate this up alongside Anna Rose Holmer's The Fits as one of the finest depictions of adolescent struggles I've ever seen.

Most importantly, Eighth Grade refuses to cast judgment on adults. I was worried when, in an early scene, the students suffer an instructional video about puberty in which the motivational speaker, with a cloying grin, assures them that "It's gonna be lit." I flashed back to Brian Dannelly's Saved!, with its unlikely authority figure—half youth pastor, half high school principal—who stands before evangelical high schoolers and shouts "Who's down with G-O-D? ... Let's get our Christ on, let's kick it Jesus-style!" Oh, it rang true. I remember recoiling when instructors tried to make students like them by exploiting a trending vocabulary. The nightmare is real. But it's also an easy way for a screenwriter to make a mockery of parents and teachers, dividing comedies into sympathetic kids and intolerable grownups.

Here, Kayla is kept from the usual us-versus-them isolation by the presence of a loving father. As Mark, Josh Hamilton gives us an admirable man, one who is as awkward in being a single dad to a teenage girl as Kayla is awkward at being that teenage girl. They struggle together. They learn together. And Burnham gives their relationship even more impressive distinctiveness by not abandoning his subject for the easier, more familiar questions about What Happened to Mom?, or When Will Mom Come Back?, or Will Kayla Forgive Her?

Instead, Burnham sticks to a sturdy and rewarding structure, maintaining a laser focus on Kayla's struggle to process her daily difficulties by a bold use of social media. Instead of relating the details of her embarrassments, failures, and confusion in an old-fashioned diary, Kayla shapes her struggles into pep talks and advice columns, which she speaks spontaneously into episodes of her own YouTube web series, greeting viewers with a friendly "Hey, guys!"

Is anybody else really listening? She'd like to believe that other insecure high school girls might find her, lonely as she is. And maybe they will.

But here's the important thing: Kayla is listening.

She's aspiring to speak from a place of wisdom she has not yet obtained. This might seem tragic, even presumptuous. But the episodes become an inspiring affirmation that much of what we need most we carry in ourselves. In a sense, she's becoming the mother she never had, the coach she needs, and the friend she'd rather find on the other end of a phone. She looking back at herself with the loving acceptance and compassion that she needs, the love she finds difficult to accept from her father who, genuine as he is in his encouragement, is supposed to say those things.

And while these motivational speeches are simplistic, focused on the power of positive thinking, they consistently reveal a girl finding ways to keep hope alive, constantly demonstrating a belief that she will get through this, that there are lessons to be learned here. Establishing a form for her talks, she is developing a meditative practice. From that "Hey, guys!" opening to the liturgical benediction—an "OK" sign and the salutation "Gucci!"—she is crafting variations on a form. She is cultivating skills. She is finding her voice.

A movie bent on crowd-pleasing would fast-forward and show us a grown-up Kayla whose web series has gone viral and made her a star. Nope. This isn't that kind of movie. When good things happen for Kayla, they don't feel programmed; they feel surprising. In an inspired tangent, Kayla gets an opportunity to "shadow" a high-schooler, who assures her that she will survive this difficult season. It's an unlikely connection that feels absolutely real in its unpredictably, in its unexpected blessings, and in the unexpected peril that presents itself when she finds herself in unfamiliar, unfriendly circumstances.

The movie concludes not with a Napoleon Dynamite talent show, not with Kyla winning the heart of her dream boy, not with the emotional high of a diploma. It ends with a surprise too good to spoil—let's just call it "The Chicken Nuggets Scene"—that may be my favorite big-screen conversation of the year, a joy in its spontaneity. And then it guides us with Kayla across a threshold and into the next chapter.

We might read the conclusion as cynical, suggesting that life is an unending process of starting at the bottom of something, struggling, and then starting at the bottom of something else. Or, we might see it as meaningful reminder of Fred Rogers' observation, so beautifully captured in the documentary Won't You Be My Neighbor?: "Love is at the root of everything—all learning, all parenting, all relationships. Love... or the lack of it."

Come to think of it, just as that powerful documentary asks adults to pay loving attention to the eighth graders in their lives, or the eighth graders still hurting within themselves, so Eighth Grade is ultimately about much more than adolescence. As a new professor among a faculty of seasoned experts, I feel like the new kid on the block all over again, embarrassing myself, learning by trial and error, hoping that I'm accepted and liked, hoping I seem confident when I'm not. In Kayla, I see who I was, but I also see who I am, and I'm reminded again of the value of honesty, courage, taking risks, and making something out of my hardships. In Kayla's videos, she's talking to herself, but like Fred Rogers, she's also talking to us. The world can be big and intimidating and even cruel, but pay attention: It might yet still become a beautiful day in the neighborhood.

Here's an idea: Maybe Burnham could make this a series, something along the lines of Before Sunrise, Before Sunset, and Before Midnight. What I wouldn't give to revisit Kayla on her last week of high school, so I can learn alongside her some more.

~

So, what happened when I jumped into the pool?

Hoo, boy... I'll tell you.

The sunlight was camera-flash fierce. The impact was like a gunshot. The splash soaked everyone around me. I remember feeling an instant of relief: My body was in the water—it was blurred by the waves. I was in. I was okay. Nobody had laughed.

But then came the next instant of awful recognition: Like Linus clutching his security blanket, I was still holding tight to my towel. And before I could think what to do, the question on everybody's mind splashed me from all sides: "Why did you bring your towel?"

"So I could do this!" I announced, in a moment of supernatural creativity. I started lashing out at them like Indiana Jones with a wet, stinging bullwhip. They scattered, opening up a moat around me. Unsurprisingly, nobody wanted to play this game. Neither did I. I wanted to be somewhere, anywhere else.

I don't remember how I survived it. I don't remember anything else. I buried it all...

...until I saw Bo Burnham's Eighth Grade.

Still, the movie made me more grateful for my middle-school years than I had been before. It made me grateful for how many loving, caring adults had surrounded me in those years. It made me grateful that I, like Kayla, found creative outlets in which to turn my suffering into art.

And it made me grateful, above all, that I was born before the Internet, digital devices, and social media. I was almost ignorant of pornography. (Kayla gets voted "Most Quiet" by her classmates. At 13, I could have been voted "Most Sexually Naive.") I didn't text anything regrettable that would become a matter of public record. I don't have to live with a public museum of unwanted images. I don't have to worry about what embarrassing moments other people my age might have on me. I was able to let the present become the past... and then the distant past, just the way God intended.

Like that pool party, which I had completely forgotten until this.

So, thanks, Bo Burnham. Jeez.

Mission: Impossible — Fallout (2018)

Before I get into the specifics of the Mission: Impossible movies, I need to set the stage with a true story:

Artists, at the beginning, learn by imitation, right?

As the end-credits rolled on my first viewing of Raiders of the Lost Ark—I think I was about thirteen—I was seized by an urge to invent my own action hero. Indiana Jones awakened me to the possibilities of a new kind of adventure storytelling, one that didn't rely on superpowers or spaceships.

I called him "Jeremiah Smith." (Even the name was an imitation, syllabically.) I quickly sketched out storylines, a cast of characters, a crisis, and a whole lot of unlikely action sequences. My typewriter clattered and pinged until I'd piled up a stack of stories, each one longer than the last—wilder, more convoluted, more extreme. My hero had his distinctive qualities. He had wisecracking sidekicks so he’d have someone to talk with along the way. He went up against mad villains bent on global destruction. He charmed women wherever he went. He chased McGuffins around the globe. And he had a sharp, snarky sense of humor.

In short, he was everything most boys, in their vain and self-serving fantasies, want to become when they grow up.

I wrote a lot of these stories. I still have them here in a drawer in my home office. They humble me. They remind me of how susceptible I was, even in a context of strict evangelical Christian community, to “secular” ideals: I wanted to grow up to be someone people adored as a superman. I wanted treasure. Weapons. Sidekicks. I wanted the adoration of women. I wanted fame.

Sure, I’d imagined my guy as a globetrotting Christian missionary to give myself a sense that he was a Good Man doing God’s Work. But the result was a weird hybrid: I wanted a hero who saved the world with good punching and good shooting, spectacularly humiliating his enemies while also maintaining an aura of holiness. I wanted the glamour of worldly heroes with the justification of the church.

Today, those homemade stories of typewriter ink, crayon drawings, and staples, are not very meaningful to me... beyond their nostalgia factor, anyway. But I can remember clearly that the primary pleasure of writing them had nothing to do with winning souls for Jesus, or for engaging in vicarious violence. No—it was something else, something more along the lines of architecture: It was the work of imagining high-speed chases, narrow escapes, and traps for catching villains. That was its own reward. It carried with it the same kind of joy that I imagine puzzle-makers and computer coders feel when all of the pieces suddenly fit together to achieve an unlikely result. It is, I imagine, what a coach feels when he trains a team to execute a play to perfection.

You’ll notice that I gave up writing adventure stories. Something was always missing. I didn’t know how to bring the series any stakes or any soul. Like other action heroes, Jeremiah Smith's luck was constant, so that no matter how heavily I stacked the deck against him, he survived. He always won the day. These stories all seemed too easy. They lacked something that made the exploits of my favorite adventure icons so rewarding.

What was missing? What was this magic ingredient that could make an adventure story so satisfying?

Read The Lord of the Rings. Watch those original Star Wars and Indiana Jones movies. You’ll see it. The greatest adventures aren’t about whether or not the heroes win. They’re about what the character learns. They’re about a greater design than even the character understands. The heroes in these stories fail sometimes. They’re reliant on others. They’re humbled, but their imperfect efforts serve—and, ultimately, glorify—a goodness greater than themselves.

I came to appreciate that if a story is all about a hero’s superiority, strength, and righteousness, it will have, at best, the shallowness of wishful thinking, and, at worst, the harmful delusion of idolatry.

~

Still with me?

Let's talk about Ethan Hunt.

~

The first three movies in the Mission: Impossible franchise reminded me of my 13-year-old self's storytelling. For each one—Brian DePalma’s exciting original (1996), John Woo’s ridiculous sequel (2000), J.J. Abrams’ clever but frustrating third (2006)—I bought my ticket for opening day. I got a bunch of first-rate action scenes. I saw the good guys outwit bad guys. I felt somewhat satisfied. And then I felt little or no compulsion to revisit them again. (I have, recently, gained more respect for DePalma’s sturdy original, but more for its style than its storytelling.)

Then came the fourth and fifth: Brad Bird’s Mission: Impossible— Ghost Protocol (2011), and Christopher McQuarrie’s Mission: Impossible—Rogue Nation (2015). These were much more fun than the first three. They kept jacking up the Wow Factor of the stunts and fight scenes. And the characters were, at last, somewhat engaging. They established memorable chemistry, the primary hero, Ethan Hunt (Tom Cruise), and his new IMF (Impossible Mission Force) sidekicks—Luther Stickell (Ving Rhames) and Benji Dunn (Simon Pegg)—improvising their way through ridiculous challenges. And they avoided the dulling influence of digital effects, keeping us grounded in the work of humans and hardware in front of a camera.

But even those films failed to give me a reason to care. I felt like I was watching movies made by people who—like me in my early teens—really liked the great adventure films, and, in a spirit of enthusiastic imitation, had learned how to choreograph excellent action sequences. But they hadn’t found the secret to making the stories matter.

So the skyscraping raves for Mission: Impossible—Fallout published over the past several weeks raised my hopes.

Would this movie—the first to bring back a previous director—McQuarrie—live up to the hype?

Would this one finally influence more than my adrenaline?

Would it make me care?

~

Upon exiting the only opening-day showing of Fallout I could find in Roswell, New Mexico, in the company of about a dozen moviegoers, I shared the crowd’s buzz. In that adrenaline afterglow, with the outstanding Lalo Schifrin theme ringing in my ears, I felt a rare satisfaction: I had seen a great summer movie.

I’d seen the IMF team strive to save the world from a nuclear holocaust. I’d witnessed death-defying stunts. I’d seen one of the most wildly unlikely and breathtaking chase scenes, involving car, trucks, vans, motorcycles, and more, in a whirlwind tour of Paris. I’d seen a first-rate cast achieve engaging chemistry. I’d seen (I had no doubt) the very best installment in a franchise two decades old.

Yeah, you’ll hear the same thing from me that you’ve already heard from others, and that you’ve probably said yourself: While Fallout’s narrative is unnecessarily (even desperately) complicated, and some of double-crosses are eye-rollingly easy to guess, the movie relentlessly delivers awe-inspiring thrills: a dizzying skydiving sequence, a vertiginous helicopter chase, and a traffic chase as ludicrous as it is exhilarating. (Rebecca Ferguson on a motorcycle here is about as close as live-action can come to the brilliant biking of Elastigirl in Incredibles 2.) I’m almost embarrassed that McQuarrie could suspend my disbelief through a scene in which Tom Cruise chases a vehicle through a city on foot... and gains on it.

I did my due social-media diligence: I logged on to Letterboxd and promptly gave the film four-and-a-half stars out of five. On Twitter, I raved that Fallout is as exciting as a supercut of every action scene from all three original Indiana Jones films. (And, I didn’t say, many of this film’s sequences seem directly inspired by those films.)

The glow lasted a couple of days. I’m still eager to see the movie again, but no—nothing here has raised the bar for the Mission: Impossible franchise. Ethan Hunt remains far, far short of greatness as a character. We know he strives to save the world and to serve America’s best interests. But why? What are his deep motivations? What does he believe in... besides himself?

These questions have become an itch I haven’t been able to scratch. Imagine chugging an energy drink that makes you feel like Superman for several days, but that then leaves you with a faint, annoying headache for the next two weeks. I just cannot shake a lingering feeling of irritation with Fallout. And, the more I think about it, the more I’m beginning to see the whole series, in retrospect, as significantly flawed.

The problem, I think, is that the hero has too much in common with the actor.

~

Ethan Hunt is the perfect role for Tom Cruise.

While I prefer Cruise in the roles of guys who think they’re brilliant but obviously aren’t (think Jerry Maguire, Magnolia), or—even better—in the roles of villains with salesman smiles and vacuous interiors, I think Ethan Hunt is the role Cruise was born to play because I cannot imagine an actor so dedicated to remaining in peak physical condition, capable of fighting, driving, flying, and especially running in a way that makes him the most believably talented superhero in the movies. We believe Hunt can jump from one building to the next, climb cliff walls and skyscrapers, and steer a helicopter at high speeds through jagged mountain peaks to catch and fight someone in another helicopter... because Tom Cruise can do those things. That’s actually him onscreen jumping, climbing, and piloting aircraft. I don’t know anyone else who can do that.

But here’s the thing: Ethan Hunt is a superman in the most unsettling sense of the term. With the exception of Brad Bird’s episode in this series—Ghost Protocol, a film that stands out by playing up the fallibility of the characters and their technological tools—the Mission: Impossible series is a recurring demonstration that Hunt can do anything. He wins. Again and again. We’re meant to be relentlessly and increasingly impressed with him. This series is, more and more all the time, designed to make us amazed at the glory of Ethan Hunt.

He's the big screen's Six Million Dollar Man... adjusted for inflation.

Considering Tom Cruise’s unwavering devotion to Scientology, we might smell something rotten in the state of this franchise. Hunt’s lack of character—he’s so consistently one-dimensional that he makes Indiana Jones seem Shakespearean—keeps us focused almost entirely on a physical specimen. Look at how special he is. For Skywalker and Solo, the story's about the apprehension of The Force that “binds the galaxy together.” For Indiana Jones, it’s not about his unbroken record of achievements—no, he fails all the time: It’s about encounters with awe-inspiring wonder that ultimately humble him. For the heroes of The Lord of the Rings, their feeble fellowship only achieves a victory in their embrace of cooperation, humility, and sacrificial love (and even then, there are heavy losses). Great hero stories are about going with them into some kind of revelation, in the service and realization of some greater glory. Ethan Hunt movies are about looking at him.

And in Fallout, the series’ adoration of its superman goes to unsettling extremes.

I'll give you four ways to look at this:

First, there’s the slack-jawed helplessness of women who encounter him. By the end of this film, Hunt is adored by three different women: The White Widow (Vanessa Kirby), a sophisticated Caucasian blonde who may as well be a supermodel; Ilsa Fause (Rebecca Ferguson), a Caucasian super-spy who serves her government unless it means inconveniencing Hunt, who turns her on; and Julia (Michelle Monaghan), his ex-wife, whom he left for the noblest of reasons, reasons that amplifies her love into a sort of transcendent reverence. Now that’s a superhero: He can leave behind a marriage in such a way that his ex-wife, moving on, will hold him in even higher regard. (My sympathies to any second husband!)

Second, there’s the way Hunt knows better than any government, any superior officer... anyone. (This film even humbles an agent played by the famously full-of-himself Alec Baldwin, making him more loyal to Hunt than the law or any fellow agent.) Hunt’ shunches are always right. His priorities are always perfect. He’s almost always one step ahead of everybody.

Third—look at his team, how they believe in his ability to achieve the impossible, how they speak in hushed amazement at his derring-do.

Fourth (and most upsettingly): consider the fact that both African American characters in the film end up bowing at the feet of the Greatest American Hero. Near the end of the film, Luther, Hunt’s most reliable backup, is given a scene where he gets teary-eyed in reverence for his superior. I felt sorry for Ving Rhames, a great actor who deserves to dominate movies of his own.

Perhaps McQuarrie and Company mean nothing by this. Perhaps it's all a blockbuster joke to them: setting up such a preposterous hero and, with dazzling sleight-of-hand, making us believe. Maybe they're intent on distinguishing Hunt from other famous white-guy heroes by making Superiority his calling card.

But in 2018, I just can’t take this lightly. Some of you will think I'm taking this too far, but I can't help it—I read the news. And if I were a white supremacist and/or a male chauvinist, thinking that the world needs a corrective that worships the muscular white male American as the ideal Human, I would love this movie. I would see a hero who confirms my self-interested, racist inclinations. If I believed that Might-Makes-Right, I’d cheer for a hero whose might is always right on, without getting distracted by matters like “the greater good.” If I disbelieved in God or any kind of Higher Power, I would be pleased to see a hero who can save the world with speed and strength and fists and double-crossing.

And so I’m a bit ashamed at how completely I was drawn in to Mission: Impossible—Fallout, leaning forward in the hope that Ethan Hunt save the world in full view of his adoring fans.

Yeah, the movie’s a lot of fun. And I still intend to see it again to enjoy the technical mastery on display in these action scenes. But I won’t be able to ignore the not-so-subtle idolatry, and the justification of everything he does.

Looking around at a world fraught with prejudice and injustice that is driven by that particular false hierarchy, I see the fallout every day.

Hearts Beat Loud (2018)

Hearts Beat Loud, from director Brett Haley (The Hero, I'll See You In My Dreams), is one of those movies the three-star rating exists to describe. It won't make any top ten lists, but it's not a waste of time.

It feels like a film that was written in an afternoon—if, indeed, it was written at all, and not just brainstormed scene by scene. And it could have been shot over a weekend. It boasts a cast of irresistibly likable stars, audience favorites who could ad-lib for the full 90 minutes and make it worth your time. It moves between locations where most of us would enjoy spending time: an old-fashioned record store; a funky Brooklyn home that doubles as a recording studio; a friendly neighborhood bar "where everybody knows your name"; and a friendly neighborhood coffee shop, too.

On the subject of beverages: If movies are the "What's On Tap" list at a bar, Hearts Beat Loud is a pamplemousse-flavored La Croix listed in "Other Drinks" at the menu's end. It's kept in a fridge under the bar for somebody who thinks it's just too early in the day for anything with a serious kick. And on a hot, stressful afternoon, that might be just the thing. If my brain is tired, if nothing needs my attention, and I stumble onto Hearts Beat Loud on TV, I'll probably decide to "watch a few minutes" and end up watching to the end. It's just so easy, enjoyable, and cost-free.

Here's a good recipe for a solid, easygoing, three-star movie:

- Get Nick Offerman—a national treasure—to play Frank, a mildly disgruntled record-store owner who hasn't entirely surrendered his dreams of being a rock star.

- Cast the radiant and wonderfully soft-spoken Kiersey Clemons (Dope) as Frank's daughter Sam—who is willing to record pop songs with her dad(but not willing to make a career of it)—and you can count on the audience's attention.

- Add the always-reliable Toni Collette (Hereditary) as a landlady, and Sasha Lane (kinder and gentler than she was in American Honey) as an artist. Develop their characters just enough so they can function as passable love interests for Frank and Sam.

- And then... the masterstroke: Convince Ted Danson to play a bartender again.

- Do a movie about music lovers right: Throw in some catchy songs. Remind us of the joy of jam sessions that worked such magic in Once and Sing Street. Then, decorate Frank's record store—Red Hook Records—with album covers that convince us that you have impeccable taste.

Follow these steps and, well... you have have my attention, if not my twelve bucks.

At this point in my review, you probably know whether you want to see Hearts Beat Loud or not. No, it's not particularly profound. Yes, it's predictable, but that's okay — it doesn't ever act like it means to surprise us.

- Will Frank and Sam, tossing off a song for fun that becomes an unexpected overnight Spotify success, decide to throw away Sam's plans to become a doctor and hit the road as a band?

- Will Frank change his mind about selling the Brooklyn hole-in-the-wall record store he loves?

- Will a world-famous folk-rock musician make a cameo as a Red Hook Records customer?

- Will Nick Offerman work those eyebrows?

- Will the movie frustrate our desire to see Woody Harrelson, Kelsey Grammer, or John Ratzenberg walk into Danson's bar?

- Will the songs be just good enough to make the movie work, but probably not be good enough to inspire anybody to cover them?

I think you can guess the answers to all of these questions.

So what's left to say?

I'll get personal:

Hearts Beat Loud gave me a chance to relax in some air conditioning after a stressful day. It made me laugh a few times (mostly because of Ted Danson), and it worked a little too hard to make me laugh a few other times. And it only made my heart beat loud on three occasions:

First... in pain, when a customer at Red Hook Records picks up the vinyl of Radiohead's A Moon Shaped Pool and then puts it back. For a moment I wanted to call the police, but then the scene took a turn that came as a relief.

Second... in amazement, when Nick Offerman picks up a guitar and starts playing, of all things, "Ocean Man" by Ween, a song I love from an album I love, and yet I rarely ever encounter anybody making reference to it. But then he abandons the performance it a couple of lines in. Come on, man! You were making me so happy!

Third... in outrage, when a customer discovers Tom Waits's Rain Dogs on vinyl in a $3 clearance bin. "Hang down your head," indeed!

But the thing that actually made me cry — yes, I cried at this movie — was the experience of seeing a record store in its last hours before closing. This movie doesn't revel in the glory of record stores the way High Fidelity did... but it's been almost 20 years ago since John Cusack set the needle down on The Beta Band, so it's good to see a shop like this on the big screen again.

It is one of my life's unfulfilled dreams: to work in a record store, organize vinyl, buy vinyl, sell vinyl, recommend vinyl, and—most importantly—play DJ in the store all day long and late into the night. The death of record stores is the death of something distinctly, soulfully human, and I have been grieving the decline for many years.

The first records I bought from record stores with my own money were soundtracks: Vangelis's Chariots of Fire, Angela Morley's Watership Down, Trevor Jones's The Dark Crystal. I still remember the thrill of standing before a glorious window display announcing the release of The Cure's Disintegration in 1989 in Portland, Oregon—the very same window where I first saw the cover art for U2's The Joshua Tree. And, speaking of U2, I'll never forget staying up until midnight in front of Tower Records in Seattle in late November 1991 to buy one of the first copies of U2's Achtung Baby. I've spent hours walking my fingers on both hands along the tops of LP covers so I can browse two stacks of records at once.

And just last week, I bought all of the remaining LP-cover frames from a frame shop clearance sale in my neighborhood and redecorated my office with album covers.