Let's talk trash: Toy Story... 4-ky!

This is Part Two of Looking Closer's review of Toy Story 4.

Part One was posted previously. Note: Part Three concerns the ending of the film, and includes spoilers.

Forky might have just become another piece of plastic polluting a park or an ocean.

He began as a spork, after all—that most disposable of utensils. But then Bonnie, during her first day of kindergarten, asked that most dangerous question—"What if...?"—and gave him an extreme makeover. Thanks to her creative genius, Forky was born. He's not the handsomest toy in the world—he looks like a cross between the flabbergasted fellow in Edvard Munch's The Scream and a high-anxiety spoon critic in an apocalyptic Todd Herzfeldt cartoon. That doesn't matter. What matters is this: He's alive... he's alive!

But will Forky stay alive?

In the early stages of Toy Story 4, this seems to be the plot's primary question. Forky, believing he's nothing but a spork, believes he's destined for nothing but the trash. But Bonnie loves him and needs him. And Sheriff Woody, who knows a thing or two about bonds between children and toys, and who values nothing more than a child's happiness, is determined to make this work. Whatever magic brought Forky and Bonnie together, well... Woody won't let anything tear them asunder.

And so, these Pixar storytellers have discovered an inspiring redemption story. In their gamble to enhance the already miraculous Toy Story world, they've stumbled onto one of its greatest inventions. Voiced perfectly (and with remarkable restraint) by Tony Hale, Forky spends much of the movie wrestling with his existential crisis — and in doing so, he becomes the funniest member of Woody's community yet.

And what a relief that is!

Watching trailers for Toy Story 4, which made Forky look like the movie's main character, I feared two likely outcomes: that he'd become for Pixar what Jar-Jar Binks was for Star Wars, or that he'd end up serving as little more than a prompt to talk about identity politics. (Being unclassifiable by the binary categories of fork or spoon, Forky looked custom-made to serve an LGBTQ spokesperson.)

Note: If you're bothered by what I've just said, check the Footnote at the end of this post.

Forky, thank goodness, is not the propaganda I feared he would be. He's an honest-to-goodness Toy Story character who earns his place in good company.

Moreover, Forky expands this franchise's vocabulary about the nature of creativity and play.

Assembled from a spork, popsicle sticks, pipe cleaners, and googly eyes, Forky's been loved into life by a child who can envision unlikely possibilities. Suddenly self-aware, he panics, knowing only that sporks are meant to be disposable. He doesn't understand what he has become: a new creature, designed to delight his Maker, capable of more than he knows. "I'm trash!" he repeatedly and smilingly asserts—and he'll amount to nothing more than that if he refuses to consider larger possibilities than he's known. To become his "best self," Forky needs to slow down, pay attention, and discover that he is loved.

When I laugh as Forky lunges madly, again and again, for any nearby trash can, I'm laughing in recognition. If you're feeling down about yourself, self-destruction can become a compulsion. I suspect that most of us have experienced this to some degree. When I'm feeling low about myself, I'm prone to wasting time with mindless distractions. For others, it might be more drastic forms of self-harm or even suicidal impulses, demonstrations that suggest we believe the worst things that have been said about us. Perhaps Forky can remind us of the absurdity of our baser impulses and the possibility that we might have more potential and value than we ever dreamed.

I encounter an alarming number of students whose insecurities are the result of conditioning—they've been taught, through neglect, abuse, and other love deficiencies, to perceive themselves as trash. (If I'm meeting this many of them in college, imagine how many more, believing themselves to be trash, see the possibility of education as a waste of time and resources.) As hilariously absurd as this combination of plastic and pipe cleaners appears, Forky gives us an outstanding opportunity to talk about a person's confidence and self-knowledge can be transformed by love.

But even this meaningful metaphor does not sum up what I love most about Forky. Above all, I love him because he's a plastic utensil glued to popsicle sticks, wrapped in pipe cleaners, and decorated with googly eyes.

To explain, I have to tell you a story:

When I was a kid, I coveted Star Wars figures, and spent most of my allowance on Star Wars figures. In the early 2000s, as Peter Jackson's Lord of the Rings films arrived, I had a second childhood and bought Middle-Earth action figures with enthusiasm. But the action figure that means the most to me—the one that I've kept within reach from early childhood to this very day—is a cheap Fisher Price figure of a scuba diver.

Here's why: One afternoon in the early 80s, as I was playing with two neighbor kids—a ten-year-old named Lauren and her younger brother Scott—we decided to round up all of our action figures and stuffed animals and dream up a story that would involve all of them. (This was a decade before the first Toy Story.) Right away we decided that these toys needed a leader, a captain, a boss. Since our priority in everything was to make each other laugh, I announced that the leader should be this arbitrary, fish-out-of-water character: this blue-suited scuba diver, whose features had been so cheaply painted on that they had rubbed off years earlier, leaving him faceless.

"Why should they follow him?" asked Lauren. I answered, "Because he survives anything. Watch." I grabbed a baseball bat, tossed this meaningless toy in the air, and struck him like a slugger. Pieces of this action figure soared and scattered over the roof of the house. Laughing, we dashed from the backyard around the house to the street. And, by sheer luck, we retrieved his pieces, one by one—all except a tiny chunk of his shoulder. Believe it or not—we reassembled him. And we realized that he was, now, more than just a leader for our community of toys. He had been destroyed, and yet he lived again! He was a legend! A mythical hero! A god-man!

"What shall we call him?" I asked. Scott, the youngest (and also the funniest), did not hesitate with his answer: "Jim!" he announced.

And thus, a legend was born. We told stories about Jim. We sang songs about Jim. We illustrated homemade comic books about Jim. Jim became an icon for us. And though I may not have fully understood it at the time, he became more valuable to me than any and all of my Star Wars figures: He represented inspiration. Just as a sock puppet came to life as Kermit the Frog in the hands of Jim Henson, and thus the Muppets were born, so I learned that a whole lot of something can come from almost nothing—that entire worlds can be spoken into existence, even with only a few ridiculous words.

That's why I felt tears sting my eyes more than once during Toy Story 4. I was reminded again of how one crazy little question—"What if...?"—can not only change the world, but it can also create new worlds.

Jim the Scuba Diver is the incarnation, for me, of the power of the imagination. Bonnie doesn't know it yet, but Forky is that for her.

I predict that, by the end of Toy Story 4, you're going to find that Forky an essential new star in the Toy Story galaxy.

But Toy Story 4 isn't just about Forky, as the trailers led me to believe. No—this movie's meditation on the connection between love and identity goes so much farther.

I'll look at that tomorrow, in Part Three. But before you move on to that post, know this: There will be SPOILERS.

Move on now to Part Three, but only if you've seen the movie, as it includes spoilers about the end of the movie.

Footnote:

Regarding my note about fearing that Forky was a prompt to discuss identity politics... don't get me wrong. I'm not opposed to addressing questions about sexual identity in art.

We need art that challenges us to move beyond simplistic and harmful binaries that have been naively established and cruelly enforced for much of human history. As someone who ignorantly and arrogantly endorsed a destructive prejudice well into adulthood, I'm grateful that experience has taught me otherwise. Human beings are much more complicated and fluid in their nature than I was conditioned to believe when I was growing up, and the Gospel's summons to love has taught me to favor grace over legalism. As a teacher (and thus, reluctantly, a counselor), I find myself frequently hearing testimonies from students about the harm they've suffered from the prejudice and presumption in their communities, churches, and families. They reject the rigid categories into which so many, for their own comfort and convenience, seem eager to force them. We need stories that lead all of us into a more nuanced, empathetic, and loving understanding.

Having said that, we don't need sermonizing or propaganda about anything from our art — especially from movies made by Pixar, a studio that has wisely avoided any proselytizing so far. As the novelist Katherine Paterson (Bridge to Terabithia) once said in a Books and Culture interview,

“Propaganda occurs when a writer is directly trying to persuade, and in that sense, propaganda is not bad. … But persuasion is not story, and when you try to make a story out of persuasion then you’ve done something wrong to the story. You’ve violated the essence of what a story is.”

So, again, I'm relieved that Forky turned out to be so much more than the Toy Story 4 trailers suggested.

Well played, Pixar! Thoughts on Toy Story 4

This is Part One of a three-part series. Don't forget to read Part Two and Part Three.

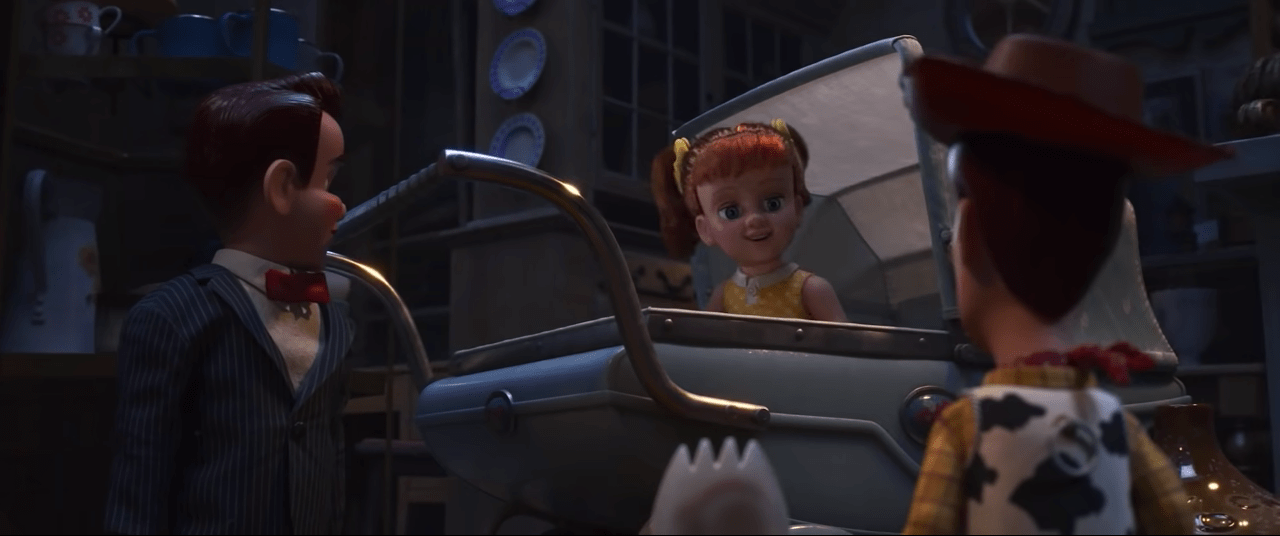

Early in Toy Story 4, Little Bo Peep, returning to the screen for the first time since Toy Story 2, mentions her faithful sheep — Billy, Goat, and Gruff — and Woody gasps, "They have names?!" She laughs and replies, "You never asked."

It turns out that there's a lot that Woody still doesn't know about his own Toy Story world. There's quite a bit that we still don't know, too.

And that's fine with me. I like unknowns. I like stories that haven't filled in all the blanks, that leave room for me to wonder. (I wish Star Wars had remained a single trilogy — Episodes 4, 5, and 6 — for the ways in which the limitations of that story inspired imaginations and made that galaxy far, far away seem full of boundless possibilities. Prequels and sequels have reduced that universe to a cosmic round of "It's a Small World.")

For that very reason, I didn't want Toy Story 4.

I didn't want Toy Story 4 like I didn't want Blade Runner 2049.

Two very different stories, sure. Two entirely different genres. But my objection to the announcement of both sequels was based on the same principle: The Toy Story trilogy (1995, 1999, 2010) and the original Blade Runner (1982) have that rare status of having classic status by satisfying their audiences with something close to perfect storytelling. By fulfilling the promise of their ambitious concepts, by developing compelling characters and meaningful narratives, and by achieving a brilliant balance of closed story arcs and promising loose ends, these movies left almost all moviegoers saying "Let's watch that again!" instead of "Make more!" Both were the fruit of ideal collaborations of innovative imaginations. Adding another chapter to either world, screenwriters would probably propose answers to questions that were a strength of the originals.

It happens several times a year: I find film critics arguing over which franchises are the greatest, and what the proper ranking of the episodes might be. The Toy Story trilogy almost always places near the top of the list, and critics seem to separate almost evenly into camps in choosing which of the three is best.

The secret to the trilogy's consistent quality? Curious, I signed up for a Pixar "Masterclass" in storytelling several years ago, and I was impressed. They know what they're doing, and I bring a lot of their strategies into my own fiction-writing classes. Their three-film Toy Story series, imagined by an innovative dream team of storytellers, is Exhibit A when it comes to gold-standard all-ages entertainment. In concept, context, and characters, it's a perfect three-part progression.

But for all of their talk about architecture, I'm being serious when I say that it was love. Pixar's best artists lavished attention on every detail of these stories, slow-cooking them over fifteen years to near perfection. (That's a longer calendar than the original Star Wars trilogy!) They took their sweet time, and that time yielded sweetness. Together, Toy Story, Toy Story 2, and Toy Story 3 cohere into one epic story about cultivating a faithful and inclusive community; about finding purpose in being who you were made to be; and, about the meaningfulness of dedication to serving someone else.

You remember it well, I'm sure: The floppy-limbed Sheriff Woody (voiced by Tom Hanks) served his child Andy loyally and kept his toy-box community focused on their people-pleasing priorities. Buzz Lightyear (Tim Allen) learned to be a team player. The supporting cast—Mr. Potato Head, Slinky Dog, Rex, and the rest—learned how to use their distinctive talents in complementary ways; how to make meaningful memories for the children who played with them; how to resist the temptations of becoming collectors' commodities; and how to overcome their fears—even their fears of annihilation by incinerator!

In an unexpected and deeply moving denouement, Toy Story 3 concludes with a vision of a perfect future for the toys beyond Andy, the boy whose love had given them life. We watched Woody and the gang find a new home with a new child—Bonnie—where they would be preserved, loved, and well-played-with. The band would stay together... forever, or something close to that.

Why press your luck and go further, Pixar? Why start a new story when the first three form an ambitious arc that satisfies so completely?

And why not learn from the mistakes of other Pixar series? Remember how Cars 2 and Cars 3 seemed to make a lesser thing of the original? Or how Finding Dory and Monsters University became shrug-worthy footnotes to the classic status of Finding Nemo and Monsters Inc?

So, that's why I responded with dismay to the announcement of Toy Story 4's development. The teaser trailer didn't encourage me—in fact, it upset me. (More on that later.) In short, I've been dreading this movie's arrival.

But then came Blade Runner 2049.

Surprise, surprise — somebody figured out how to do this well.

Our return to the world of Philip K. Dick's dystopia and the renegade Replicants turned out to be a strong standalone experience. While I do feel that the original Ridley Scott masterpiece, arguably the pinnacle of '80s sci-fi cinema, is somewhat diminished now that we cannot talk about it without talking about its lesser sequel (I especially cringe at how the humble heroes I loved in Blade Runner returned as icons of religious significance in the sequel), I'm surprised to find myself grateful for director Denis Villeneuve's vision of a larger Blade Runner world. His narrative wisely focuses on new characters, new locations, new and upsettingly relevant questions about a frightfully plausible future.

Best of all, Blade Runner 2049 doesn't do anything that forces us to re-interpret the original or experience it any differently when revisiting it. I watched Blade Runner: The Director's Cut again recently, and if anything it seemed even more enthralling, its hand-crafted special effects proving even more astounding in view of the extravagant digital animation that was used in the sequel to recreate that world. The two films don't really feel like a series—they're separate stories set in the same world: more like The LEGO Batman Movie is to The LEGO Movie than Avengers: Endgame to Avengers: Infinity War.

The strengths of Blade Runner 2049 have made me second-guess my anti-sequel inclinations. Still, I resisted the idea of bringing new imaginations, new ideas, and new risks into the Toy Story series—the only Disney animated series in which three episodes stand shoulder to shoulder among the greatest animated films ever made for anybody.

Now, after a lot of hand-wringing and lament among film critics, here's Toy Story 4.

And, lo... it seems to have shut down cynics like me and given us yet another reason to rejoice that Pixar still has some genius in the house.

Toy Story 4 is, like Blade Runner 2049, an adventure that takes place adjacent to, rather than within, the world of the first three stories. Sure, Sheriff Woody is the leading man, but his role as Community Organizer is no longer the central point of conflict. In fact, the original trilogy's community is almost sidelined in this episode—Buzz Lightyear has surprisingly short screen time, making room for a fantastic new cast characters, all of them matched with an inspired supporting cast of voice actors—including Annie Potts, Christina Hendricks, Ally Maki, Keegan-Michael Key, and Jordan Peele.

What's more—this is the funniest Toy Story yet. And it launches us in a whole new narrative direction, suggesting that this could turn out to be the beginning of a new trilogy. I end up reassured that there are still plenty of meaningful stories to tell in the Toy Story universe... so long as the writers don't circle back to revise our understanding of the original trilogy.

Pixar's achievement here is even more impressive when you look at how many cooks were working in that kitchen. The final screenplay was composed by Andrew Stanton and Stephany Folsom, but the story was pieced together by no less than eight collaborators: Stanton and Folsom with John Lasseter, Valerie LaPointe, Rashida Jones (!!), Will McCormack, Martin Hynes, and Josh Cooley, who has moved up from Pixar storyboard artist to directing this episode.

A writer list that long is usually a bad sign.

But there's a sense in Toy Story 4 that the whole team was well aware of the stakes.

In fact, there's something clever going on in the opening scene, when Woody and the gang work together to rescue a toy car from drowning in the rushing muck of a storm gutter. It's as if they're admitting up front that, thanks to their talking cars, they're going to have to pull their reputation for sequel-making out of the mud.

And they do. I hope Andrew Stanton, in particular, feels great about this movie. After being unfairly punished for the record-setting box-office failure of John Carter—which was a failure of marketing, not a failure of filmmaking—he's more deserving of a substantial "comeback" than any filmmaker I know. And with the help of an inspired team, he completes a stunt here that few would have thought possible (not unlike one of the jumps completed by Duke Kaboom, the stunt motorcyclist perfectly played by Keanu Reeves in this episode). Can we restore Stanton now to his rightful place in the pantheon of Great Family Filmmakers?

Instead of focusing on Woody's community and their chemistry, Toy Story 4 is the first story in this world to focus on the children as much as the toys. And in this, it finds three important new questions to explore:

First: What happens in this world when a child goes beyond loving the toys she's been given and applies her imagination to making toys of her own?

It's surprising to realize how little attention was given, in the original trilogy, to what a child brings to imaginative engagement with toys. In the first three movies, Andy and Bonnie played with what they were given. But my memory of childhood was all about improvisation, repurposing what I was given into crazy new inventions. With the introduction of Forky, Bonnie's first homemade toy, the Toy Story universe has exciting new questions to consider.

And that leads us directly to this story's second important question: Can someone who has been taught they are trash be redeemed and given a sense of their true value by someone else's love?

Third: Is a person's value ultimately defined by having found someone who loves them, or is their value defined by finding a way of showing love?

In Part Two, we'll dig into some trash-talking.

And then, in Part Three, I'll consider a major complaint against Toy Story 4 that's been voiced by my favorite film critic.

Stay tuned...

I Am Not a Witch (2018)

What would you do if you discovered a girl kept on a leash?

If you're troubled by that imaginary image, you'll be ensnared as I was by I Am Not a Witch, a film that most moviegoers overlooked in 2018. But you'll also be enchanted and impressed by this feature from Zambian writer/director Rungano Nyoni.

(You can rent it for a couple of bucks on Amazon and other streaming platforms.)

In what some critics are calling "an absurdist comedy" (but is it absurd?), you'll see not one but many Zambian women who, convicted — on hearsay, not evidence — of practicing witchcraft, have been sentenced to communal imprisonment in a camp, each one bound by a long white ribbon to a large spool. The ribbons are tethers, lines that will prevent them (we learn from a tour guide addressing wide-eyed tourists) from flying around over Zambia and casting curses down on the locals.

But that's just a whimsical hook. The bright light that shines at the center of this movie is the mute 9-year-old orphan who, much to the dismay of the longtime spool-bound prisoners, is the latest to bear this cruel sentence.

Her name is Shula. Played by the radiant Maggie Mulubwa, Shula gives us no clues about her origin, unless her name is one of them: it means "uprooted," and it's likely that she comes to this town because she has survived some kind of trauma or abandonment elsewhere.

At the beginning, we see her making her way into a village, startling and upsetting a woman who is carrying water, which prompts a wildly unnecessary accusation that she must be a witch. The trial is a joke, with a local policewoman begrudgingly honoring local traditions and listening to others invent crazy stories about how they saw Shula flying overhead and disrupting them. (You may find yourself recalling the famous "Burn the Witch" scene in Monty Python and the Holy Grail.)

Shula's conviction makes no sense. It's maddening. But then it gets worse in a way that makes all kinds of sense: Mr. Banda (Henry BJ Phiri), a local who knows a good moneymaking ploy when he sees one, takes this convicted orphan on the road as an attraction. Shula, decorated in outrageous costumes, is forced to pick criminals out of lineups and even appear on a talk show, where a few in the audience dig for the truth only to be deftly deflected by Mr. Banda's dismissals. All the while, she stays bound to a spool, and often finds herself jerked violently backward out of a conversation and dragged a long distance on her back.

Yes, the leashes that bind these women are imaginary. But they're tied to real-world suffering: Nyoni prepared to make this movie by dwelling among "witches" kept in camps in Zambia and Ghana.

Is there anything here for American moviegoers? Or is this fictional Zambia — this strange world of wild costumes, bizarre traditions, and superstition — just an exotic spectacle?

Well, yes — let's begin with aesthetics: This is a beautiful movie. I watched it on a laptop screen, and I was enthralled by the performances, the beauty of the faces, the rich colors of the cinematography (by David Gallego, who filmed Embrace of the Serpent), and the stirring musical score. I wish I'd seen it on a big screen.

But I was also gripped by a sense of urgency. Will we Western moviegoers see ourselves represented by the foreigners in the opening scene who visit the prisoners the way they'd visit an exhibit in a zoo, and who treat Zambia as an exotic tourist destination?

I'd argue that there's a great deal for us to consider. You will find relevance here in your own ways, I'm sure. You might find that it's not really fantasy — not much, anyway. You'll remember the reality that many women in the world are still denied an education. You'll remember that many — even those a short road trip from your home — are fleeing persecution and violence only to find greater violence and injustice here, in "the land of liberty and justice for all."

Me, I laughed in bitter recognition at the darkly comic moments in Shula's story of being exploited by her patriarchal culture — and, specifically, by a political con man. Women are exploited, abused, oppressed, and trafficked all over the world, and America has more in common with Zambia in this than our current administration would ever admit — especially in these days when a Republican-led Congress excuses — yea, enables — an unrepentant sexual predator in his relentless attacks against women.

And remember, there's a young woman named Reality Winner held in solitary confinement for the crime of trying to warn the American people about efforts to corrupt our democracy: She told the truth, and Republicans sentenced her to prison for exposing their corruption. She's still there, on a leash, branded as a witch, even after everything she sought to reveal was proven true. Liars go free while a young truth-tellers suffers, with even her Bible taken from her for punishment.

Am I off on a political tangent? Or am I responding to art exactly the way I should — by considering how it illuminates fundamental truths of the world around me, and by finding in this experience the motivation to do what I can about what's in front of me? I can't save Shula, and I'm unlikely to influence what's happening in Zambia. But what can I do about those being branded here at home? What can I do about those criminals who cry "Witch hunt!" even as their crimes against humanity are exposed?

Despite the drastic differences between Shula's experience and my life of white male American privilege, I find that the more I think about this movie the more I feel its call for me to make a difference where I am. This is not a fantasy. It's not even a foreign film. It's about here and now — you and me.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=D_0NUA0aEpg

Booksmart (2019)

The praise party thrown for Booksmart had me wondering if Olivia Wilde's directorial debut might be the first high-school sex comedy to earn a Best Picture nod.

Then came the second wave: cries for critics to settle down, peppered with a few dubious complaints that Wilde's idea of high school was "unrealistic," especially in its idea that maybe we can all get along.

That sparked some snarky comebacks, but I'm not sure "the backlash to the backlash" ever became a thing.

So, the joint is almost empty now. Argumentative cinephiles have moved on, getting worked up about whether Jim Jarmusch's zombie movie is a work of genius or inexcusable laziness. And here I am, conflict-averse, and taking an hour-long break from grading finals for college freshmen. Why not step up to the Booksmart mic, long after the opening-weekend professionals have moved on, and share my thoughts with anybody who might still be listening?

I'm not here to stir up excitement: I won't hail Booksmart as a game-changer in its genre, nor will I dismiss it as derivative. But since I'm in grading mode, I'll go ahead and turn in a report card on several points: the movie's strengths and weaknesses and its most distinctive contribution to the genre.

Booksmart's Box-Office Blues

First, for the record: a few thoughts on Booksmart's box-office sufferings. I don't think this is "wilde" speculation:

Streaming media has made so much accessible — and free — that it takes a lot to get kids to leave their rooms (or their campus) and buy big-screen tickets. They smile at me politely when I serve up details about opening weekends, streaming options, and rental fees. "We know how to find it," they say. "We have our ways." And that, of course, is their way of saying they can find the movie for free on illegal back channels.

Few of my freshman undergrads buy good-old-fashioned movie tickets more than once a month, and when they do they're unlikely to see anything that doesn't have a big star in the lead. I asked 80 undergrads this quarter how many of them have seen Lady Bird, and only seven raised their hands. Many said they'd never heard of it.

What does inspire them? The promise of screaming at jump-scares with their friends. (A Quiet Place did huge opening-weekend business with my students.) The promise of revelations in a big-budget, special-effects-saturated franchise that they really care about, like Marvel or Hogwarts. (They buzzed about Endgame on a daily basis during the months before it opened, then went surprisingly quiet as soon as it arrived.)

So even though Booksmart seems custom-made to become their new favorite comedy, I don't expect to see many hands raised when I ask about it in September.

And that's a shame. It's better than so many movies they will see. It's about them and the things that matter to them most. And it would give us all so much to discuss.

Disclaimer: I'm Not Booksmart's Target Audience — and I Know It

I don't dislike teen comedies. I was a huge Better Off Dead fan in the '80s; I saw Heathers enough times in 1989 to be able to quote the dialogue as it played; I became an Emma Stone fan when Easy A arrived; Sing Street strikes me as very nearly perfect, a film I recommend to everybody all the time; and The Edge of Seventeen — while more of a drama than a comedy — is just outstanding.

Nevertheless, I approached Booksmart as I approached any teen comedy that advertises a focus on sex: with extreme caution.

I was hopeful. Nothing gives me more hope for the future of cinema than the increasing leadership of women in filmmaking and the increasing representation of neglected perspectives across culture, ethnicity, and gender. I was intrigued by the praise for Wilde's direction and by notes on Beanie Feldstein, who memorably made so much of a minor role in Lady Bird.

But I was also deeply skeptical. I'll talk about why, so stay tuned.

Here's my report...

What Works...

I was impressed from the opening scene by this endearingly enthusiastic duo. Amy (Kaitlyn Dever) and Molly (Bernie Feldstein) are naive and bookworm-ish, but they're not boring: they're irresistibly charismatic besties, and we want to see their bright lights get caught up in the swirl of their senior-class kaleidoscope. That's the premise: They're discovering, just before graduation, that they've made a terrible mistake. By focusing solely (and, perhaps, snobbishly) on academic excellence, they've missed out on fun.

And I'm rooting for them. My high school and college experiences were both joyously unpredictable adventures, full of academic rewards and the hijinks of hilarious relationships. I spoke at graduation and I planned my graduating class's irreverent and unsupervised talent show. I obsessed over my grades and I cornered my impossible crush in a moment of wild ambition to declare my undying love (to disastrous results). I want Amy and Molly to learn about more than earning good grades. I want them to laugh themselves sick at parties, to improvise their way out of trouble, to take risks and make moves on their first fierce crushes, to cast off their inhibitions and seize the karaoke microphone.

It's rare enough to see a female friendship in such sharp cinematic focus. It's even rarer for lead characters to be more interesting themselves than their supporting cast. Don't get me wrong — in Booksmart, we're witnessing the introduction of a whole new menu of young talents who will show up in great movies for years to come. The whole cast here is outstanding. But usually it's secondary characters and villains that make the strongest impressions in movies like this; they get to go to extremes, while heroes have to be stable and, um, "relatable."

As Amy and Molly, Dever and Feldstein could carry a franchise. They're dynamite.

Wilde celebrates all of it with consistently compelling cinematography and a perfectly pitched, carefully curated pop-music soundtrack. This movie is a fireworks show for the eyes and ears. As Amy and Molly pinball from one point in Los Angeles to another, we navigate their various vehicles, parties, disorientations, erotic entanglements, and awkward encounters with teachers and law enforcement without ever losing our place or struggling to sort out the large cast of characters. Each one arrives fully-formed, with a distinctive personality and amusing idiosyncrasies. While the highly praised pool party scene isn't nearly as affecting as the one in Eighth Grade, it's captured and choreographed with a gorgeous and delirious grace.

What Doesn't...

Here's where I'm uncomfortable with the film's fundamental premise:

It seems to suggest that the fun Amy and Molly have been missing equals sexual adventurism and very little else.

Yes, there's a karaoke scene about casting off inhibitions. Yes, there are encounters in which the girls and their classmates discover how much they've underestimated each other. But Amy and Molly's determination to find the biggest most popular party in town is quickly revealed to be a quest for sexual rites of passage. And, whether that was typical of your high school experience or not, that seems like an unfortunately simplistic aspiration for this otherwise extravagant and imaginative motion picture.

I've never had patience for films that take sex lightly — especially films pitched as entertainment for young people who (like adults, let's face it) too easily confuse their hormones and their heart. (And then there's wisdom, which neither hormones nor the heart are inclined to embrace without first making mistakes.) I saw too many young people who scoffed at the idea of restraint end up learning hard and even life-altering lessons. Socially awkward as I was, I wasn't dating in high school — not yet. Nevertheless, because of strong examples in my family, ideals illustrated in literature and art, and convictions cultivated by faith, I had come to hope for something more substantial, generous, and holistic than hasty carnal engagement. And I hated to see any of my close friends in high school treated as trophies or conquests, just as I hated seeing those who exercised restraint mocked as cowards or snobs.

Fortunately, I don't have many memories, good or bad, about sex being a major priority or a major problem among my classmates. Most movies about romance, sex, and love that were marketed to my generation seemed to have been imagined by writers who didn't know what they were talking about. Perhaps Booksmart's characters will seem familiar to you, perhaps not. I remember that my close friends and I were aware of that sex-obsessed-teen stereotype and made fun of it; we were just as interested (if not more so) in movies, music, and sports. And if were obsessed with anything it was a particular variety of comedy-one-upsmanship.

Whatever — it's one thing to represent typical teenage appetites; it's another thing to confuse those appetites with a moral compass. Insofar as that goes, there are aspects of this movie's conclusion that I can tell I'm supposed to celebrate, but instead I end up disappointed and less-than hopeful about these characters' future happiness.

Worst of all, the film's preoccupation with sex crosses a line when it draws teachers into its tale-spinning. I'm always happy to see Jessica Williams, and she's perfectly cast as Miss Fine, a Cool Teacher, here. At first she gives the film an admirable adult anchor: she seems wise, stable, and insightful about her students (much more so than the awkward but affable principal played by Jason Sudekis). But I'm not so happy to see Miss Fine become a punchline by giving in to the sexual proposition of a smitten male student.

Do I have to point out how audiences would have righteously rioted if the teacher had been male (and played by Kevin Spacey)? Maybe you'll find this particular twist amusing. I did not. But even if it makes us laugh, we need to note that we're being goaded into taking lightly a dynamic that, in the real world, leads to serious consequences.

Realistic? "Relatable"?

Don't get me wrong: I laughed a lot at Booksmart — more than I expected to. No, I can't join the hallelujah chorus: It doesn't have anything that inspired me as much as the non-conformist rage of Heathers or the contagious joy of Sing Street. But I don't find much cause for complaint, either: I enjoyed the company of Booksmart's characters, and I especially appreciate how generous and gracious it is with all of them. It has a refreshing lack of villains and a smart avoidance of scapegoats and stereotypes. (I've never seen Superbad, so I have no opinion about how this film measures up to it.)

Did I find it relatable? That's a word being thrown around by some of its critics, and it's also a word that my students use more than any other term to explain why they like something. The fact is, I don't care: I don't go to the movies to find something relatable. I go to the movie to experience other perspectives, other contexts, other ways of being in the world.

If the audience reaction I witnessed at my matinee of Booksmart is any indication, this is obviously familiar ground for most, and my high school experience qualifies me as a visitor from another planet. The only moments in high-school comedies that have ever felt even fleetingly familiar have come from the awkward social bonds formed between outsiders in Napoleon Dynamite; the joy of extracurricular creativity cultivated by the young musicians of Sing Street; and the struggle for spiritual authenticity in a context of self-righteousness and hypocrisy in Saved! So, no — I don't relate much to the characters in Booksmart. They're too cliquish, too sex-obsessed, and — in most cases — too wealthy for me to recognize their world.

But I do relate to it in another way. I love the way this movie loves its community.

Me, I loved high school, I loved my classes, my classmates, my curricular and extracurricular activity. I enjoyed the company of almost everybody in my (very small) class (of about 60). And when I graduated, I didn't want to say goodbye to anybody. In the video of our final moments, we are celebrating in the hallways with wild abandon. But we are also in tears, our arms around each other, distraught at the thought of going our separate ways.

So I guess that I'm grateful that, for all of these characters' preoccupations with getting laid as if it's the Meaning of Life, Booksmart plays with such heart, such an inclination toward empathy, and such a determination to liberate each and every teen character from the constraints of typical categories and stereotypes. Like Napoleon Dynamite, this is a movie full of individuals, of human beings, not types.

And while the movie prioritizes delivering a kind of sexual "graduation" for its characters so highly that I found myself getting impatient, I'm glad that it ultimately ends up caring most about its central friendship — much the way that Lady Bird (which I find much more rewarding than Booksmart) ends up caring most about its central mother/daughter bond.

I can only hope this movie will inspire this kind of inclusivity, welcome, and grace — not only in future stories told in this genre, but in its target audience, the one growing up in a world that is increasingly dividing into judgmental, vindictive camps. After all, I learned to value grace by burying my nose in books. I hope more movies will make it possible for upcoming generations who show an alarming disinterest in reading.

Thanks to the Looking Closer Specialists — including Laura Hittle, Bob Denst, and Kimberly Fisher — for their ongoing support of my endeavors on this website. I could not afford to write and publish these reviews for you without donations like theirs.

If you are grateful for my work on this site, consider making a donation of any amount here. All donations cover costs of resources that make my work on this website possible:

Her Smell (2019)

Walking SeaTac International Airport earlier this month, I heard the voices of rock-music legends on the intercom issuing cautions about airport safety. For example, Jerry Cantrell of Alice in Chains told us that no smoking is allowed in the airport. And then — I am not making this up — somebody from Guns N'Roses instructed us in how to navigate the airport escalators safely.

With quick-draw reflexes, I reached for my phone and reported this travesty on Twitter:

Hey, hey... my, my...

Rock-and-roll just up and died.

Perhaps my reaction was too harsh. It was certainly hasty. But it hurts when icons of bucking the system become, well... the system.

My love of that early-'90s Seattle sound lives on. Of course it does. It was the hometown soundtrack of my college experience. It was the rebel yell of those most formative years. Since the grunge wave, I've heard a hundred rock bands rip off Nirvana's "Smells Like Teen Spirit" riff, and every time the imitation is both obvious and annoyingly inferior. But my aggravation with the copycats isn't driven by nostalgia — it comes from a longing to hear new ideas and authentic voices. The heart of any great rock-and-roll beats with a legitimate longing, a distinctive vision, a righteous rage against hypocrisy, a demand for something more real than pop-music superficiality.

I feel like I found a pure dose of the real thing — a cinematic equivalent of Nirvana's Nevermind —this week.

Her Smell, the new film by Alex Ross Perry, flips the Kurt Cobain coin to show the other side, revealing the woman behind the throne — or, rather, the woman who owned a throne of her own and demanded (yea, deserved) to reign alongside her Prince Alarming. But Courtney Love was a She, and so her public refused to attend to her intense volatility with the patience that they showed her similarly mercurial male contemporaries. She was an "emotional mess," according to the press — but Cobain was a "tortured artist." Okay.

Ah, but I'm misleading you. Her Smell isn't about Courtney Love — not exactly. Perry conjures a character named Becky Something who, while obviously inspired by Love's famous attitude and antics, is better for being a fiction. We are released from the burden of arguing about historical accuracy, set free to imagine a mythical diva, a tempest in a t-shirt. Played with hell-bent fury by Elisabeth Moss, Becky looms like a representative spirit of so many women in rock, so many troubled icons, so many who somehow evade the many possible Deaths By Recklessness that seem imminent and even invited.

And, fortunately for us, the movie is also more than an invitation to witness a great actress indulge in self-destructive behavior. What could easily have just been another unpleasant exercise in what I like to call Stunt Acting — the kind of awards-bait performance that suggests Most Intense Acting equals the Best Acting — becomes instead something surprisingly substantial: a soulful examination of a whole community — the network necessary for the making of a Rock Goddess.

Her Smell, giving generous attention to a solar system of supporting characters all caught in Becky Something's orbit — longtime bandmates Marielle (Agyness Deyn) and Ali (Gayle Rankin); potential next-generation collaborators (Cara Delevingne, Ashley Benson, and Dylan Gelula); a husband (Dan Stevens) trying to save both Becky and their daughter; Becky's mother (the great Virginia Madsen) — is an outstanding ensemble piece. It takes a village to raise up a Star, but if the village isn't careful, that Star might come crashing down like a meteor and leave a smoking crater in their place.

Her Smell asks if we dare empathize with a woman so self-immolating, disrespectful, egomaniacal, and dangerously intoxicated. Rebecca Adamczyk — that's the name Becky Something is trying to put behind her — is an open wound that bleeds hard rock gold — but only on occasion, and, increasingly, only when it seems she's alienated everyone that matters and pushed her agent (Eric Stoltz, excellent) to the edge of his patience. She craves the stardom, and when she gets it, she believes the hype — perhaps because there's a smoking hole in her heart left there by...

...whom?

While it's clear that Becky Something, who provides an energetic catharsis for so many, exists at great cost to those around her, it's also clear that her animating energy is a response to betrayals, abandonment, and abuse. The film's most notable ghost is Becky's father, who is rarely mentioned, but whose absence thunders like the bass through the ceiling and walls in these purgatorial nightclubs. She's turned hurtful because she suffered formative hurt at the hands of someone she should have been able to rely on, and she won't risk giving anyone that kind of dangerous influence — the power to hurt her — again.

But the movie never devolves into a blame game. There are moments mid-tantrum when we fleetingly glimpse Becky's awareness of what she is doing and her helplessness to stop herself. It's obvious that the band's ship is sinking, thanks to Becky's sabotage. And her behavior suggests that she'd rather throw her her shipmates overboard then allow them to run for the lifeboats — which is to say, she'd rather fire them than allow them to quit.

Nevertheless, all might not be lost.

After we weather Hurricane Becky through the storm of the film's first 90 minutes, we might come to believe that even an imperfect community — one as prone to exploiting her as it is to helping her — might be enough to save her from herself. Much to my surprise, the film's last act dares to entertain the idea of hope. It isn't an implausible happily-ever-after hope; it's a hope that scares everyone involved, given its fragility and unlikelihood.

If it weren't for the uniformly remarkable cast (Deyn and Rankin are both extraordinary, and even Amber Heard is impressively convincing), and the masterful choreography of complicated scenes in claustrophobia-triggering clubs, corridors, and studios, I might not have made it through this movie.

But in the end, I'm glad I did. As I was watching, I had to ask if the horror I felt was an aversion to the film's merciless ferocity, or if it might instead be a kind of discomfort with the challenges that the film was posing to me:

Could I find a way to love someone so recklessly dangerous, destructive, and self-destructive as this?

What does love require in such a scenario?

Would I be willing to stick with her, one way or another, during this downward spiral even if there were no hope of her recovery?

God have mercy on the Becky Somethings of the world.

May they outlast their own kamikaze impulses.

May they be granted the grace to survive the trials that wring such vivid music like blood from their guts.

May they live long enough to leave us recorded testimonies about how to ride our own escalators safely.

Thanks to the Looking Closer Specialists — including Timothy Grant and Winston Chow — for their ongoing support of my endeavors on this website. I could not afford to write and publish these reviews for you without donations like theirs. If you are grateful for my work on this site, consider making a donation of any amount here:

Aretha Franklin, Beyoncé, Sam Phillips: Three New Concert Films

I’m under headphones above 10,000 feet, and Aretha Franklin is flying the plane.

At least it feels that way. Anne and I are headed to what we call “a homecoming,” an annual gathering of authors at the edge of the Frio River in the Texas hill country — inspirations, influences, kindred spirits. I’m feeling a familiar anticipatory buzz of gratitude and hope. I will see so many of my favorite writers in person there. Oh, I can read their profound manuscripts all year long, but there’s nothing like being in their company. It is medicine for my weary heart.

So it feels right that I’m listening to Amazing Grace: The Complete Recordings, an audio record of a homecoming in which “the Queen of Soul,” at the apex of her ascent to pop-music celebrity, suddenly returned to the context of a community church — New Temple Baptist Church in L.A.’s Watts neighborhood, to be exact — to sing among fellow believers the songs that had lit a soulful fire within her when she was a child.

I’m hooked on this sound. I’ve been flying high since my discovery of a new documentary — also called Amazing Grace — about those two nights of live music in 1972 when director Sydney Pollack set up cameras and microphones to capture this convergence of songs and sermons inside New Temple. It’s such an unlikely big-screen experience: Footage of these legendary hymn sings has been unreleased for almost half a century due to technical challenges of matching image and audio, and Franklin herself apparently opposed its release. But here it is, in theaters. And when you see it, when you hear it, you’ll know why it’s an unexpected arthouse hit. You’ll know why I returned to the theater to see it twice in one weekend.

This movie may look at first like an invitation to worship Franklin herself, but that’s not the nature of the experience: Amazing Grace is about the ecstatic play of Franklin, the Reverend James Cleveland (her childhood friend), the Southern California Community choir, the congregation, and I daresay — for those with eyes to see and ears to hear — the Holy Spirit. They show us a community finding release from the weight of prejudice, from the trauma of the recent Watts riots, from the frustrations of an emancipation promise proclaimed but unfulfilled. And they find that release through music about God’s longsuffering faithfulness. It’s clear that thought their hearts, though bruised and beaten, have not been overcome.

If you, like me, have felt weighed down in recent years by emboldened forces of hatred in this country and the world — open attacks on any American vision that values “liberty and justice for all” — then this homecoming will bless and console you, too.

The timing of this release is interesting. Though these early-70s echoes are significant — as a vital historical artifact, as a crucial cultural testimony for black Americans, and as unparalleled expressions of Gospel music — they’re not the only sounds elevating me.

While the airplane hums, I’ve enhanced my “homecoming” playlist with tracks from two more concert films. Both reveal singer-songwriters at their peak; both spotlight women of singular artistic vision; both document highlights from multiple shows with career-spanning setlists.

Just this week, I’ve witnessed, with slack-jawed amazement, Homecoming: the new Netflix film capturing the colossal spectacle of Beyoncé’s 2018 Coachella performances. So I’ve downloaded the 40-track album that accompanies the film to relive that excitement.

And I’ve also been enchanted by the intimate art onstage in Sam Phillips: Live @ Largo at the Coronet, a film of my favorite songwriter performing with an all-star ensemble of musicians at the top of their game.

An outdoor arena, a nightclub, a church — these three events couldn’t be more different.

[To read the rest of this essay,

visit Good Letters at Image.]

High Fidelity (2002)

Lately, I've been blasting the new album by Said the Whale during my morning commute. And this track has made me nostalgic for the endless hours I used to spend browsing record shops.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nujekGBgK1U

It's also made curious to revisit a movie set in a record shop that I admired almost twenty years ago now: Stephen Frears' adaptation of Nick Hornby's novel High Fidelity.

Before I do, I'm revisiting my review, just to refresh my memory about the conversations and arguments that went on in the hours and days after the film's release. And I'm amused by several things:

- I identified Jack Black as "an ever-present supporting actor in Tim Robbins' films." Little did we know that he would become a comedy superstar on a variety of stages.

- I really believed that we'd get a sequel to Grosse Point Blank. I still wish we had.

Here's the original review:

[This review was originally published at The Phantom Tollbooth.]

"Did I listen to pop music because I was miserable?" Rob Gordon (John Cusack) asks, "Or was I miserable because I listened to pop music?"

Good question.

Rob is a thirtysomething record-store manager and part-time DJ in downtown Chicago who has reached a point of introspective crisis. Yet another girlfriend is breaking up with him. He doesn't know why, he's broken-hearted, and worse, he's fed up with being rejected. When his live-in lover Laura (played by Danish actress Iben Hjejle) packs up and ships out, he decides to get to the bottom of this perpetual misfortune once and for all. He sets out on a journey back through the infidelities and disasters of his romantic history.

The journey has two parts: a swim in the sea of self-pity as he listens to the music that formed the soundtrack to his love life, and a frantic interrogation of past girlfriends in hopes of reaching enlightenment.

I get the impression Cusack made this film chiefly so he could advertise his favorite records to the world. Music—specifically, vinyl—is Rob’s life. From the first moment of the film, the records are spinning. His apartment walls house thousands of LPs in plastic sleeves, carefully organized autobiographically, in order of their significance through the course of his life. He's a walking pop-culture encyclopedia, also a master of the fine art of making compilation cassettes, and an obsessive list-maker. He is unable to carry on a conversation about anything or anybody without referencing the music he associates with the subject. He lists for us his Top 5 heartbreak songs (yes, he talks to the camera between chapters, and even during scenes) as he describes his Top 5 breakups. Katrina and the Waves, the Pretenders, Pavement, Bruce Springsteen, Marvin Gaye, Massive Attack—endorsements of his favorites shout out from the screen at every turn. You can expect a run on the recordings of The Beta Band after this movie opens; Rob plays their stuff in the store and stands back to watch the customers (and the audience) catch on.

Music is the one thing Rob understands, and so he’s most eloquent (and understood) when he’s with others who speak the same language. Thus, while he wishes it were otherwise, Rob’s closest confidants are his slacker Championship Vinyl co-workers. Through long and feverish debates about personal taste, we come to know Dick (Todd Louiso), a small, softspoken, and sensitive guy who listens to Belle and Sebastian; and Barry, a Chris-Farley-like Tasmanian devil who likes obscene lyrics and thrashing guitars (Jack Black, an ever-present supporting actor in Tim Robbins' films). Barry's crass sense of humor and explosive temper win him arguments with everyone but Rob, who calls his bluff when things look to turn violent.

The storytelling slows to a standstill in these scenes, and Barry’s over-the-top behavior gets too much screen time. But the chemistry of these three is certainly entertaining, and audiences are sure to leave with a title or two to look up next time they visit a music store.

Aside from his search for enlightenment in musical nostalgia, Rob hopes to get some answers from the experts themselves. His ex-girlfriends (played by Catherine Zeta Jones, Lili Taylor, and Joelle Carter) are a gallery of extremes. And perhaps they have more to say on the subject of his incompatibility than he bargains for. Flashbacks show us Rob "on the make" at all different ages. Of the three exes, Carter struck me as the most convincing, while Zeta-Jones is cold and glamorous and Taylor merely spooky. Lisa Bonet, in a performance that should win her an invitation back into the Hollywood spotlight, arrives as a possible new romantic adventure, but serves in the end only to demonstrate just how selfish and reprehensible Rob can be. After all, here’s a guy who’s broken up because his girlfriend might be unfaithful, and he worries about it while he himself sleeps around.

Not that Rob's precious Laura is a paragon of virtue. In fact, she has teamed up with a new man—a grotesquely Yuppified neighbor named Iain (Tim Robbins). Robbins makes Iain the most memorably disgusting character since John Turturro's hyper-arrogant bowling champion in The Big Lebowski. As his only function in the story is to provoke jealousy and grand romantic gestures from Cusack's Rob, Robbins has a lot of room to embellish his character, and what he does earns the biggest laughs in the movie.

Rob's pursuit of Laura and his pursuit of self-awareness lead him to some hard realities, and he sinks deep before his climb to understanding. These characters, as winning as they are, strike some frightening and mean-spirited blows to each other. We learn about all manner of infidelities and even an abortion. The days of the cute Cusack dating comedies are over. But the story does not get sidetracked by melodramas that would have proven irresistible to other directors. It stays focused on Rob, on what it is that disqualifies him from long-term relationships.

John Cusack was born to play a self-defeating champion of unrequited love. He's walking a career path within shouting distance of Woody Allen there. And he's got that sarcastic but well-meaning voice down so well that he's writing his own scripts. He wrote his best film, Grosse Point Blank, with D.V. DeVincentis and Steve Pink, and that same team adapted High Fidelity. (He’s also talking about a sequel to Grosse Point Blank.) In my opinion, only Woody Allen has mastered the art of "knocking down the fourth wall" and addressing the audience directly. It's tricky. Here, Cusack's persistence makes it work most of the time, and his monologues give him a chance to show off Chicago’s scenic spots. But characters that interrupt an otherwise convincing scene to explain something to the audience only remind the audience that this is a movie, and the intensity of a real situation gets spoiled. I wish there had been less talk and more show. The music explains enough as it is.

There is also far too much rain in this movie; it arrives like clockwork whenever Rob gets rejected, just so he can walk home looking like a wet dog. I kept expecting to hear the classic Police refrain—"I've stood here before inside the pouring rain / it's my destiny to be the king of pain." That, at least, would have been clever.

But these are small complaints. This film is what they call "a return to form" for director Stephen Frears, who showed us a corrupting combination of lust and power in Dangerous Liaisons and found wry laughter in painful circumstances in The Snapper. His ability to make something meaningful and memorable out of such different explorations is truly impressive. (Maybe audiences will now forgive him for Mary Reilly.) He helps Cusack and Company transplant Nick Hornby’s novel from London to Chicago quite successfully. And by refusing to glamorize Rob’s romantic antics, he steers clear of romantic comedy conventions without sacrificing relevance.

Best of all, Iben Hjejle makes Laura the strongest, most interesting leading lady in many a romance. She's fiercely intelligent even though she makes rash and hurtful decisions. Most importantly, she's immune to grand gestures of romantic superiority from the leading man. The leading ladies in most romantic comedies exist to exhibit weakness so a man can come along and save them with intelligence, cleverness, or brawn. Laura is flawed and vulnerable, but she’s also formidable, and if she goes back to Rob it will be because she has come to that decision on her own terms, and for that she wins our respect.

The more I thought about it afterwards, the more I realized just how much convention the film defied. It's a comedy, so of course things will turn out okay, one way or the other, in the end. But High Fidelity refuses to tell you why things will turn out alright. Laura's "womanly wiles" are as mystifying to the males in the film as they would be in real life, so Rob never discovers any big secret to winning her back. He just keeps wrestling with his personal demons. And that itself is a worthwhile story. While he may never come to understand or change his girlfriend, he can certainly learn to change himself. Instead of "happily ever after," we’re left with a new beginning, a possibility of renewal. Even as I wondered why a smart girl like Laura would be interested in a slacker like Rob, I knew that guys throughout the audience were nodding and smiling, quite familiar with such unanswerable questions. And the women were smiling too, keeping to themselves the reasons that they are sometimes drawn to thick-headed, oafish, and insecure men. C'est la vie.

Ash is Purest White (2019)

These aren't your everyday gangsters.

"Righteousness and loyalty" — that's the code of the jianghu — a particular underworld of apparently 'principled' Chinese mobsters and street thugs run by a devious but respected player named Bin. And why shouldn't he earn the locals' obeisance? The Chinese government doesn't demonstrate any reliable concern for their own people. If the working class needs to get something done, they'll turn to someone who gets things done. Just watch how, in the opening minutes, Bin quiets an escalating clash between bickering men in a fight over money, then turns his attention to cleaning up a housing development that is, he's told, "haunted." Resourceful guy, and more reliable than China's sovereign powers.

And there, at Bin's side, whole-heartedly devoted, is his girlfriend Qiao. Look at how she has absorbed her privilege, Bin's favor, all the way to her bones, so that she slinks and slides and struts with the confidence of a cat through Jianghu Land. Watch her spin through the center of Bin's dreamy dance club, where mobsters and their molls celebrate their glory days singing "YMCA": "They have everything for you men to enjoy / You can hang out with all the boys...." Watch her surprise the back streets of a troubled community where the needy poor approach her like royalty. In her glamorous costumes, she flaunts her freedom to make decisions in Bin's name. And she would laugh if you told her how quickly it will all fall apart.

This is how Jia Zhangke's latest film Ash is Purest White begins — like a flashy hybrid of Wong Kar-Wai's kaleidoscopically exhilarating expressionism and Martin Scorsese's gritty gangster dramas of the '70s and '80s. But we have a long way to go, and we're about to veer into a subtler and more challenging kind of drama, an intimate and interior struggle that serves as a poignant portrait of political desperation. And you might even be reminded, as I was, of how Krzysztof Kieslowski, in Blue, drew us down into the continental shift of a woman's heart during a season of loss.

Qiao is the central character of this epic story, which is as much about how China has changed over the narrative's 17-year span from the early 2000s to tomorrow. We follow Qiao's precipitous fall from privilege into prison, and then into... what?

If this is about "righteousness and loyalty," what does the arc of Qiao's story suggest about the rewards of such virtues — of the lack of them?

I mentioned Blue as a reference point, but only as a way of praising Zhao Tao's extraordinary performance. She gives Qiao the same kind of unspeakable interior complexity as Juliette Binoche's Julie.

In many ways, this character's arc is the opposite of Julie's. Both begin in the confidence of a relationship, both are catapulted out of that confidence when a long drive ends in calamity. Both are devastated, and suffer a long purgatorial grief. Both are worried about ailing parents who are free-falling into despair as their worlds fall apart. And both are jarringly awakened to betrayals and the realization that what they thought they had was not at all what they thought they had. But where Julie was independently wealthy and responded to trouble with a flight into solitude, defiant independence, and indulgence, Qiao is desperate to restore her connections, rekindle her love, re-establish her partnership and power, and — most importantly — find the resources to merely survive. For both Julie and Qiao, Another man will emerge as a possible new partner, but these new suitors couldn't be more different in what they offer and represent. Where Julie's is a story of a begrudging turn toward new possibilities and healing, Qiao's is one of demanding "righteousness and loyalty" even though the man who taught her that code has no intention of fulfilling it. She seems doomed to suffer, driven to delusion in her adherence to a code that no one else believes in.

Zhao traverses this difficult and dramatic character arc without overplaying a moment. Over the film's three chapters, she convincingly ages Qiao from being Bin's feisty, sexy girlfriend to suffering as a bedraggled prisoner to raging as a jilted lover to despairing as an embittered caretaker. Her harrowing silences and penetrating stares suggest subterranean turmoil — which is appropriate, given the title, and given the important scenic backdrop: a lush, green, dormant volcano that eventually turns dull as a cinder. She's amazing.

But this isn't just melodrama. Qiao's journey is strange for the ways in which it zigzags between the violent beats of gangster stories, the angst of troubled historical romances (Cold War), flirtations with science fiction (like Jia's own Still Life), and not-so-subtle political commentary.

At IndieWire, David Ehrlich calls this "a loveless love story," and it often feels that way — Qiao's devotion to hard-hearted Bin is a puzzling mix of materialism and madness. She tries to leverage her privilege to provide hope for her poor, bitter, working-class father, whose failures and disillusionment take the shape of rants against injustices toward workers, but she will become a similar crutch for Bin himself, as his seeming-sovereignty comes to ruin. In both situations, it's hard to see how either man's yearning for strength is a cause worthy of Qiao's resilient service, given their disrespect and disregard for her.

Things become surreal before her journey is over. But the two questions that keep rising to the surface — for both Qiao and for the Chinese people — are exactly those of righteousness and loyalty: By what code do you measure righteousness? To whom have you pledged loyalty, and how is that working out for you?

While this ambitious and unusual epic from Jia Zhangke didn't quite sustain my suspension of disbelief all the way through, it has some incredibly compelling and unexpected sequences realized within a mis-en-scene of murky colors and pulsing music; panoramic (and heavily symbolic) scenery; vast and heavily populated sets; a terrifying and spectacular attack during a night drive.

What's more, it has one of the most intriguing third acts of any film I can recall.

And I cannot explain why it haunts me without getting into some substantial spoilers — so, proceed only if you have seen the film.

In Part Two, Qiao endures her prison sentence until she is set free and finds no one waiting to welcome her.

She goes looking for Bin, but the world has changed too much — most vividly evident in the rise of the new Yangtze river and how it has wiped out a whole world of families, homes, and traditions dating back centuries for the sake of money and tourism. What little money she has left and her ID are stolen — that is, her neighbors won't hesitate to erase who she really is, and she won't find any help. When she tracks down Bin, he's risen above the realities of life on the street, and he's with a younger woman. He's also a coward, too terrified to face his past.

This exposure of Bin as a fool and an opportunist feels like a larger referendum on Chinese leadership as delusional, ignorant, and heartless. Note Qiao's desperate scheme for stealing money from unfaithful, conniving rich guys: The trap in the trick involves confronting them about mistresses they've neglected while their families celebrate in the next room.

When Qiao does finally find Bin, what follows is a scene of regret, unfathomable grief, and honesty so raw that I found myself expecting to find Qiao waking up from a dream. The dream-like quality isn't easy to shake; it feels like a fantasy inspired by In the Mood for Love.

As we watch Qiao awaken to the hypocrisy of the system on which she bet everything, she seems utterly lost. So we believe that she might make one last desperate gamble, running away with an opportunistic con-man, a child of capitalism, who is just as much a fraud as anybody else. It's the only way she knows to succeed. We have to wonder if she's isn't so helplessly dependent that she cannot imagine a life anywhere but at a man's side. Perhaps she was never as capable and as successful as she thought she was.

Ultimately, it strikes me as a bold critique of a government that relentlessly abuses a gullible and almost-helpless people, leaders who make promises they never intend to keep, who exploit and neglect the working class, and who constantly strive for a superficial form of success that traumatizes and burns its disillusioned people like fuel. Once again, Zhangke sets the story against the troubling historical backdrop of the Yangtze's rising waters: the government's devastating, money-driven decisions, and the sufferings of the poor who are driven like desperate cattle back and forth across the country in search of work and security. But it doesn't feel redundant; this is a very different story than what we saw play out in Still Life. This film goes so far as to suggest that the people have to hope that local gangs will take better care of them than the government, even as it exposes the hollow heart of toxic masculinity.

And when she steps off a train under the night sky and witnesses something that suggests that this movie might not fit the genre we thought it was, another possibility entirely opens up.

One thing I haven't read in any review — perhaps you have, and if so, please send me a link — is the possibility that all Part Three isn't actually happening at all except in Qiao's crumbling imagination.

How likely is it that she climbs back to the top of the crime world and becomes a sort of Godmother to the same community of crooks that Bin once ruled?

How likely are they to respect her as the queen she thought she was when, in fact, she was a disposable agent who failed to preserve Bin's vanity?

How likely are those crooks to be in the same place, in the same balance of rivalries, so many years later?

Are we supposed to remember that these high-rises were described, early in the film, as "haunted"?

If this is all really happening to Qiao, then why, in the last shots of the film, does the building — and even the neighborhood — seem deserted, with Qiao being watched not by neighbors but by unattended surveillance cameras, what's left of her life burning away in the deathly white glow of a digital display?

I'm inclined to think that this most tragic of interpretations is also be the most likely. It only enhances and strengthens the film's political commentary and the depth of the loss at its center: the destruction that comes from believing what men in power tell you, and from setting your hopes on the financial rewards of bargaining with the devil.

Love & Revelation: a 'magic hour' with Over the Rhine

[Banner photo by Kylie Wilkerson.]

Photographers know a particular vocabulary of light beyond daytime and nighttime. They know those luminous in-between times called “magic hours.”

In evening's "golden hour," the sun is so low that the world forgets to cast shadows, and everything goes woozy with red, glowing it seems under its own power.

By contrast, evening's "blue hour" shines after the sun is gone, cooling in an elegiac blue, the world catching and holding as much indirect light as it can. Bob Dylan might say, "It's not dark yet / but it's gettin' there."

Language about light and photography has come up a lot in the lyrics of Over the Rhine over their three decades of recordings. But if we were to organize their music into phases of the day, we’d find much of it — perhaps most — belongs to evening's blue hour: songs for times when dreams are being surrendered, when we're left with only distant reflections of light.

Their 2001 release Films for Radio begins with thoughts of an ending:

If this should end tomorrow —

All our best laid plans

And all our typical fears —

Am I running out of lifetimes

This is not the first time

Something ends in just tears…

Not the first time, indeed. On an earlier record, fan favorite Good Dog Bad Dog from 1996, they began with a lament for broken dreams: “What a beautiful piece heartache / this has all turned out to be.” The Long Surrender, an album released 15 years later, began with the sobering observation that “Everybody has a dream / that they will never own,” but also the assurance that “If we gotta walk away / we gotta hold our heads up high.” Over the past several years, the climax of their concerts has come with an anthem of the sort that audiences sing along with, their hearts in their throats, their voices breaking: “All my favorite people are broken / Believe me, my heart should know / Some prayers are better left unspoken / I just want to hold you, and let the rest go….”

The great Presbyterian minister Frederick Buechner once wrote, 'The place God calls you to is the place where your deep gladness and the world's deep hunger meet." By that definition, Over the Rhine's gladness is to sing for (and of) dreamers discouraged, for those who must surrender although they strove and strove, for those who have seen beauty abused or torn down. Call it Blue Hour Music. Call it empathy. Call it the laughter of recognition or call it consolation. These might be songs for marriages or friendships that just won’t make it, artists who can’t cover the costs of their visions, believers who lose their grip on faith — even Americans who find a nation's foundations sinking beneath the rising tides of lies, fear, and hatred.

Whatever troubles that Karin Bergquist and Linford Detweiler are soundtracking, they're not faking it. They know the territory and speak from experience. In 30 years of making music and 22 years of marriage, they’ve been through things and lived to tell the tale. You can map their personal hardships by the quietness of their records, as if they’ve played and sung more tenderly, more gently, when the hurt has been especially raw. Good Dog Bad Dog was released in a time of uncertainty that the band would even continue; Drunkard’s Prayer came together as they fought to save their marriage from coming apart.

And here they are with their quietest record for what may be the hardest times their audience has known.

Love & Revelation, their 15th album, might play as the soundtrack for a movie about personal losses set against the roiling backdrop of this present American darkness. They sing psalms over intimate hurts and raise prayers for those still standing at the end of the world; they grieve our losses and horrors; and they invest in a hope beyond the human sphere. And, as they asserted on 2013's Meet Me at the Edge of the World, these magic hours are their “favorite time of light,” a twilight when we count the cost of the day, but also an hour of enchantment, when we might sense more possibility in heaven and earth than we have yet dared to dream. Against a backdrop of blue, the flare of a torch or a candle can seem otherworldly.

In an interview with Justin Chadwick at Albumism, Detweiler — the responses seem to come primarily from him, but the article doesn't specify — offers some context for these songs:

We’ve lost loved ones. We’ve seen our friends struggling with loss—the loss of a child, or partner. We’ve stood with friends and family members as they struggled with chronic illness, or a scary-as-hell cancer diagnosis.

…

And then we know a lot of people turn on the news and are in shock at what they are seeing. Beneath that shock is grief. We are grieving the fact that we aren’t quite sure who we are anymore as Americans. Things are shifting and being revealed. Maybe we are grieving the fact that we thought we were better than this.

No wonder it begins with "a beautiful piece of heartache." The song "Los Lunas" — can a place have a name that sounds sadder? — could score a short film as a heartbroken lover, a friend betrayed, or a devastated dreamer drives New Mexico's I-25 at dusk:

I cried all the way from Los Lunas to Santa Fe

And on to Raton

Neither one of us wanted things to end this way

But one of us had to be wrong...

Following this lament for loss, the car slows down along a path called "Given Road," and stops at the edge of a property walled off from visitors. Someone has shut out the world with a barrier that “keeps out the sun / keeps in the cold.”

As if inspired by these grievances, two voices unite on the third song, "Let You Down," not to raise walls but to offer embraces, to make promises and offer a blessed assurance:

Don't know if we can roll away this stone

But either way, you're not alone

And if a song is worth a thousand prayers

We'll sing 'til angels come carry you and all your cares

I don't want to let you go

That's the one thing for sure I know

You can bet I’ll stick around

‘Cause I don’t want to let you down

Are they singing to each other? Is this an offer of reconciliation to the one lost behind the wall of "Given Road"? Whether you take each track as a standalone story or as a chapter in an ongoing narrative — either way, it works. And regardless, I can’t help but take each track personally, these lines magnetically adhering to my own fears, my own hopes, my own relationships.