Overstreet Archives: Anchorman (2004)

A Look Back to When Ron Burgundy was "Kind of a Big Deal"...

As I listen to (and enjoy) the new Ron Burgundy Podcast, I'm reminded of conversations I had with Steven D. Greydanus and Paul Chattaway back when Anchorman first hit theaters in July 2004, and when Christian readers objected to my positive review of the film. The best apologist for Ron Burgundy turned out to be, strangely enough, G.K. Chesterton. I posted about that here.

What follows is an abridged, edited amalgam of my original Christianity Today review of Anchorman and the expanded version of that review that was then published.

I find it amusing now to see how hard I worked, and how formal I sounded, in trying to preach the Gospel of Ron Burgundy to Christian readers. But today, I find that Anchorman remains one of my all-time favorite comedies. My appreciation of its strengths deepened over the years as I revisited it again and again.

Will Ferrell is one of those comedians. Some people "get it." All he has to do is stare poker-faced into the camera, and they start laughing. Others "don't get it," and think he's just trying to be offensive or annoying.

Anchorman: The Legend of Ron Burgundy will do nothing to change that. Farrell's fans will enjoy 91 minutes of what they'll consider uproarious comedy, while others will again be repelled by his brand of buffoonery.

The Genius of Will Ferrell

To trace the history of bawdy humor, you'd have to investigate literature as timeworn as Chaucer's Canterbury Tales and beyond. Writers as prominent as Shakespeare, Chesterton, and even C.S. Lewis appreciated risqué humor, so long as it was artfully delivered.

Television's Saturday Night Live has been a factory of bawdy humor for decades. Most of it has been crass, cheap, and even mean-spirited. But occasionally, it has been sophisticated, and has helped us avoid taking ourselves too seriously. Further, it has sometimes poked fun at things that needed to be laughed at. Dan Akroyd and Steve Martin made a mockery of swinging '70s bachelors with their "wild and crazy guys." Mike Meyers lampooned the inappropriate sexual recklessness of James Bond in his Austin Powers series. And a few years back, Will Ferrell poked fun at brash, libertine sexuality with a series of hot-tubbing skits.

Now that Ferrell's conquering the big screen, he's bringing his own brand of bawdiness with him. And it's my responsibility as a critic to inform you, much of the humor in Anchorman is off-color, sophomoric, and just plain dirty.

But, in the name of full disclosure, I must also admit that my funny bone gets clobbered almost every time Ferrell opens his mouth.

I've liked Farrell from the moment he stepped into the big shoes of Phil Hartman as the most talented all-purpose character actor on the show. When we watched Will Ferrell, we got something different every time, something unpredictable. Unlike Mike Meyers or Chris Kattan or Adam Sandler, he never winked at the audience. He focused on the character, and gave us a whole host of unforgettable buffoons: the bearded organ player, the uninhibited cheerleader, brilliant caricatures of President Bush and In the Actor's Studio host James Lipton.

My favorite character, though, appeared only once. Ferrell appeared as an anchorman who lost his mind and his conscience when the teleprompter broke. When that happened, he and his news team revealed that without the teleprompter, they were nothing more than imbeciles and, in fact, savages. By the end of the news cast, they had degenerated into beastly noisemaking and killing each other. It was absurdly over-the-top. SNL had never taken a skit to such shockingly funny extremes since Dan Akroyd's famous Julia Child sketch.

These skits established Ferrell as one of the greats, up there with Phil Hartman, Chevy Chase, Dan Akroyd, and frequent guest Steve Martin. He belongs in that pantheon because he has his own distinct brand of comedy, something that sets him apart from other SNL alumni. Ferrell's portrayals are funny because he's exposing commonly idiotic behavior by exaggerating it. Ferrell's characters, from SNL to Elf, have one thing in common — they believe they understand how the world works, but they don't understand it at all. Thus, they are completely unaware of every faux pas they commit. And when something suddenly awakens them to the truth, their righteous anger is even funnier. (Who can forget that great moment in Elf, when our poor Christmas hero realizes that a department store Santa is not the real Santa, and he roars, "You sit on a throne of lies!"?)

Unlike Robin Williams' famously obscene standup comedy, Ferrell's comedy is not indulging in the crass in order to make us laugh. It's drawing our attention to the humiliating realities of ego and self-absorption. He's not condoning his characters' behavior; he's highlighting the lunacy of it. We're not laughing at the expense of those he insults, but at the fact that anyone could be so spectacularly oblivious to their own ego, selfishness, and childishness.

Further, while other SNL stars tend to wink at the audience and turn in lazy performances, Ferrell completely commits to his characters, investing the same energy in his performance as Oscar-caliber actors give to dramatic roles.

Ron Burgundy: Ferrell's Perfect Character

Thus, the character of Ron Burgundy, "legendary anchorman," is perfect for Ferrell. By inhabiting this egomaniacal, idiotic anchorman, he highlights the truth about television news. It's entertainment disguised as information, a show of photogenic faces, glamorous hairstyles, and pleasant voices delivering sound bites of drama, shock value, and sentimentality. "He was like a god," the narrator adoringly intones. "He had a voice that would make a wolverine purr." When Burgundy is groomed for the cameras, he bellows, "Everyone come see how good I look!" And that's funny. He's not aware that he's guilty of more journalistic crimes than Michael Moore. He believes he's an authority, when really he's just photogenic.

Co-written by Ferrell and head SNL writer Adam McKay, Anchorman was inspired by a documentary in which veteran news anchormen reminisce about how upset they became when women made their way into the boys' club newsrooms of the '70s. Burgundy's inappropriate newsroom manner is based on the testimonies of anchors who sipped scotch and smoked right at the news desk. What many viewers will write off as mere political incorrectness was very much a part of the scene and the times.

But Ferrell doesn't dwell on this or try to make the film important. Instead, he uses this rich context as the launching pad for wild departures. And he prefers surprising us with improvisational absurdities — "Knights of Columbus!" "Great Odin's Raven!" "By the beard of Zeus!"" — to pummeling us sucker-punch expletives.

As in that classic SNL sketch, Burgundy relies on the teleprompter to make himself sound intelligent — something that becomes a fatal flaw. But when he's not reading the news, he lacks anything close to eloquence, preferring to express his excitement with things like "That's nice!" and "Neat-o!" His pickup lines and bedroom talk make the whole audience wince in unison.

The flimsy plot — assembled for the convenient sequencing of several SNL-style skits — begins with Burgundy's initial infatuation with a newcomer to the studio, Veronica Corningstone (Christina Applegate). His unlikely seduction of Corningstone follows, and then his subsequent outrage at her ascent to the role of co-anchor in what had been until then a man's game. The two engage in outrageous spats, ending in Burgundy's ruinous defeat and banishment from newscasting, and, finally, his return, in which he must choose between a career-capping professional triumph or the heart of the woman he once loved.

A Better-Than-Average Supporting Cast

Next to his lecherous news team, a surprisingly funny array of sidekicks, Burgundy looks like a saint. Ferrell is restrained enough to let each actor create memorably wacky characters. Their attempts to woo Corningstone and the tantrums they throw when they fail only emphasize their immaturity. Behind their camera-ready facades, they're spoiled brats and playground bullies, prone to crying when they don't get their way.

Brian Fontana (Paul Rudd) is a sex-crazed reporter who tries to impress the ladies with a cologne that "contains pieces of real panther." Champ Kind (David Koechner), the cowboy sports reporter, adores his anchorman a little too much. Brick Talmand (Steve Carell) is a scene-stealing weatherman who's always a step or two behind his brainless cohorts. Carrell walks away having scored almost half of the film's biggest laughs.

Like the summer's other big comedy Dodgeball, Anchorman shows an inspired talent for surprise appearances. Burgundy and the boys face off with Wes Mantooth (Dodgeball's Vince Vaughn) in a scene that could be called Gangs of San Diego, and the scene escalates into an enormous, frenzied brawl that features more than one celebrity cameo.

Trying to keep this crew under control, news producer Ed Harken (Fred Willard, in another winning supporting role) is often sidetracked by telephone calls reporting the disastrous exploits of his offspring. In one of many playful references to '70s naïveté, he confesses that his youngest boy is "on something called acid." When he appeals to his crew to appreciate "diversity," Burgundy guesses that the word is a reference to a Civil War-era ship.

Applegate's Corningstone is the cookie-cutter women's-lib champion, storming her way into the spotlight. "Ladies can do things now," Burgundy is told in what seems to him a profound revelation, "and you're going to have to deal with it." Applegate was a good sport to play "straight man" to Ferrell's insults and disgusting compliments, and even throws herself into some newsroom smackdown. At times, it seems like she's struggling to keep a straight face while Ferrell shouts whatever wild notions come into his head.

(Attention, blooper fans: The end-credits run alongside a variety of goof-ups and losses of composure, and there's an outtake pinned to the very end of the last reel.)

Lowbrow, Cheap, But Bound for Cult Classic Status

Everything leads to a preposterous finale set in a zoo. For those who have surrendered to Ferrell's inanity, it may be the pinnacle of the film; others may give up entirely and head for the door. (One of my colleagues gave up on it and walked out long before that.)

I said it before, and I'll say it again, just to be sure viewers don't waste money on something they don't want: Anchorman does indeed require a heavy caution to viewers. There is a great deal of innuendo-heavy dialogue and frequent genital-oriented punchlines. It's not as objectionable as Old School, and compared to Dodgeball it looks like high art. But anyone expecting the safe, PG-quality humor of Elf may be shell-shocked by the frequent jokes about Burgundy's sexual egomania. Parents, take note: This is not a kids' movie. The film includes much that is inappropriate for young viewers, including a moment when Burgundy unwittingly utters the same "colorful" term recently defended by Vice President Dick Cheney. (Republicans, beware: The Bush administration is the butt of the joke that won the evening's biggest laugh at the Seattle screening I attended.)

Seattle film critic Moira Macdonald mentioned to me that she thinks most of Anchorman's best jokes were done better by Ted Baxter, the anchorman on the '70s television series The Mary Tyler Moore Show. I suspect she's right.

But Anchorman is not as much about news as it is about the chance to unleash Ferrell's irrepressibly zany personality. More than his famous Elf or the comedies in which he's been a scene-stealing supporting player (Starsky and Hutch, Old School, Zoolander, Austin Powers), Anchorman establishes him as a formidable comic force reminiscent of Steve Martin when he was The Jerk or Chevy Chase when he was Fletch.

We can hope that Ferrell will discover he does not need the locker-room humor to make us laugh. It is precisely in his departures from this that he finds his most inspired moments. Until then, though, we have this mix of genuine comic bravado and sophomoric punch-lines.

A Three-Piece Suit and a Doctor Strange T-Shirt

This is crazy. The latest episode of 0ne of my favorite podcasts — The Image Podcast — features a conversation between host Jessica Mesman Griffith, writer Morgan Meis, and... me!

Listen here.

We talked about how our life stories brought us to art and faith by very different paths.

We talked about Agnes Varda films.

We talked about Mike Leigh's movie Another Year.

We talked about the striking differences between my fashion sense and Morgan's.

It was quite a surprising conversation.

And now, you can listen in.

In the Cosmos of the Arts, a Christian Cosmonaut Is Born Again

“NASA Twins Study Confirms Astronaut’s DNA Actually Changed in Space.” That’s the headline that makes you choke, then narrow your eyes, and forget what you were searching for.

Come on. This isn’t The Twilight Zone. A man left earth and came back as somebody else? If you saw this on the cover of a grocery-line tabloid, you’d roll your eyes, you’d push your cart.

But wait—this isn’t the Enquirer or Weekly World News shouting at you. This is Newsweek. You’ve grown up with some measure of trust that Newsweek is actual news. Leaning in, you scroll past the headline and read that seven percent of Astronaut Scott Kelly’s genetic code “did not return to normal after he landed, researchers found.”

Researchers. Found. So, this isn’t speculation?

So begins the epic story of how my struggle to discern Real News from Fake News led to a re-interpretation of my childhood struggles in church.

So begins an exploration of the difference between doubt, certainty, and faith.

So begins my new essay published at Good Letters.

This essay includes

- my thoughts on the film Annihilation;

- a story about my early encounters with rock music;

- a favorite passage from the writing of David Dark;

- a favorite lyric from Joe Henry;

- some thoughts on "church ladies" and perfume;

- "Where the Streets Have No Name";

- and more.

Read the whole thing at Good Letters.

Hustlers (2019)

What would have happened if I'd been assigned to review Hustlers, the new film by director Lorene Scafaria, back when I worked as a film critic for Christianity Today?

Hustlers is, after all, about as "worldly" as movies get. It's a movie about strippers. And it's even more R-rated than that — these strippers are fed up with being exploited and abused, so they strike back by drugging and robbing their wealthy and powerful clients. There's enough nudity, profanity, violence, drug use, and drunkenness on display to traumatize many of the churchgoers I grew up with — to say nothing of the lying, the cheating, the stealing, the vanity, the greed, and so many other kinds of sinful behavior.

It's been several years since I reviewed movies for that magazine and website. But I can guess how it might have played out.

OPTION ONE: Based on my decade of experience writing for Christianity Today's readers, I can be certain that some wouldn't have read the review at all. Some would have gone straight to that oh-so-Christian ministry of writing rage mail, condemning me for "supporting" such a "worldly" movie. They would tell me (and often did) that I was going to hell simply for walking into the cineplex to see an R-rated film. After all, what's the difference between paying money to go to a strip club and paying money to watch a movie about what happens in one?

OPTION TWO: If I were to criticize Hustlers showing us what really goes on in the world of "gentlemen's clubs" — a world of glamour, pornography, drugs, booze, and sexual abuse — some would be pleased to see me confirming what they had suspected, and applaud me for warning moviegoers away from it. I encountered those readers regularly.

OPTION THREE: If I were to praise the film for being truthful about the consequences of bad behavior, some Christian readers would applaud. These would be readers who appreciate that art can be about evil without condoning or promoting evil. They would be readers who point to the Bible itself as a collection of truthful stories about appalling human behavior, readers who know that Context Matters. A movie about the destructive influence of drugs is not the same thing as an invitation to take drugs, right? I encountered and corresponded with many readers like this as well during my years of writing weekly reviews.

I'm not writing for Christianity Today right now — my new career in higher education is too demanding for me to manage a regularly writing gig. But I'm still nervous about reviewing Hustlers. Why? Because I still hear from readers — all kinds of them — and because some of those readers are now my students.

So, why am I reviewing Hustlers? Why did I even bother to see it?

The cast did not appeal to me. Sure, Constance Wu was charming in Crazy Rich Asians. But that's not enough to make me buy movie tickets. Steven Soderbergh's Out of Sight is one of my favorite films, and Jennifer Lopez was fantastic in it — but that movie came out a long, long time ago, and Lopez's projects since then have made me more inclined to avoid her films than rush out to see them.

I went to see Hustlers for several reasons: First, it inspired enthusiasm among many critics I find respectable, and they praised it as a surprisingly well-crafted work of art by women and about women. I'm particularly interested in finding and celebrating great movies made by women considering how difficult it is for a woman to succeed in this industry. Second, many heralded this as the second great performance by Lopez in a movie, and I wanted to believe them. Third, I heard them comparing Scafaria's movie about wealth, power, crime, and consequences with Martin Scorsese's best movies about the same thing. As a great admirer of many Scorsese films — man oh man, when I reviewed The Wolf of Wall Street, the rage mail came pouring in — I found these reports encouraging.

And here's my report:

With extraordinary skill, style, and polish, Scafaria has crafted a flashy crowdpleaser. Hustlers is a fireworks show of light, color, music, humor, drama, and energy. It adapts an article by journalist Jessica Pressler published in New York magazine into a movie that, with a clever and propulsive pop soundtrack that uses era-defining hits (like Fiona Apple's "Criminal) to time-stamp specific chapters, feels a lot like a musical.

The story it tells is as impressive for the audacity of its protagonists and it is almost irresistibly lurid. We follow a community of lap-dancing strippers — the aspiring novice named Destiny (Constance Wu) and the flamboyant fortune-hunting pro called Ramona, among others — through training exercises (in dancing and in tricking money out of rich clients), testimony times (about the ways they've been exploited), moral support sessions, financial hardships, and horrible nights in which abusers got the upper hand. And then, when the recession turns their world upside down and forces them into a far more vulnerable and even life-threatening position, they make a new plan: They will bait, drug, and steal from their wealthiest clients.

The first act of this movie is crafted to make us fall in love with these women. We're meant to stand in awe of their abilities, to admire their camaraderie, and to cheer for their dances, even as we're also meant to revile the men who are throwing money at them and abusing them behind closed doors. Okay — so they didn't grow up dreaming of this business. But good for them, that they are learning to turn their misfortunes into opportunities! How clever of them to exploit weaknesses of their wealthy clients, and to turn the tables, gain the advantage, and make a fortune, so they can not only pay their bills but work their way up to living like millionaires.

The backbone of the narrative is the relationship between Destiny and Ramona — Destiny, the admiring apprentice who needs money to raise her daughter, and Ramona, the consummate professional who launches a criminal enterprise against the crooks who have sought to reduce her to sex slavery. Will these two women, who have such powerful chemistry and obvious affection for one another, turn against one another when their crime spree inevitably spins out of control?

I can imagine a big-screen version of this story that chooses the path of truthfulness — one that impresses upon us the desperation of women in this business, the cost of the choices they make as they climb from poverty toward success, the ugliness of the men who pay for this kind of "entertainment," and the wages of the sins that the dancers commit in order to fight back against the sins of their abusers. In fact, last year gave us a movie that did this very well: Support the Girls.

But this is not that movie.

The performances are decent, but I can't say I was convinced by any of them. These looked like glamorous movie stars playing glamorous roles, and scene by scene the movie seemed too carefully calibrated for entertainment for this to ever feel like a credible depiction of What Really Happened.

The strip-club dancing sequences — the main attraction in the film's advertising — deliver impressive exhibitions of athleticism, sure. (NPR's Pop Culture Happy Hour team enthused about a behind-the-scenes video about Lopez's travails in learning to pole dance.) And yet, while I agree with critics who have observed that Scafaria's cameras are not driven by "the male gaze," these sequences are still aiming to astonish us with the sex appeal of the performers. For all of Hustlers' emphasis on women striking back at the men who abuse them, the movie is still more likely to attract men to strip clubs than to repel them.

There's a duplicitous nature to Lopez's performance in particular. This performance is, after all, just an extension of the persona she's developed as a pop star. Embracing the Madonna template, she's made a career of cultivating herself as a sex object in her music, her videos, her fashion, her public appearances, and her advertising contracts. It's not any kind of leap to see her move from that to playing a blockbuster lap-dancer. So, Oscar buzz? I don't get it. Is she carefully cultivating a complicated character onscreen, or does she just happen to fit this character description?

As for those comparisons to Adam McKay's The Big Short and Scorsese's The Wolf of Wall Street — well, okay... this is a movie about fortunes made, financial calamity, the Recession, and the players who caused it and plotted nefarious ways to survive it. And Scafaria is obviously employing a lot of familiar filmmaking tactics to represent extravagant wealth, juggernaut talents, and disastrous falls.

But those were films aimed at satirizing the shenanigans in question. They were movies that appealed to a voice of conscience: they hoped we would watch these circuses of con men and gullible targets, and then back away in dismay, wanting nothing to do with such a system, eager to wash our hands of any way in which we've unwittingly contributed to the evils on display. In their satire, there was an element of the tragic, of deep loss, for those who might actually believe in America's noble ideals.

Here, the depiction of heartless, headless men is revolting — and rightfully so! But Hustlers wants us to cheer for women who, exploited and harmed, turn not toward a higher road, but instead go low when rich guys go low, seeking to beat them at their own game. And their motivation isn't righteousness or justice — it's money. We're meant to feel giddy as they pop the champagne on their successful crime sprees. This is a movie built on electrifying us with the cheap thrill of revenge, and dazzling us with materialistic rewards. The imaginations enlivening this spectacle aren't insightful enough to question the part that these women are playing in reinforcing the very system that exploits them. In fact, Hustlers seems as excited about Ramona's qualifications as bait for lustful wolves as it is about shaming the wolves for taking the bait she so enthusiastically dangles in front of them. Out of one side of Hustlers' mouth, we hear "Men who frequent strip clubs are monsters and creeps," and out of the other side, "These dancers are goddesses, and isn't it a shame that they got caught when they deserved to make a fortune?"

The film's final word is entirely cynical. Ramona gets to drop this wisdom on us: "This city, this whole country, is a strip club. You've got people tossing the money, and people doing the dance." (Yeah, this is one of those movies in which the last line is "the moral of the story," in case we missed it, so we can feel smug on our way out.) Hustlers never questions whether there is any other response to corruption but to join in and game the system for the sake of survival.

I don't approach films about this kind of subject lightly; I see the destructive effects of the objectification and hyper-sexualization of women every day. I see it in the social contracts presented to my female undergraduate students: they can either surrender (and suffer) or resist (and suffer). I hear it in the way men on sports radio talk about women — particularly their wives or girlfriends. I cringe at the evidence of it in advertising.

So I had hoped that, as some of the buzz promised, this movie might feel countercultural, conscientious, even revolutionary.

But, contrary to the hype, no — this is a million miles from the vision and integrity of a film like Support the Girls. This movie knows full well just how much audiences will throw money at big names who do this dance.

P.S.

One last note about those evangelical Christian readers who would have responded to this review by writing rage mail:

As I think back about those who used to condemn me as "an agent of the devil" or as "selling out to The World" for paying attention to a movie about "the underworld," I cannot help but observe how much of that condemnation came from the very community that then turned around, listened to, voted for, and now continue to support our current President. This is a man who loved strip-club culture — famously and publicly. A man who paid money to have sex with porn stars, and spent even more money trying to cover up that fact. A man who continues to speak derisively about women. Who has bragged about committing sexual assault. Movies about men like him, they say, are obscene. But the man himself — unrepentant, boastful, hateful? They exalt him.

It makes me wonder if they have ever read the Bible they seem so eager to throw at me.

Cinemarginalia: September 21

Streams that feed my river of movies...

For some people, subscribing to Netflix, Hulu, Amazon Prime, NBC Universal, The Criterion Channel, and all of the rest of the rapidly multiplying streaming services is as easy as finding some nickels and dimes under their couch cushions. But for most people I know — the people most likely to actually stay home and use streaming services instead of going out on the town for the evening — it's a major investment.

I certainly can't afford to subscribe to more than two or three, and even that is a strain on my budget. (I'm an English professor and a film critic, so, yeah — I shop at Costco, not Whole Foods.) But I still have more movie-viewing options than I can keep up with. I subscribe to Netflix, currently, but my resolve to stick with them is failing. I subscribe to Amazon Prime, but that's for ordering items I can't afford elsewhere; the streaming video is just a bonus. What sources actually offer movies that are consistently worth my time?

1. The public library. I have memberships in three separate public library systems: The Seattle Public Library, King County Library System, and So-Isle Libraries. I monitor their film collections, and I almost always have fifteen or twenty titles on request.

2. AMC A-List: For $20 a month, I can see up to three movies a week at the biggest cineplex chain in the Seattle area. And I do — I see one, two, and sometimes three a week. Considering typical ticket prices, I've covered the cost of my subscription before the end-credits roll on the second movie of the month. (Also, I never buy concessions.)

3. Kanopy. This streaming service, which is currently free through my local library and through my University library, is an awe-inspiring collection that is updated all the time. Unfortunately, their prices have been climbing, and public libraries have started dropping the service. If you're lucky enough to access it for free, do it!

4. Criterion Channel. The Criterion Collection is a national treasure, and their streaming service gives you access to many of the finest films ever made. Plus, it's loaded with extra resources on those films. And I'm a big fan of their special interview series. I think it's worth the annual hundred-dollar subscription. But if you aren't into art films and film history, you probably won't use it much.

5. Buying used blu-rays and DVDs (eBay, Half Price Books, Amazon etc). You realize, don't you, that it's now cheaper to own a great movie — and often a film package that includes a blu-ray, a DVD, and a digital copy — than it is to go see one in a theater? Hmmm. Pay about $15 to see a movie once, or pay about $12.99 (or maybe $3.99) to own it in a variety of formats and watch it whenever you want. Tough call, huh?

This Week's Big-Screen Priorities

Based on what I've heard from reliable sources and read by reliable writers, here's how I'm approaching the new week in movies.

High Priority: Ad Astra

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nxi6rtBtBM0

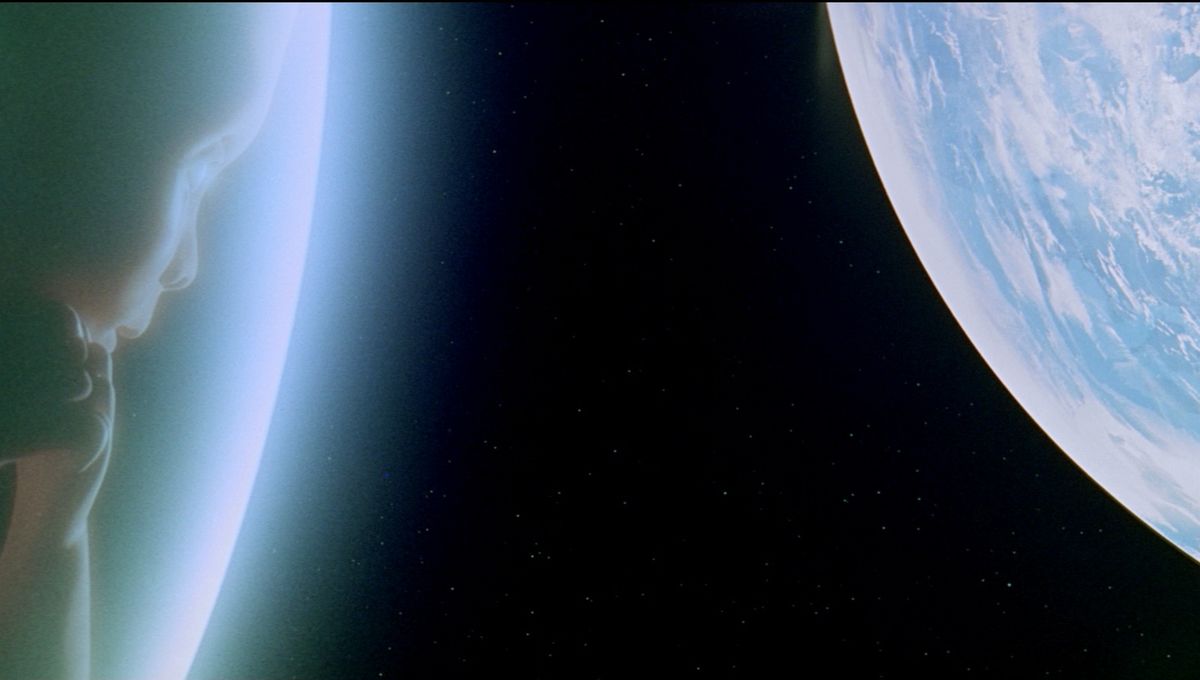

Director of Two Lovers and The Immigrant (both of which starred Joaquin Phoenix) as well as The Lost City of Z, James Gray is quickly becoming one of my favorite young auteurs. This film features an original score by Max Richter (with contributions by Nils Frahm), cinemtaography by Hoyte van Hoytema and Caleb Deschanel, and it stars Brad Pitt in what may be his best lead performance.

Does it sound like I've already seen it? I have. And while the screenplay has some problems (it fails the "Show, Don't Tell" test in its final moments, and some of our hero's adventures seem too contrived and too coincidental), I didn't mind so much. I was enthralled by the intoxicating fusion of imagery and music, and by the narrative's exciting correlations with (and revisions of) both Apocalypse Now and 2001: A Space Odyssey.

I'm Curious: Where's My Roy Cohn?; Midnight Traveler

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lTrHL7Vo_SQ

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BTT-duEoRdc

Not My Kind of Thing: Downton Abbey

I watched the first season of Downton Abbey, and about half of Season Two. But it quickly became clear that while the show was committed to the historical accuracy in details of fashion and manners, it was a far, far cry from the depth of the storytelling in Robert Altman's Gosford Park, the film that seemed like its most significant inspiration.

Eavesdropping on fans of the show in my office, I quickly concluded that I'd made the right choice to bail. The things that got them talking sounded less like art and more like the carefully calibrated crowd-pleasing strategies of soap operas.

But here's my main objection: Where Gosford Park was a troubling portrait of how wealth distorts the worldviews of the wealthy, and how privilege and power easily turn to perversion and cruelty, Downton Abbey always feels like its driven by a longing for monarchy, for hierarchy, for privilege, for extravagance, without much more than some feeble gestures toward the consequences of such systems. As Americans begin awakening, little by little, to how they are being exploited and played by the super-rich, this franchise feels like a dangerous kind of denial.

Perhaps I'm wrong. Perhaps the series has become a weave of narratives that cultivate empathy and awaken conscience. If so, let me know.

Just... No: Rambo: Last Blood

Even when I was in high school (in the late '80s), the Rambo series seemed like a dehumanizing influence at the movies.

I like the way film critic Bilge Ebiri put it on Twitter:

The Outsiders

I have finally seen this adaption of S.E. Hinton's beloved YA novel, directed by the man who made The Godfather and Apocalypse Now. (I picked up a DVD for a few pennies.) It was released during a time when I was still restricted from seeing almost everything, and I'm sure that the film's focus on gang violence put it far, far out of my reach.

Here are a few thoughts that crossed my mind as I watched:

- Imagine a world in which Tom Cruise would, from here on out, only take roles like this one — popping in and out so rarely and briefly that we barely have time to say, as I did (out loud, alone), "What?! Was that him?" That would be amazing. And that's what it's like watching him here.

- Man, it's so hard to believe that Coppola directed this. A whole decade after The Godfather, Part II. It seems so strangely shoddy and unsophisticated. Was he depressed? Cynical? Did somebody else ghost-direct?

- I'm clearly seeing a lot of Hollywood superstars younger here than I've ever seen them. Okay, that's kinda cool. But whoa — was that Tom Waits younger than I've ever seen him in a feature film? Awesome.

- Diane Lane was teen Phoebe Cates before teen Phoebe Cates became teen Phoebe Cates.

- This is a pretty bold Coming Out movie for 1983. Stay gold, Pony Boy.

- There's a lot of Outsiders DNA in Van Sant's My Own Private Idaho, isn't there?

- MVP: Ralph Macchio. Runner-up: Sofia Coppola. Kind of amazing, but I actually recognized her.

Cinemarginalia: September 14

In the 2017 movie Columbus, Gabriel is a young librarian (played by Rory Culkin) who develops a preoccupation with reading marginalia in the books he's supposed to be re-shelving.

And before long, he's inspired by some particularly intriguing scribblings that address what is largely believed to be a "crisis of attention" in our culture. Gabriel, paraphrasing the scribbler, argues that what is perceived as a decline in attention spans might not be about attention at all — that young people might not be losing their ability to pay attention, but rather that they might just be demonstrating different interests. What if, he suggests, we're experiencing a "crisis of interest"?

This is only a subplot in the film, and might be easily dismissed as incidental. But I think it's crucial to understanding the whole film.

The main character, Casey (Haley Lu Richardson), is a young woman who is training to become a tour guide for her hometown of Columbus, Indiana, a hot spot for fans of modernist American architecture. But as she practices her informational speeches about important buildings, we realize these speeches don't scratch the surface of why these buildings are meaningful to her. We get what is really important about these buildings by listening in on her personal conversations, where she talks about the beauty and mystery that attracts her to such designs, and why they seem to unlock reservoirs of emotion within her. We learn what actually interests her... and why.

I'm trying something new here at LookingCloser.org: Cinemarginalia.

If all goes according to plan, it will be like a newsletter in which I share something more than my usual reviews and essays. It'll be a sort of journal full of bits and pieces and notes from my week in moviegoing... along with scattered, miscellaneous bits about listening and reading as well. And it just might be that, in sharing the "marginalia" of my ongoing conversations and social media adventures, I might end up sharing things you find useful or interesting.

Some of what I post here will be drawn from things I've shared earlier with the Looking Closer Specialists, the friends who support this site with donations, in the private Facebook group I've set aside for them.

This week? I'll ramble on about Blue Jay, Gemini, Luce, Moulin Rouge, The Peanut Butter Falcon, and more.

Blue Jay

I watched this film with a good friend at the SPU Faculty Writing Retreat, after a long day of writing. We had just spend the day investing our time and attention in several long sessions of work on new writing projects. And, well, I'm tempted to say we should have just kept writing, but, as it turns out, our suspension of disbelief was quickly spoiled by this film and we ended up commenting on it, MST3K-style.

Movies written by actors, in my moviegoing experience, tend to be big on emotions and low on sense. You can always spot the moments that drove the screenwriting: actors contriving scenes that will give other actors (or, worse, themselves) big moments to astound us with nuance, complexity, and intensity.

Moreover, movies written by the Duplass brothers are increasingly spoiling my suspension of disbelief for that very reason. They are designed to present incredibly complex and emotional relationships. Hashtag: Layers. Watching actors emote is one thing; being drawn into a movie to experience those emotions and empathize with those emotions is something else altogether. I don't feel for characters in Duplass brothers films: instead, I just sit back and watch deeply messed-up characters in preposterous scenarios march flamboyantly towards the inevitable disasters they're designing for themselves.

Last year's Outside In, directed by Lynne Shelton and co-written by her and Jay Duplass, lost me right away. It's about a 30-something dude with the emotional maturity of a 16-year-old who, released from prison, runs, like an injured child to his mother, back into the arms of the former high school teacher and counselor who helped him through his years of incarceration. She (played by Edie Falco) is older, supposedly wiser, and married with a teenage daughter. For the first half of the movie, I thought we were seeing an intimate portrait of a lost soul making a terrible mistake, mixing up his desire for a mother and his still-very-adolescent desire for a lover. For the second half, I watched in dread as the movie strove to make me want to see them get together. It made very little sense, I didn't believe in the characters, their choices seemed consistently alarming, and the whole thing made me frustrated and a little sick. And yet the film insisted on being a lament over the world that would keep these two destined lovebirds apart. It was kind of astonishing.

Blue Jay, by comparison, makes Outside In seem like the wonderful love story it thinks it is.

Sarah Paulson is an extraordinary actress, and Mark Duplass is... well, Mark Duplass. Together, they work their way through prolonged and rambling conversations that feel like Actors' Workshop Improv, zigzagging from one scene of Complicated and Layered Emotions to another. The emotional dynamics are complex, that's for sure, and it's almost entirely to Paulson's credit that some of these scenes are watchable.

But oh, what a mess of a movie.

After the initial awkwardness of opening scene, when two former lovers meet for the first time in many years and awkwardly fumble through small talk and into the predictable "Do we still have the Feelings?" situations, Amanda — after revealing that she is very much married with kids — follows Jim home, seemingly determined to stir up as much angst and old-flame chemistry as possible.

Sure enough, they plunge into nostalgic paraphernalia (photos, old letters, favorite early '90s music, cassette tapes of the two of them goofing around and rapping badly). and then they settle in for a long night of — and this is where things go from awkward and meandering into the wildly implausible — improv play-acting. Apparently, as very young lovers, Jim and Amanda used to engage in impressively sustained fantasies of domestic drama and flirtation as an imaginary husband and wife with children. And they recorded them on cassettes. I'll give this movie credit for staging scenarios I've certainly never seen in movies before, but the novelty of watching characters sit and listen to long stretches of tape-recorded silliness tested my patience. Watching their middle-aged selves pick up where those crazy kids left off and dive into new charades... that brought down a sledgehammer on what remained of my hopes for some plausibility.

Some have found these scenes to be romantic. I worry about those viewers. Amanda is kindling a very destructive fire by flirting with Jim, who is clearly suffering from a deep depression. (The revelation, later, that she is taking heavy medication for depression of her own doesn't excuse this behavior.) And for the sake of, what? Does she just enjoy his attention? He clearly adores her, and she clearly intends to remain faithful to her husband and family — so why offer a drug to a man who has clearly been wrecked by that drug and say "Just pretend to take this drug"?

You can tell that big revelations are coming, and when they arrive... well, there they are: not particularly surprising, but also not at all convincing. People who had lived through Jim and Amanda's personal history could never have shared the evening that these two just acted out. It was hard enough to believe as I watched it, and it makes zero sense in retrospect, in view of the film's climactic confrontation. I would have to believe that both of them live a profound state of PTSD, and that we're watching a sort of mutual madness. And when those emotional-breakdown scenes finally come, they ask things of Duplass that he cannot deliver.

Strangely, I felt very much the same way about this film as I felt about Paddleton. Both are movies about high-stakes, high-drama situations, played out by a great actor and Mark Duplass, in a sequence of complicated and emotional scenes that culminate in one or both of them having spectacular meltdowns. I'm supposed to be moved, but I'm just frustrated and exhausted.

I've seen Blue Jay compared favorably with the Linklater Before movies, and... no. Just... no. Not even close.

Gemini

For about 30 minutes, the graceful and nuanced performances of Kirke and Kravitz — bathed in a kinder, gentler Michael Mann gloss — make this something really special and exciting. Chemistry like that deserves a movie that is good all the way through.

But then, a gun appears. It isn't fired right away, but it might as well have been, because the film's absorbing human drama shatters and it becomes a clumsy and unsatisfying mystery that wants to be some kind of profound Mulholland Drive commentary on celebrity or something. Kirke spends the rest of the movie dashing around in the most preposterous wig like one of those spunky TV detectives who, discovering she's a suspect, will set out like an idiot to solve a crime on her own while the cops fumble about. And it wasn't long before I realized that I couldn't care less what kind of surprise was waiting for me. (And when it comes, it's shrug-worthy.)

No movie should have John Cho in it and give him so little to do. The fact that the film wastes not one but two of the cast members from the Columbus ensemble (Michelle Forbes is in this, too) within months of that film's release only adds to the sense that this could have been really spectacular.

Still, the spell cast in that first act, and some of the exquisite cinematography — particularly the "chase" scene involving a motorcycle and a police car — made this worthwhile. I might even watch it again someday just for that.

P.S. Surprising to discover that one of the paparazzi stalking Kravitz's Heather is played by Chad Hartigan, director of This is Martin Bonner and Morris from America.

Luce

Wow, this thing is vanishing from theaters almost before I noticed it was there. I saw it in an almost-empty theater today — well, it was empty if you disregard the three people in front of me who were scrolling through Instagram (THIS IS HAPPENING FAR TOO OFTEN) — and it's one of the most provocative, unpredictable, and talk-aboutable films I've seen all year. A couple of turns in the last 30 minutes strained my suspension of disbelief, but it's braver and more complicated than the recent hit that wrestles with some of the same questions: Get Out

Moviegoers are missing out.

The cast are all strong. I wonder what's missing here that might have made it catch on. If Nicole Kidman and Michael Shannon had been cast instead of Tim Roth and Naomi Watts, would that have worked? Are we experiencing Octavia Spencer fatigue?

Whatever the case, I'm so glad I saw it.

Museum Hours

First time I've seen this on blu-ray, and — Holy Halls of the Kunsthistorisches Museum, Batman! — this is unspeakably gorgeous. Bumping it up to five stars.

2013 is looking better and better in retrospect, as I'm still uncertain how to list my top 6 of 2013: Hartigan's This Is Martin Bonner, Chung's Lucky Life, Linklater's Before Midnight, Carruth's Upstream Color and Castaing-Taylor's and Paraveland's Leviathan are all so, so good every single time I revisit them. (And then there's Frances Ha, The Past, The Wolf of Wall Street... what a year!)

Anyway, this is aging very, very well.

I've noted before how Museum Hours is the the non-identical twin of Kogonada's Columbus — Columbus is the more complicated and absorbing character-focused narrative, and this is the deeper meditation on the nature of art. I can't think of one without thinking of the other. I would love to interview Cohen and Kogonada together — that would be fascinating, especially since Cohen is listed in the credits for Columbus. Both Bobby Somner and Mary Margaret O'Hara sculpt singular human beings before our eyes with the subtlest of gestures, the quietest tangential conversations, and long pauses that allow Vienna to come alive the way Berlin does in Wings of Desire. There's a blink-and-you'll-miss-it moment when Somner contemplates how a path through an urban scene in a short film emerges as, perhaps, the primary subject of that film... and I take that as a prompt to entertain the same idea about this film, which is so constantly interested in paths crisscrossing through the Bruegel-esque pageantry of Vienna.

It is constantly enlivened by a sense that the filmmaker is trying to keep up with the inspirations occurring to him through his camera, as if he's receiving a signal instead of strategizing a show. This stands next to Cameraperson and Hale County This Morning, This Evening as a strong representation of what seems to me to be cinema's purest and highest art: it juxtaposes images in motion and discovers what they have to say, rather than merely illustrating a text or heavy-handedly forcing a particular reading.

As the great Sam Shakusky would say, "That sounds like poetry."

Moulin Rouge!

This weekend, I revisited Moulin Rouge! for the first time in more than a decade, curious to know if it could still kindle the kind of enthusiasm it once did. Flamboyant colors firework off the screen just as I remembered.

Nicole Kidman — what a career. This seemed like the biggest superstar moment of her performances so far, one calibrated to make her an icon. And it worked. She has become a role model for any great actress, aging gracefully from one kind of role to another, and still giving luminous and challenging performances I can't imagine her improving upon. She got my attention in Flirting in 1991, and she's made me believe in every single character she's played since then. Has she ever given a disappointing performance? The only thing I find unsettling in this film is that she and Ewan McGregor look like fresh-faced college kids, younger than they seemed to me back then. (I guess that means I'm getting old.) Kidman was 33, but looks 21 here, and strikes just the right balance of drama and comedy. McGregor, four years younger than Kidman, keeps up admirably, but I can imagine a number of young actors who might have done just as well.

But this time around, for me, it's Jim Broadbent who steals the show. When we talk about the greatest screen actors of all time, keep in mind that Broadbent has given 100% to everything: high art, popular franchises, and kids' television. He won an Oscar for Iris; ruled in Mike Leigh's Another Year, Topsy-Turvy and Vera Drake; and then, Paddington and Paddington 2; Game of Thrones; Brooklyn; Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull; some Harry Potter movies; The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe; Bridget Jones movies; Gangs of New York; Cloud Atlas; Hot Fuzz; Bullets Over Broadway; Enchanted April; Brazil; Blackadder; Time Bandits; and even Teletubbies. I first saw him in The Crying Game, where he made a strong impression in only a few moments. And he was so, so good in Longford, which I wish more people would see.

And here, in Moulin Rouge!, he dances like a mad fool and sings "Like a Virgin"!

Top that... anybody.

So, yeah — I still love Moulin Rouge! I saw it at least three times in the theater when it opened. I wasn't expecting subtlety or complexity from Luhrmann. Rather, based on the crowdpleasing magic of Strictly Ballroom, I was hoping for a similar mix of absurd grandiosity, hilarity, and passion, and he surpassed my expectations. It's a pop opera that acknowledges and celebrates the all-caps obviousness of pop music and how it unites audiences in a liturgy of dreaming and longing. It looks fantastic, it sounds even better, and pop-music classics from Elton John to Madonna to Bowie are sewn together into medleys that honor the artists that first sang them. I'm glad it's out there, and I wish we saw more big swings like this on the big screen.

War of the Worlds

Not sure what compelled me to revisit this a midnight movie 14 years later, as it underwhelmed me the first time. Have Marvel movies made large-scale action so routine and unsurprising that movies I used to find mediocre suddenly seem much more impressive? I found this much more absorbing on DVD on a crappy hotel-room TV than I remember it being in the theater!

Tom Cruise remains Problem #1 for me here: He's basically your Costco Movie Star here: Push button for Jerk, Push button for violent rage, Push button for crisis of conscience about being a bad dad, Push button for I've Got a Bad Feeling About This, Push button for Run Like Hell. I could go through a long list of movie stars who might have done wonders with this. Imagine 2005 Mark Ruffalo in the role, for instance.

Problem #2 is that the aliens, when we finally see them out and about, aren't particularly interesting.

Their vehicles, on the other hand, a brilliant fusion of the original Tripod concept, The Matrix's Sentinels, and the T-Rex: simply awe-inspiring terror machines.

Problem #3: Okay, Dakota Fanning can scream. But less is more, Spielberg. Come on. After a while, the screaming becomes a distraction, not an enhancement of the terror.

Having said that, Fanning is so, so good in the quieter moments. Her face is so much more eloquent with fear and trauma than other Scared Girls in Spielberg Movies.

But the greatest strength of this movie is Spielberg's gift for staging the movement of crowds under the influence of fear, and that particular tipping point when order turns to chaos. Normally, action on a grand scale like this is the forgettable stuff and the intimate stuff is more arresting. But here, the close-quarters suspense scenes are too reminiscent of Jurassic Park Velociraptor Stalking Scenes and Minority Report probe scenes, and Tim Robbins' Panic Man is played too broadly to be very believable. No, it's the Initial Emergence of Tripods stuff that sticks with me, and the virtuosic effects and hysteria of the ferryboat scene — those sequences command attention like few things he has ever staged.

When the film was released, I found the final moments anticlimactic, and the Morgan Freeman Intro and Outro just infuriatingly bad. This time, the Freeman stuff plays like a nostalgic gesture to the original radio broadcast, and the Family Is Everything finale is... oh, I don't know, fine, I guess. Maybe it plays better in this living hell of Trump's family-separation cruelty. Maybe I'm more tolerant of obvious themes spelled in in large capital letters.

Elbow's "Empires"

Thanks to Specialist Ken Priebe for sharing the new video from Elbow!

https://youtu.be/EJa5FvCaBJc

Just Mercy trailer

Thanks to Specialist Jared Malament for sharing the trailer to Just Mercy, the much-anticipated feature film adaptation of Bryan Stevenson's inspiring book. I'm a little worried about this: the trailer makes the film look heavy-handed and overly earnest. It's always tricky to turn inspirational non-fiction into artful cinema, and I'd recommend that you check out the book rather than settling for the film. We'll see — maybe the film is stronger than the trailer indicates. (Early word out of Toronto, where the film just premiered, suggests that my intuition is well-founded.)

https://youtu.be/fbWiCPx99rs

The Peanut Butter Falcon

What a strange, uneven film.

As a challenge to audience expectations by building a narrative around an unconventional protagonist (a la The Station Agent), it works, for the most part. Zak, a young man born with Down Syndrome, is a convincing and compelling character. He is treated with respect and some degree of realism. He's complicated and funny, and he inspires empathy.

However, I couldn't quite shake the kind of feeling I had when I saw the movie Radio, a movie about a mentally challenged protagonist in which the film asks us to shrug off, to some extent, the value of specialized treatment and the goodness of professionals who provide meaningful care, opting instead for a sort of wishful-thinkingness: If he just finds a good-hearted man and woman to serve as surrogate parents, why... he'll have all he needs! This may not be disrespectful for those with Down Syndrome, but it seems quite disrespectful to those who dedicate their lives to providing specialized care. It tells us what we want to hear, rather than acknowledging the complexity of the situation truthfully. ("Sure, Eleanor's a lovely woman, but she's so focused on monitoring Zak, she hasn't realized that what he really needs is... Love and a Good Friend!" Come on.)

As a fairy tale — or, better, as a work of magical realism — it achieves some of the whimsy and personality of films like The Kings of Summer and Hunt for the Wilderpeople. But those flourishes of fantasy are so rare here that they occasionally seem jarring, particularly in the climactic moments, when Zak gets a chance to fulfill his dream. (Frankly, the ways in which everything Zak needs is conveniently provided along the course of the narrative disrupted much of a sense of suspense or conflict, so I didn't feel the celebratory rush I think I'm meant to feel at the end.)

As a "gritty" Southern tale, it didn't work as well for me as Mud did, and far less than Shotgun Stories did. (I've read a lot of comparisons to Mud and Undertow.) That's partly because the characters all seem rather simple, almost like characters in a children's story that a writer has tried to make "authentic" by adding all kinds of superficial roughness. Shia LaBeouf's Tyler, for example, peppers his speech with expletives and profanity, and even in casual moments — like making an incidental comment at the wheel of a car — he's likely to pick his nose or something. These often felt like a strain to avoid sentimentality, but they were as distracting as often as they were, well, human. And the opening scenes work hard to show Tyler as an irresponsible and reckless man who needs a significant redemption arc, but that reformation seems to occur too quickly, too easily.

The cast, though, are uniformly charming. It's a delight to see Bruce Dern commit to this even more than he seemed to commit to his recent Tarantino appearances. Dakota Johnson is sweet, even if her character feel a little too much like The Potential Love Interest. Shia LaBeouf is remarkably charismatic and likable here, making me think of what a younger Christian Bale might have done with this role. Thomas Haden Church does a lot with a little here, playing a character who is a little too convenient, a little too hard to believe.

Overall, it's a sweet, strange little film that feels just a couple of drafts away from being something really special.

Turn and Face the Strange: a challenge to artists and churches

In April, I spoke at Brehm Cascadia's Sacrament & Story conference.

As usual, I was asked to speak for about half an hour, so I prepared notes for a full hour, and then just moved really, really fast. I packed in a lot of David Bowie, David Dark, Madeleine L'Engle, Over the Rhine, Sam Phillips, Moonrise Kingdom, The Secret of Kells, Babette's Feast, a scene from The Fits, and more. Oh, and even though my voice was in bad shape from a week of heavy lectures at school, I sang a little. Very, very badly.

Anyway, if you're interested, this is a presentation about the courage that artists must have in order to behold, and then bear witness to, new visions of beauty and truth.

It's also about the need for churches to trust, support, and attend to their artists.

Enjoy. And I'd love to hear from you if it inspires any thoughts or questions.

https://youtu.be/OOTg8ReiWMo

First Impressions of The Dark Crystal: Age of Resistance

What's the longest you've ever had to wait for a story that you love to continue?

I remember the long three-year wait between the original Star Wars movies, so I had no patience for those who complained about the "long wait" between Harry Potter movies or Lord of the Rings installments. I yearned for new chapters of Twin Peaks, and had to wait decades — but then, that just seemed like wishful thinking: there was no promise that they'd ever make more. 2017's it Twin Peaks: The Return came as a mind-boggling surprise.

By contrast, I've had to wait even longer for a new film about The Dark Crystal, the Jim Henson fantasy film that rocked my world when I was 12. I've heard plenty of people talk about the movie the way others talk about childhood trauma. I suppose it has its creepy moments, sure — but The Dark Crystal's handcrafted creativity of that film inspired me to write fantasy stories of my own and even turn one of them into a puppet show for friends in my neighborhood. In this case, there have been indications of plans for new chapters—talk that's lasted more than 15 years. And I've been hoping and waiting and wondering if they were ever going to get something made.

Well, here it is: Netflix's new series The Dark Crystal: Age of Resistance landed last week.

I don't review television series, typically. I'm too preoccupied with film reviews to devote much time to TV. So, rather than review Age of Resistance, I think I'll share a conversation I'm having with the person whose opinion about the series matters most to me: Ken Priebe, author of two books about the art of stop-motion animation, author of the children's book Gnomes of the Cheese Forest (and the upcoming Let There Be Owls Everywhere), a resident animation guru at VanArts (where he serves as a communications manager), and... well, I could go on.

I can't think of anyone I know whose passions for animation, fantasy, and play align with my own as much as Ken. When I met this guy and started reading his thoughts about the Muppets, I knew I'd found a kindred spirit.

So, after I watched the first episode of the show, I emailed him. In short, I was nervous. I loved the first episode so much, I was worried that I was setting myself up for a major heartbreak. And I'm glad I checked.

Here's our conversation...

Overstreet:

I've been tied up in knots about the idea of a sequel for a long, long time. Back in 2005, I blogged about reports that a sequel was in the works, and I expressed my concerns about the likelihood that any return to the world of Gelflings and Skeksis would end up overwhelmed by digital animation, minimizing the hand-crafted animation that made the original such a mind-boggling work of creativity.

I've just watched the opening episode of the new series, and I'll probably go back for more tonight. At the same time, I want to go slowly and make this last. That probably tells you that I am, at the very least, willing to watch more. It doesn't look like the disappointment that I feared.

But you've seen more than me. Can you, without major spoilers, share some of your first impressions?

Priebe:

Like a gluttonous Skeksis, I ended up binge-watching the entire series in one day, but I know I shall return for a more leisurely visit and watch it again.

The idea of returning to the world of The Dark Crystal has been on the tables of the Jim Henson Company for a long time. Netflix also has a nearly-90-minute documentary on the making of this new production, which is fascinating to watch and provides a good overview of how the writers and producers arrived to it, including some previously-unreleased visual material.

Overstreet:

Whoa, cool! I hadn't noticed that yet. Any behind-the-scenes show on a Henson project is worth my attention.

Priebe:

As you will see, they did some unsuccessful attempts at merging CGI Gelflings with actual puppet Skeksis, which luckily convinced them to go all-puppet — and only using CGI for specific needs here and there to enhance the story.

And it works. O, does it work.

Overstreet:

I agree! I was nervous during the prologue, which felt a bit clunky and obligatory — but let's face it, the narration in the original movie was just about as bad as the puppetry was extraordinary. Once we plunged in and started following characters, though, I was completely immersed.

Priebe:

I'll admit the prologue was clunky, yes. Later when I realized it was Sigourney Weaver, I gave it another chance, but still an odd choice, I think. Forgivable though, as so much more in the series makes up for it, and it helps set the stage for those who are unfamiliar with the original movie. Much could be said about comparing this to the original, which is folly in some ways, for the original was literally made in "another world, another time" when it comes to technology and the limitations the filmmakers were faced with. The original laid the foundation, and since then we've had the collective consciousness of a legion of fans, plus novels, comics, and other lore to develop the world over 30+ years, while the technology has improved at the same time.

If anything, I was most nervous going in to Age of Resistance about the director, Louis Letterier, whose work I was unfamiliar with.

Overstreet:

I saw his The Incredible Hulk, and, except for the fact that Ed Norton was in it, I don't remember anything. And that's saying something, considering how much of the Ang Lee Hulk movie, which came out several years earlier, that I can remember vividly.

Priebe:

I tried watching scenes from Now You See Me and his Clash of the Titans remake, and couldn't continue because the camera literally would not stop moving and it made me sick to my stomach. But I've been pleased to find that his directorial style has not spoiled his stamp on Dark Crystal, and his sweeping camera moves actually do allow us to explore the environments and hand-made detail of the sets, characters, and landscapes. It's less restrained than Henson, but restrained enough to still bring us fully into this world. Even the action scenes are riveting and easy enough to follow without headaches. I think hiring a live-action director like him was ultimately a good choice, for as the documentary shows, he treated the puppets like real actors.

Overstreet:

It would be interesting to see a director with a particular, personal style take on material like this. But I imagine it's hard to find a director who has the patience and expertise to work effectively with puppeteers and capture their intricately detailed work in a way that makes it feel natural and lifelike.

And in Episode One, I'm already surprised at how willing he is to dramatize the violent prequel narrative that was only implied in the original. More disturbing aspects of the story — like the Skeksis pursuit of Essence, which they drain from victims like vampires sucking blood — are portrayed in a way that makes me cringe about the thought of young children watching this. I was 12 when I saw The Dark Crystal in the theater, and I remember my dad thinking that it was too dark and creepy. I, of course loved it — but then, I'd read and seen Watership Down by that time, which is also considered too troubling for kids.

Priebe:

Without spoiling too much, I will say that as the series continues, it gets darker... and at times it gets weird. The "essence" of Jim Henson and his multi-faceted surrealism, playfulness, philosophy, humor, whimsy, and darkness is all over everything. I think his daughters Lisa and Cheryl have done their father a great service by spearheading this project. Jim would have loved it.

Overstreet:

And that, in itself, makes this new series easier to embrace than the recent Star Wars movies. I have to keep reminding myself, watching the J.J. Abrams and Rian Johnson installments of the Skywalker saga, that this is not the way the story's original visionary imagined things would go. These new films are fan fiction, at best.

Age of Resistance qualifies as 'fan fiction,' in my opinion, in that these are stories that were only partly imagined by the original artist. But there's nothing wrong with fan fiction. Sometimes, the fans have better ideas than the original artists, and in fact they often understand the characters more deeply than the first authors.

Priebe:

Great galloping Gelflings, what they've done here with Dark Crystal goes worlds beyond what Star Wars has become, and as a prequel, these puppets are better actors than anyone George Lucas "directed" in his own prequels especially. Outside of The Last Jedi, which I still love, the new Star Wars films read more like Wikipedia pages and fanboy quote factories. But that's a another conversation for another time.

The Dark Crystal: Age of Resistance honors the original while improving upon it, and unlike most prequels, it doesn't merely exist to show us "how things got that way." For sure, there is still some of that to be found here, but it also graces us with new surprises to explore. Strap yourself in — you're in for a wild ride.

Overstreet:

[long pause]

Okay, I've just watched Age of Resistance: Episode Two, and I'm even more surprised at their willingness to "go there" with the graphic violence. I won't spoil anything specifically, but the last moment of Episode Two might've given me nightmares as a kid.

Priebe:

Just a bit, yes? So awesome, though. I showed that scene to my 10-year-old son, and he literally just said "What the heck? That's creepy." (Had he been a lot younger, I would have been like, "Yyyeah, you're not ready for this."

Overstreet:

More importantly, though, I'm surprised — and a little concerned — at the scale of the storytelling. There are so many characters, so many corners of the world of Thra coming to life, that I hope they don't cast their net so widely that it's hard to develop strong attachments. So far, Deet, Brea, and the Chamberlain seem like the most interesting and fully-developed characters. I'm following them most closely.

But the original only looked back on a story of genocidal violence from the Skeksis, and I guess it's starting to sink in what must be done in the crafting of a prequel series. I've already seen some critics comparing this series to Game of Thrones, and I hope that they aren't going to take it so far that I can't recommend it for middle- and high-school-aged viewers.

Having said that, I'm amazed and delighted to see how the writers are devoted to developing a story that speaks with such immediacy and wisdom into the world's current crises — and that they do so without winking at the audience. (The only clear nod to current events I've caught is when a Skeksis, brazenly stealing from the poor out of sheer cruelty, makes the poor sound like the real problem, and then shouts, "Sad! So sad!")

Priebe:

It's subtle, just enough to be relevant without making it the whole point. I see parallels to our current climate crisis in the dying world of Thra and rulers who deny it so they can hold on to their own power. I think of the "resistance" of young activists like Greta Thunberg traveling across the Atlantic Ocean to fight back (on the same weekend this series is released).

Overstreet:

Shifting our focus from big themes to smaller creative decisions: I was stunned to find out that Simon Pegg is doing the voice of The Chamberlain, that most wicked and conniving of Skeksis, because he's imitating Barry Dennen's voice work from the original perfectly. Similarly, Donna Kimball sounds just like Billie Whitelaw playing the role of Aughra. In both cases, I would've guessed that they'd brought back the same actors.

Priebe:

I know right? I am so amazed by this. Mark Hamill does a pretty wicked Scientist too, and you can tell he's having a great time playing him. The only one who sounds a bit "off" to me is the Ritual Master Skeksis, compared to his original voice by Jerry Nelson (and that's pretty hard to top). The voice cast overall though, it's fantastic.

In the original film, most of the Skeksis are one-note baddies, with only the Chamberlain starring in a few extra scenes to further develop his character. This time, he is developed so much more, and not only him, but other Skeksis as well. The Emperor is far more well-rounded and layered than the snarling Garthim Master was.

Overstreet:

The wildernesses of Thra are coming alive with so many fantastic creatures. I had to laugh at the miniature version of Salacious Crumb who chews up library books, and Anne and I both thought that you've invented so many fantastic monsters and characters in your own work. Do you have any favorites in Age of Resistance so far?

Priebe:

There are so many characters I adored right away, especially Deet and Brea. In Episode Two, I love the Sifa Clan gelflings and the exchange between them and Brea in their tent. They reminded me of Marion and Belloq in Raiders. Other favorites of mine you shall meet in episodes to come!

Overstreet:

Obviously, I need to keep watching to the end. But I'm not a binge-watcher — not at all. When Twin Peaks: The Return came along, and made it last for weeks because I didn't want to wake up to a world in which there were no new episodes. I think I saw you post that yo've already watched this thing all the way through twice!

Priebe:

If I fall in love with a show, the temptation becomes too great, possibly to my detriment. Twin Peaks of course was broadcast a week at a time to begin with, which I do prefer over having access to the entire season at once. I liked having that option of an episode each week. Makes it more of an event, like the old-school ways of television lore. We’ve become very spoiled.

Overstreet:

I just read a wonderful appreciation of this series by RogerEbert.com's Matt Zoller Seitz. He zoomed in on the opening scene of Episode Two, in which a Podling named Hup wakes up, gets dressed, and has breakfast. The attention to detail is glorious.

I'd like to hear from you in more detail, as an animator, what you appreciate most about the emphasis on hand-crafted puppets over digital animation. What's something you notice, as the author of heavy textbooks on the art of stop-animation, that the casual viewer wouldn't appreciate?

Priebe:

What I like about puppets is that they have presence. They are actually there in real space, with real textures, real materials, and real lights hitting them. Whether it be Dark Crystal, the Muppets, Coraline, or Isle of Dogs, I think audiences respond to these characters on a more subconscious level. Seeing real dolls twitching and wiggling onscreen triggers those memory pangs from playing with real stuffed animals, action figures, or dolls as children. We remember the sense of touch from plastic and fur on our fingers, and the weight of them in our hands, imagining they are alive... so when we see them come alive on screen, we relate to it in that way without realizing it.

But with that movement on screen also comes limitations, more so with characters like Kermit or Kira than with Coraline or the Fantastic Mr. Fox. As stop-motion puppets are articulated a frame at a time, with intricate armatures, details like lip sync can be more in tune with actual human speech. When making a sound like ooo or aaaa or ppp, animation can pinch or pucker the mouth for more naturalistic expression. Turn the sound off, and you may still be able to "read the lips" of an animated character, in any medium (2D or 3D included). But turn the sound off on the Muppets or Dark Crystal, and you may think they should sound like the aliens from Mars Attacks!: "ACK ACK ACK ACK." Take that a step further with Mister Rogers' puppets, and their mouths don't even move at all!

For those of us who grew up with Sesame Street, the neighborhood of make-believe, or even one of my childhood obsessions from the '80s, the animatronic characters from The Rock-afire Explosion at Showbiz Pizza Place, we understand this is a different medium and will behave differently. Today's young generation may not tune in to this as much. My own kids even commented at scenes from Age of Resistance that "their mouths are just flapping." I reminded them, it's because they're puppets, even though they've grown up with plenty of Muppets and "old dad-shows" themselves. How quickly we can forget, when the possibilities of digital animation are dominating most of what they see.

And yet, look at Japanese animation! In shows like Pokemon or the feature films of Hiyao Miyazaki, the whole style is based on mouths simply "flapping" without much articulated lip sync. The important thing to these filmmakers is simply that you know who is speaking. Perhaps because the Dark Crystal puppets are more detailed and life-like, we expect it should look more life-like.

But I don't think it needs to. It's still a puppet show. Jim Henson himself said "a puppet is a symbol of whatever you are wanting to portray, therefore an evil character can be totally evil, evil incarnate. You're not dealing with a person or an actor you are imagining in that role. So there's a kind of purity to it."

When we watch a stage play or a physical puppet show, we bring to it a certain suspension of disbelief. Puppet films bring what you would normally do on stage into a cinematic realm where you can have close-ups, cut scenes, and other illusions the stage can't give you. But it still has that texture and presence that digital worlds can't give you. When they try too hard to mimic reality, they fail miserably.

You had a great post recently about the photo-realistic Lion King and that great quote from Georgia O'Keefe: "It is only by selection, by elimination, by emphasis, that we get at the real meaning of things.” I think the same interpretive symbolic nature of puppetry comes into play here, and why we respond to it. That's a rather long-winded answer, but I geek out over this stuff.

Honeyland (2019)

So there I was, sitting on the front porch of a Whidbey Island vacation cabin with two of my favorite writers — let's call them Bret and Scott — and feeling grateful for this rare opportunity to commune with great minds. They were taking turns telling stories about writing and traveling that made me jealous of their experiences.

Bret was commenting on how grateful he was for this rare opportunity to soak up a view of the snow-capped Cascades. So enchanted was he by the sight that he didn't see a large hornet crawling across his wrist. I cringed, then quietly pointed out his bright yellow visitor. He flicked his wrist and the bee flew off.

Since that particular threat looked strangely familiar, I launched into a story of my own: "I've only been stung once — and it makes sense that I would get bee-stung in a movie theater, right?" They blinked at me. "It was like a bad joke," I continued. "I'm standing in line for popcorn, and I feel a needle pierce the base of thumbnail. Feels like it penetrates all the way up to my shoulder. I got through the rest of the movie by numbing my hand in a cup full of ice."

There was an awkward silence.

Then Scott quietly asked, "Well, okay, but... what movie was it?"

Bret started laughing. Then Scott started laughing. Then they both kept on laughing — a lot. Too much, perhaps. And I stayed pretty quiet the rest of the afternoon.

Okay, so my bee-sting story isn't particularly compelling. I get that. Not relative to the stories they were telling, anyway.

Allow me to direct you to a much more compelling story about bee stings that you'll never forget. They happen — again and again and again — in a new film called Honeyland.

Honeyland begins as a startling portrait of an extraordinary beekeeper, and then turns suddenly into a suspenseful drama with life-and-death stakes. And that detail that makes it so much more compelling is this: It's a documentary, comprising footage from four years of attentiveness in the rocky wilderness of the Republic of North Macedonia by the filmmakers Ljubomir Stefanov and Tamara Kotevska.

Their subject, Hatidze Muratova, is a genius — she seems to be known and even welcomed by swarms of bees as she carefully and routinely extracts honeycombs and honey from the rugged rises of rock near her home, leaving plenty behind for the bees to continue their architecture and art. She sings to the bees. She speaks to them. She reminds them of the terms of their contract. It's the central principle of her stewardship: half for her, half for them. And she seems to goes unstung — which is hard to believe, considering the immensity of the swarms and the sizes of those hives that are so impressively concealed in the landscape.