Star Wars: The Rise of Skywalker (2019)

"Don't criticize a film until you've made one."

That's a snarky response I get from time to time — and I suspect that most film critics have heard it as well.

The fact is that there is a tremendous difference between having the skills and vision to make art and the skills and vision to write reviews of art. I've never directed a film, just as I've never managed my own restaurant or played in the NBA. But I think that I have enough understanding of what it takes to run restaurants well, or to play well in the NBA, that I can offer credible perspectives on both. So, yes, having seen several hundred movies a year over the last 30 years, and having taught courses on cinema and storytelling, I don't feel like I'm being presumptuous writing film reviews.

And yet here, on the occasion of the final movie in the nine-film Star Wars saga, I feel like I have a different answer to that common retort: I have written a multi-volume fantasy saga. I have embraced the challenge of bringing a multi-chapter adventure series to a close, choreographing an epic fantasy that involves more than fifty prominent characters to a point of closure.

When I wrote The Ale Boy's Feast, the fourth book in The Auralia Thread, I made myself several promises that would help me avoid the cliches of typical franchise finales: I would not deliver what I'd heard that fans of the series wanted. (Most prominently, I would avoid fulfilling the wishes of young readers who wanted to see so-and-so and so-and-so end up married.) I would avoid thrilling battle scenes that would satisfy the desires of some readers to see certain villains spectacularly destroyed. I would avoid re-staging any kind of scene that had happened before in the series. I would strive to maintain the focus of an artist: I would prioritize discovery over crowdpleasing. I would look for the deeper questions that the previous four novels have been leading us to ask, and then wrestle those questions seriously.

This week, having grown up with the Star Wars saga as one of my formative influences, I approached the final chapter with a familiar sense of apprehension — the same feeling I experienced as I began to outline the fourth and final book in my own epic fantasy.

And so, while I offer this humbly, as one moviegoer's first impressions, I can say that I know a thing or two about the difficulty of concluding a series. And what I saw on Friday morning did everything that I'd sought to avoid in concluding a series of my own.

J. J. Abrams' Star Wars: The Rise of Skywalker, the ninth and (they tell us) final episode in the story arc of the Skywalkers, is like a Star Wars jukebox that suffers from ADD. It generates instantaneous remixes and medleys of the Top 250 moments from earlier installments in the Star Wars series, zigzagging between tracks in a desperate attempt to grant every viewer's nostalgic wishes. Watching the movie is like watching a robot programmed to please fanboys stand at the jukebox and poke buttons rapidly, almost at random, until the audience is exhausted from dopamine hits.

"Do you like chaotic space battles? Ours is the biggest! Do you like jumping to hyperspace? In this movie, we turn that into a pinball-machine rollercoaster from one place to the next! Do you like lightsabers? We have so many, including multiple sabers for multiple characters! Cantina scenes? Check! Playing chess on the Millennium Falcon? Uh-huh! Do you like nostalgic cameos? We've got almost all of the previous ones again, and more besides! Heroes getting tazed by Force Lightning? Brace yourself — Force Lightning can do more than you've dreamed in your worst nightmares! Death Star cannons destroying whole planets? Oh, just you wait. The shrinking of the Star Wars universe with even more unexpected family connections? Hey, we promise to give you everything you've enjoyed before. New ideas? Um... well, we only have so much time, folks."

That's right. At no point from this ADD jukebox do we ever hear a whole verse, a whole chorus, or anything resembling a new melody sung.

Where the original Star Wars trilogy was inspiring, exciting, and innovative (and, for many of us who grew up with it, personally meaningful in ways that are difficult to quantify), it led to a series of consistently disappointing prequels and sequels. I'm among those who highlight one notable exception: Rian Johnson's The Last Jedi, a movie that rekindled my enthusiasm by making some brave and exciting storytelling choices and giving me a sense that Star Wars could still surprise me.

And now, the nine-film saga has "concluded" with its most preposterously derivative chapters, one of the most overstuffed franchise films, one of the most beat-for-beat frustrating movies I've ever suffered through. I doubt that I'll ever bring myself to sit through it again — and that's something I've never said about a Star Wars movie.

So, in the spirit of J. J. Abrams's The Rise of Skywalker, I'm going to present the rest of this review as an imitation of the movie itself: That is, instead of writing an original film review of my own ideas, I'm just going to post a bunch of things that have been said about the film already, observations and opinions you can find elsewhere. I've chosen them because they resonate with my own experience of the film, just as Abrams has built his movie out of moments that he knows fans liked in other movies.

Some of these quotations may contradict each other here and there... like the movie does. There may not be much rhyme or reason to the pace of this quotation collection, and transitions may be be jarring. The movie's like that, too. And while you may at times be entertained by what these critics say, you will probably end up exhausted by just how many links I'm offering. (The movie exhausted me by busying itself with links to earlier ideas.)

This is what happens when a movie that is made by an artist interested in discoveries and challenges is followed by one carefully calculated by a committee to reproduce things that have happened before. In the committee's desperation to please everybody — "You love this kind of thing, don't you? Well, here it is again, but super-sized!" — they end up embarrassing itself.

Here we go.

And no, I didn't go looking for negative reviews. I just walked around the neighborhood of critics — professional and otherwise — whose perspectives have won my respect over time. This is what they've said so far:

Alissa Wilkinson at Vox:

If I sound exhausted, it’s honestly because I am. Is this what audiences demand from franchise movies? Films that cater to what’s comfortable and capitulates to the most unimaginative fans? That feel as if they’re just ticking boxes on a checklist? You could say I’m taking this too seriously, but I think a series as important to movies — and to millions of people — as Star Wars deserves to be taken seriously.

I could say some other stuff about The Rise of Skywalker. About its insistence on a morally simple universe where you’re either dark or light, but you only get to be on one side. About its continued mixing of gnostic and biblical imagery, but without a lot to say about either. About how it could have said something intriguing about our contemporary culture, power, or empires, but just doggedly insists on broadcasting the same two messages that Disney movies fall back on time and time again: first, that you have to believe in yourself, and second, that the real Force was the friends we made along the way.

Joel Mayward at Cinemayward:

If the dead speak in Rise of Skywalker, they have nothing bold or interesting to say. I find its lack of faith—in its audience, in its predecessors, in itself—disturbing.

Calum Marsh (often published at The National Post, Variety, The Guardian, Pitchfork, etc.) at Letterboxd:

I don’t want to sound melodramatic — and I say this as someone who found The Last Jedi wildly misjudged and frequently ridiculous — but I really think this might go down as some kind of pop cultural turning point or (more optimistically) the nadir of a corporate-minded, focus-grouped, fan-indulging age. Boring and utterly abysmal. Glad this is over.

Sarah Welch-Larson at Letterboxd:

I think the problem with Star Wars in general is that it has a scale problem. If the last movie had a Death Star, the next one needs a bigger badder one; if the bigger badder one got blown up, then we should miniaturize the Death Star tech and bolt it on the outside of a cruiser. The problem with this approach is that there's nowhere to go once you've decided to raise the stakes by amping up the scale of destruction. What good is ruling the galaxy if all you're going to do is actively destroy it, planet by planet?

The problem with this Star Wars in particular is that it, to quote Palpatine, suffers from a lack of vision. The scale problem is partially to blame, but the more disappointing issue is that the script ties itself into knots trying to get Rian Johnson's wild left turns back under a control that they never needed. The Last Jedi was so brilliant because it abandoned the Star Wars playbook. It tried new things; it left the calcified idea of the Force as an inherited trait behind. Anyone could be a Jedi again, including street urchins and nobodies. The Rise of Skywalker throws all that away for a plot twist that is uninteresting and obvious. I don't want to know how Rey got her potential. I just want to know what she's going to do with it now that she's tapped it.

Vadiim Rizov at Filmmaker:

A serial of serials, The Rise of Skywalker is a calamitously overstuffed series of exposition dumps, relentless incident and canon box-checking, like watching someone who’s on four hours of sleep and three Red Bulls try to do an immense task in as little time as possible so they can crash again—the movie is barreling through about three times as much information as it could reasonably bear.

Scott Renshaw at City Weekly:

... [T]he elephant-in-the-Throne-Room problem with The Rise of Skywalker is that it’s not so much Abrams’ attempt at wrapping up Star Wars’ Skywalker saga as it is his cover-band attempt to play all of the hits, specifically the hits from Return of the Jedi. ... The Last Jedi divided fans because it broke with the idea of destiny, and placed characters in the position of challenging their preconceptions to make hard choices. The Rise of Skywalker simply puts those characters through the motions of character arcs we’ve seen before, meaning that we all get a comforting pat on the head without any surprises. It’s a story that’s frantic, frustrating and, most disappointingly, absolutely conventional in every possible way.

Sean Burns at North Shore Films:

The elephant in the room here is that they accidentally made a real movie last time. So of course J.J. Abrams was brought back on board to make sure nothing like that ever happens again. Alas, we’re back to the monomyth and old, tiresome prophecies about chosen ones who will bring balance and everyone in this entire universe is f----ing related.

David Ehrlich on Letterboxd:

spiritually corrupt, but — BUT! — also flat and artless in a way that not even the worst Star Wars movies have been before.

thanks to paternity leave, i have no professional obligation to keep thinking about this hugely disappointing capitulation to the most feckless elements of studio filmmaking. and so i won't.

Jake Cole on Letterboxd:

Kennedy's shepherding of Lucasfilm has been so profoundly mercenary that not only has nearly every filmmaker tapped to helm one of these features stepped down or been removed for having the audacity to try to bring a personal voice to this franchise, but all of them have subsequently been the targets of entire PR campaigns meant to discredit them. Rian Johnson somehow slipped under the radar with a truly unique, worthwhile contribution to George Lucas's unwieldy universe, and he has been rewarded for it with years of navigating fan backlash on his lonesome and a press rollout for this follow-up that has taken numerous potshots at his film to reassure angry fans that things will end "correctly."

That spirit infuses The Rise of Skywalker, the most soulless entry of the Disney era of Star Wars and perhaps the new prime example of how this age of filmmaking has brutally jettisoned vision and surprise for slavish devotion to IP and what a bunch of executives think you, the stupid public, want to see. This is two and a half hours of nonstop stuff, incessant exposition that flits through scenes designed to micro-target every possible fan-service desire at the expense of coherence or meaning. It actively unravels The Last Jedi's bold revisions and thematic questions, cooing into the audience's ear that everything will be as they want again, like massaging a pill down a dog's throat.

Brian Tallerico at RogerEbert.com:

Opinion is going to be shaped a lot by the fact that JJ made a sequel to his Star Wars film instead of the last Star Wars film.

Josh Larsen at Larsen on Film:

Rise of Skywalker is a mess in terms of actual plot. It gets off to a clunky start, with frantically paced table-setting scenes that offer a lot of CGI and action but never really capture the imagination. The movie then proceeds to assign a series of busy tasks to its ensemble cast, who are sent across space in search of various MacGuffins, doohickies, and dongles. (At one point, they need to retrieve a dagger because it offers a clue to a “wayfinder” that will guide them to a hidden location.) After all that is accomplished, the film works its way to a convoluted, confusing climax that nonetheless restages the finale of 1983’s Return of the Jedi....

And I'll give the last word to Steven D. Greydanus at The National Catholic Register, with whom I've been arguing about Star Wars since before The Phantom Menace:

Abrams ... seems bent on undoing his own actions, on avoiding meaningful narrative choices of any kind. Again and again he seems to cross a line only to backtrack, until it becomes comical.

Perhaps the film’s one real creative goal is not to alienate or upset anyone, which sometimes means alienating everyone. ... It’s a film not only at war with its predecessor but also with itself.

This eventually becomes a fatal problem as it becomes clear that Abrams has no clear idea how or why good triumphs over evil. George Lucas’ conceit in the original Star Wars was that Imperial military-industrial groupthink discounted the power of the individual. In Return of the Jedi, the power of love proved stronger than the dark side (and low-tech indigenous resistance proved more creative and adaptable than technologically superior but less nimble imperial occupiers).

Two ideas wrestle in Rise: Does good triumph over evil through the power of friendship or does everything come down to the awesomeness of special people from special families? I’m not saying it can’t be both, but Abrams trips over his two ideas and one of them falls flat before being crushed by the other one.

The wrong one, in my opinion.

I'll add more as I come across them.

But I'm not going to put myself through the painful process of cataloguing all of the ways in which this movie falls short. It staggers the imagination that a movie like this, which could have brought some of the greatest imaginations in the world to the table, and which could have drawn upon nearly infinite resources to achieve a great vision, could end up such a mess. But it's Christmas, and I intend to focus on what I'm thankful for — including other new movies like Knives Out, A Hidden Life, I Heard You Paint Houses, Waves, Dark Waters, the new version of Little Women that I can't wait to see.

As I walked out of the theater, I had to stop and pay my respects. There was a spectacular Knives Out display right there beside the exit. It was salt in the wound, reminding me of all that might have been.

I think I'll go see Knives Out again. Happy Life Day, everybody!

My #1 Christmas gift recommendation — and five reasons why

"Those who can't do... teach!"

Okay, it's a bad joke, and a tired one. But today, it's ringing true.

I just spent Autumn Quarter teaching undergraduates how to condense and concentrate their writing. "Less is more!" "One distinctive detail is worth a dozen unremarkable details."

And just as I was finishing up my grades, I got an email asking for my help with a small task. Would I mind making a quick list of five highlights from more than 20 years of reading Image? All they needed was a list, and then a one-sentence note about why I'd made each choice.

Simple, right? How could I say no?

Well, here's the thing. I love Image. And If you want my favorite recommendation for a Christmas gift, it's this: a subscription to Image journal.

I think it's the greatest literary arts journal in the world. I also love the Image community, a vast network of artists and seekers who are interested in creativity, beauty, mystery, and faith. And I regularly attend Image events that celebrate the arts. But none of this would exist without the house that Gregory and Suzanne Wolfe built: the journal, now more than 100 issues old. Beautiful printed work like this is increasingly rare, and I find that my heart rate accelerates when I open the mailbox and find something beautiful there, something that I can enjoy for hours and then set on my nightstand for re-reading.

So, forsaking my "Less is more!" mantra, I started writing. And I just kept writing.

I ended up writing something that was so far above and beyond what they'd requested, it wouldn't fit in the publication they were preparing. (They ended up publishing a much-abridged version.)

So, here — in more detail — are my five highlights of Image. (And I could say more. Believe me.)

Provocative Art

From the poetry of Scott Cairns (in so many issues, and featured in this episode of the Image podcast)...

to the vividly astonishing visual art of Kim Alexander (Image #81)...

to photography, fiction, and creative nonfiction,

I am always challenged by the art featured in Image.

But I'm particularly grateful for the short story "Loud Lake" (Image #29) by Image's own executive editor Mary Kenagy Mitchell. (You can read an excerpt from the story here.) I like to challenge my creative writing students by introducing them to this story of childhood, summertime, and Christian ministry. Mitchell achieves a sort of minor miracle: an example of fiction about evangelical Christians that never becomes preachy or propagandistic, but that instead encourages readers to revisit questions of faith that are meaningfully discomforting.

The Prophetic Voice of Gregory Wolfe

Gregory Wolfe, the founder of Image, has been tremendously influential in my life. He directed Seattle Pacific University's Master of Fine Arts in Creative Writing program, through which I earned my MFA in creative nonfiction and my wife Anne earned hers in poetry. He established The Glen Workshop, the annual arts retreat that Anne and I have attended over sixteen consecutive summers in Santa Fe, New Mexico, coming to know the most inspiring and rewarding community of artists we've ever encountered. And the regular Editorial Statements he wrote to introduce each issue of Image for nearly one hundred issues became for me, and for my appreciation of the arts, some of the most challenging and influential reading.

One prime example of this insight can be found in Wolfe's essay "The Cave and the Cathedral," in which he reflects on the purpose of artmaking in human society from evidence in the prehistoric paintings of Chauvet Cave, artwork that scientists believe to be over thirty thousand years old. He also presented this as a keynote address at the Glen Workshop.

But my favorite example can be found in an essay from Image #34, called "The Painter of LiteTM." In that essay, Wolfe finds in the paintings of Thomas Kinkade a troubling premonition: He warns that an increasing reliance on comfort and nostalgia in American Christianity creates a danger that could lead the church down a dangerous path toward supporting a toxic nationalism, white supremacy, and other correlations with Nazism.

At the time, the essay was controversial, and I still find many readers—I assign this essay to my students for a rhetorical analysis assignment—who think that Wolfe is merely mocking pictures that they find innocently heart-warming. But here we are: This kind of art is most popular in the very communities that are now endorsing a vision for America that loudly affirms convictions consistent with white supremacy and Nazism. (And, contrary to the reflexive dismissals of readers, I find Wolfe to be self-effacing and reluctant to cast judgement in the essay.)

Wolfe now focuses his attention on crafting and publishing beautiful books at Slant Books, and James K.A. Smith, the new editor in chief, is carrying on the tradition of provocative “openers” for Image. I recently assigned Smith's "In Praise of Boredom" to my academic writing students and asked them to respond.

I recommend that you collect them all.

Testimonies from Artists: "Attention is Love."

So many insights published in Image come to mind when I think of the words of Sister Mary Joan, played by Lois Smith in Greta Gerwig's film Lady Bird. The benevolent nun looks the agitated teenager in the eye and insists that, by the evidence of the detail in the young woman's rant about Sacramento, that she clearly loves her hometown. The teen is skeptical, admitting only that she pays attention. But Sister Mary Joan wins the day with this question: “Don’t you think they’re the same thing? Love and attention?”

In Brian Volck's essay "No Better Place to End" (Image #85), a writer who is a poet and a physical turns his attention to the world of science and restores in himself and his readers a sense of the sacred: "The sciences and faith speak different languages and shouldn’t be expected to say identical things in identical words. They’re musical lines in a polyphonic score where pungent dissonances enliven overarching harmony. In describing, in their own ways, the nature of things, they remind us how all we take for granted is, in fact, utterly contingent."

In Robert Cording's essay "Acts of Attention: On Poetry and Spirituality" (Image #101), the poet reflects on our increasing inclinations toward (or addiction to) narcissism, and writes the following:

To encounter ourselves everywhere we go is, of course, to lose all sense of wonder. Perhaps wonder begins with paying attention to our experience of being alive.

...

I think we come to know the world not by detaching ourselves from our felt experience, but by inhabiting our bodily experience as richly and wakefully as we can. In this manner, an act of attention involves a kind of paradox: as the Polish poet and Nobel Laureate Czeslaw Milosz writes, “When a thing is truly seen, seen intensely, it remains with us forever and astonishes us, even though it would appear there is nothing astonishing about it."

...

I think the best art always involves such loving attention to what is before us.

Image Interviews

I never tire of reading interviews with accomplished artists in Image. So many quotable insights fill my commonplace books that have come from such conversations. I hardly know where to start.

Consider this meeting of cinematic giants: Scott Derrickson, who would go on to direct Sinister and Doctor Strange, interviewed his friend and mentor Wim Winders, director of Paris, Texas and Wings of Desire in Image #35.

Consider the camaraderie and wisdom among songwriters we find in Joe Henry's interview with Linford Detweiler (Image #99), and then with Detweiler's earlier interview with Henry (Image 71).

Consider the conversation between poets in Anne M. Doe Overstreet's interview with Luci Shaw (Image #75), and then Luci Shaw's interview with her friend Pastor Eugene Peterson (Image #62).

I've learned so much from interviewing mentors and friends for Image. Here are a few of those:

For Image #60, I interviewed my favorite rock star, Sam Phillips, whose music and insights have been a formative influence in my life.

And then I interviewed a former high school classmate—photographer Fritz Liedtke—for Image #78.

My conversation with sound engineer Pete Horner was published as a two part interview at Image's blog Good Letters. Read Part One and Part Two. (If the title of this entry, "All of It Was Music," sounds familiar, that's because Horner's words became the inspiration for a song by Over the Rhine — just another example of how one artist's wisdom inspires others' creative work in the Image community.)

Communal Experiences of Inspiration and Epiphany

I cannot emphasize enough how our experiences with art and insight are amplified when we share them in community with kindred spirits.

Anne and I have been blessed time and time again by live music offered by Over the Rhine, Bruce Cockburn, Joe Henry, and Liz Vice, to name a few. We have been enthralled and humbled by artist Barry Moser's bold testimonies of faith, doubt, and the realization of racism in the context of his childhood.

But the testimony that stays with me most powerfully is a lecture about finding understanding and purpose in pain, a Glen Workshop keynote address given by Scott Cairns that he then expanded into a book called The End of Suffering that I have read many times and given to so many people.

You can read a transcript of that address in Image 52, and you'll see what I mean.

Light from Light (2019)

"Ideas are like fish," says filmmaker David Lynch. "If you want to catch little fish, you can stay in the shallow water. But if you want to catch the big fish, you've got to go deeper."

I don't know if filmmaker Paul Harrill has read Lynch's book Catching the Big Fish: Meditation, Consciousness, and Creativity. But I thought about those lines when I watched Harrill's new film Light From Light, which begins in a genre that often stays in the shallows but then very quickly strides into far deeper waters, its nets prepared to capture large and mysterious ideas.

More specifically, I thought of it as I watched Richard, a man burdened with grief over the recent death of his wife Suzanne, going through the simple rituals of his day job working as a Tennessee fish warden. He works with a small team that sifts waterways for fish, retrieving them and then relocating them. And then, at home, Richard sifts the emptiness of his quiet, spacious house, searching for recurrences of strange phenomena that have made him suspect that Suzanne has come home... as a ghost.

When your house keys move across the kitchen counter on their own, and when lights start flickering without apparent cause... who ya gonna call?

And, more importantly, what will you do if you catch a ghost? Keep her? Let her go?

Yes, Richard (played with endearing solemnity by comedian Jim Gaffigan) is bound to partner with ghostbusters. More specifically, one ghostbuster — a young woman named Shelia (it's pronounced 'SHE-la,' but the character spells out her name S-H-E-L-I-A, and the end credits confirm that spelling). Shelia (Marin Ireland) has worked with paranormal investigation teams before, but happens to be "between groups" right now. She doesn't necessarily believe in ghosts; she admits uncertainty in the radio interview that opens the film. But she wants to know whether she can believe in them or not. So, when her radio interview gets the attention of Richard's priest, she soon finds herself taking notes on a possible haunting.

Most mainstream moviemakers would take this premise and head straight for the jump-scares. And, let's face it — they'd probably also tease us with the potential of romantic chemistry between Richard and Shelia. But Harrill makes no moves to cultivate a love story between them — Richard is too wounded and Shelia is too preoccupied with her own history of losses, and he's wise to keep them focused. We don't get a lot of detail about either character — just enough to know that Richard deeply loved Suzanne and longs to connect with her again, and that Shelia's love life has been a discouraging series of disappointments.

No, this is not, after all, a film about ghosts, although the possibility of a ghost is what brings Shelia and Richard together for soul-searching and friendship. This is a film about daring to risk belief in spite of failures. Shelia is so jaded on the subject of love that she can't resist interfering in the budding relationship between her son Owen (Josh Wiggins, winningly awkward) and his sweetheart Lucy (the radiant Atheena Frizzell). "I just don't want you to get hurt," Shelia tells him. And her attitude has consequences. Soon, Owen is indoctrinated: "What's the point of falling in love if it's not going to last?" he asks, much to Lucy's disappointment.

And yet, for all of her insistence on permanence and certainty, Shelia seems driven to track rumors of ghosts, setting up cameras and microphones, and stalking the shadows of Richard's house by night, repeating an earnest appeal: "If you want to communicate, let yourself be known."

She says this so many times that we're clearly meant to note the irony: Shelia isn't interested in letting herself be known. That would require vulnerability and the possibility of harm — more harm.

And there's further irony shouting from the walls of her workplace: Shelia works at a rental car counter at the airport, the company's name "Alliance" printed in bold all around her. (To deepen the visual metaphors, she has a clear view of the airlines' luggage conveyors — she regularly watches people claiming their, um... baggage.)

Nevertheless, the most meaningful moments in the movie clearly come when Shelia lets down her guard and opens up to Richard, or when she attends to his awkward testimonies about marriage, failure, and grief.

And young Lucy, meanwhile, is all about knowing and being known: She's preparing a presentation for school on Japanese tea ceremonies, and in rehearsing it for Owen it's clear that she's inviting him into intimacy. (She emphasizes that ceremony participants typically pass through a small door that requires them to kneel — a posture of humility that brings “everyone to an equal level.”)

For all of this talk about making contact with the dearly departed, the movie keeps insisting on the value of the present and attentive. Both involve risk, and both can lead to harmful discoveries. But love is impossible without faith, and faith is risk — it's a gamble, a choice to live in confidence of something hoped for, a choice to make choices based on things uncertain and unseen. Love leans us forward, a posture that causes a lot of strain and sometimes topples us over.

I lean forward when I see the forested hills of Tennessee engulfed in fog — so beautifully and quietly captured by Harrill's cameras — so that rise beyond rise is fainter, more uncertain, until the hills vanish into a blur. I remember this view. In 2013, I sat on Lookout Mountain on the border of Georgia and Tennessee, wrapped in a wool coat and scarf, watching a dream of October colors emerge from the mist and then disappear into it again, as if they were mere suggestions, rough drafts of possible worlds that God was painting and then painting over again. I felt like I was present for the making of the world. I felt like I was in that in-between place, of this world and the next. I wondered if this was what it might feel like in the ferryboat crossing from death into life. And, strangely, I found myself wanting to write stories. Ideas were swimming in my imagination with a vividness I hadn't experienced in many years. Forgive me, I can't help but use the phrase: In this liminal space, big fish were begging to be caught.

No wonder Harrill sets his distinctive story of ghostbusters in this territory. He knows that here, whether his characters find any ghosts or not, they will be revealed themselves as luminous beings.

Shelia wants to apply scientific instruments to the purpose of confirming the unknown: Her mind wants certainties that she can explain. But when she's asked about her professional credentials, she furrows her brow and says, "I don't know what I am." As Shelia, Marin Ireland (who also makes a strong impression during a fleeting appearance in Martin Scorsese's The Irishman) gives a performance that reminds me of the great Marion Cotillard. It's what critics like to call “understated” — she portrays Shelia as withdrawn into herself, uncomfortable with intimacy. She acts with her jaw, which shifts and clenches with tension and discomfort as if always fighting to align what has been offset.

In my notes, I scribbled about two key moments at which Sheila lets her guard down. In both, she is leaning against a bright space with a stark block of deep darkness on the right side of the screen. During the first, she opens up and describes a personal experience that shook her, that cracked her skepticism, that inclined her to believe. And she is right between the light and the dark, the known and the unknown, looking out as if for confirmation. On the second occasion, she leans back into the bright side of the screen and looks upward, as if receiving a revelation in the Here and Now. It may mark a progression — it may not. But in both, in words or in tears, she is open. She is letting herself be known.

Richard, by contrast, is a man of deep emotion; he feels things, but he not strong on making sense of them. Gaffigan's performance is endearing and modest; he doesn't go for any Big "For Your Consideration" Moments. He makes Richard seem like a man who has become half-a-ghost himself during the harrowing and hollowing of his loss.

He needs Shelia, and she needs him. Harrill seems to suggest that, for all of the films we see every year that investigate the paranormal, few have even begun to reveal the mysteries of the living, breathing human beings in their foregrounds.

The poet Scott Cairns has written about a word in Greek for which English has no equivalent: nous. The nous, he explains, is "the heart’s intellective aptitude" that lies "dormant" unless we "find a way to wake it." (Read his poem about it here.) It's not a sixth sense: Rather, the nous is the place where our mind and heart meet and work things out in a relationship of two distinct human powers. It's where head and heart develop a common language, and a new way of being is born.

Some movies about ghosts are puzzles for the mind to solve, and others appeal to evoke emotions. Harrill's movie suggests that the best place for close encounters lies in the space between strangers, and in the borderlands between mind and heart. There, we can commune more profoundly, and know in ways that cannot be reduced to paraphrase.

Regardless of their successes or failures in ghost-busting, Richard and Shelia are "meeting on an equal level" and "making themselves known." And in their uncertain communion, they are finding new occasions of healing and hope.

These things don't happen with the typical thunder and lightning of big-screen drama. So, appropriately, Light from Light isn't the stuff of sensational big-screen crowdpleasers. The work it does is something subtler. When I watched this film with three friends, we didn't have the rousing rave-fest I had hoped for as the credits rolled. We wrestled with a few lingering questions. And I rashly concluded that I was more puzzled than inspired, honestly. Then we moved on to the more pressing demands of our days.

But that was weeks ago. And very little else in my year at the movies has stayed so vividly on my mind as Light from Light. It's haunting me. And the more I write about it — I'm going to make myself draw this review to a close now, hoping my nets of words have caught a useful idea or two — the more illuminating the movie and its mysteries become.

You might call this personal reflection "Light from Light from Light." It's what I've caught in these deep currents, currents that are still in motion.

A Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood (2019)

Madeleine L'Engle was a complicated human.

I know we're here to talk about the Mr. Rogers movie, but bear with me: I'll get to that.

When Disney's so-so film adaptation of L'Engle's beloved novel A Wrinkle in Time came out a couple of years ago, I found myself cringing through the hype, as adoring testimonies about the author's books and influence rolled in, wave upon wave. I've read so much of her work, and I am close to so many people who knew her well. My understanding of her character and influence tell me that she deserves to be admired and celebrated, but also that we must wrestle with the complexities, the rough edges, and the increasingly irascible nature of her personality as she grew older. When our heroes pass, it's important that we honor them — but it's also important that we avoid romanticizing the reality, reducing our portraits to sentimentality.

Having said that, I must admit that I quote Madeleine L'Engle's wisdom as much or more than anybody's. Not a week goes by that I don't quote — aloud or in writing — the wisdom of her book Walking on Water: Reflections on Faith and Art. And many of the lines that mean most to me have something to say about misconceptions related to age. Advising writers who are wrestling with complex concepts, L'Engle writes, "You have to write the book that wants to be written. And if the book will be too difficult for grown-ups, then you write it for children."

L'Engle knew that it's a sin to talk down to children. She knew that children have a capacity for understanding some things better than adults do. And adults, attending to words that have been crafted for children, just might be surprised by insights they would otherwise have brushed off.

And I thought about that a lot as I watched director Marielle Heller's film A Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood.

Here's a film that takes a complicated story about adults in conflict and frames it as if it's the focus of an episode of children's television. No, I don't mean the movie's styled like the hyperactive, seizure-inducing children's entertainment of today, but rather it's played in the mode of the patient, modest, and deeply nourishing educational television provided by Fred Rogers from 1968 through 2001.

Let's be more specific:

The movie introduces Lloyd Vogler (Matthew Rhys), a journalist for Esquire magazine, who is happily married to Andrea (Susan Kelechi Watson)' unhappily clashing with his estranged father (Chris Cooper); intolerant of his father's girlfriend (Wendy Makkena); and trying to make his peace with his own new role as a father. Their family tensions are just mundane enough (and just realistic enough, actually) to make for forgettable drama — but what makes them interesting is how their story is introduced by, and eventually visited by, a sort of guardian angel who just might bring this warring tribe around into an affirmation that, yes indeed, it is a wonderful life.

That soft-spoken savior, who earned his wings a long time ago, and whose guardian-angel status was celebrated just last year in the extraordinarily moving documentary Won't You Be My Neighbor?, is, of course, Mr. Rogers — the educator, psychologist, pastor, and television host we associate with bringing peace, truth, and love to small children.

What A Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood bravely asserts is that Fred Rogers' wisdom is just as applicable for grownups now as it has ever been for children. Lloyd, initially insulted by the assignment to apply his sophisticated talents to writing a "puff piece" on Mr. Rogers, ends up seeking escape in his assignment, escape from the crises awaiting him at home, as his living nightmare of a father hovers outside his apartment building and asking "Can we talk?", and as his wife becomes increasingly exasperated with Lloyd's unwillingness to listen, to offer second chances, to consider reconciliation.

And so, little by little, as Lloyd's interviews with Fred Rogers progress, he careens between incredulity at Rogers' childlike preoccupation with puppets, frustration with Rogers' evasion of challenges to his authenticity, and bewilderment with Rogers' ability to turn the interview around and slip through gaps in the wall of Lloyd's cynicism.

Everything about this premise would incline me to believe that Heller's movie would seem condescending to its adult audience. I was braced for a barrage of oversimplifications meant to resolve tensions in a a complicated reality. and for platitudes likely to inspire more cynicism than healing.

But something kept me hopeful. I'd seen Heller's last film — Can You Ever Forgive Me?, the messy and difficult portrait of author and fraud artist Lee Israel. And I couldn't imagine that this director would settle for something sentimental and sticky.

She hasn't.

In fact, Heller makes things unexpectedly exciting in that she isn't content to provide a mere imitation of Fred Rogers' tenderness, creativity, and imagination.

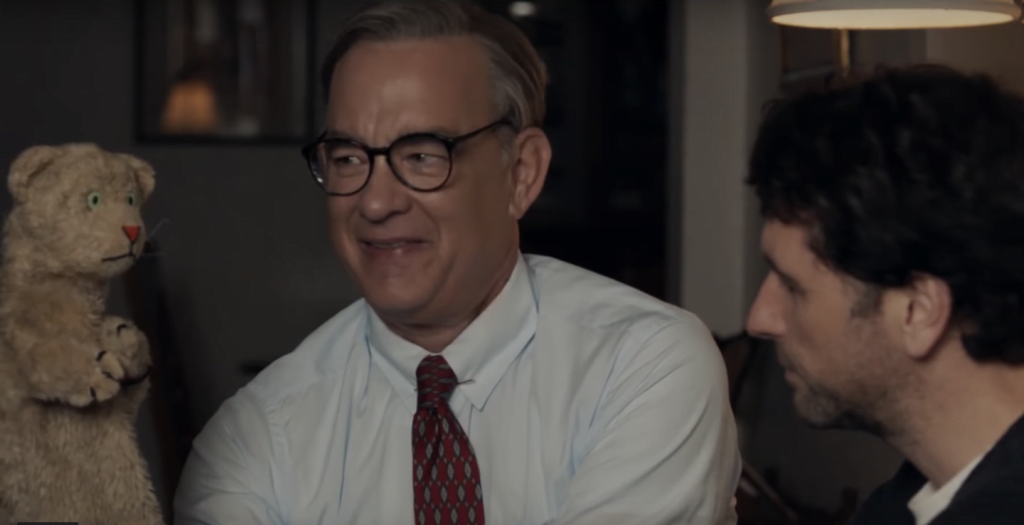

I could take time here to join the 99.9% of working film critics to sing Tom Hanks's praises: his performance is a thing of tenderness, precision, and beauty. Specifically, I would point to what Steven Greydnaus has written at The National Catholic Register:

Why does the performance feel right? Hanks commits utterly to Rogers’ sincerity, soft-spokenness and gentleness of spirit — but it’s not only his acting choices. It’s also who he is.

Another actor might look more like Rogers or nail the technical details more precisely, but no one else in Hollywood has the store of goodwill and trust to connect emotionally with viewers as Rogers. I believe in Mr. Rogers as I believe in few human beings, but, while he isn’t on that rarefied level, I believe in Tom Hanks, too. And so do most of you.

But why dwell on what's obvious? We know Hanks will be awesome in the role.

Marielle Heller, on the other hand, needs a bright spotlight. So few women have opportunities to direct pop culture events as significant as this one. And Heller isn't content just to give the people what they want: She, working with a brave script from Transparent and Maleficent screenwriters Micah Fitzerman and Noah Harpster, takes real risks from the very opening scene. She asks us to engage in some imagination games (just as Rogers would have wanted it!). She asks audiences to reckon with the public prominence of Rogers' Christian faith and his dedication to prayer (which are portrayed here as clearly as they have been in any Martin Luther King biopic). Then, later, she asks us to lean into just how strange this guy was.

And in a scene right at the heart of the movie, she takes a risk bigger than any I've seen at the movies this year. I won't spoil it for you, but I'll say this: the gamble plays off — big time. I watched the film at home via screener link, and I can't wait to experience it again in a crowded theater just to see how that meditative minute plays for an audience.

So I was right to feel some strange confidence that Heller might be the right filmmaker for the job. And, what's more, I didn't feel like doubting the drama about the journalist and the children's entertainer, as the whole affair is loosely based on — or, better, inspired by — the experiences of journalist Tom Junod, whose testimonies about his relationship with Rogers are already legendary.

That doesn't mean I think the whole endeavor is an unqualified success. There are a few moments when the movie loses its careful balance:

First, Heller can't quite resist the temptation to drop Tom Hanks into actual historic footage of Rogers on various television shows, and the Forrest Gump-ishness of things becomes impossible to ignore. They should have known better.

Second, there's a dream sequence that made me wonder if the whimsical filmmaker Michel Gondry had seized the controls. I love the land of make-believe, but this movie asks us to accept some wildly dissonant modes. This stretch of the film is the only one that had me wincing at its contrivance—at least on this first viewing.

After that awkward stumble, the film regains its footing for a while — and then, in the final act, when Lessons are Learned, it veers dangerously close to the edge of the Abyss of Sentimentality.

But don't worry — it pulls back in time. and the whole journey is worth it for a masterful denouement that brings all of Fred's threads — the actor, the counselor, the director, the musician, the public, the private, the enigma, the tenderness, and, yes, the anger — together for a final flourish.

I'm not quite ready to call the movie a Christmas Miracle. But it's certainly appropriate to call it a great Thanksgiving movie — one for families to share during a season when they're bringing all their baggage to holiday dinner tables. While Morgan Neville's documentary took me to pieces and left me quaking with gratitude for Rogers' ministry, here my feelings of thankfulness are for Heller, Junod, Fitzerman, and Harpster — that they were able to save us from what seemed inevitable: an intolerably hagiographic portrait. Their work faces head-on the discomforting questions we must reckon with as we try to make sense of so singular and complicated a celebrity.

I saw A Beautiful Day on the very same afternoon that I saw Martin Scorsese's I Heard You Paint Houses. After my immersion in Scorsese's testimony about how gangsters have shaped American politics over many decades, I was braced for a Mr. Rogers movie to fall flat, to feel flimsy and squishy and crowdpleasing. Now, I can't help but wonder if, after watching 3 1/2 hours of mob madness, two hours of Fred Rogers' weaponized kindness didn't seem even more necessary.

Writing about her enduring affection for children’s stories, Madeleine L'Engle insisted that her age was not an isolated chronological statistic, but only the most recent addition of a year to her life: “I am also four, and twelve, and fifteen, and twenty-three, and thirty-one, and forty-five and . . . and . . . and . . .” A Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood is founded on this conviction: that a grown man, no matter how cynical, is just the latest revision of a project that began as a child, and that there still is, somewhere within the accretion of years of defensiveness and dismissals, the same vulnerable and needy human being who has always been waiting for love to take root, to grow, and to break apart the despairing cynic's carefully cultivated exoskeleton.

The power of that love works on Lloyd. And I suspect it will work like a sledgehammer on all but the hardest hearts in the audience.

As one of the millions whose childhoods were shaped, in large part, by Rogers' kindness and childlike imagination, I can tell you that it certainly worked on me. For I'm a cynical forty-something journalist at times. But I am also twenty-one, and twelve... and a wide-eyed four-year-old, leaning in toward the TV screen, listening to the Gospel of Daniel Tiger.

NOTE:

If it had been made back in the heyday of progressive Christian film criticism — that being the early- to mid-2000s, when writers were reclaiming the ideals of criticism from a Culture of Fear (that is, from the Focus-on-the-Family-variety morality police) and focusing instead on the Art of Cinema — I suspect that A Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood would have started fires. What a debate we would have had.

Frankly, I wouldn't be surprised if it stirs up debate among Christians today.

On the one hand, Christian congregations will love it the way they loved Chariots of Fire. They get to see a Christian hero modeling Christian humility, quoting and cherishing the Christian Scriptures, and kneeling at his bedside to pray for people. They'll claim him as a sort of standard-bearer: Everybody loves him, but he plays for our team!

On the other hand, it shows Rogers engaging the world of the arts, crossing borders, and loving everyone instead of endorsing a cultural separatism. His example stands in stark contrast to what much of evangelical America is endorsing these days. (In fact, the FOX News “Fox & Friends” morning program ran a story in which they called Rogers an "evil, evil man" for assuring children that they are all special.) Thus, it would be easy to hold Rogers up as a poster boy for all forms of progressive politics.

But I don't want to get drawn into this tempting tempest of partisanship. I'll just say this: Rogers has one thing very much in common with Jesus — people of all political stripes want to exploit his goodness in ways that endorse their own views. And there he is in the middle: an enigma, asking only that we love one another, and love everyone with equal devotion.

To seize this film and wave it as a flag of partisanship — religious or political — would be a terrible, terrible way to read the film.

Ford v Ferrari (2019)

“He's pushing the car too hard! That wasn't the plan!”

“Plans change.”

That's really all you need to know about the writing in Ford v. Ferrari, the new fast and furious film about how the Ford Motor Company schemed to pull itself out of a slump by getting sexy on the racetrack.

But we’re not here for Shakespeare, right? This is an amusement park ride for kids of all ages who feel the need for speed. If that’s your thing, you’ll be fine. Director James Mangold hasn't mangled it. And, to be honest, I probably would have loved it when I was 14 and went through a brief Car Phase, thumbtacking pictures of Pontiacs to my bedroom wall all because of NBC's Knight Rider. (Ah, the power of product placement!)

But while I'm being honest, I have to admit that, as much as I enjoy Damon and Bale — I'd be hard-pressed to think of a movie I haven't enjoyed them in —·the faster this movie moved, the less I cared about keeping up with it.

The film follows two high-fiving white guys of the early '60s: a haunted ex-racer Carroll Shelby (Matt Damon), driven to get back to hashtag-winning; and the flamboyantly cocky (and cockney?) uber-driver Ken Miles (Christian Bale), who looks like just the kind of Brit that Ford needs to make American cars great again. But this is about more than just business: Ford needs this bromance to help them settle a manly rivalry — or, rather, a Le Mans-ly rivalry — with Ferrari, a grudge match that boils down to insults about weight and insults about Daddy.

And they'll do it, of course. They'll build a fast car. They'll hide a winning card up their sleeve. They'll survive explosive crashes. They'll sweat bullets taking risks beyond all reason. And they'll arrive at a strangely familiar moment in which someone's heart grows a little.

And they'll make sure that moviegoers overlook the irony here: this is a flashy corporate product exploiting the audience's eagerness to flip off the Man. The filmmakers focus on Shelby and Miles, each of them singing "I did it my wayyyy" as they fashion a car that will leave the reigning world champs behind. (The movie writes off the Ferrari folks as villains for being... what? Successful and foreign?) And so we get what we came for: loud and rickety races, lots of close-ups of speedometers, men in suits clenching their jaws, Matt Damon chewing gum like a grad from the Brad Pitt Acting Academy, lots and lots of revving noises, and, of course, one furrowed female brow (Caitriona Balfe, her name so much more interesting than her character) hovering over a cute little chip off of Miles's block.

Ford v Ferrari serves up little more than what the trailer promises. Pixar's Cars, a film without humans, had more more moments of meaningful humanity than this. It's hard not to imagine what the film could have been if the movie had had a brave driver at the wheel, one that could effectively buck a system that's more concerned about a box-office photo finish than art.

At its best, it fills the screen with streaming colors and textures, the speakers scream with audio adrenaline, and you can feel the strain as Miles bends the laws of physics to the breaking point. At its worst, its central partnership seems designed to defend the honor of insecure white men who think the big screen belongs to them, a country of smart-ass punchlines and punches thrown.

Sure, it's a "true story," but everything is so streamlined and shiny for a mass audience that I don’t believe a minute of it.

And, now that I'm looking around, I'm finding that distrust to be well-founded. Let's just start with Shelby, for example, about whom the movie has zero curiosity — a fact that makes me curious. Richard Brody at The New Yorker turns in some A+ homework here:

[Shelby's] seen briefly, early on, living alone in a messy trailer, and then isn’t seen at home again, nor is he seen to have any family life or romantic relationships. The elision of Shelby’s private life is a sleight of hand that obscures, above all, the complexity of life—it suggests a sheer unwillingness to contend with facts that don’t easily fit into a sentimental schema. The real Shelby was married seven times, and two or three of those marriages overlapped with the eight-year span covered in “Ford v Ferrari,” and extramarital affairs appear to have been involved, too.

Now that might have made the movie more interesting. But in the story spun by a trio of screenwriters — Jez Butterworth, John-Henry Butterworth, and Jason Keller (who wrote Machine Gun Preacher), Shelby does nothing more than obsess about racing.

Audiences would, of course, prefer to see the clean-cut hero smugly brushing his nay-sayers aside. But why base this on a true story at all if you're just going to whitewash the complexities of these men in favor of propping up tired American-made delusions? Why not give us more complicated human beings and a story that acknowledges the dark side of obsessions like these?

Don't get me wrong — a trip through this subtle-as-a-Hummer formula isn't without its pleasures. The great Tracy Letts me enjoy a few scenes. He's becoming one of my favorite character actors, and I found myself wishing he'd sneak up and steal the movie from the leads, like he did for me in Lady Bird. Hamming it up as Henry Ford the Second-Rate, he seems to think he's in a comedy. He's what kept me from unbuckling my seatbelt and hopping out of this not-particularly-moving car. In fact, at times, with Damon, Bale, and others playing every note at ‘11,’ it’s easy to imagine how much fun this might have been as a parody. (No disrespect, Ricky Bobby.)

As a drama, though... well, at times I catch a hint of Michael Mann's influence in this air — he's listed as a producer here — just enough to make me imagine a tougher-minded, truthful examination of the automobile as a vehicle (ahem) for the human ego and ambition, something more humbling and human. But overall, I'm left breathing the fumes of capitalism, nationalism, and, yes, toxic masculinity.

P.S. Is it just me, or does Matt Damon's resemblance to Jesse Plemmons increase the older he gets? How is that possible, since Plemmons is so much younger than him?

Light From Light: A Looking Closer Film Forum

Ever since I first saw Something, Anything, I've been eager to see what filmmaker Paul Harrill will do next.

Now I have an answer: Light from Light, a softspoken, large-hearted, ambitious ghost story starring Marin Ireland and Jim Gaffigan.

I'm working on a review of Light from Light, which I've seen twice and enjoying it more with each visit. But as Autumn Quarter is giving me more than eighty essays and assignments per week to carefully read, respond to, and grade, my writing has been slowed to a near standstill. So, rather than miss the opportunity to share my enthusiasm about this film, I'll point you to some other thought-provoking, substantial writing about Harrill's latest.

I'd love to share the Variety review with you, but they drop major spoilers, in my opinion. So wait and look that one up some other time.

Alissa Wilkinson praises the film as "an extraordinary and thought-provoking film for skeptics and believers alike." She interviewed Harrill, Gaffigan, and Ireland for Vox.

At The National Catholic Register and Decent Films, Steven Greydanus raves, "I’m tempted to call Light from Light the first ghost story I’ve ever seen that I completely believe."

He explains, "There’s no whiff of horror tropes or supernatural fantasy, that is, to beg our suspension of disbelief. Characters and events are as persuasively true to life as the best of (say) filmmakers Kenneth Lonergan or Richard Linklater."

And then he digs into the substance of what the film is so powerfully inviting us to contemplate: "Fear of loss can move us to guard our hearts — or to seize the moment, to risk for the sake of living and loving."

You can also read Greydanus's substantial interview with Harrill at The National Catholic Register.

At Cinemawayward, Joel Mayward writes,

Harrill’s beautifully haunting ghost story is interested in exploring the big ideas of metaphysics and human existence within the context of intimate, unassuming character studies. Its ethos is more spiritual than religious, more about wondering about the possibility of the impossible than offering any firm propositional truths. Any revelation is only partial, but even a partial disclosure of transcendence is enough to elicit a frisson of awe.

Is the film's contemplative tone too quiet? Vikram Murthi at The AV Club writes

While the contemplative tone and measured pacing are definitely features instead of bugs, Light Of Light is so anodyne at times that it borders on inert. Harrill is poignantly, sensitively attuned to the emotional states of his characters. Yet it often feels like that’s the only thing being offered in Light From Light, which hits the same note repeatedly—a problem, even when the note is haunting and it’s being struck for just 82 minutes.

But Jordan Raup at The Filmstage doesn't appear to be troubled:

If the jump scares and horror set pieces of Paranormal Activity or The Conjuring franchises were exchanged for an authentic reckoning of the tangled emotions the departed may leave behind, you have something close to Light From Light. There’s a palpable tension to this story of paranormal investigating, but rather than injecting the expected terror, the film’s power lies in never seeing ghost hunting depicted so grounded and character-driven before.

...

Light From Light‘s strength is focusing on the details of life laid bare, both what we see captured through the director’s keen eye and the experiences awaiting those that are willing to partake in. In the span of only around 80 minutes, Harrill builds a space for his actors to fully inhabit their characters, leading to a blissfully satisfying, profoundly spiritual conclusion.

Cinemarginalia: Justin Chang & Ins Choi at The Glen Workshop; Criterion sale; Scorsese in Seattle

Justin Chang, Ins Choi, Daniel Garcia, Liz Vice, Over the Rhine, and more next summer at The Glen Workshop

Whether you're looking for a chance to network with filmmakers, film critics, television writers, or artists in any other discipline, I cannot recommend The Glen Workshop highly enough.

Yes, it's that time of year where I volunteer — nobody pays me to say these things — to sing the praises of this 8-day summertime arts retreat — the last Sunday in July through the first Sunday in August — in Santa Fe, New Mexico.

Why? The Glen Workshop has changed my life in so many ways that I cannot measure the expanse of their influence. For sixteen summers running, Anne and I have enjoyed the most memorable and important weeks of our lives together in Santa Fe, surrounded by a community of inspired and inspiring artists and art-lovers who have become a meaningful family to us across North America and beyond.

Image has just announced the lineup of special guests who will be leading workshops in August 2020, and it's an outstanding array of imaginations and talents.

Los Angeles Times film critic Justin Chang — an exemplar of professionalism, clarity, and insight, and one of the very best in the business — will teach film criticism. Ins Choi, the imagination behind Kim's Convenience, a writer whose comedy comes from wisdom, will be there teaching writing for television. Award-winning filmmaker Daniel Garcia, who I interviewed onstage at the Glen last August, will be back teaching Mobile Phone Moviemakking. I've enjoyed their company and conversations at tables in L.A. and Seattle and Santa Fe, and I'm jealous of any of you who sign up for their workshops.

Over the Rhine will be back — not teaching the songwriting workshop this time, but as writers-in-residence, enjoying this community that has inspired so much of their music over the last fifteen years. Liz Vice, another glorious voice, will lead us in song during worship hours. Author Brian Volck, who is as much a mentor as a friend to me, will lead a seminar on "Science, Poetry, and the Imagination."

And I'm just scratching the surface of the list of names and opportunities awaiting you at this, the most rewarding arts retreat I've ever enjoyed. Every year I encourage my friends to sign up and discover it. One by one, they've been showing up. One by one, they've been saying, "Why didn't I do this earlier? Yes, it's an investment... but the reward is so much greater than the cost." Literature, music, cinema, friendship, Santa Fe cuisine, Santa Fe art museums, the glory of high-plains New Mexico weather in August... and so much more.

Sign up... before it fills up!

The Criterion Collection: 50% off at Barnes & Noble

Caution: Barnes and Noble's 50% Off Criterion Collection sale is on.

It's either a chance to increase the quantity and quality of your home video library, or it's a chance to demonstrate a Herculean feat of restraint and self-control.

I'm picking up the new blu-ray of Do the Right Thing. But what I'm really waiting for is the release of Wim Wenders' Until the End of the World, the entirety of which has never been released on home video in America. Hopefully, it will be included in the sale before time runs out.

Scorsese at the Cinerama

I Heard That You Paint Houses is going to open on the biggest, most beautiful screen in Seattle: the Cinerama.

What, you think I've got the title wrong?

In case you missed it...

I've seen Joker and I'm working on a review. I was impressed by some aspects of it, but I also watched this Saturday Night Live parody and found myself nodding and saying, "Yeah, you know — it's just too easy to tell this story in a way that announces its own Importance."

https://youtu.be/kqpak5lFxvs

Overstreet Radio: Wilco, Lucy Dacus, Innocence Mission, R.E.M., Bruce Cockburn, and more

Looking to finish out 2019 with some extraordinary music?

Here are some highlights from what I've been listening to during the last couple of weeks, mostly in the car during my long, crowded 45-minute commute to and from teaching at Seattle Pacific University. (I drive in at about 9:30 AM, and I drive home at about 10 PM. Yeah... long days.)

Three Heavy Hitters: Elbow, Nick Cave & the Bad Seeds, Wilco

On my list of bands that make me drop everything and tune in to new music every time, you'll find the names Elbow, Wilco, and Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds.

All three have released new albums in recent weeks.

Elbow's Giants of All Sizes may not be the landmark for me that The Takeoff and Landing of Everything was, but it's an outstanding rock and roll record that satisfies in a way that reminds me of the days when new U2 records shook the earth. Here are three tracks: "Dexter and Sinister," "Empires," and "My Trouble."

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-CR628yT7aE

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EJa5FvCaBJc

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BD_ZgAEjLNg

Here's a track from Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds. Their new album Ghosteen finds Cave bearing up under an incomprehensible burden of grief in the years following the tragic death of his 15-year-old son. He'd already responded to that loss with the harrowing record The Skeleton Tree, but Ghosteen quickly rises to stand among his finest records over many years of a bold and visceral music.

Here's the full album. Caution: This is both visionary and heartbreaking. It's not background music.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GwlU_wsT20Q

Wilco's new record Ode to Joy did not really capture my attention at first listen — but that's because I played it while I was grading papers. Today, playing it in the car at high volume, I discovered layers of sound I hadn't noticed before, and the experience was full of surprises. I'm going to spend a lot more time with this one now that I now how complicated it is.

Here's a track from Ode to Joy:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VamTQr4kcKA

Scary stuff from Lucy Dacus

A few days before Halloween, Lucy Dacus — whose 2017 album Historian is impressing me more and more over time — delivered the latest in her series of holiday-focused cover songs. And I was both surprised by her choice and enthusiastic. I've been blasting this in the car repeatedly.

https://youtu.be/edyOX8eMNig

Mission accomplished... again!

In other news, The Innocence Mission already have another album for us! Last year's Sun on the Square was so good that I invested in the green vinyl edition, so I can't wait to hear See You Tomorrow, which is set for release in 2020.

Here's the first song they've released.

https://youtu.be/jp-rNF6zVhU

Monstrous remix!

Scott Litt has remixed the entirey of R.E.M.'s 2004 album Monster, and you'll get that and a remastered version of the original mix... and hours and hours of bonus material... on the new 25th anniversary Deluxe Edition release.

I listened to the new mix of the album this morning, and began tweeting like a crazy person.

First:

I always liked R.E.M.'s MONSTER better than most fans of the band that I knew. But this new remix included on the deluxe 25th anniversary edition is out of this world. Streamlined "Kenneth" uncrowds the sound = an improvement. New "Crush with Eyeliner" is brilliant. Etc.

Then:

...I'm not sure what in the world they've done with "King of Comedy," but I think my headphones are on fire. The drums are all over the place. I hear crazy backup vocals I've never noticed before. This is like getting a whole new album from a band I've been missing since REVEAL.

And then:

... In "Star 69," "Strange Currencies," and "Tongue," Stipe emerges from what was a muddy original mix and sounds like a lead singer in a spotlight, his lyrics clear at last. And these alternate lead vocal tracks are full of surprises. ...

https://youtu.be/NYZkxwuxmLg

Instrumental highlights

As my time these days is overwhelmed by the number of essays and assignments I'm grading, I'm listening to a lot of instrumental music. Fortunately for me, there have been a lot of excellent new releases that seem custom-made to inspire both energy and peace.

I'm particularly enjoying two new releases —

Nils Frahm's All Encores, which features this zippy number called "All Armed":

https://youtu.be/7wfkc8kD7Fo

... and Bruce Cockburn's outstanding new album of guitar instrumentals called Crowing Ignites, which features "Bells of Gethsemane":

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=A_nE5en5DGQ

Practicing the Prophetic: James K. A. Smith on liturgy and discernment

James K. A. Smith, the new editor of Image and the author of You Are What You Love and Imagining the Kingdom, was the special guest at Seattle Pacific University's Day of Common Learning in October, delivering a plenary address on "Liturgy, Formation, and Discernment for Public Life."

And now, you have a seat near the front.

https://youtu.be/NRFgUU9DIh4

I had the privilege of following up Smith's lecture with a presentation of my own, one based in part on my new Image essay: "In the Cosmos of the Arts, a Christian Cosmonaut is Born Again."

Alas, I don't have video of that one, but you can see a recent lecture that served as a sort of rough draft of it here, from last spring's Brehm Cascadia conference called "Sacrament and Story."

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OOTg8ReiWMo

Famine Walk - the new Joe Henry opening track is here

Joe Henry's new song "Famine Walk" is out and it deserves a post all its own.

I heard it in the car today, and I had to pull the car over.

Soon after, I pre-ordered the vinyl of The Gospel According to Water.

Read all about it here.