Not so fast, but oh so furious: Thelma is a blast.

I've just spent another weekend at the home I grew up in, assisting my mother with all kinds of things, as she now begins the next season of her life mostly alone in that house, my father having passed on after their 57 years together.

A heavy shadow of grief lies over this Northeast Portland property where my parents have lived since I was four years old. Those clouds occasionally part to remind us that my father's severe sufferings — the hearing loss, the loss of speech and language, the loss of memories, the increasing confusion and distress — are finally over. Still, that awareness of a void, an absence, an unresolvable problem, is there waiting for us at every turn.

Quotidian tasks still need to be done. Their printer is not working, and the processes of choosing a new one, uninstalling old programs, and installing new ones, must be carried out in a language of today's technology that my mother does not speak. Firewood must be stacked. Outdoor faucets must be covered to protect them from the freeze. Documents must be scanned and emailed to the funeral home. And on and on.

We need each other. We need to be there for one another. We need to consider the daunting challenges of those who depend on younger and more physically agile people in order to accomplish what must be accomplished. We need to give our love and attention (are those not the same thing?) to those whose world is fading into the past, whose physical capacities are diminishing, whose intellects are not equipped to keep up with the rapidly changing demands of being connected to basic human services, pleasures, and necessities.

In the last few weeks, I have met husbands, wives, fathers, mothers, grandfathers, and grandmothers who are now relying on healthcare workers in hospitals and foster care homes. I have met nurses, doctors, and foster care hosts. I have seen sufferings that have been devastating to behold, even though I know that they are common; there is something about being there, in person, and paying up-close attention, that will shake you and restore your perspective to What Is Really Going On Here in this fragile world. There is something about showing up, holding those cold and feeble hands, and watching the courage and the diligence and the professionalism of good healthcare workers that will humble you and show you who the Real Heroes of the world are. As Karin Bergquist of Over the Rhine often reminds the band's audiences — we give standing ovations to the wrong people in our world. Many (if not most) of the world's greatest heroes are doing hard and often thankless work behind closed doors.

Going through this, I find that I have been given new lenses to see things more clearly. And now even the most incidental recent experiences seem different to me.

For example, Thelma.

Here's a film that pays loving, good-humored attention to characters who are usually ignored. It celebrates them. It shows us how manic, how irresponsible, how foolish we can be when we lose touch with our elders and those who need our help. It shows us how they, attending to urgent life-and-death needs, are often seeing things more clearly than we are. And yet, it is not a grim or dire film. It is a joy.

I recommend that you and your family visit Thelma this Christmas.

An early draft of this review was originally published on June 24, 2024,

at Give Me Some Light on Substack, months before it appeared here.

Subscribe, and you'll read many of these reviews while the films are still breaking news!

Very few of us have had family members kidnapped, but look at how many moviegoers rush to theaters year after year to watch the latest action thriller about a father hunting down the crooks who took his daughter!

Now… raise your hands: How many of you have been frustrated by scam artists trying to trick you into giving them money? Okay — that’s a lot of hands! Wouldn’t you like to see a movie about somebody who’s mad as hell, who can’t take it anymore, and is ready to hunt down a predatory caller? I have good news for you. There’s a movie in theaters right now, scheduled for prime summer showtimes, that you’re going to love.

I don’t think I’ll stir up any controversy if I claim that youth, big-name celebrities, and action rule at the summertime box office. Having said that, I can hardly believe what I get to recommend — with confidence! — as a sure thing for big-screen entertainment here in the fourth week of June.

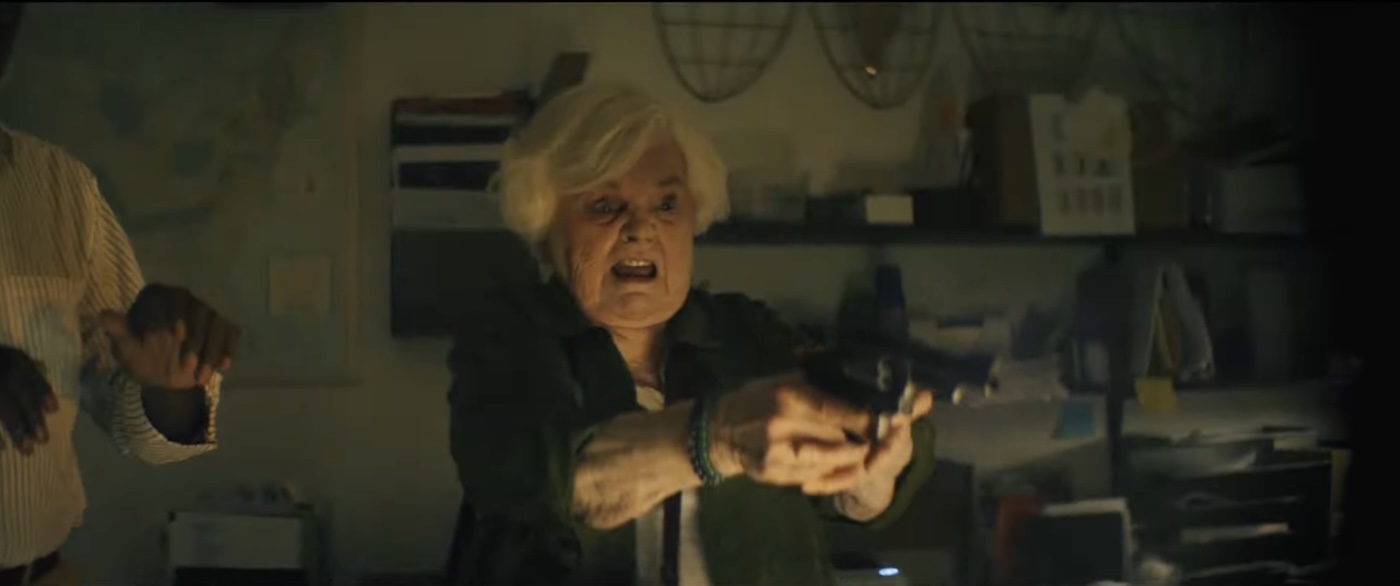

Thelma, the first feature written and directed by Josh Margolin, stars 94-year-old June Squibb as a widow who gets scammed online and decides to hunt down the criminal trickster. Okay — she’s not exactly Tom Cruise, and this isn’t anything like Bad Boys 2. But trust me, it’s a joy. If enough people go see this, word of mouth will spread fast, and it just might end up the sleeper hit of the summer.

You’ll notice that I used the “E” word in those opening paragraphs. I’m more inclined to movies that inspire the “A” word — art — than I am to rave about entertainment. And yes, sure, both words are fairly flexible. I tend to think of art films as films that are about much more than the surface-level narrative suggests; thus, they require close observation to both style and substance, asking us to do some measure of interpretation. Art films tend to reward multiple viewings with new discoveries, and they inspire challenging discussions. If I lean on the term entertainment, I’m probably thinking of a film that is more focused on satisfying the audience once, with easy pleasures that signal we can, to some degree, “turn off our brains” and relax. They’re fun as they play, but we’re probably not still reflecting on and interpreting them a week later.

Thelma strikes me as above-average entertainment — a good time for just about anybody who buys a ticket. The characters are endearing, the cast is a pleasure to watch, the jokes are strong, and the narrative arc has enough surprises and delights to send everybody home happy.

But there is an art to executing formulaic entertainment. And Thelma is artfully made. The formula is familiar: Someone has been harmed, and so they vow to carry out some vigilante justice. This leads to a quest, the help of a sidekick, episodic adventures that involve risk and cunning, and eventually a climactic confrontation with a villain.

But there are unique variations on that formula here. Thelma is not a typical action hero. She is bound by almost all of the limitations that anybody in their 90s would typically be.

Thelma is played by June Squibb, who turned 93 as Margolin was making this movie, and while she found her way to stardom late in life, she’s racked up quite an impressive record of screen credits, and she’s showing off her big movie-star charisma here. Squibb makes us believe, she makes us care, and she makes us laugh — a lot. I wouldn’t be surprise if this wins her a second Oscar nomination next winter. (Stick around for the closing credits to spend a few moments with the real-life Thelma who was the inspiration for Squibb’s character.)

While Thelma and her grandson watch a recent Mission: Impossible movie in Thelma’s opening minutes and comment on Tom Cruise’s remarkable athleticism considering his age, a feat of action-hero strength for Thelma might just be riding a scooter a few miles, or navigating a crowded antique shop where it’s easy to knock something over. And while Ethan Hunt’s latest adventure involves outwitting extremely sophisticated A.I. technology, Thelma, grieving the loss of her husband but enjoying her first experience of living alone, is taking her first steps in trying to catch up with a world of technology has left her far, far behind.

Almost all of us have a family member or two who, like Thelma, need our help in carrying out the most basic functions at a computer. (I recently introduced a close relative to the concept of attaching a file to an email, and pretty much blew their mind.) But I’ll bet the challenge has never seemed exciting — for them, or for us. And yet, all of this unfolds onscreen with playful Mission: Impossible conventions, including a musical score by Nick Chuba that riffs on that action franchise’s familiar motif.

Another clever reference to a legendary action franchise comes in the casting of the late Richard Roundtree — the original Shaft. Roundtree, in his final big-screen role (he died in October last year), is the perfect partner for Squibb, and their chemistry is substantial. Roundtree plays Ben, a retirement-center resident who has a lot of history with Thelma and who is quickly, if unintentionally, recruited to be her sidekick in this cross-town venture to regain Thelma’s stolen funds and teach the offender a lesson.

The movie finds another layer of comedy, tension, and thoughtfulness in the parallel action of Thelma’s family as they search for her.

Thelma’s grandson Danny (played by Fred Hechinger) is so devoted to his grandmother that she might be his best friend, and as the adventure unfolds we come to understand why: Danny is struggling to figure himself out, to learn how he can be useful to the world in view of his formidable insecurities. He knows his grandmother loves him unconditionally and believes in his capacity to get unstuck and find his way in the world.

Danny’s parents are played by Parker Posey and Clark Gregg, and while they may not have much chemistry together, they both contribute significant manic energy to the crisis of Thelma’s “disappearance” to make the situation progressively worse — and funnier.

As I found all of this more entertaining than thought-provoking, I have to admit that Anne and I had a meaningful conversation as we walked through a park after the movie. It isn’t often that movies challenge us to think about and share our expectations about aging, what we suspect we need to learn and prepare for, and what kinds of decisions we might make if we’re ever faced with the challenges that face Thelma and Ben in these scenarios. (I think we’re probably too sharp to be scammed, but how much longer will be we fit enough to navigate long stairways?)

So, here’s hoping that Thelma inspires more movies about geriatric heroes! The daunting complications that the elderly face can be as frightful as those facing any action hero, and the strengths that such struggles can reveal in them can make them inspiring role models. The more attention that creative filmmakers give the later seasons of our lives, the more we’re likely to think about them, talk about them, and be ready for them. What’s more, we might be inspired to show more love and respect to our elders who are probably laughing at this movie’s jokes with a deep and bittersweet recognition.

Here’s what I wrote on Letterboxd as soon as I got home from this good time at the movies:

Top Ten Flash Reviews I Considered Posting While the Credits Rolled

10.

A great movie for the revealing post-movie conversations you will have with whomever you see it with.

9.

It's just a hunch, but I'm calling it: The guy who plays Dumbass Michael is going to be a huge movie star someday, and we'll point back to this the way we point back to Harrison Ford in Apocalypse Now and say, "Wow. Look at that guy. Who could have imagined what he would become."

8.

Parker Posey's record is still perfect.

7.

R.I.P., Richard "Shaft" Roundtree. You made a noble choice for your last film!

6.

There's no such thing as a perfect movie, but for a straight-down-the-middle crowd-pleaser of a comedy, this knows exactly what it wants to be, achieves that, and does so with an extra measure of grace and more moments of visual cleverness than I expected.

5.

Thumbs down to the 60-something dude in front of me who sulked on the way out: "Wayyy too sleepy for me. They had the wrong editor. It needed to move much faster." My dude, could you possibly be farther from getting this movie? Who hurt you, man?

4.

Starey Garey = best non-speaking role in years.

3.

See it for the added layer of unintentional comedy coming from some of the elderly audience members who think they're in their living rooms and carry on loud conversations up and down the row, and shake their popcorn barrels loudly to see if anything's left, and very clearly relate to everything Thelma's struggling with and thus find every joke about aging twice as funny as you do. (And you know full well you'll laugh harder at this movie as you get older, too.)

2.

Along the same lines: Biggest laugh of the movie for me came after about three minutes of Thelma obviously being scammed over the phone — the scene that kick-starts the plot, and the premise that has been clear in every blurb and every trailer — and at the end of that scene, the woman in front of me loudly gasps and announced to the theater: "That was a scam!!"

1.

”I think I know her!”

Ghostlight celebrates the healing power of community theater

An early draft of this review was originally published on June 22, 2024,

at Give Me Some Light on Substack, months before it appeared here.

Subscribe, and you'll read many of these reviews while the films are still breaking news!

My high school English teacher raised eyebrows during my senior year when he started inviting students to his apartment in the evenings.

Today, I can imagine that such behavior might be concerning in view of how frequently we read headlines about abusive teachers. But in this case, the teacher’s intentions could not have been more honorable: He saw in some of us a curiosity about art that our fleeting classroom sessions could not sufficiently address, and he opened his home, which was designed with the austerity and grace of an elegant art gallery for fine photography, so that groups of us could sit comfortably in a circle, take on roles in famous plays, and read them aloud together in their entirety. Somewhere between five and a dozen students showed up each time, and we kept on meeting during the summer after my class graduated. It was an exciting way to discover that we could preserve what we loved most about our school experience even as we moved on toward new experiences.

I distinctly remember sessions where we were moved by King Lear and Death of a Salesman. We also watched Akira Kurosawa’s Ran together (in order to discover how a text like King Lear might be inventively re-interpreted in a new context). That’s where I first saw films like Jean de Florette and Manon of the Spring, as well as what would be become my all-time favorite film: Wings of Desire. I even remember watching U2: Rattle and Hum with this group and discussing the difference between powerful art and purposeful art.

The fact that Dead Poets Society opened in theaters that very summer to widespread critical acclaim and popularity seemed like a profound endorsement of our own not-so-secret club.

Those gatherings were among the most formative experiences of my life. They demonstrated for me what was possible if a person prioritized engagement with art in community. They showed me a way of living I hadn’t seen before. And the discoveries I made there, the epiphanies I experienced, made me fall in love with learning and growing through the cultivation of an empathetic imagination. What’s more, some of my most lasting and rewarding friendships took root there are flourishing still today. And I’ve tried to offer the same gift to friends and students ever since. I will always be grateful to that teacher for bearing up under the suspicions and rumors of fearful and presumptuous parents in order to show us paths into more enlightening and rewarding ways of living life and practicing faith.

This kind of experience is all too rare in our culture, and as a result too many people are content to target arts programs as frivolous (or dangerous) when cuts need to be made. (Just this week, Governor Ron DeSantis of Florida vetoed all grants for arts programs in Florida — plunging a knife into one of that state’s vital organs.) And yet, rare as that experience is, it’s common enough — and important enough — that we occasionally see a movie set on inspiring others to seek it out.

This year, one of those movies is Ghostlight.

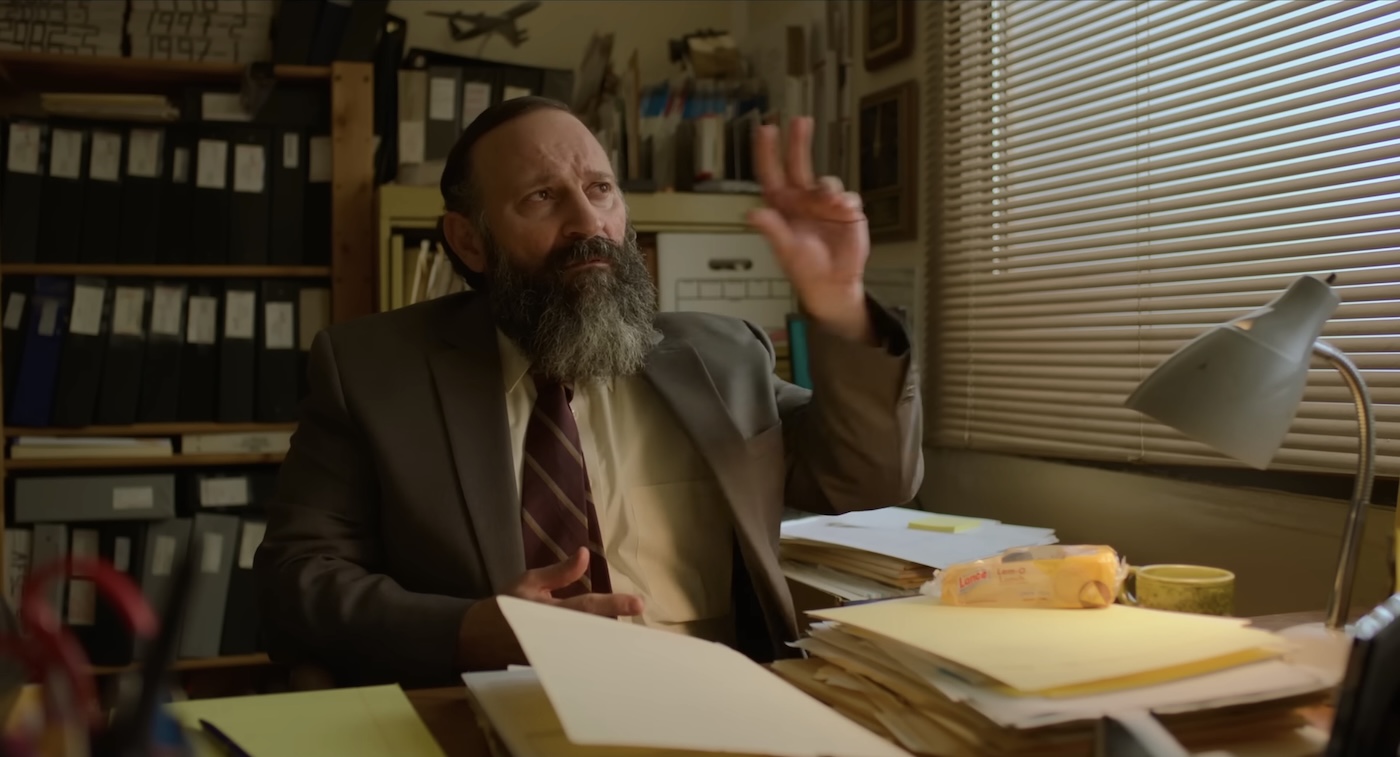

In Ghostlight, a grizzled and grouchy Dan (Keith Kupferer) — a husband, a father, a construction worker — reaches the limits of his patience in all three roles that he plays. Pressures at work are high and constant. Money is tight. And, most painful of all, he, his wife Sharon (Tara Mallen, the real-life spouse of Kupferer), and his self-destructively brash daughter Daisy (Katherine Mallen Kupferer, who is, yes, Keith and Tara’s actual daughter) are grieving a family tragedy. All it might take is for a driver to honk at Dan in the wrong moment, and he’ll explode in a way that his whole family will regret.

And if Dan explodes, somebody could get hurt. He’s a grizzled, broad-shouldered, James-Gandolfini type; I wouldn’t want him grabbing me by the lapels, slamming me against a wall, and roaring in my face.

What can save Dan from the repressed grief and rage that’s consuming him? Taking on a fourth role.

That is to say, a theatrical role.

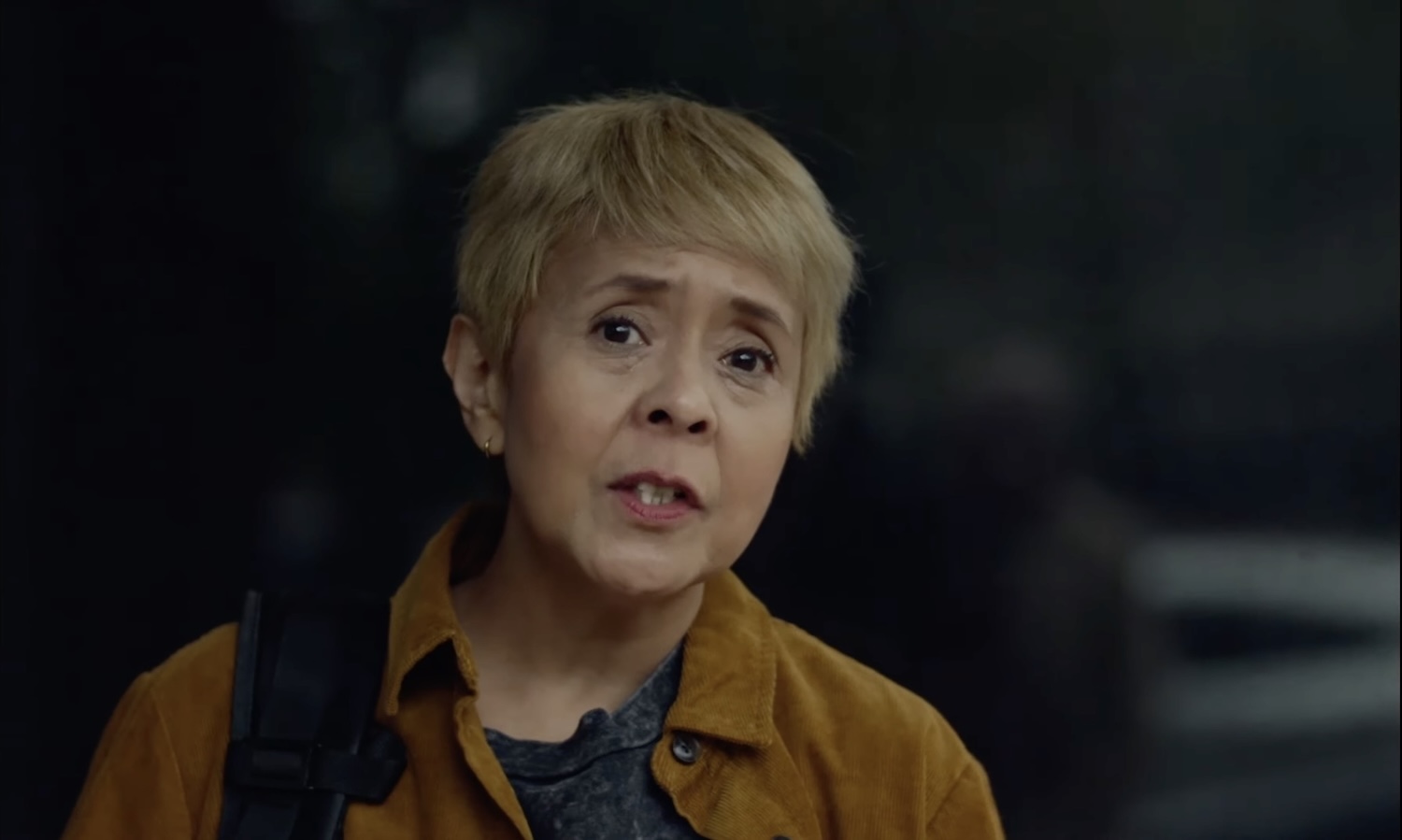

When a stranger — Rita (Dolly De Leon, who you’ll remember if you saw Triangle of Sadness) — notices Dan on the edge of self-destruction and invites him into a community theater to participate in a table reading of Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet, a small star appears in Dan’s dark sky, a light with a strange allure.

While Dan keeps stumbling back to that small and diverse group of wounded but creative people, even though he doesn’t seem to understand what’s drawing him there, he begins slowly surrendering his inhibitions and discovering relief from his debilitating stresses through the experience of losing himself in the creative process.

And as he begins to play different roles in the company of those uninhibited and enthusiastic actors, his capacity for considering what the world might look like to others, others for whom he has shown little no patience or compassion in the past, begins to change. When he begins to see that he might be complicit in the causes of his troubles, and when he begins to loosen his grip on his pent-up emotions and let some of that pressure burn off in performance, he might finally begin to grieve.

Ghostlight, written by Kelly O’Sullivan (whose 2019 debut, Saint Frances, impressed me) and directed by O’Sullivan and Alex Thompson (her partner), might be listed in a category with Dead Poets Society and Drive My Car, both films in which people’s hearts and minds expand through engagement with great works of art. It might be mentioned alongside the classic Jesus of Montreal, in which actors participating in a Passion Play are increasingly and mysteriously influenced by the roles they’re playing in the pageant, including the actor playing Jesus, whose decisions lead him into more and more dangerous and controversial behavior.

Unfortunately, I don't think I've ever spent so much time as a movie played thinking about all the notes I would have made on the screenplay. Surely someone along the way thought to challenge O’Sullivan on just how contrived things seem when we learn exactly why the text of Romeo and Juliet is affecting Dan so deeply. It’s easy to guess that his participation in the play will help him work through the trauma of his family’s devastating loss. But the connections between the real-life tragedy and the Shakespearean drama are just too much; the revelation punctured my suspension of disbelief and almost spoiled the movie for me.

What kept me watching and caring, and what eventually moved me to tears, was the revelatory performance Keith Kupferer. I recognize him from a few films going back many years, but I never knew he had this kind of talent. (Apparently, Chicago theatergoers have known the Kupferer family and their strengths for quite a while. I’m very curious about what I’ve missed.)

Despite the film’s weaknesses, I hope that moviegoers will see it and spread the word about its inspirational power. Arts programs are struggling in schools across the country. The Christian university where I teach recently cut their theater program, which has had a huge influence on Seattle’s beloved Taproot Theatre, down to just one full-time professor, and what was once an English Department faculty of more than a dozen full-time English professors has been cut down to five.

If there is any hope for amending the polarization, hatred, and violence poisoning American culture today, the arts will be essential to showing us the way. I’d argue that if Christians are concerned about loving their neighbors and encouraging compassion and empathy, they should be expanding arts programs, not cutting them.

The imagination is the territory in which hearts and minds are most powerfully transformed. If anything has kept my faith and hope alive in my lifetime, it has been the arts. Theater, cinema, literature, music — these have been the arenas in which we step outside of the contentious dynamics of argument and culture wars and dared to imagine what the experiences of our neighbors might be like. Without these exercises in imagination and empathy, I don’t know how I would have learned to follow Christ’s prevailing instruction: Love your neighbor.

Although Ghostlight makes no explicit references to religion, I would daresay that it gives us one of this year’s most dramatic and emotionally engaging portrayals of what the hard work of humility, grace, and forgiveness looks like. And it will stir emotions in audience just as powerfully as any of those films I just mentioned.

I’d also argue that the ensemble cast is just as engaging as the one in Dead Poet’s Society, particularly the real-world family playing the family at the center. I really hope Keith Kupferer’s performance will be remembered and honored with an Oscar nomination so that the movie gets a much bigger push and much larger audiences.

Speaking of Oscars, I thought about CODA a lot while watching this. That was another crowd-pleasing, family-focused film about the call of the arts changing the course of a young person’s life. And I wonder if Ghostlight has a chance of picking up steam like that film did and becoming a dark-horse Best Picture nominee. If Ghostlight were filmed with greater visual imagination, stronger cinematography, and a more subtle and creative approach to entangling Dan’s tragedy with the text of Romeo and Juliet, I'd probably find a place for it in my 2024 top five list. As it is, I’ll go on recommending the film for its meaningful observations about the power of art, and for Keith Kupferer’s indelible performance — one of the best I’ve seen from an American actor in recent years.

Take note that Ghostlight is in theaters right now, just a few weeks before Sing Sing opens, a movie about Shakespeare plays transforming the lives of prisoners. What a year for movies about the power of participating in live theater! I suspect that the two films will be compared and contrasted frequently for many months to come.

Inside Out 2 gives us all some strong anti-anxiety treatment

An early draft of this review was originally published on June 20, 2024,

at Give Me Some Light on Substack, months before it appeared here.

Subscribe, and you'll read many of these reviews while the films are still breaking news!

Ever wish you could just load up your most painful memories and catapult them to the back of your mind?

One of my favorite short stories to read with creative writing students is a disturbing fantasy called “The Hurler,” by the great fiction writer Gina Ochsner, from her book People I Wanted to Be. In it, a girl builds a catapult for “hurling” everything that troubles her over a fence and into a landfill. Before long, she has a line of visitors from all over the neighborhood: People bring her all kinds of things that represent their pain — “promise rings and ticket stubs… bad birthday presents, ID bracelets, framed pictures of the formerly loved.” One even catapults a family member. And by the end of the story, we’re struggling to accept the image of a beating human heart being cut out of a person and launched into the darkness in order to free someone of their heartache. At the beginning of the story, readers are laughing at the humor and whimsy; by halfway through, the laughter becomes more challenging; and by the end a sense of horror has settled over the room.

I don’t know if screenwriters Dave Holstein and Meg LeFauve, or Kelsey Mann (credited here with LeFauve for the story), ever read Ochsner’s story. But the central premise of Inside Out 2 reminds me very much of “The Hurler.”

In this sequel to 2015’s delightful Inside Out, we rejoin Riley (Kensington Tallman) and find her mind still full of quite-literally colorful emotions.

Riley was 11 in Inside Out, and the stress she experienced as her family relocated from Minnesota to San Francisco gave Pixar Animation a chance to develop a wonderland alive with Hashtag “All the Feels.” We watched Joy (Amy Poehler), the captain of Riley’s emotional Enterprise, strive to stabilize Riley through the relocation with the help of her colleagues Anger (Lewis Black), Fear (Bill Hader), Disgust (Mindy Kaling), and Sadness (Phyllis Smith). As feelings of loss welled up, Joy had to learn the hard way that Sadness, as unpleasant as she might sometimes be, is absolutely essential to a human being’s capacity to process change. Sadness ended up playing a key role in helping Riley be truthful about her struggles, grieve her losses, and ultimately bond with her parents in their own losses, thus increasing their understanding and love, and helping them release their pain to make room for new experience.

Inside Out 2 follows a similar arc, but finds Riley suffering the first quakes of puberty. The basic crew is back at their stations — with a few vocal switch-ups (Hader is replaced by Tony Hale, Kaling by Liza Lapira). And, following Joy’s reckless whims to help Riley develop a flawless “sense of self,” they’re loading up the colorful orbs of Riley’s darkest thoughts and catapulting them to the back of her mind so she doesn’t have to reckon with them. (Hmm. Sound familiar?)But their experiment is interrupted by a wrecking and construction crew who barge in into Headquarters, smash things to pieces, go to work up upgrading Riley’s technology, and set the stage for an influx of new and disruptive emotions: Anxiety (Maya Hawke, who is having a year!), Envy (Ayo Edebiri, who is having a year!), Embarrassment (Paul Walter Hauser), Ennui (Adèle Exarchopoulos), and Nostalgia (June Squibb, who is, yes, having a year!).

This “remodel” takes place as Riley and her two best friends Grace (Grace Lu) and Bree (Sumayyah Nuriddin-Green) are readying for high school, and Riley’s emotional equilibrium suffers heavy blows when she learns that Grace and Bree are transferring to a different high school. Making things more complicated, Riley decides that she needs to impress the cool kids at her new school. All of these conflicting fears, desires, insecurities, and ambitions play out most dramatically on the ice rink at hockey camp, as Riley strives to make the high school team, deal with peer pressure, and decide whether or not to honor her old friendships at the risk of jeopardizing her reputation.

Riding a rollercoaster of these new emotions, Riley’s moral compass goes haywire. Anxiety and her gang sweep Joy and her team aside, commandeer the upgraded Headquarters, and drive Riley into a vertiginous spiral of emotional distress, which leads to some impulsive, unethical decisions. She’ll lash out in rage at one moment, implode with despair the next, swoon over pop culture heartthrobs, spew lies driven by envy of others, and even stoop to crimes like breaking and entering in order to appease her anxieties. Joy and Company have to address these crises by delving into the depths of Riley’s subconscious, even discovering a Deep Dark Secret.

As this character we care about shocks us with the severity of her behavior, I realized that the Pixar sequel Kelsey Mann’s directorial debut reminds me of most is Monsters University. That, too, was a Pixar sequel that took risks in compromising the integrity of a primary character. But while the storytelling team goes to surprising extremes in upsetting the familiar order and displacing and scattering characters we know and love, we can rightly assume that the disparate pieces will be reconciled in another of Pixar’s typically frenzied finales. And, for the most part, it works. I appreciate where the story ends up. It doesn’t merely endorse “positive thinking” — in fact, it does the opposite of that, forcing Riley to arrive at a truthful but forgiving new “sense of self.”While I don’t think Inside Out 2 is as sublime a cinematic achievement as Toy Story 2, it seems stronger to me than any of the other Pixar sequels so far. We could nitpick about the fact that emotions like envy and anxiety are present in children long before puberty, but let’s cut the storytellers some slack here: The point is obviously that these emotions frequently take on destabilizing influence in teen years, and I don’t think many are likely to argue with that generalization. In a fantasy that anthropomorphizes concepts as subjective and complicated as “fear” and “nostalgia,” we have to agree with the storytellers to treat character definitions rather loosely. (The movie itself acknowledges — and has fun with — some contradictions, allowing Anger to make some level-headed suggestions, and even Embarrassment occasionally stands up straight and tall.)

If I have any serious misgivings about the conclusion, they have to do with accountability. Over the course of Riley’s chemical calamity, we see her committing some serious infractions… infractions that we expect we’ll see reckoned with in some “teachable moments.” Strangely, almost all of those behaviors are brushed aside, forgotten, or… maybe just deleted to bring the movie in at around 90 minutes?Don’t get me wrong — I think it would be simplistic and, worse, moralistic to require the storytellers to punish Riley severely for all of her crimes. I’ve already seen a few critics filing greater grievances than mine, complaining that the movie “lets Riley off” without “holding her accountable.” And I can remember a younger, more moralistic, more judgmental version of myself that would have agreed. But I’ve grown to believe that such legalism does more harm than good — to movies, and to people. Isn’t it a nearly universal human experience that we do not all suffer harsh justice for our teenage crimes in the here and now? I suspect we’ve all committed indiscretions, major or minor, in our teen years that embarrass us and haunt us (like the Deep Dark Secret who lurks in the shadows of Riley’s memory), crimes that were never brought before a court. In healthy human beings, these unresolved issues become burdens of conscience that have a formative influence on us, and we should let storytellers reflect that reality. I’m glad the movie doesn’t tidy things up too nicely. (And anyway, we do see Riley repenting of some sins — and receiving some grace from others. This suggests that such things are possible, even if not all of them are being accounted for in the onscreen narrative.) The storytellers shouldn’t be required to audit Riley’s morality and publish her report card at the end of the film; if they show her finding her way to new and healthy balance — leaning into truthfulness, hope, and love instead of justifying misbehavior for some narrow definition of success — that’s more than enough for me.

Having said that, it does seem like an important scene or two — even just a quick glimpse of some conversations and reconciliations — might be missing at the end. I find it odd that movie focuses so much on one particularly dramatic lapse in judgment — it involves Riley breaking into a coach’s office to read confidential information — and then never brings it up again. Here’s hoping there’s a little more about that in an Extended Edition.

Anyway, just as Riley learns to give herself grace for being imperfect, so I’m happy to grant the movie some grace — because I think the wisdom it does offer us will be incredibly therapeutic for young viewers in navigating storms of change and transition. And I can tell you that it was also therapeutic — and even deeply moving — to two grownups who need to be reminded of the truths Inside Out 2 spotlights.

As we walked through Santa Fe’s Railyard District after the movie, Anne and I talked about how, growing up in Protestant churches, we were both conditioned to constantly check our egos with reminders of how inherently sinful we were. We struggled to understand how, in the languages of the churches we grew up in, we could have a healthy sense of gratitude and joy in who we were and how we were made. That such a severe auditing of our moral character was taught from pulpits and in Sunday schools gave it an extra weight, complicating the encouragement we received from parents and teachers and our capacity to take joy in our successes. When you’re taught that God is making a list and checking it twice for every possible lapse or misbehavior, you might find yourself bending under the pressure of severe authoritarianism.

How could we possibly embrace joy if were constantly aching over our sins — the very sins that Jesus so quickly and completely forgives?

Inside Out 2 never employs any traditionally “religious” vocabulary, but its fundamentals are applicable, I think, within any sphere of human experience. As a teenager in evangelical Christian culture, I could quote chapter and verse to you about my responsibility to love my neighbor. But if I’d seen Inside Out 2 during adolescence, I think I might have had a much stronger understanding of the full standard of that glorious command: “Love your neighbor as yourself.” We can’t love our neighbors well if we aren’t practicing love for ourselves. (And yes, there’s a big difference between showing yourself love and endorsing self-indulgence or dismissing accountability for your actions.) Inside Out 2 might have been useful for teenage Jeffrey in impressing upon me the importance of showing myself patience, mercy, and forgiveness over struggles that everyone suffers. It might have helped me when I stumbled to get back up with confidence and hope, and it might have equipped me better to weather the storms of envy, embarrassment, and anxiety that still afflict me — and, I believe, everyone around me — at every turn.

I am delighted to see that Inside Out is blowing up at the box office. Let’s not take our aggravations and disappointments with it and catapult them to the back of our minds; let’s face them and discuss them. But let’s also recognize that this movie is likely to do a lot of good for a lot of people — no matter how old, no matter the nature of their challenges and transitions — for many years to come.

Hit Man hits and hits... but misses when it matters most

An early draft of this review was originally published on May 24, 2024,

at Give Me Some Light on Substack, months before it appeared here.

Subscribe, and you'll read many of these reviews while the films are still breaking news!

Ever since it became clear that Greg Mottola’s Fletch wasn’t going to become the hit that it deserved to be, I’ve been bummed out that American moviegoers don’t seem interested in funny and smart franchises for grownups. I’d watch a new Fletch every year if Mottola and Jon Hamm could turn around movies as solid as that one.

Along similar lines, whenever I hear the names “Jennifer Lopez” or “George Clooney,” I fall into a funk about how great Steven Soderbergh’s Out of Sight was, how much I wish it had been the launch of a series in which the writers tries to surpass their earlier achievements, how neither Clooney nor Lopez have ever matched the supernatural heights they reached in that film.

So, if we can’t get that ideal series or my dream sequel to Out of Sight, I’ll take this — a Hit Man movie — from Linklater every three years. Why three years? I want the screenplays to be as strong as this one, and good writing takes time.

I don’t need to join the chorus of critics hailing this as the big star-making turn for Glen Powell, who has been the Next Big Star On-Deck for several years now (arguably since Richard Linklater’s Everybody Wants Some!, but at least since Top Gun: Maverick). Nor will I be the first to say that Adria Arjona (who was stunning in the Star Wars series Andor) can match him step for step, line for line here. They’re not quite Clooney and Lopez — or, when it comes to banter, even Clooney and Zeta-Jones from Intolerable Cruelty. But they’re the best old-fashioned guy-and-a-dame Hollywood pairing I’ve seen in a while.

But the real star here is Linklater, showing off his range with a confidence I haven’t seen from him in a while. This is the guy who’s given us numerous arthouse films in a variety of genres, all of them worth going back to repeatedly: Boyhood, Bernie, the Before trilogy, Waking Life, and Dazed and Confused. But it’s also the guy whose last movie was the underwhelming animated memoir Apollo 10 1/2 and something called Last Flag Flying that most people who saw it have already forgotten. He’s firing on all cylinders here with what may become his biggest crowd-pleaser since School of Rock.

I’d recommend you avoid the most recent Netflix trailer — yes, the one I've linked here in the image captions — as it spoils so many of the movie’s best moments and biggest laughs.

And, for the same reason, it’s probably best I say as little as possible about the plot. Suffice it to say that Gary Johnson (Powell) is a college philosophy professor who has a side gig helping undercover cops catch killers by wearing a wire, putting on disguises (Fletch-style), and getting bad guys to spill the deets on their murderous intentions. In our story, he targets a woman who wants her husband killed and ends up more than charmed by her. Before he knows it, he’s trying to protect her from an abusive husband, lying to the cops about his investment in her situation, and questioning his own motives as he gets deeper and deeper into ethical compromises.

It’s slick. It’s consistently funny and surprising. The supporting cast is a surprising crew, all of them excellent. (I’m especially happy to see Parks and Recreation’s Retta again, but The Walking Dead’s Austin Amelio is especially strong here in a very complicated part.) All the way through, I was braced for Linklater to stumble in his precarious balance of comedy, intrigue, and playfulness with big ethical questions.

But he did it. He pulled it off. He gave me exactly the kind of traditional Hollywood comedy for grownups that I’ve been missing, and scratched an itch I’ve had for a long, long time. After so many over-long and overly expensive franchise installments, and an Oscar season burgeoning with “important” movies, this is exactly what the doctor ordered for Summer 2024. I think word of mouth is going to be huge, and people are going to love it. Give us more, please, Linklater.

Having said that, I hate to wrap up my review with a disclaimer — but here we go:

In the very last scene of the film, I think Linklater and Powell lose their balance. In a rush of sentimentality, they lose their judgment and courage as storytellers. They give in to the wishes of those who think Love is more important than Conscience. I won’t spoil it, but I have serious issues with decisions made in that final scene. Don’t get me wrong — I love a good dark comedy. And if I thought the film had slowly prepared us for the revolting choices made in the final moments, if I thought Hit Man was a sophisticated satire about the incremental collapse of a conscience, I might find be persuaded to read this conclusion as a dark twist in a cautionary tale. I've seen some make that argument. But it sure didn't read that way to me. And what's more, if that is what Linklater's going for, he needs to make it work, because I think Hit Man is going to have audiences cheering for a decision that — like the conclusion of Out of Sight — sets off all of my Ethics 101 alarms.

I end up saying to myself, "They were this close to a perfect summer comedy. But now I have to recommend it with disclaimers for the sake of my conscience?!"

Civil War — It's not about picking a side

If you’ve been wondering when I’ll get around to reviewing Alex Garland’s controversial new thriller Civil War, well… surprise! I did review it — way back on May 3.

I felt compelled to. The more I read reviews from critics I respect, the more confused and frustrated I became with what seemed like impatient reactions and reviews by people who wanted the film to be an explicitly partisan political cartoon. The movie I saw seemed interested in particular characters — specifically, journalists — who have grown in wisdom through their careers but who still have important things (maybe the most important things) to learn. I had to put my own reading of the film into words, and those words differ substantially from just about everything else I’ve read elsewhere.

I wrote that review in answer to an invitation from an editor at Current. And I'm grateful and honored that they would think of me.

My Civil War review was published on May 3. You can check it out here.

Still recovering from an evening with Hundreds of Beavers

An early draft of this post was originally published on May 20, 2024,

at Give Me Some Light on Substack, months before it appeared here.

Subscribe, and you'll read many of these posts and reviews while the films are still breaking news!

My story begins with a movie trailer.

I had stumbled onto the promo for Hundreds of Beavers on YouTube, and it made me laugh. Then it made laugh again. I leaned forward, intrigued. Somebody had gone to a lot of work to create startling images while also adhering to strict limitations. Who would do this? Who would go to the trouble to dress up actors in goofy animal costumes—costumes that might be mascots for a high-school football tournament featuring the Rabbits, the Raccoons, the Wolves, and, of course, the Beavers—and film a live-action Looney Toons cartoon in a snowbound forest?

I might have chuckled and turned the thing off, but the rapid-fire blasts of slapstick accelerated in ambition and ingenuity. And the range of scenarios flashing past suggested that this just might be as epic as Mad Max: Fury Road. Surely nobody could sustain this kind of high-speed madness into a feature-length film!

But then, those blasts were punctuated with brief blurbs from rave reviews — reviews from credible sources!

Once in a while, a sort of sixth sense triggers a sense of caution in me: Stop reading about this movie. This might be one of those rare occasions when you get to witness something unprecedented without any surprises spoiled beforehand. This might be one of those times where the less you know, the better the experience.

I made a mental note: I had to check this out. But when would I get a chance?

While I skipped detailed reviews, I started keeping watch over local film calendars. Where and when would this mystery movie surface? Months passed, and I found very few mentions of the film—like faint traces of frantic fiddle tunes popping up between stations on a static-fuzzy radio. I wrote to my friend Melissa Tamminga, director of the excellent Pickford Cinema Center in Bellingham, Washington, and one of my favorite film critics. Lo—she, too, was tracking it. And it didn’t take long for her to send me an alert: She was bringing it to the Pickford for a couple of days, and the screenings were selling out fast. Word was spreading. I seized two tickets.

So, in March, my friend Kirk and I took a road trip from Seattle north to the Pickford. We didn’t know what to expect in terms of an audience. Would we make a bunch of new friends, other adventurers who had been similarly intrigued? We didn’t have to wait long to get our answer. Soon, we were standing in line with a crowd so animated that you’d think they were getting an advanced screening of… well, since I mentioned Fury Road, let’s say Furiosa. Or, better yet… Furry-osa?

Tamminga mingled with the enthusiastic moviegoers before the show, wishing us well. She'd already seen the movie; she knew what we were about to witness/discover/suffer. Those paying attention may have noticed that little cut-out beaver faces were grinning at them from hiding places on every movie poster in the lounge. There was a sense in the lobby that something life-altering was about to take place.

And then it did. Here’s my review…

First, you’re laughing. It’s silly.

Then, you begin to realize the staggering amount of planning, the insane amount of belief and conviction, the stamina and the belief that must have been required to accomplish this. Director Mike Cheslik and his co-writer and star Ryland Brickson Cole Tews are mad geniuses.

And then, you’re laughing again.

Then, good lord… you start wishing for a lull, a break, a breather.

But, no. It’s just getting started. This is the epic story set in a frozen Wisconsin of the 19th Century, where Jean Kayak, a well-established brewer of applejack, loses the farm in a catastrophic accident triggered by a beaver. Ruined, Kayak struggles to survive in a winter wonderland that seems cursed to taunt and torment him. What unfolds is sort of like a satirical remake of The Revenant — and I dare say that I enjoyed this film much, much more than that one. I doubt that Leonardo DiCaprio suffered half as much in his Oscar-winning turn as Tews must have suffered here to play out all of these accelerated, acrobatic antics in the snow.

The less I say about what happens from there, the better. Suffice it to say that Kayak’s adventures involve working out ways to survive the winter, carry out elaborate revenge, and eventually win the hand of a beautiful furrier (a woman with hidden talents) from her father, a hard-bargaining merchant. But I’m barely scratching the surface of this frozen wilderness full of surprises.

Hundreds of Beavers just keeps going, to greater and greater extremes of invention, denser and denser layers of recurring gags. Watching madman Cheslik's movie unfold feels like watching a high-speed juggler who continues to add increasingly unwieldy items to his act until you're mesmerized, frustrated, even a little scared... and then it goes on for hours so that you're actively wishing for him to drop something, even as you want to see just how far he can push the ambition.

You start getting tired.

But then you’re laughing again.

Eventually, you’re exhausted. The momentum is taxing, the acrobatic physical comedy belief-beggaring. You start to wonder if slapstick absurdism like this should ever be extended into a feature-length film. You wonder if you’ll make it to the end. Is that getting close? Surely it’s been almost two hours. You check your phone.

You’re only 50 minutes in. This film is an hour and forty-five minutes long.

You decide that this was a mistake.

But the row of sky-high college kids in the row in front of you are laughing like they might have permanently lost their minds. They’re spilling beer on each other, fumbling under the seats for the phones and wallets they keep dropping. They seem to think that the theater is the movie lounge in their dormitory. They’re shrieking, screaming with laughter. One of them has come out of his chair. He might be weeping. Some of them are in beaver costumes. They seem like they're an extension of the onscreen chaos. Could they be members of the crew, still working for Cheslik? I wouldn’t put it past him.

You realize that you are witnessing a landmark cinematic event: the arrival of an undeniable cult classic, a film people will dare each other to watch until 4 a.m. as a sort of self-torture… and love it. It is an all-consuming mania, a machine of unhinged fantasy that catapults you into altered states even if you never partook of the edibles.

And then you’re laughing again.

You wonder if this is the kind of movie that gives people seizures. You might, in fact, be having one.

Hours later, you’re lying awake. Your eyes are closed, but the movie is still playing in your brain. Beavers. Beavers… everywhere.

Kirk and I tried to find words to sum up our experience on the long drive home, which was just as long as the movie itself. We failed.

I might love it. I barely survived it. I’m deeply scarred by it. I don’t know if I could ever sit through it again.

But I know this: I want to have more of whatever these filmmakers have that made them capable of achieving something so singular, so sustained, so ambitious, so insane.

2024 is turning into the Year of the Anti-Blockbuster. It’s become a festival of movies made with unconventional methods, a lot of low-budget ingenuity, and an obvious passion for their risky ideas. And I can’t get enough of it. Riddle of Fire, Love Lies Bleeding, Gasoline Rainbow… these are movies that keep me on the edge of my seat with that rare joy of discover. I can tell the filmmakers love movies as much or more than I do, and that they love what they’re doing. Hundreds of Beavers is one of those movies.

I highly recommend that you give it a chance, even if you’ve missed out on your opportunities to see this with a roaring crowd. But know this: Hundreds of Beavers is a movie that must be watched uninterrupted if you’re going to appreciate it properly. Watching it with your phone in hand, or at home where other things are happening, you will not suffer it the way we all should suffer it to experience the rollercoaster of amazement, exasperation, exhaustion, and then new highs of incredulity.

It may not be your thing. But I suspect that it will impress upon you just how lazy, how routine, how unimaginative most contemporary comedies really are. Cheslik, Tews, and company approached this project as if they were competing for an Olympic event, aiming to set an unmatchable record in a sport of their own invention. I still don’t know what I think of it, but I surrender. Give them the gold.

Hundreds of Beavers is currently streaming free of charge for subscribers to Hoopla. (Check your local public library to see if they offer access.) It’s also streaming for a bargain rental price on Amazon and other streaming services.

Unworthy of Gosling or Blunt, Fall Guy's screenplay falls short of my summer movie standards

An early draft of this post was originally published on May 11, 2024,

at Give Me Some Light on Substack, months before it appeared here.

Subscribe, and you'll read many of these posts and reviews while the films are still breaking news!

Here are the Top Ten Possible Letterboxd Reviews for The Fall Guy that I drafted while waiting for the new David Leitch movie to end….

#10

Me, during Ryan Gosling's opening narration: Every word of this is unnecessary and making the movie worse.

Me, during every line the writers give him for the rest of the film: Every word of this is unnecessary and making the movie worse.

#9.

Only Donald Trump gives himself a smugly self-aggrandizing thumbs-up on camera as often as this movie gives itself one. Roger Ebert would not be amused.

#8.

I can shrug off a bad movie, but I won't forgive them for spoiling “Without a Trace” — one of the best movie-based hits of the '80s — by setting it to what I'll probably remember as the worst scene of the year. Justice for Phil Collins.

#7.

You know something's gone terribly wrong when a character references Love Actually and you spend the next 15 minutes wishing you were watching that instead.

#6.

Michael Mann's Miami Vice made me want a mojito. The Fall Guy has cursed the spicy margarita. And that was my favorite drink. That may be the real reason I'm gonna go ahead and dock this an extra half-star.

#5.

Aaron Taylor-Johnson, killing it with a mercilessly cartoonish Matthew McConaughey send-up, actually pulled me out of a very deep funk for a few minutes as we rounded what I thought was the final turn.

But then there were more turns.

So many more turns.

#4.

I think the moment the ground fell out from under me came early, when Gosling gets into an SUV, turns on the radio, hears a Taylor Swift song in progress, and cranks it up for pathos. Maximum pandering. Should've played it as a jump scare instead. (Oh well... this “hero’s” wannabe catchphrase is “Let's make bad decisions.”)

#3.

I could have walked into the theater next door and seen Challengers a second time.

Let me say that again: I could have walked into the theater next door and seen Challengers a second time!

#2.

“Here are the Top Ten Letterboxd Reviews for The Fall Guy that I drafted while waiting for this movie to end....”

#1.

Everyone and everything involved just jumped the shark.

After I published that Top Ten List on Letterboxd...

I lay awake late into the night, severely aggravated not only by the movie, but by my discovery that a lot of critics who should know better are excusing this movie’s many mediocrities and flat-out absurdities, calling it “fun” and “exactly what we need right now.” That amounts to a dereliction of duty.

So, here are several more notes I could add to the previous list:

#11.

Hannah Waddingham's magic in Ted Lasso was in her restraint. This performance is so over-the-top that I think I need to avoid things she's in now for a long, long time.

#12.

In this movie, characters describe blockbuster action movies as nothing more than medicine wrapped in "sexy bacon" — you know, like when you wrap a pill in meat to make a dog take his medicine.

Jeez.

What a demeaning perspective for any “artist” to have on their work. And we're supposed to root for these “filmmakers”? If that's all you require of our action blockbusters, well... you can have them, little doggies. I'm out. I remember summer action movies that were so much better than this.

#13.

Who cares about, or can suspend any disbelief at all for, or even bother tracking this inane narrative?

#14.

Who thinks that these "characters" are actually characters? So, a stuntman and a cinematographer had a lovey-dovey fling, and then he got injured and they didn't hook up for another year, and she resents this, and this — this — is the tragedy, the crisis at the heart of the picture? This is what we're hoping to see resolved?

#15.

Come to think of it, don't bother preaching to us about love either, when you haven't given us any evidence that love ever had anything to do with it.

#16.

If you're going to throw in an allusion to another film or show, make it count. Don't just smirk and be like "Remember Notting Hill?" Get your Last of the Mohicans references out of your mouth, Fall Guy. This movie isn't worthy to kiss Daniel Day-Lewis's boot.

#17.

What is Stephanie Hsu doing here when she deserves so much better? If this is the kind of role that an Oscar nomination will get you, what's the point?

#18.

I'm hearing a lot about how it's a loving tribute to the art of stuntmen. The thing is, the Mission: Impossible, Mad Max, and Bourne movies — and the Daniel Craig Bond movies too — make me admire and respect stuntmen far more than this because at least those movies have the decency to celebrate and honor them with real screenplays, real cinematography, real creativity, real storytelling, real stakes — aspects that are glaringly absent here. And the action in those movies makes so much more imaginative sense. There is a scene here in which a character is being doused with gasoline — gasoline everywhere! Then, someone lights a match. And somehow, the scene ends with fire only erupting in the places that will allow our hero to escape unharmed. Why didn't anything else catch fire? I couldn't even laugh at the absurdity of it — I was already feeling resentful.

#19.

I'm also hearing a lot of people say “It's fun!” Their ideas of fun are very different than mine. I thought Gosling's Saturday Night Live opening monologue promoting this movie was ten times more fun than the movie itself.

#20.

I've been a fan of summer comedies since high school. But I hold to the apparently unreasonable standard that the jokes suggest they were written. By funny writers. So that they might be lines I find myself repeating and laughing about later. There's nothing in this movie worth repeating.

#21.

Mark this as the film in which Gosling's particular personality became too large for any costume, and now all we will see is the Ryan Gosling-ness of him. I hope I'm wrong. I really liked him when he was more of an actor than an idol.

#22.

I guess I'm relieved that a movie by one of the Coen brothers is no longer the most stunningly frustrating movie I've seen so far this year.

Love triangle aside — what is Challengers really about?

An early draft of this review was originally published on May 4, 2024,

at Give Me Some Light on Substack, months before it appeared here.

Subscribe, and you'll read many of these reviews while the films are still breaking news!

If you’ve seen the trailer or read reviews for the new film from director Luca Guadagnino (Call Me By Your Name) and rookie screenwriter Justin Kuritzkes (husband to director Celine Song who made Past Lives), you know the premise:

Challengers is, on its surface, a twisted saga of two competitive tennis players, Patrick Zweig (La Chimera's Josh O'Connell) and Art Donaldson (West Side Story's Mike Faist). When we meet them, their relationship is a complicated mix of camaraderie, competition, and homoeroticism. But that volatile chemistry becomes unstable when they get playfully combative, and eventually contentious, over another rising tennis star, Tashi Donaldson (Zendaya), a woman who enchants them both. And as Tashi works her magic, we begin to what she wants from playing them against each other, especially when her own career on the court comes to a crashing halt.

The intrigue of two men competing for the heart of the same woman has been popular template at the movies, so critics have plenty of possible precedents to consider for comparison. My personal favorite, an '80s comedy, inspires my suggestion for an alternate title here: Dirty Rotten Sweaty Cheating Power-Serving Scoundrels.

Since this movie's been inspiring lively conversations for months now, you probably don't need me to reiterate the usual talking points:

You don’t need a more detailed synopsis than I've offered here. Most of the joy of the movie comes from riding its narrative rollercoaster from one surprise to the next. (I suspect some of you will scratch this one off your list if I tell you that the scene that serves as the "hook" in the trailer — the one win which Tashi gets both men kissing her at the same time — takes a turn in which the kissing continues, but without Tashi. If that's not a dealbreaker for you, let me tell you, there a lot more movie to discover beyond that, and the part that interests me most — which has nothing to do with shared bodily fluids — is still more than an hour away.)

You've probably already heard that Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross give the film a compelling electronic score that works wonders. I agree, even though I admire their work on The Social Network more.

And you don’t need me to tell you that Challengers is going catapult Zendaya to marquee-level movie-star status (if she wasn't there already). If I have anything specific to contribute to the conversation about her performance here, it's just that I think she strikes me here less as an Oscar-caliber actress and more as a reliably commercial star. And I think that's a bit of the problem for the movie, as both of her co-stars look ready to headline prestige pictures for decades to come. Faist and O'Connor—especially O'Connor—create much more complicated and interesting characters here, by my lights.

But what you probably haven't heard — and I'm amazed that so few of the movie's opening weekend critics bother to mention this — is that Josh O'Connor was doing incredible things on big screens in two feature films while Challengers was getting most of the attention. Check out the layered and thoughtful drama/comedy La Chimera, in which O'Connor plays a troubled tomb-raiding treasure hunter. (It's available on rental platforms now.) O'Connor is one of those rare, unconventionally engaging stars that makes his characters seem complex and ruggedly human, and he's on an unlikely Adam Driver-esque ascent right now. He's going to be everywhere soon, and deservedly so. (He's already been cast in the third Knives Out murder mystery.) I won't be surprised if he and Faist both earn Oscar nominations for their work here.What I find most interesting is how Challengers fits in the weird Amadeus and River Runs Through It genre of movies that ask “Why Is It That Those Who Behave in Self-Destructive and Relationally Self-Sabotaging Ways are the Ones Who Achieve Transcendence in Art?”And that has a lot to do with how I interpret the last ten climactic seconds, which made me laugh out loud in surprise and delight.

I had already come to the conclusion that Guadagnino and Kuritzkes couldn't possibly find a satisfying conclusion for this saga of three-way abuse. But in revealing that this is ultimately about the drive to achieve transcendence in art rather than romance, they redeem the arc of appalling behavior. They’ve found the best possible way to end this very messy film.

I promise not to spoil what happens at the film's climax (that word is, um, unusually appropriate here). But I will say that it's likely to frustrate a lot of viewers with its seeming lack of closure. And I'm going to stubbornly claim that the film’s furious conclusion is, in fact, perfect closure if you’re tracking what the movie is really about, what it values most.

Indulge me for a moment — I’m going to do something critics should probably never do. I’m going to mention… my college band.

There’s a reason for that. Bear with me.

We weren’t great. Only two of the four of us really knew how to play guitar or keys. I was fumbling around with my guitar, trying to find anything that qualified as chords on a keyboard, and sometimes I just pounded bongos. But we were an improv comedy band, and the clumsiness was part of the act.

We didn’t care much if people liked us (although we were invited to play at parties and got the laughs we were looking for at open mics). We played for the joy of it. We played to try to make each other laugh.

But the biggest reason we loved playing together was because we loved finding our way toward something that held together as a song, and when we found something we were excited about — which happened a lot — we experienced something we could not get from any other endeavor. We learned early on that inspiration could come from anywhere, and its arrival was almost always a surprise. That’s what we lived for: those moments when we’d find our way into an unexpected and thrilling cohesion of lead guitar, bass, drums, keys, and melodies that were better than we’d known we were capable of.

In those moments, with the tape rolling, as one or two of us almost competitively strove to deliver surprising and hilarious lyrics on the spot, and as we all tried to stay on beat and in instrumental harmony, we’d look at one another in amazement, hoping that this magic would stay with us for at least the next three or four minutes. In those moments, we brought out the best in each other, and any of the competitive impulse we felt in trying to catch each other off guard or out-perform each other melted away. We’d found another level, and we realized that this was what it was about after all.

I have recordings of almost two thousand songs that we spontaneously discovered in our amateurish endeavors. And I listen to those recordings all the time now, reliving the thrills of surprises that took place while the tape was rolling. How did we do that? How did we start playing a song that did not yet exist, making it up as we went, and every so often stumble into a kind of euphoric jam-band fusion that made us feel more alive than anything else we knew? Why does it feel so good, so rejuvenating, so motivating when we tap into that feeling that we are a part of something larger than ourselves?

Most artists who have been at their art for a long time know what I’m talking about. Either alone or in collaboration, they’ve experienced those rare sessions when something mysterious takes hold, and they work at a level beyond what they know is possible.

I have no trouble believing that career athletes know what this feels like too.

And that is what I love best about Challengers. It’s why the final moments of the film become, for me, profound.

The surface-level appeal of Challengers is the stuff of movies I’d usually avoid or dislike. The characters are reckless, selfish, manipulative, and downright cruel, reducing the ideas of love and sex to power games. File this one under “How to Deprive Yourself of Any Hope for True Love.” To quote Michael Stipe from "Wake Up Bomb": See ya, don't wanna be ya.

But what the movie is ultimately about, in my interpretation, is something important, something I care about deeply, something I pursue, something I miss and hope I get to experience again. For almost everyone else I've read on this movie, this is a movie about tennis and sex. And nothing else. For me, it's about so much more than that. Challengers is ultimately about devoting yourself so fully to an art that you arrive at something greater than fame or victory or anything you could claim as an achievement. It's about discovering transcendence.

As I published this review at Substack on May 4th — Star Wars Day — I should share these thoughts that crossed my mind even as I watched Challengers from the “comfort” of my AMC recliner:

Surely I’m not the only one who realized that the chemistry triangle of Art, Tashi, and Patrick bears a strong resemblance to the chemistry between Luke, Leia, and Han Solo in the original Star Wars.

It fits perfectly (except that nobody is anybody's sibling). Imagine Leia manipulating Luke and Han against each other to bring out the best star pilot or gunslinger in both of them. I mean, we actually get an “I love you” / “I know” exchange here. And Patrick is totally giving Han Solo's "You like me because I'm a scoundrel. There aren't enough scoundrels in your life" vibes.

I won’t be surprised if this inspires some rather R-rated fan fiction.

Oh, oh! We could call it Tashi Station.

Low-budget, high imagination: Riddle of Fire may someday be an all-ages cult classic

An early draft of this review was originally published on April 11, 2024,

at Give Me Some Light on Substack, months before it appeared here.

Subscribe, and you'll read many of these reviews while the films are still breaking news!

Riddle of Fire is now available for rental on a variety of streaming platforms including Amazon Prime and Apple TV+.

Apparently, New York Times film critic Jeannette Catsoulis finds the whimsical new adventure movie Riddle of Fire too drawn out, too tedious. “Viewers may need the patience of Job to remain in their seats.”

Similarly, Michael Sicinski, one of the film critics I respect so highly that I check his Letterboxd account routinely just to see what recent notes he's made, recently posted this—and only this—about Riddle of Fire: "There's nothing wrong with this, and it's actually pretty clever for what it is. The tone just clashes with my sensibility, so I pulled the plug. Your mileage may vary."

Whew — that's not encouraging. If I'd seen those responses before I saw writer-director Weston Razooli's debut feature film, I might have skipped it altogether.

For the record, I'm so glad I didn't. I haven't had more fun at the movies in 2024 so far than I had watching Riddle of Fire — first, with a vocally appreciative audience who were right on its strangely specific wavelength, and a second time with Anne, who couldn't wait to recommend it to friends and family. It's one of those movies that makes me pause and wonder what kind of movies I might have made if I'd followed that passion. One possible timeline has me striving to bring stuff like this — low-budget, high-ambition films infused with childlike inspiration — to the big screen.

And that is probably because it's made in a spirit that reminds me so much of the joy, the improvisational resourcefulness, and the rough edges of making movies with friends in the '80s and early '90s, running around with clunky shoulder-mounted video cameras, and then laughing in a mix of embarrassment and amazement at our VHS tape "dailies" (which were almost always single-take attempts). But that is not because of any failing on the filmmakers’ part. I suspect that disgruntled viewers are suffering a failure of imagination. Or maybe they just missed out on specific experiences that make this movie such a particular joy.

Just as a simple synopsis of Rob Reiner's The Princess Bride could never convey its distinctive tone, its tongue-in-cheek humor, its playfulness with low-budget constraints, or its childlike whimsy, so a plot summary of Riddle of Fire is going to leave readers clueless about what makes the movie special. Suffice it to say that the story is about…

- motorbiking brothers Hazel (Charlie Stover) and Jodie (Skyler Peters)

- and their girl-next-door friend Alice (Phoebe Ferro)

- who are all desperate to make a very particular blueberry pie for the boys’ sick mother Julie (Danielle Hoetmer),

- so they can convince her to give them the TV's parental-lock password

- and grant then access to the hottest new video game,

- which they’ve just stolen from a warehouse —

- but they need special ingredients to make that pie,

- including a speckled egg,

- and the last speckled egg in town has been taken by a grown-man bully (Charles Halford),

- and in tracking that grown-man bully around backroads of small-town Wyoming to recover the egg it for themselves, they discover a witch/taxidermist (Lio Tipton, who I recognized from Whit Stillman’s Damsels in Distress) who controls not only the bully but other lunkheaded crooks,

- and they also befriend a “forest fairy” (who may just be an imaginative mischief-maker) named Petal Hollyhock (Lorelei Olivia Mote),

- and this leads to lots of frightful hijinks in the forest after dark.

Does this sound boring to you?

I hope not. Maybe you’re intrigued — I certainly was — by what sounds like a storyline made up by a fourteen-year-old. And if you find it enchanting, I suspect that you and I would get along well. This kind of kids' storytelling is, indeed, very much my jam.

But again — it’s not just the plot’s hodge-podge of fairy tales or its video-game-task-oriented outline that holds my attention. What I love best about this, and what makes its amusingly preposterous storyline work, is the How of the movie.

Riddle of Fire is a movie that looks like it was made by the same kids who are the focus of the narrative — if those kids had only late-'80s filmmaking equipment available to them, and if one or two of them behind the camera had the ambition and the energy of The Fabelmans' young Sammy Fabelman (that is, the young Steven Spielberg). If I were working in Hollywood and somebody handed me this tape, I’d call for a meeting with the kids who made it. I'd consider having them helm a reboot of The Goonies.

But it’s not as amateurish as I’m making it sound. There’s some real moviemaking going on here — moviemaking by grownups who know what they’re doing and have baked exactly the kind of pie from scratch that they intended to. Riddle of Fire may have been somewhat inspired by Stand By Me or The Goonies, but I think it’s something new; there is no Hollywood polish to any of Razooli’s work here.

The 16mm Kodak film stock, the fantasy videogame synthesizer score, the rural Wyoming landscapes (shot as if they’re a fantasy world of colors either muted and saturated by Jake L. Mitchell), the fantasy-film font that provides helpful subtitles to the softspoken Jodie (and only Jodie!) — every rough edge, every scratched lens, every unlikely exchange, every curse word dropped by a second-grader — it’s all evidence of the artists’ love for their vision, for who they once were, and for what they once loved when they were kids. You can feel that they’re giving themselves a gift — a movie no studio could have conjured for them. Razooli tells Fimdaze that the movie is made of “all my favorite things as a kid growing up in Utah.” He elaborates on what those are: “Everything you see in the movie. …. Dirt biking, paintballing, playing in the mountains, fly fishing, spying.”

The cameras treat the children like movie stars even though the kids are just being as awkward and impulsive and silly as little kids really are. It feels like a home movie — albeit an extraordinary one — that someone discovered on a dusty VHS tape in an attic (except for the fact that these kids have some uniquely fantastical smartphones that come in handy when they’re spying). And if you are old enough to remember using shoulder-mount video cameras or primitive “handicams” to make shaky fake action movies with your friends, you’ll probably love this.

The best equivalent for the singularity of Razooli’s vision might be Jared Hess's Napoleon Dynamite, which won the hearts of audiences by making so much of so little. Hess kept things simple, unpredictable, and quirky (I hate that word, but it’s inevitable here), finding most of his comedy in the idiosyncrasies of his distinctive characters. Riddle of Fire does too, and it will — if it gets enough eyeballs on it — become that sort of cult classic. Where Napoleon Dynamite reinvented the John Hughes high school comedy, Riddle of Fire is stirring some spicy Mad Max into its Goonies/Stand By Me stew, even though the kids’ weapons are paintball guns and their adrenalin-boosting drugs are just gummy worms. There’s even a sequence near the end that made me think of the Gary Oldman scene in True Romance, when the children are dragged before a dangerously unstable young man named Chip (Austin Archer) who is playing at being some kind of gangster.

Perhaps the success that found Hess will eventually come to Razooli. That would be fine with me. But then again, come to think of it, while I’ve enjoyed the movies that Hess made after his success with the “Vote for Pedro!” campaign, none of them, not even Nacho Libre, still shine with the singularity that Napoleon Dynamite had, probably because that first film was shaped by its restraints as much as its resources. As Lars von Trier has demonstrated with his documentary The Five Obstructions, when an artist runs into obstacles they might strike sparks that flare up into inspiration. Even as I hope that Razooli gets to make more movies, I hope he doesn’t forget the secrets of this movie’s recipe. Nothing else in theaters in 2024 tastes anything like this. I don’t need first-rate production values in a pie if there’s this much sweetness, spice, and love in the filling.

I'm disappointed that none of this really worked for Sicinski or Catsoulis. Sometimes critics just can’t find a movie’s wavelength. The great Roger Ebert himself complained that characters in Raising Arizona “talk funny.” (He wrote, “They all elevate their dialogue to an arch and artificial level that's distracting and unconvincing and slows down the progress of the film.”) I suspect that, later in his life, he probably came to accept and even enjoy the Coen brothers’ love for exaggerating accents and for stretching dialects like Laffy Taffy. Here, Catsoulis complains, “The young actors are winsome but inexperienced, too often forced to wrangle improbably precocious turns of phrase.” Frankly, that exact quality is one of the things I love most about the film, and I suspect that’s true of the filmmakers too. It’s exactly why fans are going to find it endlessly quotable.

Now — I feel a nudge to offer a caution: This is a film about elementary-school-aged heroes. And these kids have clearly grown up in contexts that have taught them how to cuss. Be warned! Hard-swearing children!

But if you understand that this is both part of the movie’s comedy and part of its sadness — the film’s most poignant moment comes when the children share the hard fact of their fathers’ absence from their lives — you’ll access another level of this game. Riddle of Fire is about the glory of collaborative imagination among children who need fantasy in order to survive. And that’s a theme I know and love because I’ve lived it.

Playful, nightmarish, fantastical, political: Problemista is all over the place

An early draft of this review was originally published on April 4, 2024,

at Give Me Some Light on Substack, months before it appeared here.

Subscribe, and you'll read many of these reviews while the films are still breaking news!

Would you rather see great storytellers for the screen invest their creativity in television series or standalone movies?

In my devotion to pop-culture’s conversation about movies, I strictly limit my attention to conversations about television series. While everyone’s encouraging me to watch The Bear and Succession and Atlanta and Fargo, I count the cost of such engagement in hours and consider how many movies I might see and write about in the amount of time a TV series would demand. That’s why I still haven’t seen more than an episode or two of Breaking Bad, or even Mad Men.

What’s more — my only opportunities to watch television occur in my limited hours at home with Anne, and as I love her company I will only commit to watching series that also appeal to her. We would rather spend our time together buried in books and filling up notebooks, not staring at screens. And our interests in onscreen art and entertainment only occasionally overlaps. So that limits what I’m likely to watch. (None of the titles I’ve listed above have appealed to both of us, and thus they remain unknowns.)

Am I missing out on great stuff? I’m sure that I am. All the time. But when it comes down to decision-making, I would rather see a complete work of art than an episode that has been largely influenced by a storyteller’s need to keep audiences coming back for more.