Junebug (2005): a brief review

When filmmakers journey to the American South, they enter dangerous territory. Far too often, they aren't prepared to encounter such a rich, unusual culture, and they end up painting cruel caricatures.

So it is a bit unnerving when director Phil Morrison takes us on a road trip from Chicago art studios to North Carolina baby showers in Junebug. Is this going to be just another movie exploiting Southern eccentricity for our entertainment?

Not at all. Junebug is, at times, hilarious, but it is also a deeply affecting drama about a complicated family that finds meaning, hope, and healing in Christian faith and community. We haven't seen such a thoughtful illustration of religious faith since Robert Duvall's The Apostle. Nor have we seen many performances as indelibly endearing as the one delivered here by Amy Adams.

But wait, I'm getting ahead of myself.

The film begins as a sophisticated New York art dealer named Madeleine (Embeth Davidtz of Schindler's List) falls in love with a North Carolina boy named George (Alessandro Nivola). Pursuing a contract with a reclusive artist, she ends up staying with George's family, and the ensuing culture clash progresses from comical to devastating. Madeline, who considers herself professional, stylish, and superior, is humbled to discover the emptiness of her own routine, and the rich resources to be found in family and faith.

Madeline learns a lot from George himself, as he springs into action to help his family in crisis; from his imperious mother Peg; his quiet, patient father Eugene; and even from his troubled, jittery brother Johnny.

But most of her lessons come from Johnny's very pregnant wife Ashley (Adams). Ashley is the intellectual equivalent of an eight-year-old, but her longings, her love, and her optimism overcome anything in her path, even Madeline's sophisticated skepticism.

From the pregnant silences (no pun intended) at the dinner table, to the nuances of Baptist-churchgoer vocabulary, to "colorful" displays of Southern imagination, these people are three-dimensional and compelling, enlivened by an artist of affection and vision. The slow pace, the quiet moments, the empty spaces — they allow us to absorb some of the haunting history, the pain, and the power of this place.

Morrison's next film can't come soon enough.

King Kong (2006)

A full hour of forgettable, underwhelming set-up introduces us to the key human characters of Peter Jackson's King Kong.

That long, humdrum approach to the Main Event - the revelation of the ape - confirms what some have long suspected: that Peter Jackson, who served up those sensational adaptations of J.R.R. Tolkien's The Lord of the Rings, isn't much of a storyteller on his own. As his earlier track record proves, he's a bespectacled spectacle man. When you give him a script that is literary, rich in themes and character development, and efficient in its action, Jackson's flair for the sensational can bring extra power to a good thing. And when you focus primarily on a character drama, he's really quite good with actors. (See Heavenly Creatures.) But if the script is lacking, he tends to revel in gratuitous, albeit awe-inspiring, action.

And the action he's added to the story of King Kong, which expands the original 100-minute classic to a full three-hour epic, is indeed awe-inspiring. King Kong, that famous beast who falls for a beauty only a fraction of his size, is back on the big screen, dazzling us in some of the greatest special-effects sequences ever put to film. In this version, Kong faces down other beasties in fight scenes that have been brewing in Jackson's imagination for decades. These scenes are so brilliantly choreographed that viewers will end up groping around their feet for the jaws that have fallen from their faces.

But what more is there to say about this film? Each hour demands a great deal of the audience. And for many, each hour's flaws will outweigh its payoffs.

The first hour tries our patience. We descend into a New York tested by the Depression. Jackson does wonders with a lively period-recreation montage, but can't find any interesting characters living there.

Carl Denham, played by an amusing but ultimately insufficient Jack Black, is an annoyingly egotistical filmmaker determined to finish a troubled film. As his investors prepare to pull the plug, he grabs what resources he can and dashes for a boat that will carry him to a new location where he hopes to finish the picture. His determination minimizes the fact that his project is ruining the careers of his hard-working colleagues ... and eventually getting them killed.

Ann Darrow (Naomi Watts), the desperate vaudevillian comic he finds just in time to cast her as the star of his picture, is a cliché. Watts gives her all, and could have revealed a deeper and more engaging character if she'd been given the chance, but she's biding her time in the first act, waiting to fulfill her primary purpose as a thrashing, screaming captive. Oh, she's quite good at it. She spends the bulk of the picture either furrowing her brow in fear and bewilderment, or flailing as she's buffeted about like the big monkey's favorite banana.

Oscar-winner Adrian Brody is dealt the worst hand of the three leading actors. After a few scenes that set him up as a charming but frustrated playwright, he's left to wander around the jungle looking for all the world like he'd rather been in a feel-good picture... you know, like The Pianist.

A variety of talented actors fill out the roles of expendable companions, including Colin Hanks as Denham's forgettable assistant, Kyle Chandler as the classic B-movie star who is about to be force-fed lessons in method acting; the great Andy Serkis as a half-mad cook called "Lumpy"; and Evan Parke as the first mate who takes the role of mentor to a meddling young deck hand (Jamie Bell). The screenwriters make half-hearted attempts to flesh out these characters. Serkis speculates about the scary reputation of their destination. Parke and Bell discuss the frightening themes of Joseph Conrad's Heart of Darkness. But why bother fleshing these characters out when they exist primarily to have that very flesh gnawed-upon by the nasty residents of Skull Island, the film's primary stage?

The star of the show, and the character with the most personality, is - surprise - the massive monkey called Kong, even though he doesn't show up until the end of the first hour. Given a complex intelligence and powerful emotion through the motion-capture performances of Andy Serkis, who must have poured as much work into this as he did in playing Gollum, this ape is truly the king of movie creatures. You can't take your eyes off of him. From now on, when you watch Jurassic Park, you'll shake your head and say to yourself, "Kong could wipe these monsters out. All of them at once, if he needed to." You might even shed a tear or two as he strides toward his famous fate - after all, few of us can watch without flinching while an animal suffers.

That first hour ends with the arrival on Skull Island, where Denham's foolishness will send some of these filmmakers to their doom. Unfortunately for them, and for us, they stumble into the territory of an overly pierced and bejeweled society of zombie-native-savages. Jackson's staging of these scenes is surprisingly derivative of his Lord of the Rings battle scenes. The swooping shots of the great wall that these people built to keep out the island's beasts looks like nothing more than a redecoration of the wall at Helm's Deep. And the savages' attack on Denham and company is so over-the-top that it fails to truly frighten us. It's just a lot of noise and trouble, strangely cast in a sort of blurred slow-motion.

The second hour includes one delightful scene in which Kong and his beloved captive Ann (played with the appropriate screams and angst by Naomi Watts) get to know each other; and what may be the most relentlessly astonishing action scene ever filmed (as Kong faces down a tag team of supposedly extinct creatures).

As Kong and Ann develop a delicate intimacy - one built on companionship, thank goodness, and not sexual attraction - we see inklings of what the film could have become if Jackson had spent more time on the characters' relationships. Watching these two, I never stopped to think about the fact that Kong was a digital invention based on Serkis' computer-monitored performance. I completely believed what I was seeing. Jackson is so good at capturing fragile emotions, when he can be bothered to do so, that he and his actors portray complicated emotional changes without any dialogue at all. For a few minutes here, I was watching some supreme big-screen storytelling.

After Ann Darrow finishes juggling three stones for Kong, Kong turns around and juggles three Tyrannosaurus Rexes for Ann. It's a fight scene that ranks among the most astonishing action melees ever filmed. This smackdown begins in the dense jungle, then careens into a deep vine-strewn abyss which suspends the combatants into a sort of hyperviolent mobile, and concludes in a face-off on open ground. (Men, how many of us have ever worked so hard for the women we love?) Jackson's team achieves masterful animation - some of which makes the Narnia events playing on screens next door look positively primitive. This brilliant work makes up for a far less convincing... and utterly preposterous... sequence earlier in the film, in which brontosauruses stampede through a ravine and somehow avoid trampling the humans running between their feet.

But that second hour also includes one of the most unpleasant fight scenes ever imagined, in which our less-than-heroes are attacked by the ugliest creepy-crawlies ever to infest our nightmares. It lacks the suspense and choroegraphy of beastly struggles in films like Aliens, and it fails to achieve the intentional horror-comedy of Starship Troopers. It's just grotesque. If you need a bathroom break during this everlasting movie, this is the time to escape. There's nothing worthwhile about watching these idiots dodge giant mandibles, wrestle with many-legged horrors, and get swallowed by giant fanged leeches. Nor is there anything convincing about the way they use machine guns to blast bugs off of each other.

The storytelling during this part of the film barely registers a pulse - the characters are reduced to mere types, lining up to fight losing battles with various monsters, and escaping through some of the most ridiculous accidents imaginable. (Wait until you see how Ann and Kong get separated at the end of Act Two. I mean, I know we're supposed to suspend our disbelief, but come on....)

And then comes the third hour of inevitable big-city mayhem, as Kong is brought to New York and turned into a Broadway show. It's discomforting to see Carl Denham's madness as he stages a wickedly disrespectful production and takes the money of sophisticated socialites. Isn't that exactly what Jackson's doing? Isn't he taking our money and serving our appetite for destruction? He's entertaining us with the sight of New Yorkers running for their lives in terror while debris comes crashing down from the skies. Didn't we all learn, just a few years ago, that this kind of thing shouldn't be served up for fun? Jackson likes to describe his films as "slices of cake," but in ridiculing the New Yorkers who pay to see a crude and vulgar spectacle, while he proceeds to serve up that very thing, he's trying to have his cake and eat it too.

It didn't have to be vulgar. There is so much potential resonance in this story. The narrative suggests that men and women-well, males and females-who fall in love will have a hard time preserving that love during the merciless march of progress. It suggests that we aren't as civilized as we think we are, and the big city is just another jungle. It suggests that we respond to nature with fear and a dangerous drive to apprehend and control it. It explores the role of entertainment in culture-a salve for loneliness, a balm to our irritable tempers. And on, and on...

There are some stirrings of those themes here, but they never catch fire. Jackson's too busy charging from one major action scene to another. He builds to the ape's legendary ascent of the Empire State Building with so much intensity that you can tell he cares more about this scene than about anything in his Tolkien adaptation. But he hasn't given us reason to care about this moment nearly so much. Kong's last stand is another spectacular visual display, make no mistake. But Jack Black's closing words land with a pathetic thud, and that's it... time to head for the exits.

In the end, this version of King Kong, the fulfillment of Jackson's lifelong dream, is a special-effects extravaganza that pummels us senseless. It reflects a great deal of enthusiasm on the part of the filmmakers for the original RKO film of 1930, but it assumes that we are enthusiastic about the same story. You may be, and if so, the film might knock more than your socks off. But it's likely that the film will engage only your senses, falling far short of any meaningful contact with your mind or your heart.

"Beauty" may indeed have been Kong's downfall, but Jackson's downfall isn't beauty — it's how he has diminished some beautiful moments by indulging his love of chaos and sensationalism. It makes us just too tired to care, and that's a major miscalculation. Something's gone wrong if our strongest emotional response to Kong's conclusion is relief.

The Hard Work of "Levity": A Conversation with Director Ed Solomon

Ed Solomon's directorial debut-Levity-offers little of just that. This might surprise moviegoers eager for the latest from the writer of Men in Black. Fittingly, the title refers to what's missing from the lives of its burdened characters.

Ed Solomon's directorial debut-Levity-offers little of just that. This might surprise moviegoers eager for the latest from the writer of Men in Black. Fittingly, the title refers to what's missing from the lives of its burdened characters.

Solomon is a moviemaker with a lot on his mind, including forgiveness, faith, friendship, and the way we run from self-realization and dodge the consequences for our sins. These themes needed richer soil than his previous scripts for Bill and Ted's Excellent Adventure and Charlie's Angels.

I had the privilege of meeting and talking with Solomon during a brief stay in Seattle where he was promoting the film. He was remarkably soft-spoken and humble, clearly glad to have a conversation instead of trying to pitch his movie. Here are some of the things we talked about.

(My review of the film Levity can be found here.)

Jeffrey Overstreet:

I would think that after working so hard on mainstream comedies--Men in Black, Charlie's Angels, the Bill and Ted movies--it would be quite a change for you to work in such a ponderous dramatic mode as you do in Levity.Ed Solomon:

Everyone is complex... just by being a person. I think it would be very hard to only work from one angle, on a personal level, but on a professional level it's really tempting to always try to work where you're comfortable, or where you're reinforced professionally to work... either by people who hire people who go see the movies. It's tempting to really to work where you feel safe. But I feel that, creatively, it's kind of deadening.Especially when you get older, and I guess I'm getting older. I'm 42 now. I see a lot of my friends say, "I'm in my 40s now, so I'm gonna cash in. I'm gonna do what comes easier. I've worked hard enough." I feel the opposite. I'm getting older, and in order to keep growing, I'm going to push myself.

I don't believe in the "Write What You Know" thing. I think you write what's true for you or intriguing for you or what you feel. What you "know" is, I think, wrong.

I have a lot of confusion about issues... like spiritual ones. I'm not coming to this film from a place of knowledge. I'm not trying to present a religious point of view. I was trying to really explore questions. I think we all have different stories in us at different times of our life. To me, it's really important to follow something that's more creatively challenging or pressing to me than to just constantly fall back on what you know. I love comedy, but I'm just trying to keep pushing myself.

JO:

I would think after writing comedy so long, you would start collecting and building up things that don't fit in a comedy, or ideas that you couldn't really explore thoroughly in comedy. And I got the feeling from Levity that you were letting out a lot of ideas that had built up.ES:

It's true. Things stay with you and they well up... these creative or emotional assets that have been building up over time, things you forget about. They surface again.JO:

Is this a story you developed over a long period of time?ES:

I was a tutor in a prison for teenagers when I was in college. I met this kid who had killed somebody and had been tried as an adult and sentenced to life in prison. And he kept a photograph of the person he had killed. The judge had told him to keep this and have it, and the judge also made him hold things of the boy...grapple with them... hold his clothes...I remember him saying "I had to hold his football."He was staring at this picture, he would put it in his pocket, take it out, look at it, put it away, take it out again, open it. He would stare at it like he didn't know it was a human being, like he was trying to take this two-dimensional image and have it become three dimensional. And then he was gone; he turned 18 and he went to the state prison.

[Solomon pauses, staring intently into his memories.]

It's funny. I was just thinking: What ever happened to him? I don't know. I don't know if he's out of jail. He was sentenced to life, but that was 25 years ago, so who knows?

That kind of haunted me. And then in my mid-20s the idea of the movie came around. It was a different take on it. A lighter take. Morgan Freeman's character was taking Billy Bob's character and trying to help him take charge of these kids who were trying to be comedians. I could never get it to feel right. 30 or 40 pages in, I quit and I tried it again. I held it out saying "One day I'm going to get this right." I almost gave up. Finally I said, "I'm just going to do this. I'm just going to get it right."

JO:

There are clearly echoes of that experience in the character of Manual, in his "grappling" with the crime he committed as a teenager. He grapples with the reality that there had been a human being on the other end of that gun.I like what you say about asking questions through your storytelling. I think the movies that last and that really mean things to people are often those where the artist doesn't have a pulpit and a message. Instead he doesn't really know what's going to happen. He's exploring, and bringing the audience along with him. And I really felt that sense of uncertainty, of questioning in Levity. It kept throwing me curves.

Was there a preacher or a minister that inspired Evans, the character played by Freeman?

ES:

No, this was the first time I wrote a character with an actor in mind. It came out of how I heard Morgan and felt his presence. He rejected the character the way I initially conceived it. It was my perception of what he could do rather than what he could do or wanted to do as an artist.I contacted this Christian guy [I know]... Jim... and faith is a big part of his life. He worked with kids in South Central L.A., kids trying to get out of violence and really turn their lives around. Jim introduced me to a couple of people who had committed crimes, and I talked to some of them. He wasn't a preacher, but he really inspired me in some ways.

There wasn't a pastor, per se. It was more of a voice, a kind of counterweight... I always saw Manual's character as constantly looking at himself and obsessing over the minutiae and details of what he had done, and in so doing he's terrified of what he is capable of. I called him ‘Manual' because of what he is capable of -Manual means "by hand." I didn't mean to use "Emanuel", to give it any kind of religious connotation.

[He pauses and smiles.]

But then again... I did call him Manual Jordan... didn't I?

JO:

That is rather loaded!ES:

I was thinking of the river, yes. But I called him Manual because by his hands he removed himself from the flow of the human race. He looks at himself. But I was drawn to the character of Evans (Morgan Freeman) because he preaches with such fervency but he doesn't believe what he is saying.JO:

In a sense, Evans is a good actor.ES:

Exactly. And with them, I wanted to raise questions:One - Can you make up for one so-called bad act with any number of so-called good acts?

And two - Are you what you say you are, or are you what you think you are, or are you what you do? Or is that even answerable?

I was intrigued by the idea that people can go out of their way to help other people but they can never help themselves. Other people just help themselves and never help anyone else.

To me, Morgan's character never helps himself. I told Morgan that I imagined his character to be a guy who's always being followed by rising waters, and it's only a matter of time before the floods come. So he is desperate to have value in this life, he grabs whoever he can and puts them up on higher ground and then runs before the water comes. I don't think Morgan's character is a preacher; he's just going to act as one, and in the next part of his life he's going to be someone else. But I always thought because Evans won't look at himself, he's destined to run, constantly. Manual (Billy Bob) is constantly looking at himself.

When Evans says, "You know where you are. You know exactly where you are!", Morgan is playing that scene such that he's talking to himself. The line "I'm lying through my teeth." ... that's one of the two times in the movie that Evans is telling the truth, the other being when he tells Manual at the end who he is. There's a reason he's awake 20 hours a day; it's desperation. There's this frantic need to try to do anything he can to feel like he's saving himself when the only thing he's not doing is looking at who he is truly. He's running.

Everything that I'm saying... I'm not a Christian. I'm not a practicing Jew, although I was born Jewish. I'm a struggling agnostic. I'm not an atheist-you have to have a pretty strong conviction to be an atheist. But I'm not coming at this from a Christian perspective. When I look at Morgan as trying to save himself, I'm not trying to talk about that in any kind of Judeo-Christian way, although there are parallels for sure. It was not me consciously trying to make a religious parallel.

Some members of the secular press have just attacked me for trying to make a "Christian film." Initially, I was mad. I asked, "Why? How do you get that from this?" And then I was amused. "Oh, okay, I guess everyone has a right to read in what they want." And then I started thinking about it and I thought, "Well, what's wrong with that anyway? What if I was? Why not?"

JO:

So, you may not coming at this from a Christian perspective, but this narrative reminds of narratives throughout Scripture, stories of people who have profound encounters with God, and they're left with sobering questions. I think of Job crying out to meet God and when he did, it was disorienting. Many of the people most actively searching for God or most aggressively and passionately wrestling with spiritual issues end up being humbled by the truth and constantly admitting that it leaves them with questions.That's one of the strengths of exploratory storytellers, the thing you're doing with Levity. You know you're in trouble, — even in the Church — when the people you're around, Christian or otherwise, start acting like they have all the answers to all of the big questions, and that it's their job to force their answers on you. In that behavior, they have turned away from a humble, reverent, awestruck vision of the truth... they've cut themselves off and appointed themselves the end-all and be-all of truth. They're just trying to make a point.

ES:

You're right. And when you behave that way, you don't even necessarily make the point. You just give people the impression that you do.JO:

Will you come back to this theme again?ES:

I'm intrigued with trying to be truthful about the struggle. I'm trying to write from that place. The definition of Israel is "people who wrestle with God." I think that's fascinating.I wanted the film not to be clearly spiritual or clearly realistic or clearly impressionistic. I wanted it to be metaphoric. I wanted the world that the film takes place in to be a subjective world that mirrors the life of the central character. I wanted people to project onto the film, but I didn't expect people to do so to the extent that they are. I didn't expect it to be controversial.

I also knew that by making a film that was more subjective than naturalistic, it would spark with some people.

If you take somebody's life, it seems to me that there are two main ways that you reconcile... one in the secular world and one in the spiritual. In the secular world ... you do whatever the legal system says is suitable. You seek forgiveness from others or from yourself.

If you are a spiritual person and you believe in God, it's not like it's easier. If you're a Christian you choose Christ as your vehicle for redemption; dramatically, it wouldn't have been interesting. It would have been too easy.

So I thought, dramatically it would be more interesting for the character to say, "I don't want to be forgiven." And so he becomes so desperate to lift this weight off his shoulders. He tries a lot of different things. But ultimately he doesn't think he deserves anything.

Most mainstream movies make me eager to part company with their shallow, ill-mannered characters and cheap answers. Solomon challenges us with something more, something deeply personal... questions. Just as he sometimes wonders what happened to that incarcerated teen, after watching Levity we are left wondering where his metropolitan pilgrims' progress will lead them. Do they have any inklings of real hope? Have they learned lessons that will quench their longing for relief, levity, and joy?

These questions suggest that the movie's work is not over after the credits roll. That's when we have the opportunity to turn to our fellow moviegoers and really get to the heart of things.

The Lives of Others (2006)

At the movies, transformations are the norm. Men become monsters and beasts are transformed by beauties on a regular basis. The formula is so familiar that storytellers and artists face a tremendous challenge if they hope to capture audiences with a sense of something new.

Remember Schindler's List? In Steven Spielberg's beloved Holocaust film, we watched Oskar Schindler begin to question himself and his superiors. He gradually mustered the courage to take a small step in the right direction. And yet, I still feel that Spielberg's film went too far, celebrating a man's redemption with a climactic fireworks display of emotion. Scenes like that prevent us from thinking about the journey; we're instead commanded to feel, feel, feel!

The Lives of Others is an example of a transformation tale done right, portraying the awakening of conscience in the heart of a "dead man" through incremental progress that feels true to life. Damascus-road encounters do happen, but they are extremely difficult to portray. Most of us experience change in stages, through a long sequence of events. How do you illustrate an event so shattering that it changes a man, heart and soul, in a moment?

The villain in question does things that the audience will find repulsive, and yet there is a glimmer of hope for him in moments of hesitation, in expressions that suggest a void or a need in his heart. And the movie pulls this off without overbearing sentimentality, without working too hard to please the crowd.

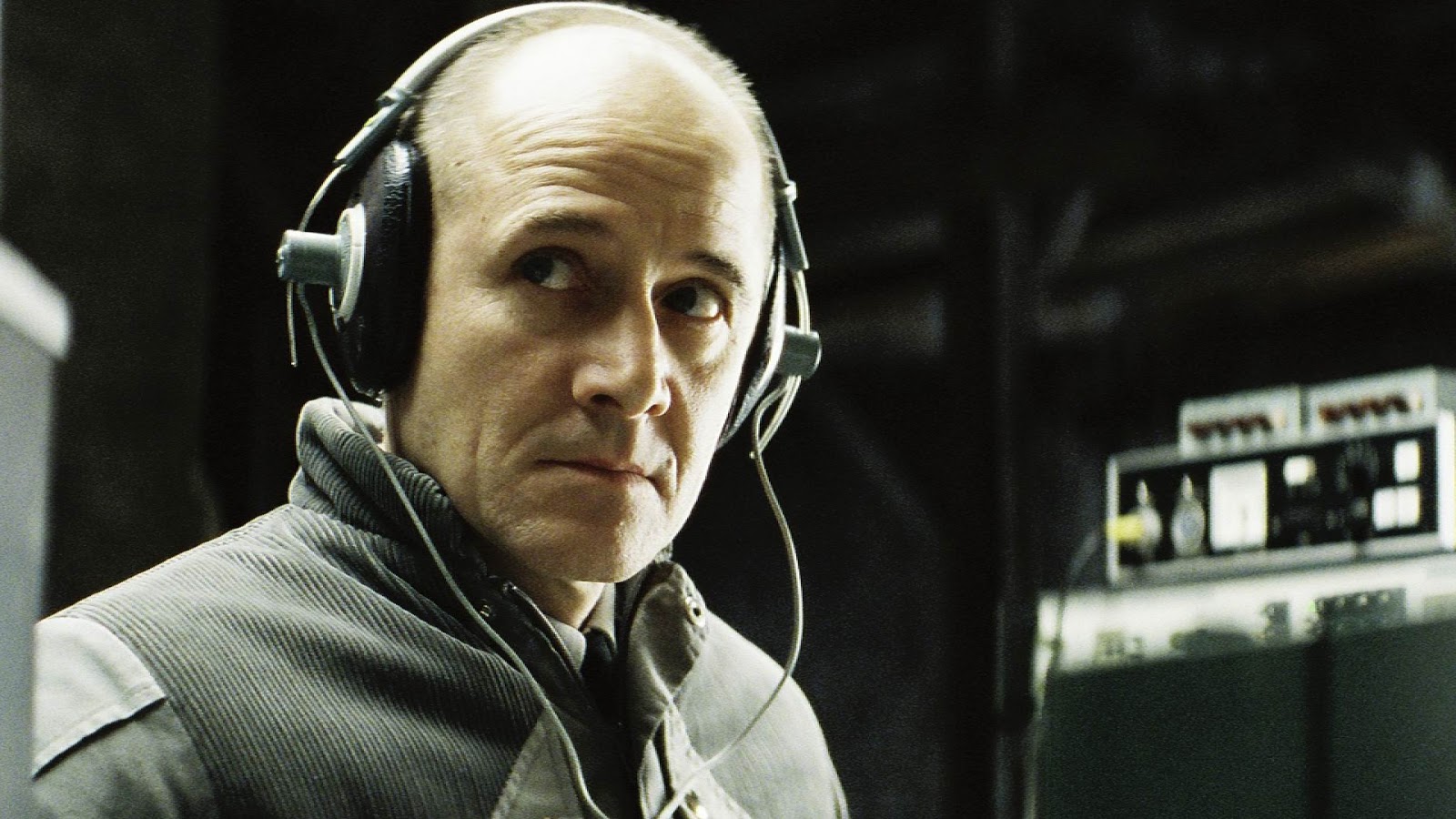

The Live of Others is about a monster named Gerard Wiesler (Ulrich Mühe) who lurks in East Germany, working as a surveillance officer for the Stasi forces during the mid-1980s. When Wiesler is appointed to monitor every move and every conversation in the apartment of a writer who may have anti-socialist sentiments, he finds that it's not quite so easy to resist the allure of their convictions.

Like Hamlet's wretched uncle forced to watch a play that reveals his own wickedness, Wiesler begins to realize the darkness of his own empty life. Starved for light, he begins to long for the freedom and virtue that his targets fight to defend. Ultimately, he cannot live with the fact that his actions might crush the very thing he secretly cherishes.

"The play's the thing to catch the conscience of the surveillance officer," except that in this case "the play" is not a charade. The play is the true-life interaction of good men and women, which goes on daily while he watches from the shadows. As he begins to understand the consequences of his actions, his frozen heart begins to crack and melt within him.

In that sense, the film is about the divide between government and "the common people," and how those who live insulated by walls of power and privilege may fall victim to delusions about the rest of the world. In order for balance to be restored, this officer must come out from behind his shields of suspicion and condemnation, and he must reckon with how the people of East Berlin truly. When he does, it isn't so easy to persecute them. (As Wiesler struggles, I imagined Damiel, the guardian angel assigned to Berlin in Wim Wenders' Wings of Desire, whispering in his ear to cultivate his conscience.)

The film is also a fine testament to the power of art. As these government agents seek to ensnare the playwright before he delivers any truly subversive work, it is clear that they are driven by fear. But fear such as theirs grows from insecurity, from the knowledge that the truth will not support them in the end, whether they admit it to themselves or not.

As Wiesler, Ulrich Mühe is fascinating. As he listens to the secrets of a playwright named Georg Dreyman (Sebastian Koch), his actress girlfriend Christa-Maria Sieland (Martina Gedeck), and their conspiratorial friends, his face is like a death mask, reminding me of our first glimpses of Hannibal Lecter in The Silence of the Lambs. But Wiesler isn't nearly so frightening; the film does not seek to impress us with his influence so much as to communicate his feebleness, his suppressed longing for freedom, his emptiness. Hagen Bogndanski's cinematography is modest and sufficiently moody.

The Lives of Others is being interpreted by some as a timely commentary on the endangerment of citizens' rights in America. I suppose you can read it that way, if you really want to try and compare the oppressed Berlin to, oh, Seattle, where I doubt many playwrights have found taps on their telephone lines.

But this is not primarily a political film. Director Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck is investigating matters of the heart. Can a human being have a change of heart? Can a selfish man learn to be selfless? If so, what brings that about? And where does such a reversal lead him? The answer is clear. But The Lives of Others illustrates it with only a dash of sentimentality, so that we have to face, along with Weisler, the truth that integrity leads to vulnerability and sacrifice.

The film's only misstep is its closing scene, which feels somewhat contrived. If it had ended just a few moments earlier, we would have been left with a tantalizing question mark, which is always more haunting than an exclamation point.

I loved The Lives of Others. I hope you get to see it ... before Sydney Pollack and Anthony Minghella deliver their completely unnecessary American remake, which I suspect will appeal to our emotions more than this admirably restrained piece of work.

As I watched Wiesler listen to his headphones, surrounded by the instruments of voyeurism, I thought of our own media-saturated culture, and how much of my own time I spend spying on "the lives of others" through film and television and news media. Am I attending as closely as Wiesler? If so, what am I looking for? Am I merely entertained? Am I open to seeing the truth and being transformed?

Read an Excerpt from Cyndere's Midnight

A magnificent viscorcat paws at the trunk of the coil tree, yearning for a summer sun spot up in the branches, his black fur glossed from grooming. The cat’s rider, a girl no more than thirteen, slides from his back.Impatient, the cat claws neat lines down through the bark. “Go ahead, Dukas,” says the girl, running her hand from his neck to his tail, tracing sturdy links of spine through the fur. The cat leaps into the tree and stretches out on a sun-warmed branch.

The girl is tempted to follow. She has wandered far from her lakeside caves, feeling confident as a queen. Her realm has provided everything she might need–nourishment, shelter, color, and materials for her art. But she has yet to offer something in response.

She descends through fern fronds into a quiet glen and finds a place to rest, sitting against a young cloudgrasper tree. Rummaging through her ribbon-weave bag, she considers an array of unfinished crafts. Blue curtains–she’s making them for Krawg, the old man who rescued her from the wilderness when she was a baby. The floppy, fur-spun hats are for the Gatherers. There are lake-fishing lures of dragonfly wings and throwing dice fashioned from acorns. But none of these seems the right subject for this afternoon’s play. She shoves them back inside and listens to the trees’ ideas.

A murmur of water deep underground draws her into a stroll around a flowered mound of stones, a weathered well. Something about that distant song is familiar. How curious, she thinks. Why would anyone need a well here?

She climbs up on the wellstones. Ivy has stitched the well’s mouth shut, shielding it from summer’s slow, golden dust. She tears the ivy loose and shoves her head in, then withdraws, brushing cobwebs and tiny white spiders from her silverbrown hair. Her eyes are wide. The sad, familiar music of the rushing water far below inspires her to imagine its source–a place of fierce purity, high above the world, in skies alive with color and light.

Inside the well a rope is bound to an iron ring. She seizes it and feels resistance. Persisting, she pulls until a sturdy bucket appears. Swirling water mirrors the layered ceiling of dark boughs, delicate leaves, the shining sky. She splashes it across her face. It is surprisingly warm.

She pours the water over the wellstones, washing away dust, webs, fragments of leaves, old spider-egg sacs. Beetles scramble, looking for new homes.

Arranging small glass jars of dye beside her, she takes tiny brushes of vawn-tail hair and sets about painting.

She daubs one wellstone, pauses, considers what should come next. Proceeding like a worryworm, she feels around for a sure step, then teases the air before her in search of the next certainty. She examines the cloudgrasper, its bark green as olives. She scoops up handfuls of leaves, lays them over each other, holds them up to the light. Mixing the paints and spreading them thick and bright across another boulder, she considers how the colors fit. She wishes for more stones, a larger well, something mountain-sized.

When she is finished, Dukas has dropped down from the tree, disgruntled by the fading sunlight. He sniffs at the well, blinks, and sneezes in disgust.

The girl scowls. “Thanks for nothing.”

Dukas slinks off to search for a madweed patch where he can roll and dream, leaving her to grumble. “But I suppose you’re right,” she sighs. “I mean, what’s the use?” She shrugs and tosses the paintbrush aside. “Who’s ever gonna see it? Just a pile of painted stones. In a few harsh winters, it’ll all be gone.”

The cat snarls, dragging his claws down the trunk of a maple this time.

“Hunting and eating. That’s all you think about. You know you’ll be fed by sundown. I’m hungry too. I just can’t say for what.”

A cloud passes over, hastening the night.

“We should go.”

While she gathers up her brushes and jars, buds open on the frail stems, blessing the glen with their tiny, cerulean stars. “Why bother?” she snaps at the flowers. “Nobody notices.

The Passion of the Christ - A Letter to Christians about Mel Gibson's Film

This commentary is a follow-up to my review of The Passion of the Christ.

-

Most Christian press publications will lavish praise upon Mel Gibson's The Passion of the Christ. They will celebrate the arrival of a film rich with spiritual power, rendered with riveting and even excruciating detail.

Some will go so far as to declare that in this film, the Church has a fantastic "evangelical opportunity."

But the fact that many Christians — many churches — are responding to the film as if it is a call to arms, an exhortation to use Gibson's work as a blunt instrument of evangelism, reveals that they are blind to one of the very things that makes many people steer clear of the Gospel.

People view Christians as self-righteous. They see believers as thinking they have all the answers. They see us as confrontational, militant, ready to ambush them with a sales-pitch for Jesus.

This very thing happened this morning in Dallas. A crowd of believers and unbelievers filed into a cinema, experienced a work of intense and complicated art... something that requires a good deal of time for recovery afterward... something that requires contemplation.

But just as the credits started the roll, and while the music was just beginning to soar... the system was shut down.

A team of ministers appeared on stage.

The gospel was explained and an altar call was held.

Some filed out... believers and unbelievers alike... astonished that they were not allowed to absorb the film and think about it. They were ambushed, taken advantage of, while in a state of high emotion.

This is wrong... just plain wrong.Read more

The Passion of the Christ (2004)

"There is nothing less real than realism. Details are confusing. It is only be selection, by elimination, by emphasis that we get at the real meaning of things." - Georgia O'Keeffe

-

The words “excruciating” and “crucifixion” are related. It’s easy to see why when you read the reviews of Mel Gibson’s The Passion of the Christ.

Violence is not a new subject for this actor-turned-storyteller, and here he zooms in on a singular theme: how Christ persevered, in love, restraint, and forgiveness, through the unimaginably harsh physical torment of his last twelve hours.

Having access to the film at last, critics find themselves divided. Some applaud the portrayal of Jesus’ final hours while others are throwing rotten tomatoes.

Nevertheless, these critics agree that watching it is indeed an excruciating experience. For many, seeing Jesus’ physical misery vividly, graphically and relentlessly illustrated only serves to heighten their appreciation of Christ’s love for humankind. For others, Gibson’s hyper-realistic violence is gratuitous, an act of cruelty carried out upon the audience by an agenda-driven, heavy-handed, insensitive director.

I first shared news about the film in my Film Forum column in August of 2002. I’ve reported on the growing controversies, attacks, and defensive maneuvers almost weekly for more than two years. It is a great relief to finally have the work to discuss, and to be done with rumor and speculation.

Now that I’ve seen the film, I find myself with a foot in each of the two critics’ camps. The Passion of the Christ succeeds in that it does just what Mel Gibson set out to do: it focuses us on Christ’s willing, determined march through the destruction of his body. He reminds us that this man never quit loving us, never quit forgiving his enemies, even as they tore him to shreds.

But the question must be asked: Is it appropriate and wise to bring this narrowly focused work into a multiplex, where moviegoers do not know the rest of the story? Is it fair to exhibit this bloody exhibition when viewers do not necessarily know what the hovering dove symbolizes, who Judas was before he came to Gethsemane to betray Jesus, who any of these disciples are, or how Jesus’ teachings differed from the teachings of the Sanhedrin?

I believe that this is an ambitious film, even a great film — but a flawed film as well.

The Passion of the Christ is not the Fifth Gospel — even though many of its passionate defenders will treat criticism as blasphemy. No, it is work of art with strengths and weaknesses, for it is made by a human being who has strengths and weaknesses. There is no sacrilege in pointing out the work’s weaknesses. Nevertheless, those Christian film critics raising some questions about the artistry are already being challenged and asked if their priorities are out of line. They should not flinch. If God cares about excellence, would he not want people to pursue excellence in how they tell his story?

This movie review is not an attack on the Gospel, nor is it even a condemnation of this film. I am glad the movie was made. I hope that moviegoers will choose wisely about whether or not to attend. Those who do... well, I hope they make time to contemplate what they've seen, and discuss its strengths and weaknesses with others.

Are you with me? If so, let's proceed.

Violence: Realism Can Be a Virtue... and a Problem

Gibson includes the basic events of Christ’s last hours, and adheres remarkably well to the dialogue and descriptions in the Gospel. Thus, his film is powerful. How could any decent account of the events on Calvary fail to move audiences?

The way the director and star of Braveheart weaves together Christ’s suffering and flashbacks creates interesting juxtapositions. At each stage of Jesus's torture, we are reminded that he prophesied these very events and that he willingly and courageously gave himself up to suffering. With every new stage in his anguish, we are reminded that these punishments come as a response to his teachings about love and turning the other cheek. Each blow struck by the enemy is the antithesis of the sort of power he endorsed.

But Gibson’s lack of attention to other chapters in Christ’s life does indeed pose challenges to viewers — especially those who do not know the gospel story. We receive only glimpses of the Sermon on the Mount and the Last Supper. We are given no reference as to how Christ entered the world. Each audience member is left to seek out the missing parts and piece together what it all means.

Will they?

That depends. It is possible that the anxiety and exhaustion they experience viewing the film will give some of them an aversion to exploring Christ's life on a deeper level. Others may be inspired to investigate.

In The Passion, the path from the garden of Gethsemane to the cross is such a marathon of bloodshed — Jesus is beaten and bloodied even before he’s out of the garden — that I found myself a bit dizzy from the violence only an hour into the film. It became harder and harder to focus on what the director was trying to reveal concerning Christ’s teachings and his love.

This is the problem when art makes realism too high a priority.

When a filmmaker becomes too focused on clinical, bodily details, it is harder for him to keep his audience thinking about the themes of the story. The more Gibson emphasizes the way in which Jesus's body is pulled apart, the more viewers are reacting and enduring instead of contemplating and seeking deeper, richer understanding.

Any decent human being portrayed in physical agony will draw an audience’s sympathies. If you see a film of a total stranger trapped in a burning building, you are drawn to rigid attention, hoping to see him escape. This film is not just about any Average Joe. It is about the Christ. We should be thinking about what makes this suffering different. Gibson does help us think about this to some extent, but it is this viewer’s opinion that he disrupts our ability to do so with his insistence on delivering every grisly physical detail. I wanted to know more about this suffering figure. I wanted to see more about what made him distinct.

But this movie is more interested in the particularities of violence than in the particularities of the one who suffered it.

Seeing so much brutality, my emotional responses went numb. Eventually, I found myself merely watching, wondering what kind of "body cast" actor Jim Caveziel was wearing in order to create the illusion that barbed whips were ripping chunks out of his flesh. Endless cracks of the whips, the wearying mockery and maniacal laughter of the tormentors (which is so exaggerated that I quit believing they were human), and the numerous sequences that show Jesus collapsing in every imaginable way… these things went beyond “showing us what he suffered” and became more of an endurance test. Contemplation was replaced by skepticism: “How long will Gibson drag this out?” If you answer that by saying, “Well, this is what it was like!”, my response is, “We have no way of knowing that." The Bible says that he was scourged. (Matthew 27:26, "But he had Jesus flogged, and handed him over to be crucified.") There is no indication that every inch of his body was torn open so that he nearly died at the post.

Some have argued that this is Gibson the artist employing "artistic hyperbole" as an expression of how far Christ would have gone for us, an expression of how all of the world's sins throughout time were delivered upon him. It is indeed a case where Gibson uses artistic license. But I believe that he makes our apprehension of Christ's pain more mundane by merely focusing on the relentlessness of the blows. A subtle stroke, an expression on the face of an observer, the sound of a cry heard from far away... these things can hold far more power than giving us gory close-ups. Moreover, they show us the extent to which one man's pain is felt by those around him, and expand the range of what can be communicated in that moment.

Restraint is more powerful than indulgence.

I experience Christ's physical agony more poignantly in the words of the song "Oh Sacred Head, Now Wounded" than I do in watching a realistic recreation of the actual beating, just as unseen monsters are more troubling than those that are dragged out into the daylight.

The problem with Gibson's approach can be summed up in the example of the dead donkey.

When Judas is at his wits' end, we see behind him the corpse of a dead and decaying donkey. The donkey is somewhat out of focus, but we can still see something writhing there in the cavities of is disintegrating flesh. This... just this... makes an impression. We recoil. We can practically smell the death. It is a brilliant suggestion that affects the whole picture. But Gibson is not the sort of filmmaker who can restrain himself and trust the audience to get the subtlety of that moment. No, he moves in for a few long close-ups of that decomposing corpse, so that the maggots can be seen clear as day, driving even the most distracted or hard-hearted viewer to squirm.

This also is his approach to Christ's physical suffering. His tendency towards excessive force interferes with his attempts at visual poetry. The realism of the portrayal is indeed impressive, but it comes at the cost of thoughtful storytelling.

Flannery O’Connor said that for deaf audiences, a storyteller must shout. Contemporary audiences may indeed be somewhat deaf to the story of Christ. But I would add that if you shout too loud and too much, you’ll only further cripple your audience and bring your credibility into question.

Moreover... there is more to examine here than violence.

A Film That Gives Us True (And Jewish) Heroes

In Gibson's version of the story, the bloodthirsty Roman soldiers abuse Jesus and his faithful Jewish followers — they use the word “Jew” as an expletive. If this film were, as many are describing it, an attack on the Jewish people, why then would it draw us into sympathy for a persecuted Jew, his Jewish mother, their Jewish companions? I am no scholar on anti-Semitism, so maybe I'm missing something. But this seems fairly obvious to me.

The Romans — shown here as persecuting an entire people — are clearly portrayed as monsters. No one in their right mind would admire or feel any sympathy for these beastly soldiers. Gibson is clearly repulsed by them. I do not sense him aligning himself with these hateful people.

I do feel, though, that in showing the reactions to Christ, he is showing us his own sense of guilt and culpability in disappointing, denying, and wounding Christ. I believe any honest viewer will feel a twinge of conscience when they think about how they fall short of the glory of God.

It is true that Jewish religious leaders are portrayed as calling for Christ’s crucifixion, but that is not cause for anti-Semitism. That is a warning about how power — especially religious power — can lead to the abuse of that power. This is true in any religion, even Christianity.

Several prominent Jewish characters are shown having deep sympathy for Christ.

In fact, Simon of Cyrene, one of the few supporting characters given any sort of personality or character, has an even more inspiring role here than the gospels describe. During the long march to Golgotha, he develops a wordless, intimate bond with the Savior that becomes one of the film’s most resonant and beautiful highlights.

Let’s not forget that Jesus himself was Jewish. And his mother. And his beloved disciple John, who receives Jesus’ final tangible gift… Jesus’ own responsibility as Mary’s son.

Superior Contributions From Cast and Crew

Aside from the film’s firm Scriptural foundation, Caleb Deschanel’s cinematography is The Passion’s greatest strength. His mastery of light and darkness and careful framing of panoramic pain captures some of the most breathtaking religious imagery ever filmed. Experienced in smaller doses, I would find any section of this film deeply moving on that basis alone.

It helps that Deschanel has such talented actors performing within his frame. Jim Cavieziel’s commitment to showing us a convincing Jesus Christ is unnerving in its intensity. Not only does he speak Christ’s words in Aramaic as though he grew up with the language, giving us the feeling of time travel back to the real events, but his physical manifestation of Christ’s internal turmoil is as compelling as the blows his body suffers. Acting his way through layers of makeup and special effects, he communicates Jesus’ immeasurable restraint. We can see in him, and in the amazement and dismay of his followers, that Christ is holding back, refusing to indulge his heavenly influence to save himself. This Jesus speaks volumes through the silent gazes he shares with his faithful, especially Mary.

Romanian actress Maia Morgenstern is a strong, believable, sympathetic Mary. The intuitive mother/son bond between her and Christ plays more intensely than I have ever imagined it. In one moment, when Christ pauses, exhausted from carrying the cross and yet having only just begun, he turns to her and groans, “See, Mother... I make all things new.” It is a moment loaded with irony and anguish. And yet he speaks the truth — his endurance of the crucifixion, through death to resurrection, will transform the abuse, making it possible for his followers to suffer persecution while never losing grasp of their faith and their hope. The prophecies foretold that these things would happen and the film reminds us of that. Thus, with everything pointing to Jesus, he fulfills his promise, overturning our understanding of life and death, and showing us the victory.

In one of Gibson’s few truly inventive choices, Mary’s grief, suffering, and love are mocked by the most sinister Satan audiences have ever seen, an androgynous figure who can only mock and lie, a warped mirror that distorts everything good, including, in one horrifying instance, traditional images of Mary cradling the Christ child. Actress Rosalinda Celentano brings to life a truly alien presence, something that does not belong in a world God has made, something that exists solely to destroy.

Hristo Naumov Shopov’s performance as Pilate is also worthy of note. The Pilate of the script by Gibson and co-writer Benedict Fitzgerald does not demonstrate the cruelty that history attributes to this figure. But Shopov gives us the Pilate of the Gospels, a man anxious to be rid of any matters concerning the Jewish law and the brusque, manipulative religious leaders. After all, being a Jew-hater himself, he considers their arguments unworthy of his attention. However, his fear of their strength requires him to get involved. Pilate's prejudice, arrogance, and cruelty are indeed reprehensible. Thus, his hesitancy to condemn Jesus and his sense that there is something special about this man, gives a fascinating complexity to the scenes of interrogation and judgment.

The rest of the characters are disappointingly flat. There’s nothing memorable about Peter, who merely gapes, denies, and cowers. John remains misty-eyed and solemn. Who are these guys? Where did they come from? That is not what Gibson is interested in, but alas, audience members unfamiliar with the gospel will have little reason to care about these nondescript men.

Mary Magdalene, presented as the woman caught in adultery (a tradition in Christian art, but not a detail of Scripture), remains marginal, notable only for the way Monica Belucci’s beauty stands out in a crowd of despairing onlookers. We catch a glimpse of Jesus coming to her rescue as the religious leaders prepare to stone her, but the scene gives us no details about why they were doing this or what Jesus said that resolved the matter.

There is one monumentally disappointing detail in Gibson’s finished product. It is painful to imagine what might have happened had the music been written by a great composer. When Gibson showed early versions of the film before the soundtrack was finished, he reportedly 'borrowed' tracks from The Last Temptation of Christ's soundtrack music by Peter Gabriel. While Last Temptation was condemned as a blasphemous film by most Christian moviegoers, its soundtrack is a masterpiece, a highly original fusion of differing styles, ancient and contemporary, from several different nations. Now that we have Gibson’s final cut, we discover that composer John Debney (who scored Elf and Jimmy Neutron: Boy Genius) turned in something that sounds like nothing short of musical plagiarism. Those familiar with Gabriel's album Passion, the stand-alone symphony that grew out that 1989 soundtrack, may find themselves frequently distracted. I certainly was. The themes and flourishes here are so similar that some will swear it’s exactly the same music. It would have been fair to credit Gabriel’s influence.

Should You See the Movie?

In the end, while I believe there is greatness in The Passion of the Christ, there are too many heavy-handed choices and/or too many misguided elements for me to call it a masterpiece.

Further, it is hard to know whether or not to recommend the film. To whom do I recommend it?

Believers? These vivid images are clearly Gibson’s version of the Passion. Most Christians would say they have a picture of Christ that has come to them through their own encounters with the text. Some may wish to preserve the version they have imagined while reading the gospels rather than allow these blunt, bloody images to burn indelibly into their minds and replace those intimate, personal images.

Others may want to steer clear — teenagers and adults alike — because it is entirely possible to understand and appreciate Christ’s sacrifice without having to swallow a blow-by-blow account of the destruction of his body. Just as you do not need to see slow-motion video of JFK's head being blown to pieces by a bullet in order to understand what his death meant to the nation, you do not need to see how different kinds of whips tear into Jesus's torso in order to grasp the profundity of his sacrifice.

If your own child were brutally tortured and murdered, would you want a detailed recreation shown to your community to shake them up? Or would you prefer that they meditate on your child's glory in order that their love might deepen?

One Christian critic has already said it is "entirely necessary" for us to see what Christ had to endure. So, what about those many millions who have not had the chance to see it? Is their faith any less strong? Are they deprived in some way? To make such a claim, a person would have to believe that the Scriptures are insufficient. The Great Commission does not include a charge to make sure that people throughout the world hear in graphic detail every kind of torture Jesus may have suffered.

Another has suggested that those who avoid the film because of its violence share the cowardice of the disciples who fled the scene. That is a preposterous claim. Avoiding the film may, for some, be the braver choice, if you want to guard your own personal imaginings of Christ's sufferings, and if you find yourself weakened or injured by violent imagery. Such a charge is like saying that those who refuse to look at images of child pornography are living in denial.

Each viewer will have to decide carefully for himself (or herself). I encourage you not to go to the film out of “Christian peer pressure.” Weigh heavily whether you are prepared, and whether you can maintain a sense of critical discernment to think through what you have seen.

An emotional reaction is not the same thing as being "edified" by a work of art. In order for this work to enrich your spirit, you will need to meditate on it and what it shows us about the One True God.

The Scriptures give us as rich and as rewarding a portrayal of Christ's Passion as we could hope for. They give a few pages to Christ's Passion, but they also explore in great detail his birth, his teachings, his relationships, and something to which this film devotes only a few fleeting seconds... his Resurrection.

-

In the interest of encouraging conversation, here are links to reviews by two other writers I admire and trust. We disagree on some points, but a good debate is healthy.

-

In Aramaic and Latin, with English subtitles. Director - Mel Gibson; writers - Benedict Fitzgerald and Mel Gibson; director of photography - Caleb Deschanel; editor - John Wright; music - John Debney; production designer - Francesco Frigeri; producers - Mel Gibson, Bruce Davey and Stephen McEveety. Icon Productions and Newmarket Films. 120 minutes. Rated R. Starring - Jim Caviezel (Jesus), Monica Bellucci (Magdalen), Hristo Naumov Shopov (Pontius Pilate), Maia Morgenstern (Mary), Francesco De Vito (Peter), Luca Lionello (Judas), Mattia Sbragia (Caiphas), Rosalinda Celentano (Satan), Claudia Gerini (Claudia Procles).

Overstreet's Favorite Recordings: 2005

I'll admit it. I did not keep up with the world of music the way I have in the past. On average, I listened to a new album every week, but the time I'd planned to spend writing about them was swallowed by film-writing assignments and fiction deadlines. It's been a demanding year in so many ways.

Thanks to the vigilance of friends and colleagues like Josh Hurst, Andy Whitman, Thom Jurek, the folks at All-Music Guide and Paste Magazine, I did discover recordings that gave me relief, strength, inspiration, and hope. Some were profound, some just plain fun. And, as always, I want to share them with you. So here is a list of ten albums that made a difference to me.

Overstreet's Favorite Recordings: 2006

About this list:

Once again, I find myself looking forward to hearing a long list of albums that have come highly recommended... but I haven't had the time to give them proper attention. (That's what a full-time job, weekly review-and-column deadlines, and three book deadlines will do to you.)

Superman Returns (2006) - guest reviewer Greg Wright

This is a guest review by Greg Wright

•

Has anyone but me noticed that only one letter prevents Superman Returns from being an anagram for Superman Reruns? Dan Brown is to blame for doing this to my mind.

Before you think I’ve gone entirely off the deep end, though, consider this: The Da Vinci Code postulated that Jesus Christ was not the chaste, virginal young man we read about in The Children’s Bible. Yes, and Ron Howard’s film ratcheted up this daring expose, delivering hard, documented proof that the cinematic Sophie Neveu was indeed the direct descendant of a sexually active Messiah.

And what does all this have to do with Superman Returns? Well, I guess you’ll have to see the movie because I sure wouldn’t want to ruin the precious few surprises in Bryan Singer’s vision of the Man of Steel.

For all intents and purposes, Superman Returns is a paean to a paean. It picks up where Superman II left off, complete with a soundtrack based on John Williams’ score; title lettering inspired by Richard Donner’s Superman title sequence; a Man of Steel modeled on Christopher Reeve; set designs lifted almost wholesale (though digitally) from earlier efforts; and, of course, the same Marlon Brando Jor-El.

Superman’s been gone for five years checking out the old family digs on Krypton, and when the apocalyptic wrecking ball clears things out, he hitches a ride back to earth on the debris. And guess what? Planet Earth, and Metropolis in particular (because, of course, nobody but Americans seem to matter much), is still the same old crime-ridden, dangerous (and very White Male) place it always was. Only LCD panels and the occasional cell phone keep us from thinking that it’s 1983. Clark Kent gets his old job back, and so does Superman.

Lex Luthor gets out of prison, plots get foiled, Superman saves the day and — ahem — gets the girl. (You’ll understand later.)

But if it seems like we’ve seen much of this before, it’s because we have. And it’s because Superman Returns was designed to ensure that we have seen most of it before. Wow, do I feel respected. It’s always comforting, I guess, to know that my next $200 million Whopper will taste just like my last $200 million Whopper.

But seriously — if I want to see a film version of Superman that "gets it right," I can watch the 1978 version, can’t I? If I want to see even more of the same, enthusiasts will tell me that Superman II does the trick, won’t they?

But why are Superman fans so pleased that Bryan Singer was also determined to "get it right"?

I, for one, am tired of the creative drought that "getting it right" apparently demands. So what if getting it right translates into boffo box office? That’s great for the studios, and apparently it’s enjoyable for overly-credulous aficionados and wannabes. But The Goblet of Fire never sold me on the idea that an entire school year had passed while my disbelief was suspended from my cup holder. The Chronicles of Narnia still managed to be an uninspired yawner. The only mystery in The Da Vinci Code was where all the riddle-solving went. X-Men live, X-Men die, and X-Men live again; so how can it possibly matter if they die? Sure, these blockbusters have all been entertaining in their own way, and they delivered what the fan base wanted.

But they were not particularly creative. They were certainly not challenging, either artistically or intellectually.

And I seriously question whether they are worth the hundreds of millions of dollars spent on making them, or the hundreds of millions more that we spend watching them. As a movie critic, I’m starting to find my chosen artistic milieu morally repugnant. Shouldn’t expensive art be great art? Well, at least inspired art, rather than a mere tribute to someone else’s art?

We all remember Bryan Singer’s low-budget sleeper knockout punch, don’t we? Didn’t we all get a thrill out of mimicking a death-rattle "Keyser Soze"? Didn’t Benicio Del Toro, Stephen Baldwin, Gabriel Byrne, and especially Kevin Spacey just surprise the drawers off of us? Weren’t they anything BUT the usual suspects? Great art at a fifth of the cost.

Superman Returns doesn’t deliver five times the punch of that film. Dollar for thrill, it may not even deliver a fifth of the punch.

But fans will be happy. Critics will fawn, and other critics will gripe. The publicity wheels will turn. Sequels will be greenlit. Christians will be oh-so-pleased to champion the Only-Son Savior in Blue Tights who sacrificially brings Light to the World. Never mind that this Superman has an awful lot in common with Dan Brown’s Jesus.

Never mind. Superman returns and saves the day. Hurrah.

Next?

•