Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban (2004)

Thanks to director Alfonso Cuarón and his dream-team of British actors, Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban may mark the first time that the third film in a trilogy has been the best. But thanks to storyteller J.K. Rowling, the derivative plot lacks depth and suspense.

Cuarón is clearly a great choice for the film, bringing with him the talent that made his 1995 film A Little Princess one of the best fairy tales ever filmed. He's got a knack for fantasy. Contrary to the typical Disney sanitization, he allows for the possibility of things to go very wrong, and he's not afraid to let mysteries remain mysterious or dark possibilities remain threatening. Thus, his Potter film is more resonant than the cartoonish, methodical quality of the first two.

Azkaban is richer, more complex, with better performances from its leads. It boasts John Williams's best musical contribution to the franchise. It's also loaded with dazzling special effects that will make the first two films look like cheap made-for-TV affairs.

Most impressively, it features a cast more dazzling than any we're likely to see for a while. Cuarón brings back the spunky Emma Watson as Hermione Granger, of course. And while her presence helps make up for Daniel Radcliffe's unmemorable Harry and Rupert Gint's tiresomely oafish Ron, her increasing ability to steal scenes and enchant the audience may eventually become a real problem for this series. If the Potter franchise is remembered for launching any big stars, I have little doubt that she's the one who will shine brightest in the long term.

Cuarón is also fortunate to have Michael Gambon (Gosford Park, The Insider) step into the shoes of Richard Harris's Albus Dumbledore. Thus, Dumbledore's a rougher, gruffer, more interesting mentor for the children. There's also Alan Rickman as the sour-tempered Snape and Maggie Smith as Professor McGonagall.

But then, Cuarón reveals the new Defense Against the Dark Arts teacher. Replacing the flamboyant Kenneth Branagh in the job is-could it be?-David Thewlis as Professor Lupin! Thewlis, who set fire to the screen with his galvanizing performance in Mike Leigh's Naked, is an inspired choice. He seems more at ease in this environment than any of the cast so far. He doesn't make Lupin a cartoon or a caricature — he's funny, likeable, mysterious, and unpredictable. Lupin starts out training the young wizards to overcome their fears. Later, he gives them reason to fear him. Lupin's complexity makes him the most interesting character in the franchise thus far.

But then, Cuarón reveals the new Defense Against the Dark Arts teacher. Replacing the flamboyant Kenneth Branagh in the job is-could it be?-David Thewlis as Professor Lupin! Thewlis, who set fire to the screen with his galvanizing performance in Mike Leigh's Naked, is an inspired choice. He seems more at ease in this environment than any of the cast so far. He doesn't make Lupin a cartoon or a caricature — he's funny, likeable, mysterious, and unpredictable. Lupin starts out training the young wizards to overcome their fears. Later, he gives them reason to fear him. Lupin's complexity makes him the most interesting character in the franchise thus far.

But wait, there's more. How about Emma Thompson as Professor of Divination Sibyll Trelawney, with glasses that magnify her eyes so they no longer fit her head, and a near-sightedness that messes with her visions of the future? Fantastic. Musing over tea leaves with tremulous melodrama, she's a supernatural flibbertigibbet.

Then, as if showing off, Cuarón pulls off a greater trick. He pulls the long-missing Gary Oldman out of a hat, playing the shadowy figure of the title-an escaped prisoner called Sirius Black. Black has troubling connections to the murder of Harry Potter's parents, and now he seems to have his deadly arts aimed at Harry. When Oldman finally surfaces (disappointingly late in the show), he's not at all what his ‘WANTED' poster has led us to expect. He's, well, Gary Oldman-which means he's a character we've never seen before: complicated, emotional, and full of surprises.

There will be few screen pleasures this year as delightful as seeing Rickman, Thewlis, and Oldman onscreen at the same time, suddenly joined by yet another superlative British talent-Timothy Spall. It's enough to make one wonder if Mike Leigh didn't serve as the film's casting agent. In fact, it makes one a bit sad that it had to be this film that united them. Perhaps seeing three of his former cast members together will inspire Leigh, or someone, to reunite them for something substantial.

Like Leigh's brilliant line of dusty, gritty British films, Cuarón's trip to Rowling's world feels distinctly English. Cinematographer Michael Seresin achieves a naturalism that was lacking in the first two, making Harry's world much more "lived-in" and convincing. The costumes look lived-in as well, thanks to designer Jany Temime. Stuart Craig's brilliant production design gives shadows and history to Hogwarts halls. His gallery of moving paintings becomes something awe-inspiring instead of merely clever. Tim Burke and Roger Guyett's visual effects are masterful, making the Hippogriff-an eagle/horse hybrid-an enchanting and lifelike achievement. It strikes me as rather sad that CGI animation is so frequently used to create the stuff of our nightmares, and so rarely used to invent something beautiful. The Hippogriff soars, buoyed by John Williams's score, a restrained and evocative composition more along the lines of his Catch Me If You Can score than the trademark Williams fanfare of the first two.

You'll notice I'm not saying much about the plot. That's because it's the least interesting aspect of the film. Cuarón has everything he needs for a spectacularly entertaining and exciting fantasy except a suspenseful story. He scares up some goosebumps with a nasty variation on Tolkien's Black Riders, floating black phantoms called Dementors. But otherwise, this is the same plot that carried us through the first two.

Once again, Steve Kloves' failing is not to invest Rowling's story with more heart, more worth caring about. Sure, if he strayed far from her plot, he'd incur the wrath of a zillion fans. But alas, he's thus bound to repeating an unsensational story. The series is thus becoming redundant, predictable, and formulaic.

Here's the formula: Harry begins at the Dursleys, abusing his powers at their expense, for his own amusement. (Ahh, what a role model. Nothing like humiliating a relative to show your budding skills for leadership.) He goes to school, defies authority again and breaks even more rules, gets bullied by other students who also break rules (albeit with a sneer), discovers that his teachers are clueless (again), breaks more rules in order to take care of things on his own, comes face to face with the latest enemy, discovers that he was completely wrong about the enemy's identity, and then humbles everyone by exposing the truth for all to see. What a moral: Crime pays.

Worse, Rowling's story collapses in the last act, spoiling the spooky mood of the film's first 90 minutes by trying to pull the rug out from under us. Just as in the first two films, there must be a last-minute revelation in which exposition is poured over our heads to explain what is really going on. This doesn't seem fair to the audience. The film gave us no indication that we should be looking for clues to solve a mystery, and yet the conclusion behaves as if it has accomplished a brilliant bait-and-switch.

But the thing that bothers me most about this episode in the Potter series is the way that it continues to drain any kind of suspense from Harry's adventures by giving the magicians every variety of spell that they need just when they need it, even though those spells have never been mentioned before.

I groaned aloud when Hermione, who once again proves the smartest and most interesting of the young personalities, pulled a trick out of her hat in the last chapter--a trick that could save the day. Why didn't any of the wizards ever propose using this trick before? Had they considered it in the previous two films, they could have prevented a world of trouble for many of the characters. In fact, if they would use the trick even now, at the end of episode three, they could clean up a great deal of the distress and disorder going on at Hogwarts.

Plot problems like this will continue to make Potter chapters as expendable as episodes of most sci-fi television shows. When trials come up, there will always be a technological tool, or a magic trick, that will save everyone at the last minute. Magic is thus robbed of its symbolic potential and becomes merely a toolbox of technological devices.

With all of its recurring focus on young boys having trouble with their wands, and with the slightly changing dynamic in the relationship between Ron and Hermione, the story is a not-so-subtle drama about coming of age. But it finds nothing interesting to suggest about growing up, except that we must face our fears, blah blah blah. It's far too distracted with tricks and overcrowded with characters who must each make at least one appearance or risk offending the fans. Potentially powerful characters like Professor Snape are reduced to a few scowling cameos. Poor Maggie Smith gets all dressed up and has not but a line or two. When all is said and done, The Prisoner of Azkaban is at heart most concerned about distracting us with red herrings until the arrival a finale that's only surprising because it is arbitrary.

Themes? Acts of sacrifice? Love? No. Potter and Company operate on the principle that all authority is naïve, and that if you want something, you make it happen your own way, no matter how many rules you have to break to get it done. No need to appeal to the wisdom of your elders. Just charge ahead blindly, trusting in your own immature understanding, and the Good Witch Rowling will be there to toss you another trick when you need it.

The next episode will be directed by Mike Newell, who proven his own brilliance with fairy tales in the Irish adventure Into the West. Perhaps he can cast a spell that transforms more than style and technique, elevating story as well.

Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix (2007)

Whether viewers have read the book or not, they'll find no real surprises in Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix.

Director David Yates makes this one of the darker episodes in the series, literally: there are few glimpses of daylight. That serves to accentuate that our rather self-absorbed, disobedient hero, Harry Potter (Daniel Radcliffe), is starting to discover his dark side, like Peter Parker in Spider-Man 3. It also serves to accentuate the lack of humor and whimsy in this installment.

To be fair, the wizardly instructors and their disobedient students are in dire straits this time around, so it makes some sense that this movie would lack some of the juvenile playfulness of the series' early episodes.

Alas, the story just feels too familiar.

Harry's struggle is all too similar to the challenges he's faced before. Voldemort (Ralph Fiennes) wants to do him wrong, and this time he's striking right at Harry's mind. We learn there is a "connection" between the boy and the bad guy, just as Darth Vader could speak directly into Luke Skywalker's thoughts during The Empire Strikes Back. And if Harry allows Voldemort to read and control his mind, all is lost. He'll fall victim to the Dark Side of the Force.

Meanwhile, the grownups are divided. The foolish and gullible leaders of the Ministry of Magic deny that Voldemort has come back, despite the evidence. So they've appointed an enforcer, the prim and proper Dolores Umbridge (Imelda Staunton), to move in and stifle the troubling rumors.

Those adults who are usually trustworthy — Dumbldore (Gambon) and the Hogwarts instructors — are behaving suspiciously (as usual). Kids spy on secret meetings (as usual), decide that they can't leave things to the experts (as usual), and break the rules for the greater good (as usual). Meanwhile, Harry is having horrible nightmares, visions, and flashbacks (as usual). The love triangle of Harry, Ron (Rupert Grint) , and Hermione (Emma Watson) is — gasp — troubled yet again. (When are these three going go start trusting each other? Oh, yes... maybe when they quit breaking rules and become trustworthy.) And it all leads to a wizard showdown (as usual).

It's amazing that, with so much talent and such a colorful story, the film is so lacking in significant developments. It's up to the cast to make this episode feel distinct. Are they up to the task? Well, they do what they can, but we're left watching the young actors do what they usually do, while a cast of great veterans turn in what amount to cameo appearances. This leaves us longing for a movie that would give at least one of them a chance to really shine.

There are only two particularly interesting additions to the cast of characters this time around. We're introduced to the deliciously spooky young woman named Luna Lovelace (Evanna Lynch), whose main accomplishment is to accentuate how bland and uninteresting Harry, Hermione, and Ron have become. And Staunton, as the infuriatingly manipulative Umbridge, is a joy to watch. She'll remind viewers of their least favorite teachers, bosses, Pharisees, and politicians.

It's great to see Gary Oldman getting some screen time, but he's just another character whose whole life seems consumed with what to tell Harry, what not to tell Harry, when to show up and defend Harry, and when to mysteriously disappear.

Severus Snape (Alan Rickman) is his usual morbid self, but he's becoming less and less interesting because everything around him is being sucked into his goth complex, getting darker all the time. (Snape gets one revealing flashback to his youth, but Pixar did this oh so much better with Anton Ego in Ratatouille last month.)

And David Thewlis, who was such a bright spot in The Prisoner of Azkaban, is completely wasted here, sulking as if he's fully aware of this insult to his formidable talents.

Poor Brendan Gleeson is basically reduced to walking around and scowling. Newcomer Helena Bonham Carter certainly looks like she's having fun as a psychotic escapee from prison, but I had to wonder: Is that a costume, or just the kind of thing she's used to wearing in her relationship with Tim Burton?

Maggie Smith does nothing but look distraught.

Hogwarts Headmaster Albus Dumbledore, once the distinguished Gandalf of the series, is left to sneak around in his various bathrobes, until he stops and apologizes for everything (but not the movie) at the end.

For every interesting character, there are several that merely waste our time. The most pointless of all is a big CGI giant who is neither convincing nor amusing nor endearing (and he's meant to be all three).

Young Cho serves no purpose other than to give Harry an excuse for a first kiss; it's quite obvious that this love story isn't going anywhere, because once that's done he dashes off to take care of business and the story leaves her behind.

Voldemort's kept a low profile through the whole series. His dazzling arrival at the end of the last installment was almost a relief. And so, what does he do now that he's loose? Well... he keeps a low profile.

And when the heroes are put on trial for claiming that Voldemort did return, we share their exasperation, because it feels like the jury, the government, and the news media are simply holding up the storytelling by feigning ignorance.

To make matters worse, the film has been so heavily edited that a lot of things don't make sense. Phoenix is the longest book in the series so far, and this is the shortest film. Not a good thing.

Forgettable, poorly explained episodes abound:

- What's the point of the chapter with Hagrid and the Annoying CGI Giant? Later, the giant has disappeared, and we're not given sufficient information about why.

- One character gets captured by sinister centaurs, and then show up later back at Hogwarts with hardly a scratch and no tales to tell.

- A good deal of energy is spent worrying us about whether or not Emma Thompson's Professor McGonnagle will be exiled from Hogwarts, and the whole matter is resolved by one character showing up and saying, "No, she stays." Wow.

- And what the heck is that mysterious arch that swallows up one of the film's main characters? The scene borrows heavily from the loss of Gandalf in The Fellowship of the Ring, but we can't even tell if what we're watching is a death or a disappearance. We don't know where we are, what's happening, or why. Those are rather crucial elements in storytelling.

And it's becoming rather annoying to consider how spells they've used in previous situations are conveniently forgotten when they might come in handy and actually solve a problem or two. (Weren't they able to time-travel a couple of episodes ago? Wouldn't one good time-travel flourish help them undo mistakes made here?

The film's implications perpetuate the series' worst habits.

For once it might be good if the heroes actually got punished, instead of rewarded, for behaving as if all rules were made to be broken. How many parents spend their time trying to instill some decent guidelines in their children? How can they compete with a series that relentlessly portrays impetuous youth as the truly wise while the loving caring grownups just don't get it and end up apologizing at the end?

The longer the series goes, the more I wish the other characters would develop lives of their own. So many of them are so much more interesting than Harry. I wonder what kind of effect the Potter franchise has on young imaginations which tend to be self-centered anyway. Are the stories reinforcing the idea that we're here on earth to defy the rules until we get our own personal curiosities answered? Are they giving readers, who will naturally associate themselves with the hero, the sense that the world revolves around them?

I think the healthiest thing for Harry right about now, and for the series as a whole, would be to discover a story that shows there's more to life than Harry's own family crisis.

Elliott Spitzer Makes a Porno, Part II; Also: Christian Approach to Movies

Laura Bramon Good delivers Part 2 of her series "Elliot Spitzer Makes a Porno" ... at Image's blog, Good Letters. (If you missed Part 1, it's here.)

-

Greg Wright on "Anatomy of a Christian Approach to Movies" (Hey, thanks, Greg! I'm honored!)

Must-read: Laura Miller on Twilight

Well, I've run out of time to deliver the review of Twilight I'd hoped to write this weekend. Too busy working on the third book of The Auralia Thread, and we had our Thanksgiving dinner a week early, thanks to a visit from my parents.

But that's okay, because I've got something much better for you than my disgruntled perspective on the film. The best thing I've read on the appeal of Stephenie Meyer's Twilight is Laura Miller's article in Salon. It is a brilliant interpretation and diagnosis. And very well written.

Read all two pages of it here. It makes a lot of sense. And it's kind of scary.

Scarier than the movie, anyway.

Why "Twilight" the movie is better than the book

Perhaps the best thing about the release of the movie Twilight is that the Internet is already abundant with Twilight-related comedy.

One of the most amusing exhibits so far: A slideshow of 28 Reasons That Twilight the Movie is Better Than the Book.

Perhaps the best thing about the release of the movie Twilight is that the Internet is already abundant with Twilight-related comedy.

One of the most amusing exhibits so far: A slideshow of 28 Reasons That Twilight the Movie is Better Than the Book.

Meanwhile, Jeffrey Wells writes:

Read more

Limited-time Christmas gift offer

Planning to give copies of Cyndere's Midnight and Auralia's Colors for Christmas gifts? Here's a bonus.

Read more

Know anybody in Bellingham, Washington?

Tonight at 7 p.m.,

I'll be reading from Auralia's Colors and Cyndere's Midnight at Village Books in Bellingham, Washington.

Know anybody in Bellingham? Tell them to come to the reading! I'll be signing copies for Christmas gifts and passing out free posters to anybody who wants one.

"Twilight" review coming this weekend...

UPDATE: An alternate script for Twilight.

Yes, I've seen Twilight.

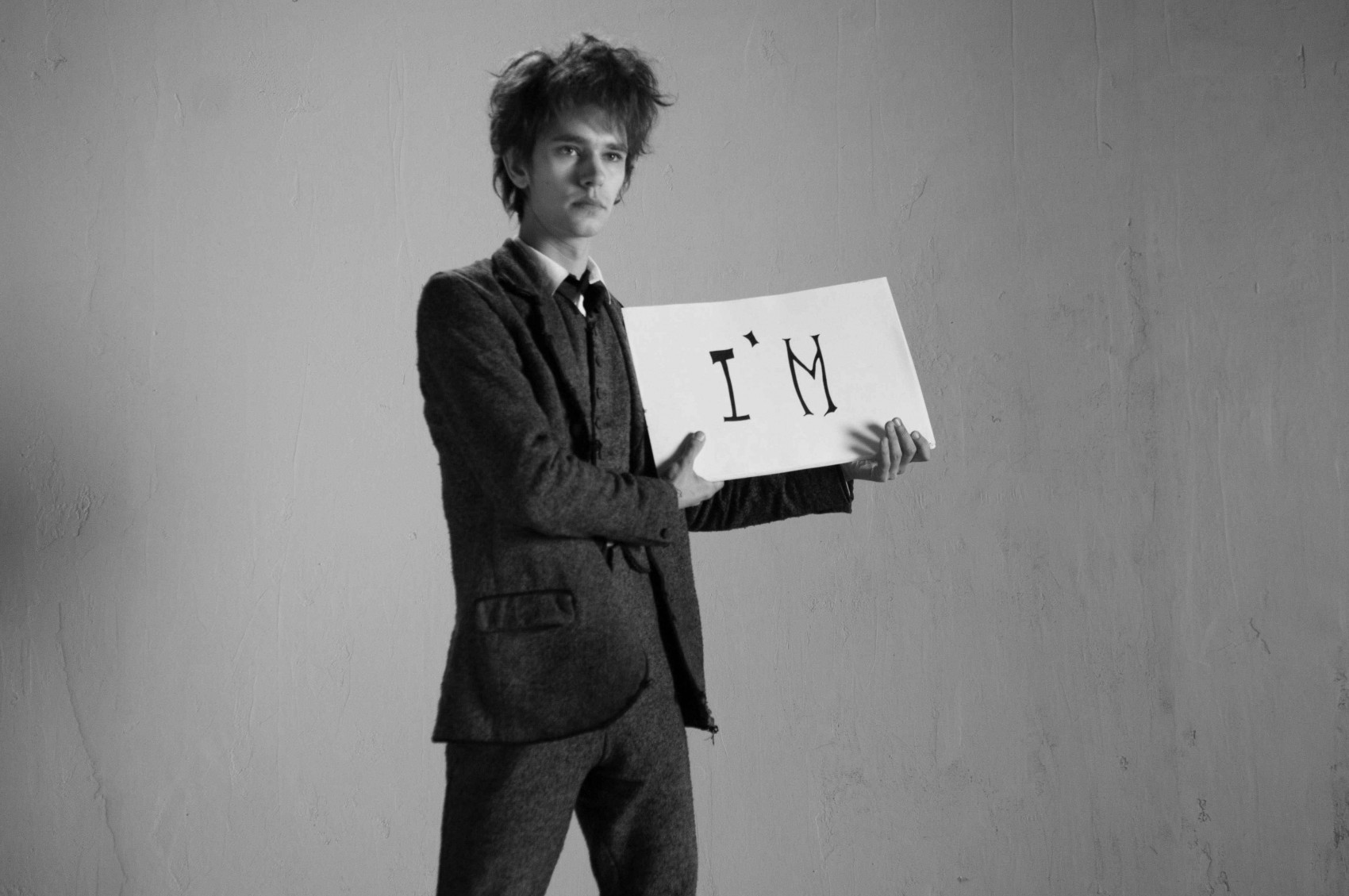

I'm Not There (2007)

[This review was originally published at Christianity Today.]

•

If you want to inspire a challenging discussion about art and culture, try this: Watch Martin Scorsese's excellent 2006 documentary No Direction Home: Bob Dylan, and discuss it. Then, reconvene a week later for a viewing of Todd Haynes' surreal new movie I'm Not There. Their differing, complimentary portraits of Bob Dylan will give you so much material to ponder and discuss, you won't know where to begin.

To study Dylan's career is to ponder provocative questions about poetry, politics, music, politics, celebrity, spirituality, and American history. It is beyond dispute that he's an artist of skill, imagination, and vision. But he is also as human as the rest of us, a man whose missteps have been almost as spectacular as his successes.

A dictionary full of words have fallen short of describing him. He's been a rebel, a prophet, a poet … even "Judas." He's almost too big for a movie. But Haynes' film emphasizes the fact that Dylan escapes all attempts to define and explain him. Taking up a few (but only a few) strands of Dylan's career, Haynes braids them together. It's a complicated weave of periods, styles, and facets of Dylan's personality.

Experiencing Haynes' ambitious vision is a little like trying to tour the Grand Canyon in two hours. The movie's whirlwind of information and ideas is both exhilarating and ultimately exhausting. Still, how often do we have this problem—a movie that gives us too much of a good thing?

Haynes tracks Dylan's emergence as a freewheelin' folk-singer fond of Woody Guthrie; his rise as a political poet of the '60s; the troubles of his personal life; his flight from exploitation; all the way to recent years, where he's become something of a recluse and a wanderer, traveling through the backwoods of American music.

Dylan's career—both onstage and off—has reminded us that poetry can convey what more didactic forms of communication cannot. His genius can be found when we examine what he has written and sung, and how his metaphors grow from—and speak back to—his audience, culture, country, and times. But, contrary to what the American people have believed, that is where it stops. When we look at Dylan himself in hopes of revelation, we're in trouble, and he knows that.

But poetry is a language that must be learned, and most of those seeking to define, categorize, and exploit the Artist are not fluent in poetry. In fact, Dylan's songs contain some of his most scathing rebukes, making fools of those who try to pin him down, even as they pat themselves on the back for trying.

To cope with those who would seek to box him in, Dylan has become an exemplary shapeshifter, answering his interrogators with jokes and riddles, always aware that a direct answer — should he ever attempt one — will be misunderstood, unraveled, and remade into a noose. And he devoutly refuses to follow any guidance but the artistic impulse, which is a still, small voice. An artist devoted to his muse is a moving target—a "rolling stone."

Haynes has no desire to "solve" Dylan. So he casts several actors as differing manifestations of the mystery. These characters resemble Dylan. Haynes never once mentions Dylan's name, giving each "version" his (or her) own character. Each is a living, breathing metaphor, exposing differing aspects of a complex man. (One of them, in a fictional flourish, even dies of a drug overdose. We're invited to the autopsy.)

The film begins with Marcus Carl Franklin as Woody, the 11-year-old African-American version of the Artist — no, I'm not making that up. As he confesses to a couple of admiring hobos in a boxcar, "I don't know who I am most of the time." It's as if he's channeling a who's-who of American bards and poets, from Whitman to Guthrie, while his own identity remains elusive.

Personifying the Artist cornered by the persistently oblivious reporters, Arthur (Ben Wishaw) answers questions with wry, weary retorts, quoting directly from Dylan's library of challenging (some would say "cryptic") interviews.

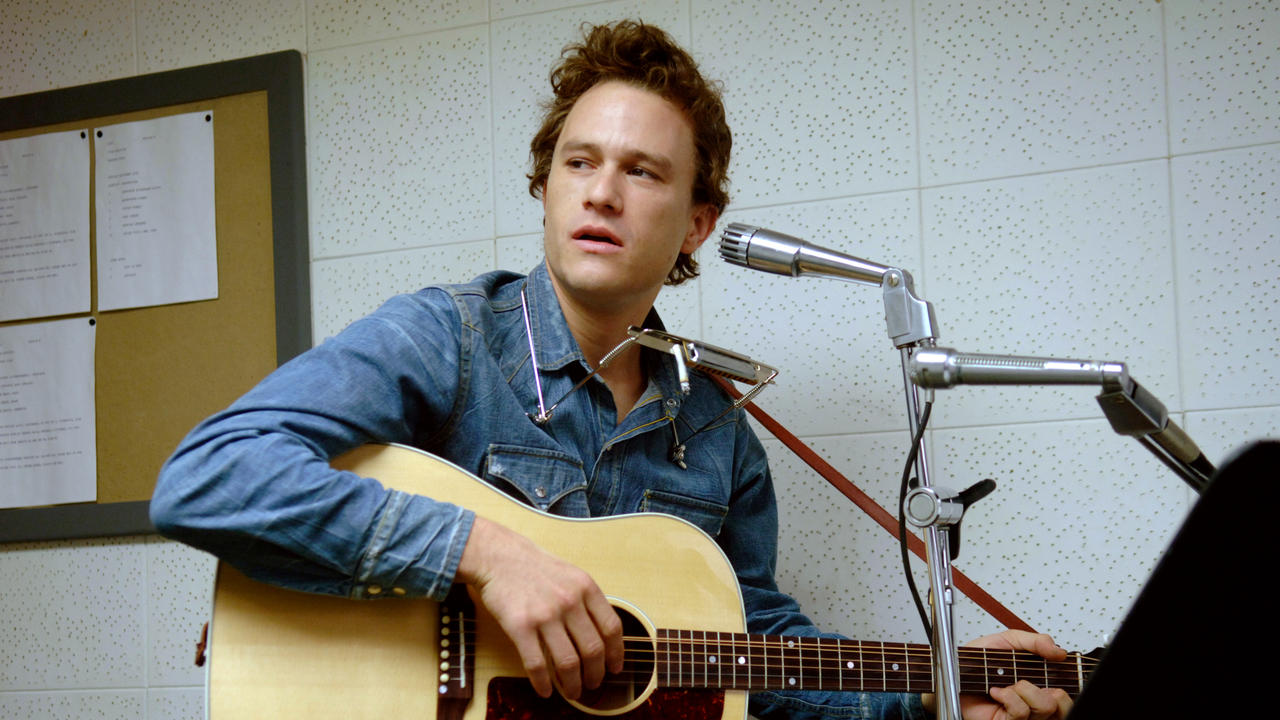

Christian Bale plays Jack Rollins, a rising star in the folk music world, soon to be cursed with the title "Voice of a Generation." When Jack Rollins opens his mouth to let the vocals of rocker Stephen Malkmus ring out, most viewers will be oblivious to Bale's perfect lip-synch. It's too bad Bale's exceptional performance will be overshadowed by the showier performance that comes next.

Later, Bale will return as the Artist who fled from the spotlight into the comforts of 1970s evangelical Christianity, and became "Pastor John." But even the church let him down, becoming another stifling community eager to exploit him as a model of musical missionary work. (If any chapter of Dylan's career gets short shrift here, it's this one.)

In the film's most talked-about bit of "stunt casting," Cate Blanchett plays Jude Quinn, resembling the mid-'60s Dylan. It's a brilliant move—Blanchett's uncanny performance shows us how Dylan's public persona became an extension of his art, full of riddles, metaphor, evasion, and comedy. This is the Dylan of Don't Look Back, who evolved in ways that upset fans who wanted to claim him as their political or cultural representative.

When Quinn gets onstage at a folk revival, plugs in electric guitars, and growls "I ain't gonna work on Maggie's farm no more," it's clear that he's chasing his vision no matter what the cost. The audience, feeling betrayed, hurt, and outraged, walks away convinced that their hero has sold out. One fan staggers away, profoundly observing, "He's not like he was."

In one memorable moment, Quinn and Alan Ginsberg (David Cross) clown around in front of a statue of Christ on the cross. But they're not being sacrilegious. They're mimicking the ridiculous cries of the masses, who misunderstand Dylan the way Christ's audience misunderstood him. Elsewhere, in a sequence as surreal as a music video, Quinn sneers and spits out a performance of "Mr. Jones," staring laser beams into the arrogant, condescending BBC journalist who persecutes him.

Heath Ledger plays Robbie, a singer striving to turn his musical success into a legend-making Hollywood breakthrough. Robbie's scenes offer interpretations of Dylan's personal relationships, marriage, fatherhood, and heartbreak. Acting like the heir-apparent to James Dean's rebel throne, he loses touch with his beloved Claire (Charlotte Gainsbourg), who is also the mother of his children. Ledger is impressive, but Gainsbourg almost steals the movie as the woman who cannot hold on to the locomotive she has married.

Finally, Richard Gere is the reclusive "Mr. B," a retired Billy the Kid on the run from lawmen with grudges. In this, the most fanciful thread, the Artist retreats from fame and celebrity only to find that the Enemy has grown too powerful, laying waste to the wilderness where he's been trying to hide. In the town of Halloween—part wild west movie set, part circus—a villainous lawman confronts the Artist again, and he has a familiar face.

I'm Not There also boasts some memorable supporting turns. Julianne Moore plays the equivalent of Joan Baez, hilariously pretentious as she recounts her memories. Bruce Greenwood is brilliant as the manifestations of the Enemy, most of them condescending, arrogant journalists. And David Cross is hilarious as Alan Ginsberg.

Haynes' kaleidoscopic style packs in so many clever references to Dylan trivia that longtime fans will nod, gasp, and laugh out loud. (Do you know what that tarantula represents?) Those who only know a handful of Dylan songs may wonder what's fact, what's fiction, and why it matters. Aesthetically, Haynes references Dylan's own big screen ventures, like Don't Look Back and Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid, as well as films that Dylan apparently admired, like 8½. Much of the dialogue is drawn straight from interviews, live footage, and Dylan's own cinematic projects (the good and the bad).

Instead of aiming to please with a soundtrack full of hits, Haynes makes surprising selections from the Dylan catalog. Sure, "Like a Rolling Stone" gets prominent play, but a track from the official Dylan Bootleg collection—"Blind Willie McTell"—brings out beauty and soul in one of the film's more moving passages. Other masterful songs like "It's Not Dark Yet" and "Man in the Long Black Coat" are used more like traditional soundtrack music, more for mood than meaning.

It feels like the movie toward which Haynes has been building all along. Haynes' first movie project was co-authoring Superstar, a Super-8 version of the Karen Carpenter story starring Barbie dolls. He also made Velvet Goldmine, both a tribute to, and an evisceration of, the glam-rock era, with Jonathan Rhys Meyers as a David Bowie figure. He also proved his talent for resurrecting bygone eras with the remarkable homage to the 1950s films of Douglas Sirk, Far From Heaven, which was so obsessed with replicating Sirk's style that it toed the line of satire.

And yet, it may be that Haynes released the film too early. There's a 90-minute masterpiece in this film, waiting for an editor to find it. Had Haynes been braver and cut some of the good stuff to make the best parts even better, we would have walked out overwhelmed and delighted. But at 135 minutes, I'm Not There makes viewers feel like they're being sent back to the table for seconds, thirds, and more, long after they had their fill. Near the end, we're left guessing just which Dylan will have the last word.

But in the larger scheme of things, the last word on Dylan will never be spoken. And we can be grateful for that.

The Insider (1999)

'Tis the season to toss aside what other people think of you, do what you feel, and devil-may-care who gets hurt in the process.

At least, that's what the movies will tell you.

The leading men onscreen this season (Lester Birnam of American Beauty, Tyler Durden and "Jack" of Fight Club, Craig and Lottie of Being John Malkovich) are not generous people. They are not humble. They're not the kind of people to give up their own dreams for the good of others. They're distinctly American — "I have a right to pursue my own happiness my desires, and you’d better not get in my way."

The Insider couldn't come at a better time. 1999 finally has a movie where men have bigger things on their minds than just making themselves happy. And those heroes are Jeffrey Wigand, who gave the press the evidence that Big Tobacco was intentionally making cigarettes addictive, and Lowell Bergman, the producer with the guts to put his career on the line and run the story.

After I caught a screening, a friend of mine asked, "What on earth makes The Insider interesting? What drew that powerful cast to such a mundane, already-worked-over subject." Good question. Haven't we had enough Oliver-Stone-esque movies about conspiracies and corporate dishonesty? It was in the newspapers just two years ago... why bother re-living it in a movie?

But Michael Mann's 157-minute Event Movie is much more than an exploration of a media scandal. Mann found a story about a drama relevant to all of us: Trust between friends during times of hardship. This is a war movie. The big strikes are lawsuits. The battlefields are men's consciences. And the heroes are putting themselves on the front lines for the sake of telling the truth. The casualties? Integrity and reputation. Family. Lifestyle. Futures and dreams.

Some bicker about this movie's deviations from historical detail, but since I can't ever know what really happened I'm more concerned about storytelling (see footnote*). In this telling of the story, Jeffrey Wigand is fired from his job as a scientist for Big Tobacco when he refuses to participate in a cover-up of unethical practices. He walks away from his job, hoping to put it behind him. But his conscience is not silent, and he attempts to bring his story to the press. His former employers are watching, and they mean to hold him accountable to a confidentiality agreement. When he slyly moves outside the territory of the agreement, they get nasty. And dangerous.

It may be glamour and glory that draws Lowell Bergman to Jeffrey Wigand's predicament in the first place, but soon he learns that a man’s mind, heart, and home are at risk here. Fortunately, Bergman is a man of some conscience; he isn't going to use Wigand as a source and then abandon him to his miserable fate.

Bergman is Wigand's hope of making something good out of a bad situation. And so the two become friends as they prepare a story for Mike Wallace to run on 60 Minutes. But when Big Tobacco threatens 60 Minutes, and it looks like Wigand is suffering for a lost cause, Bergman digs in his heels and things get really interesting.

No actors could have brought more passion to the lead roles of this film. Al Pacino is at his very best as Bergman. He's remarkably restrained, but when the CBS executives begin to cut ties to him and his efforts to expose Big Tobacco's lies, he summons up that high-caliber rage that perhaps only DeNiro could have matched. His energy is the adrenalin of the movie.

And Russell Crowe's turn as Jeffrey Wigand is the movie's sweat and blood. Crowe continues to outdo himself on screen. Hold this performance up to his work in L.A. Confidential, Mystery, Alaska, or The Quick and the Dead, and you won't believe it's the same man. Watching him here is like watching the wax melt on a candle, as Wigand slowly crumbles under the pressure of his moral dilemmas. He moves from being a suit to being a vulnerable, traumatized human being, staring out at the ocean as though waiting for an answer from God.

In the heated confrontations and in the explosive boardroom debates, Christopher Plummer comes close to stealing the movie. Plummer portrays 60 Minutes’ Mike Wallace as a fearless investigative reporter — he’s as unafraid to challenge a Middle Eastern warlord during an interview as he is to stand up to his corporate bosses and remind them that he's what brings them good ratings.

All three of these guys deserve Oscars when March gets here.

Michael Mann knows the talent he's got in front of him. He employs the most daring use of close-ups I've seen since the films of Krzystof Kieslowski. He pans across the faces of these beleaguered warriors the way Spielberg's camera takes in battlefields in Saving Private Ryan. Cinematographer Spinotti frequently guides the camera around the back of his actor's heads, and then zooms in slowly to that place at the base of the skull where tension collects. You get the feeling that all of these suffering souls need a good neck massage to help relieve the stress.

By literally looking over the shoulders of Wigand and Bergman, we are unable to escape wondering what we would do if we were in their shoes. Would we compromise? Would we shut up when threatened? Or would we put our family members up to be sacrificed on the altar of truth, and watch as all the sordid bits of our past brought out on the evening news in a smear campaign?

Mann alternates pregnant pauses with sequences of swift exhilarating action. He makes a legal deposition and a cell-phone conversation as intense as the brilliant shootout he choreographed in his cops-and-robbers classic Heat. It made 2 ½ hours of hushed conversations feel like a 90-minute action movie.

What a moviegoing season it is! Such originality, and so many great performances! But among such memorable films, we have one that excels beyond technique, and that urges us on to more than just serving ourselves. The Insider is a movie that's worth a full-price ticket. I had read the papers. I knew the story. And yet this film moved, exhausted, and inspired me. That's more than any about any other film I've seen in the last six months.

Footnote:

*A recent New York Times article ran an update that claimed the film's portrayal of Mike Wallace's involvement is fairly accurate, except at one point in the film Wallace is goaded to make the right choice, where he still claims he made the right choice to begin with.