Through a Screen Darkly - Bonus Commentary - Does the Media Have an Anti-Christian Bias?

A bonus commentary for readers of Through a Screen Darkly.

•

Yes, I do grow weary of the relentless portrayals of Christians as brainless idiots on the big screen. And those who are eager to dismiss Christianity will happily embrace these portrayals as some kind of verification that our faith is empty.

When I encounter people who point to Christian foolishness as evidence that faith is misguided, I've reminded them that many of their favorite movies show the redemptive influence of faith on broken people. While Hollywood's satires and send-ups sometimes speak the painful truth, there have been quite a few movies that offer dignified portrayals of Christians.

Here are a few titles that show faith in a truthful and positive light: Dead Man Walking, Ordet, Chariots of Fire, The Apostle, Magnolia, A Walk to Remember, The Year of Living Dangerously, Vanya on 42nd Street, Diary of a Country Priest, Shadowlands, Ben-Hur, A Man for All Seasons, A River Runs Through It, The Hiding Place, The Sound of Music, The Elephant Man, The Robe, Brother Sun Sister Moon, Molokai, Places in the Heart, Sergeant York, A Cry in the Dark, Tender Mercies, Le Chambon, Italian for Beginners, You Can Count on Me, The Mission, Les Miserables, Chelsea Walls, X2: X-Men United, and Signs.

Still, it's unlikely that a society intent upon laughing at others, rather than themselves, is going to go out of its way to apprehend the integrity of Christian faith. Most skeptics prefer conspiracy theories and blended heresies like The Da Vinci Code to reinforce their prejudice.

But prejudice is not the primary reason we continually see Christians made into a laughing stock.

The mainstream media is made up of businesses. Most business people aim to make money. The media makes money by pursuing high ratings. And here are some surefire ways to earn ratings:

* Expose a hypocrite. Crowds love to see a proud man fall.

* Show something controversial. Crowds love a scandal.

* Broadcast an extremist behaving outrageously. Crowds love people who embarrass themselves.

* Turn two extremists against each other — crowds love a fight.

Thus, when the mainstream media looks for a representative of Christians, or any particular community, they often go looking for someone whose views are extreme enough to qualify as great, profitable entertainment.

* * *

Recently, I was working at my desk at Seattle Pacific University when I received a phone call from a woman who works for one of the three major news networks. She informed me that she had heard I was a Christian movie reviewer with a sizable readership. They wanted to pick me up, drive me downtown, and put me on camera for a special report on a TV news program.

This was the question of the day: Is the media anti-religious?

My first thought was, of course, "Give me an hour. I need to change into some nicer clothes." But then I started preparing my notes and pondering what I would say.

Here was the basic idea of my planned reply:

When I say "the media," I am aware that I'm using a gross generalization, like "Hollywood" or "Democrats" or "Republicans." Thus, there will be exceptions to my answer.

Having said that, it is my opinion that the mainstream media tends to go with whatever will be the most arresting story. Thus, they often go for extreme voices instead of something closer to the truth. We end up watching a lot of interviews and reports in which religious people say and do extreme and terrible things, because that's interesting. That's unexpected. That's exciting.

But you get the same thing in the religious press ... religious voices speaking in extreme, attention-grabbing, self-righteous terms about the non-religious. We set up straw men, and we knock them down. It's dramatic and engaging, but it's not terribly challenging.

It would be a healthy change for everyone if audiences were exposed to those intelligent, moderate, insightful people who are widely respected by the Christian community. There are many who could contribute to an engaging and balanced dialogue without resorting to inflammatory language or stone-throwing.

But intelligence does not earn big ratings. Sensational spectacles are what win viewers, and thus we're not likely to see businesses flocking to portray Christians - or any particular interest group for that matter — fairly.

Satisfied with my rough-draft answer to the question, I waited for the phone to ring with the details for my transportation.

And the phone did ring. But before I could offer my answer to the woman, she said to me, with profuse apologies, that the network had decided my opinions were not "extreme enough."

They had looked at my Web site and realized I wasn't going to offer an impassioned, defensive, outraged, anti-media response. They were looking for a Christian who would.

She added, "Off the record, I just want to say that this pretty much guarantees our program will have nothing of value to say on the matter."

I can't think of a punchline good enough to end this story.

Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds - Abattoir Blues / The Lyre of Orpheus

In the Bible of contemporary gospel music, Nick Cave’s new pair of albums prove he’s a Major Prophet.

Like David Eugene Edwards (of Sixteen Horsepower and Woven Hand), Cave’s brutal honesty, surreal symbolism, zeal for the sublime, and righteous anger at himself and the reset of humanity sets him up as one of rock and roll’s equivalents to John the Baptist crying in the wilderness, making way for the return of the Lord even as he decries those who claim to speak for God.

Cave embraces his role as a hellfire-and-brimstone poet of the weeds and the wilderness on these simultaneous releases—Abattoir Blues and The Lyre of Orpheus. Pondering the cost of war, the greed of superpowers, selfishness disguised as love, lies dressed up as patriotism, and the parlance of religion employed for sinister purposes, Cave’s songs could not be more timely. And they have never arrived with such force. After 2003’s disappointing album Nocturama, in which it sounded like Cave’s musical well had run dry, Abattoir Blues and The Lyre of Orpheus represent a flood of new creativity and energy for Cave. These are the most creative works of his career, some of them stand among the loudest and angriest, and a handful are the closest thing to “beautiful” he’s ever composed. The albums will likely stand the test of time as the pinnacles of his long, dark, strange career, unless he finds some way to go farther on this new surge of vision.

Strangely enough, he accomplishes this in the absence of his longtime guitarist, the Bad Seeds’ Blixa Bargeld. In the open space that remains without Bargeld’s bold, caustic chords, Cave decorates his songs with everything from flutes to gospel choirs, from Jews harps to string sections. The result is a sound as full and forceful as anything on U2’s latest effort. Musically, each album is a furnace unto itself, roaring with fiery guitars and trembling with the force of a Spirit-filled congregation that can actually the judgment coming over the horizon.

The lyrics of both records are steeped in the blood of history’s war crimes, as this self-deprecating preacher stands in awe of beauty and love even as he sees those very gifts flying like a flag over the exploits of warmongers and devils.

For all of U2’s conscience-burdened lines about Western greed on How to Dismantle an Atomic Bomb, Cave comes up with the year’s most pointed (and self-damning) lyric about the problem, snarling snidely, "The sky is on fire, the dead are heaped across the land, / I woke up this morning with a Frappucino in my hand." That’s just one of many lines barbed enough to provoke both a wry smile and a wince of shame or regret.

Abattoir Blues begins with “Get Ready For Love,” in which the Bad Seeds rock as if their lives depend on it. It’s a fiery song of Gospel promise, as Christ comes charging down from the heavens on what sounds more like a freight train than a chariot, bringing the kind of love that should make us tremble and beg for mercy. Cave is at once mocking the hypocrisy and empty emotionalism of contemporary religion ("Praise him 'til you've forgotten what you're praising him for") and reminding us that God’s work is going on in ways we fail to understand: “The miracle of his promise creeps quietly by.” He seems to be stuck in a conundrum: Why should we love God? But then again, why should God love us? Cave sings with such fury that, if this were alive show, you’d expect to see the folks in the front row heading for the exits or the back wall.

“Cannibal's Hymn” places us in the perspective of a singer who is full of zeal to save a beautiful woman’s soul; but as he beguiles her with promises of salvation and damns “those heathens you hang with,” it’s clear that he’s plotting his own form of conquest. Deeply unsettling in this day of church sex scandals and evangelism styled as propaganda.

“Hidin’ All the Way” is sung by an elusive desire, escaping those who seek it (Him?) in earthly things. The singer assures the listener that, although their search will continue, they know in their hearts what the law is about.

You searched through all my poets

From Sappho through to Auden

I saw the book fall from your hands

As you slowly died of boredom

I had been there, dear,

but I was not there anymore

I had been there, now I'm hiding all way.

But there's a suggestiono that the search won't last forever, as the song builds to an earth-shaking declaration that “THERE IS A WAR COMING!”

In “Messiah Ward,” the victims of wars we wage for pride and selfishness are paraded before the people responsible, and they are encouraged to look the other way. The person in charge is glad to have your support, but he's also conveniently working outside of any familiar moral framework.

We could navigate out position by the stars

But they've taken out the stars

The stars have all gone

I'm glad you've come along

We could comprehend our

condition by the moon

But they've ordered the the moon not to shine

Still, I 'm glad you've come along

I was worried out of my mind

Cause, they keep bringing out the dead

It's easy just to look away

They're bringing out the dead, now

And it's been a long, strange day

This is a war song, clearly, taking place in a day long after Bob Dylan’s fears of a world in which "we're breaking down the distance between right and wrong (Oh Mercy's “Ring Them Bells”).

The album’s high point, “There She Goes, My Beautiful World,” dwells on the elusive beauty of the world, something he can only clumsily try to capture in words. Bemoaning his writer's block, he sings,

John Willmot penned his poetry

riddled with the pox

Nabakov wrote on index cards,

at a lectem, in his socks

St. John of the Cross did his best stuff

imprisoned in a box

And JohnnyThunders was half alive

when he wrote Chinese Rocks

Well, me, I'm lying here, with nothing in my ears ...

Send that stuff on down to me

Unable to conjure the language, or even a vision, he makes up for it by expressing his despair at the decline of the world that he loves by revving the motors of his gospel choir engines until they smoke.

“Nature Boy” comes on like gangbusters, like a U2 hit, delving into the darkness of human behavior (“some ordinary slaughter, I saw some routine atrocity") in contrast to the glory of God revealed in nature’s beauty. Its chorus echoes U2’s “Mysterious Ways,” trying to apprehend the Spirit as it moves: “She moves among the sparrows / and she moves among the trees / and she moves among the flows / and she moves something deep inside of me…”

“Abattoir Blues” gives us more views of the world disintegrating for lack of a moral code. Cave finds lovers “entwined together in this cultural of death,” while the singer’s heart has “tumbled like the stock exchange,” his “need for validation gone completely berserk.” He laments to his beloved, "I wanted to be your Superman but I turned out such a jerk." The song focuses on our foolishness and pride, and what it costs the rest of the world. The ladies chanting “a-ba-ttoir bluuuues” sound like the spooky soul sisters of the recent Leonard Cohen albums.

The albums explodes into Cave’s most glorious and sincere expression of worship in “Let the Bells Ring,” which features warbling guitar lines that beg for The Edge to show up and throw down a euphoria-inducing solo.

Cave calls directly to Christ in this song, the most straightforward in the whole collection, and testifies:

There are those of us not fit to tie

The laces of your shoes

Must remain behind to testify

Through an elementary blues

So, let's walk outside, the hour is late

Through your crumbs and scattered shells

Where the awed and the mediocre wait

Barely fit to ring the bells.

That would be a profound finale, capping the most powerful gospel album of the year. But Cave turns things dark and nasty instead with “The Fable of the Brown Ape,” in which it seems all of this rejoicing has split the seams of the earth and darkness is seeping out. It’s a subversive fable in which a farmer shows kindness and mercy to a serpent by feeding it “the milk of human kindness” until the villagers descend upon the farm in outrage. The brown ape, a witness to this violence, escapes and spends his days rattling his chains and singing about what he's seen. Does the ape represent the artist, trying to justify the ways of the Farmer to man? Does the snake represent the devil, which God allows to torment his creation? Or does he in some way represent humanity, the undeserving wretches who have been given grace by a compassionate authority?

The Lyre of Orpheus steps out of religious terminology and into the language of mythology, where lovestruck Orpheus employs his music in a quest to save Eurydice from the clutches of evil.

In the title track, Orpheus plays till his fingers bleed, but his music turns out to be less than appreciated. When he plays, “Bunnies dash their brains out on the trees.” Hearing the music, God awakes from a deep deep sleep (“God was a major player in heaven”) and throws a hammer at Orpheus’s head, knocking him down a well (to, of course, the plays that rhymes with “well.”) Having arrived in the fiery furnace, Orpheus finds his beloved Eurydice uninterested in his musical salvation. “Dear Orpheus, if you play that f----n’ thing down here / I’ll shove it up your oriface,” she snarls. Miserable, Orpheus stares into the abyss and says, “This one is for mama.”

The singer of “Breathless” basks in natural beauty that inspires him, even if he doesn’t believe his artistic responses will do any good. Flutes, acoustic guitars, and a sing-along chorus combine to exalt the Lord, the very One celebrated by the wind, the trees, the blood in his veins, the robins, the foxes, the rabbits—and even the fishes who jump up to take a look at nature from “the bubbling brook.” The singer sees suggestions of his Creator in this natural beauty: “Your face comes shining through … and I am breathless without you.”

In a mournful song for a dying world, “Babe, You Turn Me On,” Cave entangles affirmations of creation’s glory with admissions of its wickedness, as if the two are almost inseparable. He sings about the pointless savagery of the butcher bird, and how the song of the nightingale “raises up the ante.” With one hand he holds his lover’s arm, even as he gropes her crassly with the other, the music percolating cheerfully all along the way, sharpening the song’s dissonant thoughts. “You almost have leapt into the abyss,” he observes, “but found it only comes up to your knees.” Having given ourselves over to darkness, we find we cannot escape the painful reminder of the glories we are destroying. Again, he characterizes himself as an ape in pursuit of beauty: "I move stealthily from tree to tree / I shadow you for hours / I make like I'm a little deer / Grazing on the flowers." And again he observes, "Everything is collapsing / All moral sense is gone. / It’s just history repeating itself ... Crimson snow falls all about, carpeting the ground / Because everything is fallen, dear/ all rhyme and reason gone…”

“Easy Money” may be the most troubling song of all. The singer describes how difficult it is to come by the comforts cash affords, and prays for money the way drought-damned farmers pray for rain. When the singer shares these complaints with another man, the man responds with an expression of sympathy that quickly becomes an aggressive sexual advance.

In “Supernaturally,” Cave returns to full-volume rock and roll, describing his bleak existence stranded with the Eskimos, polar bears and penguins, “hunkered by the fire, knuckles dragging through the mire.” Describing himself once again as an ape, he’s begging for a truce, for peace, for something that once fulfilled him that is now drifting away. That something may very likely be his country, his fellow human beings, who are going against nature ("super naturally"). He sings:

You're my north, my south, my east, my west

You are the girl that I love best

With an army of tanks bursting from your chest

I wave my little white flag at thee

Can you see it, babe?

This thunderstorm is followed by a quiet and meditative expression of his resilient hope, "Spell," in which he determinedly intones:

The disc closes with a pair of hymn-like meditations, complete with a choral backdrop.

“Carry Me” is a waltz with a desperate prayer at its heart:

Who will lay down their hammer?

Who will put up their sword?

And pause to see

The mystery

Of the Word

As in Abattoir Blues, Cave cannot allow himself in good conscience to end on a note of exaltation. He collapses once again into the horrors of human behavior, echoing God’s own lament in “O Children,” a prayer infused with regret and hope. Victims of atrocities are lined up to be “hosed down” and “inspected” before they’re put on the train. Is that sin being washed away? Or is the church merely following the model of the Nazis, forcing its "passengers" to conform to some false ideal, building a faux kingdom on earth, with a gospel train that won't even leave the station? In the midst of these lines, “I once was blind, but now I see” is probably intended with painful irony. You get the sense he wishes he could be blind again. The album closes with a hint of dissonance, as if all of this "happiness" among the redeemed might be premature, as if the ugliness of humanity’s evil may produce too great a stinking cloud for anyone to catch a glimpse of a hopeful horizon.

In days as dark as these, when the people of the world hear nothing but speeches about goodwill, honor, peace, and freedom from their leaders, and yet hear the constant reports of lies, incompetence, failures, increasing hatred, violence, and chaos, these two albums play like the soundtrack to the age. Cave offers no false hopes, no touchy-feely assurances. He’s hurt, betrayed, angry, and desperate for the Gospel to prove true. And at the same time, he knows he is made of the same crude matter as those deceivers who lead innocents to the slaughter. This is as honest, as raw, and as powerful as rock and roll gets.

Five words or less: The two peaks of Cave's career.

WELCOME.

Welcome to the new all-in-one site for Looking Closer.

Looking for the blog? It's called "The Journal."

Looking for reviews? We're transferring them as fast as we can. Most of the film reviews are up, but the music reviews... well... we've barely scratched the surface there yet. Please be patient.

Looking for information on my books? You'll find it, although there's still a lot of organizing to do.

Many many more features are in the works.

If you need access to a particular review or article that's missing, let me know and I'll move it to the top of my priority list.

But as this is happening while I'm struggling to meet several writing deadlines, things are a bit crazy. So I appreciate your patience, and I want your input!

Please take this opportunity to thank Dave Von Bieker of www.bodycreative.com, who volunteered to consolidate my various sites and blogs into one convenient location. I'm not sure he knew the mess he was getting into, but he's done it all with grace, style, and patience.

Now, if you'll excuse me... I have to get back to developing this brave new world.

Make your case: Why We Love WALL-E.

It's the most joyous time of the year.

Yes, I'm talking about Oscar season.

Ratatouille (2007)

This review was originally published in June 2007 at Christianity Today.

•

Attention, parents, kids, anybody who appreciates good movies and great food! Ratatouille is a feast so fantastic you'll go running back for seconds. And if you pay close attention, you'll also see that it's a film that tells two great stories at the same time.

The first story is what you'll see on the big screen. And the second — at least the way I see it — is a more subtle, almost allegorical re-telling of what really happened to one of the 20th century's most-loved and enduring pop culture icons … Walt Disney himself.

Once upon a time, there was an adventurous French chef named Auguste Gusteau (think Walt Disney) whose Paris kitchen (think Disney studios) was famous for awe-inspiring cuisine (Disney's classic animated features, like Pinocchio).

Gusteau knew his strengths and focused on them, serving up heaping plates of excellence to the delight of the customers at his self-titled restaurant. Gusteau's and its namesake became legendary worldwide.

But then, for one reason or another, the quality of his work began to falter. He died, and his successors (think …. Michael Eisner?) sold out, stamping the Gusteau (Disney) name on all manner of mediocrity. The master's face and name eventually flew like a banner over mediocre microwave meals (frivolous features like Pocahontas, and disposable straight-to-video sequels to Disney classics). And eventually his name represented fare that seemed completely unrelated to his legacy (The Muppets?).

And while the masses seemed content to choke down anything contained in a Gusteau can (or released on a Disney label), it looked like Gusteau's name would become synonymous with trash.

Enter Remy, a little rat with a nose for excellence and a passion for cooking. (Enter director Brad Bird, the brilliant storyteller and filmmaker behind The Iron Giant and The Incredibles.)

Remy would never, in normal circumstances, be allowed into the great Gusteau's kitchen. He's a rat after all, likely to be exterminated before his extraordinary talent wins the attention it deserves. (Bird's Iron Giant was badly botched by Warner Brothers, who didn't know that they had a classic on their hands. Thus it never got the box office it deserved.)

But then, Remy meets Linguini (voiced by Lou Romano), a gawky, insecure fellow who works as the kitchen garbage boy. He couldn't cook a microwave dinner if he tried. And yet, when Remy climbs beneath Linguini's chef hat and begins to direct Linguini around the kitchen by pulling on his hair — presto! Or should I say, Pesto?

Can a little guy with a big imagination step into that famous kitchen and restore it to its former glory? Yes. (And yes!)

With Remy's creative genius and Linguini's access to the pots, pans, and ingredients, a new Gusteau masterpiece is just a matter of time. (In the same way, Pixar's powerful chemistry has produced a string of masterpieces ... delivered with the Disney label: A Bug's Life, Toy Story 2, Monsters Inc., Finding Nemo, The Incredibles, and Cars.)

The story then begins to resemble the Coen Brothers' Hudsucker Proxy. By underestimating a simpleton who works at the lowest level, Skinner the wicked franchise-master (voiced brilliantly by Ian "Bilbo Baggins" Holm) unwittingly jeopardizes his moneymaking empire.

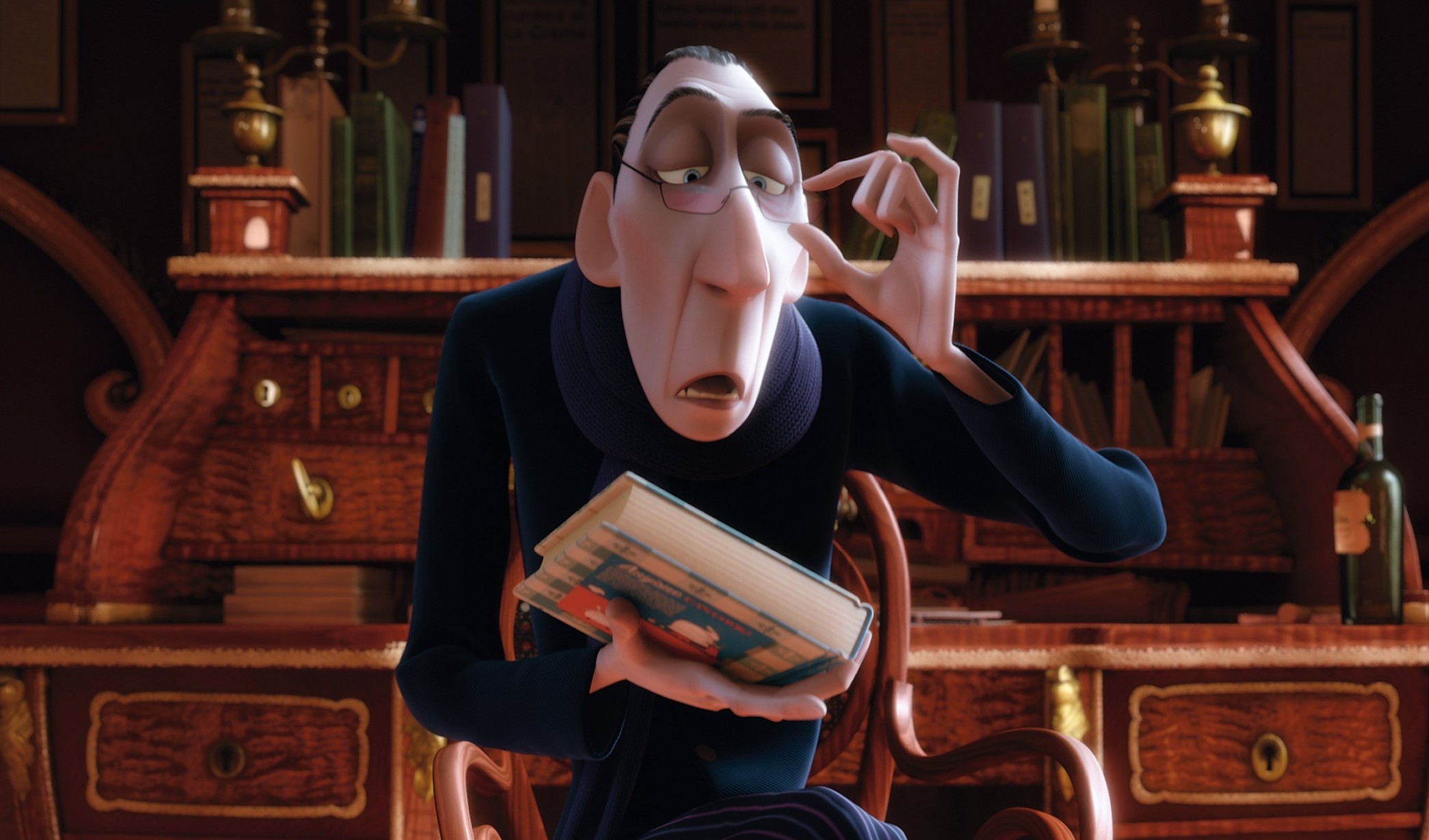

When the simpleton serves up a super soup, it seems that the Paris spotlight just might shine on Gusteau's again. It all depends on the reaction of the city's most demanding food critic, Anton Ego, who looks down his nose at almost everything. And with his nose, that's a very long way indeed.

While it seems inappropriate to equate Brad Bird with a rat, Ratatouille clearly reflects what has happened since Pixar arrived in the Disney kitchen (for more details, see this book and/or this). It isn't just the audience that has responded with enthusiasm. The critics — snobs, crowdpleasers, egomaniacs, and experts of all stripes — have lavished Pixar's productions with rave reviews.

But whatever you make of the subtext, you're likely to agree with the hard-to-please critics who embrace this dazzling — dare I say profound? — motion picture. No matter your age, you'll probably find Ratatouille both satisfying and nourishing. In fact, it may be the first Pixar production more likely to win fans among adults than children. (At 111 minutes, it may test some toddlers' patience.)

A few words about animation: Just when you think that Pixar has set an unsurpassable standard (Finding Nemo, The Incredibles), they astonish us with new innovations.

The most impressive aspect of Ratatouille's animation is its depth and color. When the Almighty sees the glory of a Paris sunrise in this movie, he might just give Pixar the controls for real-world artistry. The dark, reflective surface of the rushing stream that washes Remy away from his family of thieving rodents proves that even the gutter can be beautiful through the eyes of an artist.

Even more surprising is Pixar's continuing progress in creating animated human beings. Ratatouille introduces two outrageous cartoon personalities — Skinner the diminutive head chef, and Anton Ego, the stilt-legged restaurant critic whose attitude fits his name (voiced with grandiose contempt by Peter O'Toole). Both of them command our attention even more powerfully than the fuzzy little critters. Ego, with his magisterial condescension and Nosferatu posture, deserves a place in the Disney villain hall of fame alongside Cruella de Vil and Captain Hook.

But Linguini (Lou Romano) is the main event. He's the most reluctant of Disney heroes since The Rescuers' Bernard, but what he lacks in personality he more than makes up for in choreography. Cooking up a storm, Linguini flails about the kitchen like a marionette in the hands of a particularly animated (pun certainly intended) puppeteer. Remember when Steve Martin was possessed by Lily Tomlin's ghost in All of Me? You get the picture.

It wouldn't be Paris without romance, and this stew is spiced with the help of a beautiful, hard-working chef named Colette Tautou (Janeane Garofalo), who laments the difficulty of being a woman in the dog-eat-dog restaurant industry.

And as you watch Colette and Linguini work, you'll be enthralled by the animators' attention to detail. These kitchens bustle in a way that shows the animators' research in some first-rate kitchens. Ratatouille is probably the first animated feature to deserve inclusion on the list of great "foodie" films, alongside Babette's Feast, Mostly Martha, Big Night, Like Water for Chocolate, Sideways, and Eat Drink Man Woman. Fine restaurants located alongside movie theaters are about to experience a boost in their business.

Enough about animation: Any movie helmed by Brad Bird is just as much a feat of storytelling as it is a triumph of animation. And Ratatouille is no exception.

From Cinderella to An American Tail, we've seen a lot of rodents on the big screen. (Watch for one clear visual nod of acknowledgement to Don Bluth's The Secret of NIMH.) But Remy, voiced by comedian Patton Oswalt, is remarkable. Where most famous rodents are merely clever, Remy has a passion for culinary creativity.

As Remy tries to save his fellow rats from the humiliation of swallowing trash, he discovers what so many art lovers already know: It's hard to teach good taste. To steal a phrase from Franky Schaeffer, this fast-food nation is addicted to mediocrity. As we content ourselves on junk food, avoiding the opportunity to experience new things and discover delicious, nourishing fare, we also demonstrate our lack of discernment in what we choose to watch on television, order from iTunes, or see at the movies. Excellence matters, says Remy. And he tries to awaken his friends to a new world of flavor. As he does, savory sensations are illustrated brilliantly through abstract explosions of color.

There is so much to enjoy and celebrate here, Ratatouille deserves more than a review: it could (and probably will) inspire books about creativity and good taste. First and foremost, it's a story about claiming your passion, and pursuing it with excellence, whether you make big bucks or not. Children and grownups alike will learn the joy of adventurous taste — not just in the kitchen, but in art.

And as it urges us toward an appreciation of excellence, it also gives snobs a roundhouse kick to the palate. In the film's closing act, the storytellers dare to address the role of the critic in society. They remind us that, while we should certainly set our standards high and muster the guts to call garbage what it is, we should also remember that criticism must come from a place of love and passion, not cynicism, arrogance, or condescension. We should recognize greatness, originality, and vision wherever we find it — whether it's from an unknown Ukrainian director at the Venice Film Festival, or from an American storyteller inside Disney studios. It's an ambitious subject for an animated feature. Handled with such grace and insight, it raises Ratatouille to greatness.

So go ahead, serve yourself a heaping plate of Ratatouille, which is likely to be remembered as 2007's summer moviegoing peak. It'll be hard for some to admit, but thanks to this Parisian fairy tale, Walt Disney Studios is once again the premiere filmmaking kitchen in America. Like those diners who swoon at the aroma wafting from Remy's restaurant, moviegoers will keep coming back for seconds, and thirds, so long as Brad Bird is in the kitchen.

Evening (2007)

[This review of Evening was originally published at Christianity Today.]

•

Stand and stare in awe at the poster for Lajos Koltai's new film Evening. Look at that impressive cast list. Vanessa Redgrave! Meryl Streep! Glenn Close! Claire Danes! Toni Collette! All in the same movie!

It gets better: Redgrave gets to share a scene with her real-life daughter Natasha Richardson. And the mother/daughter goodness doesn't stop there: Streep plays a senior citizen who appears in flashback played by her real-life daughter, Mamie Gummer.

With that kind of star power and intrigue, it's likely that Evening will draw crowds of moviegoers with high expectations. But many will be disappointed.

Evening feels artificial from the very first shot. We see a young woman reclining peacefully on a boat, resting on placid Rhode Island waters against a vivid sunset. Some may find the image breathtakingly beautiful. But there's something strangely artificial about it. It's so picturesque, with that digitally manufactured sky and that woman so perfectly posed, that it feels sentimental and idealistic—the stuff of vacation-brochure photography.

In the same way, the rest of the movie is obsessed with wishful thinking. And thus, we're in for two hours of breakdowns due to life's disappointments. But those moviegoers who stop to think about the characters' choices will find it hard to pity them. They're all prisoners either of their own decisions, their adolescent urges, or their culture. "We are mysterious creatures," murmurs one old woman, reflecting on her life. The mystery, from where I sit, is this: What in the world does this movie want us to learn from these unhappy people?

There's "no such thing as a mistake," according to the film's appointed voice of wisdom. And yet, the film's 117 minutes are full of evidence that people can make catastrophic decisions and regret them for the rest of their lives.

The film is drawn from an acclaimed 2005 novel by Susan Minot. But screenwriter Michael Cunningham changes the location, eliminates and revises characters, and brings one of Minot's peripheral characters to the forefront. (A recent New York Times article details these revisions, and Minot's lack of enthusiasm for Cunningham's work.) Instead of a story about sisters who learn lessons by uncovering lost chapters of their mother's life, Cunningham wants to tell a story about Buddy, a sexually confused drunkard who feels trapped in an oppressive society.

Since Buddy brings so much baggage with him, and since we already have a host of complicated characters, Evening feels like several conflicting narratives competing for our attention. In fact, it feels like Cunningham is trying to turn Minot's story into a continuation of his own pathos-saturated novel, The Hours, in which characters imprisoned in a culture of conformity suffered and longed for something more. What might have been a revealing meditation on mother/daughter relationships becomes muddled by questions about gender and sexual orientation.

The story introduces us to Ann Lord (Redgrave), an old woman on her deathbed being cared for by her daughters, Constance and Nina (Richardson and Collette), and her Irish "night nurse" (Eileen Atkins). As Ann fades in and out of consciousness, she murmurs about her memories, delirious. Her daughters are surprised. "Who's Harris?" "What was this 'big mistake'?" "What does she mean, 'Harris and I killed Buddy'?"

Constance writes off these fragments as mere delusion. Constance has a marriage and three children to worry about, and isn't interested in unsettling revelations or scandal.

But Nina is unstable. Her life's a scrapbook of mistakes. Confused about her relationship with her latest boyfriend, she's having trouble sorting out her priorities. If her mother really does regret some big mistake, Nina wants to uncover it and glean what wisdom she can. So she begins to piece together the mystery of her mother's past. Eventually, it will be up to Ann's old friend Lila (Streep) to drop by for a visit, fill in the blanks, and solve the puzzle.

We have an advantage over Nina. We get to watch Ann's "big mistake" unfold on one fateful weekend in the 1950s. (This may remind moviegoers of another Redgrave movie—Mrs. Dalloway—which also flashed forward and backward in time. Nastasha McElhone played the young Dalloway; here, young Ann is played by Claire Danes.)

In this earlier story, Ann's close friend, Lila Wittenborn (Gummer), is reluctantly preparing to wed the respectable Carl Ross. This delights her mother (Close), her father (Barry Bostwick), and the whole snobbish community.

But we quickly learn that Lila's heart does not belong to her fiancé. She's obsessed instead with Harris (Little Children's Patrick Wilson), the handsome son of the family housekeeper. This obsession is obvious not only to Ann but also to Lila's brother Buddy (Hugh Dancy), a sexually confused alcoholic. Together, Ann and Buddy try to convince Lila to call off the wedding.

To make matters worse, Buddy is also attracted to Harris.

And then, of course, Ann becomes attracted to him too. But Ann, who is so different from this wealthy, formal, dishonest community, is not afraid to let her passions lead her. She's a rash, impulsive, bohemian singer. It's only a matter of time before she's running off into the woods with Harris for a night of lustful indulgence.

The love story of Ann and Harris is not only unconvincing, it's entirely superficial and shallow. We're meant to swoon as they fall in love, and then to grieve at the tragic events that follow. But the relationship is so ill-advised and foolish to begin with, it's difficult to feel much for them at all.

The portrayal of Harris is the film's biggest problem. We're supposed to believe that Harris is the glorious sun which all of these morose young ladies orbit. But he's more like a black hole than a star. Patrick Wilson was born to play immature charmers like this; he's like a bewildered child in the body of an Abercrombie & Fitch model. In Little Children, director Todd Field employed Wilson's presence to make profound observations about irresponsibility and immaturity. But here, even though Wilson's Harris is similarly reckless and naï ve, Cunningham and Koltai hold him up as some kind of golden god.

As the women sigh and coo and murmur, "No one ever moved me like Harris," you realize how superficial and shallow they all are. Later, Ann questions whether Harris was so ideal, but the film offers us nothing more appealing than that adolescent fantasy. And the world of grownups—of marriage, family, commitment, and tradition—is portrayed as a purgatory of regret, burdensome compromises, and disappointment. While the film culminates in one character's agreement to give up her obstinate ways and "grow up," there's very little joy in that conclusion.

The hollowness at the center of Evening has everything to do with its mixed messages about happiness. It reveres shallow romantic fantasies, and then laments that we have to give them up in order to shoulder the burden of maturity. What these characters need is to overcome their malignant nostalgia and discover the joy that comes from real, unselfish love.

But there are other problems. This convergence of so many legendary actresses might have been a master class in acting. Instead, it looks like a contest to see which actress can shed the tears that will win a Best Supporting Actress Oscar.

Worst of all is Glenn Close as Mrs. Wittenborn, the queen bee of this poisonous hive. She's only onscreen for a few minutes, playing a matriarch whose denial is as frightening as her maniacal grin. It's a one-note character, and in this keyboard of one-note characters, it's a minor note indeed—but she pounds on it until it breaks. When crisis hits the family, her atomic breakdown recalls Sean Penn's Oscar-begging (and, alas, Oscar-winning) Mystic River meltdown.

It's too bad, really, because there are some real performances here. They're hard to find amidst the melodrama, but Toni Collette gives Nina convincing details and dimension. Redgrave and Streep find a wonderful tenderness in their fleeting scene, and they leave us hungry for more. But the story is more interested in pretty, empty moments. When Ann dances out of her deathbed in a moment of magical realism to chase luminescent moths, it looks suspiciously like a commercial for air freshener.

The movie's strongest scene brings Danes up for an amateur's turn at the microphone, singing a sultry jazz number in front of the wedding party. It's not lip-synched, it's real. And when Wilson steps up for backing vocals, oh how you want something magical to occur—something like that recent Gap commercial, in which Danes and Wilson dance across our television screens with heart, chemistry, and grace. But no, there's nothing so spirited, spontaneous, and alive as that commercial here in this morass of melodrama and misguided behavior.

Closer (2004)

[This review was originally published at Christianity Today.]

Closer, the new film from Mike Nichols (Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, The Graduate), has a lot in common with the "smoker's lung" billboard.

You know the one — there's a cigarette in the left frame, and a blackened, diseased lung on the right. It's a troubling image. You're driving along sipping coffee or tea, you see the picture, and you choke. Nobody wants to see such ugliness. But it works. Sometimes. Especially for young people. That nauseating image of rotten tissue is enough to make a few of them say, "Not in my chest cavity!" It exposes the glamour of cigarettes as a lie, a short-term, feel-good rush that leads to long-term heartache.

Closer works like that. But it's not about smoking — it's about unfaithfulness. And instead of showing us ruined lungs, it exposes ruined hearts. Instead of disintegrating organs, we see souls sickened from dishonesty, anger, hate, emotional violence, grief, loss, and loneliness.

How interesting that Closer arrives while Bill Condon's film Kinsey is still in theatres. Kinsey celebrates the scientist who told the 1960s to stop thinking about sex in a restrictive moral framework, and to enjoy it in any way we please. After all, we're just animals, and sex is "animal behavior." Closer contradicts this, suggesting that when people behave like animals, adhering only to their base desires and self-centered impulses instead of to conscience, morality, and promises, they end up lacking the blessings that human beings have the distinctive opportunity to enjoy. Closer — like We Don't Live Here Anymore, 2004's other "adultery film" — demonstrates that saying "It feels good, so it must be okay" leads to a relentless, heart-hardening search for satisfaction.

Adapted from Patrick Marber's play, Closer deals with themes as old as the story of David's malevolent conspiracy to take Bathsheba from her husband. Like Adam and Eve, the characters want whatever is out-of-bounds, and when they transgress, they tear the seams of their own lives and the lives of others.

Dan (Jude Law), a British obituary writer, is "in love" with Alice (Natalie Portman), an American dancing at a London strip club. Their eyes first met a few fluttering heartbeats before a truck knocked her flat, and Dan hurried her to the hospital — what a noble hero! — for some band-aids. Charmed, Alice flirts with him by polishing his glasses and performing other small revisions. Similarly, Dan writes a novel in which he "revises" Alice into a fictional character of his own fantasies. The reality, however, is sure to disappoint them in the end.

Riding high on his novel's success, Dan seizes an opportunity to seduce a photographer named Anna (Julia Roberts) when their first meeting generates romantic sparks. After an initial kiss, Anna's conscience prods her to break free of him; she knows about Alice. But it's not long before Alice's heart is broken by the truth, and her trust in Dan is broken. Ever opportunistic, Anna snaps a photograph of Alice in her ruined state. With that, the relational disintegration begins in earnest.

Who's the fourth player? A dermatologist named Larry (Gosford Park's Clive Owen), who spends his professional time giving prescriptions and his spare time surfing the Web for pornography and cybersex. Online, he unwittingly becomes the pawn of a practical joker — Dan — who uses him to make Anna pay for her rejection. Dan doesn't realize he'll become the butt of his own joke. (Do Anna and Larry actually fall in love? Or is Anna merely working out a counter-revenge ploy against Dan?) Before you know it, two of them are married, adultery's close behind, one is paying for the indecent exposure of another, and they're all angrier, emptier, and placing the blame on everyone but themselves.

It's an ugly film … like that picture of the ugly lung, but withoutthe picture of the cigarette. We see the disease, but we have to interpret for ourselves the source of the problem. Closer isn't just sensationalized misbehavior; it's an earnest search for the root of unhappiness in the lives of four very different, yet similarly depraved people. It doesn't condone the sin; it exposes it.

Interpretations will vary. But any close consideration of these characters should lead viewers to the conclusion that — for all of their talk about "love" (and there is a lot of talk) — love is the very thing that's missing. They prioritize the thrill of "falling in love" over the work of "staying in love," and thus they can't even guess at the rewards of mature love, a love that remains steadfast even when disappointed, even when fickle feelings falter.

Moviegoers and even critics aren't always interested in interpreting a movie, however. They'll line up to see Law, Roberts, Owen, and Portman in steamy, intimate situations, and they'll discuss possible Oscar nominations. Critics will praise the film for its audacity and intensity. Like Closer’s characters, many will be disappointed, and some may even "break up" with the film halfway through. Most will fail to notice (or avoid acknowledging) the troubling truth it reveals. Like the scene in which arts patrons praise Anna's photograph of the heartbroken Alice, they will say "marvelous" and "compelling," whiling ignoring the truth the image communicates.

The film earns some of that praise. Roberts makes Anna subtle, complicated, and burdened with conscience. Law (in his fourth of six 2004 performances!) turns Dan into an egotistical monster with the emotional maturity of spoiled child. Most famous for her monotone performance in the Star Wars prequels, Natalie Portman revels in the role of Alice, who conceals her dying heart behind a façade of carefree sexuality; this ensures Portman will hereafter be treated as a "serious actor"—and as a sex object.

Owen, whose talents were wasted in the shallow action epic King Arthur, earns our sympathy (temporarily) as a misbehaving doctor who tries to better himself as a responsible husband. His transformation from enthusiastic newlywed to devastated cuckold is painfully convincing. And his ensuing wrath, which drives him to eviscerate not only his spouse but her lover as well, will tweak the conscience of many who have suffered such betrayals. Lecturing Dan on relational warfare, he describes the human heart as looking like "a fist, soaked in blood."

Nevertheless, Nichols and Farber have transferred the play to the screen without imagination. The non-stop dialogue is better suited to the stage. In the realism of a film, the characters seem to speak too intelligently, at times too poetically, and sometimes just too much. "Talky" films have always been Nichols' specialty, from Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? to Carnal Knowledge to his recent, award-winning HBO films. But Closer lacks the thoughtfulness of Wit, the situational comedy of The Graduate, the exaggerated personalities of Primary Colors and The Birdcage, and the sympathetic characters of Angels in America. The wordy wickedness becomes wearying.

Closer isn't a film I'd eagerly recommend, just as you wouldn't want to pay for the privilege of examining that diseased smoker's lung. Dan, Alice, Larry, and Anna behave so badly, many viewers will ask (to borrow another Nichols film title) "What Planet Are You From?" Here's a heavy caution: Scenes set in a strip club may be, for many, an unhealthy distraction (or worse), even though these scenes, taken in context, reveal the emptiness and sickness of loose sexual behavior. If you are one of the Christianity Today readers who aims to avoid foul-mouthed characters, steer clear of this film — the R-rated language employs every obscenity and expletive in the book, loudly and viciously, several times over. Divided lovers interrogate each other with graphic specificity.

But just as we should be glad that the smoker's lungs are posted on that billboard, so we should be glad that this film speaks the messy truth to those who do see it. It is not a film to be flatly condemned or disregarded. For those deceived by the seductive glamour of tabloid personalities, this could be a nasty wake-up call. It might make people hesitate before hooking up over the Internet or fooling around behind their spouse's back. Like its literary cousin Dangerous Liaisons, this drama about lovers is resolutely unromantic and uninspiring, and nobody would describe it as (to use a popular term among Christianity Today readers) "wholesome." But it shares the redeeming virtue of Dangerous Liaisons: in showing us so much unpleasantness and the wages of those sins, it shows us the necessary truth about what happens to "love" outside the bounds of accountability.

Closer could have given us a fuller understanding of love if it had given us even a glimpse of a character with some integrity. But the consequences of wrongdoing serve as a strong signpost here, directing us away from danger. In U2's song "A Man and a Woman," Bono makes a pledge to his beloved: "I could never take a chance / of losing love to find romance." These characters take that chance. And they pay the price.

Letters from Iwo Jima (2006)

[This review was originally published at Christianity Today.]

•

"Am I digging my own grave?" young Saigo wonders as he helps his fellow Japanese soldiers shovel out bunkers in the dark sand beneath Mt. Surabachi. And because we know the outcome of the Battle of Iwo Jima, we can make an educated guess at the answer to his question.

In an unprecedented work of ambition and vision, Clint Eastwood has released two films in one year about that historic battle: Flags of Our Fathers, which illustrates the American experience of the conflict, and now Letters from Iwo Jima, which draws us into the experience of the outnumbered, ill-equipped Japanese defeated in that battle in 1945.

The two films, produced with lifelike intensity and meticulous attention to period detail, mirror each other with subtlety and cleverness.

Flags asks us to reconsider American notions of heroism. Letters asks us to assess the Japanese concept of dignity, even confronting us with the grisly reality of the soldiers' suicide tactics, which they carry out in the name of "honor." (Watch out — the combat scenes are extravagantly bloody.)

Flags shows us the incongruity between the images of glorious heroism delivered to the American public, and the nightmares of battlefield reality. Letters shows a similar disconnect, as Japanese soldiers collapse in hopelessness while inspirational radio broadcasts from the homeland convey confidence of victory.

Flags shows U.S. authorities "revising" stories from the front lines in order to inspire the American people. Letters portrays soldiers who write letters home, only to see censors clip out anything judged "unpatriotic."

Both films show us soldiers who behave with dignity, and others who become barbaric on the battlefield.

But Letters from Iwo Jima is distinguished by something rarely seen in American war films. To craft a work of art that allows us to enter the minds of our enemies, recognize their humanity, and come to care for them—that is as noble a gesture as an artist can make. "Love your enemies, and pray for those who persecute you," Jesus said. It's much easier and more invigorating to think of the enemy as soulless devils; all the better for mowing them down with machine guns.

And at first glance Letters from Iwo Jima seems like an inspired endeavor to portray the enemy with compassion and dignity. That's why film critics across the country are falling over themselves to heap superlatives on Eastwood's efforts. For many years, American media helped establish lamentable Japanese stereotypes, so it's about time an American director stepped in to consider the Japanese experience with some care.

Further to its credit, Letters from Iwo Jima illustrates — with drama, detail, strong performances, and technical mastery — the sufferings of the Japanese as they fought. It's one thing to read about how they were outnumbered, plagued with dysentery, starving, crippled by communication breakdowns, and torn between divided superiors. It's another thing to let Eastwood take us into that situation.

Aesthetically, Letters is one of the most impressive war films I've ever seen. Tom Stern casts the chaos in muted colors until it's almost a black-and-white film, just as he did for Flags. This gives the film the look of archival footage, even as it enhances the chilly, forbidding character of the island. Against this backdrop, the Japanese flags stand out bold and red, and when the U.S. bombers make their first strike, almost an hour into the film, the explosions are jarringly colorful.

The film's episodic structure follows the simple-but-effective pattern employed every week on TV's Lost. We meet the characters in a crisis, and then we come to appreciate them by getting flashbacks to their past. Letters focuses on four central characters:

Saigo (Kazunari Ninomiya) is the film's childlike hero, a young baker forced to leave behind his cute young wife Hanako (Nae) and their unborn child. Easily frustrated with his superiors, and unprepared for the hell about to be unleashed, Saigo is almost impossible to dislike. And as we watch him forced to carry pots of his fellow soldiers' waste out of their death-trap tunnels on Mt. Surabachi, well, we want this guy to catch a break.

Looming over Saigo like a legend, Gen. Tadamichi Kuribayashi (Watanabe) is the film's most impressive figure. He was, as the film portrays him, charming and dignified, respected by American officers, and known for sketching pictures of his experiences. (Those sketches are included in a book called Picture Letters From Commander in Chief, one of the film's primary inspirations.) Sent to lead the Iwo Jima defense after another officer refused, Kuribayashi arrives and takes control, causing controversy among the men but winning our admiration with his compassion and his old-fashioned sensibilities. He'd rather walk than get in a car; he'd rather talk about horses than tanks. And we feel his pain as his nation abandons him to strategize with disobedient, disrespectful officers while Americans overwhelm the island.

His friend, Baron Nishi (Tsuyoshi Ihara), also visited the U.S. for the 1932 Olympics, where he won a gold medal in an equestrian event. Nishi wins our sympathy through his love for horses and the mercy he gives to an American captive. In fact, Nishi is the one who makes the boldest statements in the film, striving to convince his fellow soldiers that the Americans are just like them. "Do what is right because it is right," he tells them.

When a traumatized member of the Kempeitai military police, Shimizu (Ryo Kase), shows up, he raises the anxieties of his fellow soldiers who suspect he's come to spy on them. But Eastwood's inclusion of Shimizu as the representative of the Kempeitai is just one example of how his selections heavily influence us to view the Japanese as not merely human, but as equivalents to the Allied soldiers in almost every way. What begins as compassion becomes a distortion. Why is it that of the notoriously wicked Japanese military police, Eastwood chooses to focus on a character who can't even follow orders to shoot an animal, much less harm a human being? Even more tellingly, this officer ends up falling into the hands of a barbaric American soldier. A little irony goes a long way, but this?

Yes, Eastwood and his screenwriters, Iris Yamashita and Crash-scribe Paul Haggis, have taken their compassion much too far. In his New York Times review, A.O. Scott writes, "It is hard to think of another war movie that has gone so deeply, so sensitively, into the mind-set of the opposing side." To that I would add, it's hard to think of a war film that works so hard to make us fall in love with the enemy, and to airbrush their portraits.

It's one thing to learn to love your enemies. It's another thing to view them through rose-colored glasses. We also need to honor the memory of those Allied forces who suffered from Japanese tactics and agendas, which are largely erased from this picture.

Yes, in almost any war you can find soldiers on both sides doing disgraceful things. (For example, it would be foolish for Americans to talk about the "war on terror" without mentioning Abu Ghraib.) And it is right for Eastwood to acknowledge this. But World War II was fought for compelling reasons, and its armies operated under different notions of duty and dignity. Eastwood has done nothing to prevent viewers from accepting these likable, good-natured, conscientious characters as representative of the Japanese forces. It's hard to imagine that men like these were guilty of so many war crimes against millions of POWs and civilians. (Look up "the Rape of Nanking," or read about the Japanese treatment of POWs, for starters. You find a very different picture there.) The Japanese Imperialist forces were some of the most barbaric in recent history.

You might guess that Flags would be the film most likely to win acclaim at the upcoming Oscars.Letters, by comparison, is unconventional. It's a foreign-language film, with only a few fleeting glimpses of American soldiers up close. Ken Watanabe, who made a strong impression in The Last Samurai, and threatened Bruce Wayne in Batman Begins, is probably the only actor you'll recognize. It's about the losing side, not the victors. And there's no love story to sweeten the descent of these Japanese soldiers on the island equivalent of The Titanic. Normally, a film so lacking in glamour and inspiration would be treated as an admirable novelty.

And yet, this is a Clint Eastwood film. Maintaining his reputation for profound, professional filmmaking, he's crafted a heartbreaking lament for the countless lives that might have flourished if the war had been averted. And while his storytelling is workmanlike at best, Letters is a virtuosic display of technical excellence. Add to that the magnitude of this Herculean two-film feat, and the fact that Letters is an act of gratuitous compassion from a veteran of American war movies, and you've got to see the likelihood of Oscar glory.

If only these powerfully talented filmmakers had given us some context, some reminder as to why the war was fought. If only they had been truer in illustrating the distinctions between the armies — and nations — fighting it. They might not have been carried away from the facts and into wishful thinking.

Million Dollar Baby (2004)

[This review was originally published at Christianity Today.]

Some people live lives in which their prayers are answered, their dreams fulfilled, their needs met, and their lives richly blessed. Others live lives of frustration, longing to hear God's voice, carrying excruciating burdens and struggling to maintain their belief that their Creator cares … or that he exists at all.

Million Dollar Baby looks like a boxing movie, but at its heart, it is the story of a spiritually frustrated man. Frankie Dunn (Clint Eastwood) is a boxing trainer and "cut man." When a fighter is wounded, Frankie steps into the ring, wipes up the blood, resets broken bones, and gauges how much more they can take.

He may be good at patching up others' wounds, but Frankie can't stop his own cuts from bleeding. At night, he kneels, weighed down by the burden of regrets, and asks God to heal his wounds. He attends daily mass, but instead of voicing his deepest conflict, he harasses an exasperated priest with dogmatic questions about the Trinity and the Immaculate Conception. And while he spends his weeks counseling fighters about how to move their feet, his vocabulary becomes a kind of poetry describing his struggle to "protect himself" in fights he can't win on his own. Ultimately, when Frankie and his partner Scrap-Iron (Morgan Freeman) talk about boxing, they're talking about survival. "Everybody's got a particular number of fights in 'em," says Scrap. "Nobody knows what that number is."

There's no American filmmaker more concerned with mortality that Clint Eastwood. He's preoccupied with the consequences of violence and the forces that motivate men to fight. Here, he's chosen the perfect actor to play the troubled trainer — himself. Those famous Westerns about the "pale rider" who dealt out death and judgment have made Eastwood's visage one of Hollywood's most familiar. As he gets older, he digs deeper into questions of conscience, and his wizened, tightly drawn face seems to become more grim and skull-like, as if morphing into a symbol of his chosen subject.

Million Dollar Baby is not a Western, but it's just as primal and bleak as Unforgiven. This is Eastwood's most accomplished film, and he finds in Paul Haggis's screenplay (based on short stories by F.X. Toole) the richest, most complex character he's ever played. It's a familiar plotline — the grizzled old pro being convinced to take a gamble on a longshot. That longshot is Maggie Fitzgerald (Hilary Swank), a young woman from backwoods "Missourah" desperate to escape her "trailer-trash" past by chasing her dream of being a fighter. Frankie thinks girlfights are "the latest freakshow," but the last fighter he trained betrayed him, and that's only added to his feelings of failure as a father figure. There's no suspense in whether he'll take Maggie on; we know they're a perfect match. What we don't know is just how intimately we'll get to know them, and how hard a road they'll travel together.

Million Dollar Baby joins Sideways, Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, and Before Sunset among 2004's finest examples of excellent writing. Haggis develops characters so real and endearing, you'll wish you could invite them out for pie and coffee. Tom Stern—the film's chief lighting technician—frames them in the simple, stark imagery of a bright white boxing ring in a dark arena, and the cold illumination of bare light bulbs in a training gym after hours. While the cinematography tells this bare-bones tale sharply and efficiently, and Eastwood's understated guitar notes gently enhance the drama, it's Freeman's doleful, musical narration that gives Million Dollar Baby its haunting beauty. Great filmmakers show more than they tell, and thus it's fair to ask if Million Dollar Baby might be earning too much praise as a film when most of its power lies in its narration. But in a year when movies heaped indulgent visual spectacle on undernourished scripts, it's hard to complain about a movie with so much exquisite language.

Yet, while the narration gives the film a strong, simple skeleton, the actors put plenty of meat on those bones. They clearly appreciate the lines they're given to speak. Eastwood appears more world-weary and vulnerable than ever before, as if cracking under the pressure of life's beatings even as he teaches boxers how to fight, how to lose, and how to get up and fight again. As we watch him work, we catch hints of the failures he conceals behind clenched teeth. It's his best performance.

Freeman, who created a beloved character in Unforgiven, proves a dependable partner again, serving as the play's Greek chorus with a sense of humor as dry as a leather punching bag. Like Frankie the old-timer and Maggie the upstart, Scrap-Iron seems at first like a pulp fiction cliché. He's a retired boxer whose career ended with a blow that cost him his right eye. But he and Eastwood engage in an easy, relaxed banter, exposing layer upon layer of their history, until they become fully developed personalities.

Swank stands apart from almost all celebrity actresses in that, while she's clearly equipped to be a glamorous star, she avoids exploiting her appearance and focuses instead on inhabiting rough-edged, broken characters. She should — and probably will — win another Oscar for the way she transforms Maggie from a scrappy, ambitious, wounded girl into a ferocious, intense, ecstatically victorious fighter. (The bloody punishment she endures in the ring provoked one critic to say she'd been "Caviezel-ed.") Instead of over-acting in the "big scenes" the way Sean Penn did in Mystic River, Swank instead makes the most subtle pauses in the action. When Maggie shares a shy smile with a young girl at gas station, the silent exchange speaks volumes.

Moments like this enable the film to transcend its genre clichés. Each scene resonates on several levels, revealing things about characters' pasts, suggesting their possible futures, and reminding us of challenges we all face. Frankie's letters to his estranged daughter return marked "Return to Sender," paralleling his seemingly one-sided relationship with God. It becomes easier to understand why he's willing to risk his reputation on a "girlie." (After The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou and In Good Company, this is the third recent film in which characters try to fill the missing pieces of their families by "adopting" others who fit the description. Do you think our culture is coping with regret for devaluing family relationships?)

Only a few moments feel false, flat, or manipulative. During the entrance of Maggie's most formidable opponent (Lucia Rijker), the music sounds as though it's going to bust out into a Darth Vader villain-motif. And when Maggie's "hillbilly trash" family shows up to berate and exploit her, they're as mean as the zombies in Dawn of the Dead.

In fact, the film's biggest weakness is the way Haggis's script stacks the deck so unfairly against Maggie and her coach. Frankie's family history is a black hole, and Maggie's is a nightmare. Aside from Scrap-Iron, Frankie's business colleagues are disloyal, exploitative, and opportunistic.

And the church? Eastwood cops out, portraying God's agents on earth as utterly insufficient, suggesting that the path to God is a dead end. In his very first scene, Father Horvak (Brian O'Bryne) lashes out, labeling Frankie as a [insert harsh expletive here] pagan. He repeatedly discourages this doubting soul from attending mass. And in Frankie's darkest hour, he offers not comfort, but a threat that God's forgiveness might soon be out of reach. Eastwood clearly believes that the search for God is an honorable, even essential, pursuit. But by making God's only representative a man who should seek spiritual counsel instead of offering it, he tells us, "You're on your own in this life. Only fleeting glimmers of human kindness will help cushion life's cruel punches until we lose the fight altogether."

At the end, Frankie, Scrap, and Maggie make choices that will prod some viewers to grief and others to outrage. (One man at the screening I attended stood up and stormed out of the theatre in protest during the climactic exchange.) While I do not think the film glorifies the characters, it certainly goes too far in excusing them. We should object when Frankie and Maggie, driven by fear and despair, take matters into their own misguided hands; their decision is as rash as the crime committed by Jimmy Markum (Sean Penn) in Mystic River. And yet, we can feel compassion for these fighters who have been "stripped down to the bare wood." Like the naïve abortionist in Vera Drake, Frankie Dunn makes grave errors of judgment—he is acting out of kindness rather than malevolence, but his vision and compassion are too limited. And his decision does not earn him happiness. This is an honest portrayal of what the world looks like to those whose faith in a benevolent God fails. Million Dollar Baby may not be an inspiring movie, but it is at least honest about the consequences of giving up on God, and about our responsibility to be brave examples of love and grace to those who are suffering and afraid.

The film's closing act does not justify the condemnation that the film is sure to receive from reactionaries. Just because a character commits a sin does not rob a story of all of its virtues, and even a misguided tale can create opportunity for rewarding discussion. The final actions of Frankie and Maggie, while understandable and in some ways appealing, demonstrate a failure of hope, a lack of faith, a collapse of courage, and the loss of an opportunity for God to work wonders. Frankie would say he just "stepped into the punch," but I say he "throws in the towel." A desirable end does not justify deplorable means.

Hopefully, the despair at the end of this story will coax viewers to choose a different path if they ever face similar trials.

Spoiler Alert: The paragraphs below give away the ending to Million Dollar Baby.

Let's get specific.

The controversial resolution of Million Dollar Baby involves two characters who consent to the ending of another character's life in order to release that character from suffering — in a word: euthanasia. Specifically, when Maggie suffers a literally paralyzing blow in the boxing ring, she eventually comes to believe that she doesn't want to live the rest of her life as a quadriplegic, and she asks Frankie to pull the plug on the machine that's keeping her alive. Frankie refuses at first, but several developments in the story eventually change his mind, and he grants Maggie's wish.

Eastwood and his storytelling colleagues Toole and Haggis manipulate the events to try and win sympathy for their characters in this action. But there are plenty of details in the story that should show viewers the cost of such a decision, and that might even suggest there could have been a more meaningful and fruitful decision than the one made here.

As it plays out in the film, the act of euthanasia reduces the victim to the level of a dog, mentioned earlier in the film, that was put out of its misery. That seems, to this reviewer, to be a pessimistic and dispiriting decision for the characters, but does the film endorse their decision? I don't think so. After choosing death, Frankie disappears from the story into the darkness, the very despair and doom that his priest prophesied earlier in the film. He gives up, he fails, and his future will be determined by the grace of God. I find it hard to come away from this film with any sense of victory or admiration for Frankie's decision... only pity that he had to suffer such pressures, sadness that he and Maggie — the daughter he all but adopted — did not find their relationship worth living for. Million Dollar Baby is a tragedy, one in which we can feel compassion for its characters even as their moral fiber breaks under the pressure.

The Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers (2002)

The Two Towers is packed end-to-end with helter-skelter action, jaw-dropping New Zealand scenery, standard-setting animation, a lush and provocative soundtrack, and enough adventure for three or four typical films of its genre.

The Two Towers is packed end-to-end with helter-skelter action, jaw-dropping New Zealand scenery, standard-setting animation, a lush and provocative soundtrack, and enough adventure for three or four typical films of its genre.

Do you need more information? My review is at ChristianityToday.com.

But if you want the detailed review ... the mad ramblings of a Tolkien fan and a nit-picker ... settle in for a long read. These are the thoughts that buzzed in my head after I caught the sneak preview on December 10th.Read more