Raised by 20th Century Women

I know too many extraordinary people. I've been thinking about that a lot lately.

Sometimes I think about switching genres — hanging up the film-critic hat, putting the fantasy novels away — and just writing to the world about as many of them as possible. My family and their unlikely histories. My schoolteachers, the sacrifices they've made, their generosity. The mentors and guides. The artists who have illuminated my world. I've had that daydream a lot lately. Maybe it's the pandemic — maybe it's that reminder of how suddenly one or more of these magnificent characters might leave the stage. I'd like to say "I love you" in art.

I guess I'd like to be more like filmmaker Mike Mills.

Mills's movie Beginners (2010) gave Christopher Plummer one of his greatest roles: Plummer played a character loosely based on Mills' own father. Ewan McGregor was the filmmaker's modest self-portrait — a young man coming to understand that his father was more mysterious and complicated than he'd ever guessed. The movie glowed with respect, gratitude, and love. I was moved. (Who would I cast as my father? Not Christopher Plummer, clearly. Let's check on Christian Bale in 25 years, or Steve Coogan in 10.)

I was also impressed by the big creative risks that Mills took in order to say things that a typical, straightforward drama couldn't capture. The movie even found room for a talking dog — and it worked. A whimsical gambler, this Mills fellow. (Could I get away with a talking rabbit?)

When I spoke with Mills and McGregor in 2010 during the Seattle stop of their promotion tour, he talked about how he coached his cast to give such delicate, complex, and sincere performances: “I remember saying, ‘Help me not make this a narcissistic, self-pitying, sentimental memoir.’ I love films that are naturalistic and organic, when you feel the truth of life is in there somewhere.”

I should have made time in 2016 for Mike Mills’s next feature — 20th Century Women. I've seen it now, and it is every bit as impressive in the complexity of its characters, the clear affection Mills feels for them, and the stylistic adventurousness that keeps audiences guessing. Like Beginners, it's semi-autobiographical — but this time, it's a tapestry of tributes to women who raised him, inspired him, and taught him how to be a man. In those roles, he has cast Annette Bening, Greta Gerwig, and Elle Fanning.

What's more — and many critics have written about this in detail, and with greater historical insight that I can — it's a rich and complicated portrait of a transitional period in American history, with the ideals, values, and contradictions of several generations embodied by these women. We get lessons in history, psychotherapy, sex, and more from multiple threads of narration, different voices, different generations.

This time, the somewhat-self-portrait is of a younger Mills — this time, the young man is named Jamie, and played by Lucas Jade Zumann. It would have been easy for this 15-year-old growing up with his mother and her boarders in a Santa Barbara home to have become merely an avatar for the audience — wide-eyed, mystified, and sometimes bewildered by the dramas surrounding him. But Jamie is interesting enough in his own right. His story is about more than just witnessing these strong, challenging women — it’s about how by listening to women he might synthesize their wisdom and grow to be something better than the men they've known.

And, lest this testimony seem disingenuous, Mills is careful to avoid claims of authority or expertise: His women remain delightfully mysterious and unpredictable — that is to say, they’re alive enough to keep audiences guessing. As I eased into its meandering weave of storylines, I became increasingly delighted: This wasn't ever going to turn into a Movie Movie. Nothing would become more important than Jamie’s exploration of relationships and identity; no threat would emerge to the film’s free spirit, no crisis would draw us into any familiar arc, serving up Oscar moments for famous actors.

And then, suddenly, I recognized it. It was familiar. Without any insider knowledge, I came to suspect — or at least imagine — how the inspiration for this film might have occurred. Consider this possible origin story:

A filmmaker who has always wanted to make a film that celebrates the beautiful, complex, and influential women in his life, young and old, sees Cameron Crowe's year-2000 masterpiece Almost Famous for the first time.

The filmmaker marvels at the relationship between the young and fatherless William Miller (Patrick Fugit) and his mother Elaine (Frances McDormand), who wants him to be safe and good and responsible and drug-free, and who has feelings about the trouble with popular music.

The filmmaker marvels at young William's relationship with his gorgeous music-loving sister (Zooey Deschanel), who gives him her record collection and promises him that someday he'll be cool. And he is enchanted with the scenes of young William being embraced by, celebrated by, and sexually educated by a bunch of rock-star-obsessed girls who play with him like their new toy. And one of them — Penny Lane (Kate Hudson) — will grow William's heart several sizes larger and then break it.

The filmmaker isn't as interested in the stuff about the rock band young William is following, but something about Billy Crudup as an irresponsible rock god makes an impression. This character will get a good lecture from William's mother, who is never played as prudish or tyrannical, but is revealed for her wisdom in the end.

And so, with these Almost Famous impressions vividly in mind, this filmmaker goes and writes his own movie.

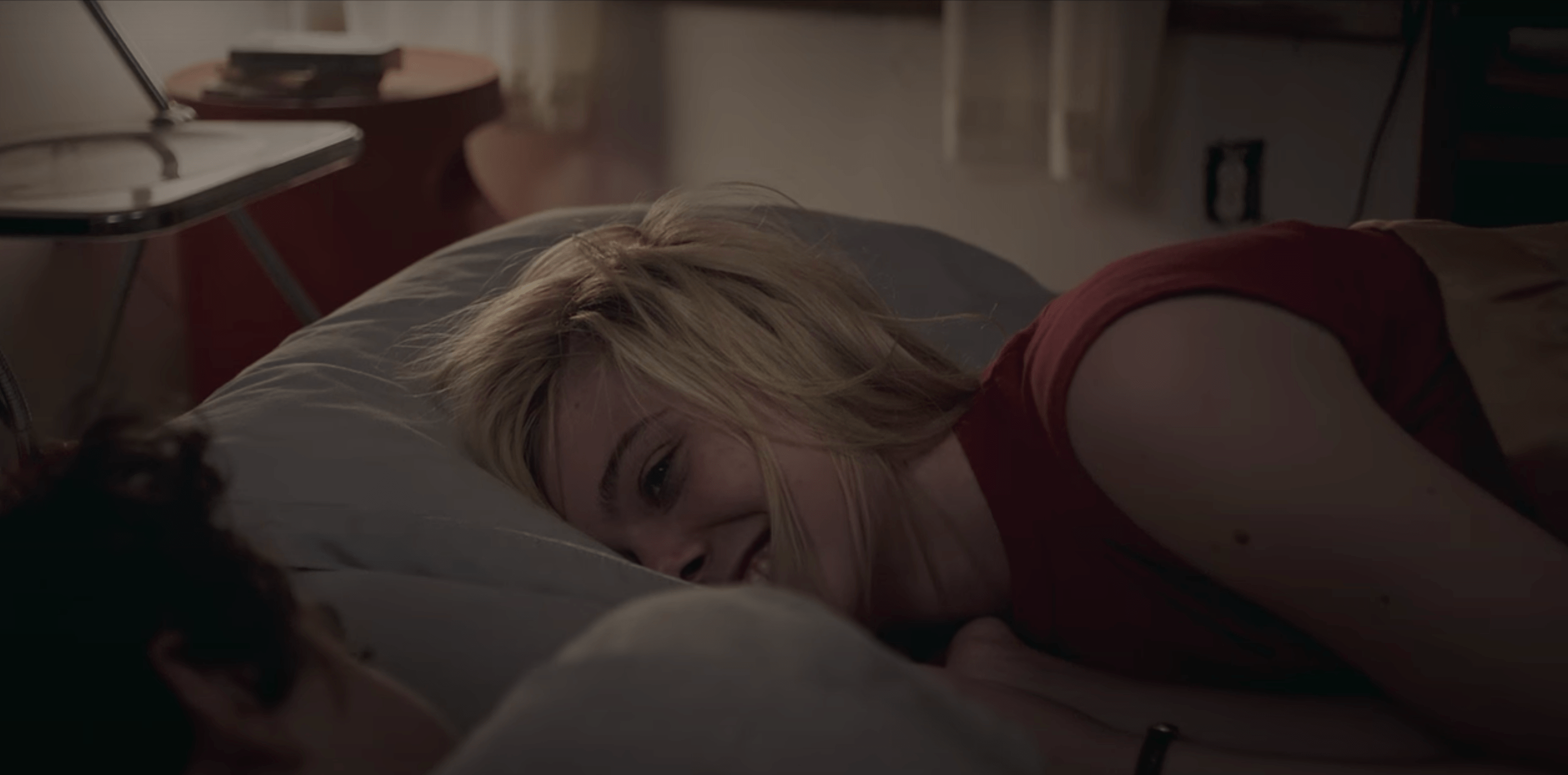

It's about Jamie who is fatherless and raised by a complicated mother (Bening’s Dorothea), a woman who has strong feelings about the direction of American culture, particularly when it comes to popular music. Like William, Jamie is influenced by a young and gorgeous rock-music enthusiast (Greta Gerwig) who becomes a big sister to him and helps him learn to be cool. Jamie’s also obsessed with his dreamgirl Julie (Elle Fanning) who chases "inappropriate" men but drives him insane by sleeping beside him and insisting he lock up his raging teen hormones. Every day, little by little, Julie breaks his heart anew.

Oh, and then — perhaps the clearest tribute to his inspiration — the filmmaker casts Billy Crudup as William, an irresponsible handyman who needs a good lecture from Jamie's mother. And even then, where most filmmakers would punish their elders with condescending characterization, Dorothea gets to score solid wisdom points over the handyman’s irresponsibility.

Perhaps I sound like I’m planning to dismiss 20th Century Women as derivative. But no — Mike Mills takes those remarkable strengths from Almost Famous — or, at the very least, he strikes remarkably similar notes — and composes from them something new and personal. Meandering observantly and patiently in his storytelling, gambling with a variety of styles, he gives a remarkable cast a lot of room to develop their characters.

I've never seen a stronger performance from Bening — and that’s saying something, as she’s been impressing me since I first saw The Grifters in 1990. She’s probably best-known for her turn in American Beauty, but here she’s portrayed with all of the compassion that that sneering and cynical movie lacked.

Gerwig is Gerwig, and that's a very good thing here — her Abbie, suffering from cervical cancer, is half in ruins, almost tragic, and utterly fascinating without ever stealing a scene (which Gerwig can easily do without trying).

As played by Fanning, Julie is a different kind of wise, a different kind of tragic — the sort of girl gives Jamie whispered lessons about sex through her cigarette smoke while never letting him kiss her. She’s learned about life from the men of all ages want to use and abuse her beauty, and she’ll easily surrender to mistreatment in hopes that sometimes she’ll get a taste of the real love she lacks.

And in the middle of these three icons of evolving feminism, Lucas Jade Zumann makes Jamie a remarkable mix of curiosity, confusion, frustration, and desire.

What a pleasure to see a film that isn't in any hurry; it just loves its messy and magnificent characters — all of them — and because of that, I do too.

In that sense, I can't help but wonder if Gerwig brought any of her experience on this film to her own Lady Bird. I sense some of this movie in that one, just as I hear echoes of Almost Famous all the way through this: great art inspiring great art, the greatness in all three being defined by their loving hearts and their courageous imaginations.

Onward's Frivolous Fantasy

"Onward!"

That one word might sum up the attitude of many of my students about Lockdown Season. They're ready to be done with these limitations. And yet they understand the gravity of the situation, so they're trying to be responsible. Maybe that's why movies that offer escape into new worlds are particularly appealing right now.

I feel out-of-step with them on this point: I'm feeling less interested in big, loud, exciting fantasy movies and more interested in films that quiet my anxious and weary mind. I'm not throwing shade here — I love great fantasy as much as anyone, and I write fantasy novels. It's just that I'm craving contemplation more than clamor, and the weariness that comes from monitoring the crisis all around me makes it more difficult for me to be caught up in the Spectacular.

Nevertheless, since my childhood immersed me in Disney and my adulthood made me a fan of Pixar, I quickly made time to catch Onward. I've seen every Pixar movie — with the exception of Cars 3 (the second one was awful and the third one couldn't hold my attention). And several rate among my all-time favorite films, so I'm not about to give up on them now.

So, why has it taken me several weeks to write about Onward?

Two reasons, I think: First — I was disappointed with the film. It's so busy juggling ideas that it never settles on any of those ideas with enough attention to make it meaningful. And, second — I found myself dreading the work of writing about what has become a very tired subject: the comparing and contrasting a new Pixar movie with past Pixar movies.

The clarifying power of these unnerving pandemic months is not only making my time watching movies more meaningful — it is giving me a stronger sense of what, when it comes to movies, is worth talking about... and what isn't.

It seems like every conversation I've had about Pixar movies since the release of Cars 2 in 2011 has been about whether or not the Glory Days of Pixar are over, whether or not the studio's filmmakers are sustaining the high standard of their early films like Toy Story, Finding Nemo, The Incredibles, Toy Story 2. Almost every discussion I have after seeing a new Pixar movie devolves into whether or not the latest film is worthy of being on a list with the animation house's masterpieces. Will they ever deliver something as good as WALL-E again? Was The Good Dinosaur evidence that they've "lost their touch"? Were we wrong to wish for Brad Bird to cook up a sequel to The Incredibles? Was Inside Out just a momentary revival of That Old Pixar Magic?

Come on.

At this point it should be clear: Pixar movies are still likely to be great, and even when they're not, they're extremely likely to be substantially better than almost everything we see from any other animation house. Of their last seven releases, Inside Out, Coco, and Toy Story 4 have all been huge with both critics and general audiences alike, and they have reputations of being well worth multiple viewings. I love them all. The other four? I enjoyed plenty about all of them.

Anyway... enough.

These conversations about comparison eat up a lot of valuable time and attention that we could be giving to the movies itself. And trying to shake that habit is clearly eating up the time and space I have for this review. What other movie studio inspires such a constant and narrow focus on ranking their releases?

Let's consider what really matters: Vision. Artistry. Meaning.

Okay? Let's put the fuss behind us. Onward.

Literally... Onward.

Now available on Disney+ and streaming platforms everywhere, Onward — the new film from Monsters University director Scanlon and his co-writers Jason Headley and Keith Bunin — is Pixar's first venture into the territory of conventional fantasy tropes.

You might argue that 2012's Brave inhabits fantasy territory, and that's a fair claim — but I'd call Brave a film rooted in fairy tale traditions like the Brothers Grimm and Hans Christian Andersen, which is not the genre I mean when I say "fantasy." (If you search for "Brenda Chapman" and "feminist fairy tale," "Grimm," and "Andersen," and you'll find claims that Chapman, Brave's original director and storyteller, agrees.) To clarify terms, let me say that "conventional fantasy" is, in my estimation, the heavily traveled storytelling territory that involves variations on longstanding types and tropes like elves, dwarves, trolls, goblins, and dragons. The stories tend to be about epic quests and struggles over talismans. Tangled is fairy tale — The Hobbit and Harry Potter are fantasy.

And Onward is... a goofy, energetic, but dispiritingly derivative and uninspired fantasy.

What inspiration drove these storytellers to abandon Pixar's tendency to dream up new worlds and play around instead with these tired tropes?

I'm disappointed to find out that Pixar's take on elves, goblins, centaurs, unicorns, dragons, and the other usual fantasy-world suspects is so consistently unremarkable, so focused on wink-wink pop-culture punchlines, so... forgettable. If this had come out in the early '90s, before advances in special effects started making fantasy films commonplace, it might have felt fresh and edgy. As it is, it feels like a pilot episode of a Disney+ TV series designed to mildly amuse D&D and Magic players and distract folks who like Netflix's far-superior Disenchanted. The movie seems to think it will strike us as clever and surprising. Instead, it feels like the filmmakers went with all of their first ideas rather than a discerning selection of their best ideas. (Ha ha! Unicorns are pests in this world! Who'd-a thunk it? Hilarious!) There's something about the character design, the voices, and the personality here that feels ... Dreamworks-y. And that isn't a compliment. In fact, it feels positively sub-Shrek-ian.

And the story really isn't particularly exciting or interesting: Two elf brothers — Ian and Barley Lightfoot, unremarkable characters voiced unremarkably by go-to celebrities Chris Pratt and Tom Holland — one easily annoyed and one annoying, live at home with their mom and miss their dead dad. They don't get along. What will bring them together to care understand and care about each other? Ian will experiment with a magical spell that will help them connect with their father in the Great Beyond. (Since audiences loved Coco's take on the living visiting the dead, why not spin it around and bring the dead into the land of the living?)

It's an old saying among artists: If you're going to steal, steal from the best. Onward takes what some will call "inspiration" from, of all things, Weekend at Bernie's. (Really? Really?) When ordinary Ian's magical spell short-circuits the first time, bringing dad only halfway back, he will "half" to team up with his obnoxious and overbearing younger brother Barley and succeed in a road trip to find a magic thingmabob in order to finish what he started. Sure, Dad's Lower Half will be along for the ride, not doing much more than kicking (pun intended) occasional life into the proceedings. And, of course, what they need will be guarded by a big scary monster.

Since the movie only half-captures my imagination, I'm left half-heartedly asking questions about it's half-baked ideas. If the elf brothers have half a chance of resurrecting their dad – even by half — shouldn't their mom be twice as excited about the prospect than she is here? Why does she seem primarily concerned about getting her sons out of trouble, and relatively unmoved by the possibility that her husband might hold her again?

And why does a character as secondary — third-ary? — as the Manticore (Octavia Butler, for some reason) steal the show and become the most engaging personality in the film?

Argh. Can you feel it? That familiar pressure to fall back on the Easiest Take — that this film just doesn't live up to the standards of even middle-of-the-pack Pixar work? That it does more to inspire questions about what happened behind the scenes of this production than it does to renew our enthusiasm about the team that surpassed Disney's standards so spectacularly that Disney surrendered them the controls?

No, no, no — I must resist. Onward!

Instead of assessing this by holding it up against other Pixar films, I'll compare this to something else: Spielberg's Ready Player One.

Ready Player One is an honest-to-goodness Steven Spielberg adventure film — a rare and precious event — that, alas, only occasionally shows glimmers of Spielberg's innovative genius. Like Onward, it's a movie about how the best days of the Imagination are behind us, but we can still recover some of that magic if we... what? Revel in escapist nostalgia? Give up on vision and mess around with the old ideas?

Something unfortunate has occurred when a Great Artist has to sort through toy boxes full of images and ideas that were inspired by past artists' best ideas — including his own — and pass off a mash-up as something daring and new. Ready Player One — which never impressed me as literature, although it has a host of passionate fans — proves to be a shaky scaffold on which Spielberg can hang cinematic ideas. It's a "More is More" strategy that collapses under its own weight. (Even its reanimation of iconic characters goes wrong: The Iron Giant shows up as... a weapon of mass destruction?) The movie is so busy cleverly mixing up pieces of the past that it assumes it is arriving at a powerfully emotional conclusion when, in fact, it's only delivering echoes of past emotional conclusions. Sure, it's playful enough to hold our attention, but it ends up having the lasting influence of an Instagram account made of memes that draw upon popular TV shows and movies.

Onward draws power from the always-appealing storyline of children trying to connect with their dead parents. It's not a bad idea. (A bazillion Harry Potter fans know what I'm talking about.) When such a story follows nuanced characters in a spirit of curiosity, it can lead us to memorable and moving experiences that inspire not only our hearts but our minds. It's the idea that made last year's ghost story Light From Light, from writer/director Paul Harrill, interesting and affecting. But here, in the busy-ness of Onward's hyperactive geek love, it only manages to stir the emotions by putting us through familiar paces, by reminding us of things we've seen and felt before. I'd be surprised to find any moviegoer who would testify that it's made some kind of lasting, meaningful impression.

I am, I admit, not the target audience for this one. Yes, I write fantasy novels, but I've never liked role-playing games or the genre's grab-bag of Spells For Any Occasion. So while this is probably speaking somebody's love language, it isn't speaking mine, and I can't fault it on that count.

But, as the Anything Can Happen-ness of Onward counteracts any sense of suspense, and as its most exciting set pieces follow far-too-familiar templates — good grief, one key sequence's reliance on the climax of Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade is a straightforward rip-off, not an homage — I find myself bored.

Steven Greydanus of Decent Films, whose take on family films almost always rings true to me, points to the film's failure with fantasy tropes, observing that "when it comes to Ian and Barley, there’s really no reason for them to be elves at all; nothing for them to discover about their elvish (or elfin) nature." But his most insightful take points to another problem, identifying Onward as the latest example of an unfortunate Pixar trend:

It’s not the subjects of Pixar’s recent films I resent — on the contrary. There should be more popular movies, including family films, celebrating average people who aren’t superheroes, superspies, Skywalkers, what have you.

The problem is that Pixar’s movies tend to play as metaphors for the creative rise and fall of Pixar itself. When someone says “Maybe this place isn’t as adventurous as it used to be,” it’s hard not to hear an echo of the filmmakers’ voices. Where Up looked up, Onward merely looks onward.

Beyond that meta-take, there's just not much meaning in Onward's mundane storytelling. It's relentless pattern of unremarkable crisis and easy resolution gets old fast. And that's driven by typical crisis-of-confidence stuff: "You can do it!" "No, I can't!" "Just believe!" "I can't! Oh, wait... you're right! If I believe, I can!" Even Disney's own Dumbo was better at this — because that's what the story was primarily about. And it's just a matter of time before the obligatory What We All Know Is Coming happens... just in the inevitable Nick of Time.

I was rooting for Onward all the way through, eager to find something in it that would take on a life of its own.

And, for a moment, one thing does. Surprisingly, it isn't a character: It's a vehicle. Finding inspiration in something as mundane as a flat tire, the boys' galloping road-trip van becomes the movie's high-point of cleverness. But this is a movie full of elves, magic, wizards, and dragons! And it's a story about brothers growing with a longing for the father they lost! Why, then, do I come away caring more about the van than I do about Ian, Barley, and their mother?

And after that great moment, there's still so much more movie to go before we end up with the boilerplate Music For Crying Happy Tears By and Hugs All Around. Yes, family is good. Yes, it's hard not to be moved by the idea of boys getting to re-connect with a father they barely knew. But in a world so busy with derivative distractions, a story about brotherly love isn't likely to make much of an impression... or make any kind of sense.

It's a shame that the filmmakers' efforts to have fun with their most promising idea — a character who is only halfway present — end up seeming so... half-assed.

Onward, then... to whatever Pixar is doing next. Let's hope it's more than half-inspired. I want Soul to be whole.

Catching Up With Cléo from 5 to 7

"Yea, though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death, I will fear no evil."

I make this vow from Psalm 23 every day. And then, within moments, I break it: Some form of dread triggers alarms, jarring me to feel anxious about my health, my job security, my future, my marriage, my loved ones, my neighbors, my country. I lose my perspective. I lose my faith. I lose my grip.

Alarms of this nature go off in Cleo's head early in Agnes Varda's French New Wave classic Cleo from 5 to 7. That's because she's just learned that she may be...

I'm sorry.

I need to pause mid-sentence and clarify some things.

I've promised you a film review. And I just can't manage it. Not yet. I need to tell you the context of this occasion.

It's difficult to justify the time and energy required for writing film reviews right now. Writing for me, like studying for my students, is more difficult than usual during a pandemic. That's probably obvious — you don't need me to point that out. And I don't mean to groan "Woe is me! Why won't people stop suffering so I can write?" This isn't about that.

But for readers who look back at this post in some distant, forgetful future, know this: As I try to tell you about a 1962 film about glamour, the Algerian war, feminism, and existentialism, other things are demanding my attention. And those pressures are influencing my experience of the movies I watch. I am seeing differently, thinking differently, writing differently because of these days of relentlessly dire tidings.

Imagine this scrolling like a Star Wars Opening Crawl across your screen:

In the spring of 2019, COVID-19 and the chaos it has unleashed are claiming thousands of lives every day: our lives, the lives of our loved ones, and the lives of strangers we're called to serve. It's not just a threat — it's a reality. For many of us, those losses have already begun, bringing shock, anger, and grief. Businesses are failing. Fortunes and futures are being lost. Kicking us while we're down, America's Narcissist-in-Chief is claiming "success" even as he silences truth-tellers — the doctors and scientists most qualified to help us. As he signs death sentences for thousands more, he does so to the cheers of his blind followers. His supporters and enablers don't seem to care that history will show how catastrophically they failed, how they bear responsibility for so many sick and dying around the world.

Meanwhile, as many of us fight back against our own self-destructively deceitful government, and as we dutifully wear masks in order to "protect and serve" high-risk populations, thousands more are falling into denial or conspiracy theories, mocking those who humbly take precautions, choosing reckless self-indulgence over Love's call for us to prioritize the care of our neighbors.

So much that once seemed reliable has become unstable. We are living in the beginnings of a long season of hardship, and we need to set our minds on the things that matter most.

Is this a tangent? A bait-and-switch? Did I offer a film review and then go on a rant?

Actually, no — I'm arguing that this might be the time for all of us to meditate on great art.

If art is just "entertainment," then why bother spending time with it in these circumstances? And why invest time in writing about it? Good questions. But if art can be a path to revelation, if it can capture our imaginations, inspire change, and "catch the conscience" of the observer, well... bring it on. We need it now.

As I track my friends on social media, some speak of turning to movies for "escape." That's great — if you need "escape," that suggests that something's imprisoning or oppressing you. But me? I'm finding that movies actually focus my attention. They tune up the instruments of my imagination, mind, and heart. And thus, they're intensifying everything right now, bringing into sharp focus so much of what is happening around me in "the real world": the trouble, the suffering, the questions, the uncertainties. Movies, like poetry, are reminding me of what really matters. Good movies, anyway. Whether it's a vision of love, suffering, absurdity, or hope, it all seems so immediate, so relevant, so essential.

It might be the time for us to attend to Agnes Varda, whose imagination was matched by her compassion. She has so much to offer us in a time like this.

Perhaps this is just the time for Cléo from 5 to 7.

So... is this going to be a film review after all?

Yes. But for me, film reviews are rarely just an occasion to post notes about how I was "entertained." They're opportunities to reconsider the meaning of life, and then to return to that life with insight and hope.

"Yea, though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death, I will fear no evil, for Love is with me."

That may, in fact, be as good a synopsis of Cléo from 5 to 7 as I can offer.

So here we go.

Cléo from 5 to 7 invites us into the emotional turmoil of a French pop singer who, in the midst of her popularity and material success, is shaken by the possibility that her recent biopsy will reveal cancer. This sudden apprehension of her own mortality spoils her ordinary revelry in her rise to fame and fortune: She's a glamorous star with a long line of rich suitors who fawn over her and make promises. She is gawked at — worshipped — wherever she goes. But who can enjoy such success if you know your days are numbered?

In its visually entrancing first hour, we follow Cleo (Corinne Marchand, radiant and funny) as she zigzags from one possible "escape" after another — dazzlingly choreographed scenes full of mirrors and window reflections, a world that represents her self-obsession and self-absorption, of appearances and illusions. But it's also a world that seems designed to condition her to believe that appearance is everything. "As long as I'm beautiful, I'm alive," she says, and the men cat-calling her seem to agree. At times she seems distracted and even annoyed by the constant attention of strangers. But when her fears agitate her, she'll walk into a busy cafe and set the jukebox to playing one of her songs as if eager for people to remind her of her own importance.

Everywhere she turns, she's encouraged to answer "I am!" as that fairy-tale curse whispers "Mirror, Mirror on the wall... who's the fairest...?"

The times you're living in determine the movie that you see.

And as I watched Cléo from 5 to 7 wrestling with her dread of a deadly diagnosis, I thought about how timely it seemed. Right now, it feels like society has split in two — there are those burdened by the sense that their world has been cursed with a terminal diagnosis, and there are those living in denial and carrying on as if they're someone invulnerable.

I also thought crowds — about proximity. Cancer isn't contagious, but the poisons of vanity and materialism are. And as Cléo moves down crowded Parisian sidewalks, meanders through crowded restaurants, rides on crowded streetcars, I couldn't help but squirm. Death can visit us as an insidious tumor swelling secretly within one person in a public place, quietly poisoning their bones. It can also travel on the air, in a breath or in a spoken word, from one person to thousands in a matter of minutes. It can fester in the fears that come when a person has faith only in themselves.

In a world of such dire threats, how is one to sustain any kind of happiness — or ever discover joy? Cléo is trying and failing to find some kind of peace.

This was my first time seeing Cléo from 5 to 7 — so far, when it comes to the great Agnes Varda, I've only seen her documentaries. (The Gleaners and I is on my short list of all-time favorite films.) And this film is absolutely gorgeous. I understand why it's revered as a cinematic miracle Its cinematography and public-place choreography are constantly surprising and dizzyingly agile — somehow fantastical, poetic, and realistic all at once.

I ultimately enjoyed it more for its celebration of Paris more than for Marchand's glamorous turn.

I suspect that there was a lot of this film in director Wim Wenders's mind when he made Wings of Desire: So many moments drift past in which we hear snatches of intimate conversations between strangers, fleeting moments that enrich this portrait of a city that is both in love with itself and questioning (against in the historical context of the horrific Algerian War) whether everything is meaningless. One particular sequence involving a taxi driver had me wondering if it was Wenders's inspiration for the Wings of Desire episode in which a Berlin taxi driver philosophizes about how his world has become so subdivided that every person is their own "state," borders and passports and all. The reality of the war hangs over this Paris like a dark cloud, and I can feel Wenders watching and thinking "I need to do this, but with Berlin. And it needs to be even more intimate. I need to hear the thoughts of the lonely and isolated."

If it seems like I'm straying from the film's narrative focus, I am.

With this first viewing, I'm far more enchanted by the first hour than with the rest of the film, which seems to suggest that if Cléo will only take her eyes off of herself and her mortality and, like a good Parisian, fall in love then everything will be fine. The last act's meet-cute is fine, and the relationship it sparks has some potential. I understand the thematic significance of Cléo slowly warming to the smooth-talking sailor who ships out to another meaningless tour in the morning. There's truth in the fact that joy comes when we forget ourselves and turn our attention to others.

But that unexpected romance doesn't move me as much as the opening scenes of Cléo dashing about town with her charming and observant friend Dorothée (Dorothée Blanck). I found myself hoping that Varda might follow both women for the duration, allowing the contrast between Dorothée's evident contentment (and, yes, joy) and Cleo's vanity to develop further. The conclusion we get feels slight, too trite to serve as a meaningful resolution of the first hour's earnest questions about the corrosive effects of glamour and the emptiness of celebrity.

But take my disappointment with a grain of salt: This is just my first journey through a masterpiece, and I've learned from experience with Varda that her films need more than one look. I have so much confidence in Varda — her spirit of curiosity and compassion speaks to me unlike any other filmmaker's.

And so, I come away from Cléo from 5 to 7 thinking about how so many of my friends, so many of my fellow Americans, are discovering, like Cléo, that there's nothing like a reminder of our fragility and mortality to impress upon us what really matters.

I want to learn how to respond to death's daunting demonstrations with fearlessness and love. It will seem like foolishness to most of the world, but in my better moments, I really do believe it: I need not fear as I walk through the valley of the shadow of death.

And what is this season, if not a time when humankind as a global community passes through that valley? In the shadow, some will be taken, some will be left behind — as in the story of the Great Flood.

But this is not a story of the wicked being punished with death and the good being blessed with survival. The cosmos, I believe, belong to Love. And thus, Love will ultimately take every evil and refashion it toward an ultimate good: a grander story of redemption and rebirth. It's a bigger kind of Love than the sort one finds striking sparks with a stranger on a walk through the park in Paris. It's a Love that will bear us through and reveal that death was but a shadow in a valley, and that there was life in it, through it, and beyond it.

The unfathomable loss of lives to COVID-19 might make some decide that writing about movies is foolishness. But it is within the experience of art that I can catch a glimpse of how a season of hardship can become a testimony of truth. And truth is redemptive in all of its forms — whether it come expressed as an inspirational tale, as a blast of righteous anger, or as a heavy-hearted song of lament. When the world I'm in seems out of control and hurtling toward destruction, I can attend to a picture, a song, a symphony, or cinema, and find purpose in dissonance, even as the characters within it are unable to transcend their own story to discover the meaning evident to us.

As I walk through Paris, and through "the valley," with Cléo and Dorothée, I remember what matters, and I am saved.

Hard times are good times for Auralia's Colors

For the first time since its publication by WaterBrook Press in September 2007, I'm reading Auralia's Colors aloud in its entirety.

You are invited to join me in my journey back to the Expanse to retrace the steps of Auralia, the troublemaking gatherer of colors in the woods, as she makes her way into the troubled city of House Abascar. The people of House Abascar have been betrayed by false promises and robbed of colors, robbed of hope. But she has seen things in the world they have seen only in their dreams. And she wants to awaken them.

Here are the first four videos: an introduction and the first three chapters. To follow the whole reading, subscribe to my YouTube Channel.

https://youtu.be/1eefWX4VqvY

https://youtu.be/t_QefN303wU

https://youtu.be/BeaKCyiYMGs

https://youtu.be/psr_IhmZs1Q

In the midst of trouble and grief... a joyous day!

Here is the good news for all of humankind: Jesus is risen! And thus, the last shall be first, the poor shall be blessed, all lies will be exposed, all truth will be known, and all of us — every color, every nation, every tribe — will be reconciled as one family: the children of God.

Here are people from 40 countries, speaking in 25 languages, echoing the grand refrain, courtesy of my friends at The Rabbit Room. You may recognize some kindred spirits here, from N.T. Wright to Malcolm Guite, and many more besides!

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UBw99xQUSqk

Before Mulan... we had Whale Rider.

Here comes Disney's reinvention of Mulan, perhaps the studio's best effort yet to give girls an action hero they can believe in. The production looks suitably extravagant, and the cast — in a remarkable shift from the Disney white-washing norms — looks completely and properly Asian. These teasers they're giving us bring to mind the epics of Zhang Yimou (Hero, House of Flying Daggers) at his best.

But for me, the most promising aspect of the new Mulan is Disney's choice of director: Niki Caro.

But for me, the most promising aspect of the new Mulan is Disney's choice of director: Niki Caro.

After all, Caro has enthralled audiences before with the story of a young female hero who subverts the expectations of her people and overturns restrictive patriarchal traditions. It's been a while, but I'm glad for this excuse to revisit a film that impressed me when I saw it back in 2003, and that has had more staying power than I expected.

My ongoing appreciation for Whale Rider stems from two of the film's strengths: its haunting musical score (thank you, Lisa Gerrard) and its lead actress, whose performance remains vivid in my memory.

Back in 2003, Keisha Castle-Hughes wasn't part of a galaxy far, far away yet. (She'd play one of Princess Amidala's decoys in Star Wars: Episode Three — Revenge of the Sith.) She hadn't played the young virgin Mary traveling with newcomer Oscar Isaac's Joseph in 2006's The Nativity Story. She didn't need a George Lucas blockbuster or the endorsement of Christian leaders to catapult her into the spotlight.

All she needed was the right director, a woman who believed in her quiet power, and a character she could bring to life.

Castle-Hughes found those in Caro... and in the character of Pai.

Here's a flashback to my original review of Whale Rider...

... which I've revised slightly to correct some errors and some clumsy writing.

You know how these hero stories begin. A narrator intones a prologue in sonorous tones:

“In the old days, the land felt a great emptiness...." waiting to be filled up, waiting for someone to love it, waiting for a leader….”

And so, true to its mythic template, Whale Rider begins with those words. Writer and director Niki Caro raises a curtain of deep sea blue onto a pageant that acquaints us with a real-world culture conflict: The Maori of New Zealand, like so many peoples of the world, are deeply rooted in patriarchal traditions, and, as depicted here, they are struggling with how to survive in a changing world where restrictive gender roles are dissolving under the light and heat of wisdom.

But Caro's story, which so easily could feel stridently political and preachy, instead — with a fusion of a mystically evocative musical score, a thrilling performance by an irresistible actress, earnest and spirited work from an all-Maori supporting cast, and an extravagant backdrop of New Zealand coastline — catches us in that familiar but oh-so-reliable narrative net known as "A Hero Will Rise."

So, yes, this is a film that follows a time-tested formula. Whale Rider isn't interested in reinventing the shape of such a story; it's interested in achieving two other ends: revealing the glory of the Maori people and traditions, while also challenging those traditions by rewriting the rules on who gets to play particular roles.

What captures our attention about this portentous opening is this: It is, contrary to the ponderous norm, spoken by a young girl, her voice soft, as if she is reciting a sacred story to herself in reverence: “In the old days, the land felt a great emptiness, waiting to be filled up, waiting for someone to love it, waiting for a leader….”

With this fusion of the familiar and the unexpected, Caro — drawing from a novel by New Zealand writer Witi Ihimaera — lures us into an immersion in the rich, sensual qualities of present-day Maori culture, a remarkable tapestry of past and present. Koro (Rawiri Paratene), the Maori leader of the Ngati Konohi tribe, is looking for a young male that he can train up to succeed him. One of his sons has grown fat and lazy. The other, Porourangi (Cliff Curtis), has abandoned the tribe because of a terrible tragedy.

“There was no gladness when I was born,” our narrator, young Pai (newcomer Keisha Castle-Hughes) informs us. “My twin brother died and took our mother with him….” This excruciating event sends Porourangi running and leaves Koro without a son or a grandson to inherit his authority.

Since the tribe only looks to men for leadership, Koro grows angry when Pai herself starts showing all the signs of the traditional "crown prince." He refuses to consider her as an alternative. It is up to his wife, Nanny Flowers (Vicki Haughton), a wiser, gentler sort of leader, to cultivate Pai's virtues behind Koro's back until the time is right for her to claim what "the gods" have planned for her.

Some of the credit for the way this film transcends its own genre goes to Australian singer and composer Lisa Gerrard (famously of the band Dead Can Dance). The lush oceanic swells of her score are worth diving into on their own, for an immersive experience separate from the film itself. But here, her singular voice, backed by a sort of deep-sea angel choir, brings an appropriately mystical tone to the adventure.

But a good deal of credit also goes to Keisha Castle-Hughes, an astonishing young actress. Speaking lines that could so easily have sounded routine and uninspired, she brings young Pai to life a three-dimensionally human girl in whom we easily believe.

Stories of young heroes usually draw from a familiar set of action figures: the boy wide-eyed with wonder who somehow becomes the least interesting character in his own story; the snarky rebel who cleverly smacks down the nay-sayers; the humble servant who discovers a magical weapon and learns, like David with his slingshot, to slay giants. Whale Rider sets itself apart with Pai, who, at only 12 years old, is quiet, watchful, reluctant, and yet courageous. Like John Sayles’s charming modern folk tale The Secret of Roan Innish, Whale Rider follows its young female protagonist into a growing sense of her cultural heritage, family secrets, and, of course, a prophecy. And like Phillip Noyce’s Rabbit-Proof Fence, the film treats its spirited heroine like a grownup, giving her an emotional complexity and a quiet intuitive nature that makes her seem more mature than anyone around her.

As she grows in knowledge and courage, Pai suffers a series of trials and rejections that seem familiar, recalling even such predictable audience favorites as The Karate Kid. But the film's last hour takes on an enchanting quality. As the legends that Pai has always been taught seem to come to life around her, she claims her connection to the tribe's legendary hero, Paikea, the boy who traveled across the ocean on the back of a whale. Our anticipation rises as we wonder what she will do to show such a connection. The revelation, when it comes, is something so ambitious that I never would have dreamed it would work. But it does, and the film's conclusion is surprisingly satisfying.

By the end of the film, Pai has humbled the willful grownups around her and won over even the cliché-weary cynics in the audience. In fact, her monologue near the end of the film still strikes me like a powerful wave, washing away the last of my resistance. I'm shaken when the scene is over — ready to follow this hero and fight for her people's future.

Until that moment, I'm not completely won over. After the film's startling beginning, I retreat at times into a state of detached observation, recognizing this as a story I have been told many times before. I'm weary of "Behold the Chosen One!" narratives. And I'm easily aggravated by big, one-note performances that give us Types instead of Human Beings, like the stuff of mediocre, formulaic television. Formulas are not a bad thing: they're formulas because they are founded in time-tested truths about human nature and history.

But when those patterns are not played with particularity, passion, and evident love, they become stale and obvious. A performance as specific and subtle as Castle-Hughes's makes us forget where the formula leads, captivating us with the immediacy and impact of real life. She stands out among this expressive cast by her silence, her patience. She is the still point, which in the flamboyance of her community rings out like a shout.

A couple of things linger with me as setbacks to an otherwise enthralling film.

We're told that Koro has his hopes for succession set on his grandson because his own sons have been disappointments to him. Pai's father Porourangi, who might have followed in his father's footsteps, is portrayed as a noble man with honorable ambitions who, suffering a grievous loss, responds by leaving home to pursue a dream rather than staying to fulfill the plans of his father and his people.

We can empathize with his grief and his need to remove himself. But the film asks us to easily absolve him for leaving his daughter behind. The loss of a wife and a son justifies him in abandoning his daughter? This decision isn't given enough attention, and too little attention is given to Porourangi's reunion with her. While the grandfather's disregard for his granddaughter is demonized, the father's failure is quickly absolved. I'm not sure Porourangi deserve the admiring treatment the film gives him.

I was also confused by the Maori reverence for their tribal traditions. Threatened by diminishing numbers and increasing cultural distractions (drugs, alcohol, sports cars), Koro labors to inspire appreciation and reverence for the Maori rituals and culture. But he has only reluctant disciples.

I would have appreciated some more detailed exhibits of precisely what the traditions are and what they mean. Without that, I do not feel the loss that Koro feels as sharply as I might. I sense real warmth and integrity in the particularity of their greetings, their beliefs, their values. But watching a bunch of boys bat at each other with sticks in Maori martial arts training does not make me cry out “Preserve their heritage!”

Thus, Whale Rider works for me best an immersive aesthetic experience, and as the story of one young girl's triumph in humbling her elders and gaining respect. In this case, it succeeds enough earn it my hearty recommendation.

Vagabond (1985)

A strange marriage of formal playfulness and intensely earnest Empathy Cinema storytelling, Agnes Varda's 1985 film Vagabond gives us the feeling that we're watching a beautiful plane tree being cut down because it has a disease that will eventually kill it. There is no suspense about the ending: the opening shot of a body in a ditch tells us it all ends badly. There are only the questions of How and Why, and What Does It All Mean?

My tree metaphor, as you know if you've seen the movie, is from the film itself.

We follow Mona — our abused, persecuted, neglected, and self-abused vagrant zigzagging her way around French territories that never show up on tourism postcards – through a variety of encounters with people who are either dismissive, abusive, or vaguely charitable people.

In one memorable sequence, she rides around with an agronomist who is studying diseased plane trees. The woman observes her with curiosity, almost entertained by this human wreckage who eagerly consumes any food or drink she's given. She's studying plane tree disease, she says, but she's not seeking to cure it.

(It's even more interesting how Varda emphasizes that the fungal disease killing the trees came over from America on shipping pallets and crates made of diseased wood — a rich metaphor in itself that could apply to Mona in a variety of ways. Are the corruptions of Western capitalism at work in what's killing her?)

Is the agronomist really interested in helping Mona? No, of course not. Few who encounter her really do want to save her, and those that do learn that it's going to be much more difficult and costly than they thought.

Drawing extraordinary and unnervingly convincing work from actress Sandrine Bonnaire, Varda has sculpted — and I say sculpted rather than painted for how three-dimensional Mona becomes — a character failed by humankind at every turn, and that includes herself. Bonnaire is fearlessly committed to every harsh turn in this distinctive wanderer's journey, creating a completely convincing character through terror, desperation, bitterness, and occasional glimmers of joy.

But she's not the whole show: Ever ruggedly real supporting character is as distinctive as she is, many played by non-professional actors found by Varda in the places where the movie took her. Among this gallery are some characters who express not only pity for Mona and shame for how they fell short of saving her, but also some who express admiration — particularly women who envy her freedom.

As a big fan of Varda's documentaries, I had no trouble recognizing her passions and improvisational sensibilities here. (I can't help but wonder if she means for the sophisticated academic to be a self-effacing reference to herself, since she would, in 2000's The Gleaners and I, speak with similar curiosity and fascination about a bunch of similarly beleaguered and desperate young people living on the street.)

But I was surprised at how, in spite of the formal inventiveness, this came to feel very preachy, like a long and repetitive re-write of the parable of the good Samaritan, in which even the fleeting flares of generosity in those who encounter Mona give way, person by person, to fear, impatience, or — in the most difficult scenes — exploitative impulses.

I will have to give this one time. Perhaps as I continue to discover the poetry in the seeming chaos, I will warm to what Varda has done here. But due to their overbearing agendas to Make Me Care, most films that aim to inspire empathy with this narrative of a human pinball (that is, a protagonist who crashes into one calamity after another until they stumble into a pit) end up... leaving me cold — no Vagabond pun intended.*

*But I won't say I wasn't pleased by the pun when I stumbled onto it.

The Kid Who Would Be King (2019)

Like a decent Excalibur, a good King Arthur movie needs an edge. Maybe it was all those years that it lay half-buried in stone, but this sword just doesn't cut it.

Add The Kid Who Would Be King to the mountain of "Fantasy For Kids" films that have imagined their young-white-male protagonist as the most blandly uninspiring fellow imaginable. Take the situation from bad to worse by giving the role to a young actor whose name, we might guess, they pulled from a King Arthur Coloring Context drawing. That this fellow scored the lead role of Alexander, a middle-schooler who becomes the next King Arthur, makes me immediately suspicious that he's related to Somebody Important who wants to bump their kid to the front of the Child Actor Line. (Checks the kid-actor's lineage and... yep, that could well be the case.) I'll come around to an apology to Louis Ashbourne Serkis later — I don't want his talented father mad at me — but whether you point to the actor, the script, or the director... something's failing to click here.

It doesn't help that he's surrounded by a supporting cast of school kids who are all more charismatic than him — nor does it help that, in spite of that, none of them would have been strong enough to earn a place at table in Hogwarts or in Frodo's fellowship. Points to Dean Chaumoo for giving Alexander's predictably portly sidekick Bedders some measure of charm. Promote him to the lead role, and the film would be markedly improved. (I'll give proper credit to the Magical Mentor who joins the team later.) But mostly this film serves to make me appreciate the vim and vigor of that Harry Potter freshman class even more.

Pit these bargain-basement British Goonies against the wicked witch Morgana, an impressively frightening fire-breathing chimera who seems to represent both the Spirit of Brexit and adolescent fears of sex (or something), and cast Rebecca Ferguson in a role, and you stand a chance of spicing things up. It's not a bad bit of casting, and points to the costume designers and concept artists for making Morgana sufficiently creepy. (Her fondness for wearing long curtains of root-vegetables reminds me a bit of some monsters in my own fantasy novels.) But the film gives Ferguson nothing particularly interesting to say, in those moments when we see an actress instead of a CGI monster, except for generic threats and rants from the Box of Standard Fantasy Villain Dialogue.

That she leads an army of video-game skeleton zombies on skeleton horseback — minions that have far less personality than, well... Minions — just amplifies an ongoing sense of missed opportunities.

I wish I could have what they're having. I'm sure my response will provoke some laments about how I've lost my ability to "be a kid" again (but I would point to my enthusiasm for excellence in entertainment for children in answer). But I'm hearing what The AV Club's Ignatiy Vishnevetsky, who says:

Authentic Arthur legend is awesomely weird and loopy, idealized and mystical. But The Kid Who Would Be King mostly goes through the motions of a one-size-fits-all quest....

...Cornish, for better and worse, is trying to have it both ways, offering both a sanitized fantasy about a boy whisked into a world of knights and magic, and a commentary on the same.

Okay — I do agree with the critical consensus who have hailed young Angus Imrie, playing Young Merlin, as the film's MVP. While the film positions him as the next Patrick Stewart, he strikes me as much more likely to be the next Hugh Laurie, Stephen Merchant, or even Richard E. Grant. With a bit of Davie Bowie Other-ness (and limbs so elongated that he'd be the taffy-stretch ideal for the role of Plastic-Man), Imrie effortlessly steals every moment he's in — from his bare-assed entrance as a kinder, gentler Terminator to the percussive spell-casting in which his arms become a circus sideshow. Without Imrie, this film would, unlike its zombie minions, stay stuck in the muck of the... peat?

Anyway, I'm running out of the will to say more, partly because I''m burned out on franchises and franchise-wannabes that just pour money into a Wal-mart Cake Mold hoping to become the Next Big Thing. (There's a massive loose end at the conclusion here, a character they keep promising us who never appears, and who you can half-expect to appear as an end-credits stinger saying, "I'm ready for Episode Two.") I expected better from Joe Cornish, whose Attack the Block remains a recklessly vivid reminder of how a great cast, a script full of firecrackers, and a judicious use of special effects can be worth more than a dozen blockbusters. I'm so grateful for that film, which showed us how good young John Boyega could be (before Star Wars showed us how easily such talent can be squandered).

But so many friends of mine seemed really excited about this that I'm wondering what I missed. Okay — so it has some admirable cast diversity and some lines about hope in an age that lacks any meaningful leadership. It's good to here a voice of common sense from England, feeble as it may be. But if you're going to hold up what the film itself calls "the LEGO mini-figure boy" minus any of the LEGO-movie personality and try to convince me that this is the next King Arthur, I'm sorry, but I'm getting plenty of that from the current stream of dispiriting Democratic campaign ads. It's a bad look to organize a Round Table of quirky cultural diversity around just another Bland White Hero and call it "a King Arthur for a Better World." Instead of inspiring hope, it bumps it further out of reach.

To the cast: Sorry, kids, if I'm sounding cranky and mean. It's not really your fault. Maybe you just needed a better script so I could've appreciated your potential as Knights of the Drop-Leaf Table.

Let the Corpses Tan (2019)

In a case of spectacular style over brain-splatter substance, Let the Corpses Tan delivers so many surprises so fast that I found myself wondering, only five minutes in, if directors Hélène Cattet and Bruno Forzani could sustain that level of ingenuity through the whole film.

Much to my amazement, they do. If you're a student of film editing or screenwriting, you're going to have fun studying this mash-up of spaghetti Westerns, grindhouse flicks, and Italian giallos...

... that is, if you can stomach the violence.

I couldn't.

After hearing some enthusiasm from reliable critics in 2018, I finally sat down to watch Let the Corpses Tan this weekend when I stumbled onto a DVD at the local public library. I hadn't planned on making time for a movie, but my curiosity got the better of me, and I decided to take a look at the first five minutes. Ninety-two minutes later, I was watching the end credits roll, trying to make sense of all I'd just seen.

The story... yeah, okay: As best as I can understand it, this is a movie about half-mad painter named Luce who lives in the ruins of a Catholic church — or, perhaps, a convent — on a sun-baked Italian island, where she splatters her canvases with violent expressions, incorporating, for example, bullet holes. She surrounds herself with glowering thugs — for inspiration, I suppose — who are distracted by their plots in progress. We watch some of them rob an armored car and then, as they throw bodies in the trunk and retreat back to the commune, they end up reluctantly giving a ride to desperate strangers: two women and a child.

Once the ruins are busy with unexpected guests, it's just a countdown until the newcomers discover the foul play, or until the cops arrive to investigate the robbery and the killings. We don't have to wait long. With the first gunshot, the game begins in earnest: a complicated shootout that runs through the afternoon, evening, and night, all the way to sunrise. The action moves so frantically, often doubling and tripling back to show us the same incident from different viewpoints, it's hard to sort out each character's connection to Luce's art, her sexual exhibitionism, or her past.

And then there's the allegorical overlay: a surrealistic spiritual warfare in which a woman is painted with gold and seemingly abused for the entertainment of unidentified male onlookers. A lot of this looks like found footage from late-60s exploitation films.

But I shouldn't invest too much time in a synopsis. Dizzying in its creativity, Let the Corpses Tan is too formally inventive to be suspenseful. Its characters barely register as anyone more complicated than the role-playing descriptions for a Clue game. It's a genre exercise par excellence, with Cattet and Forzani shifting pieces around a game board, and then finding the most invigorating shots, edits, and transitions to document their moves.

Good luck tracking all of the relationships, loyalty shifts, betrayals, and charades. It's as deliriously fast-paced as a Guy Ritchie film, but where Ritchie busies things with slow motion and digital effects, Cattet and Forzani prefer to make low-fi magic the old-fashioned way; their style is raw, rough-edged, and, in these hot climes, radiant with oversaturated colors. And, unlike Ritchie's films, which serve up plenty of gunplay but irresponsibly minimize carnage for the sake of crowdpleasing, this is irresponsible in its over-indulgence — it's unflinchingly bloody, insisting on extreme close-ups of guns shoved into open mouths and fired, recalling Nicolas Windig Refn's most graphic gore-gies. If we know what a movie loves by what it pays attention to, this movie love the destruction of human bodies. As with Tarantino's latest, I'm thrilled by the execution, but repulsed by the, um... executions.

Still, I gasped when I recognized Elina Löwensohn as Luce. I haven't seen her in many years. Her distinctive beauty charmed me in Nadja way back in 1994, and her face in close-up is still one of the most exquisitely interesting subjects in cinema.

And I cannot deny the genius of the architecture and editing. This is extraordinary, playful, relentlessly surprising cinema; it's easy to admire it, even if it troubles me as much as it dazzles me. Let me know when Cattet or Forzani come up with something new. I'll want to do my research, so I know whether to be there for opening day... or dive for cover.

El Sur (1983)

If I were studying psychology, I'd want to do a deep dive into this question: How is a person's belief about the existence and nature of God shaped by the presence and character of their father and mother?

I'm re-reading Chaim Potok's novel My Name is Asher Lev, and I'm particularly intrigued by the influence of young Asher's authoritative, judgmental, and yet often affectionate father Aryeh. A devout Hasidic Jew, Aryeh expresses furious disappointment in, frustration with, and condemnation of his son over his compulsion to grow as an artist. This stirs up a storm of emotions in Asher: fear, shame, self-hatred, and longing. And it greatly complicates his relationship with religious faith and his capacity to believe in a just and loving God.

This rings true. I have grown up with loving, faithful parents, and I often wonder if this has anything to do with why I have never suffered what is commonly called "a crisis of faith." I've had seasons in which I become impatient and frustrated with God's silence, but I have never experienced (that I can recall) a lapse of belief that God exists or deep doubts that God's name is anything but synonymous with love.

Along the same lines, I have watched so many friends suffer crises of faith, and in so many of those troubles it seems that those same individuals are grappling with fractures in their relationships with their parents. Quite specifically, friends whose fathers abandoned or were unfaithful to their mothers have seemed to struggle with the idea that God could be either loving, faithful, or just.

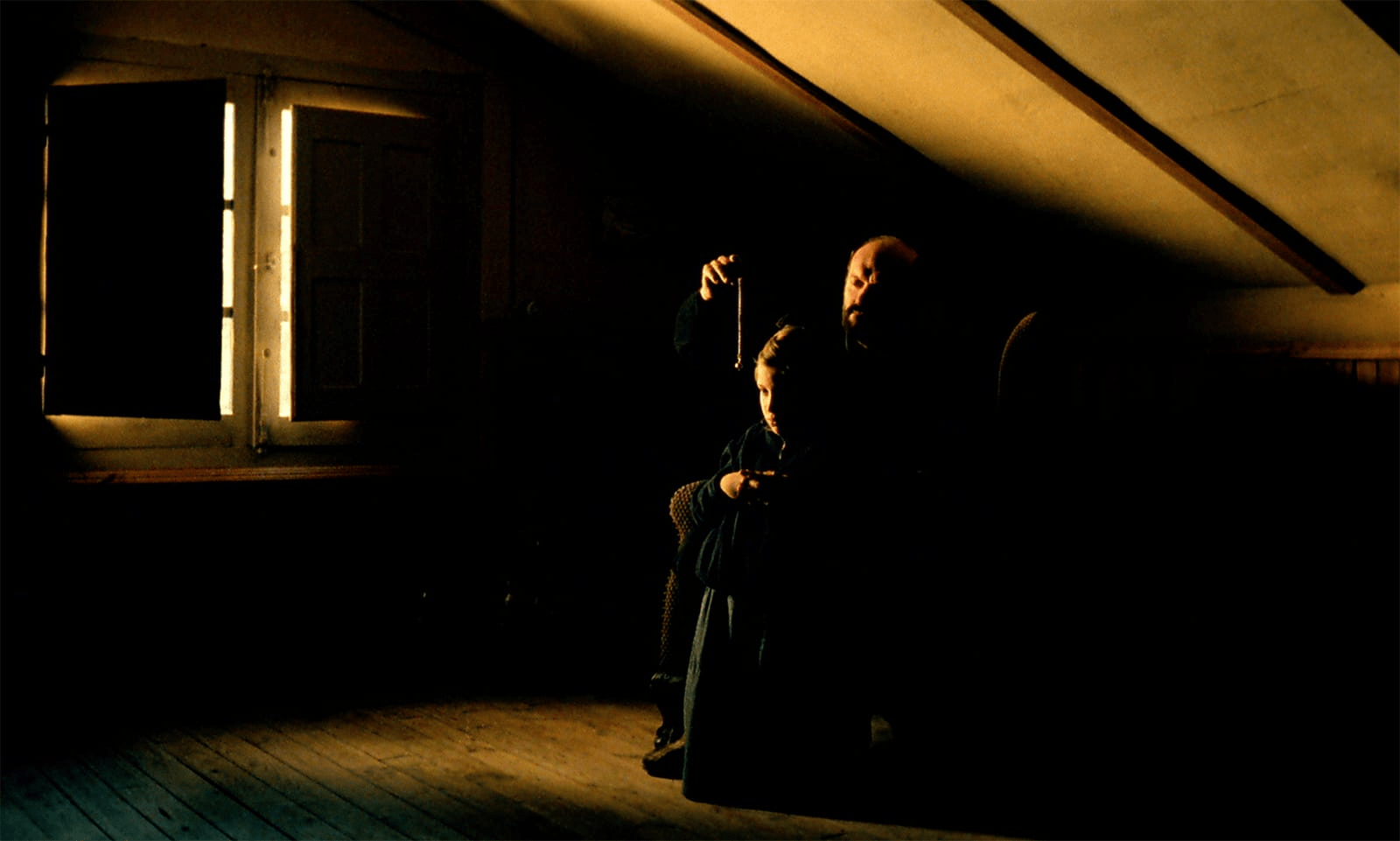

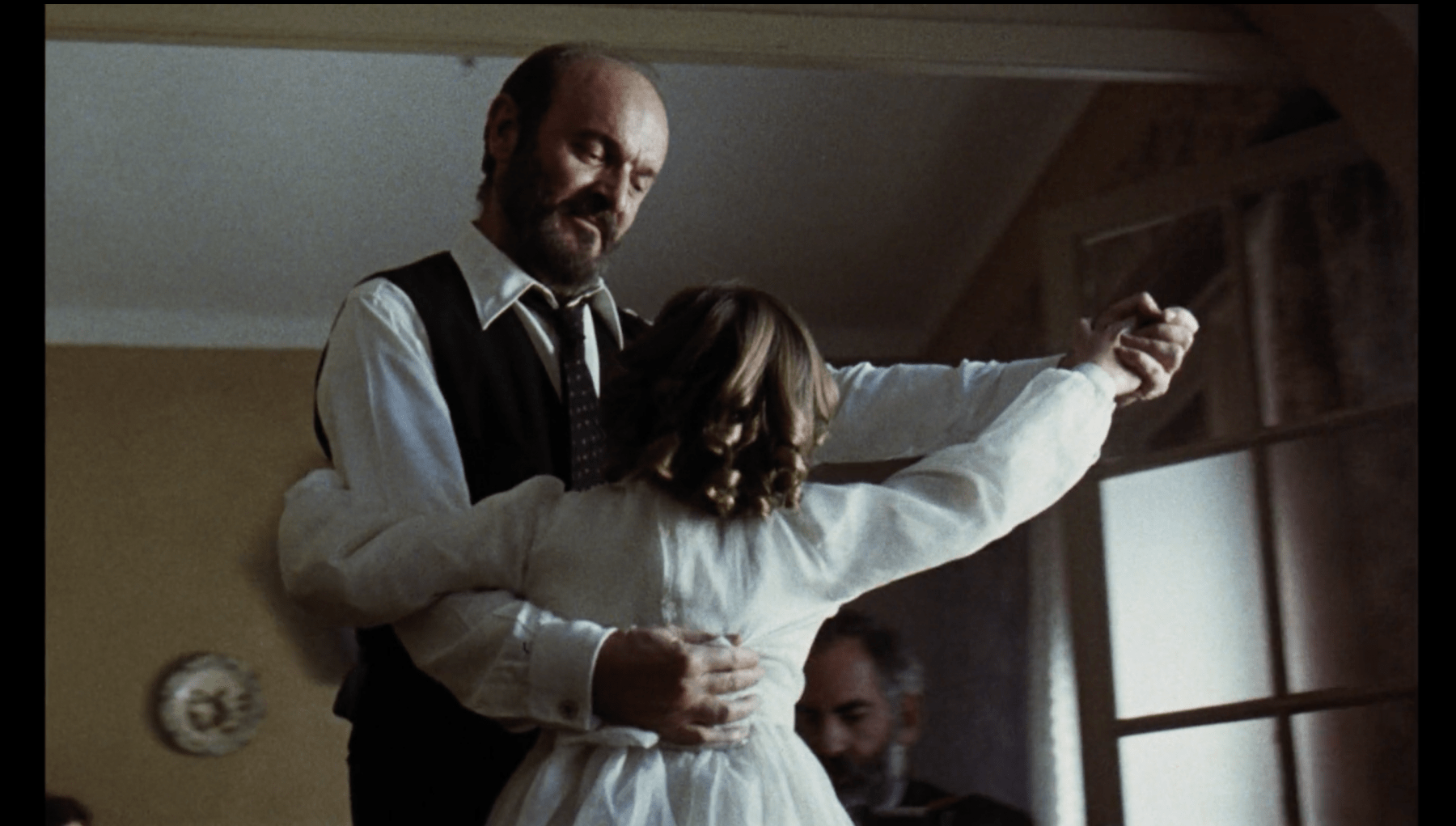

I thought about this a lot watching El Sur, director Victor Erice's intimate and visually enthralling drama about a girl growing up in northern Spain in the shadow of a loving but secretive father (Omero Antonutti).

The first half of the film focuses on Estrella when she is very young (played by Sonsoles Aranguren), fascinated with her father Agustín's isolated work in the upstairs of the family home: "experiments," her mother Julia says. But Estrella's enchantment is shaken when she discovers evidence that her father might have secrets, secrets tied to the south of Spain, secrets that would expose dishonesty... or worse. Then the film shifts to Estrella the teenager (played by Icíar Bollaín), who is skeptical of her father and intent on learning the whole story behind his disappearances. Clues that lead her to a movie theater in town, and the plot thickens.

There are just enough religious references — particularly the centrality of Estrella's First Communion — to start me thinking about theological implications of Estrella's relationship with her father. But the film's spirituality resides more in its subtle attention to visual beauty and a sense of mystery conveyed through composition. El Sur has some of the haunting qualities of a Terence Davies film, with a powerful motif of figures emerging from and disappearing into shadow. And there are meditative close-ups of both young actresses as Estrella that I suspect may have influenced Krzysztof Kieślowski's work with Irene Jacob in The Double Life of Veronique and Three Colors: Red.

This film also feels, strangely, like a prologue — an origin story for a woman who will embark on a quest full of discovery. Maybe I've seen too many series lately, but I was disappointed as I felt the conclusion of this 95-minute film approaching. I wanted to stay with Estrella and follow her as she set out to solve her father's mysteries beyond the familiar territory of her childhood.

That disappointment deepened when, after watching this film for the first time on Criterion's gorgeous blu-ray edition, I read about El Sur's history. What a bittersweet education! I was right to think that Erice's movie feels like a prologue: As you might know, but I've only just discovered, the movie was meant to be twice as long. The producer Elías Querejeta shut the project down at the 95-minute mark thinking that the film seemed complete, even though Erice had his heart set on filming the full (and apparently extraordinary) screenplay. I think a lot of artists have probably had nightmares as I have about just this kind of crisis — fears of passion projects being shut down halfway through. My heart goes out to Erice.

If I must treat El Sur as a complete work, then I must confess that I find it unjust to Estrella's mother Julia (Lola Cardona). She is so wronged by her husband Augustin, but her sufferings are treated as almost shrug-worthy here, while Augustin's suffering is given great attention, as are his charisma and gravitas.

Having said that, Augustin and Estrella become a father–daughter pairing for the ages. As Augustin, Omero Antonutti is quietly enigmatic. And, collaborating to play Estrella at two different ages, Sonsoles Aranguren and Icíar Bollaín give convincingly cohesive performances — the transition is as seamless as can be. They make me believe enough to ache for Estrella's feelings of betrayal and her desire to gain a mature understanding of her family's secret history.

I might imagine a second half in which we see whether she holds on to any of her family's cultural Catholicism after the painful turns in her view of her father's character. That first hour's emphasis on First Communion suggests that it would be right to revisit whether she carries any inklings of faith along with her into adulthood. Having lost faith in her father, is she still capable of turning to God for consolation and guidance? Or have the sins of the father wrought their ruinous consequences in the heart of his child? El Sur, this incomplete masterpiece, doesn't have room for any suggestion one way or the other.