Loma's "Don't Shy Away" asks us to delve and discover

"...Don’t Shy Away is an invitation. It honors the sacred space of uncertainty, acknowledging lingering darkness while trusting in the possibility that brighter, more brilliant worlds lie within reach." — Allison Hussey, Pitchfork

If you've ever walked alongside someone suffering from terminal cancer, and struggled to make meaning as the disease advanced, you have some sense of what the last five years have often felt like for me and for many other Americans. As toxic evils have erupted from subterranean reservoirs and spread in broad daylight — Christian Nationalism and white supremacy, for starters — corrupting and consuming so much that was vital and beautiful and life-giving, and as a pandemic has swept around the world like an Old Testament plague... times have become hard for just about everyone.

And times have become difficult in very particular ways for artists. Not worse, mind you — I don't mean to compare their challenges to those suffering direct hostility or ventilator-deathbed crises. I just mean that I'm seeing so many creative visionaries struggle to find their muses, as if they've been separated by social distancing. Creativity flourishes when artists can lose themselves in unselfconscious imagining. And dark times unsettle us, upset us, and make possibilities seem dim and distant. It's difficult to play. It's difficult to experiment, take risks, ask "What if?" — especially when you checking the skies, checking the headlines, checking your pulse. These days, a simple glance at my phone can drive me from surges of fear to feelings of helplessness, from helplessness to rage, from rage to grief, and, on a good day, from grief to prayers of lament and appeals for help... where I should have started in the first place.

As a writer, I should know that the dark times, though they inspire no feelings of gratitude, can become material. These days and nights can be the hard winters that prepare us to bloom in some future season. And those who have been driven underground, or who have withdrawn into themselves, might redeem the time by seek veins of gold there. As Sam Phillips sang, "When you're down / ... you find out what's down there."

But that doesn't mean it's easy — especially in the thick of things.

And yet, a spirit of interior excavation and opportunity is alive in the mind of lyricist Emily Cross and her bandmates Dan Duszynski and Jonathan Meiburg (of Shearwater) on their second album as the band Loma. And perhaps that's why this record — Don't Shy Away — is speaking so deeply to me.

Perhaps.

Or perhaps it's just that the sounds on this record are enthralling me with a rare power, sounds that remind me of records that shaped my imagination and worked their way into threads of my DNA during my formative years as a writer. I'm recalling symphonic art-rock records like Peter Gabriel's So and Us and Kate Bush's Hounds of Love and The Sensual World. Those are records that seem to rise up from soulful collaborations between human visionaries and a holy spirit, their poetry casting nets made of images around ideas that are otherwise impossible to harness. Don't Shy Away is dazzling me in a way no sequence of songs has for years, reminding me just how deeply I can fall in love with the full-album experience from a band at the peak of their powers.

Cross's softly haunting vocals — which remind me at times of Luluc's Zoë Randell, at times of Cat Power, at times of Cowboy Junkies' Margot Timmins — offer up her lyrics in a spirit of suggestion rather than insistence. And the images hum with thematic synergy, always moving half in mystery and half in wisdom, bringing something beautiful and true close but just out of reach so that I'm always reaching, always trying to capture them in words and falling just short.

Don't Shy Away is a celebration of redemption and discovery through imagination, but it isn't shiny or happy — it's a wilderness of surging and intertwining sounds, riven with scars, heavy with hardship, and yet flaring with unexpected blooms and colors. The hope is all the more inspiring for the darkness against which it glimmers. I emerge from every listen feeling grateful, as if I've learned to bring back precious stones from dangerous depths: diamonds of beauty and insight.

The album opens with a hushed testimony of finding hope in worlds within:

Stuck beneath the rock

I begin to see the beauty in it

I begin to see the hardness

And the function of it

That pressure, that obstruction becomes a canvas on which imagine possibilities: "I draw some little pictures on it / They are my world."

https://youtu.be/sCqHV6Vq1vQ

And then, in "Ocotillo," as if rising from tangled blankets and dark dreams, as if she has struck the rock and found its hidden reservoir, the singer blooms with strength and the sounds come blazing into color. That's appropriate, considering the song's namesake: a cactus-like plant that erupts with vivid red flowers in the desert. In the song, this plant is named alongside creosote, that dark and toxic substance that can be a fertile foundation. There is a sense of new life growing in the presence of suffering, life that will eventually tear free and tumble with the wind. And the song tumbles to a glorious finale, recalling Radiohead's "National Anthem," a riotous march of synths, guitars, bass, and horns.

https://youtu.be/oq5X2G5qKQI

In "Half Silences" — probably the closest thing to a single, with a strong Shearwater vibe (I'm guessing it's Meiburg's melody) — the singer turns against the flow of the culture of self-interest, self-promotion, and self-absorption, to discover reservoirs of life, creativity, and faith in paths of humility and unselfconsciousness:

When I remove myself

From the picture

When I reduce myself...

I generate light

Generate heat

Generate breathing

I forget myself

Forget my life

Remember believing

I never get used to your tongue...

https://youtu.be/_UwsP3ioiks

In "Elliptical Days," which spices up the sounds of Peter Gabriel's "The Rhythm of the Heat," Cross appeals to something — a creative force, an emotion, a vision — wanting to break free: "I hear you scratching all night / What do you need?" Then, in an echo of Leonard Cohen's assurance that our wounds and cavities are "how the light gets in," she sings of "Light gathering / fills the open places / bright batteries ... / in the open spaces." It reminds me of one of my favorite Suzanne Vega songs, "Rusted Pipe," which is about a resurrection of creativity: "Somewhere deep within / hear the creak that lets the tale begin...."

https://youtu.be/JkDXIcpQs2Q

"Thorn" turns an incidental, half-whispered clip from one of Cook's podcast monologues — something about a rose and a thorn — into a haunting choral chant that picks up where last album's transcendent closing track "Black Willow" left off. (And by the way, that's the song that enchanted the great Brian Eno and led to his collaboration on this record's similarly haunting final track: "Homing.")

https://youtu.be/PoMoo7nWXFQ

And in "Breaking Waves Like a Stone," another Peter Gabriel-esque synthesizer riff that strobes its way into a polyrhythmic anthem, Cross offers more meditations on the not-yet-known:

In a possible sound

In a possible time

There is work to be done

There is drag in the line....

She sounds like she might be reading David Lynch's book on creative inspiration: Catching the Big Fish. (And by the way, that bass line is the work of Jenn Wasner of Wye Oak, another band whose work may come to mind as you play this record again and again.)

https://youtu.be/gY-DfCFR7Fo

"Blue Rainbow" runs on an insistent low-note pulse like a Christopher Nolan film score wearing slippers. It stalks in and out of dissonance, while Cook leads us into ever more abstract and surreal territory:

I feel a pulse, back of my eyes

Blue rainbow

I went down catacombs

I thought it wasn't possible....

https://youtu.be/OlO0cleZq-g

Cross isn't kidding around in her earnest hope of finding beauty in dark places, as music journalist Mark Newton found when interviewing her for Daily Progress:

“I’ve always been interested and fascinated by death,” she said, explaining she isn’t driven by personal tragedy but rather a desire to make the dying process “as beautiful as birth is.”

She operates a nonmedical practice, Steady Waves End of Life Services — named for a Cross Record song — in Austin, where she helps families work their way through their emotions and the paperwork associated with death. She also tries to engage younger people. One way is through a “living funeral,” where each participant “dies,” is memorialized and then “comes back to life.”

Whatever you make of these endeavors (I tend to be skeptical of any celebration of death as a blessing), you will find it hard to deny that Cross's musical investigations of dark places are revealing new rays of light. This is not one of those bands risking danger for the sake of swagger or cool, nor delving into darkness for darkness's sake. These are earnest and ambitious quests to affirm that there is no abyss into which we can fall that we cannot find hope in the depths, running like subterranean rivers, ready to nourish new seeds.

I have no idea whether Cross has studied St. John of Chrysostom's The Dark Night of the Soul, but I haven't heard a record that sounds to me so much like a work of deep prayer in a long time — that kind of prayer we pray when we come to the end of our vocabulary and our religion and find a Holy Spirit waiting for us there, praying for us, praying in us, "with groanings too deep for words." By inviting us into communion in difficult places, Cross is finding sounds that I find heartening, increasing my sense of what is possible even now, while storms go on raging.

https://youtu.be/zoxKsSubtpk

November 7, 2020: Relief, Elation, and Gratitude

https://youtu.be/j8no814jH2U

It's Saturday, November 7, 2020.

And, as The Innocence Mission song goes, "I have not seen this day before."

I am standing above Waterfront Park in Edmonds, Washington, and the natural world seems to be feeling the same elation that I'm feeling.

I feel such gratitude, knowing that I have so much good company in the world — people who have endured the last few years with me, and spoken up for love, compassion, freedom, and justice. My own safety and security come largely due things beyond my control — advantages that I was born with due to the color of my skin. So I have no right to complain about anything that has been happening to me directly. But I have been heart-sickened by the rising hostility in this country toward more vulnerable populations around me. I am grieving over the betrayals of the Gospel I have seen among professing Christians who have given their support to compulsive liars, misogynists, and racists whose political agendas harm the poor, the sick, immigrants, refugees, and people whose skin is a different color from mine.

These are dark times, and many hardships lie ahead — consequences for the past few years of devastating and disgraceful behavior on the part of those entrusted with leadership in this nation.

But it is good to know that so many Americans recognized the damage being done, rejected the lies and the hatred that were a betrayal of America's ideals (many of which are inspired by the Gospel). It is good to see so many fighting for a future in which we can seek liberty and justice for all people — no matter their financial status, their language, their color, their gender, their sexual orientation, their country of origin, or their religion.

Every day, America can move toward that Gospel-inspired vision or away from it. We've been hurtling in the opposite direction for a while now. By distorting Christianity into Christian Nationalism, Americans have advertised a counterfeit Jesus, and made the Gospel seem toxic to many who need the comfort and hope Jesus offers. It feels good to feel that some have gained enough of a political advantage — by God's grace — to apply the brakes, slow our rapid descent into fascism and totalitarianism, prepare to turn the wheel, and chart a course for better things.

May God bless those efforts — not for my good, but for the good of my neighbors in need.

I post this as the first video in a new series of more personal posts at my website — LookingCloser.org — in hopes of expanding the range of subjects I explore there. I hope you've enjoyed the video at the top of this post — this glimpse of the glory that played out in front of me at the close of this beautiful day.

Four years ago this week, my wife Anne was rushed into five-and-a-half hours of emergency brain surgery and neurosurgeons — let's be clear, I'm talking about healthcare workers and scientists, some of the good Americans who have been consistently slandered by our outgoing President — saved her life by the grace of God.

This morning, Anne and I opened a bottle of champagne that we were given four years ago, soon after she arrived back home.

Today feels a little like the moment the neurosurgeon came to find me in the hospital lobby and told me that the surgery was successful and that Anne was alive and well. We have suffered many difficult days since then due to lingering effects of the brain tumor and the surgery. And more hard days lie ahead for many years to come. But she is alive and well.

So, yes... it seemed right to open that bottle this morning when we heard the good news.

And as we read more and more reactions to the conclusion of the 2020 election, I kept thinking of this moment in The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King. I know I wasn't alone in that.

https://youtu.be/FyzE9thQIPo

Grace and peace,

Jeffrey Overstreet

P.S.

Now I'm going to take part in that longstanding American tradition that celebrates all things good and true. I'm going to shop the the Barnes & Noble 50% Criterion Collection sale.

And by the way... if you want to hear some inspiring ideas, here are some great ones.

https://youtu.be/JdJ4x3lkdl4

Yes God Yes (2020)

[This post was originally titled "Caution: Raunchy Christian high school sex comedy may cause flashbacks!"]

I found Yes God Yes, a raunchy but sincere little indie comedy from writer-director Karen Maine (Obvious Child), streaming on Kanopy, and it was just the kind of mildly amusing distraction I needed to take my mind off of this grueling week of election results.

Yes God Yes follows the angst-addled journey of Alice (Natalia "Stranger Things" Dyer), a young Catholic high school student, from her first awkward and unexpected sexual awakening (during an encounter with internet porn) into a labyrinth of temptations, fantasies, fraught relationships, obscene rumors, humiliations, and — worst of all — righteous reprimands from condescending Christian adults. Unfortunately for moviegoers, once Alice is all hot and bothered by her impulses and her typical teenage relationship issues, it's easy to predict what she'll discover along the way that she can play as her trump card in the final showdown with her tormentor. Worse, it arrives in time at a disappointingly preachy little conclusion, one that feels far too simplistic for the questions raised by the film.

But I'll leave the details for you to discover.

Like Brian Dannelly's Saved! — a much, much funnier comedy similarly set in a Christian high school context of teenage hormones and horrors — Yes God Yes settles for taking very, very easy shots at private Christian schools and Jesus camps. I'm not saying either film is inaccurate in their jabs; I'm all too familiar with the ways in which Christian teens learn to lace their boasts and their cruelty with churchgoer vocabulary — I used to be a pro at that very thing. And I recognize these scenes as fun-house-mirror reflections of the world I grew up in from first grade through high school. But I can't quite tell, due to the film's fierce focus on religious legalism, if Maine has a personal axe to grind with Christians, or if this portrayal of Christian community is based solely on other media exaggerations, two steps removed from the real thing. It all feels a little too easy, like shooting Jesus-fish in a barrel.

Still, there are moments along the way when the movie warms with wisdom — wisdom that (like the wisdom in Saved!) could have been found in almost any other context of adolescence. It's not as much about cultural Catholicism as it thinks it is. This is a movie that I think most teens would find very "relatable" (to use a word very much in vogue with young adults). After all, who hasn't struggled through adolescence with problems of peer pressure and hormones? Who hasn't had to deal with condescending adults who turn out to be either ignorant, hypocritical, or both? On some level, Yes God Yes is also about the ways in which small communities, responding to fears about things they don't understand, establish dehumanizing methods of control. Change the context, change the culture, change the vocabulary, and you get almost the same movie.

Fortunately, Yes God Yes doesn't throw the Baby Jesus out with the Bathwater of Hypocrisy. I kept expecting an all-out condemnation of religion. But instead, Alice, like the protagonist of Saved!, discovers a meaningful distinction between the behaviors of "believers" in her evangelical bubble and the actual teachings of Jesus. But, then again, the movie isn't brave enough to take faith very seriously either, reducing Jesus (like Saved! does) to just another Nice Guy who recommends we all, I don't know... respect each other and stuff.

Oh well.

For what it's worth, while I cringe and laugh and nod at so many embarrassing evangelical-culture idiosyncrasies in this film, I'm left looking in vain for any awareness that earnest and rewarding explorations of faith also take place in these contexts. I experienced as much of the latter as the former during my K–12 Christian school journey in the '80s.

Sure, there was plenty of the cheap evangelical lingo I recognize in this film being thrown around those hallways. We had our "testimony" times in which high emotion was a sort of currency, a mark of authenticity. I felt the pressure to manufacture dramatic stories of sin and salvation to earn my Christian credibility points, just as Alice does here. Perhaps the film's most startlingly realistic flourish comes when the Jesus campers form a circle and their pastor introduces them to Peter Gabriel's "In Your Eyes," asking them to imagine that the eyes belong to God. Ouch, that hits a bit too close to home!

And yes, I remember it all too well: My classmates and I suffered the typical bewilderment of hormones, first dates, first kisses, rumors, gossip, and struggles to keep up with the "urban dictionary" of sex. Like Alice, I suffered through plenty of maddeningly uncomfortable situations in which adults who were anxious and uncertain about sexuality tried wrestling the forces of eros down into some hilariously clinical and pragmatic ceremony. While we were never told that an indiscretion would "send us to hell for all eternity" — I think that's the film's most laughable exaggeration here — we were certainly conditioned to expect nothing less than lifelong shame if we gave into our impulses before marriage.

Scared out of my wits by what I was feeling, I remember seeking out the counsel of a Baptist minister (my first girlfriend's father, actually), to ask for guidance on restraining sexual impulses. He looked at me gruffly and ended the conversation abruptly: "Adolescence. I survived it. You'll survive it. Everybody does." And that was that.

By the grace of God, the fraught territory of what the film calls "figuring out our shit" eventually became little more than amusing footnotes in a personal history, one with far more meaningful narratives playing out. The meaningful relationships I found among Christian school classmates and my extraordinary teachers deepened, and many continue for me more than 30 years later. Those friendships were forged in experiences of epiphany, belief, and wonder that planted the seeds for a fearless faith — the kind powerfully recommended by, you know, the actual Bible.

And speaking of The Bible, the greatest gift that my Christian high school teachers gave me was unconventionally thoughtful and sophisticated training in what the Bible is and how to read it. You won't see any curiosity in this film about such matters. But while so many professing Christians misguidedly treat the Christian Scriptures as some kind of Textbook or Law from which they can cherry-pick convenient verses that enable them to judge and control people who discomfort them — a practice Jesus strictly forbids — I was taught to read the Bible with close attention to context, to the genre of each passage, to the spirit of the teaching instead of the letter of the law. And so, the Bible remains for me a glorious revelation of storytelling, history, eyewitness testimony, letters, psychedelic visions, and poetry (erotic and otherwise). It's a collection of texts so deeply and artfully assembled around its primary revelation — the life and teachings of Jesus — that I rarely ever open it without being blessed. I got that from a private Christian school. And I'm so grateful for it.

It'd be interesting to see a movie that doesn't assume we have to escape religion in order to find meaningful lives — or even meaningful sex lives. Yes God Yes, like so many films that dismiss Christianity as a culture for shallow and suffering hypocrites, suggests that the enlightened will eventually escape religiosity into into the relief of worldly freedoms (represented by a lesbian motorcyclist with war stories about Catholicism, of course). By my lights, Alice is just letting her conscience be her guide in escaping a distortion of Christian community and arriving at something closer to true Christian freedom. I can hear one of my more legalistic teachers now: "What would Jesus think if he found you watching this movie?" And I know how I would answer her: I think Jesus would laugh in loving recognition at the ways human beings find their way, fumbling — as Sarah McLachlan would say — towards ecstasy.

SPU Voices: Overstreet on meeting movie stars, storytelling, teaching, and faith

This week on the Seattle Pacific University podcast Voices, host Amanda Stubbert interviews me about my experiences in film criticism, my encounters with movie stars, my life of storytelling, and my new adventures in teaching.

We had a great conversation, and I'm happy that I can now share it with you.

Here's a direct link to the episode, and you can access the main SPU Voices page with other episodes here.

New adventures in hi-fi: Check out the new Looking Closer podcast!

It seems inevitable: a Looking Closer podcast!

I've decided to celebrate my arrival at the half-century mark by launching a new series of Looking Closer recordings at Anchor.fm. This will give me an opportunity to build a library of episodes in which I share my enthusiasms for new movies, music and more; bring new perspective to subjects I've covered in past years here at the site; and host conversations with special guests.

The Looking Closer podcast will include a variety of episodes:

-

Cutaways:

Short, specific episodes of 15 minutes or less;

-

Tracking Shots:

Close looks approximately 30 minutes long; and

-

Master Shots:

Sweeping, epic episodes of more than 30 minutes.

Listen to the very first episode here!

In this introductory Master Shot episode, I give close attention to a dramatic turn at the climax of Ridley Scott's Blade Runner, and find there a vocabulary for why I started writing about movies in the first place... and why I'm compelled to launch this series.

Then, check out Episode Two!

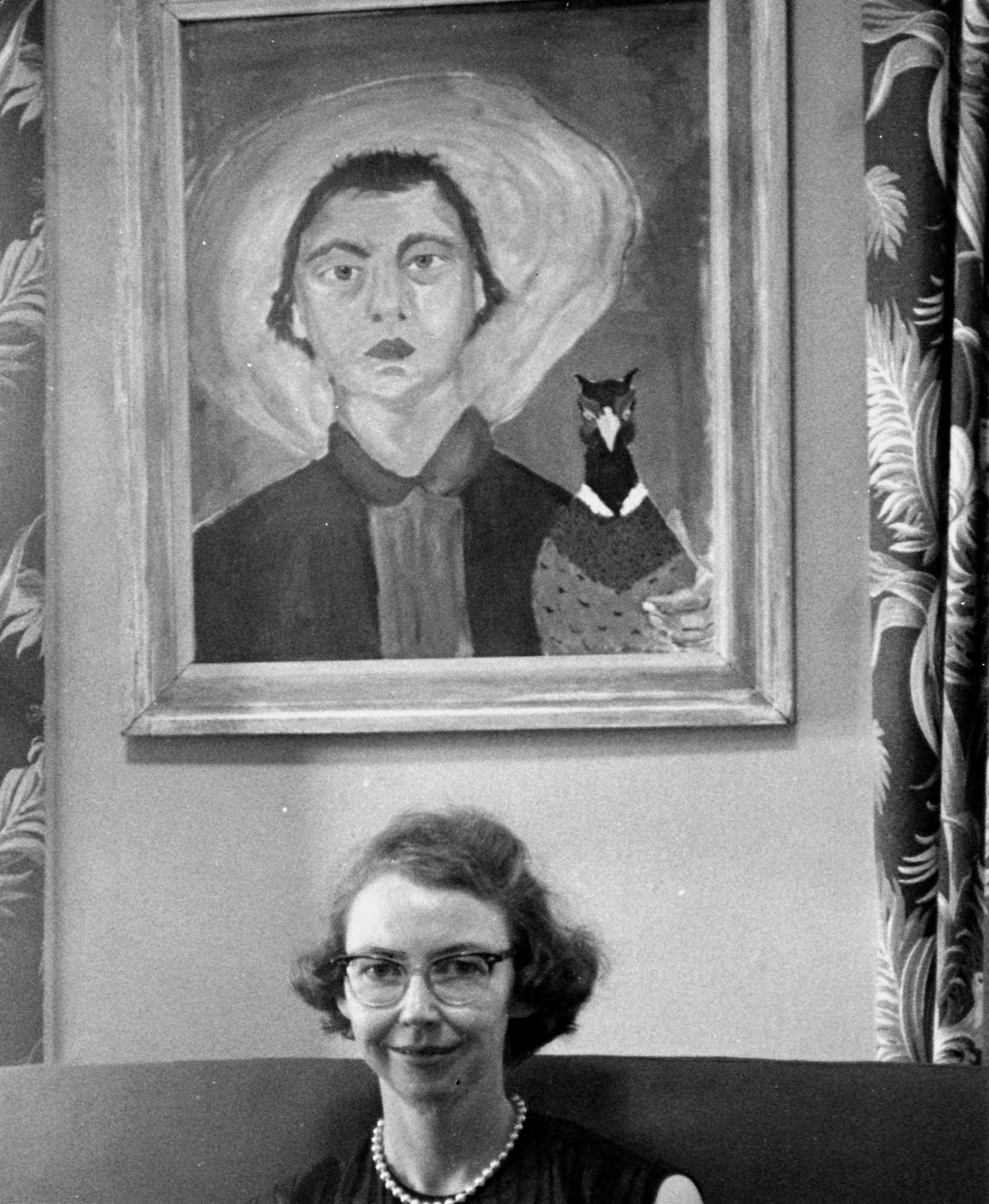

In this "Tracking Shot" episode (approximately 30 minutes), I look at the 2020 documentary "Flannery" and how it might be useful in a trending argument about the stories of Flannery O'Connor and how she represents African Americans in her stories.

Overstreet Archives: Séraphine (2008)

I'm delighted to publish, for the first time at Looking Closer, a piece I wrote for Image (archived here) about Martin Provost's extraordinary film Séraphine, which I rated my favorite film of 2008. (Since then, I've come to favor Olivier Assayas's Summer Hours, but it's almost a toss-up between the two.)

Even though he’s the dinner party’s special guest, a world-renowned art critic surrounded by giddy art enthusiasts, William Uhde looks bored. These chattering know-it-alls make him visibly uncomfortable. He’s probably hoping to escape back to his quiet apartment, and get back to his work—studying and writing about Picasso and other artists he helped bring to fame.

But then, everything changes. Uhde’s meandering gaze settles on a shadowed corner, and what he sees brings him out of his chair.

We know the treasure buried in that corner; earlier in the movie, we saw the lady of the manor stash her housekeeper’s amateur painting behind a chair. She probably worried that work by someone as uneducated, untrained, and common as her washerwoman would offend her honorable guest’s artistic sensibilities.

But Uhde is not discouraged to learn that the work was painted by a dowdy housecleaner called Séraphine Louis. That information only enhances the thrill of his discovery. In the following days, he strives to get to know this shy, unschooled painter and her work. He invests in the fulfillment of her potential, eager to share her gift with the world.

In time, she’ll become a legend: Séraphine of Senlis (1864-1942).

Watching Martin Provost’s extraordinary movie Séraphine, I felt Uhde’s excitement. For I too was enthralled, both by Séraphine’s art—this is the first time I’ve ever been astonished to tears by a painting—but also by the artist herself.

Played by Yolande Moreau in an exquisite performance, Séraphine is a formidable presence. She has a limited vocabulary and an awkward, corpulent figure. She trudges about in a sort of trance, surfacing only to request the materials she needs for her work or to acknowledge housekeeping instructions as she earns her keep.

Moreau brings the same complexity and texture to her performance that Provost finds in the materials of Séraphine’s world—the filthy floors she scrubs, the rumpled layers of her garments, the colors on her paint-smeared palettes, the chaos of the roaring trees that capture her attention. It hurts to see her suffer insults and loneliness by day, but the fever of Séraphine’s late-night, candle-lit artmaking is a joy to behold. She paints to serve the Virgin Mary, and whenever she nears completion of a work, she begins to sing in a holy ecstasy.

Provost’s film has few equals in depicting the dangerous territory between artistic inspiration and madness. As Séraphine stumbles through that country, Provost seems to suggest that her artistic exhilaration is closely related to poverty. Living in constant humiliation and exhaustion, she knows a powerful longing — one that she expresses in explosive designs. And when her work gains an audience, we realize that fame might uproot her from the soil that nourishes her particular vision.

I suspect that, to some degree, most artists will relate to Séraphine — the exhilaration of her immersive artistic experience, the lack of understanding in those around her. I know I did. Photographer Brett Weston said “Composition is the best way of seeing,” and just as Séraphine’s painting is for her a way of comprehending the wonders she has seen, so I come away from writing exhilarated but also humbled and sometimes troubled by what I’ve discovered.

Sometimes I pray for inspiration before I write, but is that so wise? We’re told that when we see God as he is, we’ll be changed at once. Until then, “the truth must” — as Emily Dickinson explained — “dazzle gradually.” Lightning-strike epiphanies can fracture fragile minds. William Blake and Vincent Van Gogh both knew a holy terror. In Carl Dreyer’s Ordet, the prophet rants from exposure to “too much Kierkegaard.”

Perhaps I should pray for safety instead of revelation.

Nevertheless, while I am moved by Yolande Moreau’s glorious performance as Séraphine, it’s Ulrich Tukur’s understated turn as William Uhde, the quiet German expatriate, that wins my heart. I’m more familiar with Uhde’s bliss — the joy of stumbling onto treasure in unexpected places — than I am with the artistic epiphanies that Séraphine experiences.

Life becomes exciting when we’re mindful that wonders may be hiding in plain sight. It’s why televisions across the nation tune in to Antiques Roadshow every week.

Sometimes, they’re small and personal. I could have sworn I heard the Hallelujah Chorus when I found a little-known film soundtrack on vinyl — unplayed, unopened — in the racks of Seattle’s labyrinthine Bop Street Records. (I smugly carried it home for only $8.99.)

Sometimes they’re more significant. One day in 1988, I noticed a troubled high-school classmate scribbling, and I asked what she was writing. She shared a sheaf of typewritten poems that scared and shook me — searing images of abuse, rage, heartbreak, and a ferocious longing for healing. It was the beginning of an important conversation for us both.

At the conclusion of Pixar’s Ratatouille — another great film about art — the art critic declares, “Not everyone can cook, but a great chef can come from anywhere.” It's true. And yet, great chefs may well toil in anonymity their whole lives if they go undiscovered. The world needs seekers like Uhde as much as it needs visionaries like Séraphine. And, like art-making itself, that search takes work. Uhde’s life was a discipline of study and writing about art — especially Picasso. The closer he looked, the better he could see.

Still, the goal is not to become high-scorers in some treasure hunt for art. We’re drawn to the outrageous beauty of Séraphine's paintings, but what about Séraphine herself? She put her arms around a tree, embracing the particulars of a luminous language that surrounds us. Art, if we look closely, can fine-tune the undisciplined instruments of our minds and hearts, thus helping us see life-changing revelation beyond the canvas.

Glimmers of revelation through art, art-making, and nature have made me an disciple of all three. I’m learning to be ready, every day, to find beauty in unexpected places. I want my soul to “stand ajar,” as Dickinson said, ready in every way “to welcome the ecstatic experience,” that I may live in a posture of awe, humility, and gratitude.

Séraphine is one of those experiences. Seek it out.

Overstreet Archives: Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Man's Chest (2006)

Who would have guessed that the person in the Pirates of the Caribbean credits who would eventually come to mean the most to me would be ... Mackenzie Crook?

But it's true. In recent years, I have watched the TV series Detectorists again and again, delighted and moved by Crook's extraordinary talents as a writer, director, and actor. He's given us one of the most human television series I've ever seen. Detectorists is poetic, quietly funny, and full of perfectly cast actors crafting unforgettable characters.

Before that, I only knew him as "the skinny guy with the big eyes" from Gore Verbinski's adventures at sea. And I quit paying attention to the Pirates movies after the third one which, overcrowded and overstocked with cargo, sank like a ship in a storm.

I was sad to see this franchise, which had a strong start and an even stronger second episode, go to pieces. I still think Dead Man's Chest is one of the most wildly entertaining adventure movies ever made, and an exhibition of brilliant fantasy world-building.

Early buzz about the second Pirates film worried me. I remember being as unexpectedly dismayed by the reviews for the film as I was unexpectedly delighted by the film itself. I snarled about that right here at Looking Closer, grateful to have support from the ever-reliable Steven D. Greydanus.

But then things took a turn for the better, with several critics appreciating Verbinski's bold vision. I noted that as well.

I chronicled the reviews from Christian media outlets at Christianity Today, including these:

Russ Breimeier (Christianity Today Movies) says Dead Man's Chest is "the same sort of fun thrill ride that used to be the norm during the summer movie season," and that the filmmakers "deserve praise for making an old-fashioned popcorn movie that knows how to entertain. Audiences may have been doubtful of the first movie, and perhaps a little skeptical of this one, but you can bet they'll be clamoring for Pirates of the Caribbean: At World's End come May 2007."

He adds a caution: "Like The Empire Strikes Back, this second chapter is considerably darker than its predecessor, though not as much as, say, Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom."

Steven D. Greydanus (Decent Films) raves that the movie offers "most of what you'd expect: an even more convoluted plot, even more eye-popping special effects and makeup, and an even more powerful supernatural nautical antagonist. … [T]he filmmakers have let their imaginations run wild, taking chances, striving to outdo themselves on every level. It's an approach that can yield self-indulgent, bloated excess—or brilliance." He concludes that this is an example of the latter, calling it "one of the most memorably entertaining popcorn flicks in memory."

David DiCerto (Catholic News Service) says, "For a sequel, the new movie matches—if not tops—the original as first-rate popcorn entertainment with all the right ingredients: action-adventure, spectacle, screwball comedy and a bit of romance."

Taking a different tone, Marcus Yoars (Plugged In) opens fire on Captain Jack's ship. "I never thought the words swashbuckling and tedious could ever describe the same thing, yet that's the rare combination found in [Dead Man's Chest]."

And Christian Hamaker (Crosswalk) says the movie "goes on much too long, then makes no effort to provide a satisfying ending." He adds that it "includes heavy doses of the macabre that will leave some viewers more disgusted than amused." But he concludes that the film "has a cartoonish quality that leavens even its darkest moments, and it includes a couple of bang-up sequences that remind us of how summer-movie thrills can delight with their lunacy and inspiration."

And then, a week later...

Josh Hurst (Reveal) calls it "the most exhilarating and memorable big-screen adventure this side of The Fellowship of the Ring. There are elaborate set pieces; action sequences you won't believe; mystery upon mystery and secret upon secret; special effects and pyrotechnics that raise the bar for action movies everywhere; a thrilling sCcore that ranks among the most distinctive since Raiders of the Lost Ark; and more spirited adventure than a whole galleon of amusement park rides. It's also riotously funny."

At Looking Closer, I posted this lengthy blast of enthusiasm...

In a year when summer blockbusters have proven disappointing at best, disposable and joyless at worst, Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Man's Chest arrives like an emergency delivery of fun. And apparently it's more fun than some people can absorb in one sitting, judging from early negative reviews. Bursting at the seams with adventure, chase-scenes, comedy, and monsters so fantastic that Peter Jackson's gonna turn green with envy, it's making this moviegoer shout a hearty yo-ho-hallelujah.

Director Gore Verbinski and his cast know what they're here to do, and what they're not here to do. They're not here for some kind of ponderous action movie with timely and relevant social commentary. They're not here to indulge in any kind of angst. Leave that to someone else. Somebody somewhere needs to step up and deliver the kind of high-spirited fun that justifies the existence of popcorn, that reminds us that the alphabet of summertime moviegoing does not begin with "A for Angst," but rather "A for Adventure." These seafaring madmen are here to throw back big mugs of rum, put on elaborate costumes, slather on layers of makeup, and party until they drop. They're ready to unleash action sequences so masterfully choreographed that Rube Goldberg would stand up and cheer.

And having suffered through the frenzied flop of X-Men: The Last Stand and the burdensome solemnity and lifeless dialogue of Superman Returns, I say, "Count me in!"

Warning: If you want to enjoy this film to the fullest, avoid other reviews that will contain spoilers, and don't read the cast listing. You'll thank me when those delightful surprises arrive in the way they were intended.

* * *

Gore Verbinski's Pirates of the Caribbean: The Curse of the Black Pearl was surprising because it turned what was basically a big screen marketing tool for an antique Disney amusement park ride into a memorable adventure film, and gave Johnny Depp his defining role.

The sequel, Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Man's Chest is even more surprising. It gives us much, much more of everything that worked in the first film, and somehow stuffs in all kinds of new surprises, making it one of the most hilarious, imaginative, and relentlessly clever adventure films of all time.

Some will complain that it runs too long, and they're right. It runs long like some of the best parties.

Some will complain that there's more running back and forth than in the whole career of Benny Hill, and they're not far off the mark. It's like watching three games of "Capture the Flag" happening at the same time in the same park.

Some will cry out that this sequel commits the sins of Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom, giving moviegoers something much darker and more violent than they expected... and parents should indeed be warned. This is an extremely violent, phantasmagorical adventure movie in which crows pull eyeballs from eye sockets and pirates are blown to pieces, devoured, and lashed into ribbons. But it's the kind of grisly comedy that revels in the absurd — it's not gore for gore's sake.

Some will find the plot unfocused — and the first people to tell you that might be the screenwriters themselves, Ted Elliott and Terry Rossio. They were clearly having so much fun piling on the zany twists that I suspect they consumed a bottle or two of rum all for themselves.

But what does all of this matter when the movie, which is based on a ride that basically goes around and around, boasts more enthusiasm, humor, and creativity than the rest of this year's action films put together? The plot here is an excuse for action, not a reason to be.

Who's really going to complain about a summer movie that delivers too many good things, including the most spectacular big screen villain — in presence, design, and personality — since the shadow of Darth Vader first loomed in the smoky corridor of the rebel blockade runner?

And who can contend with Johnny Depp, who storms the screen with more confidence and charm than we ever knew was possible? Returning to the role of the irascible, irresponsible, irrepressible Captain Jack Sparrow, Depp gives one of those rare comic performances that would win an Oscar if the Academy was ever bold enough to recognize comic genius. Depp says he based his performance on Keith Richards of The Rolling Stones (who will, we're told, appear in the third film as Sparrow's father). But Sparrow shows us more than that. Here, this demented, dreadlocked sailor gives us hints of Tom Waits, Bugs Bunny, Errol Flynn, Buster Keaton, and Charlie Chaplin. For all of Depp's great performances — from the rock-and-roll rebel of Cry Baby to the pensive Gilbert Grape to Edward Scissorhands to Ed Wood — Captain Jack is the triumph of his career. He made an unforgettable entrance on top of a sinking ship in the first film. He makes another unforgettable entrance here. And the fun begins.

It would be insufficient to say that Verbinski's actors perform with relish. They throw in ketchup and mustard too, and all of the fixings.

The whole gang is back:

Refusing to let Depp have all the fun, Orlando Bloom shows he's still determined to become an engaging action hero, even though Will Turner is more a force of chivalry and virtue rather than a character. (And to balance out the reckless irresponsibility of Sparrow, we really do need a heavy dose of true heroism.)

Keira Knightley returns, radiant as ever, in the role of Elizabeth Swann, Turner's true love, and she shows more vim and vigor than any adventure heroine since Karen Allen in Raiders of the Lost Ark. One of this film's big surprises is just how complicated Elizabeth really is, and just how vulnerable to change. Just when the movie begins to wear out its welcome, heading past two hours, it's Elizabeth who suddenly takes center stage, one foot firmly planted in moral compromise.

Jonathan Pryce is back as her father, Governor Weatherby Swann. Jack Davenport is back as the disgraced Commodore James Norrington, who managed to redeem himself in the final moments of the first film, but who turns back to bitter villainy here. Kevin McNally reprises his role as Jack Sparrow's right hand man, a tipsy sailor whose job it is to provide lengthy exposition, lest we forget that there's a story going on. And the crusty old clowns Ragetti and Pintel, played by Mackenzie Crook and Lee Arenberg, are back stirring up trouble like the roguish scallywags they are.

* * *

The plot is basically a boilerplate adventure-film outline. Actually, it's more like several outlines.

When we last left Will Turner and Elizabeth Swann, they had set Captain Jack Sparrow free from his death sentence, and seemed well on their way to a glorious wedding. This film opens with a bewildering sequence in which we learn that Lord Cutler Beckett (Tom Hollander) of the East India Trading Company is going to punish Turner and Swann until they agree to find Captain Jack and capture something he keeps in his pocket... a magical compass.

The compass is a mystery. We don't learn until much later what it can do. But for our purposes, the compass is the closest things to a moral center for this frenzied film. It gets us thinking about each character's moral compass. What — or who — are they willing to risk their lives for? What do they treasure in this life?

Treasure — the bread and butter of any pirate movie. And there's a lot of treasure being sought here. Beckett wants the compass. Jack Sparrow wants something else... he wants a mysterious key. And soon, he's on the hunt for the heart of Davey Jones, that legendary sailor who lurks above and beneath the waves cursing unfortunate souls to slave away on his boat of nightmares. For Jack, the lost heart means freedom from the curse upon his soul... motivation enough. But for others, the heart of Davey Jones is the secret to ruling the seas. We're not sure how that works, but I have a hunch we'll learn.

And it doesn't really matter yet, because the search keeps us busy contending with all manner of spectacular monsters and life-threatening ordeals, including a tribe of primitive savages who set up their captives as gods before eating them; a massive sea "beastie" called "the Kraken" (but how do you pronounce that?); and, of course, Davey Jones himself.

Dead Man's Chest is clearly a deliberate attempt to play The Empire Strikes Back to the Star Wars of the first film. It's an amalgam of great second-movie plot twists, borrowing liberally from Star Trek 2: The Wrath of Khan to Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom. There's a father-son relationship at the heart of the film. There's a rebellious jerk who just might turn into a responsible hero. There are grudges and chases and fiery clashes between battleships. There's a character whose heart has been yanked beating from a chest for all to see. There's a spooky Caribbean witch (Naomie Harris), like Yoda's wicked and meddling auntie, keeping secrets in the jungle. There's even a rope bridge crossing a chasm that looks like it could break at any moment. It is, in short, a return to all that was great about the adventure films of the early 1980s.

Playing the film's equivalent of the feisty Princess Leia, Knightley, having escaped Tom Hollander's clutches in Pride and Prejudice, must dodge him once again here. As Will Turner, Bloom is the earnest Luke Skywalker of the story, a young man who must reckon with a troubled legacy left to him by his father, Bootstrap Bill. And, like Skywalker in that second Star Wars film, Turner is separated from his friends, struggling with the evil emperor of the seas, and gambling to rescue one of Davey Jones's significant captives (Stellan Skarsgaard).

Meanwhile, we watch as the curse on Sparrow continues to gain ground, stalking him in the form of the Kraken (which is basically the granddaddy of the Watcher in the Water in The Fellowship of the Ring). He's not concerned about heroism, he's concerned about escaping with his life. But like Elizabeth, we have a hunch that somewhere in his rum-soaked heart, there's a glimmer of goodness. When she prods at him, hoping to ignite his sense of virtue, she reminds him that there are moments for men to rise and demonstrate selfless courage. He replies, "I love those moments. I like to wave at them as they pass by."

But the real surprise of the movie is Davey Jones himself. With a head made of octopi, a buccaneer's hat so commanding it will make other sailors blush, and a fearsome ship called the Flying Dutchman that looks like it could open up its jaws and swallow other ships whole, Jones storms about the deck of his ship, surrounded by some of the most imaginative and dazzling monsters ever designed. He has something that the villains of Superman Returns and X-Men: The Last Stand never mustered — a tangibly sinister presence. He's really scary, and not just because he's ugly, but because he's evil... really evil. As evil as Darth Vader, Captain Hook, Dracula, and Saruman combined. He revels in any opportunity to ruin something good, spoil a pending marriage, sink a beautiful boat, ensnare and possess a soul. As the tentacles writhe across the collar of his dark coat, so moviegoers will be writhing in their seats.

I'll be blunt: Davey Jones is the most convincing and arresting computer-generated character ever made, and that includes Andy Serkis's King Kong and Gollum. Just watch the expressions on that face, and look at the way he moves. He's as real as anything in this movie. And the great British actor Bill Nighy gives him real venom. He's a marvel, and I hope we see him again. I suspect we will.

Hans Zimmer's soundtrack brings all of the bombast necessary, stirring up the anthemic glory of the great John Williams themes. And, in fact, while the film is all about a quest for the heart of Davey Jones, the movie ends up making me think about another person of the same name... Indiana Jones. I don't think I've had this much high-spirited fun at the movies since Indiana and his hat set out for adventure. And Johnny Depp has made it perfectly clear that he's as good a match for the role of Jack Sparrow as Ford was for Jones. He's made these first two Pirates films unexpected classics, worth watching again and again.

And, if Verbinski can keep a firm grip on the wheel of this ship, maybe he can be the first to outrun the Curse of the Adventure Movie Trilogy: Pirates might just be the first adventure movie franchise to deliver three satisfying episodes in a row.

Overstreet Archives: Pirates of the Caribbean: The Curse of the Black Pearl (2003)

In 2003, I approached Pirates of the Caribbean: The Curse of the Black Pearl with trepidation. The movie caught me by surprise. Below, I'll restore my original Looking Closer review to this site — it's been missing for many years.

At the time, I was writing my weekly Film Forum column for Christianity Today. I noted these early reviews:

Some film critics in the religious press are offering early raves. Michael Elliott (Movie Parables) calls it "the kind of rousing, swashbuckling adventure that hasn't been seen since Errol Flynn last swung a cutlass."

Bob Smithouser (Focus on the Family) agrees that it "could've been a lazy attempt to capitalize on a brand name, but it actually delivers the thrills, laughs and romance audiences demand from a summer popcorn flick." He adds a caution about the film's heavy doses of "creepy violence."

The critic at Movieguide writes, "Despite some pagan, occult elements, Pirates…is a swashbuckling jolly good time at the movies, with some positive moral and redemptive themes." However, he seems to contradict himself by concluding, "The pagan, occult aspect… spoils its moral, redemptive elements." He adds that the film's fairy-tale-variety "curse" will be controversial for "Bible-believing Christians and Jews." (Non-Bible-believing Christians will apparently not be bothered.)

You can revisit that edition of Film Forum here.

And then I published this at Looking Closer...

Growing up, I had an aversion to amusement park rides. They looked noisy, expensive, and I had a feeling they’d make me sick to my stomach. After college I was reluctantly talked into a rollercoaster ride by a girlfriend. Lo and behold, I loved it. And the girl and I lived happily ever after.

Similarly, I have been dreading this idea of films “based on” amusement park rides. Disney has been hunting for ways to keep their vision fresh and engaging, and this idea smacks of desperation. But when I saw the cast lined up for Pirates of the Caribbean — Johnny Depp, Geoffrey Rush, Jonathan Pryce, and Orlando “Legolas” Bloom — I consented to sit through a screening. I was not optimistic. There hasn’t been a decent pirate movie made in my lifetime.

But five minutes into the film, my apprehension had walked the plank. (Yes, I'm going to say it now...) Shiver me timbers — Pirates of the Caribbean: The Curse of the Black Pearl is fun! It’s also funny. It delivers everything I’ve wanted to see in a big-budget pirate movie since I was a kid. It avoids the pitfalls into which Spielberg's disastrous Hook plunged. Echoing the ambition, mischief, boyish glee, and whimsical wit of 80s adventure films like Raiders of the Lost Ark, Gremlins, The Goonies, and The Princess Bride, Gore Verbinski has concocted a film that manages to include all of the predictable pirate clichés and yet remains unpredictable and fresh. Following the Wachowski Brothers, Ang Lee, and other heavy hitters, Verbinski (who directed The Ring and The Mexican) steps up to the plate as the summer’s underdog and outplays them all, hitting a solid triple.

The triple — if I may continue my bad sports metaphor — consists of 1) yet another knockout performance by Johnny Depp (his funniest yet, in fact); 2) some impressive ILM special effects (truly astonishing in the film’s frenzied finale); and 3) one of the funniest and most unpredictable adventure-movie scripts to come along in a good while, credited to Ted Elliott and Terry Rossio (Aladdin, Antz, and Shrek).

The best thing in the film is also a threat to its success. As Depp sails through, his performance as the lone pirate Captain Jack Sparrow is so inspired, so zany, and his costume so outrageous, that he nearly overturns the other actors in his wake. He keeps us slightly off-balance in every scene, because he himself is off-balance, staggering punch-drunk and stammering in slurred speech. The cosmetics crew used all 64 crayons on his face. The beaded dreadlocks framing his features are a giveaway that Sparrow’s more interested in the style of piracy than its substance. If there’s a sequel, he’ll probably be sporting more golden teeth due to the number of times women slap him for his infidelities. Depp clearly enjoys his makeup, and so does Verbinski, who never lets his puckish supporting character stray too far from the focus. Verbinski is one of the few directors who taken advantage of Depp’s splendid talents — the others would be Terry Gilliam and Tim Burton — and he gets a performance out of him that would earn an Oscar nomination if there were any justice.

Sparrow is a vigilante pirate with claims of famous escapes and derring-do. (The key word there is “claims.”) After the film’s spooky opening sequence has passed, Sparrow sails into port in the grandest entrance of any big screen character I can remember. We quickly learn that Sparrow’s not welcome in this harbor, and neither are any other pirates. Jonathan Pryce plays the local governor whose daughter Elizabeth is frowning at her suitors. Elizabeth is played by Keira Knightley, whose radiance reminds me of Uma Thurman. Even a tightly strapped bodice can’t hold back her, um, strong personality. She makes this independent young heroine more than just the cookie-cutter feminist that has become the politically-correct anachronism of films set in the distant past.

Elizabeth is being pursued by a stuck-up soldier (Jack Davenport), but her affections lie with a young blacksmith — Will Turner (Orlando Bloom) — whose secret she has quietly kept since she was a child. Turner was pulled from the wreckage of sinking ships after a pirate raid many years ago. Turner’s past and parentage are a mystery, but his future seems secure due to his skill as a swordsman and sword-maker. Like the governor, he hates pirates, and so he puts up a spectacular defense when the township is attacked by the legendary pirates of a ship called the Black Pearl. But the battle reveals that he may have more in common with his enemies than he’d like to admit. Before he can make sense of it, the laws of alliteration have placed the damsel in distress, and Will pulls on the boots of responsibility and sets out to rescue her.

He teams up with Sparrow, of course, who is in this for reasons of his own. The Black Pearl was once his ship, but his crew mutinied under the direction of a dastardly villain called Barbossa (Geoffrey Rush.) Barbossa, who leers and snarls in a pirate dialect that should have earned him subtitles, makes it very clear why he has captured Elizabeth. She has in her possession the last piece of treasure that the pirates once recklessly spent. In spending it, they brought upon themselves a terrible curse that consigns them to lives as living dead – ugly pirates by day, decomposing zombies in the moonlight. Thus they want their money back, so to speak. If they can recover the gold, they'll be healed and whole once again. So... to sum up... the pirates want the gold, Elizabeth has the gold, Elizabeth wants Will, Will wants Elizabeth, and Sparrow wants his old ship back. Thus the games begin.

Reciting the pirate’s code, a snarling seaman growls, “Any man who falls behind stays behind.” That’s true for the audience too. Pay attention to the specifics of the curse, and you’ll be impressed with just how cleverly Verbinski employs them in the finale. He uses this opportunity to pay tribute to Raiders, giving us a mischievous monkey, poisoned fruit, a medallion on a chain that everybody wants, a drinking contest, villains of the decomposing variety, and two scenes that resemble the opening of the Ark of the Covenant. But there are plenty of inventive twists as well. The best involves an unexpected stay on a remote and deserted island with two of the film’s leading characters. And Hans Zimmer’s score is one of his very best, a boisterous and dramatic accompaniment that John Williams could not have surpassed.

For all of its wit and whimsy, Pirates deserves a few cautions for the younger viewers. Pirates do not make good role models, so parents will probably want to make sure small children do not come away overly enamored of Sparrow the pickpocket, Sparrow the womanizer, Sparrow the vigilante. It’s the same dilemma facing Elizabeth’s father. When she fingers a piece of pirate treasure and murmurs, “I find it all fascinating!”, her father appropriately replies, “That’s what concerns me.” Fortunately, the film does not conclude with Elizabeth “going pirate”; she remains a virtuous, honest, and admirable hero who is more willing to see past a person’s status and mascara to the heart within.

In the end, greed is clearly drawn as wicked and self-destructive. True love gets a few moments in the sun. And when you come right down to it, Sparrow’s virtues overpower his imperfections. It’s what sets him apart from his nasty decomposing colleagues. When the legalistic authorities decide to execute Sparrow for his trivial wrongs in spite of his life-saving heroics, a self-righteous soldier declares, “One good deed is not enough to cure a man.” Sparrow snaps back, “But it is enough to condemn him?”

If viewers come away from the movie with any complaint, it will probably be that Depp’s efforts make him the more engaging romantic hero, and that Elizabeth's turn toward Turner is disappointing. The film’s most glaring weakness is that its hero, played by the capable and charismatic Bloom, is reduced to being a forgettable supporting character, eclipsed by his brilliant comic relief. Too bad Verbinski couldn’t find a way to show off more of Bloom’s capacity for action and stunts. Even when the cameras weren’t rolling on Fellowship of the Ring, Bloom was playing an action hero, jumping out of airplanes and bungee jumping across New Zealand. In Pirates of the Caribbean, he crosses swords a few times and spends the rest of the movie on the sidelines gazing with longing at Keira Knightley… or is it with envy at Johnny Depp?

At long last — a substantial documentary on Flannery O'Connor

Listen to a podcast reading of this review and additional commentary from Jeffrey Overstreet at the new Looking Closer podcast.

How I wish this film had been available last winter when my Seattle Pacific University students and I were politely arguing about Flannery O'Connor.

From January to March, I taught a course at Seattle Pacific University on literature and faith, and an introduction to O'Connor's short stories — we read "A Good Man is Hard to Find" and "Revelation" — was one of the main events. I showed a few videos of interviews with scholars who praise her. I showed an archival video of the National Book Award winner as a child: In 1932, she made the news because she had a pet chicken who could walk backwards. That set us up to talk about her eventual enthusiasm for pet peacocks. But what I really wanted was a vivid, compelling documentary, or a well-researched biopic as striking as the depiction of Emily Dickinson in Terence Davies' A Quiet Passion. (In view of how often I hear O'Connor's influence in the Coen brothers' films, I'd love to see them take on a Flannery film.) To date, the only feature-length project worth talking about has been John Huston's Wise Blood, but that's the kind of film that could scare people off from O'Connor forever if they're not prepared for it. O'Connor is such an intriguing, controversial, and compelling character on the stage of American literature, she deserves a variety of portraits.

Alas, I couldn't find anything sufficient to make an engaging multi-media case for my class of O'Connor's relevance.

My timing for teaching O'Connor's work was either perfect or terrible, depending on your point of view: Pop culture has been stormy lately with the rise of "Cancel Culture." If you've been self-isolating from the zeitgeist: Cancel culture is a term referring to sneaker waves of popular opinion that rise up — primarily on social media — with demands to silence and erase important cultural figures, banishing them from respectful consideration altogether due to a sudden spotlight on something they've done or said that is judged as inappropriate or offensive. For example: J.K. Rowling? CANCELED — in spite of the fact that generations are in love with her literary legacy, and countless kids learned to love reading because of her Harry Potter books. Why? Because she revealed an unpopular perspective on gender.

I'm with Nick Cave on Cancel Culture: It represents the worst in human nature — a self-righteous negation of someone's complex humanity over one point of disagreement without any attention to nuance, dialogue, relationship, or appreciation of difference. It's a way of saying "You must check all the boxes on what I consider right and proper or I'm actively seeking to delete you from the world." Evangelical Christian culture is very, very good at this kind of rash judgement, and has been for a long time, and it has only served to amplify their reputation as a spiteful people possessed by a spirit of condemnation — that is to say, an Anti-Christ attitude.

I worried that Cancel Culture might happen to Flannery O'Connor, and a debate over her work that has been simmering for decades suddenly flared up into a blaze in 2020 with a New Yorker article by Paul Elie and several substantial responses like this one. But my class was ahead of the trend: No sooner had these students ventured into O'Connor's stories than someone opined that we should cancel O'Connor. The stories were too offensive. The White Establishment was just making excuses for the inexcusable. Attention to her stories would only pour salt into open wounds.

And now, a little too late to help my class, here comes Flannery — a documentary directed by Elizabeth Coffman and Mark Bosco. This spirited, informative, elegant overview of the Roman Catholic writer's fascinating life story makes a strong case for her genius and her ongoing relevance. While it reveals very little that will surprise O'Connor scholars, it narrates her complex history, style, and personality with efficiency and creativity, pausing at all of the obligatory landmarks while also taking us off-road to visit lesser-known spots, visit with friends and family and colleagues and critics, and zoom in on what makes her storytelling so distinctive.

The film's greatest gift is its gallery of insight from experts as diverse as Sally Fitzgerald (O'Connor's friend); her publishing partner Robert Giroux; Ashley Brown, founding editor of Shenandoah; Marshall Bruce Gentry of Georgia College and State University; actor Tommy Lee Jones; comedian Conan O'Brien; memoirist Mary Karr; the great journalist and memoirist Richard Rodriguez; and such prominent African American writers as The New Yorker's Hilton Als and O'Connor's literal neighbor — Alice Walker.

In fact, Walker herself makes a concise but impassioned defense of O'Connor's work: "If you just see the Southern writers, generally — the white southern writers — on the basis of more or less their racism, which is there... nobody should be locked into ideologies that they were born into and they often were were not able to see. So the writers get sold down the river, too."

Another feature of Flannery is the way the filmmakers infuse imagination and energy into Ye Olde Talking Heads Documentary Format with colorful illustrations that take hints from O'Connor's own cartooning, animating scenes from both her stories and her life.

Still, at 97 minutes, the film feels like more than two hours, and I suspect that playing the full film to a class of undergraduates might weary their attention due to its conventionality and its preponderance of testimony. For insights on (and from) O'Connor, it's a four-star affair; for documentary artistry, it's more of a three-star deal. While I wish I had been able to share this with my class, I am still waiting for the Great Flannery Film — something that will do for O'Connor what I'm Not There does for Bob Dylan.

Nevertheless, I'm recommending the film to everyone — curious beginners, O'Connor's admiring fans, and especially teachers as a worthwhile contribution to any conversation.

Full disclosure: Despite her flaws — a surprising fact of human nature: we all have them — few artists have inspired and influenced my life, my faith, and my creative work like Flannery O'Connor. Two of my lifelong passions are also hers: Exposing the prevalence of insidious hatreds and hypocrisies in Christian culture, and at the same time proclaiming the world-saving truth of Christ's Gospel, a message of God's love and grace that can and should set us free from all hatred and hypocrisy. So I am eager to draw readers into the thick of her Southern Gothic stories.

I know full well the trouble I'm courting in doing so: I'm wide awake to O'Connor's struggle with the fierce racism of the culture into which she was born, in which she grew up, and which she came to resist in the American South. And I am equally aware that she did not live a life unstained by that sin. I'm not sure it would have been possible to be white in the American South and completely avoid the racism woven into the language, lessons, laws, and traditions of that world. (In the same vein, I have been influenced by the cultural hatreds of the conservative evangelical culture in which I grew up, and have been guilty of hypocrisies common in that context. Should I be canceled?)

To study O'Connor's stories is to read about all kinds of racial prejudice, and to witness acts of physical, verbal, psychological, and spiritual violence. Having made this clear at the beginning of the course, I refused to drop O'Connor from the syllabus until we had brought some intellectual rigor to the matter at hand. I posed this question to my students: Isn't there a difference between an artist condoning evil and an artist exposing it? We pressed on — with clear disagreement in the room.

The class struggled uncomfortably with both stories (and I doubt any good reader is ever comfortable with O'Connor). And I found it difficult to give sufficient class time to exploring the poetry within those stories and the artistry in her character development because we were so frequently wrestling with whether her stories, laced with occurrences of 'the n-word' and other slurs, deserved our attention or not.

If we reserve our attention for only those artists we deem as Morally Blameless, we expose our own ignorance that there is no such thing. And we discredit those artists who are waking up to the very environmental toxins that that corrupt them, and who are beginning to kindle some kind of heat and light that will eventually help expose and purge those toxins. Artmaking is a process, after all — artists make art as a process of discovery, and often grow and change in response to those discoveries. With O'Connor as with any artist, the art is an enigma alive with the artist's DNA and that of the world around her, including her artistic influences, her landscapes, and, I would argue, some evidence of the God who made her. I appreciate how O'Connor's stories give us images of a shockingly broken world and an even more shockingly powerful grace. Her understanding and embodiment of Christian faith is so much more authentic and so much more courageous than almost other all other writers I've ever read. And her devotion to Jesus is clearly the source of her enlightenment on matters of race, an enlightenment that was liberating her from most — if not all — of racism's influence.

To put it bluntly, I can't imagine an adequate course in Christianity and literature that doesn't wrestle with O'Connor.

But don't prioritize my white-American-male take. Better to listen to the testimony most unfortunately missing from this film: the voice of Toni Morrison. In her book The Origin of Others, Morrison argues that discrimination is a social construct: "How does one become a racist, a sexist? Since no one is born a racist and there is no fetal predisposition to sexism, one learns Othering not by lecture or instruction but by example." She then goes on to spotlight "The Artificial Nigger," O'Connor's 1955 short story in which a man tries to indoctrinate his nephew in an attitude of racism. While some of my students will immediately disregard the story for its title, the title itself points to the fundamental misconception that ends up damning the story's main character — an evangelist of hate.

Shouldn't the praise of a literary giant like Toni Morrison give us pause before canceling the artist in question? If she who is arguably American literature's most accomplished African American novelist finds O'Connor's fiction to be essential literature on the matter of race, surely that is enough to keep O'Connor's work on the table for serious critical scrutiny, if not to ensure its canonical permanence.

NM: You know, when I was growing up I thought you had to be at least 50 to write novels. I thought it wasn’t allowed, like it was against the law or something.

TM: I’ve read some fantastic ones who have written a lot but dropped dead at 50.

NM: Who do you admire now?

TM: There’s a woman I love, she’s really hostile, Flannery O’Connor, she’s really really good.

Anyway — I'm not posting Morrison quotes as "proof" that O'Connor must be forever established as top-tier English literature. I'm not qualified to make such a claim. And I'd love to attend a conference full of critical perspectives on O'Connor by African American scholars — that would be most enlightening.

But I am making the argument, supported by the new film, that O'Connor's work isn't beloved or admired just because white men say so — as one of my students seemed to believe. I'm with the global, multi-cultural community of readers who believe there is astonishing artistry in these stories that should continue to influence readers around the world for generations, and that they can serve as powerful medicine exposing — and even treating — a uniquely American strain of a disease that has run rampant through human history. And I am grateful for how they incline us toward repentance for our own sins and the sins of our ancestors, with inklings of some all-reconciling glory at work in the world.

What's more — I believe the stories are enhanced by O'Connor's own self-awareness of prejudice in her own heart. As a storyteller myself, I can only hope to aspire to that kind of humility, that kind of willingness to challenge and even illustrate my own failings. For the glory of God.

As O'Connor's faithful and admiring student, I am grateful for the gift that this film will be in helping us appreciate both the strengths and weaknesses of a great artist, so we can carry the testimony of her life forward with wisdom, rather than reacting and canceling her for being as human as the rest of us.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WwBBlgZ8LRc

Overstreet Archives: Margot at the Wedding (2007)

Once in a while, I stumble onto a review that was published in another journal that I never included in my Looking Closer archive. So here, for the first time on this site, is my original holiday-season review of a film from writer and director Noah Baumbah called Margot at the Wedding.

I'm a huge fan of films that Baumbach has collaborated on with Wes Anderson. And the films he has directed in collaboration with Greta Gerwig — Frances Ha and Mistress America — are both outstanding. In those partnerships, Baumbach is able to contemplate human weakness in a way that is troubling and enlightening. But when he's writing and directing on his own, his films, while powerfully acted, tend to sink into an off-putting cynicism.

Of all of his films, this is the one that troubled me most — and not in a meaningful way.

Here's the review from November 2007, originally published at Christianity Today.

It’s the holiday season, and what could be more discouraging than the annual parade of shallow, sugar-coated, sentimental trash that America calls “family entertainment”?

This year, there just might be something worse. Margot at the Wedding is an independent movie, powerfully acted, sharply written, and extraordinary in its character development and detail. But despite all of these strengths, it will leave audiences feeling like they just paid ten bucks to swallow a cup of cold gravel.

It’s possible that Margot at the Wedding could be an example of reverse-psychology when it comes to the traditional family movie. By immersing us in one of the cruelest, most hateful families ever to grace the silver screen — and then by holding us under those murky waters for ninety-two minutes — writer/director Noah Baumbach will make almost anyone grateful for the family they have, no matter how damaged it might be.

And it’s a shame, really, because Baumbach is an immensely talented storyteller. His 1995 debut Kicking and Screaming (not to be confused with the Will Ferrell soccer-dad comedy) was an insightful, hilarious, and moving little movie about post-collegiate crisis and the hard work of moving on into a meaningful adult life. Two years ago, he returned with The Squid and the Whale, an observant and heartbreaking comedy about two boys caught in the crossfire between impossibly selfish and cruel parents.

Where The Squid and the Whale felt like a lament, an exposé of the damage that divorce can do to children, Margot at the Wedding feels almost like an act of revenge. It feels like the artist has opened up a journal where he chronicled all of the evils and ugly misdeeds committed by family members and friends. It may be true-to-life, but the effect of all of this harsh realism is a miserable moviegoing experience.

The title character, played with extraordinary complexity by Nicole Kidman, is a successful novelist who is absolutely insufferable in real life. Her books are ways in which she can vent her own misery, but it doesn’t seem to be doing her any good.

When the film begins, Margot and her son Claude (Zane Pais) are off to “show support” for Margot’s sister Pauline (Jennifer Jason Leigh), who is preparing to marry her fiancé, a loveable oaf named Malcolm (Jack Black).

But Margot’s idea of “support” is the movie’s idea of a joke. She cannot contain her contempt for Malcolm, nor can she conceal her desire to tear this relationship down. “He’s like guys we rejected when we were sixteen,” she sneers, doing her best to sabotage the pending nuptials.

And yet, Pauline and Malcolm make a fine match compared to Margot and her lover, Dick (Ciairin Hinds). She tells everyone that they’re collaborating, but Dick’s an arrogant and cruel man, quick to judge and punish others, and doesn’t hesitate to launch a humiliating attack against a friend in front of a live audience.

Pauline and Malcolm are living in the Hamptons estate where the sisters grew up, and chairs for the wedding guests are being arranged in the yard, beneath a grand old tree that a younger Margot used to climb. If you suspect that the tree is a symbol, you’re right. And you’re likely to guess what will happen to that tree before this storm is over.

As if this family doesn’t have enough trouble among themselves, Margot turns a skirmish between Pauline and her creepy neighbors into a full-scale war. She’s quick to intervene if she sees a child being mistreated — a clue, perhaps, about the source of her psychological disorders.

But Baumbach doesn’t seem interested in investigating where such fractures come from. He just moves from one nasty exchange to the next. There is no variation in tone: It’s just characters spewing bile at all available targets and only occasionally collapsing into one another for something like comfort. The neighbors are carving up animals, but Margot and company are slaughtering each other.

And when Margot retreats into the house, frightened by the consequences of her own meddling, she starts popping pills that don’t belong to her and snooping through her sister’s underwear drawers, trying to expose more ammunition to use in her “shock and awe” campaigns against everybody in sight. Then she sits around hating herself — before starting all over again with the same tactics.

When Margot’s husband Jim (John Turturro) comes calling, it looks for a moment like a savior has come to the scene. He seems to have some resilience through Margot’s attacks, and when he comforts her he seems like some kind of guardian angel. But his faint light is squelched by the chaos that’s beyond his control.

And poor Claude, while sympathetic, is just a variation on the pubescent victims in The Squid and the Whale. (What’s with Baumbach’s preoccupation with alienated teenage boys who leave pieces of themselves behind? In Squid, one boy smeared bodily fluids on the school lockers, and Margot’s Claude leaves pieces of his skin in other peoples’ rooms.)

Only Malcolm seems to have any sense of the depravity on display, and we find some comfort in his presence until Baumbach — as ruthless in his search for ugly secrets as Margot herself — targets him and leaves him weeping over his own failures. There’s more hope for humanity at the end of the Coen Brothers’ No Country for Old Men than there is here.

https://youtu.be/zhTk_SIhFEQ

Sure, we can muster compassion for these characters. After all, Baumbach draws them with intricate detail, so we can see potential in almost all of them, and pity them for the damage they probably suffered in childhood.

We can also marvel at Baumbach’s talent. His aesthetic is clearly influenced by the French New Wave films, especially the movies of Eric Rohmer. His sharp ear for dialogue — for the words people say, and the daggers they conceal within them — is a powerful gift. And his apprehension of the damage people do to each other, and how they do it, has served him well in the past, and may lead him to a masterpiece someday. Here, he’s drawn out some of the finest acting we’ve ever seen from Kidman, Leigh, and Black. This extraordinary cast makes these characters convincingly caustic and complicated.

But alas, the accumulation of scenes in which characters degrade each other is ultimately exhausting. Why do we need to see Pauline have a rather messy accident in the middle of a walk in the woods? Is this some sort of helpful metaphor? Do we need any more reminders that these people are full of… well… do I really have to say it?

Many other directors have brought us into family clashes like this. Paul Thomas Anderson, Wes Anderson, and Woody Allen come to mind. But each of them have enough insight to glimpse the possibility of redemption. Or they find enough humor to relieve the tension and prevent us from wallowing in misery. Baumbach’s focus on mean-spirited behavior is stifling.

At one point, Malcolm erupts in fury at the cruel and inhumane treatment that the people around him are demonstrating. When Pauline asks him to calm down, he declares. “This is the right reaction! Compared to everything else that’s going on, this is right!”