Overstreet's 39 Favorite Films of 2020

[UPDATE: I've revised this post. Now, it's a Top 40 countdown. (I've added a couple of films that I caught late in 2021.)

The last films I saw on the big screen before the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown sealed off movie theaters like Egyptian tombs, like temples of a lost world...

... was The Invisible Man, a movie about living in fear of an unseen threat (like... a virus?).

That was March 9.

Since then, I've been watching feature films in my home office, linking my laptop to a 32-inch computer monitor and channeling the sound to some heavy antique stereo speakers that I've had since the late '80s. That experience has often reminded me of the early '90s, when I didn't have much money for movie tickets, and so, since I worked at a video store, I'd bring stacks of VHS tapes home for a do-it-yourself film school.

I won't pretend that everything about this strange new world of moviegoing has been fine. Streaming stuff in spaces filled with distractions just isn't an acceptable replacement for the real thing. It doesn't feel fair to the artists who composed their images for a grand canvas. And I don't have that electrical charge of experiencing new things with a large crowd in the dark. In the light of home, I am so easily distracted by what's happening — or, more likely, what needs to happen — around me, because almost anything that happens here is, to some extent, my responsibility and I can't block it out. It's too easy to find reasons to press "Pause," interrupt the flow of a film that is meant to play uninterrupted, and then return to it after an hour (or a week) having lost my suspension of disbelief.

So, if a film captured my imagination and made an impression in 2020, it did so by overcoming more challenges than might ever test a theatrical presentation.

What's more, it impressed me on a small rectangle in a well-lit room. It was like hearing a symphony playing on a cell phone in a train station instead of experiencing it live in a concert hall.

Whatever the case — many films still made powerful impressions on me.

And I'm eager to recommend them to you.

Here's are the annual fine-print disclaimers:

This list, like all of my film lists, is a work in progress.

Of course it is. The temptation to pronounce judgments on works of art is great — more than ever in this culture of “rating” things with “Like” or “Dislike,” “Fresh Tomato” or “Rotten Tomato.”

But great movies are like city parks: They invite you to explore, and your first exploration is just the beginning. Your first experience has as much to do with your own choices and preferences as it has to do with the park's design. Weather plays a role too, as do the other visitors who happen to be at the park that day. Go back again on a different day, in a different mood, and your experience will be different. Does that mean it’s a waste of time to bother with questions related to the quality of the park’s design and condition? Of course not. But it’s ridiculous to think we can pronounce a judgment on any work of art. Too much is conditional. Better to share impressions, keeping an open mind so we can be surprised and have that distinctively human experience of changing our minds.

I’ll probably expand this list in March and April as I catch up with films that got away. For example, Gunda isn't available yet on streaming platforms, but critics who found access to it have praised it as one of the year's greatest achievements. Others — City Hall, Beanpole, and Collective — are films I haven't watched yet for reasons related to timing, mood, or rental prices. I'll get to them soon. I'll go on revising the list as my appreciation of these films changes. I recently updated my lists from the 1970s!

I watched more than 150 movies in 2020 — eagerly pouncing on new films, happily revisiting personal favorites, and making new discoveries from decades past.

But let's focus on the newer stuff. Here's to 2020, a year that would have been so much more difficult if we hadn't had the blessing of movies.

40.

The Painter and the Thief

directed by Benjamin Ree

https://youtu.be/3yJ4r7ON974

For a detailed, thoughtful perspective on this provocative film, I recommend you read what my good friend Alissa Wilkinson, film critic for Vox, has to say about it. This is her #1 movie of 2020.

She writes,

The Painter and the Thief actively challenges what we think we understand about its characters based on their appearance, class markers, or behavior. It highlights the way artists of all kinds, from painters to filmmakers, turn reality into something that’s at least a little fictionalized in order to make their work, and how everyone conceals the truth at times. And then there’s its last shot, which you’ll never forget.

I can understand her enthusiasm. I greatly admire this film as well. As we watch the Czech painter Barbora Kysilkova paint portraits of Karl-Bertil Nordland, a young man convicted of stealing her artwork, we are challenged with questions — some of them troubling — about artistic motivation, about the intimacy that can develop between an artist and a subject, and about the ethics of documentary making. I end up admiring it more than I love it. Director Benjamin Ree's focus meanders in ways that keep me at a skeptical distance.

It's a compelling story. And its two complicated, photogenic subjects make for compelling characters. As Barbora and Karl-Bertil grow closer, it's difficult to discern the artist's intentions. Is her work helping her and her troubled subject move through hardships and neuroses? Or are they developing a dangerous co-dependency?

The person I find most compelling was Barbora's partner, actually, who is clearly unsettled by where the artist's experiment was leading her. So am I. Yes, there is a compelling illustration of Jesus' call for us to "love our enemies" here — but I can't shake off my concern that there is something about Barbora's interest in this troubled man that is more self-serving than loving, and the fact that she's living out these intimate, personal moments for an audience in front of a camera increases my unease about it.

This is one of those documentaries in which I am constantly distracted by the degrees to which the artist and subject might be collaborating in order to coax events in certain directions for the drama it can bring to the movie. Some scenes that I'm seeing play out in front of the camera — particularly scenes of high emotion — inspire more distrust than belief. As the documentarian zooms in on intimate conversations, I just keep thinking "There's a camera — and a cameraperson! — right there. And the subjects don't acknowledge it. In view of that, I have to wonder — how much are they acting?"

Still, I recommend it for the conversations it will inspire, and for how it might — inadvertently — become a cautionary tale for artists and audiences alike.

39.

The Willoughbys

directed by Kris Pearn; co-directed by Cory Evans and Rob Lodermeier;

based on the book by Lois Lowry; written by Pearn and Mark Stanleigh

https://youtu.be/HnG4ag3Nkes

Yes, I'm as surprised as you are to find this on my year-end favorites list. I may be the only critic who thinks so highly of it. And I'm sure I'm going to inspire concerns about my judgment when I say that I enjoyed this more than both of Pixar's movies this year.

What can I say? The Willoughbys made me laugh more often than Onward did, and I found that I enjoyed the company of its characters more than I did the odd couple in the spotlight of Soul.

I've never read the book, so I don't know how faithful it is to its Lois Lowry source material, but the film would seem merely formulaic and unnecessarily frantic if it weren't for a surprising hit-to-miss joke ratio which keep surprising me. I like its spirit of inspired mischief and high-speed mayhem, and, like so much great children's literature, it has a meaningful darkness to it related to child abuse and the need for empathy and love.

Director Kris Pearn pumps the movie full of bold colors and exaggerated style. The result is like a fusion of A Series of Unfortunate Events, Charlie & the Chocolate Factory, James and the Giant Peach, and Mary Poppins — with a touch of Moonrise Kingdom ("Social Services" there is "Orphan Services" here). But it manages to distinguish itself from its inspirations.

And the Bad Nanny character played by Maya Rudolph is pure joy.

38.

The Assistant

written, directed, produced, and edited by Kitty Green

https://youtu.be/DzLWA3xIcFo

If you're listening closely to the "incidental" talk in the opening minutes of The Assistant, you hear several references to "grosses" and "biz affairs." These are mentioned literally, with no insinuations... but for those with ears to hear, it's clear that this screenplay is layered with clever double-entendres. Yes, indeed — the business affairs here maximize the, um, gross.

And from the sickly color scheme to the sound design (emphasis on buzzing fluorescents, the cold steel box of tissues scraping across a desktop, etc.), everything seems calculated to accentuate unease as we following the daily routines of an assistant to a major Hollywood studio executive. She's young, she's talented, and she has scored a job that thousands more covet — a seat within reach of a Man Who Can Change Lives and Grant Fortunes. The name of the Assistant, played with convincing anxiety and humiliation by Julia Garner, is Jane — of course: an obvious choice to emphasize the replaceability of her character. The camera focuses on her menial tasks that contribute, piece by piece, to our understanding of a monster — one who remains, like the shark in Jaws or the monster in Alien, mostly unseen. He's the the sort of predator who thrives in a context of Capitalism Without Conscience.

Writer and director Kitty Green does all of this very artfully, painting an effectively truthful portrait of systemic misogyny (and, of course, very specifically, of Harvey Weinstein). From the first time we see the two men who share the office and who treat Jane as if she were an AI service — they might as well have named her 'Alexa' — it's clear whose sufferings we are here to witness and grieve. As she prepares the office, cleans the casting couch, and picks up a hoop earring from the floor and tucks it in a drawer as if she's done this many times already, we can see the compromising position she's in.

So, it's clear what this is about, and what it's going to be about, for the duration.

Is there more to it than a sort of one-note lament for the countless women who have been chewed up and spit out by this system?

I'm not sure there is. Yes, it's exciting to see another major motion picture written and directed by a woman in a year that has given us quite a few of them. It's an encouraging sign of (overdue) progress.

But as scene after scene plays out, we just see example after example of the many and varied abuses of power and of the corrosive effect of complicity on the conscience and well-being of workers. Every little line contributes in a way that reaffirms what we know about such abuses, like a reference to a change in a screenplay that will "have has ripple effects a long way down the line," just as every decision reinforcing this system will go on doing damage for years to come. Some of the things Jane says to others in distress are clearly the things she needs to hear but never hears: "It's not your fault." And some of the incidental things the others say are revealing in themselves, like a new assistant (or victim) in training learning the phones and saying, "I can't figure out how to dial out." Neither can we, you poor thing. Neither can we.

About an hour in, though, I have very little to think about — just more to suffer through, more reasons to feel sorry for someone, more reason to wish Someone Else had never been born. Every scene is calculated to increase our revulsion and righteous anger, and to feel empathy for the trapped and the abused. It's accurate. But is it interesting? Is it leading us somewhere? Is there an arc to this story? Does it just insist on its one ugly understanding? Many of the reviews I've read go on about the brilliance of the mis-en-scene, and I can't argue with that. This is a fine example of what cinema can do that other forms of art cannot — it creates an immersive environment, an unnervingly slimy aquarium that we soon cannot wait to escape. But is the mis-en-scene opening up new questions, deepening the implications? I keep waiting for something that feels like discovery or revelation. Instead, it feels like a context for a film in which we wait for something to happen.

I can't help but imagine what someone with a vision beyond "I'm gonna show them what really goes on" might have done with this. I thought about all that David Lynch has already done with this. (Heck, even Woody Allen did more with this scenario way back in Crimes and Misdemeanors, and that was just one subplot in a web of stories. I wonder what Anna Rose Holmer might have done with this, or Kelly Reichardt.)

On the same day I saw this movie, I read an interview in Vulture with the actress Thandie Newton. It gave me a much richer portrait of tyranny, misogyny, perversion, and complicity. It was complicated. I learned from it.

Now, having said that, I'm glad The Assistant exists. I think it might come as a wake-up call to some in the audience who don't pay attention to the news. It paints the ugly truth bluntly. This kind of systemic exploitation and harm happens everywhere — Hollywood, universities, megachurches, small churches, non-profits. The White House. It happens in the service of powerful men and women. It can happen wherever there is privilege, and wherever there is a queue of young people eager to get a foothold in the industry of their dreams, ready to pay prices and kiss rings.

I have some friends who, having suffered a long time in silence, recently worked together to find greater strength in numbers. They stepped up and spoke up about their mistreatment, and about the things they were told — from unkept promises to humiliating insults to quiet threats — in order to keep them on the line, to keep them around as attractive and resourceful servants, contributing to Someone Else's success and bolstering Someone Else's reputation. (I might not have believed their grievances except for the number of them and the overlapping details. What's more, I'd witnessed a few alarming flashes of misbehavior myself, when nobody else was looking; I'd experienced some demeaning comments that starkly revealed to me how little I and my work really meant to the Person in Charge in spite of the compliments I'd received from him before.) When they saw someone new walking in, oblivious to the mistreatment most likely awaiting her, they would not stand for it. They acted.

It won't happen again.

37.

Let Them All Talk

directed by Steven Soderbergh; written by Deborah Eisenberg

https://youtu.be/Ljf8DOZBnoA

I came for the Wiest, I stayed for the Bergen.

Playing Alice Hughes, an author so self-absorbed that she dismisses her Pulitzer as too commonplace to discuss (although she'll be sure you don't forget about it), Streep is basically playing the rich and intellectual and, thus, disconnected from "the common person" sort that Catherine O'Hara plays with such verve and genius on Schitt's Creek. She's just dialing down the exaggeration in order to fit in with more recognizably "ordinary" characters.

And she's clearly having fun, speaking in the most casual situations as though she's still at the microphone philosophizing about the cosmos and consciousness, her hand directing some unseen ballerina. But she's also clearly "Acting" — something that often puts me off of The Great Streep's work. I guess I can understand it here, though, as Alice, her character, is sustaining a crafted, cultured, heavily mannered persona that she probably learned from listening to other prestigious authors. The center of this seemingly spontaneous, meandering comedy — if it has one — is just that: a crisis that quietly smolders between the writer and the old friends (one loyal, one grudge-bearing) she brings with her on a cruise. She has become, perhaps a little too willfully, someone Else, someone her friends can't connect with easily anymore, someone so drunk on her own perceived superiority that she doesn't know how to just hang with her friends anymore. She can't find her non-performative self anymore.

So, I suppose it works — Streep playing this character.

And yet, I suppose that also speaks to why I didn't find Alice's company nearly as enjoyable as the company of her friends Susan and Roberta. I suppose that's why the movie loses me in the final act — it seems to be built on the assumption that Alice is the character we're most invested in. And she isn't — not for me anyway.

Dianne Wiest always seems so effortlessly human to me — yes, even in Edward Scissorhands — and it's such a joy to take this ride with her. As Susan, she's the loyal, feisty, and empathetic friend who might seem sweet and grandmotherly if not for occasional bursts of temper or, in one cast, a startling personal footnote that suggests she's led a far more, um, colorful life than we'd ever guess.

And then there's Candice Bergen, playing Roberta, who has come along in the hopes of finally settling a score over what she perceives to be a personal violation, a public humiliation in the plotline of Alice's most popular book. In her quiet fury, Bergen is so good that she comes close to rocking the boat with her fierce, scene-stealing silences and flashes of side-eye.

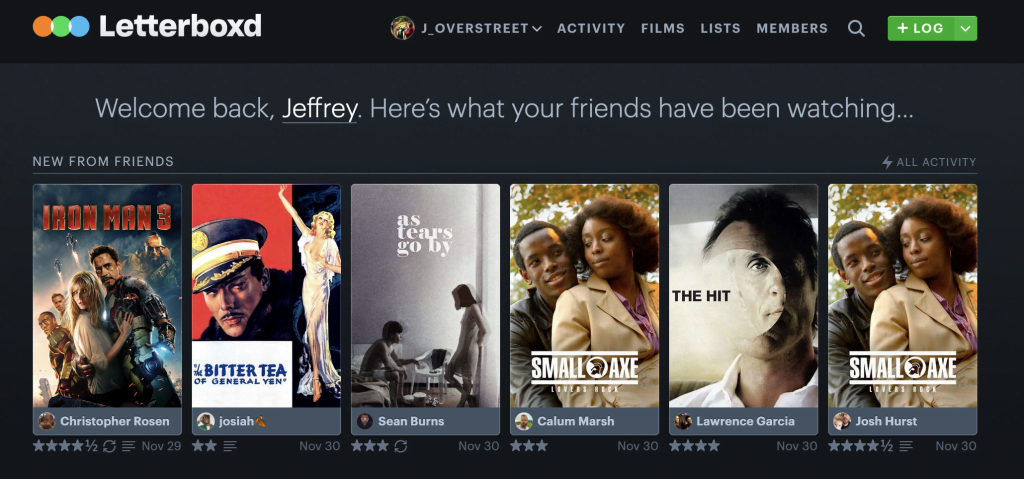

On Letterboxd, Matthew Sibley labeled this "Soderbergh's The Trip," and now I can't stop thinking about how much I want sequels in which Wiest and Bergen get caught up in a variety of road trip movies.

I could go on about how perfectly Lucas Hedges and Gemma Chan fit into this chemistry set of personalities. Hedges, who may be the most frequently cast actor of his generation, made me forget that I hit my Hedges Saturation Point a while ago. He's funny and endearing here. And Chan is almost as radiant as she was in Crazy Rich Asians.

But what interests me most here is Soderbergh — precisely because he didn't interest me while the movie was happening.

Maybe the best compliment I can give him here is that I kept forgetting this was his film. And that's his distinction as an auteur — he's a shapeshifter, capable of such deliriously stylish genre games (The Limey, Out of Sight, Ocean't 12, Haywire), such unsettling investigations into distortions of love and need (sex, lies, & videotape, The Girlfriend Experience), and such giddy "What if?" experimentalism (Kafka, Full Frontal, High Flying Bird). He disappears into what interests him.

I wish there were more directors like this, artists who I don't find myself thinking about — and, more importantly, who don't give me the sense that they want me to be thinking about them — while I'm watching their movies. It's the art that matters, and when a writer or a filmmaker forgets that and starts falling in love with the sound of their own voice, the art — and, in most cases, the audiences (or, in the case of Alice and Company, the friendships) — will suffer.

During the brief season of my life when I was speaking and doing interviews about my writing, one of my biggest fears was that the attention — and my publishers' reasonable interest in helping me cultivate that attention — would change me, make me seem a fraud to my friends, and disrupt my relationships. Fortunately, I wasn't successful enough for that to become a serious threat. (And the friendships are fine.)

But I've been on the other side of that dynamic in cases of greater disparity. A wise friend of mine once warned me about developing friendships with others who are wealthy or famous: "In almost every case, they end up having all the power in the relationship. You get a subtle and unhealthy satisfaction out of being close to power, but they only get satisfaction so long as you're useful or convenient. It rarely ends without someone — probably you — getting hurt." I've known people whose work suddenly gained a lot of attention and, just as suddenly, our friendship proved conditional on my response to their work; or, in other cases, it became clear that the urgency of More Important Relationships revealed ours as expendable. So this movie, for all of its playfulness and improvisational spirit, explores some territory that's important to me.

Maybe this is getting a bit too ponderous for a review of this film, which is an enjoyable jaunt and not a lot more. But I'm talking about why I wouldn't have been able to sit still during Alice's Author Event and Q&A on this cruise, or been able to endure an hour at her table. I would rather have been off reading a good book. I would rather have followed Susan and Roberta around some more. I'm low-key hoping that Soderbergh has the same impulse.

36.

The Quarry

directed by Scott Teems; written by Teems and Andrew Brotzman;

based on the novel by Damon Galgut

https://youtu.be/EBY7fzCeKNE

I reviewed The Quarry in-depth here at Looking Closer when I saw it. You can read that here.

I also interviewed director Scott Teems and his co-writer Andrew Brotzman in a special Summer Stage event hosted by Image.

35.

Bad Education

directed by Cory Finley; written by Mike Makowsky

https://youtu.be/kbCy6X0JPrU

"When things are going well, who wants to go hunting for problems?"

And yet, integrity is better than happiness or "success." That's why we need journalists, whistle-blowers, and people of conscience to keep us honest.

What a story this movie tells. I haven't read the investigative journalism that it's based on, so all of the surprises worked on me. It's crazytown.

It's terrifically entertaining, but it's not particularly impressive as cinema. It's greatest strength is its ensemble cast: Janney is fierce as usual here, but this is Jackman's show — he's complicated and fascinating to watch. It may be his strongest performance yet. But there's not much poetry here — I can think of one all-caps metaphor in the whole thing (the leak in the ceiling).

Still, after four years of seeing this kind of corruption in the highest echelons of American government at a scale that staggers the imagination, knowing I'm not ever likely to see those responsible brought to justice (in this life, anyway), I found this story of journalists exposing elaborate cover-ups and bringing con-artists to justice just... well, cathartic. As a study of the way in which small lies lead to bigger sins — seemingly at the same rate that small rationalizations can quickly balloon into massive states of denial — it feels true to life.

Some have described this film as a comedy or even a satire. I think that's a miscalculation. This felt to me like it was played perfectly straight.

I've lived my life among passionate, selfless teachers and ambitious, driven administrators. And I've struggled to understand why there is often a contentious divide between them. Similarly, I have seen an almost irreconcilable divide in so many churches I've been a part of. There's a divide between those in leadership who focus on "growth" and headline-making achievements as measures of success, and those who find the real joy in meaningful service. Great teaching happens in a dynamic of intimate personal relationships; those who focus on numbers and engaging in the competitive market are playing a different game with different priorities. Both want what's "best" — but their definitions of the word are strikingly different.

So I recognize these characters: the teachers who want to make a difference for the students they love, the administrators who focus on national rankings and dazzling their investors.

And as a teacher, I've sensed how addictive the spotlight of Attention can become, how easy it is to become distracted by the desire for strong evaluations. When the desire to teach effectively morphs into a desire to for adoration, we forget that true Greatness is about integrity. No other measure of success matters. If we forget that, we become the tragic figures we once studied in our Shakespeare classes.

34.

Ma Rainey's Black Bottom

directed by George C. Wolfe; written by Ruben Santiago-Hudson;

based on the play by August Wilson

https://youtu.be/ord7gP151vk

Director George C. Wolfe's Netflix adaptation of the stage play Ma Rainey's Black Bottom is strong but modest, handsomely produced, and filmed with intimacy but without much imagination. It's compelling because the great August Wilson's writing is savory and often stunning — of course it is! But as a movie it achieves liftoff because of its two equally powerful jet engines: Viola Davis and Chadwick Boseman, both giving everything they have.

I'll be the first to cheer if Boseman is honored with a posthumous Oscar. The loss of this extraordinary actor, best known for anchoring Black Panther, was the worst gut-punch of the year in celebrity news. He's very good, and the courage and stamina it must have taken to play this part (considering the advanced state of the cancer that was killing him) is amazing. I think it's likely to happen, considering the intensity of his Big Scene. And if it does, it will make for a moving and meaningful Oscar moment. But when it comes to movie magic, I was more moved by his quieter presence and subtler moments in Da 5 Bloods.

Still, Viola Davis is every bit as powerful, making Ma Rainey an unpredictable tornado of grudges and grief. As she moves from punishing her exploitative show-business oppressors for their disingenuous praise to thrilling us with convincing blues performances (sung mostly by Maxayn Lewis), she wins our sympathy and our cheers.

In composing this lament over forms of exploitation and abuse that are distinctly American and still going strong, Wilson offers us a sobering historical account. In adapting this for Netflix, Wolfe and screenwriter Ruben Santiago-Hudson have given us a provocative, engaging experience of Wilson's play. But even though I've never seen the play before, I think it feels substantially abridged, as if they were worried about audiences tiring of a talk-heavy drama that takes place in these few recording-studio spaces. I suspect artists with more cinematic imaginations might have explored and discovered more rewarding images and interludes. Watching this, I'm always perceiving it as a strong theatre ensemble acting for cameras instead of a live audience, and modulating their performances appropriately.

And I end up wishing I could have seen it onstage. Perhaps if I could have seen the whole play, the climactic scene might have been more resonant, felt more earned. Instead, it feels strangely abrupt, insufficient, and almost arbitrary.

Still, I'm glad we have this, more for the joys of seeing these two extraordinary actors in such fantastic form.

And I really hope that the blu-ray release will include outtakes where we see what really happens when Davis chugs a whole bottle of Coke. I mean, you know they have that footage somewhere, right?

32-33. (tie)

Rewind

directed by Sasha Neulinger

https://youtu.be/Dx0q7ETJRAI

This is one of those films where, every few minutes, as graphic details are spelled out in words and pictures, details we don't ever want to know, I find myself squirming and saying — Really? Do we really need to have these spelled out for us when the nature of this evil is already clear?

And then, as the scope of the project broadens and the purpose of these decisions becomes clearer, I answer myself — Yes. Yes, it is necessary. It is necessary for the liberation of victims. It is necessary for justice. It is necessary to seek to awaken some relic of conscience in the hearts of the guilty, that they might stand up in their shame and shout out "Give me some light!" Or damn themselves in refusing.

As documentary art goes, this is pretty standard stuff. As a necessary and vital testimony, a work of truth-telling that will make the world a better place, it is essential.

We're watching a young man make a daily, hourly practice of retracing the truth, hearing the truth spoken again, and speaking the truth again himself — because the truth will set him free, step by step by step. And by sharing the truth, others might be set free too.

We're also watching the unsurprising truth that the rich and famous get to live above the law, by completely different rules than the rest of us.

Let us not forget that God sees this happening too. And God will not be mocked. May God establish justice and show mercy as God sees fit in the name of Love.

Time

directed by Garrett Bradley

https://youtu.be/kq6Hh07oLvs

That show To Catch a Predator drew audiences with the lurid promise that they would see a sex criminal caught taking the bait set by a collaboration of both the entertainment industry and law enforcement.

This movie takes that idea and improves upon it by reversing it: Here we see an individual, Fox Rich, without any apparent conflict of interest — I don't sense any decisions made here for the sake of entertainment — commit countless hours of her life and her community's lives to the camera so that she can (repeatedly!) set the bait and catch a system — or, rather, an Industry — toxic with racism, classism, and cruelty.

And wow, does she ever catch them.

I often have mixed feelings about the disruptive roles that documentary cameras can play in documenting the "truth" of righteousness and wrongdoing. People doing the right thing behave differently when they know they're on camera. I had those questions watching Rewind, a 2020 documentary about the uncovering of sex crimes against children. And I have the same questions here, as the Rich family and their supportive community campaign for a re-sentencing of her incarcerated husband. The film has so many meaningful moments, and they are all captured by a collaboration of people eager to present their case as the righteous and the wronged. We see them saying profound and inspiring things, campaigning for a good cause, demonstrating superhuman patience and resilience, and bonding with others who have been wronged. It's not that I think they're terrible or dishonest people, these champions of justice. And hey, if making a movie of their long-suffering fights was in any way empowering and motivating, I'm glad they did it!

But I want to believe in the authenticity of everything I see here — that the cameras caught the truth of what was happening and would have happened without those cameras, and that what I'm seeing was done without any thought of how the "performances" would "look."

And I think I do.

And when I believe, I am moved — especially by the last act, which only works if what we've seen leading up to it can be trusted as genuine.

Let me be clear: My misgivings about movies like this stem from a clear-eyed awareness of how media can be sculpted to make heroes of its makers and villains of those they despise.

But I have no doubts that systemic racism in America's systems of "law and order" is inflicting far greater crimes on many — if not most — of those incarcerated than the crimes for which those individuals were arrested and entombed in a hell of hopelessness.

And this film's powerful documentation of the appalling indifference of America's heartless and ravenous mass-incarceration holocaust machine, which claims to represent justice but which routinely chews up and spits out Black Americans and their families and communities, is a necessary and hard-won point scored for justice, mercy, and love.

May God, according to the laws of physics that God established, bring about in response to the wrongful actions documented in this film an equal and opposite reaction. Let justice roll down.

31.

Small Axe: Education

directed by Steve McQueen; co-written by McQueen and Alastair Siddons

https://youtu.be/9uxPGMubvbQ

I shared my thoughts about this final film in filmmaker Steve McQueen's remarkable five-film series Small Axe on the Looking Closer podcast. You can listen to that 10-minute Cutaway Episode here:

30.

What Did Jack Do?

written and directed by David Lynch

29.

On the Rocks

written and directed by Sofia Coppola

https://youtu.be/Xn3sK4WiviA

Or, Comedians in Cars Chasing Possibly Unfaithful Husbands.

I seem to remember that when this opened a bunch of critics rushed to assure us that this isn't meant as a companion piece to Lost in Translation — that it's something very different, and we shouldn't go in expecting to swoon over this film the way we did that film. I guess that's good advice — but not because this is frivolous or any less thoughtful. It isn't!

This is a very different story about the challenges of marriage further along the road than poor young Charlotte's. And it focuses on two very different characters. Rashida Jones's Laura is a busy mom, a frustrated writer, and a wife who has good reason to worry that her relationship with her husband might need serious attention. Murray's character — Felix, Laura's father — is far less charming than suave, mischievous Bob who was mentor to Johansson's Charlotte; Felix is abrasive, pushy, full of maddening speeches about "the male of the species," and downright upsetting at times in his pride and privilege.

But the conclusion (and I need to be careful here to avoid spoilers) has a moment that is a perfectly calibrated revision of a memorable flourish from Coppola's earlier masterpiece — a gesture as fleeting as a wink, but that that strikes me as a mark of wisdom and maturity.

That isn't to say that I think Lost in Translation is immature — it was just the right movie for that much younger filmmaker, an expression of frustration with betrayals and of longing for something true.

And this film is just right from someone older, wiser, willing to express that those hopes for something fulfilling might not be in vain after all.

Too cryptic? Let's talk sometime.

28.

The Personal History of David Copperfield

written and directed by Armando Iannucci;

based on the novel by Charles Dickens

https://youtu.be/xXh53I-Sdsk

If you're looking for a high-spirited new film to watch after your family's multi-generational Thanksgiving feast, and you want to please everybody in the crowded house, well, you could do worse than...

... oh. Wait.

Right.

Take #2:

If you're looking for a high-spirited new film to watch while you eat a plate of homemade nachos and try not to think about all of the usual Thanksgiving festivities that wise and charitable Americans are avoiding this year — for the purpose of showing love to others — you could do far worse than this ebullient celebration of literature, kindness, and generosity.

The cast is radiant — Dev Patel is winningly flamboyant; Tilda Swinton is even cleverer than usual; Hugh Laurie is a joy in a role that might otherwise have gone to Bill Nighy; Ben Whishaw is (I'm going to invent a term here) positively Crispin Glover-ly; Peter Capaldi looks like he was born for his costume; Gwendoline Christie revels in imperious severity; and Rosalind Eleazar is the warm and reassuring calm in the storm.

Sure, it's a Cliff's-Notes rush. I guarantee that those who demand faithfulness to the novel will be irked. And no, it doesn't all work. At times, it gets so boisterous as to seem like it's turning into a spoof of Dickens adaptations. (In its most meta moment, characters turn and comment, confounded, at the presence of a character who really has no business being in the scene at all.)

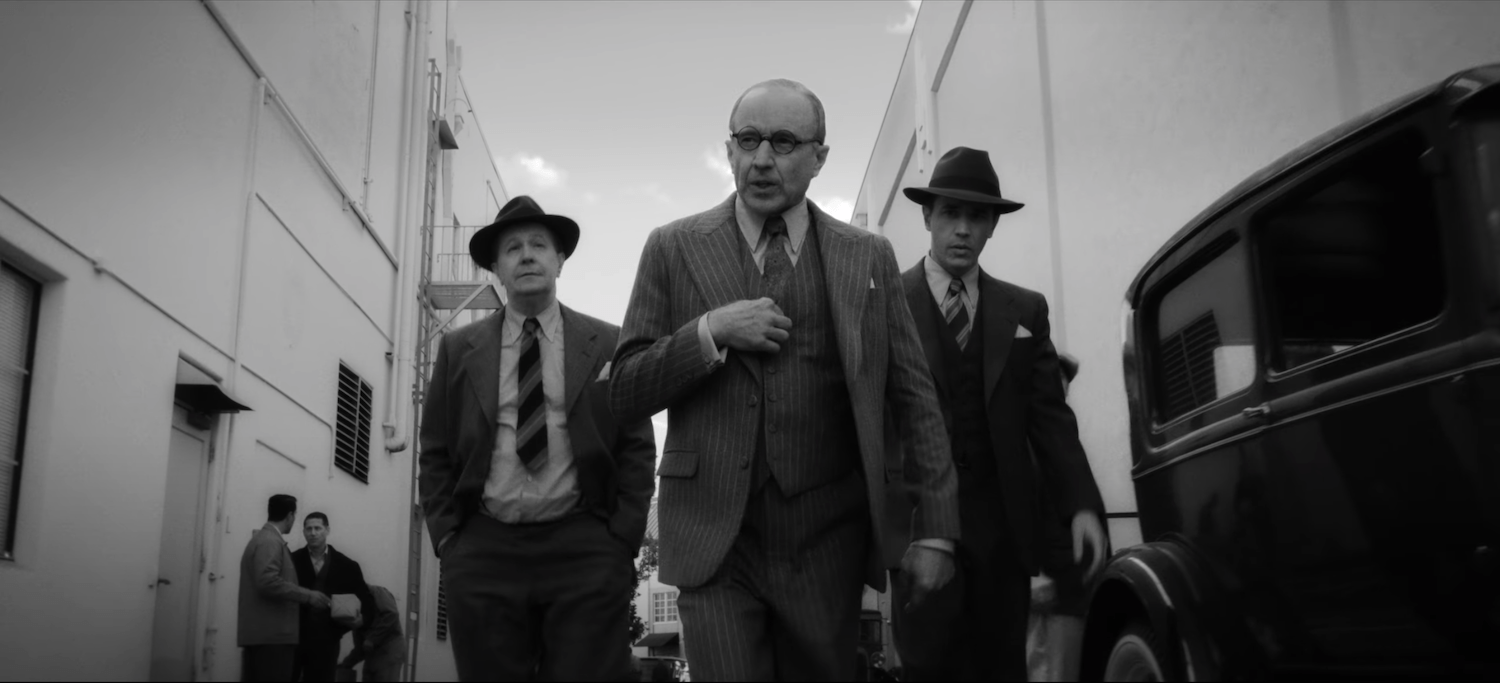

But I suspect that anybody who has become accustomed to Baz Luhrmann circuses will find Iannucci's extravagance refreshingly well-behaved by comparison. What's more, I sense sincerity in its heart — not what I'd expect from the writer who brought us In the Loop and The Death of Stalin. And I sense possibility in its imaginatively diverse casting. This is not your parents' PBS period piece.

At the end of a long and dispiriting week, this may not have been the kind of party I've been longing for, but it'll do until that party becomes possible.

27.

Tesla

written and directed by Michael Almereyda

https://youtu.be/e4U-23TOKms

Fun with light.

Accent inconsistencies aside, Ethan Hawke's despondent-Batman voice is my mood right now.

I'll bet Kyle "Agent Cooper" MacLachlan relished the chance to spark a current between this film and the Lynch-verse: "Gotta light?"

Maybe it's just that I miss the joy of sitting in a theater and being dazzled by the unexpected, but — watching this at home, being frequently surprised, and for a few blissful moments forgetting what cruel and heartless men are doing to my country outside — I really, really enjoyed this portrait of a man whose imagination was too busy, too in love with possibility, for him to take the path of the devil.

26.

Rocks

directed by Sarah Gavron; written by Theresa Ikoko and Claire Wilson

https://youtu.be/CqXhMYjasHM

Radiance and resilience — this is a deeply felt, seamlessly convincing story of a spirited young student called "Rocks" who seems like one of the stabilizing forces in the typically mercurial social circles at an all-girls school ... that is, until her mother disappears, leaving her alone with her younger brother Emmanuel.

This window on an immigrant community is believably bleak but also surprisingly hopeful in reminding us how relationships among young people can break and be repaired again in a matter of days. What's more, it also takes a somewhat hopeful view of social services — a rare thing at the movies, and not the first time that the movie made me think of The Florida Project. Newcomer Bukky Bakray is engaging in a seemingly effortless performance; we don't just care about her for her sufferings — we love her for her humor and her strength.

This is my first Sarah Gavron film. Maybe I should look back at previous work. (Sufragette didn't look promising back in 2015.)

25.

The Invisible Man

written and directed by Leigh Whannell

https://youtu.be/WO_FJdiY9dA

For at least 90, maybe 100, minutes, I thought that Leigh Whannell had made the most effectively scary — and almost heavy-handedly "relevant" — thriller I'd seen since Get Out.

But then I guessed a major twist, which was disappointing.

And then the last five minutes of the movie managed to go for the absolute worst of the endings that I was imagining possible. It's a crowdpleaser, but it indulges the audience's worst impulses, and the film spoils its chance to glean wisdom from its mess of trouble. I sat there saying, "No no no No No No NO NO NO."

(Sigh.)

This thing had greatness within its reach... within its grasp. And then, it let greatness slip through its fingers.

But yeah, Elizabeth Moss is great. She's always great. This felt a lot like a turning-up of her Top of the Lake performances to '11.' I think her work with Jane Campion will remain my favorite thing she's done. She gets to play so many more notes in those two fantastic series.

So, why is this among my favorites? Because, while the film is not greater than the sum of its varying parts, some of those parts — some of those nerve-wracking scenes — are as good as suspense moviemaking gets.

I should mention here that Promising Young Woman, starring Carey Mulligan, is also an impressive thriller with a sympathetic sufferer at its center. But that movie revels in its vigilante justice from beginning to end, and I was never okay with the tactics it was, by way of celebration, endorsing. (Sure — the ending tries to excuse itself by saying, "Well, sure — this way leads to destruction," but it's hard to deny how much the movie enjoys its juicy revenge pageantry up to that point.)

24.

Tenet

https://youtu.be/AZGcmvrTX9M

You can read my review of Christopher Nolan's latest mind-bender here.

23.

Shithouse

written and directed by Conor Raiff

https://youtu.be/PkA7m1DbeH8

When Before Sunrise opened, I was the age of the characters in the movie. I loved them because they seemed so familiar. They reminded me of my friends. They reminded me of me. I believed.

Seeing the sequels every ten years has felt like a reunion.

As I discover this movie, I'm teaching young men and women that age.

I still love Before Sunrise. And this feels like it will be that movie for my students. These characters remind me of them. And this movie makes me care about them even more. I want them to find friends. To find love. To find their way.

I care about these characters too. In ten years, I'd be up for a reunion.

22.

The Vast of Night

directed by Andrew Patterson;

written by Patterson (as James Monatgue) and Craig W. Sanger.

https://youtu.be/ZEiwpCJqMM0

Another movie that is absolutely edge-of-your-seat fantastic — a surprisingly fresh treatment of genre cliches — that brings us right up to the final moments and then abruptly loses the courage of its imagination. I loved this so much until its opted for an underwhelming conclusion. I can't wait to see this filmmaking team go to work again — hopefully with a knockout final act.

Here's what I wrote after seeing The Vast of Night.

21.

American Utopia

directed by Spike Lee; screenplay by David Byrne

https://youtu.be/lg4hcgtjDPc

You may find yourself... burning down the house.

You may find yourself... like humans do.

You may find yourself... on a road to nowhere.

You may find yourself... coming to my house.

You may ask yourself... how did he work this?!

Whatever the case, this audience was so, so lucky. Once in a lifetime, indeed.

Spike Lee is having himself a year! This is one of the best concert films I've seen since, well... Stop Making Sense. But where that film's frenzied performances were perfectly "suited" (sorry) to the songs about anxiety, these are staged to invite us into a more thoughtful, meditative place... and, at times, to elevate us with joy.

Welcome to HBO Max, Overstreet. This might prove to be worth a month's subscription after all!

20.

Vitalina Varela

directed by Pedro Costa; written by Costa and Vitalina Varela

https://youtu.be/-wsY9RsufuI

"So why fear death?

Be scared of living...."*

Pedro Costa's new film shows that to reckon seriously in art with the resolute silence of death may lead to something more haunting than any ghost story. To confront that void intently can make ghosts of the living.

Thus, the spirit-like strangeness of each and every human being who emerges from the shadows that encroach on almost every frame. One by one, a parade of men moves between light and dark, hunched under burdens of grief, shame, or awkward confusion, coming to a dead man's house to pay their respects, trying to figure out what to do or say about the loss of one of their own. The departed Joaquim's absolute absence inspires so many words — there are a lot of lists recited in this film, as if those who knew him must take a sort of inventory in search of some kind of closure.

Vitalina Varela, the wife Joaquim left behind in a state of wounded betrayal, watches these men with (no pun intended) grave suspicion — as if they might know things that will answer her questions and heal her wounds. She has her own storm of thoughts and feelings about Joaquim, having arrived here in Portugal from her her immigrant home in Cape Verde to Portugal a bit too late for her husband's funeral. And it becomes clear that there are few words she can speak, few words anyone can say, that can help her release those thoughts and feelings — they burn like hell in her eyes; they roar like a cold wind in the deep lines of her face. (We might indeed begin to suspect that she is a ghost, but then comes another moment that grounds her in the concrete details of her surroundings — in fact, in one scene she's literally stricken on the head by the concrete details of her disintegrating ceiling!) Vitalina bears a unique suffering, increased by the layered loneliness of being a woman in a community where men respect only men... and being estranged from her husband's people by her identity as a Cape Verde immigrant who doesn't speak Portuguese. (She's told by a priest of dubious authority that, due to the language barrier, she cannot dialogue with the spirits.)

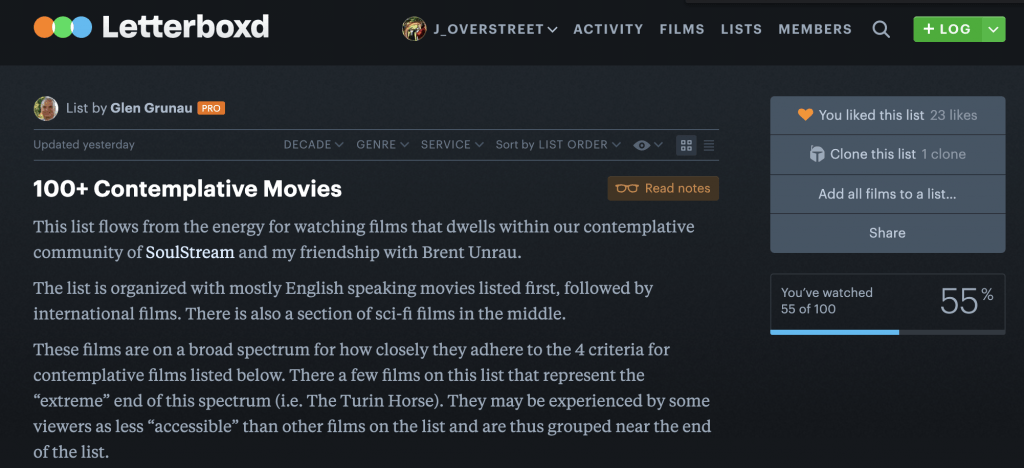

The film is an invitation not only to learn the story of this an angry and grieving widow, but to do the hard and lonely work of suffering these silences, these isolations, these questions with her. These are cinematic moments most storytellers or artists would pass by more the "more exciting" stuff — but I'm at a point in my moviegoing life when I'm often exhausted by activity, and I'm instead drawn to those onscreen moments when the busyness of human beings quiets down, allowing the possibility of Another Presence in the negative space to intensify. The cinema of Costa and his brilliant cinematographer Leonardo Simões will test the patience of those who watch movies to see things happen; he will reward those who wish to meditate on the most meaningful questions we can ask, or those moved by transcendently beautiful images of mysterious human beings. Each image is exquisitely textured and carefully composed to suggest we read it as we would read a poem. (I should probably award this film a higher Letterboxd rating, but the fact is that I feel there is just too much cultural and historical subtext that I'm missing, knowing as little as I do about Portugal and this community that Costa has found so compelling over his last few films.)

There's a curious irony in the fact that my belief in God grows stronger when I am gazing into the face of someone else who is seeking God. The priest makes a speech about God's face being split between light and shadow — and it's hard not to stop thinking about how almost every image in this film lives in that stark contrast. Vitalina herself is torn between darkness and light, always in danger of being swallowed up by the void, always interrogating the light with her fierce eyes, always tragically beautiful in what the light reveals of her suffering. The time that Costa invites us to spend with her, attending to her silences, gazing into the mysteries of suffering in her face and in others — a privilege and and a patience that reminds me of gazing into the faces of monks in Into Great Silence — humbles us before her as we might be humbled by a saint.

We want to see her find consolation and peace. She won't find closure in chasing a ghost. She won't get no satisfaction from men. She may find the beginnings of it in strengthening what remains, in building something new with her own hands.

*[I kept thinking of this line from Laura Marling's "Hope in the Air" as I watched this.]

19.

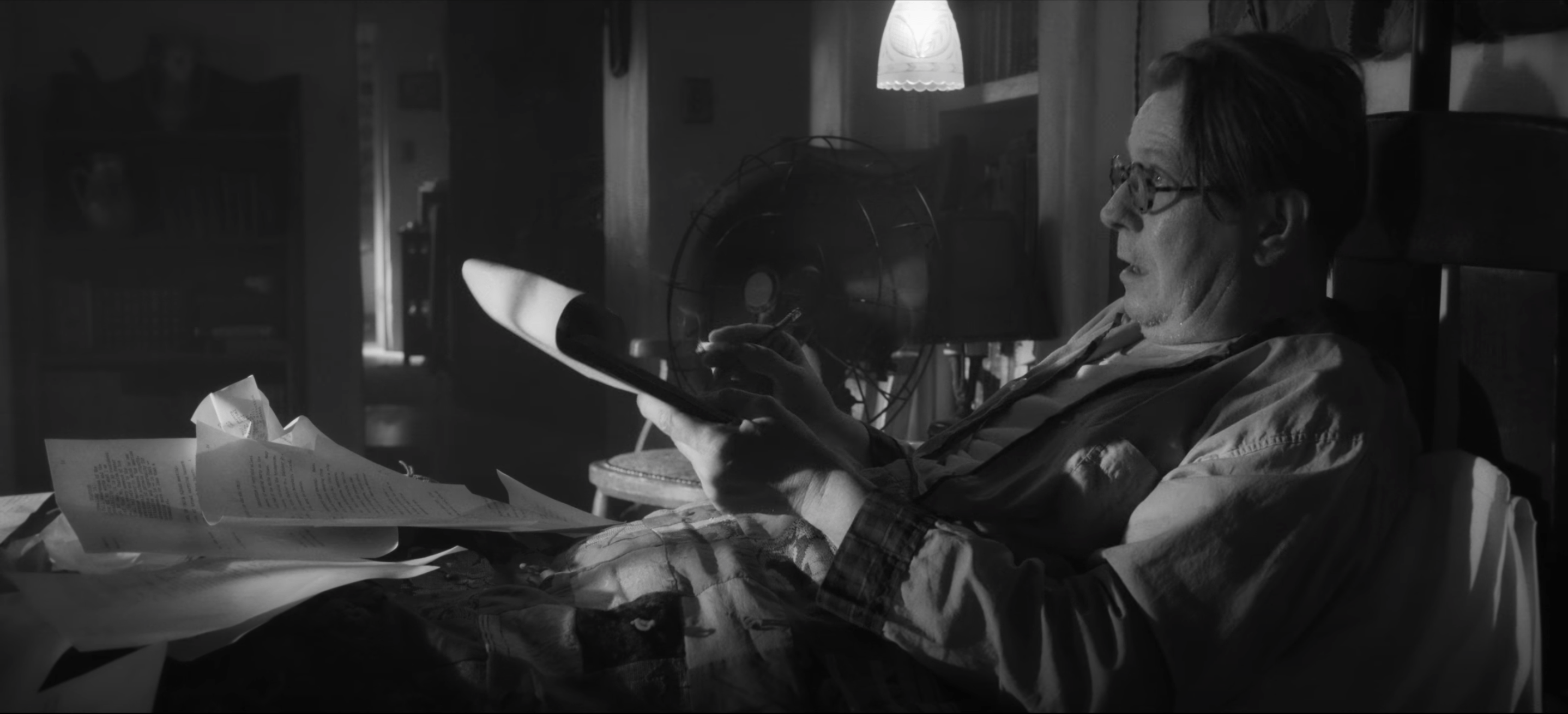

Dick Johnson is Dead

directed by Kirsten Johnson; co-written by Johnson and Nels Bangerter

https://youtu.be/wfTmT6C5DnM

[On Netflix.]

One of the strangest fulfillments of the Fifth Commandment I have ever witnessed.

Inspiring, surprising, unsettling, conflicting.

I'm not entirely comfortable with this project. Filmmaker Kristen Johnson — whose Cameraperson was my favorite film of its release year — acknowledges her misgivings about putting her subject, her own father, through myriad stagings of his pending departure, but the fact that she becomes increasingly concerned that his consent to stage these grim fantasies might be influenced by his increasing dementia does not put my conscience at ease. At times he seems truly skeptical and even distressed by the project, and the climactic pageantry, which I'm sure will deeply move many viewers, feels a bit exploitative, like a documentarian contriving drama as much for the cameras as for the good of the increasingly childlike and baffled subject.

But I cannot deny that this imaginative and playful tribute represents a singular and fearless act of... what? Love and... let's call it "celebratory grieving."

And it was harder for me to watch than I'd anticipated as Richard Johnson often looks so much like my father-in-law, who we lost abruptly and traumatically as the culmination of repeated hospital errors and incompetence last year. We didn't get to say goodbye. The former chief of staff of the very hospital he eventually relied upon for rescue was badly misdiagnosed and neglected in ways that led directly to his death, leaving his family devastated and sick with fury. God grant them peace. Dr. Frederick Doe is dead. Long live Dr. Frederick Doe.

18.

Sound of Metal

written and directed by Darius Marder; co-written by Abraham Marder

https://youtu.be/DkmDGBIEkO4

I won't soon forget about Ruben.

Wearing my film-critic hat, I'll point to about 30 minutes at the middle of this film (the stuff that comes after the obligatory "Angry Man Loses It and Smashes Everything In Sight" scene) and say this: It feels like some impatient moviegoer has hit Fast Forward and blazed through crucial chapters of the story. The film almost loses me there, and because we aren't asked to wait and, frankly, to suffer with Ruben as he does the hard work of learning, the rest of the film — which is much stronger — doesn't have quite the power it might have had.

But I have to take off the hat now and get personal. This film found a deep well of buried emotion in me and smashed it open.

My father began losing his hearing many years ago. A few years ago, it worsened to the point that I could not speak with him on the phone anymore, and since I only see him once or twice a year, that was difficult to bear. He has hearing aids, but they do very little good, and if he's in a crowded room, the noise congeals into an impossible cacophony. So he has withdrawn from community, lives with my mother, and sees my brother and the grandkids — but almost nobody else. His increasing isolation is harrowing for him — he's a former teacher who loves community and conversation. It continues to grieve me, day after day, that I have lost that joy of conversations with him, and that he has lost, one by one, so many friendships, so many communities, so many ways to contribute and serve.

Though it focuses on a person who could not be more different than my father, this movie draws us into what that experience of losing your hearing — and thus losing the life that you love — is like.

I'm grateful to find that it's a hopeful film, with a bold and affecting performance by Riz Ahmed at the center. And it's one of those that reminds me that, while I may think a film's artistry is significantly flawed, a movie need only do a few things well to become a profoundly meaningful experience.

I think I'll go email my dad.

17.

Driveways

directed by Andrew Ahn; screenplay by Hannah Bos and Paul Thureen

https://youtu.be/0-j1p-U7nKw

[I watched this streaming on Hoopla. See if you can access Hoopla through your local library.]

Three observant and compassionate studies in grief, Driveways follows a young woman who discovers the painful realities of her sister's lonely last days by cleaning out her overcrowded house; her sensitive little boy who tries to make sense of this difficult world by being patient and helpful to his mother even as he is drawn to the quiet kindness of the grizzled war veteran who watches the world go by from the front porch of the house next door; and that veteran, played with gravity and grace by Brian Dennehy (in a magnificent final performance that bumps my rating up a half-star).

I would have liked to see a stronger sense of visual poetry here, and some of the supporting characters are undercooked, seeming to have wandered into a Real Movie from a neighboring TV show.

But few films are as attentive to silences, and few capture that sense, in the days after heavy losses, of the need to speak and move softly.

And I found the unlikelihood and ease of these relationships to be comforting during what seems to be an increasingly abrasive and hostile time. And I was heartened by the film's respectful portraits of senior citizens in their VFW bingo games — most filmmakers would have played those guys for laughs, but these men seem like human beings.

It reminds me a little of of The Station Agent, although without the manic episodes, broad comedy, and need for Big Dramatic Turns. And it also reminds me of Chad Hartigan's This is Martin Bonner in its patience.

I'm going to keep my eyes open for more from director Andrew Ahn and writers Hannah Bos and Paul Thureen.

16.

Young Ahmed

written and directed by Jean-Pierre and Luc Dardenne

https://youtu.be/sTlhjBUikVw

This has happened before:

A favorite artist (or, in this case, artists) delivers new work that reminds me every minute of why I fell in love with them in the first place, and it stands up well alongside almost anything they've made before — but their tool kit has by now become so familiar that every minute, every beat, every aspect of the mise-en-scène makes me think of where and when I've seen them do that before. I'm more aware of the tool kit than the movie itself. The sculpture is new, but the materials are all recycled.

This happened for me with Malick's A Hidden Life. I suspect one day it may happen with Wes Anderson. And, as much as I care about the thematic territory the Dardennes are exploring here, it happened with Young Ahmed. Visionaries are visionaries because they teach you a new language, a new way of seeing. But it is not their responsibility to always be expanding that vocabulary with dazzling new possibilities. It is their responsibility to ask “What if...?” questions and then bear witness truthfully in their language to what they discover.

And they do. In a way, it seems like a very, very good imitation of a Dardenne brothers film by someone eager to make a film about the toxic allure of religious fundamentalism. It's a meaningful story, stirringly told.

It's just that the movie lacks the kind of standout performance or startling new idea that is likely to inspire and enthrall devotees of the brothers' filmography. Idir Ben Addi is fine in the lead role, but he doesn't have the kind of complicated presence that compels our attention like every Dardenne brothers' lead has had so far. And the abrupt conclusion, perhaps for the first time, feels a little contrived.

Others who may be new to the Dardenne brothers' singular style may find this more captivating than I did. Everything was reminding me of at least one, sometimes several, of their previous films. One moment seems modeled on a moment from The Son, the next from The Kid With a Bike, and on and on. It was like hearing a favorite band play a song with instruments they've played many times before, with chords they've played many times before, with pieces of melodies from songs they've sung before, and even a resolution very like things they've played before. It's still a damn good performance because it's that band — but the song itself lacks inspiration.

Do I recommend this film? Whole-heartedly. Do I think it's excellent? It's far better than 99% of the films people will watch this weekend. Perhaps this will be the movie that inspires someone to veer off of the highway of commercial entertainment and discover the riches of cinema. Perhaps it will inspire some to seek out other Dardenne films. I'm all for that. But will their familiarity with this film take away from or enhance their first experience with what I consider their masterpiece: The Son? Selfishly, I hope not.

And speaking of The Son, I so wish I had a way to share it with people. It's not available streaming anywhere, and there is no blu-ray release. DVD copies are rare and expensive.

Recently, I assigned Two Days One Night and The Kid With a Bike to eighteen undergraduates who had never seen a Dardennes film before. We discussed the films, and it was thrilling to hear their thoughts. Some of them were inspired and moved. That has only re-invigorated my gratitude for these filmmakers.

15.

Extra Ordinary

written and directed by Mike Ahern and Enda Loughman

https://youtu.be/x1TvL5ZL6Sc

"Come on, Martin. That ectoplasm's not going to collect itself."

And in context, that's actually a very romantic moment.

This is the most riotous laugh-out-loud surprise I've seen since Game Night, an out-of-nowhere ambush of laughs that starts small-scale and understated and builds to an insane 21-car-pileup of panic-attacks—a hilarious climax of normal (childbirth) and paranormal (Satanic virgin sacrifice) proportions. The joke density is impressively layered throughout. I’d love to see it become the first of a new Cornetto-style trilogy.

And Maeve Higgins's Rose Dooley just might end up being my favorite character of the year.

The world needs more comedies like this one that take big risks. I'm confident that no Ghostbusters sequel or reboot can come anywhere close to the magic this movie conjures.

14.

Another Round

directed by Thomas Vinterberg; written by Vinterberg and Tobias Lindholm

https://youtu.be/bj8Jmz_srDg

"To dare is to lose one's footing momentarily. Not to dare is to lose oneself."

Thomas Vinterberg is a filmmaker who dares — and thank goodness.

Something is buzzed in the state of Denmark. And it's given us the wickedly funny answer to the annoyingly popular genre of Inspiring Teacher Movies. It stops just shy of an "Oh Captain, my Captain!" moment.

Mikkelsen is just so good here — just nuanced enough to give the film real dramatic tension and thoughtfulness, just edgy enough to make the comedy cut.

So funny, so thoughtful, so playful. I love how an absurdity placed at the center of an otherwise realistic narrative can break open truths that are otherwise hard to express.

I don't know how I would teach with any effectiveness if I didn't sustain a sense of play, of joy, of daring. If I ever lose the spirit (not the spirits) that inspires teaching, the curiosity, the willing to ask "What if?" — please, help me recover it, or listen to where the spirit wants to lead me next.

Also: God save us from the inevitable American remake with Mortenson, Ferrell, Galifianakis, and McConaughey.

13.

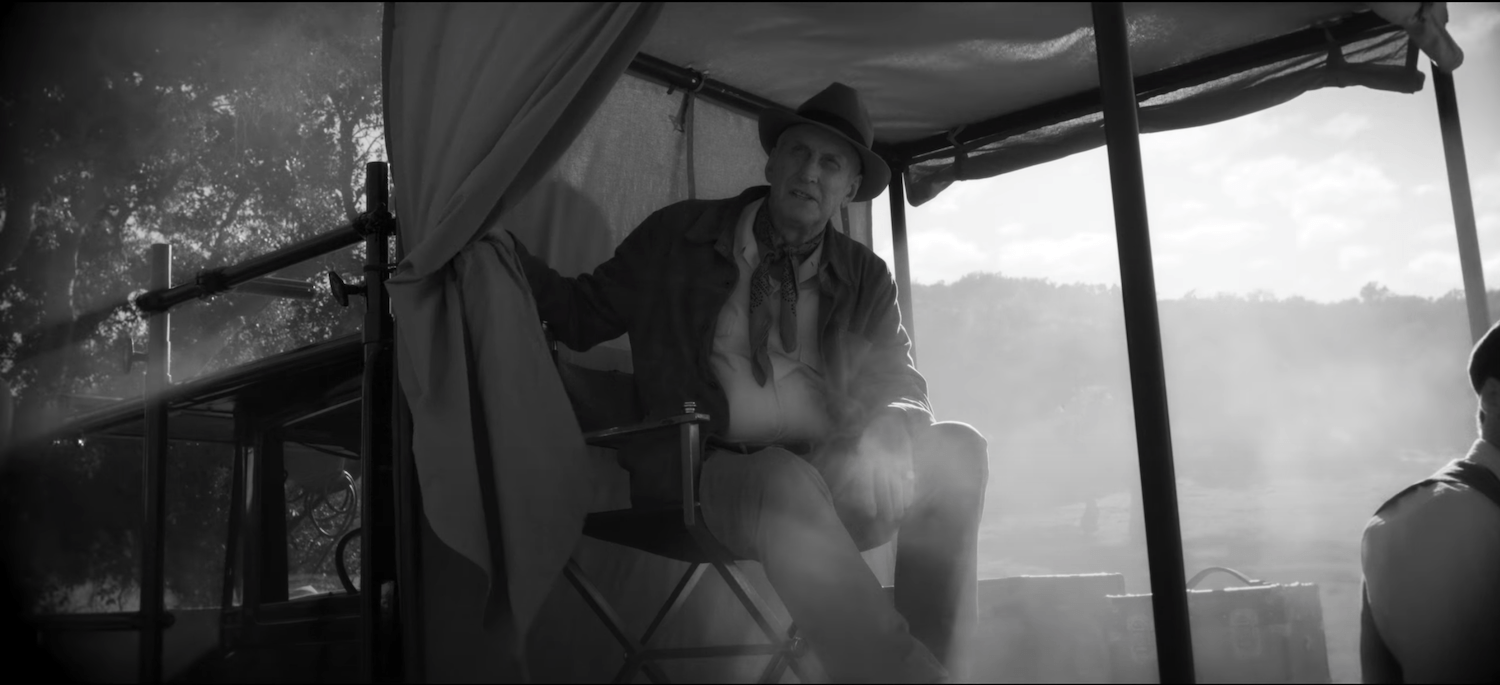

Da 5 Bloods

directed by Spike Lee; co-written by Lee, Danny Bilson,

Paul De Meo, and Kevin Willmott

https://youtu.be/D5RDTPfsLAI

Here's what I wrote after seeing Da 5 Bloods.

12.

Miss Juneteenth

written and directed by Channing Godfrey Peoples

https://youtu.be/Vb3oREG_DdA

I need time to write about this one. Sure, there is plenty of formula in its structure, and yes, some of the characters are little more than "types." But the central character is impressively complex, and Beharie's performance is sensational. Even as it moves toward a somewhat predictable conclusion, I see remarkable restraint here — director Channing Godfrey Peoples refuses to indulge several big moments that would have been crowdpleasers.

And this may be the best-looking movie I've seen in 2020, as well as the one with the strongest sense of place.

What a surprise, that this transcends its familiar beats to invite us into an experience that feels human and truthful.

11.

Never Rarely Sometimes Always

written and directed by Eliza Hittman

https://youtu.be/hjw_QTKr2rc

Thought #1:

I just accompanied 18 of my students through a reading of Sara Zarr's novel How to Save a Life. And while this movie had me thinking about Bresson and Mungiu and the Dardennes, it had me thinking far more about Zarr, and just how extraordinary it would be to watch this film and read that novel over the course of a class. They would complement each other in incredible ways — in storytelling, in subject matter, and even more so in a fascinating consideration of differing methods of character development.

Thought #2:

"…And when Jesus comes along saying that the greatest command of all is to love God and to love our neighbor, he too is asking us to pay attention. If we are to love God, we must first stop, look, and listen for him in what is happening around us and inside us. If we are to love our neighbors, before doing anything else we must see our neighbors. With our imagination as well as our eyes, that is to say like artists, we must see not just their faces but the life behind and within their faces. Here it is love that is the frame we see them in."

– Frederick Buechner, Whistling in the Dark

Thought #3:

It pains me to say that the people in my life I most wish would watch this movie and discuss it with me would refuse. To them, the subject matter alone would disqualify it as a movie worthy of their attention. And in doing so, they shut and lock their hearts against the suffering — and they do so under the pretense of "caring."

When you care for only one part of your body, the whole body dies.

When you care for only one soul in any given scenario, the body of that community dies.

God is love. So love is God. And the way to love God is to love love. And the way to love love is to show love to your neighbor and to yourself as if they were one and the same thing. Because they are.

Thought #4:

Critics I've heard raving about this movie mostly focus on an intimate conversation between Autumn (Sidney Flanagan) and a counselor. Rightfully so — it's a powerful scene. But the moment I'll remember above all... well, let's just call it "The Kiss." It's one of the most surprising, specific, and moving moments of human touch I've ever seen on film.

Thought #5:

I love Sharon Van Etten. I could just play and replay the closing credits of this thing.

10.

Small Axe: Mangrove

directed by Steve McQueen; co-written by McQueen and Alastair Siddons

https://youtu.be/gQBuNeFlS7c

I've seen both The Trial of the Chicago 7 and Mangrove, and I'd argue one feels like a screenplay reading by actors in costume; the other leans into the art form of cinema: compelling dialogue but also visual poetry, artful light, and silences that invite reflection.

Both are worth seeing. One is capital-F Filmmaking.

I compare these two only because they're both "prestige pictures" about the challenges that burden those who protest and demonstrate for the cause of justice and civil rights against systemic oppression, and because both are primarily courtroom dramas.

Chicago 7 made me think of Sorkin all the way through.

Mangrove made me believe.

I've had mixed feelings about earlier McQueen films, but if the rest of his five-part Small Axe series (opening week by week on Amazon Prime) is as good as this, it strikes me as a major statement — to release such an enormous work in the span of several weeks.

9.

Portrait of a Lady on Fire

written and directed by Céline Sciamma

https://youtu.be/R-fQPTwma9o

So enchanting that at times I fought against the need to blink...

...and I'm just talking about the moments Valeria Golino was on the screen. I hadn't realized what an indelible impression she'd made in my late-80s moviegoing until I saw her here and immediately remembered her name.

That was worth the price of admission. And it was just one of the smaller joys of this exquisite film, which cultivates as powerful an intimacy in its glances as it does in its dialogue. There were some edits here that took my breath away. I'm trying to think of a True Love in cinema more persuasively compelling than this one. John Smith and Rebecca of The New World come to mind. Perhaps the enigmatic intimacy of Certified Copy. Others?

(Whatever it is, this film is the anti-Blue is the Warmest Color — it's as respectful as that film is lurid. Sciamma's camera loves her characters, making even more painfully obvious how Kechiche was exploiting his own actresses.)

Yes, Héloïse's last line is entirely predictable once she's been set up for it, but that doesn't make it any less devastating. And has there ever been a stronger and more swoon-worthy promise in the first hour of a romance than the moment when Marianne, rather than drawing the cover off of the harpsichord, reaches up under it and begins to play?

I won't spoil the ending. Suffice it to say that Krzysztof Kieslowski would have loved this movie's closing shot. In fact, the closing shots of all three of the Three Colors films may have inspired it.

8.

First Cow

directed by Kelly Reichardt;

written by Reichardt and Jonathan Raymond

https://youtu.be/SRUWVT87mt8

1.

Dreamers

They never learn

They never learn

Beyond, beyond the point

Of no return

Of no return

And it's too late

The damage is done

The damage is done

– Radiohead, "Daydreaming"

2.

For several years, I attended backyard gatherings in New Mexico with my in-laws for a celebratory feast of something called "oily boilies." They were served savory and they were served sweet with cinnamon and sugar. I watched the whole process, amazed by how simple it was, and how scrumptious the results. They were even better for the generosity of the family that served them to us expecting nothing in return. Good people, good conversation, and a bellyful of happiness. Those gatherings are a thing of the past now. But I dream about those oily boilies.

And now... there's a movie about them, viciously calculated to taunt me.

3.

My compliments to the casting department. What a strange assembly, every actor an inspired choice — particularly Toby Jones.

4.

If I were to host a film seminar on the subject of capitalism, this might well be the opening night feature.

7.

Emma.

directed by Autumn de Wilde;

written by Eleanor Catton, based on the book by Jane Austen

https://youtu.be/qsOwj0PR5Sk

“Mother, you MUST sample the tart.”

“I advise against the custard.”

That these lines are delivered by the inimitable Miranda Hart and the magnificent Bill Nighy, well... really, what more do you need to know about Autumn de Wilde's new adaptation of Emma?

Also, proceed with caution: The MPAA needs a new warning about Anya Taylor-Joy’s eyes — they rule whatever they survey. Set a meeting for her with Whit Stillman immediately.

Were this movie to emerge from an oven on The Great British Baking Show, Paul Hollywood would shake somebody’s hand and never let go. It’s a dessert-week "showstopper" with so many technicolor layers of sugar work that you'll feel guilty just looking at it. Go for the frosting. You know you can trust Austen’s cake — it's substantial so long as it's respected, and it's respected well-enough here.

You'll hear a lot about Taylor-Joy, and deservedly so. She's strong except in scenes where she's asked to break down (she's good at Big Eyes Welling With Tears, but not at serious crying).

But don't overlook Mia Goth, who plays a difficult role here. Harriet can so easily disappear in any scene she shares with Emma, but Goth is key to why the movie works at all. We don't want to see her get hurt.

The week I saw this for the first time was a strange one: I saw Next-Big-British-Star Angus Imrie steal every scene in The Kid Who Would Be King — and then he showed up here in the opening scene! (And they give him no lines? Weird.) I had seen Anya Taylor-Joy in Glass two nights earlier as well — aaaaand here she is. But wait, there's more: I'd seen Johnny Flynn — and heard him singing — on an episode of Detectorists as well... and he's here, acting and singing!

The second time around, this was a date-night choice. And, big surprise! It was such a sumptuously colorful, extravagantly decorated film on the big screen, I anticipated it would seem like a lesser thing on a smaller screen and that its weaknesses would be more pronounced. But no, I enjoyed it even more. I suspect it's because de Wilde has such an outstanding cast, all of whom are excellent subjects in close-up, Taylor-Joy, Flynn, Goth, Nighy all have so many memorable moments of comic subtlety.

Between his singing here and his fantastic theme-song for TV's Detectorists — one of my all-time favorite series — I think I'm becoming a Johnny Flynn fan.

And speaking of music — this score by Isobel Waller-Bridge (Phoebe's big sister! I hadn't realized)! I am going to be playing it for years to come. I have baggage with the song "How Firm a Foundation." I grew up singing it in churches that, over time, made evident that the foundation being praised in the song — "God's word" — was not really their foundation at all. What they celebrated on Sunday morning they turned and attacked in their world-condemning, neighbor-hating politics during the week. But it is such a surprise here, and I like how it frames Emma's slow journey toward repentance and grace in terms of finding "refuge" in Jesus.

Anne, who has read the book many times, said the film didn't feel like the Emma she knows and loves... but she loved the movie anyway.

6.

Wolfwalkers

directed by Tomm Moore and Ross Stewart;

written by Will Collins (screenplay) and Tomm Moore and Ross Stewart (story)

https://youtu.be/d_Z_tybgPgg

"You never really understand a [wolf] until you consider things from [her] point of view ... until you climb into [her] skin and walk around in it.”

This is not a quotation from The Silence of the Lambs (although it could be). It's from To Kill a Mockingbird (of course). But it can meaningfully capture the conviction at the heart of the storytellers who bring us Wolfwalkers, a film about how humankind should (and shouldn't) treat other creatures... and, ultimately, a film about how we should (and shouldn't) treat one another. In fact, just look at the image representing the film (at least at the moment of this writing) and you'll see a suggestion of it there — a hand (the viewer's?) placed within the idea of a wolf's paw. What is possible when we set aside our fears of the Other and imaginatively inhabit their experience of the world?

It's the kind of idea that just might save the world.

So — Wolfwalkers. The film just played at the virtual Toronto International Film Festival, which enabled me the privilege of signing in and seeing it before its official U.S. release. What a thrill!

My impressions? Here they are:

You take the basic recipe of the studio's groundbreaking, masterful debut — The Secret of Kells, a film by Tomm Moore and Nora Twomey — and you build on that: A child growing up in a Fear Culture, one governed by a False Christianity, is forbidden to go outside the walls into the dangerous woods. And so, of course, the child goes. And, with the help of a spirit animal sidekick (a merlin this time), the child is surrounded by symmetrical bands of wolves, teeth-gnashing, and then encounters a magical forest girl who is also missing a parent.

I'll be honest: At this point in the movie, the similarities were unnervingly strong.

But then the story starts moving in some surprising new directions that bring to mind the shapeshifting motifs and the missing-parent sadness of Moore's Song of the Sea and the female friendship at the heart of Twomey's The Breadwinner.

Big surprise: Clear connections to one of my favorite '80s fantasy films — Ladyhawke — including one early shot and musical flourish that feel like a respectful tribute. Ladyhawke fans, you can't miss it!

Perhaps I'm making it sound like this is uninspired and derivative. If so, forgive me. It's clear that Tomm Moore and Ross Stewart have a kind of story they like to tell. But their powers are growing, and they're exploring their familiar thematic territory with bigger, bolder strokes. Wolfwalkers is a demonstration of increasing confidence and strength in every aspect of the studio’s artistry. While this film doesn't move me as deeply as The Secret of Kells — I like wolves, but I love the four gospels at the heart of The Book of Kells more than anything in the world — I am in awe of the artistry on display here, and the story is thrillingly compelling.

If I'm to point out any particular lack in this film, my first impulse it to suggest that it's missing some of the madcap humor that snapped, crackled and popped throughout Kells.

But I appreciate this narrative's focus on celebrating women as powerful and creative, worthy of so much more than being sentenced to the confinements and routines of "scullery maids." (Isn't that the primary idea at the heart of so many fairy tales?) I love the emphasis on recovering a more meaningful relationship with nature. And I respond more passionately all the time to depictions of the satanic forces that are unleashed when True Christianity is distorted by fear, arrogance, cruelty, and hatred — all of which contradict the fundamentals of the Gospel — into the very abominations that Christ preached against.

So this is beautiful and meaningful stuff — even if it is a bit familiar for this Secret of Kells super-fan.

And it's my favorite film of the year so far.

I'm tempted to watch it again before my TIFF link expires, but I want to wait. I want to let this first experience settle. And then, hopefully, I'll get to see it a second time in the proper context: a movie theatre, on a very, very big screen. The work deserves it.

Thank you, Tomm Moore and Ross Stewart, for investing so much art, heart, and soul in your work. You, like Miyazaki, Brad Bird, and so few animators before you, are reinforcing the standard by which all animated features are measured.

Here's my recorded review of Wolfwalkers, including a conversation with Dr. Lindsay Marshall about the movie.

5.

Shirley

directed by Josephine Decker; written by Sarah Gubbins

https://youtu.be/wxMtEean_V8

Here's what I wrote after seeing Shirley for the first time.

4.

Bloody Nose Empty Pockets

directed by Bill Ross IV and Turner Ross

https://youtu.be/uEvilRp8we4

Bear with me for a moment: It's difficult to put this into words.

I increasingly believe that the gift of art is that it teaches us to discover meaning within a frame by inviting us to observe the relationships between elements within a frame. In doing so, it trains our minds to then go and do that same kind of work observing elements with the frame of our experience, and to show us just how much our own commitment to (or abandonment of) love can influence the meaning of any given scenario (because that is meaning's determining factor in any work of art).

In other words, art is, for the audience, practice. It is a rehearsal for how to make the most of our attention when we consider the scenarios of our own lives. It saves us from "the unexamined life."

And Bloody Nose, Empty Pockets is one of those rare films that accomplishes the trick of looking exactly like an everyday, real-life scenario while also being so resonant with poetic artistry that it makes me want to look around at what is happening all around me with renewed intensity and curiosity. That's about as profound an effect as I can ask of any movie. (This is also true, for what it's worth, of Nomadland.)

This is a film that steers clear of most moviegoing styles in how closely and meticulously it imitates "the real world." It can easily be mistaken for a documentary — and much of what we see is, in fact, a documenting of actual people in actual incidental situations. But it has been crafted — in editing and, yes, with some directorial prompting (with a very light touch, it seems) — to become, or better to reveal poetry. The Ross brothers' subtlety makes it possible for us to perceive meaningful narratives and meaningful images that cohere into something greater than the sum of its parts.

Watching the celebrations and the grieving of the regulars in the waning hours of this Las Vegas tavern's closing night, it is easy to imagine — and I did, frequently — the angels of Wings of Desire drifting through this space and beaming with affection for these distinctively wonderful souls. And yet, the films that came to mind most often were Sean Baker's Tangerine and The Florida Project — both astoundingly true to life, both so rich with poetry.

We're given no exposition — we're dropped into it and left to fend for ourselves, learning the personalities and watching them careen and collide like billiard balls after a strike. Is this just chaos that could mean anything? I don't think so. As we begin to trace character arcs, discern backstories, and notice the suggestiveness of the songs being played and the seemingly random movies on TV (The Misfits, Battleship Potemkin), we can begin to see an elegiac tapestry woven with love for those on the edges and outskirts, the ruined and the lonely, the orphans who have found a family of sorts.

I'm grateful to Matt Zoller Seitz for writing the review that bumped this to the top of my Last-Minute 2020 Priority list. It's the last film I'm watching in 2020, and it will land near the top of my favorites list for the year. Thanks, Matt, for pointing me toward a fantastic grand finale for this punishing, heartbreaking year. This feels like the right way to wrap it all up.

What more could you ask for in a New Year's Eve movie than a vision of "a place to go when nobody else don't want your ass"? I won't ever sing the Cheers theme song the same way again.

3.

Small Axe: Lovers Rock

directed by Steve McQueen; written by McQueen and Courttia Newland

https://youtu.be/FVOhXowWqDU

Yes. Yes, they do.

More movies like this, please.

The second film in the Small Axe series — Steve McQueen's five-film examination of Black experiences in England in the 1970s — is the crowning achievement of the series. It's a celebration of the communal joys and laments of reggae-fueled house parties, where Black people could gather safely, without police raids, and find solace and self-confidence in numbers — dancing away their laments, dancing for unity, dancing for joy.