Meeting Andrei Tarkovsky (2010)

This review was originally published in two posts at Good Letters, the Image blog, here:

•

PART ONE

Have you ever become such an admirer of somebody that you made a fool of yourself over it?

I’ve been a raving psycho-fan at times. It began with life-sized “standees” of a particular pop star in my bedroom. Later, I snuck through a concert hall’s back door while a rock star did a sound-check. Years later, meeting Sam Phillips, I think I glimpsed a tremor of fear in her eyes as I raved about what her music has meant to me.

A few years ago, I saw how much worse it can get. A reader of my reviews started “ambushing” me in various locations. He’d spy on me, find out my favorite haunts, then wait for me there. Once during a downpour, he literally jumped out of the bushes; he’d been hiding there and hoping I’d pass by just so he could talk at me. When he started intruding at my office and annoying coworkers, I took strong measures to end it.

I’m glad I never reached that level of psychosis. I’ve learned a lot about restraint and courtesy by working as a journalist and interviewer. But sometimes I still want to know: What is the best way to be an admirer? How can a fan connect with his hero without embarrassing himself?

Let me congratulate Dmitry Trakovsky. Here’s a role model for how to be a super-fan.

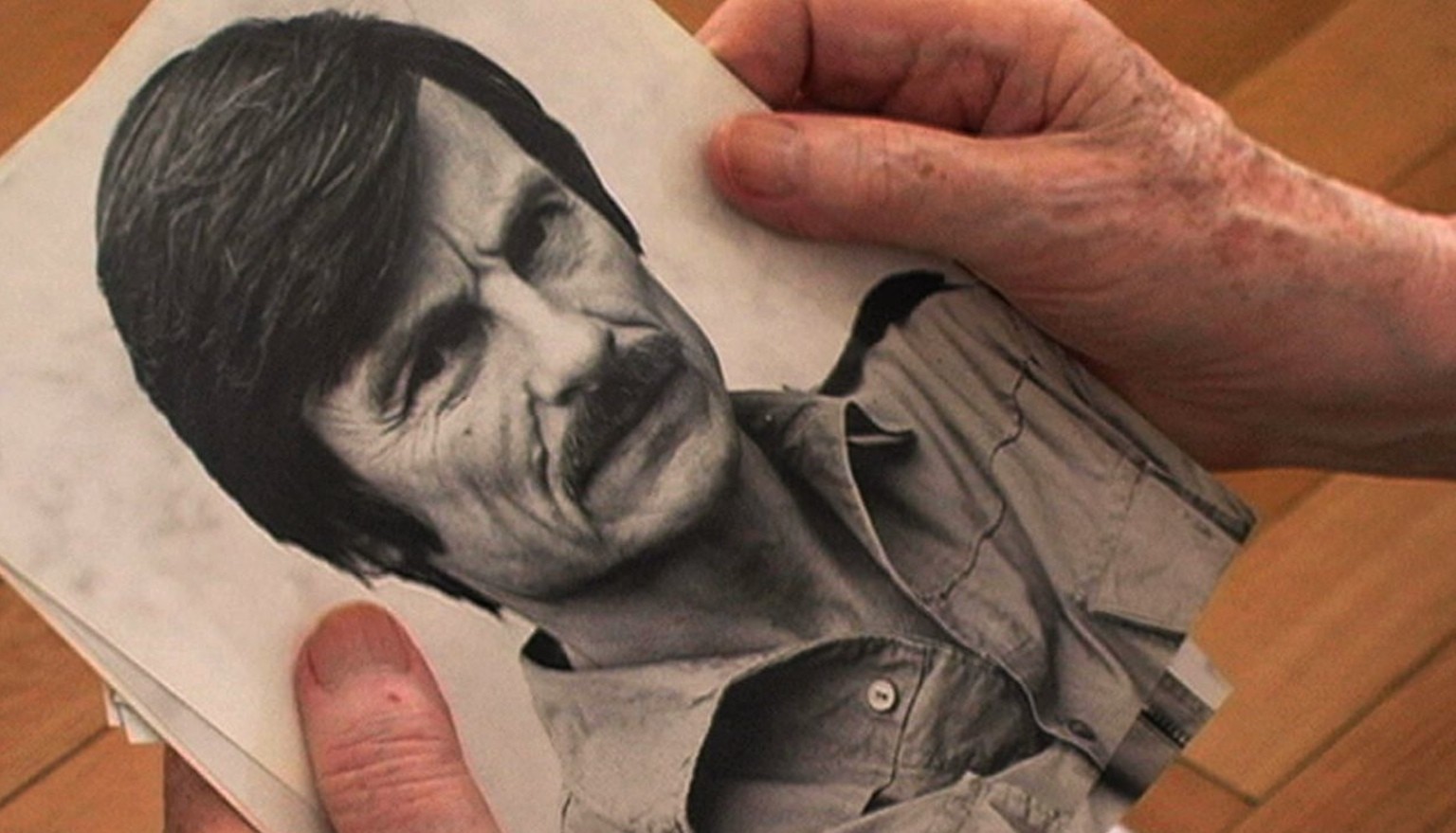

Dmitry has a favorite filmmaker: the world-renowned and revered filmmaker Andrei Tarkovsky. And he had given his admiration a shape. At twenty-three years old, he made a documentary celebrating his hero. He’s currently presenting it at various festivals, special screenings, and Tarkovsky retrospectives around the world, and he’s taking orders for the DVD.

His film Meeting Andrei Tarkovsky—yes, a young man named Trakovsky has filmed a tribute to Tarkovsky—is more than a fan letter. What could have been a self-serving attempt to publicly connect himself with a great artist has become instead an artful and admirable work of “stalking.”

Now, don’t get me wrong: Andrei Tarkovsky died in 1986. So “stalking” the man who madeStalker, Solaris, Andrei Rublev, and The Sacrifice is tricky.

Dmitry does it by collecting the testimonies of Tarkovsky scholars, filmmakers who were influenced by his work, and some of his former collaborators and actors. He even interviews the famous director’s son.

Some may find Dmitry’s own presence in the film distracting—he frames the whole project as his own quest for deeper understanding—but I found it an effective decision. He’s inviting us on a journey with him, restraining himself to the role of a humble observer and student. He leaves the speeches, insights, and epiphanies to the experts. And they paint vivid, memorable pictures of the great Russian filmmaker.

But Dmitry goes beyond testimonies from “talking-heads.” He makes an admirable beginner’s attempt to practice the very filmmaking tactics that made the man he admires a great artist.

He says in an Artist’s Statement on his website, “As I shot...I would seek to capture the unique flow of time within my subject, instead of simply recording something for its representational significance alone. In this regard, luckily, I was assisted by each of my fifteen interviewees, all of whom spoke of Tarkovsky with unfeigned depth, sincerity, and emotion. Consequently, there are no talking heads in this movie, and meaning may just as often be found in between words as through them.”

Personally, I think he’s overstating it. There are a lot of “talking heads” in this movie. But the way Dmitry treats them makes this a fresh, compelling documentary. He is patient, using long takes, and letting his interviewees offer substantial testimonies. Further, he captures wonderful silences, interruptions, and environmental details. This allows viewers to make intuitive connections on their own, enriching the experience with more than mere information.

(He also captures one unbelievable moment of coincidence that may be the funniest accident I’ve ever seen in a documentary.)

It’s a very personal journey for Dmitry. He and his family emigrated from Russia to the U.S. in 1987, the year after Tarkovsky’s death to cancer. Dmitry first “fell in love” with the works of the great Russian filmmaker while he was studying medicine and Buddhism in college. So he set out to visit the important places in Tarkovsky’s life, hoping to understand better why he is so drawn to the master’s mysterious artistry, and to get a sense of what his legacy means in the world today.

He didn’t know how to start. “I wasn’t a filmmaker yet,” he confesses.

But when he traveled with his father to visit a monastery in Northern California, he began ruminating on how to approach a filmic tribute to Tarkovsky.

While he was discussing his idea with the abbot of the monastery, he made a startling discovery. “At that moment...there was another monk sitting in the corner of the room and reading some Byzantine text and eavesdropping. He raised his hand timidly and asked for permission to speak.... The abbot granted him permission. He said ‘Actually I became a monk because of Tarkovsky.’”

That led to the first of many revealing, astonishing conversations that now make up the chapters of the film Meeting Andrei Tarkovsky. Just as Dmitry was readying to head out in search of Tarkovsky’s ghost, it seems Tarkovsky’s ghost leapt out of the bushes to surprise him, and accompany him on his journey.

Who was stalking whom?

[In Part Two of this review, I’ll share some of the highlights of Dmitry’s search for Andrei Tarkovsky.]

•

PART TWO

As he filmed Meeting Andrei Tarkovsky, the documentarian achieved his goal—he gained a better understanding of his famous, enigmatic Russian subject.

But Dmitry Trakovsky walked away from the project with something even more important. And so will those who seek out his film.

What a daunting idea it must have been.

Few filmmakers challenge audiences more than Andrei Tarkovsky. His seven films often seem impenetrable on a first viewing. Nevertheless, this Soviet filmmaker has made an impression on the international film world comparable to that of Bresson, Dreyer, and Ozu. Quoting the great Ingmar Bergman, one interviewee says that Tarkovsky “moved freely in rooms where Bergman could open a door a little and look in.”

His interviews were similarly challenging. He was prone to saying things like “Death doesn’t exist.”

Those particular words haunt Dmitry.

“Was he speaking metaphorically, in the sense that we live on through our works, or in the memory of others?” he asks. “Or did the transcendence of death mean something more concrete to him?”

This sets up his mission statement: “I wish to come closer to Tarkovsky’s seemingly impenetrable words by considering his own life after death. But who knows where I will stumble upon him? In a thought? An object? An empty field? I’m beginning to search for Tarkovsky, not in the past, but in all that he has left behind.”

For some of his interviewees, Tarkovsky lives on in the radical nature of his poetic filmmaking techniques. He worked by assembling raw footage and then eliminating superfluous material, believing that the film itself would make the decisions, telling him which edits to make, revealing its own meaning. “Death underscores the meaningful in a person’s life,” says professor and linguist Vyacheslav Ivanov, paraphrasing both Tarkovsky and Pasolini, “and in film one must know how to do the same using cinematic means.”

Russian director Ilya Khrzhanovsky seems almost frustrated with Tarkovsky’s influence. He notes that any filmmaker who captures an authentic picture of Russia’s reality is accused of copying Tarkovsky.

In Venice, Professor Fabrizio Borin speaks of how the films express Tarkovsky’s fierce convictions. According to Borin, Tarkovsky believed that human society is diseased because it has “pointed to the centrality of man instead of towards the consideration that man is one of many elements that belong to a plurality of subjects in the universe.”

In other words, we need to get over ourselves, and catch a greater vision.

This wasn’t just Tarkovsky’s subject; it was his way of working. Michal Leszczylowski, editor of Tarkovsky’s The Sacrifice, remembers Tarkovsky saying, “You have to be the servant of a work of art, and not the master.”

Leszczylowski’s just one of many who have personal anecdotes to share. Tarkovsky is clearly alive and well in their memories.

Tarkovsky’s son, Andrei Andreevich Tarkovsky, recounts his family’s history. Others speak of him as if he never left. “I still feel his presence,” says Donatella Baglivo, who filmed a unique documentary on Tarkovsky in the ‘80s.

Dmitry also visits Angelo Perla, director of the Italian art gallery in which Tarkovsky filmed a painting called “Madonna del Parto”—apparently the only known fresco of a pregnant Madonna—for his film Nostalghia. Perla doesn’t just remember Tarkovsky’s visit; he reveres the man, and boasts of playing him in a local theater production.

But Meeting Andrei Tarkovsky is more than just a study of the man and his methods. It’s an encounter with something more: the mysteries that Tarkovsky invited his audience, peers, and collaborators to behold.

Filmmaker Manuele Cecconello speaks of how Tarkovsky’s images express “a yearning for the sacred.” And the younger Tarkovsky speaks of his father’s constant interest in “mysterious, enigmatic happenings.” (How many have noticed that December 28, the day that the famous filmmaker died, appeared prominently—like a prophecy—in one of his films?) Now the son is on his own quest for a “spiritual understanding of truth.”

“Each genius makes us sensitive to things which we haven’t noticed before,” says Polish film director Krzysztof Zanussi, one of Tarkovsky’s closest friends. He gives personal examples of ordinary moments that Tarkovsky’s films have helped him see with new eyes, like rain spilling from a tin roof. “[Tarkovsky] enriched us,” he says. “We owe him something.”

Gregory Pomerants, who Dmitry describes as “one of Russia’s most free-thinking intellectual and spiritual guides,” finds Tarkovsky’s work to be a launching pad into engagement with the deepest mysteries of the human spirit, taking us to “the inner-most layer...where our soul, like a bay, meets with the ocean of the divine.”

Having seen Meeting Andrei Tarkovsky twice, I’m certain I will revisit it often, because the testimonies enliven my appreciation for, and questions about, the gift of art.

Further, the film inspires me to return to Tarkovsky’s films which dare me to peer through strange doors into riveting mysteries.

In this, Dmitry models how we might best honor those “geniuses” who have blessed us with transforming visions of truth. Rather than fixating on the genius like a fanboy, he helps us see what it was the Tarkovsky sought to reveal.

I think Tarkovsky would have found this film a blessing. He would not have desired a monument of effusive praise. His friend Zanussi testifies that the filmmaker, on his deathbed, said, “Please remind people I want to be remembered as a sinner.” Astonished, Zanussi protested. But he concludes, “Andrei was always trying to become that better human being...and probably a better Christian, because he was deeply Christian.”

For those of us who have barely begun to interpret the mysteries Tarkovsky revealed, we needn’t be too eager to put words to what we’ve encountered. When Dmitry visits Domiziana Giordano, still gorgeous almost thirty years after she starred in Nostalghia, she pulls the original script off a bedroom shelf as if it were a holy relic and thumbs through it, laughing at how little she understands it.

And yet, she laments the apparent shallowness of projects she has done since then. Describing a talk show she had visited that morning, Giordano says, “They were talking about nothing. And I asked myself, ‘What the hell am I doing here?’” By contrast, her experience with Tarkovsky convinced her that they were “not just fooling around with people’s money and souls. We were working to make something great.”

Pray for Jafar Panahi

I told you about the plight of the great filmmaker Jafar Panahi here.

Well, the story has a new development.

Beware of Agora: Part 1 - "Outright Lies About Christians"

Get ready. The big screen's latest distortion of history by Christian-hating storytellers is on its way.

Mark Shea applauds Fr. Robert Barron's comments about Agora: Read more

Did that Isabelle Huppert guest-spot on Law and Order:SVU really happen?

I mean... really, Law and Order: SVU? Read more

Adaptation (2002)

[May 2010 Update: This review is eight years old. It's been off of the website for a while because it needed some slight revisions. My first encounter with the movie was very, very different from my second viewing. I've watched it several times since then and come to appreciate it much, much more. So here is an updated version of my original review of Adaptation.]

-

Here’s the pitch:

Jeffrey Overstreet is a film critic with an assignment to review the bizarre, relentlessly clever movie Adaptation, from director Spike Jonze and screenwriter Charlie Kaufman.

He’s excited about it. He’ll get to lavish praise on Nicolas Cage for the actor’s best performance in many years, and he’ll get to point out the cleverness of the Jonze/Kaufman team. Their last collaboration was Being John Malkovich, which challenged viewers to sort out a confusing jumble of perspectives and non-chronological sequences. Adaptation works in a similar way.

But Overstreet is filled with angst about reviewing the film for several reasons:Read more

Days of Heaven (1978)

[This brief review was written as a summary for the Arts and Faith Top 100 Films List.]

•

Days of Heaven, Terrence Malick’s 1978 story of adultery on the Texas Panhandle, is set just before World War 1, but it resounds with echoes of Old Testament drama.

In it, blast-furnace worker Bill (Richard Gere) gets in a fight with his foreman, ten goes on the run with his girlfriend Abby (Brooke Adams) and little sister Linda. They settle as field workers for a rich farmer (Sam Shephard), who eventually falls for the irresistibly beautiful Abby.

Bill sees this as an opportunity to get rich not-so-quick. And his plot is the first step toward violence, which blazes up in a conflagration that may be the greatest inferno ever filmed.

Captured indelibly by cinematographers Nestor Almendros and Haskell Wexler, Malick’s film has a visual syntax so eloquent and graceful — its fields of gold cause its quiet characters to stand out like mythic figures — it would play powerfully as a silent film. (Shots of a hand extended to brush across the wheat fields have inspired numerous imitators, including Gladiator’s Ridley Scott.)

But the poetic narration by young Linda is endearing, and it keeps the goings-on from becoming too ponderous.

After making this meditative masterpiece, Malick abandoned filmmaking for thirty years, only to return with greater ambition, and similarly spellbinding cinema. Recently, The Criterion Collection released a pristine, beautiful restoration of Days of Heaven on Blu-ray and DVD. That is now the best way to experience the film, especially if you can see it on a large screen.

Greydanus: "No Movies, Please. We're Catholic."

Steven Greydanus is on a roll. His latest entries at The National Catholic Register are worth your attention. Read more

Diary of a Country Priest (1951)

[An abridged version of this review was published as a summary for the Arts and Faith Top 100 Films List.]

•

“Ponderous”? Yes.

“Slow”? Indeed.

But Robert Bresson’s 1951 film Diary of a Country Priest is an undisputed classic. It was the third of thirteen films by Bresson who, according to Francois Truffaut, is to French movies what Mozart is to German music. And it may be the best entry point for appreciating his unique style.

If this were a "Christian movie," it would be the story of a cleric who moves into a troubled town and inspires everyone to cultivate compassion for one another through his courageous example. Persecuted villagers would be liberated. Doubters would find God. Bad guys would be exposed and locked up, or else they would crumble into confession. Some dark secret in the cleric's past would be exposed as a misunderstanding, and he would emerge triumphantly righteous, an example for us all.

Instead, this is a story that is relevant to the world we live in. Things begin messy, and they get worse. There are victories, but they are memorable because they are hard-won, faint glimmers of grace in a dark world.

A sensitive new priest (Claude Laydu) moves into a parish in Northern France so he can serve a small village called Ambricourt, only to discover he is less than welcome.

As the town’s dark secrets emerge, his attempts to provide insight or comfort fall on deaf ears, and the weight of the troubles threaten to crush him.

He doesn’t get along well with the older priest up the road, who shows little concern for how the villagers have hurt his feelings.

A local countess is in pieces over the death of her son. The countess’s husband is carrying on an extramarital affair with their daughter’s governess. And their daughter, a cynical and resentful adolescent named Séraphita (Martine Lemaire), is becoming quite a monster.

Exhausted by stomach trouble, the priest relies on what little nourishment he can draw from a strict diet of hard bread and wine. His “godless” doctor does little to lift his spirits.

Thus, the priest's plight inspires our sympathies, even though he lacks any kind of charm.

A master class in visual composition and sound design, Diary has influenced filmmakers for generations by proving the gravity of telling cinematic stories without many of the common enhancements we’ve been conditioned to expect. Its rare glimpses of the French countryside are stark and striking, suggesting that any man who would truly pursue holiness will walk hard roads through desolate lands.

Three Colors: Blue, White, and Red (1993)

This brief review was written as a summary for the Arts and Faith Top 100 Films List.

•

The great and final act of Krzysztof Kieslowski’s remarkable career was the production of a trilogy called Three Colors — Blue, White, and Red — that represents the colors of the French flag, and the values they represent: liberty, equality and fraternity.

This symphonic, poetic trilogy intrigued me in my first encounter with its opening chapter, Blue. Then it began to haunt me, and I returned to see that film four times in the theater. As I began learning to translate Kieslowski's unconventional, intuitive form of storytelling, I fell in love with his images, with the performances he drew from his actors, and with the work of his musical partner, Zbignew Priesner. Since then, Three Colors has become my favorite cinematic achievement. I return to it again and again, blessed by its visual beauty, its musical invention, its astonishing performances (especially Juliet Binoche in Blue), and its inspired spiritual exploration.

Filmed in three countries (France, Poland, Switzerland), their plots overlap only slightly. Watch closely, and you’ll see the different main characters pass each other and remain strangers.

Blue, empowered by what may be Juliette Binoche’s greatest performance, is the first: In it, the grieving widow of an internationally renowned composer must decide whether to assist in the completion of her husband’s unfinished work — a symphony about the hope of Europe's reunification. As she tries to begin a new life and escape the pain of memory and loss, she becomes entangled in the lives of her husband’s assistant Olivier, a prostitute named Lucille, and a beautiful stranger named Sandrine who keeps a scandalous secret. Blue is an intimate observance of grief, betrayal, struggle, forgiveness, and courage — all written on a woman's face, in a film full of deep silences and sudden visitations of music. But it is also a poem about hope for the redemption of the world.

White is a dark but whimsical comedy about Karol (Zbigniew Zamachowski), a Polish hairdresser whose wife (Julie Delpy) humiliates him and abandons him. Furious and vengeful, he makes a devil’s bargain with a depressed stranger named Mikolaj, finds his way into wealth, and then stages a disappearing act that will help him carry out a wicked plot. Even as the film focuses on Karol’s misery, his unexpected failures, and his attempt to “dominate” Dominique, it’s also about Poland’s uncertain future and how cultural transformation may bring in a whole new wave of problems.

Red, the last chapter, follows a young fashion model named Valentin (Irene Jacob) who catches a retired judge (Jean-Louis Trintignant) in an act of voyeurism. Frustrated by the legal system’s inability to uncover the truth of a matter, the old man sits at home and uses sophisticated surveillance to listen in on the “truth” of his neighbors’ private telephone conversations with some sophisticated surveillance. While the judge has given up on law, Valentine’s legalism makes her judgmental and condemning. Slowly they explore a middle ground — fraternity — until the film brings all three of the trilogy’s episodes together in an unexpected and dramatic finale.

While the films explore themes of liberty, equality and fraternity, don't let those limit your experience or narrow your interpretation. They do not begin to summarize the wisdom that these films convey — many other themes, questions, and insights suggest themselves to us through the course of the stories.

But the three themes indicated can prove helpful as starting points for those who want to engage with and discuss the trilogy. And they are best phrased as questions: In Blue, what happens when Julie pursues personal "liberty" from her past and her pain? What would true, life-giving liberty look like? Or in White, what kind of "equality" is Karol seeking? These themes are suggested like lenses that will reveal different paths into understanding the riches of these stories.

Playtime (1967)

A review written as a summary for the Arts and Faith Top 100 Films List.

-

The great French comedy director Jacques Tati starred in four of his own films, playing one of cinema’s most beloved comic figures, Monsieur Hulot.Read more