A Quiet Place Part II (2021)

The most highly anticipated sequel of the summer of 2021 so far is called A Quiet Place Part II, but it seems familiar enough in some ways that I'm inclined to nickname it 474 Days Later. We have, after all, seen actor Cillian Murphy navigate similar genre territory before, playing one of the few survivors of an abrupt and global apocalypse, in 28 Days Later — one of the greatest zombie films ever made. I couldn't help but think of veteran director Danny Boyle's thrilling and thought-provoking film about the undead when up-and-coming director Jon Krasinski focuses his characters' attention, during this alien invasion flick, not on the aliens themselves but on the monsters that global troubles have "turned other people into."

Ultimately, though, it isn't Boyle who comes to mind most often in this relentlessly familiar entertainment. A Quiet Place Part II plays, above all, like a mash-up of suspenseful scenes from James Cameron's 1986 sequel Aliens, Steven Spielberg's 1993's Jurassic Park, M. Night Shyamalan's 2002 sci-fi jumpfest Signs, and Spielberg's 2005 re-imagining of War of the Worlds. In fact, I'd call this the most overtly Spielberg-ian exercise to hit the big screen since Super 8.

Is that a bad thing? No, not really, because Krasinksi proves he's learned a lot from the master of adventure and suspense. His big scenes are imitations, but they work like a charm. And, during one of my first post-lockdown visits to a big screen, I was delighted by waves of nostalgia. Except for the fact that it lacks much of anything that feels inspired or new, this is how summertime moviegoing used to feel.

The Abbott family, unfortunately, aren't having any fun at all. Evelyn (Emily Blunt) is still leading what remains of her family on tiptoe through a world of noise-activated human-smashers from outer space. She's lost one of her sons. (No spoilers there — it happened early in the first film.) She's lost her husband Lee (Jon Krasinski) — although we get to see plenty of his heroics in the film's opening flashback scene (which is spectacular) to the day that the aliens began their planet-wide slaughter of humankind.

(By the way, if my mention of Lee's death is a spoiler for you, forgive me, but this is a sequel, and there's no way to offer even a brief summary without revealing that fundamental plot point. Critics who write about The Empire Strikes Back should be able to talk about Obi-Wan Kenobi's ghost, right?)

There will be stumbles: one involving a bear trap, one involving a trip wire, and various other noise-making blunders. This will keep audiences on the edges of their seats.

But, more importantly, there will be some thoughtful ethical dilemmas that raise the question about what it means to "love your neighbor" in circumstances as dangerous as these. When they discover the possibility of more survivors in the region, they face decisions that wil divide them: Should they move in with Emmett (Murphy), an old friend who has been similarly traumatized by the loss of his family? Should they risk everything to follow a signal that might be sent deliberately as a beacon of hope to survivors?

Still, this falls far short of most Spielberg films in the depth of its storytelling because there just isn't anything particularly interesting happening beyond the moment-to-moment tiptoeing and trying not to scream. The more we see the aliens, the less interesting they become.

What's more, the most compelling actor in this ensemble is Emily Blunt, and she doesn't get to do much more than sneak around in various stages of panic, while the film promotes Regan to the prominent role, suggesting that this trilogy is, above all, her story. Fortunately, Simmonds is up for the challenge of a demanding role, even if the film's finale deprives her of any significant breakthroughs or discoveries. There's something vaguely dissatisfying about a film that's focused on survival when the audience doesn't take much more home than the relief that, yes, at least some of these characters have survived.

Let us praise, however, the work of cinematographer Polly Morgan, who makes everything look great. (Hooray! Another woman behind the camera making a strong impression in a male-dominant field!) Variations on Spieberg's Jurassic Park kitchen sequence and the War of the Worlds alien-in-the-old-house sequence look slick and effectively suspend disbelief.

But the movie has no storytelling twists to deliver any cleverer than the first film's "how we kill the monsters" gimmick — which struck me as too coincidentally convenient in the first (quiet) place — and it has even less on its heart. Don't think about it much or you'll fall screaming into plot holes. And don't hope for surprises: We can tell how it's going to end from the opening minutes. It's a predictable and familiar amusement park ride — a very well-built one.

For what it's worth, two hours after the end credits of A Quiet Place Part II ran out, I looked up from my afternoon session of grading student essays and thought, "When I'm done with this, I should go to a movie." And then I realized, "Oh. Wait. I've already been to one today." The experience had evaporated that quickly.

I'd argue Krasinski hasn't given us A John Krasinski Film yet, just as I'm inclined to argue that J.J. Abrams hasn't ever given us a distinctive J.J. Abrams Film. Given the evidence, I think they're both skillful impressionists. I'm not saying their movies can't be fun; I'm just saying I've never had that "I'm witnessing something visionary and new" feeling that I'm always hoping for when I engage in the liturgies of cinema. Sometimes, big movies do nothing more than go through the motions, providing us two engaging hours of escape from summertime heat. In this case, we've got a movie that gives us a momentary escape from our own all-too-familiar troubles by immersing us in the all-too-familiar — and far more entertaining — sufferings of others.

So, if you're eager to get back to big-screen moviegoing, enjoy A Quiet Place Part II! If you're cool staying home, make a wiser decision: revisit one of the more substantial films it imitates.

Follow-up Question:

Is it possible that some biggest moments in this series have been inspired by something from another genre altogether?

In the Heights (2021)

Full disclosure: I'm not a big fan of Hamilton. And I think it's important you know that before I dare to offer any thoughts on In the Heights.

Undoubtedly, the circumstances of my first Hamilton viewing — on my home television via Disney+, rather than in a theater watching a live performance — made a difference. Live theater in a packed house is one thing; watching carefully edited footage of a stage on a 32" screen in your living room while the phone rings and the cat wants to be fed... that's something else.

But could it also be that my expectations were too high? Perhaps. My first experience of Lin-Manuel Miranda's blockbuster Broadway show about the founding fathers took place more than a year after Hamilton hysteria peaked. It was impossible not hear the raves, the cheers, the famous quips ringing in my ears even while the Disney logo sparkled on the screen before the actors appeared onstage.

Whatever the case, I assure you that I was skeptical as I approached it. And, as the end credits rolled, I was conflicted about my experience.

That's not Lin-Manuel Miranda's fault; as a writer and composer, he achieved something undeniably extraordinary with that play, something of lasting cultural significance that has inspired artists and audiences around the world.

No, the problem here is largely personal: Broadway musicals have never really been my thing. Big, boisterous shows like those rarely enchant me. If I feel that a work of art is working hard on my emotions but not my intellect, I distrust it and I back away. And, in my experience, the artists at the controls of big Broadway-style theater productions — especially musicals — seem intent on astonishing an audience, entertaining them by giving them huge portions of things they already love, and thus overwhelming them and forcing them to surrender. If art appeals only to #TheFeels, it can leave an audience convinced, in their delirium, that they've experienced greatness when, in fact, they've just been overstimulated. What's more, it can too easily persuade the audience to embrace dangerous ideas.

When I did finally see the Disney+ document of the show's original run, I was impressed, to some degree, by the performances, the songs, and the relentless genius of the lyrical wordplay. Granted, there's a lot more food for thought in Hamilton than in most musicals. In the end, though, I was exhausted by the too-muchness of it all.

And that wasn't all: I was — as I explained in my original review (exclusive to Looking Closer supporters) — disillusioned by how Miranda's storytelling emphasized the importance of striving for and achieving greatness without really asking the audience to reckon sufficiently with the inevitable "collateral damage" that can come from such passion and single-mindedness. And, since my experience was to watch a "movie" of the play, I was hoping for a more cinematic experience, something through which imagery speaks. And, in this case, it doesn't.

So perhaps this explains why I've been skeptical of In the Heights since I first saw the trailer.

- A) It is, first and foremost, a big Broadway stage production.

- B) It has a reputation of being a big crowd-pleaser.

- C) It's obviously flamboyant and supercharged with energy, exploding with big emotions and expecting to evoke big emotions in its audience.

Lin-Manuel Miranda is clearly a once-in-a-generation genius when it comes to putting on an extravagant show that will make an audience cheer repeatedly. And it has seemed inevitable that In the Heights, a winner of multiple Tonys for its Broadway manifestation back in 2008, would become a big-screen sensation. But those three factors were like flashing neon signs: "This is not your kind of thing, Overstreet." I approached it with some reluctance, braced for another super-sized exhibition of showmanship of the sort that frazzles my nerves and leaves me snarking about "sound and fury that signifies... not much."

Well... surprise!

I love this movie. And I think you'll love it too.

I'm as stunned as any reader will be that I am wholeheartedly recommending In the Heights to moviegoers, and that I'm encouraging them to round up their friends and families and get out to a theater to experience it.

Don't just run to your nearest cinemas — go to the one with the biggest screen and the best sound system. I saw it in a Dolby Cinema presentation, and I was dazzled by the exquisitely textured, radiantly colorful, images; the contagious energy; and the spectacular sound design.

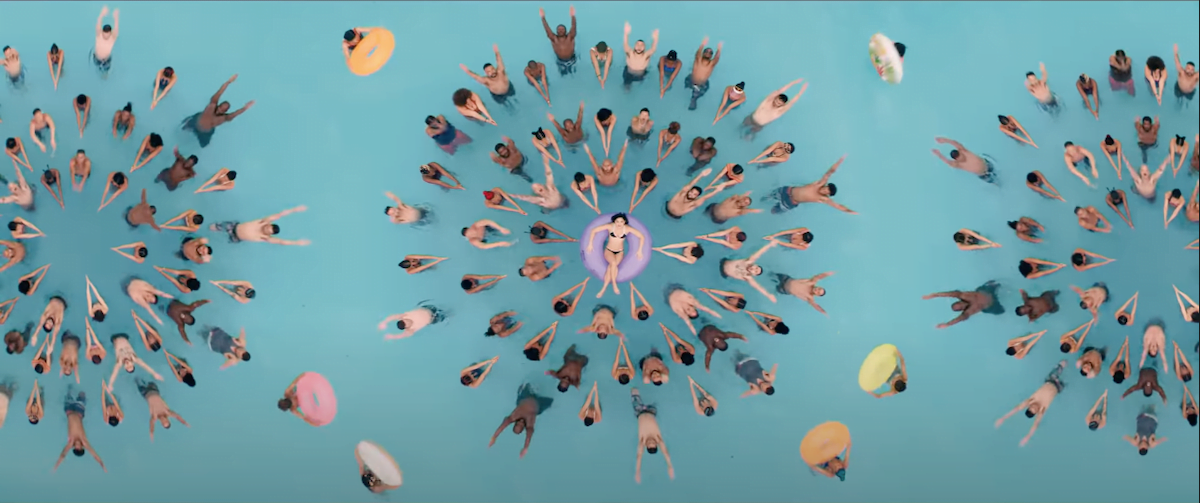

Let me be clear: I don't mean that I was forced to surrender by another case of too-muchness. I do think it might have been a better film if director Jon M. Chu (Crazy Rich Asians) and screenwriter Quiara Alegría Hudes, adapting Miranda's stage play, had trimmed ten minutes along the way. But no, when I say that the movie dazzled me, I mean that it served up distinctly cinematic pleasures: wonders that can only happen at the movies. This movie is full of thoughtful and, more importantly, meaningful imagery. Song by song, scene by scene, special effects by special effects, performance by performance, In the Heights won me over and made me care about the community in the spotlight. It's the most consistently inventive, cinematically satisfying big screen musical I've seen since Baz Luhrman's Moulin Rouge!

I'm comparing it to Moulin Rouge! for a good reason. What made that movie work as a movie musical was that it was conceived specifically for the screen. It was only bound by the limitations of cameras and animation. If you had told me that In the Heights was imagined first and foremost as a movie instead of a stage play, I might have believed you! This never feels like a stage show adapted for the screen; it’s a thrillingly imagined motion picture.

I’m inclined to say that if you haven’t seen it on the big screen … you haven’t really seen it.

Now, before you decide to make In the Heights your next date movie, a caution: If it's a compelling love story you're after, I suspect that neither of the central love stories in this web of Manhattan-focused narratives will scratch your itch, and the combination of the two central love stories only weakens both threads.

The arc of the romance between bodega-owner Usnavi (the charismatic Anthony Ramos) and salon-worker/fashion-designer Vanessa (Melissa Barrera, apparently auditioning to play Frida Kahlo) is strangely slight. The two suffer an awkwardness between them that seems to exist only to frustrate the audience until the most visually advantageous moment to silhouette a first kiss. (Don't tell me I'm spoiling things: All of this is evident in the trailers we've been watching for a year.)

In a scene that almost made me sprain my eyes for rolling them, Usnavi, on a date with Vanessa, pushes her into dancing with other charismatic suitor for... what reason again? I'm reminded of a Schitt's Creek episode in which David urges Patrick to date someone else just so he can have the reassurance that Patrick will come back to him.

Do real people suffer such ridiculous lapses in judgment? Do they do such things on first dates?

The love story about Stanford dropout Nina (Leslie Grace, who should be fined for exceeding all standards of cuteness) and taxi dispatcher Benny (Corey Hawkins, suave and charming) is even slighter:

Disillusioned and dehumanized by racism and loneliness, Nina has abandoned her pursuit of a college degree and return to Washington Heights, seemingly content to focus on "inhaling the sweet and unthreatening air" (as The New Yorker's Anthony Lane so aptly puts it). Benny is thrilled that she's back, and they quickly rekindle their interrupted romance. But Nina clashes with her father (Jimmy Smits) about her future and whether or not his investment in her is selfish or not. It all seems too easy, and if we could have felt the stakes of her decision more viscerally — that is, if we were convinced of Nina's rare intellectual promise which the whole neighborhood seems invested in — this story would take a stronger hold on us.

But this is not enough of a problem to spoil the fun. These individual love stories played for me as secondary; the larger, more compelling story is about a neighborhood in Manhattan called Washington Heights, primarily Latino, and under threat of dissolution. And despite the unstoppable tide of gentrification, they fight for their block and, even more, for their "chosen family" bonds, finding strength and purpose in the love that they show for one another. In celebrations of their diverse cultural foundations (Dominican, Puerto Rican, and more), they remind each other of dignity, strength, and the value of their wild and diverse imaginations.

I found myself far more interested in, and moved by, the film's supporting characters — particularly Abuela Claudia (Olga Merediz), the humble matriarch of the neighborhood, who bears the greatest burden of the past and the strongest belief in possibility; Sonny (the brilliant Gregory Diaz IV), a young and charismatic undocumented immigrant whose future in a Trumpist America seems unlikely; and Daniela (Daphne Rubin-Vega), a salon owner who refuses to let her community collapse under the weight of gentrification without a fight.

While the lovers' stories are drawn in bold strokes, simplistic and — to use a word my students seem to value above all else — relatable, like pop songs that instantly connect to a massive audience, it is in the quieter, more intimate, more specific exchanges with the secondary characters that the movie takes on greater depth and dimension, a richer sense of lived experience. One of the moments that will be remembered for its delicate truth-telling comes when Claudia shares some of her one-of-a-kind sewing, a pair of gloves once worn by Nina's mother. Claudia's needlework becomes a symbol of how people survive harsh circumstances through creativity and art. “We had to assert our dignity in small ways," Claudia says, "little details that tell the world we are not invisible.” That's what makes this musical special; if you zoom in, you find a tapestry of "small" moments that resonate with lived experience.

Miranda himself plays one of these characters that, while seemingly "small" in the grand scheme of things, become the secret to the movie's truthfulness. He pushes a piragua cart around the neighborhood, pouring vivid sugar syrup over shaved ice — small cups full of love and life. ("Think of him," writes Anthony Lane, "as a warm-weather descendant of Jack, the lamplighter whom Miranda played, with an idling charm, in Mary Poppins Returns (2018).")

The ice man's treats seem so trivial, but they come to seem essential (and appealing to us as moviegoers) in the midst of a heat wave that will have viewers fanning themselves, much the way they did in the furnace of Spike Lee's Do the Right Thing. The heat is an easy but effective metaphor for the relentless pressures — cultural, financial — on Washington Heights. Some critics are pointing to Lee's film in order to malign Miranda's musical as too sentimental and sweet. In The L.A. Times, Justin Chang observes, "[U]nlike Spike Lee’s much more trenchant evocation of a humid New York summer, the squeaky-clean In the Heights remains unblighted by bad vibes or bitter conflict...." But he seems to appreciate this movie's alternate take on trouble:

The problems its multigenerational Latino characters face are undeniably complicated and deeply entrenched: the pressures to advance and assimilate; rising gentrification and diminishing opportunities; the seemingly endless quest for a place that can honestly be called home. But those problems are notably confronted here without violence or rancor — a newly tacked-on scene at a DACA protest as politically barbed as it gets — and they are resolved, as much as they can be, with a winningly amiable spirit.

I think In the Heights would make a remarkable and revealing double-feature with Lee's 1989 classic, providing an expression of hopefulness that would serve to balance out the grim but truthful troubles that fracture Lee's New York in so many ways.

Perhaps the greatest strength of the film is the way in which Chu finds unique inspirations for almost every musical sequence, delivering one surprise after another:

- an opening stroll that moves more like a dance in a way that recalls Baby Driver;

- an emotional subway ride in which flashes of light and shadow trigger flashbacks;

- guys rigorously rapping as they swagger through town, their gestures enhanced with chalky animation;

- a tremendous swimming pool sequence involving a host of dancers and synchronized swimmers, set to a song about lottery-ticket dreams; and

- another intimate dance between two lovers near the end of the film that defies gravity in ways I won't spoil for you.

Every time I began to feel a hint of Sensation Fatigue, Chu would spring a new surprise that did more than jolt the audience; it seemed meaningful.

Alissa Wilkinson (Vox) describes Washington Heights as being more than just a context: "What cinema affords so readily to its storytellers is the ability to visually build a full, richly layered world in a way you really can’t do onstage. [Chu] leans into the possibilities. Now, Washington Heights is a character, not just a few buildings. Its residents are singing and dancing on the street corners, in the alleys, in living rooms, in salsa clubs. The film is an intoxicating capture of both a culture and a city." (You can read Wilkinson's interviews with Lin-Manuel Miranda, Quiara Alegría Hudes, and Jon M. Chu here.)

As an affirmation of — indeed, a defiant embrace of — Latino immigrants' histories of endurance, of hope, and of imaginative flourishing in the midst of hardship, it reminds us of what America can make possible for people from lands troubled by violence and poverty. (Man, this movie made me so jealous of people who have a cultural heritage they take pride in. As a white American who grew up in a primarily Republican community where I was subtly conditioned to accept system racism, I can’t imagine what that’s like.)

Ultimately, In the Heights plays for me as a celebration of America's as-yet-unfulfilled vision: the ideal of a country where rivers of humanity merge without losing their distinction, where everyone can make their home in harmony without giving up what is best about their cultural DNA, and without suffering condemnation or marginalization.

When the Washington Heights community comes together to honor one of their own, raising up torches in salute, we see a host of living statues of liberty, an overwhelming affirmation of that bold symbol. Living through a time when American Republicans are abandoning the ideal of "liberty and justice for all" in favor of cruelty and white supremacy, I cannot help but be moved by such an image.

This passionate affirmation of the true American ideal, it happens to correspond beautifully with Christ's call to the whole world: Love your neighbor as yourself. Emma Lazarus's famous poem, engraved upon the Statue of Liberty, make plain what I was taught to believe about America: We say to the world, "Give [us] your tired, your poor, your huddled masses yearning to breathe free...." Until recently, I genuinely believed that this was what the American people valued; today, I stand dismayed to observe how half the nation has seemed willing — even eager — to scrap this radical vision in the name of fear, hatred, exclusion, and self-interest.

But, like Usnavi and his community, I am not willing to give up such a dream.

Even if the United States' vision has been doomed by traitors to its people and its Constitution, by vandals and criminals in Congress, by Antichrists in the churches who advance the cause of so-called "Christian nationalism," the vision of a True America will remain something more powerful than a nation with borders: it will live on as a restless and inclusive spirit ever searching for a new occasion, a new home.

In the Heights suggests that cinema itself can be one of those places where that spirit is alive and well and boisterous and loud, despite the efforts of villains and fools to silence it. Here, we're invited to enjoy a beautiful day in the neighborhood, one forged by imagination, hospitality, and love.

It may well win a whole community of Oscars — and I suspect it will take home the big one.

If it does, I won't complain. The Oscars are (typically, anyway) a popularity contest, and In the Heights is riding an advantage that it could never have seen coming: It has become, accidentally, the occasion that brings people back to the theaters after America's long national nightmare, the pandemic in which a dreamer-hating, immigrant-slandering American President amplified American casualties by hundreds of thousands with his vanity and neglect. How right it seems, then, that the occasion of the Grand Reopening should be celebrated with a whole-hearted and defiant rejection of Trumpist Republicans' inhumane agendas.

Without leaning too hard into political sloganeering, In the Heights is an affirmation that, in the grand scheme of things, true joy belongs to the people who open their arms and open their hearts. Traitors to the American way can take away property, scatter a neighborhood, and build walls that oppress and divide. But they cannot kill this multi-culutral vision, which will ultimately find its fulfillment in God's time, God's promise of justice, God's grace and reconciliation. Evil spirits can break up the block of Washington Heights. Evil spirits cannot erase the beauty of human beings as fully alive as these, nor can oppressors crush the distinctly American spirit flourishing here through the imaginative power of art.

As America's greatest songwriter once sang to his own oppressors, "There is something happening here / And you don't know what it is, do you?"

Wrath of Man (2021)

"From paleolithic man to diabetic house-husband...."

That's how one of the Many Manly Men that make up 19 of 20 important characters in director Guy Ritchie's Wrath of Man describes a perceived crisis of masculinity early in this film.

And it's just one of many lines that highlight what the film acknowledges as the real problem: a world in which too many men think that a capacity for coercive force is masculinity's defining trait, or — worse — masculinity's raison d'être.

Back in the '80s, we watched Bruce Willis's John McClane knock off one bad guy after another and he seemed so cool, seemed to have so much fun doing it. Today, we watch this generation's Bruce Willis picking off the bad guys with pinpoint shooting, and he seems absolutely miserable, a role model for nobody.

And that, I think, is a certain kind of progress.

Don't get me wrong: I enjoyed Die Hard so much I saw it enough to be able to recite the dialogue while it played. It remains the most impressively designed, efficiently scripted, and entertaining cops-and-robbers movie I've ever seen.

But I'm increasingly convinced that the glorification of McClane-types on the big screen have deceived American men into thinking that that a cocky, gun-toting vigilante is basically the Masculine Ideal — a god who has every right to pass life-and-death judgement. And the faster we can dismantle that archetype, the better. It will take generations for American men to grow up, learn what it really means to "be a man," discover what real strength and courage and leadership looks like, and put aside their childish attachment to deadly devices. In short, my ongoing enthusiasm for Die Hard is showing me that I am complicit in the celebration of a toxic genre.

Wrath of Man is different — somewhat. It's a film in which there are no good guys — just guys who commit violence, some for arguably nobler reasons than others. And even those lesser villains, seemingly the best options if anyone's going to be the last men standing, are already too hollowed out ("the hollowed men"?) by violence before this narrative even begins. If they win, they won't enjoy their victory. Any peace they ever had is gone for good.

If you're up for a very dark, very violent movie about armored-truck teams and violent mercenaries/ex-security contractors, you may find, as I did, that Ritchie's latest somehow overcomes its weaker points — screenwriting, action choreography — and becomes surprisingly compelling. It may not be the smartest film in its genre, but it comes with a flicker of conscience. That's worth something.

It follows Patrick Hill (Statham) — who is quickly branded with the nickname "H" because, as Christopher Nolan seems to have noticed, our leading men don't really need names anymore. This is the age of avatars and RPGs, and so who needs a distinctive character name when movies are more about experiences than narratives? Anyway, do I seem distracted from offering a synopsis? I am — the story is not particularly interesting.

Suffice it to say... the iron-jawed action figure 'H' gets a job with Fortico Security in spite of his low firearm test scores, but then quickly silences any skeptics by snapping into a sort of firefight-#BeastMode when one of the company's armored cars gets attacked. 'H' isn't liked by his coworkers, but they're in awe of him after he dispatches the attackers with the efficiency and accuracy of John Wick.

It's not hard to see that 'H' has taken this job for a reason. And soon we learn the unsurprising truth: Someone dear to him was killed during one of these truck heists, and he's hoping to track down the guilty party by riding along and carefully digging around for evidence of an inside job. You can see where this is going. But it takes a while to get there, with 'H' fishing for red herrings that take us through one underworld amusement park ride after another until he finds the guilty party pretty much where we expect him to.

So, no... I'm not here to sing the story's praises. There's a lot about Wrath of Man that feels routine in a Training Day-meets-Heat-meets-John Wick kind of way.

Nor am I here to celebrate its performances. Statham is perfect for this role: He has the sturdy physique of a Bruce Willis action figure, an irresistible double-furrow between his eyebrows that represents his conflicted spirit, and he makes gunplay look like an Olympic event. But you'll notice I'm not bothering to name the supporting cast — it seems to me that those characters are blanks that could have been filled by just about any Hollywood action standbys.

I'm not here to celebrate Guy Ritchie either. I admired some of his craftsmanship here, primarily for how different it feels from the celebratory violence of his past work. I never feel disoriented by the backward-and-forward time shifts or by the action scenes. Your armored-truck mileage may vary: Note that the perceptive and persuasive Bilge Ebiri at Vulture had a very different experience than I did. "There’s a fine line," he says, "between enigmatic and confusing, and [Ritchie] here repeatedly bulldozes past it." And later, "Wrath of Man could have been salvaged had it delivered on some decent action sequences, but once such sequences come, they tend to be either lifeless or unintelligible or both."

I do echo Ebiri's impatience with the film's cringe-worthy dialogue — "macho hothouse banter ... regularly delivered in such half-hearted fashion that we might wonder if we’re listening to a read-through by mistake." There's even a variation here of a line that I hate from Tony Scott's Man on Fire, a quip about a notorious killer: "Let the painter paint!" (At its worst, this movie veers too close to the lurid nature of Man on Fire's revenge plot. That's a film I sincerely disrespect.)

Nevertheless, there's enough here to earn my disclaimer-laden recommendation.

It's Wrath of Man's haunting sense of weariness and despair that intrigues me most. For the kind of story it is — a story about how men who have signed up for and participated in too much violence can end up knowing no other language but violence — I find it intriguingly conflicted. This isn't overly aestheticized with visual cleverness, slo-mo special effects, or tongue-in-cheek Tarantino smart-assery. In other words, it doesn't try to excuse its violence by making it fun. This is more in the territory of Michael Mann's Heat or John Frankenheimer's Ronin, where we're supposed to be appalled by the firepower. (Let me be clear: I much prefer Heat, and this movie's Relentless Killing Machine protagonist is too superhero-ish for me to take him as seriously as I do Michal Mann's corrupt cops and impressive robbers.) I admire its ultimate refusal to glorify any of its characters, even if one's sharpshooting skills are staged to impress.

The overbearing tone of it — like Christopher Benstead's annoyingly relentless and repetitive score — makes it one of those "Once you start down the dark path, forever will it dominate your destiny" films. And everyone involved is already well on their way along the dark path as the story begins. If anyone comes away from this film thinking these gun-loving guys are role models, then they brought problems with them to the movie, problems that are already dangerous.

I watched this on the same day I saw Robert Aldrich's noir classic Kiss Me Deadly for the first time, and while both films are terribly disturbing, they both ring far too true about the world we live in and America's self-destructive addiction to toxic masculinity. That term gets tossed around a lot these days, I know. But I think it's a meaningful term, and one that relentlessly prevents boys and men alike from discovering and fulfilling their potential. It keeps us from learning that it takes far greater courage and strength to pursue the path of Love and Humility and Service than the ultimately corrupting path of Control and Arrogance. You'll only find men who wield guns making meaningful progress on one of those two paths.

Sunday Song: Listening Closer to Jon Batiste and Allison Russell

Interviewed for TIME about his exhilarating, joyous new album We Are, Stephen Colbert's late-night band leader Jon Batiste says, "Stevie [Wonder], I remember him telling me once, ‘Don’t let anybody take your joy away.’ And that really resonated with me. And just in general, the whole aspect of your music being no more or no less than you are as a human being."

Batiste has been a passionate participant in Black Lives Matter protests. Unreliable but popular news sources have consistently painted the protests as violent and reckless, emphasizing images of fires and vandalism, often out of context, and occasionally started by troublemakers who seek to make the protests look violent). Those willing to support (or at least live with) America's traditions of neglect, abuse, and white supremacy have persuaded many Americans (typically, those who are eager to dismiss Black Lives Matter movement as a problem) that the protests are mob-mentality riots, effectively distracting us from evidence of systemic racism. But the truth is that these public appeals for justice have been, for the most part, peaceful and profound. They sound an alarm that the very "liberty and justice" dominating America's propaganda is false advertising — the abuses of slavery have not been erased; they've been reinvented in ways white Americans can easily overlook.

This song highlights the protests as an affirmation of dignity and, even better, a transcendence of the idiocy of America's white supremacist leadership.

He may have won an Oscar this year for bringing the music to the magic of Pixar's Soul, but I'm more excited about this record.

For "WE ARE," Batiste called up his St. Augustine High School Marching 100 marching band and a children's gospel choir from New Orleans for backup. Regarding the marching band, he says, “From its inception in 1951, [St. Augustine High School] was intended for the education of young Black men during a time when there was not an elite institution of its kind for high school students. The marching band is historic and a first of its kind as well, rivalling [sic] college level bands. This school has been a cornerstone in the community for decades.”

At Relix, he says that the song

captures the three prongs that are the basis of the album: the times that we’re in today, the heritage that all the music comes from and my personal narrative. It captures them both narratively and sonically. It’s a real multi-generational narrative ... based sort of casting with my grandfather on the track, giving a sermon. The marching band on the track is my high-school marching band, which is also a school that a lot of my family went to before I was there. It’s a historically Black high school in New Orleans that produces a lot of very active alumni. My nephews, who are 5 and 11, are on the track as well. It’s kind of a disco meets marching band music meets gospel track that speaks to the scope of what I wanted to achieve in the album, which is the synthesis of narratives and the synthesis of different styles of music.

https://youtu.be/MkpvNaBe0mg

Want to hear more about this amazing track? Here's an episode of Song Exploder all about it.

The vocalist for the band Birds of Chicago, Allison Russell will be one of many first-rate acts performing at Over the Rhine's Nowhere Farm festival in October (which Anne and I will be attending to celebrate our 25th anniversary).

Russell's new album Outside Child is one of the very best I've heard so far in 2021. I've enjoyed Birds of Chicago, but now I cannot wait to hear her live.

This isn't my favorite track on the record, but until that one becomes available via YouTube, I'll share this one, which is a knockout on its own. Read about its inspiration in this NPR Music spotlight by Jewly Hight:

https://youtu.be/HNIzvBf6VKA

Overstreet Archives: The Clearing (2004)

As part of a housecleaning inventory, I'm restoring some ancient reviews to the site. My review of The Clearing was originally published at Christianity Today in July 2004.

Looking back, I must have been right about some things, because I haven't heard anybody talk about this movie is more than a decade. If you're one of its defenders, step up and persuade me to give it a second look!

The Clearing starts out like a thriller, but it is far from thrilling.

Pieter Jan Brugge’s directorial debut is watchable only for its talented cast, a trio of formidable actors who make you wonder what drew them to this particular script. It’s a kidnapping yarn that raises a lot of interesting questions and suggests myriad possibilities for conspiracy and surprise, only to cast off those concerns entirely. It ends by slumping into the territory of simple morality plays — you know the kind, where the captive rich man suddenly learns that a few of his priorities are out of whack.

Brugge, who served as producer for Michael Mann’s edgy thrillers The Insider and Heat, deals with some heavy ethical concerns here, and he’s got a lineup of seasoned actors who make the most of uncomfortable silences and emotional outbursts. But the script by newcomer Justin Haythe feels like a rough draft. The characters lack distinctive voices, fitting the typical clichés of the rich businessman (Robert Redford), the businessman’s imperious wife (Helen Mirren), and the grudge-bearing ex-employee (Willem Dafoe).

It is difficult to discuss the plot without “spoiling” what few pedestrian “surprises” it bears — but here is a restrained summary: Wealthy car-rental-business pioneer Wayne Hayes is kidnapped from the driveway of his suburban Pittsburgh home by an amateur criminal named Arnold, leaving his resourceful homemaker wife Eileen to fret over the crisis. The grown children (Alessandro Nivolo and Melissa Sagemiller) come home to furrow their brows over the scarcity of clues, and an FBI agent (Mike Pniewski) moves in to enjoy Eileen’s hospitality and muse over the identity of the kidnapper. Meanwhile, Wayne is forced to trudge hand-cuffed through rugged, rainy, forested terrain with his captor’s gun aimed at his spine. Arnold tells him there’s a cabin ahead, and that he’ll be handed over to a band of crooks who have hired him for the delivery.

The revelation that the dour, disgruntled Arnold once worked for Wayne comes early, so that’s hardly a spoiler. The biggest surprise is just how many interesting directions the storyteller refuses to go with his plot, preferring a simple and, frankly, dull series of conversations that lead to a rather bewildering outcome. Haythe’s idea of an exciting outburst runs like this: “I listened to you, goddamn it! Now you listen to me!”

By its conclusion, it has morphed from uninspired thriller into ponderous drama, but the dialogue-heavy scenes both in the woods and on the home front are plodding and even wearying. It would be a complete waste of time if the actors did not bring some intriguing subtleties to their roles. But as it is, even Mirren’s magisterial gravitas, Redford’s slow-burn intensity, and the unnerving complexities of Dafoe cannot get a fire going in this cliché-soggy kindling.

This kind of sub-level drama is the sort of thing that works in the hands of a subversive master like Roman Polanski. He did just that with a simple kidnapping plot called Frantic, the 1988 Harrison Ford mystery in which a husband goes hunting for his kidnapped wife. After stumbling into a dark and wicked Paris underworld, Ford’s character emerged a changed man, and thus what might have been a happy ending was instead marked by a discomforting chill.

Brugge doesn’t come anywhere close to such intriguing explorations. He teases us with typical thriller conventions — like the photographs of an innocent who doesn’t know she’s being watched, the wife’s discovery of her husband’s secret life, and the package from the kidnapper that holds a nasty surprise. There’s a burst of adrenalin late in the film when Eileen takes matters into her own hands, plunging into darkness to save her spouse. But these too lead to anticlimactic ends. You keep wishing Helen Mirren would transform into her Prime Suspect character, Detective Chief Inspector Jane Tennyson, track down the villain and disintegrate him with her famously contemptuous scowl.

The film’s only real cleverness comes through a style that confounds our sense of chronology until the conclusion. While days are passing at the tormented family’s home, the villain and his victim seem to be running to a different wristwatch. Thus, as the FBI relate the clues they’ve discovered and the messages they’ve received, we’re kept uncertain of Wayne’s fate, even though we find him in the very next scene trudging forward through the trees, healthy but haggard. This mildly interesting device is, in the end, just a gimmick, not part of any meaningful aesthetic. In fact, the film has little to suggest at all, beyond “Love your wife” and “Wealthy people can be hard-hearted and ignorant.”

The enigmatic smile that closes the film might have been a cynical twist, a last-minute revelation, or something deeply meaningful. Instead, it’s just one last moment of “Huh?” in a film that, while unconventional, remains lost in dark and dreary woods.

Persuade Me: Should I see A Quiet Place Part II... or not?

I'm working 50–60 hour weeks these days in my teaching, grading, Zoom sessioning, faculty meeting attendance, and more. I have very little time for movies.

So I am being very selective about what I take the time to watch. Since I wasn't very fond of A Quiet Place — I never reviewed it, so here are my first-impression notes at Letterboxd — I'm not feeling motivated to go see A Quiet Place Part II.

Krasinski’s shrewd less-is-more approach to suspense and tension, and his penchant for crafting gripping set pieces and dreadful dilemmas around well-established rules, have, if anything, grown since the first film.

...

If there’s no one moment at once quite so agonizing and utterly simple as that indelible sequence in the first film with the nail, Part II makes appallingly effective use of something much softer. In one white-knuckle sequence after another, Krasinski shows that he understands that while the CGI beasties may drive the horror, what makes it tangible is what is mundane and concrete.

He adds, however, that it "winds up doing not quite as much with rather more...."

Not quite as much? I was dissatisfied with the first one for doing, well... not much.

Checking the account of Josh Matthews — a friend from The Glen Workshop and a reviewer I follow on Letterboxd — I find him confirming the things I feared I would find in the film:

It does not advance anything about the characters or world from Quiet Place 1. Everything from the original movie is repeated several times: more babies in peril; more metal mangling feet; more monsters who conveniently are as slow or as fast as the film needs them to be.

There is a big fat Zero character development. When I got home from this, my wife asked me if the Emily Blount [sic] character got married. Her point being, did she change, grow, develop, find new relationships, etc.?

And I had to respond, no, she pretty much did exactly the same thing as the first movie.

And he concludes that you might be entertained, but only if "you turn your brain off" for the duration.

Ugh.

Josh Larsen's opening line at Larsen on Film does not encourage me either:

If A Quiet Place was, in part, an ode to farm-to-table masculinity, A Quiet Place Part II doubles down on that ethos. The movie is mostly about its homegrown characters learning to “man up.”

He eventually concludes:

On the surface, A Quiet Place Part II is another expertly crafted and well-acted monster movie, much like its predecessor. ... I only wish A Quiet Place Part II was more interested in interrogating its take on masculinity.

If there's anything I'm no longer interested in spending my moviegoing time on, it's a version of traditional "man-up" masculinity that goes unexamined. Day by day, it becomes clearer that toxic masculinity is one of the root causes of so many things threatening to kill off the good that remains in the world.

Part II is standard sequel stuff.

After his detailed description of an unremarkable film, he describes how his complaints "evaporated the second my gaze drifted up and saw a band of light beaming over the audience and onto a screen 10 times the size of my TV." Ah, so... the joy of returning to theaters was enough for him, and also for the audience: "A few people applauded when the movie was over, and the rest seemed pleased. They were happy to be back."

That's not good enough for me. I've been going to theaters for several weeks now. If I'm going to invest time in movies, I want to see movies that remind me of why I love cinema. And while I love the way films bring people together, it's about more than being in a big, crowded room.

You're invited to try to change my mind... or to tell me I'm making the best decision by waiting around for something better.

I'll share any comments I receive that I find useful... one way or the other. (That means they need to be civil and detailed.)

Overstreet Archives: The Station Agent (2016)

Movies are coming back to theaters — thank the Maker! — and one of the most arresting trailers for big, serious-minded American movies comes from Oscar-winning filmmaker Tom McCarthy. Starring Matt Damon as an oil-rig worker trying to help his daughter who has been imprisoned on charges of murder in Marseille, Stillwater looks to be an edge-of-your-seat thriller.

https://youtu.be/9cq1lPPeMUY

I'm intrigued. But I'm missing the smaller, quieter films that made McCarthy one of my favorite American filmmakers. The Station Agent remains the DVD in my home library that I loan out the most.

So I figure it's a good time to revisit a piece I wrote about the film five years ago, a review I've never posted here at Looking Closer. In 2016, I wrote about The Station Agent for a special installment of my Christianity Today series called "Viewer Discussion Advised." I called it "88 Minutes of Film That Could Save a Life."

You try walking across Seattle alone. At night. Barefoot.

My college roommate did all the time. I didn't understand it, just as I didn’t understand his quiet demeanor, his watchfulness from the edges, or his aversion to typical college-life distractions. His after-dark disappearances intrigued me. So I took to walking with him. I wore hiking boots, and still I struggled to match his incredible stride. As I did, my own pace—in walking and in living—permanently changed. I came to value the rewards of adventures off the beaten path, of being quiet in good company. And I found a compassionate friend.

I think of Michael when I watch Tom McCarthy’s large-hearted 2003 comedy The Station Agent.

And I watch it frequently. I see myself in Joe: the talkative food-truck barista (Bobby Cannavale) who sets up shop next to an obsolete train depot in Middle-of-Nowhere, New Jersey. I think of Michael when I watch Fin (Peter Dinklage): a soft-spoken loner who moves into that depot for the solitude, and who eventually surrenders, accepting Joe’s gregarious, uninvited companionship.

It’s remarkable: Watch how Joe and Fin, like an oversized puppy playing with Grumpy Cat, become complementary. Watch how they transform one other through the simple, shared experience of long walks and short silences.

How might the world be changed if we went strolling, in quiet attentiveness, with those we would rather avoid?

My comparison of my roommate and Fin only goes so far. I don’t know where Michael’s quiet nature came from, but it’s obvious what made Fin so disinclined to talk with anybody: He’s been mocked, abused, and avoided for his dwarfism. He has every reason to withdraw from society, to forget himself in a solitary pursuit—namely, train watching. (Does he love trains because they spend so much time in unpopulated regions of the map?) I cringe, seeing myself in the way some people avoid Fin, someone they don’t understand. I hope I’m not so insensitive as those who stare, who mock, who take snapshots as if he’s a rare animal who escaped the circus.

But I also cringe at Joe’s irrepressible flamboyance, the way he imposes himself on Fin’s silent retreat; the way his vocabulary knows no filter (he’s the movie’s R-rated element); the way he insists on saying grace over a meal in company that would rather not. And yet, as I observe Joe’s pain over his own personal affliction—a family crisis—I find his weaknesses endearing.

How might the world be changed if we went strolling, in quiet attentiveness, with those we would rather avoid?

These two eccentrics aren’t alone: There’s also Olivia (Patricia Clarkson, at her best) an artist who drives the way she behaves, careening all over the place, and who walks like she’s wearing high heels through an earthquake. Olivia relies on prescription medication to cope with a harrowing loss. Olivia needs Joe and Fin. The local librarian, Emily (Michelle Williams), needs friends too, if she’s going to escape her boyfriend’s cruelty. And Cleo (Raven Goodwin)—it’s not hard to guess why this little girl plays all by herself down beside the railroad.

One by one, five suffering souls are drawn together by a magnetic need for wholeness that can be found in a makeshift family.

I don’t know if my roommate was lonely. In a way, Michael was like Joe — he knew himself, and he did what he loved, regardless of others’ reactions. But in other ways, he was like Fin, who, being slow to speak, quick to observe, and committed to walking, drew me — and eventually others — off the beaten path to discover worlds the rest of us overlook.

This, my favorite film from director Tom McCarthy (who made the Oscar-winning Spotlight), is the film I’d nominate as my favorite “love your neighbor” story. It’s the DVD in my home film library that I loan out the most. It makes me want to take Joe-sized risks, to introduce myself to (and say grace with) total strangers, to be a friend to someone on the edges of things, not out of charity, but out of curiosity. I might find hurt and I might find a blessing. Sometimes, they’re the same thing.

I recommend The Station Agent for moviegoers ages 17 and up. It is currently available on DVD and on various streaming platforms, including iTunes, Amazon, Google Play, YouTube, and Vudu.

Questions to Discuss and Consider:

1. At the opening of the movie, we meet Fin and Henry. Theirs is an unusual friendship. Why do you think they understand one another?

2. Fin works at The Golden Spike, a model-train hobby shop, next to a salon called “Scissorhands Salon.” The salon has a bright red awning, like it wants our attention. Might this be a deliberate allusion to another film? Is there any thematic similarity between Fin’s experience of life and that of Edward Scissorhands?

3. Fin. Joe. Olivia. Cleo. How do they complement one another? What is it about their personalities that makes the time they spend together a life-changing development?

4. Trace the evolution of Joe’s curiosity about train-watching. What does he think of it at first? What does he think of it later? How and why does this change occur?

5. How does Fin change over the course of his developing relationships?

6. Talk about the centrality of trains and railroads in this film, and Fin’s preoccupation with the role of trains in American history. What does this have to do with his own life and experience? Why do they appeal to him?

7. Who do you know that draws you out of your routines and expands your world? When was the last time you spent some time with them?

8. How is the time that Joe, Fin, and Oliva spend together different from “community outreach” efforts and the tactics of typical evangelism? How do they gain one another’s trust? How do they reach a point where they are ready to listen to one another and help each other through hard times?

9. When was the last time you invited someone you don’t know very well to join you for a sightseeing walk? Who might you call up today and get to know better?

10. Have you noticed anyone — at work, at church, in the neighborhood — who seems disconnected or friendless? What might happen if you introduced yourself? (Before you presume that you can change their lives, get ready — they just might change yours.)

Overlooked by Overstreet: Get Shorty (1995)

1995 was a feast for moviegoers. MIchael Mann's Heat was setting an epic new standard for cops-and-robbers films. George Miller was setting a new gold standard for big-screen children's stories with Babe. Pixar's Toy Story launched an unprecedented run of feature animation excellence that would eventually become a Disney revolution. Emma Thompson's Sense and Sensibility became an instant classic of literary adaptation. Richard Linklater's Before Sunrise began an ambitious trilogy par excellence. Visionaries like Jim Jarmusch (Dead Man), Todd Haynes (Safe), and David Fincher (Seven) were doing groundbreaking work.

I had just graduated from college, I was living on my own for the first time, I was working full-time for the City of Seattle's Department of Construction and Land Use. The ripple effects of Tarantino's Pulp Fiction were still obvious in new releases like The Usual Suspects and the third Die Hard film — even influencing Scorsese's Casino in some ways. But few imitators were as deliberate in their Pulp Fiction adoration as Barry Sonnenfeld's 1995 smash Get Shorty.

As Anne and I browsed our home library this week for something high-spirited and funny, she took an interest in revisiting Get Shorty. I hadn't seen it in at least 20 years, and I couldn't remember much about it... until I pressed 'Play." It all came back to me so quickly and vividly that I could recite some of the lines along with the stars. I must have seen this several times in '95. And yet I can't find any evidence that I ever reviewed it. So, 26 years later, here are some thoughts.

Entertaining and frivolous, Get Shorty isn't much more than a slick, smooth-riding vehicle large enough to carry a bunch of movie stars doing movie-starrish things in their prime. To borrow a phrase from the movie itself... it's "the Cadillac of minivans."

This is probably the best romp of the Tarantino-Lite genre that blew up after Pulp Fiction, even though it owes just as much to George Gallo's Midnight Run (particularly in its sending of Dennis Farina to the airport in the climactic moments). And it pales in comparison to both films in one significant way: where Tarantino and Gallo know how to make music of profanity, here the abundant f-bombs just stuff the screenplay like styrofoam packing peanuts.

For all of the giddy pleasures of Sonnenfeld's playful cinematography — he's a director who seems perpetually starstruck in the presence of celebrities no matter what movie he's making — there is too much of an 'ick'-factor here for this to ever feel like guilt-free fun. (Note now the young Columbian character Yayo and the prominent Black pimp-costumed drug dealer are the two be shot to death for laughs; how the film's primary villain is such a "likable goofball," but we still have to watch him give a particularly cruel beating to a vulnerable woman so we know he's the guy we should really be rooting against in this amoral morass; and then how our charismatic hero makes a point of expressing his disinterest in working on a movie with a "colored" lead. In 2021, these things ring out as worryingly dissonant in the film's prevailing context of casual white-boy cool.)

Like Palmer himself, this movie is too in love with Hollywood to be memorably subversive. We'll have to revisit Altman's The Player if we want a send-up of studio shenanigans that stings.

The Truffle Hunters (2021)

I am not what they call "a foodie." If I was, I might have known what an Alba truffle was before seeing a movie about where they grow, how they're found, and who finds them.

I'd venture to guess, though, that this confession will also reveal something about my economic status. As The Truffle Hunters reveals, Alba truffles are rare wonders that are sold at high prices and, if they're big enough, auctioned off for a fortune, simply so they can be shaved delicately over plates of gourmet cuisine. I'm a teacher who isn't paid enough to live in the city he teaches in, so... no wonder I've never heard of the Alba truffle before!

While I still don't know what truffles taste like, I now know what it's like to dig for them, how heavily this industry depends on the sophisticated snouts of certain dogs, and how deadly this discipline can be for those same dogs. And the movie is exhilarating whenever we're given, via GoPro cameras, the point of view of the bounding, barking dogs as they scanning currents of air for Alba truffle signals.

In her Washington Post review, Ann Hornaday compares The Truffle Hunters to 2019's Honeyland, a documentary that I found enthralling for how it invited us into the lives of one extraordinary beekeeper and the elderly mother she devotedly served. Jordan Raup at The Film Stage makes the same comparison, and he raves about the hunters as having "so much personality, joy, and life in them."

While I can see some basic similarities between the two films, I think there are substantial differences in matters that really count — and that's why The Truffle Hunters isn't likely to end up on my annual top ten list like Honeyland did. Sure, this movie reveals a similarly remote and unfamiliar world, one that sometimes seems timeless and enchanted. But Honeyland found a compelling narrative, and we became invested in the survival and success of its remarkable beekeeper and her ancient, suffering mother. By contrast, these hunters, while entertaining at first in their eccentricity, ultimately remain stubbornly and annoyingly opaque. Their pasts are uninvestigated. Their lives beyond the hunt are enigmatic. And the single-mindedness of their obsession — well, I found it more exasperating than amusing.

One spends most of his down time ignoring his wife's relentless — and well-founded — complaints and concerns. One talks to and feeds treats to his dog obsessively. One thrashes at a drum set in the great outdoors — for therapy, it seems. One has given up truffle hunting in disillusionment over the corruption of the industry and the violations of personal and professional boundaries, and now he spends his time furiously typing rants about his gripes with culture in general — including, of all things, the lost art of... undressing women? The film comes a little too close to making caricatures of each one, as if they might find fuller lives in a Christopher Guest mockumentary (which, I admit, I would watch). I don't want to go so far as to say the filmmakers are being patronizing (but that's exactly the term used by Simon Abrams at RogerEbert.com). Perhaps they went hunting for treasure in this promising context and this was the best they could come up with. But I can't help but imagine what we might have learned about them, or how we might have loved them, had someone with the curiosity of Agnes Varda been behind the camera.

What's more, I was surprised at the lack of subtext as the film unfolded. This subject matter is glowing with poetic promise. All of the pieces for a meaningful portrait of a corrupt industry are here: The wealthy who spend fortunes to taste rare fungi dug up by dogs from the earth. The judges who have devoted their lives to a particular delicacy and have noses — literally — for the good stuff. The go-betweens, agents who find the talented hunters and apply just enough pressure to get the best of them without burning them out. The hunters themselves who take pride in what they do well, but who really depend on their talented dogs for finding their best discoveries. And the dogs, born with good noses, eager to make their masters happy, and asking so very little in return. It all volunteers to be read as representative of any artistic adventure being spoiled by the cruelty of competitive commerce. It could have been a documentary equivalent of my favorite television series of the last decade: Detectorists. Who could ask for a better metaphor, the vocabulary of truffle-hunting as a way expressing humankind's common search for the sublime?

And, to their credit, the filmmakers seem to be somewhat curious about the great divide between the wealthy dealers of prize truffles, men in suits who live in apparent luxury, and the troubles of the men who are pressured into digging up more and more to the point that they become trespassers. (Worse, their determination turns others into dog-poisoners.) There's something of a commentary on exploitation here; it's just not particularly detailed or enlightening. And I can't escape a vague discomfort, as if there might be a touch of exploitation in the filmmaking as well.

Anyway, The Truffle Hunters offers a pleasant 84 minutes in the woods with some good dogs. And now I know what a dog sees when, wet with rain and mud, it shakes itself off.

Together Together (2021)

Earlier this week, I savored two hours in a surprisingly crowded movie theater. So far in 2021, the theaters I've visited have been almost empty, but now it looks like vaccinated moviegoers are returning to theaters! And they weren't there for a big noisy blockbuster — they had come for an indie comedy: Nikole Beckwith's new film Together Together.

The film follows 26-year-old Anna — played so winningly by a jittery Patti Harrison that I'm hoping to see more of her — on a journey of surrogate motherhood for a 40-something divorcee. His name is Matt and, played by Ed Helms in an endearingly squishy turn, he's a bit of a control freak... perhaps a hint as to why he's alone. What begins as an awkward contract develops into an unexpectedly intimate relationship, and (thank goodness!) not the sort you might expect. As Matt hovers and frets and obsesses about the baby within this attractive stranger's womb, and as Anna struggles to draw healthy boundaries for their relationship, we see a friendship bloom quite unlike anything we've seen in a movie before.

Matt is a character with an alarming lack of boundaries for at least half of the movie, and Helms makes that lack of social grace uncomfortable in a way that will remind many of us of his character on The Office. (Matt is, at times, just a bit too sit-commy in his obliviousness.) But Helms finds enough depth in Matt's longing to be a father to make his weaknesses ultimately endearing. I just wish I understood the character more. He avoids answering a lot of questions about his past, and he remains something of an enigma to me.

Anna makes a little more sense to me, and the nuances of Harrison's performance makes her the more fascinating subject, especially when more is demanded of her in the final act. Unfortunately, a few of the supporting characters around her lean, again, into sit-commy territory — particularly the mopey barista named Jules (Julio Torres) who seems to exist on another planet. It wouldn't have hurt to hear more from Tig Notaro as the platonic couple's counselor; she finds the right balance of funny but understated.

But despite the film's stumbles, here's something I'll remember about it: About 30 minutes into the film (if I recall correctly), I was startled by a conversation between Matt and Anna about, of all things, Woody Allen's perverse obsession with much younger women.

The timing was uncanny. I had only just wrapped up a classroom conversation with my film students about Woody Allen's Crimes and Misdemeanors — in which the most intimate relationship between a male and a female occurs between Allen's own 50-something character and a pre-teen girl. The classroom audience seemed predictably conflicted. They found Allen's Oscar-winning comedy engaging, challenging, and upsetting. They were particularly troubled as they learned about Allen himself, the apparently predatory tendencies that are evident in his own storytelling, and the evidence of his abusive tendencies currently spotlighted in the HBO series Allen vs. Farrow. But the students ended up divided on whether or not we should go on spending time with his films. Some argued that we should not honor him with our attention, much less any dollars required to access his work. Others seemed to think that the work has a lasting value, and that the rewards of considering it and discussing it outweigh any negligible "honor" or dollars that might end up in Allen's pocket.

So you can imagine my surprise, watching Together Together, to hear Anna's swift and merciless judgment of Allen's filmography as unacceptably perverse. At RogerEbert.com, Matt Zoller Seitz counts this among the film's biggest mistakes, calling it "a pointless detour into subtext-as-text" and "the worst thing in the movie by a wide margin because it's inorganic and discursive—a withering critical monologue that should've been saved for the PR tour." I agree that the scene is a bit on-the-nose. But when it arrived, I experienced a sudden rush of relief. Why relief? If Together Together was going to confront head-on the dangers of such substantial age gaps in romantic relationships, that meant I could relax about where Beckwith was taking Matt and Anna. They weren't going to end up together together in that way. (If that had happened, it would have felt like a misguided kind of crowd-pleasing aimed at viewers with the poorest judgment.)

Fortunately, Beckwith has much more interesting possibilities in mind, and that's the saving grace of this film. The conversations between these two are edgy and discomforting enough to keep things interesting, and if you stick with them you will come away with an expanded map of the kinds of stories that are possible at the movies. It's amusing to watch critics wrestling with how to describe what Matt and Anna are experiencing. Seitz says, "[I]t feels wrong to call them 'a couple.' They're more than friends, less than lovers. Well, not 'less than,' because that phrase implies that a romantic relationship is greater than friendship. Then again, is this even a friendship?" I like the way Vox's Alissa Wilkinson puts it: This film "challenges how we imagine supportive relationships, the boundaries of friendships, and the many shapes love can take."

How many shapes has love taken in my friendships over half a century? All but a few of my relationships have been platonic, and nearly 25 years into my marriage, many of my closest friendships today are with women — friendships that feel like what I might have known if I'd grown up with sisters. Why are relationships like these such a rarity onscreen? I suspect it's because of storytellers' tendencies — and, let's face it, studio's tendencies — to want to catch and hold the audience's attention, and there are few lures more enticing than sex. But imagine how we might cultivate a healthier culture if meaningful, non-amorous relationships were depicted more frequently, and the rewards of such realities more recognizable? (Perhaps some would be freed from ideas as fear-based — and as harmful — as Mike Pence's beloved "Billy Graham rule"?)

While I'm not urging you to see Together Together on a big screen — it isn't particularly cinematic, and would play just fine on a small screen — the chemistry between Harrison and Helms warms into a meaningful — even inspiring — relationship, and that's enough to make it worth your time.

I love it when screenwriters cultivate characters and relationships so unique that I can't think of relevant comparisons from other films. Tom McCarthy did that with the friendship between the three leads in The Station Agent. Mackenzie Crook did that in his TV series Detectorists. Beckwith's characters may not come to life for me as fully as McCarthy or Crook's characters do, but her story held my attention to the end because I really had no idea how it was going to end up. Perhaps the best compliment I can give the film is that the cut to the end credits seemed abrupt, and I was immediately disappointed, wishing to go a little farther with both Ed and Anna, just to learn a little more about how things would play out from there. I suspect the sudden conclusion will end up being a productive disappointment; I'll keep thinking about what might be next for Matt and Anna for a long time to come.