Passing (2021)

In almost every aspect, Rebecca Hall's directorial debut Passing is a compelling and challenging film. And, at first glance, it's about an experience that I — having spent much of my white, middle-class, American life largely insulated from an awareness of the struggles of my non-white neighbors — know almost nothing about. That is to say, it is not, for me, what so many people find essential in a movie: It isn't "relatable."

And that is exactly why I need it. Why I find it so absorbing. Why I am grateful for it.

Hall continues my overdue education by introducing me to a literary landmark: Nella Larsen's 1929 novel Passing. And she does so by crafting an adaptation with vision, artistry, and efficiency. Rather than merely turning a text into a screenplay so actors can play the characters, she crafts an impressively immersive experience of light and sound, cocooning viewers in the illusions of the main character: Irene Redfield (played with passion by Tessa Thompson). As we see the world through Irene's eyes (the opening scene achieves this with an imaginative flourish of aural and visual strangeness), we start feeling her anxieties. Then, layer by layer, the willful naïveté in which she has wrapped herself is gradually stripped away.

Irene is a sophisticated Harlem socialite who, married to a successful doctor (André Holland of Moonlight and High Flying Bird), she enjoys a greater measure of privilege than many Black Americans — most, actually. She finds purpose in her charity work for the Negro Welfare League, but she is nevertheless insistent on shielding her two young sons from the daily news of lynchings and other signs that racism is still an American epidemic. Despite her husband Brian's increasing bewilderment over her refusal to face the truth, she wants to shelter her boys from disturbing realities.

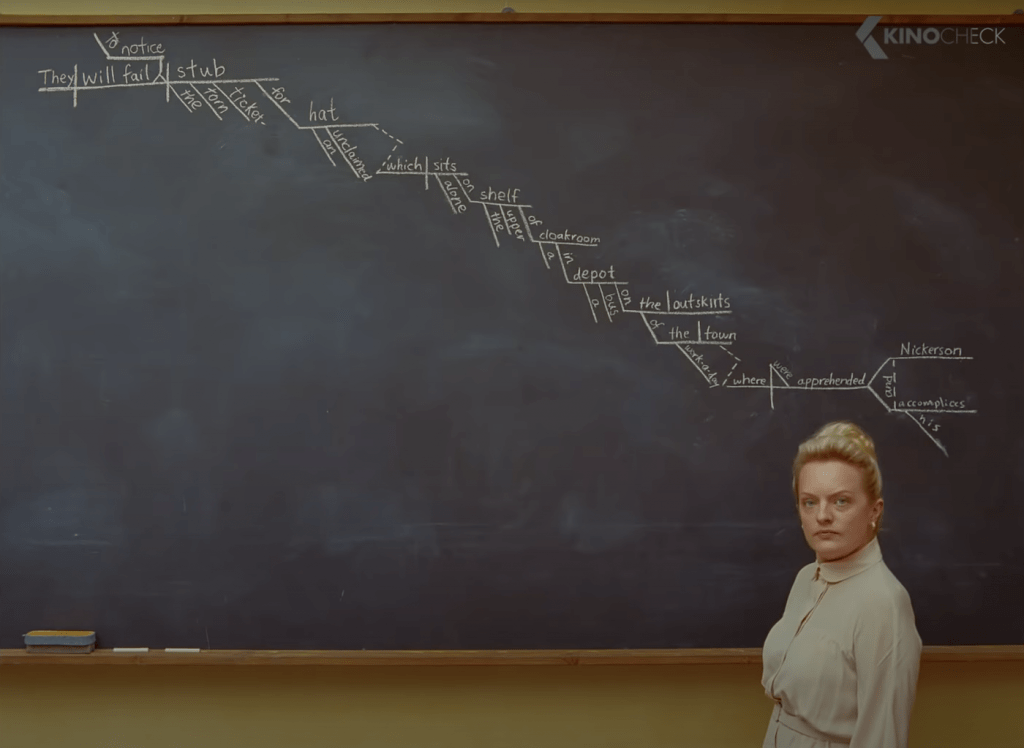

Such is the state of things as the movie begins. But, as I teach my fiction writing students, every narrative arc sets a stage precisely to that the stage can be disrupted. An "inciting incident" soon occurs. Sure enough, Irene's illusory existence, in the first several minutes of the film, is shaken. She has an unexpected encounter with an old friend from school: the feisty and flirtatious Clare (Ruth Negga), who has learned to pass so successfully as a white woman that she has become "happily" married to a white man (Alexander Skarsgård) who smilingly spews hatred for black people. What's more — she's the mother of his little girl.

And, true to that narrative arc formula, a chain reaction of greater disruptions ripple out from the initial strike. Irene meets Clare for tea and discovers, with increasing horror, the depth of her old friend's deceptions. The charade has gone so far that Clare seems to be living in dangerous denial of just how thin the ice has become beneath her feet — to say nothing of what might happen to her daughter, should the truth come out.

So when Clare starts showing up at the Redfield house, charms their community of friends, inspires the admiration of the awestruck Hugh, and goes so far as to make Irene doubt her husband's faithfulness, Irene's anger and resentment grow... as does a fierce longing to live life as freely and fearlessly as Clare, crossing back and forth over those stark boundaries that she would like to imagine don't actually exist.

As you can imagine, it does not go well.

And Tessa Thompson, who is quickly rising through the ranks of my favorite actresses, gives the finest performance I've yet seen from her. My suspension of disbelief wavers quite a bit whenever Negga's Clare is onscreen. Negga's a great actress, charismatic enough to be convincing, but — this is probably more my fault than the actress's — I have some trouble believing she would have "passed" as easily and as successfully as we're to believe Clare has. (So many fans have expressed shock that Rashida Jones is the daughter of Quincy, I can't help but wonder what she might have done in the role.)

Still, so much else is working well that the Hitchcock-ian turns near the end drew me to the edge of my seat. (Watch for a fantastic sequence on a winding staircase that makes Irene's disorientation dizzying.) As Irene's peace of mind implodes, tragedy seems not so much an "if" but a "when" and "what kind?"

I am so glad I saw it on a big screen in a dark theatre. I wish everyone would. In a season of sprawling epics and extravagant spectacle, this is a quiet, focused film that knows exactly what it wants to be and efficiently achieves it.

I have no doubt that many who have grown up white, American, and Christian will recoil from a movie like this, suspecting that it is part of some subversive "agenda" to make white moviegoers feel shame, or to teach some false and unpatriotic view of America. But the fact is that this is a truthful testimony: It exposes some of the symptoms that manifest wherever the disease of hatred is at work. It dramatizes how America's failure to deliver on a promise of "liberty and justice for all" has driven some African Americans to embrace fantasy and denial merely to get through the day, while others shoulder the burden of demanding the respect and opportunities promised them.

I began this review by saying that the film seems, at first, unrelatable to me. My students sometimes respond to challenging art with frustration, and that's the word they give me when I ask them why: "It's unrelatable."

But isn't it one of art's primary purposes to expand our experience, to challenge what we find familiar, to invite us into other experiences of the world? And isn't it essential to the call of the Gospel that we engage our imaginations in the work of loving our neighbors?

And when Jesus comes along saying that the greatest command of all is to love God and to love our neighbor, he too is asking us to pay attention. If we are to love God, we must first stop, look, and listen for him in what is happening around us and inside us. If we are to love our neighbors, before doing anything else we must see our neighbors. With our imagination as well as our eyes, that is to say like artists, we must see not just their faces but the life behind and within their faces. Here it is love that is the frame we see them in.

Is there a way I can connect with – or relate to — a story like this, having lived such a different experience?

I think so.

After all, I was enabled to live — even taught to live — in a way similar to Irene. In childhood, most of my associations with my African American neighbors came from the fact that I only ever saw them as happy and friendly characters on Sesame Street or as mug-shot suspects on the local news broadcasts, programs designed to entertain predominantly white audiences. I learned by example to ignore the ugly reality of racial violence around me. Just as Irene tells her husband to stop talking about the daily, front-page-news lynchings that are breaking his heart, I was taught to change the channel when public television showed me present-day protests over inequality. I knew the name Martin Luther King Jr., and I sensed some measured respect for him. But I was more familiar with a sense of grim disapproval for the occasional evening-news sight of Black Americans marching, waving signs, and shouting for change. This was treated as disruptive, as inconvenient, and — worst of all — as ungrateful. Instead of reckoning with reality, I was taught to look back admiringly at Abraham Lincoln, the good Christian who had "solved" the problem of slavery with his white-savior goodness. But I was deeply naive, and conditioned — in just the ways white supremacists would have wanted — to think that Black and brown-skinned Americans were less intelligent, more inclined to crime and violence than people like me, and not really part of "God's country."

Thus, the struggles of Black Americans remained only a vague concept to me. We didn't study Black scholars, read Black authors, or speak of them much in my 99% white school, my 99% white church, or my 99% white neighborhood. They were rarely ever represented in the art that surrounded me except in rare appearances as residents of that place called "the Mission Field" where charity cases lived, people who needed my white-savior, white Jesus help.

And I welcomed the convenience of my cocoon. My education was incomplete. And it wasn't just a case of my schools and churches failing to show me the whole picture; it was a case of active avoidance, a case of deliberate denial. An ache of doubt began to swell inside of me — a still, small voice of conscience that I believe was the work of grace, not anything I can boast of. I was comfortable among white conservative Republicans who professed Christianity and prioritized the memorization of verses about loving our neighbors and seeking justice, but who seemed to think that the only way to do this was to send money to missionaries far away, a convenient way to "serve" without discomfort. Meanwhile, our fears and dismissals became ever more obvious to me. Vocabularies of "us" and "them" turned bitter in my mouth.

In other words, though I could "talk the talk" of true Christianity — beliefs inspired by the teachings of Jesus, the brown-skinned Messiah — I was, in many ways, just another imposter who knew how to live in denial. I was only "passing."

Thus, I am grateful for movies like this one. Passing, like Jenkins' If Beale Street Could Talk, Lee's Do the Right Thing, Butler's Parable of the Sower, and Morrison's Beloved, is a meaningful invitation to better understand, and thus learn to love, my African American neighbors. It asks me to confront "unrelatable" experiences so that I can work on waking up from an illusory substitute for the Gospel, a toxic worldview that runs so rampant in this fearful, hateful nation that I call home. As promised, the Truth, even though it is disruptive — because it is disruptive — will set us free.

https://youtu.be/EMHZSmqyn1A

The French Dispatch (2021) (Part One)

If you're here for a traditional film review of Wes Anderson's The French Dispatch — one with a full, detailed plot synopsis — you'll have to read other reviews. I don't envy any film critic who has tried to make sense of this story's myriad narrative threads; I'd be hard-pressed to think of a movie with a more complicated plot.

Suffice it to say that the movie's a tribute to — or better, a revelry in — art-and-culture magazines like The New Yorker.

It begins with the occasion of a legendary editor's passing: R.I.P., Arthur Howitzer Jr. (Bill Murray, of course). Howitzer has been the master of The French Dispatch — an American magazine published in a fictional French town of Ennui-sur-Blasé. He leaves behind a crowd of world-famous journalists. And they're appropriately despondent, knowing that his departure marks the end of more than just a magazine.

Then, we jump back to the beginning of production for the Dispatch's final issue, and follow a motley crew of adventurous journalists on various missions to capture big stories.

Each story is detailed enough to stand alone as a memorable Wes Anderson feature:

- a whirlwind tour, with a bicyclist guide (Owen Wilson), of Paris's least-romantic sights, sounds, and smells;

- a portrait of an incarcerated serial killer (Benicio Del Toro) who becomes an art-world sensation when he paints abstract nudes of his prison guard and muse (Lea Seydoux);

- an investigative report on a student protest over the separation of boys' and girls' dormitories, in which the journalist (Frances McDormand) becomes romantically involved with her very young subject (Timothy Chalamet, of course); and

- a frantic rescue mission of a politician's son from a dangerous gang, in which a gourmet chef (Stephen Park) plays a crucial role.

Wait — did I just contradict myself? Isn't that a plot synopsis?

Not hardly. Those lines barely scratch the surface of this deep well of storytelling. But there's so much more than storytelling to talk about when it comes to The French Dispatch. The first viewing may feel less like moviegoing and more like an immersion in a Wes Anderson amusement park. It's an astonishing — and surely, for some, off-putting — cinematic achievement: it is, by far, the most extravagantly decorated, narratively complicated tapestry of eccentric characters, accelerated storylines, cinematographic techniques, shifting aspect ratios, and elaborately mapped environments that this polarizing filmmaker has yet constructed.

I say constructed rather than filmed because the movie feels more a massive contraption than a movie. I've become preoccupied with tracking how other cinephiles are attempting to describe the experience:

At RogerEbert.com, Sheila O'Malley compares The French Dispatch to the insides of an elaborate clock: "a dizzying array of whirring intersecting teeny tiny parts" that "ticks forward relentlessly, never stopping to breathe, barely pausing for reflection." At Vox, Alissa Wilkinson, bemused but unenthusiastic, says it's "nostalgic, a little weird, visually sumptuous."

And The New Yorker's own Richard Brody, ecstatic, writes with an effusive energy that recalls the rush of the movie itself:

The French Dispatch contains an overwhelming and sumptuous profusion of details. This is true of its décor and costumes, its variety of narrative forms and techniques (live action, animation, split screens, flashbacks, and leaps ahead, among many others), its playful breaking of the dramatic frame with reflexive gestures and conspicuous stagecraft, its aphoristic and whiz-bang dialogue, and the range of its performances, which veer in a heartbeat from the outlandishly facetious to the painfully candid. Far from being an inert candy box or display case, the movie bursts and leaps with a sense of immediacy and impulsivity; the script ... bubbles over with the sense of joy found in discovery and invention. Even its static elements are set awhirl — actions and dialogue performed straight into the camera, scenes of people sitting at tables joined with rapid and rhythmically off-kilter editing, tableaux vivants that freeze scenes of turmoil into contemplative wonders — and take flight by way of a briskly moving camera.

For all its meticulous preparation, the movie swings, spontaneous, unhinged....

And he's just getting warmed up. Soon, he'll issue a warning: "On first viewing, audience members run the risk of having their perceptual circuits shorted."

Consider yourself doubly cautioned. I come away from my first viewing reeling at the thought of the amount of writing, art-department brainstorming, storyboarding, set construction, and editing that must be involved in a production like this. We are finally seeing what Wes Anderson will do when fully unleashed — apparently able to cast any actor he wishes, drawing from what appears to be a limitless reservoir of resources. With most talented filmmakers, the success of a modest early feature (in this case, Bottle Rocket) leads to an increase in their resources, and that too often leads to a loss of aesthetic focus and a dilution of artistic vision. But every time Anderson's movies get bigger, they show that he becomes even more involved in every detail, even more enthusiastic about a design that demonstrates structural integrity. (For proof, consider the massive book on Anderson's Isle of Dogs written by Lauren Wilford and Ryan Stevenson, which will convince you that a whole film-studies program could be built on just one of Anderson's movies.)

Sure, it's worth asking if Anderson's exponential leaps into projects of ever more bewildering complexity won't ultimately alienate most audiences, even some of his longtime fans. How many viewers are willing to give these movies the kind of long-term attention they require?

But one shouldn't fault great literature because readers have poor attention spans. Films like The French Dispatch are not designed for "love at first sight." To see this movie is to be invited into a relationship; it's not meant to be a one-time transaction. If you don't understand that going in, well... you may want to stick to more elementary entertainment. Anderson is devoting every resource at his disposal to the realization of grander visions, and they've become so ambitious that the results are becoming more like museums than paintings, more like restaurants with multi-faceted menus than mere meals.

Bringing to life a big-screen city unlike any we've seen before, Anderson has built himself the biggest Parisian playground since Jacques Tati doomed himself to financial ruin erecting the stages for his masterpiece Playtime. And, after cinephiles have had years to examine many aspects of its architecture and find their way into meaningful engagement with its characters and storylines, The French Dispatch may have a reputation in film history similar to Tati's masterful folly. The first viewing is like catching an aerial view of a bustling city. Second, third, and eleventh viewings will draw us to descend into the avenues, pick particular characters for our focus, follow them around, and discover subtler nuances in their stories.

So, did I emerge from this first screening of The French Dispatch enthusiastic and overjoyed? No, I'm not there yet.

At this writing, I've seen the film once, and I'm dizzy. It's possible, I suppose, that I'll end up more frustrated than fond of this film. It's as preoccupied with its own architecture as it is with intricate storytelling, so labyrinthine and relentlessly busy that it makes The Grand Budapest Hotel look as quaint as a single episode of Only Murders In the Building.

As the most narrated of any Anderson film, with a screenplay that must be the size of an encyclopedia, it’s seems more exhausting than exhilarating. And it's not unreasonable to sniff something vaguely show-offy about a movie like this so overstuffed with celebrities who only get a line or two. It's as if this Willy Wonka is just so high on his own candy-colored Rolodex that he can’t resist reminding us how many big names will do whatever he asks on a moment’s notice. He’s on a sugar high of Pure Imagination, and it’s almost impossible to discern between self-indulgence and genius.

But I won't say I'm disappointed — because I've learned my lesson.

I went from scoffing at Anderson's The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou at my first viewing to blinking back tears of joy by the third viewing, where I felt a deep and soulful connection to its melancholic antihero, and started sensing profound poetry in what had at first felt like reckless tangents. I came away from The Grand Budapest Hotel complaining about how I wanted Anderson to go back to intimate, character-focused storytelling, but now I eagerly plunge back into its storybook to enjoy new epiphanies every time. But this first viewing of The French Dispatch felt like flipping through a massive coffee-table-book treasury of The Best of The New Yorker; I suspect that I'm holding in my hands a treasure trove of big-screen reading that will keep me busy for years to come.

So, if I were you, I'd be profoundly skeptical of any immediate assessment of The French Dispatch from a one-time viewer. Critics have been given a whirlwind golf-cart tour of Disneyland without being granted the time to explore, to spend time in the various exhibits, to go on the rides with friends and strangers. In my opinion, we're not ready to proclaim a judgment. I know because I used to be one of those impulsive, first-viewing judges, and I ended up retracting so many of my first-impression reviews, realizing to my regret that they weren't really reviews at all, but reactions. Wes Anderson deserves better than reactions. Considering the amount of love lavished upon this production at every level, The French Dispatch deserves our curiosity, our careful attention, and a long-term commitment. I'm confident it won't let us down.

[Coming soon: Part Two — my second experience of The French Dispatch. This time I was better prepared.]

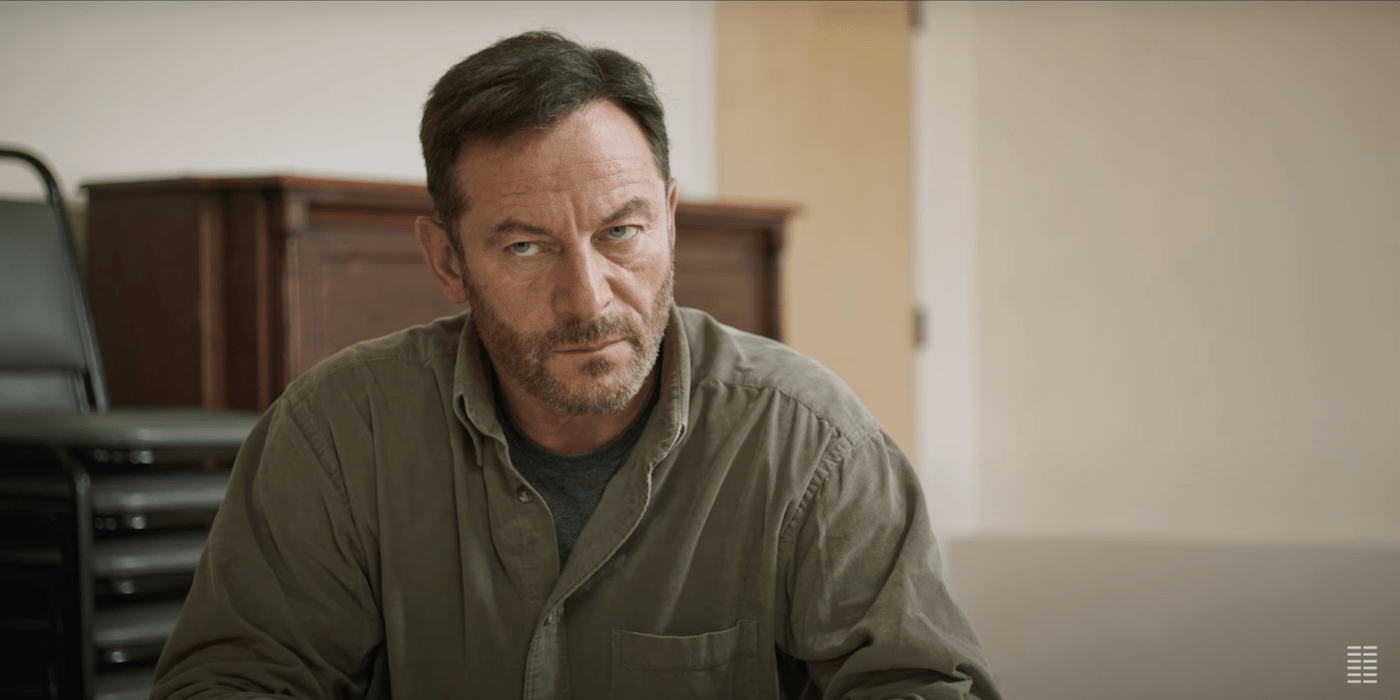

Mass gives us a close-up of one of the hardest conversations ever imagined

Last Thursday, I saw a massive science-fiction epic that shakes cineplex walls with its roaring soundtrack. Onscreen, bombings blaze, storms roil, and subterranean monsters erupt from desert sands. Dune represents the work of people the number of which might equal an American city. And I loved it.

On Friday, I went back for more. This time, I saw a seven-layer cake of a film, a comedy about several journalists in Paris pursuing dramatic stories — one about a serial killer turned art sensation, another about student protests against oppression, and a third about how a brilliant chef and a persecuted journalist are drawn into a dangerous rescue mission. Every fantastical frame is stuffed with decoration, creating a busy wonderland of whimsy and wit. The cast may have been larger than the casts of all of the other films I've seen this year combined. And I loved it.

Cinema makes both of those experiences possible. Watching such ambitious visions, one right after the other, was both exhilarating and exhausting.

But cinema can also do this:

On Saturday, I saw a moment-to-moment imitation of life in the world as we know it — four people, sitting in a church basement, in a closed room, talking for almost two hours. They sit in ordinary folding chairs, at a round plastic table, and face each other. They are often quiet and still, their faces etched with unfathomable grief, their hearts like active volcanoes: scarred, smoking, quiet, then exploding with questions and grudges and laments and needs. They each unpack the jagged pieces of their broken lives, wreckage that no one has the capacity to reconcile.

The word raw is commonly applied to such emotional exhibitions. Actors, we're told, live for opportunities like this — playing three-dimensional humans who careen between quaking rage and simmering silences. And it's as if audiences — critics included — are so uncertain about what to do with such discomforting, uninhibited performances that they reach for the easiest vocabulary: Let's give them awards! Then we can feel like the transaction is complete, and we can move on to something more crowd-pleasing and satisfying!

The harder thing to do is to is resist the impulse to dismiss it as Awards Bait and, instead, accept the film's invitation to wrestle with difficult questions and reckon with these depths of suffering. In this case, though, I'd argue it's well worth it. This film — Mass, from director Fran Kranz — earns the term "harrowing," but it is well worth the attention. I'm hard-pressed to think of a more difficult conversation I've ever seen dramatized at the movies.

Mass plunges us right into a complex crucible of testimonies: Jay and Gail (Jason Isaacs and Martha Plimpton), the traumatized parents of a boy slain in a school shooting, and the two people they find most difficult to face and yet most essential in addressing the razor-blade questions eviscerating their hearts and minds: Linda and Richard (Ann Down and Reed Birney), the similarly traumatized parents of the boy who fired the gun. None of them have any reason to expect welcome, acceptance, attention, or respect.

And yet, they come to this place — non-religious people in an Episcopalian church, in an ordinary room that will look familiar (perhaps painfully so) to anyone with Sunday School history, a statue of Christ Crucified on the wall, and crepe paper "arts and crafts" mimicking stained glass on the windows. Chairs. A round table. A box of tissues. These provide what Alissa Wilkinson (Vox) calls "a gentle, grace-filled frame around an almost unspeakable tragedy."

The room becomes an arena for an awkward, simmering, unfathomable outpouring: Grief. Rage. Truth-telling. Hope. Some share photographs. Some tell stories. And the words they speak are only half of the battle. This a story of faces. Hands. One character sips from a water bottle, the sound of plastic crumpling in the hand like the sound of their fragile heart being crushed inside them. One offers an almost useless bouquet of flowers.

It's easy to focus on the two marriages, the four witnesses. And I could go into great detail about the hellscape of anguish they must navigate together in their hopes of arriving at some kind of truth, some kind of relief. But that is best experienced in the theater without a map, being surprised by revelations, stunned by outbursts, challenged by questions — with Jesus silently suffering in the background, battered and bloodied on the crossbeams of torture, that ultimate symbol of both injustice and sacrificial love.

And besides, I need to look beyond the leads to note the essential work of the supporting cast, who appear at the film's beginning and end. I recognize the remarkable "church lady" eagerness of Judy, played by Breeda Wool, as she busily multi-tasks her way around the church building after hours; Matt Zoller Seitz (RogerEbert.com) accurately describes her as "helpful to the point of being unnerving." (I suspect most longtime churchgoers, if they're honest, recognize the sort.) Judy has help of a sort from a young and disgruntled assistant Anthony (Kagen Albright), preparing the way for a self-serious and preoccupied social worker (Michelle N. Carter) to assess the space and identify potential disruptions, like a Secret Service agent scoping out a space for risky Presidential visit.

Without these supporting characters, the four suffering parents don't have a safe place to struggle. And the mix of awkwardness, uncertainty, anxiousness, and tenderness in their engagement — both upon the guests' arrival and in the strangeness of their departure (how do you conclude something that offers no closure?) — makes the whole situation feel so much more real, and seem so much more possible in a world where we need more face-to-face relationships, more long and patient and hard conversations, more truth-telling, more listening, and more forgiveness.

[Note: You'll be tempted to skip the big screen and watch this at home. I'm glad I didn't. If you do, resist, if you possibly can, any urge to hit 'PAUSE.' Its power is in its sustained, uninterrupted conversations and silences.]

I'm relieved to report that, in spite of its subject matter, Mass manages to bypass the roaring waves of political posturing and convenient social media speeches about violence in schools, and gives us a glimpse behind walls of silence to questions and concerns that often don't make the headlines. This movie isn't driven by a need for accolades and honors, nor by some sense of Timely Relevance within a context ripped from the headlines. Rather, Kranz's film is a dramatization of a courageous struggle with questions we don't know the answer to. These testimonies of trouble may not lead these wounded souls to answers, but it does lead them to some unexpected new perspectives and, more importantly, to freedom from the very real threat of lifelong resentment and corrosive hatred.

Someday, some will discover Mass, then look up the Oscars for 2021, scratch their heads, and wonder — why was this overlooked? Was it even released in theaters? Others will watch it and find the honesty, the realism, the raw human emotion of it too much to endure. Others will watch it and receive its blessing: a vision of a kind of conversation that may be the only hope for families, churches, communities, and nations divided by trauma, loss, and rage. They may never be the same.

In fact, I'm confident that this will eventually rise from obscurity and earn a place on that short list of films that provide occasion for conversations about faith, faithfulness, and forgiveness without sentimentality. I'm not thinking of those films that are typically branded as "Christian." I'm thinking of films like Calvary and Of Gods and Men. But this film is set on an even smaller and more intimate stage.

When I mentioned on Facebook that I was thinking of Mass this way, someone seemed surprised that I would think of this film as "Christian" at all.

But I can't witness people gathered around a table, working their way from rage and hatred through confession and grieving toward the possibility of forgiveness, without interpreting it as a film about God at work. And when it takes place with the figure of Christ crucified hovering over it all, that is almost too heavy-handedly underlining what is really happening here.

You may have what it takes to sit through the intergalactic warfare of Dune — and even go back to see it again a few days later. I did. I will. You may have what it takes to revel in the deliberate excesses of The French Dispatch and discern a pulse of real human feeling within its many layers of marzipan and madness, and want to see it again. I did. I will.

Are you interested in — are you willing — to buy a ticket and sit and listen to a conversation between two fathers and two mothers about the kind of pain that people across the country are struggling with every day, every hour? I'm glad I did. I hope you will. Of the three films I saw this weekend, Mass — with its cast of less than a dozen, made by a modest list of artists, released quietly without a massive marketing campaign — may be the one I'll think about most often. And I'd argue that it's the one with the potential to offer the most meaningful illumination in a darkening world.

Overstreet Archives: The Fits (2016)

A big deal was published today at Bright Wall Dark Room. I'm so excited about, and moved by, Joel Mayward's outstanding new appreciation of The Fits — one of my favorite films of the 2010s, and one of the greatest directorial debuts by an American director I've ever seen — that I decided to join the party: It's time to bring back my original Christianity Today reflection on the film here at Looking Closer.

I've been raving about The Fits since I first saw it five years ago this month. In my Letterboxd film diary, I've posted notes on it no less than eight times. And it has gradually risen in my Favorite Films of 2016 list — 2016 was a great year for cinema — to join Jim Jarmusch's Paterson and Kristen Johnson's Cameraperson in a three-way tie for the top spot.

Granted, the audience I was writing for when I reviewed the film was quite different than Mayward's audience (the cinephiles like me who subscribe to Bright Wall Dark Room). I was writing for readers of Christianity Today, many of whom are suspicious of movies and more concerned about morality than art. My goal was to introduce them to this film in such a way that they might find the courage to try something unusual, even though it was likely to challenge them and even disturb them with its ambiguities, mysteries, and implications. I also faced other challenges: a much more restrictive word limit, a need to avoid spoilers, and a directive to write in such a way that I would set people up for a Discussion Guide — one they would hopefully use with their family or friends after watching the movie.

Still, I'm grateful I got the chance, as soon as the film was available for streaming, to scratch the surface of all I had to say about Anna Rose Holmer's mesmerizing and meaningful film.

Here's that column, in its original form, published January 23, 2017 at Christianity Today.

If you’re looking for a film that inspires lively conversation, you’ve got to check out The Fits. Anna Rose Helmer’s debut feature film runs a brief, but intense, 72 minutes, leaving plenty of time for discussion and debate afterwards. It caused a stir last year at Sundance, and critics have been talking about it ever since. Fortunately, Amazon Prime subscribers can currently stream it for free — and for the rest of us, it’s available for rent or purchase.

Here’s the premise:

Toni (played by an astonishing discovery named Royalty Hightower) is a soft-spoken but hard-thinking 11-year-old girl who, in her lonely afterschool hours, is wandering unwittingly toward an outbreak of mass hysteria. She spends her days drifting around her Cincinnati community center, moving back and forth from her brother Jermaine’s boxing practice (where she is an awestruck observer in the world of boys) to the territory of the Lionesses, a highly competitive and hierarchical dance team (in which she is an awkward beginner).

Sometimes, it’s challenging: We ponder Toni’s lonely silences and awkward exchanges with girls younger and older. Sometimes, it’s exhilarating: We watch her slowly begin to find her feet in an unsteady environment. And sometimes, it’s unsettling: Toni witnesses other girls on the Lionesses’ dance team succumbing to sudden “fits” that resemble strokes, seizures, sexual ecstasy, or spiritual epiphany.

And that’s the fun of the after-movie discussion: What do these fits mean?

I showed The Fits to film classes at both Seattle Pacific University and Northwest University this month, and each time my students filled an hour (and could have kept going) with difficult questions, personal insights, and surprising interpretations.

They have all kinds of ideas. With the toxic water of Flint, Michigan, and the endangered water of the Standing Rock community still making headlines, some think it’s a film about the environmental dangers suffered by vulnerable low-income communities. Others see it as a poetic representation of adolescence and all its awkward rites of passage (particularly for women). One of my students observed, “While [puberty] can be a scary thing, it creates unity in a group.” Some decided that The Fits is about “finding your voice” or “discovering your calling,” or even struggling with questions of sexual orientation. A few talked peer pressure—especially pressures related to sex. One student summed it up as a story about “the psychological need for belonging and acceptance.”

I introduced them to Alissa Wilkinson’s personal reflection on the film, previously published here in Christianity Today. Wilkinson writes that The Fits “captures—without judgement or condescension—the strangeness of being part of a microcosm where your place in the pecking order is determined by something nonsensical and mystical, something adults don't understand and other teenagers outside your group view disdainfully.”

Explore further and you’ll find that the filmmakers were considering “historic cases of hysteria and mass psychogenic illness” from the Middle Ages to as recently as the 1960s. For Holmer, the film served primarily as “an allegory about the power of dance and what it means to really give into that power.”

All of these interpretations have merit. By refusing to reduce her movie’s mysteries to a simplistic “answer,” Holmer invites us to empathize with her characters in a variety of ways. The movie’s ambiguities make possible a fusion of palpable dread and visceral intrigue that might remind us all of the distinct ways in which we have experienced adolescence, or alienation, or rites of passage, or self-discovery.

It might even remind us of our innate longing for communion with God.

What fascinates me most about The Fits is its insistence that something more than hyperactive hormones are happening here. Something mystical is occurring—and it’s descending upon these young people from somewhere outside of themselves. The fits might come from a connection with a higher power of some kind. Toni looks heavenward as if receiving signals. And who hasn’t felt that desire to break open and commune with something larger, something mysterious, something that would reveal your meaningful place in this world?

It takes me back to my own experiences in a competitive choir at Portland Christian High School, where our director — who had previous experience as a drill sergeant — coached, lectured, and even berated us in his drive for excellence. Some couldn’t take it, humiliated and hurt. Others, for better or worse, pressed on, almost convinced by his claims that if we hit our notes just right and achieved a sublime harmony, we might see the heavens open.

Toni sees young women knocked down, even humiliated, by these fits. But there is another possibility—one that involves a sort of cooperation with mystery. Hardship can arrive in ways that ruin us. But the Scriptures say that God’s strength is made perfect in weakness. When calamity strikes, we can embrace it as an occasion for God to “make all things new.” The result of such collaborative formation can be the revelation of something fierce and beautiful. When we open ourselves to the Spirit, the result might be a Work of Art.

For Discussion:

- What do you think The Fits is about? And why? Point to specific images, lines, and scenes to back up your interpretation.

- The film has a distinct musical score, in which an abrasive out-of-tune clarinet and powerful percussion—both arrhythmic and syncopated—play important parts. What do these musical accents add to the film? What might they represent?

- Consider the film’s wardrobe: What do the characters wear, and what does that represent for them? How does Toni’s fashion sense change, and what does it mean?

- What other films about adolescence or transformation have you seen? How do they compare to The Fits? (I find myself thinking about 2015’s Girlhood, 2010’s Black Swan, or even Beyonce’s visual album Lemonade at certain points.)

- Toni seems uncertain, fearful, even lost for stretches of this movie. At what points do you notice changes in her? What provokes them, and how do they manifest?

- How are the fits different from one another? Consider especially the last one we see: How and why is it distinct?

- The film’s big finale is, well… surprising. But look back at the whole film: How were we prepared for that revelation? What images or moments did the filmmakers use to strategically and subtly prepare us for that?

- We don’t see a lot of movies that focus on the experience of young girls. How is this one unique? Does it portray women differently than you’re used to? How? Is it a respectful portrayal?

- What is your personal connection point with Toni? What in your own experience enables you to feel empathy for her? Can you think of moments in your life that were pivotal and transformative?

Titane (2021)

If you've been reading reviews for long, you're familiar with my annual rants about the Oscars' lack of credibility and the Academy's embarrassing record of prioritizing popularity and politics over artistry. And you may have noticed that I often point people to international film festivals — particularly Cannes — as examples of how, elsewhere in the world, great art is not only recognized but celebrated.

This year, my admiration for Cannes jury discernment has taken a hard hit. They've given Titane, from French director Julia Ducournau, the Palme d'Or.

The Golden Palm! This is the award they gave to transcendent titles like Scorsese's Taxi Driver and Coppola's Apocalypse Now; Wenders's Paris, Texas and Malick's The Tree of Life; Olmi's The Tree of Wooden Clogs and Campion's The Piano; the Coens' Barton Fink and the Dardennes' Rosetta; Leigh's Secrets and Lies and Weerasethakul's Uncle Boonmee Who Can Remember His Past Lives! Granted, I've sulked over a few Cannes jury choices (particularly the reportedly pornographic Blue is the Warmest Color, which sparked charges of abuse against the director). But I'll rush out to see a Cannes award-winner over an Oscar winner on almost any occasion.

And here's a rare occasion: They've given this award to a film directed by a woman! Yet another reason for celebration, right?

Alas, no. This time I'm going to recommend you give the 2021 Palm winner a pass. Why?

It's complicated.

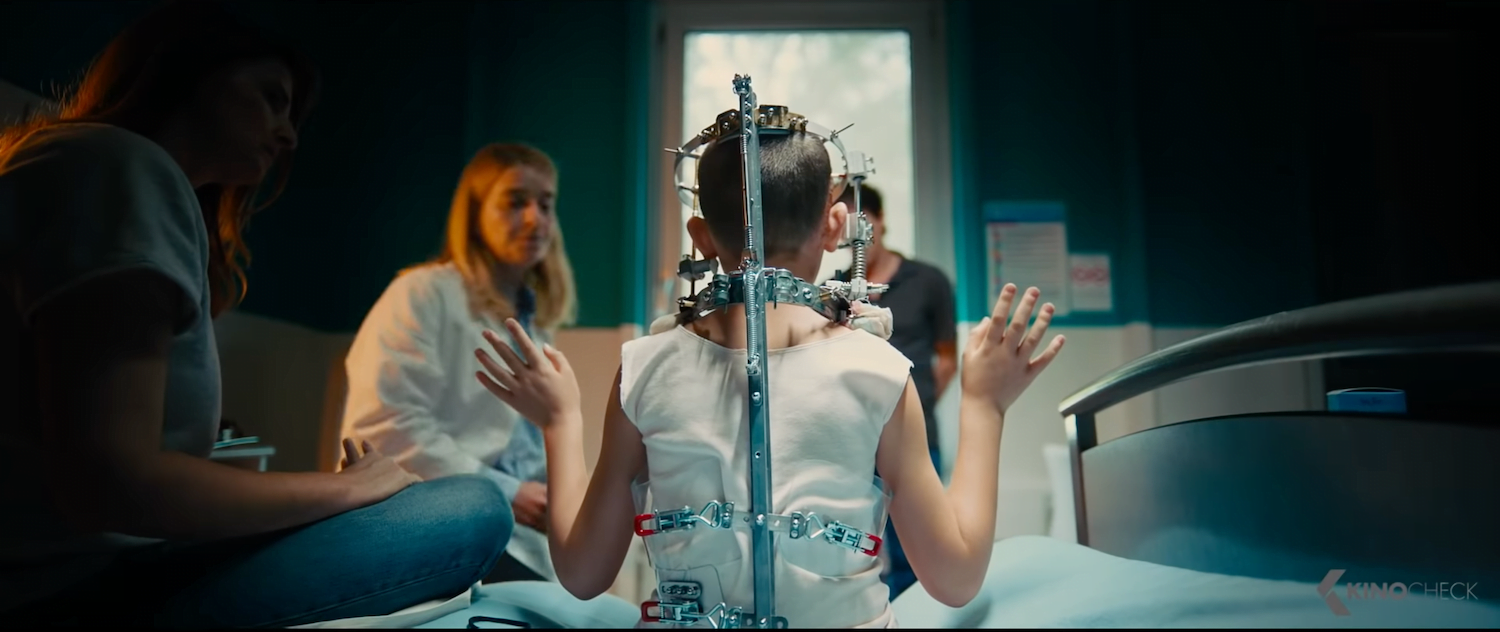

Let's consider the narrative — a rollercoaster, wild and strange. Titane traces two painful journeys, both of which are, "on paper," interesting. I'm not troubled by what their stories are about; rather, I'm troubled by how the stories are told.

First, we have the growing-up of a girl named Alexia (Adèle Guigue), who is strangely (inexplicably, really) obsessed with automobiles. This is true even before she's in a car accident that results in surgeons implanting a metal plate in her head. Later, as a grown woman (Agathe Rousselle), she's drawn to motor vehicles sexually — yes, sexually — and to such psychotic extremes that anyone who disrupts her obsessions is likely to end up impaled on the knitting needle that she keeps sheathed like a samurai sword in her hairdo.

That's enough of an interesting premise for any psychological thriller or body-horror nightmare. Artists — filmmakers especially — have been intrigued by the seductive nature of technology since movies were first made, and the subject raises questions we need to investigate. I'd be intrigued if I knew that idea was being explored in a conscience-driven vein, like something we might see from Claire Denis (her High Life took us dark psychosexual sci-fi turns), Guillermo del Toro (with his penchant for stories of persecuted outsiders), or the Davids Lynch or Cronenberg (with their willingness to explore the darker recesses of human nature for purposes of caution or lament).

But wait — there's more.

Second, we have Vincent (Vincent Lindon), the commander of a squadron of firefighters and the father of a long-missing boy named Adrien. The crisis has probably influenced his leadership; the men of his muscular brigade regard him with a mix of fear, incredulity, and humor. Driven to distraction, he enjoys losing himself in their trance-like dance parties. Worse, he has become addicted to some kind of drug that reinforces or amplifies aspects of his masculinity — perhaps to help him compensate for the sense of powerlessness that stems from his irreparable loss.

Again, this sounds like thematic territory we've seen artists like Denis explore before (Beau Travail, for example).

But we're just getting started. As Alexia becomes more and more desperate in her quest to be loved and understood, rather than cured of her alarming lust for chrome and machinery, she becomes more and more murderous, moving from the swift stabbing of a stalker to the full slaughter of a girlfriend's housemates. Before long, she finds her face is on wanted posters alongside pictures of missing persons — and so, of course, she decides that the rational thing to do is disguise herself as one of them. She happens to choose Vincent's missing son, Adrien. This involves a disfiguring body wrap, a severe haircut, and more.

But there is still no resemblance between Alexia and Adrien. Nobody could mistake them. Nobody. Especially Adrien's father, who soon finds himself staring intently into Alexia's anxious face. He may guess that this is a stranger, an opportunist. But he cannot guess the darker secret: that Alexia is pregnant with — are you ready for this? — the child of, yes, an automobile.

Nevertheless, Vincent, deep in his depression, decides to take Alexia at her word in a moment of ... what? grief-triggered delusion? Implausible as it all is, they begin to make a life together as father and "son," much to the confusion and dismay of Vincent's firefighting boys' club).

If that sounds jarringly erratic and surreal, it is — and more so than my summary suggests. But that's not why I find Titane so difficult. I love unpredictable narratives, and I love it when ambitious directors take big swings. What matters to me most is meaningfulness. You can learn a lot about an artist by where and how they invest their time and attention. You can learn a lot about a movie by asking what it loves with its resources, its camera, its energy.

What does Titane love? Although the arc of the story might suggest it loves the dangerously unhinged Alexia and the poor broken-hearted Vincent, aiming to bring them together into a healing experience of love and trust, the absurdity of their desperate decisions makes it impossible — for this moviegoer, anyway — to take either of them seriously. And, worse, it shows them incapable of forming a bond that might bring actual healing, as reliant as it is on lies, delusions, and denial.

So why has Titane charmed the Cannes jury? Does it do anything particularly new?

Like a loud, rattling, unsteady automobile pieced together with parts of luxury cars, Titane is a marathon of allusions and references that has me wishing I was watching those other films — any of them — whenever they come to mind. As many critics have observed, Titane welds together the central conceit of Cronenberg's lurid Crash and some truly imaginative twists from Leo Carax's spectacularly strange Holy Motors. But I'm also reminded of the kamikaze, hell-for-leather energy of Noomi Rapace's Lisbeth Salander in Niels Arden Oplev's The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo; the tragic co-dependent bond between vampire and aging familiar in Let the Right One In; the sentient, serial-killing car tire in Rubber; the mysterious charity of a grieving father in the Dardennes' Le Fils; and the carnage-slinging relentlessness of Uma Thurman's "The Bride" in Kill Bill (particularly Volume 2, from which Titane steals a key needle drop). And then, in its climactic moments, I can't help but think about an unforgettable sequence from a film too recent to have been an inspiration: Nikole Beckwith's Together Together.

Having said all of this, I'm tempted to reconsider my review. I mean, any movie that creates a compelling collage of such a wild array of movies is certainly a freakshow worth seeing... right?

Not for me. I have no desire to return to Titane ever again. I mean, maybe the Cannes jury was like, "Welp, so many technical aspects of this film are achieved with excellence that we really have no choice but to give it the Palme d'Or." And yes, Ducournau demonstrates remarkable skill with staging crowded and complicated scenes, as well as an imagination for startling juxtapositions that keep us guessing about what's around the corner. She's also good with actors. For all of the spectacular color, light, and energy onscreen, there's nothing more visually compelling than Vincent Lindon's commanding physical presence.

But is the whole of Titane greater than the sum of its chrome-and-steel-and-multilated-body parts?

This is a film that has a very specific audacity that I do not understand. I'll be the first to admit that, while I understand the importance of stories that imaginatively challenge our traditional definitions of gender and sexual orientation, I cannot figure out how a story like this would come as any comfort to those who have suffered in their search for love, family, and societal acceptance. Titane seems to think we will care about Alexia and Vincent even as their tentative and discomforting agreements and contracts take them to greater extremes of self-deceit and a refusal to reckon with the destruction they are wreaking in the world. Instead of summoning from its audience a sense of empathy, it glorifies a sort of anti-humanity, dismissing as collateral damage several victims of brutal murders, and celebrating the allure of a lie over the fact that the truth can set us free.

I've asked myself if I might be misreading it all. Could this be a cautionary tale about how, if we are scarred deeply enough, we might easily be persuaded to embrace lies for the sake of comfort and thus invite new forms of corruption into the world? I suppose that someone could read Titane's bonkers conclusion that way. But I can't shake the sense that the movie wants us to root for Vincent and Alexia, and to welcome the new beginning in its final frames as the dawning of a new post-human era. Self-annihilation, it suggests, may be humankind's only acceptable option.

And besides, all along the way, scenarios in which human beings are making self-destructive choices are filmed with a sense of revelry. Alexia's exotic dancing is filmed with lusty enthusiasm, Ducournau making no effort to avoid filming Alexia and the other dancers with the lascivious gaze of the lust-driven men staggering like zombies through the explicit exhibition.

Thus, it feels disingenuous when Ducournau tries to make a victim of Alexia later. When one of Alexia's drooling worshippers dives in for an unwanted kiss, Ducournau celebrates his mistake by subjecting him to an excruciating execution, one of several that are staged in ways that suggest she's with those misguided moviegoers who seek out and revel in particularly perverse varieties of big-screen bloodshed. Sure, the stalker's a creep. But Alexia's wild response — to pluck the knitting needle and plunge it into his ear, like like an evil Buffy staking bloody claims on an unremarkable vampire — is so extreme that any moviegoer with a conscience is going to be rooting for her to be caught and locked up as soon as possible.

As the story unfolds — or, better, goes on breaking down in so many ways — we're asked to accept, and even enjoy, how Alexia turns against her girlfriend Justine when her appetite for metal isn't immediately understood and endorsed. This leads to an all-out slaughter that I can't imagine the most bloodthirsty Tarantino fan justifying, and it's played for laughs.

I'd be curious to know what trans moviegoers think of Titane, but I can't imagine any of my trans friends watching this and saying "This movie gets me." (In this regard, I find Jude Dry's indieWire review enlightening.) If anything, I'd suspect that they would be distraught over how this movie makes the prospect of transitioning seem like a decision motivated by fear or insanity. Titane feels so hell-bent on troubling us with its relentlessly lurid assaults — “You think that’s disturbing… wait’ll you see this!” — that it’s culminating episodes, which illustrate The Guilty’s rubber-stamp platitude of “Broken people save broken people” seem disingenuous and smug.

Afterward, I felt like Hayao Miyazaki after he watched digital animation of mutant humans: "Utterly disgusted," he called what he had seen "an insult to life itself."

Sunday Song: Von Bieker and Knathan Ryan sing their quarantine longings

I'm thinking about places I miss: Santa Fe, New Mexico. Vancouver, B.C. The trails around Macdonald and Flathead Lake in Montana. Concerts at The Triple Door in downtown Seattle.

Is there a place you've been longing for that you haven't been able to visit during the pandemic?

I'm thinking about the people whose company has made these long months of isolation more bearable: Anne, who has stayed with me for 25 years (our silver anniversary is October 5). Our friends Kirk and Kirstin — the "bubble couple" with whom we've enjoyed meals, streaming concerts, and encouraging conversation. My colleague Dr. Traynor Hansen, who was one of the only humans I saw regularly on SPU's campus during the year of online teaching.

Is there a person who has helped keep you sane as we've grown accustomed to heavy limitations on our lives?

The complications introduced by COVID-19 have complicated my own creative life in myriad ways. I miss the places where I know I can go and experience creative inspiration, where I can lose myself in imagination and art. But I am grateful for those artists who have found ways to be meaningfully productive during the last year. And if their work resonates with expressions of struggle and hope that ring true during lockdown, all the better.

For two singer songwriters I've been listening to this week, it's been a time to lean into gratitude — gratitude for the places they long to be, gratitude for the women they love who share these quarantine spaces with them.

Dave Von Bieker's new solo album Long For This World opens with "Places We Can't Live," a track that has me remembering U2's "Where The Streets Have No Name." It doesn't sound like that song — Von Bieker's pop style is more intimate — but the soulful lyrics will have you thinking about those places in the world you find yourself longing to go, those places that tune the instruments of your spirit.

And I know Dave Von Bieker well enough to know that we have similar lists of favorite places. So this record speaks to me directly. Von Bieker has grown as a songwriter in a community of creatives called The Glen Workshop, hosted by Image journal, over the last decade, just as I have grown as a writer, teacher, and speaker there. There's something about the light, the color, the weather, and the culture of Santa Fe, New Mexico, and there is something special about the community of art and faith that Image has cultivated. I hear references to the The Glen Workshop throughout the album.

Here's what Von Bieker's website says about the song:

All of us have places we love to visit, but will never call home. These places may be exotic, wild and beautiful, but resistant to our roots. Von Bieker’s heart is spread among such places – the cool sandy shores of Vancouver and the stark high-desert of New Mexico. The deafening life of Manhattan and the graffitied walls of East Berlin. There are also smaller places – diners and bars that hold their appeal only so long as we visit just often enough. Lastly, there are emotional and spiritual places that we must visit to stay alive but would kill us if we stayed too long. Grief. Ecstasy. The valley and the mountain top. To live is to keep moving – always between these places we can’t live.

This song took on new resonance for Von Bieker during the Pandemic. Suddenly these places became impossible to visit except by memory, imagination and music.

https://youtu.be/noqxuHydaZg

Knathan Ryan, a Seattle singer-songwriter and bandleader I've been listening to for more than 20 years, has a new album — Where The End Begins — coming out on October 8 (just in time for me to listen on my birthday on the 9th).

And you'll hear more direct references to the pandemic in one of the first two singles he's sharing with the world at his Bandcamp site.

And you'll hear more direct references to the pandemic in one of the first two singles he's sharing with the world at his Bandcamp site.

The first one is called "Quarantine Queen," and you can hear the studio version on Bandcamp here.

About the song, Ryan says,

My daughter Flannery (age 12 at the time) and I were goofing off on the back porch. She plays the cello and had it across her lap like a bass guitar. I started strumming this here song and she started that wicked bass line. The song came together in a few minutes — a tribute to my Jessie who was putting up with all our asses indoors during quarantine.

He, too, seems to be longing for the places where he and his loved ones have known flourishing:

Do you remember, once upon a time? When we used to go,

Where we wanted to go on the outside?

Or was it just a dream, I don't seem to remember anything?

Was it just a dream, a beautiful dream?

And now I'm locked inside this ol' house —

day and night, day and night.

But I don't really seem to mind,

with you by my side, by my side.

Here's a live solo performance from May 2020:

https://youtu.be/stwBE3IbxGc

I can't wait to hear the whole record in a few weeks.

No Sudden Move (2021)

"This is going to be a punch."

The scene in which David Harbour looms, trembling, over his boss and delivers this line is one of those rare genre-movie moments in which I find myself wide awake, leaning forward, and loving the movies.

How many movies like this — populated with crooks on the streets, crooks in middle-class American families, crooks in the police force, and crooks as corporation heads, all chasing after money in a game of schemes and double-crosses — have we seen? Director Steven Soderbergh has made his fair share of them, from the stylish and sexy Out of Sight to the Oceans heist comedies (with their distinctive blent of glamour, smarts, and smart-assery). So it's a surprise and a delight to slip into the familiar murkiness of these moody color schemes, these moral quagmires, and find myself delighted by engaging characters, surprising scenarios, and inspired twists.

The less said about this story the better — there's a lot of pleasure to be found in connecting many mysterious dots. Suffice it to say that it's 1954, and Jones (Brendan Fraser doing his best best Orson Welles) — rounds up three accomplished crooks who sniff at each other like dogs that can't get along. There's Curt (Don Cheadle) who is fresh out of prison and well aware that he's marked for death; there's Ronald (Benicio Del Toro), a man of dubious judgment — which is immediately clear as we meet him having an affair with a mob boss's wife (Julia Fox); and then there's Charley (Keiran Culkin), an aggressive, violent wildcard who takes the lead in a job so full of secrets that everybody's nervous. They're tasked with holding hostage the family of Matt (David Harbour) until Matt retrieves an important document from the safe at his workplace. What is it? It'll be a while before we find out. And when we do, we see the truth dawning on the crooks that they've been drawn into deeper and more dangerous waters than they anticipated.

But the greatest pleasure of this, as with most Soderbergh films, is the technical execution. Unless you're allergic to the fish-eye-lens style — and it's been bothering a lot of people, so you might be — you'll savor the light, the colors, the effortless grace of the camera. I did, anyway. Soderbergh has always seized upon any kind of narrative as an excuse to dance, and man, he still has the moves. After the modest and quirky pleasures of Logan Lucky's heist hi-jinx, No Sudden Move is evidence that he's still capable of taking a strong script and making something masterful from it.

As usual, he seems to have a long line of Hollywood A-listers — aging veterans and fresher faces — eager to work with him, and, with smart casting by Carmen Cuba, he stirs up a spicy stew of stars. They find a cool, easygoing chemistry here, and the secret of their success is that nobody overreaches. ("Overreach," by the way, becomes a very important word in this film.) Every one of the big stars here dials it up to, oh, about 7 out of 10, and that keeps things from feeling too showy, too eager to please, too ambitious for awards. That carefully sustained tone gives the film a convincing cohesion. The ensemble is (with one exception) uniformly strong — Cheadle reveling in his meaty role (one of his greatest performances), Del Toro enjoying playing a fool who catches a few lucky breaks, Harbour leaning into his Desperate Harrison Ford voice, and Fraser making a major impression in what could have been a forgettable role. (He's better than ever. Glad to hear that Scorsese has given him a role in his next film.)

The only casting misstep comes late in the film. While it's clearly meant to be a sneaky surprise, it's also a doozy of a spell-breaker. (I think the last time a surprise appearance disrupted a film for me as severely as this came in the middle of Nolan's Interstellar.) I won't reveal who it is here, as you may find the choice inspired. But it knocked me sideways.

The storytelling stays strong all the way to the end, despite the stunt-casting stumble, bringing us to what strikes me as one of the more cynical conclusions I've seen in a long time. Brian Tallerico sums it up as "a story of men with ulterior motives, in which only the truly corrupt come out on top." Having said that, I have to admit that it also stings in its truthfulness. This is a picture a capitalism so corrupt that those at the top, like the almost-soulless restaurant millionaire in Michael Sarnoski's Pig, are well-aware of, and on some level disgusted with, their own miserable inhumanity, but they have no capacity for change. Everyone is compromising, and nobody sees a way out unless they're momentarily seduced by that fantasy that tells them to take the money and run.

And I think No Sudden Move, like a bottle of Scotch that retails for $88, and like the great Don Cheadle himself, is going to age well. I can imagine bumping this up a half-star on an other viewing. We'll see.

If you had to pick five movies that were "formational," what would they be?

If you were asked to name five films that have been influential in shaping your faith in some way, what five films would you choose?

I found this question extremely challenging, and the list I ended up sharing in this Renovaré. conversation, hosted by Carolyn Arends, might have been different if you'd asked me the next day, or even an hour later. But that's because — as this website demonstrates — there have been so many films that have influenced my faith.

I am thrilled to share this video of my conversation with film scholar Catherine Barsotti, Renovaré president Chris Hall, and show host Carolyn Arends. Enjoy! And then, if you'd like, post the titles of the five films you would have talked about.

https://youtu.be/GgI_EPNFFN8

Leo Carax's Annette sparks a conversation with "Catholic Cinephile" Evan Cogswell

In the latest episode of the podcast Looking Closer with Jeffrey Overstreet, "Catholic Cinephile" Evan Cogswell (visit his blog and read his reviews here) makes an argument that Annette is a great musical and, in fact, his favorite film of the year so far.

https://youtu.be/l_EaNpL16SU

I'm skeptical going in, but Cogswell makes some strong points.

Caution: We do talk about most of the movie, so you might want to watch the film on Amazon Prime and then come back to hear our conversation about it.

UPDATE: Since we recorded this, Cogswell has published a full review of the film at CatholicCinephile.com.

Quo vadis, Aida? (2021)

On Wednesday of this week, as the headlines were overwhelmed with news of America's withdrawal from Afghanistan, and as we all began to realize the brutality — especially against women and girls — that would quickly be unleashed across that country, I did what many of us did: In the interest of learning, I read until I felt sick and helpless. And then, obligations and responsibilities pulled me away, heavy hearted, back into my routine.

Later, weary and given an occasion to rest, I decided to distract my brain with a movie. And, well, I sure picked a hell of a day to check out Quo vadis, Aida?, the best-reviewed film released in the U.S. in 2021. Hell of a day? How about a hell of a month?! I don't know... maybe there hasn't been a "good moment" in the last five or six years for watching movies about events as horrifying as the genocide in Bosnia. How does it make any sense to give our attention to the dramatization of some other society's violent overthrow while we we are watching it happen right now, either elsewhere in the world or here, either swiftly or in slow motion?

Or, on the other hand, you could argue that this is the best time for us to watch Quo vadis, Aida? and open our imaginations to its characters.

That central question might sound very familiar. But although Quo vadis, Aida? is not as sweeping in its scope as Schindler's List, and though it lacks that film's conclusion contrived for emotional catharsis, this is for the Bosnian war what that landmark film is for the Holocaust. It just doesn't have names like Spielberg or Neeson or Fiennes to sell it — which is a shame, because as difficult as it is to take, it is an essential memorial and a reminder that, as Faulkner said, "The past is never dead. It’s not even past."

And all the way through, we are never allowed to forget the physicality of bodies being pressed into a warehouse like sheep being driven into the paths and pens that contain them for slaughter. This is a movie you can smell, and that ratchets up the suspense and the terror of it. This is the most harrowing thing I've seen since, what... Son of Saul, perhaps? Actually, that's a pretty good reference point, in that it's about an actual hell of human history revealed through the eyes of one character. As we follow this desperate soul through jarring errands and investigations (edited expertly by Jaroslaw Kaminski, who edited Ida), we learn the Kafka-esque geography of a maze of so-called "diplomacy" that has no evident escape.

In 1995, when the events depicted in this film took place, I had just graduated from college, and I had just lost the most significant relationship of my life so far. I felt as if the world had turned upside down on me. So I wasn't paying much attention to the news. If I had been, then news of this single-day slaughter of more than 8,000 Bosnian Muslims (mostly men and boys), and the subsequent rape of many women who were allowed to live, might have given me some sobering perspective.

I've read about this chapter of history since then, but the reality — the madness, the satanic hatefulness, the tactics clearly designed to imitate the murderous machinery of the Nazis — is a necessary subject for our attention, as even the most famously humane nations in the world can be so easily manipulated into carrying out horrors like this if the wrong people are given power. (The most difficult thing about my past few years as an American has been the discovery that many — perhaps most — American Christians would be easily duped into handing control of their country over to a fascist who, given the occasion, would slaughter populations without flinching. There are songs celebrating America I don't sing anymore, histories I was taught that I no longer believe, hopes I once had for America's future that now seem far from possible.)

As the end credits rolled, I found myself scrolling back through the film, searching for any glimmer of hope, any suggestion of a Holy Spirit hovering over these troubled waters. It is good to learn that General Ratko Mladić, the malevolent general who ordered the murders, is locked up for life, but my heart remains unconsoled. All I find is that groaning that the Scriptures describe, the lament of the Spirit that runs "too deep for words" — God's heart breaking as the gifts given to the God's children are sharpened into weapons of mass destruction. All I read in Aida's traumatized face is Christ's own echo of the Psalmist's despairing cry: "My God, why have you forsaken me?"

The title’s invocation of the Latin phrase “quo vadis?” (“Where are you going?”) — a reference to the apostle Peter’s flight from crucifixion in Rome — here feels like a moral inquiry, both sympathetic and reproachful, directed at Aida’s conscience. Her concern for her family above all else is an entirely human reaction, to be expected from anyone in her shoes. But even as it acknowledges this, the movie ... keeps feeding us sidelong glimpses of those for whom Aida can do nothing.

I wonder what this film will inspire in audiences. Will it just seem like a cautionary tale that we suffer and then go back to work? Me, I'm reminded to heed the vision of Sheriff Bell at the conclusion of No Country for Old Men: Our ultimate hope lies in the dreams and visions of prophets and poets. We can't stop the destruction already being wrought; we can't undo the accelerating decline of the planet's delicate balance that has made human life possible. So, you who are doomed to die beside me, one way or another, as the wages of humankind's sins catch up with us... what do you believe in?

May the promises of God — ultimate justice, boundless mercy — prove true.