Petite Maman (2022)

How can I inspire you to see Céline Sciamma's new film Petite Maman without spoiling it for you?

If you have children who can read subtitles, how can I convince you to spend the evening watching it as a family?

Chances are that if you've read anything about this quietly enchanting fantasy, or even seen a trailer, you already know its whimsical twist. But I hope not. I'm glad that I wandered into it without knowing anything except that it was an unusually short feature film and that it was by the director of the exquisitely tragic love story Portrait of a Lady on Fire (one of my ten favorite films of 2020). If you do know what's coming, well — it won't ruin the movie for you. In fact, having seen the whole thing, I am eager to see it again, confident I will enjoy it even more. But it's a rare occasion that a movie's revelations will inspire smiles of joy and wonder like this one does.

Petite Maman — which, if I have any reliable memories from my high-school French lessons, must mean "Little Mother" — follows young Nelly (Joséphine Sanz) and her mother Marion (Nina Meurisse) out into the woods to the house of the one they have recently lost: Nelly's grandmother, Marion's mother. In the haunted quiet of that house — one visited by gentle apparitions of reflected light that would have pleased Kieslowski — Nelly struggles to accept that she did not give her grandmother a proper goodbye. And Marion, who seems to be melancholy by nature and now must contend with deep grief, has things to work out as well.

What happens next is this enchanted forest, well — you will you will discover it all too easily from the movie's marketing if you're paying attention. (Try not to.) Suffice it to say that it's a rare kind of movie magic, achieved by very young actors without any digital animation or technical special effects. And their company is so delightful that you'll be likely to wish that movie was longer. Sciamma is a filmmaker who knows that less is more. No need to hit the two-hour mark unless it's absolutely necessary. This has all the weight of a full feature film, and it's a slight 72 minutes.

But for Sciamma, it isn't a small movie. Talking to film critic Carlos Aguilar at The Los Angeles Times, she said, "I don’t see Petite Maman as a modest film. The impact I want it to have is to give us a new mythology to understand ourselves and heal. ... Rather than just looking back and realize our parents were also kids, it’s a form of future perception of them. It’s about connecting, but about being reunited. That’s why it’s my dream for the film to be watched in a theater filled with adults and kids, because the film respects them both equally.”

[MAY 13, 2022 UPDATE: Having now seen it twice, I must echo Sciamma's hope. The film is so much more beautiful on a big screen, its silences so much stronger. If I were seeking to inspire in children a love of cinema, this is one of the first films I would take them to see. And I would be fascinated to ask them what they thought of it afterwards.]

This modest, intimate, magical story may seem like quite a surprising turn for Sciamma, whose Lumière award-winning Girlhood was such a starkly realistic portrait of adolescence, and whose Cannes award-winning Portrait of a Lady on Fire was so wise and so meaningfully erotic. But one remarkable quality they all share is a patient and hopeful attentiveness to suffering.

As I watched it, I was vividly reminded of two very special films: Jacques Doillon's Ponette and John Sayles's The Secret of Roan Inish. The films share some unusual strengths: In all three, we follow observant and intelligent children through territory scarred with loss and sadness. In all three, the film's delicate fairy-tale tone must be inspired and sustained by talented child actors. In all three those actors are convincing — they seem entirely unaware of the cameras and entirely convinced of their narrative circumstances. And in all three, we find a similar spirit of tenderness.

But — as more than one friend of mine has observed — there's more than a little My Neighbor Totoro in the mix here, too. (Sciamma herself agrees, according to that Los Angeles Times piece.) Don't get the wrong idea — this movie doesn't need big, fuzzy, huggable trolls or flying cats. It has all of the magic it needs in sisters Joséphine and Gabrielle Sanz, who strike a powerfully authentic tone of playful kinship, saving the film from a high risk of sentimentality, and inspiring our suspension of disbelief. (Disbe-grief?)

2022 has been a year full of movies about mothers and daughters: In both Everything Everywhere All at Once and Turning Red, the mothers need enlightenment and their daughters must become exasperated and dangerous in order to smack them out of their ignorance. Both films, though they have their strengths, seem compelled to reach a frantic pace, as if that's what it takes to entertain audiences. What that costs the audience is a chance to be drawn in, to have visual and aural space in which to contemplate. And watching Petite Maman, we have the opportunity to reflect, to ask questions, to imagine possibilities and implications. Above all, we have the chance to empathize. By Ebert's famous definition, "A movie is a machine that generates empathy." And that makes this, far more than either of the other major mother/daughter films of the year, a great movie.

And so, with great respect for the joy of discovering this film, I will let this be the extent of my review. I want your experience with this film to be full of surprises. It's so gentle, so full of admirable restraint, so radiant with childlike curiosity, I feel unusually motivated to preserve its subtle pleasures for you without any hints in advance.

I'll give the last words here to my friend and my favorite film critic: Steven D. Greydanus. He calls Petite Maman an "exquisite little film" and recommends it "for all ages." At Catholic World Report, he writes,

Not long ago ... I remarked on my abiding love of time travel for its power to speak to deep human longings to undo past wrongs and heal incurable wounds: to offer, in a word, an imaginative picture of redemption beyond anything we experience in the ordinary flow of time. There’s no place in a film like Petite Maman for world-bending sorcery or flux capacitors, but the elegant simplicity of what Sciamma does with an unexplained wrinkle in the fabric of reality speaks as eloquently to those longings as any film I’ve seen.

The Northman (2022)

[CAUTION: There are some very general, spoiler-ish observations in this review that concern its closing scenes and the relationship between those scenes and the endings of Robert Eggers' previous films The Witch and The Lighthouse.]

It's kind of amazing how many films I've seen built upon the Inigo Montoya mantra. (Let's say it together: "You killed my father. Prepare to die.") It's even more amazing how fundamental that storyline is, considering the fact that I have never met a single human being whose father has been murdered by a traitorous acquaintance. Nor have I ever met anyone who had an opportunity to go on a revenge quest.

And yet, just this morning, in conversation with a wise counselor, what was I wrestling with? I was tending to some wounds that I suffered as a young boy during a season of my father's unemployment. At the time, I believed — passionately — that teachers and school administrators had wickedly conspired against him top end his job as a teacher. I remember feelings of rage, helplessness, and humiliation over the idea that anyone could take power away from my parents in ways that would make them suffer hardship.

That was only the beginning. There was a lot that I know now that I did not understand then. I had a lot of growing up to do.

Thus, even though I am weary of revenge narratives, I feel some measure of understanding and sympathy for the deeply wounded young hero of Robert Eggers's new film The Northman. He too, as a young boy, witnesses his father "removal" from a place of power and influence. He too suffers emotional trauma and lets his fury harden into resentment that becomes a controlling factor in his life.

And he too has a lot to learn in the process of growing up.

But is he willing to learn?

Revenge is foolishness. But that doesn't mean that stories about it are worthless. Sure, there is an epidemic in American entertainment of stories that glorify revenge — and that's a toxic trend. But tales of vengeance can follow a righteously angry hero to so many possible conclusions: not only a violent reckoning or ruin, but also grace, forgiveness, reconciliation.

I love Lee Isaac Chung's film Munyurangabo, which I saw a whole decade before he made the Oscar-winning Minari. It's a powerful story of a revenge quest that leads its angry and heartbroken antihero to a surprising turn. It's a surprising story that finds hope at the end of a journey that began in trauma and wrath.

Such stories are very rare throughout human history. But even if revenge tales end in the achievement of violence, they can become meaningful tragedies. In choosing violence over long-suffering and love, an antihero can illustrate the wages of sin and provide us with a cautionary tale. Consider Hamlet: the choice to answer killing with killing leads to greater consequences for everyone.

I've always found the prevalence of such violence in mythology interesting — Celtic tales, Greek myths, whatever the origin — for how it illustrates the values and beliefs of particular peoples, places, and times. I first learned about the Norse god Vidar, also known as "The Silent God" and "the God of Revenge," while paying very little attention during a boring college class on mythology. You want Vidar on your side if you're on a revenge quest. After all, according to his origin story, Vidar knows the territory: Wreaking vengeance, he tore apart Fenrir, the wolf who had killed his own literal god-father: Odin.

But why is Vidar described as a god of silence and revenge? The combination struck me as curious. Was Vidar silent because silence is an essential talent for someone who is determined to sneak up on a dangerous tyrant and kill him? That makes sense — especially if the villain might be anticipating such retaliation. Could it also be that a god of revenge is violent precisely because he is silent about his anger?

Bottle up hard feelings and you'll end up with a volcanic eruption. That's some heavy wisdom — I've learned it from watching others in my family and community. I've learned it in my own experience.

Nevertheless, I have no doubt that contemporary revenge narratives influence a culture that has such a huge appetite for them. The increasing violence in American culture wars seems to me to be influenced by these stories. Make an audience angry enough, and they will cheer for all manner of violence. And that includes Christian audiences, as evidenced by the popularity of Braveheart among evangelical Christians, and their increasing support for violent uprisings against their culture-war enemies (even though such uprisings are obviously contrary to Jesus's own teachings).

So, I had good reason to approach Eggers's new movie with skepticism. Reading about the basic narrative arc of The Northman, I became nervous that this might become just a fancier, more enthralling version of the kind of narrative that Quentin Tarantino consistently serves up: a lurid feast appealing to an audience's bloodlust.

And, even more worrying than that — a Nordic revenge story? Right now? A story about clans of white people warring like animals in an endless cycle of violence and retaliation... making speeches about defending their bloodlines? Doesn't that sound like the glorification of what's going on all around us in the world right now and threatening not only our hopes for peace and justice but even our hopes of an inhabitable planet for future generations?

On the other hand, my history with Robert Eggers's filmography so far gave me some measure of optimism.

I admire his two previous films The Witch (2015) and The Lighthouse (2020). Both tell stories of characters who remove themselves from the "trouble" of society (as if that will help). The efforts of those characters fail — as they distance themselves from some sources of trouble, they learn the hard way that they have brought plenty of trouble with them into their isolation. Now, suffering in remote places, they have no community to rely on for help. Even more troubling, both films depict their doomed protagonists devolving into a kind of ecstatic madness, a victory that I don't believe audiences are meant to believe in or celebrate. I think we're supposed to recoil at their choices and at the frightful consequences. I interpret both as cautionary tales — or, better, cautionary nightmares — about how our impulses can lead us straight to hell. And I think we are shown that, just the Satan of Milton's Paradise Lost determines to "make a heaven of hell," so these characters fail to discern the gravity of their error, thinking they have somehow triumphed.

What's more, I think Eggers's filmmaking powers are formidable. While both stories strike me as meaningful and worth studying, The Witch and The Lighthouse also look and sound extraordinary, their exquisite aesthetics conjuring a powerful sense of spiritual darkness, their scripts composed with a richly literary complexity, the lines delivered by actors who have mastered difficult dialects.

So... which is it?

Is The Northman a cautionary tale? A corrective to vengeful impulses?

Or is it just another Braveheart, justifying vengeful violence in the name of some kind of god, throwing fuel on the fire of the violent fantasies of the "culture warriors" who threaten democracy?

As it turns out, both my fears and my second-guessing of this film were well founded.

For many moviegoers — perhaps most — The Northman will play like a darker, bloodier version of Gladiator, in which the audience roots for a suffering hero. He never quite says it, but the mantra is there all the same. He might have said "My name is Prince Amleth. You, Fjölnir The Brotherless, killed my father, King Aruvandil War-Raven. Prepare to die." Instead, he says, "I will avenge you, Father. I will save you, Mother. I will kill you, Fjolnir.”

We watch Amleth (Alexander Skarsgård) gird up his loins and sharpen his lances to carry out violent vengeance against a tyrant (Claes Bang) who took the throne of his father (Ethan Hawke) by treachery, and also made the queen Gudrún (Nicole Kidman) his own by force.

Sound awfully familiar? It should.

The Northman is basically the ur-Hamlet, a version of classic story that pre-dates any of Shakespeare's concerns about Ophelia or the role of the Players in "catching the conscience of the king." This is the most fundamental of revenge quests. This Amleth doesn't care about wordplay. He devotes his life to the long game of stealth and vengeance, his intent easy readable in the creases of his forehead and the scowl of his posture. Amleth gets a decade-long training in Viking masculinity, complete with fireside dances and chants, hand-to-hand combat, costumes of animal skins, communion with wolves and with witchcraft (including a Seeress played by none other than the great sorceress of pop music: Bjork!), and with a sort of Crossfit program that involves a lot of rowing. It's easy to root for him... at first.

But there is a strange contradiction at the movie's heart — manifested in the character of Olga (Anya Taylor-Joy). Amleth and Olga form a tenuous bond of mutual support as they earn their way up the chain of slavery to Fjölnir The Brotherless, until they find themselves in Iceland — Fjölnir has been driven out of his own kingdom and forced to settle elsewhere — at the edge of Fjölnir's inner circle and family.

When they get there, Amleth is troubled to discover that the story he has told himself throughout his life has been a false narrative. Fake News. Those events that traumatized him in childhood, they weren't as simple as he'd imagined. It wasn't just a case of the Evil World committing sins against a Saint.

It's always more complicated than that. To learn such lessons is fundamental to the work of Growing Up.

Olga, the tender and beautiful slave who sees Amleth's hardship so clearly, becomes a beacon of wisdom and hope in his life. It's seems only right that she's played by Anya Taylor-Joy, the actress who has, in my opinion, eyes that seem to have been custom made for the camera's attention (yea, more than the eyes of any actor living or dead). Her tremendous, shining eyes give Olga a sense of seeing so much more than Amleth's narrow and bloodshot eyes ever could. She eventually comes to see a hope for the two of them to break away from the path of violence and find a more meaningful and rewarding life somewhere else.

She wants to set Amleth free from the dangers of clinging to the source of his wrath, that false narrative he has believed, that false narrative that he might now see clearly and overcome.

Here is an opportunity to show audiences something so much more than — so much better than — the bloody revenge for which so many of them seem to have an insatiable appetite.

There is already plenty here to admire. Everything from the costumes to the sets — which often remind of me of Terrence Malick's work in The New World — are immersive and awe-inspiring. Eggers always knows where to put the camera. And the cast, as in every Eggers film, seems caught up in a fit of inspiration and chemistry, with one possible exception. I'm not sure I find Alexander Skarsgård to be the strongest choice for this role — he still seems more of a Movie Star than an immersive actor. He never surprises me here. Nicole Kidman, on the other hand, is terrifying and fearless in The Northman. I find the price of admission more than rewarded just for the spectacle of her fully committed performance. (I have to admit, though, that I half-expected her to break the fourth wall during a bloody battle scene and say, as she does in that awful AMC promo video, "Heartbreak feels good in a place like this.")

If I can trust my first experience with the film, I think Olga becomes the movie's conscience. We embrace Amleth's doubts, his momentary fear that he might not have any moral high ground to stand on here, as he waves his sword around and challenges his foe. Will Amleth choose to reject the wiser, more complicated understanding of what was really happening in his youth? Will he hold to his original emotional response, as reasonable as it might have been once upon a time, even though he now has a chance to see that it was childish, and that it will only lead to more bloodshed and folly?

I think we are supposed to side with Olga in her appeal to dissuade Amleth from his quest. I have a hard time believing that Eggers us to side with Amleth in abandoning a future with his family in favor of the glory of a battle to the death. I think Eggers wants us to see that this is an old, old story, and that today we can be enlightened enough to glimpse a brighter path.

But I could be wrong about this.

So much depends upon how we interpret the film's closing moments — which I won't spoil here. They complicate matters significantly, and give those who disagree with me their best evidence.Several of the critics I trust the most are upset about this movie, making strong arguments that it is not only disappointing but dangerous. I completely respect these arguments.

So, rather than claim I have "the right reading" of this film, I'm inclined to borrow an expression from Winston Churchill (who was speaking about Russia, not Hamlet, when he said them): Eggers' film is "a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma." It's going to get people talking.

But at this point, I do have a different interpretation of the film — particularly because I can't stop thinking about Eggers's two previous films. Both The Witch and The Lighthouse give us central characters who "turn to the Dark Side," so to speak. In their minds and by their chosen values, they triumph — sure. But they do so at the cost of their own souls. At the cost of their souls.

I am inclined to argue — only every so slightly, and I'm wide open to being persuaded otherwise — that The Northman is right in step with those films. I believe that Amleth is a tragic figure, one who is deluded into thinking he has triumphed, but from whom we must keep a skeptical distance, refusing to celebrate him as triumphant, horrified by what has become of him and what will probably likely become of his family. His self-affirming vision at the end is not unlike the ecstatic ascension of the young woman possessed at the conclusion of The Witch.

In the film's fiery volcano finale, I couldn't help but hear the distant echo of Young Obi-Wan's cry: "You were the chosen one!" Yeah, Amleth might've been, if he'd listened. The most heroic figure I know had a singular response to unfathomable evil, and in his response I find hope for an ultimate deliverance. After all, once you have started down the Dark Path, if you don't seize upon the moments of grace that are offered you, well... as the little green guru says, "forever will it dominate your destiny."

I prefer the Shakespeare version of this story, for the record. It gives us a clearer vision of wisdom and folly. And its truth can set us free.

But I think Eggers' version will stick with me. Amleth's dawning realizations about all that he misunderstood in childhood — these resonate with me. Some of the work I am doing now is learning to accept revelations about my childhood that were a long time coming. In a sense, it's yet another injury, another realization of betrayal. It wasn't a case of my family being "the Good Guys" and the world around us being "The Bad Guys." The impulse to draw lines in such a binary fashion is understandable when someone is hurt, but it's also childish, and it can cause us to take a bad situation and make it far, far worse. I look back at many years of speaking with contempt for those who I believed to be antagonistic toward my family. I look back at the stories I believed, the stories I told myself, and how they hardened into fury and resentment that have probably burned years away from the potential span of my life. The truth is setting me free — but not before the lies (some of which have been self-inflicted) have done a world of damage.

I'm grateful for storytellers who have helped me see the cost of vengeful impulses. I'm grateful for the Gospel's vision of a braver response that can lead to help and healing. Thus, I've broken away from the masses that cheer for the fulfillment of revenge quests. Stories of violent heroism always seem like tragedies to me. Violence is cyclical, after all: If you respond to violence with violence, all you're doing is perpetuating violence in a way that all but guarantees it will continue. Instead of going all Braveheart and raising a weapon in a roaring challenge, Christ receives his enemies' violence with open arms, suffers it, and refuses to let it remain in the world. In canceling violence, he saves us from sins. That is the kind of courage and character I find worth celebrating.

Amleth is too blinded by rage, and by a perverse cultural milieu of what we now call "toxic masculinity," to see the better path. And that is why his story is such a tragedy. Hopefully it will be received by audiences for what I believe it is: a memorable, harrowing, cautionary nightmare.

Weekender: Allison Russell, Philip Yancey, and Enchanted Journey II: Ex-vangelical Boogaloo

When I was in 6th grade, I played Evangelist the Narrator in a musical stage adaptation of Pilgrim's Progress. If I remember clearly what became a famous family story, I was sick in bed with a terrible fever, but I was determined that "the show must go on," so I went to school and survived the play, then collapsed in a sweat in the front row.

I haven't thought of that story for a long time.

But it came up in an unexpected place this week... on one of my favorite podcasts.

You'll find the evidence in this week's return to the Looking Closer ritual of "The Weekender" — a catch-all post of highlights from my past week.

Apparently, a lot of my closest friends are "Veterans of Culture Wars"

In one of the most surreal twists of my recent experience, one of my favorite podcasts — Veterans of Culture Wars, with Zach Malm and Dave Lester — posted back-to-back episodes featuring two of the friends who have influence and inspired me most:

- Special guest Special guest Alissa Wilkinson.

I got to know Alissa online before we met in person. We were publishing film reviews in some of the same places and exchanged notes about films. We eventually met in-person for the first time (if I recall correctly) at the Glen Workshop — we've both led seminars there several times — and she's the one who (in a cruel irony) introduced me for a film-focused lecture at the International Arts Movement (when it really should have been the other way around). She also stepped in to revise and revolutionize Christianity Today's film coverage after my long tenure there as the "Film Forum" columnist and a member of their review team. Today, she's showing everyone how it's done as the film critic for Vox.com, and her brand new book Salty is winning rave reviews. Alissa earned her master's in creative writing (creative nonfiction, with the same mentors who taught me in the program) at Seattle Pacific University.

- Special guest Jon Smart.

You've got to hear this conversation. It's a fascinating exploration of faith: the honest-to-goodness life of faith, which is an ongoing challenge of struggle and doubt and change as we wrestle with ongoing revelations, not the unimaginative, legalistic, judgmental charade of "certainty" that passes for cultural Christianity.

Jon is a fellow I’ve known since 6th Grade at Portland Christian Elementary School, studied with, played basketball with, and acted in plays with — including a spoof of "Cinderella" which I wrote and directed, and in which he played the Fairy Godfather, and a musical version of Pilgrim's Progress called Enchanted Journey, in which I was the narrator called Evangelist and Jon was Pilgrim's best friend — the aptly named Faithful. During our senior year of high school, Jon would became one of my closest friends and fellow enthusiast for the music of Bob Dylan and Bruce Cockburn. Jon was the Best Man when Anne and I were married in 1996. And, as I was glad to discover last year, he's still one of the best road-tripping companions I could ask for. (I was hiking with Anne and Jon back in 1995 when I first had the inspiration to write Auralia's Colors.) So, when the VCW podcast’s scheduled guest canceled, they decided to do "an experiment" and invited a listener to volunteer as their next guest. They gave the spot to Jon.

And I love this episode. It reminds me of the kinds of challenging and enlightening conversations I've had with Jon for decades.

Who’s next? Will the next VoCW visitor be a friend of mine too?

What I think about whenever I see "evangelicals" complaining about "CRT" (a concept they can rarely define with any accuracy)

The Gospel is good news for the oppressed and the enslaved.

The Gospel was the basis and inspiration of the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King as he preached salvation and spoke out against America’s ongoing history of racism and violence, legacies of hate that directly contradict Jesus’s teachings.

Thus, when Republicans and "evangelicals" falsely label such truth-telling as “CRT” and campaign to criminalize it, they are actively opposing the redemptive advancement of God’s Truth in the world.

And God is paying attention.

The antiChrist agendas of so many Americans, including so many professing evangelicals, can sometimes drag me to the edge of despair. It's relentlessly discouraging to see so many of the professing Christians who taught me to love Jesus so flagrantly and consistently contradicting those teachings in the name of fear, white supremacy, and Christian nationalism.

But Easter reminds me that Christ is already victorious over these lies and liars. And in the Big Picture, those who suffer the harms of such campaigns will be lifted up and revealed as Christ’s beloved. No amount of political corruption or hate-driven propaganda can change that.

Philip Yancey's award-acceptance speech at Wheaton are well worth reading

It's harder and harder to find American Christians who identify as "evangelicals" advancing anything that resembles the Gospel.

But Philip Yancey has been a reliable voice of wisdom for me since high school.

He was just honored with Wheaton's Alumnus of the Year award, and his acceptance speech has some highlights worth reading.

Here's an excerpt:

President George W. Bush used to talk about an axis of evil. I grew up in an axis of fundamentalist insanity. But I found an axis of evangelical sanity—people like Wheaton, Intervarsity, Billy Graham ’43 Litt.D. ’56, John Stott, Fuller Seminary. And Wheaton, we need you in these divisive times. The word “evangelical” is increasingly becoming a bad word. But it’s one I still cling to. I was with Walter Kim, of Korean descent, who’s head of the National Association of Evangelicals. He had just returned from a conference. I think there were 70 countries involved and only one person was invited from each country, so only one American among the 70. They ganged up on Kim and said, “We understand ‘evangelical’ is a bad word in the United States. Well, it’s not where I live. When you say that word in so many countries, it brings to mind clinics and hospitals and people fighting sex trafficking and orphanages and educational institutions. You can trash the word if you want to, but we’re keeping it because it means good news.”

Here in the United States, we’re so media-driven. Mostly that word has a political connotation. It’s a lens. It’s an either-or: Which side are you on? The center in divisive times is so hard to hold. When you build a bridge, you get walked on from both sides, as people at Wheaton know.

We need not an either-or faith; we need a both-and faith. John said that Jesus came full of grace and truth. A lot of people work hard in the truth department. Some people work hard in the grace department. Few people I know work hard in both. We need people who combine unity and diversity, as Jesus taught us. Evangelicals haven’t done that very well, historically. We need someone to show us the importance of both action and contemplation, the importance of this life, and also the importance of the next life, in a floundering culture that keeps widening the gulf between them.

Linford Detweiler shares a prayer composed by Teilhard de Chardin

"Patient Trust," a poem by Teilhard de Chardin, is a prayer I should memorize.

It's included in an extraordinary collection of prayers called Hearts on Fire: Praying with Jesuits. I have a copy that I carry with me everywhere. And yet, when I stumbled across it on Facebook this week, it stopped me in my tracks.

I'm so glad that Linford Detweiler brought it back into my life.

Allison Russell's TED Talk is here

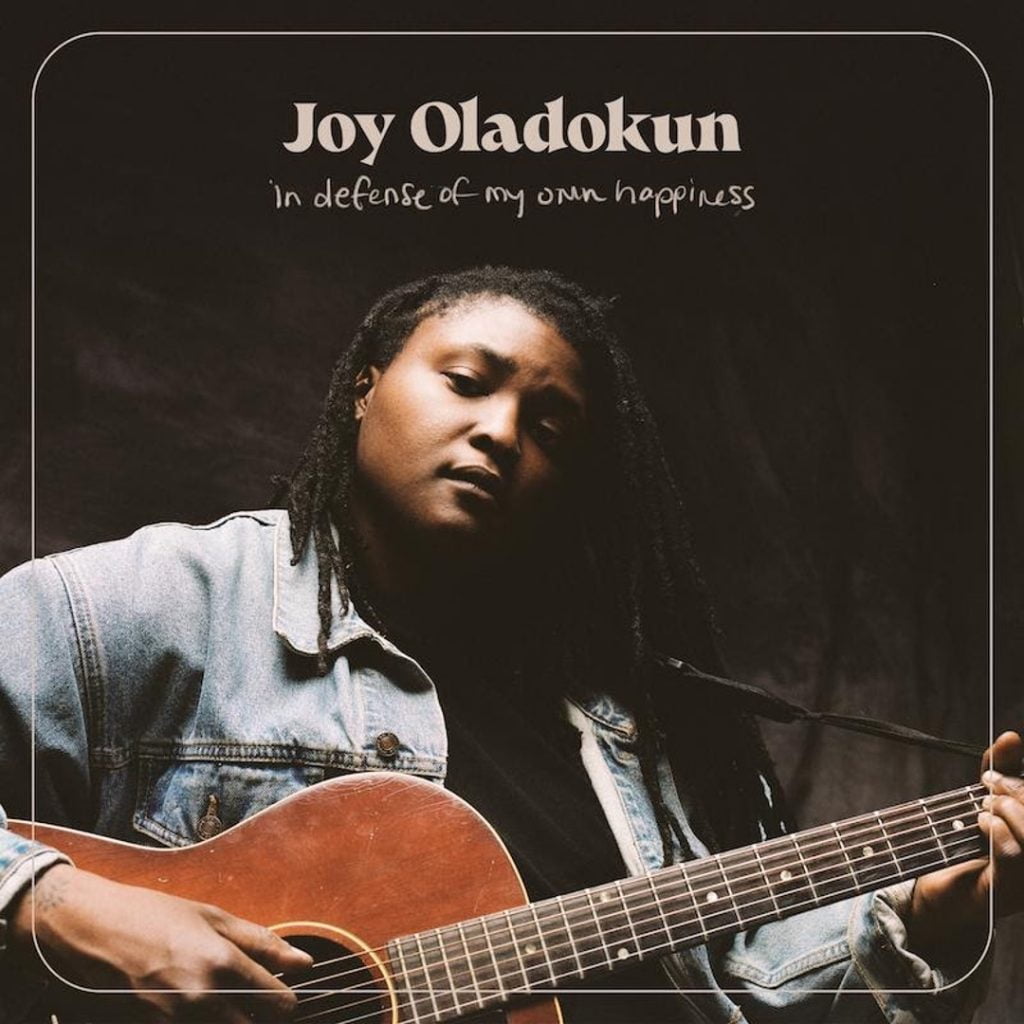

Allison Russell recorded my favorite album of 2021 and put on my favorite concert of 2021.

Now, she's done a TED Talk.

Memoria (2022)

Earlier this week, as I was walking across Seattle Pacific University's campus, another professor stepped away from a huddle of students and shouted my name. When I turned, he made a megaphone of his hands and roared, "Have you seen it yet?"

I know this professor well enough that I knew exactly what movie he meant. "Yes!" I shouted back.

"Isn't it great?" He opened his arms as if he were asking about the weather.

"It's...." I hesitated. I didn't want to disappoint him. "It's... something!"

"Not just my favorite movie of the year," he shouted for all the world to hear. "It's my favorite movie of all time!"

Don't you love that feeling — when you love something so much you cannot wait to celebrate it with the whole world? It's a rare experience for me. And no, I don't feel that way about Everything Everywhere All of the Time (although I enjoyed the movie). But I have felt that way three times in 2022 already, about three very different movies.

The good news for my colleague is that Everything Everywhere is playing, for the moment, at several theaters around Seattle. Moviegoers have a good chance of seeing it on a big screen. The bad news for me is that it's already too late for almost all of you to see any of the three films I'm excited about the way it was meant to be seen: in a dark theater, with a crowd of people, on a big screen.

Alexandre Koberidze's playful magical-realism romance with the Georgian town of Kutaisi, titled What Do We See When We Look At the Sky?, is a sprawling, meandering journey of discovery. It's a movie to live in and explore at a leisurely pace for several hours. But I've had no chance to see it on the big screen, and at this point you won't either. (At the moment, it's streaming on MUBI and it's rentable on Apple TV and Amazon.)

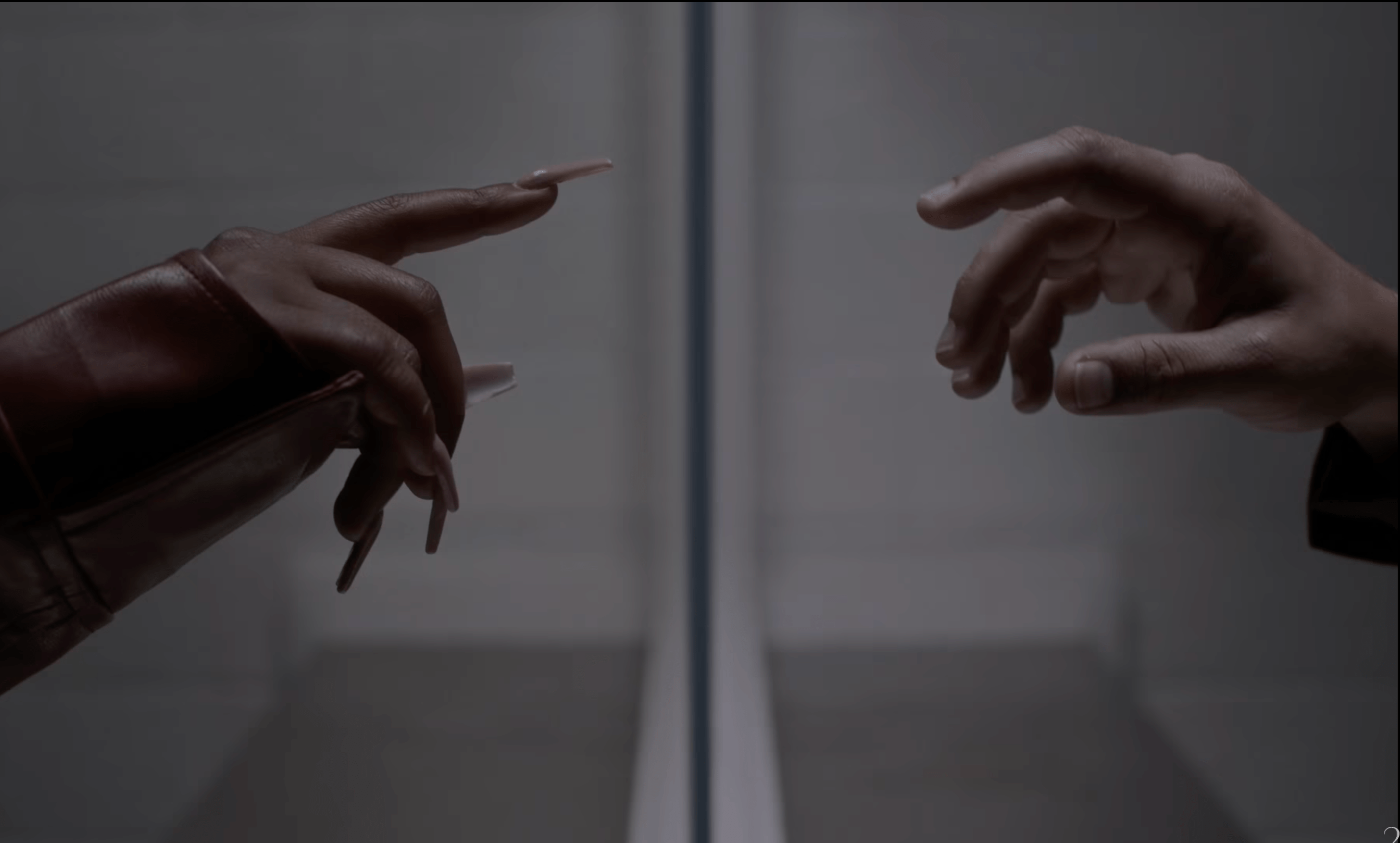

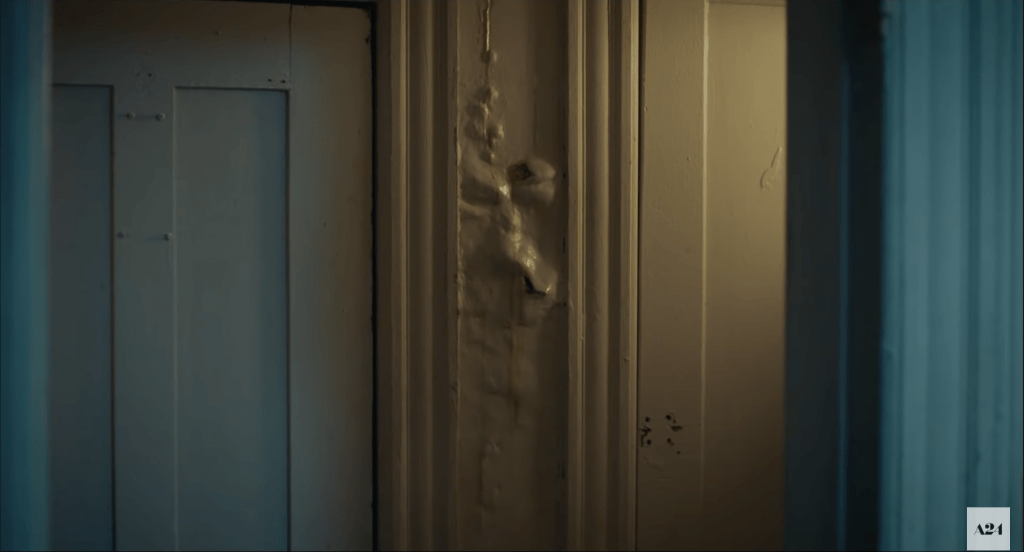

After Yang, Kogonada's much-anticipated sci-fi meditation on memory and grief, fulfills the promise of his first feature film Columbus, drawing out Colin Farrell's best performance since The New World. But After Yang never played on Seattle big screens — which is a great loss for Seattle moviegoers. (Thanks for nothing, A24.) I had to organize a big-screen experience of my own — and now its exquisite imagery will probably be discovered by most audiences on screens far too small to do Kogonada's beautiful work any justice.

But the most frustrating situation of all is this one:

The latest film from writer-director Apichatpong Weerasethakul, who has made some of the most exquisitely enchanting and unsettling films I've ever seen — Syndromes and a Century and Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives, for example — is quite unlike any theatrical experience I've had before. Memoria is meant to surround you with shifting soundscapes of weather, radio signals, far more mysterious noises, and silences that seem more like living presences than quiet.

Since you're unlikely to get to see Memoria anytime soon, be cautioned: I'm going to go into detail describing the story, and that may spoil some of the surprise factor. But I'll keep the film's best secrets to myself, as I sincerely hope you'll get to experience it someday.

By immersing you in its otherworldliness, Memoria draws you into the experience of its troubled protagonist: Jessica, an orchidologist living in Medellín, Columbia, who, like Julie in Krzysztof Kieslowski's Three Colors: Blue, is being haunted by, stalked by, and even pummeled by jarring eruptions of sound.

The first Boom! startles her from sleep. And there are more to come as she visits her hospitalized sister (Agnes Brekke) in Bogotá. After a long silence in the hospital room, Jessica's sister wakes to describe how she is racked with guilt for having rescued a dog and then abandoned it. This only troubles Jessica further, as she soon finds a mysterious dog following her around. Is it possible that she might be haunted by the consequences of others' failings?

I like the surprising line of connection that Mike D'Angelo of The AV Club draws for us: "Not since Todd Haynes’ Safe has a murkily understood, possibly psychosomatic ailment been reconceived in so haunting and unforgettable a fashion." I might agree with that: There is an unsettling horror beneath the surface — literally, underground — in this film that reminds me of the nameless curse that fractured and isolated Carol (Julianne Moore) in Haynes's classic. But I also thought of moments in David Lynch's films in which we sense a spiritual force of darkness simmering around the edges of our understanding.

A great deal of credit for that effect goes to the sound-design team of Raúl Locatelli (sound director), Akritchalerm Kalayanamitr (sound designer), Javier Umpiérrez (sound designer). And, as if to draw attention to their work, Weerasethakul follows Jessica to a sound studio, where she engages a sound designer named Hernán, describing the sound that afflicts her. He happily strives to recreate it for her, intrigued and challenged. Perhaps by recreating it, Jessica will come to understand her curse a little better.

And she does get something out of it — a song in which Hernán has incorporated the sound. The film leaves us to decide if this is just a self-serving, self-promotional effort by an enterprising young recording artist, or if Hernán has blessed Jessica with the gift of his attention. Maybe he has redeemed her suffering, to some extent, by making something meaningful of her madness. It's hard to say.

An archaeologist (Jeanne Balibar) invites Jessica into a restricted lab to show her bones unearthed during a deep-earth tunneling project, bones that include a skull with a mysterious puncture — a remnant of a ritual that was carried out to "release bad spirits." This gives us another thread to track through the film: the opening of cavities in people, in the earth, and in the spirit world in ways that might be unleashing transformative forces.

But then things start getting stranger. Jessica begins to doubt her sanity. People she thought dead turn out to be alive and well, and some she spends time with vanish without a trace. Sound effects and surreality begin to resemble the confounding multi-dimensional sensations of David Lynch's Twin Peaks: The Return. Has Jessica stepped through into some alternate dimension? Is she a pawn in some kind of spiritual warfare?

The film's final act, which takes us out of the city and into the wilderness (where Weerasethakul always seems most at home), is its most enthralling — a series of long-take scenes between Jessica and an aging fisherman named (brace yourself!) Hernán who tells her he has never left this place. What follows is one of the quietest, strangest, and most entrancing scenes I've witnessed in years (and that will soon be followed by another that's even stranger). Together, Jessica and the second Hernán (played with rough, real-world authority by Elkin Díaz) begin to put the pieces of their separate mysteries together to discover that they are both a part of a larger puzzle, one that stretches across time and space.

And it is here that the film veers into Tree of Life territory, with a long and wordless shot that rivals the dinosaur scene in Malick's film with its "What did I just see?" quality. "Is this part of the same movie?"

I won't explain further, as I would hope that others have similar opportunities to be surprised. Suffice it to say that I think Weerasethakul sees Jessica as a sort of avatar for all artists — someone who serves as a human satellite dish, receiving (unwillingly at first, but eventually with a cautious intent) the ongoing echoes of past injustices, gathering and focusing them as a witness to the truths that are still relevant no matter how long ago they took place, or how deeply buried they lie in the strata of the earth. At least, that's how I'm reading it on this first — and, perhaps, last — experience of the film. It's as if Jessica can touch the curve of a violin and hear the music it has absorbed over time, the sound that goes on resonating.

So, why is it so unlikely that I will get to share this movie with you?

Justin Chang at The Los Angeles Times explains:

... “Memoria” is the beneficiary of an appropriately experimental release strategy devised by its distributor, Neon. ... The idea is for the movie to play exclusively and eternally on the big screen, one theater and one city at a time; it will never be made available on DVD or home-streaming platforms. When this plan was announced months ago, some dismissed it as elitist — hardly the first time that word has been hurled in Weerasethakul’s direction. Others, myself included, couldn’t help but applaud Neon for treating “Memoria” as not just another chunk of streamable content, but rather as a work of art that demands to be approached on its own terms and experienced under the best possible conditions.

To put it another way: Weerasethakul doesn’t make convenient movies, and our culture of instant cinematic gratification could scarcely be more antithetical to the way he perceives the world. And so there is something to be said for allowing his movie to reach its audience at a pace commensurate with its own serene, meditative rhythms. When you go to see “Memoria” — and I urge you to make time to see it — you may feel an instinctive kinship with Jessica from that jolt of an opener: Here you are, just like her, having left home to find yourself sitting in darkness, watching and listening and trying to figure out what the hell’s going on. There’s pleasure in this discombobulation, and within a few moments, you find yourself warming to Jessica’s company — and marveling at Swinton’s ability to both harness and downplay her natural magnetism.

I couldn't say it any better than Chang has.

I'm grateful I had that experience with a small audience of strangers at Seattle's Egyptian Theater. I wish you a similar opportunity. Just as Jessica seeks out massive refrigerators to preserve the "testimony" of her orchids, Weerasethakul is crafting cinematic time capsules, vessels made of image and sound that will go on bearing witness of the signals he receives. And I am grateful for such an opportunity to receive his witness. It expands and enriches my sense of all that is going on beyond the reach of my senses in the world.

Every age and every culture has its prophets. Weerasethakul is one of those visionaries alive and well and working among us. We should pay attention and pursue opportunities to do so.

Jon Batiste's "We Are" — a Looking Closer Top 20 of 2021 favorite — wins Album of the Year.

Congratulations to Jon Batiste!

The bandleader of The Late Show with Stephen Colbert, whose extraordinary talents are matched by his unmatched charisma, won Album of the Year at the Grammys last night.

I don't put much stock in the judgment of Grammy voters. This year was a strange exception: Allison Russell, my favorite artist of 2021, had three nominations for Outside Child, my favorite album of the year — which was a pleasant surprise, even though she didn't take home any prizes. I'm always delighted when excellence is celebrated at that glamorous, flashy event.

In honor of Batiste's excellence, I'm reposting what I published in 2021 about this remarkable record.

The title track of Jon Batiste's We Are is better than a blast of caffeine and sugar at getting me out of bed in the morning and launching me out into the world with a zeal to love my neighbors and do what I can to save the world with a smile on my face. Batiste has become such an essential part of The Late Show With Stephen Colbert, its childlike spirit, its fount of everlasting improvisational inspiration... its soul. (It makes sense. Didn't he win an Oscar for his contributions to Pixar's Soul?) But it's not just the marching bands and ecstatic inspiration of that opening song — it's the whole thing. Batiste sustains a sense of divine inspiration as he reflects on the voices that have shaped him and motivated him throughout his life.

Many music critics who know more than I do about the history of the traditions in which Batiste's roots run deep... they've been rejoicing over this record. I'll let them get specific:

Josh Hurst, in his best of 2021 list, says that, when he listens to We Are,

[I]t’s clear that Batiste is actually pretty close to the center of several musical universes, uniting a swathe of Black music idioms (jazz and blues, hip-hop and R&B) into something kinetic, colorful, and purposeful. Loosely structured as a bildungsroman, the album traces Batiste’s journey from youthful innocence to a place of wisdom and advocacy. He is a polymath in the vein of Prince, but where the Purple One trafficked in kink, Batiste’s whole vibe is basic decency. And who couldn’t use some of that?

Here's Jackson Sinnenberg at Jazz Times:

[We Are] remixes the last 400 years of Black American Music to dizzying and wondrous effect. 'Tell the Truth' crossfades the relentless punch of early-’70s Booker T. & the M.G.’s with honey-sweet string arranging that suggests the likes of Jimmy Jones. The horns drive the brightness into your brain until you come out smiling. On 'Show Me the Way' Batiste stretches his vocals to the heavenly heights of ’50s crooners like Little Anthony while seemingly taking cues from the Thundercat song of the same name, blending rumbling rhythms with the melty melodies of slow-jam R&B.

It's an "Editor Pick" at Spill Magazine:

We Are is a stellar album that connects a rich level of tradition and modernity together proving Batiste is as steeped in classic gospel, soul, jazz, and funk as he is the pop and hip-hop of the last two decades. Furthermore, We Are is ties together a level of simplicity with sublime technical genius, making it a record that should be admired equally for its musicianship and intricate songwriting as for its ability to seemingly fit in with the contemporary music of today. If We Are demonstrates anything, it is that Batiste is peerless in his creativity and delivery. Often nostalgic for other eras and artists, Batiste remains truly unique as he joins the class of Kendrick Lamar, Anderson. Paak, and Gary Clark Jr. only in the sense that We Are is a record unlike anything else in the last decade and could only have been written by Batiste.

At AllMusic, Matt Collar walks through each track with wide-eyed admiration:

Using the best of the past to build toward a better tomorrow is a stirring notion that pervades the album, both musically and thematically. He draws upon the vigorous grooves of New Orleans funk pioneers the Meters with 'Tell the Truth' and crafts a buoyant, psychedelic-soul vibe with the help of author Zadie Smith on 'Show Me the Way.' One of the most vivid encapsulations of his old-meets-new sound on We Are is 'I Need You,' an electric amalgam of boogie-woogie blues and vintage hip-hop attitude -- like an impossible combination of Little Richard and OutKast. Batiste's genre-mashing reinforces the album's theme of intergenerational wisdom, and it's also wonderfully fun.

https://youtu.be/MkpvNaBe0mg

https://youtu.be/GvlN1Lr3yt8

https://youtu.be/4BuRjyqBIrA

Favorite Films of 2021 — Part Three: The Top 30

March madness continues!

If you missed Parts One and Two, catch up!

I've been asked by the critics at two different podcasts to name my favorite film of 2021, and it's been difficult to answer.

At Seeing & Believing with Kevin McLenithan and Sarah Welch-Larson, I narrowed it down to one... but then fell back into doubts and second-guessing soon after I named my choice. Listen here:

Then, on Veterans of Culture Wars with David Lester and Zach Malm, I gave a very different answer. You can listen to that conversation here:

Working on this list for publication here at Looking Closer, I wrestled with possible outcomes again. It may be that I will, in time, change my #1 pick. I've done that before. But for now, I've made a decision quite unlike any I've made in nearly thirty years of list-making. Let me know what you think, and feel free to share your own favorites.

For this first-draft of the list, I'm including 27 films. But that will change as I catch up with other great films of the year that I've missed. So, next time you come back, there might be 30 or more.

Here's are the annual fine-print disclaimers:

This list, like all of my film lists, is a work in progress.

Of course it is. The temptation to pronounce judgments on works of art is great — more than ever in this culture of “rating” things with “Like” or “Dislike,” “Fresh Tomato” or “Rotten Tomato.”

But great movies are like city parks: They are designed by human beings, but they contain all kinds of natural world sights and sounds that carry their own mysteries above and beyond the intent of the artist. They invite you to explore, and your first exploration is just the beginning. Your first experience has as much to do with your own choices and preferences as it has to do with the park's design. The circumstances of your experience play a role too: Weather, for instance, and who else happens to be there at the park on that specific day. Go back again on a different day, in a different mood, and your experience will be different.

Does that mean it’s a waste of time to bother with questions related to the quality of the park’s design and condition? Of course not. But it’s ridiculous to think we can pronounce a judgment on any work of art. Too much is conditional. Better to share impressions, keeping an open mind so we can be surprised and have that distinctively human experience of changing our minds.

I’ll probably expand this list over the next few months as I catch up with films that got away. For example, I haven't had an opportunity yet to see The Souvenir, Part II, but other critics who have found access to it have praised it as one of the year's greatest achievements. Others — Encanto, Procession, and even the popular Don't Look Up — are films I haven't watched yet for reasons related to timing, mood, or rental prices. I'll get to them soon. I'll go on revising the list as my appreciation of these films changes. I recently updated my lists from the 1970s!

I watched more than 180 movies in 2021, and have added many to that list in the first few months of 2022 — eagerly pouncing on new films, happily revisiting personal favorites, and making new discoveries from decades past.

This is a list of films that found wide release — and which I could access in Seattle — in 2021. It's a celebration of a year in which movies gave me hope, informed my conscience, and strengthened my faith.

26.

Judas and the Black Messiah

directed by Shaka King | written by King and Will Berson

https://youtu.be/sSjtGqRXQ9Y

My review of Judas and the Black Messiah was published in February 2021. You can read it here.

Uh-oh...

25. – 24. (tie)

West Side Story

directed by Steven Spielberg | written for the screen by Tony Kushner

based on West Side Story by Jerome Robbins, Leonard Bernstein,

Stephen Sondheim, and Arthur Laurents

and

In the Heights

directed by Jon M. Chu | screenplay by Quiara Alegría Hudes |

based on In the Heights by Quiara Alegría Hudes and Lin-Manuel Miranda

Only one qualifies, by my standards, as great cinema — an extraordinary work of big-screen artistry. But the other, a solid work of crowd-pleasing entertainment and social commentary, made me care and made me want to turn around and take the ride again right away.

Put another way — one is a movie I want to study; the other is a movie an album of pop bangers that I could count on to break up the heavy clouds of a depressing year.

https://youtu.be/U0CL-ZSuCrQ

https://youtu.be/A5GJLwWiYSg

I published my full review of In the Heights here at Looking Closer way back in June of 2021. You can read that here.

My first impressions of West Side Story were previously published here in an installment of "The Weekender." You can read them here.

23.

Flee

directed by Jonas Poher Rasmussen | written by Jonas Poher and Rasmussen Amin

https://youtu.be/WzUVeuX1u04

As Amin Nawabi recalls and relates the harrowing secrets of his lifelong search for a home — fleeing Afghanistan as a child, enduring the terrors of human trafficking, and arriving rather accidentally in Denmark — we can hear him reluctantly reliving the trauma, but we also hear him speaking truths that he has kept bound up in fear and distrust. In doing so, we can hear him finding some measure of freedom. Listening and then transforming into animation what he has received, director Jonas Poher Rasmussen delivers a revelation that just might ignite empathy for refugees and outcasts in the hearts of audiences around the world.

This is the only animated film of 2021 I've seen so far that has really captured and held my attention beginning to end. It's clearly a labor of love. I'm impressed that all of its disparate elements—the interview, the animation, the historical footage—cohere so gracefully into what becomes a shining example of filmmaking as an act of compassion.

As my teaching schedule prevented me from writing a full review of this film, I refer you to the great Alissa Wilkinson at Vox.com for wisdom and details. Alissa writes,

[W]e interact with Amin’s life as if it’s in the grand storytelling tradition, a tale with meaning that stretches beyond the simple facts.

Amin fears being hurt, losing his family, being alone, and being rejected for being gay — and most of his fears come true. He longs for safety and for home, a place where nobody will come to take him away. And yet, when he finds it, he can’t quite believe it. By the time Rasmussen and Amin discuss his history, it’s almost 20 years in the past, but for Amin, it’s as if it happened yesterday. He’s become educated and successful, reconnected with most of his family, and found real love. But even after finding safety and relative stability, Amin’s previous experiences will never stop reaching their long fingers into his present.

There’s a deep meaning to Amin’s story beyond the specific facts of his life. All over the world, people are forced to flee their homes. If they’re very lucky, they might resettle in a place where they’ll be able to live some kind of better life. But that doesn’t mean the trauma subsides. By the end, it seems telling his story — saying it out loud in a safe space, at last — may have helped Amin heal a bit more. Perhaps sharing it with audiences opens the same space for others, too.

22.

Bergman Island

written and directed by Mia Hansen-Løve

https://youtu.be/nrlVHVid-20

My notes on Bergman Island were published previously here at Looking Closer in an installment of "The Weekender." Read them here.

21.

Passing

written for the screen and directed by Rebecca Hall | Based on Passing by Nella Larsen

https://youtu.be/trwq3CNCMkU

I reviewed Passing here at Looking Closer back in November 2021. Read the review here.

20.

The Father

directed by Florian Zeller | screenplay by Zeller and Christopher Hampton |

based on Zeller's play Le Père

https://youtu.be/4TZb7YfK-JI

Don't be confused when they call the main character Anthony. It's distracting, yes — but that's who Anthony Hopkins is playing.

And don't worry if you feel like Anthony's increasing dementia is contagious and it's starting to affect you. The filmmakers aren't playing fair: They've cast, in the roles of two women who the old man keeps confusing for his daughter Anne, both of Britain's great Olivias. That's just Zeller and Company messing with us.

Now... if you could swear that you saw Rebecca Hall walk in and play a scene or two, confusing things further — that's just you, and maybe you are getting old. Or maybe you just haven't been to the movies for a long time and you aren't as sharp on names and faces as you used to be. I'm not saying this for any reason in particular.

...

And no, we're both wrong. Those fleeting opening credits didn't say "Edited by Yorgos Lanthimos," although the challenges that the film poses to the audience might make you wonder. It said "Edited by Yorgos Lamprinos." See what I mean? This movie seems made to mess with us.

...

Note: Somebody needs to bring Rufus Sewell back to the movies and give him something better to play than a heartless bastard. He's very good at it — and he's good at it here, as usual. Still.

...

Another note: This may not be the movie for you if your spouse's mother is in a memory care center and often doesn't know who she is anymore. But then again... it may be the movie for you because screenwriter Christopher Hampton (Carrington, Dangerous Liaisons) will assure you that these soul-crushing ordeals are actually quite common and that you are not alone in trying to figure out how to navigate such brutal, faith-shaking circumstances.

19.

Licorice Pizza

written and directed by Paul Thomas Anderson

https://youtu.be/ofnXPwUPENo

My relationship with every Paul Thomas Anderson film changes over time. I'm usually enchanted or awestruck from the start, and then my admiration deepens into rewarding endeavors of interpretation. But not always. I admire Boogie Nights and Inherent Vice, but I don't particularly enjoy them the way I do Phantom Thread or find anything personally resonant in them as I do with Magnolia.

My relationship with Licorice Pizza is off to a rocky start.

I admired a great deal about it as it played: production design, performances, surprises.

But, unlike Punch-drunk Love and Phantom Thread, the other two PTA romances, both of which I've fallen madly in love with, this movie — in its jarringly episodic nature, in its rough and grimy aesthetic, and in its web of alarming and exploitative relationships — I can't say I ever settled into enjoying this one. I wasn't enchanted; I was on edge and often aggravated. It has some fantastic sequences. It's glowing with passion, full of scenarios that could only have been inspired by personal experiences. And it's a circus of "Spot the allusion!' and "Note the influence!" (you'll probably think of Robert Altman films, Taxi Driver, Almost Famous, Rushmore, The Graduate, Once Upon a Time... In Hollywood, and PTA's own previous films). But I was so often annoyed by the characters that I found myself checking my watch at the 90-minute mark and a little itchy to get out of town.

Every relationship in this movie is fractured by an imbalance of power — Alana (Alaina Haim) is too old for Gary (Cooper Hoffman), Jerry Frick (John Michael Higgins) is disrespectful to his wives, Wachs (Bennie Safdie) has to confine his lover to save face with voters. And then there's the way a movie star (Sean Penn) can so easily exploit a lonely and uncertain young woman's longing for affirmation.

Everyone is faking expertise in something — Alana fakes her skills and spoken languages in talent interviews, Jerry Frick fakes speaking Japanese, Gary fakes knowing how to to drive, Jon Peters (Bradley Cooper) is just a complete and total fake, etc.

So I find it strange that any critic would single out a particular character or relationship dynamic as inappropriate or singularly cringey. Everything about this world is unfortunate and inappropriate and more than a little cringey. It's a hall of mirrors, this web of relationships; that appalling Frick and his Japanese wife (either one) are Gary and Alana... are Joel Wachs and Matthew. Fakery and abuse seems to be the standard in this context of 1973 showbiz. Everyone's being mistreated, and those doing the mistreating are obviously buffoons (at best) or monsters (at worst). Sex has become so toxic in this context that the story focuses instead on the idea that a love affair can flourish without it — and, in some cases, might only exist so long as they abstain.

Perhaps the title, beyond its direct inspiration (the record store glimpsed in Fast Times, is a reference to two things that shouldn't go together and yet it will work for one or two people out there. Have you ever had a relationship in which there is a certain and singular sexual tension, and you both know you're a little bit in love, but you also know that it can only exist in that state, and any "step" would cause a stumble and a fall? There's something like that happening here. Gary and Alana can't bear the thought of anyone else becoming the other's confidant and intimate, and they're jealous to see each other with anybody else, but they also know that they'd better remain more platonic than erotic together. I get that.

And in that context, if a 15-year-old boy and a 25-year-old young woman discover some kind of inexplicable connection or chemistry — it's not Harold & Maude, but it works for them (even if Gary's as surprised by it as Alana is unsettled by it) — maybe we should be more inclined to hope that they can develop some kind of helpful and meaningful relationship in the madness, rather than just have an attack of age-gap cooties. (Something tells me that those who object to the age difference here haven't complained about Emma Thompson's casting in Sense & Sensibility, in which the gap between Alan Rickman and Kate Winslet is far more substantial.) Gary's idealism and irrepressible industriousness are strangely appealing to the bored and insecure young Alana, and Alana's proximity and availability and loneliness make her an appealing prospect for Gary's eager attention-seeking.

And so, the enterprising boy and the affirmation-seeking girl need each other — that can't be too hard to understand. No, it's not a healthy relationship — they're dishonest with each other, disrespectful, selfish, unfaithful, and often downright mean. I'm not inspired by either of them. But maybe this isn't a story about inspirational figures or swoon-worthy love stories. Maybe it's about growing up in a chaotic and cruel world and lunging for whatever kind of relationship drug is going to bring out a better version of you and save you from the types of relationship drugs that are sure to wreck you. Maybe it's about how, when all avenues that the world offers us prove to be fraudulent and dehumanizing, we have to dream up a place of our own to figure things out. In that sense, there might be a little Moonrise Kingdom happening here, too.

Unlike Sam and Suzie in Moonrise Kingdom, Alana and Gary aren't a couple whose company I enjoy, and I won't be eager to revisit them. But they make me hope they can find a way through seasons of awkwardness, misfortune, hormonal chaos, and a sorry dearth of options. They need each other, and I'm glad they have each other. But I do hope they find better tomorrows. To borrow a line from Rowlf the Dog — "I hope that somethin' better comes along." For both of them.

18.

No Sudden Move

directed by Steven Soderbergh | written by Ed Solomon

https://youtu.be/7GRDLX3a-IE

17.

Derek DelGaudio's In & Of Itself

directed by Frank Oz | written by Derek DelGaudio

https://youtu.be/_62BeXxd_jo

A performance-art magic show made of humility, confession, wisdom, and love.

And it moves us because it reminds us of what is True. We are known. We always have been. We are loved. We always have been. And when the Truth of that is spoken in love, we are undone.

I went straight from watching this to reading Psalm 139.

O Lord, you have searched me and known me!

You know when I sit down and when I rise up;

you discern my thoughts from afar.

You search out my path and my lying down

and are acquainted with all my ways.

Even before a word is on my tongue,

behold, O Lord, you know it altogether.

You hem me in, behind and before,

and lay your hand upon me.

Such knowledge is too wonderful for me;

it is high; I cannot attain it.

Where shall I go from your Spirit?

Or where shall I flee from your presence?

If I ascend to heaven, you are there!

If I make my bed in Sheol, you are there!

If I take the wings of the morning

and dwell in the uttermost parts of the sea,

even there your hand shall lead me,

and your right hand shall hold me.

If I say, “Surely the darkness shall cover me,

and the light about me be night,”

even the darkness is not dark to you;

the night is bright as the day,

for darkness is as light with you.

For you formed my inward parts;

you knitted me together in my mother's womb.

I praise you, for I am fearfully and wonderfully made.

Wonderful are your works;

my soul knows it very well.

My frame was not hidden from you,

when I was being made in secret,

intricately woven in the depths of the earth.

Your eyes saw my unformed substance;

in your book were written, every one of them,

the days that were formed for me,

when as yet there was none of them.

How precious to me are your thoughts, O God!

How vast is the sum of them!

If I would count them, they are more than the sand.

I awake, and I am still with you.

...

Search me, O God, and know my heart!

Try me and know my thoughts!

And see if there be any grievous way in me,

and lead me in the way everlasting!

16.

Quo Vadis, Aida?

written and directed by Jasmila Žbanić

I reviewed this film back in August 2021. Read the review here.

15.

Mass

written and directed by Fran Kanz

https://youtu.be/WgvsfKhGdgI

I reviewed Mass at Looking Closer in November. Read the review here.

14.

Identifying Features

directed by Fernanda Valadez | written by Valadez and Astrid Rondero

When Magdalena, a Mexican mother venturing into dangerous territory to find her missing son, comments to another boy that he resembles her son "from behind," the boy replies with words that resonate at the conclusion as we think back through the whole film: "We all look the same from behind."

It's an enigmatic moment that might comment on how the rest of the world seems unconcerned about the countless missing and dead in Mexico's drug wars. Or it might comment on how so many young Mexican boys and men come to the same dead end — vanishing into a darkness that it would arguably be unwise to investigate, a field of flames from which no one returns without scars.

This is a quiet, nerve-wracking journey reminiscent of Cormac McCarthy ventures into blood-soaked wildernesses, where what you imagine you might discover there will only teach you that your imagination is not large enough to fathom the wickedness wreaking havoc in the world. As one memorably un-subtitled scene impresses upon us, our vocabularies are not powerful enough to communicate the deeds that the devil is doing in the darkness.

As we follow Magdalena into a wilderness that resonates with the same sense of evil I remember from watching Eggers' The Witch, we know she may never return. We know that she is more than likely to find her boy's body mutilated or burned... or both. We can sense this isn't going to be a story about a miraculous rescue. But what is it about then?

It feels like a lament, one that cries Things are so much worse than we thought.

I can't say more without robbing you of the chance to discover some of the most haunting moments I've experienced at the movies in years. This isn't a film that is going to tell you that love conquers all. But it might test your faith and challenge you with a question: Is the love you believe in more powerful than what the devil is doing right now — in Mexico, at the hands of the drug war's soldiers; in Ukraine, at the hands of the Russians; and even in America, in the plans of those who do not really believe in "liberty and justice for all"?

If the prayers earnestly raised early in the film had been reprised during the end credits, I can tell you this: I would have prayed along with them.

13.

Annette

directed by Leos Carax | story and music written by Ron Mael and Russell Mael with Carax

https://youtu.be/l_EaNpL16SU

I watched Annette twice — enthralled, baffled, and frustrated. But I haven't stopped thinking about it. And my conversation about the film with film critic Evan Cogswell (who loves this film beginning to end) was rewarding. You can listen to that here.

12.

Spencer

directed by Pablo Larraín | written by Steven Knight

https://youtu.be/WllZh9aekDg

As much as this movie laments the constraints of tradition and the suffocating nature of being a living symbol, we aren't watching this if it isn't for the extravagance of the royal family's opulence — the clothes, the cars, the cuisine... right? So it's hard to deny that, by showing up, we're still enchanted by, and somewhat complicit in, the stubborn resilience of the Royal Fantasy — the same one that closes its jaws around Diana, chews her up, and then, when she fights, spits her back out with contempt. The director and the cinematographer are certainly spellbound — they're enamored of this architecture and finery. This movie is a luxury to look at. They know what they've got: a chance for one of the most interesting actresses in cinema to dance and snarl and sob her way through a costume party.

And yet, all hail Kristen Stewart, who gives her finest performance yet here. I was skeptical when Assayas crowned her the next Juliette Binoche, but this finds her fulfilling that promise: this really is Binoche-level stuff from her.

And the film's intriguing tone, which involves metaphors so heavy-handed that screenwriter Stephen Knight couldn't possibly expect us to take them seriously, feels less like a biopic and more like a campy psychological horror movie. From the opening scene, it's often quite funny. Sure, references to The Shining are as obvious here as Dune's distracting adulation of Apocalypse Now — but they're a good hint as to how we're supposed to take this whole thing. Subtlety would have seemed out of place. This is a movie about high emotion, a metaphor for finding yourself suffocating in a world of hypocrisy, an opera about trying to escape a trap without losing your one friend and your two children. And Stewart plays it perfectly.

The great Timothy Spall's energy here is fascinating. He could have been merely dour, a specter of foreboding assigned to prevent Diana from having any room to breathe, but he manages to give us glimpses of a complicated human being inside the carefully tailored costume and the scowl that looks like its been stretched to its limit by some internal drawstring. What a gift Spall is to cinema.

But I really want to talk about Sean Harris: Between his King Arthur in The Green Knight and his Chef to the Queen here, this dude is having himself a year.

And Johnny Greenwood ... well, is there anybody more reliable scoring movies right now?

11.

Azor

directed by Andreas Fontana | screenplay by Fontana and Mariano Llinás

https://youtu.be/_nkaWcqZO1I

"Imagine if Graham Greene rewrote Apocalypse Now...." - Nick James, Sight and Sound.

Exactly.

I'd have to look back a long way to find a film that gave me this particular buzz of "Wow — finally, a movie for adults who enjoy thinking." The tension in this film is exquisitely cultivated. It's particularly scary because it feels so true to life, refusing to ever provide expository dialogue or dumb things down to explain itself.

This movie made me feel ignorant in a way that I've come to find thrilling: It made me want to learn more about situations, politics, vocations, and paradigms I now little to nothing about, but that I know are more important and more influential than 99% of what makes headlines. I don't know much (okay, anything) about the power games at the highest echelons of the Swiss banking world, or how they influence ongoing colonialist oppression and corruption in regions I've never studied or visited. (I know, for example, embarrassingly little about the history — or the present, for that matter — of Buenos Aires.)

But this movie made me want to understand its social-political quandaries, even as it threw fuel on the fires of my existential dread about an encroaching age of unprecedented tribulation in a world terrorized by "beasts" (to borrow this film's term). Imagine Michael Mann directing his subtlest, quietest film about a criminal underworld, with a script by Cormac McCarthy, and you're in the ballpark. The films I thought about most were The Counselor and No Country for Old Men. This is probably the scariest movie of 2021, partly because I believe its warnings and revelations are True.

It's also one of those rare and powerful films that exemplifies the "less is more" principle, one that is almost always true in cinema.

And Fabrizio Rongione is fantastic.

10.

Drive My Car

directed by Ryusuke Hamaguchi | screenplay by Hamaguchi and Takamasa Oe |

based on "Drive My Car" by Haruki Murakami

https://youtu.be/bx1Q1MauBsU

Or, Vanya on So Many Hiroshima Streets.

A film far too talky, thematically layered, and complex for me to post immediate notes about it. It may be that its reach exceeds its grasp, but if so… still, what a reach! And it may be that the most affecting moments have more to do with Anton Chekhov than Hameguchi, but if so, they’re well played. It’s too early for me to say.

So I'll just say these three things:

1. I'll be watching for more leading performances by Hidetoshi Nishijima, who, it turns out, already has experience in that most difficult of niche genres: big-screen adaptations of Murakami. (He was the narrator for the great Tony Takitani.)

2. I kept finding myself thinking "This movie keeps forgetting about cinema and devolving into just cameras aimed at people talking or driving," and then, suddenly, there would be a shot so inspired that I'd feel like we were in the presence of a master.

3. Besides the other Vanya movie, the film I was reminded of most during this one was Columbus, and that's a good thing.

4. This film introduces us to a married couple who, as supporting characters, are so much more interesting to me than the two leads that it distracts me.

9.

Dune

directed by Denis Villeneuve | based on the novel by Frank Herbert

and adapted for the screen by Jon Spaihts, Denis Villeneuve, and Eric Roth

An epic as grand as Dune deserves an epic review. My review of Part One is exactly that.

8.

The Power of the Dog

written and directed by Jane Campion | based on The Power of the Dog by Thomas Savage

https://youtu.be/LRDPo0CHrko

I am the only human being to have watched the first half of Wes Anderson’s Isle of Dogs at home, interrupted it, rushed to the local cinemas to see Jane Campion’s The Power of the Dog, and then returned home to finish Isle of Dogs.

Both films have haunting whistled motifs!

Strong performances, particularly from Smit-McPhee and Cumberbatch (with a jarringly inconsequential supporting turn from Thomasin McKenzie, suggesting she had a larger role in the initial screenplay). Beautifully shot. With a stellar score from Johnny Greenwood — the second great score he's delivered in a month's time (Spencer).

This whole film felt like Campion revisiting The Piano, but the variations are interesting.

We're in a wilderness of a landscape, where forces of nature are always and obviously (as they often do in early Peter Weir films) overwhelming the people making trouble in the foreground.

We have a Mother (Dunst) and Child (Smit-McPhee) — Mother carrying some trauma that keeps her from expressing herself, Child playful and curious and fearful and fiercely bonded to the mother. Theyr'e caught between The Good Man (Plemons), who represents the highly mannered charades of the civilized, and The Wild Man (Cumberbatch) who seems half-absorbed by the natural world, wiser than the Good Man in some ways and cruel in others.

There is also a piano, gifted to the Woman as a sign of love and a symbol of sophistication, but ultimately a symbol of some unreachable transcendence, an ideal that the cruelty of the world makes unattainable.

In this variation of the story, while The Good Man seems loving and conscientious but also rather useless in the face of serious threats (like a misogynistic brute or alcoholism), the Wild Man has split in two, half of him a monster obsessed with control and with punishing others who are still striving for sophistication, the other half living in a hell of confusion, shame, masturbatory fantasy, and self-loathing. The Wild Man hates the piano just as he hates the wealthy city people (represented by the Governor and his wife); he likes disappointing them, disrupting their parties, mocking their facile "order" made of simplistic binaries, but he also grumbles and resents that they seem to have some measure of a peace he cannot have.

The film's exploration of sexuality is much more complex than I'd anticipated, suggesting that masculinity of the Toxic variety is like a tumor, a manifestation of a cancer made of fear and shame. The Wild Man's hatred (of others, of the self) stems from (pun intended) the fact that sexuality is frighteningly complicated and will not be tamed or organized. While the Child — in this case, a young male taunted by those trying to be "masculine" cowboys for being gay — seems to be withdrawing from the world of sex in despair, his Tormentor lives in a private hell of pornography and erotic nostalgia, imprisoned by memories of the older man who shaped him with both tenderness and abuse.

Ultimately, as is typical for a Campion film, the film ends up being a parable about how illusory our "civilizations" really are — systems that flatter our sense of control and confidence — while we are really far wilder, far more mysterious than we want to believe. But it's also about how that wildness, when suppressed, leads to distortions that are even more threatening than the insufficient architectures of order. The Wild Man is a human being, with real longings, powerful intelligence, and impressive skills born of experience — but he is also a menace, his secrets and lies inclining him toward the destruction of Love, or of whatever semblance of Love we can clumsily manage in this wasteland. We tend toward extremes that end up trying to kill each other, which seems inevitable since it is so very, very difficult to find a way of life in the land of Ambiguity in between.

[MAJOR SPOILERS. YOU HAVE BEEN WARNED.]

But I'm still struggling to understand the significance of certain things — like what I'm to make of Rose's alcoholism, and if I'm to believe that it might have been overcome in the end; and whether I'm to interpret the conclusion as a triumph of good over evil, or a tragedy of one world striking a blow against the other. Whatever the case, the last moment plays in a way that makes me think I'm supposed to be glad about how things have turned out, but the film's deep dive into the tragedy of Phil's torment makes me resist any suggestion that this is a "happy ending." It looks more like a failure — human beings settling for order at the cost of the life of someone who saw through its hypocrisies.

7.

The Lost Daughter