Why Flow is my favorite film of 2024

An early draft of this review was originally published on December 21, 2024,

at Give Me Some Light on Substack, several months before it appeared here.

Subscribe, and you'll read many of these reviews while the films are still breaking news!

The flood is here.

The Black Cat, having fled the violent advance of a tsunami, worries her way around a cat-lover’s home that seems to have been recently abandoned. The wooded property is full of cat statues, and the attractive upper floor of the home still has canvases of half-sketched cats on the artist’s desk. But the human beings are gone — gone from the property, and seemingly gone from the world. The water is rising. And the cat is beginning to realize that all she could depend on is going to pieces. There may be no high ground high enough to escape the swelling.

In Flow, the enthralling new animated masterpiece by director Gints Zilbalodis and his co-writer Matīss Kažathe, the Black Cat does not speak English. The Black Cat is a Black Cat, not a Disney cartoon. She — I am going to call the cat she, acting on intuition, although the film does not specify gender — is nine tenths a cat as we know cats: wary and watchful, clever and resourceful, solitary and sometimes vain, prone to venturing into predicaments without anticipating the risks. Her physicality is exactly right, making her perhaps the most convincingly lifelike cat in all of animation.

And yet we latch on to this feline so fast that it’s as if we know her situation, or anticipate it. We feel a soulful bond with this cat whose world is crumbling into the irrepressible tide. Flow gives us not a single word we recognize in spoken or written word, but we bond with this cat and her occasional animal companions with an immediate understanding that this is about us.

The Black Cat, looking around in a panic for solid ground, lunges for a passing sailboat and finds herself in the company of a stranger who is different from her in so many ways: a capybara, blunt-nosed and raspy, but, it turns out, easy company and amiable.

Other passengers arrive…

- A Labrador retriever, playful and ridiculous and flamboyantly friendly, has parted ways with a pack of anxious and ungenerous dogs and does not seem to miss them so terribly.

- A lemur, whose hands grasp and caress an increasing collection of relics, becomes obsessed with and possessive of a vanity mirror that reveals him to himself and thus seems to imprison him in a narcissistic curse.

- A secretary bird, a towering captial-S of snowy white plumage, acts contrarily to her flock, paying attention to the plight of a vulnerable as if this activates some maternal impulse. (Warning: I'm not very familiar with secretary birds, but they play substantial roles here, and they are both beautiful and terrifying. If birds give you nightmares, proceed with caution.)

And I am catching glimpses of who I want to be in relation to my neighbors. I want to be the capybara who makes room for someone else in need. I want to be the bird who is willing, at great cost to herself, to care about a cornered outcast. I am cringing as I recognize myself in the lemur who spends so much of these glorious and dangerous days distracted by the “selfie” in the mirror, or how the reflections cast by that mirror can send the cat pouncing on illusions and chasing false lights in vain.

And all the time, as I am mesmerized by this menagerie of fantastic and furious creatures, by the paradox of their devastating and yet glorious environments, by the way a rush of water can transform a familiar world into a wonderland of ruins and surprises and horrors and beauty. The animation here, which my friend the animation scholar and illustrator Ken Priebe informed me was created with open-source Blender software, is simplistic and seemingly unfinished in some aspects of character design. But those choices, like the traditional simplicity of foreground characters in anime, allows for the richness and depth of the environments to enchant us and persuade us that we are really here, immersed in this revelatory crisis with this unstable and anxious community.

Flow is so much richer for its lack of a celebrity voice cast — or any voice cast. Thank God I never have to think about Chris Pratt — or any of the Chrises — as the credits roll. In that sense, Flow has more in common with classic silent films than any recent animated feature I can think of. Having said that, the sound design and score immersive and evocative. There is a shocking rush of color and sound in the film's closing act — a whiplashing and thrashing of water through rainforest branches — so exhilarating, so hope-restoring, that my eyes filled with tears. This is a world full of surprises. Sometimes, it seems that we're visiting a different earth in another dimension, where the mysteries of the ocean look much more like deep-sea dragons dreamed up by Hayao Miyazaki, and where Divine Intervention might not be outside the realm of possibility. But those occasions are all the more awe-inspiring for how familiar and, well, earth-y the rest of this film's dwelling world is.

Note: For a fantastic meditation on how the portrayal of animals in cinema can affect audiences, and how essential our engagement with animals is to understanding human nature, read the essay "'Who's to Say?': The Role of Pets in Wes Anderson's Films," by C. Ryan Knight, published in the collection The Films of Wes Anderson, edited by Peter C. Kunze.

The most magical flow here is the grace of the “camera.” Such masterful composition in almost perpetual motion! It's clear that the animators were committed to framing every moment from the most exciting vantage points. I kept thinking “That's the best possible angle on this scene — and not just because it looks amazing, but because of what we learn from it.” Virtuosic visual storytelling. There isn’t a moment that isn’t at least visually interesting. And so much of it is breathtaking.

This kind of storytelling won't resonate with everybody, or even many. I've learned that from seeing people cringe and turn away from works like Richard Adams's Watership Down and The Plague Dogs, Wes Anderson's Isle of Dogs, and George Miller's Babe or (moreso) Babe: Pig in the City that some cannot find peace with a certain balance between animal realism, magical realism, and apocalyptic fantasy.

But I love those films and stories. They move me. Watership Down, for example, more than any other text outside of the Bible, has become the lens through which I best understand the world and my life within it. And I feel very comfortable in this imaginary world where cats behave almost exactly like cats, Labrador retrievers behave almost exactly like Labrador retrievers, capybaras are capybaras and lemurs are lemurs.

Most storytellers would have turned this story into a quest to save the planet. Here, the immediate goal is to merely survive, moment to moment, as anything we might take for granted gets threatened in a sudden turn. And the grander priority, the one that feels momentous and dangerous, is to imagine the possibility of conscience. These almost-realistic animals are granted only slight superpowers by their creators: the ability to learn how to steer a boat by the tiller, for example; or the kind of problem-solving that distinguishes crows and ravens who might figure out how to pull a boat to shore by a trailing length of rope. But the boldest idea comes, I might guess, directly from Terrence Malick’s famous flashback-flourish in The Tree of Life where we see a dinosaur stumble into the concept of empathy, and then the subsequent realization that the restraint of a violent impulse might be, in some sense, Good. We see that moment occurring in myriad variations here, one in particular that looks like a direct visual quote from Malick’s “pre-historic” proposal.

And in that, Flow is a movie about animals that speaks most meaningfully to me about what the world needs now, about what the world has always needed most, about what the future of humankind and Planet Earth depends upon.

The flood is here. In so many ways, the flood is here. It is here in the consequences we have brought upon ourselves with our treatment of this beautiful blue planet as a garbage dump. It is here in the assault on the free press and on higher education, as billionaires and authoritarians seek to make populations poor and ignorant in order to better exploit and manipulate them. It’s here as a rising tide of nationalism and hatred washes away the hard-won glory of a Constitution that seemed too good to be true. It's here as citizens are stripped of freedoms, and as desperate immigrants and refugees watch their dream of survival and freedom jerked away from them by enemies of America's founding vision. It’s here as the illusions of power and convenience offered by technology corrupt our capacity for trust, submerging us in waves of mediocrity, fakery, and lies.

So many of us are looking around in disbelief as the good things we've considered foundational, immovable, and defining about our culture are violently submerged and dismantled. I look at the ruins of the university I have loved for several decades — a school closing down its programs in Theatre, Philosophy, History, Languages, Journalism, and so much more — and sigh like a heartbroken old man: “How could it come to this?” I look at the communities of churchgoers who taught me to praise God for his mercies, and I wonder how they decided to despise the whole ideals of generosity and grace, how they betrayed the fundamentals of the Gospel, and how they steered the American church toward practices of hypocrisy and cruelty.

And in this place of loss and grief, I feel blessed by Flow. The movie has made me more wonderstruck than I’ve been at the movies in a very long time. As the saying goes, this movie “makes me feel seen.” It reassures me that truths I once thought were simple and obvious might, in fact, still be so. And it helps me see beyond the immediate storms toward a possible future in which all things are slowly being made new.

I'll be surprised if I meet anyone who loves Flow as much as I do. It checks some very particular boxes for me — in its animation strategies, in the limitations of its storytelling paradigm, in its moral compass, in its imagination of harmony and reconciliation. But I hope you experience some of the rapture that ministered to me here. I'm definitely going back to see it again on big screens before it's gone.

Is The People's Joker the best Joker movie yet? (I know how I'm voting.)

An early draft of this review was originally published on November 14, 2024,

at Give Me Some Light on Substack, eight months before it appeared here.

Subscribe, and you'll read many of these reviews while the films are still breaking news!

When it comes to Batman movies, I'm a very small minority: My favorite Caped Crusader films are The LEGO Batman Movie and Batman Returns.

But what about Joker movies? I think I finally have my answer. Sorry, DC Comics fans — you’re not likely to get a review of Joker: Folie à Deux from me anytime soon. The reviews from trusted friends have convinced me that I’m not likely to become one of its very few fans. I’m always open to surprises, and I’ll probably give it a look on a streaming service someday, but right now there are plenty of other movies I’m eager to see and likely to find rewarding.

And, as it seems like supervillains have succeeded in taking the U.S. Presidency, the House, and the Senate, I’m not excited about watching movies that appeal to supporters of racist and genocidal authoritarians.

The fact is that I rarely feel compelled to see superhero movies anymore. If you’ve been reading my film reviews for long, you know that I burned out on the genre about, oh, 20 years ago — even before anyone used the term “MCU” for Marvel movies. And I haven’t regained an appetite or appreciation for it since.

I’ve admired a few special exceptions: Doctor Strange, Black Panther, and Into the Spider-Verse for example. But The People’s Joker introduces a spectacular exception to the list. It’s the most exciting variation on anything related to Marvel or DC that I’ve seen in ages.

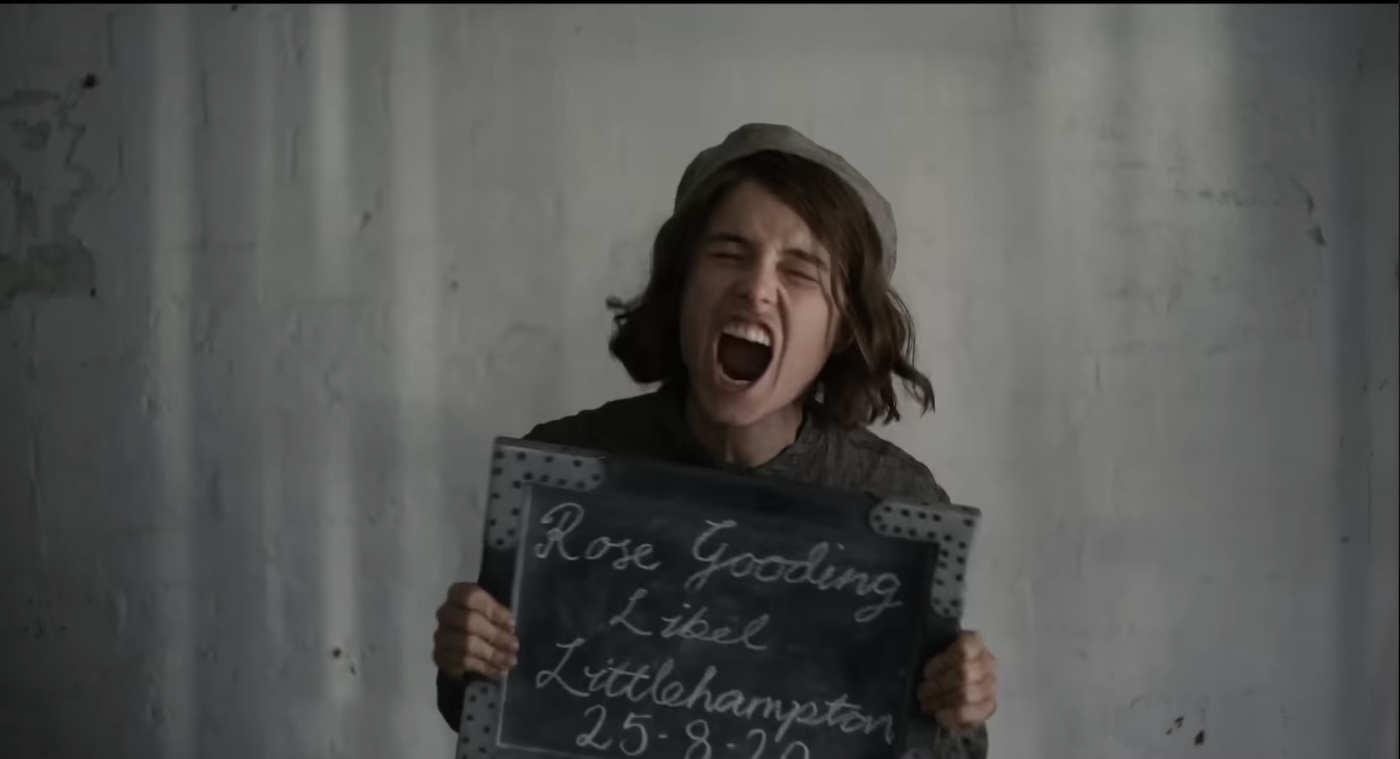

The People’s Joker is a singularly creative engagement with the genre, taking the familiar DC Comics world of Gotham City as a versatile vocabulary for a merging of memoir and fantasy. It incorporates comic-book animation, live-action footage, and lots of low-budget special effects into a kaleidoscopic, hyperactive, relentlessly entertaining 92 minutes. And that’s more than enough time for actress Vera Drew to offer a testimony of what her experience as a transgender woman has been like, from the rejection of her parents to her struggles to gain traction as a stand-up comedian in New York (Gotham) City.

The film has stirred up a lot of controversy and conversation as it plays fast and loose with DC’s rigorously protected IP. But the buzz it has gained at film festivals has given it good momentum, and now it’s available as a streaming rental on Apple TV+ and Amazon. (If that’s not helpful to you, consider this: I checked out the DVD from my local Seattle library. Support your local libraries! Republicans may take them away from us soon.) I recommend The People’s Joker to anyone who has any enthusiasm for the world of Batman and The Joker, but I’d recommend it even more enthusiastically to anyone who hears a lot about transgender individuals but who rarely ever hears from them.

That many moviegoers are discovering it while the documentary Will and Harper is winning fans on Netflix suggests that we might be nearing a vital turning point in popular opinion on the subject — regardless of the fact that Traitor Trump’s MAGA minions have been spreading lies, hatred, and fear, to the greater endangerment of our transgender neighbors, neighbors I love and support. It’s hard to imagine an America in which that hatred does not still run hot, but I’m hopeful for better days.

I have been lucky enough to find meaningful friendships in my local LGBTQ community, and I am learning so much from people I once condemned out of ignorance and fear. You’ll find that a lot of professing Christians still do brand their LGBTQ neighbors as sub-human, marking them for abuse and contempt. I dare say that such cruelty exposes hypocrisy and betrays the very Gospel they claim to love. I can say that, because I was, not so long ago, just such a hypocrite. So many of the opinions I held even just ten years ago have changed, melting away in the revelatory light of actual relationships.

This is the kind of movie that might make a difference for people.

I grew up in a culture where "Sharing Your Personal Testimony" in an evening church service was exalted as the highest form of entertainment, guaranteed to earn the performers a tearful ovation, hugs, and assurance of having pleased the Lord. Once in a while, I would hear something startling and real. But it was, for the most part, such formulaic entertainment. (A lesson I’ve learned the hard way: If God is at work in your life, it’s not likely to manifest in a way that coheres into a crowd-pleasing paraphrase.)

- Color outside the familiar lines in your Personal Testimony, and you were dragged offstage by that cartoon hook.

- Say anything that made listeners uncomfortable, that wasn't what they wanted to hear, that suggested their narrow definitions weren't Absolutes, and you would suffer a low Audience Score.

- Suggest that coming to Jesus had done anything other than solve all your problems, wipe away all your tears, and make you permanently happy, and your story would fall under suspicion.

- And if you implicated anyone other than The People of the Unchurched World for your hardships, if you suggested that harm might come from inside the Community of the Redeemed, you were regarded as a threat, as someone being influenced by the Enemy.

I’m not suggesting that The People’s Joker is a movie about evangelicals. In fact, for a movie about an artist’s trans experience, it’s rare in its lack of attention to religion. (There are broad objections to far-right talk radio, but no explicit Christian-bashing. Surprising!)

So, why do I bring up Personal Testimony Night? Because this movie has all the un-subtlety of one of those testimonies. It’s a feverish and forceful narrative about someone waking up to a truth that illuminates the falseness of so much else, and about how her pursuit of the light is both a journey into liberation and a path into new kinds of abuse and suffering.

At the same time, this movie breaks all of those unspoken Testimony Night rules. Comedian and filmmaker Vera Drew doesn’t care who she offends here. She’s ready to implicate any and everyone — including herself — in the troubles she has endured.

The artist’s mantra of "Show don’t tell" doesn’t apply to all forms of creative expression — especially memoir. If you’re making art of your life story, some degree of telling is necessary. Drew’s testimony — a story of waking up, coming out as trans, and paying the price in all the predictable ways — tells and tells and tells. But it does so while also showing in all kinds of creative and challenging ways, making this the most relentlessly and ebulliently inventive work of hyper-pop pageantry since Everything Everywhere All at Once.

It also outshines many (if not most) of the Personal Testimonies I’ve ever heard by being fearlessly honest — making room for expressions of uncertainty, regret, and longing, and opting for a "To Be Continued" conclusion instead of feigning any resolution. That is to say, it feels truthfully human. It gives us a self-portrait of a person in a state of flux. We’re all in flux to varying degrees, of course — but few of us have the vocabulary to perceive that in ourselves, and even fewer have the courage to investigate it. The People’s Joker gives me a rare feeling that has something to do with gratitude and something to do with relief — because I know I’m being told the unapologetic, uninhibited, uncensored, and unvetted truth.

A movie like this could so easily seem full of itself, bitter, and vengeful. And this does, at times, give some of those vibes. But the ego and the anger feel earned. And there's also so much joy in Drew’s unleashed creativity, in the way she's giving herself permission to live beyond the constraints of other people's expectations. Sure, she's been taking names and now she's ready to kick some ass. But there's also a self-effacing spirit to the whole thing that makes this Joker seem like a hero-in-the-making, not a villain in a spiral.

If God is love (this I still believe), then I suspect God is pleased with this testimony.

I’ll admit, my attention started lagging for sheer exhaustion due to the movie's relentlessness. Its 92 minutes feel closer to 120. (I felt the same way about Hundreds of Beavers.) And it is, at times, abrasive in a way that tests my patience (although that’s my problem, not Drew’s).

Nevertheless, I want to live in a world where movies as passionately personal, as relentlessly creative, as exhilarating in their "deal-with-it" truth-telling—movies like this one—aren’t such rare occasions. 2024 is a year I'll remember as a time of promising and resourceful creativity at the movies, where many gifted filmmakers said "Let's start from scratch and re-imagine what movies can be." This is just the latest of several recent films that make our future at the movies seem promising again. And, better, it gives me hope that many of the most misunderstood, slandered, and persecuted people I know might begin to find more kindred spirits, more caring hearts, more gestures of love and support in this hateful, violent world.

You'll love what Elliott learns from her "Old Ass"

An early draft of this review was originally published on October 23, 2024,

at Give Me Some Light on Substack, several months before it appeared here.

Subscribe, and you'll read many of these reviews while the films are still breaking news!

Horror seems to remain the reigning genre for Friday-night moviegoers this year. And that makes a weird kind of sense to me: In the last several years, we’ve suffered through a global pandemic, lost loved ones to its deadly influence, and lost more loved ones to conspiracy theories and COVID-denial. My fellow Americans and I have watched the nation we love—the one professing to be land of “liberty and justice for all”—go into septic shock as the deadly toxins of racism, fascism, and Christian nationalism surge, undermining all that gives us a chance to be great. We’re watching as wars overseas escalate into full-on genocide, and we’re asking how it’s possible that we’re the ones supplying the machinery for slaughter.

When the world is so fraught with terrors that seem too big for us to stop them, we need the catharsis of scary stories. And we especially need those rare genre contributions that bring with them some kind of wisdom.

But if you’re like me, you can only take so much horror. And when the daily news seems more appalling than anything a movie can serve up, you’re grateful for those films that can provide some kind of escape from the garbage compactor of daily headlines.

Fortunately, horror isn’t the only trend. Throw a Milk Dud into a cineplex these days and you’ll probably hit a sentimental romance or a high-concept comedy that promises to blow your mind with its gimmicky hook. And I’m happy to report that one film in particular combines both trends into something special.

As the credits for Megan Park’s comedy My Old Ass finished rolling, I emerged from the theater with a big grin on my face, feeling high spirits and enthusiasm to recommend it. Perhaps that’s because I went in with low expectations. Perhaps it’s because my September and October have been grueling months so far, throwing one hardship after another at my head and heart. Maybe I’m just extra-grateful that a movie surprised me with unexpected pleasures, that it made me laugh, that it made me feel joy.

Or, maybe it really is that exceptional — as romantic comedies, coming-of-age stories, and sci-fi mind-benders go.

Let me think this through. Am I making too much of it?

If I describe My Old Ass as a “sci-fi mind-bender,” I don’t mean to imply that there’s anything psychologically distressing here. My Old Ass plays with an idea as unlikely, as simple, and as fun as Groundhog Day. Instead of waking up to live the same day over and over, Elliott (the fantastic Maisy Stella) stumbles into another impossibility: She meets and starts corresponding with her future self (Aubrey Plaza, low-key and lovely).

It’s the kind of premise that would fall apart if the film took it too seriously or tried too hard to explain it. Park avoids that. There’s a possibility that Elliott’s seemingly miraculous time-bending discovery is just a recurrent psychosis brought on by some particularly powerful mushrooms that she smoked on camping trip with her two close friends Ruthie and Mo (Maddie Ziegler and Kerrice Brooks). Who cares? What makes the premise play out convincingly is the awkwardness, the warmth, and the good-humored chemistry of the actresses playing Elliott in her late teens and Elliott at almost 40.

Park doesn’t even work hard to cast actresses that resemble each other. She just asks us to suspend our disbelief and accept Maisy Stella and Aubrey Plaza as the same character separated by about 20 years, and if we’re willing to play along, we’ll be rewarded. (I am so, so grateful that nobody tried to accomplish this with ageing or de-ageing animation.)

In doing so much with so little, and doing it with confidence, My Old Ass has some strong "Early Duplass" vibes. (Think Safety Not Guaranteed.) It's funny, its efficient without compromising on character, it has a joyful spirit, and it's remarkably tender in all the right moments. Park really loves her characters. All of them. And her cast makes me believe in them.

I can’t say enough about Maisy Stella. Okay, she’s apparently made quite a name for herself in a variety of media over a decade now, but this is my first encounter with her, and I’m immediately a fan. As Elliott, she gives us a fully realized human being who seems like one of my freshman writing students, a young woman who is eager to try things out on what we call “a journey of self-discovery.” Everything in this film depends on the audience believing in Elliott despite her bizarre circumstances. Stella makes us believe and—even better—love this reckless and somewhat flamboyant free-thinker. Her older self seems like a fantasy at first, but before the end credits roll I find that Plaza has become just as convincing, so much so that I wish we could spend more time with her character.

By contrast, Chad—played by Percy Hynes White of Netflix’s Wednesday—the “Summer Boy” who confuses Elliott’s ideas about herself, seems a bit too ideal, like he might represent the screenwriter’s ideal boyfriend. But everybody else in the movie treats him like he’s too good to be true too, so that helps.

If I have any major compliant, it’s that… well, no. I have no major complaints.

I have two minor complaints:

First, Elliott’s family seem unusually believable and real, especially her mother (Maria Dizzia) and the oldest of her brothers (Seth Isaac Johnson). But her father, who runs the family’s cranberry-farm business, seems vital to one of the story’s major subplots—the uncertain future of the business—and he gets far too little screentime. I suspect there were more Scenes With Dad that got cut for time.

Second, I wish I hadn’t realized what the Big Reveal was going to be long before it arrived. But then again, I’m not sure how they could have covered it up. And I’m not sure it matters that much. The strengths of My Old Ass have little to do with Shocking Twists and much to do with engaging scenes between endearing characters. (If the Big Reveal makes you wonder whether or not this movie was in any way inspired by another "glimpse your future self" movie from an altogether different genre, well… no big deal. It still works.)

As I teach and get to know current 18– to 20-somethings — about 25-40 of them every 12 weeks— I have a decent radar for films that feel truthful about them rather than merely fantastical. My Old Ass seems unusually persuasive, perhaps even because of its time-travel gimmick. In my conversations with college students right now, conversations constantly turn to the subject of their anxiety about who they will become and how they can avoid making big mistakes. In the film, these conversations that allow Elliott to interrogate her future self about how things turn out don’t sound written; they have an effortless spontaneity that is refreshing.

And, best of all, they suggest that if we were capable of reaching our future selves, we might not learn much at all. After all, in the future we are not enlightened beings. We can hope that we’re wiser. But we can safely assume that we will still be flawed, still be prone to fear and unhealthy regret. It may be that it’s our past selves, not our future selves, who have the most to teach us.

If you want to settle in with popcorn and a movie that will take your mind off your troubles for two hours, I recommend My Old Ass. If you want to see a movie that really gets young people who are making that transition from high school to college in 2024, I recommend My Old Ass. If you want to see a film about facing the future without fear, I recommend My Old Ass.

I reserve the right to come back and say I overrated this movie. Whatever I think of it next time, I’m grateful for how this lifted me out of my fatigue and reminded me to make the most of what’s right in front of me, here and now, instead of being dragged down by all the “what ifs” of tomorrow.

I'm eager to see what Megan Park does next.

No Other Land: these filmmakers are risking their lives so you will watch their movie

This review was originally published at Give Me Some Light on Substack last week.

Subscribe, and you'll get reviews like this one delivered directly to your email as soon as they are published.

March 15th's breaking news: One of the Palestinian co-directors of the Oscar-winning documentary No Other Land, Hamdan Ballal, was attacked and beaten by Israeli settlers. Israeli soldiers then seized him, and his whereabout are, at this writing unknown.

This is not the typical homecoming for filmmakers who have won Oscars.

Basel Adra, another co-director, witnessed the detention and said around two dozen settlers — some masked, some carrying guns, some in Israeli uniform — attacked the village. Soldiers who arrived pointed their guns at the Palestinians, while settlers continued throwing stones.

"We came back from the Oscars and every day since there is an attack on us," Adra told The Associated Press. "This might be their revenge on us for making the movie. It feels like a punishment."

[UPDATE: Hallal has since been released. Here are details from NPR and The New York Times.]

It seems high time that I post about No Other Land, a documentary I saw a few weeks ago, and one that has weighed heavily on my heart every day since.

I’m writing this review somewhat hastily, as the demands at school have been heavy lately. But I don’t think it’s wise to wait until I have the luxury of a full day to compose this — I’m not sure when that opportunity will come. And this is too urgent an issue for me to wait around.

I’ll start with the obvious — the conflict between Israel and Palestine is so fierce and so complicated that no movie review is going to address it sufficiently. (If you want to quickly educate yourself, here’s a January 2025 BBC News summary.)

And I am not here to claim any deep historical wisdom or to “pick a side” between Israel or Palestine. That would be a show of ignorance. Hamas, the political organization that has controlled the Gaza Strip since 2007, has committed acts of terrorism against Israel and has made statements in the past about aiming to destroying Israel. They have greatly exacerbated the conflict, even though it seems that many Palestinians do not support Hamas or its violence. Meanwhile, the Israelis, whose claims of “self-defense” do not align with their tactics, are following a playbook of genocidal violence against all Palestinians regardless of whether or not they oppose the cruelty of Hamas. And the international community continues to grant them unconscionable freedom to do so.

This doesn’t get fixed by choosing sides. While the dream of a two-state solution seems honorable and the only possible alternative to the ongoing slaughter, it has proven unachievable so far, in part because the leadership on either side seems unwilling to seriously entertain the notion of giving up their grudges over blood already shed.

I make no claim to have a winning strategy to propose. But I am certain that the way forward requires truth-telling.

And No Other Land is a bold investment in truth-telling. We have before us a remarkable document, a personal testimony full of front-lines footage that gives us a detailed counternarrative to the version of the conflict being presented in so much Western media coverage. I suspect I will still be thinking about it decades from now.

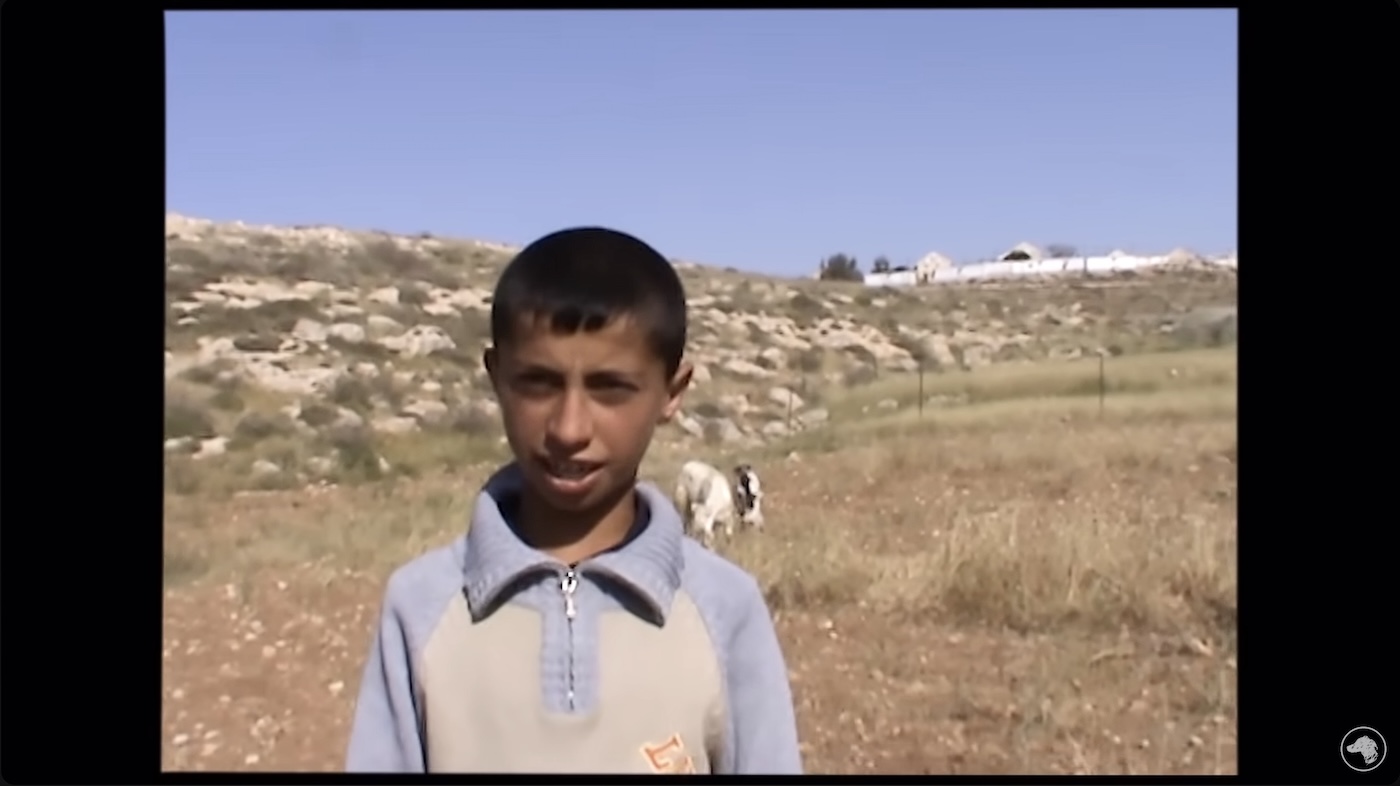

It’s powerful for many reasons, none more affecting than the fact that the filmmakers—a partnership of Palestinians and Israelis—have risked their lives to make it. Palestinians Basel Adra and Hamdan Ballal are crying out for the world to see what is actually happening to Masafer Yatta, the cluster of villages at the southern end of the occupied West Bank. And Israelis Yuval Abraham (a journalist) and Rachel Szor (a cinematographer) see through their own nation’s duplicitous strategies, and they have committed themselves to documenting the violence playing out in front of them over this span between 2019 and 2023.

I brace myself every day for breaking news that these truth-tellers are paying a cruel price for their service.

As one who loves the teachings of Jesus, I feel compelled to recommend this film to you. Jesus teaches us to dedicate ourselves to the work of truth-telling, reconciliation, and peacemaking, and here is a conflict as deep and difficult as any on the planet right now. I think we’re supposed to be involved. But this isn’t just about loving our neighbors. It’s also about accountability. I hope my fellow Americans will see the movie and bear its burdens with me because we are complicit in the crimes unfolding onscreen.

And the violence is undeniable. Anyone with a conscience will feel sick watching bulldozers and tanks move into this struggling neighborhood and start smashing homes, shelters for farm animals, and even active schools which are full of children until moments before the destruction. Mothers and children weep while Israeli soldiers throw all of their belongings out into the dust and then crush their homes. Large families flee into caves where they must survive in cramped spaces. Incredibly courageous villagers host non-violent protests even as the Israeli forces flaunt automatic weapons. We witness baseless arrests and abductions. We witness Israeli soldiers shooting protestors, leaving paralyzed one individual we’ve come to know as part of Basel’s family, and eventually killing another. We watch as Israeli forces take away their cars and their generators, and then cut off their resources for food and even water. (I had to keep reminding myself that I would feel similar rage if I were watching footage of Hamas carrying out terrorist attacks against Israelis — but then I would remember, again, that the Palestinians onscreen are not responsible for that, nor do they have sway with their cruel government.) The Israelis’ claim that they are seizing these Gaza territories “for military training” seems dubious at best (and it is negated by details revealed later in the film). Meanwhile, these villagers are told to leave their homes with “no other land” available to sustain their lives.

The psychological and emotional torture being inflicted on these families in front of these cameras is clearly about more than territory — it’s about hatred and a resolve to erase these people from the earth.

Our heartache will linger with us long after the credits roll, as we watch how this very violence, and worse, continues to play out without any tangible intervention from nations that claim to prioritize peace. You can read testimonies in this IndieWire story of what has been happening since the film started winning awards.

This is the kind of movie that Israeli leadership would hope to prevent us from seeing, as it impresses upon us that the Palestinians are human beings—multi-generational families trying to survive in desperate conditions, and that, while they pose no threat in their simple routines of survival, they are being cut off by violent mobs of Israeli settlers and by the Israeli military from all of the basic resources they need for survival. It is would be hard for anyone to see the violence playing out onscreen and make an argument that these are not the strategies of genocide.

The merit of this work has, thank God, been recognized in America to the extent that, even as the U.S. government continues to supply Israel with weapons to carry out this violence, No Other Land won the Oscar for Best Documentary Feature in February of this year. And that’s only the latest of many accolades from film festival juries and critics around the world. But it has stirred up plenty of controversy, predictably, in America, where some would have us believe that to be moved by the plight of the Palestinians is equivalent to antisemitism. (Just look at the conflict over the film’s exhibition in Florida.) I was fortunate enough to see No Other Land in Seattle during several days of screenings at the Seattle Film Festival’s Uptown Theater. The large auditorium sold out screening after screening. And as the end-credits rolled, we sat in silent amazement, heartbreak, and righteous anger, unable to deny the evils that what we had seen.

I don't know that I have ever felt so empathetic toward those Jews who wanted Jesus to rise up as a revolutionary messiah and lead them in a violent overthrow of Roman oppressors. Had Jesus walked among these Palestinians, I would have wanted to see him lead a fierce resistance to the Israelis... and, in view of their unceasing material and (im)moral support, America. You won't hear me singing patriotic songs anymore. There’s no virtue in fighting evil empires only when that serves your bottom line. The curtain has been pulled back on so many of America’s self-aggrandizing lies, exposing the rot in America's soul. (Evidence of just how our complicity in such horrors is increasing played out in front of us just this weekend.)

But Jesus did answer that call for revolution. Not the way his neighbors wanted him to — but he did. His revolution was to reject outright any engagement in the binary violence, and instead upend the whole game with love. His claim was that suffering and death are not the marks of losing any battle. He did not lash out at the violence. He introduced a grander vision that showed aggression and retaliatory violence are an endlessly destructive and self-destructive cycle, and that there is a grander battle at hand in which love is the ultimate path to redemption and renewal. His way didn't look like victory. It looked like failure. That is, until some caught a glimpse of the idea that death might not have any real power in God's grand scheme, that Jesus was being revealed as more powerful than his enemies could have dreamed, and that those who deal in death are in for quite an awakening someday when the folly and futility of their evils are fully exposed. Spoiler: The last shall be first! The poor in spirit will inherit the earth! The lowly will be lifted up!

Still, this tests my faith as much as any film I've seen. There is, in the fighting over borders, no sign of any hope for progress, reconciliation, healing or peace. But in truth-telling, in small gestures of kindness, in the love of these world-weary activists, there are glimpses of something that transcends time, something that rings true, something that speaks of a country no military incursion has any part in. It suggests that all of this cruelty is a fever that might someday break when we wake from this half-life and behold the cosmos as they really are.

No Other Land is what film critics like to call “harrowing” — and this time, with all of the bulldozers and diggers, the word is more literal than usual. It’s an ordeal to sit through, but an entirely necessary one, because to turn away is to perpetuate the problem. We are called to love our neighbors, not just with donations to their cause, not just with stickers signaling support, and (God forbid) not just with the politicians’ empty “thoughts & prayers”™, but with such clear-eyed attention that we cannot help but be moved and changed by what we behold.

“And when Jesus comes along saying that the greatest command of all is to love God and to love our neighbor, he too is asking us to pay attention,” says the great Presbyterian minister Frederick Buechner. "If we are to love God, we must first stop, look, and listen for him in what is happening around us and inside us. If we are to love our neighbors, before doing anything else we must see our neighbors. With our imagination as well as our eyes, that is to say like artists, we must see not just their faces but the life behind and within their faces. Here it is love that is the frame we see them in."

I suspect that Buechner would have urged us all to see this film. But it’s one thing to see the film. It’s another thing to know what to do next. How exactly should we bear such heavy witness?

Here I am, typing paragraph after paragraph about what I believe to be true, saying the same essential things over and over again about our interconnectedness, our need for one another, our equality. I’m thinking about how I’ve voted for candidates who might have made better choices in order to make a stronger difference, and how I've sent money to various causes. Despite all of these things, it seems like the collapse of hope for these communities just accelerates.

I can turn to the prayers of the distraught prophets and poets, as Jesus did in his own anguish: My God, my God, why have you forsaken them?

I can sing the gospel songs born of persecution. I can lament:

I believe in the kingdom come

When all the colors will bleed into one

But yes I'm still running...You broke the bonds and you loosed the chains

Carried the cross and all my shame, all our shame

You know I believe it...But I still haven't found what I'm looking for.

I can hold in hope to the promises of God within those Scriptures — that, on a grander level than the here and now, the oppressors’ claims will collapse. Those who have suffered injustice will be raised up. And even the most violent and catastrophic deeds of the arrogant and the hateful will be erased, reconciling all of us against their petty and shameful efforts. In the kingdom of God, all such categories that people fight and kill for will be erased and we will be revealed as interconnected, inseparable, equal — a community everlasting.

In the meantime, I can help amplify the testimony of Basel and Yuval. I can make sure their story is seen and heard, and trust that the truth will do its work in hearts that have not yet been hardened.

As another great song goes: “We’re one, but we’re not the same / We’ve got to carry each other.”

Live from New York, it's... a ticking-clock thriller and a tribute to improvisational creatvity!

An early draft of this review was originally published on October 17, 2024,

at Give Me Some Light on Substack, several months before it appeared here.

Subscribe, and you'll read many of these reviews while the films are still breaking news!

I’m apparently not the first to describe Jason Reitman’s Saturday Night as a Muppet movie — that is, its template is the same as many episodes of The Muppet Show, in which Kermit dashes about behind the scenes trying to wrangle his cast of colorful talents into putting on a live variety show.

But while I watched Daniel LaBelle’s performance as SNL’s creator and longtime director Lorne Michaels, I couldn’t stop wondering if Kermit the Frog had been his inspiration. Then I opened Letterboxd and found several critics making the same observation.

And there I learned that I’m not the only one who was distracted by the fact that, while so many young talents are impressively impersonating original SNL cast members, whenever Nicholas Braun showed up in the role of Jim Henson, he seemed to have been instructed to do a hatchet job on that beloved genius, misrepresenting him as a prudish and whiny wimp of a man. Jim Henson, easily offended by risqué humor? Jim Henson, who was famously directed by a studio to ditch his original Muppet Show title: Sex & Violence? What did Jim Henson ever do to upset Jason Reitman that would inspire him to give us this bizarre impostor?

Anyway, I’m not here to condemn Saturday Night. Though I’ll always cringe at the memory of this exasperating injustice, I am, in fact, rather fond of the film. I enjoyed it more than any of Reitman’s work since 2007’s Juno.

With the exception of the Henson misstep, I couldn’t care less about the film’s apparent lack of historical accuracy, which is apparently fueling widespread complaints from SNL superfans. Maybe the Aaron-Sorkin walking-and-talking frenzies that are Saturday Night’s primary mode are fabricating much of how that first episode went down. I’m not bothered. Maybe someone will write to me and persuade me that crimes have been committed here. But so many of the performances are strong, so much inspires my curiosity about What Really Happened, and so many scenes offer interesting tidbits about television history—I’m fascinated.

And the cast is a fascinating ensemble. Like they’ve been asked to play 25 anxious dogs in a doggy day care pen, these young actors are all kinds of fun as they careen, clash, and collaborate. (More than once, I was reminded of those chaotic scenes with groupies and rock stars in Almost Famous.) And some of them are doing brilliant impersonations. I’m stunned by the rightness of Cory Michael Smith as Chevy Chase and Dylan O’Brien as Dan Ackroyd here. And if Kim Matula playing Jane Curtin isn’t quite as convincing in her mannerisms, she still owns her scenes.

In an unexpectedly substantial supporting role, J.K. Simmons plays Milton Berle, who was, at the time of SNL’s launch, a legend and an institution in television comedy. And he’s terrifying. I’ve never read about Berle, and I only remember brief glimpses of his television appearances from early childhood. But this brings me back to The Muppet Movie, where Henson appeared playing a used car salesman who tries to exploit the urgent needs of his Muppet shoppers. Maybe Henson had something right there, sentencing that vulgar egomaniac to a kind of con-man hell.

And in the middle of it all, we have Rachel Sennott—thank God!—as Lorne’s collaborator and wife Rose Shuster. Again, Sennott lives up to and surpasses the hype. She’s quickly establishing herself as the strongest comic actress in her class. And now, more than ever, I want her cast as PJ Harvey in a biopic. (A good one, please. Don’t spoil this.)

As much as I enjoyed Saturday Night, I'm still not yet convinced that finds a strong, meaningful through-line beyond a simplistic Passion of the Visionary plot. Okay—Lorne Michaels took big risks and pulled off an innovative show that struck a chord with its audience in a transitional time, and it’s been a surprisingly resilient formula that has launched a hundred big careers and influenced countless variations and imitators. Sure, no argument there. But the movie doesn’t do much to reveal what exactly earns Lorne any “genius” status. As he’s portrayed here, he seems like a naive dreamer who is in over his head, a gambler making huge bets with a very weak hand, and his only real advantage is a sixth sense for comedic talent. He’s a pinball being batted all over the place and responding with little or nothing that could inspire the confidence of his cast and crew, or that can inspire us to learn from his example.

Gabriel LaBelle holds our attention, nevertheless. He's carving out an interesting path in Hollywood right now, having already played young Steven Spielberg. What legend’s origin story will he star in next? (I can only dream of what would have happened if, when he was a little younger, the Coen Brothers had cast him in an adaptation of My Name is Asher Lev.) He’s fun to watch as Lorne tries to build a successful ship while it’s sailing, bailing out water and patching up holes in desperation, and trying to steer it around the iceberg of Willem Dafoe's NBC executive David Tebet. (I'm telling you, with this film, Beetlejuice Beetlejuice, and Kinds of Kindness, 2024 represents Dafoe Saturation Point. It has got to stop. And based on what I see in the trailers for coming attractions, it doesn't look like it will stop any time soon.)

For all that the film lacks when it comes to wisdom about artistry, it’s still got enough going for it that it rekindles my own creative energy and makes me want to be brave. Based on my limited experience in various creative endeavors—from many years of playing with an improv comedy band to serving as both podcast host and podcast panelist before live audiences—it seems to me that Labelle understands the assignment. I recognize Lorne's determination to keep moving forward even when everything is disintegrating around him, even when the strong-personalities around him seem incompatible. Even though I had barely enough experience to be called an amateur, I planned, directed, and starred in two late-night-style comedy shows in high school, trying to choreograph dozens of my classmates through musical comedy sketches while a restless audience waited to see what would happen next. It was stressful. This movie gave me panic-attack flashbacks.

I’m pleasantly surprised by how much Saturday Night exceeded my expectations. It plays for me like a fantasy, a fan’s fever dream of what that SNL stage and those brainstorming sessions might have been like. It’s served up with such love and enthusiasm, and with such a willingness to admit the rough edges and abusive behaviors and egomanias of its famous cast and crew, that I believe it as it plays out—from its frequently calamitous opening act to its suspenseful and ultimately exhilarating finale. It’s the spirit of the thing that counts, and Reitman strikes the right balance between respect for show-business magic and ruefulness about the rudeness of its makers.

I doubt that the film will cast the same spell on viewers unfamiliar with the show’s early years that it casts on me, but it doesn’t feel like a movie meant to educate us by means of realism. It feels instead like an inventive celebration of improvisational creativity — and, better, a personal expression of gratitude.

And speaking of gratitude, I nominate, for your consideration, the amazing Jon Batiste for Best Original Score.

Carol Kane and Jason Schwartzman bond Between the Temples

An early draft of this review was originally published on September 3, 2024,

at Give Me Some Light on Substack, months before it appeared here.

Subscribe, and you'll read many of these reviews while the films are still breaking news!

Here’s a movie I was certain I would love:

- The trailer got my attention.

- The early buzz praised two actors I have deep affection for.

- It shows no sign of having been crafted for crowd-pleasing or any last-minute revisions due to audience reactions.

- The obvious filmic reference points are all features I either cherish or greatly respect.

I mean, wouldn’t you want to see a movie that was pitched as “A blend of Harold and Maude, Punch-Drunk Love, Lars and the Real Girl, The Big Sick, and A Serious Man, served with some unnerving Shiva Baby sauce and a dusting of The Graduate”?

But alas... very little of Between the Temples worked for me.

The setup is interesting enough: Ben (Jason Schwartzman) is a 30-something widower fractured by the sudden death of his wife, and (like Punch-drunk Love’s Barry) troubled by what appears to have been a life among overbearing women. In his grief and insecurity, he’s lost his voice. Literally: he cannot sing the required ceremonies and services at his local synagogue. He seems stuck in a state of arrested development, unable to navigate, wary of opening himself to new experiences or relationships.

But one day, his childhood music teacher Carla (Carol Kane) appears out of the blue, and he reconnects with a formative influence from happier times — a teacher he respected, a grown woman who may have inspired something like a boy’s first crush. (I’m speculating about that, but I think the film suggests it.) And when Carla decides to show up as an unlikely student in his classes on bat mitzvah preparation, their student/teacher experience is flipped, and it brings them onto strange, new, and equal footing in which they now interact as peers, as friends, and, perhaps… even more? Both Ben’s and Carla’s families and friends are perplexed by his fixation on this new companion (like Lars’s community is perplexed in Lars and the Real Girl). He certainly seems more comfortable with, excited by, and interested in Carla than in any of the young, single women his mothers and Rabbi Bruce (Robert Smigel) are lining up as candidates (just as Kumail’s family parades eligible prospects in front of him in The Big Sick).

As we slowly collect the clues and confessions to understand why Ben is so devastated, we have no trouble believing that he would suffer a crisis of faith and be “disabled” — perhaps permanently — when it comes to relationships.

His trauma is multi-faceted: It’s not just that he lost his wife the way he did. It’s the way she treated him — dominating and manipulating him. And it’s the fact that he's grown up with his mother Meira (Caroline Aaron), and his stepmother Judith (Dolly de Leon) who rarely agree on what’s best for him. He’s become a tangle of nerves and insecurities and confusion. Everybody wants to solve him like a problem. It seems he hasn’t found a safe space within which he can figure himself out yet, much yet figure out what he wants… or who he wants.

Schwartzman has become one of my favorite actors in his work with Anderson. Come to think of it, the first time I ever saw him was in Rushmore, a film in which he’s got a crush on one of his high school teachers. But Rushmore understood that an adolescent boy’s pursuit of his adult teacher is a symptom of immaturity and ill-advised fantasy. Not so here.

If I’m supposed to see Ben’s relationship with Carla as a mutually encouraging friendship that gives them both a safe place to be themselves and grow, I’m all for that. Carla takes him back to a pre-trauma time in his life when he was a boy full of potential. And she pays attention to him in a way nobody else does: with tenderness, with good humor, showing that he offers things she values even as she can help him. But I keep getting the feeling that the movie wants me to hope for a full-blown romance between Ben and Carla, and that means I cringe when I should be caring.

What’s more, I find Ben himself distractingly difficult to read. As Schwartzman plays him, Ben veers between adult anguish and a boyish playfulness, as if he’s reverting to being a child because grownup hardships have proven too much for him. He’s confused, sure—but he’s also confusing. Am I supposed to find his fitfulness funny? That’s difficult when he’s attempting suicide. Am I supposed to be grieving for his loss? That’s difficult when the hints we get about the nature of his marriage are alarming.

As Carla, Kane is radiant, complex, and often a joy here. Has she ever had such a substantial role before? I’d be delighted to see her get some awards attention for this.

Nevertheless, Carla, too, remains a mystery to me. Why is she drawn to Ben? At times the film hints that it might be a sexual attraction, but most of the time it doesn’t. At times it suggests that she’s afraid of the recurring strokes she is suffering, and that this relationship gives her a path of living in denial rather than investigating the causes of her illness. At times it suggests that he’s giving her a second chance to be a mother, and as her relationship with her existing son is less than ideal, perhaps that’s how we’re to read this.

Whatever the case, the movie seems to be teasing us with the idea of a romance, but in its last act, Carla seems perplexed to realize that Ben is thinking of her in this way, and then the question of whether or not they’re headed toward some kind of consummation is abandoned entirely.

Director Nathan Silver and his co-writer C. Mason Wells choreograph a climactic dinner event as epic in its extreme awkwardness as anything in Shiva Baby, and while I think I’m supposed to be laughing at the escalating chaos, it’s hard to find much of it funny when there’s also an escalation of harm: everyone at the table seems likely to hurt someone else, if not everyone else, before it’s over.

Gabby (Madeline Weinstein), the young woman who is pursuing Ben is suffering; her family so eager to see her find a match is suffering; Ben’s moms are suffering. And while I think we’re supposed to see this scene as Ben’s lunge toward a path of salvation, I experience it as Ben’s dismaying surrender to a fantasy. I think I’m supposed to want him and Carla to be together forever in some kind of Harold and Maude “rebellious lovers” mode, thumbing their noses at the restrictive and manipulative system. And the system—that is, this controlling community—seems to deserve that!

But Harold and Maude makes me believe in and root for them; they’re a match that seems strange and taboo until you consider how much stranger and more dehumanizing the world around them has become. Between the Temples aims for something similar. But instead I just feel sorry for these two. I want them both to go to serious therapy.

What a discombobulating picture.

Nine reasons to see Didi

An early draft of this review was originally published on August 30, 2024,

at Give Me Some Light on Substack, months before it appeared here.

Subscribe, and you'll read many of these reviews while the films are still breaking news!

9.

Something’s working when a guy my age is relating so much to a film about a teenager from such a different time, with so many different challenges. Holy handicams, Batman — Didi brings things back! The best moments of my teen years… and the worst.

I’ve never been to Fremont, California, and I was three times Chris’s age in 2008, so the specifics of his day-to-day routines are very different than what I remember of being thirteen years old. And yet, I felt drawn right into that time and place without ever feeling like the film is too excited or show-offy about its period specificity.

I’ve never skateboarded, but Chris’s adventure in meeting and filming skateboarders felt effortlessly authentic.

While I made goofy videos with my friends in high school, they required so much heavy lifting that such adventures were rare, and we had no way to embarrass ourselves in front of the world the way these kids do; still, the creative impulses, the playful escapism, the reckless rebellions that end in regret—all of it rings true.

I’ve never investigated a crush of mine on social media, but watching Chris’s investigative endeavors on MySpace felt weirdly familiar; it’s probably exactly what I would have done in his place at his age. When a movie introduces you to unfamiliar people in an unfamiliar environment and enchants you so gracefully, inspiring such swift and affecting empathy, something is really working.

8.

Didi is the directorial debut of Sean Wang, who shows great promise here. He also wrote and produced it, and he took home the Sundance Audience Award for it. I suspect it’s very personal project for him. “Chris” is a singular character, one that persuades me he must have a great deal of Sean Wang in him. Rather than trying to serve up an “Asian-American adolescence representation film,” Wang give us an intimate focus on an idiosyncratic boy dealing with familiar fears, peer pressures, and family struggles in a way that will feel familiar to most viewers, even as its lived-experience particularity makes every scene interesting.

7.

Along those lines, please note that Zhang Li Hua, the woman playing Chris’s grandmother Nai Nai, is Sean Wang’s actual grandmother. Her presence in the film and her complicated relationship with her grandchildren is a big reason why many are linking Didi to Lee Isaac Chung’s Minari. But that’s a feature, not a bug: Nai Nai’s scenes are some of the film’s most endearing.

6.

Very few coming-of-age films feel as effortlessly absorbing and convincing. My compliments to editor Arielle Zakowski for her efficient, funny, imaginative work here. She has a lot to do with why this movie works. Maybe I should rewind and see Missing after all, just to see what she did with that.

5.

If anybody needs a reminder that A Walk to Remember was a big movie for a lot of teens, well… this is probably the best way to get that reminder. I laughed out loud at the jump-scare of a reference to the film and the part it played in the drama.

4.

Lots of critics are comparing this (favorably) to Bo Burnham’s Eighth Grade… and rightfully so. The trailer made me think it was going to be closer to a dramatization of Minding the Gap, or maybe even a boy’s take on Lady Bird. But I was surprised at how hard this movie goes on the humiliations of adolescence, and Eighth Grade kept coming to my mind as the closest equivalent.

And even as its attention to the fragile bond between Chris and his mother recalls Lady Bird’s slow journey to appreciate her own exasperating mother, Didi takes much darker turns in its last act than I anticipated.

3.

It’s rare that a film like this sticks so resolutely to honesty in its storytelling, with such a willingness to leave conflicts unresolved, at the risk of frustrating those who want a fairytale ending. But that has a lot to do with why I’m still thinking about it days later.

And I’m beginning to believe that it is, at its heart, a film about love — a film about how we grow up needing it for different reasons, but needing it all the same, and looking for it from so many of the wrong people in so many flawed and self-defeating ways. Sometimes we need to make those mistakes and end up hurt, embarrassed, and lonely before we realize what love really looks like and where we’ve been offered some measure of it. While the movie never gives this any formally religious vocabulary, by my lights I can trace God pursuing young Chris through the longsuffering heart of his mother, who is herself lonely and filled with longing to be seen, known, and embraced.

2.

Far too many films about the struggles of adolescence have a protagonist we care about primarily because he’s being bullied and because his parents are awful. Didi dares to let Chris make terrible decisions and treat others (particularly his sister Vivian) badly. So much of what he suffers comes as consequences for his own impulsive choices and audacious lies. Again, wow — I could really relate to this kid.

1.

For Your Consideration: Joan Chen as Chris’s mother Chungsing is the quiet center of every scene she’s in, compelling without ever looking like she’s swinging for those Oscar-nomination marks. As a single mother, Chungsing has clearly suffered unspeakable betrayals and disappointments, but the film doesn’t dwell on that or wring melodrama from it. Her wounds are private, and for the most part they stay that way. When we learn Chungsing is an artist at heart, but one whose creative impulses have been constantly disrupted by misfortune, we might brace ourselves for a predictable story of sudden discovery and success. But Wang is more interested in what the characters do with their suffering than in the causes of that suffering. Chungsing’s is a story of sacrifice driven by necessity, and the moment when her neglected heart is halfway-glimpsed by an unlikely someone and her face blooms with surprise and joy, I nearly choked on a rush of mixed feelings. Oh, to be seen for who we are, not for the roles life has required us to fulfill!

It’s so great to see Joan Chen in this role being so radiant and uninhibited and heartbreakingly human… and with so little dialogue! How many people remember that her face was one of the first images we saw in the opening moments of Episode 1 of Twin Peaks? It’s embedded in my DNA. May this performance open many new doors for her.

Lee Isaac Chung gets carried away with Twisters

An early draft of this review was originally published on August 16, 2024,

at Give Me Some Light on Substack, months before it appeared here.

Subscribe, and you'll read many of these reviews while the films are still breaking news!

Come on — you already know whether or not you’re going to go see Twisters. You’ve probably already seen it. This isn’t the kind of moviegoing option that people lose sleep over, arguing with themselves about its chances of being worthwhile. The trailer makes it clear: This is Dairy Queen Blizzard — a whole bunch of sugar-high hooey whipped up a blender with the primary purpose of entertaining your taste buds. If you like ice cream, you’re going to get your fix of this eventually, either on the big screen or on streaming.

And you certainly don’t need my detailed synopsis. Several hundred such summaries are waiting for you at Rotten Tomatoes or other review aggregate sites. I doubt anybody heard that a sequel to 1995’s Twister was coming and responded, “Oh, I don’t know… I need to read a detailed plot summary before I can make up my mind.” It’s a Blizzard. It’s full of ice cream and bits of candy. It’s a formula. What do you expect?

If Blizzards aren’t your thing, you probably aren’t even reading this review — unless you’ve come hoping to read a stream of entertaining insults. That’s not going to happen. I like ice cream. I do. I’m just picky about it: I like the good stuff. And that can be hard to find.

And, as whipped ice cream beverages go, Twisters… is pretty good stuff.

Full disclosure: I’ve had the unexpected delight of befriending Lee Isaac Chung through a sequence of interviews, including this one that you can listen to at Image.

And I even had the joy of participating in an early script reading of Minari. (I played the Alan Kim part before he did! I played young Isaac!) So I’m rooting for Isaac as he rides this rocket to Hollywood success, even if I’m a much bigger fan of his earlier work—Munyruangabo, Lucky Life, Abigail Harm, and his deeply moving but little-known documentary I Have Seen My Last Born—than I am of big, broad-stroke crowd-pleasers like Twisters.

(I’m posting links to my full series of posts on the films of Lee Isaac Chung at the end of this review.)

So, I’ll do my duty and provide some kind of synopsis. What kind of review doesn’t offer information about the ingredients? Here, in short, is what you’ll find in this summertime sugar-high:

It opens with a typical Trauma Flashback: Kate (Daisy Edgar-Jones) is a weather nerd hell-bent on “taming” tornadoes with new technology. But alas! She and her crack team of storm chasers suffer a tragic, deadly encounter with a wild windstorm. Scarred for life!

Boom! Fast forward: Now Kate works for a weather service, safely indoors, nicely dressed, watching the storms on screens instead of up-close and person. (I’m a little surprised she hasn’t changed course to pursue a quieter line of work—library science, or something.) She’ll have to be dragged kicking and screaming back into the chase.

So, of course, when one of her former teammates—Javi (Anthony Ramos of In the Heights)—promises her a chance to try out some new-and-improved tornado tech, her resolve collapses like an old barn in a gale-force wind, and Kate’s back, baby! She’ll do it… for science!

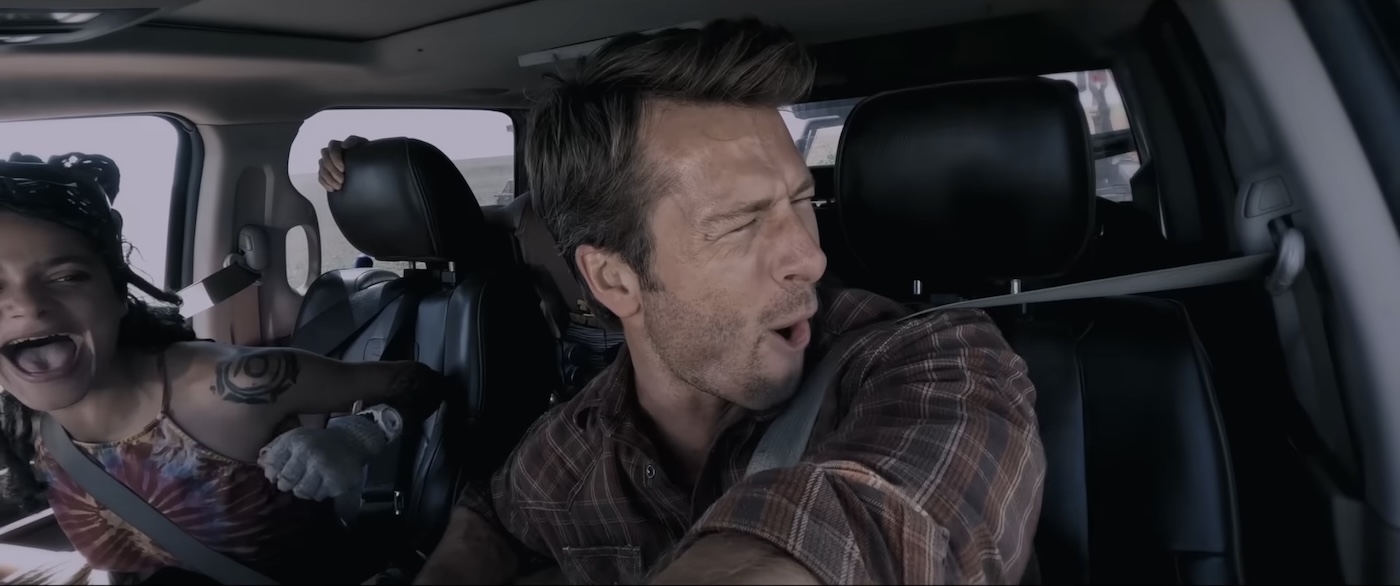

Or, maybe she’ll do it for a muscular cowboy with pecs bulging through his white t-shirt?

Tyler (played by Hollywood’s New Cruise: Glen Powell) is a storm-chaser who’s in it for the thrills and for the subscribers blowing up his storm-chaser YouTube Channel. He might seem like an asshole the way he brags about ignoring science, thumbs his nose at PhDs, and charges headlong into tornados so he can see what happens when he launches firecrackers up their… up their cones, let’s say. I mean, what scientist wouldn’t swoon for a guy who says things like “You don’t face your fears. You ride ‘em!” (Oooh, wow, says Kate. Maybe I’m afraid of Tyler after all!)

Ah, but that’s just one of many ways that this movie is out to surprise us.

Much to the outrage of cliche-fans everywhere, and quite unlike Jan De Bont’s early-90s original, this story is not about a couple of one-dimensional action figures figuring out that they need to be together. It doesn’t abuse audiences, as Twister did, with a barrage of excruciating, sophomoric euphemisms and double-entendres. That film seemed like the most elaborate allegory about erectile dysfunction ever made. When I first saw it in the early ‘90s, I was too naive to realize that all of the "How do you get this phallic device inside the tornado to release all of these little mechanical sperm with their cute little tails?" exposition was really carefully engineered to make this movie both a hot date and and a sex-ed video. At the 30-minute point, Hunt and Paxton are given lines about Billy's "inability to finish things.” You could tell that Cary Elwes was right on the screenwriters' euphemistic wavelength. As his character bragged about his “device,” he looked like he was going to break and bust out laughing.

In Twisters, screenwriter Joseph Kosinski shows some restraint when it comes to serving up audience wish-fulfillment, especially regarding the romance. And he’s so gutsy that some viewers have been ranting as if they want their money back just because they didn’t get pandered to. His sequence of storms raise more interesting ideas. And it deals with those ideas lightly, thank goodness, without ever become heavy-handed or preachy about anything—love, trauma, or even climate change.

(Some are complaining that the movie never mentions global warming, and that’s true. But showing is more effective than telling, and I think director Lee Isaac Chung knows that. It’s obvious that the weather is going all wrong in this movie world, and maybe that’s enough to slow a few folks down long enough to ask why. Climate change deniers aren’t going to have their minds changed by somebody in Twisters shouting, “Gee! Do you think global warming might be a real threat after all?!”)

Before I get to the film’s themes, let’s address what we’re here for: Big, loud, IMAX spectacle. Where Twister could have been called Gyrat-ic Park, with its snarling sneak-attack storms acting like wily predators, Twisters feels more like Jaws. It’s more inclined to attend to the challenge of getting people “off the beaches”—or, in this case, clear of a packed rodeo arena, or away from a vulnerable small town. And it likes the visual of a truck pursuing the monster with a bunch of yellow barrels set to explode.

Where Twister leaned into the monstrousness of the storms, Twisters’ cinematographers, production designers, and animators are more interested in inspiring our awe at the beauty of weather gone wild in these panoramic Oklahoma landscapes. And yet, Chung strikes an admirable balance: he respects the glory of those towering infernos in a way that will please Terrence Malick fans in the audience even as he gives generous, large-hearted attention to the people whose homes are devastated by those very wonders. (When actor David Corenswet stares wide-eyed through a truck windsheld and shouts, “Look at the size of that thing!”, I bark back, “Cut the chatter, Red Two!” My Star Wars reflexes are still sharp.)

What’s more, the cast of characters is much more interesting. It’s easy to imagine that some of them could step to the forefront of a third film, if this one is popular enough.

And, thankfully, Chung and Kosinski aren’t eager to set any of them up as easy targets for contempt. Twister presumed that we were all game to laugh at both therapists and vegetarians. Billy's therapist fiancée was the butt of many jokes, culminating in her preposterous dislike of [checks notes] steak. My, what an abominable human being! And even worse, she wasn’t excited about the idea of throwing her life into the path of deadly windborne debris! What a pathetic excuse for a human being! By contrast, the characters in Twisters — mad as they are for their storm-chasing obsession — aren’t ridiculing other people for their interests or their common sense.

Tyler’s tough and reckless team is made up of actors I’m happy to recognize: from the band TV on the Radio, Tunde Adebimpe! straight from her breakout/Hulk-out role in Love Lies Bleeding, Katy O’Brian! Brandon Perea from Nope! And there’s Sasha Lane doing Sasha Lane things. I'm starting to imagine that her character from American Honey became her character in How to Blow Up a Pipeline… and later she became this character. It kinda works.

Most pleasantly surprising is who they’ve cast to play Kate’s mother: I’m enjoying Maura Tierney’s All-American Mom era. It’s good to see her here after watching her play such a tortured, tragic figure in The Iron Claw.

Most disappointing is how little the movie does with Anthony Ramos. When you see how multi-talented he is in In the Heights, it’s hard to see him stuck in a movie that doesn’t really ask much of him. His job is basically to draw Kate back into the game, seem vaguely tragic in his unrequited attraction to Kate (but he’s just no match for Tyler), and then sell himself out to a corporate interest.

All in all, Twisters is an engaging, amusing allegory for how we need to “tame” America’s storms. Its heroes are seeking ways to quell surges of “wrath,” and they are prioritizing care for those in danger’s path—whether the storm be a pandemic, prejudice, climate change, the pending economic disruptions of A.I., political violence, “Christian” nationalism, or whatever.

Personally, I found it strangely cathartic as I am headed into an academic year that looks likely to unleash some harrowing hardships upon me and my collagues. These are hard times in higher education, harder times in Christian education, and extremely hard times for Christian educators who care about history, science, the environment, social justice, and loving their neighbors without prejudice. The storms of racism, nationalism, and anti-intellectualism, along with the systemic abuses of patriarchal hierarchies—these are the tornadoes laying waste to institutions that have the potential to provide meaningful service and inspire lasting change. I wish I could protect strong academic programs with those anchor-rods like the ones Tyler uses to secure his truck to the earth as the storm advances. But ignorance and fear are powerful storms, and if you care about truth and love, you’re going to suffer a lot of loss in this world.

Maybe that’s why I found myself surprisingly susceptible to Twisters’ charms. It was genuinely encouraging to see people with very different philosophies and mindsets working together for the good of the vulnerable and the poor, embracing the gift of science, and facing — maybe even riding — their fears. That’s the kind of vision that Lee Isaac Chung brings to his meditative arthouse films, his Oscar-winning personal storytelling, and now, his first summertime blockbuster.

Here’s hoping the success of Twisters gives him all the resources he needs to make whatever movie he wants to make next.

Okay, I’m gonna say it: Next time I see Lee Isaac Chung, I want to give him a high five for showing heroic restraint and not fulfilling the kissing fantasy so many people need here. That would’ve made the movie about something it wasn’t. Love is about listening to the person in front of you so much more than lip-locking. And I felt that here. I respect both Kate and Tyler more for staying focused on the most important matters at hand. Leave the shallow fantasies to fan fiction.

Here are links to my five-post series on the films of Lee Isaac Chung at Looking Closer: Day One, Day Two, Day Three, Day Four, Part Five.

Kings of infinite space: Inmates of Sing Sing stage a prison break through art

An early draft of this review was originally published on August 14, 2024,

at Give Me Some Light on Substack, months before it appeared here.

Subscribe, and you'll read many of these reviews while the films are still breaking news!

“The glory of God is man fully alive.” Have you heard that before? It’s a quotation attributed to St. Irenaeus, and it has become a popular way of saying that when human beings live up to their potential we glimpse a revelation of the Divine. Unfortunately, like so many catchy lines in the social media age, the line has been ripped from a very particular context and, thus, sorely misinterpreted.

Nevertheless, there is something true in the botched, popular interpretation. Nothing makes me believe in God more than seeing someone exercise the capacities that set human beings apart from other living beings—the distinctive unity of the mind and the heart; the power of the conscience; the extravagance of the imagination in the achievement of art; the ability to break cycles of violence through suffering, sacrifice, and forgiveness. We can usually tell the difference between a real human, a dynamic entity alive with mysteries and contradictions, and an artistic representation of one. So it’s a rare and wonderful thing when an actor suspends our disbelief and moves us by bringing to life a character who is complex, convincing, and compelling.

I thought of the St. Irenaeus line while watching Sing Sing. While movies about the power of art to change lives are common, and far too commonly formulaic and sentimental, Sing Sing is better than most. One reason for that is that has roots deep in a real-world story: Sing Sing is based on the lives of real prisoners participating in a real arts program—Rehabilitation Through the Arts (RTA).

Further, the film features men involved in this program—some still incarcerated, some free—playing themselves. They’ve lived this story, and the authenticity they bring to the project shows.

And, much to my surprise and delight, director Greg Kwedar — he wrote the screenplay with Clint Bentley, took counsel from some of the men that screenplay concerns, and drew from a 2009 Esquire article on RTA—shows remarkable restraint through almost all of the film’s dramatic and emotional scenes. On only a couple of occasions in the film do I feel the filmmakers’ energy focused on moving moviegoers’ to strong emotion. If you’re like me, you have an allergy to heavy-handed tactics—extreme close-ups on exaggerated expressions, huge swells of dramatic music, and all the tools of sentimentality that trigger conditioned responses instead of earning authentic emotions. Instead, Kwedar’s attention is focused lovingly and respectfully on the complicated men themselves: their strengths and weaknesses, their idiosyncrasies, their specific histories and hardships and hopes.

And because of that, I’m inclined to say that I was moved by sensing God alive and at work within their midst.

Uh-oh, a reader somewhere is saying. Is Overstreet going to get all religious on us? That is, I suppose, a fair reaction. But before you bail on the rest of this review, let me explain what I mean whey I say that I sense “God alive and at work” in this film: