An early draft of this review was originally published on August 3, 2024,

at Give Me Some Light on Substack, months before it appeared here.

Subscribe, and you’ll read many of these reviews while the films are still breaking news!

They can have their Summer of 2024 Godzilla-versus-Kong madness. I’d invite you to meet me the smaller theater down the hall where I discovered an altogether different and so much more satisfying match-up: Olivia Colman versus Jessie Buckley. They do not disappoint!

Even more impressive: This outrageous clash of complicated characters, played by two of the big-screen’s best actors, is based on a true story.

My review comes too late for you to catch this in a theater as I did. But you can, at the moment, find Wicked Little Letters on Netflix (if you’re still a subscriber) or rent it from a variety of streaming platforms (if you’re not). And I encourage you to do so.

Moviegoers probably won’t remember Wicked Little Letters for its elegant cinematography (although Ben Davis also shot Doctor Strange and Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri), or even for Jonny Sweet’s sprightly screenplay. Nor will they come away talking about the thing that the trailers emphasized: Colman vs. Buckley in an epic brawl of slurs and expletives. While the marketing made the movie this look like an old-fashioned British farce, with all of the actors clowning for the camera and cussing up a storm, and everything delivered in big, broad, crowd-pleasing punches, director Thea Sharrock (Me Before You, The Hollow Crown) takes this to much more interesting places and gives us much more to think about. Thus, moviegoers will most likely remember it for two other reasons: a fantastic ensemble of the UK’s best and a revealing story of the damage done with oppressive societal and religious hierarchies.

Sure, the elevator-pitch version of the story delivers as promised:

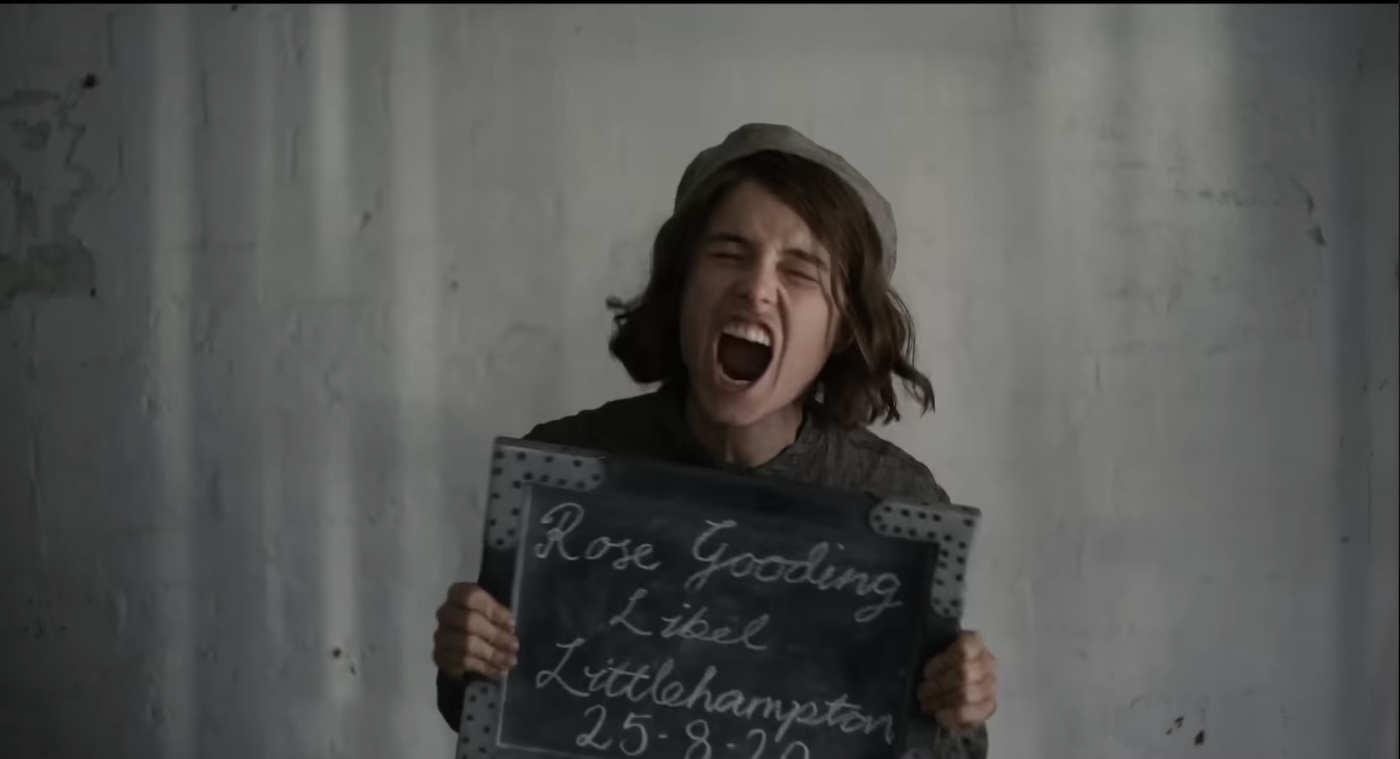

This is “based on a true story” of a town called Littlehampton where, in the 1920s, residents were scandalized by vicious and profane letters from an anonymous assailant. In particular, Edith Swan (Olivia Colman) is targeted by the obscene tirades. Edith is an anxious but well-respected spinster who lives with her heavy-handed and religiously zealous father Edward (Timothy Spall) and her softspoken mother Victoria (Gemma Jones), and though Edith believes that willfully and quietly suffering such abuse counts as righteousness, eventually they decide to get the police involved. In their prejudice and haste, the family has set their sights on their neighbor Rose (Jessie Buckley), an Irish migrant raising a child on her own, as the most likely culprit.

And right away they have a fight on their hands. A battle of crude outbursts erupts between neighbors, causing great civil unrest. And meanwhile, the titular letters just keep coming.

Not all of it works. The police officers may as well be jokes tumbling out of a clown car. They’re more interested in checking a box marked “SOLVED” than they are in discovering the truth. And this frustrates a rookie cop, Gladys (Anjana Vasan), who has smart suspicions about the nature of the crime. Like Rose, Gladys is an easy target for those who think diversity is a dirty word, and this adds energy to her intuitions. Still, everyone in aspect of the film seems to exist in a familiar genre of manic British comedies. They could step from this big screen onto one that’s playing Edgar Wright’s Hot Fuzz and feel right at home.

Don’t get me wrong — I love wacky British comedy. But Olivia Colman, Jessie Buckley, Timothy Spall, and Gemma Jones are, by contrast, acting in a more ambitious and nuanced film that has a surprisingly dark undercurrent: Wicked Little Letters is, ultimately, about what comes from resentment and disease that festers in the heart when we’re forced to survive in a system that is fundamentally rigged against outsiders, the poor, and the vulnerable. It’s about how ugliness of the heart, buried beneath layers of false righteousness, will manifest in destructive ways.

Wicked Little Letters looks and feels more like a made-for-TV endeavor than something framed for the big-screen. But I’m so glad I trusted my gut, got to the theater in time, and experienced it with a crowd that loved it and laughed hard together. I may have been the only man in the theater; I wonder how it would have played if that were different. So, while you may not have that chance, I’d encourage you to watch it with friends and family (so long as they’re up for some comically severe language).

And the great Timothy Spall, who barely figures in the film’s marketing, is as strong as anyone here: The man does more with his grumpy-old-man role, playing Edith’s curmudgeonly father Edward, than an audience has any right to expect. He’s fearsomely incredible here as a man behaving monstrously. Playing his wife Victoria, Gemma Jones does wonders with a very small role.

The focus on religion on Jonny Sweet’s screenplay is unexpected and welcome. This becomes (inadvertently, I expect) a study of how the glory of the Gospel can so easily be distorted into just another form of moral legalism — the opposite of what the actual Gospel literally is: good news for the poor, the outcast, and the vulnerable. It’s a psychodrama about how piety begets mania and corruption.

And as such, it rings very true. I grew up around, witnessed up close, and participated in the sick and twisted manias that grow like tumors in communities of religious self-righteousness. So I felt sick — and for sins of my past, complicit — through a lot of the film’s running time. It felt too familiar, too real. How often did my evangelical community condemn those who use harsh language without ever humbly and attentively investigating what horrors might inspire such language? Where love and grace are secondary to strict moralism and judgment, you may hear Jesus’s name being praised, but believe me — he’s not there.

While I was worried that the conclusion of Wicked Little Letters would feel trite and preachy, our last glimpse of the troublemaker responsible for the crimes really surprised and moved me. (I wasn’t expecting to think back on various portrayals of the Joker as the credits rolled!) I’m going to be thinking about those dreadful, shadowy moments and that laughter for a long, long time.