An early draft of this review was originally published on July 31, 2024,

at Give Me Some Light on Substack, months before it appeared here.

Subscribe, and you’ll read many of these reviews while the films are still breaking news!

I must begin with high praise for the restored SIFF Cinema Downtown — ye olde Cinerama, where I’ve seen so many of the greatest widescreen movies ever made over the years. 2001: A Space Odyssey, Apocalypse Now Redux, Close Encounters of the Third Kind, Blade Runner (the original and the director’s cut), a special screening of Punch-drunk Love with special guests Paul Thomas Anderson and Adam Sandler (who sat behind me), every Lord of the Rings movie on their opening weekends, and now… Furiosa: A Mad Max Saga.

This theater, with its massive, panoramic big-screen experience, is sacred ground for Seattle moviegoers. It felt like a heart attack to the Seattle arts community when it closed. How could we let this happen? This was supposed to be the platonic ideal of a movie theater, and its reputation was so great that filmmakers would go out of their way to see their movie projected on this screen, in this context!

Today, thanks to the Seattle International Film Festival’s bold investment in the future of Seattle’s moviegoing community, the place looks great. The chocolate popcorn is still scrumptious. And big movies like this one are just awesome to behold here. The surround-sound is so sharp that when someone in Furiosa spoke from offscreen far to the right, moviegoers’ heads across the auditorium swiveled as if someone in the back of the theater was shouting at the screen.

I am so, so glad it’s back. For now. But it will only remain if moviegoers seize the opportunity. I hope they will. Whatever complaints I may have about Furiosa, please keep in mind that I had a fantastic time at the movies, and I wouldn’t hesitate to go back for more.

Okay, let’s begin…

George Miller has been one of dystopian sci-fi’s giants in the medium of cinema since his second Mad Max film. The Road Warrior gradually won him a large audience and woke moviegoers up to the fact that he was trailblazing futuristic storytelling in unexplored territory. In the ‘80s, the big screen had seen nothing like this.

But I don’t think anybody anticipated that Miller’s escalation of the spectacle he’d started in 1979’s Mad Max were only the beginning of a saga that would grow exponentially in story and in scale. (And I never would have guessed that, in doing so, he would leave behind Mel Gibson, the superstar he’d created.) If you’d told me that those two would seem gentle in comparison to what was ahead, that the series would become increasingly acrobatic and extravagantly violent, we might have wondered if moviegoers were capable of taking much more sensory overload.

What’s more — I don’t think anybody anticipated just how profoundly prophetic this mash-up of a three-ring circus, a freakshow, and a monster-truck show really was. Back then, we’d watch Max and the Gyro Captain take on The Humungus and it was like watching professional wrestling in some bizarro nightmare. Now, we nod at what we’re seeing, reading it as an obvious allegory of just how rapidly the corporate ganglords of Planet Earth are burning up the ground beneath their feet.

Let’s review what’s happened in the years since 1985’s Mad Max: Beyond Thunderdome wrapped up the Gibson era.

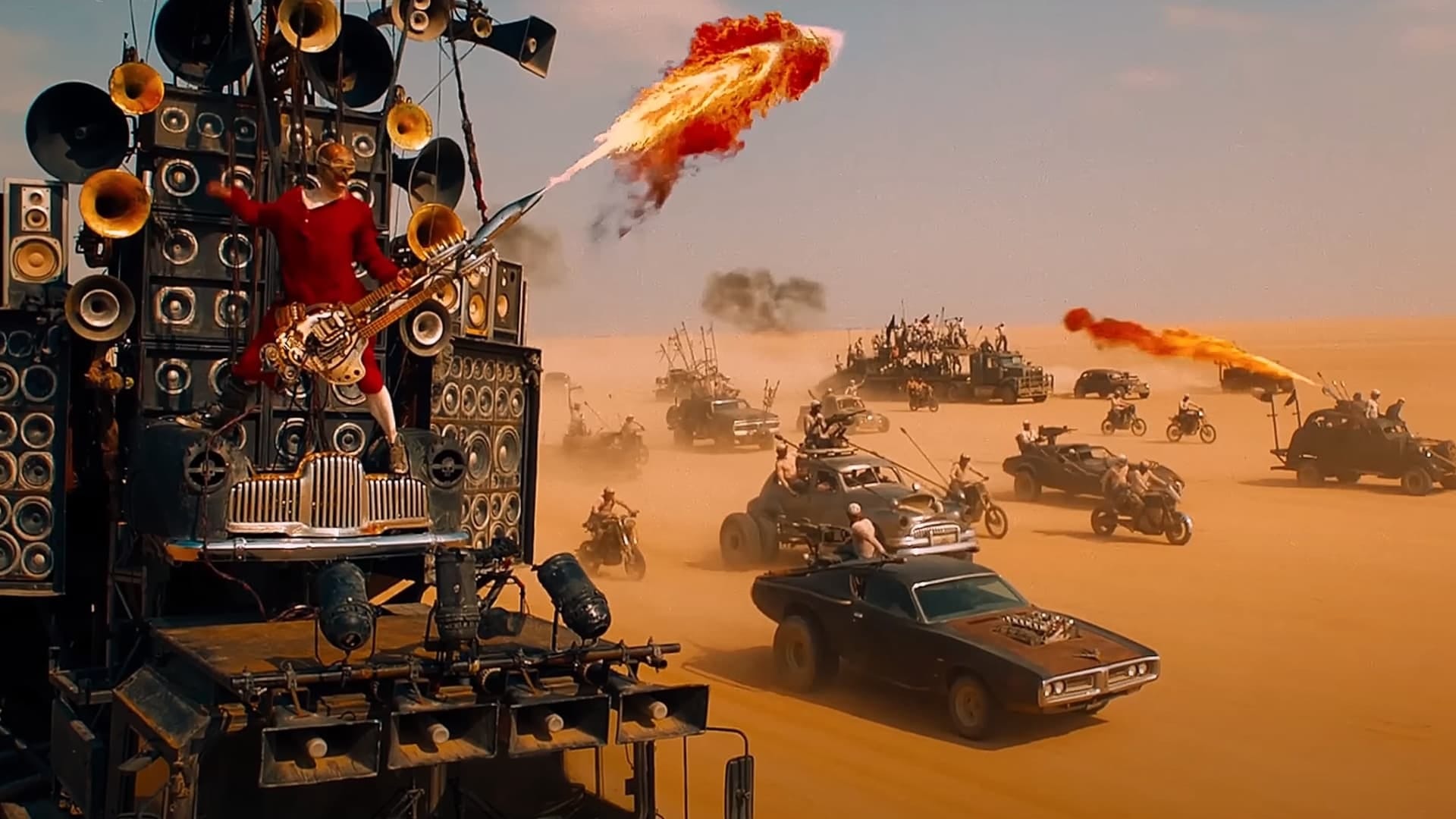

In 2015, after 30 years of playing in other genres, Miller went back to Australia’s most original big-screen mythology and gave us Mad Max: Fury Road, which is now regarded as one of the greatest films — some call it the greatest — of the 2010s. With unprecedented live-action stunt work and awe-inspiring practical effects, Miller made widescreen adventure filmmaking enthralling again for the first time since Peter Jackson’s The Lord of the Rings. The volcanic eruption of this one film made the MCU movies look like toys pumped out by vending machines: artificial, superficial, lazy, and fake.

In Fury Road, we returned to a world of barbaric tribalism, in which grossly amplified male egos were burning the planet, torturing and enslaving women for sex and for male offspring, and voraciously consuming essential natural resources to power their fleets of customized war trucks. Two vigilantes — Max (now played by Tom Hardy), a wanderer, and Furiosa (Charlize Theron), a rebel deeply embedded in enemy territory — ended up joining forces to break away from the tyrant and slave master Immortan Joe and help some of his sex slaves escape. As these spectacularly violent frenzies played out, Furiosa slowly moved to the center of the drama. Haunted by a memory of a lost paradise, a world in which human flourishing had been possible, she captured our attention and our empathy. For all of the roaring engines, explosions, stunts, and flame, throwing, the most iconic image in Fury Road remains a simple and panoramic shot: Furiosa falls to her knees in the open desert and unleashes an anguished scream, realizing that there will be no going back to the world she remembers and loves.

At the time, dystopian science fiction was already at flood stage. The fever for Katniss’s rebellion in The Hunger Games was breaking, and John Hillcoat’s big-screen adaptation of Cormac McCarthy’s The Road (which I rather liked) had come and gone without getting much more than shrugs from moviegoers. (In retrospect, Hillcoat’s film looks like a dull prologue to the long-running success of television’s The Walking Dead.) Today, audiences would be justified in complaining that they’ve reached a big-screen dystopia saturation point. The genre dominates film, television, games, YA fiction, and graphic novels. Many of these stories focus on traumatized survivors who must venture through wastelands and wildernesses, at great risk to themselves, in the hopes of overthrowing the Powers that Be, or the hopes of finding a better world. As a professor of creative writing, I can tell you that many of my students, so scarred by the way the pandemic disrupted their high school experience, struggle to imagine stories in any other genre. It’s almost all they know.

My first experience with a story like this came early in childhood, when I discovered Watership Down, Richard Adams’ apocalyptic novel of rabbits striving to survive in a brutal wilderness, one fraught with predators and “governed” by the most destructive and heartless species of all. (You get one guess.) And yet, in the rabbits’ pursuit of a world that seemed meant for them, I felt something distinctly human at work: a longing for paradise, a deep-set sensibility that we are meant for a better world. The prevailing impression of that story is one of tremendous beauty and hope.

Thus, I am troubled by the proliferation of dystopian stories that seem to exist to indulge horrific possibilities without much imagination for beauty, hope, or healing. In recent years, such stories and franchises seem to insist that they are relevant to our present circumstances and prophetic of the very near future. I’m not troubled that people are writing them: A society’s collective nightmares reveal a lot about the state of our health. But I’m troubled that they make me feel like we’re sliding, inevitably, into a reality very like these nightmare visions.

And indeed, reading the news, feels increasingly like reading and dystopian sci-fi. The reality of climate change, for example, paired with the dismaying denial of this very phenomenon by those who are accelerating its destructions — these are enough to trigger despair. What’s more, such self-destructive trends can inspire a righteous rage in younger generations as they find themselves doomed to suffer the consequences of the willful denial and cruel selfishness of their elders. We who have neglected the consequences of our selfish consumerism for so long have robbed our children and grandchildren of so much goodness that the world was designed to provide.

Miller’s vision of a wasteland ruled by hyperviolent gangs, their bikes and cars and sixteen-wheelers customized for open road warfare and off-road races, is both viscerally thrilling to watch and deeply troubling to contemplate, especially as we have to admit that there are parts of the world in which apocalyptic tribalism is present-day reality. The monster trucks that soar and crash and rumble across his blazing panoramas might symbolize unchecked human hubris; a rampant, ravenous, and steroidally distorted masculinity; a fury born of — what? A starvation for love? And his movies reek with the scent of scorched gasoline, touched with the madness of present-day politicians who have made “Drill, baby, drill!” a rallying cry.

Now, a decade after Fury Road set fire to our screens, we have Furiosa: A Mad Max Saga, the origin story of Fury Road’s rising star. We already know that she will grow up to save a few of Immortan Joe’s sex slaves, and that she will give the world a chance to try and salvage what time, resources, and hope remains. This new film serves up many of the open-road action sequences that the franchise fans have come to see. But this isn’t just road-warrior chaos: Furiosa is much more Dickensian in its storytelling.

While I’m tempted to agree with those who say this chapter of the saga is entirely unnecessary — I’m more interested in what happens after Fury Road than what led up to it — the story that unfolds here is compelling enough to justify its existence. As the world’s wealth and power becomes increasingly consolidated and controlled by fewer and fewer entities, we need stories about how the weakest and most vulnerable — in this case, an orphan with nothing but anger to get her through — might find ways of overpowering a superstructure. Or at least permanently compromising it structural integrity.

This time, we follow the story of a waifish child who witnesses indescribable horrors, including the brutal execution of her mother at the hands of a barbarian gang lord named Dementus (a delightfully batty Chris Hemsworth). Taken captive, Furiosa fights for a chance to escape and ends up among the ranks of the wasteland’s most powerful and sinister overlord: Immortan Joe. There, she tries to earn favor and opportunity in order to plot her revenge. With cleverness and daring, she joins forces with another disgruntled agent, Praetorian Jack, The Souvenir’s Tom Burke), to wreak vengeance on Dementus and escape the whole hellish system. Her promise to her mother echoes in her mind: Find a way home.

Because we know how Fury Road begins, with Furiosa still laboring under Immortan Joe’s iron fist, we know that this Furiosa story cannot end with victory. So the fundamental suspense of this film lives in questions about how — or if — the storytellers will deliver a satisfying conclusion. This was, for me, a compelling reason to see the movie early enough to avoid spoilers. Fury Road had given us so many questions: Where does such a woman as Furiosa come from? How could she have any agency in a city governed by a monster like a Immortan Joe? How could she hope to pull off her getaway surrounded by such vicious predators? Where did she learn to drive like a maniac? Why is one of her arms robotic? What drives her? How has she not been driven mad?

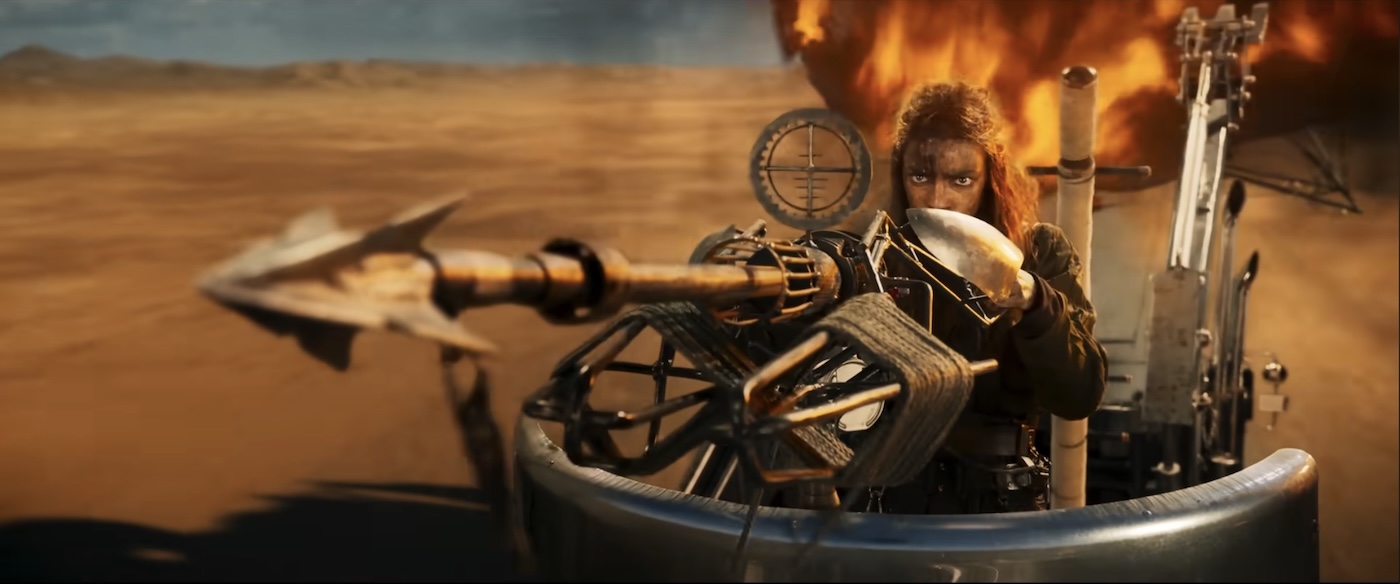

I was frustrated to find that Charlie Theron would not be the lead in this film. Her Fury Road performance was nothing short of extraordinary — sci-fi epic acting as an Olympic sport. Theron had the strength, intensity, and athleticism to make us believe that Furiosa had grown up in that world. She almost stole the show from Tom Hardy — not an easy feat — making Furiosa the equal of Mad Max in every way.

But when we realize that this prequel focuses on a much younger Furiosa, it makes sense that Miller chose 13-year-old Alyla Browne and the ubiquitous Anya Taylor-Joy to represent the character’s journey from early childhood to young womanhood. (Digital animation is employed here very cleverly, trying to make the handoff from Browne to Taylor-Joy seem seamless.) To my surprise, it’s easy to suspend disbelief and accept these two as the earlier versions of Theron’s character. Much of that has to do with Taylor-Joy’s full-bodied commitment to suffering Furiosa’s ordeals, developing her physical prowess, and convincing us that she can drive like a bat out of hell. (Perhaps you’re old enough to remember the thrill of seeing Indiana Jones maneuver beneath a truck that was running at high speed on a dirt road. Wait until you see what Furiosa can do in similar circumstances!)

As Furiosa spends much of the film wearing masks of face paint and dust, Miller wisely and effectively exploits Taylor-Joy’s cartoonishly large and expressive eyes to anchor our empathy in her suffering. And, as Furiosa rarely says anything in this film, that is an achievement. I find it easy to stay focused on her in every scenario, and the film loses some of its electrical-storm energy whenever she’s offscreen.

Eventually discovering an ally in Praetorian Jack (The Souvenir’s Robert Burke), a driver who is angling for escape, Furiosa survives an appalling and exhausting sequence of ordeals that cost her severely, including the battle in which she loses the arm that is replaced (we know from Fury Road) with a robotic appendage. (It’s one of the film’s most frustrating stumbles that we come away without any clue as to how she gets that arm working or becomes so comfortable using it.)

I was hoping we would get, along the way, a more complex and revealing exploration of Fury Road’s not-so-subtle critique of Western civilization’s cruel cocktail of capitalism, white supremacy, and toxic masculinity. And Miller delivers some of this. In his vivid aesthetic, whiteness is intensified, standing out in stark contrast to any living color: the vibrant oranges and reds that dominate the landscape, the greens and blues that dominate glimpses of the last world. Immortan Joe’s chalk-white skin and streaming white mane seem to represent a divorce from human nature — all that is natural, earthy, healthy, and brown. Joe’s minions paint themselves the same chalky white, whether to imitate him or to absorb some intoxicant, it’s hard to know from just watching the film. The effect is ghastly. It seems like the brand of a death cult, employed to inspire fear. Perhaps we’re to draw from this a parallel with the surging currents of white supremacy. I’m not sure. (Is it just me, or do Immortan Joe’s sons seem like steroidal lampoons of Trump’s sons, Don Jr. and Eric?) But the film doesn’t seem very interested in exploring any such insinuations.

Fury Road made clear that women in this world of maximal misogyny have been reduced to the role of sex slave. This, too, seems to mirror how “conservative” political forces — most obviously in America — are aiming to turn back the clock on the women’s movement and confine them to cooking, cleaning, and mothering (at best), which will also enabling and excusing abuse and exploitation. (See almost any report on J.D. Vance and his history of opinions on women.)

Another of Miller’s relevant critiques comes in the film’s treatment of Dementus as a sort of antichrist. Note how the first time we see Hemsworth onscreen, he’s cloaked — literally — in White Jesus iconography. I couldn’t help but find myself thinking how easily persuaded so many American evangelicals would be by Dementus, with his fondness for opening his arms in a cruciform pose and promising worldly prosperity, all while engaging in flagrant violence against anyone who gets in his way. (In view of how the film concludes with a perverse reimagining of the Eucharist — “This is my body. Take, eat.” — I think Miller is going out of his way to lampoon what American evangelicals have made of Christianity.)

Clearest of all are the film’s pessimistic but not unrealistic prophecies about consumer culture. By organizing the chaos of the wasteland’s warring gangs around the exploitation of water and gas and bullets, Miller gives us an easy-to-read allegory about the inevitable destruction brought on by capitalism that is unchecked by conscience. We can see what the world becomes when we give power to trigger-happy, power-hungry agents whose masculinity has become a monstrosity.

But for all these striking visual contrasts, a subtle thread seems to be missing here. By focusing so intently on all that Furiosa has lost, and all of the crimes she and the world around her have suffered, Miller’s energy seems focused on whipping audiences into a frenzy of vengeful rage. Furiosa is hailed in this film as “the darkest of angels,” exalting her as a sort of John Wick-type figure who will stop at nothing to kill anyone who gets in her way. She is an agent of slow-burning and calculated revenge.

At the film’s climax, the action slows for an unexpected and promising dialogue between hero and villain that makes me believe, for a few sweet moments, that the conclusion might take a turn toward wisdom. And I’ve seen some critics try to argue that it does. I’m not sure I buy that. The resolution we get, while it may not unleash the kill-shot and the fountains of bloodshed we might have expected, is still designed to fulfill audience revenge fantasies. It’s an outcome that we might argue is even more cruel than an execution.

“What did you expect, Overstreet?” That’s what I anticipate I will hear from some readers. “Did you expect love and mercy to win the day in a story that delivers us to the bleak beginning of Fury Road?”

No. But I suspect that braver imaginations might have found a way to something wiser and healthier for moviegoers who are facing dystopian futures.

I will gladly watch whatever Miller does next. Nobody makes movies that stagger the imagination like he does. (I can’t help but wonder what a saga like Star Wars might have become if a master like Miller hadn’t taken it higher as visionary cinema. Instead, we saw it sprawl and devolve into endless streaming-series variations.) The artistry on display here makes most MCU movies look like disposable television. In every wild scenario and in every quiet moment, Miller’s asking, “What is the most interesting angle on this action? How can I use the whole screen without ever distracting viewers from the action’s focal point?” It’s a joy to see his formidable community of artists at the peak of their filmmaking powers in every aspect…

… except, alas, the most important one. Miller’s saga shows us very clearly so much of what is wrong with the world. But do these storytellers have any sense of what is worth saving, and why? Do they have any idea about what might make a meaningful difference beyond retaliatory violence? I have to hope that, in the grand scheme of things, Miller will either bring this apocalyptic saga to a more substantially hopeful conclusion, or, if that’s not in the cards, at least arrive at a profound reflection on the ultimate futility and emptiness of perpetual violence. I’m with Steven Greydanus, who has written at U.S. Catholic one of the best pieces about this movie I’ve yet seen. On its own, Furiosa is a dazzling but punishing experience, one that gets audiences cheering for the vengeful violence of “the darkest of angels” rather than appealing to “the better angels of our nature.”

It is true that such bleak world-building and such cruel circumstances as the Furiosa scenario are unlikely to leave much room for examples of love and mercy. Few storytellers could convince us of the existence of a gentle, civil, gracious soul surviving in such a wasteland and making a meaningful difference. (Again, Cormac McCarthy remains a vivid exception. His novel The Road may not lead us to any glorious hope, but the pleasure of that book is not its violence but its poetry, and that in itself is worth discovering.)

Miller’s saga shows us very clearly so much of what is wrong with the world. But do these storytellers have any sense of what is worth saving, and why? Do they have any idea about what might make a meaningful difference beyond retaliatory violence?

But fantasy, more than any other genre, can do this: It can give us glimpses of possibilities beyond the sphere of our grim experience. It can take our breath away with rumors of glory that beam in from beyond the frame, the frame that we’ve come to believe is the limit of all hope. Tolkien, Lewis, L’Engle, and even Lucas knew this. Here’s hoping Miller does too.

It seems within the range of Miller’s talents to achieve this. After all, this is the filmmaker whose most admirable masterpiece, by my lights, remains his all-ages adaptation of Dick King-Smith’s classic children’s story Babe — a singular joy, radiant with goodness.

And, to his credit, Miller does give us fleeting glimpses of human kindness. Between Furiosa, Praetorian Jack, those they help, and a few who help them along the way, we can recognize seeds being smuggled into the darkness, seeds that might someday, against all odds, make possible a garden in this desert. What sticks with me from this movie as vividly as that image of Fury Road’s screaming Furiosa are the words of Praetorian Jack as he reflects upon the fate of his parents: “Even as the world fell, they longed to be soldiers for a virtuous cause. For them, it never happened.”

Perhaps there’s some comfort in that fact that Jack and Furiosa, if they fall, will fall fighting for “a virtuous cause,” even if their efforts seem doomed to fail.

What would it look like if all of these creative, passionate, innovative imaginations conspired to give us a final act that gave us all a vision for a transformed world? What if this were a saga not merely about survival and revenge, but also about redemption? I suspect that such a marvel would elevate the whole series. And it would mean so much to those of us who long to strengthen what’s left of our increasingly dystopian world.