An early draft of this review was originally published on December 12, 2023,

at Give Me Some Light on Substack, months before it appeared here.

Subscribe, and you’ll read many of these reviews while the films are still breaking news!

As my friend and I paid for our tickets to see director Todd Haynes’s new film May December at my neighborhood theater, the ticket-taker shared, as if divulging a secret, that some of Mary Kay Letourneau’s family had been there the previous day to watch the movie and judge its accuracy.

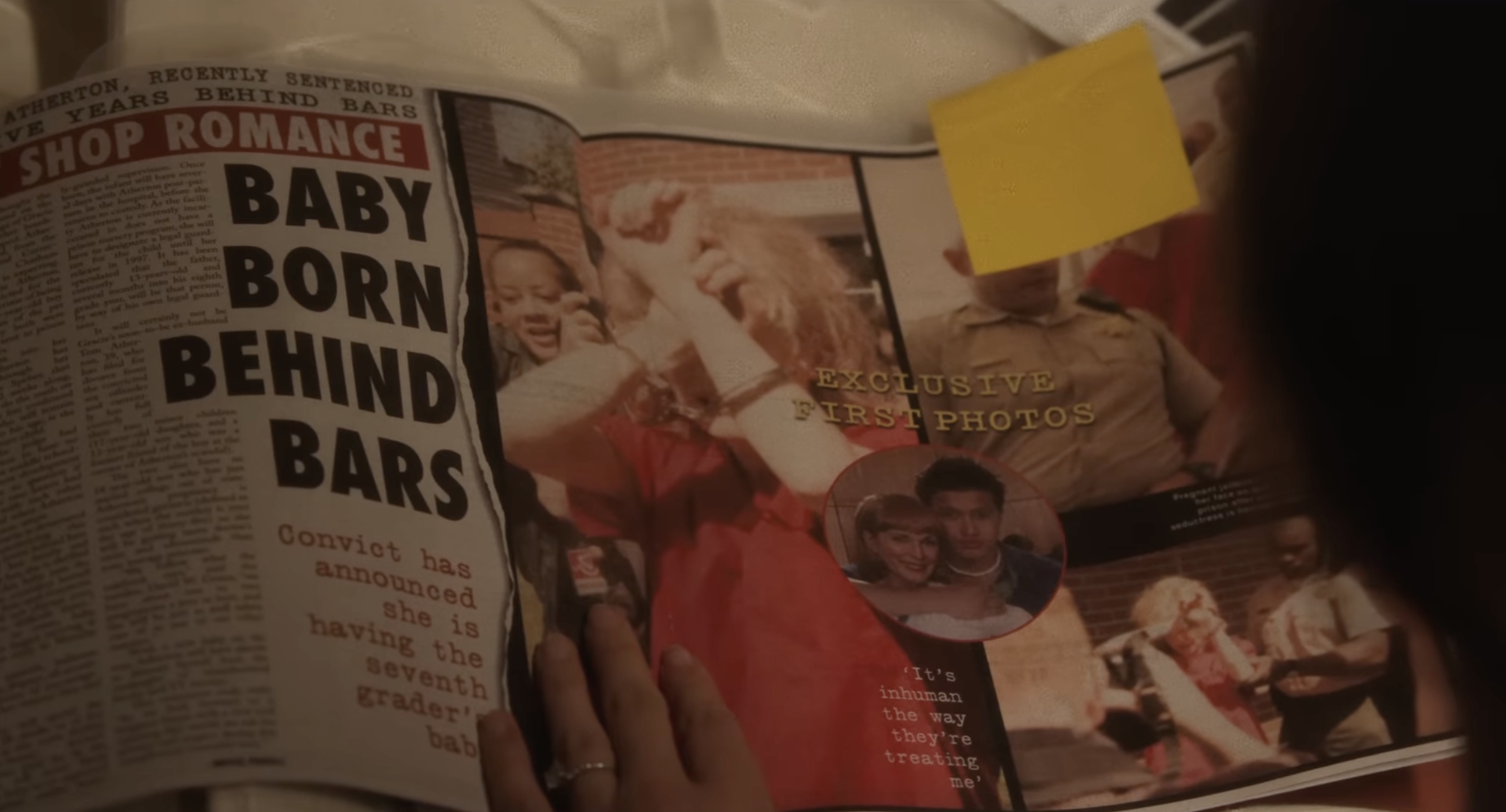

I suppose that’s possible. Schoolteacher Letourneau’s crime of raping one of the 12-year-old sixth graders in her class, which made her a star of tabloid headlines, took place just south of Seattle.

Still, I worry about anyone who buys a ticket to May December thinking it will offer them any insight into those actual events. The screenplay — the first feature for Samy Burch — is a work of fiction only very loosely inspired by the Letourneau scenario. Burch turns the fundamental details into… what, exactly? A complex psychological thriller? A satire of daytime soap operas? A horror movie? Whatever May December is, it has far more interesting questions on its mind than “How could a sane woman do such a thing?”

I remember recoiling from the gossip-column circus over Letourneau, and I’ve never had any desire to see a movie about such abuse. So I’m writing about May December in search of some understanding: Why is this movie so surprisingly compelling? How is it that a film about such perverse behavior is sticking with me and inviting me back for another look as soon as possible?

The most obvious answer is that May December is the work of an idiosyncratic filmmaker in a state of high inspiration, making something that stands apart from its obvious influences (Bergman’s Persona and Hitchcock’s Vertigo, definitely — and possibly Assayas’s Clouds of Sils Maria) as a movie without any easy comparisons.

Todd Haynes has been one of America’s most intriguing auteurs since he left audiences breathless with his 1995 psychological thriller Safe, a film that gave Julianne Moore what some (including me) would argue is the greatest role of her career. He also worked magic with her in his Douglas Sirk homage Far From Heaven (2002). His filmography since then has been hit-and-miss for me. 2007’s I’m Not There has all of the audacity and ambition that any sufficient meditation on Bob Dylan’s shapeshifting career could need; but it felt overstuffed with ideas, as fascinating as they were. 2015’s Carol didn’t move me much, as the period style seemed so lavish and Cate Blanchett’s performance so calculated that Rooney Mara’s more vulnerable and human turn seemed stifled if not suffocated. Haynes was meticulous in his period recreation of 1927 and 1977 in of 2017’s Wonderstruck, but a plot heavy with contrivance and coincidence failed to suspend my disbelief. But more recently, he’s done strong work: I found his 2019 whistleblower thriller Dark Waters compelling, and his band-history documentary The Velvet Underground (2021) formally exciting. (For the record, I haven’t seen his limited-series TV remake Mildred Pierce.)

Haynes’s direction in May December is sly, strange, and surprising; he’s clearly excited by Burch’s inspired twist on a familiar story, how she takes the basic details of Letourneau’s case and complicates them with yet another layer of exploitation. Gracie (Julianne Moore), a former middle-school teacher who has served prison time, has been married to Joe (Charles Melton), her former student — that is, the victim of her abuse — for many years now. They are raising children together—their own, and children from Gracie’s previous marriage. As the film begins, they are welcoming a visitor to their home: Elizabeth (Natalie Portman), an actress who intends to play Gracie in a feature film, has won Gracie’s reluctant cooperation by promising to prioritize “the truth” over lurid sensationalism.

As Elizabeth studies Gracie and her relationship with Joe, shadowing both of them around their house and their daily routines, she is at first, for the audience, a cipher. We are studying the mystery of this marriage with her, trying to understand how it could possibly work. And we’re unnerved by Gracie and her control-freakish manipulation of her husband and her children. (Can a person be ferociously passive aggressive?)

But it doesn’t take long before the family’s increasing skepticism about the actress becomes our own. Elizabeth’s tactics and true intentions seem murkier the more time she spends with the family. At first, she seems to be trying out various method-acting tactics, copying Gracie’s gestures, practicing her delicate lisp. But she grows increasingly preoccupied with the allure of the seduction story, and with Joe’s boyish qualities — the ways in which he still seems so naive, so pliable, so easily confused. Does she want to play this role because her own judgment is, like Gracie’s, already corrupt? Or is it that the work of “becoming” a criminal character is poisoning her will? Is method acting dangerous?

Soon, we find ourselves conflicted about this intensifying clash of strong-willed women, tangled up in what Manohla Dargis calls “their worlds of lies.” Both women are weaponizing their performative talents to bend others to their will. (And, it’s worth noting, both of them are white, and the characters who they most successfully exploit are brown.) The more we watch Elizabeth working her way into Gracie’s world, the more she seems almost vampiric, enabled by the lingo of professional actors to justify her exploitative and self-indulgent behavior.

And as our suspicions about Elizabeth increase, so does our interest in and concern for Joe, who somehow still seems helplessly and hopelessly immature, ill-equipped to stand up to either woman’s scheming.

Joe is an extremely complicated character, and Charles Melton is entirely convincing in the role, both looking and acting like a teenager in a twenty-something’s body, as if he has somehow been catapulted a decade forward and missed out on essential stages of development — which is pretty much true. He genuinely seems to care about his much-older wife, although his function in the family seems more like that of a caretaker for Gracie than her equal partner.

By contrast, Gracie treats Joe, especially in social situations, more like an older son than a husband, lecturing him, and making condescending remarks about choices almost any adult should be trusted to make. (The fact that she met Joe and seduced him in a pet store is just one example of how the film’s seemingly incidental details have poetic resonance.) Joe is clearly insecure with his role and responsibilities in Gracie’s family, particularly when it comes to her adult children who are just about his age. In his private moments, he exchanges texts with an offscreen character in what looks to be the beginnings of an affair. When he’s not trying to keep Gracie happy or answering extremely personal questions from Elizabeth, he’s committed to a passion project; he’s raising endangered butterflies, strangely obsessed with observing their stages of maturation and the eventual metamorphosis that enables them to take flight. The symbolism here is, in one sense, heavy-handed: Clearly, Joe himself is caged and caught in a sort of arrested development, missing what he needs to grow up properly and spread his wings.

Perhaps it’s that focus on insects that makes me think of Blue Velvet, another film about an outsider following curiosity about a seriously effed-up situation only to find that what he learns is awakening his own perverse impulses. Remember how that film began by showing us a seemingly idyllic neighborhood, but then slowly drew us down past the picket fences and the roses into the soil, where all manner of creepy-crawlies were chewing away at the foundations?

With May December, Haynes returns to the fully immersive horror of Safe while also braiding paradoxically dramatic and hilarious tones — I believe what I’m seeing even as I’m laughing at the outrageousness of the whole scenario.

You’ve probably already heard about how Marcelo Zarvos’s score jump-scares us in the most unlikely moments with the overdramatic bombast of a soap-opera theme. This, too, reminds me of David Lynch films in which Angelo Badalamenti’s themes often complicate scenes with syrupy superficiality. Somehow, this deliberate, distracting artifice only increases the sense that something dreadful is taking place; no matter how often the film nods to the conventions of lurid daytime television, no matter how superficial the banter between the characters, no matter how sappy the music, we cannot shake the sense that wickedness — perhaps many kinds of wickedness — festers beneath the carefully manicured surfaces.

That’s ultimately where Haynes and Burch find their richest path of inquiry: Are we drawn to scandalous stories like Letourneau’s for the same reasons that we are so easily enamored of actors? Is it possible that we make idols of actors because they have found a way to “get away with” bad behavior under the guise of working and seeking the truth? Both Gracie and Elizbeth have “disappeared” into their roles, and thus have ways of dodging accountability for their exploitation of others. To get what they want, they justify selfish behavior by telling others to “grow up”; they attack anyone who questions their judgment; they act like tormented victims when they realize they’re in danger of exposure.

In what may be my favorite scene of 2023, Gracie watches one of her daughters try on dresses for a formal event, and she cannot resist making passive-aggressive comments that expose her disapproval — not her disapproval of the dresses, but of her daughter’s body. Meanwhile, Elizabeth pays strict attention to Gracie’s body language, mimicking until she’s like a mirror image of Gracie, modeling the surface while evincing no objection to the implications of Gracie’s behavior. I couldn’t help but think of how this scene, like the scene in Sofia Coppola’s Priscilla when Elvis critiques his underaged dream girl’s preference in dresses, makes obvious allusions to Hitchcock’s famous department store scene in Vertigo. What’s more, I think this scene is choreographed brilliantly in front of multiple mirrors to tease us with questions about who is being genuine, who is pretending; who is real, and who is just a reflection. It’s the best trick shot with mirrors I’ve seen since one involving Adam Driver and Golshifteh Farahani in Jim Jarmusch’s Paterson, and this one is far more complicated than that.

Altogether, May December is a masterclass in complex composition. Christopher Blauvelt, who also filmed Sofia Coppola’s The Bling Ring, Autumn de Wilde’s extravagant Emma., and most of Kelly Reichardt’s films including this year’s Showing Up, makes this the most visually compelling film I’ve seen all year, bringing long takes alive with such layered surprises that I wanted to turn around and see the film again as soon as the credits rolled. That filmography is a dazzling array of unique styles. Blauvelt has quickly become one of my favorite cinematographers working today.

All of these aspects — direction, screenwriting, acting, score, and cinematography cohere to elevate what could so easily be merely salacious and pulpy melodrama and make of it something richly cinematic, playful, and meaningful. I think it will speak most powerfully to viewers who have had to contend with passive-aggressive families or communities, or who have been exploited into serving others’ agendas. Those viewers will be quick to discern how Joe’s world is bound up in barbed-wire fences that keep him — and Gracie’s children too — trapped under Gracie’s control. Similarly, the film will speak to those in the arts who are familiar with the all-too-common vocabulary used by artists to avoid accountability and excuse dangerous behavior: their “search for something true,” their endeavors to “serve the character.”

Speaking for myself, I find poor, miserable Joe to stand at the center of the film’s deepest concerns. Gracie’s manipulation has cost him so much that he is struggling late in life to discover who he might really be, what he might really want. His preoccupation with saving endangered butterflies reminds me of how, as a teenager, I came to recognize how my own community’s codes of behavior were largely shaped by fear and by vanity. I found escape in literature, music, and movies, seeing within those mirrors reflections that revealed the falsity in so much of what I was taught. There was a beauty there that spoke to my longings, that showed me what was missing in my life. In art, I found a path to freedom and authenticity. And at the end of May December, I’m hopeful that Joe, for all of the ways he’s been abused and scarred, might yet find a way out.

It’s too soon for me to say it’s my favorite Haynes film, but I can say with conviction that May December is the first film I’ve seen in 2023 that felt like a completely new experience — one that constantly surprised me, reminded me of nothing I’d seen before, and gave me that delicious thrill of I have no idea what will happen next. And I can’t wait to see it again.