An early draft of this review was originally published on August 7, 2023,

at Give Me Some Light on Substack, months before it appeared here.

Subscribe, and you’ll read many of these reviews while the films are still breaking news!

In Part One of my Barbie coverage, I began by listening to others’ perspectives on the movie — specifically, to women I admire.

And now, as prologue to my review of Greta Gerwig’s Barbie, here’s some context:

I did not play with Barbies as a kid.

Surprise! In the culture that conditioned me, some toys were for boys and some toys were for girls. And so it was as unthinkable for me to reach for a Barbie doll, or even to stop and look at one in the store, as it would have been for me to walk into a pet store and consider buying iguana food. (I had a rabbit.)

But then, I was an unconventional kid: Most of the toys made for boys didn’t interest me either. I was more interested in books, in drawing, in making things than in posing plastic soldiers in scenes of combat. The green-and-yellow Crayola brand got my attention; the camo-style of G.I. Joe did not. And, by the grace of God, my parents were happy with this. My favorite toy was the typewriter. My compulsions were more about creating than playing with what others had made. I wanted to fill pages with words that I could read to myself and my parents. And I wanted a tape recorder for capturing my narration of those stories, complete with sound effects and background music (from my grandfather’s classical record collection). If I coveted the Sesame Street-branded hand puppets that I found at my friends’ house — and believe me, I did — it was because I wanted to bring them to life, give them voices, and put on a show for an audience, not so I could treat them as dress-up collectibles.

I seem to remember playing with action figures for the first time at around the age of five. The Fisher-Price Adventure People were presented as characters for storytelling. On the back of each box, a comic of several frames dramatized adventures that were possible with each set. With the Wild Safari set, a family took a car, a trailer, and a cage out into the wild (the outback, I assume?) to capture animals — a giraffe, a gorilla, a lion, a tiger—load them into cages, and haul them off to… what? Sell them to circuses? Keep them in a zoo? (These possibilities worried me. I thought it was more interesting to have them rescue the animals from captivity and return them to the wild. Or what if the animals escaped this cruelty and attacked their captors?)

My favorite Adventure People were the Aero Marine team: a helicopter pilot and a frogman in a blue wet suit. The pilot’s helicopter would lift and carry the frogman’s one-person submarine, which had big red pincers for retrieving items from the ocean floor, including a treasure chest loaded with gold — included in the set! The purpose of these toys was clear: Adventure! Imagine these characters working together to make discoveries and achieve exciting things! I never gave any thought to what these characters would shop for, or what accessories might make them more attractive to potential romantic partners. They came dressed appropriately for usefulness.

Barbies, by contrast, made no sense to me—even though they were everywhere. They lined the toy shelves in department stories. Commercials for Barbie were ubiquitous. (I have no memory of commercials for the Adventure People.) Girls at school played with Barbies and ate lunch from Barbie-branded lunch boxes. Broken pieces of Barbies would show up like crime-scene evidence on playgrounds and alongside roads in my neighborhood. “Weird Barbies” with badly scissored hair and smudged Crayola makeup lurked like monsters in the depths of toyboxes I rummaged through in the homes of my parents’ friends. I don’t remember my mother having any interest in or history of playing with Barbie dolls — and I’m grateful for that.

Everything changed, though, when Star Wars action figures arrived two years later. While these characters came with a pre-conceived context of good-guy rebels fighting bad-guy stormtroopers and dangerous alien monsters, they inspired my interest in accessorizing toys. And in the Star Wars universe, only one accessory really mattered: weapons. Guns for gunslingers. Lightsabers for Jedi. Starships with cannons. These toys came with an assumption that violence was their primary function, violence for good or for evil. (I don’t remember any commercials advertising what the actual story of Star Wars teaches us: that a mature and admirable Jedi Knight will cast his weapon aside rather than strike his enemy in anger.)

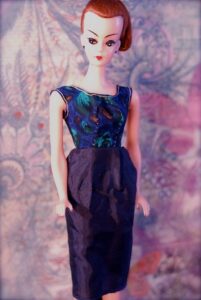

Barbie, as far as I could tell, may have dressed for various jobs and functions, but did she ever do anything? She seemed to exist for fashion accessories. She was, above all, an icon of capitalism, an enthusiastic consumer whose boyfriend was as superfluous as her hair pins. She existed for girls, yes, but seemed to be training girls in what an ideal woman should look like and dress like in order to be desired. We were not encouraged to ask about who was defining “ideal” and why.

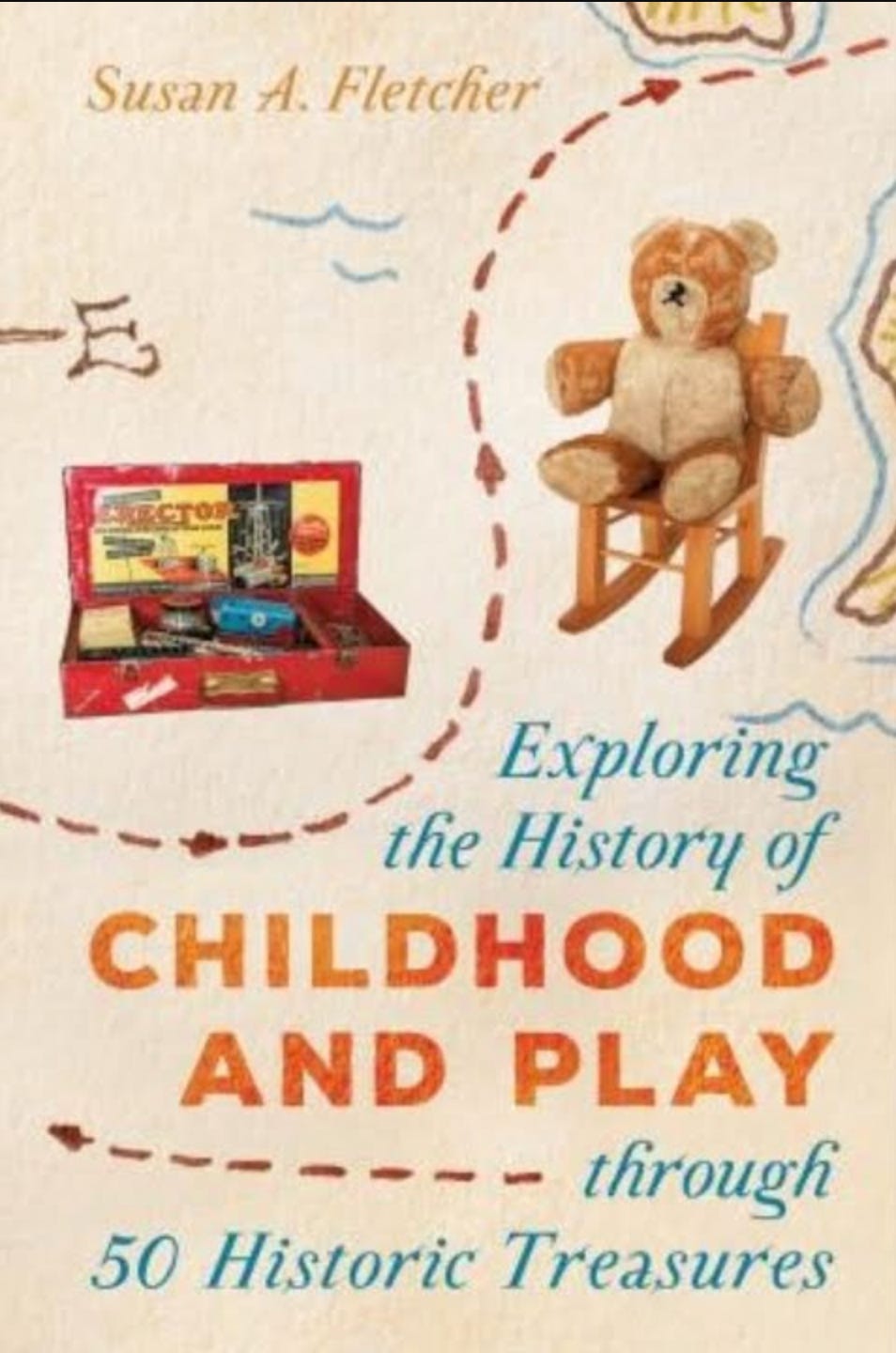

And that should come as no surprise. Barbie, according to Susan A. Fletcher’s book Exploring the History of Childhood and Play Through 50 Historic Treasures (Rowan and Littlefield, 2020), was inspired by Lilli, an amply-bosomed doll made as a sexual fantasy for grown men, sold at novelty stores in Germany.

(When I was challenged on this by another film critic, I looked around, and it seems this history has been well-documented. In fact, Business Insider updated this story very recently.)

Lilli was based on a cartoon by German artist Reinhard Berthein about a call girl who “accompanied men to dinner and costume parties, and occasionally went out wearing nothing more than her underwear” (Fletcher).

When Mattel-company co-owners Ruth and Elliot Handler discovered these dolls in Switzerland, she adopted and revised the idea, and named her “girl next door” version after her own daughter Barbie. (Her son, of course, was named Ken.) The Handlers discovered that they could make money by constantly introducing more and more accessories that little girls would believe Barbie needed: a wardrobe full of clothes, items necessary for different kinds of leisure, and, eventually, friends and potential romantic interests. And a house, of course. She was a way for girls to imagine themselves primarily as consumers.

And, at the same time, they conditioned many girls to focus on how they measured up (literally) to Barbie’s dimensions, and how they might make themselves up as objects of desire. Barbie, as a commodity, seemed likely to cause those playing with her to imagine themselves as commodities. In the early ’90s, when Teen Talk Barbie arrived, she kindled the fury of feminists by saying only a few things, one of which was “Math class is tough!” and another was “Let’s go shopping!” “Playing with Barbie,” Fletcher writes, “didn’t cultivate a nurturing instinct; instead, the doll taught girls about fashion and consumerism.”I encourage you to read the rest of Fletcher’s report, which tells the story of how some clever conspiracists fought against Barbie’s reinforcement of narrow and harmful gender stereotypes. It’s an eye-opening overview of how this plastic icon of womanhood has provoked controversy and important conversations about gender roles and the potential of toys for both creativity and destruction.

But I don’t recount this history in order to condemn or even criticize the girls who grew up with these toys. Just as many girls were seduced by the allure of the doll and what she represented, I was seduced by the not-so-subtle drive to convince boys that their value was connected to their capacity for combat. We were taught that every good male icon has his weapon of coercive violence.

Through childhood into my teens, I coveted Star Wars figures and, when I could afford them with my modest allowance, I started collecting. Looking back, I see that this was an expression of my enthusiasm for the storytelling of Star Wars and my love for the creativity of their design. But I also remember how, while I admired them and took pride in showing them off, I spent very little time actually playing with them. The fact that almost all of them were equipped with deadly weapons suggested that imaginative play should be about fighting, and that aspect of the merchandising phenomenon short-circuited my engagement with them. I loved having them lined up on my bookshelves because, like icons in a church, they reminded me of things that were important to me: heroism, sacrifice, humor. But now I wonder about how this prioritization of killing machines might have influenced my values and my politics as I grew up. And I wonder how they’ve influenced those men who invest themselves far more passionately in protecting their own right to bear arms than they do in matters of social justice for their vulnerable neighbors. They’ve bought into the lie that a “man” is someone who has a weapon and just might use it if you provoke him.

Of course, there’s a library’s worth of books to be written about how these toys reinforced false binaries too. If you were born with a body-model that didn’t align seamlessly with the rest of your complicated human chemistry set, there were no toys to represent you or to help you imagine your place in the world. You were bound to be branded as an alien, a defect. That’s a conversation for another time and place—but it’s an essential one, nevertheless.

One of the greatest ironies of toy-making that I’ve observed in adulthood is the merchandising of Peter Jackson’s Lord of the Rings movies. To promote a series about the grievous reality of wartime violence, and about heroes who are intent on humbly and sacrificially laboring to eliminate a weapon of mass destruction, the studio approved the production and sales of action figures who, like the Star Wars figures, all came equipped with weapons. What’s more, there were buttons on the backs of these figures that would trigger (literally) certain action moves, all of which were violent gestures: punches, strikes, swings. That, apparently, defined the usefulness, the function, the purpose of these characters.

I suspect that Tolkien, even though he participated in patriarchal systems, would have had trouble with this.

Me, I’ve only begun to repent of the oppressive and abusive hierarchies I’ve participated in. And I pray that my writing in both fiction and nonfiction serves to help dismantle such systems in the interest of justice and reparations.

I am grateful to say that my numerous nieces are growing up as women with strong minds, bold aspirations, and a sense of freedom from the straitjacketing gender norms that consumer culture has sought to instill in them. They don’t remind me of Barbie in any way. And that’s a good thing.

Even better, they’re bound to love Greta Gerwig’s Barbie movie for how it bravely dramatizes truths they already understand. They’re creative in nature, not merely consumers. They have higher priorities than the brand name on their accessories. Their storylines are already unfolding as the epic narratives of discovery and service. They look to me like real-world adventure people.

All of this gives me great hope for the future.

Just as I think it’s important to understand the origins of Barbie dolls and take the history of the product line as a cautionary tale of cultural poisons, I encourage you to see Greta Gerwig’s Barbie — even if, like me, you’ve never played with a Barbie in your life.

The more I think about the movie, the more I find myself reflecting on all of those toys in my childhood toybox, how they played roles in creating who I am today, and how they encouraged me to become a creator myself.

And in Part Three of my reflections on Barbie, I’ll go into detail on why I’m so delighted by the movie.